Terri Windling's Blog, page 58

June 25, 2019

The names of mosses

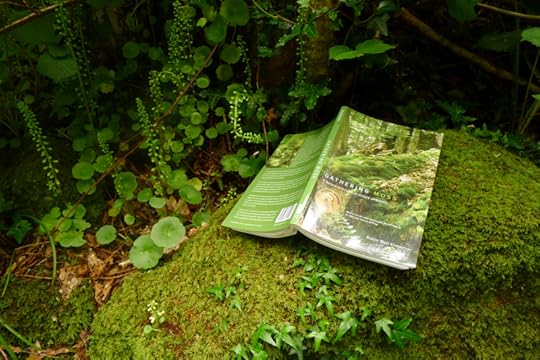

Gathering Moss: A Natural & Cultural History of Mosses is Robin Wall Kimmerer's first book, for which she won the John Burroughs Medal for Natural History Writing in 2005. As in her second, better-known book, Braiding Sweetgrass, this text is written from the liminal place between two ways of understanding the natural world: through Kimmerer's training as a botanist, biologist, and environmental scientist, and through her relationship with plants as an indigenous woman of the Potawatomi Nation.

In the introductory chapter of Gathering Moss, Kimmerer relates as uncanny experience at the Cranberry Lake Biological Station: a forested wilderness in the Adirondack Mountains of New York state. This remote region, accessible only by boat, was deeply familiar to her, for she had studied its mosses, lichens and other plants for many years -- first as a student, and then as a professor leading students there herself. On this particular day, however, she was stunned to discover something new:

In the introductory chapter of Gathering Moss, Kimmerer relates as uncanny experience at the Cranberry Lake Biological Station: a forested wilderness in the Adirondack Mountains of New York state. This remote region, accessible only by boat, was deeply familiar to her, for she had studied its mosses, lichens and other plants for many years -- first as a student, and then as a professor leading students there herself. On this particular day, however, she was stunned to discover something new:

"I've walked this path more times than I can tell you," she writes, "and yet it was only today I was able to see them: five stones, each the size of a school bus, lying together in a pile, their curves fitting together like an old married couple secure in each other's arms. The glacier [which formed the landscape] must have pushed them into this loving conformation and then moved on.

"I circle all around the pile, in silence, brushing my fingertips over its mosses.

"On the eastern side, there is an opening, a cave-like darkness between the rocks. Somehow I knew it would be there. This door which I have never seen before looks strangely familiar. My family comes from the Bear Clan of the Potawatomi. Bear is the holder of medicine knowledge for the people and has a special relationship with plants. He is the one who calls them by name, who knows their stories. We seek him for a vision, to find the task we were meant for. I think I'm following a Bear."

Kimmerer crawls into the darkness between two boulders, following the sandy floor downward and around a corner, where a green light shines ahead.

"I think I must have crawled through a passage leading from beneath this pile of rock and out the other side. I wriggle from the tunnel and find myself not in the woods at all. Instead, I emerge into a tiny, grass-filled meadow, a circle enclosed by the walls of the stone. It is a room, a light-filled room like a round eye looking into the blueness of the sky. Indian paintbrush is in bloom and hay-scented fern borders the ring of the standing stones. I am inside the circle. There are no openings save the way that I have come and I sense that entrance closing behind me. I look all around the ring but I can no longer see the opening in the rock. At first I'm afraid, but the grass smells warm in the sunshine and the walls drip with mosses. How odd to hear the redstarts calling in the trees outside, in a parallel universe that dissipates like a mirage as the mossy walls enclose me.

"Within the circle of the stones, I find myself unaccountably beyond thinking, beyond feeling. The rocks are full of intention, a deep presence attracting life. This is a place of power, vibrating with energy exchanged at a very long wavelength. Held in the gaze of the rocks, my presence is acknowledged.

"The rocks are beyond slow, beyond strong, and yet yielding to a soft green breath as powerful as a glacier, the mosses wearing away their surfaces, grain by grain bringing them back slowly to sand. There is an ancient conversation going on between mosses and rocks, poetry to be sure. About light and shadow and the drift of continents. This is what has been called the 'dialectic of moss on stone -- an interface of immensity and minuteness, of past and present, softness and hardness, stillness and vibrancy, yin and yang.' The material and the spiritual live here together.

"Moss communities may be mysteries to scientists, but they are known to one another. Intimate partners, the mosses know the contours of the rocks. They remember the route of rainwater down a crevice, the way I remember the path to my cabin. Standing inside the circle, I know that mosses have their own names, which were theirs long before Linnaeus, the Latinezed namer of plants. Time passes.

"I don't know how long I was gone, minutes or hours. For that interval, I had no sensation of my own existence. There was only rock and moss. Moss and rock. Like a hand laid gently on my shoulder, I come back to myself and look around. The trance is broken. I can hear the redstarts again, calling overhead. The encircling walls are radiant with mosses of every kind, and I see them again, as if for the first time. The green and the gray, the old and the new in this place and in this time, they rest together for this moment between glaciers. My ancestors knew that rocks hold the Earth's stories, and for a moment I could hear them.

"My thoughts feel noisy here, an annoying buzz disrupting the slow conversation among the stones. The door in the wall has reappeared and time starts to move again. An opening into this circle of stones was made, and a gift given. I see things differently, from the inside of the circle as well as from the outside. A gift comes with responsibility. I had no will at all to name all the mosses in this place, to assign their Linnean epithets. I think the task given to me is to carry out the message that mosses have their own names. Their way of being in the world cannot be told by data alone. They remind me to remember that there are mysteries for which a measuring tape has no meaning, questions and answers that have no place in the truth about rocks and mosses.

"The tunnel seems easier on the way out. This time I know where I am going. I look back over my shoulder at the stones and the set my feet to the familiar path for home. I know I am following the Bear."

Words: The passage above is from Gathering Moss by Robin Wall Kimmerer (Oregon State University Press, 20013). The quote within Kimmerer's text is from Moss Gardening by George Schenk (Timber Press, 1997). The poem in the picture captions is from Weaving the Boundary (Arizona Press, 2016). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Photographs of the mossy woods of Devon, and a vintage drawing of a black bear (artist unknown).

Related posts: Loving the wounded world and The magic of the world made visible.

June 24, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

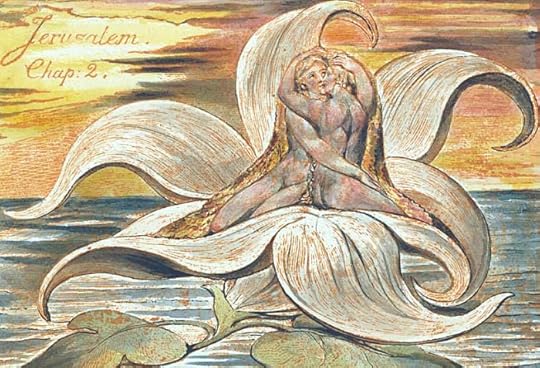

This week, music inspired by the poetry of Blake, Coleridge, and Yeats....

Above: "Jerusalem" by English singer/songwriter Chris Wood, based on the poem by William Blake (1757-1827). The song is from Wood's album None The Wiser (2013), performed at the Green Backyard in Peterborough (2014).

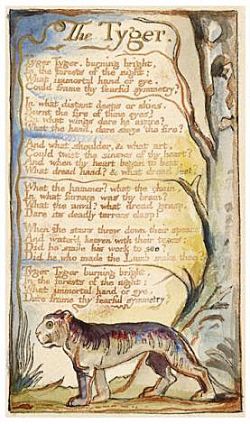

Below: "The Tyger" by American singer/songwriter Greg Brown, based on the poem by Blake. It's from Brown's album of Blake-inspired works, Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1986).

Above: "Kubla Khan" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), with music by English singer/songwriter Ange Hardy and artwork by Tamsin Rosewell. The piece is from Hardy's album Esteesee, containing songs based on the poet's life and work.

Below: The title song of Hardy's album, performed live with Lukas Drinkwater. Coleridge disliked his name so much he would write it phonetically as Esteesee.

Above: "Golden Apples of the Sun," performed by American folksinger Judy Collins, based on the poem "The Song of the Wandering Aengus" by William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), with music by Travis Edmondson. The song is from Collin's classic album Golden Apples of the Sun (1962).

Below: "The Stolen Child" by Canadian singer/songwriter and Celtic music scholar Loreena McKennitt, based on the poem by Yeats. The song appeared on McKennitt's album Elemental (1985). This live performance was filmed the same year.

It's been a good week for contemporary poetry. In the U.S., Joy Harjo of the Mvskoke/Creek Nation has just been named Poet Laureate, and will be the first Native American writer in the role since its establishment 82 years ago. (William Jay Smith, Poet Laureate from 1968-1970, was of Choctaw ancestry but not a tribal member.) Harjo is an activist as well as a poet and says she will use her appointment to put a spotlight on First Nations writers, which is welcome news indeed. Go here for a short video of Harjo talking about this at the Academy of American of Poets.

It's been a good week for contemporary poetry. In the U.S., Joy Harjo of the Mvskoke/Creek Nation has just been named Poet Laureate, and will be the first Native American writer in the role since its establishment 82 years ago. (William Jay Smith, Poet Laureate from 1968-1970, was of Choctaw ancestry but not a tribal member.) Harjo is an activist as well as a poet and says she will use her appointment to put a spotlight on First Nations writers, which is welcome news indeed. Go here for a short video of Harjo talking about this at the Academy of American of Poets.

In the UK, Alice Oswald has just been named Oxford Professor of Poetry, and is the first woman to serve in that position since it was establish three centuries ago, in 1708. Alice currently lives on the other side of Dartmoor, and is a friend of ours (her husband, playwright Peter Oswald, runs a theatre company with my husband Howard), so we're especially delighted by this news. Go here for a short interview with Alice about her multi-award-winning book Falling Awake.

Artwork above by William Blake.

June 23, 2019

Daily magic

This is Benji, our neighbour's sweet, elderly horse, who lives in a field just down the road. His companion horse died last year, and now many of us stop by regularly to bring him a treat or have a chat and make sure he's not lonely.

"There's a flame of magic inside every stone and every flower, every bird that sings and every frog that croaks. There's magic in the trees and the hills and the river and the rocks, in the sea and the stars and the wind, a deep, wild magic that's as old as the world itself. It's in you too, my darling girl, and in me, and in every living creature, be it ever so small. "

- Kate Forsyth (The Puzzle Ring)

There is certainly magic in Benji, and the love he inspires in everyone.

June 20, 2019

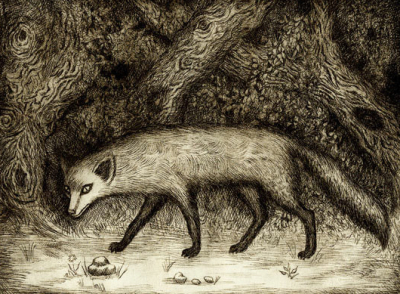

The tang of fox

As must be evident from my last post, I've been re-reading Scatterlings by storyteller, writer, and mythographer Martin Shaw -- and finding it just as rich, insightful, and magical as I did the first time around. Martin, who grew up a stone's throw from Dartmoor, runs the West Country School of Myth on the other side of the moor from us, and is soaked in the mythic history of the West Country through and through. In the pages of Scatterlings, he rambles the moor, shares its lore, and describes an apprenticeship in storytelling that is earthy, tricksy, and rooted firmly in the land. His work is geared to storytellers working in the old oral tradition, but it has much to say to those of us writing land-based fiction and nonfiction too.

The passage from the book that I'd like to share today begins with a story:

"Once upon a time," he writes, "there was a lonely hunter. One evening, returning to his hut over the snow, he saw smoke coming from his chimney. When he entered the shack, he found a warm fire, a hot meal on the table, and his threadbare clothes washed and dried. There was no one to be found.

"The next day, he doubled back early from hunting. Sure enough, there was again smoke from the chimney, and he caught the scent of cooking. When he cautiously opened the door, he found a fox pelt hanging from a peg, and a woman with long red hair and green eyes adding herbs to a pot of meat. He knew in the way that hunters know that she was Fox-Woman-Dreaming, that she had walked clear out of the Otherworld. 'I am going to be the woman of this house,' she told him.

"The hunter's life changed. There was laughter in the hut, someone to share in the labour of crafting a life, and, in the warm dark when they made love, it seemed the edges of the hut dissolved in the vast green acres of the forest and the stars.

"Over time, the pelt started to give off its wild, pungent scent. A small price, you would think, but the hunter started to complain. The hunter could detect the scent on his pillow, his clothes, even his own skin. His complaints grew in number until one night the woman nodded, just once, her eyes glittering. In the morning she, and the pelt, and the scent were gone. It is said that to this day the hunter waits by the door of his hut, gazing over snow, lonely for even a glimpse of his old love.

"We are that hunter, socially and, most likely, personally. The smell of the pelt is the price of real relationship to wild nature: its sharp, regal, undomesticated scent. While that scent is in our hut there can be no Hadrian's Wall between us and the world.

"Somewhere back down the line, the West woke up to the Fox Woman gone. And when she left, she took many stories with her. And, when the day is dimming and our great successes have been bragged to exhaustion, the West sits, lonely in its whole body for her. For stories are more than just a dagger between our teeth. More than just a bellow of conquest. We have turned our face away from the pelt. Underneath our wealth, the West is a lonely hunter.

"Around halfway through the last century, something wonderful happened. Mythology and faerie tales regained a legitimacy amongst adults as a viable medium for understanding the workings of their own psychological lives. By use of metaphor, tales of sealskins and witches' huts became the most astonishing language for what seemed to lurk underneath people's everyday encounters. The use of metaphor granted greater dignity and heightened poetics to the shape of their years.

"What was the glitch that lurched alongside? A little too much emphasis on these stories as entirely interior dramas that, clumsily handled, became something that removed, rather than forged, relationship to the earth. The inner seemed more interesting than anything going on 'out there.' We and our feelings still squatted pretty happily at the center of the action. There was not always that sharp tang of fox.

"When the Grimms and others collected folktales, they effectively reported back the skeletons of stories; the local intonation of the teller and some regional sketching out was often missing. Ironically, this stripped-back form of telling has been adopted into the canon as a kind of traditional style that many imitate when telling stories -- a kind of 'everywhere and nowhere' style.

"Now, while it's certainly true that there are stories designed for travel, for thousands of years even a story arriving in an entirely new landscape would be swiftly curated into the landscape of its new home. It would shake down its feathers and shape-leap a little or grow silent and soon cease to be told. No teller worth his or her salt would just stumble through the outline and think it was enough; the vivid organs would be, in part, the mnemonic triggers of the valley or desert in which the story now abided. This process was a protracted courtship to the story itself. It was the business of manners.

"Oral culture has always been about local embedding, despite the big human dilemmas that cannot help but sweep up between cultures. This may seem an unimportant detail when you are seeking only to poke around your childhood memories in a therapist's office, but it falls woefully short when this older awareness is reignited -- the absence of wider nature becomes acute, the tale flat and self-centered.

"I don't think we have the stories; the stories have us. They charge vividly through our betrayals, illicit passions, triumphs, and generosities. Pysche is not neatly contained in our chest as we scuttle between appointments; we dwell within psyche: gregarious, up close, chaotic, astonishing, sometimes tragic, often magical.

"Well, something piratical is happening. It is time to rescue the stories, rehydrate the language, scatter dialectic inflection amongst the blunt lines of anthropological scribbles, and muck up the typewriter with the indigo surge of whale ink. We're singing over the snow to the fox-woman."

And indeed, we are.

The very beautiful art today is by Simon Blackbourn, who lives and works here in Chagford. He has spent the last ten years immersing himself in Dartmoor, photographing its colours, shapes, textures and moods, its trees, rocks, bogs, rivers, wildlife, and weather. To me, this is the perfect pairing with Martin Shaw's words, for both of them illuminate the soul of the moor through the mediums of language and light.

To see more of Simon's work, please visit his Instagram page. You'll find the title of each piece here in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to view them.)

The passage above is by Scatterlings: Getting Claimed in the Age of Amnesia by Martin Shaw (White Cloud Press, 2016), which I highly recommend. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

On the longest day

"This is the solstice, the still point of the sun, its cusp and midnight, the year's threshold and unlocking, where the past lets go of and becomes the future; the place of caught breath. " - Margaret Atwood

The hound and I wish you a blessed Summer Solstice.

June 19, 2019

The stories we need

From Scatterlings by Martin Shaw:

"We hear it everywhere these days: time for a new story -- some enthusiastic sweep of narrative that becomes, overnight, the myth of our times. A container for all this ecological trouble, this peak-oil business, this malaise of numbness that seems to shroud even the most privileged. A new story. Just the one. That simple. Painless. Everything solved. Lovely and neat.

"So, here's my first moment of rashness: I suggest that the stories we need turned up, right on time, about five thousand years ago. But they're not simple, neat, or painless. I also think this urge for a new story is the tourniquet for a less articulated desire: to behold the earth actually speaking through words again, more than through some shiny, new, never-considered thought. We won't get a story worth hearing until we witness a culture broken open by its own consequence.

"No matter how unique we think our own era, I believe that these old tales -- faerie tales, folktales, and myths -- contain much of the paradox we face in these storm-jagged times. And what's more, they have no distinct author, are not wiggled from the penned agenda of one brain-rattled individual, but have passed through the breath of countless number of oral storytellers.

"Second thought: The reason for the purchase of these tales is that the deepest of them contain not just -- as is widely reported -- the most succulent portions of the human imagination, but a moment when our innate capacity to consume (lovers, forests, oceans, animals, ideas) was drawn into the immense thinking of the earth itself, what aboriginal teachers call 'Wild Land Dreaming.'

"We met something mighty. We didn't just dream our carefully individuated thoughts: We. Got. Dreamt. We let go of the reins.

"Any old Gaelic storyteller would roll his eyes, stomp his boot, and vigourously jab a tobacco-browned finger toward the soil if there was a moment's question of a story's origin.

"In a time when the land and sea suffer by our very directive, could it not be that the stories we need contain not just a reflection on, but the dreaming of a sensual, powerful, reflective earth?

"It is an insult to archaic cultures to suggest that myth is a construct of humans shivering fearfully under a lightning storm or gazing at a copse and reasoning a supernatural narrative. To make such a suggestion implies a baseline of anxiety, not relationship. Or that anxiety is the primary relationship.

"It places full creative impetus on the human, not on the sensate energies that surround and move through them. It shuts down the notion of a dialogue worth happening; it shuts down that big old word animism.

"Maybe the ancient storyteller knew something we've forgotten."

Words: The passage above is by Scatterlings: Getting Claimed in the Age of Amnesia by Martin Shaw (White Cloud Press, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from Secrets from the Center of the World by Joy Harjo, of the Mvskoke/Creek Nation, with photographer Stephen Strom (University of Arizona Press, 1989). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The Chagford stretch of the River Teign, as it runs from Dartmoor to the sea.

Related posts: Trailing stories, Working with words, The love of poets, and The story made of dawn.

Myth & Moor update

I'm out of the studio due to health problems, but I'm hoping to martial my strength with rest today and be back in tomorrow morning.

"The creative act," wrote Terrance McKenna, "is a letting down of the net of human imagination into the ocean of chaos on which we are suspended, and the attempt to bring out of it ideas. It is the night sea journey, the lone fisherman on a tropical sea with his nets, and you let these nets down -- sometimes, something tears through them that leaves them in shreds and you just row for shore, and put your head under your bed and pray. At other times what slips through are the minutiae, the minnows of this ichthyological metaphor of idea chasing. But, sometimes, you can actually bring home something that is food, food for the human community that we can sustain ourselves on and go forward."

Tomorrow, I hope, we shall keep moving forward through myth and art together ... slowly, perhaps, but steadily onward.

Recommended reading: "Animal Allies: Healing and Empowering Children" by Brenda Peterson (author of Wolf Nation, Build Me An Ark,etc.); and an interview with Robert Macfarlane on his new book, Underland.

June 18, 2019

Carrying stories

In most indigenous cultures (including those of pre-Christian Europe), stories were preserved and passed on via oral transmission, not the written word. Such stories, David Abram notes, were often bound to the places where they were told,

"attuned in countless subtle and complex ways to the specific topography, textures, tones, and rhythms of the local earth. Moreover, traditional oral tales commonly hold, in their layered adventures, specific information regarding local animals and plants (how best to hunt particular creatures and how to prepare their skins for clothing or shelter; which plants are good for treating particular ailments; how to prepare them in poultices, or as potions...), as well as particular instructions regarding the forms of ritual blessing necessary to ensure a liveable life in that region.

"And why is oral culture so deeply place-based? Well, because there's simply no way to remember many of the old stories of a nonwriting, oral culture without now and then encountered the sites -- the waterholes, forested mountainsides, clustered boulders, and tight river bends where those storied events once happened or are felt to have happened.

"For most of us today, born of a highly literate civilization, printed books are the primary mnemonic -- the primary memory-trigger -- for activating the accumulated knowledge that's been stored up by our ancestors over many generations. We turn to books when we wish to recall some of the old stories or to access the practical knowledge those stories hold. Yet for communities without any highly formulized system of writing -- for cultures without books -- the animate, expressive landscape itself carries the stories. Only by encountering over and over again those clustered boulders, the mouth of that deep cave, the cliff-edge vista or wooded peninsula or mist-covered swamp, are we continually brought to recall the storied events that happened there and the detailed ancestral knowledge stored in those stories.

"Similarly, when we hear the yip-yipping of coyotes or come on the tracks of a grizzly by the half-eaten carcass of a spawned-out salmon, we can't help but recall yet another tale in which that bushy-tailed trickster, or old Honey-Paws, or perhaps even the Salmon of Wisdom figures as a central character. For in the absence of books, the animate, expressive terrain itself is the mnemonic, or memory-trigger, for remembering the oral tales.

"For this reason, the old, oral-tradition stories tend to be deeply entangled with the phythm and pulse of particular places. Although its sometimes hard for highly literate folk to sense, there's an indissoluable rapport between an indigenous storyteller and the lilt of the local land; he may feel that, by intoning a tale, he is translating secret or sacred matters overheard from the speaking earth. That is how Sean Kane puts it, in his wonderful book Wisdom of the Myth-tellers: 'Myth, in its most ecologically discreet form, among people who live by hunting and fishing and gathering, seems to be the song of the place to itself, which humans overhear.'

"Or as Martin Shaw insightfully frames it [in Scatterlings]: a really fine storyteller, by the eloquent practice of her art, is carefully echoing signals emanating from the expressive terrain around her; the teller is participant in a subtle process of echolocation, by which the deep earth speaks, and listens, and returns to itself, nourished."

David is troubled by the way our digital and print-based culture has severed these kinds of stories from their natural settings:

"If the strongest tales are best understood as the place speaking through the teller, well, writing down those tales would seem to interrupt this direct transmission. For the written stories can now be carried elsewhere, and within a short time they can be read -- by mutiple others -- in distant cities and even on distant continents. Since the story no longer neatly matches the contour of the strange new terrain where its being read (since it cannot aptly echo, or invoke, the many-voiced landscape that surrounds the reader wherever she finds herself) the tale now seems to float free of the ground. Soon enough, all of the place-specific savvy contained in that tale, regarding the precise song for calling a particular creature or the precise technique for harvesting certain vision-inducing herbs, is forgotten." *

But other writers are exploring the ways written text might be crafted so as to echo the power of the old oral tales: through the rhythms of the language, integrity of intention, and a careful attention to place -- even when, as in fantasy fiction, that place is an imaginary one. Here in the fantasy field especially, full of novels and stories deeply rooted in folklore, magic, and the mythic landscape, I believe it is possible for writers, too, to participate in the "subtle process of echolocation" ... and not only possible, but timely and necessary for those concerned with our culture's fractured relationship to the natural world.

Ursula K. Le Guin once said:

"The proper, fitting shape of the novel might be that of a sack, a bag. A book holds words. Words hold things. They bear meanings. A novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us."

Fantasy literature, like the old oral stories, can hold powerful "medicine," and speak across the liminal space between the human and more-than-humen world.

Patricia J. Williams writes (in The Rooster's Egg):

"From time to time, I try to imagine a culture ... in whose mythology words were conceived as vessels for communications from the heart; a society in which words are holy, and the challenge of life is based upon the quest for gentle words, holy words, gentle truths, holy truths. I try to imagine for myself a world in which the words one gives one's children are the shell into which they shall grow, so one chooses one's words carefully, like precious gifts, like magnificent gifts, like magnificent inheritances, for they convey an excess of what we have imagined, they bear gifts beyond imagination, they reveal and revisit the wealth of history.

"How carefully, how slowly, and how lovingly we might step into our expectations of each other in such a world."

I try to imagine such things too. And to turn these ideas into stories.

* For a more detailed discussion of this thesis, see David Abram's first book, The Spell of the Sensuous .

Words: The Abram quote is from his introduction to Scatterlings by Martin Shaw (White Cloud Press, 2016). The Le Guin quote is from her essay "The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction," published in Dancing at the Edge of the World (Tor Books, 1997). The Williams quote is from her book The Rooster's Egg: On the Persistence of Prejudice (Harvard University Press, 1997). The poem in the picture captions is from The Branch Will Not Break by James Wright (Wesleyan University Press, 1992). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Photographs of Dartmoor ponies and their foals on our village Commons, and a drawing by William Heath Robinson (1872-1944).

June 16, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, folk/bluegrass/American roots music from the troubled, soulful, very beautiful country I was born in....

Above: "Here and Heaven" by classical cellist Yo-Yo Ma, mandolin master Chris Thile, bluegrass fiddler Stuart Duncan, bassist Edgar Meyer, and singer/songwriter Aoife O'Donovan. It's from their collaborative album The Goat Rodeo Sessions (2011), which I highly recommend.

Below: "Overland" by I'm With Her (Aoife O'Donovan, Sara Jarosz, and Sara Watkins), from their first album together, See You Around (2018). The video is by Tobias LaMontagne.

Above: "American Flowers" by Birds of Chicago (husband-and-wife folk/roots duo JT Nero and Allison Russell), with Rhiannon Giddens and Steve Dawson. The song is from their EP of the same name (2017).

Below: "Remember Wild Horses" by Birds of Chicago, from an earlier album, Real Midnight (2016).

"Saint Valentine" by Gregory Alan Isakov, performed with his band and The Ghost Orchestra in Los Angeles in 2017. The song appeared on Isakov's 5th album, The Weatherman (2013).

"The Universe" by Gregory Alan Isakov, also from The Weatherman, performed with his band in Colorado Springs in 2015.

Above: "Mother Deer" by Mandolin Orange (Andrew Marlin and Emily Frantz) and their band. The song is from their new album Tides of a Teardrop (2019).

Below: "The Wolves" by Mandolin Orange, also from the new album.

The art today is by Kelly Louise Judd, a painter and illustrator based in Kansas City whose work is inspired by folklore, ghost stories, Victoriana, animals, and nature. Please visit her website to see more.

June 13, 2019

When you enter the woods...

"When you enter the woods of a fairy tale, it is night and trees tower on either side of the path. They loom large because everything in the world of fairy tales is blown out of proportion. If the owl shouts, the otherwise deathly silence magnifies its call. The tasks you are given to do (by the witch, by the stepmother, by the wise old woman) are insurmountable -- pull a single hair from the crescent moon bear's throat; separate a bowl's worth of poppy seeds from a pile of dirt. The forest seems endless. But when you do reach the daylight, triumphantly carrying the particular hair or having outwitted the wolf; when the owl is once again a shy bird and the trees only a lush canopy filtering the sun, the world is forever changed for your having seen it otherwise.

"From now on, when you come upon darkness, you'll know it has dimension. You'll know how closely poppy seeds and dirt resemble each other. The forest will be just another story that has absorbed you, taken you through its paces, then cast you out and sent you back home again."

- Elizabeth J. Andrew (On the Threshold)

"Step across the boundary and the trespass of story will begin. The forest takes a deep breath and through its whispering leaves an incipient adventure unfurls. The quest. In the lull -- not the drowsy lull of a lullaby but the sotto voce of a woodland clearing, scented with story as it is with with wild garlic -- this is the moment of beginning, the pause on the threshold before the journey. So many tales begin here, hard by a great forest...."

- Jay Griffiths (Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape)

"I did not want to think about people. I wanted the trees, the scents and colors, the shifting shadows of the wood, which spoke a language I understood. I wished I could simply disappear in it, live like a bird or a fox through the winter, and leave the things I had glimpsed to resolve themselves without me."

- Patricia A. McKillip (Winter Rose)

"It���s not by accident that people talk of a state of confusion as not being able to see the wood for the trees, or of being out of the woods when some crisis is surmounted. It is a place of loss, confusion, terror and anger, a place where you can, like Dante, find yourself going down into Hell. But if it���s any comfort, the dark wood isn���t just that. It���s also a place of opportunity and adventure. It is the place in which fortunes can be reversed, hearts mended, hopes reborn."

- Amanda Craig (In a Dark Wood)

"I tell them: don���t depend on a woodsman in the third act. I tell them: look for sets of three, or seven. I tell them: there���s always a way to survive. I tell them: you can���t force fidelity. I tell them: don���t make bargains that involve major surgery. I tell them: you don���t have to lie still and wait for someone to tell you how to live. I tell them: it���s all right to push her into the oven. She was going to hurt you. I tell them: she couldn���t help it. She just loved her own children more. I tell them: everyone starts out young and brave. It���s what you do with it that matters. I tell them: you can share that bear with your sister. I tell them: no-one can stay silent forever. I tell them: it���s not your fault. I tell them: mirrors lie. I tell them: you can wear those boots, if you want them. You can lift that sword. It was always your sword. I tell them: the apple has two sides. I tell them: just because he woke you up doesn���t mean you owe him anything. I tell them: his name is Rumplestiltskin."

- Catherynne M. Valente (The Bread We Eat in Dreams)

"What if we turned the old nursery rhymes and fairytales we all know into feral creatures once again, set them loose in new lands to root through the acorn fall of oak trees? What else is there to do, if we want to keep any of the wildness of the world, and of ourselves?"

- Sylvia Linsteadt ("Turning Our Fairytales Feral Again")

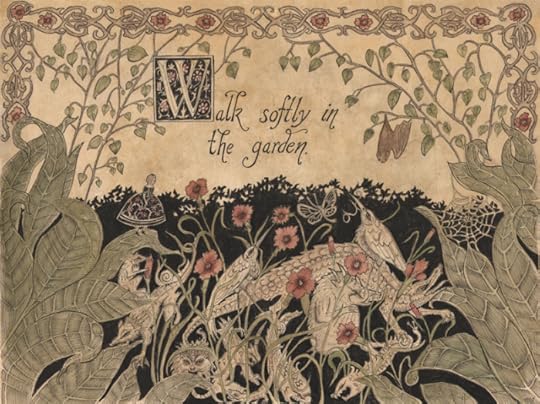

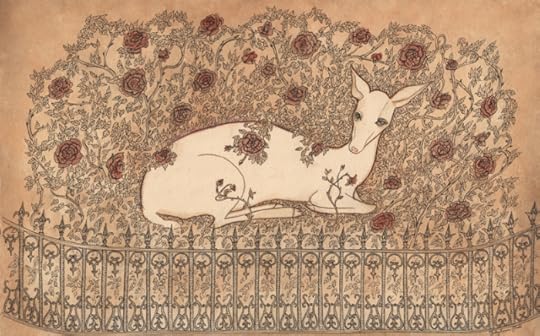

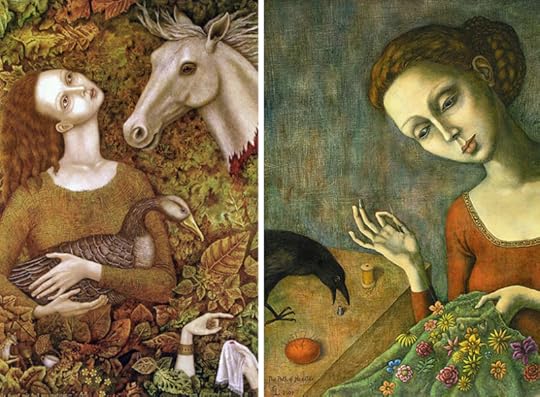

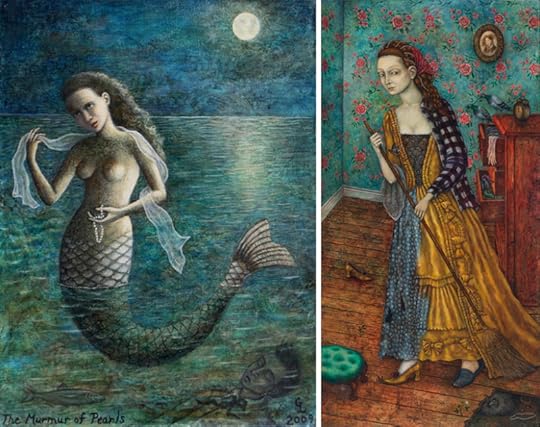

The fairy-tale-infused art today is by American painter Gina Litherland. Born in Gary, Indiana, she received a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1984, and has exhibited in museums and galleries throughout the United States.

"I have always been interested in the interplay between myth, the natural world, and the domain of dreams and memory," she says. "As a child, I spent many hours exploring natural wooded areas and empty lots inhabited by multitudes of insects and wildlife. This, along with a fervent interest in reading, particularly fairy tales, laid the foundation for my current investigations as an artist. Much of my work is inspired by folklore, myth, and literature reflected in my own personal preoccupations, specifically themes of desire, femaleness, the natural world, the human/animal boundary, children's games, ritual, intuition, and memory. The painting techniques that I use, traditional indirect oil painting techniques similar to those used by fifteenth century Sienese painters, combined with textural effects created by using various tools other than the paint brush, allow me to create a detailed, layered, and complex surface of images recreating the experience of looking at the forest floor with its rich blanket of diverse matter in various stages of decay. Suddenly, an object emerges and comes sharply into focus."

"I have always been interested in the interplay between myth, the natural world, and the domain of dreams and memory," she says. "As a child, I spent many hours exploring natural wooded areas and empty lots inhabited by multitudes of insects and wildlife. This, along with a fervent interest in reading, particularly fairy tales, laid the foundation for my current investigations as an artist. Much of my work is inspired by folklore, myth, and literature reflected in my own personal preoccupations, specifically themes of desire, femaleness, the natural world, the human/animal boundary, children's games, ritual, intuition, and memory. The painting techniques that I use, traditional indirect oil painting techniques similar to those used by fifteenth century Sienese painters, combined with textural effects created by using various tools other than the paint brush, allow me to create a detailed, layered, and complex surface of images recreating the experience of looking at the forest floor with its rich blanket of diverse matter in various stages of decay. Suddenly, an object emerges and comes sharply into focus."

Go here to read an interview with the artist by Don LeCoss, and here to see her work in the "Hidden Rooms" show at Corbett vs. Dempsey in Chicago, 2016.

The art by Gina Litherland is: Little Red Cap, In Bloom, Wolf Alice (inspired by an Angela Carter story), Crossing an Iced-over Stream, a wintery figure (title unknown), Queen of An Uncharted Territory, After the Deluge, Reading the Leaves, Goose Girl, The Path of Needles, Lupercalia, fox drawing, Murmur of Pearls, Housekeeping, and Bird Funeral. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and artist.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers