Terri Windling's Blog, page 50

October 26, 2019

The Fool Report #2

As my Fool of a husband begins his second week working with Jonathan Kay and his merry band of Fools in Finland, here are some pictures snapped on Howard's bicyle commute through the streets of Helsinki each morning and evening.

He reports that the work has been fascinating, challenging, and full of both high points and lows. Last night, Howard's group of Fools-in-training went to see Jonathan's show at the FIC Festival...watching the master Fool perform...and today they were back in the studio, seeking entrance into the archetypal realm for themselves.

Our heartfelt thanks go out to everyone who has helped make Howard's exploration of Foolery possible. The journey is just beginning....

If you'd like to know more about Jonathan Kay's practice and philosophy of Foolery, listen to his discussion of "The Fool, Archetypal Play, and Self-Realisation" with Amisha Ghadiali (July 2019).

Meanwhile, the Funding for Foolery campaign continues. Please help us to keep our own dear Fool on the road: https://gofundme.com/f/q5cuph.

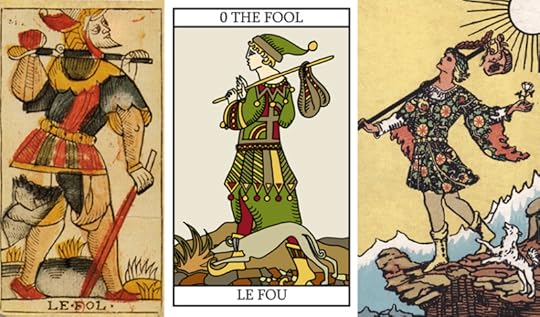

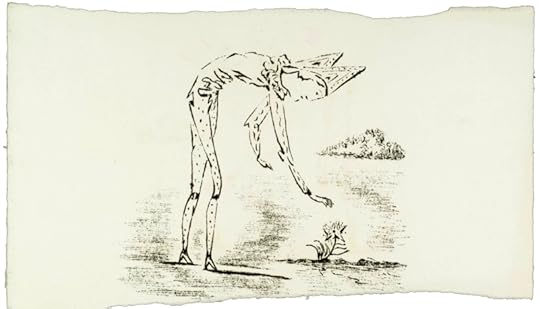

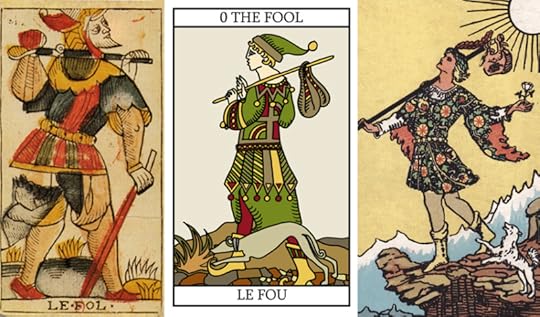

Art above: The fool cards from the Dodal Tarot, Karyn Easton Tarot, and Rider-Waite Tarot. "Fool With a Flower" by the English surrealist painter and printmaker Cecil Collins (1908-1989).

October 25, 2019

Recommended reading

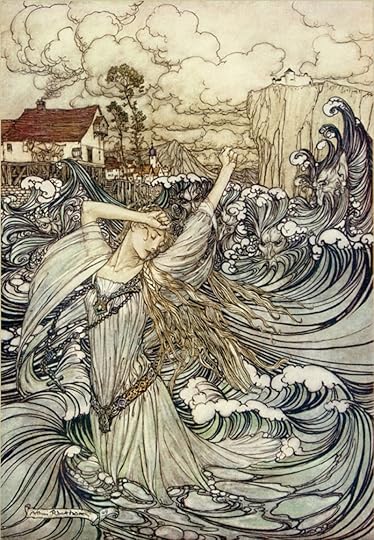

"Mermaids: What and who are they? What do they look like? How are they different from sirens? How are they related to other water beings around the world? What are the cultural, religious, and popular beliefs that sustain specific plots of human���merfolk encounters? Why do we continue to tell stories about eerie mermaids and other water spirits in the 21st century?"

Fairy tale scholar Cristina Bacchilega answers these questions and more in her insightful, beautifully written essay "How Mermaid Stories Illustrate Complex Truths About Being Human," published today on Literary Hub. Please don't miss it.

Art by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) and Helen Stratton (1867-1961).

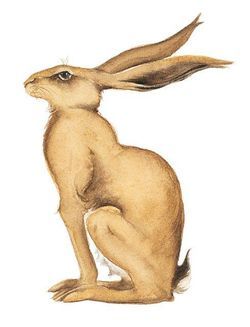

Following the hare....

Here's another folklore post for you in the run-up to Halloween. This time it's on the subject of Witch Hares, a creature more common that you might think....

As my friend Carolyne Larrington observes in her excellent book The Land of the Green Men: "We tend to associate witches with black cats that operate as their familiar spirits, but more traditionally the witch transforms herself into a hare in order to steal milk from the neighbours' cows. The witch-hare has other moneymaking sidelines, however: in one rather jolly tale from Tavistock in Devon, she gives the hare hunters a run for their money. In a letter written in 1833, a certain Mrs. Bray relates how a young boy would would earn money by starting hares for the local hare hunters -- he was always able to find one when they seemed scarce. Somehow, the hare always managed to get away. This made the huntsman suspicious, so on one occasion the hounds were teed up to to get on to their prey's trail more quickly. The hare zigged and zagged to cries from the boy of 'Granny! Quick! Run for your life!' Aha! The hare just made it into the boy's grandmother's cottage through a little hole. When the huntsmen broke in, no animal was to be seen. But the old woman was quite out of breath, and she had scratches as if she had been running through brambles."

As my friend Carolyne Larrington observes in her excellent book The Land of the Green Men: "We tend to associate witches with black cats that operate as their familiar spirits, but more traditionally the witch transforms herself into a hare in order to steal milk from the neighbours' cows. The witch-hare has other moneymaking sidelines, however: in one rather jolly tale from Tavistock in Devon, she gives the hare hunters a run for their money. In a letter written in 1833, a certain Mrs. Bray relates how a young boy would would earn money by starting hares for the local hare hunters -- he was always able to find one when they seemed scarce. Somehow, the hare always managed to get away. This made the huntsman suspicious, so on one occasion the hounds were teed up to to get on to their prey's trail more quickly. The hare zigged and zagged to cries from the boy of 'Granny! Quick! Run for your life!' Aha! The hare just made it into the boy's grandmother's cottage through a little hole. When the huntsmen broke in, no animal was to be seen. But the old woman was quite out of breath, and she had scratches as if she had been running through brambles."

Why, asks Carolyne, are there so many stories of witches in the shape of hares all across the British Isles?

"They were familiar animals before the industrialisation of the countryside," she notes, "and their habit of rearing up on their hind legs and their distinctive zigzag run made them easy to pick out. They are swift and clever -- which explains how they always manage to get back to the witches' houses before they  are caught -- and the have long been indigenous to the British landscape. Hares thus appear in a good deal of folklore across the country....I've seen hares myself near where I live in North Oxfordshire, up by the Roman road that runs along the southern side of Madmarston Hill near Swalcliffe: two big beasts on their hind legs, boxing away at one another like a couple of prizefighters, until they spotted me and the dog. Then they swerved away over the stubbly March fields, only to take up their bout again at a more distant corner. These hares were probably a male/female pair, rather than rival males duking it out: the female was trying the repel the male's advances, with limited success."

are caught -- and the have long been indigenous to the British landscape. Hares thus appear in a good deal of folklore across the country....I've seen hares myself near where I live in North Oxfordshire, up by the Roman road that runs along the southern side of Madmarston Hill near Swalcliffe: two big beasts on their hind legs, boxing away at one another like a couple of prizefighters, until they spotted me and the dog. Then they swerved away over the stubbly March fields, only to take up their bout again at a more distant corner. These hares were probably a male/female pair, rather than rival males duking it out: the female was trying the repel the male's advances, with limited success."

Hares are sometimes seen to gather together in what looks like a convocation, says Carolyne, "eight or ten of them sitting in a circle and gazing at one another as if in silent communication. The writer Justine Picardi mentions seeing just such a phenomenon in June 2012 in the Scottish highlands:

" 'On the way here last night, a magical scene: glimpsed in a field beside the lane, a circle of hares, all gazing inward, motionless in the moment that we passed. I've heard occasional stories of these rarely witnessed gatherings -- but never seen one for myself. No camera to hand -- although if we'd stopped, I'm sure the hares would have vanished -- yet a sight impossible to forget.'

"But we know of course that these were no ordinary hares, but surely a gathering of witches in hare form."

If you'd like to know more about about hares in legend and natural history, I recommend The Leaping Hare by George Ewart Evans & David Thomson and Hare by Simon Carnell (published as part of Reaktion's "Animal" series). Another one to seek out is The Hare Book, edited by Jane Russ for The Hare Preservation Trust (UK), which is a delightful and informative compilation of stories and facts about hares accompanied by photographs and art -- including contributions from Jackie Morris, Virginia Lee, and Hannah Willow. (I particularly recommend Jackie's story in the book, "The Old Hare in Spring: 1502," inspired by the art of Albrecht D��rer, and the charming true-life tale of the three hares beloved by the 18th century poet William Cowper.)

You'll find more magical hares in my previous post "The Folklore of Rabbits and Hares" -- as well as some Witch Hares leaping through a post on Devon folklore: "Tales of a Half-Tamed Land." Devon is a veritable hotbed of shape-shifting hares, so be wary if you're out after dark here....

The gorgeous hare art in this post is by Jackie Morris, one of the finest painters of hares (and other animals) working today. To view more of her work, please visit Jackie's website and seek out her beautiful books, including The Lost Words, The House Without Windows, and Song of the Golden Hare.

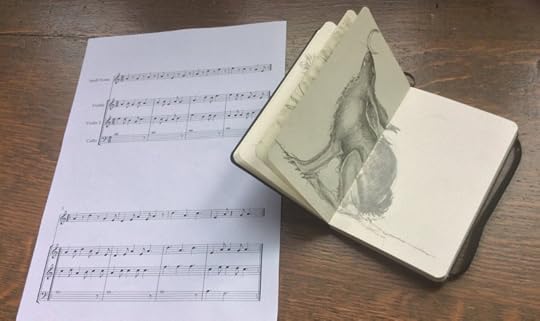

Both Carolyne and Jackie were colleagues of mine on the year-long Modern Fairies project, where the final concert included a gorgeous song by Fay Hield about a shape-shifting hare based on the witch trials of Isobel Gowdie. Fay's music and Jackie's sketch for the song are pictured below.

Words & pictures: The quote by Carolyne Larrington is from The Land of the Green Men: A Journey Through the Supernatural Landscape of the British Isles (I.B.Taurus & Co., 2015). The quotes in the picture captions are from The Hare Book edited by Jane Russ (The Hare Preservation Trust/ Graffeg Books, 2014) and Common Ground by Rob Cowen (Windmill Books, 2016). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and artist.

Further reading: Previous post on Jackie Morris' marvelous work include The wild sky, Making friends with monsters, & Spells Songs.

October 23, 2019

The Wild Hunt

In honour of the "monsters" theme on Folklore Thursday this week....

The approach to Halloween is a time for telling stories of ghosts, ghouls, and the Unseelie Court (the underside of the Faerie Realm), and for paying wary respect to the Dark Gods of the land as we move into the dark months of the year.

One of the more frightening tales of Dartmoor is the legend of the Wild Hunt, which thunders across the moors by night in pursuit of any man or beast foolish enough to cross its path.

One of the more frightening tales of Dartmoor is the legend of the Wild Hunt, which thunders across the moors by night in pursuit of any man or beast foolish enough to cross its path.

"Stay indoors, attend your hearths," warn Ari Berk & William Spytma in an excellent article on the Hunt. "Try to keep the night at bay by the telling of your tongue. Remember your kin, honor your ancestors. For at this time the dead begin to stir, riding upon hallowed and familiar roads, galloping through villages and wastes, flying through the forests of the mind. Such raids are reminders that the past is not a dead thing, but may return, like a hunter, to follow us for a time."

The Wild Hunt, they explain, "is ancient in origin, an embodiment of the memories of war, agricultural myth, ancestral worship, and royal pastime. Its most complete and well-documented traditions lie with the peoples of Northern Europe; however, there are reflections of the Hunt anywhere in literature or folk tradition where the dead travel together over the land, or heroes rise up to rout a foreign foe, or where representatives of the sovereignty of the land are pursued and hunted. We even find versions of the Hunt in Ovid and the classical tradition. Indeed, wherever there are tales of invasions, we will likely find stories of a ghostly hunt following close on the heels of myth or history....

'Regardless of their regional names, all Hunts seem to share several common features wherever they appear: a spectral leader, a following train, announcement by a great baying of hounds, crashes of lightning, and loud hoof beats along with the Huntsman's shouts of 'Halloo!' Death and war often follow in their wake."

The Hunt is led by a variety of figures, depending on where the tale is told: Odin, Woden, Herla, Herne the Hunter, Dewer, the Devil, Gwynn Ap Nudd (the king of the Welsh Otherworld), and even King Arthur under a curse. Whatever his guise, the Huntsman rides with hunting hounds that are just as fearsome as he: usually black as night, with eyes like glowing coals and breath of flame.

In The Folklore of Dartmoor, Ralph Whitlock reports on the Hunt that runs on the open moor near Chagford: "Sabine Baring-Gould says that in old times the Wild Hunt was known locally as the Wist Hounds. J.R.W. Coxhead has heard them called Yeth Hounds or Heath Hounds. He writes: 'The sound of the Dark Huntsman's horn and the fierce cries of the Yeth Hounds are supposed to have been heard many times in the lonely parts of the moor by belated travelers, and by resident inhabitants of the Dartmoor area. It is said that two of the favorite haunts of the spectral huntsman and his pack of demon hounds are Wistman's Wood and the Dewerstone Rock.' He adds that when, on a stormy night in 1677, Sir Richard Cabell, lord of the manor of Brook in Buckfastleigh parish, died, the Demon Hunt raged around the house all night, waiting for the soul of the wicked knight."

"These black, spectral hounds bear almost as many names as the Hunt," note Berk & Spytma. "In the North they are called Gabriel's Hounds. In Lancashire they are described as monstrous dogs with human heads who foretell of coming death or misfortune. In Devon they are known as Yeth, Heath, or Wisht hounds. These hounds issue from inside Wistman's Wood on the eve of St. John (Midsummer), a night when by tradition the careful eye can see the spirits of the dead fly from their graves. Here, among the ancient dwarf oaks and greening stones, Dewer (the Devil), kennels his hounds, and it is still said that no real dog will enter these woods at any time of the year. The Yeth hounds are also associated with the souls of unbaptized children, which they chase across the moor as their prey. But related traditions hold that the dogs are themselves the souls of the unbaptized babes, and they instead chase the Devil across the moor in repayment for his hand in their fate.

"These black, spectral hounds bear almost as many names as the Hunt," note Berk & Spytma. "In the North they are called Gabriel's Hounds. In Lancashire they are described as monstrous dogs with human heads who foretell of coming death or misfortune. In Devon they are known as Yeth, Heath, or Wisht hounds. These hounds issue from inside Wistman's Wood on the eve of St. John (Midsummer), a night when by tradition the careful eye can see the spirits of the dead fly from their graves. Here, among the ancient dwarf oaks and greening stones, Dewer (the Devil), kennels his hounds, and it is still said that no real dog will enter these woods at any time of the year. The Yeth hounds are also associated with the souls of unbaptized children, which they chase across the moor as their prey. But related traditions hold that the dogs are themselves the souls of the unbaptized babes, and they instead chase the Devil across the moor in repayment for his hand in their fate.

"In Wales the dogs are the Cwn Annwn (Hounds of the Otherworld) often white with red ears and bellies. The corrupt priest Dando had his own beasts, called the Devil's Dandy Dogs. Great black hounds were known as the Norfolk Shuck and Suffolk Shuck. The Hounds of the Hunt all bear a striking resemblance to the 'Black Shuck,' a solitary creature that has stalked East Anglia for centuries with fiery eyes as big as saucers. In England such solitary dogs are often the ghosts of deceased people, changed as punishment, and will sometimes help people if treated kindly.

"In several Norse versions of the Hunt, the Huntsman would leave a small black dog behind. The dog had to be kept and carefully tended for a year unless it could be driven away. The only known way to get frighten it away was to boil beer in eggshells, a curious ritual act seemingly related to the traditional method of getting rid of a Faerie changeling."

Faeries, too, have their form of Hunt: the Host, a group from the Unseelie Court, swarms through the skies on cold, moonless nights, snatching up mortals who cross their path and whisking them into the dark. If their victims live to limp back home, they report being forced to making mischief on other mortals and to raid faery cattle from the Seelie Realm. Shaken and battered, those hunted by the Host are said to age years in a single night.

If you'd like to learn more about the Wild Hunt -- and it would be wise to do so at this chancy time of year -- I recommend reading Berk & Spytma's fascinating article in full. You'll find it here.

"The Wild Hunt Rides Over Paris," a post by Katherine Langrish (on Seven Miles of Steel Thistles), is also a treat, as is Carolyne Larrington's book: In the Land of the Green Men, Penelope Lively's YA novel based on the theme: The Wild Hunt of Hagworthy, and Jane Yolen's middle-grade novel: The Wild Hunt, illustrated by Mora Francisco.

Pictures: The drawing above is by my friend & Dartmoor neighbor Alan Lee, who knows a thing or two about Wild Hunt legends. It's from his book Faeries, a collaboration with Brian Froud. Descriptions and photographer credits for the Dartmoor photographs can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Words: The passages quoted above are from "Power, Penance, & Pursuite: On the Train of the Wild Hunt by Ari Berk & William Spytma (Realms of Fantasy, 2002) and Devon Folklore by Ralph Whitlock (BT Batsford, 1977). All rights reserved by the authors.

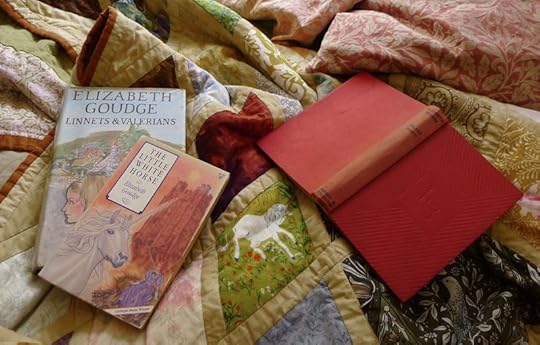

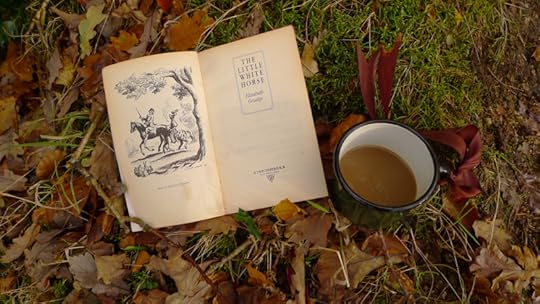

Moonacre Manor

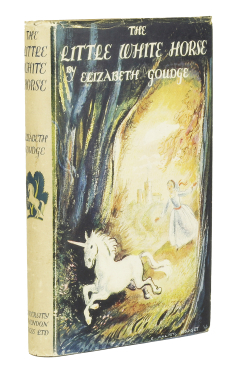

One of my favourite books in the world is The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge, written in 1946 and set in a magical version of Devon. I dearly wish I'd known it when I was young, for Goudge's brand of magic (gentle, wind-swept and rain-kissed) would have perfectly suited the child I was. Instead I read it three years ago, fell entirely under its spell, and then spent a whole winter devouring all of her other books for both kids and adults. (I was sick in bed for some of those months, and Goudge was the perfect companion.)

One of my favourite books in the world is The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge, written in 1946 and set in a magical version of Devon. I dearly wish I'd known it when I was young, for Goudge's brand of magic (gentle, wind-swept and rain-kissed) would have perfectly suited the child I was. Instead I read it three years ago, fell entirely under its spell, and then spent a whole winter devouring all of her other books for both kids and adults. (I was sick in bed for some of those months, and Goudge was the perfect companion.)

In an excellent essay on Goudge, Kari Sperring writes:

"With the exception of her children���s books, most of her work is not what most people would think of as fantasy. The children���s books are all set in a version of our real world, too, though her towns and landscapes in them are imaginary. Yet in all her work the boundaries between worlds are thin. Folklore and poetry, transcendent experience, and glimpses of the immanent pervade them, and her characters -- especially the youngest and the oldest -- slip between these worlds easily. Her characters channel folktales and legend through their lives and their connections with others.

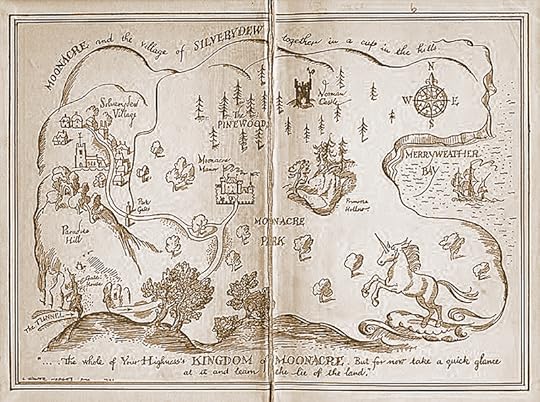

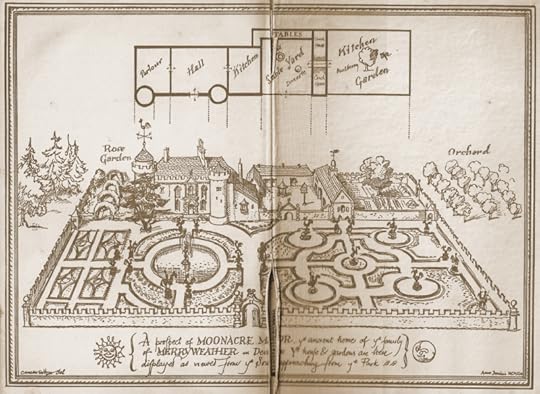

"This is most clear in her children���s books, in particular, her three best known -- The Little White Horse, Henrietta���s House, and Linnets and Valerians (recently retitled The Runaways). In TLWH, which is the most directly fantastical of Goudge���s books, the protagonist Maria must explore the history of her family and their ancestral home via a blend of fact and magic -- the injustices done by her forefather Sir Hrolf were real enough, but their context and consequences belong as much to the realm of magic and the liminal as to reality. A white horse and a giant dog come and go throughout the history of her family -- and her own experience -- guiding, observing, and sometimes leading Maria to the discoveries she needs to make. The dog -- another Hrolf -- is real enough but seemingly immortal, but the horse is a unicorn and a creature of the sea and not to be grasped or owned. The story sounds soppy, and the recent film (titled The Secret of Moonacre) tried hard to make it soppy by replacing the very real magic of Goudge���s writing with sentiment and gloss, but in the book, it is not. Rather, everything is tied together by extra-mundane bonds, so that Maria���s friend and ally, Robin, is at first a boy in dreams who becomes real, and the white horse brings not only Maria but the book���s main antagonist to a solution to the ancient problem they face that is partly realistic, yes, but rooted in liminal experience."

Elizabeth de Beauchamp Goudge was born in 1900 in the cathedral city of Wells, where her father was a clergyman and theological scholar. His career took the family to Ely and Oxford (two cities she loved and would later write about) -- but his early death meant the loss of their Oxford home and sudden impecunity. Reeling from the loss, Elizabeth's semi-invalid mother announced they would take a month's holiday in Devon. Her elderly Nanny, now a permanent part of the family, was to come along too. In her autobiography, Elizabeth writes:

"Devon? Why Devon? We knew no one there and where could we stay? But my mother had seen an advertisement in the paper. A small wooden bungalow could be cheaply rented for a summer holiday at a village called Marldon, and she was quite certain that was where we must go. So Nanny and I dragged ourselves out of the ooze of our exhaustion and we set off, driven by a friend who had a large comfortable car and said he knew the way. More or less he did and very late in the afternoon we found the wooden bungalow and inside it our unknown landlady, who kept a guest-house next door, had lit a glowing fire.

"For it was what those who do not love Devon call 'a typical Devon day'; that is to say it was raining, that steady relentless rain that lifted the Ark about the primeval flood, and at the same time, since the day was windless, a thick mist covered the earth. We could know nothing of our surroundings except that the bungalow seemed poised upon the summit of a hill and that its wooden walls did not look very weather-proof.

"It was felt that food would be reassuring and Nanny and I began quickly getting some sort of meal together, but the friend who had brought us down took me away from the preparations for a few moments to the western-facing window. 'Look,' he said, 'what do you think is out there?' The downpour was slackening at last and no longer drummed on the roof. A small wet green lawn sloped from the window and appeared to fall into the mist as though it was green water sliding over the edge of a precipice. We could see nothing through the mist yet we were aware that behind it was the westering sun, and also it seemed to fill a deep valley and rising beyond the valley was -- what? 'Something grand,' said our friend. 'You'll know in the morning.' A tremor went through me, and I think through him too, for we seemed to be sharing one of those inexplicable moments of expectation and intimation that come sometimes when a small earthly mystery seems to be speaking of a mystery beyond itself.

"I was woken the next morning by a sound I had not heard for a long time, a cock crowing in the garden, across the lane, eastward where the sun would soon be rising. Had the mist lifted? When later I pulled the curtains it was still there, but the morning sun was shining through it and turning it to gold, and every bush and tree that lined the lane was glistening with diamond drops.

"It was what lovers of Devon call 'a typical Devon day,' that is to say, a morning of clear shining after rain. Because of the slope of the land the hill seemed higher than it actually was; it seemed high as Ararat, with the wooden bungalow perched like the Ark on its summit. The valley below was even wider and deeper than I had realized the night before and it seemed to hold every beauty that a pastoral Devon valley knows, woods and farms and orchards, green slopes where sheep were grazing, fields of black and white cows, and where there were fields of tilled earth it was the crimson of the earth of South Devon and looked like a field of flowers. And along the eastern horizon lay the range of blue hills called Dartmoor.

"I felt I had come home. I have never felt so deeply rooted anywhere as I was in the earth of Devon. Or rather I did not so much put roots down as find roots that were already there. And yet I had not been born in Devon, I had been born over the border in Somerset. I could not understand it then and I do not understand it now. The only tremor was the realization that in a few weeks time we should have to leave this earthly paradise."

But in fact, they did not leave. World War II began and the family stayed in Marldon -- where Elizabeth lived for the next twelve years. She wrote some of her best books there, paying the bills with the steady work of her pen. A deep love of Devon shines through every single page of The Little White Horse...as well as through Linnets and Valerians, and her quietly beautiful adult novel The Rosemary Tree.

The village of Marldon is not far away from us, just on the other side of the moor, so I wanted to go see those hills for myself -- especially since learning that Moonacre Manor, the enchanted setting of The Little White Horse, was inspired by Compton Castle: an old manor house in Marldon parish. South Devon has changed since Elizabeth's day; it's now less remote, more heavily populated, but still full of orchards, woodlands, and farms, and Marldon itself has retained its old charm. I wanted to see the lanes she once walked, the bungalow where she lived, and her old village church. I especially wanted to see Compton Castle, now a National Trust property.

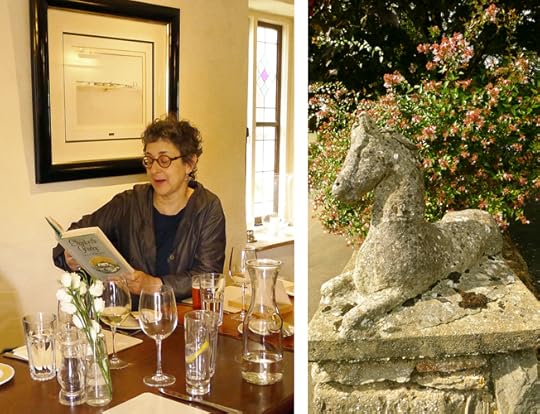

I finally made the journey last year at this time, as autumn colored the hedgerows and fields, in the company of four other writers who also love Goudge: Delia Sherman, Ellen Kushner, Liz Williams and Veronica Williams. We started with lunch at Marldon's Church House Inn, where Ellen read us some relevant passages from Goudge's autobiography...

...and then made our way through the winding lanes to the gates of "Moonacre Manor."

Comptom Castle, a fortified manor house, was the seat of Sir Maurice de la Pole during the reign of King Henry II. It passed into the de Compton family, and then, through marriage, to the Gilbert family. The house was enlarged in the mid-14th century, fortified in 1520, and then sold in 1785 -- after which, in the 18th and 19th centuries, it fell into ruin. A descendant of the Gilbert family bought the property in 1931, began the castle's restoration, and then gave it to the National Trust -- on condition that the family would continue to occupy the house, which they do to this day.

Compton Castle is considerably smaller than Moonacre Manor in The Little White Horse -- but the soaring main hall, the kitchen gardens, the orchard full of vivid red apples and the emerald-green hills full of fleecy white sheep, all hold the magic she drew upon to create her timeless story.

We were thrilled to discover a kitchen well just like the one at Moonacre Manor. Sitting beside it, I could almost believe that Goudge's story was real after all, and Serena the hare would come tumbling over the grass, followed by noble Hrolf.

(Her talent for creating distinctive animal characters was second to none.)

In a recent essay for Slightly Foxed, Victoria Neuman has this to say about Goudge and her work:

"Whether she is describing a young child climbing over slippery rock steps from a sea cave or uncovering the glories of a tangled garden in Devon, she is one of the only modern prose writers to capture the spirit of the 17th-century mystic Thomas Traherne:

"'The corn was orient and immortal wheat, which should never be reaped, nor was ever sown. I thought it had stood from everlasting to everlasting. The dust and stones of the street were as precious as gold: the gates were at first the end of the world. The green trees when I saw them first through one of the gates transported and ravished me, their sweetness and unusual beauty made my heart to leap, and almost mad with ecstasy, they were such strange and wonderful things...'

"Like Trahern Goudge was an ardent Anglican. But although religion can be an oppressive presence in her adult novels, in her children's books it manifests itself merely as a sense of embracing safety. One of her obituaries quoted Jane Austen's famous line from Mansfield Park, 'Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery.' Her fictional world is devoid of malice...Loyalty, kindness, affection, the wonder of nature, the smells of good, plain English cooking, a hot bath and clean clothes, the appealing personalities of pets: these are the things she celebrates. In Goudge's children's books, to use Louise MacNeice's phrase, there is 'sunlight on the garden' and the equation always comes out."

I should note that unlike Neuman I don't feel oppressed by the Anglican threads within Goudge's work. As the daughter of a clergyman, she was writing about the world she knew best. I enter it as I do any other unknown culture, trusting the writer as my guide, and her generous, mystical, nature-based version of Christianity allows even a wooly old pagan like me to feel welcome within her tales. Goudge, as Kari Sperring writes, "never preaches, nor lays out moral parameters, and, to paraphrase Louisa Alcott, she does not reward the 'good' with gilded treats and the 'bad' with dire punishments. Indeed, I���m not sure she deals in good and bad at all: she writes rather about compassion and understanding and resolution through empathy. Her work is not showy and it is not melodramatic. It is, however, often surprising and sometimes startling. And she rarely if ever does what the reader expects."

"As the world becomes increasingly ugly, callous, and materialistic," Goudge once wrote, "it needs to be reminded that the old fairy stories are rooted in truth, that imagination is of value, that happy endings do, in fact, occur, and that the blue spring mist that makes an ugly street look beautiful is just as real a thing as the street itself."

That statement sums up why I love Elizabeth Goudge, and why I continue to read and re-read her. She, too, believes beauty is vital in a troubled world, and the promise of hope. Her work is old-fashioned, quiet, and slow. I say this without apology, for these qualities have genuine literary value in an our loud, aggressive, and fast-paced culture.

If you'd like to read more about Goudge's life in Devon, here are two previous posts on the subject: A Sense of Otherness and The Magic of Moor and Hill. To learn more about Compton Castle, go here. (You can even stay overnight at the castle, in its charming Watch Tower.) To learn more about the author's life and work, visit the Elizabeth Goudge Society. Or better still, go read her marvelous books if you haven't already.

Words: The text quoted above is from "Elizabeth Goudge: Glimsping the Liminal" by Kari Sperring (Strange Horizons, February 22, 2016), The Joy of Snow: An Autobiography by Elizabeth Goudge (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974), and "In Search of Unicorns" by Victoria Neumark (Slightly Foxed, Winter 2018), all of which I recommend. A good biography of Goudge has yet to be published. (Beyond the Snow by Christine Rawlings is not a biography but a collection of excerpts from Goudge's work interspersed with biographical reflections.) Pictures: Marldon and Compton Castle, South Devon, November 2018; with thanks to my lovely companions on the journey.

October 21, 2019

Tales for a Tuesday Morning

I'm working on a new post for you -- but it's turning into a long one, so please check back tomorrow morning. It's about... Well, I'm not going to tell you, but here's a clue:

"In times of storm and tempest, of indecision and desolation, a book already known and loved makes better reading than something new and untried...nothing is so warming and companionable.��� - Elizabeth Goudge

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm starting the week with music from the beautiful, troubled, complicated country I was raised in and still love....

Above: "The Line Between" by the English/American roots duo Son of Town Hall (Ben Parker and David Berkeley), from their fine new album The Adventures of Son of Town Hall. I love these guys and hope the new album brings them more attention on both sides of the Atlantic.

Below: "Morning Fields" by Son of Town Hall, recorded at a Studio Session last year.

Above: "Down in the Water" by Mipso (Wood Robinson, Libby Rodenbough, Jacob Sharp, Joseph Terrell), an American roots quartet from North Carolina. This performance was filmed in Saxapahaw, NC, in 2016.

Below: "My Burder With Me" by Mipso, performed in New York City in 2017.

Above: "Scrape Me Off the Ceiling" by The Steel Wheels (Eric Brubaker, Brian Dikel, Kevin Joaquin Garcia, Jay Lapp, Trent Wagler), an American roots group from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. The song is from their album Wild As We Came Here (2017).

Below: "February Seven," an old favorite from The Avett Brothers (Scott Avett, Seth Avett, Bob Crawford, Joe Kwon), from Concord, North Carolina. I love the underlying theme of this video: examining the process of songwriting (or another kind of creative work), and reminding me of this advice for writers from Hilary Mantel:

"If you get stuck, get away from your desk. Take a walk, take a bath, go to sleep, make a pie, draw, listen to ��music, meditate, exercise; whatever you do, don't just stick there scowling at the problem. But don't make telephone calls or go to a party; if you do, other people's words will pour in where your lost words should be. Open a gap for them, create a space. Be patient."

And one more to end with, below: "Marching On" a song of hope and persistence during these difficult times by Phoebe Hunt & the Gatherers, from Austin, Texas.

March on, everyone. March on.

The art today is by the great American painter Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009).

October 19, 2019

Wild Sanctuary

Jungian scholar Marie-Louise von Franz saw the fairy tale forest not only as a place of trials for the hero, but also an archetypal setting for retreat, reflection, and healing. In a lecture presented to the C.G. Jung Institute in Switzerland in the winter of 1958-59 (subsequently published as The Feminine in Fairytales), she looked at the role of the forest in the story of "The Handless Maiden" (also known as "The Armless Maiden," "The Girl Without Hands," and "Silver Hands"). In this tale, a miller's daughter loses her hands as the result of a foolish bargain her father has made with the devil. (In darker variants, it is because she will not give in to incestuous demands.) She then leaves home, makes her way through the forest, and ends up foraging for pears (a fruit symbolic of female strength) in the garden of a tender-hearted king ��� who falls in love, marries her, and gives her two new hands made of silver. The young woman gives birth to a son ��� but this is not the usual happy ending to the story. The king is away at war and the devil interferes once again (or, in some versions, a malicious mother-in-law), tricking the court into casting both mother and child back into the forest. "She is driven into nature," von Franz points out. "She has to go into deep introversion.... The forest [is] the place of unconventional inner life, in the deepest sense of the word."

The Handless Maiden then encounters an angel who leads her to a hut deep in the woods. Her human hands are magically restored during this time of forest retreat. When her husband returns from the war, learns that she's gone, and comes to fetch his wife and child home, she insists that he court her all over again, as the new woman she is now. Her husband complies -- and then, only then, does the tale conclude happily. The Handless Maiden's transformation is now complete: from wounded child to whole, healed woman; from miller's daughter to queen.

Von Franz compares the Handless Maiden's time of solitude in the woods to that of religious mystics seeking communion with god through nature. "In the Middle Ages, there were many hermits," she notes, "and in Switzerland there were the so-called Wood Brothers and Sisters. People who did not want to live a monastic life but who wanted to live alone in the forest had both a closeness to nature and also a great experience of spiritual inner life. Such Wood Brothers and Sisters could be personalities on a high level who had a spiritual fate and had to renounce active life for a time and isolate themselves to find their own inner relationship to God. It is not very different from what the shaman does in the Polar tribes, or what the medicine men do all over the world, in order to seek immediate personal religious experience in isolation."

In other versions of the Handless Maiden narrative, the young queen's time in the woods is not solitary. The angel (or "white spirit") leads her to an inn at the very heart of the forest, where she's taken in by gentle "folk of the woods." (It's not always made clear whether they are human or magical beings.) The queen stays with them for a full seven years (a traditional period of time for magical/shamanic initiation in ancient Greece and other cultures world-wide), during which time her hands slowly re-grow.

In her essay "Silverhands: Healing the Wounded Wild," Kim Antieau uses this variant of the story to reflect on illness, the healing process, and the ways our relationship with the natural world impacts both physical and psychic health. "In many cultures," she writes, "the prescription for chronic illness was a stay in the country (not necessarily the wild country). In ancient Greece, the chronically ill went to Asklepian Temples for relief. The priests created tenemos ��� sacred space ��� for the patient to help facilitate healing. The ill went to the temples and prepared with purification and ritual for a healing dream. Then the patient went to the abaton ��� the sleeping chamber ��� and dreamed. Often the dreams either healed the patients or told them of a remedy which would heal them.

"Today, practitioners of integrated medicine believe the body wants to heal, and the patient needs the time, encouragement, support and space to be able to get well. In many instances the time, encouragement, and support can be found, but wild spaces are lacking. Silvia [the Handless Maiden] was able to travel deep into a wild place. Where do we go? Where do the wild things go (including human beings) when no wild remains?"

Midori Snyder comes at the story from a different angle in her excellent essay "The Armless Maiden and the Hero's Journey," examining the tale, in its various forms, as a classic rites of passage narrative.

When such stories are devised for young men, she notes, the hero typically sets off from home seeking adventure or fortune in the unknown world, where the fantastic waits to challenge him. "Along the journey, his worth as a man and as a hero is tested. But when the trials are done, he returns home again in triumph, bringing to his society new���found knowledge, maturity and often a magical bride....

"While no less heroic, how different are the journeys of young women. In folktales, the rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood is confirmed by marriage and the assumption of adult roles. In traditional exogamous societies, young women were required to leave forever the familiar home of their birth and become brides in foreign and sometimes faraway households. In the folktales, a young girl ventures or is turned out into the ambiguous world of the fantastic, knowing that she will never return home. Instead at the end of a perilous and solitary journey, she arrives at a new village or kingdom. There, disguised as a dirty���faced servant, a scullery maid, or a goose girl, she completes her initiation as an adult and, like her male counterpart, brings to her new community the gifts of knowledge, maturity, and fertility."

Although fairy tales have been known as children's stories from roughly the 19th century onward, older versions of these same narratives (aimed at older audiences) looked unflinchingly at the darkest parts of life: at poverty, hunger, abuse of power, domestic violence, incest, rape, the sale of young daughters to the highest bidder under the guise of arranged marriages, the effects of remarriage on family dynamics, the loss of inheritance or identity, the survival of treachery or calamity. In rites of passage tales devised for young women, the heroes don't tend to ride merrily off into the forest in search of fame and fortune, they are usually driven there by desperation; the forest, despite its perils, is a place of refuge from worse dangers left behind.

The Handless/Armless Maiden is not a passive princess in the old Disney mold, waiting for romance to rescue her. She finds her own way to the orchard of a king in her search of food, and although she agrees to marry him, a royal wedding is not the conclusion of her story, it's the half-way point. "It is a narrative with a strange hiccup in the middle," Midori points out. "The brutality of the opening scene seems resolved as the Armless Maiden is rescued in a garden and then married to a compassionate young man. But she has not completed her journey of transformation from adolescence to adulthood. She is not whole, not the girl she was nor the woman she was meant to be. The narratives make it clear that without her arms, she is unable to fulfill her role as an adult. She can do nothing for herself, not even care for her own child.

"Conflict is reintroduced into the narrative to send the girl back on her journey of initiation in the woods. There the fantastic heals her, and she returns reborn as a woman. Every narrative version concludes with what is in effect a second marriage. The woman, now whole, her arms restored by an act of magic, has become herself the magic bride, aligned with the creative power of nature. She does not return immediately to her husband but waits with her child in the forest or a neighboring homestead for him to find her. When he comes to propose marriage this second time, it is a marriage of equals, based on respect and not pity.

"Conflict is reintroduced into the narrative to send the girl back on her journey of initiation in the woods. There the fantastic heals her, and she returns reborn as a woman. Every narrative version concludes with what is in effect a second marriage. The woman, now whole, her arms restored by an act of magic, has become herself the magic bride, aligned with the creative power of nature. She does not return immediately to her husband but waits with her child in the forest or a neighboring homestead for him to find her. When he comes to propose marriage this second time, it is a marriage of equals, based on respect and not pity.

"I have come to believe," Midori continues, "that robust narratives such as the Armless Maiden speak to women not only when they are young and setting out on that first rite of passage, but throughout their lives. In Women Who Run With the Wolves, psychologist Clarissa Pinkola Est��s presents a fascinating analysis of this tale, demonstrating the guiding role the armless maiden plays in a woman's psychic life:

" 'The Handless Maiden is about a woman's initiation into the underground forest through the rite of endurance. The word endurance sounds as though it means "to continue without cessation," and while this is an occasional part of the tasks underlying the tale, the word endurance also means "to harden, to make robust, to strengthen," and this is the principal thrust of the tale, and the generative feature of a woman's long psychic life. We don't just go on to go on. Endurance means we are making something.'

"To follow the example of the armless maiden," Midori concludes, "is an invitation to sever old identities and crippling habits by journeying again and again into the forest. There we may once more encounter emergent selves waiting for us. In the narrative, the Armless Maiden sits on the bank of a rejuvenating lake and learns to caress and care for her child, the physical manifestation of her creative power. Each time we follow the Armless Maiden she brings us face to face with our own creative selves."

Poet Vicki Feaver has also reflected on the story in relationship to creativity. In an interview in Poetry Magazine, Feaver discussed her poem "The Handless Maiden," inspired by the fairy tale :

"The story is that the girl���s hands are cut off by her father and she is given silver hands by the king who falls in love with her. Eventually, she goes off into the forest with her child and her own hands grow back. In the Grimms' version it is because she���s good for seven years. But there���s a Russian version which I like better where she drops her child into a spring as she bends down to drink. She plunges her handless arms into the water to save the child and it���s at that moment that her hands grow. I read a psychoanalytic interpretation by Marie Louise von France in her book, The Feminine in Fairytales in which she argues that the story reflects the way women cut off their own hands to live through powerful and creative men. They need to go into the forest, into nature, to live by themselves, as a way of regaining their own power. The child in the story represents the woman���s creativity that only the woman herself can save. This was such a powerful idea that I had to write about it. It took me three years to find a way of doing it. In the end I chose the voice of the Handless Maiden herself -- as if I was writing the poem with the hands that grew at the moment that she rescued her work, her child.

"I suppose I go through the process of endlessly cutting off my hands and having to grow them again. You ask if I���ve found any strategies for writing. Only to go away on my own, to be myself, and just to write." *

"Fairy tales are journey stories," says Ellen Steiber (in a beautiful essay on the fairy tale "Brother and Sister"). "They deal with initiation and transformation, with going into the forest where one's deepest fears and most powerful dreams are realized. Many of them offer a map for getting through to the other side."

In the universe of fairy tales, the Just often find a way to prevail, the Wicked generally receive their comeuppance ��� but there's more to such tales than a formula of abuse and retribution. The trials these wounded young heroes encounter illustrate the process of transformation: from youth to adulthood, from victim to hero, from a maimed state to wholeness, from passivity to action. Fairy tales are, as Ellen says, maps through the woods, trails of stones to mark the path, marks carved into trees to let us know that other women and men have been this way before.

Though they warn us to steer clear of gingerbread houses and huts that stalk the woods on chicken's feet, they also show the way to true shelter, sanctuary, and places of healing deep in the forest. (The real lesson here, it seems to me, is to learn to tell the difference.) Think of the hut in "Brother and Sister," for example, where the siblings set up housekeeping in the woods, far from the everyday world (and their stepmother's malice), adapting to the rhythms of the forest, of self-sufficiency, and of the brother's enchantment. Or the woodland cabin in "The White Deer," where the deer-princess sleeps safely each night. Or the cottage (or cave) where Snow White finds shelter with a band of rough forest-dwelling men (the metal-working dwarves of Teutonic folklore in some versions, outlaws and brigands in others). Even the Beast's lonely castle deep in the woods is more sanctuary than prison...a place where captor and prisoner both transform, in true fairy tale fashion.

These places are linked not only by their woodland settings, but by the temporary nature of the sanctuary provided. The curse is broken or the secret revealed, or the magical task finished, or the trial survived; transformation is complete, and the hero must now return to the human world. Traditionally, rites-of-passage ceremonies are designed to propel initiates into a sacred place and sacred state (the realm of the spirits, gods, or ancestors; the place of vision, instruction, and metamorphosis)...but then to bring them back again, back to the tribe or community and to ordinary life. We're meant to come out of sweatlodge, down from the Vision Quest hill, home from the Moon Hut, back from the sacred hunt, bringing with us new knowledge, new dreams, a new status, a new name or role to play....intended not just for the sake of personal growth but in service to the whole tribe or community. Likewise, we're not meant to remain in the circle of enchantment deep in the fairy tale forest -- we're meant to come back out again, bringing our hard-won knowledge and fortune with us...in service to the family (old or new), the realm, the community; to children and the future.

These places are linked not only by their woodland settings, but by the temporary nature of the sanctuary provided. The curse is broken or the secret revealed, or the magical task finished, or the trial survived; transformation is complete, and the hero must now return to the human world. Traditionally, rites-of-passage ceremonies are designed to propel initiates into a sacred place and sacred state (the realm of the spirits, gods, or ancestors; the place of vision, instruction, and metamorphosis)...but then to bring them back again, back to the tribe or community and to ordinary life. We're meant to come out of sweatlodge, down from the Vision Quest hill, home from the Moon Hut, back from the sacred hunt, bringing with us new knowledge, new dreams, a new status, a new name or role to play....intended not just for the sake of personal growth but in service to the whole tribe or community. Likewise, we're not meant to remain in the circle of enchantment deep in the fairy tale forest -- we're meant to come back out again, bringing our hard-won knowledge and fortune with us...in service to the family (old or new), the realm, the community; to children and the future.

Unless, that is, we stay in the woods and take on a different role in the story...not a hero this time, but one of the forest dwellers who aids (or hinders) another's journey: the woodwose, the hermit, the sage, the mad prophet...the men and woman who run with the wolves...the femme sauvage with her herbs and charms... the conjure man with his beehives and songs....

But those are stories for another day, and another journey into the woods.

The gorgeous paintings above are by one of my all-time favorite artists, Jeanie Tomanek, who lives and works in Georgia, near Atlanta.

"My all-time favorite folktale is 'The Handless Maiden,'" says Jeanie. "It is about a woman���s journey toward wisdom and self-realization and the obstacles and helpers she encounters. This tale encompasses many of the archetypical representations of women. My 'Everywomen' portray the mothers, daughters, lovers, and crones. Strong, wise women who will survive. These are filtered through my own experiences many times."

The paintings here are: The Handless Maiden, Forget Me Not, Communion, Fairy Tales, The Diary, Silver Hands, Silver Hands and the Numbered Pears, The Diary, Envoy, and Sometimes in the Forest. (All imagery copyright by the artist.) Please visit Jeanie Tomanek's website to see more of her work, and Everywoman Art on Etsy to purchase originals and prints. You'll find an interesting interview with the artist here.

* I am grateful to Midori Snyder for allowing me to quote such a long passage from her Armless Maiden essay, and I urge anyone interested in the tale to please read this splendid essay in full. My knowledge of the Vicki Fever interview in Poetry Magazine comes entirely from Midori's essay, and I want to credit that properly here.

October 18, 2019

The Dark Forest

A journey through the dark of the woods is a motif common to fairy tales: young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach their destiny, or they find themselves abandoned there, cast off and left for dead. The path is hard to find and treacherous, prowled by wolves, ghosts, and wizards...but helpers, too, appear along the way: good fairies, wise elders, and animal guides, usually cloaked in unlikely disguises. The hero's task is to tell friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

The Dark Forest is not the merry greenwood of Robin Hood legends, or a Disney glade where dwarves whistle as they work, or a National Park with walkways and signposts and designated camping sites; it's the forest primeval, true wilderness, symbolic of the deep, dark levels of the psyche; it's the woods where giants will eat you and pick your bones clean, where muttering trees offer no safe shelter, where the faeries and troll folk are not benign. It's the woods you may never come back from.

"The woods enclose," writes Angela Carter in The Bloody Chamber. "You step between the fir trees and then you are no longer in the open air; the wood swallows you up. There is no way through the wood anymore; this wood has reverted to its original privacy. Once you are inside it, you must stay there until it lets you out again for there is no clue to guide you through in perfect safety; grass grew over the tracks years ago and now the rabbits and foxes make their own runs in the subtle labyrinth and nobody comes.... "

"I stood in the wood," Patricia McKillip tells us in Winter Rose. "Now it was a grim and shadowy tangle of thick dark trees, dead vines, leafless branches that extended twig like fingers to point to the heartbeat of hooves. The buttermilk mare, eerily, eerily pale in that silent wood, galloped through the trees;  tree boles turned toward it like faces. A woman in her wedding gown rode with a man in black; he held the reins with one hand and his smiling bride with the other. She wore lace from throat to heel; the roses in her chestnut hair glowed too bright a scarlet, mocking her bridal white���When they stopped, her expression began to change from a pleased, astonished smile, to confusion and growing terror. What twilight wood is this? she asked. What dead, forgotten place?"

tree boles turned toward it like faces. A woman in her wedding gown rode with a man in black; he held the reins with one hand and his smiling bride with the other. She wore lace from throat to heel; the roses in her chestnut hair glowed too bright a scarlet, mocking her bridal white���When they stopped, her expression began to change from a pleased, astonished smile, to confusion and growing terror. What twilight wood is this? she asked. What dead, forgotten place?"

The goblins of the glen, in Christina Rossetti 's great poem "Goblin Market," are thoroughly dangerous creatures. When young Laura buys but will not eat their fruit...

"Lashing their tails

They trod and hustled her,

Elbow���d and jostled her,

Claw���d with their nails,

Barking, mewing, hissing, mocking,

Tore her gown and soil���d her stocking,

Twitch���d her hair out by the roots,

Stamp���d upon her tender feet,

Against her mouth to make her eat."

To know the woods and to love the woods is to embrace it all, the light and the dark -- the sun dappled glens and the rank, damp hollows; beech trees and bluebells and also the deadly fungi and poison oak. The dark of the woods represents the moon side of life: traumas and trials, failures and secrets, illness and other calamities. The things that change us, temper us, shape us; that if we're not careful defeat or destroy us...but if we pass through that dark place bravely, stubbornly, wisely, turn us all into heroes.

"The sense of secrets, silence, surprises, good and bad, is fundamental to forests and informs their literatures," notes Sara Maitland in Gossip from the Forest. "In fairy stories this is sometimes simple and direct: Hansel and Gretel get lost in the woods, and then suddenly they come upon the gingerbread house. Snow White runs in terror through the forest and suddenly stumbles upon the dwarves' cottage; characters spending scary nights in or under trees suddenly see a twinkling light -- and they make their laborious way towards it without having any idea what they will find when they arrive.....

"The forest is about concealment and appearances are not to be trusted. Things are not necessarily what they seem and can be dangerously deceptive. Snow White's murderous stepmother is truly the 'fairest of them all,' The wolf can disguise himself as a sweet old granny. The forest hides things; it does not open them out but closes them off. Trees hide the sunshine; and life goes on under the trees, in thickets and tanglewood. Forests are full of secrets and silences. It is not strange that the fairy stories that come out of the forest are stories about hidden identities, both good and bad."

Appearance deceive in the dark of the woods. You must beware of the helpful wolf by the path, of the beautiful woman who asks for a kiss, of the cozy little house with its door standing open, a meal on the table, and its owner nowhere in sight. No matter how tired you are, warns Lisel Mueller (in her poem "Voice from the Forest"), do not enter that house, do not eat the bread, do not drink the wine: "It is only when you finish eating and, drowsy and grateful, pull off your shoes, that the ax falls or the giant returns or the monster springs or the witch locks the door from the outside and throws away the key."

But if you must enter, Neil Gaiman advises (in his poem "Instructions"), be courteous. And wary. "A red metal imp hangs from the green���painted front door, as a knocker, do not touch it; it will bite your fingers. Walk through the house. Take nothing. Eat nothing."

Those last words are important. Folk tales from all over the world warn that eating the food of a witch, a demon, a djinn, a troll, an ogre, or the faeries can be a dangerous proposition. You might owe your youngest child in return, or be bound to your host for the rest of your life. Likewise, don't kiss the beautiful woman who offers you a meal and a bed in her sumptuous chateau hidden deep in the woods. By morning light she'll be a monster, and her house but a pile of rocks and bones.

And yet, despite all the fairy tale warnings, sometimes we're compelled to run to the dark of the woods, away from all that is safe and familiar -- driven by desperation, perhaps, or the lure of danger, or the need for change. Young heroes stray from the safe, well-trodden path through foolishness or despair...but perhaps also by canny premeditation, knowing that venturing into the great unknown is how lives are tranformed. When Gretel walks into the woods, writes Andrea Hollander Budy (in her poem "Gretel," from The House Without a Dreamer), "she means to lose everything she is. She empties her dark pockets, dropping enough crumbs to feed all the men who have touched her or wished." In Ellen Steiber's "Silver and Gold," Red Riding Hood is asked to explain how she failed to distinguish her grandmother from a wolf. "It's complicated," she answers. "Sometimes it's hard to tell the difference between the ones who love you and the ones who will eat you alive." But what she doesn't say is that if the wolf comes again, she will surely follow. Why? Carol Ann Duffy answers in her poem "Little Red-Cap" (from The World's Wife): "Here's why. Poetry. The wolf, I knew, would lead me deep into the woods, away from home, to a dark tangled thorny place lit by the light of owls." To the place of poetry and adventure. The place where the hard and perilous work of transformation begins.

Sara Maitland compares the transformational magic in fairy tales to the everyday magic that turns caterpillars into butterflies. "[S]omething very dreadful and frightening happens inside the chrysalis," she points out. "We use the word 'cocoon' now to mean a place of safety and escape, but in fact the caterpillar, having constructed its own grave, does not develop smoothly, growing wings onto its first body, but disintegrates entirely, breaking down into organic slime which then regenerates in a completely new form. It goes as a child into the dark place and is lost; it emerges as the princess, or proven hero. The forest is full of such magic, in reality and in the stories."

My husband, Howard Gayton, a theatre director, uses the term "the Dark Forest" to refer to the part of the art-making process when we've lost our way: when the creation of a story or a painting or a play reaches a crisis point...when the path disappears, the idea loses steam, the plot line tangles, the palette muddies, and there is no way, it seems, to move forward. This often occurs, interestingly enough, right before true magic happens: first the crisis, then a breakthrough, an unexpected solution, and the piece comes to life. In a journal he wrote some years ago, while creating a fairy tale play in Portugal, he noted:

"Today I arrived in the middle of the Dark Forest, and the path has almost disappeared. It is scary now, and all the certainties have gone. The cast members are weary, and their ability to come up with interesting work has diminished. Even our opening meditation today felt tired. The Dark Forest. I knew I was heading into it, and, as always, the forest has its own way of manifesting in each creative project. Perhaps the performers are getting stuck and are unable to develop their parts. Perhaps it's that our storytelling has become flat, or that I'm neglecting some simple but crucial aspect of the directorial process. Or maybe it's all of these things....

"Today I arrived in the middle of the Dark Forest, and the path has almost disappeared. It is scary now, and all the certainties have gone. The cast members are weary, and their ability to come up with interesting work has diminished. Even our opening meditation today felt tired. The Dark Forest. I knew I was heading into it, and, as always, the forest has its own way of manifesting in each creative project. Perhaps the performers are getting stuck and are unable to develop their parts. Perhaps it's that our storytelling has become flat, or that I'm neglecting some simple but crucial aspect of the directorial process. Or maybe it's all of these things....

"It's difficult to keep my original vision of the piece as I travel through the forest. I have to trust the vision I had at the start of the work, and that the ideas that have been set in motion will somehow come to fruition. I know that I can't lose faith now, even though at this point in the creative process one often starts to question the show, the cast, and one's own ability. I can't turn around. I have to keep going, through this tough period, and find energy from somewhere.

'I'm reminded of the first day of the pilgrimage I once took to Santiago de Compostela, biking alone across the Pyranees of France and Spain. I cycled up route Napoleon late in the day, as the sun was setting, knowing that no matter how exhausted I was I had to push on to Roncesvalles. I couldn't turn back, I was too far along the path -- but if I didn't get to the monastery before sundown, I could lose my way in those cold, dark mountains, even die of exposure. It's a similar feeling that I have now: I'm exhausted, I don't know when the turning point will come, but I have to plough on."

So what should we do when we're in the Dark Forest, creatively or personally? Perservere. As Howard says, plough on. The gifts of the journey are worth the hardship, as writer & writing teacher Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew notes:

"When you enter the woods of a fairy tale, and it is night, the trees tower on either side of the path. They loom large because everything in the world of fairy tales is blown out of proportion. If the owl shouts, the otherwise deathly silence magnifies its call. The tasks you are given to do (by the witch, by the stepmother, by the wise old woman) are insurmountable -- pull a single hair from the crescent moon bear's throat; separate a bowl's worth of poppy seeds from a pile of dirt. The forest seems endless. But when you do reach the daylight, triumphantly carrying the particular hair or having outwitted the wolf; when the owl is once again a shy bird and the trees only a lush canopy filtering the sun, the world is forever changed for your having seen it otherwise. From now on, when you come upon darkness, you'll know it has dimension. You'll know how closely poppy seeds and dirt resemble each other. The forest will be just another story that has absorbed you, taken you through its paces, and cast you out again to your home with its rattling windows...."

And as Rainer Maria Rilke suggests (in Letters to a Young Poet):

"Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love."

Including the bears and the beasties, the fungi and faeries, the wolves and witches hidden in the deep forest...and the frightening, spell-binding, life-changing stories to be found only in the dark of the woods.

Art above: "Fur, Feather, Tooth and Nail" by Arthur Rackham, "The Faery Ring" by Alan Lee, two illustrations for Christina Rossetti's "Goblin Market" by Arthur Rackham, "Chase of the White Mouse" by John Anster Fitzgerald, "Goblins" by Brian Froud, "The Gingerbread House" by Trina Schart Hyman, "The Queen's Pearl Necklace" by John Bauer, "Hansel and Gretel" by Arthur Rackham, "The Lamb and the Serpent" by Arthur Rackham, "Little Red Riding Hood" by Richard Hermann Eschke, "The Briarwood" (from the Briar Rose series) by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, "Through the Dark Forest" by Brian Froud, "Troll in the Wood" by John Bauer, and "She Kissed the Bear on the Nose" by John Bauer.

October 17, 2019

The Fool Report

As Howard travels to Finland today at the start of his year-long Fool's Journey, we send love and gratitude to all of you who have helped make this possible.

Meanwhile, the "Funding for Foolery" campaign continues until the end of the month, and all contribtions (no matter how small) will allow us to keep this dear Fool on the road: https://www.gofundme.com/f/q5cuph.

Tilly, I'm afraid, has mixed feelings about this. She's proud of helping with the fund-raiser, but didn't realize that the end result would be Howard going off without her. He'll be traveling to four other countries as the year progresses (France, Spain, Germany, and Ireland) -- but don't worry, Tilly, he'll be home in-between.

And no doubt just as Foolish as ever.

Art above: The fool cards from the Dodal Tarot, Karyn Easton Tarot, and Rider-Waite Tarot.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers