Terri Windling's Blog, page 52

September 16, 2019

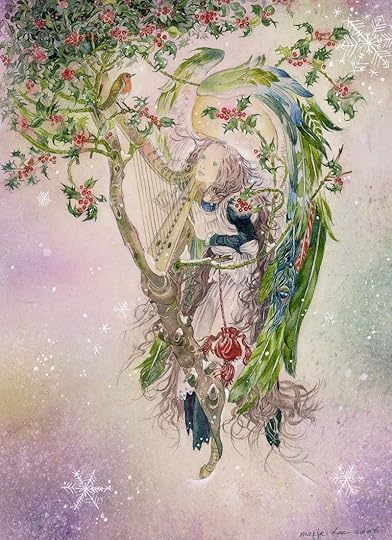

The Enchanted Harp

Dear Readers, I'd promised to be back to this blog by Friday, but I'm still catching up on work missed while I was down with the flu and I'm afraid that must take priority. My apologies for the lack of Monday tunes today -- but here, at least, is a post about music, from the Myth & Moor archives....

A tale from Scotland's Isle of Skye relates how music first came to those lands. A poor youth found a strange instrument (a triangular harp) floating in the waves. He fished it out, set it upright, and the wind began to play the strings -- an eerie, lovely sound the like of which had never been heard. The boy could not duplicate the sound, although he tried for many long days. So obsessed did he become that his widowed mother ran to a wizard (a dubh-sgoilear) to beg him to give her son the skill to play the instrument -- or else to quell his desire  for it. The dubh-sgoilear offered her this choice: he would take away the boy's desire in exchange for the widow's body, or he'd give him the gift of music in exchange for her mortal soul. She chose the later and returned home where she found her son plucking beautiful, heavenly music from the strings of the harp. But the boy was horrified to learn the price his mother had paid for his skill. From that moment on, he began to play music so sad that the birds and the fish stopped to listen. And that, concludes the old Scottish tale, is why the music of the harp sounds poignant to this very day.

for it. The dubh-sgoilear offered her this choice: he would take away the boy's desire in exchange for the widow's body, or he'd give him the gift of music in exchange for her mortal soul. She chose the later and returned home where she found her son plucking beautiful, heavenly music from the strings of the harp. But the boy was horrified to learn the price his mother had paid for his skill. From that moment on, he began to play music so sad that the birds and the fish stopped to listen. And that, concludes the old Scottish tale, is why the music of the harp sounds poignant to this very day.

From Ireland comes another tale about the earliest harp music: Boand was the wife of the Dagda Mor, a deity of the Tuatha De Danann (the faery race of Ireland). As Boand gave birth to the Dagda's three sons, the Dagda's harper played along to ease the woman's labor. The harp groaned with the intensity of the pain as the woman's first child emerged, and so she named her eldest son Goltrai, the crying music. The music made a merry sound as Boand's second son was born, and so she named the child Gentrai, the laughing music. At last the final infant emerged to music that was soft and sweet. She called the child Suantri, the sleeping (or healing) music. These three strains of music are still found in the repertoire of Celtic musicians -- as echoed by the Scots-English ballad recounting the trials of King Orfeo (a harper in the oldest songs, a fiddler in later variants) who played three strains of music before the king of the faery underworld: the notes of joy, the notes of pain, and the enchanted faery reel.

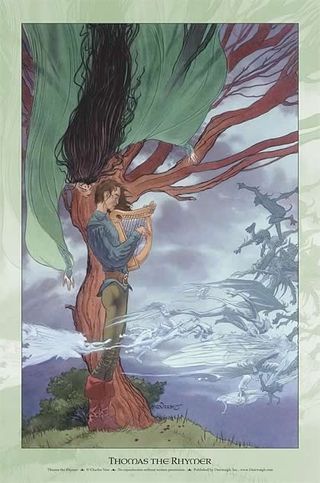

It is interesting to note that the modern revival of interest in traditional folk music, beginning in the 1970s, paralleled the modern revival of interest in fantasy fiction (and the birth of the fantasy publishing genre in the same decade). It is not surprising that the audiences for folk music and fantasy stories overlap, for both art forms are rooted in the lore and legends of our folk heritage. Today, you'll find quite a number of fantasy novels and stories infused with folk music and traditional ballads. Bards and wandering minstrels have long been staple characters in books set in medieval or imaginary lands, and more often than not, a small, hand-held, Celtic style harp is the instrument they play. The quick-witted Morgan of Hed in Patricia McKillip's "Riddlemaster" books, for example, was one of the first (and remains one of the best) harp-toting protagonists in contemporary fantasy fiction. Patricia C. Wrede (The Harp of Imach Thysell), Morgan Llewelyn (Bard), Charles de Lint (Moonheart) and other writers from early days of the fantasy genre created memorable bardic characters, and Ellen Kushner told the quintessential harper tale in her award-winning, balllad-inspired novel, Thomas the Rhymer.

It is interesting to note that the modern revival of interest in traditional folk music, beginning in the 1970s, paralleled the modern revival of interest in fantasy fiction (and the birth of the fantasy publishing genre in the same decade). It is not surprising that the audiences for folk music and fantasy stories overlap, for both art forms are rooted in the lore and legends of our folk heritage. Today, you'll find quite a number of fantasy novels and stories infused with folk music and traditional ballads. Bards and wandering minstrels have long been staple characters in books set in medieval or imaginary lands, and more often than not, a small, hand-held, Celtic style harp is the instrument they play. The quick-witted Morgan of Hed in Patricia McKillip's "Riddlemaster" books, for example, was one of the first (and remains one of the best) harp-toting protagonists in contemporary fantasy fiction. Patricia C. Wrede (The Harp of Imach Thysell), Morgan Llewelyn (Bard), Charles de Lint (Moonheart) and other writers from early days of the fantasy genre created memorable bardic characters, and Ellen Kushner told the quintessential harper tale in her award-winning, balllad-inspired novel, Thomas the Rhymer.

It's not difficult to see why the harp became the instrument of choice in fantasy literature, for it is one that has always been associated with magic. The earliest harps of western Europe were most often made of willow wood, a tree sacred to the Goddess, associated with the cycles of the moon, fertility, and enchantment. The strings of the harp symbolize the mystic bridge between heaven and earth; mankind stands poised in the middle, striving now toward one and now toward the other as represented by the tension of the strings (portrayed in Bosch's painting "The Garden of Delights," where a man hangs from the strings, crucified). The harp has been associated with early pagan religions, its music called "the voice of the gods," although it was later absorbed into the Christian church and the celestial choir.

It was thought that the harp as we know it today originally came from Ireland, spreading across Scotland and Wales and over the Channel to Europe. But in 1992 the music historians Keith Sanger & Alison Kinnaird published Tree of Strings: Crann Nan Tued, a thorough, well-written history of the harp, presenting strong archaeological evidence that the earliest instruments came from Scotland. (The harp is found carved onto Picto-Scottish stones at least 200 to 300 years earlier than pictorial representations elsewhere in the world.) According to Sanger & Kinnaird, these large, floor-standing instruments (triangular in frame, probably strung  with horsehair) passed to Wales sometime between the 6th and 9th centuries during waves of immigration from the north, while the Irish are likely to have come into contact with the harp through their religious communities established in the west of Scotland. When the Irish brought the instrument home, they altered the shape and gave it metal strings. This is the harp we know today as the Gaelic harp or clarsach.

with horsehair) passed to Wales sometime between the 6th and 9th centuries during waves of immigration from the north, while the Irish are likely to have come into contact with the harp through their religious communities established in the west of Scotland. When the Irish brought the instrument home, they altered the shape and gave it metal strings. This is the harp we know today as the Gaelic harp or clarsach.

Sanger & Kinnaird point out that it's not entirely accurate to call the harp a "folk" instrument. For many centuries the harp firmly belonged to the aristocracy; it was not an instrument to be found (like the fiddle and whistle) in a poor man's croft. Harpers were trained and educated; they were esteemed (and esteemed themselves) quite highly compared to other musicians. For common people, the opportunity to hear the music of the harp was rare indeed. In Scandinavia, harps were noble instruments by law; a commoner who dared to play the harp could find himself sentenced to death. This gave the instrument a powerful aura of otherworldliness, surrounding harp music with magical legends and supernatural associations. The ancient Volsunga Saga recounts the death of Gunnar, brother to Sigurd the Dragon-slayer. Thrown into a pit of poisonous snakes by vengeful enemies, Gunnar kept death at bay  by playing a mystical song upon his harp, enchanting the serpents to sleep. For an entire day and night he played, but as the dawn broke over the land his tired fingers fumbled and one snake sunk its poison into Gunnar's hand.

by playing a mystical song upon his harp, enchanting the serpents to sleep. For an entire day and night he played, but as the dawn broke over the land his tired fingers fumbled and one snake sunk its poison into Gunnar's hand.

We find other magical harps in countless fairy tales, epic poems, and songs. In a Swedish tale, a young hunter saves his wife from the lust of an arrogant prince by invoking the aid of her wolf-relatives to build him a harp -- a magical harp with which to gain her freedom. In a poem from Iceland (also a ballad from Scotland) one sister drowns another in order to steal the drowning girl's fiance. The body eventually floats to land, where a minstrel makes a harp from the girl's breast bone, strung with her golden hair. When he plays for the murderous sister's wedding, the harp speaks with the dead girl's voice and exposes the bride's treachery. The Scottish harper Glenkindie (like the fiddler Jack Orion) could "harp the fish out of the salt sea, or water out of a stone, or milk out of a maiden's breast though baby had she none." He plays a sleeping spell in order to seduce the daughter in a great lord's hall, but his serving man, in pursuit of the same woman, harps Glenkindie to sleep in turn and steals the maiden away for himself. The sinister Elf Knight uses a similar trick to seduce the Lady Isobel -- but she is a quick-witted young woman and escapes the encounter with her maidenhead intact. Thomas the Rhymer is the most famous harper of Scottish balladry. The Queen of Faery (known to have a fancy for handsome mortal musicians) seduces Thomas and steals him away to Faerieland for seven years. When she sends him home again, it is with the gift (or the curse) of "the tongue that cannot lie."

In Arthurian romance, Tristan disguises himself as a wandering harper when he travels from Cornwall to Ireland, seeking the cure for a poisonous wound inflicted by an Irish hero. It is there he encounters the fair Iseult and determines to win her for his Cornish king, never dreaming that he will come to love her himself, and thereby seal his doom.

In Russia, the harp was known as a gusla, the wandering harpist as a guslar. One legend tells of a Tsar who is captured while travelling in the Holy Lands. His brave Tsarita dons men's clothes, takes up her gusla, and  follows his path. Playing before the infidel king, she wins her husband's freedom. The guslars of Russia are comparable to the bards to be found in Celtic lands: trained in archaic poetic modes, severe and highly formal, which were performed as sung recitations while accompanied by the harp. In the British Isles, in ancient times, the bards were held in the highest esteem. They were scholars, historians, genealogists, valued advisors to nobles and kings, and believed to possess certain magical powers; their satires could curse, even kill a man, while their poems of praise lifted fortunes. In Ireland, the fili (a hereditary position requiring at least six years of training in one of the poetic colleges) composed poetry but did not perform it; the reacaire would chant or recite with musical accompaniment from a harper. In Scotland, these three separate positions came together in the person of the bard. While not quite as highly trained as the fili, he nonetheless composed poetry himself, performed, and generally played his own harp.

follows his path. Playing before the infidel king, she wins her husband's freedom. The guslars of Russia are comparable to the bards to be found in Celtic lands: trained in archaic poetic modes, severe and highly formal, which were performed as sung recitations while accompanied by the harp. In the British Isles, in ancient times, the bards were held in the highest esteem. They were scholars, historians, genealogists, valued advisors to nobles and kings, and believed to possess certain magical powers; their satires could curse, even kill a man, while their poems of praise lifted fortunes. In Ireland, the fili (a hereditary position requiring at least six years of training in one of the poetic colleges) composed poetry but did not perform it; the reacaire would chant or recite with musical accompaniment from a harper. In Scotland, these three separate positions came together in the person of the bard. While not quite as highly trained as the fili, he nonetheless composed poetry himself, performed, and generally played his own harp.

Until the 15th and 16th centuries fili and bard used formal syllabic verse. When "amhran" apppeared (one of the basic meters of folk poetry), it swept across Europe and the British Isles, carried by traveling troubadours. As the strict rules of poetry became more relaxed, the role of fili began to disappear -- sped by the political events undermining the Irish and  Highland Scottish social structures. In the early 17th century, the Irish poetic colleges collapsed; in Scotland, the less strict bardic training survived another hundred years. After this, harpers began to take on roles that combined those of the fili and the wandering troubadours. Their status fluctuated, then fell drastically. The British Crown considered traveling harpers to be political subversives; Queen Elisabeth I turned the bards into outlaws, uttering her famous proclamation: "Hang the harpers wherever found." Cromwell joined in by enacted a vicious harp-breaking policy. By the time of the famous 1792 gathering of harpers in Belfast, the proud old profession of bard was virtually extinct; wandering harpers were generally poor men with no alternative means of support -- like the famous blind harper O'Carolan, whose music is still played by harpers today.

Highland Scottish social structures. In the early 17th century, the Irish poetic colleges collapsed; in Scotland, the less strict bardic training survived another hundred years. After this, harpers began to take on roles that combined those of the fili and the wandering troubadours. Their status fluctuated, then fell drastically. The British Crown considered traveling harpers to be political subversives; Queen Elisabeth I turned the bards into outlaws, uttering her famous proclamation: "Hang the harpers wherever found." Cromwell joined in by enacted a vicious harp-breaking policy. By the time of the famous 1792 gathering of harpers in Belfast, the proud old profession of bard was virtually extinct; wandering harpers were generally poor men with no alternative means of support -- like the famous blind harper O'Carolan, whose music is still played by harpers today.

In the early 1800s, harp music and its attendant folklore underwent a public revival, aided by the efforts of the Dublin poet-musician Thomas Moore. Moore wrote poems to Irish folk tunes and published them with tremendous success; his popularity rivalled Byron's and Scott's during his day, and his songs are still sung. In 1810, modern mechanization allowed a new type of harp to be patented which permitted musicians to play in all musical keys. This brought the harp back into classical orchestras and unleashed a flood of new music. The harp become a popular parlor instrument -- particularly among genteel young ladies, who, it was claimed, enjoyed the excuse to flash their slim ankles to admirers.

Even in the area of classical music, the harp had an aura of magic and enchantment. The Victorians, with their strong interest in folklore, spiritualism and the Celtic Twilight, embraced the music of the harp with a fervor that is almost hard to imagine today. A wealth of Victorian "fairy music" for the harp was written, published and performed -- music which eventually fell out of fashion along with the mystical medievalism and Arthurianism of the Pre-Raphaelites, the spiritualism and florid fantasies characterizing the age. Despite its great popularity during its day, the existence of this 19th-century fairy music was nearly forgotten altogether until English harp player Elizabeth-Jane Baldry released her lovely CD, "Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain."

Even in the area of classical music, the harp had an aura of magic and enchantment. The Victorians, with their strong interest in folklore, spiritualism and the Celtic Twilight, embraced the music of the harp with a fervor that is almost hard to imagine today. A wealth of Victorian "fairy music" for the harp was written, published and performed -- music which eventually fell out of fashion along with the mystical medievalism and Arthurianism of the Pre-Raphaelites, the spiritualism and florid fantasies characterizing the age. Despite its great popularity during its day, the existence of this 19th-century fairy music was nearly forgotten altogether until English harp player Elizabeth-Jane Baldry released her lovely CD, "Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain."

Elizabeth-Jane is an old friend and neighbor of mine, living in tiny, magical cottage crowded with harps, books, musical scores and art. As a harp teacher as well as a performer and composer, she is largely responsible for the fact that there are few places one can walk in our village without hearing someone, somewhere, practicing classical or Celtic harp. With her long dark hair and long skirts she might have stepped from a Pre-Raphaelite painting, and her breadth of knowledge about Victorian culture, folklore, fairies, and the history of harp music is impressive.

"The fairy music on Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain," she says, "is the result of a journey into the Victorian fascination with the transcendental. All the music has lain forgotten in the vast archives of the British Library, and has never before been recorded or even performed in modern times. Its composers, once famous touring virtuosi, are now long dead and forgotten. Most compelling was the discovery that so many elements of the Victorian psyche are distilled in the music: a revolt against Darwinism and the birth of the scientific age, the spectacular rise of the spiritualist movement affecting even the Royal Court, a nostalgia for our rural past as the industrial revolution  tightened its hold, and the rise of the middle classes with their demand for accessible music. Furthermore, the Victorian love affair with Scotland contributed to the popularity of the harp, Scotland's oldest national instrument. There was an interest for the first time in our folk heritage. The erotic imagery of fairies was an obvious outlet for the repressed sexuality of the time. Orgiastic paintings of naked frolics became respectable provided the participants had wings! Fairy music for the harp is the essence of Victorian idealism."

tightened its hold, and the rise of the middle classes with their demand for accessible music. Furthermore, the Victorian love affair with Scotland contributed to the popularity of the harp, Scotland's oldest national instrument. There was an interest for the first time in our folk heritage. The erotic imagery of fairies was an obvious outlet for the repressed sexuality of the time. Orgiastic paintings of naked frolics became respectable provided the participants had wings! Fairy music for the harp is the essence of Victorian idealism."

Elizabeth-Jane unearthed this cache of Victorian fairy music while doing research at the British Library in London. Amazed by both the quantity and the quality of this music, she swiftly made plans to put together a recording of selections from this work. Her CD was recorded on location in the 19th-century ballroom of Buckland Manor: an eighty-five-room country manor house, virtually empty, rising from the Devon countryside like the house in a gothic romance. "As I played," she recalls, "looking out on a hundred acres of untouched parkland on a golden autumn day, the wind gusting, empty urns filled with blown leaves, I felt goose-shivers down my spine . . . knowing this music hadn't been played in a century. The last time it had been performed, the manor's ballroom had just been built."

As she plucked the rippling notes of "Ondine," a reverie for harp by Georgio Lorenzi (inspired by Baron de la Motte Fouque's tragic story of a  knight and a water-spirit), Elizabeth-Jane heard a woman's scream. The recording engineers heard it too and the sound was captured upon the tape. And yet, when investigated, no source for the scream could be found in that empty place. Only later did she discover that a Victorian woman had met her death in that very room, "thrown from the balcony by a husband enraged by her extravagant spending."

knight and a water-spirit), Elizabeth-Jane heard a woman's scream. The recording engineers heard it too and the sound was captured upon the tape. And yet, when investigated, no source for the scream could be found in that empty place. Only later did she discover that a Victorian woman had met her death in that very room, "thrown from the balcony by a husband enraged by her extravagant spending."

The late 20th century revival of interest in harp music was, like the earlier Victorian revival, entwined with an interest in all things folkloric, fantastic and mystical. I was fortunate to be a student in Dublin in the mid-1970s, when the contemporary Celtic music renaissance was first building up its steam -- a thrilling time to see new bands like Clannad adapt the Celtic harp to a new Celtic sound, or to catch sight of The Chieftain's legendary harper Derek Bell in the smokey rooms of an old Dublin pub. The Breton harper Alan Stivell began to build a following about the same time, influencing many of the younger musicians who followed after. Stivell's "Renaissance de la Harpe Celtique" is a CD that tops the list of recommendations for anyone interested in Celtic harp music.

There are so many fine harpists working today that it's impossible to list them all here, but any survey of the field should certainly also include Patrick Ball, Dominig Bouchaud, Robin Huw Bowen, C��cile Corbel, Paul Dooley, Loreena McKennitt, ��ine Minogue, Joanna Newsom, Maire Ni Chathsaigh, Nansi Richards, Kim Robertson, Sileas (Patsy Seddon & Mary Macmaster), Savourna Stevenson, and Robin Williamson. (Despite the proponderence of women harpists today, it should be noted that in the past women harpers were rare, often dismissed and slandered as "loose-living" women. In the Dark Ages it was strictly against the law for women to harp.)

There are so many fine harpists working today that it's impossible to list them all here, but any survey of the field should certainly also include Patrick Ball, Dominig Bouchaud, Robin Huw Bowen, C��cile Corbel, Paul Dooley, Loreena McKennitt, ��ine Minogue, Joanna Newsom, Maire Ni Chathsaigh, Nansi Richards, Kim Robertson, Sileas (Patsy Seddon & Mary Macmaster), Savourna Stevenson, and Robin Williamson. (Despite the proponderence of women harpists today, it should be noted that in the past women harpers were rare, often dismissed and slandered as "loose-living" women. In the Dark Ages it was strictly against the law for women to harp.)

"O wake once more," Sir Walter Scott once commanded the ancient harps of Scotland. "If one heart throb higher at its sway, the wizard note has not been touch'd in vain. Then silent be no more! Enchantress, wake again!"

More than two hundred years later, the harps are awake, and still making their magic.

Art credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

September 9, 2019

Myth & Moor update

My apologies for the delay in posting. I was down with a cold/flu bug last week, and the early part of this week is dedicated to a work session here in Chagford with colleagues from the Modern Fairies project. My schedule is a bit over-packed at the moment, but I'll be back to Myth & Moor by Friday at the latest. Thank you all for your patience.

In the meantime, since I'm not posting music today I recommend checking out the fabulous Folk on Foot project, if you don't know it already.

The fairy art today is, of course, by Arthur Rackham.

September 2, 2019

Art, activism, and the soil we grow in

Following on from Saturday's post, here's another insightful passage from Writing the Sacred Into the Real by Alison Hawthorne Deming:

"In 1997, I was asked by the Orion Society to lead a conversation at the colloquium in honor of Gary Snyder when he received the John Hay Award for his writing and activism. My assignment was to address the question, Does activism compromise one's art? The question was very American, as Snyder pointed out. In [continental] Europe and Asia, an artist is a public person -- seeing the responsibility to use some of his or her skills on behalf of society. I answered the question by saying, Yes, of course compromise occurs. The work of activism exhausts us and makes us grieve; it takes us from our studios; it makes us scholars, negotiators, combatants, administrators, and business heads when we would prefer to be makers, dreamers, healers, and dancers. And if art is made to serve our activism, it can lose its elemental engagement with the unknown; its freedom to be outrageous, obscure, absurd, and wild; its need to speak the truth as it cannot be spoken in political discourse.

"In 1997, I was asked by the Orion Society to lead a conversation at the colloquium in honor of Gary Snyder when he received the John Hay Award for his writing and activism. My assignment was to address the question, Does activism compromise one's art? The question was very American, as Snyder pointed out. In [continental] Europe and Asia, an artist is a public person -- seeing the responsibility to use some of his or her skills on behalf of society. I answered the question by saying, Yes, of course compromise occurs. The work of activism exhausts us and makes us grieve; it takes us from our studios; it makes us scholars, negotiators, combatants, administrators, and business heads when we would prefer to be makers, dreamers, healers, and dancers. And if art is made to serve our activism, it can lose its elemental engagement with the unknown; its freedom to be outrageous, obscure, absurd, and wild; its need to speak the truth as it cannot be spoken in political discourse.

"Asking this question is like asking, Does culture compromise nature? Does love compromise solitude? Does eating compromise prayer? Does the mountain compromise the sky? All of these are relationships of complementarity, correspondence, call-and-response, the mutualistic whole of existence.

"Gathering in Snyder's home place, listening to stories of the Yuba Watershed Institute and the building of the Ring-of-Bone Zendo, and celebrating the poet's work provided a lesson in how radical an act it is in this culture to live a life devoted to something other than capitalism. Yes, we all participate in it. Yes, we are all complicit in environmental degradation and overconsumption simply because of our position in the global food chain. But we can make life choices that nuture more meaningful and sustainable relationships. To live a life devoted to art, to spiritual practice, to service to one's community and ecosystem, restores faith in our collective human enterprise. Work on the culture is work on the self.

"Art can serve activism by teaching an attentiveness to existence and by enriching the culture in which our roots are set down. Culture is both the crop we grow and the soil in which we grow it. And human culture is the most powerful evolutionary force on Earth these days. The grief we feel at abuses of human power is the first positive step at transforming that power for the good. Legislation, information, and instruction cannot effect change at this emotional level -- though they play a significant role. Art is necessary because it gives us a new way of thinking and speaking, shows us what we are and what we have been blind to, and gives us new language and forms in which to see ourselves. To effect profound cultural change requires that we educate ourselves about our own interior wildness that has led us into such a hostile relationship with the forces that sustain us. Work on the self is work on the culture."

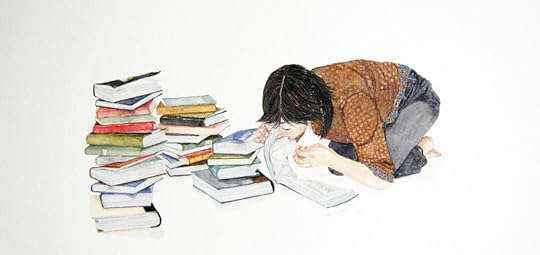

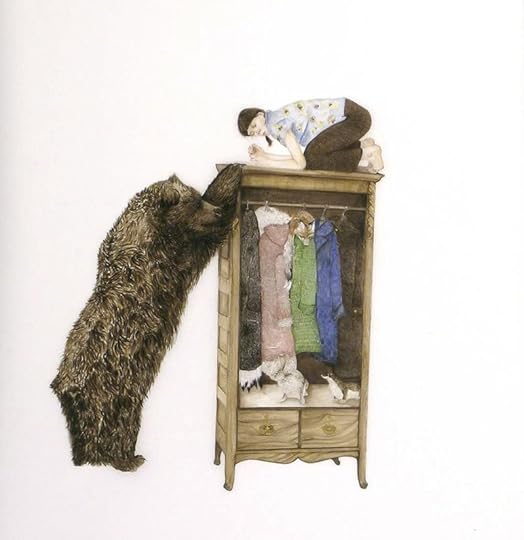

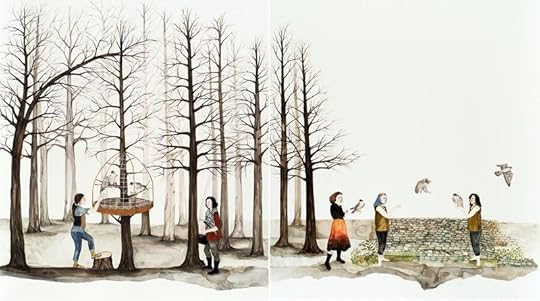

The images in this post are by Canadian artist Kristin Bjornerud, who was born in Alberta, studied at the Universities of Lethbridge and Saskatchewan, and is now based in Montreal.

"My watercolour and gouache paintings," she writes, "explore contemporary political themes, ecological motifs, and personal narratives through the lens of folktales, dreams, and magical realism. In these delicately painted tableaus, a world is revealed wherein dream logic pervades, where women swim with narwhals and vivify hand-knit fauna. These eccentric landscapes are uncanny projections of a possible world where familiar activities are imbued with a mythic quality while, at the same time, extraordinary deeds are carried out with unruffled poise by proud, unconventional heroines.

"My watercolour and gouache paintings," she writes, "explore contemporary political themes, ecological motifs, and personal narratives through the lens of folktales, dreams, and magical realism. In these delicately painted tableaus, a world is revealed wherein dream logic pervades, where women swim with narwhals and vivify hand-knit fauna. These eccentric landscapes are uncanny projections of a possible world where familiar activities are imbued with a mythic quality while, at the same time, extraordinary deeds are carried out with unruffled poise by proud, unconventional heroines.

"My aim is to create contemporary fairy tales that act as a medium through which we may consider our ethical obligations to the natural world and to each other. Retelling and reshaping stories helps us to understand how we are entangled, where we meet, and how our differences may be viewed as disguises of our sameness."

The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming above is from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (The Credo Series, Milkweed Editions, 20010. All rights to the text and imagery above reserved by the author and artist.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Yesterday was the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II, and so I'm looking at songs of soldiers and the march to war. May we remember the stark lessons of the past.

"War is what happens when language fails." - Margaret Atwood

Above: "Solider, Soldier" performed by The Witches of Elswick (Becky Stockwell, Gillian Tolfrey, Bryony Griffith, and Fay Hield), from their debut album Out of Bed (2003). The lyrics are from a poem by Rudyard Kipling; the music is by Peter Bellamy.

"Crow on the Cradle" peformed by Lady Maisery (Hazel Askew, Hannah James, and Rowan Rheingans), from their second album Mayday (2013). The lyrics are attributed to Sydney Carter, adapted from an old folk song.

Above: "High Germany" performed by Tell Tale Tusk (Fiona Fey, Laura Inskip, Reyhan Yusuf, and Anna Lowenstein) at Sofar London, 2017.

Below: "Johnny Has Gone for a Soldier" performed by Muireann Nic Amhlaoibh, from her album Foxglove & Fuschia (2017)

Above: "The Gamekeeper" by Show of Hands (Steve Knightley, Phil Beer, and Miranda Sykes), from here in Devon. This very beautiful song, about a Dartmoor gamekeeper sent to the trenches of World War I, appears on their album Centenary (2016).

Below: "Cable Street" by The Young'uns (Sean Cooney, David Eagle, and Michael Hughes), from their album The Ballad of Johnny Longstaff (2019). It's a song about our elders' great fight against facism, here in England as well as on the continent. How disheartening that we must do it again....

And one more song to end with, above: The Young'uns sing Billy Bragg's "Between the Wars" at the Folk Alliance International Conference, 2015.

Trouble times, says Toni Morrison, are "precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal."

August 31, 2019

Giving voice to the voiceless

For those of us who care about what's going on in the world politically and environmentally, it can be a struggle to understand how this relates to making art, particularly if we work in mythic, nonrealist forms far removed from the increasingly worrisome headlines of the day.

In her lovely little book Writing the Sacred Into the Real, American poet and essayist Alison Hawthorne Deming discusses the tension between art and activism in her work; and although she's speaking in terms of poetry here, her insights can be applied to the writing of fantasy as well...at least to the kind of poetic, deeply mythic fantasy that rarely appears on the bestsellers list, by writers like Alan Garner, Robert Holdstock, Patricia McKillip, Elizabeth Knox, and so many others (including some of you reading this now).

Writing poetry, says Deming,

"is an act of dissent in at least three ways: economically, because the poet labors to make a thing that will never be worth money; temporally, because the poem is an argument with the erosive passage of time; and politically, because in an age that values aggregate data, poetry -- all true art -- insists on the passionate importance of the individual.

"The turning inwards to explore the world through the lens of subject does not necessarily mean a turning away from the world. Denise Levertov turned Wordsworth's lament inside out by writing 'the world is / not with us enough.' Her poetics insisted upon both the lyric impulse -- the song of the soul singing in the present moment -- and the political impulse -- the cry for social justice and peace."

Although Levertov's poetic spirit infuses Deming's, she notes that striving to honour these two opposing impulses can cause chronic psychic whiplash:

"Just when attention is focused on the inner excitement of consciousness, the world calls you a solipsist and demands your attention. Try to tell the world what you think of it, and consciousness will insist that it -- consciousness itself -- is the only thing you can know in its passing, so you had better take heed, right now. But Levertov found balance in the meditative mode, which asks for both introspection and realism -- or as Muriel Rukeyser suggested, the meeting of consciousness and the world -- and she wove a tenuous unity out of condradictions. I take that lesson to heart.

"For me, the natural world in all its evolutionary splendor is a revelation of the divine -- the inviolable matrix of cause and effect that reveals itself to us in what we cannot control or manipulate no matter how pervasive our meddling. This is the reason that our technological mastery of nature will always remain flawed. The matrix is more complex than our intelligence. We may control a part, but the whole body of nature must incorporate the change, and we are not capable of anticipating how it will do so. We will always be humble before nature, even as we destroy it. And to diminish nature beyond its capacity to restore itself, as our culture seems perversely bent to do, is to desecrate the sacred force of Earth to which we owe a gentler hand. That the diminishment has been caused by abuses of human power makes this issue political. Why should one species have the right to deprive so many others of their biological heritage and future? To write about nature, to record the magnificence, cruelty, and mysteriousness of it, is then an act both spiritual and political.

"Italo Calvino describes how literature's interior explorations can be put to political use: 'Literature is necessary to politics above all when it gives voice to whatever is without a voice, when it gives a name to what as yet has no name, especially to what the politics of language excludes or attempts to exclude. I mean aspects, situations, and languages both of the outer and of the inner world, the tendencies repressed both in individuals and in society. Literature is like an ear that can hear things beyond the understanding of the language of politics; it is like an eye that can see beyond the color spectrum perceived by politics. Simply because of the solitary individualism of his work, the writer may happen to explore areas that no one has explored before, within himself or outside, and to make discoveries that sooner or later turn out to be vital areas of collective awareness.'

"My early interests as a poet were to understand the modernist and postmodernist traditions, and to locate myself within their trajectory. And these conditions set aesthetic concerns in opposition to social ones -- the artist as rebel, dissident, and iconoclast. But the wellspring for that inconoclastic energy was for me the belief that art can be a voice of moral and spiritual empathy, an antidote to the cold-hearted self-interest that drives so much of American culture. I have a hunger / for harmony that I feel with dissent.

"Realizing the importance of nature as a subject was a slow process of conversion for me. Way stations along the route: hearing Richard Nelson speak about writing his beautiful meditative book The Island Within after decades of working as a cultural anthropologist and his explaining that he had decided to write about what he loved; hearing Stanley Kunitz say to Fellows at the Work Center that originality in art could come only from what was unique in one's character and experience, not from manipulating the surface of one's technique; remembering that all my life I have hungered for wild places and all of my life wild places have fed me and that this is central to who I am and would have to inform my aesthetic decisions; sitting up in bed as a child, darkness surrounding me, and staring at the mystery of how I came to exist in the world in this body, and how it is an impossible fact that I will one day stop being here; assessing what I most love about being here and what I would like to understand and contribute before leaving."

"I write," says Terry Tempest Williams,

"to make peace with the things I cannot control. I write to create red in a world that often appears black and white. I write to discover. I write to uncover. I write to meet my ghosts. I write to begin a dialogue. I write to imagine things differently and in imagining things differently perhaps the world will change. I write to honor beauty. I write to correspond with my friends. I write as a daily act of improvisation. I write because it creates my composure. I write against power and for democracy. I write myself out of my nightmares and into my dreams. I write in a solitude born out of community. I write to the questions that shatter my sleep. I write to the answers that keep me complacent. I write to remember. I write to forget.... I write as ritual. I write because I am not employable. I write out of my inconsistencies. I write because then I do not have to speak. I write with the colors of memory. I write as a witness to what I have seen. I write as a witness to what I imagine.... I write because it is dangerous, a bloody risk, like love, to form the words, to say the words, to touch the source, to be touched, to reveal how vulnerable we are, how transient we are. I write as though I am whispering in the ear of the one I love."

Can we write fantasy and mythic fiction in this manner as well? Fantasy as ritual, fantasy as witness, fantasy that gives "voice to the voiceless" -- including the whispering more-than-human voices of the land we live on? I believe we can. Or at least I intend to try, and to see where it might take me....

The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming above is from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (The Credo Series, Milkweed Editions, 2010). The passage by Terry Tempest Williams is from Red: Passion and Patience in the Desert (Pantheon, 2001). The poem by Denise Levetov in the picture captions is from O Taste and See (New Directions, 1964). All rights reserved by the authors. The drawing is John D. Batten's illustration for The Black Bull o' Norroway.

August 30, 2019

Not silence but many voices

During a week of increasing anguish caused by those who govern the UK and US, these four passages from Art Objects by Jeanette Winterson remind me that art-making still matters, in dark times more than ever:

"I had better come clean now and say that I do not believe that art (all art) and beauty are ever separate, nor do I believe that either art or beauty are optional in a sane society. That puts me on the side of what Harold Bloom calls the ecstasy of the privileged moment. Art, all art, as insight, as transformation, as joy. Unlike Harold Bloom, I really believe that human beings can be taught to love what they do not love already and that the privileged moment exists for all of us, if we let it."

"We know that the universe is infinite, expanding and strangely complete, that it lacks nothing we need, but in spite of that knowledge, the tragic paradigm of human life is lack, loss, finality, a primitive doomsaying that has not been repealed by technology or medical science. The arts stand in the way of this doomsaying. Art objects. The nouns become an active force not a collector's item. Art objects.

"The cave wall paintings at Lascaux, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the huge truth of a Picasso, the quieter truth of Vanessa Bell, are part of the art that objects to the lie against life, against the spirit, that is pointless and mean. The message colored through time is not lack, but abundance. Not silence but many voices. Art, all art, is the communication cord that cannot be snapped by indifference or disaster. Against the daily death it does not die."

"Naked I came into the world, but brush strokes cover me, language raises me, music rhythms me. Art is my rod and my staff, my resting place and shield, and not mine only, for art leaves nobody out. Even those from whom art has been stolen away by tyranny, by poverty, begin to make it again. If the arts did not exist, at every moment, someone would begin to create them, in song, out of dust and mud, and although the artifacts might be destroyed, the energy that creates them is not destroyed. If, in the comfortable West, we have chosen to treat such energies with scepticism and contempt, then so much the worse for us."

"Art is not a little bit of evolution that [modern societies] can safely do without. Strictly, art does not belong to our evolutionary pattern at all. It has no biological necessity. Time taken up with it was time lost to hunting, gathering, mating, exploring, building, surviving, thriving. Odd then, that when routine physical threats to ourselves and our kind are no longer a reality, we say we have no time for art.

"If we say that art, all art is no longer relevant to our lives, then we might at least risk the question 'What has happened to our lives?' "

A good question indeed.

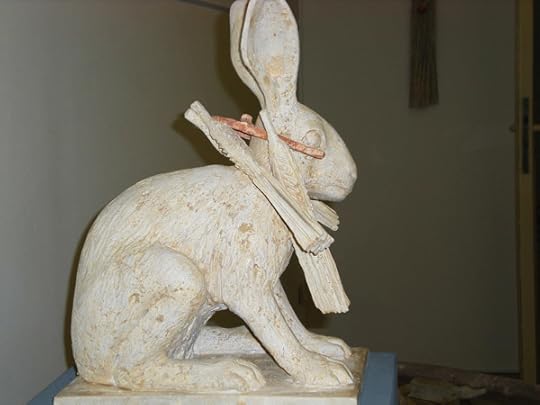

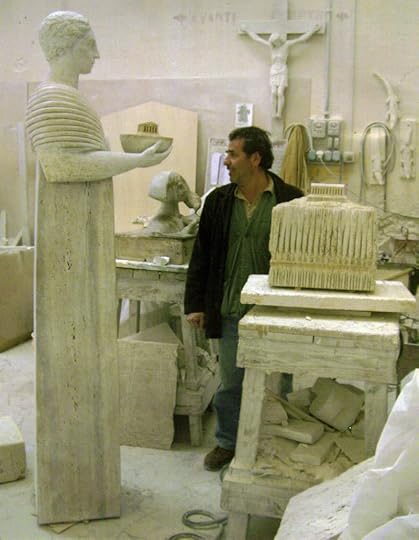

The art today is mythic imagery in marble by Sicilian scuptor Girolamo Ciulla. Born and raised in Caltanisetta, western Sicily, he's now based in Pietrasanta, northern Tuscany, which has been an important center for sculptors working in marble for many centuries.

Sicily, a sun-baked island off Italy's southern coast, has its own language, culture, and ancient tradition of myth, folklore, and fairy tales. This heritage informs every aspect of Ciulla's work, says art historian Beatrice Buscaroli, representing "a continuity with a world that reaches us from the cradle of Mediterranean civilization...to which he adds the magic of the Etruscan land of Pietrasanta."

Ciulla's sculptures, as Buscaroli describes them, are "made of thousand-year-old certainties, of fruit, of sunlight, of wheat and stone, rain and wind. Of generous and vindictive gods, of women and warriors, billy goats and tortoises, of donkeys and fish.... Ciulla's sculpture is a sculpture that lasts, still anchored today to a thousand-year-old wilfullness dedicated to simplicity and beauty, a sculpture that sparks feelings of lightness and familiarity, faith in faces, in animals, in fruits and objects, because they belong to everyday life, and at the same time, to a parallel world, evocative and reassuring, and worthy of being remembered."

The four passages of text by Jeanette Winterson above are from "Art Objects," published in her essay collection of the same name (Jonathan Cape, 1995). The quote by Beatrice Buscaroli is from "Girolamo Cuilla: Being, Lasting" in Girolamo Ciculla (Albermarle Gallery, London, 2007). The photograph of the artist in his studio is from the same publication. All rights to the text and imagery above reserved by the authors and artist.

August 28, 2019

Writing, reading, and the life of the spirit

"I did not go to any school until I was twelve years old," writes English novelist Penelope Lively; "until then, my home-based education centered entirely upon reading -- pretty much anything that came to hand, prose, poetry, good, bad, indifferent, any page was better than no page. At a barbaric boarding school, where the authorities saw a taste for unfettered reading as a sign of latent perversity, I went underground and read furtively, hiding books like other girls hid Mars bars or toffees.

"At university, there was a great swathe of reading, which was fine, but I liked to read off-piste, shooting into English literature, which was not supposed to be my subject, and into areas of history ignored by the syllabus. Grown-up life -- syllabus-free, exam-free -- came as relief; now, there was a day job, but also the opportunity for unbridled reading. I became a public library addict, dropping in several times a week for my fix, and this continued into married life and motherhood, when I read my way through the small branch library of our Swansea suburb, pushing the pram there with a baby in one end and the books in the other.

Lively, of course, went on to become a prolific and celebrated author, winning of the Booker Prize for Moon Tiger and the Carnegie Medal for Children's Literature for The Ghost of Thomas Kemp. She was appointed a Dame of the British Empire for services to literature in 2012. Reflecting on her long career, she notes:

"You write out of experience, and a large part of that experience is the life of the spirit; reading is the liberation into the minds of others. When I was a child, reading released me from my own prosaic world into fabulous antiquity, by way of Andrew Lang's Tales of Troy and Greece; when I was a housebound young mother, I began to read history all over again, but differently, freed from the constraints of a degree course, and I discovered also Henry James, and Ivy Compton-Burnett, and Evelyn Waugh, and Henry Green, and William Golding, and so many others -- and became fascinated by the possibilities of fiction. It seems to me that writing is an extension of reading -- a step that not every obsessive reader is compelled to take, but, for those who do, one that springs from serendipitous reading. Books beget books.

"Would I have become a writer had I been denied books? Plenty of people have done so. Would I have gone on writing in the face of a blizzard of rejection letters? Others have. Unanswerable questions but they prompt speculation. Looking back at that difficult beginning, bashing out a story on typewriter whose keys kept getting stuck together, the endeavor seems precarious indeed."

Everything is fiction, says Irish writer Keith Ridway (in a fine essay for The New Yorker):

"When you tell yourself the story of your life, the story of your day, you edit and rewrite and weave a narrative out of a collection of random experiences and events. Your conversations are fiction. Your friends and loved ones -- they are characters you have created. And your arguments with them are like meetings with an editor -- please, they beseech you, you beseech them, rewrite me. You have a perception of the way things are, and you impose it on your memory, and in this way you think, in the same way that I think, that you are living something that is describable. When of course, what we actually live, what we actually experience -- with our senses and our nerves -- is a vast, absurd, beautiful, ridiculous chaos.

"So I love hearing from people who have no time for fiction. Who read only biographies and popular science. I love hearing about the death of the novel. I love getting lectures about the triviality of fiction, the triviality of making things up. As if that wasn���t what all of us do, all day long, all life long."

Words: The passage by Penelope Lively is from Making It Up (Viking, 2005). The passage by Keith Ridgway is from "Everything is Fiction" (The New Yorker, August 2, 2012). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Late summer in the studio's hillside garden, with flowers, frog pond, a bench under the plum tree, and ripening plums.

Words: The passage by Penelope Lively is from Making It Up (Viking, 2005). The passage by Keith Ridgway is from "Everything is Fiction" (The New Yorker, August 2, 2012). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Late summer in the studio's hillside garden, with flowers, frog pond, a bench under the plum tree, and ripening plums.

August 27, 2019

Writers and readers

"The writer, functioning in a magical medium, an abstract medium, does one half of the work, but the reader does the other," Ben Okri states. "The reader's mind becomes the screen, the place, the era. To a large extent, readers create the world from words, they invent the reality they read. Reading therefore is a co-production between writer and reader. The simplicity of this tool is astounding. So little, yet out of it whole worlds, eras, characters, continents, people never encountered before, people you wouldn't care to sit next to on a train, planets that don't exist, places you've never visited, enigmatic fates, all come to life in the mind, painted into existence by the reader's creative powers. In this way, the creativity of the write calls up the creativity of the reader. Reading is never passive."

Neil Gaiman, too, sees writers and readers as co-creators:

"What we, as authors, give to the reader isn't the story. We don't give them the people or the places or the emotions. What we give the reader is the raw code, a rough pattern, loose architectural plans that they use to build the book themselves. No two readers can or will ever read the same book, because the reader builds the book in collaboration with the author. I don't know if any of you have had the experience of returning to a beloved childhood book. A book that you remember a scene from so vividly, something that was etched onto the back of your eyeballs when you read it, and you remember the rain whipping down, you remember the way the trees blew in the wind, you remember the whinnies and the stamps of the horses as they fled through the forest to the castle, and the jangle of the bits, and every noise. And you go back and read the book as an adult and you discover a sentence that says something like, 'What a jolly awful night this would be,' he said as they rode their horses through the forest. 'I hope we get there soon.' And you realize you did it all. You built it. You made it."

"All sorts of pleasant and intelligent people read my books and write thoughtful letters about them," John Cheever once commented. "I don't know who they are, but they are marvelous and seem to live quite independently of the prejudices of advertising, journalism, and the cranky academic world. The room where I work has a window looking into a wood, and I like to think that these earnest, loveable, and mysterious readers are in there."

Words: The quotes above are from The View From the Cheap Seats: Selected Non-fiction by Neil Gaiman (Headline, 2016); A Way of Being Free by Ben Okri (Head of Zeus, 2015); and John Cheever's page in The Writers' Desk by Jill Krementz (Random House, 1997). The poem in the picture captions is from Halflife by Meghan O'Rourke (WW Norton & Co., 2007). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Meadow, bog, and a few of our nonhuman neighbours, Lower Commons, Chagford.

Wrriters and readers

"The writer, functioning in a magical medium, an abstract medium, does one half of the work, but the reader does the other," Ben Okri states. "The reader's mind becomes the screen, the place, the era. To a large extent, readers create the world from words, they invent the reality they read. Reading therefore is a co-production between writer and reader. The simplicity of this tool is astounding. So little, yet out of it whole worlds, eras, characters, continents, people never encountered before, people you wouldn't care to sit next to on a train, planets that don't exist, places you've never visited, enigmatic fates, all come to life in the mind, painted into existence by the reader's creative powers. In this way, the creativity of the write calls up the creativity of the reader. Reading is never passive."

Neil Gaiman, too, sees writers and readers as co-creators:

"What we, as authors, give to the reader isn't the story. We don't give them the people or the places or the emotions. What we give the reader is the raw code, a rough pattern, loose architectural plans that they use to build the book themselves. No two readers can or will ever read the same book, because the reader builds the book in collaboration with the author. I don't know if any of you have had the experience of returning to a beloved childhood book. A book that you remember a scene from so vividly, something that was etched onto the back of your eyeballs when you read it, and you remember the rain whipping down, you remember the way the trees blew in the wind, you remember the whinnies and the stamps of the horses as they fled through the forest to the castle, and the jangle of the bits, and every noise. And you go back and read the book as an adult and you discover a sentence that says something like, 'What a jolly awful night this would be,' he said as they rode their horses through the forest. 'I hope we get there soon.' And you realize you did it all. You built it. You made it."

"All sorts of pleasant and intelligent people read my books and write thoughtful letters about them," John Cheever once commented. "I don't know who they are, but they are marvelous and seem to live quite independently of the prejudices of advertising, journalism, and the cranky academic world. The room where I work has a window looking into a wood, and I like to think that these earnest, loveable, and mysterious readers are in there."

Words: The quotes above are from The View From the Cheap Seats: Selected Non-fiction by Neil Gaiman (Headline, 2016); A Way of Being Free by Ben Okri (Head of Zeus, 2015); and John Cheever's page in The Writers' Desk by Jill Krementz (Random House, 1997). The poem in the picture captions is from Halflife by Meghan O'Rourke (WW Norton & Co., 2007). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Meadow, bog, and a few of our nonhuman neighbours, Lower Commons, Chagford.

August 23, 2019

Myth & Moor update

Words that are often in my mind these days:

''Let us keep courage and try to be patient and gentle. And let us not mind being eccentric, and make distinction between good and evil.'' - Vincent van Gogh

Have a good weekend everyone -- especially here in the UK, where it's a three-day holiday weekend. May we all find restoration and reconnection in our various ways, and come back with new strength for art-making, community-building, and the good fight for the planet ahead.

Myth & Moor will resume on Tuesday.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers