Terri Windling's Blog, page 49

November 5, 2019

Life as kintsugi

In her beautiful little book Broken Spaces & Outer Spaces: Finding Creativity in the Unexpected, Nnedi Okorafor writes about how she found her vocation as an author of African-based science fiction and fantasy. She'd gone to university intending to focus on science and athletics, until a shattering experience took her down another path completely:

"Ultimately, I lost my faith in science after an operation left me paralyzed from the waist down. It took years, but battling through my paralysis was the very thing that ignited my passion for storytelling and the transformative power of the imagination. And returning to Nigeria brought me back around to the sciences through science fiction, for those family trips to Nigeria were where and why I started wondering and then dreaming about the effects of technology and where it would take us in the future.

"This series of openings and awakenings led me to a profound realization: What we perceive as limitations have the power to become strengths greater than what we had when we were 'normal' or unbroken. In much of science fiction, when something breaks, something greater often emerges from the cracks. This is a philosophy that positions our toughest experiences not as barriers, but as doorways, and may be the key to us becoming our truest selves.

"In Japan there is an art form called kintsugi, which means 'golden joinery,' to repair something with gold. It treats breaks and repairs as part of an object's history. In kintsugi, you don't merely fix what's broken, you repair the total object. In doing so, you transform what you have fixed into something more beautiful than it previously was. This is the philosophy that I came to understand was central to my life. Because in order to really live life, you must live life. And that is rarely achieved without cracks along the way. There is often a sentiment that we must remain new, unscathed, unscarred, but in order to do this, you must never leave home, never experience, never risk or be harmed, and thus never grow."

This passage from Nnedi's brave, wise book spoke to me especially, for I have long believed in living my life as a form of kintsugi. I, too, carry numerous scars, both physical and psychological, but I think of them as ribbons of gold. To be broken and then to be repaired, or to repair ourselves, can be a very powerful source of art. Of beauty. Of strength. Even of joy.

To read more about kintsugi, here's a previous post: The beauty of brokeness.

In a similar vein I recommend The Jagged, Gilded Script of Scars by American essayist Alice Driver, and the late Irish poet John O'Donohue on The art of vulnerability.

The passage quoted above is from Broken Places & Outer Spaces by Nnedi Okorafor (TED Books/Simon & Schuster, 2019), which is highly recommended. Many thanks to Stephanie Burgis for recommending it. The poem in the picture captions is from Facts About the Moon by Dorianne Laux (W.W. Norton & Co, 2007). All rights reserved by the authors.

November 3, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I've been listening to a lot of Nordic folk music while Howard has been in Helsinki, so let's start the week with music from our European neighbours to the north....

Above: "When the Land is White With Snow" by the Finnish band Frigg, from their album Joululaulut (2018).

Below: "Return from Helsinki" by Frigg, from their album Keidas-Oasis-Oase (2005).

Above: "Typhoon Nozaki" by V��sen (Olov Johansson, Mikael Marin, and Roger Tallroth), from Sweden. The song appears from their album Rule of Three (2019).

Below: "Kind of Polska" by The Gjermund Larsen Trio (Laresen, Sondre Meisfjord, and Andreas Utnem), from Norway, and Nordic (Anders L��fberg, Erik Rydvall, and Magnus Zetterlund), from Sweden. The tune appears on The Gjermund Larsen Trio's album Salmeklang (2016).

Above: A Swedish herding song performed by Jonna Jinton. She says: "The singing technique called kulning was used by women long time ago to call the cows and goats back home to the farm in the evenings. It was also used as a form of communication, since the high pitch sounds can be heard through very far distances. I sang this one to the cows one last time before they went back to their winter farm. I love seeing them running towards me as I sing, especially my favorite cow, Stj��rna (Star), who is always the first one to come."

Below: A Swedish herding song performed by ��sa Larsson (of Resmiranda). "We went for a walk in the magical midsummer night and met these beautiful cows who came close when I started to kula. Midsummer's eve is associated with mystery and magic in Swedish folklore tradition. One ritual that lives on until today is to pick seven kinds of flowers and put them under your pillow. The person you dream of that night, is the person you will spend your life with." (To watch Larsson kula to a wild swan, go here.)

Above: "Timelapse" by Norwegian violinist Mari Samuelsen, with the Trondheim Soloists, from her album Nordic Noir (2017)

Below: "Devil's Polska" by the Finnish/Irish trio Slow Moving Clouds (Aki, Danny Diamond, and Kevin Murphy) from their album Os (2015).

Howard returned from Helsinki this weekend and is now in London for the next month, teaching Commedia at East15 Acting School. His Fool's Journey continues throughout the year (the next training session is in France in December) -- so our Funding for Foolery campaign continues too. Can you help us reach our funding goal? Our entire family sends a big thank you to all of you who have contributed already, along with enthusiastic tail thumps from Tilly.

Images above: A traditional nycklelharpa; and cows here in Chagford, waiting to be sung to.

More Myth & Moor news

Thanks entirely to Patreon supporters and some very good friends, I now have help in the studio for several hours each week. Please meet Lunar Hine: writer, painter, Chagford neighbour...and now officially my Editorial Assistant.

Lunar is helping me to get the office organised, deal with the backlog of admin work, and get rolling on creative projects stymied by health issues or sheer lack of time. You'll see those projects unfolding soon: digital publishing, art, and more. Having her here is such a blessing.

Lunar is helping me to get the office organised, deal with the backlog of admin work, and get rolling on creative projects stymied by health issues or sheer lack of time. You'll see those projects unfolding soon: digital publishing, art, and more. Having her here is such a blessing.

Some of you will know Lunar already, from the lovely blog she writes about art, motherhood and Dartmoor life. In addition to her own fine work (which includes poetry, flash-fiction, a novel-in-progress, and visual art), she's the executor of the writing and art of her late husband, folklorist Thomas Hine.

With Lunar's help, I've been catching up on a number of things -- including my Patreon page. All of the print rewards have been sent out now (so if you haven't gotten yours yet, please let us know) -- and new posts are up, with more coming this week. We've also posted a five-part video in which I answer questions sent in by Patreon supporters -- on fantasy literature, writing, balancing creativity with illness, and more. Here's a very small sample from the last video (with my good friend Ellen Kushner behind the camera, and Tilly's little head popping up at the bottom):

The full videos are available only on Patreon, I'm afraid, but you can join my page for as little ��1 (or $1) per month. We're now gathering questions for the next video, which I'm aiming to film and put up in early December. And we've got some other video surprises in store. More about that soon....

If you'd like to know more about why I decided to launch a Patreon page, please see this previous post: On becoming a public storyteller.

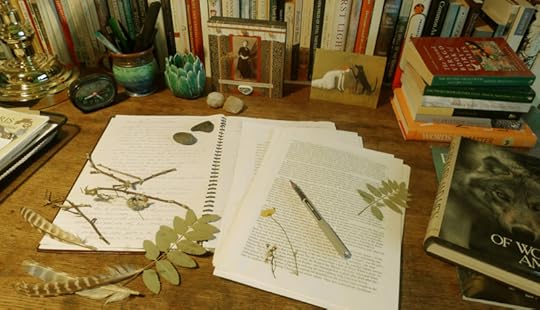

Pictures above: Lunar and Tilly in the studio, wild words on my desk, and border art by the great Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

November 1, 2019

Myth & Moor news

To friends & publishing colleagues heading to the World Fantasy Convention in Los Angeles this weekend: I hope you have a wonderful time, and I wish I could be there with you. I feel deeply honored that Myth & Moor has been nominated for this year's World Fantasy Award, and raise this toast to my fellow nominees -- as well as to my dear old friend Beth Meacham, who is the editor Guest of Honor this year. (And well deserved too.)

"We who hobnob with hobbits and tell tales about little green men," Ursula Le Guin once said, "are used to being dismissed as mere entertainers, or sternly disapproved of as escapists. But I think perhaps the catagories are changing, like the times. Sophisticated readers are accepting the fact that an improbable and unmanageable world is going to produce an improbable and hypothetical art. At this point, realism is perhaps the least adequate means of understanding or portraying the incredible realities of our existence."

Death in Folklore and Fairy Tales

In honor of the Days of the Dead (November 1 -4) and All Soul's Day (Nov 2)....

Once upon a time there was a poor tailor who could barely feed his twelve children. When the thirteenth was born, the distraught man ran out to the road nearby determined to find someone to stand as godfather to the child. He knew of no other way that he could provide for his newborn son. The first person to pass was God, but the poor tailor rejected him. "God gives to the rich and takes from the poor. I'll wait for another to come." The second to pass was the Devil, but the poor tailor rejected him too. "He lies and cheats and leads good men astray. I'll wait for another." The third man to pass was Death, and the poor tailor considered him carefully. "Death treats all men alike, whether rich or poor. He's the one I'll ask."

Now Death had never been asked such a thing before, but he agreed at once. "Your child shall lack for nothing," he said, "for I am a powerful friend indeed." The years went by and he kept his word. The boy and his family lacked for nothing. When the boy finally came of age, his Godfather Death appeared before him. "It is time to establish you in the world. You are to become a great physician. Take this magical herb, the cure for any malady of this earth. Look for me when you're called to a patient's bed. If you see me at its head then give them a tincture of the herb and your patient will be well. But if you see me at the foot, you'll know it is their time to die. Your diagnosis will always be right, and you will be famous around the world."

Now Death had never been asked such a thing before, but he agreed at once. "Your child shall lack for nothing," he said, "for I am a powerful friend indeed." The years went by and he kept his word. The boy and his family lacked for nothing. When the boy finally came of age, his Godfather Death appeared before him. "It is time to establish you in the world. You are to become a great physician. Take this magical herb, the cure for any malady of this earth. Look for me when you're called to a patient's bed. If you see me at its head then give them a tincture of the herb and your patient will be well. But if you see me at the foot, you'll know it is their time to die. Your diagnosis will always be right, and you will be famous around the world."

And so it was. The young man became the most famous doctor of his time, and his fame spread far and wide until it reached the ears of the king. The king lay sick in his golden bed and he summoned the tailor's son to him. But when the young doctor arrived at last in the richly appointed bedchamber, he saw that the king was gravely ill and that Death stood at his feet. Now this king was much beloved and the young man wanted to cure him very much. He quickly instructed the court attendants to turn the bed the opposite way, and he then restored the king to health with a tincture of the magical herb. Death was not pleased. He shook his long, bony finger at his godson and said, "You must never cheat me again. If you do, it will be the worse for you."

The young man took this warning to heart and did not cross his godfather again -- until the king's daughter fell ill and he was summoned back to the palace. This was the good king's only child. He was desperate to see her well. "Save her life," said the king, "I shall give you her hand in marriage." The doctor went to the lovely maiden's bedchamber, where Death was waiting. He stood at the foot of the princess's bed, ready to take her away. "Don't cross me again," his godfather warned, but the doctor was half in love already. He ordered the princess's bed to be turned and he gave her the herbal tincture.

The princess was healed immediately, but Death reached out a cold, white hand and clamped it on his godson's arm, saying. "You'll go with me instead." He took the young man into a cave, its wall niches covered with millions of candles. "Here," he said, "are candles burning for every life upon the earth. Each time a candle grows low and snuffs out, a life is ended. This one is yours." Death pointed to a candle that had burned down to a pool of wax. "Please," his godson begged, "for many years I was your faithful servant. Please, Godfather Death, won't you light a new candle for me?" Death gazed at him remorselessly. The candle sputtered and flickered out. The young doctor fell down dead.

This story, titled Godfather Death, comes from the German folk tales of the Brothers Grimm. It can also be found in variant forms in a number of other countries as well -- such as The Shepherd and the Three Diseases from Greece, The Just Man from Italy, The Soul-Taking Angel from Armenia, The Contract with Azrael from Egypt, Dr. Urssenbeck from Austria, and The Boy With the Keg of Ale from Norway. It's one of a number of folk and fairy tales in which Death is personified: sometimes as a frightening figure, sometimes as a compassionate one, and sometimes as a matter-of-fact man or woman with a job to do.

There are many tales in which Death is out-witted, such as Jump In My Sack from Slovenia -- in which a young man pleases a powerful fairy who offers him two magic wishes. He asks for a sack which will suck in whatever he names, and a stick that will do all he asks. These wishes are granted, and the young man uses the sack to bring him meat and drink, until he comes to a great city and falls in with a group of gamblers. Death (or the Devil, in an Italian version of the tale) is among the gamblers in disguise, amusing himself at the gaming table by luring men to financial ruin and then collecting their souls when they are driven to suicide. The young man sees through Death's disguise. He orders the sack to suck Death up, then orders the stick to beat him soundly. At length Death begs for mercy, promising the young man whatever he wants. The young man asks for the restoration to life of all his gambling friends, and then orders Death to leave at once and to stay far away from him. But many years later, old and ill, he has second thoughts about this bargain. He now uses the sack to call Death back, and is grateful to be led away.

In a number of tales Death is outwitted and banished with dire consequences. The old, the ill, and the fatally wounded do not die, but linger in agony until finally the importance of Death's role can no longer be ignored. In a Spanish tale, an old woman traps Death in her pear tree and will not let him go until he promises to never come back. The woman's name is Tia Miseria (Aunt Misery), and as long as Death keeps his promise to her, we'll have misery in the world. In a similar tale from Portugal, Death outwits the old woman in the end -- but finds her so shrewish, he promptly brings her back to her house and flees.

Some tales feature a Godmother Death, such as versions of the stories told in Slovenia and Moravia, and across the sea in America's Appalachian Mountain region. The depiction of death as male or female depended on the culture, the times, and the storyteller, but examples of both are widely found in folk tales the world over. In Death and the Maiden, a story known in both folk tale and folk ballad form, the interaction of a male Death figure and the well-born young woman he's come to claim has an almost seductive quality. She tries to bargain for her life, offering up her gold and jewels, as he gently explains that she must go with him that very night. In some pictorial representations of the story, Death is portrayed as a knight clad in black; in others, more frighteningly, he is a skeleton in knightly clothes. (Franz Schubert drew on this tale for his lovely Quartet in D Minor: Death and the Maiden, composed in 1824.) In a Turkish fairy tale, The Prince Who Longed for Immortality, a male Death figure is pitted against the Queen of Immortality. They wager over who will get the hero by throwing him up in the air. In a story from northern Italy, Death is portrayed as a lovely young woman. She's an unwelcome guest in the palace when her true identity is revealed (as she takes the handsome young king away) ��� but a welcome guest in the cottage of a poor, old woman who's been waiting for her.

In early medieval representations, Death was usually masculine: powerful, pitiless, omnipresent. Clad in black, he was the Grim Reaper who cut men and women down in their prime, prince and poet and pauper alike. In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, we find more examples of Death as a woman ��� such as Donna La Morte in Petrarch's famous poem, "The Triumph of Death," who appears suddenly all "black, and in black" to claim the life of a young noblewoman. The Dance of Death (or Danse Macabre) first appeared in the middle of the 14th century as the Black Death ravaged its way across Europe. The Dance of Death originated in the form of a Christian spectacular play, performed in churchyards and cemeteries among charnel houses and graves. Death appeared here as masked, skeletal figures intent on leading away a series of victims (twenty-four in number) from all classes of society. The victims would protest, offering reasons why they and they alone should be spared, but in the end all are danced off to the grave while the fiddlers play. This was paired with sermons stressing that death could strike anyone at any time, exhorting the audience to prepare themselves and live free of sin.

In Italy in the following century, death spectacles were more elaborately staged. As Charles B. Herbermann and George Charles Williams describe them (in the Knight, Death, and the Devil."

My friend and colleague Midori Snyder is a writer who has worked with the folklore of death in several ways ( in her elegiac faery novel Hannah's Garden, her children's story "Jack Straw" [read it online here], and in a novel-in-progress based on an Italian fairy tale), so I asked her for her thoughts on the subject:

"There are many characters in folklore associated with death," Midori responded, "various death-announcers and death-dealers, but I would suggest that they are not actually Death figures, as in a Mr. or Ms. Death personified. Morrigan, the Irish goddess of War, for example, revels not only in the glory of war but also its violence and carnage: the taste of fear, the scent blood, the dying moments of warriors on the battlefield. Flying above the battle in the form of a black crow, she is a figure of Fate, like the Valyries of Norse myth, foretelling who will live and who will die...but she is not Death herself. The various incubi and succubi of European folk legend are death-dealers, in their actions are fatal to the luckless mortals who get tangled up with them...but they aren't Death, either. Their interest is in specific individuals (generally those who catch their sexual interest), whereas Death is an equal opportunity killer. Death takes the child, the adult, the old, the young, the strong, the weak. Death doesn't discriminate, but moves over everything in a constantly shifting, unpredictable pattern. That is what is so terrifying, the way death resists being slotted into a known plan. All we know is that it will happen -- but never when and never how. Tales such as Godfather Death, or the medieval Dance of Death, specifically addressed this idea and this terror -- as opposed to folklore's other death-dealing creatures, who select very specific victims. Edgar Allan Poe's frightening story 'Masque of the Red Death' plays with the idea that one imagines one can foretell and identify Death, and therefore keep him/her out. And what is chilling in the tale is the sheer ease with which Death infiltrates the masque with the rest of the revelers."

"I've also been thinking about the differences in those stories where the dead live in an alternate world to ours," Midori continues. "The Greek god of the Underworld, Hades, is not a Mr. Death figure, but, rather, he is the King of the Dead, content to rule over the souls who have come to him instead of going out and nabbing them himself. Likewise in the Christian tradition, where those who die are 'born to eternal life' in heaven or hell, Christ isn't a Mr. Death, and neither is Satan (especially if one thinks of Dante's image of him, frozen in a bed of ice), although both have something to say about dead souls in the afterlife.

"When we look at myth, specifically at that cycle of tales in which death is brought into the world (often by a bumbling Trickster figure), death is rarely personified. It moves like a force of nature, invisible and ubiquitous. Death happens. But in folk and fairy tales, death acquires a face, a figure, a point of consolidation -- which allows the protagonist of the tale, when confronted with his or her mortality, to recognize the moment at hand. The personified images of Mr. or Ms. Death are generally of the wanderer, the traveler, the one not bound by place or position. The very anonymity and flexibility of personified Death insures the equality with which death meets us all...high and low.

"Death is also a mirror reflection of ourselves. In medieval and Renaissance pictorial representations, Death often wears a tattered, mirror version of the clothes his victim wears. It is, after all, for each of us, our Death that we meet, no one else's. In the stories where he appears, Mr. Death is a reflection -- a concrete, externalized image of the protagonist's death. And therefore his/her appearance has something to say about the character whose death it is that has arrived. From the Grim Reaper of medieval legend to the elegant young stranger in Peter Beagle's story 'Come Lady Death' or the 'woman in white' in Bob Fose's All That Jazz, from Shiva with her voluptuous form and deadly arms to Johnny Depp in Jim Jarmusch's haunting film Dead Man, Death appears in a variety of guises but also functions differently as a narrative sign. Coyote's death in Trickster myths, for example, is experienced (and read) very differently than the death proffered by the skeletal knight who comes to take the Maiden away. The first is read as temporary, because Coyote always come back to life -- while the other is frighteningly permanent. The skeleton reflects what the Maiden will become. Indeed, what we'll all become."

Death is a frequent theme in fairy tales -- as well as the stark realities of death's aftermath, for many stories begin with the death of one or both of the hero's parents. Fairy tale historian Marina Warner points out that death in childbirth was far more common in centuries prior to our own and the prevalence of step-children and orphans in fairy tales reflected a social reality. Many of these tales (in their pre-Victorian forms) were exceedingly violent, including those gathered by the Brothers Grimm in editions published for German children. Though the Grimms are known to have edited their fairy tales with a rather heavy hand, stripping them of sensuality and moral ambiguity, they had no such qualms about leaving much of the worst violence intact. (Indeed, as scholar Maria Tatar has noted, in some stories they beefed it up.) Murder, cannibalism, and infanticide are staples of the fairy tale genre. From Bluebeard with his chamber of horrors to the goodwife in The Juniper Tree who decapitates her inconvenient step-son, death is a very real threat in the tales -- yet it does not always have the last word. In Fitcher's Bird (a Bluebeard variant), the heroine not only outwits the wizard who aims to marry then murder her, but she's able to bring the hacked-up bodies of her predecessors back to life. The step-son in The Juniper Tree returns to earth in the form of a bird. Cinderella's dead mother returns as a fish (in the oldest, Chinese version of the story), a cow (in a Scottish variant), or a tree (in the version found in Grimms), watching over her daughter and whispering wise words of advice.

Another good example is the story of Snow White. Our heroine is not merely sleeping but dead, in the early versions of her tale: displayed in a glass coffin, her form incorruptible, like a saint's. The necrophilic overtones of the story are most evident in a 16th century Italian version called The Crystal Casket. In this tale, the heroine is persuaded to introduce her teacher to her widowed father. Marriage ensues, but instead of gratitude, the teacher treats her step-daughter cruelly. An eagle helps the girl to escape and hides her in a palace of fairies. The step-mother then hires a witch, who sells poisoned sweetmeats to the girl. She eats one and dies. The fairies revive her. The witch strikes again, disguised as a tailoress with a beautiful dress to sell. When the dress is laced up, the girl falls down dead -- and this time the fairies will not revive her. (They're miffed that she keeps ignoring their warnings.) They place the girl's body in a fabulous casket, rope the casket to the back of a horse, and send it off to the royal city.

The casket is soon found by a prince, who falls in love with the beautiful "doll" and takes the body home with him. "But my son, she's dead!" protests his mother. The prince will not be parted from his treasure; he locks himself away in a tower with the girl, "consumed by love." Soon he is called away to battle, leaving the doll in the care of his mother. The queen ignores the macabre creature -- until a letter arrives warning her of the prince's impending return. Quickly she calls for her chambermaids and commands them to clean the neglected corpse. They do so, spilling water in their haste, badly staining the maiden's dress. The queen thinks quickly. "Take off the dress! We'll have another one made, and my son will never know." As they loosen the laces, the maiden returns to life, confused and alarmed. The queen hears her story with sympathy, dresses the girl in her own royal clothes, and then, oddly, hides the girl behind lock and key when the prince comes home. He immediately asks to see his "wife." (What on earth was he doing in that locked room?) "My son," says the queen, "the girl was dead. She smelled so badly that we buried her." He rages and weeps. The queen relents. The heroine is summoned, her story is told, and the two are now properly wed.

The casket is soon found by a prince, who falls in love with the beautiful "doll" and takes the body home with him. "But my son, she's dead!" protests his mother. The prince will not be parted from his treasure; he locks himself away in a tower with the girl, "consumed by love." Soon he is called away to battle, leaving the doll in the care of his mother. The queen ignores the macabre creature -- until a letter arrives warning her of the prince's impending return. Quickly she calls for her chambermaids and commands them to clean the neglected corpse. They do so, spilling water in their haste, badly staining the maiden's dress. The queen thinks quickly. "Take off the dress! We'll have another one made, and my son will never know." As they loosen the laces, the maiden returns to life, confused and alarmed. The queen hears her story with sympathy, dresses the girl in her own royal clothes, and then, oddly, hides the girl behind lock and key when the prince comes home. He immediately asks to see his "wife." (What on earth was he doing in that locked room?) "My son," says the queen, "the girl was dead. She smelled so badly that we buried her." He rages and weeps. The queen relents. The heroine is summoned, her story is told, and the two are now properly wed.

Author and fairy tale scholar Veronica Schanoes notes, "Many fairy tales and myths concern the fantasy that if you love someone enough, you can bring them back from the dead. In fairy tales, that effort is usually successful and the wish is fulfilled: Sleeping Beauty wakes up; Snow White revives; the older sisters in Fitcher's Bird are resuscitated; the heroine recovers her prince in East of the Sun, West of the Moon; etc. But in myth, the stories tend to be more poignantly about the limits of human love and its inability to defeat death: Gilgamesh can't bring back Enki; Achilles can't bring back Patroclus; Theseus cannot rescue Pirithous; Orpheus fails; and even though she is a goddess, Demeter's love for Persephone can only bring her back part-way."

The fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen often touch on the subject of death, but the ones that address the subject directly are among his most pious and sentimental, better suited to Victorian tastes than they are to ours today. One of the more interesting of them is The Story of a Mother, in which Death knocks on a woman's door and takes her beloved son away. The distraught woman determines to follow, and makes her long, weary way to Death's realm. There, she finds a greenhouse filled to the bursting with flowers and trees of all kinds -- each one representing a single life somewhere on earth. When Death arrives, she tricks him into giving back the life of her son -- but Death shows her the future and the terrible life her child will lead. She knows then that his death is god's will, and a mercy, and she is at peace.

Andersen's very best tale about death has deservedly become a classic. The Nightingale is the story of a Chinese Emperor and a bird with an exquisite song. The Emperor dotes on the bird for awhile, then replaces the humble, faithful creature with a golden mechanical replicate...until the night that Death comes for him, squatting heavily on his chest:

Opening his eyes he saw it was Death who sat there, wearing the Emperor's crown, handling the Emperor's gold sword, and carrying the Emperor's silk banner. Among the folds of the great velvet curtains there were strangely familiar faces. Some were horrible, others gentle and kind. They were the Emperor's deeds, good and bad, who came back to him now that Death sat on his heart.

"Don't you remember?" they whispered one after the other. "Don't you remember - ?" And they told him of things that made the cold sweat run on his forehead.

"No, I will not remember!" said the Emperor. "Music, music, sound the great drum of China lest I hear what they say!"

But nothing will drown out the whispers. The Emperor's mechanical bird sits silent, for there is no one to wind it up. Then the real nightingale arrives, having heard wind of the emperor's plight. He sings so beautifully that the phantoms fade and even Death stops to listen. The nightingale bargains for the emperor's life, and Death departs.

Death underlines the magical stories that make up The Arabian Nights, for it is the reason Scheherazade spins her tales: to save herself and her sister. "There's something almost Trickster-ish about Scheherazade," Midori points out. "She uses storytelling to keep death at bay -- but she does so by never finishing the tale in the morning, where its conclusion might signal the arrival of her own promised death. Instead, she leaves off at a cliffhanger, which requires yet another night to finish -- and then promptly starts another tale before the night is over. The moment of completion (the rehearsal of 'death') does come -- but in the middle of the night, which enables her to resurrect herself in another tale before the sun rises. So it's as though each story produces its own moment of death, followed by a new work that resurrects the storyteller. It's like trickster's death in the Coyote stories, a death that is never final. He's always returning, repeating a movement between death and creation."

It fairy tales, too, death is not always final; it's sometimes an agent of change and transformation. Sleeping Beauty in her death-like sleep, Snow White in her glass coffin: this is a mere rehearsal for death, and out of it new life is created (literally, in the case of Sleeping Beauty, who gives birth to twins as she lies asleep and wakes as they try to suckle). In Trickster myths, the connection between death and life, destruction and creation, is usually made clear; but in fairy tales too, death is not always an ending, or at least not just an ending. It can have within it the seeds of new life, of change, of transformation ��� which is what these tales, at their most basic level, are so often all about.

"Death in folklore, when not associated with the more violent sorts of death-dealers, is generally rather ambiguous," Midori concludes, "which is of course the nature of death itself. At some point we must accept and embrace it, because it is the fate of us all -- yet we resist it (at least at certain times in our lives) because of its finality. Death figures in folk and fairy tales allow us to personalize our contact with death long enough to confront it, to argue with it, to pit our wits against it . . . and perhaps, if we are lucky, to finally make peace with it."

This is fertile ground for fantasy writers, some of whom have already made good use of it: Ursula K. Le Guin in The Farthest Shore, Jane Yolen in Cards of Grief, Rachel Pollack in Godmother Night, Neil Gaiman in his Sandman comics, etc.. But there's still much territory to explore as the fantasy genre ages and matures... and as we fantasy writers and artists age and mature along with it.

****

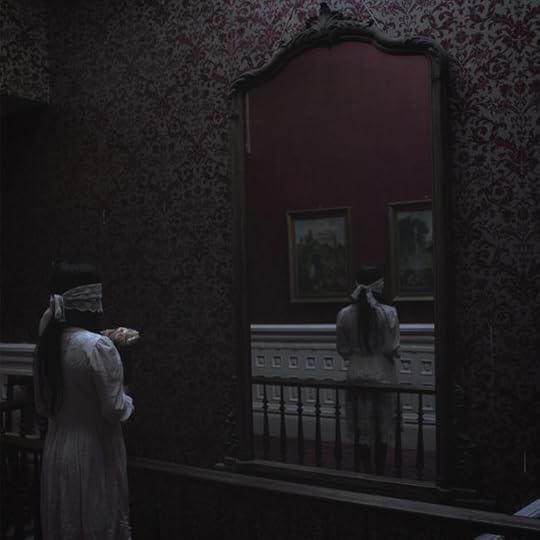

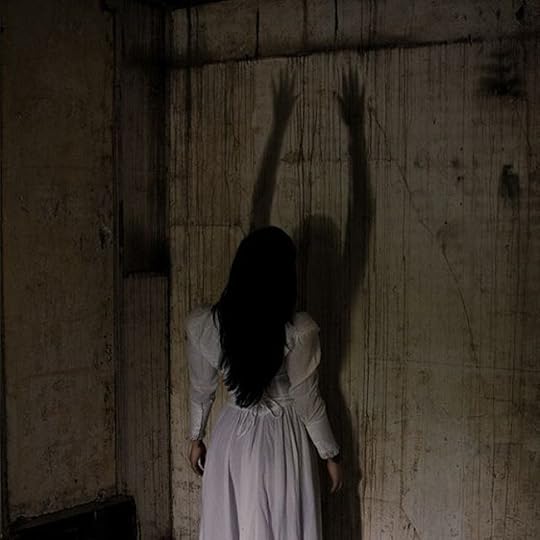

The marvelously macabre photographs today are by the American photographer Daniel Vazquez, who lives and works in the Bay Area of California. Please visit his "American Ghoul" website and Instagram page to see more of his stunning work.

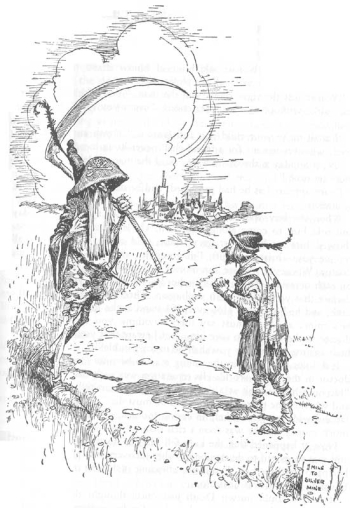

The photographs above are by Daniel Vazquez. The illustrations are: "Godfather Death" by Johnny B. Gruelle (1880-1938) and the Death tarot card by Pamela Colman Smith (1878-1951). All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artists and authors. Many thanks to Midori Snyder for her contribitions to this essay.

Further reading: John O'Donohue on death traditions in Ireland, Stu Jenks on the annual Day of Dead procession in Tucson, and Katherine Langrish on death in fantasy literature.

October 31, 2019

Happy Halloween from Myth & Moor

Here in Chagford, it is shaping up to be a foggy and wet Halloween ... but no doubt there will be little witches, ghosts and ghouls at the door this evening anyway, so the hound and I are ready.

Some magical reading for the season:

* At the Death of the Year: the folklore of Halloween, Samhain, and the Days of the Dead

* Twilight Tales: on those times and places when the borders between world grow thin

And some magical listening:

* Phantasmagoria: Folk songs of ghosts, spirits, and hauntings by Tamsin Rosewell.

Tilly is being a Fool for Halloween, to support her papa's Funding for Foolery campaign. She's very earnest and serious about it, so I'm not sure she quite understands what a Fool actually is ... but her heart is in the right place, bless her.

The Wild Time of the Sickbed

This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in the spring of 2018. It's a follow-up to yesterday's piece on illness, art, and work/life balance; and it too is re-posted by request....

As those who also have medical issues can concur, it's not just the large, dramatic things (surgery, chemo, and the like) that disrupt our schedules and overturn our plans, it's often the small things too: the side-effects of a medication, for example; or the body's shock after an invasive test; or a simple virus making the rounds, knocking others out for a couple of days while knocking us out for a couple of months. Illness takes time, and time for artists is a crucial resource. Writing, editing, or illustrating a book, for example, takes hours and hours of focused attention; and whenever we are knocked from the ladder of health, it feels like our time has been stolen.

Yet the loss is not really of time itself, but of one particular form of it: the "productive" time prized in our commerical culture, which priviliges results and finished products over process. "Time is money," as the old saying goes, and a sick person's time is not worth a bad penny. Yet paradoxically, when we're in poor health we are often rich in time, but in the wrong kind of time: the "unproductive" time of the sickbed. After a lifetime lived in the liminal space between disability and good health, I have come to believe "unproductive" time has its place and its value as well.

The business world operates on a linear concept time, structured in regular working hours, measured by schedules, spreadsheets, targets; products made, marketed, and sold. Art-making is not a linear process, but those of us who work in the arts professions do our damn best to pretend that it is: writing books to deadline, making film or theatre to schedule, etc., while walking a precarious tightrope stretched between the muse and the marketplace. It's not an easy balance, but we do it. We live in a market culture, after all, and daily life jogs along by its rules. But illness cares nothing for markets; we do not heal in a linear fashion; and the common symptoms of failing health (the brain-fog, fatigue, and fevers of a body engaged with repairing itself) are at odds with the fast and furious pace of an industrialized, digitalized world.

Time, during an illness, slows and meanders: we sleep and wake, sink and rise, drift through the days absorbed in the mysteries of the body -- its fluids and fevers, its terrors and comforts, its cycles of pain and merciful release -- while our colleagues rush past in a bright busy world that seems far removed and unreal.

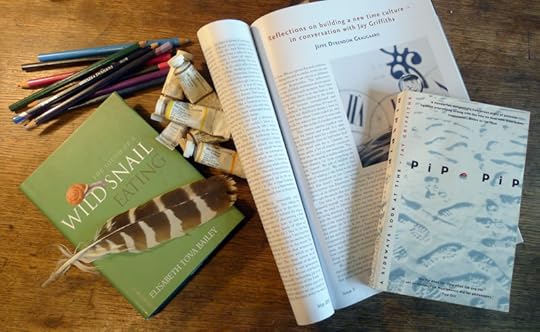

In her poetic memoir of illness, The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating, Elizabeth Tova Bailey reflects on the time she spent bedridden with a semi-paralysing auto-immune disease:

"The mountain of things I felt I needed to do reached the moon, yet there was little I could do about anything and time continued to drag me along its path. We are all hostages of time. We each have the same number of minutes and hours to live within a day, yet to me it didn't feel equally doled out. My illness brought me such an abundance of time that time was nearly all I had. My friends had so little time that I often wished I could give them what I could not use. It was perplexing how in losing health I had gained something so coveted but to so little purpose."

I sympathize with Bailey's despair about the "mountain of things" she suddenly could not do, (I've often felt the same), but I resist defining the slowed-down time of the sickbed as time that has no use. There are many modes of experiencing the world, and linear time is just one of them. During illness, I enter a different mode: slower, stranger, cyclical, tidal. Attuned to the immediate environment. I see it as a form of Wild Time, a term coin by cultural historian Jay Griffiths (in her excellent book on time, Pip Pip) -- defined as time that's not been dictated by modern industrial cultural norms; time rooted in the body, the land, the ebb and flow of sea and psyche.

It is always hard to remember the exact qualities of time experienced in the sickbed when we're back in the flow of the linear world; it blurs around the edges, bright and elusive as a fever dream. What I recall best about the strange Otherworld I enter whenever my body fails is how the world shrinks to the size of my bedroom, to the dimensions of a bed littered with books, and to a window view of the garden, the hill, and the oaks at the woodland's edge. Unable to summon the focused attention required to write, paint, or simply communicate, I surrender to those things that illness allows and facilitates: Reading, deeply and widely. Watching the natural world through window glass. Thinking the kind of thoughts that rise, for me, only in stillness and isolation.

Illness prevents me from being active. From climbing the hill up to my studio and re-engaging with the work I've left undone. But the art that I make in "productive" time is informed by the things I feel (and watch, hear, read, reflect on) during the slow, strange hours of fever and pain. Both aspects of life -- the busy studio, the quiet sickbed -- combine to make me the artist that I am.

Writing in EarthLines magazine in 2013, Deppe Dyrendom Graugaard described a conversation with musician and philosopher Morten Svenstrup about time in relation to nature and art -- reflecting on the way that time slows down when we are fully engaged in listening to music, looking at a painting, reading a book ... or, I'd add, communing with the body during the slow sensory days of an illness.

"Around the time this conversation took off, Morten was writing his thesis Time, Art, and Society, in which he explores the insight that when we engage with an artwork, we pay attention in a way we don't always do with other objects. The composition of an art piece, its inherent timing, cannot be forced to fit whatever our personal sense of time may be. Being a cellist, he was very aware that if we want to really engage with music, we have to surrender our immediate sense of time and listen. The question arose: what happens if we take the kind of attention we bring to bear on a painting, a symphony, or a poem into our everyday surroundings and listen to the inherent time of our neighbourhood, a nearby woodland, or our own bodies?

"Doing this, we encounter an astonishing diversity of timescales which make a mockery of the idea that there is such a thing as a singular, universal, abstract Time. The present is made up of a multiplicity of lifetimes, and getting past our personal view and tuning into what can best be described as a symphonic view of time, we immediately acquire the sense of the richness of life. By sidestepping our notion of time as something outside ourselves and independent of us, we see that everything has its own time, an Eigenzeit. This can work as an antidote to the speed that marks a society driven by principles of efficiency and growth. It is a practice which begins with noticing the world around us, paying attention and becoming present -- but which leads to a deeper understanding and connection with the places we inhabit."

Graugaard notes that an unrushed relationship with time is valuable in a digital age which constantly fractures our powers of concentration, and explains why cultivating Wild Time is a radical act.

"Wresting our attention from the flurry of information that is hurtled at us through fibre-optic communication and turning it toward the depth of time is not just about engaging new ways of seeing and honing the lifeskills we need to live fully in the context of a digitalized world. It is also a way of finding joy in the places we live in, whether they are urban or rural. Surrendering and accepting what is, and figuring out what we want to hold onto and what we can let go of. Without attention we are lost. Whatever distracts attention kills our potential to be free.

"This is why resisting the progressive notion of time as linear, singular, and above all placeless is profoundly political. It is about power. Tuning into the timescapes of the other allows us to dissolve the separation that modern life requires from us. That is what is meant by the beautiful metaphor of 'thinking like a mountain.' By thinking like a mountain, we open the possibility of becoming other."

There are many ways we can "think like a mountain" and pull ourselves from the frantic pace of the mechanized world into periods of soul-enriching (perhaps even soul-saving) Wild Time. We can take breaks from the Internet, for example; or immerse ourselves in nature; or cultivate "deep attention" by making art and engaging with art. And although it's not a method most of us would choose, illness, too, allows us to surrender to time in a slower, wilder way, thereby fostering a deeper, richer connection to the physical world we live in.

Don't get me wrong, I prefer good health. I prefer to be energetic and active. But during those times when I'm back in bed again, too weak, too tired, too pain-raddled to keep up with the friends and colleagues racing ahead on time's straight track, I am learning to accept that mine's a slower, more meandering trail. But it has its value. It has its use. It will get me where I want to go.

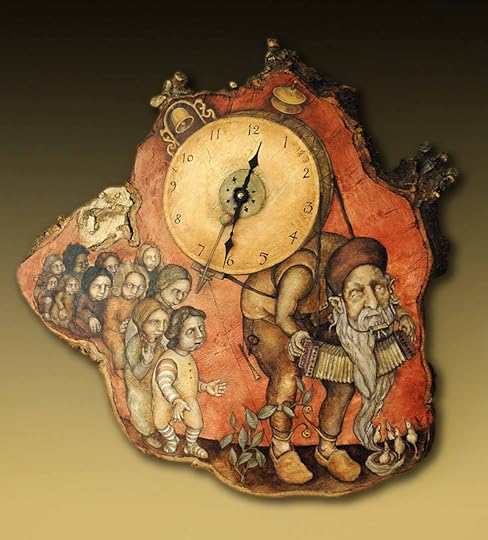

About the art:

The wonderful painted clocks in this post are by my friend and Dartmoor neighbour Rima Staines, a multi-disciplinary artist who uses paint, wood, word, music, animation, puppetry, and story to "build a gate through the hedge that grows along the boundary between this world and that." Born in London to a family of artists, and raised on the roads of Bavaria in her early years, Rima has always been stubborn about living the things that make her heart sing.

With her partner Tom Hirons, Rima also runs the Hedgespoken folk arts project. For part of the year, they travel the lanes and byways of Britain in a glorious old truck converted into an off-grid venue for storytelling, folk theatre, and puppetry. In the winter months, they return to us on Dartmoor and focus on writing, painting, and running Hedgespoken Press.

Rima���s inspirations include the world and language of folk tales, folk music, folk art of Old Europe and beyond, peasant and nomadic living, wilderness, plant-lore, magics of every feather, and the beauty to be found in otherness. To see more of her extraordinary work, visit her website: Paintings in a Minor Key, her blog: The Hermitage, and seek out her book, Tatterdemalion, co-created with Sylvia V. Linsteadt.

The clock paintings above are by Rima Staines (the charming titles are in the picture captions - run your cursor over the pictures to read them); and all rights are reserved by artist. The drawing of Alice's White Rabbit checking his pocket watch ("Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be too late!") is by John Tenniel (1820-1940).

The passages quoted above are from The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elizabeth Tova Bailey (Algonquin Books, 2010), and Deppe Dyrendom Graugaard's introduction to an interview with Jay Griffiths (EarthLines magazine, 2013). I highly recommend Jay Griffith's book Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time (Flamingo, 1999). All rights reserved by the authors.

A few related posts on illness, and on time: In a Dark Wood, Stories are Medicine, The Subtle Element of Time, and Wild Time & Storytelling.

October 30, 2019

Attention animal lovers

My smart, talented, adventurous and big-hearted goddaughter Ely Todd-Jones is raising funds in order to go volunteer at the Elephant Nature Park in Thailand, which is one of the most respected animal rescue & rehabilitation centers in Southeast Asia. Would you consider lending your support -- either through a contribution (no matter how small), or by spreading the word of the campaign?

There's more information here on Ely's fund-raising page.

Elephants are magnificent creatures, and their numbers are diminishing due the stress of sharing the planet with us. Ely, who grew up here in Chagford, is pretty magnificent too. Next year she will head to university to study biology and animal communication -- but until then she is devoting her time to wildlife and re-wilding projects.

I am in awe of the work that young people are doing to save our world from environmental catastrophe, but they need our support...and so do the elephants.

Images: An illustration from Aesops Fables by Arthur Rackham, and a young elephant sleeping at the Elephant Nature Park.

October 29, 2019

On blogging (and spoons)

This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2011. It's re-posted today by request....

During a recent interview, my friend Rima Staines discussed the art of blogging: how she started, and why she started, at a time when personal blogs like hers (The Hermitage) were still new and unusual. "What a strange and cumbersome word 'blogging' is," she said, "but I like where it comes from: a web log, like a ship's log. You can perhaps imagine us all pegging log entries onto a huge web for the general perusal of spiders everywhere. My reasons for blogging? They touch upon connection, friendship, and the sharing of delights. Sharing art and ideas online has become a vital part of the work of so many self-employed artists and craftspeople, and I would not now be lucky enough to spend my days painting for a living without the connections I made through The Hermitage."

Reading Rima's interview has led me to think about why I blog myself (here on Myth & Moor since 2008, and prior to that for The Journal of Mythic Arts). The thread of my thoughts about blogging is all knotted up with a number of other things that I've been pondering lately -- about art, and life, and energy, and "spoons" -- and out of this tangle there's something specific I want to unravel -- but I'm going to have to tease it out slowly from the snarl of other threads, so please bear with me.

This is also going to be a more personal post than usual for me, since one of those threads involves chronic illness, and that's a subject that I approach gingerly. Writing frankly about coping with illness can be mistaken for a plea for sympathy ("Oh, poor, poor me!"), or as a means of defining oneself as part of an aggrieved minority ("Sick people don't get no respect!") rather than what it actually is: a creative/intellectual attempt to understand the process of living in a malfunctioning body while also living as a creative artist. So I hereby give notice that I am about to tread further than usual into this murky territory today ... and perhaps in speaking of the personal, I can find my way back to more general thoughts about living the Artist's Life; or, at very least, give voice to issues that others dealing with illness might find familiar, or useful.

First let me define my terms. I'm going to refer to the limited energy one has when dealing with a chronic illness in terms of "spoons" -- so if you haven't yet read Christine Miserandino's very useful "Spoon Theory" essay, it might be helpful to do so. And by the term "blogging," I'll be referring specifically to the writing of personal blogs, rather than all of the other sorts: professional, political, commercial, multi-author, et cetera.

First let me define my terms. I'm going to refer to the limited energy one has when dealing with a chronic illness in terms of "spoons" -- so if you haven't yet read Christine Miserandino's very useful "Spoon Theory" essay, it might be helpful to do so. And by the term "blogging," I'll be referring specifically to the writing of personal blogs, rather than all of the other sorts: professional, political, commercial, multi-author, et cetera.

With Rima's words running through my head, I was walking in the woods with my dog earlier (where I ran, quite unexpectedly, into Brian Froud and his dog, but that's another story), thinking about the "art of the blog," and why, after a somewhat trepidatious beginning, I find it so congenial. I'm in a different stage of my life and career than Rima, and thus my answer to the question "Why write a blog?" is bound to be a different one from hers, or any other young artist's. The answer that appeared to me suddenly as I trudged up the hill through the mud and leaves came from an unexpected direction. It has to do with dodgy health and spoons and the thorny issue of communication.

Now, I can't speak for everyone with a serious and/or long-term illness, and my own (which I prefer not to name in this public space) affects daily life in ways that may differ from other medical conditions -- but what many of us with a range of health issues share is a constant need to juggle whatever spoons we have to hand on any given day. And for me, the simple act of communication is one that consistently threatens to empty my spoon drawer.

Perhaps it's because I communicate for a living, and therefore the spoons specifically shaped for that job are ones I particularly have to hoard in order to meet the daily demands of my work. All I know is that the simple act of writing a letter to a friend, or answering an email, or (especially) picking up the phone are entirely beyond me when those spoons are used up ��� and they're precisely the spoons I tend to run out of first, due to the nature of my work.

This is an aspect of my life that constantly frustrates my dear, patient, long-suffering family members and friends. I drop out of sight, I don't pick up the phone, emails drop into some kind of cosmic black hole. I'm warm and engaged and present on a good day, and retreat into mumbles and chilly distance on a bad one. Sometime I'm a reliable friend/sister/niece/co-worker, and a regular part of others' daily lives ... and sometimes I disappear for days, weeks, months on end with no warning at all. If I were a hermit by nature, none of this would be a problem, but I'm not -- I'm a person with a wide, deep circle of close relationships; an artist who thrives on connection and community; a sociable woman whose natural rhythms are often disrupted by the over-riding rhythms of illness.

What has all this to do with blogging, you ask? It is this: Writing short pieces for a more-or-less daily blog is, for me, a means of communication, of maintaining vital connections: with friends, with colleagues in the publishing field, with the wider Mythic Arts community. Yes, it takes spoons, but not many of them (now that I'm comfortable enough with the form and technology that I can put up a daily post reasonably quickly) -- and when compared to the number of spoons it would take to stay in frequent touch with the many people I know and love, to answer every email and return every call, those couple of spoons become negligible and well worth the cost. Blogging, for me, is my daily missive from the trenches of my creative life to the people, near and far, who make up my world. It's a form of round-robin letter to say: this is what I'm doing, this is what I'm thinking, I haven't disappeared. I may not be entirely well, but I'm still here. And if other people whom I've never personally met are reading these missives too, well then that's fine by me. I assume they're here because they also love books and folklore and mythic arts, and that means they're not really strangers, they are part of my wider community too.

Now here's where I'd like to see if I can make the leap from personal circumstance to something that might relate to other artists as well, beyond the small subgroup of folks also coping with illness or disability. It's almost always difficult for artists in any field (except, perhaps, for a very privileged few) to balance the time required by creative work with all the other demands of life. The need to manage ones time and energy may be more extreme and urgent for the chronically ill, yet I know few writers or artists (heck, do I know any?) who don't wrestle with the details of work/life balance. If it's not medical issues taking up ones time, it might be children, or elderly relatives, or a day job, or community obligations, or all of these things at once. The sheer busyness of modern life can feel relentless and overwhelming ... and that, in turn, conflicts with art's requirement for time, solitude, and periods of sustained, uninterrupted concentration.

I think that even if illness was suddenly, blessedly removed as a factor in my life, I would still be at this same point in my journey: having reached an age that forces recognition that time is not infinite, I feel compelled to turn inward and focus my time and attention on truly mastering my craft. The social gregariousness of youth is no longer possible, or desirable; there are only so many hours in the day, after all. And yet, the life- and art-sustaining web of connection begun in ones early years remains important even as one grows older, slower, and more protective of ones time. That, for me, is where blogging comes in. It maintains that web of connection.

I think that even if illness was suddenly, blessedly removed as a factor in my life, I would still be at this same point in my journey: having reached an age that forces recognition that time is not infinite, I feel compelled to turn inward and focus my time and attention on truly mastering my craft. The social gregariousness of youth is no longer possible, or desirable; there are only so many hours in the day, after all. And yet, the life- and art-sustaining web of connection begun in ones early years remains important even as one grows older, slower, and more protective of ones time. That, for me, is where blogging comes in. It maintains that web of connection.

Here's what blogging is to me: It's a modern form of the old Victorian custom of being "At Home" to visitors on a certain day of the week; it's an Open House during which friends and colleagues know they are welcome to stop by. I'm ���At Home��� each morning when I put up at post. Here, in the gossamer world of the Internet, I throw my studio door open to friends and family and strangers alike. And each Comment posted is a visiting card left behind by those who have crossed my doorstep.

But it's important to remember that the flip side of the Victorian "At Home" day is that it also provided boundaries -- for it was widely understood that visitors were not to drop by on other days of the week. Visitors could leave their calling cards with the butler, but the Mistress of the house was not instantly available to them. Like every artist (and particularly artists deficient in health and energy), I too need large periods of time when I'm simply not available to others: when I'm working, or resting, or off at the doctor's, or re-charging my creative batteries, or working out thorny plot problems while roaming the countryside with the hound. In these days of speed and instant access, of Facebook and tweets and 8-year-olds with their own mobile phones, it's almost a revolutionary act to say: I'm not in to callers. You can't reach me now. And yet artists need this. We need to unplug. We need to spend time in the world of our imaginations, where the Internet, texts, and apps cannot go.

But here's what I find interesting: The very same technology that threatens to force constant communication upon us can also be the thing that allows us to create necessary boundaries. Blogging, for all its intimacy as an art form, is also an excellent boundary maker. Yes, we open up our lives on a personal blog ... but only this much, not that much, and each blogger decides where that line will be drawn. The blog is a controlled kind of publication. It doesn't provided instant access to its maker, unless the blog's author specifically wants it to. The open, generous space cultivated on a blog need not (indeed, probably should not) be duplicated in the physical world; for in the world, what a working artist truly needs is the equivalent of the butler at the door, politely turning callers away: The mistress is not 'At Home' today. She is working. I will tell her you called.

This, then, is why I write a blog: not for the reasons so many young artists do (as they build their careers and find their audience), but because, as an older artist, it helps resolve one of life's central conflicts: that both illness and art demand solitude, yet the heart requires communication and connection.

I am also a woman woefully short on spoons and at this point in life I have learned to accept it. (Okay, my husband would say that I am learning to accept it.) Calls will continue to go unanswered. Emails will routinely begin with the words: Please forgive me for taking so long to respond. Friends will continue to worry when they haven't heard from me for a week, or a month. But these days, at least, they know they can always find me here at Myth & Moor ... with fresh coffee brewing, Tilly at my side, a pen or paintbrush in my hands ....

In the physical world, my studio is my work space, not a social space, and a four-footed butler stands guard at the door. But here, in my online studio, I am "At Home." And everyone is welcome in.

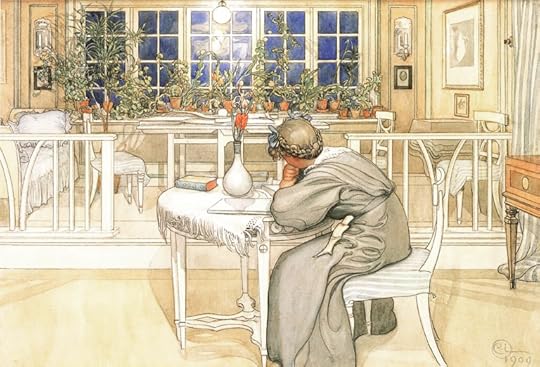

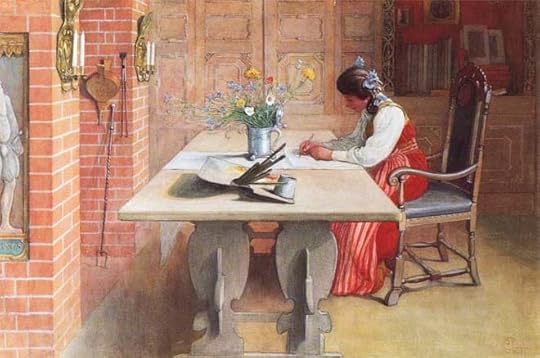

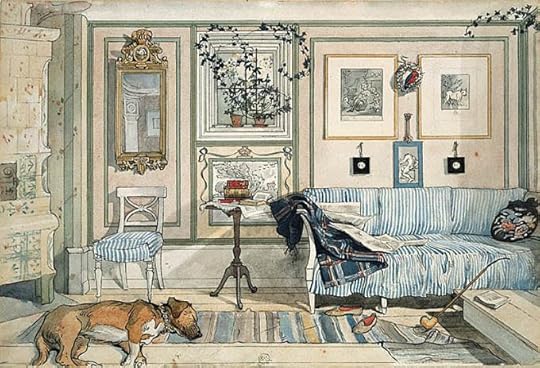

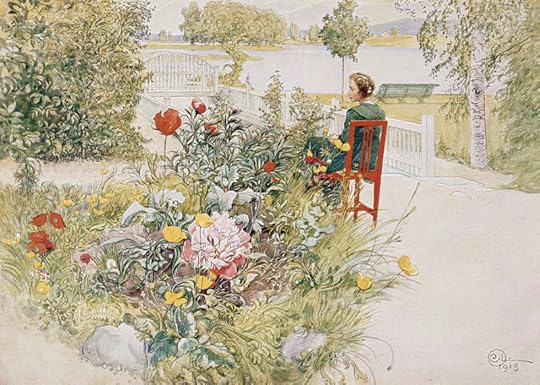

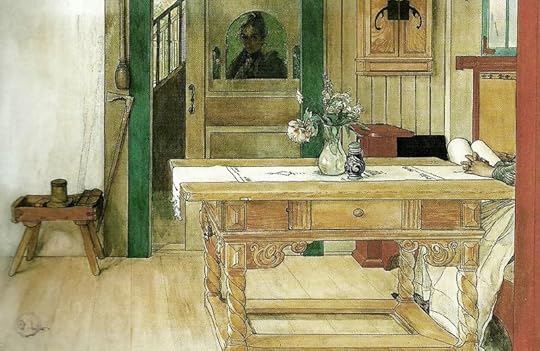

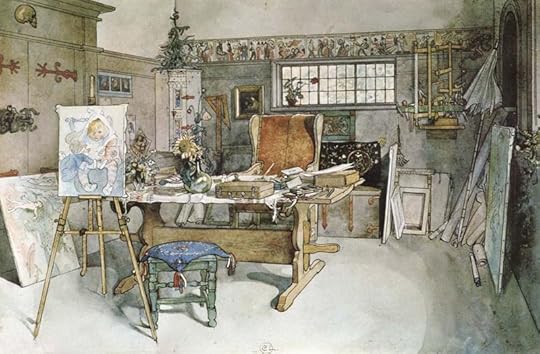

The paintings above are by the Swedish painter Carl Larsson (1854-1919). The poem in the picture captions is "After Illness, Walking the Dog" by Jane Kenyon (1947-1995), from Poetry Magazine (Oct/Nov 1987). Kenyon was New Hampshire's Poet Laureate when she died from leukemia at age 48.

This post is dedicated to Midori Snyder, who talked me into creating this blog. I owe you big time, old friend.

Tunes for a Tuesday Morning

My week is starting a little late due to health issues, but I'm back in the studio again on quiet, grey, melancholy day. Tilly is dozing at my feet, a squirrel is peering at us through the window glass, and the hills are turning yellow and gold as the days grow steadily colder.

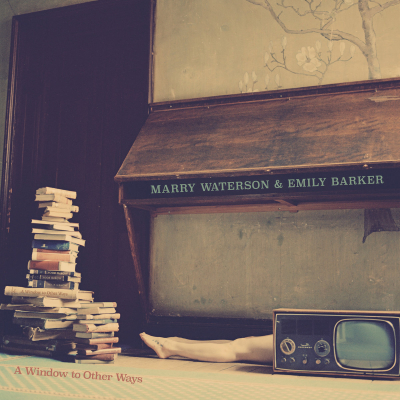

On Sunday night, I was lucky enough to see my Modern Fairies colleague Marry Waterson perform with Emily Barker in an old Devon church (accompanied by Lukas Drinkwater and Rob Pemberton), so I'm focusing on their music today. "Having met on a writing retreat," writes Neil Spencer, "it is perhaps no surprise that England���s Marry Waterson and Australia���s Emily Barker found their voices made a harmonious fit. Both women have a history of collaborative projects. That their respective personae also gelled was more unexpected. Waterson, a scion of Yorkshire���s Waterson-Carthy dynasty, sings much like her late mother Lal; stoicism and lowering northern skies are never far away. By contrast, Barker has inclined to upbeat Americana; her last album, Sweet Kind of Blue, recorded in Memphis, bristles with soul and country influences. Together, the pair have cooked up a dozen songs that blend light and dark, helped by the cello parts of producer Adem Ilhan, encountered at the same retreat."

On Sunday night, I was lucky enough to see my Modern Fairies colleague Marry Waterson perform with Emily Barker in an old Devon church (accompanied by Lukas Drinkwater and Rob Pemberton), so I'm focusing on their music today. "Having met on a writing retreat," writes Neil Spencer, "it is perhaps no surprise that England���s Marry Waterson and Australia���s Emily Barker found their voices made a harmonious fit. Both women have a history of collaborative projects. That their respective personae also gelled was more unexpected. Waterson, a scion of Yorkshire���s Waterson-Carthy dynasty, sings much like her late mother Lal; stoicism and lowering northern skies are never far away. By contrast, Barker has inclined to upbeat Americana; her last album, Sweet Kind of Blue, recorded in Memphis, bristles with soul and country influences. Together, the pair have cooked up a dozen songs that blend light and dark, helped by the cello parts of producer Adem Ilhan, encountered at the same retreat."

In the video above, Marry and Emily perform four original songs -- "Be Good," "Twister," "I���m Drawn," and "Perfect Needs" -- for Pirate Live (2018). All of the songs can be found on their wonderful new album, A Window to Other Ways.

Below, Marry and guitarist David A. Jaycock perform their beautiful song "Two Wolves," from the album of the same name (2015).

Above: "Lord I Want an Exit" by Emily, recorded for The Toerag Sessions (2015).

Below: "Some Old Salty" by Marry's late mother, Lal Waterson, from her album Once in a Blue Moon (with Marry's brother, Oliver Knight). Marry, Emily, Lukas, and Rob sang this one acapella on Sunday night to close their set, and it was so gorgeous my heart was in my throat.

The wolf photographs are from the Wolf Conservation Center, an educational foundation and wolf refuge in South Salem, New York. For more information, go here. For wolves in folklore, fairy tales, and fantasy, go here.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers