Jason Y. Ng's Blog, page 6

November 30, 2014

Mobile Occupy 流動佔領

There is no question that Hong Kong people love to shop; that’s why they call the city a shoppers’ paradise. This past week, citizens took our national sport to a whole new level. Gou wu (購物) – which means shopping in Mandarin – has become the battle cry for pro-democracy protestors to call on one another to visit Mongkok in large numbers. The goal is to overrun the area and wear down the police in response to their heavy-handed clearance of the Mongkok protest site a week ago. These shopaholics were hard at work in Kowloon even during Sunday’s violent clashes outside the Government Headquarters on the other side of the harbor. They have also found unlikely allies in the United States, where citizens have been organizing “die-ins” at shopping malls by playing dead on the floor in protest of the fatal police shooting of an unarmed teenager in Ferguson, Missouri.

Let's gou wu!

Let's gou wu!Mongkok, or MK for short, has always been a colorful and somewhat rough-and-tumble part of the city. It is a cross between Harajuku and the Bronx, where shopping centers tower over decades-old tenement buildings, where young buskers belt out Cantopop oldies next to a 55-year-old hula-hooper, and where triad bosses patrol the neighborhood to check up on seedy bars, nightclubs and massage parlors. Since tough streets beget tough crowds, you don’t expect MK protestors to take kindly to the government’s declaration of war last week.

And so when CY Leungcalled on citizens to resume their shopping routine after Nathan Road reopened, protestors self-organized into legions of retail warriors and descended on MK by the hundreds. These “shopping sprees” begin after dinner (to maximize turnout) and continue well past midnight. Shoppers walk in slow motion to clog sidewalks, pretend to drop and pick up loose change to stop traffic, and stand still for hours to watch movie trailers in front of a giant LCD screen. Never mind it’s 2:30 in the morning, shoppers holler “I want to buy a gold watch!” or “Sell me an iPhone 6!” in mocking Mandarin while marching down the busy thoroughfare. It gives new meaning to the expression “shop till you drop.”

Shoppers in Mongkok

Shoppers in MongkokBut even retail therapy can get a little tense. Once in a while, shoppers raise their right hands and give the famous three-finger salute from The Hunger Games in defiance. To taunt police, some recite passages from the Bible while others chant unintelligible verses from the Nilakantha Dharani, an ancient Buddhist script. And when their path is blocked by police barricades, they fall into a tactical formation like a Roman battalion and use umbrellas and homemade shields to break through. The gou wu operation was most intense last Friday, when shoppers led police on a wild goose chase through a dizzying web of backstreets between Mongkok and Tsim Sha Tsui in an all-night game of human Pac-Man.

The police finds little amusement in the shoppers’ antics. Whether it is the stress, the guilt, the plunging morale, or a combination of all three, their reactions range from mild annoyance to raging violence. Whereas unreasonable search and seizure is common and probably illegal, it is the indiscriminate assault on both protestors and bystanders that has drawn the most public outrage. Stories of citizens being randomly snatched by police and tackled to the ground are followed by allegations of torture and sexual molestation while in custody. Officers are also increasingly turning on the media, arresting a television cameraman because his step-ladder had “touched a policeman” and making up stories about a newspaper photographer trying to seize an officer’s gun.

Katniss Everdeen would be proud

Katniss Everdeen would be proudFrom rank-and-file officers to the riot police, to the PTU tactical unit and the anti-organized crime bureau, Hong Kong’s Finest are slowly coming undone. In a few isolated cases, those who are supposed to “serve with pride and care” appear to have jumped off the deep end, like the PC who ordered a South Asian pedestrian to “go back to India” and the superintendent caught on camera beating innocent passers-by with his baton. It would be unfair, however, to put all the blame on frontline officers. In the epic power struggle between the government and the governed, it is the people – policemen and protestors – who take the heat and get burned. To use a retail analogy, trying to solve a political problem with law enforcement is like dealing with a customer complaint by calling in store security. It’s a no-win proposition for everyone involved.

Police superintendent gone insane

Police superintendent gone insaneThe Umbrella Movement has proved to be enduring and ever-changing. In the past two months, it has evolved from a class boycott to a mass protest, to a street occupation and now to this: an all-out urban guerrilla warfare playing out in Mongkok every night. Based loosely on Bruce Lee’s combat philosophy to “be formless and shapeless like water,” the new approach is fluid, spontaneous and unpredictable. Above all, it can be easily replicated anywhere in the city – Central, Causeway Bay, Tsim Sha Tsui and Sham Shui Po – with the help of Facebook and Whatsapp.

This new phase of “mobile occupation” has not only given police the run around, but because the line between pedestrians and protestors is blurred, it has also made it harder for participants to be prosecuted under the city’s public order ordinance banning illegal assemblies. This last point is especially relevant given that the High Court has just issued a new injunction barring protestors from remaining on Harcourt and Connaught Roads, and that the days of the Admiralty protest site are numbered. That means protestors will need to think up inventive ways to keep the movement alive while circumventing the law and court orders. It is said that to rid a garden of dandelions, stepping on them will only send the seeds into the wind and worsen the blight. Our government has done just that.

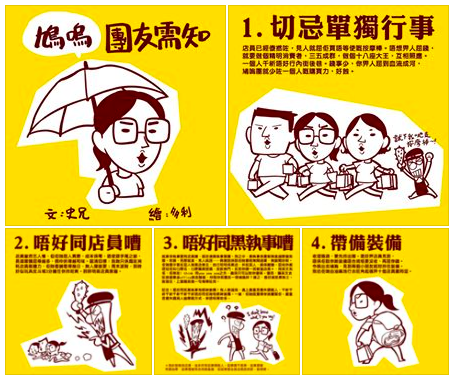

How-to guide for shoppers

How-to guide for shoppers

Published on November 30, 2014 08:57

November 24, 2014

Million Dollar Question: What’s Next for the Umbrella Movement? 有獎競猜: 雨傘運動何去何從?

A week ago, a small army of masked men gathered outside the Legco Building at Admiralty in the dead of night. They were upset, so they claimed, over a copyright amendment bill that would limit the freedom of expression on the Internet. The angry men smashed a pair of glass doors at the north entrance and urged student protestors nearby to occupy the legislature. But the students didn’t heed their call. Instead, Occupy Central marshals were dispatched to block the break-in. Minutes later, police moved in with pepper spray and batons, and the men quickly fled the scene.

Troublemakers or do they have a point?

Troublemakers or do they have a point?What appeared to be a clumsy “wreck-and-run” operation by a few agitators has touched off a political firestorm for the Umbrella Movement. Since last week’s incident, self-proclaimed “netizens” have been showing up at Admiralty in droves, challenging the student leadership and demanding that the marshal team be disbanded. Siding with the masked men, they argue that Alex Chow (周永康), Joshua Wong (黃之鋒) and their likes have gotten too comfortable sleeping in their tents, and that they and the self-appointed marshals are now standing in the way of the movement. Not since the Lung Wo Road confrontation with police a month ago have tensions at Admiralty been this high.

No one knows who the masked men and their supporters are – whether they are concerned citizens or members of nativist group Civic Passion (熱血公民) wanting their 15 minutes of fame. What we do know, however, is that there is now a protest within a protest, and a revolution within a revolution that is threatening to tear the movement apart. The emergence of a splinter group has laid bare a critical question facing the leadership: Should they raise the stakes instead of indefinitely prolonging the street occupation without a clear goal?

Challengers of the student leadership

Challengers of the student leadershipIndeed, the Umbrella Movement seems to have hit a plateau – or stuck in a rut, depending on your personal views. Protestors have been camping out on the city’s major arteries for two months. Even though stories of students doing homework at makeshift libraries, recycling water bottles into handicrafts, and generating electricity on exercise bikes are all very nice, critics fear the campaign is veering off track. At some point, denizens of Umbrellaville need to wake up to the reality that occupying city streets is a means rather than an end, and that the ultimate goal is universal suffrage and not some eco-friendly utopian lifestyle. As much as some of us would like the movement to go on forever, it has to end someday, somehow.

No one understands that better than the student leaders. A recent poll conducted by the University of Hong Kong found that 83% of citizens wanted the students to go home. What’s more, 68% would like the government to clear the sites if they don’t do so voluntarily. The rapid shift in public opinion now leaves the leadership with three options: (A) vacate, (B) negotiate, or (C) escalate.

Umbrellaville

UmbrellavilleI take no issues with Option A. In the past, I have argued that the success of Occupy Central as a post-modern political movement is measured not by tangible results but by the social awakening it brings about. On that account, the students have already achieved a great deal by arousing the youths’ interest in local politics. Packing it in at this point should not be viewed as a failure, but a chance to regroup and re-strategize. Considering how politically sensitized the city has become, Hong Kongers will be ready to re-deploy on a moment’s notice for the next chapter in our fight for democracy. These views notwithstanding, many protestors find the first option anticlimactic and even defeatist. They believe that going home now will kill both their momentum and the dwindling leverage they have over Beijing.

Turning to Option B, neither the government nor the student leadership has sat down since the 21 October talks, where both sides seemed more interested in addressing television viewers than each other. Whether we like it or not, the best way – and perhaps the only way – to break the political impasse is to talk constructively about the composition of the nomination committee as stipulated in Article 45 of the Basic Law. While that is a pragmatic solution, it also requires enormous political courage from the student leaders. Conceding to a committee-based nomination mechanic will be viewed by some protestors as a compromise on principles. And compromise, like it is in American politics, has become a dirty word in Hong Kong these days. Between paying a political price and maintaining the status quo, the leadership has so far chosen the latter.

Feels more like a high school debate

Feels more like a high school debateThat leaves them with Option C. As is the case for many social movements, there is nowhere to go but up. To raise the stakes, the leadership can choose from a number of classic tricks in the playbook: organize a mass hunger strike, picket government offices or take over the legislature, like the way students in Taiwan did during the Sunflower Revolution. But none of that will work unless the timing is ripe and the stars are aligned. Escalation requires careful planning, skillful execution and, most of all, a spark, like the arrest of Joshua Wong and the deployment of tear gas on 28 September that had started it all. Any attempt to up the ante without an emotional trigger to galvanize the city would end up like last week’s half-baked operation to storm the Legco Building – it will be doomed to fail.

Many of us have poured our hearts into the Umbrella Movement. Two months in and with the protests now showing cracks, it is time we used that other muscle we have and help the students – and they really are just students – figure out a way forward. There is no cash prize for answering the question of “what’s next,” but there is a high price to pay if we don’t.

The spark that started it all

The spark that started it all

Published on November 24, 2014 09:11

November 22, 2014

A Season of Discontent 不滿的季節

On 28 October, the one-month anniversary of the Umbrella Revolution, tens of thousands of citizens assembled at protest sites on both sides of the harbor. At precisely 5:58 pm, they opened their umbrellas in unison and turned the sea of people into a tsunami of colorful blossoms. The congregation then observed 87 seconds of silence, one for each shot of tear gas fired at protestors on that fateful day. It was “the day that changed everything,” the day by which we would forever divide our history: before and after 9/28.

Yellow umbrellas in full bloom

Yellow umbrellas in full bloomThe student-led movement that put Hong Kong on the world map has a modest beginning. A small group of university students had organized a class boycott to voice their anger over Beijing’s decision to renege on a promise – a political compromise made 10 years ago to allow Hong Kong citizens to democratically elect their chief executive in 2017. The promise wasn’t supposed to have any strings attached or funny business with semantics. Earlier this year, however, in an official announcement that many viewed as a change of heart by Beijing and a death knell for democracy in Hong Kong, the Communist Party made clear that only a nomination committee would decide who could run for the top office in the next election and that the committee would comprise of mostly pro-establishment yes-men as a way to block opposition candidates from the ballot. The announcement smacks of the famous line by Henry Ford when he introduced the Model T in 1909: “Our customers can have any color they want as long as it is black.”

What started as a small-scale student protest quickly spiraled into an all-out revolution, thanks to the use of tear gas and riot gear on 28 September against unarmed protestors who had nothing but raincoats, lab goggles and folding umbrellas to fend for themselves. The heavy-handed police response backfired and drew thousands more to the streets. Suddenly, years of frustration over income inequality, skyrocketing property prices and a Beijing-appointed government that favored vested interests bubbled to the surface and boiled over. By nightfall, highways and city streets were turned into Tahrir Square, and regular citizens became Rosa Parks and Mahatma Gandhi. Hong Kong, the Fragrant Harbor and the Pearl of the Orient, was embroiled in the biggest political event since Britain handed it back to China in 1997.

Tahrir Square in Hong Kong

Tahrir Square in Hong Kong28 September is as much a dividing line in history as it is in society. The Umbrella Revolution, and the daily inconveniences that have come with it, has polarized the city along political lines. The middle class blames protestors for rocking the economic boat and putting the ideology of a few above the livelihood of everyone. In turn, protestors accuse non-supporters of selling out the city’s future for a paycheck. Weeks of bickering and name-calling have driven a wedge between parents and children, husbands and wives, teachers and students, and the Yellow Ribbons (student supporters) and the Blue Ribbons (police sympathizers).

While citizens squabble over the movement’s merit, they can agree on at least one thing: the students’ tenacity and leadership have caught everyone by surprise. Just a month ago, these Millennials were spoiled brats who relied on their maids to make their beds and do their laundry. They couldn’t tell Martin Luther from Martin Luther King, David Cameron from James Cameron. Today, they are distributing medical supplies and building furniture at the protest sites. They are reading Karl Marx and picking up trash in one moment, and dodging pepper spray and pushing back angry thugs in the next. It was as if Peter Pan had grown up overnight to self-organize, self-sustain and self-govern. Their generosity of spirit has made them not only model protestors but also worthy heirs to our city’s future. It takes a heart of stone not to be won over by them.

Worthy heirs to our city's future

Worthy heirs to our city's futureIf the pint-sized warriors have come out on top on the public opinion battlefield, then the clear loser has to be C.Y. Leung, Hong Kong’s embattled chief executive. Leung’s unpopularity as a Beijing mouthpiece is matched only by the idiocy of his gaffes. On October 21, he told a New York Times reporter that universal suffrage was undesirable because it would allow social policies to skew toward the poor. The Freudian slip was followed by a snarky remark that athletes and religious groups contributed nothing to the economy. Reeling from foot-in-mouth disease and with his approval ratings approaching an impeachment level, Leung has, whether by choice or by Beijing’s order, placed himself under a self-imposed house arrest and delegated to his deputy Carrie Lam (林鄭月娥) many of his duties, including negotiating with student leaders for a way to break the impasse.

Another big loser in the political firestorm is the Hong Kong police force. Once revered in the region for their professionalism and restraint, they now see their hard-earned reputation slip through their batons. They have managed to alienate both the Yellow Ribbons by their inaction during the many thug attacks and the Blue Ribbons by their failure to reopen the streets. They squandered their last ounce of public trust when a pack of uniformed officers were caught on camera beating up a protestor in a back alley. As if that weren’t bad enough, a few days after the incriminating video went viral on social media, they were thrown under the bus by their own boss. In a television interview, C.Y. Leung denied any personal involvement in the decision to use tear gas on protestors and said it was the frontline officers who had made the call.

Hong Kong's finest?

Hong Kong's finest?Still, the biggest loser is probably Beijing itself. Its reaction to the movement has exposed the many cracks in the senior leadership. First, it has become clear that the Communist Party knows pitifully little about how Hong Kong people operate. 17 years after the Handover, Beijing continues to underestimate and misread Hong Kong citizens by assuming that they would be docile enough to swallow a broken promise for the sake of stability, or that protestors would be too squeamish to stay on the streets when a crackdown is threatened. Second, we now know that China is shockingly ill-prepared for a modern, bottom-up political movement. As if they had learned nothing from Egypt and Turkey, the Communists are still trying to fight 21st Century warfare with last century weapons: batons, tear gas and hired thugs. Finally and most remarkably, that the protests were allowed to go on for so long and that there have been many conflicting whispers from Beijing over C.Y. Leung’s political fate has revealed the leadership’s indecision and inconsistencies. Many point to the escalating factional infighting within the politburo since Xi Jinping (習近平) took the throne two years ago.

Excellent PR

Excellent PRWith winter fast approaching and both protestors and authorities running out of patience and energy, the million-dollar question lingers: what’s next for the Umbrella Revolution? Will student leaders sit down for more talks with government officials in the coming weeks? Will negotiation achieve anything given Beijing’s tough stance? How is this all going to end if neither side is willing to yield an inch? Therein lies the strength of a post-modern political movement: none of that matters. Success is no longer defined by results, but by social awakening and transformation of the collective consciousness. A new way of life has already coagulated in Hong Kong, and a whole generation of young citizens have woken from their existential slumber. Above all, a new Lion Rock Spirit has taken hold, one that is based on social justice and civic participation instead of hunkering down for trickle-down economic benefits. Draped in bright yellow, Hong Kong has finally come of age and is ready to be taken seriously.

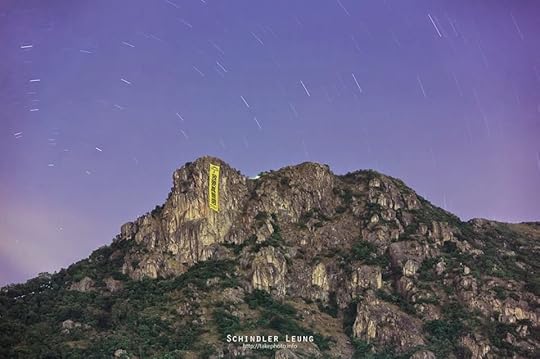

The new Lion Rock Spirit

The new Lion Rock SpiritThis article previously appeared in the November/December 2014 issue of MANIFESTO magazine under Jason Y. Ng's column “The Urban Confessional.”

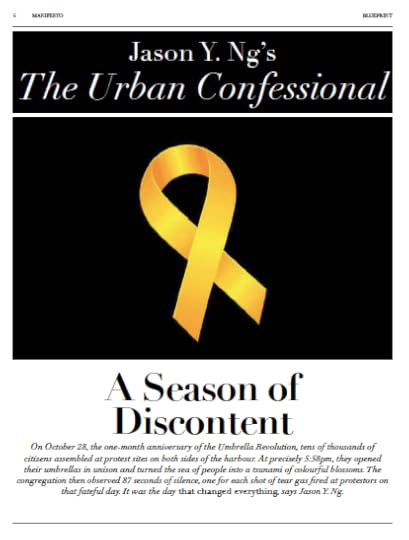

As printed in MANIFESTO

As printed in MANIFESTO

Published on November 22, 2014 06:32

November 19, 2014

Sexless in the City 無慾都市

The notion that Asian folks take a backseat in the sex department has been debunked time and again. The Japanese, for instance, make no secret of their bent for dominatrices and cosplayers. Korean men, on the other hand, can’t seem to find their way home without a stop at the neighborhood hostess bar. The Thai and the Filipino are equally comfortable with expressing their God-given sexuality. In Anything-goes Bangkok and No-tell Manila, the sex trade has gone mainstream and become a main draw for tourists.

What about Hong Kong, a place where skyscrapers rise like phallic symbols and animal genitals are eaten with gusto?

It turns out that Asia’s World City is also one of the world’s most sex-deprived. In a recent poll by the city’s Family Planning Association, 20% of the female respondents said they had no sexual desire, while 24% said they did not achieve orgasm during sex. Another local study found that one in five adult males had not gotten off in the last six months. As if that’s not miserable enough, an online survey conducted by condom-maker Durex ranks Hong Kong the third lowest in sexual satisfaction out of 26 territories. Despite our reputation as pleasure seekers – of luxury goods and world class cuisine – the joy of sex continues to elude us like Moby Dick.

So what went wrong?

Only in movies

Only in movies

The obvious answer is stress. By the time we get home after a 12-hour day in the office and 45 gruelling minutes on a crowded bus, few are in the mood for bedroom romance. Even a quickie doesn’t seem quick enough for time-pressed Hong Kongers. Another major turn-off is the lack of space and privacy. There isn’t much fun in making out on a tiny mattress covered with stuffed animals, while nosy parents may be eavesdropping next door. As a result, the only thing that gets fingered between the sheets is the iPhone screen, and all we get is a lousy peck on the cheek, before we, as Neil Diamond famously put it, “roll over and turn out the light.”

Stress and off-putting living conditions, however, only tell half the story. A closer look at Hong Kong society reveals two cultural forces that conspire to suck the fun out of our bedroom: conservatism and materialism.

Not conducive to romance

Not conducive to romance

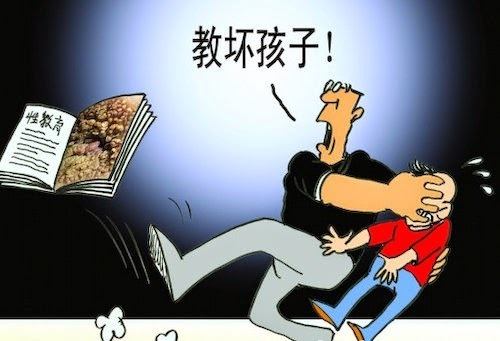

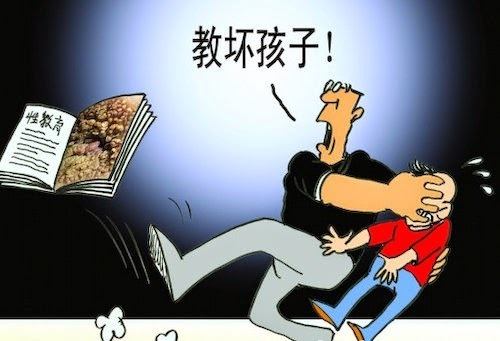

We may be a decade and a half into the new millennium, but the city’s attitude towards sex remains largely medieval. Chinese parents avoid the subject at home like a plague, and children growing up in single-gender schools – which account for most primary and secondary schools in Hong Kong – don’t get much exposure besides hearsay and myths. The knowledge gap is filled by social conservatism, a hotchpotch of traditional Confucius beliefs mixed with Christian values from the West, with a bunch of clichés and conventional wisdom tossed in. The resulting Frankenstein of moral ideology is inconsistent at best and traumatizing at worst. For instance, because sex is supposed to be dirty and dangerous, young adults are taught to practice strict abstinence until they graduate from university. But because sex is also special and sacred, grown-ups are advised to defer the pleasure to their wedding night. This arbitrary code of conduct has seeped into our subconscious and turned a basic biological behavior into a thing we don’t speak of – and keep deferring.

Materialism is the other cultural factor that explains our flaccid sex life. Rampant consumerism and in-your-face peer rivalry mean that our happiness is often measured by what we possess that others don’t. As economic creatures, we prefer making money to making love; we calculate, not fornicate. To the hard-driving man, sex is as much a distraction for the weak-minded as it is a social anesthesia for the poor. Whereas men in the West aspire to be fictional womanizers like James Bond and Tony Stark, being a playboy in practical Hong Kong confers very little bragging right. Instead, he is either branded a pervert or written off as a loser who wastes his time chasing girls rather than a job promotion.

Sex education means avoidance and deferral

Sex education means avoidance and deferral

The picture of the Hong Kong bedroom is grim. Our low libido is now a forgone conclusion and a cause for concern for both policy-makers and condom-makers. But just as I was finishing up my obituary for the city’s sex life, I spotted a glimmer of hope on Facebook. A few days ago, my friend Elaine shared a picture of her birthday gift from her husband CJ. It was a book titled Position of the Day: Sex Everyday in Every Way . I was impressed by how this thirty-something Chinese couple openly celebrate their sexuality on social media, and it prompted me to sit them down for a chat.

Like me, Elaine is miffed by the demonization of sex in Hong Kong. “I remember asking my mom about a kissing scene on television when I was five,” she recounted. “She told me the actors had to put scotch tapes on their lips for hygiene purposes. It was baloney of course, but she made me believe that sex was dirty, like politics.”

“I went to an all-girls secondary school and I wasn’t allowed to date anybody in my entire teens,” Elaine continued. “Other than my cousins, I had zero interaction with boys. The irony is that as soon as I graduated from university and found a job, my parents changed their tune: ‘When are you going to find a husband and have kids?’ It was surreal.”

By our standard, Li Ka Shing is the sexiest man alive

By our standard, Li Ka Shing is the sexiest man alive

For a guy, CJ is surprisingly comfortable discussing sex in the presence of his wife. He believes open communication is the key to a happy sex life. “Men have to check our egos at the bedroom door, especially if we aren’t satisfied with the amount of sex we get.” He gave an example. “After Elaine had our first child, we pretty much stopped doing it. I decided to tell her how I felt instead of keeping it to myself. It turned out she was worried that I wasn’t attracted to her after she gave birth to a baby. It was a big misunderstanding.”

CJ said many sexually frustrated men in Hong Kong simply turn to the Internet for quick relief. “It’s much more efficient that way,” he admitted. “Hong Kong people value efficiency and ambition. Most of my guy friends are so career-minded that sex gets pushed way down their priority list.”

The couple was quick to point out that the sex-averse culture is slowly changing. “Young people these days are more adventurous and resourceful than we were,” said Elaine. CJ chimed in with a tidbit of his own: “Love hotels like Victoria and Park Excellent are popular venues for a ‘test drive.’ A short trip to Macau or Taipei will do the trick too.” He gave Elaine a wink, recalling their first sexcapade in Bangkok. The two had only just started dating at the time and told family members they were spending the weekend with “a group of friends from work.”

“Looking back, it seems really silly that we had to lie about sleeping together,” said CJ. “How else would we know we were right for each other?” He made a good point, but it was Elaine who had the last word: “Sex is just sex and there’s nothing holy or evil about it. It’s just like food: we have to eat when we are hungry and we eat more if the food is good. It’s as simple as that.”

Finally, there is a couple with a healthy attitude toward sex. So forget about sex books and Viagra. To save Hong Kong’s flagging sex life, we need more people who think like them.

The most popular hourly hotel

The most popular hourly hotel

* * *

This article previously appeared in the October 2014 issue of MANIFESTO magazine under Jason Y. Ng's column “The Urban Confessional.”

As printed in MANIFESTO

As printed in MANIFESTO

What about Hong Kong, a place where skyscrapers rise like phallic symbols and animal genitals are eaten with gusto?

It turns out that Asia’s World City is also one of the world’s most sex-deprived. In a recent poll by the city’s Family Planning Association, 20% of the female respondents said they had no sexual desire, while 24% said they did not achieve orgasm during sex. Another local study found that one in five adult males had not gotten off in the last six months. As if that’s not miserable enough, an online survey conducted by condom-maker Durex ranks Hong Kong the third lowest in sexual satisfaction out of 26 territories. Despite our reputation as pleasure seekers – of luxury goods and world class cuisine – the joy of sex continues to elude us like Moby Dick.

So what went wrong?

Only in movies

Only in moviesThe obvious answer is stress. By the time we get home after a 12-hour day in the office and 45 gruelling minutes on a crowded bus, few are in the mood for bedroom romance. Even a quickie doesn’t seem quick enough for time-pressed Hong Kongers. Another major turn-off is the lack of space and privacy. There isn’t much fun in making out on a tiny mattress covered with stuffed animals, while nosy parents may be eavesdropping next door. As a result, the only thing that gets fingered between the sheets is the iPhone screen, and all we get is a lousy peck on the cheek, before we, as Neil Diamond famously put it, “roll over and turn out the light.”

Stress and off-putting living conditions, however, only tell half the story. A closer look at Hong Kong society reveals two cultural forces that conspire to suck the fun out of our bedroom: conservatism and materialism.

Not conducive to romance

Not conducive to romanceWe may be a decade and a half into the new millennium, but the city’s attitude towards sex remains largely medieval. Chinese parents avoid the subject at home like a plague, and children growing up in single-gender schools – which account for most primary and secondary schools in Hong Kong – don’t get much exposure besides hearsay and myths. The knowledge gap is filled by social conservatism, a hotchpotch of traditional Confucius beliefs mixed with Christian values from the West, with a bunch of clichés and conventional wisdom tossed in. The resulting Frankenstein of moral ideology is inconsistent at best and traumatizing at worst. For instance, because sex is supposed to be dirty and dangerous, young adults are taught to practice strict abstinence until they graduate from university. But because sex is also special and sacred, grown-ups are advised to defer the pleasure to their wedding night. This arbitrary code of conduct has seeped into our subconscious and turned a basic biological behavior into a thing we don’t speak of – and keep deferring.

Materialism is the other cultural factor that explains our flaccid sex life. Rampant consumerism and in-your-face peer rivalry mean that our happiness is often measured by what we possess that others don’t. As economic creatures, we prefer making money to making love; we calculate, not fornicate. To the hard-driving man, sex is as much a distraction for the weak-minded as it is a social anesthesia for the poor. Whereas men in the West aspire to be fictional womanizers like James Bond and Tony Stark, being a playboy in practical Hong Kong confers very little bragging right. Instead, he is either branded a pervert or written off as a loser who wastes his time chasing girls rather than a job promotion.

Sex education means avoidance and deferral

Sex education means avoidance and deferralThe picture of the Hong Kong bedroom is grim. Our low libido is now a forgone conclusion and a cause for concern for both policy-makers and condom-makers. But just as I was finishing up my obituary for the city’s sex life, I spotted a glimmer of hope on Facebook. A few days ago, my friend Elaine shared a picture of her birthday gift from her husband CJ. It was a book titled Position of the Day: Sex Everyday in Every Way . I was impressed by how this thirty-something Chinese couple openly celebrate their sexuality on social media, and it prompted me to sit them down for a chat.

Like me, Elaine is miffed by the demonization of sex in Hong Kong. “I remember asking my mom about a kissing scene on television when I was five,” she recounted. “She told me the actors had to put scotch tapes on their lips for hygiene purposes. It was baloney of course, but she made me believe that sex was dirty, like politics.”

“I went to an all-girls secondary school and I wasn’t allowed to date anybody in my entire teens,” Elaine continued. “Other than my cousins, I had zero interaction with boys. The irony is that as soon as I graduated from university and found a job, my parents changed their tune: ‘When are you going to find a husband and have kids?’ It was surreal.”

By our standard, Li Ka Shing is the sexiest man alive

By our standard, Li Ka Shing is the sexiest man aliveFor a guy, CJ is surprisingly comfortable discussing sex in the presence of his wife. He believes open communication is the key to a happy sex life. “Men have to check our egos at the bedroom door, especially if we aren’t satisfied with the amount of sex we get.” He gave an example. “After Elaine had our first child, we pretty much stopped doing it. I decided to tell her how I felt instead of keeping it to myself. It turned out she was worried that I wasn’t attracted to her after she gave birth to a baby. It was a big misunderstanding.”

CJ said many sexually frustrated men in Hong Kong simply turn to the Internet for quick relief. “It’s much more efficient that way,” he admitted. “Hong Kong people value efficiency and ambition. Most of my guy friends are so career-minded that sex gets pushed way down their priority list.”

The couple was quick to point out that the sex-averse culture is slowly changing. “Young people these days are more adventurous and resourceful than we were,” said Elaine. CJ chimed in with a tidbit of his own: “Love hotels like Victoria and Park Excellent are popular venues for a ‘test drive.’ A short trip to Macau or Taipei will do the trick too.” He gave Elaine a wink, recalling their first sexcapade in Bangkok. The two had only just started dating at the time and told family members they were spending the weekend with “a group of friends from work.”

“Looking back, it seems really silly that we had to lie about sleeping together,” said CJ. “How else would we know we were right for each other?” He made a good point, but it was Elaine who had the last word: “Sex is just sex and there’s nothing holy or evil about it. It’s just like food: we have to eat when we are hungry and we eat more if the food is good. It’s as simple as that.”

Finally, there is a couple with a healthy attitude toward sex. So forget about sex books and Viagra. To save Hong Kong’s flagging sex life, we need more people who think like them.

The most popular hourly hotel

The most popular hourly hotel* * *

This article previously appeared in the October 2014 issue of MANIFESTO magazine under Jason Y. Ng's column “The Urban Confessional.”

As printed in MANIFESTO

As printed in MANIFESTO

Published on November 19, 2014 06:06

October 28, 2014

Searching for Umbrella Man 尋找雨傘人

Edward arrived at the vehicle-free Connaught Road expressway and surveyed the Admiralty protest site, which, until then, he had only seen on CNN. It was 18 October, Day 20 of the largest political event in Hong Kong’s post-Handover history. The 40-year-old law firm partner had just returned from a business trip in London that had kept him out of town for the last two weeks. He climbed over the median barrier and studied the wall of pro-democracy signage written in a few dozen languages. From his elevated vantage point, he could see metal barricades blocking major arteries connecting the financial district to the rest of the city. Protestors had reinforced the roadblocks with garbage cans, wooden crates and water-filled barriers, tied together with household plastic fasteners. He took out his phone to snap a few shots, and heaved a sigh.

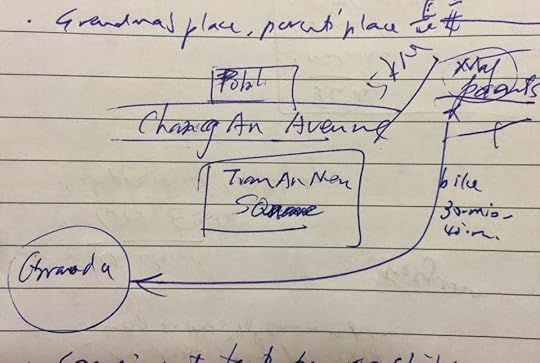

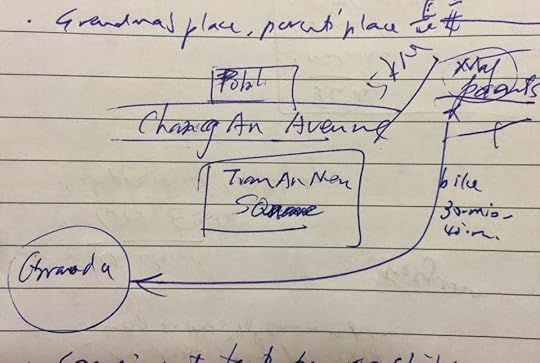

Xiaobing would turn 15 in a few days and Nai-nai, his grandmother, had baked him his favorite sweet buns. The evening before, Xiaobing had biked the five-kilometer distance from his home near Chang’an Avenue (長安路) to Nai-nai’s place southwest of Tiananmen Square to pick up the buns. That his school had recently suspended classes had left the teenager with a lot of free time on his hands. The entire Beijing had been in lockdown since May, after students from Peking University began camping out on Tiananmen Square. Many streets along Xiaobing’s bike route had been blocked by makeshift barriers built by local residents using whatever materials they could find on the streets. According to Xiaobing’s father, a military officer, the roadblocks were there to stop soldiers from entering the city and harming the students.

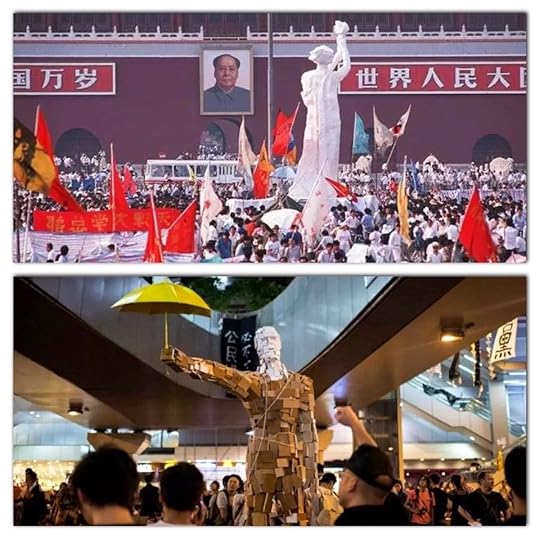

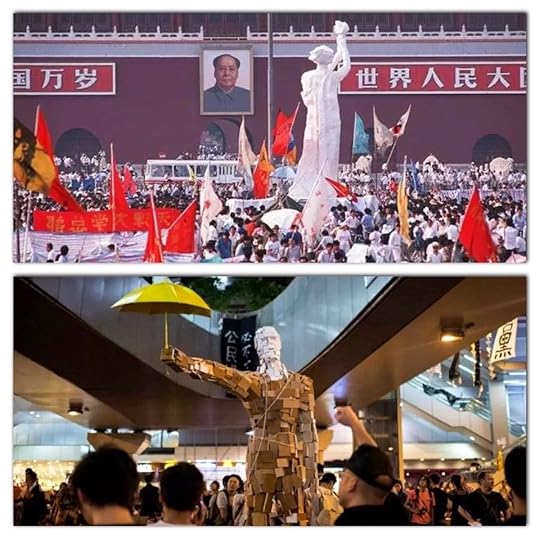

Student protests, then and now

Student protests, then and now

Inside the tent city at Admiralty, Edward slowed his pace to take in the new way of life that had coagulated in the past three weeks. The sprawling maze of camping tents were flanked by shower facilities and first aid stations. At an area labeled “Study Room,” student protestors hunkered down to do homework, while volunteers patrolled up and down the aisle to offer snacks. Edward walked up to one of the supplies tents to check out what they had: bottled water, crackers, umbrellas, blankets and foam mats. “Would you like a drink of water?” the station manager offered, handing him a bottle. “No, thank you,” Edward repied, “but may I ask where you got all this stuff?” “Everything was donated,” the manager said matter-of-factly. “Excuse me for a second,” she apologized, before turning to a delivery man who had just arrived with a load of supplies. A fruit vendor had sent four boxes of bananas and two crates of Chinese pears.

Peking University students had worked out a division of labor on and off Tiananmen Square: liberal arts students would give speeches and hand out flyers on major intersections, while engineering and science students would work behind the scenes to build tents and transport supplies. Some came up with the idea of releasing balloons to ward off reconnaissance helicopters dispatched by the military. Many students had gone on a hunger strike, some even stopped drinking water altogether. But that had not stopped concerned citizens from taking food to the square by tricycle. Many parents prepared homemade red bean soup and other desserts; others provided hand towels and clean clothes. Xiaobing too wanted to give away Nai-nai’s sweet buns, even though he did not really understand why students had occupied the square. They spoke of democracy and reform, and used big words like pluralism and constitutionalism. All Xiaobing knew was that the protestors meant well and that the entire city had rallied behind them. He had never seen Beijing so united for a cause.

Police-protestor standoff, then and now

Police-protestor standoff, then and now

Edward approached one of the students at the Study Room and asked, in accented Cantonese, how long she had been studying there. “Since the facility was built last week,” she answered. He then asked her which university she attended. “Chinese Univer… Excuse me, are you a Blue Ribbon?” She meant whether he was a police sympathizer. Edward figured it must have been his Mainland accent that had roused her suspicion. “Haha, no,” he chuckled and said, “I’m just a concerned citizen.” He had read about the Blue Ribbons in the paper: anti-protestors who descended on protest sites to taunt students and forcibly remove barricades. There were verbal, sometimes physical and sexual, assaults. No one knew who they really were: angry citizens who had been inconvenienced by the protests, or rent-a-mobs hired to instill fear. The ones who wore face masks and black T-shirts were believed to be triad members. Even though the Blue Ribbons were most active in Mongkok and had by-and-large stayed clear of Admiralty, Edward understood why the young girl would be guarded when a stranger asked too many questions.

Despite everything that was going on in Beijing, Xiaobing continued to hang out on the streets. The knowledge that his father was a military officer had given him a sense of security. In the past several days, however, Xiaobing had seen mean-looking men smashing car windows and vandalising public property. The delinquents worked systematically, as if following orders. They would only wreak things and leave civilians alone. Their presence had fueled rumors that the government had released prisoners to the streets to make trouble, which would then give the army a convenient excuse to enter the city to reclaim Tiananmen Square. That’s what Xiaobing had heard from the neighbors when they discussed the situation with his parents. Until then, it had not crossed his mind that the government he was taught all his life to praise was capable of doing such evil things.

Symbol of democracy, then and now

Symbol of democracy, then and now

Edward found what he had gone to Admiralty to see: Umbrella Man. Created by fine arts students out of scrap wood, the 12-foot-tall statue symbolized the protesters’ use of umbrellas to fend off tear gas 20 days ago. Since then, students continued to invent new defences, wrapping foam flooring on their arms and shins to protest against police batons and putting on lab goggles to keep off pepper spray. Other than isolated episodes of excessive force, however, law enforcement had exercised relative restraint toward the students. Predictions that the police might use rubber bullets or mobilize tour buses to round up protestors had so far been false alarms. Edward took a picture of the towering statue with his phone, lowered his head and said a prayer.

In the small hours of 4 June, two days before his 15th birthday, Xiaobing – and everyone else in the neighborhood – was woken up by the trembling of the ground. His mother thought it was an earthquake but his father knew better: the tremors were vertical and not sideways. At around 5:00am, Xiaobing found himself standing on a street corner next to some of his neighbors, watching a caravan of tanks hurtle down Chang’an Avenue. By his count, there were at least a dozen of them. Xiaobing could not take his eyes off the caterpillar tracks – there were sparks where the metal plates hit the ground. The weight of the tanks cracked the tarmaced road, whipping up a small sandstorm in their path. They were travelling at full speed toward Tiananmen Square, where many of the students were still asleep in their tents. But not for long. From afar, Xiaobing could hear sporadic bursts of gunshots at the square, punctuated by the low boom of tear gas blasts. He ran back home to tell his parents what he had seen and heard.

The rest of the morning was a blur. Xiaobing vaguely remembered the dull sound of raindrops pattering at the living room windows. In the afternoon, he returned to the streets with his parents. On Chang’an Avenue, they saw a burned armoured vehicle, which, as they would later find out, was torched by an enraged man who had lost his only son during the military intervention. Outside Tiananmen Square, Xiaobing saw an orderly formation of tanks on one side of the now empty space. There was not a student or camping tent in sight; even the 33-foot-tall Goddess of Democracy statue had vanished into thin air. Nor was there any trace of blood. It was said that the heavy rain that morning was a gift from the gods to the government, to erase any evidence of their crimes. Xiaobing looked up to the sky and saw a cluster of helicopters. It was how the government managed to clean everything up so quickly, his father explained. The only hint of a massacre was the pockmarked walls and structures in the area. Many of the bullet holes were at eye level, that meant soldiers were shooting to kill. His father said the killers were no ordinary soldiers, because ordinary soldiers would not shoot civilians. He was convinced that they were active-duty troops sent back from the Chinese-Vietnamese border* to carry out a specific mission: clear Tiananmen Square by daybreak.

Hand-drawn map by Edward

Hand-drawn map by Edward

After finishing secondary school in Beijing, Xiaobing moved to the UK to study law and took the Christian name Edward. He practiced at a London law firm for 12 years before moving to Hong Kong in 2010. These days, he flies to Beijing every summer to see his old parents and visit what he calls the ghosts of Tiananmen Square. Standing in front of the Umbrella Man statue at Admiralty, Edward felt a lump in this throat. He was overcome by the striking similarities between the two student-led movements: their organization, their struggles and, on some level, their naïveté. In his prayer, he asked the gods to spare the protestors from the fate met by their brothers and sisters 25 years ago. He prayed that Beijing had learned its lessons, and that the story would have a different ending this time around. He also prayed that the students in Hong Kong would have the patience for a drawn-out war, for whatever it is that they are asking for will not happen overnight. Edward then said goodbye to Umbrella Man, an old friend he had just met.

______________________This article is based on the author's personal interview with Edward, who gave his firsthand account of what he witnessed on 4 June 1989. His last name is omitted to avoid personal repercussion for him in Mainland China.

*The Sino-Vietnamese skirmish of 1984 ended in early 1989.

Xiaobing would turn 15 in a few days and Nai-nai, his grandmother, had baked him his favorite sweet buns. The evening before, Xiaobing had biked the five-kilometer distance from his home near Chang’an Avenue (長安路) to Nai-nai’s place southwest of Tiananmen Square to pick up the buns. That his school had recently suspended classes had left the teenager with a lot of free time on his hands. The entire Beijing had been in lockdown since May, after students from Peking University began camping out on Tiananmen Square. Many streets along Xiaobing’s bike route had been blocked by makeshift barriers built by local residents using whatever materials they could find on the streets. According to Xiaobing’s father, a military officer, the roadblocks were there to stop soldiers from entering the city and harming the students.

Student protests, then and now

Student protests, then and nowInside the tent city at Admiralty, Edward slowed his pace to take in the new way of life that had coagulated in the past three weeks. The sprawling maze of camping tents were flanked by shower facilities and first aid stations. At an area labeled “Study Room,” student protestors hunkered down to do homework, while volunteers patrolled up and down the aisle to offer snacks. Edward walked up to one of the supplies tents to check out what they had: bottled water, crackers, umbrellas, blankets and foam mats. “Would you like a drink of water?” the station manager offered, handing him a bottle. “No, thank you,” Edward repied, “but may I ask where you got all this stuff?” “Everything was donated,” the manager said matter-of-factly. “Excuse me for a second,” she apologized, before turning to a delivery man who had just arrived with a load of supplies. A fruit vendor had sent four boxes of bananas and two crates of Chinese pears.

Peking University students had worked out a division of labor on and off Tiananmen Square: liberal arts students would give speeches and hand out flyers on major intersections, while engineering and science students would work behind the scenes to build tents and transport supplies. Some came up with the idea of releasing balloons to ward off reconnaissance helicopters dispatched by the military. Many students had gone on a hunger strike, some even stopped drinking water altogether. But that had not stopped concerned citizens from taking food to the square by tricycle. Many parents prepared homemade red bean soup and other desserts; others provided hand towels and clean clothes. Xiaobing too wanted to give away Nai-nai’s sweet buns, even though he did not really understand why students had occupied the square. They spoke of democracy and reform, and used big words like pluralism and constitutionalism. All Xiaobing knew was that the protestors meant well and that the entire city had rallied behind them. He had never seen Beijing so united for a cause.

Police-protestor standoff, then and now

Police-protestor standoff, then and nowEdward approached one of the students at the Study Room and asked, in accented Cantonese, how long she had been studying there. “Since the facility was built last week,” she answered. He then asked her which university she attended. “Chinese Univer… Excuse me, are you a Blue Ribbon?” She meant whether he was a police sympathizer. Edward figured it must have been his Mainland accent that had roused her suspicion. “Haha, no,” he chuckled and said, “I’m just a concerned citizen.” He had read about the Blue Ribbons in the paper: anti-protestors who descended on protest sites to taunt students and forcibly remove barricades. There were verbal, sometimes physical and sexual, assaults. No one knew who they really were: angry citizens who had been inconvenienced by the protests, or rent-a-mobs hired to instill fear. The ones who wore face masks and black T-shirts were believed to be triad members. Even though the Blue Ribbons were most active in Mongkok and had by-and-large stayed clear of Admiralty, Edward understood why the young girl would be guarded when a stranger asked too many questions.

Despite everything that was going on in Beijing, Xiaobing continued to hang out on the streets. The knowledge that his father was a military officer had given him a sense of security. In the past several days, however, Xiaobing had seen mean-looking men smashing car windows and vandalising public property. The delinquents worked systematically, as if following orders. They would only wreak things and leave civilians alone. Their presence had fueled rumors that the government had released prisoners to the streets to make trouble, which would then give the army a convenient excuse to enter the city to reclaim Tiananmen Square. That’s what Xiaobing had heard from the neighbors when they discussed the situation with his parents. Until then, it had not crossed his mind that the government he was taught all his life to praise was capable of doing such evil things.

Symbol of democracy, then and now

Symbol of democracy, then and nowEdward found what he had gone to Admiralty to see: Umbrella Man. Created by fine arts students out of scrap wood, the 12-foot-tall statue symbolized the protesters’ use of umbrellas to fend off tear gas 20 days ago. Since then, students continued to invent new defences, wrapping foam flooring on their arms and shins to protest against police batons and putting on lab goggles to keep off pepper spray. Other than isolated episodes of excessive force, however, law enforcement had exercised relative restraint toward the students. Predictions that the police might use rubber bullets or mobilize tour buses to round up protestors had so far been false alarms. Edward took a picture of the towering statue with his phone, lowered his head and said a prayer.

In the small hours of 4 June, two days before his 15th birthday, Xiaobing – and everyone else in the neighborhood – was woken up by the trembling of the ground. His mother thought it was an earthquake but his father knew better: the tremors were vertical and not sideways. At around 5:00am, Xiaobing found himself standing on a street corner next to some of his neighbors, watching a caravan of tanks hurtle down Chang’an Avenue. By his count, there were at least a dozen of them. Xiaobing could not take his eyes off the caterpillar tracks – there were sparks where the metal plates hit the ground. The weight of the tanks cracked the tarmaced road, whipping up a small sandstorm in their path. They were travelling at full speed toward Tiananmen Square, where many of the students were still asleep in their tents. But not for long. From afar, Xiaobing could hear sporadic bursts of gunshots at the square, punctuated by the low boom of tear gas blasts. He ran back home to tell his parents what he had seen and heard.

The rest of the morning was a blur. Xiaobing vaguely remembered the dull sound of raindrops pattering at the living room windows. In the afternoon, he returned to the streets with his parents. On Chang’an Avenue, they saw a burned armoured vehicle, which, as they would later find out, was torched by an enraged man who had lost his only son during the military intervention. Outside Tiananmen Square, Xiaobing saw an orderly formation of tanks on one side of the now empty space. There was not a student or camping tent in sight; even the 33-foot-tall Goddess of Democracy statue had vanished into thin air. Nor was there any trace of blood. It was said that the heavy rain that morning was a gift from the gods to the government, to erase any evidence of their crimes. Xiaobing looked up to the sky and saw a cluster of helicopters. It was how the government managed to clean everything up so quickly, his father explained. The only hint of a massacre was the pockmarked walls and structures in the area. Many of the bullet holes were at eye level, that meant soldiers were shooting to kill. His father said the killers were no ordinary soldiers, because ordinary soldiers would not shoot civilians. He was convinced that they were active-duty troops sent back from the Chinese-Vietnamese border* to carry out a specific mission: clear Tiananmen Square by daybreak.

Hand-drawn map by Edward

Hand-drawn map by EdwardAfter finishing secondary school in Beijing, Xiaobing moved to the UK to study law and took the Christian name Edward. He practiced at a London law firm for 12 years before moving to Hong Kong in 2010. These days, he flies to Beijing every summer to see his old parents and visit what he calls the ghosts of Tiananmen Square. Standing in front of the Umbrella Man statue at Admiralty, Edward felt a lump in this throat. He was overcome by the striking similarities between the two student-led movements: their organization, their struggles and, on some level, their naïveté. In his prayer, he asked the gods to spare the protestors from the fate met by their brothers and sisters 25 years ago. He prayed that Beijing had learned its lessons, and that the story would have a different ending this time around. He also prayed that the students in Hong Kong would have the patience for a drawn-out war, for whatever it is that they are asking for will not happen overnight. Edward then said goodbye to Umbrella Man, an old friend he had just met.

______________________This article is based on the author's personal interview with Edward, who gave his firsthand account of what he witnessed on 4 June 1989. His last name is omitted to avoid personal repercussion for him in Mainland China.

*The Sino-Vietnamese skirmish of 1984 ended in early 1989.

Published on October 28, 2014 18:17

October 4, 2014

Darkest Before Dawn 黎明前的黑暗

Tear gas and pepper spray are so last week.

On Friday, Day 6 of the Umbrella Revolution, hired thugs fanned out at protest sites across the city, starting with Mongkok and quickly spreading to Tsim Sha Tsui and Causeway Bay. By nightfall, angry mobs disguised as “pro-Hong Kong citizens” had moved into Admiralty, the heart of the students-led pro-democracy movement.

Thug attack

Thug attackI had arrived in Admiralty earlier the evening to offer protestors free help with their homework on the street. I was explaining the stories of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. to two university freshmen, when my phone started to buzz with text messages. “The Triads are heading your way. Stay Safe!” a reporter friend warned. “Leave Admiralty NOW, and remove any yellow ribbons on you,” said another. The yellow ribbon has been an insignia for the movement, as is the yellow umbrella that is now known around the world. Pro-Beijing groups have responded with a symbol of their own: a blue ribbon to call on law enforcement to end the political standoff. Many of the thugs in Mongkok were seen wearing the blue ribbon.

I didn’t pay much attention to my friends’ warnings. They weren’t anything new – rumors about Beijing mobilizing Triad members to harass protestors had been circulating on social media for days. With so many false alarms going off this week, we had learned to take things with a heap of salt. That said, fighting crowds with crowds is nothing new. Rent-a-mobs are routinely deployed in unrests in Thailand and the Philippines. They are a weapon of choice not only because links to the renter are hard to prove, but also because they give authorities a convenient excuse to use force. A clash between yellow and blue ribbons would certainly be the justification that Hong Kong police had been waiting for to end the week-long impasse.

One of clashes in Mongkok

One of clashes in MongkokA few minutes later, my sidewalk classroom was interrupted yet again, this time by speeches broadcasted from a makeshift podium fifty meters away. The speaker was Joshua Wong (黃之鋒), founder of the activist group Scholarism (學民思潮) and one of the leaders of the Umbrella Revolution. He was confirming reports that throngs of angry blue ribbons had overrun Mongkok and Causeway Bay. Then came a series of emotional accounts from students who had been kicked and punched by mobsters earlier that evening. One girl, still sobbing, recounted her experience of being groped in the chest and up the legs. Horrified, I took out my phone and searched for corroborating news reports on the Internet. On the subject of sexual assault, one man was heard taunting a teenage girl: “You should expect molestation in a street protest!”

I told my “students” to go home and continued scrolling through the news feed on my phone. The situation had deteriorated rapidly in the last several hours. Amateur videos of physical and sexual assault abounded, many of them were too gruesome to watch. The attacks, a form of domestic terrorism, were systematic and indiscriminate: students, journalists and even passers-by. Much of the public outrage was also directed at the police’s flagrant inaction. Some uniformed officers were seen standing idly by with their arms folded, while others took advantage of the mayhem to remove barricades set up by students. Worse, there were video clips showing police officers arresting assailants on the spot, only to release them quietly on the other end of the street.

I continued to sit on the sidewalk, overcome with disgust, frozen in disbelief. I had many unanswered questions. Were the blue ribbons gang members or disgruntled citizens? Were they hired by Beijing? Were they working in cahoots with police? Who were our real enemies? The only thing I knew was that whoever was behind the coordinated attacks had run out of options and was desperate enough to make a deal with the devil. Resorting to Hong Kong’s Underworld to handle tricky situations has long been an open secret and a time-honored tradition. In 1984, paramount leader Deng Xiaoping openly endorsed the Triads by declaring that “there are many good guys among them.” These days, local mafias like 14K and Wo Sing Wo are called upon by loan sharks to collect unpaid debt, and from property developers to intimidate stubborn residents who hold up lucrative real estate projects.

Student protestors formed a human chain to keep the peace

Student protestors formed a human chain to keep the peaceI decided to heed my friends’ advice to leave the protest site before the mob arrived. I spent the rest of the night at home watching clashes in Admiralty play out on live television. Images of peaceful protestors being beaten and not fighting back broke my heart and sickened my stomach. The next morning, I woke up to more news reports of fracas happening all over the city, as some of the protestors attempted to reclaim Mongkok and Causeway Bay. At a news conference, Security Secretary Lai Tung-kwok (黎棟國) vehemently denied claims of collusion between police and the Triads. On a radio show, cabinet member Lam Woon-kwong (林焕光) dismissed the allegations as a “fairy tale.” I drifted in and out of sleep while footage of street violence interweaved with public statements by government officials. By 1:30pm, I was still in bed, staring unseeing at the television set. I was disgusted by the ochlocracy in our streets and the little that had been done to stop it. I was angry with some of my Facebook friends who applauded the blue ribbons for teaching student protestors a lesson. Above all, I was depressed by the hopelessness of the situation, for the mob attacks would only get worse in the days to come.

I found myself right where our enemies wanted us to be: a state of dejection and defeat. “You are smarter than that,” I told myself. I then willed my body out of bed, took a cold shower and ate a hearty lunch, the first proper meal in the last 48 hours. As I emptied my bag, I found a piece of hard candy given to me by a student volunteer the night before. My eyes started to well up, for the gift reminded me of how much they had done for the city and the long way they had yet to go. It also gave me a much needed boost of energy. I started to focus on what lay ahead. At this critical juncture, we must regroup, reassess and re-strategize. If it meant retreating from other protest sites to fortify the stronghold in Admiralty, then that’s what we would do. Whatever our next move might be, we must stay a few steps ahead of our opponents. We must not lose faith in our cause and play into the hands of the mobs. We must remember, no matter how grim things may look at the moment, that the night is always darkest before dawn.

A gift that is worth its weight in gold

A gift that is worth its weight in gold

Published on October 04, 2014 09:21

October 2, 2014

Worst of Times, Best of Times 最壞的時代 最好的時光

It was Day 3 of Occupy Central, now known across the globe as the Umbrella Revolution. Umbrellas and raincoats, perhaps the humblest of all household objects, have been thrust onto the world stage, as have the tens of thousands of teenage students who had used them to fend off a police crackdown on Sunday. Tonight, their trusty rain gear would be needed once again – the Hong Kong Observatory had just issued the “amber” rain alert for the coming thunderstorm.

A transformational experience for Hong Kong

A transformational experience for Hong KongI changed out of my work clothes in the office and walked to Admiralty, the de factonerve center of the student-led movement demanding the right to choose our own leader. I spotted my brother Kelvin and his wife deep in the crowd. They were listening quietly to a student speaker at the microphone. It was a small miracle that I found the two, as they were swarmed by people as far as the eyes could see, all dressed in black. No one knew how many more had come out tonight – nor did anyone really care. Public turnout normally matters a great deal to protest organizers because it is a measure of their success. But not this time. This time we don’t need a number to tell us that.

A few minutes into our sit-in, volunteers carrying plastic bags stopped by and offered us crackers and tissue paper. There were dozens of them patrolling up and down the aisle, handing out anything from snacks and drinks to paper fans and face towels. Others were collecting garbage and cooling down the crowds with mist sprayers. I felt parched from the stifling heat and asked for water. Five people jumped at my request and came charging toward me with water bottles. I took one from the student nearest me, who then thanked me for accepting his water and reminded me to recycle the plastic bottle at the drop-off tent down the road.

Hong Kong has never been more beautiful

Hong Kong has never been more beautifulThere is a renewed sense of neighborhood in Hong Kong, something we haven’t seen since the city transformed from a cottage industry economy to a gleaming financial center. But all over the protest zones – in Admiralty, Central, Causeway Bay and Mongkok – micro-communities have emerged where the air is clean (traffic has all but vanished), people smile (replacing that permanent frown from big city stress) and everyone helps each other without wanting anything in return (we have a bad rap among fellow Asians for being calculating). This is the Hong Kong we love and miss. This is the Hong Kong I grew up in.

Suddenly, we heard loud claps of thunder and it started to pour. Umbrellas popped open like a time-lapse video of flowers in bloom. Everyone stayed where they were, as raincoats and more umbrellas began to circulate among the crowds. Someone joked that the gods were coming for CY Leung and we all laughed. Once the storm passed, volunteers spontaneously deployed brooms and squeegees to remove water puddles. There were no leaders to give orders, because none was needed. Since the Sunday crackdown, Occupy Central has evolved into a bottom-up campaign based on the self-discipline and volunteerism of individual citizens. No wonder the foreign press has dubbed this “the most civilized street protest in the world.” Our tourism board spends tens of millions every year promoting Hong Kong as “Asia’s World City.” Ironically, all it took to put us on the world map was a bunch of teenagers doing what was natural to them. This place is much more than just shopping malls and restaurants – we now have our young people to brag about.

The world's nicest protestors

The world's nicest protestorsAt the urging of a student patrol, we left jam-packed Admiralty and moved west toward Central where there was more space. Along the Connaught Road expressway, cloud-hugging skyscrapers, those modern cathedrals of glass and steel, stood guard. But they looked strangely out of place tonight, as were the shiny sports cars trapped in the nearby City Hall parking garage. This latest turn of events has forced all of us to take a long, hard look at a way of life predicated on the assumption that social progress means greater affluence and more development. But affluence for whom and development for what? Have any of these 80-story buildings and double-digit retail spending growth made us better people, people who are half as generous and benevolent as the student protestors? Or half as happy?

At the Ice House Street intersection, a crowd gathered to listen to a crash course on what to do if they get pepper-sprayed by police. “Don’t douse water all over your face or else the water carrying the chemicals will drip down your body and irritate your skin,” the 19-year-old university student warned. “Do this instead.” She expertly demonstrated how to tilt the head to one side and rinse the eyes using a capful of water. “And one more thing,” she continued, “you are now at the westernmost frontier of the Central occupation. It is my duty to warn you about your liability should you get arrested for illegal assembly.” After she finished, the audience clapped and broke up into small groups. There were casual conversations about the Sunday crackdown and the government’s next move. What were once talk-of-the-town topics like the new iPhone 6 and tabloid rumors about actor Nicolas Tse are now completely irrelevant. Even Facebookwalls received a facelift: food porn, selfies and narcissistic rants have all given way to protest updates and stories of random acts of kindness.

Three days in, the Umbrella Revolution has already elevated the intellect of an entire generation. In all, it took 87 canisters of tear gas to jolt our youths out of their political apathy. Many now realize that politics affects them personally and that the subject is not as untouchable as their parents and peers had made it out to be. They also realize that video games, karaoke and television shows may have been social anesthesia designed to divert their attention from what matters and turn them into a bunch of fai tsing (廢青; literally, useless youths) who follow rules that they had no part in setting up. Awoken and armed with a new sense of purpose, these students have risen to the occasion and reclaimed their future.

That's the stereotype before this week

That's the stereotype before this weekThese past few days have been my happiest in the nine years since I repatriated to Hong Kong. I have visited the protest zones every day, alternating between euphoria and tears of joy. Who would have imagined that one of the city’s darkest chapter has brought out the absolute best in us? Our students have occupied city streets, and by displaying exemplary discipline and world class charisma, they have also occupied the moral high ground. What they are doing is neither an act nor a ploy to manipulate public opinion – it is genuine goodness emanating from within. I feel sorry for friends and family who aren’t in Hong Kong this week, because much of what goes on has to be seen to be believed. Whatever the outcome of the movement is, Hong Kong has already won.

Just a few days ago, the people under the umbrellas were attacking

Just a few days ago, the people under the umbrellas were attackingthe people holding the umbrellas with tear gas and pepper spray

Published on October 02, 2014 00:08

September 28, 2014

Six Hours in Admiralty 金鐘六小時

I gathered a few essentials – cell phone, notebook, pen, face towel and eye goggles – and left my apartment. I met up with my brother Kelvin at Lippo Centre and we walked to the section of the Connaught Road expressway that had been taken over by protestors and regular citizens who supported them. We were about 50 meters from the government offices, the epicenter of a massive student protest and the frontline of a police standoff.

It was 3:45pm. By then, there were throngs of people all around us, many wearing goggles and raincoats to guard against pepper spray. Some put saran wrap around their eye-gear for extra protection. Tanya Chan (陳淑莊), vice chairwoman of the Civic Party, was speaking into a bullhorn. A student wove through the crowd with a loudspeaker broadcasting her words. Chan asked citizens to hold the line outside the Bank of China tower to stop police from advancing. She also warned us about undercover cops collecting intelligence from the crowds. “Strike up a conversation with anyone who looks suspicious,” she said.

[image error] The tank-man of Hong Kong

From afar, someone yelled “Saline water! We need saline water!” Other supplies were needed too: face masks, umbrellas and drinking water. My brother and I went to see what we could do to help. We joined the human chain passing supplies from one side of Connaught Road to the other. They were for student protestors who had been pepper-sprayed by police. The girl next to me, who was about 15, shoved a carton of fresh milk into my hand. “Pass it on,” she said. Milk is supposed to sooth the eyes because it neutralizes the chemicals in the pepper spray. There was order in this chaos: everyone was a commander and everyone was a foot soldier.

We hit a lull in the calls for supplies. I told Kelvin I needed to use the bathroom and we walked to a nearby shopping mall. On our way back, I proposed to grab a few supplies for the frontline. My brother had overheard that saline water was most needed, and so we spent the next 45 minutes scouring Wanchai for pharmacies, because other volunteers had already emptied the shelves in the vicinity.

It started so peacefully

It started so peacefully

As we were paying for saline water at a local drugstore, we saw a text message on our phones. “Police has just fired tear gas into the crowds!” The text was from my sister-in-law who was monitoring the latest developments from her home. We sensed the gravity of the situation and began running with our purchases back to Admiralty. As we approached Connaught Road, we heard harrowing accounts from students who had retreated from the frontline. A young man said, “The police hoisted a black banner, and we had never seen a black banner before. Now we know: black means tear gas.” The girl next to him chimed in, “It stung like hell.” Many started cursing at the police officers standing guard by the sidewalk. “Have you all gone mad?” shut one person. “How could you do this to our defenseless students? Don’t you have children of your own?” asked another.

Over the next hour, we kept hearing shots being fired, boom boom boom, like fireworks in Chinese New Year. The use of tear gas had caught the city by surprise. If you follow local news, you would know about the famous episode at the 2012 chief executive election, when the then-candidate CY Leung was accused during a televised debate by his opponent Henry Tang of once proposing that riot police and tear gas be unleashed on protestors. Leung vehemently denied it at the time, but it looked like he had just fulfilled the prophecy.

[image error] "You lie! You said it!"

Tear gas might have been commonplace elsewhere in the world, but it isn’t in Hong Kong. Leung’s decision to deploy it, despite the political price he must pay, suggests that he has been given direct orders from Beijing to do whatever it takes to clear the streets before citizens return to work Monday morning. In so doing, however, he has irreversibly redrawn the relationship between people and government. There is no turning back now – neither for him nor for us.

As night fell, tension rose. My brother and I moved to a footbridge outside the Police Headquarters on the ominously named Arsenal Street. There, high above the ground, we saw a formation of armed riot police advancing steadily from Wanchai toward Admiralty. Lit only by the amber streetlights, the scene was eerily reminiscent of the streets of Beijing on that fateful June night 25 years ago. Many on the bridge spontaneously screamed at the people down below: “Run! Riot police is coming! Run!” That’s when I saw one of the police officers unfold the infamous black banner. Moments later, shots of tear gas began arcing through the dark sky, before clouds of white smoke billowed from the ground. It smelled like something between burned rubber and a very pungent mustard. Pandemonium ensued. A stranger came up to me and my brother and said, “You two need these,” and handed us two face masks. My eyes started to sting and I put on my eye goggles. We ran with the retreating crowd and took shelter from the nearby park.

[image error] This is not the Hong Kong I knew

It was 9:30pm and Kelvin and I agreed that we should heed the student organizers’ warning and leave for our own safety, as there were rumors that riot police would start dispersing the crowds with rubber bullets. Kelvin lives in Wanchai and I Pokfulam. We said goodbye to each other and parted ways. By then almost every road between Wanchai and Central had been blocked, either by police or by makeshift blockades set up by students. I walked three kilometers to Sai Ying Pun, before finding a taxi to take me home. During my 30-minute walk, a single thought kept running through my head: this is not the Hong Kong I knew. Perhaps years later we would all look back on this night and tell ourselves that this was good for us. Like bitter Chinese medicine, what went down today has made us stronger and better. But like bitter Chinese medicine, it was very difficult to swallow.

I got home, which had never felt safer or quieter. I said a prayer for those who had chosen to stay in Admiralty – students who had nothing to defend themselves with but umbrellas and face masks. I took a shower and sat idly in bed. Suddenly, all that had happened in the last six hours hit me, as images and sounds finally sank in. I started to sob, and my hands shook despite myself. I wiped my eyes, turned on my computer and wrote this.

It was 3:45pm. By then, there were throngs of people all around us, many wearing goggles and raincoats to guard against pepper spray. Some put saran wrap around their eye-gear for extra protection. Tanya Chan (陳淑莊), vice chairwoman of the Civic Party, was speaking into a bullhorn. A student wove through the crowd with a loudspeaker broadcasting her words. Chan asked citizens to hold the line outside the Bank of China tower to stop police from advancing. She also warned us about undercover cops collecting intelligence from the crowds. “Strike up a conversation with anyone who looks suspicious,” she said.

[image error] The tank-man of Hong Kong

From afar, someone yelled “Saline water! We need saline water!” Other supplies were needed too: face masks, umbrellas and drinking water. My brother and I went to see what we could do to help. We joined the human chain passing supplies from one side of Connaught Road to the other. They were for student protestors who had been pepper-sprayed by police. The girl next to me, who was about 15, shoved a carton of fresh milk into my hand. “Pass it on,” she said. Milk is supposed to sooth the eyes because it neutralizes the chemicals in the pepper spray. There was order in this chaos: everyone was a commander and everyone was a foot soldier.

We hit a lull in the calls for supplies. I told Kelvin I needed to use the bathroom and we walked to a nearby shopping mall. On our way back, I proposed to grab a few supplies for the frontline. My brother had overheard that saline water was most needed, and so we spent the next 45 minutes scouring Wanchai for pharmacies, because other volunteers had already emptied the shelves in the vicinity.

It started so peacefully