Terri Windling's Blog, page 41

April 1, 2020

The alchemy of wintering

Following on from yesterday's post:

In her new book Wintering, Katherine May discusses the dark, frozen seasons we pass through in life, and how we survive and even thrive in them, accepting the unique gifts that they give us. Here in the northern hemisphere, nature is moving from winter to spring -- but the consequences of a global pandemic (the isolation of lock-down, the loss of work and income, the trials of illness, the anxiety caused by an uncertain future) is a form of "wintering" shared by millions all over the world. Embracing this wintertime of the psyche, absorbing the lessons of slow, pared-down days, focusing our technology-fractured attention on what is essential, might allow us to turn the straw of crisis into the magical gold of transformation: healing our broken connection to the natural world and our place within it.

"Our knowledge of winter is a fragment of childhood," writes May, "almost innate: we learn about it in the surprising cluster of novels and fairy tales that are set in snow. All the careful preparations that animals make to endure the cold, foodless months; hibernation and migration, deciduous trees dropping leaves. This is no accident. The changes that take place in winter are a kind of alchemy, an enchantment performed by ordinary creatures to survive: dormice laying on fat to hibernate; swallows navigating to South Africa; trees blazing out the final weeks of autumn. It is all very well to survive the abundant months of the spring and summer, but in winter we witness the full glory of nature flourishing in lean times.

"Our knowledge of winter is a fragment of childhood," writes May, "almost innate: we learn about it in the surprising cluster of novels and fairy tales that are set in snow. All the careful preparations that animals make to endure the cold, foodless months; hibernation and migration, deciduous trees dropping leaves. This is no accident. The changes that take place in winter are a kind of alchemy, an enchantment performed by ordinary creatures to survive: dormice laying on fat to hibernate; swallows navigating to South Africa; trees blazing out the final weeks of autumn. It is all very well to survive the abundant months of the spring and summer, but in winter we witness the full glory of nature flourishing in lean times.

"Plants and animals don't fight the winter; they don't pretend it's not happening and attempt to carry on living the same lives they lived in the summer. They prepare. They adapt. They perform extraordinary acts of metamorphosis to get them through. Winter is a time of withdrawing from the world, maximising scant resources, carrying out brutal acts of efficiency and vanishing from sight; but that's where transformation occurs. Winter is not the death of the life cycle, but its crucible.

"Once we stop wishing it were summer, winter can be a glorious season when the world takes on a sparse beauty, and even the pavements sparkle. It's a time for reflection and recuperation, for slow replenishment, for putting your house in order....

"Doing those deeply unfashionable things -- slowing down, letting your spare time expand, getting enough sleep, resting -- are radical acts these days. This is a crossroads we all know, a moment when you need to shed a skin. If you do, you'll expose all those painful nerve endings, and feel so raw that you'll need to take care of yourself for a while. If you don't, then that old skin will harden around you.

"It's one of the most important choices you'll ever make."

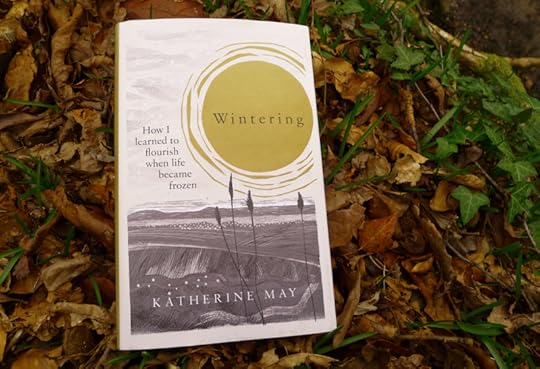

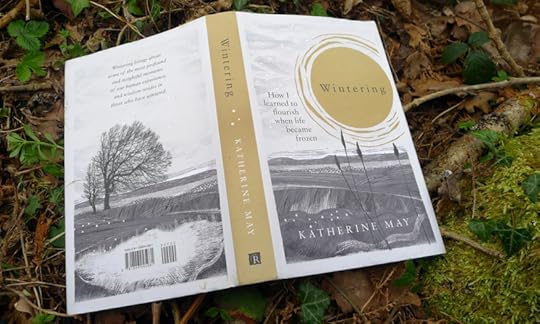

Words: The passage above is from Wintering: How I Learned to Flourish When Life Became Frozen by English novelist/memoirist Katherine May (Penguin/Random House, 2020).

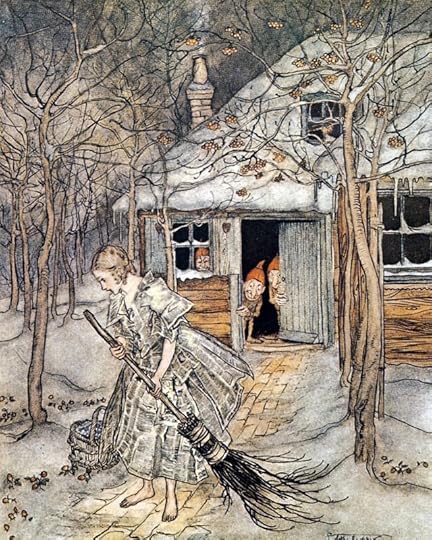

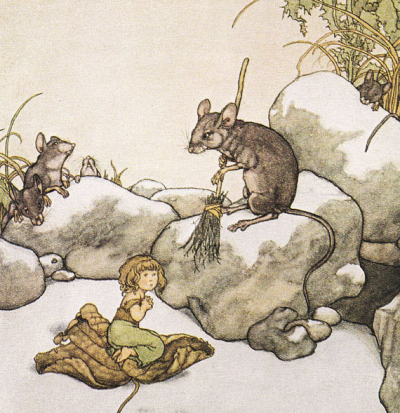

Wintery fairy tale art from the Golden Age of Illustration: "Gerda and the Reindeer" by Edmund Dulac, "Thumbelina" by William Heath Robinson, "East of the Sun, West of the Moon" by Kay Nielsen, "Strawberries in the Snow" by Arthur Rackham, and "She Kissed the Bear on the Nose" by John Bauer.

March 31, 2020

Signs of spring

Here's the first foal to be born to our local herd of Dartmoor ponies this year. We're so lucky to be in lock-down in Devon, where sights like this lift my heart. I send it out in the hope it will lift yours too.

"They are the ones who never pass a secret place in the woods without a stare of curiosity for the mystery implied in all its mounds and hollow, who still turn corners with a lift of expectation at the heart. And to be a writer of fantasy, one must be among those few -- those fortunate few; for, to produce a work that answers all the demands of fantasy, is to suddenly turn the corner which does at last show something strange and wonderful waiting to be seen, and -- most gloriously -- to know that long-ago sense of yearning at last fulfilled."

"Someone needs to tell those tales. When the battles are fought and won and lost, when the pirates find their treasures and the dragons eat their foes for breakfast with a nice cup of Lapsang souchong, someone needs to tell their bits of overlapping narrative. There's magic in that. It's in the listener, and for each and every ear it will be different, and it will affect them in ways they can never predict. From the mundane to the profound. You may tell a tale that takes up residence in someone's soul, becomes their blood and self and purpose. That tale will move them and drive them and who knows what they might do because of it, because of your words."

''And I think that now, in our age, in the mid-ocean of our days, with certainties collapsing around us, and with no beliefs by which to steer our way through the dark descending nights ahead -- I think that now we need those fictional old bards and fearless storytellers, those seers. We need their magic, their courage, their love, and their fire more than ever before. It is precisely in a fractured, broken age that we need mystery and a reawoken sense of wonder. We need them to be whole again.''

- Ben Okri

Wintering

Here in Devon, we're on the cusp of spring (daffodils in the woods, new lambs in fields, wild Dartmoor ponies beginning to foal), but I'm reading a book about about winter right now and finding it full of interest. Wintering by Katherine May explores the winter season metaphorically (as a symbol for those hard times in life that I refer to as the Dark Forest), as well as the actuality of winter as it is experienced in northern climes. She weaves her meditations on the cold and dark with a personal memoir about her own period of "wintering," when illness in her family -- first her husband's, and then her own -- shook every foundation they had built their lives on.

"There are gaps in the mesh of the everyday world," May writes, "and sometimes they open up and you fall through them into Somewhere Else. Somewhere Else runs at a different pace to the here and now, where everyone else carries on. Somwhere Else is where ghosts live, concealed from view and only glimpsed by people in the real world. Somewhere Else exists at a delay, so that you can't quite keep pace. Perhaps I was already teetering on the brink of Somewhere Else anyway; but now I fell through, as simply and discreetly as dust sifting between the floorboards."

"Everybody winters at one time or another," she explains; "some winter over and over again.

"Wintering is a season in the cold. It is a fallow period in life when you're cut off from the world, feeling rejected, sidelined, blocked from progress, or cast into the role of the outsider. Perhaps it results from an illness; perhaps from a life event such as a bereavement or the birth of a child; perhaps it comes from a humilation or failure. Perhaps you're in a period of transition, and have temporararily fallen between two worlds. Some winterings creep upon us, accompanying the protracted death of a relationship, the gradual ratcheting up of care responsibilities as our parents age, the drip-drip-drip of lost confidence. Some are appallingly sudden, like discovering one day that your skills are considered obsolete, the company you worked for has gone bankrupt, or your partner is in love with someone new. However it arrives, wintering is usually involuntary, lonely and deeply painful.

"Yet it's also inevitable. We'd like to imagine it's possible for life to be one eternal summer, and that we have uniquely failed to achieve that for ourselves. We dream of equatorial habits, forever close to the sun; an endless, unvarying high season. But life's not like that. Emotionally, we're prone to stifling summers and low, dark winters, to sudden drops in temperature, to light and shade. Even if, by some extraordinary stroke of self-control and good luck, we were able to keep control of our own health and happiness for an entire lifetime, we still couldn't avoid the winter. Our parents would age and die; our friends would undertake minor acts of betrayal; the machinations of the world would eventually weigh against us. Somewhere along the line, we would screw up. Winter would quietly roll in....

"In our relentlessly busy contemporary world, we are forever trying the defer the onset of winter. We don't ever dare to feel its full bit, and we don't dare to show the way that it ravages us. A sharp wintering, sometimes, would do us good. We must stop believing that these times in our life are somehow silly, a failure of nerve, a lack of willpower. We must stop trying to ignore them or dispose them. They are real, and they are asking something of us. We must learn to invite winter in."

That's what her new book is about, May says: "learning to recognize the process, engage with it mindfully, and even to cherish it. We may never choose to winter, but we can choose how."

I recommend this wise and beautiful text for those going through their own wintering...which I expect may be a lot of us now, facing the life-altering consequences imposed by a global pandemic.

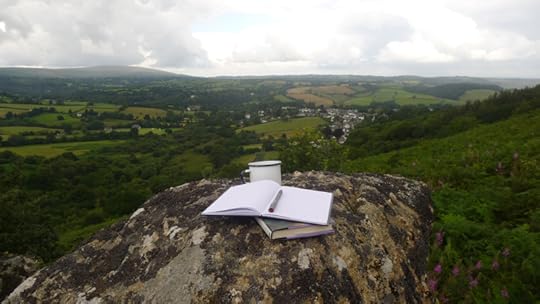

As the Great Wheel turns from winter to spring, I've been contemplating my own winterings and the gifts they have given me, over and over. Those gifts are going to be useful now as we cope with unimaginable challenges ahead. Eager for springtime's warmth and sun, I celebrate each flower, each lamb, each foal affirming the steady turning of the seasons....

But I'm also grateful for the dark and cold, and the lessons of slowness, of quiet, of healing.

Words: The passage above is from Wintering: How I Learned to Flourish When Life Became Frozen by English novelist/memoirist Katherine May (Penguin/Random House, 2020). The poem in the picture captions is from Fugitive Colours by Scottish poet Liz Lochhead (Polygon, 2016). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Our local herd of Dartmoor ponies, many of them pregnant with this year's foals. I love encountering them on walks with Tilly, grazing on the village Commons and roaming the hills behind my studio.

March 30, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

To start with, above: "Seven Songs on Six Islands," a little film by Myles O'Reilly, featuring brothers Br��an & Diarmuid Mac Gloinn of Ye Vagabond. This one is for everyone locked down at home, for whom a trip through six Irish islands might be particularly welcome right now. (O'Reilly is doing wonderful work documenting the contemporary Irish folk music scene, by the way. To support him on Patreon, go here.)

Above: "Reels" from the Scottish band Westward the Light (Charlie Grey, Catriona Hawksworth, Joseph Peach, and Owen Sinclair). Their self-titled debut album has just been released.

Below: "Encore" by Westward the Light.

Above: "Mountain of Gold" by the Scotland-based trio Salt House ( Jenny Sturgeon, Lauren MacColl, and my Modern Fairies colleague Ewan MacPherson), from their new album Huam. Their previous album, Undersong, has been constantly on our CD player, and it's clear that this one is going to be too.

Below: "Fire Light," also from Huam. Please don't miss this gorgeous music.

Pictures: Tilly and me on the south Devon coast a while back. Dartmoor is a beautiful place to be locked down, so I'm not complaining...but I keep dreaming of the sea.

March 28, 2020

The gift of stillness

In A Book of Silence, Sara Maitland explores the cultural history of silence and retreat while seeking to create more room for silence within her own life. It's a fascinating book, leading through myth, religion, philosophy, sociology, natural history and literature to a place of stillness at the center of them all. As life slows down in response to the global pandemic, particularly for those of us in lock-down and other forms of isolation, the practice of retreat takes on new meaning. What gifts might a slower life give us? And what does silence have to teach us?

Early on in her quest for silence, Maitland arranged to spend forty days alone at Allt Dearg, a remote cottage on An t-Eilean Sgitheanach, Scotland's Isle of Skye, noting the changes in her psyche and imagination as the weeks went by and her silence and solitude deepened. Describing the last days of her time on the island, she says: "Part of me had already moved on from Allt Dearg, and another part of me never wanted to leave. The weather became appalling so that I could not go out for a final walk or round off the time with any satisfying sense of closure. I had to clean the house and then drive a long way. I had felt quite depressed for about forty-eight hours...

"...and then, the very final evening, I suddenly was seized with an overwhelming moment of jouissance. I wrote:

'They say it is not over till the fat lady sings. Well, she is singing now. She is singing in a wild fierce wind -- and I am in here, just. Now I am full of joy and thankfulness and a sort of solemn and bubbling hilarity. And gratitude. Exultant -- that is what I feel -- and excited, and that now, here, right at the very edge of the end, I have been given back my joy.'

"For several hours I enjoyed an extraordinary rhythmical sequence of emotions -- great waves of delight, gratitude, and peace; a realization of how much I had done in the last six weeks, how far I had traveled; a powerful surge of hope and possibility for myself and my future; and above all a sense of privilege. But also a nakedness or openness that needed to be honored somehow.

"I experienced a fierce joyful ... joyful what? ... neither pride nor triumph felt like the right word. Near the end of Ursula Le Guin's The Farthest Shore (the third part of The Earthsea Trilogy), Arren, the young prince-hero, who has with an intrepid courage born of love rescued the magician Sparrowhawk, and by implication the whole of society, from destruction, wakes along on the western shore of the island of Selidor: He smiled then, a smile both somber and joyous, knowing for the first time in his life, and alone, and unpraised and at the end of the world, victory.

"That was what I felt like, alone on An t-Eilean Sgitheanach, The Winged Isle. I felt an enormous victorious YES to the world and to myself. For a short while I was absorbed in joy. I was dancing my joy, dancing, and flowing with energy. At one point I grabbed my jacket, plunged out into the wind and the storm. It was physically impossible to stay out for more than about a minute because the wind and rain were so strong and I came back in soaked even from that brief moment; but I came back in energized and laughing and exulting as well. I was both excited and contented. This is a rare and precious pairing. I knew, and wrote in my journal, that this would not last, but it did not matter. It was NOW. At the moment that now, and the enormous wind, felt like enough. Felt more than enough.

"And once again," Maitland concludes, "I am not alone. Repeatedly, in every historical period, from every imaginable terrain, in innumerable different languages and forms, people who go freely into silence come out with slightly garbled messages of intense jouissance, of some kind of encounter with nature, their self, their God, or some indescribable source of power."

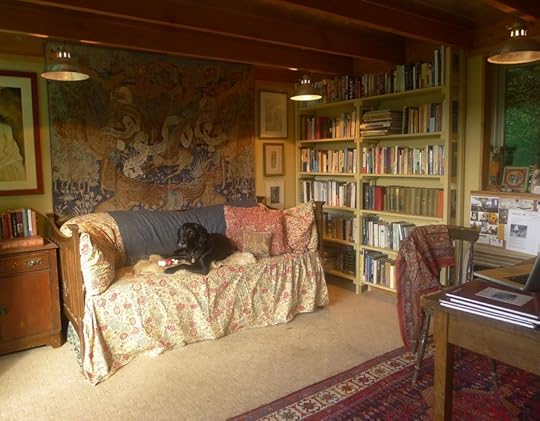

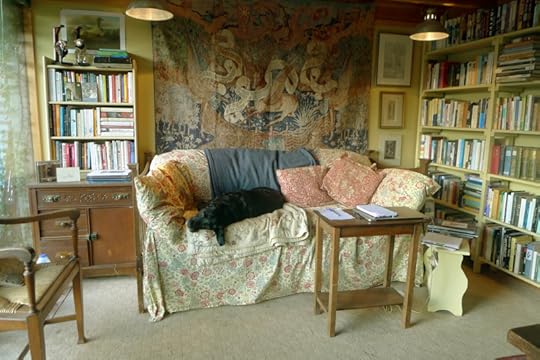

I first read Maitland's A Book of Silence some years ago, when confined to bed by health problems. I was not alone -- I had Tilly snuggled at my side, and my gentle husband nearby -- but the quiet and stillness of recovering from an illness can be another form of retreat from the rapid rhythms of the noisy modern world. There were long hours when the only sounds were Tilly's snores, the rustle of a book's turning page, rain or bird song outside the window glass. Like a spiritual retreat or pilgrimage, illness takes us deep inside ourselves, shaking away all other concerns except those of the body, those of the soul. Afterwards, I always return to life changed. The world is restored to me piece by piece, with each step noted and celebrated: the first hour out of bed; the first morning outdoors, tucked up in a blanket on the garden bench; the first slow climb to my studio on the hill; the first shaky walk in the woods with Tilly. There's a joy in all this that we rarely speak about, as if to admit that there's any pleasure or value in illness might be to dismiss its overwhelming difficulties. We'd all prefer, of course, to plan our times of retreat, not to have them forced upon us by physical collapse, overshadowed by pain or fear. But there is a gift to be found in illness...and perhaps in our current pandemic lock-down as well: the gift of long hours of quiet and stillness, precious and rare in these fast-paced times.

And when this time of enforced retreat is done, we may find it has given us these gifts too: jouissance, wonder, and fresh gratitude for our fragile bodies, our fleeting lives, and the exquisite beauty of the world we return to.

Photographs: Tilly on the north Devon coast. When will we see that beach again?

Photographs: Tilly on the north Devon coast. When will we see that beach again?

March 27, 2020

The Dark Forest

In late January, Howard and I gave a talk here in Chagford titled The Path Through the Dark Forest, discussing how myth and mythic fiction can help us through challenging times. Little did we know how appropriate the subject would be in the months ahead....

A journey through the dark of the woods is a common motif in fairy tales: young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach their destiny, or they find themselves abandoned there. The road is long and treacherous, prowled by ghosts, ghouls, wicked witches, wolves and the more malign sorts of faeries....but helpers also appear on the path: wise crones, good faeries, and animal guides, often cloaked in unlikely disguise. The hero's task is to tell friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

"When you enter the woods of a fairy tale, and it is night, the trees tower on either side of the path," writes Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew. "They loom large because everything in the world of fairy tales is blown out of proportion. If the owl shouts, the otherwise deathly silence magnifies its call. The tasks you are given to do (by the witch, by the stepmother, by the wise old woman) are insurmountable -- pull a single hair from the crescent moon bear's throat; separate a bowl's worth of poppy seeds from a pile of dirt. The forest seems endless. But when you do reach the daylight, triumphantly carrying the particular hair or having outwitted the wolf; when the owl is once again a shy bird and the trees only a lush canopy filtering the sun, the world is forever changed for your having seen it otherwise."

At the time of our talk, my own path was sunny and clear...but then the road dipped and plunged into the dark pines. I spent a few weeks in the forest's undergrowth while coping with serious health issues, and just as the road seemed to clear once again, I learned that my youngest brother had died, in a way that was sudden, shocking, and desperately sad. The next weeks were a blur, overwhelmed by the numerous tasks that the death of a loved one requires -- complicated by my great distance from the small Texas town where my brother had died, yet eased by the steady support of friends (both my brother's and mine, many blessings upon them all). As those heartbreaking tasks finally came to an end, I emerged from a haze of grief to find Corvid-19 spreading across Europe. Now the whole of Britain has gone into lock-down, while virus infection rates rise and rise.

Howard was meant to be in Berlin right now, as part of his year-long "Journey Into the Heart of the Fool." Just two weeks ago we were still debating whether it was wise for him to travel or not -- but life changes fast, and our decision to keep him home quickly proved to be the right one. Between his teaching/directing work, Fool training and PhD studies, he's been on the road a lot this year -- which has all ground to a halt as theaters and universities shut their doors. The loss of work is a worry, of course; but I'm deeply relieved that he's home with us. (And the hound is over the moon to have him back.)

As those of you who are also on lock-down know, daily life is now full of practical and emotional challenges; each day seems to bring brand new ones, and nothing has settled yet into a routine. I don't discount the gravity of those challenges (those of us with "high risk" medical conditions know full well the danger we're facing), but the questions I want to focus on here on Myth & Moor are these: How do we create thoughtful and artful lives despite that danger? How do live through the hard days ahead as artists?

For me, these are not unfamiliar questions. My particular health condition affects my immune system, so I'm already used to periods of self-isolation. I'm used to putting time and thought each day into the practical business of staying alive, and of taking mortality seriously. For many of us with a range of illnesses to manage, this is already familiar territory, so perhaps we can be of particular help now to those for whom such concerns are new. We know how to live in the shadow of death. We know how to let fear and joy co-exist inside us. We've learned to live without certainty. We've learned to accept we're not in full control. We've learned to keep working, to keep creating, to keep showing up and to live fully in the present. Just as important, we've learned to forgive ourselves on those hard, weary, painful days when we simply can't.

Because I'm writer and scholar of stories, it's to stories I turn when the going gets rough. It's through stories I find the tools I need: imagination, wonder, beauty, compassion for others, compassion for myself, courage, persistence, understanding, discernment...and narratives that make sense of it all.

In Wonder and Other Survival Skills, H. Emerson Blake argues for the cultivation of "wonder" especially:

"The din of modern life constantly pulls our attention away from anything that is slight, or subtle, or ephemeral," he says. "We might look briefly at a slant of light while walking through a parking lot, but then we're on to the next thing: the next appointment, the next flickering headline, the next task, the next thing that has to be done before the end of the day. But maybe it's for just that reason -- how busy we are and distracted and connected we are -- that wonder really is a survival skill. It might be the thing that reminds us of what really matters, and of the greater systems that our lives are completely dependent on. It might be be the thing that helps us build an emotional connection -- an intimacy -- with our surroundings that, in turn, would make us want to do anything we can to protect them. It might build our inner reserves, give us the strength to turn ourselves outward and meet those challenges with grace.

"In a day and age when we are reminded unendingly of the urgency and magnitude of the problems we face, wonder may seem like something we no longer have time for -- a luxury, or a dalliance. But in one of Orion's live web events, David Abram said this:

'When we trivialize people's sensory attachment to the beauty of their place, to the beauty of the land where they live...we need to at least be aware that it is undermining peoples' sense of solidarity to the rest of the earth. Sensory perception is the glue that binds our separate nervous systems into the encompassing ecosystem.'

"In other words, Abram ties our terrible, selfish decision-making about how we treat the earth -- what we take from it, what we put into it, what we demand of it -- directly to our estrangement from its beauty. He is saying that wonder is the antidote. That wonder is the thing that can save us."

Myth, folklore, fantasy fiction, and mythic arts are vibrant sources of wonder, and thus good medicine for these troubled times. We must keep creating such stories, and sharing such stories, for wondrous tales are not frivolous things. When created with heart, honesty, and skill, they are fresh water and bread to sustain us.

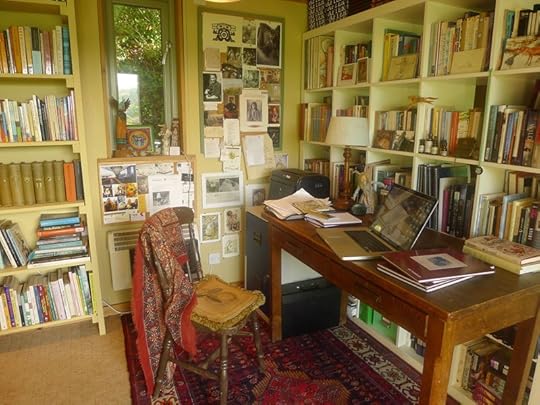

In the days ahead, I'm going to talk about some of the books that I have carried with me through the deep dark forest, highlight art that shines silver light on the path, and share (as always) the magic and beauty of the land here on Dartmoor's edge. I'm also going to re-visit old posts that might have something new to tell us right now: on living slowly, on living rooted in "place," and on embracing the quieter rhythms of life that a pandemic lock-down requires.

I hope you will share your own stories here too, in the Comments section below each post. How are you doing? How are you coping? Are you still creating...and if so, how? And if not, why? (No judgements on the latter, I promise; just community and solidarity.)

"[W]hile the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new," wrote the great James Baldwin, "it always must be heard. There isn���t any other tale to tell, it���s the only light we���ve got in all this darkness."

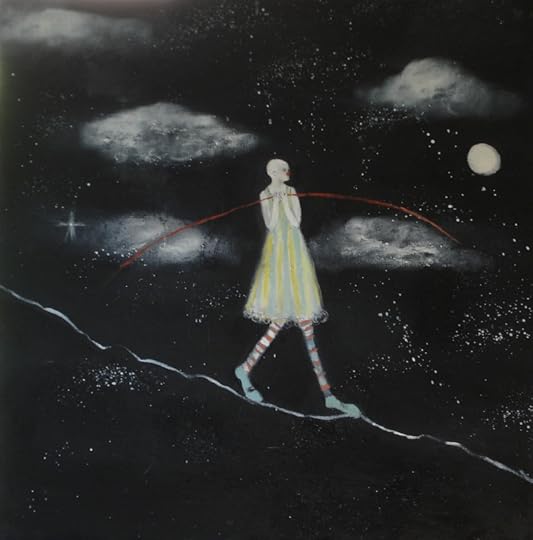

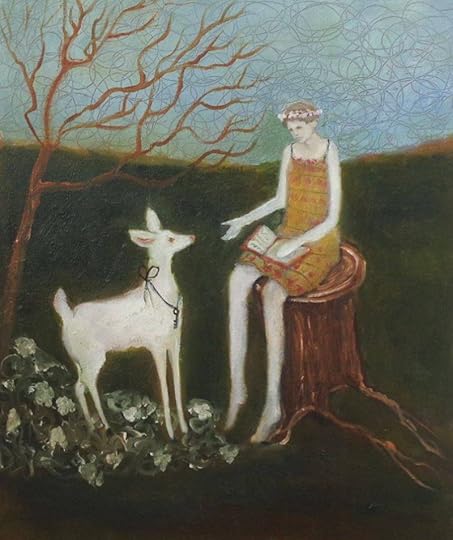

Pictures: The art above, of course, is by the wonderful American painter Jeanie Tomanek. All rights reserved by the artist. Please visit her website to see more.

March 26, 2020

In gratitude during perilous times

''There are so many unsung heroines and heroes at this broken moment in our collective story, so many courageous persons who are holding together the world by their resolute love or contagious joy. Although I do not know your names, I can feel you out there.''

- David Abram (Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology)

March 25, 2020

Myth & Moor update

Friends have been urging me to stop apologizing for my absence from Myth & Moor due to circumstances beyond my control (health issues and a death in my family), but I can't help it. I am sorry that I haven't been here with you during the worldwide spread of Covid-19, when daily posts from the Dartmoor countryside might have provided some welcome distraction and comfort.

I'm back in the studio now, catching up with work, intending to be with you in a more regular way . . . provided the Little Gods of telephone wires and Internet connectivity are kind to us. Our rural Internet service has always been slow and affected by storms; but lately, with the entire UK on lock-down and demands for connectivity rising, our service has gone from slow to a crawl. We are currently switching service providers, hoping to find a more lasting solution. While we wait for the switch to take place, however, our Internet access remains unpredictable. I'll post when I can, but it's likely to be erratic -- and that's another thing beyond my control. Okay, I won't apologize again, but I do thank you for your patience.

I'm back in the studio now, catching up with work, intending to be with you in a more regular way . . . provided the Little Gods of telephone wires and Internet connectivity are kind to us. Our rural Internet service has always been slow and affected by storms; but lately, with the entire UK on lock-down and demands for connectivity rising, our service has gone from slow to a crawl. We are currently switching service providers, hoping to find a more lasting solution. While we wait for the switch to take place, however, our Internet access remains unpredictable. I'll post when I can, but it's likely to be erratic -- and that's another thing beyond my control. Okay, I won't apologize again, but I do thank you for your patience.

I also want to say a big thank you to all of you who have kept conversation going here (in the Comments section) while I've been away. Conversation maintains community; and community, to me, is everything.

American naturalist Barry Lopez writes

"Conversations are efforts toward good relations. They are an elementary form of reciprocity. They are the exercise of our love for each other. They are the enemies of our loneliness, our doubt, our anxiety, our tendencies to abdicate. To continue to be in good conversation over our enormous and terrifying problems is to be calling out to each other in the night. If we attend with imagination and devotion to our conversations, we will find what we need; and someone among us will act -- it does not matter whom -- and we will survive."

He is speaking of ecological crisis here, but his words could apply to a global pandemic as well. Coming together in our various communities is how we take care of and nurture each other.

I'm glad to return to this conversation. Stay safe, everyone. And let's keep talking.

Words: The quote is from"Meditations on Living in These Times" by Barry Lopez, published in Hope Beneath Our Feet, edited by Martin Keogh (North Atlantic Books, 2010).

Pictures: A visit with sweet Benji, the elderly horse who lives down the road. The little drawing of Tilly is by her good friend (and ours) David Wyatt.

March 24, 2020

A celebration of slowness

Since self-isolation and lock-down is causing so many of us to slow down the pace of our lives, here's a post from the Myth & Moor archives in praise of slowness, stillness, and moments of quiet....

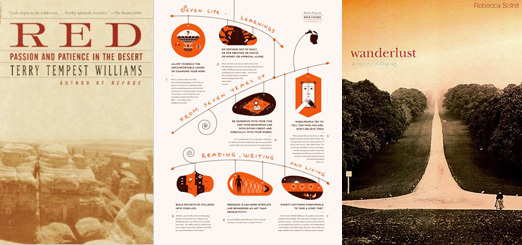

From Rebecca Solnit's Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2001):

"[My friend] Sono's truck had been stolen from her West Oakland studio, and she told me that although everyone responded to it as a disaster, she wasn't all that sorry it was gone, or in a hurry to replace it. There was a joy, she said, to finding that her body was adequate to get her where she was going, and it was a gift to develop a more tangible, concrete relationship to her neighborhood and its residents. We talked about the more stately pace of time one has on foot and on public transportation, where things must be planned and scheduled beforehand, rather than rushed through at the last minute, and about the sense of place that can only be gained on foot. Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors -- home, car, gym, office, shops -- disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than interiors built up against it....

"I had told Sono about an ad I found in the Los Angeles Times a few months ago that I'd been thinking about ever since. It was for a CD-ROM encyclopedia, and the text that occupied a whole page read, 'You used to walk across town in the pouring rain to use our encyclopedias. We're pretty confident that we can get your kid to click and drag.' I think it was the kid's walk in the rain that constituted the real education, at least of the senses and the imagination. Perhaps the child with the CD-ROM encyclopedia will stray from the task at hand, but wandering in a book or a computer takes place within more constricted and less sensual parameters. It's the unpredictable incidents between official events that add up to a life, the incalculable that gives it value. Both rural and urban walking have for two centuries been prime ways of exploring the unpredictable and incalculable, but now they are under assault on many fronts.

"The multiplication of technologies in the name of efficiency is actually eradicating free time by making it possible to maximize the time and place for production and minimize the unstructured travel time between. New time-saving technologies make most workers more productive, not more free, in a world that seems to be accelerating around them. Too, the rhetoric of efficiency around these technologies suggests that what cannot be quantified cannot be valued -- that that vast array of pleasures which fall into the category of doing nothing in particular, of woolgathering, cloud-gazing, wandering, window-shopping, are nothing but voids to be filled by something more definite, more productive, or faster paced....

"The indeterminacy of a ramble, on which much may be discovered, is being replaced by the determinate shortest distance to be transversed with all possible speed, as well as by electronic transmissions that make real travel less necessary. As a member of the self-employed whose time saved by technology can be lavished on daydreams and meanders, I know these things have their uses, and use them -- a truck, a computer, a modem -- myself, but I fear their false urgency, their call to speed, their insistence that travel is less important than arrival. I like walking because it is slow, and I suspect that the mind, like the feet, works at about three miles an hour. If this is so, then modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought, or thoughtfulness."

Solnit returned to the subject of time in an essay for the London Review of Books:

"Nearly everyone I know feels that some quality of concentration they once possessed has been destroyed. Reading books has become hard; the mind keeps wanting to shift from whatever it is paying attention to to pay attention to something else. A restlessness has seized hold of many of us, a sense that we should be doing something else, no matter what we are doing, or doing at least two things at once, or going to check some other medium. It���s an anxiety about keeping up, about not being left out or getting behind. (Maybe it was a landmark when Paris Hilton answered her mobile phone while having sex while being videotaped a decade ago.)

"The older people I know are less affected because they don���t partake so much of new media, or because their habits of mind and time are entrenched. The really young swim like fish through the new media and hardly seem to know that life was ever different. But those of us in the middle feel a sense of loss. I think it is for a quality of time we no longer have, and that is hard to name and harder to imagine reclaiming. My time does not come in large, focused blocks, but in fragments and shards. The fault is my own, arguably, but it���s yours too ��� it���s the fault of everyone I know who rarely finds herself or himself with uninterrupted hours. We���re shattered. We���re breaking up.

"It���s hard, now, to be with someone else wholly, uninterruptedly, and it���s hard to be truly alone. The fine art of doing nothing in particular, also known as thinking, or musing, or introspection, or simply moments of being, was part of what happened when you walked from here to there alone, or stared out the train window, or contemplated the road, but the new technologies have flooded those open spaces."

Later in the piece she wonders

"if there will be a revolt against the quality of time the new technologies have brought us, as well as the corporations in charge of those technologies. Or perhaps there already has been, in a small, quiet way. The real point about the slow food movement was often missed. It wasn���t food. It was about doing something from scratch, with pleasure, all the way through, in the old methodical way we used to do things. That didn���t merely produce better food; it produced a better relationship to materials, processes and labour, notably your own, before the spoon reached your mouth. It produced pleasure in production as well as consumption. It made whole what is broken."

In "7 Things I Learned in 7 Years of Reading, Writing, and Living," Maria Popova notes:

"Presence is far more intricate and rewarding an art than productivity. Ours is a culture that measures our worth as human beings by our efficiency, our earnings, our ability to perform this or that. The cult of productivity has its place, but worshipping at its altar daily robs us of the very capacity for joy and wonder that makes life worth living ��� for, as Annie Dillard memorably put it, 'how we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.' "

Terry Tempest Williams, too, has questioned our culture's emphasis on speed, ease, productivity, and consumption. In her beautiful essay "Ode to Slowness" (Red, 2001), she reflects on her transition from the urban pace of Salt Lake City to the quiet rhythms of a village in the Utah desert, using language that echoes my own transition from Boston and New York City to the Arizona desert and rural England:

"My husband and I were comfortable in our urban routine," she writes," but one night over dinner her said, 'What if we are only living half-lives? What if there is something more?'

"We wanted more.

"We wanted less.

"We wanted more time, fewer distractions. We wanted more time together, time to write, to breathe, to be more conscious with our lives. We wanted to be closer to wild places where we could walk and witness the seasonal changes, even the changing constellations. And so we banked on the idea of a simpler life away from the city near the slickrock country we love. What we would lose in income, we would gain in sanity."

Time, she discovered, (as I, too, discovered), moves differently outside of the city.

"I am not so easily seduced by speed as I once was. I find that I have lost the desire to move that quickly in the world. To see how much I can get done in a day does not impress me any more. I don't think it's about getting older. It feels more like honoring the gravity in my own body in relationship to place. Survival. A rattlesnake coils; its tail shakes; the emptiness of the desert is evoked.

"I want my life to be a celebration of s l o w n e s s ."

As do I. Oh, as do I.

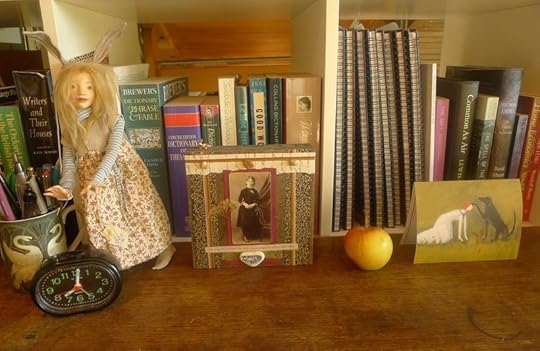

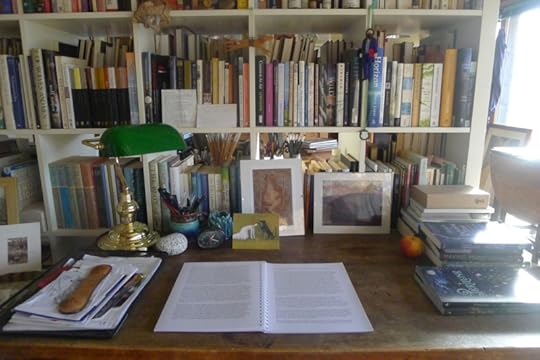

The Bunny Girl on my desk (and in the grass) is by Wendy Froud, the collage art by Lynn Hardaker, and the "woman with dog" card by Jeanie Tomanek. They were gifts, all of them, and much treasured.

March 18, 2020

Myth & Moor update

Thank you for your patience while I've been away dealing with sad family matters. Myth & Moor resumes its publishing schedule tomorrow, and I'll be be catching up on Patreon too (for those of you who subscribe). It's good to be back in the studio.

"The lessons of impermanence taught me this: loss constitutes an odd kind of fullness; despair empties out into an unquenchable appetite for life."

- Gretel Ehrlich (The Solace of Open Spaces)

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers