Terri Windling's Blog, page 44

January 21, 2020

Nature, gnomes, and the power of story

Michael McCarthy begins his beautiful book The Moth Snowstorm with these arresting two sentences: "In the summer of 1954, when Winston Churchill was dwindling into his dotage as British prime minister, the beaten French were withdrawing from Indochina, and Elvis Presley was beginning to sing, my mother's mind fell apart. I was seven and my brother John was eight."

Blending nature writing, ecological history, and memoir, The Moth Snowstorm is narrated in a lucid prose that makes my heart sing even though the story it tells is filled with loss: of family, of innocence, of the natural world McCarthy once in knew in the Wirral near Liverpool. His mother, Norah, had trained as a teacher; his father, Jack, was largely away at sea. When Nora's mind "began to fray" under the weight of her troubles, the stern Canon at their Catholic church recommended her removal to a mental institution, from which (as was usual in those days) no one expected her to return. In fact, she came home just a few months later -- but by then McCarthy's bossy aunt Mary had sold off her sister's home, and taken her two young nephews in charge. John, the eldest, responded to the dramatic break-up of their family with rage and tears, while Michael retreated into indifference. He writes:

"At seven years old, I was not in the least bit concerned that I had lost my mother. How bizarre that seems, written down. Many years on, when I began to talk about it, to try to sort it all out, I learned that this was a Coping Strategy. Golly, I thought. Did I have a Coping Strategy? All I remember having is nothing. Being not bothered, not in the slightest, that she had gone away with no promise of return; and this attitude slumbered inside me through childhood, adolescence and long into manhood, until my mother died, my mother with whom I had by now built bridges and come to adore before all others...and the life I had blithely put together on top of the gaping cracks, pretending they were not there, began to unravel and I set out on the long road to somewhere else."

Aunt Mary and her husband lived in the suburbs. In a nearby garden was a buddleia, and on a late summer morning young Michael found it entirely covered with butterflies: red admirals, peacocks, small tortoiseshells, and painted ladies.

"I was mesmerised. My eyes caressed their colours like a hand stroking a kitten. How could there be such living gems? And every morning in that hot but fading summer, as my mother suffered silently and my brother cried out, I ran to check on them, never tiring of watching these free-flying spirits with wings as bright as flags which the buddleia seemed miraculously to tame, to keep from visiting other flowers, to enslave on its own blooms by its nectar's unfathomable power. I could smell it myself, honey-sweet, but with the faintest hint of a sour edge. Drawing them in, the wondrous visitants. Wondrous? Electrifying, they were. Filling the space where my feelings should have been. And so through this singular window, when I was a skinny kid in short pants, butterflies entered my soul."

Mary obligingly bought him a guidebook to butterflies, and his interest grew from enthusiasm to obsession. Reflecting on this many years later, McCarthy accepts the strangeness of the circumstance, "that it was in a time of great turmoil, involving great unhappiness, that I first became attached to nature; that while my boyhood bond with my mother was being rent asunder, I was preoccupied with insects.

"I might have become a lifelong butterfly obsessive," McCarthy adds, "narrowly and compulsively preoccupied to the exclusion of all else, like Frederick Clegg in John Fowles' The Collector, had not my mother show me a way to a wider world."

Norah was released from the mental hospital that autumn, but it was more than a year before the family had a home of their own again. To mark this new beginning, McCarthy's mother, a devotee of literature, gave him a book.

"It was a Christmas present that year, prompted I imagine by my butterfly enthusiasm; but whereas Mary might have found me another book on Lepidoptera, Norah chose something else, and I wonder now what sure instinct led her to this, the first real story I encountered, with fully formed characters and a narrative; for I engaged with it at once.

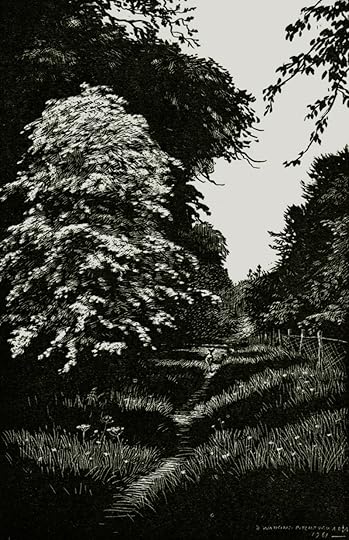

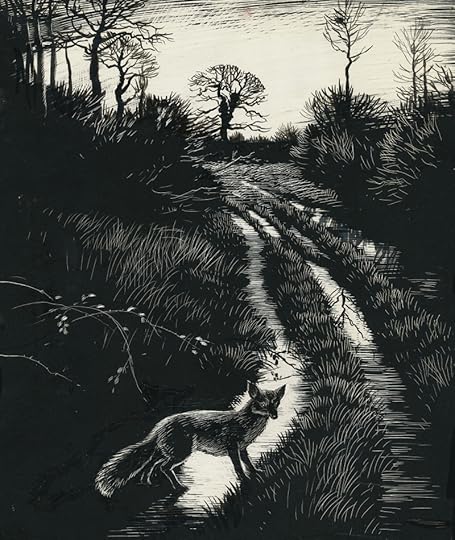

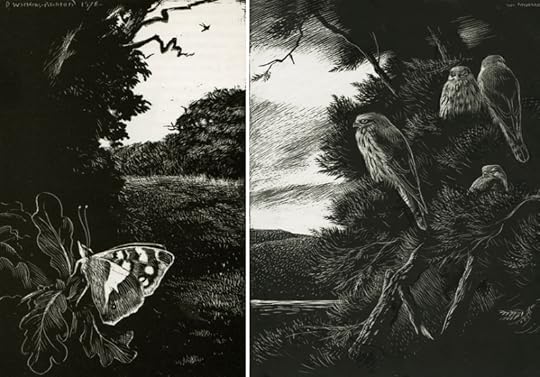

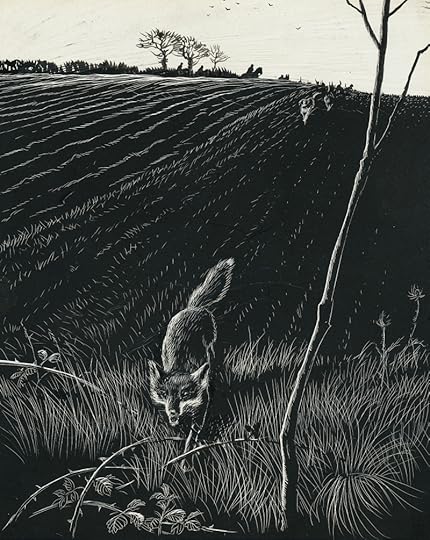

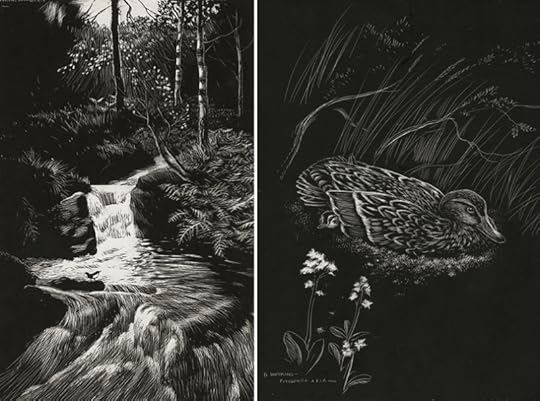

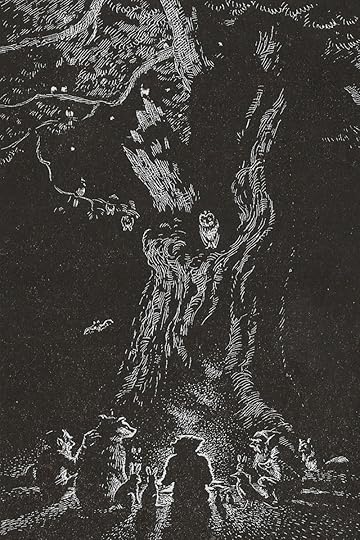

"It was an epic, in the old-fashioned, precise sense of the term: a long account of heroic adventures. But it was not large-scale, in the way that The Iliad and The Odyssey are large-scale epics, mainly because its heroes were gnomes. It was called The Little Grey Men, and its author signed himself merely by initials, BB; his real name was Denys Watkins-Pitchford, although it was years before I found this out.

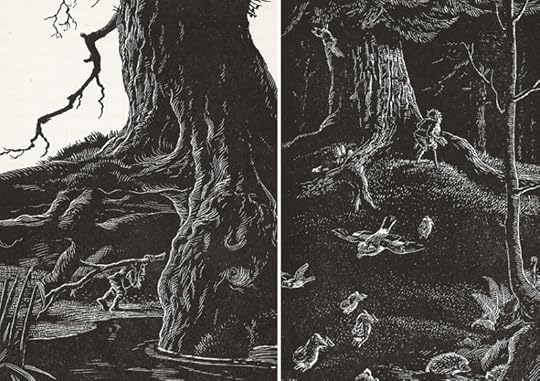

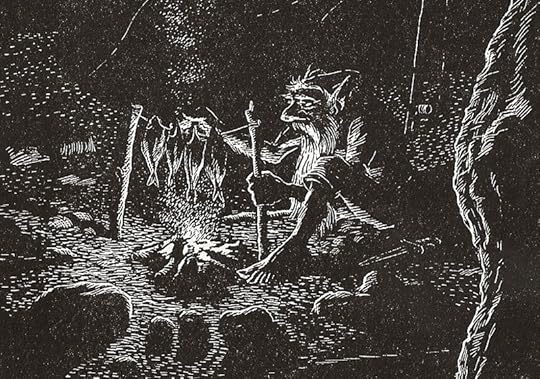

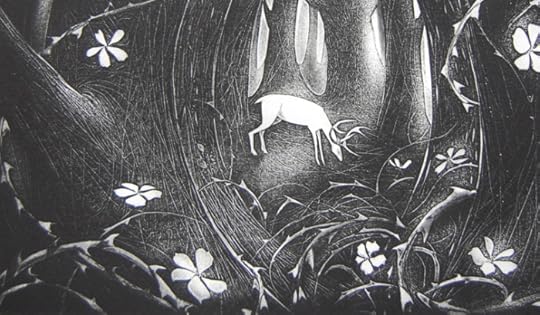

"I was from the first page lost in the world of its principal characters, Dodder, Baldmoney, and Sneezewort (all named after rather uncommon English wild flowers). They were very small people, between a foot and eighteen inches tall, with long flowing beards; Dodder, the oldest, had a wooden leg. But they were different from the sort of gnomes you might expect to come across in the genre of High Fantasy which has so obsessed us in recent years, in Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings and their imitators. They had no magical powers. They were grounded not in fantasy but in realism. Although they were able to converse with the wild creatures around them -- the author's one concession to the idea of gnomic difference -- they lived, and struggled to live, in the world just as we do, concerned about finding enough food and keeping warm. But there was more: they were a dying race. They were last gnomes left in England.

"I remember the shiver I experienced when I first read those words. I think it was an inchoate sense, even in a boy of eight, of the transfixing nature of the end of things. It was clear that they could not survive the creeping urbanisation and modernisation of agriculture which even then was starting to spread across the countryside. They were anachronisms. The world had moved on from them: like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, their time was done. So much the braver, then, their decision to undertake a great adventure, to make an expedition to find their long-lost brother Cloudberry -- ah, Cloudberry! So sad! -- who had never returned after setting out one day to discover the source of the small Warwickshire river, the Folly Brook, on the banks of which they lived, in the capacious roots of an old oak tree.

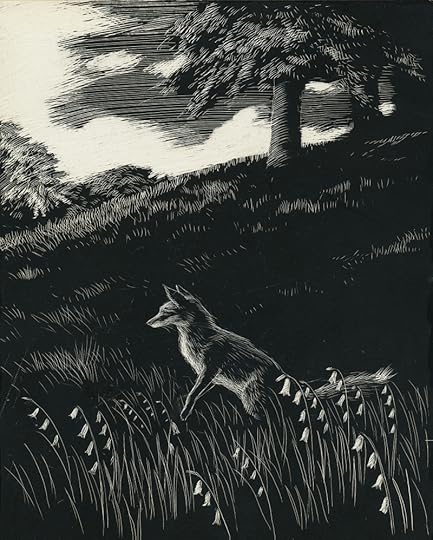

"I was wholly captivated by their quest, and by its unexpected denouement; I was likewise captivated by Down the Bright Stream, the sequel, which I asked for and was given for Christmas the following year. (In the second book, the gnomes' existential crisis reaches its climax; they address it in a most original way, ultimately successful.) But I took in more than the story. I internalised, at first reading, the milieu in which the adventure took place. It was the very opposite of the milieu of The Lord of the Rings, with its dark lords and wizards, its fortresses and mountains, its vast clashing armies; it was merely Warwickshire, leafy Warwickshire, Shakespeare's country, and the Folly Brook, with its kingfishers and otters and minnows, and its kestrels hovering above, a small and intimate and charming countryside with its small and intimate and charming creatures, vivid in their lives and their interactions; and I fell in love with them, and I fell in love with the natural world.

"I went beyond butterflies to the fullness of nature."

I have long believed that stories, particularly fantasy stories, are a powerful way to engage children with nature. Through the wonder at the heart of the tale, we find the wonder at the heart of the world. I didn't know The Little Grey Men when I was a child, but other books had the same effect on me -- from the rural landscapes of Beatrix Potter to the enchanted vistas of Lewis and Tolkien, and, later, of Susan Cooper, Lloyd Alexander, Diana Wynne Jones, Patricia McKillip and Ursula Le Guin, among others. While McCarthy was drawn to the "realism" and intimacy of The Little Grey Men, reflective of the countryside he knew in the England of the 1950s, I grew up in the rapacious urban and suburban development of east coast America in the '60s and '70s, and preferred stories that took me to other worlds -- where landscapes were vast, majestic, unfenced, unpolluted, with nary a car or strip mall in sight. In real life I hustled through time-fractured days mediated by cars and buses, subways and trains; but in fiction, I moved at a walker's pace through Middle Earth, Eldwold, Prydain, Dalemark, Tredana, Islandia and the Earthsea Archipelago; and those long journeys immersed in the natural world were just as vital as the adventures themselves. Can the forests and fields of imaginary lands nurture a connection to, and even a love for, the flora and fauna, the waterways and the ground underfoot that we see everyday? I believe they can. And more than that, in this time of ecological crisis, I believe that they must.

What are stories that made that connection for you, fantasy or otherwise? And were the landscapes as important to you as the characters and the unrolling plot? I'm curious to know your thoughts.

Words: The passages above are from The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy by Michael McCarthy (New York Review of Books edition, 2015), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the author.

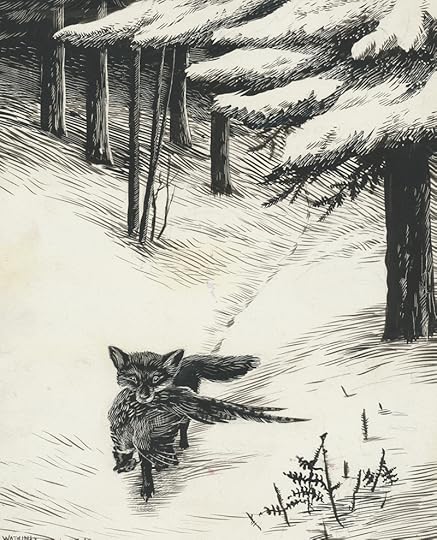

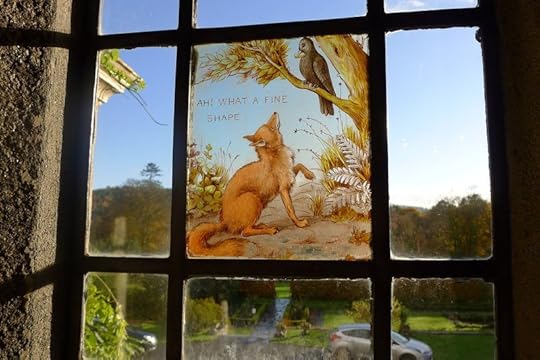

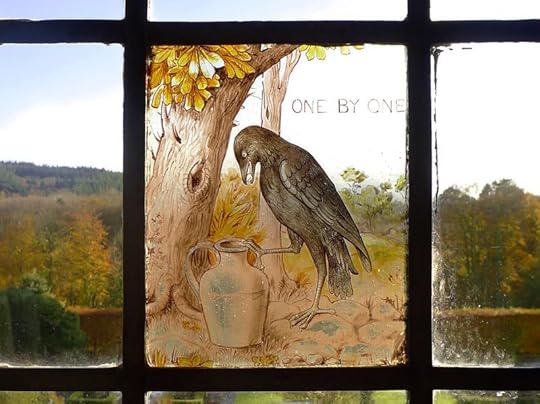

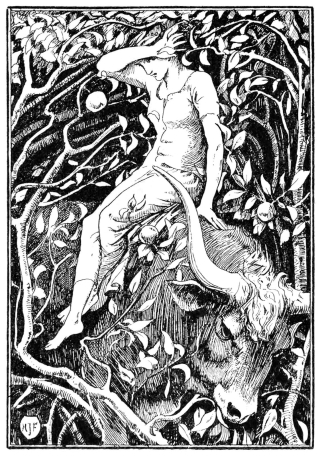

Pictures: The art above is by Denys James Watkins-Pitchford (1905 -1990), a naturalist, teacher, book illustrator, and author of children's fiction under the pseudonym BB. He won the Carnegie Medal for Children's Literature in 1942.

January 20, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I haven't posted a collection of ballads in a while, full of stories murderous and magical -- so here are seven of these timeless songs, all but one of them from the Child Ballads (compiled by the 19th century folklorist and scholar Francis J. Child).

Above: "Down by the Greenwoodside" (Child Ballad #20, also known as "The Cruel Mother"), performed by The Furrow Collective: Lucy Farrell, Rachel Newton, Emily Portman, and Alasdair Roberts. The song is from their new album Fathoms (2019). The animation is by Maud Hewlings.

Below: "Two Sisters" (Child Ballad #10), performed by English singer/songwriter Emily Portman.The song appeared on her solo album The Glamoury (2010).

Above: "The Gardener" (Child Ballad #219), performed by Lady Maisery: Hazel Askew, Hannah James, and Rowan Rheingans. The song appeared on their album Weave & Spin (2011).

Below: "Dowie Dens of Yarrow" (Child Ballad #2019), performed by Scottish singer/songwriter Karine Polwart. The song appeared on Polwart's ballad album Fairest Floo'er (2007).

Above: "Lord Bateman" (Child Ballad #53, also known as "Young Beichan"), performed by English singer/songwriter Chris Wood. The song appeared on his solo album The Lark Descending (2005).

Below: "Bold Lovell" (a variant of the Irish highwayman ballad "Whiskey in the Jar"), performed by English folksinger Jim Moray, with fiddle player Tom Moore. The song is from his new album, The Outlander (2020).

To end with, below: A beautiful and unusual rendition of "Seven Bonnie Gypsies" (Child Ballad #200) performed by Jon Boden & the Remnant Kings. The song from Boden's new album Rose in June (2019). The animation is by Marry Waterson.

The art in this post is by Flora McLachlan, a printmaker based in the west of Wales. "I am inspired by the fairy tales I grew up reading," she says, "and by the motif of the quest in the medieval romance poetry I read during my English degree. I see it as a venturing outwards and also inwards, entering the wild unruly forest of trees and thorns."

All rights to the music and art above reserved by the artists.

January 15, 2020

Myth & Moor update

My apologies for the lack of Myth & Moor posts, everyone. It's been very stormy weather here on Dartmoor, which often plays havoc with our rural internet service. But the weather is easing, connectivity is stabilizing, and I aim to get a new post up asap.

Art by Kay Nielsen (1886-1957).

January 10, 2020

The center called love

In the following passage from Storming the Gates of Paradise, American cultural philosopher Rebecca Solnit says what I've so often wanted to say when conversations here in England turn to the country of my birth:

"I was at a dinner in Amsterdam when the question came up of whether each of us loved his or her country. The German shuddered, the Dutch were equivocal, the Brit said he was 'comfortable' with Britain, the expatriate American said no. And I said yes. Driving now across the arid lands, the red lands, I wondered what it was I loved. The places, the sagebrush basins, the rivers digging themselves deep canyons through arid lands, the incomparable cloud formations of summer monsoons, the way the underside of clouds turns the same blue as the underside of a great blue heron's wings when the storm is about to break.

"Beyond that, for anything you can say about the United States, you can also say the opposite: we're rootless except we're also the Hopi, who haven't moved in several centuries; we're violent except we're also the Franciscans nonviolently resisting nucelar weapons out here; we're consumers except the West is studded with visionary environmentalists...and the landscape of the West seems like the stage on which such dramas are played out, a space without boundaries, in which anything can be realized, a moral ground, out here where your shadow can stretch hundreds of feet just before sunset, where you loom large, and lonely.���

That's it exactly. It's why I still love America, even though Dartmoor has claimed my heart. I've never been more aware of how fundamentally North American I am than now, living an ocean away. It is my home. And Dartmoor is home. And the very word home is fraught with contradictions.

"All of us," wrote the late English naturalist Roger Deakin, "carry about in our heads places and landscapes we shall never forget because we have experienced such intensity of life there: places where, like the child that 'feels its life in every limb' in Wordsworth's poem 'We are seven,' our eyes have opened wider, and all our senses have somehow heightened. By way of returning the compliment, we accord these places that have given us such joy a special place in our memories and imaginations. They live on in us, wherever we may be, however far from them."

I feel the truth of this deep in my bones. I am rooted here on Dartmoor now: in a village nestled between two hills; in a tumbledown house on one hill's slope; in a tapestry of oak and stream, wild ponies and grazing sheep. But other landscapes haunt my dreams. They haunt my waking hours too, sometimes so real that I can almost smell the smoke of an Arizona desert campfire, the tang of cafe con leche in New York City, or the salt sea air of the Boston docks. Past and present blend together, and at the midnight hour, I hear coyotes howl in the Devon hills.

"The desire to go home," says Rebecca Solnit, "[is] a desire to be whole, to know where you are, to be the point of intersection of all the lines drawn through all the stars, to be the constellation-maker and the center of the world, that center called love. To awaken from sleep, to rest from awakening, to tame the animal, to let the soul go wild, to shelter in darkness and blaze with light, to cease to speak and be perfectly understood."

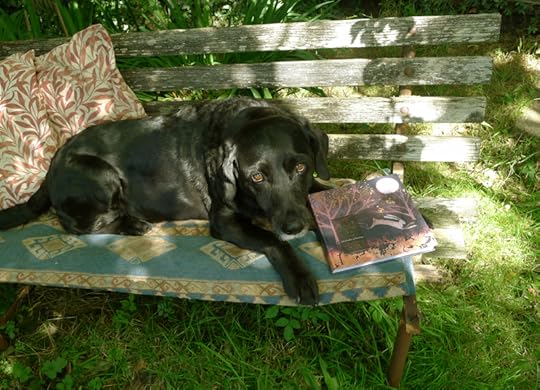

But where exactly is home? It is there and then. It is here and now. It is lost in the precious or painful past, and it is somewhere in the future we're walking toward. It is in the words I'm writing and the images I'm painting. It's in solitude, and in family life. It's a feeling as elusive as memory and as solid as this hound beside me. It's in the closing of the book, the rising from the moss, the whistle for Tilly: Come girl, let's go. It is waiting for us at the end of the path. At the kitchen door. At the resolution of the story. It is this: the hill. The wind. The center of the world, that center called love.

Words: The passages about are from Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics by Rebecca Solnit (University of California Press, 2007) and Notes from Walnut Tree Farm by Roger Deakin (Hamish Hamilton, 2008). The poem in the picture captions is from Wake Up in Brightness (Seattle Arts & Lectures, 2009). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Winter coffee break beneath a favourite oak in a nearby field.

January 9, 2020

Rooms of Our Own

In Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasure of a Creative Life, novelist and memoirist Dani Shapiro discusses the importance of having (as Virginia Woolf instructed so wisely) a "room of one's own" for nurturing our best creative work:

"It doesn't matter what or where it is, as long as it is yours. I don't necessarily mean that it has to belong to you. Only that, for the time you're working, you have what you need. Learning what you need to do your best work is a big step forward in the life of any writer. We all have different requirements, different ways of working. I have a friend who likes to write on the subway. She will board the F-train just to get work done. The jostle and cacophany -- she finds it clears her mind. Me? You'd have to shoot me first. For one, I'm a wee bit claustrophobic. Also, I need solitude and silence. I have friends who work best in coffee shops, others who like to work in the same rooms as their partners. Friends who have written multiple books at their kitchen tables. Marcel Proust famously wrote in bed, and so did Wendy Wasserstein. Gay Talese, the son of an Italian tailor, dresses in custom-made suits each morning and descends the stairs to his basement study. Hemingway wrote standing up. One writer I know works best late at night, a habit left over from the years when she had young children under her roof and those were the only hours that were hers alone....

"We writers spend our days making something out of nothing. There is the blank page (or screen) and then there is the fraught and magical process of putting words down on the page. There is no shape, no blueprint, until one emerges from the page, as if through a mist. Is it a mirage? Is it real? We can't know. And so we need a sense of structure around us. These four walls. This cup. The wheels of the train beneath us. This borrowed room. The weight of this particular pen. Whatever it is that makes us feel secure in our physical space allows us to make the leap, hoping that the page will catch us. Writing, after all, is an act of faith. We must believe, without the slightest evidence that believing will get us anywhere."

I agree with Shapiro that it's important to discover how, and where, we do our best work -- for with this knowledge we can align our habits with our creative temperament instead of handicapping ourselves by working against our natural rhythms. But these rhythms, I find, also change through time; what has worked during an earlier phase of life might be entirely unhelpful to us today. Over the course of my life, I have been all of the writers Shapiro describes above (except that unimaginable subway scribbler): I was a big-city cafe writer in my twenties; I shared an office with a fellow writer throughout my thirties; I've worked in communal Art Studio buildings in New York, Boston, Tucson and Devon over the years...and yet today I find myself wedded to the silence and solitude of a small cabin by the woods.

And then, of course, when we think we've finally got it sussed -- our work place set, our habits established, our schedule steady, productive, and predictable -- life throws a curveball at us, things change, we change, and we start all over again. We have to hone our working methods not once but several times over, as our art and our lives unfold.

What what about you? Where do you do your best work? Do you have a "room of your own"...are you searching for one...or are you one of those people who can plunk down and work from anywhere? What's your ideal space; has it changed over the years? What was the best space that you've worked in, or the worst, and how much does your physical environment matter?

Do you ever retreat from the world to write or paint? What would the retreat space of your dreams be like? The room pictured here, in a 16th century Devon manor house, is one of mine....

Pictures: The photographs above are of Lewtrenchard, a Jacobean manor house in Lewdown, Devon -- home to the Victorian author and folklorist Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould, and the setting of Laurie R. King's novel The Moor, in her "Mary Russell" series. You can read more about Lewtrenchard (and the story of how Howard and I came to be there) in the picture captions, which you'll find by running your cursor over each photograph.

Words: The passages quoted about are from Still Writing by Dani Shapiro (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013), which I highly recommend -- as well as the author's blog about her writing life, Moments of Being. All rights reserved by the author.

A related post: What makes a good writing day?, full of pictures of writing rooms, cabins, and huts.

January 8, 2020

The Folklore of Hearth & Home

I've been corresponding with my friend Steve Toase on the subject of "home and homelessness" in life and literature, which made me go back to this article I wrote some years ago (prior to getting married and moving to Bumblehill, our current house, with Howard and our daughter). Since stories of "home and homelessness" are on my mind, I thought I'd share this article with you....

In the autumn of 2007, I packed up and sold the house where I'd lived for many years: a 16th century, thatch���roof cottage in a small English village on Dartmoor. The cottage was hugely significant to me, for I'd lived there much of my adult life, but in the house's own story, spanning four centuries, my two decades were a drop in the bucket. The cottage felt strange on my last evening there, emptied of furniture and books; only the goblin murals on the kitchen walls remained of the life I'd known there. I lit a last fire in the ancient stone hearth���and when the flames had burned down low, I put hot coals into an old tin can, following a Dartmoor folk custom. The coals would be used to light a fire at my next abode, just down the street -- which would bring me luck, according to some legends, and allow any fairies that lived in the hearth to move along with me, according to others. I left the cottage, locked the door, and pushed the house keys through the door's mail slot. They hit the floor, and with that sound, a large part of my life was now over.

I'd been anticipating this move for over a year, and was making the change for positive reasons, so the depth of the loss I felt in that moment was entirely unexpected. It wasn't just the cottage I was leaving behind, but the person I'd been there for so many years...and the future I'd always imagined I'd have growing old under its roof. Living in a magical, ancient house had become part of my self-identity. Who was I now, without that familiar backdrop of grinning goblins and old oak beams, of Morris fabrics and medieval tapestries? What remained of me, with the world that I'd woven around me stripped away? For the better part of two decades, my concept of "home" had been solid, unchangeable, literally built of granite; but life had taken an unexpected turn. I didn't yet know where this was leading. For now, I'd be in temporary digs, my worldly belongings packed in storage, my work/living needs pared down to essentials. Without the weight of that old stone house, my life felt curiously unmoored...but also full of narrative possibility as I waited for its next chapter to begin.

Weaver's Cottage, built in 1596, in a small village at the edge of Darmoor

In this time of upheaval, I began to think about the hold that our homes can have on us, even in a transient culture where multiple moves are not unusual. The places we live and the places we grew up in have an impact, whether acknowledged or not, on our lives, our relationships, our dreams; and the houses we yearn for, whether real or imagined, reveal much about our inner nature. As a folklorist, I'm interested in how the idea of home is expressed in traditional stories; and as a fantasist, in how this translates into modern magical fiction.

Fairy tales, for example often begin with a hero propelled from his or her home by poverty or calamity; and the search for the safe haven of a new home, or the task of restoring prosperity to an old one, is central to such stories. Fairy tales tend to be rites-of-passage narratives, chronicling a transformational journey from one archetypal life stage to another. Most often, such tales follow a young hero's transition from childhood to adulthood, the completion of the journey symbolized by a wedding at the story's end. In the modern, simplified versions of the tales popularized by Disney films and children's books, the emphasis is so often placed on the romantic (and wealth accumulating) aspects of the stories that finding "true love" (with a well heeled spouse) can seem to be what fairy tales are all about. Older, adult versions of the tales, by contrast, are focused on the steps of the hero's passage through a period of upheaval and peril -- a period required to test the hero's mettle and provoke growth and self-transformation. Such tales speak to the challenges we face at any time in life (not just in our youth) when circumstances force us to leave home, either literally or metaphorically, setting us on the road to an unknown future and a new identity.

Fairy tales, for example often begin with a hero propelled from his or her home by poverty or calamity; and the search for the safe haven of a new home, or the task of restoring prosperity to an old one, is central to such stories. Fairy tales tend to be rites-of-passage narratives, chronicling a transformational journey from one archetypal life stage to another. Most often, such tales follow a young hero's transition from childhood to adulthood, the completion of the journey symbolized by a wedding at the story's end. In the modern, simplified versions of the tales popularized by Disney films and children's books, the emphasis is so often placed on the romantic (and wealth accumulating) aspects of the stories that finding "true love" (with a well heeled spouse) can seem to be what fairy tales are all about. Older, adult versions of the tales, by contrast, are focused on the steps of the hero's passage through a period of upheaval and peril -- a period required to test the hero's mettle and provoke growth and self-transformation. Such tales speak to the challenges we face at any time in life (not just in our youth) when circumstances force us to leave home, either literally or metaphorically, setting us on the road to an unknown future and a new identity.

Snow White, Donkeyskin, The Girl With No Hands, Hans My Hedgehog: these are all rites-of-passage narratives. Each tale begins in a childhood home that has become constricting, even dangerous, and each hero must leave this home behind in order to forge a new life in the adult world. The completion of the hero's task is marked by the traditional rewards of the fairy tale genre: a marriage, a crown, a storehold full of treasure; but the true reward at journey's end is a new-found ability to survive life's trials, transcend its terrors, and determine one's own fate.

Snow White, Donkeyskin, The Girl With No Hands, Hans My Hedgehog: these are all rites-of-passage narratives. Each tale begins in a childhood home that has become constricting, even dangerous, and each hero must leave this home behind in order to forge a new life in the adult world. The completion of the hero's task is marked by the traditional rewards of the fairy tale genre: a marriage, a crown, a storehold full of treasure; but the true reward at journey's end is a new-found ability to survive life's trials, transcend its terrors, and determine one's own fate.

The heroes begin in one home and end in another (or else in the old home restored and renewed), but in between these two poles is a crucial period of homelessness. Homelessness is a liminal state rich in opportunities for character change and growth, which has made it a popular plot device among storytellers both old and new. Homelessness detaches protagonists from the roles they have played in the past, strips them of identity, blurs the markers of class or rank, removes usual sources of aid and comfort, and throws them on their own resources. . .a perfect recipe for suspense, adventure, and heroic metamorphosis.

The archetypal Hero's Journey is often a different one for the young men and women in traditional stories, as Midori Snyder discussed in her fine article on the Armless Maiden folk tale: "In hero narratives," she wrote, "a young man leaves the familiar home of his birth and ventures into the unknown world where the fantastic waits to challenge him. Along the journey, his worth as a man and as a hero is tested. But when the trials are done, he returns home again in triumph, bringing to his society new-found knowledge, maturity and often a magical bride." A young woman, by contrast, ventures out or is propelled into the world "knowing that she will never return home. Instead, at the end of a perilous and solitary journey, she arrives at a new village or kingdom. There, disguised as a dirty-faced servant, a scullery maid, or a goose girl, she completes her initiation into adulthood and brings the gifts of knowledge, maturity, and fertility to a new home and community."

Such stories rose from societies in which this gender difference was a fact of life; where girls were expected to leave home upon marriage and join the household, village, or tribe of their new husband's family. (We see the echo of this tradition today when women give up their own names upon marriage.) The anxiety felt by women in such cultures, particularly in places where they were allowed no say in the choice of husband, was expressed by tales such as Bluebeard/Fitcher's Bird, or Beauty and the Beast, in which a young woman finds herself far from home, co-habiting with a monster.

Goblins in my Goblin Kitchen, painted by Brian Froud, inspired by Christina Rossetti's classic fairy poem "Goblin Market"

Another staple of folk and fairy tales is the mysterious house that appears to offer shelter but is actually a source of danger or enchantment. The gingerbread house in Hansel and Gretel is a welcome sight to the two hungry children made homeless by their feckless parents, but it's really just a trap designed to lure boys and girls into a cooking pot. There are numerous tales in which weary travelers stumble upon a house in the woods with its front door standing invitingly open, a fire lit, a hot meal spread temptingly on the table, and the owner of the house nowhere in sight. Lisel Mueller wrote about just such a house in her magical poem "Voices from the Forest. "No matter how exhausted you are, Mueller says, do not enter the house in the forest:

It is only when you finish eating

and, drowsy and grateful, pull off your shoes,

that the ax falls or the giant returns

or the monster springs or the witch

locks the door from the outside and throws away the key.

But if you must enter, Neil Gaiman has advice in his charming poem "Instructions":

A red metal imp hangs from the green���painted front door, as a knocker,

do not touch it; it will bite your fingers.

Walk through the house. Take nothing. Eat nothing.

Those last words are important. Folk tales from all over the world warn that eating the food of a witch, a demon, a djinn, a troll, an ogre, or the fairies can be a dangerous proposition. You might owe your youngest child in return, or be bound to your host for the rest of your life. Likewise, don't kiss the beautiful woman who offers you a meal and a bed in her sumptuous chateau hidden deep in the woods. By morning light she'll be a monster, and her house but a pile of rocks and bones. Some enchanted houses appear for a single night each year and then vanish again. Be sure to be out by dawn or you too will disappear along with it. And sometimes the houses themselves are monstrous, such as the famous hut of the witch Baba Yaga in Russian fairy tales, which balances on chicken legs and can spin and move from place to place.

Goblins by Alan Lee, Dennis Nolan, and Charles Vess

There are also houses in the woods, however, where the safe haven offered is not mere illusion, often put on the hero's path by a kindly fairy or a guardian angel. The hero of The Girl With No Hands finds just such a sanctuary deep in the forest, and the princess in The White Deer lives in one at night, when she's in human form. Jungian psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz considered these woodland dwellings to represent the place deep within ourselves where we retreat, in solitude, to ponder life's deeper meanings, heal our wounds, and renew our spirits. In tales like The Girl With No Hands, she said, the hero enters the woods (the psyche) in a maimed or enchanted state, and does not leave again until she is healed, whole, transformed.

In both Jungian psychology and dream analysis, a house is much more that just a dwelling or shelter -- it is a symbol in the ancient, pictorial language of mythic archetypes. Dream analysts say that a house represents the levels of the dreamer's own mind, and some give each different part of the house a specific significance: The front porch is our social or public mask; the living room, our interior consciousness; the kitchen represents our potential ��� the place where ideas are stirred, cooked up, and brought into conscious form. Cabinets and drawers hold experiences; closets hold hidden aspects and talents; stairs represent growth and moving up to (or down from) higher levels of consciousness. A bedroom dream reveals the things that the subconscious mind is pre���occupied with; a hallway leads to memories and the past, or to possibilities and the future. Rearranging the furniture indicates a sorting of priorities, ideals, or beliefs. A house demolition is a major life change, or the deterioration of physical health, and moving represents a change of consciousness or a psychic upheaval.

In both Jungian psychology and dream analysis, a house is much more that just a dwelling or shelter -- it is a symbol in the ancient, pictorial language of mythic archetypes. Dream analysts say that a house represents the levels of the dreamer's own mind, and some give each different part of the house a specific significance: The front porch is our social or public mask; the living room, our interior consciousness; the kitchen represents our potential ��� the place where ideas are stirred, cooked up, and brought into conscious form. Cabinets and drawers hold experiences; closets hold hidden aspects and talents; stairs represent growth and moving up to (or down from) higher levels of consciousness. A bedroom dream reveals the things that the subconscious mind is pre���occupied with; a hallway leads to memories and the past, or to possibilities and the future. Rearranging the furniture indicates a sorting of priorities, ideals, or beliefs. A house demolition is a major life change, or the deterioration of physical health, and moving represents a change of consciousness or a psychic upheaval.

Carl Jung himself had recurring dreams in which houses featured prominently. He often dreamed he was building a house, or had stumbled upon a new room in his home -- representing, he said, the building of the self and the discovery of new ideas. In his forties, Jung bought a parcel of land and turned dream into reality by building Bollingen, his spiritual retreat on the banks of Lake Zurich. He started off with a low stone tower, built largely with his own two hands, its round shape representing the maternal archetype (and his own mother's recent death). Slowly, over thirty years, the house sprouted another tower, a courtyard, an annex, and a second floor, each addition marking a life change and the evolution of his theories of the psyche. Bollingen was Jung's attempt to achieve a "representation in stone of my innermost thoughts and the knowledge I had acquired....From the very beginning, I felt the Tower as in some way a place of maturation -- a maternal womb or maternal figure in which I would become what I was, what I am, and will be."

Jung's vision of a house, built in the round, as the embodiment of the "eternal feminine" had its roots in the mythology and building practices of ancient Greece, where the home was sacred to Hestia, goddess of the hearth and perpetual flame. Sometimes called "the forgotten goddess," Hestia rarely appears in the tales of the gods, and seems to have had few temples or acolytes; and yet she was actually the first of the goddesses, sitting higher in the Olympian pantheon than even Hera (wife of Zeus, goddess of love and marriage) or Demeter (goddess of fertility and the harvest). Although avidly courted by both Poseidon and Apollo, Hestia vowed she would never marry, dedicating herself instead to the management of Mount Olympus, home of the gods. For this, she received the first portion of tribute in the temple rites of all the other gods, and was worshipped at the hearth in the center of all houses and buildings. Each morning began with Hestian prayers as the family fire was stoked for cooking and heating; each day ended with prayers to the goddess as the fire was banked for the night. Unlike the rest of the Greek pantheon, well known for their tempers, jealousies, and quarrels, Hestia was an unusually stable goddess, revered for her gentle, calm, and forgiving nature. But lest we think of her as the Olympian equivalent of a 1950s housewife, limited to home and the service of others, she was also the first builder, the inventor of architecture, and the patron of these arts. Her symbols were the circle and perpetual flame (including the undying flame of the Olympics), and her sphere of influence reached beyond the home to the undying flame at the heart of the Senate.

Jung's vision of a house, built in the round, as the embodiment of the "eternal feminine" had its roots in the mythology and building practices of ancient Greece, where the home was sacred to Hestia, goddess of the hearth and perpetual flame. Sometimes called "the forgotten goddess," Hestia rarely appears in the tales of the gods, and seems to have had few temples or acolytes; and yet she was actually the first of the goddesses, sitting higher in the Olympian pantheon than even Hera (wife of Zeus, goddess of love and marriage) or Demeter (goddess of fertility and the harvest). Although avidly courted by both Poseidon and Apollo, Hestia vowed she would never marry, dedicating herself instead to the management of Mount Olympus, home of the gods. For this, she received the first portion of tribute in the temple rites of all the other gods, and was worshipped at the hearth in the center of all houses and buildings. Each morning began with Hestian prayers as the family fire was stoked for cooking and heating; each day ended with prayers to the goddess as the fire was banked for the night. Unlike the rest of the Greek pantheon, well known for their tempers, jealousies, and quarrels, Hestia was an unusually stable goddess, revered for her gentle, calm, and forgiving nature. But lest we think of her as the Olympian equivalent of a 1950s housewife, limited to home and the service of others, she was also the first builder, the inventor of architecture, and the patron of these arts. Her symbols were the circle and perpetual flame (including the undying flame of the Olympics), and her sphere of influence reached beyond the home to the undying flame at the heart of the Senate.

Her counterpart in Roman myth was Vesta, although the two are not completely interchangeable. Vesta, too, was venerated at the hearth and thus played a central role in family life -- but she also had public temples, including her famous circular temple in Rome where priestesses tended the perpetual flame that was the city's source of spiritual strength. Called Vestal Virgins (having pledged themselves to thirty years of celibacy), Vesta's priestesses enjoyed an unusual degree of freedom and political power in a society that was not known for enlightened attitudes towards women. At the end of thirty years, the Vestal Virgins were free to end their vows and marry, but few cared to trade the privileges of their profession for the restricted life of the average Roman matron. In addition to a central shrine to Vesta, most Roman families maintained shrines for a panoply of small domestic gods: the Lares, protectors of the household, and the Penates, gods of pantry and larder.

Her counterpart in Roman myth was Vesta, although the two are not completely interchangeable. Vesta, too, was venerated at the hearth and thus played a central role in family life -- but she also had public temples, including her famous circular temple in Rome where priestesses tended the perpetual flame that was the city's source of spiritual strength. Called Vestal Virgins (having pledged themselves to thirty years of celibacy), Vesta's priestesses enjoyed an unusual degree of freedom and political power in a society that was not known for enlightened attitudes towards women. At the end of thirty years, the Vestal Virgins were free to end their vows and marry, but few cared to trade the privileges of their profession for the restricted life of the average Roman matron. In addition to a central shrine to Vesta, most Roman families maintained shrines for a panoply of small domestic gods: the Lares, protectors of the household, and the Penates, gods of pantry and larder.

A shadow forest pai nted on bedroom walls

Shrines to the Lares and Penates of the house were located conveniently close to the door so that offerings could be made frequently -- for, like the fairies of English lore, they were troublesome if neglected. The door itself was watched over by Janus, the two-faced god of doors and gates, associated with endings and beginnings, joined in his duties by Cardea, the goddess of door handles and hinges. Ovid tells us that Cardea's power is "to open what is shut, and to shut what is open." As a result, she was also the goddess of midwives, called upon during difficult childbirths. The threshold, and the act of crossing over it, belonged to the trickster god Mercury (Hermes in Greek), whose sign, a phallic-shaped stone or statue, often stood guard at the front of the dwelling. It was customary to stroke the stone for luck when leaving or returning home.

While Greco-Roman myth divided the roles of the goddess of the home and the goddess of marriage (Hestia/Vesta on one hand, Hera/Juno on the other), Norse mythology combined them into a single powerful figure, the goddess Frigg. The wife of Odin and the queen of the Aesir, Frigg's province covered hearth, home, love, marriage, and child-bearing (among many other things), all of which were accorded high status. Only she, among all the gods, was permitted to share Odin's high seat and look out over the universe. In Celtic myth, Brigidh was the goddess of the hearth and the keeper of the sacred flame, although, like Frigg, her influence extended much beyond the domestic sphere; she was also the goddess of poetic eloquence and of skill in the planning of warfare. Brigidh's legends overlapped with those of Habondia, an Anglo-Saxon goddess of hearth and home. Household shrines to Brigidh or Habondia insured the fertility of the marriage bed, tranquility among family members, and the blessing of domestic chores -- especially the "magical arts" of cooking, bread baking, and brewing.

In Western mythic traditions, the home was the realm of female deities, but when we look at the lesser supernaturals -- the Lares, the Penates, the various tribes of fairies -- we find a range of male figures attached or attracted to human dwellings: hobgoblins, house brownies, hearth fairies,

chimney trolls, and other similar creatures. These could be helpful and protective spirits if treated respectfully and generously (according to the creature's particular code), or they could make a house unlivable: spoiling the bread, curdling the milk, dampening the fire. We must go to other parts of the world to find traditions favoring male household gods, though even these tend to be among the minor deities.

In China, for example, Tsao Wang is a popular hearth god in the countryside, where he watches over each household from his shrine by the hearth or stove. Great care must be taken not to swear, quarrel, or lie within the hearth god's hearing, for each year Tsao Wang makes an annual report to the celestial Jade Emperor, and this determines the family's luck (or lack thereof) in the year ahead. Vietnam has a similar deity called the Stove God, or Mandarin Tao -- a clownish figure who's in such a rush to get to Heaven with his annual report that he often leaves his trousers behind and is commonly pictured without them. Oki-Tsu-Hiko-No-Kami and his consort, Oki-Tsu-Hime-No-Kami, are the kitchen gods of Japanese lore. As the children of harvest deities, their province is food storage and preparation; neglect of their shrine will cause the rice pot to boil over or the vegetables to rot. In Hindu myth, Annamurti, one of many forms of the god Vishnu, is the deity to call upon in the kitchen, where cooks make offerings of sweetened rice and milk to gain his favor. Hinukan, the hearth and kitchen god of the Uchinanchu people of Okinawa, is always paired in the household pantheon with Fuuru nu Kami, the god of the toilet. Without the latter figure, negative spirits attracted to waste matter would cause illness or worse. In Russian folklore, hearth spirits (usually male) followed their particular families from house to house. In customs similar to those here on Dartmoor, the first fire in a new fireplace was lit with coals or embers from the old, with all the doors standing open wide as the spirit was formally invited in.

In China, for example, Tsao Wang is a popular hearth god in the countryside, where he watches over each household from his shrine by the hearth or stove. Great care must be taken not to swear, quarrel, or lie within the hearth god's hearing, for each year Tsao Wang makes an annual report to the celestial Jade Emperor, and this determines the family's luck (or lack thereof) in the year ahead. Vietnam has a similar deity called the Stove God, or Mandarin Tao -- a clownish figure who's in such a rush to get to Heaven with his annual report that he often leaves his trousers behind and is commonly pictured without them. Oki-Tsu-Hiko-No-Kami and his consort, Oki-Tsu-Hime-No-Kami, are the kitchen gods of Japanese lore. As the children of harvest deities, their province is food storage and preparation; neglect of their shrine will cause the rice pot to boil over or the vegetables to rot. In Hindu myth, Annamurti, one of many forms of the god Vishnu, is the deity to call upon in the kitchen, where cooks make offerings of sweetened rice and milk to gain his favor. Hinukan, the hearth and kitchen god of the Uchinanchu people of Okinawa, is always paired in the household pantheon with Fuuru nu Kami, the god of the toilet. Without the latter figure, negative spirits attracted to waste matter would cause illness or worse. In Russian folklore, hearth spirits (usually male) followed their particular families from house to house. In customs similar to those here on Dartmoor, the first fire in a new fireplace was lit with coals or embers from the old, with all the doors standing open wide as the spirit was formally invited in.

It has been many, many years, however, since an open fire was the indispensable center of the home, at least in Western culture, and even the kitchen is losing its importance as rushed family members eat on the run. Where, then, is the heart of the modern home? The television, or computer screen? And what gods might be taking residence there, expecting tribute and propitiation? It is not only modern technology and an increasingly secular culture that have changed our relationship with our homes, however. For the first time in our history more of us live in cities than in rural communities; and few of us in the West still live on the land where our ancestors have lived. Home is where we hang our hat, as the old song says, rather than a landscape grazed or farmed for generation after generation. Home means the place we live right now; tomorrow it may mean someplace different. We are now, most of us, like the female heroes in traditional stories who leave their home with no expectation of returning���and we do this not once in our lives, but sometimes again and again and again.

Folk tales remind us, however, that moving home is not a simple act; it's one with mythic reverberations. It's a rite-of-passage, with all the attendant dangers and potential rewards that such passages offer. Houses are more than just real estate; they represent our innermost selves (as the Jungian say) and the stages of our lives (as the fairy tales tell us). In both views, moving from one home to another means passing through a period of upheaval, provoking internal change and self-transformation. And we're advised to carry the coals of our old life with us to kindle the new life ahead.

In fantasy literature, as in fairy tales, many stories begin with the loss of a home, and this is precisely what thrusts the protagonists into the world. Some stories, like L. Frank Baum's The Wizard of Oz or J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, rest on the main protagonist's fierce desire to go home again; in others, they must find or create new homes for themselves in far distant lands. In Diana Wynne Jones' Charmed Life, for example, young Janet chooses to remain in the magical world of Chrestomanci; in Pamela Dean's "Secret Country" books, some of the children never return home again; and Austin Tappan Wright's great utopian novel Islandia revolves around a hero pulled between loyalties to his old and new countries. In fiction, as in myth, it's that in-between period of wandering and homelessness that allows for adventure and metamorphosis, propelling characters out of their settled ways of life and into their new roles as heroes.

Bilbo & Frodo Baggin's house, Bag End, drawn by Alan Lee

In children's fantasy, many adventures begin when a child's usual home is disrupted -- when they're sent off to live with relatives, or transplanted to a summer cottage, or sent off to boarding school, etc. It's interesting to note that a number of these tales -- The Owl Service by Alan Garner, for example, or The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken -- were penned by writers who grew up in England during the Second World War, a time when children were regularly sent away from home to escape German bombers. Displacement, once again, creates a space that is rich in narrative possibilities, with the added bonus that once the parents are off the scene, the young protagonists are thrown onto their own resources.

What I love best are those fantasy novels where the houses themselves are a source of enchantment, reminiscent of the fairy towers and haunted chateaux to be found in folk tales. The masterwork in this mini-genre is The Gormenghast Trilogy by Mervyn Peake, in which an entire epic world is created beneath one rambling, crumbling roof, but there are plenty of other fantastical houses I'd also love to have a good wander in: such as Edgewood from John Crowley's Little, Big, or Tamsin House from Charles de Lint's Moonheart; or Crackpot Hall from Ysabeau Wilce's Flora Segunda; or Moonacre Manor from Elizabeth Goudge's The Little White Horse. In such books, domestic spaces regain their aura of the numinous, connecting us, in our everyday lives, as we sleep and wake and cook and clean, to the realm of the gods, the fairies, the ancestors, and to worlds of magic.

Gormenghast painted by Alan Lee

In real life, too, there are those who turn their houses into enchanted spaces -- particularly among artists, some of whom seem compelled to transform the whole world around them. The Pre-Raphaelite visionary William Morris was famous for his desire to bring beauty into every small facet of daily life, designing his own furniture, fabrics, and wallpaper patterns; making his own dyes, weaving his own rugs, painting his own chimney tiles, and so forth. A revolution in British design was born from the fanciful homes he created for his family and his friends at Red House in south-east London and Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire.

Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire

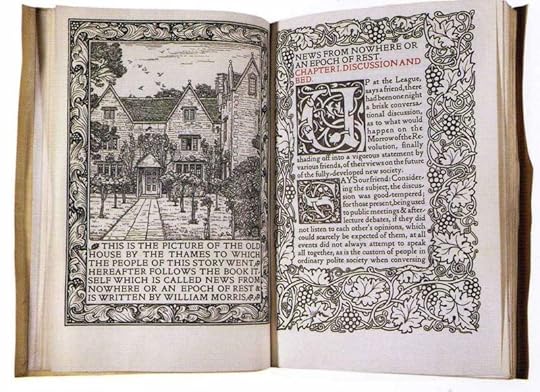

A drawing of Kelmscott Manor in News from Nowhere by William Morris

The Willow Bedroom at Kelmscott Manor, will wallpaper & textiles designed by William Morris

The Willow Guest-Bedroom at Weaver's Cottage, in honor of Morris

The Bloomsbury artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant took their paintbrushes to every surface of Charleston, the farmhouse they shared with other writers and artists in the Sussex countryside. Preserved and open to the public now, Charleston is a timeless, spell-bound world formed of pattern, color, and whimsy.

Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex

The living room at Charleston

Duncan Grant's studio at Charleston

In Moscow, Viktor Vasnetsov's magical home has been turned into a house-museum, featuring the mythic paintings for which this 19th century artist is famed. The house is a fantasy vision, designed in the distinctive "Russian folk tale style" that Vasnetsov created and promoted as part of the Russian Revivalist movement. In Sweden, Carl & Karin Larsson turned their Sundborn farmhouse into a work of art -- made famous by Carl's many paintings of the house, and of their family life within it. On the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, Walter Inglis Anderson spent his last decades in a secluded, rustic cottage where (unbeknownst to family and friends) he covered the walls of a padlocked room with luminous murals of astonishing beauty, born of a spiritual vision rooted in his passion for nature. The "Little Room" was discovered after the artist's death, and can now be viewed at the Walter Anderson Museum.

The Viktor Vasnetsov House-Museum in Moscow

Carl & Karin Larsson's farmhouse in Sundborn, Sweden

A corner of the room painted by Walter Inglis Anderson on the coast of Mississippi

By the end of my time at Weaver's Cottage, the walls throughout the place were covered with poems, quotes, drawings and paintings of trees, deer, and fairy tale creatures -- added slowly, year by year, as my life and work in the house evolved. There was a forest in the bedroom, deer women on the stairs, bunny girls peeping from hidden corners -- but the Goblin Kitchen is what people remember best, and for good reason. Inspired by Christina Rossetti's classic fairy poem "Goblin Market," the fruit-juggling rascals on the kitchen walls were painted by several artist friends: Brian Froud, Alan Lee, Charles Vess, Dennis Nolan, and Lauren Mills among them. Now they, too, have slipped into the house's long story, haunting the place like all its other ghosts.

Brian Froud & Alan Lee painting goblins in the kitchen of my cottage, 1991, and Brian's goblins grinning from the wall

As I walked away from Weaver's Cottage, I couldn't help thinking of fairy tales: of endings, and of beginnings, and of how the one loops into the other. I didn't yet know what roads lay ahead, or who I would be on the next stage of the journey. I couldn't imagine the trials I'd face, or the treasures I'd find at journey's end. Would my life become ordinary and dull without that old house, with its ghosts and goblins?

Nah. As the folk tales tell us, it's when you leave home that the magic begins.

The photographs of Weaver's Cottage above were taken by Alan Lee, Stephen Dooley, Helen Mason, and me. (Please do not re-post these images, as this was my home.) The murals, sadly, no longer exist; a subsequent owner of the cottage painted them over. Perhaps, like faery gold, they were meant to be ephemeral....

The other houses pictured here are open to the public. The photographs of them are from the public websites for Kelmscott Manor, Charleston Farmhouse, The Viktor Vasnetsov House-Museum, The Carl & Karin Larsson Farmhouse, and The Walter Anderson Museum; all rights reserved by the owners of these estates. The pen-&-ink drawings are "Oliver Twist" by E.M.Taylor and "Woods Thicker and Thicker" by H.J. Ford. The silhouette drawing is "Hansel & Gretel" by Laura Berrett. The pencil drawing of Bag End and the painting of Gormenghast are by Alan Lee. All rights to the text, photographs, and art in this post reserved by the author, photographers, and artists.

January 7, 2020

Coming up this month....

This event kicks off the new "Book Talk & Tea" series, sponsored by The Friends of Chagford Library and curated by Susan Harley. These monthly events will feature Sunday afternoon talks by a range of fine authors and book artists. There will be tea, cakes, books to browse and buy...so please if you're anywhere near Devon please come join us in support of books, community, the power of stories, and the importance of rural libraries.

In this talk, I'll discuss the importance of adapting ancient tales for modern times, and how such stories can help us navigate the many challenges we face today. While ecologists speak of "re-wilding" the land, I believe in also "re-storying" the land, reclaiming the tales that connect us to natural world and re-shaping them for a modern age.

When: Sunday, 26 January, at 3 pm

Where: Jubilee Hall, Chagford

Tickets ��5, available from Sally's Newsagents in Chagford Square, or online here.

The beautiful art above is by Jeanie Tomanek.

January 6, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

On a winter's morning at the edge of the moor, when the world outside seems so discordant, I turn to music, nature, and stories to keep going. Here's what I'm listening to right now...

Above: "Hwome" by Ninebarrow (Jon Whitley & Jay LaBouchardiere), from Dorset. The song appeared on their album The Wild and The Water (2018).

Below: "She Took a Gamble" by singer-songwriter Hannah Read, raised in Scotland, now based in New York City. The song appeared on her lovely album Way Out I'll Wander (2018).

Above: "Moorland Bare" by Hannah Read and Kris Drever, filmed in Sheffield for the Hudson Sessions last summer. The song was composed by Read, based on a Robert Louis Stephenson poem.

Below: "Miles to Go," based on a Robert Frost poem, performed by Hannah Read and Rowan Rheingans. The song was filmed in Sheffield for the Hudson Sessions in 2016.

Above: "Lines" by singer-songwriter Rowan Rheingans, raised in Derbyshire, now based in Sheffield. The song is from her new solo album, The Lines We Draw Together (2019) -- which follows stellar albums recorded with Lady Maisery, Songs of Separation, and The Rheingans Sisters.

Below: "What Birds Are," also from the new album.

Above: "Hummingbird" by singer-songwriter John Smith, raised in Devon, now based in Liverpool. The song appeared on his album Hummingbird (2018), a mix of traditional ballads and original songs. I highly recommend it.

Below: "Bless the Ground You Grow On" by Odette Michell, raised in Yorkshire, now based in Hertfordshire. The song is from Michell's debut album, The Wildest Rose (2019).

January 3, 2020

Bearing witness

This quote from Terry Tempest Williams has particular resonance for me today, with the world on fire in so many different ways:

"I've been thinking about what it means to bear witness. The past ten years I've been bearing witness to death, bearing witness to women I love, and bearing witness to the [nuclear] testing going on in the Nevada desert. I've been bearing witness to bombing runs on the edge of the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge, bearing witness to the burning of yew trees and their healing secrets in slash piles in the Pacific Northwest and thinking this is not so unlike the burning of witches, who also held knowledge of heading within their bones. I've been bearing witness to traplines of coyotes being poisoned by the Animal Damage Control. And I've been bearing witness to beauty, beauty that strikes a chord so deep you can't stop the tears from flowing. At places as astonishing as Mono Lake, where I've stood knee-deep in salt-water to watch the fresh water of Lee Vining Creek flow over the top like water on vinegar. It's the space of angels....

"Bearing witness to both the beauty and pain of our world is a task that I want to be part of. As a writer, this is my work. By bearing witness, the story that is told can provide a healing ground. Through the art of language, the art of story, alchemy can occur. And if we choose to turn our backs, we've walked away from what it means to be human."

In a later interview, Williams was asked how she found her voice as a writer. It was, she said,

"when I crossed the line at the Nevada Test Site in 1988. It was one year after my mother died. It was one year before my grandmother would die, and I found myself the matriarch of my family at thirty. With the death of my mother, grandmothers, and aunts -- nine women in my family have all had mastectomies, seven are dead -- you reach a point when you think, 'What do I have to lose?' and you become fearless. When I crossed that line at the Nevada Test Site as an act of protest because the United States government was still testing nuclear bombs in the desert -- it was a gesture on behalf of the Clan of the One-Breasted Women -- my mother, my grandmothers, my aunts. And I didn���t do it alone. I was with hundreds of other women who had suffered losses in Utah as a result of atomic testing, as a result of our nuclear legacy in the West. I crossed that line with Jesuit priests, with Shoshone elders, with native people who had also lost lives because of the radiation fallout in the Shivwits��� lands.

"It goes back to community. I first heard my voice when my friend David Quammen said, 'Tell me how you are.' And I looked at him and I said, 'David, I belong to a Clan of One-Breasted Women.' That was the first time I had uttered that phrase that ultimately changed my perception of the women in my family. Suddenly, I saw them as warriors, not victims. I think it���s in our conversations that we hear something come out of our mouths that we didn���t know we believed. I think in the name of community we find our voices when we take stands that we didn���t know we had the courage to take.

"I have found my voice on the page repeatedly when a question seized my throat and would not allow me to sleep. But I have to tell you -- I have to re-find my voice every time I pick up my pencil. It���s usually out of love or loss or anger. And the question then becomes: how do we take our anger and turn it into sacred rage and find a language that opens hearts rather than closes them?"

That is the question indeed.

Words: The first quote above is from Derrick Jensen's interview with Terry Tempest Williams in Listening to the Land: Conversations about Nature, Culture, and Eros (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2000). The second quote is from Devon Fredericksen's interview with Williams in Guernica Magazine ("Grounding Truth," August 1, 2013). The poem in the picture captions is from All of It Singing by Linda Gregg (Greywolf Press, 2008). All rights reserved by the authors. Many thanks to my friend Susan Harley for reminding me of these passages today.

Pictures: Dartmoor ponies (and a certain black hound) grazing on the rain-soaked grass of our village Commons.

January 2, 2020

The language of the earth

From "Speaking of Nature" by biologist, educator and author Robin Wall Kimmerer, of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation:

"I have had the privilege of spending my life kneeling before plants. As a plant scientist, sometimes I am collecting data. As an indigenous plant woman, sometimes I am gathering medicine. These two roles offer a sharp contrast in ways of thinking, but I am always in awe, and always in relationship. In both cases the plants provide for me, teach me, and inspire me. When I write as a scientist, I must say, 'An 8 cm root was extracted from the soil,' as if the leafy beings were objects, and, for that matter, as if I were too. Scientific writing prefers passive voice to subject pronouns of any kind. And yet its technical language, which is designed to be highly accurate, obscures the greater truth.

"I have had the privilege of spending my life kneeling before plants. As a plant scientist, sometimes I am collecting data. As an indigenous plant woman, sometimes I am gathering medicine. These two roles offer a sharp contrast in ways of thinking, but I am always in awe, and always in relationship. In both cases the plants provide for me, teach me, and inspire me. When I write as a scientist, I must say, 'An 8 cm root was extracted from the soil,' as if the leafy beings were objects, and, for that matter, as if I were too. Scientific writing prefers passive voice to subject pronouns of any kind. And yet its technical language, which is designed to be highly accurate, obscures the greater truth.

"Writing as an indigenous plant woman I might say, 'My plant relatives have shared healing knowledge with me and given me a root medicine.' Instead of ignoring our mutual relationship, I celebrate it. Yet English grammar demands that I refer to my esteemed healer as it, not as a respected teacher, as all plants are understood to be in Potawatomi. That has always made me uncomfortable. I want a word for beingness. Can we unlearn the language of objectification and throw off colonized thought? Can we make a new world with new words?

"Inspired by the grammar of animacy in Potawatomi that feels so right and true, I���ve been searching for a new expression that could be slipped into the English language in place of it when we are speaking of living beings. Mumbling to myself through the woods and fields, I���ve tried many different words, hoping that one would sound right to my leafy or feathered companions. There was one that kept rising through my musings. So I sought the counsel of my elder and language guide, Stewart King, and explained my purpose in seeking a word to instill animacy in English grammar, to heal disrespect. He rightly cautioned that 'our language holds no responsibility to heal the society that sought to exterminate it.' With deep respect for his response, I thought also of how the teachings of our traditional wisdom might one day be needed as medicine for a broken world. So I asked him if there was a word in our language that captured the simple but miraculous state of just being. And of course there is. 'Aakibmaadiziiwin,' he said, 'means a being of the earth. '

"Inspired by the grammar of animacy in Potawatomi that feels so right and true, I���ve been searching for a new expression that could be slipped into the English language in place of it when we are speaking of living beings. Mumbling to myself through the woods and fields, I���ve tried many different words, hoping that one would sound right to my leafy or feathered companions. There was one that kept rising through my musings. So I sought the counsel of my elder and language guide, Stewart King, and explained my purpose in seeking a word to instill animacy in English grammar, to heal disrespect. He rightly cautioned that 'our language holds no responsibility to heal the society that sought to exterminate it.' With deep respect for his response, I thought also of how the teachings of our traditional wisdom might one day be needed as medicine for a broken world. So I asked him if there was a word in our language that captured the simple but miraculous state of just being. And of course there is. 'Aakibmaadiziiwin,' he said, 'means a being of the earth. '

"I sighed with relief and gratitude for the existence of that word. However, those beautiful syllables would not slide easily into English to take the place of the pronoun it. But I wondered about that first sound, the one that came to me as I walked over the land. With full recognition and celebration of its Potawatomi roots, might we hear a new pronoun at the beginning of the word, from the 'aaki' part that means land? Ki to signify a being of the living earth. Not he or she, but ki. So that when the robin warbles on a summer morning, we can say, 'Ki is singing up the sun.' Ki runs through the branches on squirrel feet, ki howls at the moon, ki���s branches sway in the pine-scented breeze, all alive in our language as in our world.

"We���ll need a plural form of course, to speak of these many beings with whom we share the planet. We don���t need to borrow from Potawatomi since --lo and behold -- we already have the perfect English word for them: kin. Kin are ripening in the fields; kin are nesting under the eaves; kin are flying south for the winter, come back soon. Our words can be an antidote to human exceptionalism, to unthinking exploitation, an antidote to loneliness, an opening to kinship....

"I have no illusions that we can suddenly change language and, with it, our worldview, but in fact English evolves all the time. We drop words we don���t need anymore and invent words that we do. The Oxford Children���s Dictionary notoriously dropped the words acorn and buttercup in favor of bandwidth and chatroom, but restored them after public pressure. I don���t think that we need words that distance us from nature; we need words that heal that relationship, that invite us into an inclusive worldview of personhood for all beings."

You can read Kimmerer's full essay online here, and listen to a short podcast in which she talks about it with Helen Whybrow here.

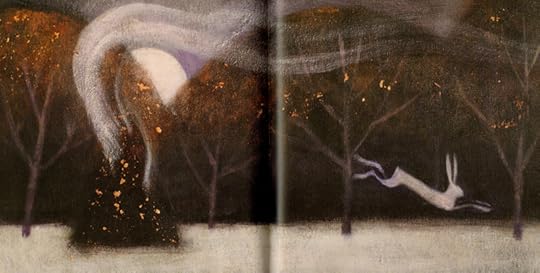

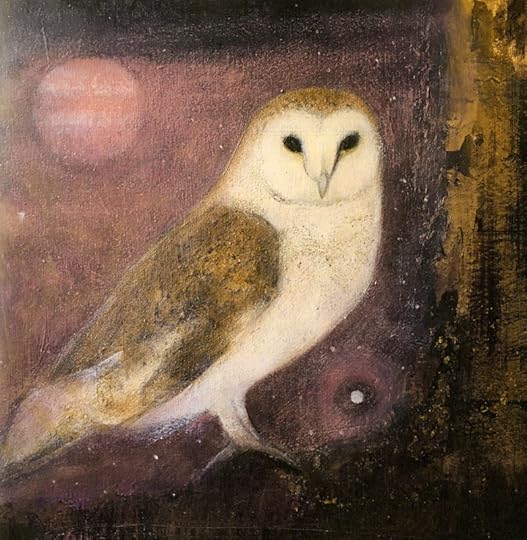

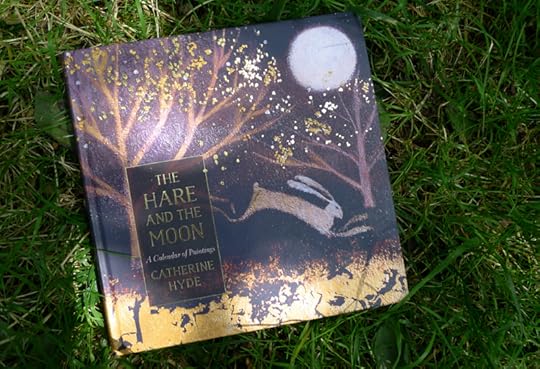

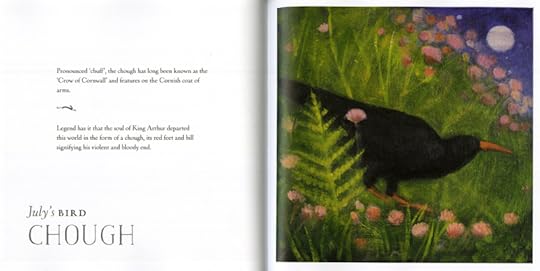

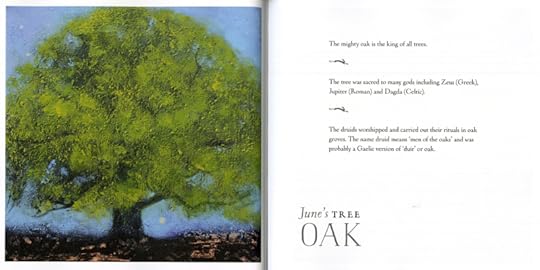

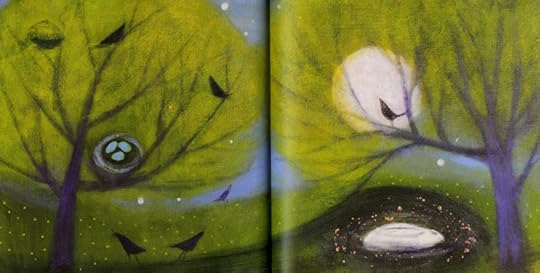

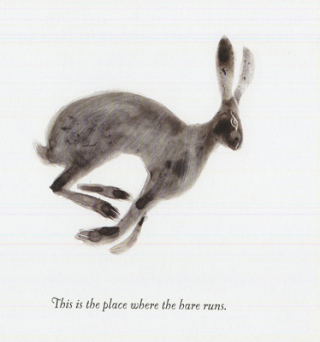

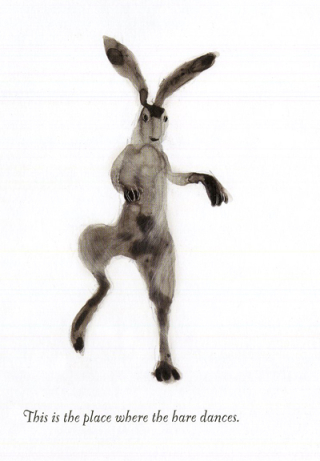

The art today is from Catherine Hyde's new book, The Hare and the Moon, a gorgeous country almanac that follows a hare's journey through the landscape, seasons, and phases of the moon. Catherine pairs her paintings with folkloric information on the tree, flower, and bird associated with each month, rendered in poetic prose that echoes the mystic lyricism of her imagery.

This book is a treasure of mythic art.

Catherine trained at Central School of Art in London, and now lives and works in Cornwall. She has published four previous books (The Princess��� Blankets, Firebird, Little Evie in the Wild Wood, The Star Tree), as well as fine art prints and calendars, and has been exhibiting her work in galleries in London, Cornwall, and father afield for over thirty years.

���I am constantly attempting to convey the landscape in a state of suspension," she says, "in order to gain glimpses of its interconnectedness, its history and beauty. Within the images I use the archetypical hare, stag, owl and fish as emblems of wildness, fertility and permanence: their movements and journeys through the paintings act as vehicles that bind the elements and the seasons together."

Please visit the artist's website to see more of her exquisite work.

The passage by Robin Wall Kimmerer is from "Speaking of Nature" (Orion Magazine, June 12,, 2017). The art and text by Catherine Hyde is from The Hare and the Moon: A Calendar of Paintings (Zephyr/Head of Zeus , 2019). All rights reserved by Kimmerer and Hyde.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers