Terri Windling's Blog, page 45

January 1, 2020

Once upon a time on New Year's Day

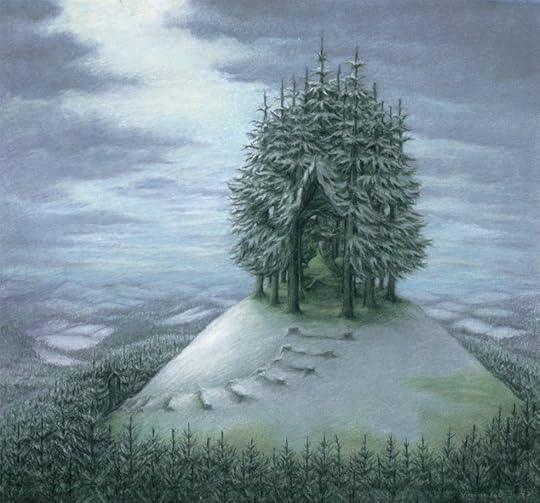

...three spirits appeared at Bumblehill: the Guardian of the Hills, the Guardian of the Fields, and the Guardian of the Hedgerows. With their elongated figures and hair of clouds, these Earth Mothers are related to the trees and keepers of the winds, protective of the little ones in their care -- but also of us, in our vulnerable moments. We all need mothering sometimes.

A New Year's Blessing: May the year ahead be magical, transformational, and wildly creative, but also calm and thoughtful, harmonious and balanced. May your pathway be clear, your workspace prepared, with the tools that you need always right near at hand. May your mind and body and spirit be strong for the things you know in your heart you must do, and may this be the year you finally do them. May your work go well, and your rest time too. May problems be fewer and friends be many. May old hurts soften and old grief lighten. May life, love, and art never fail to surprise you.

Thank you for joining me here at Myth & Moor, and being part of the mythic arts community. We'll continue the journey through the woods of myth and story in the year ahead, with stones and feathers to mark the trail and an Animal Guide to lead the way.

The three paintings above are from my Guardian series. Click on the image if you'd like to see them larger.

The three paintings above are from my Guardian series. Click on the image if you'd like to see them larger.

On the New Year and fresh starts

I've been asked to re-post this piece from a couple of years ago, and so here it is, with heartfelt thanks to the kind readers who remembered and requested it....

Over the last few days, I've been asking friends how they feel about New Year's celebrations, and from my small sampling (mostly of writers and artists) this is what I've learned:

The vast majority answered with the equivalent of a shrug: The New Year's holiday? They could take or leave it. A smaller (but emphatic) group detest it for a variety of reasons: the social pressure to be happy on New Year's eve, the guilt-tripping nature of New Year resolutions, the arbitrary designation of the year's end in the Gregorian calendar, or simply the bad timing of yet another celebration on the heels of Christmas. I found just a small minority who genuinely love New Year's Eve and Day, and I am one of them. In fact, it's my favorite holiday, so I've been thinking about the reasons why -- especially since I generally mark the changing of the seasons by the pagan, not the Christian, calendar.

I grew up with the Pennsylvania Dutch traditions of my mother's large extended family: nominally Christian, but rich in folklore, folk ways, and homely forms of folk magic. One of those traditions was my mother's practice of taking down the Christmas tree on New Year's day, cleaning the house from top to bottom, and then opening the kitchen door (with a great flourish) to sweep the old year out and welcome in the new: my mother, my great-aunt Clara, and I each taking turns with the broom. Christmas was a hard time for my mother and always ended in tears, but she would rally by New Year's day, relishing the act of making order out of chaos: a woman's ritual, shared only with me and not my half-brothers (my stepfather's sons). Boys doing housework? The very notion was unthinkable in that time and place.

At some point in the midst of all that cleaning, my mother and I would sit down at the kitchen table, eat the last of the kiffles (a traditional cookie made only at Christmas; it is bad luck to eat them past New Year's Day), and talk about plans for the year ahead. These were not New Year's resolutions, exactly; no lists were made, nothing was written down. It was more like a verbal conjuring, a vision of what we'd do differently and better, spoken at the right folkloric time when words held the power of an incantation: the pause between the old year and the new when anything seemed possible.

My mother was a great believer in new beginnings, in a way that was both painful and brave. We moved around a lot when I was young, in search of work for my stepfather, whose alcoholism and violent temper ensured that employment never lasted long. In each new place my mother would mentally sweep her troubles out the kitchen door and make a brand new start: each house, each job, each new school for my young brothers and me would be different and better, she insisted. We would finally settle down.

Since the new house was usually worse than the last, she would set herself to transforming it, ingeniously making small amounts of money go a long, long way: she'd paint our rooms in surprising colors (dictated by the paint choices in the bargain bins); make new curtains in cheap, cheery fabrics edged with bright Ric Rac and Pom Pom trim; scour yard sales for pretty new dishes and lamps (constantly broken in my stepfather's rages). For a while she'd be happy and fiercely optimistic...until the usual troubles caught up with us. There would be fights, and tears, and everything would shatter. My mother would collapse, her husband disappear to the nearest bar. Then she'd pick herself up, we'd move again, and she'd start afresh with quiet courage.

As a kid I moved even more often than my mother, shunted between her, my grandmother, my great-aunt Clara or other relatives, with a couple of stints in foster care -- and so I needed my mother's lesson in embracing change rather more than most. Many people from peripatetic childhoods react with a deep dislike of change. My own reaction is a mix of opposites. My childhood has left me with a soul-deep need for home, place, and community -- yet I also love stepping into the unknown and using the act of relocation as a catalyst for transformation and renewal. In this I am my mother's daughter. I like transitions, beginnings, the changing of the seasons, the turning of the calendar's pages. As I wrote in a previous New Year post:

I have a great affection for those moments in time that allow us to push the "re-set" buttons in our minds and make a fresh start: the start of a new year, the start of a new week, the start of a new morning or fresh endeavor. As L. M. Montgomery (author of Anne of Green Gables) once wrote, "Isn't it nice to think that tomorrow is a new day with no mistakes in it yet?"

The American abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher advised: "Every man should be born again on the first day of January. Start with a fresh page." Some people, of course, find a blank page terrifying...but that's something I've never quite understood. I love the feeling of potential inherent in an untouched notebook, a fresh white canvas, even a new computer folder waiting to be filled. It's the same sense of freedom to be found at the start of a journey, when all lies ahead and limits haven't yet been reached.

My mother died from cancer sixteen years ago, at roughly the age that I am now, and she never managed to turn those new beginnings into the calm, stable life she craved. The determined optimism she practiced wasn't always entirely admirable. Optimism can also be blind or foolish, and prevent the solving of problems through the refusal to accept reality. A fresh start can only transform a life if it is followed by the hard and clear-eyed work of making substantive change: leaving the violent husband, for example, rather than putting fresh paint on walls that will soon be bloodied once again.

But there were reasons my mother couldn't make those harder changes, so I'm not going to sit in judgement of her now. I'm just going to love her for who she was. Acknowledge her quiet bravery. And appreciate the gifts that she's passed on: kiffles and a broom on New Year's Day. And a love of new beginnings.

Yesterday I swept the house. Today I am the sweeping the studio. I'm thinking about what I'll do differently, and better.

The world is full of possibilities.

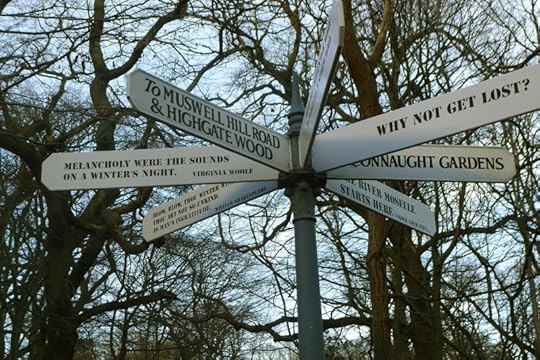

Pictures: The photographs today are from Queen's Wood, an ancient woodland in London's Muswell Hill: 52 acres of oak and hornbeam trees, abutting Highgate Wood. The pictures were taken during a Christmas holiday spent with our daughter in the city. I recommend "The History and Archaeology of Queen's Wood" by Michael Hacker if you'd like to know more about this beautiful place: a tranquil, magical piece of wild preserved within a bustling cityscape. (Tilly loved it.) The last photo was taken by Howard.

Words: The poem in the picture caption is from Tell Me by Kim Addonizio (BOA Editions, 2000); all rights reserved by the author.

December 31, 2019

Following the bear

As the old year ends, and a new one begins, and the grey winter months roll on and on, I find myself think of bears -- and of something Terry Tempest Williams once said about bears as symbols of life held in balance.

For Williams, the bear embodies "opposing views, that we can be both fierce and compassionate at once. The bear is above ground in spring and summer and below ground, hibernating, in fall and winter -- and she emerges with young by her side. I think that's a wonderful model for us, particularly as women. And it's one I've tried to adopt."

She goes on to explain that she divides her years into halves. From April Fool's Day to The Day of the Dead (November 1st), she lives a public life as a writer and activist, doing any traveling or public speaking or teaching during these months. From The Day of the Dead until April Fool's Day, however, she stays at home -- to spend time with her family; to write; to live within the rhythms of her creativity. The bear, she suggests, "offers us a model of how one lives with that paradox, of public and private life, of a creative life as well as a life of obligation."

Williams also addresses this theme in her essay "Undressing the Bear," pointing out that the she-bear has two sides her nature: both fierce and maternal, wild and nurturing. In mythic terms, this oppositional duality held in instinctive balance is the point.

"If we choose to follow the bear," she writes, "we will be saved from a distracted and domesticated life. The bear becomes our mentor. We must journey out, so that we might journey in. The bear mother enters the earth before snowfall and dreams herself through winter, emerging with young by her side. She not only survives the barren months, she gives birth. She is the caretaker of the unseen world. As a writer and a woman with obligations to both family and community, I have tried to adopt this ritual of balancing public and private life. We are at home in the deserts and mountains, as well as in our dens. Above ground in the abundance of spring and summer, I am available. Below ground in the deepening of autumn and winter, I am not. I need hibernation in order to create."

In Women Who Run With the Wolves, psychologist and storyteller Clarissa Pinkola Est��s notes the age-old connection of women and bears in the mythic traditions of many different lands. "To the ancients," she writes, "bears symbolized resurrection. The creature goes to for a long time, its heartbeat decreases to almost nothing. The male often impregnates the female right before hibernation, but miraculously, egg and sperm do not unite right away. They float separately in her uterine broth until much later. Near the end of hibernation, the egg and sperm unite and cell division begins, so that the cubs will be born in the spring when the mother is awakening, just in time to care for and teach her new offspring. Not only by reason of awakening from hibernation as though from death, but much more so because the she-bear awakens with new young, this creature is a profound metaphor for our lives, for return and increase coming from something that seemed deadened.

"The bear is associated with many huntress Goddesses: Artemis and Diana in Greece and Rome, and Muerte and Hecoteptl, mud women deities in the Latina cultures. These Goddesses bestowed upon women the power of tracking, knowing, 'digging out' the psychic aspects of all things. To the Japanese the bear is the symbol of loyalty, wisdom, and strength. In northern Japan where the Ainu tribe lives, the bear is one who can talk to God directly and bring messages back for humans. The cresent moon bear is considered a sacred being, one who was given the white mark on his throat by the Buddhist Goddess Kwan-Yin, whose emblem is the crescent moon. Kwan-Yin is the Goddess of Deep Compassion and the bear is her emissary.

"In the psyche, the bear can be understood as the ability to regulate one's life, especially one's feeling life. Bearish power is the ability to move in cycles, be fully alert, or quiet down into a hibernative sleep that renews one's energy for the next cycle. The bear image teaches that it is possible to maintain a kind of pressure gauge for one's emotional life, and most especially that one can be fierce and generous at the same time. One can be reticent and valuable. One can protect one's territory, make one's boundaries clear, shake the sky if need be, yet be available, accessible, engendering all the same."

Though Williams and Est��s are focused on women and women's issues in the passages above, the oppositional nature of bear symbology is useful to all artists, men and women alike, who struggle to balance their public and private selves, and the often-conflicting demands of family life, community engagement, and creative work. To be available to others, while protecting time to be available only to ourselves and our muse...is this not the dilemma that all creative artists (if we're not complete monsters of self-importance or self-effacement) face again and again?

And even when we are alone in the studio, the symbol of the mythic bear and cyclical hibernation is a useful one. As a culture, we tend to prize action, accomplishment, and public expression over stillness, retreat, and quiet reflection -- but creativity needs all parts of the cycle: the taking in, the pause, the putting back out. Art is born in the movement between them, the mythic rhythm at the heartbeat of our lives.

The winter months have always been a challenge for me. I love sunshine, dry weather and warmth (the hotter the better), and for many years I avoided the cold by wintering in the Arizona desert -- where bears roamed above us on the mountain peaks, but did not venture down to the heat of the valley.

By living full-time on Dartmoor now, however, I am learning to appreciate winter's stark gifts: it slows me down, turns my thoughts inward, keeps me closer to hearth and home, strengthening the introverted side of my nature, without which I couldn't write or paint. I am learning at last to follow the bear; to trust in the process of hibernation and gestation. I am learning patience. Slowness. Stillness.

All things have their season. And spring always comes.

It's a good time of year to be reading about bears -- in fiction, nonfiction, poetry and myth. The bearish tales above are three of my favourites, along with Margo Lanagan's Tender Morsals, Judith Berman's Bear Daughter, and Marion Engle's strange but compelling Bear. What are some of yours...?

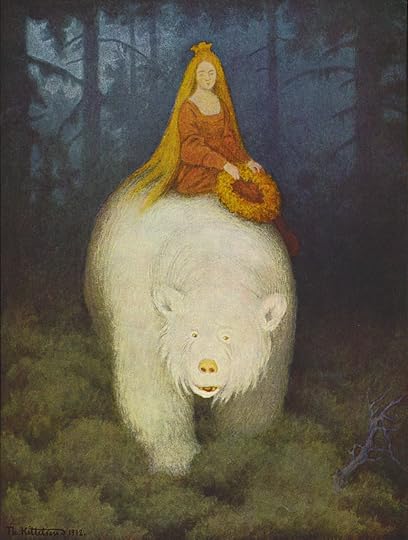

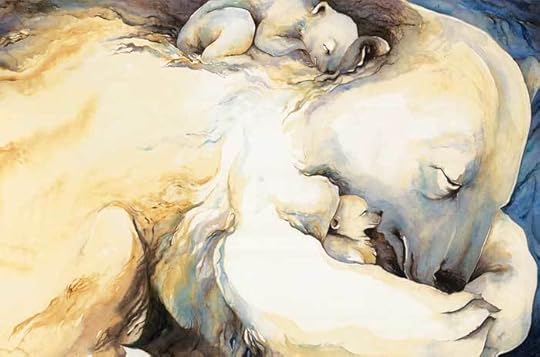

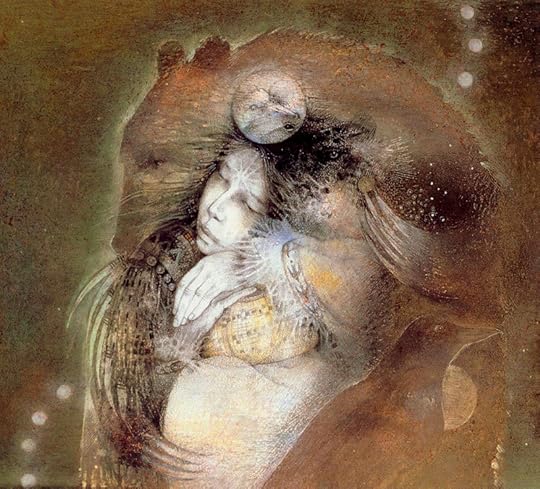

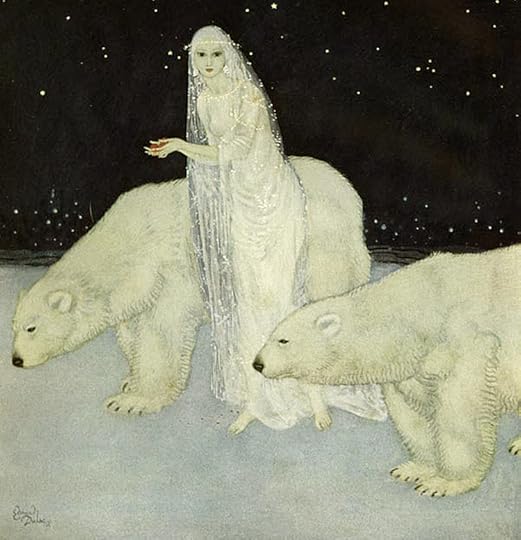

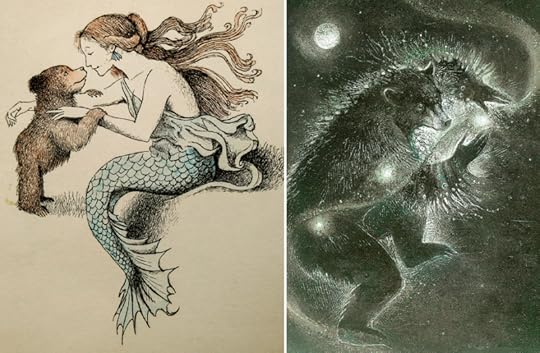

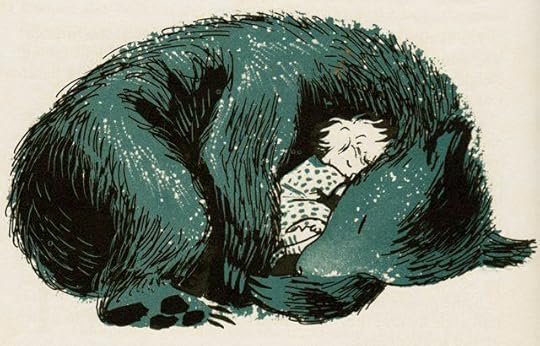

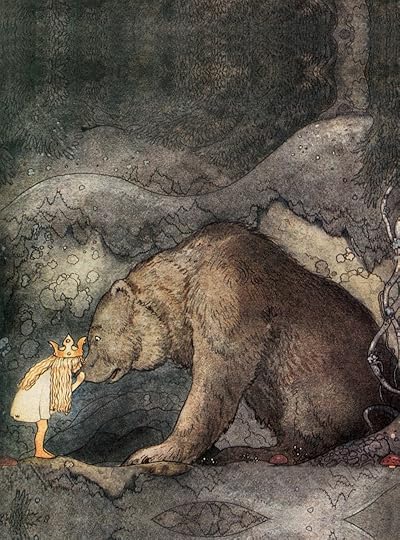

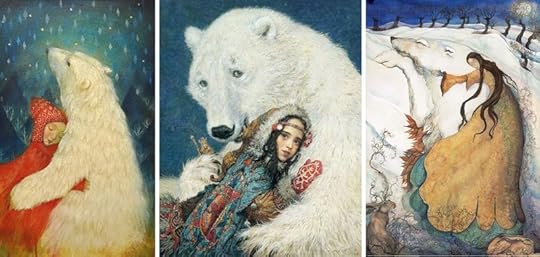

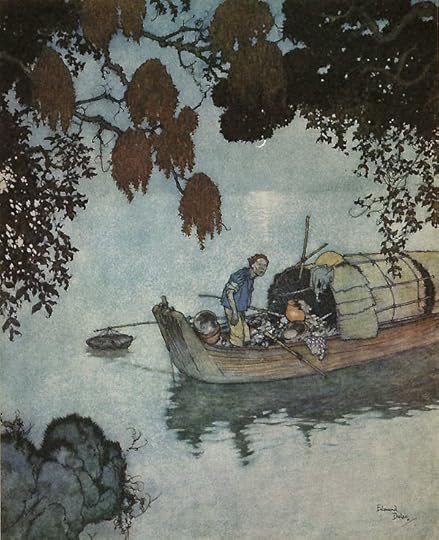

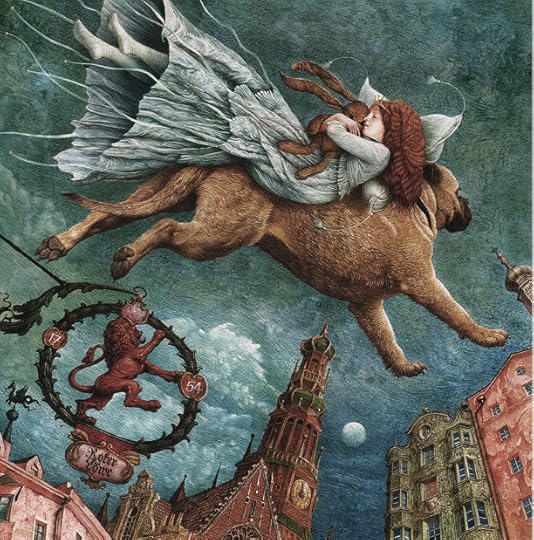

Pictures: The bear art above is by Theodore Kittelsen, Jackie Morris, Katerina Plotnikova, Susan Seddon Boulet, Edmund Dulac, Maurice Sendak, Gene Tobey, L��ga K��avi��a, Trina Schart Hyman, John Bauer and Marc Simont. Titles and artist credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights reserved by the artists.

Words: The passages quoted above are from A Voice in the Wilderness: Conversations with Terry Tempest Williams by Michael Austin (Utah State University Press, 2006); "Undressing the Bear," published in An Unspoken Hunger: Stories from the Field by Terry Tempest Williams (Vintage, 1994); and Women Who Run with the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Est��s (Ballentine, 1992). All rights reserved by the authors.

December 30, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, music for the turning of the year....

Above: "The Bear Song" by Lady Maisery (Hannah James, Rowan Rheingans, Hazel Askew), with Jimmy Aldridge and Sid Goldsmith. I love this song, which is from their new album, Awake Arise (2019). The whole album is superb.

Below: "The King," also from Awake Arise. This song is the traditional blessing of the "wrenboys" on St. Stephen's Day (December 26). You can read more about this old folk practice here.

Above: "Banks of Inverurie," a wintry performance of a traditional Scottish ballad from Iona Fyfe. "The Banks of Inverurie echoes the form and structure of the American folksong, The Lakes of Pontchartrain," notes the singer. "The definite origins of the song remain unknown, but it is thought that it originated in Scotland and was brought to America by soldiers fighting for the British army in Louisiana and Canada in 1812. It could be argued that Aberdeenshire is the source region of the localised song, by its inclusion in Greig-Duncan and the song being set on the banks of the River Ury." The song can be found on Fyfe's lovely album Away From My Window (2018).

Below: "Vinterfolk" performed by The String Sisters during a recording session in the Shetland Islands. The String Sisters are: Annbj��rg Lien (Norway), Catriona Macdonald (Shetland), Emma H��rdelin (Sweden), Liz Carroll (U.S.), Liz Knowles (U.S.) abd Mair��ad N�� Mhaonaigh (Ireland) -- accompained by Tore Bruvoll on guitar, Dave Milligan on piano, Conrad Molleson on bass, and James Mackintosh on percussion. The song, written by Tore Bruvoll, appeared on their album Between Wind And Water (2017).

Above: "Ca' the Yowes" performed by Band of Burns from their fine new album The Thread. You'll find more of their music in this previous post.

Below: "The Parting Glass" performed by Scottish singer Emily Smith, from her seasonal album Songs for Christmas (2016). More information on this old Scottish ballad can be found here.

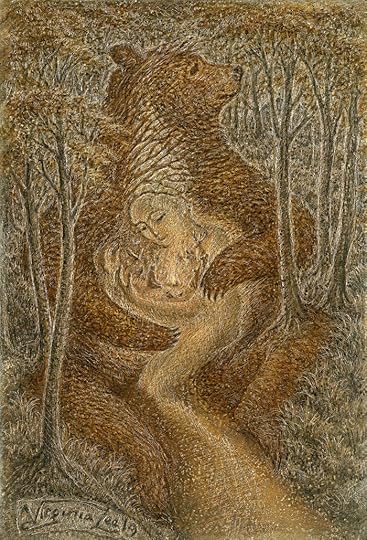

The wonderful, wonderful art today is "Embraced by the Bear" and "Time Out" by my friend and village neighbour Virginia Lee. To see more her work, go here.

December 26, 2019

Myth & Moor update

The Bumblehill Studio is closed for the winter holidays through Sunday, December 29th. Myth & Moor with resume on Monday.

The illustrations above are by P.J. Lynch (East of the Sun, West of the Moon); Lucy Campbell, Anton Lomaev, and Jackie Morris.

December 25, 2019

To everyone in the Mythic Arts community...

December 24, 2019

The Folklore of Winter

I'm been asked to re-post this piece on the tales and folk customs of winter holiday season. Happy holidays from all of us at Bumblehill and Myth & Moor....

A cold wind howls, stripping leaves off of the trees, and the pathways through the hills are laced with frost. It's time to admit that winter is truly here, and it's here to stay. But Howard keeps the old Rayburn stove in the kitchen well fed, so our wind-battered little house at the edge of the village is cozy and warm. Our Solstice decorations are up, and tonight I'll make a second batch of kiffles: the Christmas cookies passed on through generations of women in my mother's Pennsylvania Dutch family...carried now to England and passed on to our daughter, who may one day pass it to children of her own.

My personal tradition is to talk to those women of the past generations as I roll out the kiffle dough and cut, fill, roll, and shape each cookie: to my mother, grandmother, and old great-aunts (all of whom have passed on now)...and further back, to the women in the family line that I never knew.

Kiffles are a labor-intensive process (as so many of those fine old recipes were), so I have plenty of time to tell the Grandmothers news and stories of the year gone by. This annual ritual centers me in time, place, lineage, and history; it keeps my world turning through the seasons, as all storytelling is said to do. Indeed, in some traditions there are stories that can only be told in the wintertime.

Here in Devon, there are certain "piskie" tales told only in the winter months -- after the harvest is safely gathered in and the faery rites of Samhain have passed. In previous centuries, throughout the countryside families and neighbors gathered around the hearthfire during the long, dark hours of the winter season,  gossiping and telling stories as they labored by candle, lamp, and firelight. The "women's work" of carding, spinning, and sewing was once so entwined with storytelling that Old Mother Goose was commonly pictured by the hearth, distaff in hand.

gossiping and telling stories as they labored by candle, lamp, and firelight. The "women's work" of carding, spinning, and sewing was once so entwined with storytelling that Old Mother Goose was commonly pictured by the hearth, distaff in hand.

In the Celtic region of Brittany, the season for storytelling begins in November (the Black Month of Toussaint), goes on through December (the Very Black Month), and ends at Christmas. (A.S. Byatt, you may recall, drew on this tradition in her wonderful novel Possession.) In early America, some of the Puritan groups which forbade the "idle gossip" of storytelling relaxed these restraints at the dark of the year, from which comes a tradition of religious and miracle tales of a uniquely American stamp: Old World folktales transplanted to the New and given a thin Christian gloss. Among a number of the different Native American nations across the continent, winter is also considered the appropriate time for certain modes of storytelling: a time when long myth cycles are told and learned and passed through the generations. Trickster stories are among the tales believed to hasten the coming of spring. Among many tribes, Coyote stories must only be told in the dark winter months; at any other time, such tales risk offending this trickster, or drawing his capricious attention.

In myth cycles to be found around the globe, the death of the year in winter was echoed by the death and rebirth of the Winter King (also called the Sun King, or Year King), a consort of the Great Goddess  (representing the earth's fertility) in her local guise. The rebirth or resurrection of her consort (representing the sun, sky, or quickening winds) not only brought light back to the world, turning the seasons from winter to spring, but also marked a time of new beginnings, cleansing the soul of sins and sicknesses accumulated in the twelve months passed. Solstice celebrations of the ancient world included the carnival revels of Roman Saturnalia (December 17-24), the Anglo-Saxon vigil of The Night of the Mother to renew the earth's fertility (December 24th), the Yule feasts of the Norse honoring the One-Eyed God and the spirits of the dead (December 25), the Persian Mithric festival called The Birthday of the Unconquered Sun (December 25th), and the more recent Christian holiday of Christmas, marking the birth of the Lord of Light (December 25th).

(representing the earth's fertility) in her local guise. The rebirth or resurrection of her consort (representing the sun, sky, or quickening winds) not only brought light back to the world, turning the seasons from winter to spring, but also marked a time of new beginnings, cleansing the soul of sins and sicknesses accumulated in the twelve months passed. Solstice celebrations of the ancient world included the carnival revels of Roman Saturnalia (December 17-24), the Anglo-Saxon vigil of The Night of the Mother to renew the earth's fertility (December 24th), the Yule feasts of the Norse honoring the One-Eyed God and the spirits of the dead (December 25), the Persian Mithric festival called The Birthday of the Unconquered Sun (December 25th), and the more recent Christian holiday of Christmas, marking the birth of the Lord of Light (December 25th).

Many symbols we associate with Christmas today actually come from older ceremonies of the Solstice season. Mistletoe, holly, and ivy, for instance, were gathered in their magical potency by moonlight on Winter Solstice Eve, then used throughout the year in Celtic, Baltic and Germanic rites. The decoration of evergreen trees can be found in a number of older traditions: in rituals staged in decorated pine groves (the pinea silvea) of the Great Goddess; in the Roman custom of dedicating a pine tree to Attis on Winter Solstice Day; and in the candlelit trees of Norse Yule celebrations, honoring Frey and Freyja in their aspects of Hunter, Huntress, and Protectors of Forests. The Yule Log is a direct descendant from Norse and Anglo-Saxon rites; and caroling, pageantry, mummers plays, eating plum puddings, and exchanging gifts are all elements of Solstice celebrations handed down from the pre-Christian world.

Even the story of the virgin birth of a Divine, Heroic or Sacrificial Son is not a uniquely Christian legend, but one found in cultures all around the globe -- from the myths of Asia, Africa and old Europe to Native American tales. In ancient Syria, for example, a feast on the 25th of December celebrated the Nativity of the Sun; at midnight the sun was born in the form of a child to the Virgin Queen of Heaven, an aspect of the the goddess Astarte.

Likewise, it is interesting to note that the date chosen for New Year's Day in the Western world is a relatively modern invention. When Julius Caesar revised the Roman calendar in 46 BC, he chose January 1 -- following the riotous celebrations of Saturnalia -- as the official beginning of the year. Early Christians condemned the date as pagan, tied to licentious practices, and much of Europe resisted the Julian calendar until the  Gregorian reforms in the 16th century; instead, they celebrated New Year's Day on the 25th of December, the 21st of March, or various other dates. (England first adopted January 1 as New Year's Day in 1752).

Gregorian reforms in the 16th century; instead, they celebrated New Year's Day on the 25th of December, the 21st of March, or various other dates. (England first adopted January 1 as New Year's Day in 1752).

The Chinese, Jewish, Wiccan and other calendars use different dates as the start of the year, and do not, of course, count their years from the date of Christ's birth. Yet such is the power of ritual and myth that January 1st is now a potent date to us, a demarcation line drawn between the familiar past and the unknowable future. Whatever calendar you use, the transition from one year into the next is the traditional time to take stock of one's life -- to say goodbye to all that has passed and prepare for a new life ahead. The Year King is symbolically slain, the sun departs, and the natural world goes dark. Rituals, dances, pageants, and spiritual vigils are enacted in lands around the world to propitiate the sun's return and keep the great wheel of the seasons rolling.

Special foods are eaten on New Year's Day to ensure fertility, luck, wealth, and joy in the year to come: pancakes in France, rice cakes in Ceylon, new grains in India, and cake shaped as boar in Estonia and Sweden, among many others. In my family, we ate the last of those scrumptious kiffles...if they'd managed to last that long. They could not, by tradition, be made again before December of the following year, and so the last bite was always a little sad (and especially delicious). The Christmas tree and decorations were taken down on New Year's Day, and the house was thoroughly cleaned and swept: this was another Pennsylvania Dutch custom, brushing out any bad luck lingering from the year behind, making way for good luck to come.

May you have a lovely winter holiday, in whatever tradition you celebrate, full of all the magic of home and hearth, oven and table, and the wild wood beyond.

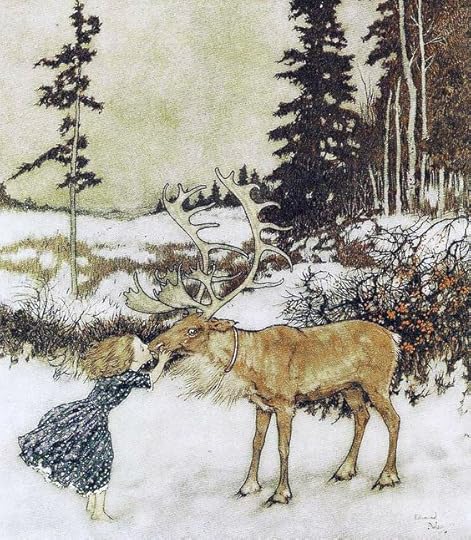

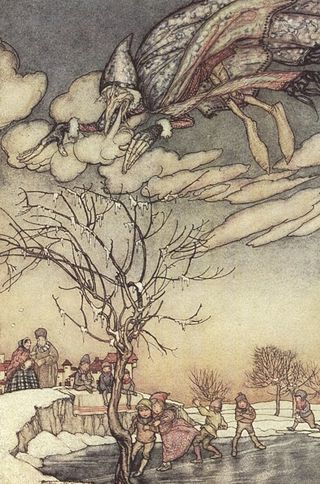

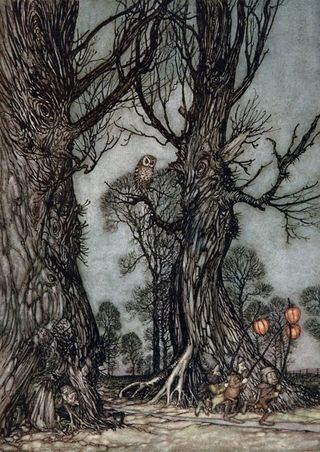

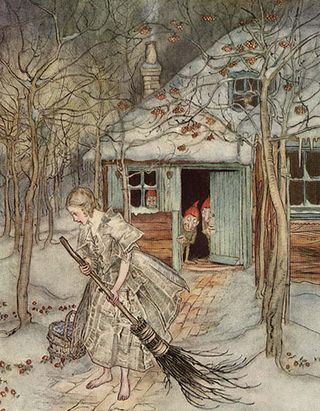

The paintings above are by three great artists of the Golden Age of Book illustration: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), and Charles Robinson (1870-1937). You'll find titles in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) I recommend a related article by Derek Johnstone, published in The Conversation: "Why Ghosts Haunt England at Christmas But Steer Clear of America." Also, don't miss "Father Christmas: A New Tale of the North," a perfectly magical story by Charles Vess.

Tunes for a Tuesday Morning

My apologies for the paucity of posts in the last week; a combination of work, health issues, and holiday preparations seemed to have swallowed up all my time. I'm a day late, but here's music to kick off the week: folk carols, new Christmas ballads, and interesting renditions of traditional tunes.

Above: "Up the Morning Early/The Christmas Road" by Lady Maisery (Hannah James, Rowan Rheingans, Hazel Askew), with Jimmy Aldridge and Sid Goldsmith, from their absolutely gorgeous new album, Awake Arise (2019).

Below: "We Shall Sing All Merrily," from the same album.

Above: "Christmas is Merry" by Yorkshire singer/songwriter Kate Rusby. The song comes appears on her lovely new Christmas album Holly Head (2019)

Below: "The Holly King" by Kate Rusby, from the same album.

Above: "At the Time of Year," a new Christmas single by Scottish singer/songwriter Siobhan Miller.

Below: "The Wexford Carol," a new Christmas single by Aizle, a folk band based in Manchester, with Irish-born singer and flautist R��oghnach Connolly.

Below: I'll end, as I often do, with my favourite Christmas video: a wacky (and very pagan) rendition of "God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen" by the great Annie Lennox.

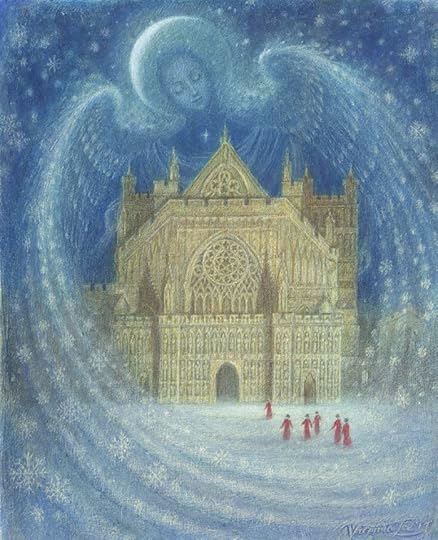

The exquisite art today is by my friend and village neighbour Virginia Lee: "Catherdal Dreams," a portrait of Exeter Cathedral (Exeter is our closest city), and the magic winter's vision of "The Deer's Domain."

December 22, 2019

By the Light of the Moon and Stars

"The world rests in the night," writes John O'Donohue. "Trees, mountains, fields, and faces are released from the prison of shape and the burden of exposure. Each thing creeps back into its own nature within the shelter of the dark. Darkness is the ancient womb. Night-time is womb-time. Our souls come out to play...."

"Sometimes, when you're deep in the countryside, you meet three girls, walking along the hill tracks in the dusk, spinning. They each have a spindle, and on to these they are spinning their wool, milk-white, like the moonlight. In fact, it is the moonlight, the moon itself, which is why they don't carry a distaff. They're not Fates, or anything terrible; they don't affect the lives of men; all they have to do is to see that the world gets its hours of darkness, and they do this by spinning the moon down out of the sky. Night after night, you can see the moon getting less and less, the ball of light waning, while it grown on the spindles of the maidens. Then, at length, the moon is gone, and the world has darkness, and rest."

- Mary Stewart (The Moonspinners)

"Night falls. Or has fallen. Why is it that night falls, instead of rising, like the dawn? Yet if you look east, at sunset, you can see night rising, not falling; darkness lifting into the sky, up from the horizon, like a black sun behind cloud cover. Like smoke from an unseen fire, a line of fire just below the horizon, brushfire or a burning city. Maybe night falls because it���s heavy, a thick curtain pulled up over the eyes. A wool blanket."

- Margaret Atwood (A Handmaid's Tale)

"Night does not show things, it suggests them. It disturbes and surprises us with its strangeness. It liberates forces within us which are dominated by our reason during the daytime."

- Brassa�� (Gyula Hal��sz)

"The message of the lullaby is that it���s okay to dim the eyes for a time, to lose sight of yourself as you sleep and as you grow: if you drift, it says, you���ll drift ashore: if you fall, you will fall into place."

- Kevin Brockmeier ("These Hands")

"Anything seems possible at night when the rest of the world has gone to sleep."

- David Almond (My Name is Mina)

"Night is a time of rigor, but also of mercy. There are truths which one can see only when it���s dark."

- Isaac Bashevis Singer (Teibele And Her Demon)

"Our fantastic civilization has fallen out of touch with many aspects of nature, and with none more completely than with night. Primitive folk, gathered at a cave mouth round a fire, do not fear night; they fear, rather, the energies and creatures to whom night gives power; we of the age of the machines, having delivered ourselves of nocturnal enemies, now have a dislike of night itself. With lights and ever more lights, we drive the holiness and beauty of night back to the forests and the sea; the little villages, the crossroads even, will have none of it.

"Are modern folk, perhaps, afraid of night? Do they fear that vast serenity, the mystery of infinite space, the austerity of stars? Having made themselves at home in a civilization obsessed with power, which explains its whole world in terms of energy, do they fear at night for their dull acquiescence and the pattern of their beliefs? Be the answer what it will, today's civilization is full of people who have not the slightest notion of the character or the poetry of night, who have never even seen night. Yet to live thus, to know only artificial night, is as absurd and evil as to know only artificial day."

- Henry Beston (The Outermost House)

Look, as the day slows towards the space

that draws it into dusk: rising became

upstanding, standing a laying down, and then

that which accepts its lying blurs to darkness.

Mountains rest, outgloried be the stars -

but even there, time���s transition glimmers.

Ah, nightly refuged in my wild heart,

roofless, the imperishable lingers.

- Rainer Maria Rilke (Uncollected Poems: 1912-1922, translation by Susan Ranson & Marielle Sutherland)

"This is the ending. Now not day only shall be beloved, but night too shall be beautiful and blessed and all its fear pass away."

- J.R.R. Tolkien (The Return of the King)

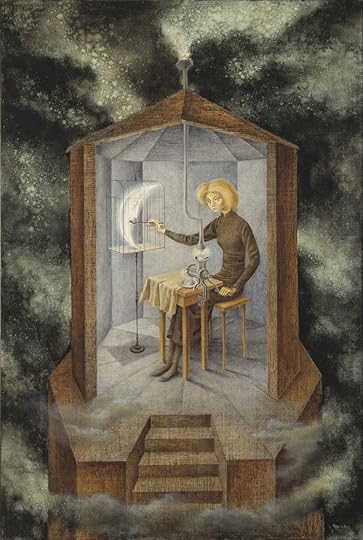

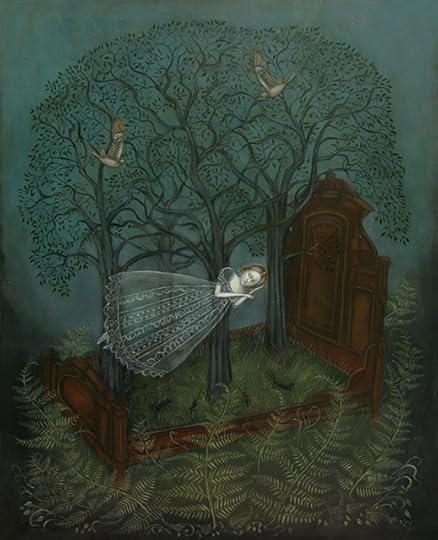

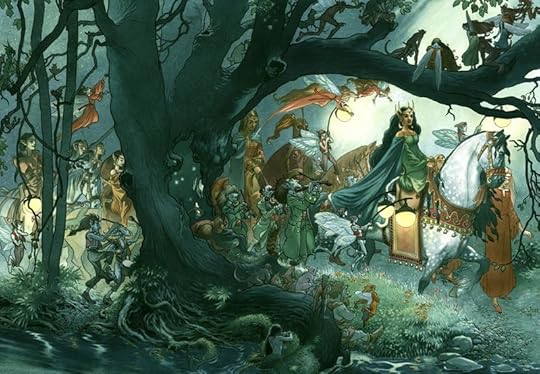

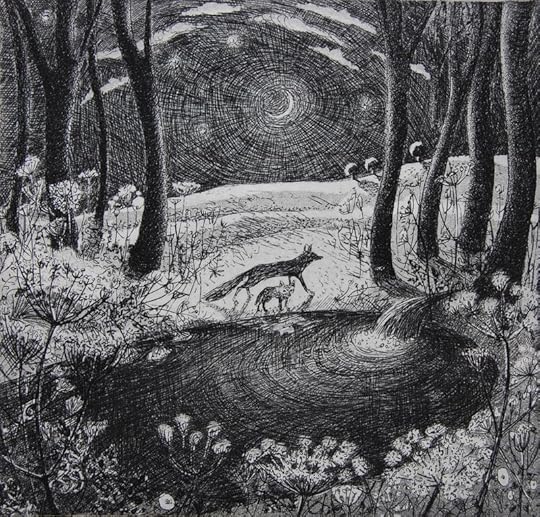

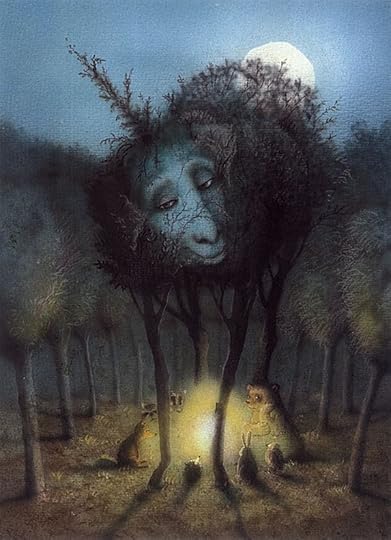

The illustrations above are : "Trolls" by John Bauer (1882-1918), "Celestial Pablum" by Remedios Varo (1908-1963), "Presently" by Jeanie Tomanek, "The Woods are Lovely, Dark and Deep" by Catherine Hyde, "The Arabian Nights: Descent" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), a drawing from the "Inner Seasons" series by Virginia Lee, "A Midsummer Night's Dream" by Arthur Rackham (1887-1969), "Kip the Enchanted Cat" by Adrienne S��gur (1901-1981), "The Nightingale: The Fisherman Stops to Listsen" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), "Murmur of Pearls" by Gina Litherland, "The Tin Soldier: The Dog Carries the Princess on His Back" by Vladislav Erko, "Companions to the Moon" by Charles Vess, "A Midsummer Night's Dream: Oberon and Titania" by Arthur Rackham (1887-1969), "Forest Sleep" by Kelly Louise Judd, "Marianna and the Whippets" by David Wyatt, "The Hidden Pool" by Flora McLachlan, "Eclipse" by Jeanie Tomanek, "Crossing the River" by Catherine Hyde, "Starfall" by Flora McLachlan, "The Wind and the Willows" by Inga Moore, and "The Legendary Unicorn" by Julia Gukova. All rights to the imagery and text above are reserved by the artists and authors.

December 21, 2019

On Winter Solstice

The title of this magical animation by paper cut artist Angie Pickman refers to the Winter Solstice...but it's also symbolic of other "long nights" we face in life, such periods of grief, hardship, illness, trauma...or political and cultural upheaval.

We are always on a journey from darkness into light, the Irish poet/philosopher John O'Donohue reminds us:

"At first, we are children of the darkness. Your body and your face were formed first in the kind darkness of your mother's womb. You lived the first nine months in there. Your birth was the first journey from darkness into light. All your life, your mind lives within the darkness of your body. Every thought you have is a flint moment, a spark of light from your inner darkness. The miracle of thought is its presence in the night side of your soul; the brilliance of thought is born of darkness. Each day is a journey. We come out of the night into the day. All creativity awakens at this primal threshold where light and darkness test and bless each other. You only discover the balance in your life when you learn to trust the flow of this ancient rhythm."

In the mythic sense, we practice moving from darkness into light every morning of our lives. The task now is make that movement larger, to join together to carry the entire world through the long night to the dawn.

The art above is"The Spirit Within" by Karen Davis (UK); "Stray" and "Capturing the Moon" by Jeanie Tomanek (US). The video is by Angie Pickman (US); go here to see more of her work. The quote is from Anam Cara (Bantam Books, 1997) by John O'Donhue (1956-2008, Ireland). All right to the video and art above are reserved by the artists; all rights to O'Donohue's text are reserved by his estate.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers