Terri Windling's Blog, page 54

August 7, 2019

Following the deer

I'm out of the studio today due to health care issues, but will be back tomorrow (Thursday). In the meantime, I recommend this for your morning reading: "The Supple Deer" by the brilliant American poet Jane Hirschfield.

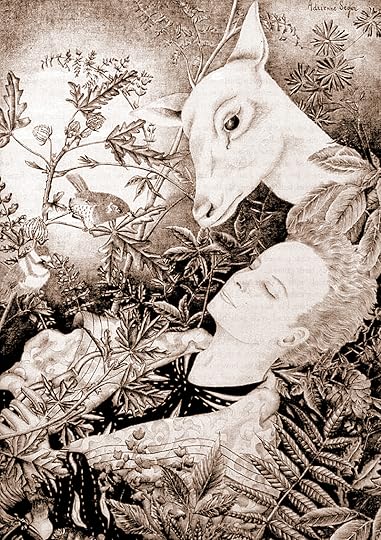

The illustration above, for Madame D'Aulnoy's classic fairy tale "The White Deer," is by the French book artist Adrienne S��gur (1901-1981) -- best known to English-language readers as the illustrator of The Golden Book of Fairy Tales.

August 6, 2019

Telling Our Stories: in honour of Toni Morrison, 1931-2019

���I believe in all human societies there is a desire to love and be loved, to experience the full fierceness of human emotion, and to make a measure of the sacred part of one's life. Wherever I've traveled -- Kenya, Chile, Australia, Japan -- I've found the most dependable way to preserve these possibilities is to be reminded of them in stories. Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives."

- Barry L��pez (About This Life)

"I come from a long line of tellers: mesemondok, old Hungarian women who tell while sitting on wooden chairs with their plastic pocketbooks on their laps, their knees apart, their skirts touching the ground...and cuentistas, old Latina women who stand, robust of breast, hips wide, and cry out the story ranchera style. Both clans storytell in the plain voice of women who have lived blood and babies, bread and bones. For them, story is a medicine which strengthens and arights the individual and the community."

- Clarissa Pinkola Est��s (Women Who Run With the Wolves)

"Make up a story.

"Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created. We will not blame you if your reach exceeds your grasp; if love so ignites your words they go down in flames and nothing is left but their scald. Or if, with the reticence of a surgeon's hands, your words suture only the places where blood might flow. We know you can never do it properly -- once and for all. Passion is never enough; neither is skill. But try. For our sake and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don't tell us what to believe, what to fear. Show us belief's wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear's caul."

- Toni Morrison (Nobel Prize lecture, 1993)

August 5, 2019

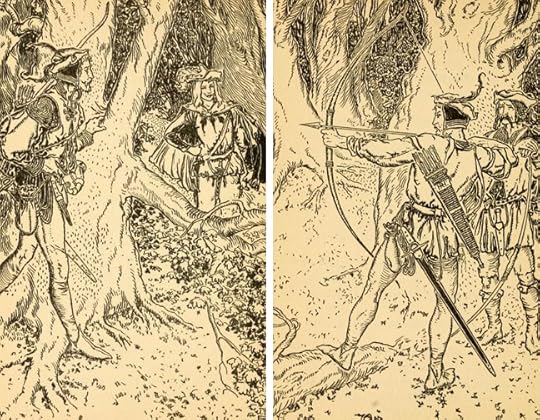

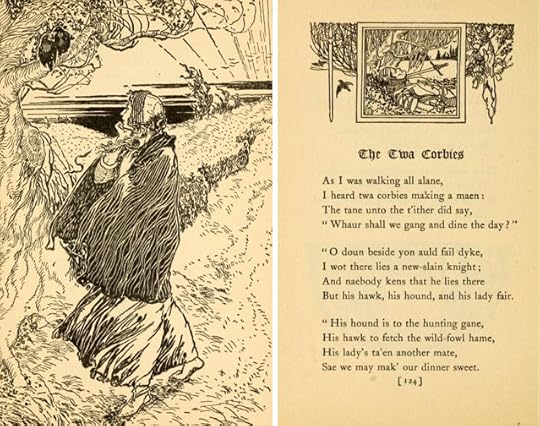

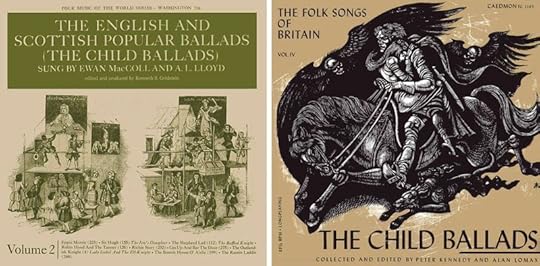

The Child Ballads

The great folklorist Francis James Child defined what he called the ���popular ballad��� as a form of ancient folk poetry, composed anonymously within the oral tradition, bearing the clear stamp of the preliterate peoples of the British Isles. Ballads, which are stories in narrative verse, are related to folktales, romances, and sagas, with which they sometimes share themes, plots, and characters (such as Robin Hood). No one knows how old the oldest are. It���s believed that they are ancient indeed -- and yet we have few historical records of them older than the sixteenth century. Little is known for certain about how the oldest ballads would have been performed -- but most likely they were recited, chanted, or sung without instrumentation. Right up to the twentieth century, ballads were traditionally sung a cappella, although today it is common to hear them accompanied by harp, guitar, fiddle, and other instruments.

Why do we have so few historical records? Because until relatively recently, they weren���t considered important enough to write down. With the rise of literacy, the songs and poems of Britian���s great oral tradition began to fall out of favor -- and ballads that had once been popular among all classes of society were now deemed primitive, pagan, the province of unlettered country folk. Because of this, few attempts were made to preserve ballads prior to the seventeenth century, and thus many were lost or were passed down through the years in fragmentary form. In the eighteenth century, ballad collection was still haphazard and sporadic, and the fruits of such labor were little regarded in academic circles. Universities did not yet consider folklore a respectable area of study, so manuscript collections remained in private hands, easily lost and forgotten.

In 1765, Bishop Thomas Percy came across one manuscript full of fine old ballads being used to light a kitchen fire. He saved them from the flames and published them in his book, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Percy���s book was a great success. It was much admired by such English Romantic writers as Coleridge, Southey, Shelley, and Keats, as well as the German Romantics Goethe, Tieck, and Novalis, and sparked much literary interest in the songs and legends of bygone days. Another fan of Percy���s book was the novelist Sir Walter Scott, who collected the ballads of his native Scotland in the early nineteenth century. Scott sat at the center of a circle of poets and antiquarians who were devotees (and romanticizers) of the ancient history of the British Isles. This group did much to popularize the old songs and tales of Scotland, England, and Ireland -- but still no British university would sponsor a proper academic collection of the country���s ballads.

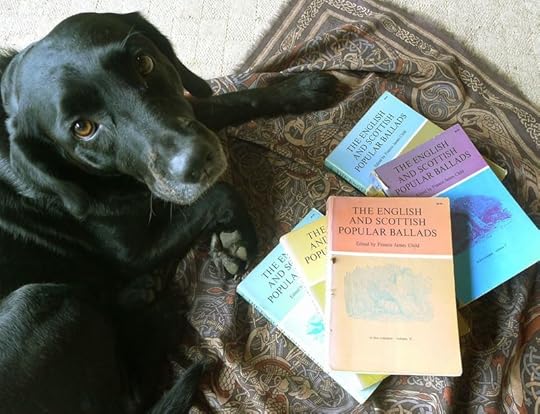

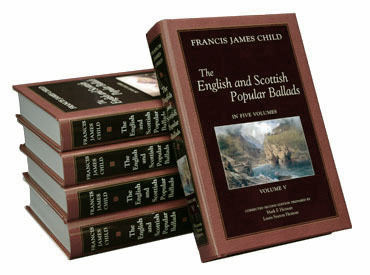

That job fell to an American scholar, Francis James Child of Harvard University, who was urged to take on the subject by his frustrated British colleagues. Child hesitated, somewhat daunted by the immensity of the job at hand, and then he plunged in, devoting the rest of his life to the study of ballads. Beginning in the 1870s, Child set out to track down every extant version of every genuine popular ballad in the English and Scottish traditions. He limited himself to England and Scotland because the ballads of these countries overlapped, whereas Irish ballads were a separate tradition, requiring a depth of knowledge of Ireland���s language and history he didn���t possess. His goal was to publish the collected ballads with notes tracing their histories, relating them to songs and tales to be found in folklore the world over. The result of this remarkable labor was The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, published in five volumes between 1882 and 1898. It���s a work that���s still widely used today, revered by scholars and musicians alike.

That job fell to an American scholar, Francis James Child of Harvard University, who was urged to take on the subject by his frustrated British colleagues. Child hesitated, somewhat daunted by the immensity of the job at hand, and then he plunged in, devoting the rest of his life to the study of ballads. Beginning in the 1870s, Child set out to track down every extant version of every genuine popular ballad in the English and Scottish traditions. He limited himself to England and Scotland because the ballads of these countries overlapped, whereas Irish ballads were a separate tradition, requiring a depth of knowledge of Ireland���s language and history he didn���t possess. His goal was to publish the collected ballads with notes tracing their histories, relating them to songs and tales to be found in folklore the world over. The result of this remarkable labor was The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, published in five volumes between 1882 and 1898. It���s a work that���s still widely used today, revered by scholars and musicians alike.

The life of the man behind these famous books is as interesting as the ballads he loved. Born the son of a sailmaker, Child grew up on the docks of Boston harbor -- until his aptitude for learning brought him to the attention of a distinguished Cambridge scholar. The boy was encouraged to transfer from his working-class school to Boston���s Latin School, after which he was sponsored at Harvard, where he graduated at the top of his class. Except for two years of study abroad, Child spent the rest of his life at Harvard, rising to become the first chairman of the newly created department of English. He built his substantial reputation on groundbreaking studies of Chaucer and Spenser, but he also had an abiding love for philology, ancient poetry, folklore, and fairy tales. The latter interests had been whetted during the two years Child spent in Germany, where he���d been exposed to the work of the folklore enthusiasts of the Heidelberg Circle of scholars, which included folk song collectors Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim, and the remarkable Brothers Grimm. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, noted Child���s friend and colleague G. L. Kittredge, ���may even, in a very real sense, be regarded as the fruit of these years in Germany. Throughout his life he kept pictures of Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm on the mantel over his study fireplace.���

The life of the man behind these famous books is as interesting as the ballads he loved. Born the son of a sailmaker, Child grew up on the docks of Boston harbor -- until his aptitude for learning brought him to the attention of a distinguished Cambridge scholar. The boy was encouraged to transfer from his working-class school to Boston���s Latin School, after which he was sponsored at Harvard, where he graduated at the top of his class. Except for two years of study abroad, Child spent the rest of his life at Harvard, rising to become the first chairman of the newly created department of English. He built his substantial reputation on groundbreaking studies of Chaucer and Spenser, but he also had an abiding love for philology, ancient poetry, folklore, and fairy tales. The latter interests had been whetted during the two years Child spent in Germany, where he���d been exposed to the work of the folklore enthusiasts of the Heidelberg Circle of scholars, which included folk song collectors Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim, and the remarkable Brothers Grimm. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, noted Child���s friend and colleague G. L. Kittredge, ���may even, in a very real sense, be regarded as the fruit of these years in Germany. Throughout his life he kept pictures of Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm on the mantel over his study fireplace.���

Child was a textual scholar rather than a field collector, and he put his massive ballad compilation together by seeking out every manuscript copy of ballad material he could lay his hands on, with the help of a small army of fellow scholars searching out songs and fragments of songs throughout the British Isles. Another reason he depended on manuscripts rather than the memories of folk  musicians was that the British popular ballad, in his view, was no longer a living tradition. The ballads he sought were the ancient ones -- not the ���broadside ballads��� that dominated the nineteenth-century folk musician���s repertoire. Broadsheet ballads were authored song lyrics designed to fit traditional tunes, cheaply printed and sold for pennies on street corners from the sixteenth century onward. These were contemporary compositions, rather than ancient poetry from the oral tradition -- though sometimes broadside ballads mimicked the language of much older songs, and determining which was which was a problem Professor Child was both intrigued and vexed by.

musicians was that the British popular ballad, in his view, was no longer a living tradition. The ballads he sought were the ancient ones -- not the ���broadside ballads��� that dominated the nineteenth-century folk musician���s repertoire. Broadsheet ballads were authored song lyrics designed to fit traditional tunes, cheaply printed and sold for pennies on street corners from the sixteenth century onward. These were contemporary compositions, rather than ancient poetry from the oral tradition -- though sometimes broadside ballads mimicked the language of much older songs, and determining which was which was a problem Professor Child was both intrigued and vexed by.

To the dismay of this meticulous scholar, in the absence of clear historical records he was often forced to depend on textual clues and his own best judgment. Fortunately, that judgment was finely honed by his fluency in archaic languages, and his extraordinary knowledge of folklore traditions the world over. He chose, he explained in a letter to a friend, to err on the side of inclusiveness. Where he had lingering doubts about the authenticity of a song variant, he was apt to  include it anyway, along with notes outlining his reservations. His task was greatly complicated by the fact that the ballads of Britain had been so badly recorded and preserved compared with those of other countries, such as Denmark. ���The ballads should have been collected as early as 1600,��� he noted sadly; ���then there would have been such a nice crop; the aftermath is very weedy.��� Another complication was that ballads written down and published from the eighteenth century onward had been edited, censored, or ���improved��� by folklore enthusiasts who were literary men, romantics rather than rigorous academics. The prime example of this was Percy���s famous Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Child and other folklorists suspected that Percy had altered the text of ballads to suit the literary tastes of his day -- particularly as Percy would not allow an examination of the ballad manuscript in his possession. Working with British scholar F. J. Furnivall, Child was instrumental in persuading Percy���s descendants to finally release this manuscript, which did ideed confirm that Percy had edited and ���improved��� the original ballads.

include it anyway, along with notes outlining his reservations. His task was greatly complicated by the fact that the ballads of Britain had been so badly recorded and preserved compared with those of other countries, such as Denmark. ���The ballads should have been collected as early as 1600,��� he noted sadly; ���then there would have been such a nice crop; the aftermath is very weedy.��� Another complication was that ballads written down and published from the eighteenth century onward had been edited, censored, or ���improved��� by folklore enthusiasts who were literary men, romantics rather than rigorous academics. The prime example of this was Percy���s famous Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Child and other folklorists suspected that Percy had altered the text of ballads to suit the literary tastes of his day -- particularly as Percy would not allow an examination of the ballad manuscript in his possession. Working with British scholar F. J. Furnivall, Child was instrumental in persuading Percy���s descendants to finally release this manuscript, which did ideed confirm that Percy had edited and ���improved��� the original ballads.

Sifting through the mountain of material he collected, sniffing out alterations and forgeries, Child amassed a group of 305 songs with their roots in the oral tradition, along with variants of each song, sometimes in dozens of alternate versions. The final volume of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads was completed the  year of Child���s death, but he died before writing the book���s introduction, which would have explained his method of selection and given us an overview of his work. Yet even without this, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads was hailed by critics on both sides of the Atlantic and became a cornerstone of modern folklore scholarship. In addition, Child was instrumental in establishing the American Folklore Society, serving as its first president from 1888 to 1889. But sadly, Child did not live to see that movement flower in subsequent years, and he died doubting his work had relevance to a modern age. ���If he���d lived just a little longer,��� says Mark F. Heiman of Loomis House, which published a handsome new edition of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ���he would have seen the golden age of the ballad collector and folklorist. He would have seen how important his life���s work really was.���

year of Child���s death, but he died before writing the book���s introduction, which would have explained his method of selection and given us an overview of his work. Yet even without this, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads was hailed by critics on both sides of the Atlantic and became a cornerstone of modern folklore scholarship. In addition, Child was instrumental in establishing the American Folklore Society, serving as its first president from 1888 to 1889. But sadly, Child did not live to see that movement flower in subsequent years, and he died doubting his work had relevance to a modern age. ���If he���d lived just a little longer,��� says Mark F. Heiman of Loomis House, which published a handsome new edition of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, ���he would have seen the golden age of the ballad collector and folklorist. He would have seen how important his life���s work really was.���

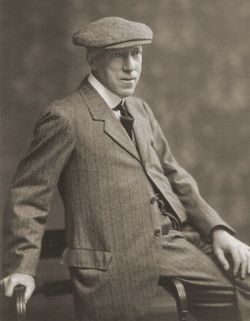

Child���s work went on to inspire a whole new generation of folklorists, men and women who weren���t quite so convinced that the oral tradition was irretrievably dead and gone. One of them was Cecil Sharp, who began collecting English folk songs and dance tunes in the early years of the twentieth century. Sharp was a trained musician, and unlike Child he was also interested in preserving the music of the ballad tradition rather than viewing ballads primarily as poetry. He noted that the Child ballads were rarely part of the repertoire of the elderly singers he listened to in the countryside; they���d been replaced by broadside ballads and other more recent songs. Sharp wondered if the older ballads might have survived among the British and Scottish settlers in America, particularly among the descendants of settlers in isolated mountain regions, where ���pennysheets��� of modern ballads would not have been available. Between 1914 and 1918, Sharp made two extensive trips through the Appalachian Mountains, collecting over a thousand songs with the aid of his secretary, Maud Karpeles. Sharp and Karpeles discovered that many of the Child ballads were indeed still known and performed in Appalachia, although sometimes the titles and lyrics had changed somewhat in this new setting. Sharp published these ballads in his now-classic English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, which in turn inspired new folklore studies and new collection efforts throughout the United States.

Child���s work went on to inspire a whole new generation of folklorists, men and women who weren���t quite so convinced that the oral tradition was irretrievably dead and gone. One of them was Cecil Sharp, who began collecting English folk songs and dance tunes in the early years of the twentieth century. Sharp was a trained musician, and unlike Child he was also interested in preserving the music of the ballad tradition rather than viewing ballads primarily as poetry. He noted that the Child ballads were rarely part of the repertoire of the elderly singers he listened to in the countryside; they���d been replaced by broadside ballads and other more recent songs. Sharp wondered if the older ballads might have survived among the British and Scottish settlers in America, particularly among the descendants of settlers in isolated mountain regions, where ���pennysheets��� of modern ballads would not have been available. Between 1914 and 1918, Sharp made two extensive trips through the Appalachian Mountains, collecting over a thousand songs with the aid of his secretary, Maud Karpeles. Sharp and Karpeles discovered that many of the Child ballads were indeed still known and performed in Appalachia, although sometimes the titles and lyrics had changed somewhat in this new setting. Sharp published these ballads in his now-classic English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, which in turn inspired new folklore studies and new collection efforts throughout the United States.

Despite the keen interest of folklorists, ballads remained a specialized interest for much of the twentieth century, until the huge folk music revival of the 1960s and ���70s. In those years, Joan Baez, Judy Collins, and other popular singers recorded ballads from the Child collections, and a Celtic music revival exploded across the British Isles, Brittany, and America. Folk-rock bands like Pentangle, Fairport Convention, and Steeleye Span updated the ballads for a new generation, while singers like Martin Carthy, Nic Jones, Frankie Armstrong, Jean Redpath, and June Tabor created an audience for traditional music played in more traditional ways.

Today, that revival is still going strong, with Child ballads performed by Jon Boden, Iona Fyfe, Fay Hield, Sam Lee, Malinky, Loreena McKennit, Jim Moray, Karine Polwart, Kate Rusby, and many, many others. (You'll find an online discography here). I particularly recommend Ana��s Mitchell & Jefferson Hamer's Child Ballads album, and Jon Boden's Folk Song A Day site. To dig further into this subject, you'll find a lot of good material in the digital archives of the English Folk Song & Dance Society. To read about the ways the Child ballads have influenced fantasy literature and comics, go here.

August 4, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I periodically turn to Child Ballads for our "Monday Tunes," not only because I love them, but because they are full of stories that have also inspired other forms of mythic art, from fantasy novels to poetry and comics. The songs I've chosen to play today are ones that haven't yet been featured on Myth & Moor, but of course there are many, many others. If you'd like further recommendations, go here for previous ballad-related posts.

Above: "Orfeo" (Child Ballad #19) performed by the Scottish folk band Malinky, based in Edinburg. The song is from their lovely new album Handsel (2019).

Below: "The Forester" (Child Ballad #110), performed by Malinky, also from the new album.

Above: "Lady Diamond" (Child Ballad #269) performed by Scottish singer and harpist Rachel Newton. The song appeared on her solo album The Shadow Side (2012).

Below: "Edward" (Child Ballad #13) performed by the Scottish folk band Old Blind Dogs, from Aberdeen. The song appeared on their seventh album, The World's Room (1999).

Above: "The Gardener" (Child Ballad #219) performed by the great English folk singer June Tabor. The song appeared on her solo album A Quiet Eye (2000).

Below: "The Cruel Mother" (Child Ballad #20) performed by Scottish singer Fiona Hunter (from Malinky). The song appeared on her first solo album Fiona Hunter (2014).

Above: The Dowie Dens of Yarrow" (Child Ballad #214) performed by Scottish singer/songwriter Karine Polwart, based in Edinburgh. The song appeared on her third solo album Fairest Floo'er (2007).

Below: "Lord Baker" (Child Ballad #53) performed by Susan McKeown, a Dublin-born singer based in New York City. The song appeared on her solo album Lowlands (200).

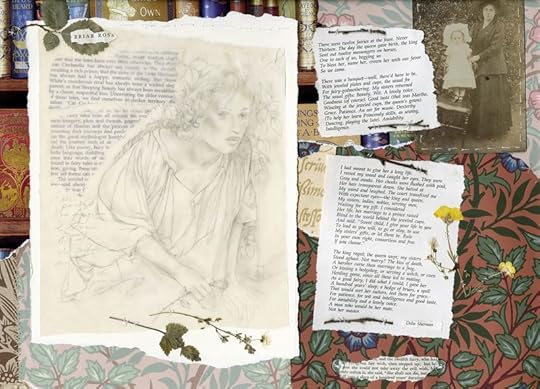

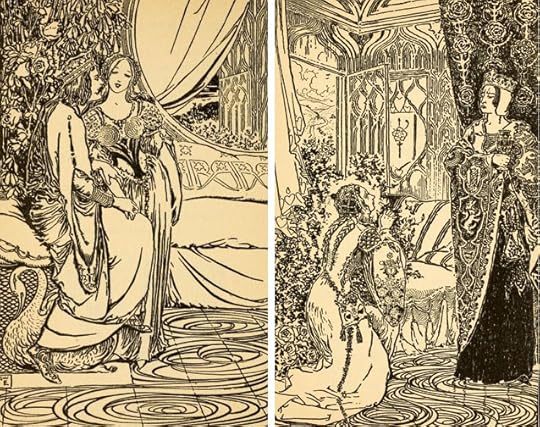

Art: Illustrations for Sir Orfeo (a Middle English narrative poem related to the ballad "King Orfeo") and Thorn Rose by British book artist Errol le Cain (1941-1989).

August 2, 2019

On inspiration, madness, and art

In the mythic tradition, both artists and shamans tread perilously close to insanity; and indeed, in some cases their gifts specifically come from journeying into the wilds of madness, or Faerie, or the Realm of the Gods, and back again. The process of creative intuition and inspiration is a profoundly mysterious one, and it can certainly seem like magic or madness to those on the outside looking in.

In Tuesday's post, Lewis Hyde explained the ancient Greek and Roman view that creative "genius" is not a personal attribute, but a guiding spirit, or daemon: the divine spark of inspiration comes from the daemon, and the artist's job is to be a worthy vessel for that spark. On Wednesday, Philip Pullman described the feeling that stories come from somewhere else, and need special protection while they're still new and tender, taking form on the page. I've come across many artists in different fields who view creation in similar ways: as an almost mystical, alchemical process composed not only of skill and intent but also of creative ideas that come through us from some unknown and unknowable place.

Here, for example, is Haruki Murakami describing his creative process: "A short story I have written long ago would barge into my house in the middle of the night, shake me awake and shout, 'Hey, this is no time for sleeping! You can't forget me, there's still more to write!' Impelled by that voice, I would find myself writing a novel."

He's far from the only writer to report that tales and characters sometimes just appear, large as life, demanding to be attended to and rendered into print. On one end of the spectrum are the logical, methodical artists who map their stories and paintings and performances entirely in advance, rarely deviating from the route they've set themselves...and on the other end are the purely intuitive artists who discover the work as they create it, as though it already exists somewhere, waiting to be found and given earthly form. (The majority of us I suspect fall somewhere on the line between the two.)

"I did not deliberately invent Earthsea," Ursula Le Guin once said of her now-classic fantasy series. "I did not think, Hey wow -- islands are archetypes and archipelagoes are superarchetypes and let's build us an archipelago! I am not an engineer, but an explorer. I discovered Earthsea."

"In a very real way, one writes a story to find out what happens in it," notes Samuel R. Delaney. "Before it is written it sits in the mind like a piece of overheard gossip or a bit of intriguing tattle. The story process is like taking up such a piece of gossip, hunting down the people actually involved, questioning them, finding out what really occurred, and visiting pertinent locations. As with gossip, you can't be too surprised if important things turn up that were left out of the first-heard version entirely; or if points initially made much of turn out to have been distorted, or simply not to have happened at all.���

The creative process, like any mythic act of world creation (which is what it is, even for writers of Realist fiction), follows different rules than ordinary living. And that's not always a comfortable thing to experience -- for the artists themselves, or for those close by.

"In the middle of a novel," says Zadie Smith, "a kind of magical thinking takes over. To clarify, the middle of the novel may not happen in the actual geographical centre of the novel. By middle of the novel I mean whatever page you are on when you stop being part of your household and your family and your partner and children and food shopping and dog feeding and reading the post -- I mean when there is nothing in the world except your book, and even as your wife tells you she���s sleeping with your brother her face is a gigantic semi-colon, her arms are parentheses and you are wondering whether rummage is a better verb than rifle. The middle of a novel is a state of mind. Strange things happen in it. Time collapses."

While the world goes on wily-nily without us, we're off chasing visions down the hedgerows of the mind, living in a place where lines and landscapes and imaginary voices become more real than the keyboard under our fingers, the paint in the cup, the vibration of the harp string.

"I discover my images during the process of working on them," says artist Rima Staines. "I'm interested in the spark which happens when the image suddenly comes together in front of you and starts to work. It's almost as if, while I'm drawing the lines, what I'm about to draw next reveals itself to me. Maybe I will start to see a face in some loose lines -- in the same way that you sometimes see a face or figure in the gnarled bark of a tree. I am not completely in control of the process; it's as though the characters in the image make themselves known to me. It���s like being in an altered state of consciousness. And it can take a real presence of mind to stay in that process. It often feels like walking a tightrope whilst you are creating: it is all too easy to come out of the process by looking at your work too critically -- or to tip the other way and go too far with a particular idea."

My husband Howard, who works in theatre, points out that "artists often live in two worlds at once, which is why we can seem a bit mad to other people. One foot is in the real world, where we have to feed ourselves and pay the bills, and the other foot is in the creative world, which has a different time scale and demands different things of us. One way of living seems sane and sensible, the other is ruled by impulse, intuition, and archetypal forces of dream and creation. Living constantly on the knife-edge between these two different worlds can be both liberating and distressing, I find, in equal measure."

"When I was young, it seemed so much easier," Brian Froud recalls. "You had a mad idea and you just went with it. Youth has an arrogance. With age and experience, I know enough to question myself more, so the creative impulse can be more of a struggle -- but there���s still that inner voice which, when I draw a line, goes: No. Rub it out, draw another. No! And then, suddenly, Oh, yes! And then I think: 'Where has that come from? Why is this the right line? And why were all the other ones wrong?' To an observer those lines would probably seem all the same -- but those rubbed-out lines were wrong. The drawing knows what it wants to to be."

���I think the mystery of art lies in this, that the artists��� relationship is essentially with their work," mused Ursula Le Guin, "not with power, not with profit, not with themselves, not even with their audience.���

This tends to be true for the stories and images that I inevitably find myself most drawn to: art that has arisen from a deeply personal conversation between the artist and the work at hand. It is art that walks perilously close to the Edge, that crosses the river of blood into Faerie, that flies so high it is scorched by the sun, and then returns to tell the tale to us. It is art that needed to be written, or painted, or sung, or woven, or otherwise shaped. It is art gifted by the Mystery to the maker...and then, in turn, gifted to us.

"We're not mad," writes author and teacher Sue Moorcroft, defending the peculiar habits of artists, "we're inhabited."

Inhabited by the work. Inhabited by the lines, the colors, the characters, the stories. All clamouring to get out into the world.

Words: The quotes above are from a variety of essays and interviews. The poem in the picture is from Dreamtigers by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Harold Morland (EP Dutton, 1970). All rights reserved by the authors and translator. Pictures: Our local herd of Dartmoor ponies and their growing foals.

Related reading: Chasing inspiration, Stories in the air around us, When the magic is working, and Following the White Deer .

August 1, 2019

On listening to stories other than our own

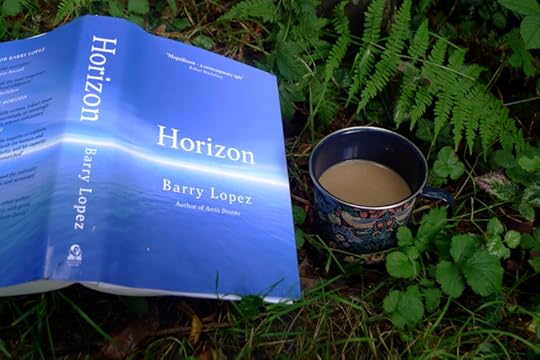

From Barry Lopez's new book Horizon (which is breathtakingly good):

"I read daily about the many threats to human life -- chemical, political, biological, and economic. Much of this trouble, I believe, has been caused by the determination of some to define a human cultural world apart from the nonhuman world, or by people's attempts to overrun, streamline, or dismiss the world as simply a warehouse for materials, or mere scenery.

"It is here, with these attempts to separate the fate of the human world from that of the nonhuman world that we come face-to-face with a biological reality that halts us in our tracks: nature will be fine without us. Our question is no longer how to exploit the natural world for human comfort and gain, but how we can cooperate with one another to ensure we will someday have a fitting, not a dominating, place in it.

"What cataclysm, I often wonder, or better, what act of imagination will it finally require, for us to be able to speak meaningfully with one another about our cutural fate and about our shared biological fate?

"As time grows short, the necessity to listen attentively to foundational stories other than our own becomes imperative. As I've encountered other human cultures over time, especially those radically different from my own, each one has seemed to me both deep and difficult to comprehend, not 'exotic' or 'primitive.' Many cultures are still distinguished today by wisdoms not associated with modern technologies but grounded, instead, in an acute awareness of human foibles, of the traps people tend to set for themselves as the enter the ancient labyrinth of hubris or blindly pursue the appeasement of their appetities.

"It is nearly impossible for wise people in any culture to plumb the depths of their own metaphysical assumptions, out of which they have fashioned a world view. It is also difficult to listen closely while some other people's guiding stories unfold, or to separate successfully the literal from the figurative in those stories, the fact from the metaphor. And yet if we persist in believing that we alone, living in whatever culture we're from, are right, and that we therefore have no need to listen to anyone else's stories, stories that we often can't quite understand and so are unwilling to discuss, we endanger ourselves. If we remain fearful of human diversity, our potential to evolve into the very thing we most fear -- to become our own fatal nemisis -- only increases.

"The desire to known ourselves better, to understand especially the source and the nature of our dread, looms before us now like a specter in a half-lit world, a weird dawn breaking over a half-lit scene of carnage: unbreathable air, human diasporas, the Sixth Extinction, ungovernable political mobs.

"In the wisdom of the desert, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, considering the moral obtuseness of the conquistadores, writes, 'In subjugating primitive worlds they only imposed on them, with the force of cannons, their own confusion and their own alienation.' If this colonizing impulse in our heritage is still with us, a need to dominate, must we continue to support it? Must we go on to deferring to tyrants, oligarchs, and sociopathic narcissists? The French poet, diplomat, and Nobel laureate Alexis L��ger, in his epic poem Anabase, asks where the troubled world is to find its real protectors, warriors so dedicated to protecting the welfare of their communities that they can be depended upon 'to watch the rivers for the approach of their enemies, even on their wedding nights.'

"Where, today, can the voices of such guardians be heard over the raucous din in support of economic growth?

"In her poem 'Kindness,' the Palestinian American poet Naomi Shihab Nye writes that to learn the kindness required to ameliorate cruelty and injustice the real world presents us with,

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans...

"In which national parliaments and legislatures today can we find deliberations characterized by such a measure of humility? In which congresses might questions of ethical responsibility be successfully raised for discussion? In which Western nations does a determination to address the mental, spiritual, and physical health of children override indifference to their fate? Or are these questions now thought to be anachronistic, questions no longer relevant to our situation?

"...Most anyone today can imagine the biblical horseman of the Apocalyse deployed on the horizon, pick out one and characterize him. Anyone, too, facing this frightening horizon, might opt to turn away, decide instead to become lost in beauty, or choose to remain walled off from the world in electronic distractions, or select catatonic isolation within the fortress of the self. But one can choose, as well, to step into the treacherous void between oneself and the confounding world, and there be staggered by the breadth, the intricacy, the possibilities of that world, accepting its requirement for death but working to lessen the degree of cruelty and to increase the reach of justice in every corner.

"For many years this kind of heroic effort -- essential to learn to cooperate with strangers -- has been calling to modern people. I've wondered, watching economically powerful nations scrambling in the world's remote corners for the last large deposits of copper, iron, bauxite, and other ores, or reading about the failure of the once-dependable ocean fisheries, or about cynical corporate maneuvering to secure the last reservoirs of potable water, whether an unprecedented openness to other ways of understanding this disaster is not, today, humanity's only lifeline. Whether cooperation with strangers is not now our Grail."

Words: The passages quoted above are from Horizon by Barry Lopez (Knopf and The Bodley Head, 2019). The poem in the picture captions, "Kindness" by Yusef Komunyakaa, is from Poetry 181, No. 5 (March 2003). All rights reserved by the authors. In addition to Horizon, which is a wonderful read, I recommend my friend Alan Weisman's fine book The World Without Us.

Related reading (Barry Lopez): The art of hope, Bowing to the birds, Children in the woods, and Three Writers on Aging.

July 31, 2019

On serving the story

In "Magic Carpets," an essay on writing fiction for children, Philip Pullman discusses "the various sorts of responsibility incumbent on an author: to himself and his family, to language, to his audience, to truth, and to his story itself." He has good things to say about about all of these aspects of storytelling, but I'm particularly intrigued by the last responsibility:

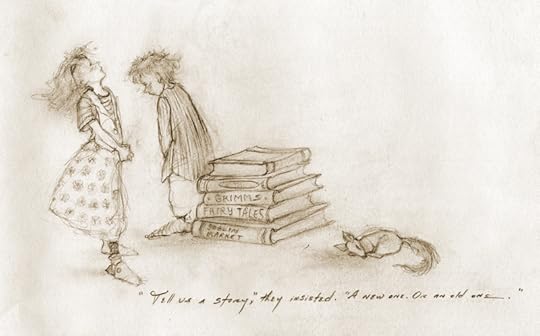

"It's one that every storyteller has to acknowledge, and it's a responsibility that trumps every other. It's a responsibility to the story itself. I first became conscious of this when I noticed that I'd developed the habit of hunching my shoulders to protect my work from prying eyes. There are various equivalents of the hunched shoulder and encircling arm: if we're working on the computer, for example, we tend to keep a lot of empty space at the foot of the piece, so that if anyone comes into the room we can immediately press that key that takes us to the end of the file, and show nothing but a blank screen. We're protecting it. There's something fragile there, something fugitive, which shows itself only to us, because it trusts us to maintain it in this half-resolved, half-unformed condition without exposing it to the harsh light of someone else's scrutiny, because a stranger's gaze would either make it flee altogether or fix it for good in a state that might not be what it wanted to become.

"So we have a protective responsibility: the role of a guardian, almost a parent. It feels as if the story -- before it's even taken the form of words, before it has any characters or incidents clearly revealed, when it's just a thought, just the most evanescent little wisp of a thing -- as if it's just come to us and knocked at our door, or just been left on our doorstep. If course we have to look after it. What else can we do?"

I was struck by this because it precisely describes the writing process for me. I can't bear to talk too much about what I am writing while the story is forming, or to have others read the manuscript until a late stage in the drafting process. In this, I am unusual among many of my writing colleagues and friends, who companionably share manuscripts back and forth, who form writing groups for support and critique, and who love nothing better then to chew over troublesome plot points, characters, and details of craft together.

"What kind of special snowflake am I," I have wondered, "that the very idea of such kind, collegial attention makes me shudder to my bones?" Reading Pullman, I am reassured I am not alone in my solitary habits. It's not me, as a writer, who is timid and fragile, but the stories themselves: the ones who knock at my door are shy little things, and must be coaxed onto the page gently, gently.

Pullman continues:

"What I seem to be saying here, rather against my will, is that stories come from somewhere else. It's hard to rationalise this, because I don't believe in a somewhere else; there ain't no elsewhere, is what I believe. Here is all there is. It certainly feels as if the story comes to me, but perhaps it comes from me, from my unconscious mind -- I just don't know; and it wouldn't make any difference to the responsibility either way. I still have to look after it. I still have to protect it from interference while it becomes sure of itself and settles on the form it wants.

"Yes, it wants. It knows very firmly what it wants to be, even though it isn't very articulate yet. It will go easily in this direction and very firmly resist going in that, but I won't know why; I just have to shrug and say, "OK -- you're the boss.' And this is the point where responsibility takes the form of service. Not servitude; not shameful toil mercilessly exacted; but service, freely and fairly entered into. This service is a voluntary and honourable thing: when I say I am the servant of the story, I say it with pride.

"And as servant, I have to do what a good servant should. I have to be ready to attend to my work at regular hours. I have to anticipate where the story wants to go, and find out what can make the progress easier -- by doing research, that is to say: by spending time in libraries, by going to talk to people, by finding things out. I have to keep myself sober during working hours; I have to stay in good health. I have to avoid taking on too many other engagements: no man can serve two masters. I have to keep the story's counsel: there are secrets between us, and it would be the grossest breach of confidence to give them away....And I have to prepared for a certain wilfulness and eccentricity in my employer -- all the classic master-and-servant stories, after all, depict the master as the crazy one who's blown here and there by the winds of impulse or passion, and the servant as the matter-of-fact anchor of common sense; and I have too much regard for the classic stories to go against a pattern as successful as that. So, as I say, I have to expect a degree of craziness in the story.

" 'No, master! Those are windmills, not giants!'

" 'Windmills? Nonsense -- they're giants, I tell you! But don't worry -- I'll deal with them.'

" 'As you say, master -- giants they are, by all means.'

"No matter how foolish it seems, the story knows best."

Then Pullman makes an important point:

"And finally, as the faithful servant, I have to know when to let the story out of my hands; but I have to be very careful about the other hands I put it into. My stories have always been lucky in their editors -- or perhaps, since I'm claiming responsibility here, they've been lucky they had me to guide them to the right ones. I suppose one's last and most responsible act as the servant of the story is to know when one can do no more, and when it's time to admit someone else's eyes might see it more clearly. To become so grand that you refuse to let your work be edited -- and we can all think of a few writers who got to that point -- is to be a bad servant and not a good one."

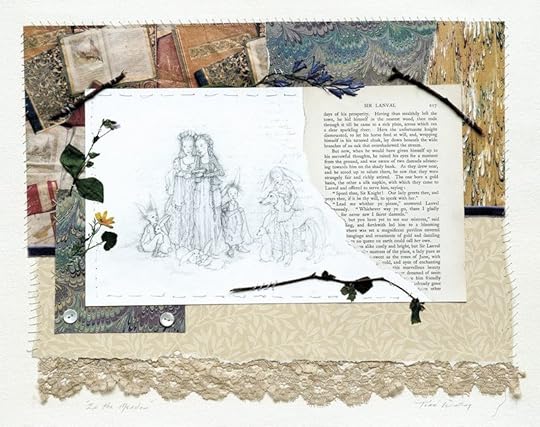

Passing our stories on to an editor is part of the job of being a writer -- but for me, this is at a late stage in the process, once my shivering little waif of a tale has been warmed and fed; once I've cleaned the mud and muck from its face, combed the leaves and moss from its hair, buttoned its jacket and tied its shoes. Only then is it ready to face the wide world outside my studio door.

Pullman concludes his list of authorial responsibilities by adding:

"...I don't want anyone to think that that responsibility is all there is to it. It would be a burdensome life, if the only relationship we had with our work was one of duty and care. The fact is that I love my work. The is no joy comparable to the thrill that accompanies a new idea, one that we know is full of promise and possibility -- unless it's the joy that comes when, after a long period of reflection and bafflement, of frustration and difficulty, we suddenly see the way through to the solution; or the delight when one of our characters says something far too witty for us to have thought of ourselves; or the slow, steady pleasure that comes from the regular accumulation of pages written; or the honest satisfaction that rewards work well done -- a turn in the story deftly handled, a passage of dialogue that reveals character as well as advancing the story, a pattern of imagery that unobtrusively echoes and clarifies the theme of the whole book.

"These joys are profound and long-lasting. And there is joy too in responsibility itself -- in the knowledge that what we're doing on earth, while we live, is being done to the best of our ability, and in the light of everything we know about what is good and true. Art, whatever kind of art it is, is like the mysterious music described in the words of the greatest writer of all, the 'sound and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.' To bear the responsibility of giving delight and hurting not is one of the greatest privileges a human being can have, and I ask nothing more than the chance to go on being responsible for it till the end of my days."

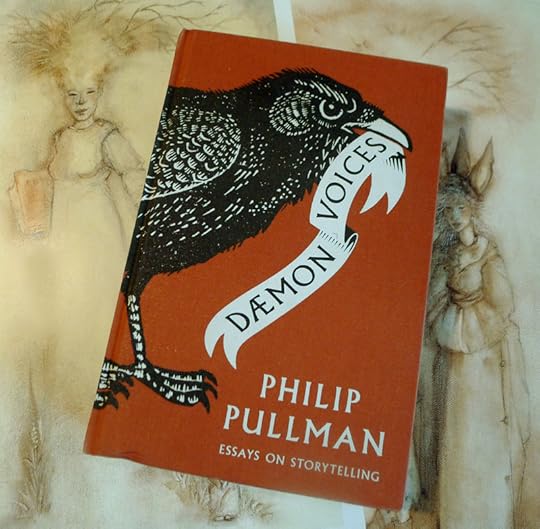

Words: The passages above are from "Magic Carpets: A Writer's Responsibilies" by Philip Pullman, presented as a talk at The Society of Authors' Childens's Writers & Illustrators Conference (2002), and reprinted in Daemon Voices: Essays on Storytelling (David Fickling Books, 2017). All rights reserved by the author.

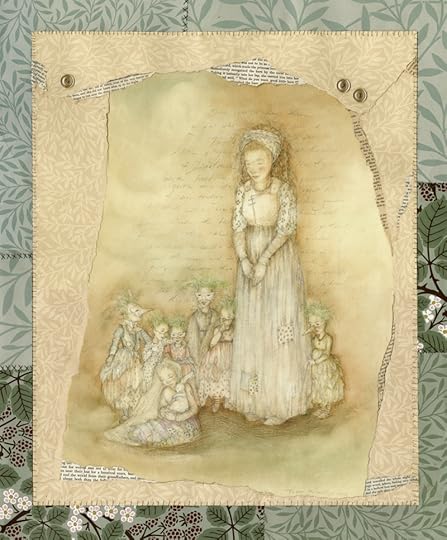

Pictures: The drawings and paintings of shy and whimsical creatures of the green Devon hills are mine. All rights reserved.

July 30, 2019

On the care and feeding of daemons

In Common Air, the brilliant American cultural philosopher Lewis Hyde reflects on the subject of creative inspiration:

"If we go all the way back to the ancient world, to the old bardic and prophetic traditions, what we find is that men and women are not thought to be authors so much as vessels through which other forces act and speak. Norse legends tell of a spring at the root of the World Tree whose water bubbles up from the underworld, carrying the dissolved memories of the dead. Odin drank from it once; that cost him an eye, but nonetheless empowered him to bestow on worthy poets the mead of inspiration. Homer is not the 'author' of the Odyssey; he disappears after the first line: 'Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story....' Hesiod's voice is not his own; in The Theogony he has it from the muses of Mount Helicon and in Works and Days from the muses of Pieria. Plato presents no ideas that he himself made up, only the recovered memory of things known before the great forgetting we call birth.

"Creativity in ancient China was not self-expression but an act of reverence toward earlier generations and the gods. In the Analects, Confucius says, 'I have transmitted what was taught to me without making up anything of my own. I have been faithful to and loved the Ancients.' "

Hyde also discusses creativity and authorship in his seminal book The Gift, writing:

"The task of setting free one's gifts was a recognized labor in the ancient world. The Romans called a person's tuletary spirit his genius. In Greece it was called a daemon. Ancient authors tell us that Socrates, for example, had a daemon who would speak up when he was about to do something that did not accord with his true nature. It was believed that each man had his idios daemon, his personal spirit which could be cultivated and developed. Apuleius, the Roman author of The Golden Ass, wrote a treatsie on the daemon/genius, and one of the things he says is that in Rome it was the custom on one's birthday to offer a sacrifice to one's own genius. A man didn't just receive gifts on his birthday, he would also give something to his guiding spirit. Respected in this way the genius made one 'genial' -- sexually potent, artistically creative, and spiritually fertile.

"According to Apuleius, if a man cultivated his genius through such a sacrifice, it would become a lar, a protective household god, when he died. But if a man ignored his genius, it became a larva or a lemur when he died, a troublesome, restless spook that preys on the living. The genius or daemon comes to us at birth. It carries with us the fullness of our undeveloped powers. These it offers to us as we grow, and we choose whether or not to accept, which means we choose whether or not to labor in its service. For the genius has need of us. As with the elves, the spirit that brings us our gifts finds its eventual freedom only through our sacrifice, and those who do not reciprocate the gifts of their genius will leave it in bondage when they die.

Hyde concludes with a word of warning about the state of daemons in modernity:

"An abiding sense of gratitude moves a person to labor in the service of his daemon. The opposite is properly called narcissism. The narcissist feels his gifts come from himself. He works to display himself, not to suffer change. An age in which no one sacrifices to his genius or daemon is an age of narcissism. The 'cult of the genius' which we have seen in this century has nothing to do with the ancient cult. The public adoration of genius turns men and women into celebrities and cuts off all commerce with the guardian spirits. We should not speak of another's genius; this is a private affair. The celebrity trades on his gifts; he does not sacrifice to them. And without that sacrifice, without the return gift, the spirit cannot be set free. In an age of narcissism the centers of culture are populated with larvae and lemurs, the spooks of unfulfilled genii."

Stephen King takes a more irreverent approach to creative daemons in his essay "The Writing Life":

"There is indeed a half-wild beast that lives in the thickets of each writer's imagination. It gorges on a half-cooked stew of suppositions, superstitions and half-finished stories. It's drawn by the stink of the image-making stills writers paint in their heads. The place one calls one's study or writing room is really no more than a clearing in the woods where one trains the beast (insofar as it can be trained) to come. One doesn't call it; that doesn't work. One just goes there and picks up the handiest writing implement (or turns it

on) and then waits. It usually comes, drawn by the entrancing odor of hopeful ideas. Some days it only comes as far as the edge of the clearing, relieves itself and disappears again. Other days it darts across to the waiting writer, bites him and then turns tail.

"There may be a stretch of weeks or months when it doesn't come at all; this is called writer's block. Some writers in the throes of writer's block think their muses have died, but I don't think that happens often; I think what happens is that the writers themselves sow the edges of their clearing with poison bait to keep their muses away, often without knowing they are doing it. This may explain the extraordinarily long pause between Joseph Heller's classic novel Catch-22 and the follow-up, years later. That was called Something Happened. I always thought that what happened was Mr. Heller finally cleared away the muse repellant around his particular clearing in the woods.

"On good days, that creature comes out of the thickets and sits for a while, there in one's writing place. If one is in another place, it usually comes there (often under duress; most writers find their muses do not travel particularly well, although Truman Capote said his enjoyed motel rooms). And it gives. Some days it gives a little. Some days it gives a lot. Most days it gives just enough. During the year it took to compose my latest novel, mine was extraordinarily generous, and I am grateful.

"Okay, that's the lyric version, so sue me. You'd lose. It's not untrue, just lyrical. It's told as if the writing were separate from the writer. It's probably not, but it often feels that way; it feels as if the process is happening on two separate levels at the same time. On one, at this very moment, I'm just sitting in a room I call my writing room. It's filled with books I love. There's a Western-motif rug on the floor. Outside is the garden. I can see my wife's daylilies. The air conditioner is soft, soft -- white noise, almost. Downstairs, my oldest grandson is coloring, and cupboards are opening and closing. I can smell gingerbread. Laura Cantrell is on the iTunes, singing 'Wasted.'

"This is the room, but it's also the clearing. My muse is here. It's a she. Scruffy little mutt has been around for years, and how I love her, fleas and all. She gives me the words. She is not used to being regarded so directly, but she still gives me the words. She is doing it now. That's the other level, and that's the mystery. Everything in your head kicks up a notch, and the words rise naturally to fill their places. If it's a story, you find the scene and the texture in the scene. That first level -- the world of my room, my books, my rug, the smell of the gingerbread -- fades even more. This is a real thing I'm talking about, not a romanticization. As someone who has written with chronic pain, I can tell you that when it's good, it's better than the best pill.

"But there's no shortcut to getting there. You can build yourself the world's most wonderful writer's studio, load it up with state-of-the-art computer equipment, and nothing will happen unless you've put in your time in that clearing, waiting for Scruffy to come and sit by your leg. Or bite it and run away."

Words: The passages by Lewis Hyde are from Common As Air: Revolution, Art, & Ownership (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2010) and The Gift: Imagination & The Erotic Life of Property (Vintage, 1983) -- both of which I highly recommend. The passage by Stephen King is from "The Writing Life" (The Washington Post, October 1, 2006). The poem excerpt in the picture captions is from "October" by Audre Lorde, Chosen Poems, Old & New (W.W. Norton, 1982). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: A walk by the River Teign, near Fingle Bridge, with a little wet daemon. The drawing is by John D. Batten (1860-1932).

July 27, 2019

Fly away, fly away

I'll be away for a long weekend, then back in the studio sometime on Monday, and back to Myth & Moor on Tuesday. I hope your own weekend is full of magic.

July 26, 2019

Myth & Moor news

I've very delighted, and enormously surprised, that Myth & Moor has been nominated for the World Fantasy Award. Congratulations to my fellow nominees; I am honoured to be in your company.

Tilly is happy about the nomination too, and wants to know if dog treats are involved.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers