Terri Windling's Blog, page 51

October 16, 2019

On Illness: In a Dark Wood

For this week's Folklore Thursday theme of the mythic Underworld, here's a piece on illness as a journey in the dark....

"In the mid-path of my life, I woke to find myself in a dark wood," wrote Dante in The Divine Comedy, marking the start of a quest that will lead to transformation and redemption. Likewise, a journey through the dark of the woods is a common motif in fairy tales: young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach their destiny; or they find themselves abandoned there, cast off and left for dead. The road is long and treacherous, prowled by ghosts, ghouls, wicked witches, wolves, and the more malign sorts of faeries....but helpers also appear on the path: wise crones, good faeries, and animal guides, often cloaked in unlikely disguise. The hero's task is to tell friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

In older myths, the dark road leads downward into the Underworld, where Persephone is carried off by Hades, much against her will, and Ishtar descends of her own accord to beat at the gates of Hell. This road of darkness lies to the West, according to Native American myth, and each of us must travel it at some point in our lives. The western road is one of trials, ordeals, disasters and abrupt life changes -- yet a road to be honored, nevertheless, as the road on which wisdom is gained. James Hillman, whose theory of "archetypal psychology" drew extensively on Greco-Roman myth, echoed this belief when he argued that darkness is vital at certain periods of life, questioning our modern tendency to equate mental health with happiness. It is in the Underworld, he reminds us, that seeds germinate and prepare for spring. Myths of descent and rebirth connect the soul's cycles to those of nature.

Having spent significant periods of my life in the muffled Underworld of physical disability, tales of the dark wood and myths of descent have a particular resonance for me, of course; but all of us enter the deep dark forest at some point in life or another, and such stories have much to tell us of how to find our way through; not unscathed, but transformed.

In an earlier age, a medicine man, shaman, or herb-wife consulted when my health problems first resurfaced this summer might have told me a story like this one, from the northern mountains of Mexico:

There was a young girl who married an old, old man, who used her ill. He worked her hard, beat her, starved her, and cast her off when she gave him no children, leaving her in the desert with no food, or water, or shelter. The young wife hid in the meager shade of rocks by day when the sun was fierce. By night she walked, crying, for she could not find her way home. The nights were cold. Wolves prowled the hills and carrion birds followed after her. She was hungry, thirsty, weary, and she walked till she could go no further. Lying down by a wide, dry wash, she wrapped herself in her long white skirt. She said, "Let La Huesera (the Bone Woman) take me, for I am spent." She died. Wild animals ate her flesh. Her spirit watched over the white, white bones and knew neither sorrow nor fear.

The bones lay in that secret place until the moon was full once more. And then La Huesera came and put them all in her woven sack. The old woman took the bones up to her cave high in the mountaintops, then laid them out beside her fire. She sat and smoked. She smoked and thought. She smoked and she thought for a long, long time, and then she began to sing.

"Flesh to bone! Flesh to bone! Flesh  to bone!" the Bone Woman sang, and before too long the bones knit back together, covered in flesh. Where the girl had once been red and rough, now she was soft and smooth and plump. Her skin was as gold as daylight and her hair as black as night. La Huesera sang and sang. She blew a puff of tobacco smoke. The young woman's eyes flew opened and she sat up and looked around her.

to bone!" the Bone Woman sang, and before too long the bones knit back together, covered in flesh. Where the girl had once been red and rough, now she was soft and smooth and plump. Her skin was as gold as daylight and her hair as black as night. La Huesera sang and sang. She blew a puff of tobacco smoke. The young woman's eyes flew opened and she sat up and looked around her.

The cave was empty. The ashes were cold. The old Bone Woman had disappeared. All that was left were tobacco seeds and she put them in her pocket.

She left the cave and started for home, following the rising sun. She knew she'd find her village walking this way, and so she did. She came upon her dwelling at last. The place was dark, deserted now. "That old man has died, that poor wife has died, come away from that place," the people said, for they did not recognize the lovely young woman who came to them out of the west. They gave her a name, a fine set of clothes, a new dwelling place, a goat, and a hen. They taught her human speech, for she had forgotten all that she knew. She planted La Huesera's seeds and tended the new plants carefully. In time, she married, and gave her young husband many gold���skinned daughters and black���haired sons, and her children's children's children still grow tobacco in that village today.

There are different versions of this basic story found in cultures the world over, particularly among the oral tales associated with healing rites. In the literal way we approach old folk and fairy tales in our modern world, it might seem just a simple "where tobacco comes from" story, or even a Cinderella variant: a mistreated girl is made beautiful, marries, and lives happily ever after. (I can picture the Disney version, complete with a singing-and-dancing La Huesera.) My gentle husband is not an abusive one, and I certainly didn't come through a summer of illness with sudden supernatural beauty. So why would this tale apply to my recent journey through the dark woods of illness?

Let's look at the tale again, as an ancient curandera (healer) might look.

It doesn't really matter how the girl came to find herself in the desert -- the Mexican equivalent of the mythic greenwood -- for any life change or calamity can trigger events that lead into the dark: Hansel & Gretel's parents abandon them there, Beauty takes her father's place in it, Donkeyskin chooses the dark unknown to  escape a more dreadful fate. The point is that our hero is there, alone, walking by night, miserable, in extremis, removed from the normal rhythms of life...and thus ripe for transformation. It is in the darkest hour of need that the guardian figures in folk tales appear, waiting by the side of the road as the hero stumbles by. In this case, our guide waits long indeed -- she waits until the hero is dead. (It is notable that as the young woman surrenders to her fate, all fear and sorrow leave her.) Like the hideous crones who are faery godmothers in disguise, La Huesera, scavenger of bones, is salvation cloaked in an unlikely form. The old woman carries the bones to a cave in the west, the place of the dead. Dead to her old life, if not to the world, the girl's spirit lingers, watches, and waits. Her patience is rewarded as her broken body is fashioned anew.

escape a more dreadful fate. The point is that our hero is there, alone, walking by night, miserable, in extremis, removed from the normal rhythms of life...and thus ripe for transformation. It is in the darkest hour of need that the guardian figures in folk tales appear, waiting by the side of the road as the hero stumbles by. In this case, our guide waits long indeed -- she waits until the hero is dead. (It is notable that as the young woman surrenders to her fate, all fear and sorrow leave her.) Like the hideous crones who are faery godmothers in disguise, La Huesera, scavenger of bones, is salvation cloaked in an unlikely form. The old woman carries the bones to a cave in the west, the place of the dead. Dead to her old life, if not to the world, the girl's spirit lingers, watches, and waits. Her patience is rewarded as her broken body is fashioned anew.

This "ritual death" is similar to shamanic initiation rites found in tribal cultures around the world. The initiates, in a state of trance, journey into the spirit world -- where their bodies die and are shorn of flesh, the bones picked over by spirits who are then persuaded, if all goes well, to sew them back together, better than new. (If the ceremonial procedure fails, however, an initiate can die in the trance state.) In this story, the young woman can be seen in the role of shamanic initiate. She lies down wrapped in long white cloth, the color of initiation. She leaves her body, returns to it, and finally becomes "twice-born," emerging from the cave (the womb of the Mother Earth) with a sacred gift for her people.

When she returns to her village, she is literally a new woman. She is given a new name, a new dwelling, and must learn to speak all over again. This, too, is common in initiation ceremonies found the world over. In one West African tribe, for instance, young male initiates drink a sacred brew which cause them to lose consciousness, whereupon they are taken into a special place deep in the jungle. When they wake, they have forgotten their past and must be taught to speak, walk, and feed themselves. They return to the tribe with new names and new roles, transformed from boys into men.

The safe return from the jungle, the forest, the spirit world, or the land of death often marks, in traditional tales, a time of new beginnings: new marriage, new life, and a new season of plenty and prosperity enriched not only by earthly treasures but those carried back from the Netherworld. Thomas the Rhymer, in the old Scottish ballad, returns to the human world after seven years in the woodlands of Faerie bearing the gift of prophesy, the "tongue that will not lie." Merlin returns from his time of exile and madness in the forests of Wales with magical knowledge and the ability to speak with the animals. Odin hangs in a death-like trance for ten days from the world-tree Yggdrasil, and comes back with the secret of runes from the dark land of Niflheim.

The hero of our story has also survived a great ordeal, a rite-of-passage from a barren life into one of great fecundity -- symbolized not only by marriage and children, but also by the precious tobacco seeds she brings for her people. To a modern audience, tobacco might seem a strange gift to appear in a healing tale since we now associate the plant with addiction, cancer, and death. Yet tobacco was once a sacred plant used only for ritual purpose and prayer -- particularly as old, ceremonial strains had hallucinogenic properties. (Some tribal elders say that it's casual use for non-religious purposes is what makes it so harmful today.)

Rites-of-passage stories like the one above were cherished in pre-literate societies not only for their entertainment value, but also as mythic tools to prepare young men and women for life's ordeals. A wealth of such stories can be found marking each major transition in the human life cycle: puberty, marriage, childbirth, menopause, death. Other rites-of-passage, less predictable but equally transformative, include times of sudden change and calamity such as illness and injury, the loss of one's home, the death of a loved one, etc. These are the times when we wake, like Dante, to find ourselves in a deep, dark wood -- an image that in Jungian psychology represents an inward journey. Rites-of���passage tales point to the hidden roads that lead out of the dark again -- and remind us that at the end of the journey we're not the same person as when we started. Ascending from the Netherworld (that grey landscape of illness, grief, depression, or despair), we are "twice-born" in our return to life, carrying seeds: new wisdom, ideas, creativity and fecundity of spirit.

This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2015, followed by three follow-up posts on illness beginning here.

Credits: The poem in the picture captions is "Otherwise" by Jane Kenyon, who was born in Michigan in 1947 and died of leukemia at the age of 48. The poem comes from her collection of the same title (Grey Wolf Press, 1996); all rights reserved by the author's estate. The drawings above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and Helen Stratton (1867-1961).

October 2, 2019

Nonsense and Foolery

My husband, Howard, a theatre director and performer, is about to embark on a year-long Journey into the Heart of the Fool -- via the Nomadic Academy of Fooling (NOA), led by the extraordinary Jonathan Kay. In order to achieve this, we've set up a fund-raising page to help cover the NOA tuition cost, and I hope, dear readers, that some of you might consider contributing. Even the smallest donation will help to get this creative, kind, and lovely man on the road to making magic.

In the video below, filmed in my studio, Howard and I discuss fooling, clowning, Commedia, and a particularly fateful trip to Arizona. A certain hound makes a cameo appearance at the end...and also contributes enthusiastic water-slurping noises in the middle, bless her.

In the spirit of nonsense and foolery, here is some further reading on the subject of tricksters, transgressors, and clowns:

A Chorus of Clowns in Masked Comic Theater by the always-brilliant Midori Snyder

Shaking Up the World: Trickster Tales by me (with a recommended reading list)

Merry Robin: The Native British Trickster by mythic scholar John Matthews

Transgression: a conversation on the subject of tricksters & transgressors

Dare to be Foolish: because all artists need to be fools sometimes

Also, if you're feeling very brave, here's a video clip of the Grey Gnomes, some deucedly odd little characters found infesting Howard's studio a few years ago. Don't worry, we've had the fumigators in since then and they haven't dared to come back....

And of course, any help you can give us in passing on news of the fundraiser would be very, very appreciated by our whole foolish family.

The colour photographs above (except for the last one) are from Howard's work with the Daughters of Elvin medieval music & dance troupe, directed by Katy Marchant. performing in Devon and Northern Ireland. The black and white pictures are of Howard and his Commedia company, Ophaboom Theatre, performing on the streets of Denmark.

September 30, 2019

Stories in the woods

My husband is often on the road with theatre work, and our daughter is grown and living in the city, so the hound and I are frequently on our own for days or weeks at a time now. I have always loved silence and solitude, so marriage to a peripatetic thespian suits me fine -- gifting me with quiet swathes of time to sink down deep into my work...or to disappear into the woods...punctuated by sweet reunions when our tiny house  overflows with family life.

overflows with family life.

Writing, said novelist Paul Auster, is "an odd way to spend your life -- sitting alone in a room with a pen in your hand, hour after hour, day after day, year after year, struggling to put words on pieces of paper in order to give birth to what does not exist, except in your head. Why on earth would anyone want to do such a thing? The only answer I have ever been able to come up with is: because you have to, because you have no choice.��� "

But for some of us, sitting alone in a room (or in the woods) is one of the pleasures of the writing life. It's not something I endure in order to write, it's something I crave, and the writing rises from it.

"It is really hard to be lonely very long in a world of words," said poet Naomi Shihab Nye. "Even if you don't have friends somewhere, you still have language, and it will find you and wrap its little syllables around you and suddenly there will be a story to live in."

What about you? Are you a solitary artist? A collaborative one? Where do you instinctively go to find the stories you live inside of...?

Words: The quotes above are from "I Want to Tell You a Story" by Paul Auster (The Guardian, November, 2006) and I'll Ask You Three Times, Are You Okay? by Naomi Shihab Nye (HarperCollins, 2007). The poem excerpt in the picture captions is from "Valentine for Ernest Mann" by Naomi Shihab Nye, published in Red Suitcase (Perfection, 1994). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Nattadon Woods in early autumn. The fox is by Inga Moore.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

American and Canadian roots music today, both old and new....

Above: "Better for You" by Kalyna Rake, in a video filmed by Myles O'Reilly in West Cork, Ireland (during the Clonakilty International Guitar Festival) earlier this month.

Below: "The Art of Forgetting" by Kyle Carey, from her album of the same name (2018).

Above: "Glory Bound" and "Wildflowers" by The Wailin' Jennys (Ruth Moody, Nicky Mehta, and Heather Masse), performed for the Attic Sessions (2018).

Below: "Trouble and Woe" by Ruth Moody, performed for Live from the Great Hall (2013).

Above: "St. Elizabeth" by Kaia Kater, from her album Nine Pin (2016).

Below: "Cuckoo" by Rising Appalachia (sisters Leah and Chloe Smith), from their new album Leylines (2019).

(If you'd like one more today, I recommend "Colorado" by the Brother Brothers with Sarah Jarosz, which cannot be embedded here.)

September 27, 2019

The stories that take root

From "Testimony Against Gertrude Stein," an essay by Jeanette Winterson:

"We mostly understand ourselves through an endless series of stories told to ourselves by ourselves and others. The so-called facts of our individual words are highly colored and arbitrary, facts that fit whatever fiction we have chosen to believe in. It is necessary to have a story, an alibi that gets us through the day, but what happens when the story becomes scripture? When we can no longer recognize anything outside our own reality?

"We have to be careful not to live in a state of constant self-censorship, where whatever conflicts with our world view is dismissed or diluted until it ceases to be a bother. Struggling against the limitations we place on our minds is our own imaginative capacity, a recognition of an inner life often at odds with the internal figurings we spend so much energy supporting.

"When we let ourselves respond to poetry, to music, to pictures, we are clearing out a space where new stories can root, in effect we are clearing a space for new stories about ourselves."

The passage just quoted nails, for me, precisely why we need art in our lives and not just the familiar, repetitive stories of mass entertainment, enjoyable as they may be. Entertainment amuses, distracts, and consoles us, and that has its use and it has its value, but it's not the same use or value of art. Art enlarges us. Transforms us. Heals what is broken inside us. Deepens our understanding of ourselves, each other, and the world around us.

"Art is central to all our lives, not just the better-off and educated, " Winterson once said in an interview. "I know that from my own story, and from the evidence of every child ever born -- they all want to hear and to tell stories, to sing, to make music, to act out little dramas, to paint pictures, to make sculptures. This is born in and we breed it out. And then, when we have bred it out, we say that art is elitist, and at the same time we either fetishize art -- the high prices, the jargon, the inaccessibility -- or we ignore it. The truth is, artist or not, we are all born on the creative continuum, and that is a heritage and a birthright of all of our lives."

Words: The first quote above is from "Testimony Against Gertrude Stein," published in Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery by Jeanette Winterson (Knopf, 1996). The second is from "Upfront: Talking with Jeanette Winterson" (The New York Times Sunday Book Review, Dec. 19, 2008). All rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: Tilly and the Oak Elder, acorns in early autumn, and an Oak Child from one of my sketchbooks.

September 26, 2019

The dignity business

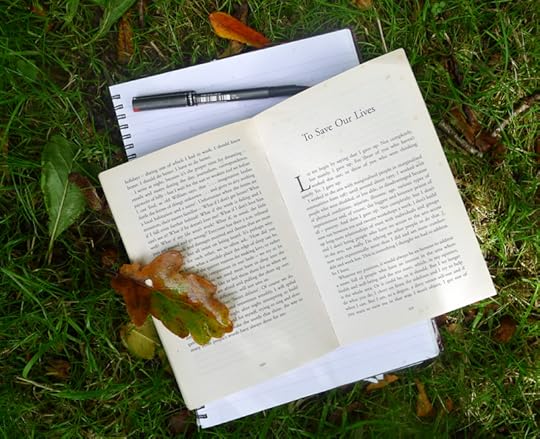

From "To Save Our Lives," an essay by A.L. Kennedy:

"Let's begin at my beginning. Perhaps some of you will identify. I had an interest in theatre -- it had lit me, had sustained me through a small-town childhood and adolescence. I remember watching a TV production of Chekhov's Three Sisters, knowing nothing of the man or his life, but understanding that when the characters said 'To Moscow, to Moscow' that I knew exactly how they felt. Chekhov articulated the horror of being trapped in a dead end and out of context, of being a permanent stranger. He had also let me know that I wasn't alone, other people felt like that -- like Chekhov, whose brother remembered him saying, 'In my childhood, I had no childhood.' Chekhov grew up in the Crimean backwater of Taganrog, not Moscow -- it took him a while to reach Moscow, to reach himself. On the 7th January 1889, when he was just shy of his twenty-ninth birthday, he wrote to his friend Suvorin:

Write a story about a young man, the son of a serf, a former shop-minder, chorister, schoolboy and student who was brought up to fawn upon rank, to kiss priests' hands and to worship others' thoughts...write how this man squeezes the slave out of himself, drop by drop, and then wakes up one fine morning to discover that in his veins flows not the blood of a slave, but of a real human being...

"As I say, when I saw Three Sisters I didn't know about Chekhov's life, I didn't know he had a bumpy childhood like mine, I didn't know he worked with prisoners and the poor, I didn't know anything other than what he made, the product of simple, joyful, human creativity -- his writing. But it started to squeeze the slave out of my blood, drop by drop.

"And I read -- all I could get -- and then I went to university, because a grant made it financially possible for me. It wouldn't have mattered how many exams I passed, I wouldn't have got there without a grant. Beyond university, I started to work with community groups and special-needs groups, partly because I couldn't do anything else, partly because I was looking for something and I didn't know what, but it somehow seemed the proper course for me to write and to search in the company of other people. On the one hand, I was completely busking it. I was working with groups of radically mixed ability, in unsuitable spaces, inventing everything from scratch. Very few people were working with non-literate people to produce writing -- I had to make up how we did that, relying on the fact that written words are simply a high-status record of what someone would say in their absence. I hoped that if we worked out how to catch what people wanted to say and how to finish it in a way that was pleasing to them, we could proceed happily. And so we did. Simply earning a living until I found out my proper direction was pretty much all I had as a plan, but then I saw -- I saw face after face changing after one session, ten sessions, twenty sessions -- I saw the slave leaving the blood. I laughed more than I ever had. And I cried. We all laughed and cried. I found out about people. I was no longer alone.

"I found out what happens when, for example, I watch Three Sisters, when I touch art and art touches me. That's when I get something beautiful and new in my life. I feel no longer alone, I have more strength to be myself and I see there may be other possibilities beyond the here and now.

"I receive a gift within which is a kind of hope about human nature -- it's not na��ve, but it's not the unreality of reality TV, not a cheap and nasty opportunity to feel good about ourselves because other people are manifestly more dysfunctional than we are, more stupid, more greedy, more sex-obsessed, more shoddy. Functional art doesn't show us that -- a toxic stasis, a warning not to leave the house -- it shows us what we really are and could be, good or bad. Art is about motion, strategies, rehearsals of new futures. It's a power.

"And think -- of course you've thought -- if you're not just receiving the end product, accepting the gift from the artist, joining in humanity with someone who may be in many ways alien to you -- from another culture, another country, another time, who may be dead -- what if you make that art? What if others can suddenly know a part of you, a deep and intimate part of you, the dreams you make? What if you light them and are useful, bring them into what might have been an alien experience? What if you change their lives? How could that possibly not be a joy in your life and change you? How could that not possibly improve, for example, your health and well-being?

"I began with mercenary and confused motives, running drama workshops, leading writing workshops, improvising from nothing -- and I found a wonder, a purity: people making things for other people, being useful and getting well -- not markets, not an industry, not egos, not much -- just beauty, at very little expense, over and over and over."

A little later in the essay, Kennedy adds:

"When we make art, art to which we commit ourselves, art which isn't simply a commercial artifact, a pose, a gesture towards a concept, when we go all out and really create, we do a number of remarkable things. We take on a little of what we usually set aside for the divine -- the troubles and delights which spring from overturning entropy and bringing something out of nothing. We excel. We offer something of ourselves, or from ourselves, to others. We allow and encourage a miracle -- one human being can enter the thoughts and life of another. We can be the other: the king, the foreigner, the wino, the superstar, the debutante, the murderer, we can experience a little of the large, strange, wonderful, horrible thing which is the human experience.

"What we make can reveal us to ourselves as greater than we were and help us practice addressing the world with courage and -- because it is practical to involve such a thing -- with love. As the listener, the viewer, the reader, the recipient of art, once again we are, of course, encouraged to be greater.

"The proverb tells us we should walk a mile in a person's shoes before we judge them. And if we've spent a whole novel in their thoughts, if we've heard their heart in music, if we've seen as they do how light falls, if we've breathed with them as they speak, felt the way they dance under our skins? Then I believe it is very difficult not to grant others at least dignity, at least that. In the arts, I feel we are in the dignity business."

I urge you to read Kennedy's essay in full, which can be found in her frank, witty, erudite and inspiring book On Writing.

Words: The passage by A.L. Kennedy is from her essay "To Save Our Lives," published in On Writing (Vintage Books, 2014). The poem in the picture captions is from O the Chimneys by Nelly Sachs (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1967), translated by Ruth & Matthew Mead. All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Dartmoor ponies grazing and snoozing by a bench on the village Commons where I often go to read and write.

September 25, 2019

Narrative is radical

''Is there no context for our lives? No song, no literature, no poem full of vitamins, no history connected to experience that you can pass along to help us start strong? You are an adult. The old one, the wise one. Stop thinking about saving your face. Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story. Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created.'' - Toni Morrison

Imagery above: Two photographs from my Wild Words series, and a drawing by Charles Robinson (1870-1937). All rights to the quotes above and in the picture captions reserved by the Toni Morrison estate.

September 24, 2019

Words to live by

"There are really only two questions for activists: What do you want to achieve? And who do you want to be? And those two questions are deeply entwined. Every minute of every hour of every day you are making the world, just as you are making yourself, and you might as well do it with generosity and kindness and style." - Rebecca Solnit

I'd say the same for writers and artists too.

Words: The quote above is from Rebecca Solnit's essay "We Could Be Heroes" (The Guardian, Oct. 15, 2012). The quotes in the picture captions are from Solnit's books The Faraway Nearby (Viking, 2013) and Men Explain Things to Me (Granta, 2014), both of which are highly recommended. Pictures: A Dartmoor pony on O'er Hill.

September 23, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

It's a quiet, rainy morning here in Devon, I'm back in the studio at last and starting the week with beautiful music from Wales, both old and new....

Above: "Pan O'wn y Gwanwyn" by Alaw (Oli Wilson-Dickson, Dylan Fowler, and Jamie Smith). The song is from their second album, Dead Man's Dance (2017). The video was filmed at Twyn y Gaer hill fort near Abergavenny.

Below" "Breuddwyd y Wrach/Nyth y Gog" by Alaw, performed at Acapela Studio in 2013.

Above: "Cardod" by Gwilym Bowen Rhys, a singer-songwriter from North West Wales. This piece, blending 17th century poetry and 18th century fiddle music, appears on his fine new album, Arenig (2019). Also, "Arenig," the title song from the new album, featuring poetry by Euros Bowen (Rhys' great-uncle) about the Arenig mountains of Snowdonia.

Below: "Dig Me a Hole" by Gwyneth Glyn, a singer, poet, and playright from Eifionydd on the Ll��n Peninsula. The song appears on Glyn's solo album Tro (2017).

Above: "The Cliffs" by Isembards Wheel, a folk band based in Cardiff. The song is from their EP Autumn In Eden (2016).

Below: "The Fisherman" by The Gentle Good (singer-songwriter Gareth Bonello) from Cardiff -- with Callum Duggan on double bass and Jennifer Gallichan on vocals. It appears on Bonello's fourth album, Ruins/Adfeilion (2016).

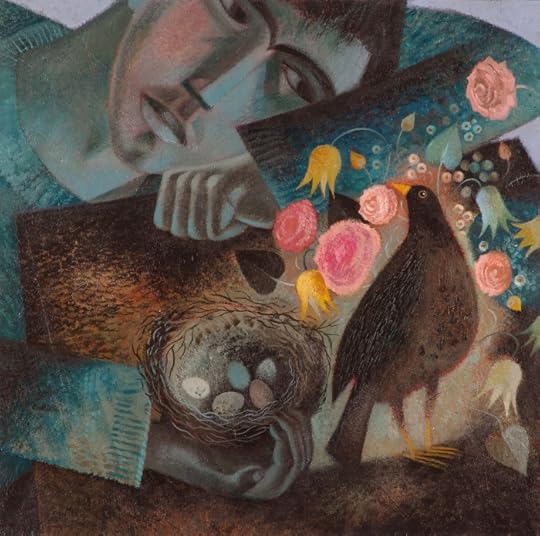

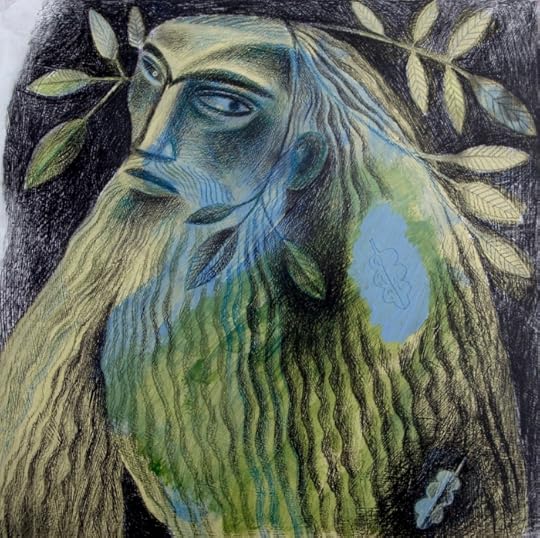

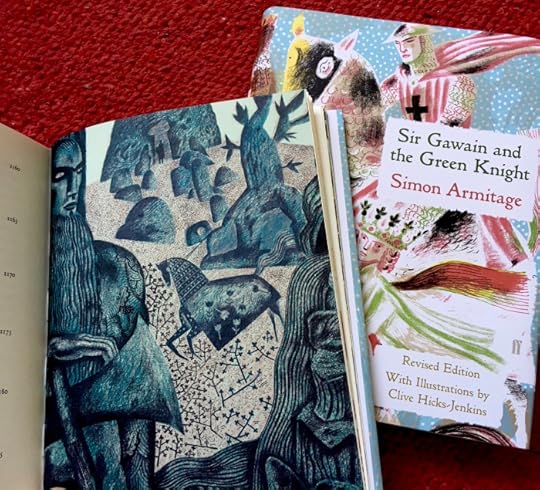

The imagery today is by one of my favourite artists (and favourite people), Clive Hicks-Jenkins, who was born in south Wales, and now lives on the Welsh coast near Aberystwyth. After a distinguished career as a director, performer, choreographer and puppeteer for stage, film, and television, Clive turned to making art in a wide variety of forms, including painting, drawing, printmaking, ceramics, maquettes, animation, and artist���s books. His work -- inspired by myth, Romance, folklore, poetry, Biblical stories, and the history and landscape of Wales -- can now be found in museums, galleries, libraries, and private collections the world over.

As his biography notes: "In 2016 Random Spectacular published Hicks-Jenkins' dark reworking of Hansel & Gretel into a picture book; and the following year Benjamin Pollock's Toyshop in Covent Garden commissioned a Hansel & Gretel toy theatre kit based on it. In response to the two publications, Goldfield Productions engaged the artist, to direct and design a new version of the fairytale, with music by Matthew Kaner and a libretto by the poet Simon Armitage. Performed by a chamber consort, a narrator/singer and two puppeteers, it premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival in July 2018, earning a four-star review from The Guardian before beginning a five month tour of music festivals. The London premiere at Barbican was recorded by BBC Radio 3 for broadcast in December 2018. Hansel & Gretel was the second collaboration between the artist and poet, coming on the heels of Faber & Faber publishing Armitage���s revision of his translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, illustrated throughout with the fourteen screenprints Hicks-Jenkins made in collaboration with Penfold Press."

As his biography notes: "In 2016 Random Spectacular published Hicks-Jenkins' dark reworking of Hansel & Gretel into a picture book; and the following year Benjamin Pollock's Toyshop in Covent Garden commissioned a Hansel & Gretel toy theatre kit based on it. In response to the two publications, Goldfield Productions engaged the artist, to direct and design a new version of the fairytale, with music by Matthew Kaner and a libretto by the poet Simon Armitage. Performed by a chamber consort, a narrator/singer and two puppeteers, it premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival in July 2018, earning a four-star review from The Guardian before beginning a five month tour of music festivals. The London premiere at Barbican was recorded by BBC Radio 3 for broadcast in December 2018. Hansel & Gretel was the second collaboration between the artist and poet, coming on the heels of Faber & Faber publishing Armitage���s revision of his translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, illustrated throughout with the fourteen screenprints Hicks-Jenkins made in collaboration with Penfold Press."

To see more of Clive's absolutely gorgeous work, please visit his website and art blog.

September 19, 2019

With love to all those marching today...

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers