Terri Windling's Blog, page 59

June 13, 2019

The community of the forest

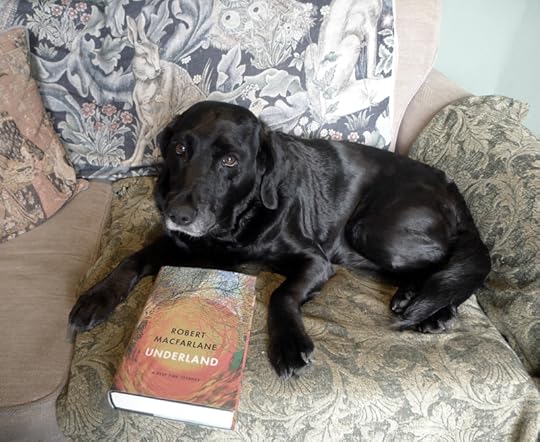

I followed my reading of Richard Powers' The Overstory (discussed yesterday) with Robert Macfarlane's new book, Underland: A Deep Time Journey -- which proved to be a perfect pairing. Underland is an absolutely brilliant exploration of the various underworlds to be found in nature, myth, and literature; and one section of the text is devoted to the complex understorey of forests.

In Chapter 4 of Underland (set in London's Epping Forest), Macfarlane writes:

"In the early 1990s a young Canadian forest ecologist called Susan Simard, studying the understory of logged temperate forests in north-west British Columbia, observed a curious correlation. When paper birch saplings were weeded out from clear-cut and reseeded plantations, their disappearance coincided with first the deterioration and then the premature deaths of the planted Douglas fir saplings among which they grew.

"In the early 1990s a young Canadian forest ecologist called Susan Simard, studying the understory of logged temperate forests in north-west British Columbia, observed a curious correlation. When paper birch saplings were weeded out from clear-cut and reseeded plantations, their disappearance coincided with first the deterioration and then the premature deaths of the planted Douglas fir saplings among which they grew.

"Foresters had long assumed that such weeding was necessary to prevent young birches (the 'weeds') depriving the young firs (the 'crop') of valuable soul resources. But Simard began to wonder whether this simple model of competition was correct. It seemed to her plausible that the paper birches where somehow helping rather than hindering the firs: when they were removed, the health of the firs suffered. If this interspecies aid-giving did exist between trees, though, what was its nature -- and how could individual trees extend help to one another across the spaces of the forest?

"Simard decided to investigate the puzzle. Her first task was to establish some kind of structural basis for possible connections between the trees. Using microscopic and genetic tools, she and her colleagues peeled back the forest floor and peered below the understory, into the 'black box' of the soil -- a notoriously challenging realm of study for biologists. What they saw down there were the pale, super-fine threads known as 'hyphae' that fungi send out through the soil. These hyphae interconnected to create a network of astonishing complexity and extent. Every cubic metre of forest soil that Simard examined held dozens of miles of hyphae.

"For centuries, fungi had generally been considered harmful to plants: parasites that caused disease and dysfunction. As Simard began her research, however, it was increasingly thought that different kinds of common fungi might exist in subtle mutualism with plants. The hyphae of these so-called 'mycorrhizal' fungi were understood not only to infiltrate the soil, but to weave into the tips of plant roots at a cellular level -- thereby creating an interface through which molecular transmission might occur. By means of this weaving, too, the roots of the individual plants or trees were joined to one another by a maginificently intricate subterranean system.

"Simard's enquiries confirmed that beneath her forest floor there did indeed exist what she called an 'underground social network,' a 'bustling community of mycorrhizal fungal species' that linked sapling to sapling. She also discovered that the hyphae made connections between species: joining not only paper birch to paper birch and Douglas fir to Douglas fir, but also fir to birch and far beyond -- forming a non-hierarchical network between numerous kinds of plants.

"Simard had established a structure of connection between the saplings. But the hyphae provided only the means of mutualism. Its existance did not explain why the fir saplings faltered when the birch saplings were weeded out, or details as to what -- if anything -- might be transmitted via this collaborative system. So Simard and her team devised an experiment that could let them track possible biochemical movements along this invisible buried lattice. They decided to inject fir trees with radioactive carbon isotopes. Using mass spectrometers and scintillation counters, they were then able to track the flow of carbon isotopes from tree to tree.

"What this tracking revealed was astonishing. The carbon isotopes did not stay confined to the individual trees into which there were injected. Instead, they moved down the trees' vascular systems to their root tips, where they passed into the fungal hyphae that wove with those tips. Once in the hyphae they travelled along the network to the root tips of another tree, where they entered the vascular system of that new tree. Along the way, the fungi drew off and metabolized some of the photosynthesized resources that were moving along their hyphae; this was their benefit from mutualism.

"Here was proof that trees could move resources around between one another using the mycorrhizal network. The isotope tracking also demonstrated the unexpected intricacy of the interrelations. In a research plot thirty metres square, every single tree was connected to the fungal system, and some trees -- the oldest -- were connected to as many as forty-seven others. The results also solved the puzzle of the fir-birch mutualism: the Douglas firs were receiving more photosynthetic carbon from paper birches than they were transmitting. When paper birches were weeded out, the nutrient intake of the fir saplings was thus -- counter-intuitively -- reduced rather than increased, and so the firs weakened and died.

"The fungi and the trees had 'forged their duality into oneness, thereby making a forest,' wrote Simard in a bold summary of her findings. Instead of seeing trees as individual agents competing for resources, she proposed the forest as a 'co-operative system,' in which trees 'talk' to one another, producing a collaborative intelligence described as 'forest wisdom'. Some older trees even 'nuture' smaller trees that they recognize as their 'kin,' acting as 'mothers'. Seen in the light of Simard's research, the whole vision of a forest ecology shimmered and shifted -- from a fierce free market to something more like a community within a socialist system of resource redistribition."

A little later in the chapter, Macfarlane notes:

"Little of this thinking is new, however, when viewed from the perspective of animist traditions of indigenous peoples. The fungal forest that science had revealed...seemed merely to provide a materialist evidence-base for what the cultures of forest-dwelling peoples have known for thousands of years. Again and again within such societies, the jungle or woodland is figured as aware, conjoined and conversational. 'To dwellers in a wood almost every species of tree has its voice as well as its feature,' wrote Thomas Hardy in Under the Greenwood Tree. The anthropologist Richard Nelson describes how the Koyukon people of the forest interior of what we now call Alaska 'live in a world that watches, in a forest of eyes. A person moving through nature -- however wild, remote...is never truly alone. The surroundings are aware, sensate, personified. They feel.' In such a vibrant environment, loneliness is placed in solitary confinement.'

"There in the grove [of Epping Forest], I recall Kimmerer, Hardy and Nelson, and feel a sudden, angry impatience with modern science for presenting as revelation what indigenous societies take to be self-evident. I remember Ursula Le Guin's angrily political novel, set on a forest planet in which woodland beings known as the Athsheans are able to transmit messages remotely between one another, signalling through the medium of trees. On Athshe -- until the arrival of colonists committed to the planet's exploitation -- the realm of the mind is integrated into the community of trees, and 'the word for world is forest'. "

I highly recommend seeking out Underland and following the author's journey into the dark of the woods, into the mysteries underground, and into the depths of the human psyche.

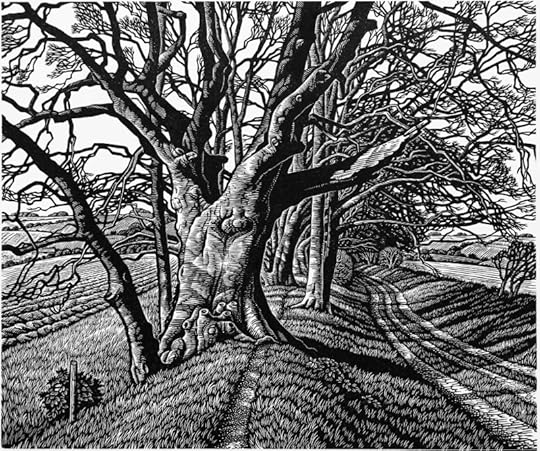

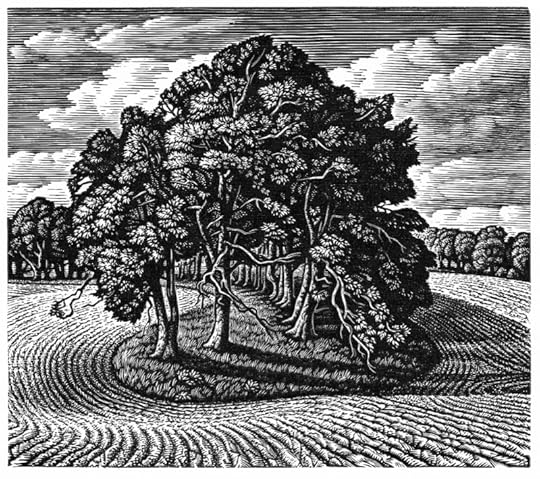

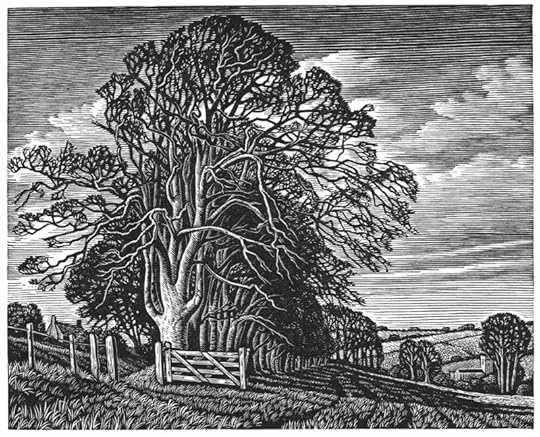

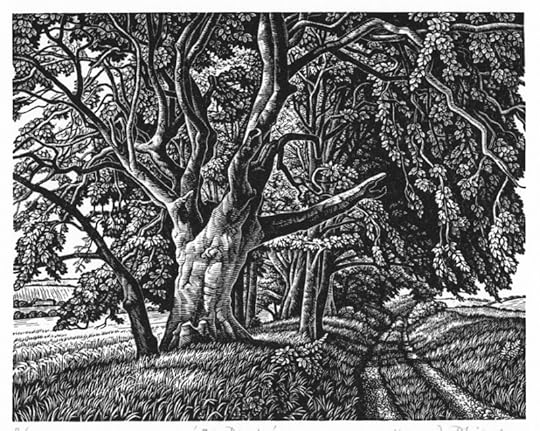

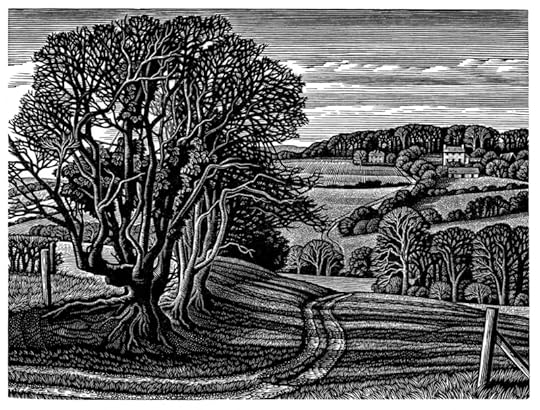

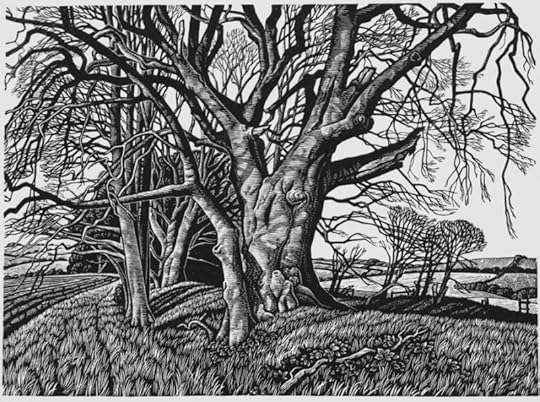

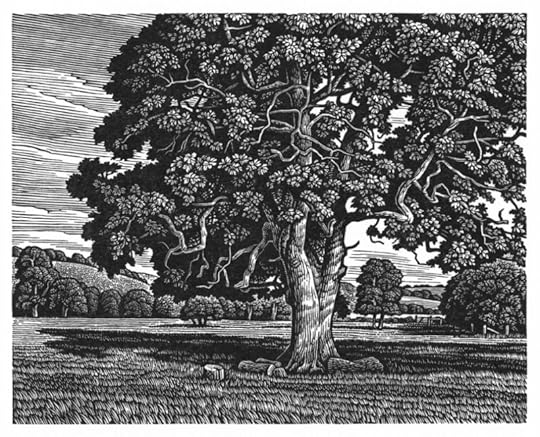

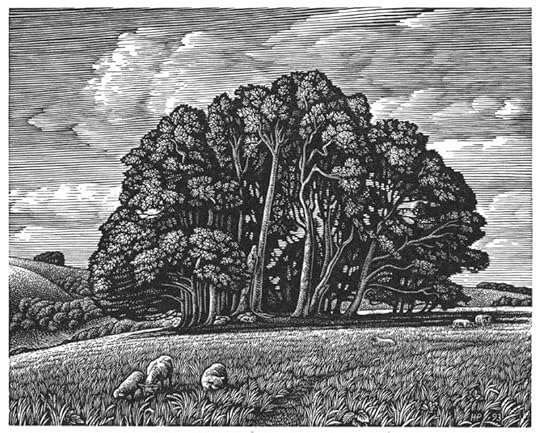

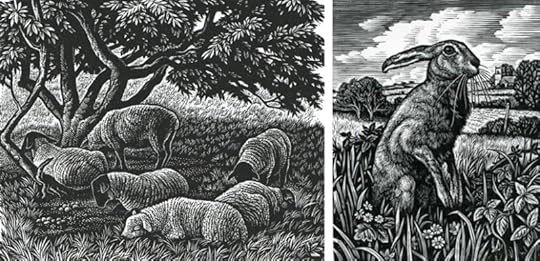

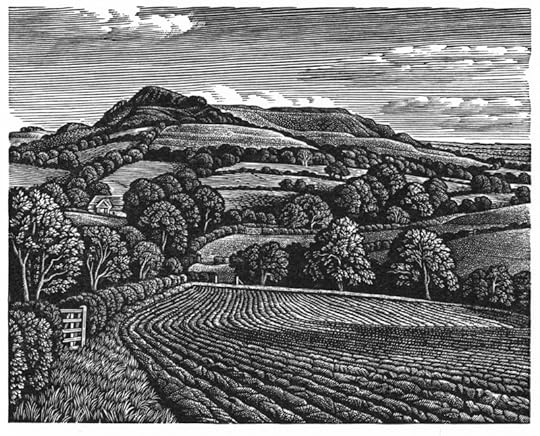

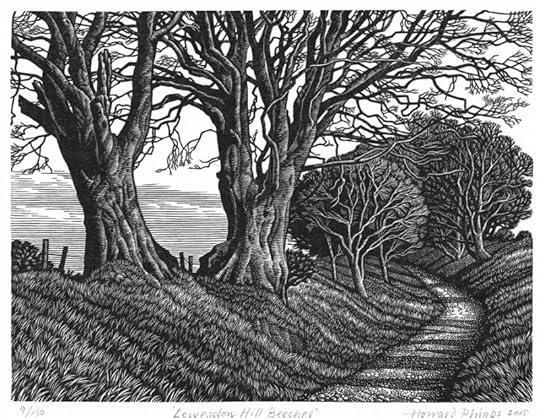

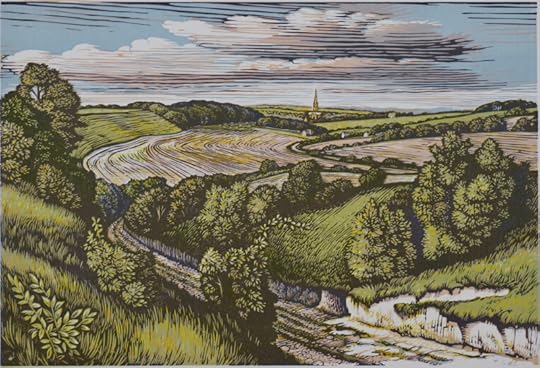

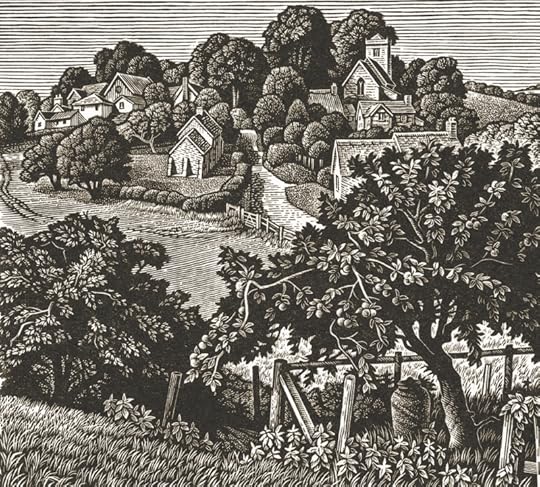

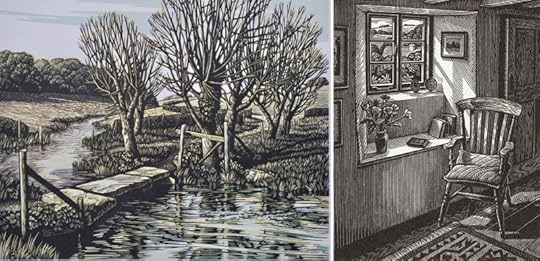

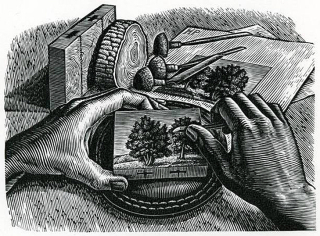

The exquisite arboreal art today is by Howard Phipps: a painter, printmaker and illustrator who specializes in wood engravings. Phipps studied at the Cheltenham Art College and University of Sussex, worked in west Devon the late 1970s, then moved to Salisbury, Wiltshire, where he has been based ever since. A long-standing member of the Royal West of England Academy and The Society of Wood Engravers, his art is widely exhibited throughout the UK; he has also illustrated books for the Folio Society and numerous publishers. (I first came upon his work in the literary journal Slightly Foxed.)

The exquisite arboreal art today is by Howard Phipps: a painter, printmaker and illustrator who specializes in wood engravings. Phipps studied at the Cheltenham Art College and University of Sussex, worked in west Devon the late 1970s, then moved to Salisbury, Wiltshire, where he has been based ever since. A long-standing member of the Royal West of England Academy and The Society of Wood Engravers, his art is widely exhibited throughout the UK; he has also illustrated books for the Folio Society and numerous publishers. (I first came upon his work in the literary journal Slightly Foxed.)

To see more of Howard Phipp's beautiful place-based art, visit Messums Wiltshire, Bircham Gallery, The Society of Wood Engravers, or The Arborealists; or track down copies of his two books of engravings, Interiors and Further Interiors (Whittington Press, 1985 and 1992). I also recommend "A Short Walk With Howard Phipps" on the Frames of Reference blog, which examines the craft of wood engraving and the artist's process.

"Owl hoot. Dog bark. Back in the clearing the fire dims, songs fall silent. The canopy of the pollards spreads above me, whispering in the night breeze. There's something you need to hear....Seeking sleep, my mind follows leaf to branch, branch to trunk, trunk to root and from there down along the hyphnae that web the earth below." - Robert Macfarlane (from Underland)

Words & art: The passages above are from Underland: A Deep Time Journey by Robert Macfarlane (Hamish Hamilton/Penguin, 2019). All rights to the trext and art above reserved by the author and artist.

Related posts: The library of the forest and Knowing the world as a gift.

June 12, 2019

Here by the grace of trees

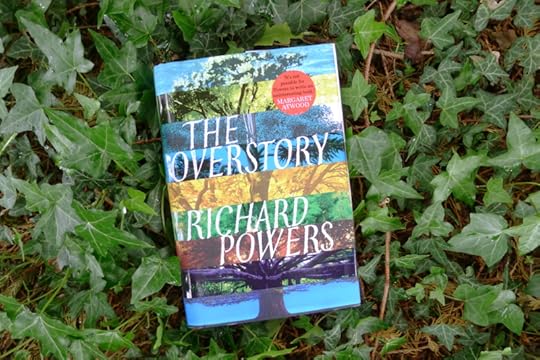

I've finally read Overstory by Richard Powers -- a sprawling novel composed of interlocked stories about people, trees, and the relationship between them -- and I highly recommend it to all who are interested in the intersection of nature, art and story.

Trees do most of the things we do, just more slowly, writes Barbara Kingsolver (in her review of Overstory):

"They compete for their livelihoods and take care of their families, sometimes making huge sacrifices for their children. They breathe, eat and have sex. They give gifts, communicate, learn, remember and record the important events of their lives. With relatives and non-kin alike they cooperate, forming neighborhood watch committees -- to name one example -- with rapid response networks to alert others to a threatening intruder. They manage their resources in bank accounts, using past market trends to predict future needs. They mine and farm the land, and sometimes move their families across great distances for better opportunities. Some of this might take centuries, but for a creature with a life span of hundreds or thousands of years, time must surely have a different feel about it.

"And for all that, trees are things to us, good for tables, floors and ceiling beams: As much as we might admire them, we���re still happy to walk on their hearts. It may register as a shock, then, that trees have lives so much like our own. All the behaviors described above have been studied and documented by scientists who carefully avoid the word 'behavior' and other anthropomorphic language, lest they be accused of having emotional attachments to their subjects.

"The novelist suffers no such injunction, but most of them don���t know beans about botany. Richard Powers is the exception, and his monumental novel The Overstory accomplishes what few living writers from either camp, art or science, could attempt. Using the tools of story, he pulls readers heart-first into a perspective so much longer-lived and more subtly developed than the human purview that we gain glimpses of a vast, primordial sensibility, while watching our own kind get whittled down to size."

In an excellent interview with Richard Powers, Bradford Morrow notes:

"Some of our greatest novelists, from Thomas Hardy to Willa Cather and beyond, have so deeply invested their natural landscapes with the power of personality that nature becomes an active, even interactive, character in their work. Certainly, the trees in your novel similarly achieve an undeniable kind of selfhood, a soulful, communicative, and vital presence. They are families. Some of them are individuals with complicated lives....So, yes, Hardy, Cather, even J. R. R. Tolkien and others, have their ways of approaching nature as a character.

"What," he asks Powers, "is your trajectory here, philosophically, aesthetically, along other avenues, of making this come to life for you?"

"The choice to give these trees central roles in the plot and the cast of the novel," Powers answers, "is both elemental and elementary. At the core of the book (in the heartwood, if you will) is a rejection of human exceptionalism -- the idea that we are the only things on earth with agency, purpose, memory, flexible response to change, or community. Research has shown in countless marvelous ways that trees have all of these. Tree consciousness -- which we���ll need to recover in order to come back home to this planet and stop treating it like a bus station bathroom -- means understanding that trees, both singly and collectively, are central characters in our own stories.

"Related to this insight is the research of Patricia Westerford into the intensely collective nature of trees. Just as in the standard novel of psychological revelation that often plays social and group will against the individual, so, Westerford discovers, there is always a society of trees, sustaining and regulating the lives of its single stems:

'It will take years for the picture to emerge. There will be findings, unbelievable truths confirmed by a spreading worldwide web of researchers in Canada, Europe, Asia, all happily swapping data through faster and better channels. Her trees are far more social than even Patricia suspected. There are no individuals. There aren���t even separate species. Everything in the forest is the forest. Competition is not separable from endless flavors of cooperation. Trees fight no more than do the leaves on a single tree. It seems most of nature isn���t red in tooth and claw, after all. For one, those species at the base of the living pyramid have neither teeth nor talons. But if trees share their storehouses, then every drop of red must float on a sea of green.'

"Tolkien, by the way, was indeed an inspiration in some of this. His Ents must surely be among his most spectacular creations. Slow to anger, slow to act. But once they get going, you want them on your side."

"To live on this primarily nonhuman planet," says Powers later in the interview, "we must change how we think of nonhumans. They are not here merely to serve as our resources. They are intelligent agents, deserving of legal standing, creatures that want something from each other and from us. They, much more than we, have created this place. We are not their masters; our dependence on them should make us more like their resourceful servants. They are gifts, and all of us know how sparingly and reverently a gift is best used. As a friend puts it: How little we would need if we knew how much we have.

"The salvation of humanity -- for it���s us, not the world, who need to be saved -- and our continued lease on this planet depend on our development of tree consciousness. We are here by the grace of trees and forests. They make our atmosphere, clean our water, and sustain the cycles of life that permit us. Just begin to see them. See them up close and personal. See them from far away across great distances. Notice all the million complex beautiful behaviors and forms that have always slipped right past you. Simply see, and the rest will begin to follow. Every other act of preservation depends on that first step.

"For writers: ask yourself how many invisible nonhuman actors and agents are required to enable your tale of individual self-realization or domestic drama, then make those hidden sponsors visible. For readers: let the beauty of whatever book you���ve just read teach you to read the world beyond what we human beings call the real world. And for all of us, there is always Thoreau: 'Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, resign yourself to the influence of the earth.' "

Please don't miss this remarkable novel, which demonstrates one of the ways that artists today can use the tools of our various crafts -- language, paint, music, etc. -- to speak for the more-than-human world.

Words: The passages quoted above are from "The Heroes of This Novel are Centuries Old and 300 Feet Tall" by Barbara Kingsolver (The New York Times Book Review, April 9, 2018) and "Richard Powers: An Interview" by Bradford Morrow (Conjunctions: 70, Spring 2018). The poem in the picture captions is from Everything is Waiting for You by David Whyte (Many Rivers Press, 2003). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Visiting with the tree elders in the oak and beech woods on our hill, and the remarkable root systems of fallen giants.

June 7, 2019

Myth & Moor update

I'll be away for a long weekend as of mid-day today, then back in the studio again on Wednesday, 12 June. I will do my best to catch up on comments, email, and messenges next week, with apologies to those who have been waiting. (As my Pennsylvania Dutch grandmother used to say: "The faster I run, the behinder I get.")

Have a gently magical weekend...or a wildly magical one, whichever you prefer.

Art by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953).

June 6, 2019

The philosophy of compassion

The mystical Celtic Christian tradition -- which has come down to us through the writings of the peregrini, among others -- informs the work of Irish poet, philosopher, and theological scholar John O'Donohue (1956-2008), often quoted here on Myth & Moor. In his writings, the Celtic Chrisitian and pre-Christian traditions are closely aligned, both rooted in the natural world.

"Celtic thought contributes magnificently to a philosophy of compassion," he noted in an interview, "deriving from its sense that everything belongs in one diverse, living unity. On an ontological level, the exercise of compassion is the transfiguration of dualism: the separation of matter and spirit, masculine and feminine, body and soul, human and divine, person and animal, and person and element. The beauty of the Celtic tradition was that it managed to think and articulate all of these presences together in a profound, intimate unity. So, if compassion is a praxis which tries to bring that unity into explicit activity and presentation, then Celtic philosophy of unity contributes strongly to compassion.

"Celtic thought contributes magnificently to a philosophy of compassion," he noted in an interview, "deriving from its sense that everything belongs in one diverse, living unity. On an ontological level, the exercise of compassion is the transfiguration of dualism: the separation of matter and spirit, masculine and feminine, body and soul, human and divine, person and animal, and person and element. The beauty of the Celtic tradition was that it managed to think and articulate all of these presences together in a profound, intimate unity. So, if compassion is a praxis which tries to bring that unity into explicit activity and presentation, then Celtic philosophy of unity contributes strongly to compassion.

"The Celtic sense of no separating border between nature and humans allows us to have compassion with animals and with places in nature. For the Celts, nature wasn't a huge expanse of endless matter. Nature was an incredibly elemental and passionately individual presence, and that is why many gods and spirits are actually tied into very explicit places, and to the memory and history and narrative of the places.

"The predominant silence in which the animal world lives is very touching," O'Donohue continued. "As children on a farm, we were taught to respect animals. We were told that the dumb animals are blessed. They cannot say what they are feeling and we should have great compassion for them. They were tended to and looked after and people became upset if something happened to them. There was a great sense of solidarity between us and our older brothers and sisters, the animals.

"One of the tragedies in Western religion is the way that we have been so elitist in reserving the spiritual exclusively for the human. That is an awful, barbaric crime. When you subtract the notion of self from a presence, you objectify it and then that presence can be used and abused. It is a sin and blasphemy to say that animals have no spirits and souls. One of the cornerstones of contemplative life is going below the surface of the external and the negativity. The contemplative attends to the roots of wrong and violence. Because the animals live essentially what I call the contemplative life, maybe the most sacred prayer of the world actually happens within animal consciousness. Secondly, sometimes when you look into an animal's eyes, you see incredible pain. I think there are levels of suffering for which humans are not refined enough, and maybe our older, ancient brothers and sisters, the animals, carry some of that for us.

"We recognize compassion in the willingness of someone to imagine himself into the life of another person. We recognize its presence in the withholding of huge negative moralistic judgment. We see compassion in the expression of mercy, in the refusal to label someone with a short-circuiting terminology that condemns her, even though her actions may be awkward. We see compassion in an openness to the greater mystery of the other person. The present situation, deed or misdeed is not the full story of the individual, there is a greater presence behind the deed or the person than society usually acknowledges. Above all, we see the presence of compassion as the vulnerability to be disturbed about awful things that are going on.

"One of the most vulnerable living forms in creation is human. Around the human body, where we live, there is emptiness. There is no big protective frame, so anything can come at you from outside at any time. At this moment, there are people in a doctor's office getting news that will change their lives forever. They will remember this day as the day their life broke in two. There are people having accidents that they never foresaw. There are safe, complacent people whose lives are managed under the dead manacle of control falling off a cliff into love and into the excitement and danger of a new relationship. In life, anything can come along the pathway to the house of your soul, the house of your body, to transfigure you. We're vulnerable externally to destiny, but we're also vulnerable internally, within ourselves. Things can come awake within your mind and heart that cause you immense days and nights of pain, a sense of being lost, of having no meaning, no worth; a kind of acidic negativity can knock down everything that you achieve in yourself, giving your world a sense of being damaged.

"Another way to approach this is to look at the huge difference between sincerity and authenticity. Sincerity, while it's lovely, is necessary but insufficient, because you can be sincere with just one zone of your heart awakened. When many zones of the heart are awakened and harmonized we can speak of authenticity, which is a broader and more complex notion. It takes great courage and grace to feel the call to awaken, and it takes greater courage and more grace still to actually submit to the call, to risk yourself into these interior spaces where there is very often little protection.

"It takes a great person to creatively inhabit her own mind and not turn her mind into a destructive force that can ransack her life. You need compassion for yourself, particularly in American society, because many people in America identify themselves through the models and modules of psychology that inevitably categorize them as a syndrome. Lovely people feel that their real identity is working on themselves, and some work on themselves with such harshness. Like a demented gardener who won't let the soil settle for anything to grow, they keep raking, tearing away the nurturing clay from their own heart, then they're surprised that they feel so empty and vacant.

"Self-compassion is paramount. When you are compassionate with yourself, you trust in your soul, which you let guide your life. Your soul knows the geography of your destiny better than you do."

The text above first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2015, but is revisited today with new pictures of the Dartmoor pony foals on our village Commons. John O'Donohue's words are quoted from an interview with author by Mary NurrieStearns, which you can read in full here. The poem in the picture captions comes from Denise Levertov's Poems 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights reserved by Ms NurrieStearns and the O'Donohue and Levertov estates.

Related posts: Call-it-what-you-will (on the soul) and more John O'Donohue in Dark Beauty.

June 5, 2019

Something to do with love

From an interview with David Foster Wallace in The Contemporary Literature Review:

"I've gotten convinced that there's something kind of timelessly vital and sacred about good writing. This thing doesn't have that much to do with talent, even glittering talent. Talent's just an instrument. It's like having a pen that works instead of one that doesn't. I'm not saying I'm able to work consistently out of the premise, but it seems like the big distinction between good art and so-so art lies somewhere in the art's heart's purpose, the agenda of the consciousness behind the text. It's got something to do with love. With having the discipline to talk out of the part of yourself that can love instead of the part that just wants to be loved....

"One of the things really great fiction writers do -- from Carver to Chekhov to Flannery O'Connor, or like the Tolstoy of 'The Death of Ivan Ilych' or the Pynchon of Gravity's Rainbow -- is 'give' the reader something. The reader walks away from the real art heavier than she came into it. Fuller. All the attention and engagement and work you need to get from the reader can't be for your benefit; it's got to be for hers. What's poisonous about the cultural environment today is that it makes this so scary to try to carry out."

Which is precisely why this kind of work is necessary. Especially here in the field of fantasy literature and mythic arts.

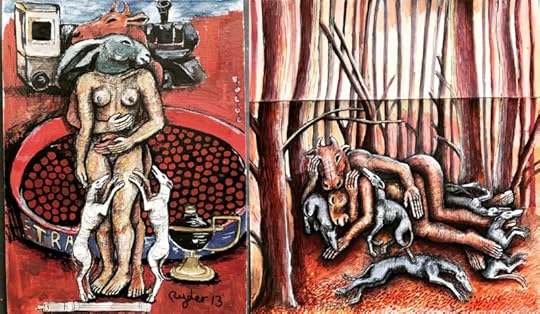

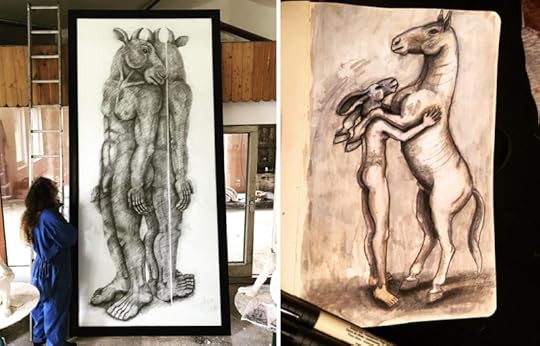

The marvelous sculptures and drawings today are by English artist Sophie Ryder. Born in London in 1963, she was raised in England and the south of France, studied at the Royal Academy of Arts, and now lives and works in an enchanted hand-crafted farmhouse in the Cotswolds. Ryder's world "is one of mystical creatures, animals and hybrid beings made from sawdust, wet plaster, old machine parts and toys, weld joins and angle grinders, wire 'pancakes,' torn scraps of paper, charcoal sticks and acid baths."

Her hare figures, she says, "started off as upright versions of the hare in full animal form, and now they have developed into half human and half hare. I needed a figure to go with the minotaur -- a human female figure with an animal head. The hare head seemed to work perfectly, the ears simulating a mane of hair. She feels right to me, as if she had always existed in myth and legend, like the minotaur."

Ryder's dogs (whippets crossed with Italian greyhounds) also appear frequently in her work. "I have been breeding these dogs since 1999," she explains, "and since then have achieved the most perfect companions and models -- Elsie, Pedro, Luigi and Storm. Now we are a pack and they are with me twenty-four hours a day. We run, work and sleep together -- although they do have their own beds now! Living cheek-by-jowl with these dogs means that their form is somehow sitting just under my own skin. I can draw or sculpt them entirely from memory. They are my full-time companions so I am never lonely. The relationship between the Lady Hare and the dog is very close, just as is my bond with my own family of dogs."

To see more of Ryder's art, please visit her website, Instragram page, or seek out Jonathan Bennington's book Sophie Ryder (Lund Humphries, 2001). There's an interview with the artist here, lovely pictures of her farmhouse here, and more information on the folklore of hares and rabbits here.

The quote above is from "A Conversation with David Foster Wallace" by Larry McCaffery (The Review of Contemporary Fiction, 1993). All rights to the art, video, and text above reserved by the artist, filmmaker, and the author's estate.

Related posts: Doing it for love and Not silence but many voices.

The language of the animate earth

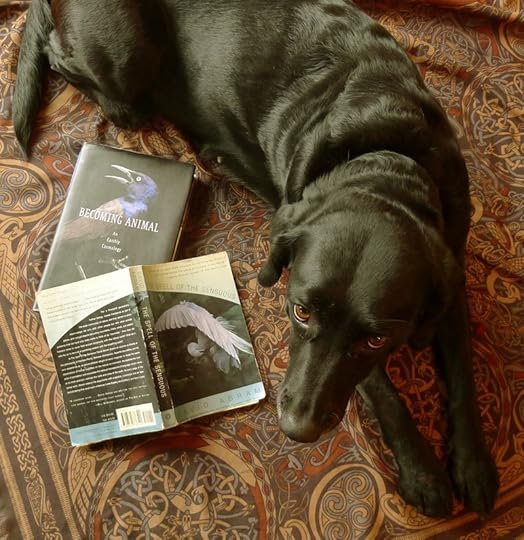

From The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception & Language in a More-Than-Human World by David Abram:

"The sense of being immersed in a sentient world is preserved in the oral stories of indigenous peoples --in the belief that sensible phenomena are all alive and aware, in the assumption that all things have the capacity for speech. Language, for oral peoples, is not a human invention but a gift of the land itself.

"I do not deny that human language has its uniqueness, that from a certain perspective human discourse has little in common with the sounds and signals of other animals, or with the rippling speech of the river. I wish simply to remember that this was not the perspective held by those who first acquired, for us, the gift of speech.

"Human language evolved in a thoroughly animistic context; it necessarily functioned, for many millenia, not only as a means of communication between humans, but as a way of propitiating, praising, and appeasing the expressive powers of the surrounding terrain. Human language, that is, arose not only as a means of attunement between persons, but also between ourselves and the animate landscape.

"The belief that meaningful speech is a purely human property was entirely alien to those oral communities that first evolves our various ways of speaking, and by holding to such a belief today we may well be inhibiting the spontaneous activity of language. By denying that birds and other animals have their own styles of speech, by insisting that the river has no real voice and that the ground itself is mute, we stifle our direct experience. We cut ourselves off from the deep meanings of many of our words, severing our language from that which supports and sustains it.

"We wonder then why we are so often unable to communicate even among ourselves."

The pictures today are of our local Dartmoor pony herd and their newborn foals. (The last time I posted pony photos here, the mares were still pregnant.) These semi-wild ponies travel between the hills of Chagford (full of tender green grass for grazing) and the open moor; the sheltered slope of our village Commons is where they come to give birth each year. It's been a good season for the ponies: we've counted ten new foals in all. I watch the movement of the herd across the valley from the windows of my hillside studio, and the hound and I make daily visits to the Commons to check on the foals' progress. They are exquisite.

Words: The passage above is from The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram (Vintage, 1996). The poem in the picture captions, "A Blessing" by James Wright, is from Above the River: The Complete Poems & Selected Prose (Wesleyan University Press, 1990). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Photographs of the new crop of foals on the village Commons, taken shortly after they were born, earlier this spring. More recent photos to follow.

Related posts: Living in a storied world, Animalness, Relationship & reciprocity, and The speech of animals.

June 4, 2019

The logos of the land: living, working, and writing fantasy while rooted in place

David Abram's The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception & Language in a More-Than-Human World has been a touch-stone text ever since I first stumbled upon it in a Tucson bookshop in the 1990s (when I was writing my desert novel The Wood Wife) -- and it has never ceased to be relevant during the many times I've re-read it. The questions it raises concerning our fraying connection to the natural world -- and the role that Story plays in strengthening or weaking that connection -- are questions that echo in my creative work, albeit in the metaphoric, poetic, slant-wise language of myth, folklore and fantasy.

In a latter chapter of the book, David writes:

"The deer on this island [in the Pacific North-West] have recently molted, forsaking their summer fur for a thicker winter coat. I watch them in the old orchard at dusk. No longer the warm brown color of sunlight on soil, their fur is now grey against the shadowed trunks and the all-grey sky. These quiet beings seem entirely part of this breathing terrain, their very texture and color shifting with the local seasons.

"Human persons, too, are shaped by the places they inhabit, both individually and collectively. Our bodily rhythms, our moods, cycles of creativity and stillness, and even our thoughts are readily engaged and influenced by shifting patterns in the land. Yet our organic attunement to the local earth is thwarted by our ever-increasing intercourse with our own signs. Transfixed by our technologies, we short-circuit the sensorial reciprocity between our breathing bodies and the bodily terrain. Human awareness folds in upon itself, and the senses -- once the crucial site of our engagement with the wild and animate earth -- become mere adjuncts of an isolated and abstract mind bent on overcoming an organic reality that now seems disturbingly aloof and arbitrary.

"The alphabetized intellect stakes its claim to the earth by staking it down, extends its dominion by drawing a grid of straight lines and right angles across the body of a continent -- across North America, across Africa, across Australia -- defining states and provinces, counties and countries with scant regard for the oral peoples that already live there, according to a calculative logic utterly oblivious to the life of the land.

"If I say I live in the 'United States' or in 'Canada,' in 'British Columbia' or in 'Mexico,' I situate myself within a purely human set of coordinates. I say very little or nothing about the earthly place that I inhabit, but simply establish my temporary location within a shifting matrix of political, economic, and civilizational forces struggling to maintain themselves, today, largely at the expense of the animate earth. The great danger is that I, and many other good persons, may come to believe that our breathing bodies really inhabit these abstractions, and that we will lend our lives to consolidating, defending, or bewailing the fate of these ephemeral entities rather than to nurturing and defending the actual places that physically sustain us."

How precient those words seem today, when the the borderlines between countries and cultures have become hotly contested, shaking our systems of governance to their foundations -- all while climate crisis rolls on, and cannnot be stopped at the passport gate. Fantasy, too, is a literature full of borders crossed, and borders that may not be crossed. In thinking about the boundaries and borders drawn on maps of imaginary lands, I wonder how we might re-envision them...and thereby give language to other ways of living in the physical, tactile world we share with our four-footed, scaled, and winged neighbours.

The land has its own articulations, David writes,

"its own contours and rhythms that must be acknowledged if it is to breathe and flourish. Such patterns, for instance, are those traced by rivers as they wind their way to the coast, or by a mountain range that rises like a backbone from the plains, its ridges halting the passage of clouds that gather and release their rains on one side of the range, leaving the other slope dry and desertlike. Another such contour is the boundary between two very different kinds of bedrock caused by some cataclysmic event in the story of a continent, or between two different soils, each of which invites a different population of plants and trees to take root. Diverse groups of animals arrange themselves within such subtle boundaries, limiting their movements to the terrain that affords them their needed foods and the necessary shelter from predators. Other, more migratary species follow such patterns as they move with the seasons, articulating routes and regions readily obscured by the current human overlay of nations, states, and their various subdivisions. Only when we slip beneath the exclusively human logic continually imposed on the earth do we catch sight of this other, older logic at work in the world. Only as we come close to our senses, and begin to trust, once again, the nuanced intelligence of our sensing bodies, to we begin to notice and respond to the subtle logos of the land.

"There in an intimate reciprocity to the senses; as we touch the bark of a tree, we feel the tree touching us; as we lend our ears to the local sounds, and ally our noses to the seasonal scents, the terrain gradually tunes in with us in turn. The senses, that is, are the primary way that the earth has of informing our thoughts and of guiding our actions. Huge centralized programs, global initiatives, and other 'top down' solutions will never suffice to restore and protect the health of the animate earth. For it is only at the scale of our direct, sensory interactions with the land around us that we can appropriately notice and respond to the immediate needs of the living world.

"Yet at the scale of our sensing bodies the earth is astonishly, irreducibly diverse. It discloses itself to our senses not as a uniform planet inviting global principles and generalizations, but as this forested realm embraced by water, or a windswept prairie, or a desert silence. We can know the needs of any particular region only by participating in its specificity -- by becoming familiar with its cycles and styles, wake an attentive to its other inhabitants."

As a fantasy writer/editor long past youth, with 30+ years of experience in the field, I still feel like the merest apprentice to the ancient art of crafting stories. I am also apprenticed to the local terrain: the patchwork of moorland hills where I live. I walk and re-walk the same network of paths through woods and meadows and riverside fields, learning the quiet green language spoken here, day after day, season after season. These things are connected: the writing, the walking. They are part of the same apprenticeship. It is slow, patient, weather-wise work to discover the stories the land wants to give you. It is slow, patient, weather-wise work to craft the words in which they are passed on.

I look to the words of other writers for guidance: fantasists, naturalists, folklorists, poets who point the way down the wild, crooked trails that lead to a well-storied world. The Spell of the Sensuous is one such guide. There are other authors and other texts that have taught and inspired me over the years, but this is one I keep coming back to...and every time it has new things to tell me.

Words: The passage above is from The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram (Vintage, 1996). The poem in the picture captions, "Looking, Walking, Being" by Denise Levertov, is from Poems: 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The bluebell fields on the slopes and top of our hill at the end of May.

Related posts: Kith and Kin, Twilight Tales, Crossing Borders, and The enclosure of the Commons: borders that keep us out.

The logos of the land

David Abram's The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception & Language in a More-Than-Human World has been a touch-stone text ever since I first stumbled upon it in a Tucson bookshop in the 1990s (when I was writing my desert novel The Wood Wife) -- and it has never ceased to be relevant during the many times I've re-read it. The questions it raises concerning our fraying connection to the natural world -- and the role that Story plays in strengthening or weaking that connection -- are questions that echo in my creative work, albeit in the metaphoric, poetic, slant-wise language of myth, folklore and fantasy.

In a latter chapter of the book, David writes:

"The deer on this island [in the Pacific North-West] have recently molted, forsaking their summer fur for a thicker winter coat. I watch them in the old orchard at dusk. No longer the warm brown color of sunlight on soil, their fur is now grey against the shadowed trunks and the all-grey sky. These quiet beings seem entirely part of this breathing terrain, their very texture and color shifting with the local seasons.

"Human persons, too, are shaped by the places they inhabit, both individually and collectively. Our bodily rhythms, our moods, cycles of creativity and stillness, and even our thoughts are readily engaged and influenced by shifting patterns in the land. Yet our organic attunement to the local earth is thwarted by our ever-increasing intercourse with our own signs. Transfixed by our technologies, we short-circuit the sensorial reciprocity between our breathing bodies and the bodily terrain. Human awareness folds in upon itself, and the senses -- once the crucial site of our engagement with the wild and animate earth -- become mere adjuncts of an isolated and abstract mind bent on overcoming an organic reality that now seems disturbingly aloof and arbitrary.

"The alphabetized intellect stakes its claim to the earth by staking it down, extends its dominion by drawing a grid of straight lines and right angles across the body of a continent -- across North America, across Africa, across Australia -- defining states and provinces, counties and countries with scant regard for the oral peoples that already live there, according to a calculative logic utterly oblivious to the life of the land.

"If I say I live in the 'United States' or in 'Canada,' in 'British Columbia' or in 'Mexico,' I situate myself within a purely human set of coordinates. I say very little or nothing about the earthly place that I inhabit, but simply establish my temporary location within a shifting matrix of political, economic, and civilizational forces struggling to maintain themselves, today, largely at the expense of the animate earth. The great danger is that I, and many other good persons, may come to believe that our breathing bodies really inhabit these abstractions, and that we will lend our lives to consolidating, defending, or bewailing the fate of these ephemeral entities rather than to nurturing and defending the actual places that physically sustain us."

How precient those words seem today, when the the borderlines between countries and cultures have become hotly contested, shaking our systems of governance to their foundations -- all while climate crisis rolls on, and cannnot be stopped at the passport gate. Fantasy, too, is a literature full of borders crossed, and borders that may not be crossed. In thinking about the boundaries and borders drawn on maps of imaginary lands, I wonder how we might re-envision them...and thereby give language to other ways of living in the physical, tactile world we share with our four-footed, scaled, and winged neighbours.

The land has its own articulations, David writes,

"its own contours and rhythms that must be acknowledged if it is to breathe and flourish. Such patterns, for instance, are those traced by rivers as they wind their way to the coast, or by a mountain range that rises like a backbone from the plains, its ridges halting the passage of clouds that gather and release their rains on one side of the range, leaving the other slope dry and desertlike. Another such contour is the boundary between two very different kinds of bedrock caused by some cataclysmic event in the story of a continent, or between two different soils, each of which invites a different population of plants and trees to take root. Diverse groups of animals arrange themselves within such subtle boundaries, limiting their movements to the terrain that affords them their needed foods and the necessary shelter from predators. Other, more migratary species follow such patterns as they move with the seasons, articulating routes and regions readily obscured by the current human overlay of nations, states, and their various subdivisions. Only when we slip beneath the exclusively human logic continually imposed on the earth do we catch sight of this other, older logic at work in the world. Only as we come close to our senses, and begin to trust, once again, the nuanced intelligence of our sensing bodies, to we begin to notice and respond to the subtle logos of the land.

"There in an intimate reciprocity to the senses; as we touch the bark of a tree, we feel the tree touching us; as we lend our ears to the local sounds, and ally our noses to the seasonal scents, the terrain gradually tunes in with us in turn. The senses, that is, are the primary way that the earth has of informing our thoughts and of guiding our actions. Huge centralized programs, global initiatives, and other 'top down' solutions will never suffice to restore and protect the health of the animate earth. For it is only at the scale of our direct, sensory interactions with the land around us that we can appropriately notice and respond to the immediate needs of the living world.

"Yet at the scale of our sensing bodies the earth is astonishly, irreducibly diverse. It discloses itself to our senses not as a uniform planet inviting global principles and generalizations, but as this forested realm embraced by water, or a windswept prairie, or a desert silence. We can know the needs of any particular region only by participating in its specificity -- by becoming familiar with its cycles and styles, wake an attentive to its other inhabitants."

As a fantasy writer/editor long past youth, with 30+ years of experience in the field, I still feel like the merest apprentice to the ancient art of crafting stories. I am also apprenticed to the local terrain: the patchwork of moorland hills where I live. I walk and re-walk the same network of paths through woods and meadows and riverside fields, learning the quiet green language spoken here, day after day, season after season. These things are connected: the writing, the walking. They are part of the same apprenticeship. It is slow, patient, weather-wise work to discover the stories the land wants to give you. It is slow, patient, weather-wise work to craft the words in which they are passed on.

I look to the words of other writers for guidance: fantasists, naturalists, folklorists, poets who point the way down the wild, crooked trails that lead to a well-storied world. The Spell of the Sensuous is one such guide. There are other authors and other texts that have taught and inspired me over the years, but this is one I keep coming back to...and every time it has new things to tell me.

Words: The passage above is from The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram (Vintage, 1996). The poem in the picture captions, "Looking, Walking, Being" by Denise Levertov, is from Poems: 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The bluebell fields on the slopes and top of our hill at the end of May.

Related posts: Kith and Kin, Twilight Tales, Crossing Borders, and The enclosure of the Commons: borders that keep us out.

June 3, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

June 1st marks the beginning of 30 Days Wild, an annual event sponsored by the UK's Wildlife Trusts. The idea is to do something out in nature each day no matter where you live -- country, city, town, or suburb. It's a good way of remembering to stay connected to the beautiful natural world -- especially now, when climate crisis is the most pressing issue of our time.

June 1st marks the beginning of 30 Days Wild, an annual event sponsored by the UK's Wildlife Trusts. The idea is to do something out in nature each day no matter where you live -- country, city, town, or suburb. It's a good way of remembering to stay connected to the beautiful natural world -- especially now, when climate crisis is the most pressing issue of our time.

Today, in honor of 30 Days Wild, here is a collection of "wild songs" about the growing green world, woodlands dark and bright, coastal winds and forest magic....

Above: "Trees Hug Bees" by Jeanes -- a music collective founded by Russell Jeanes (a graphic designer, filmmaker and poet from Yorkshire) to create Sleeping Leaves, a "pastoral folk" EP containing songs, poems, and sounds of the natural world put together in a collective fashion.The vocalist on this tract is L��a Decan.

Belove: "The Arboretum" by singer/songwriter Bill Jones, based in north-east England. The song appears on her new album, A Wonderful Fairytale (2019).

Above: "Sisters Three" by singer/songwriter Ange Hardy, from Somerset. The song appears on her sixth studio album, Bring Back Home (2017).

Below: "A��� phiuthrag ���sa phiuthar (O sister, beloved sister)" performed by Julie Fowlis, from North Uist in the Outer Hebrides. It tells the story of a girl lured away in the woods by the s��thichean (the fairy-people), and her sister's long search to bring her home again. The song appears on Fowlis' latest album, Alterus (2018). The animation is by Eleonore Dambre and Dima Nowarah.

Above: "Woodcat" by Tunng, a "folktronica" band founded by Sam Genders and Mike Lindsay, based in London. This wonderfully odd little song (rooted in the folklore of shape-shifting hares) appears on the group's latest album, Songs You Make At Night (2018).

Below: "Old Pine" by singer/songwriter Ben Howard, who grew up on the other side of Dartmoor. The song, celebrating the beauty of our West Country coastline, is from Ben's first album, Every Kingdom (2012).

Pictures: An old beech tree twined with ivy, photographed in spring and summer; wild strawberries and piskie flowers in the woods; and a vintage drawing of a bumblebee (artist unknown). The hare painting is "The Spirit Within" by Karen Davis; all rights reserved by the artist.

June 1, 2019

The folklore of nettles

As we've been discussing the folklore of wild flowers and herbs, I thought I'd add this relevant post from the archives to finish off the week....

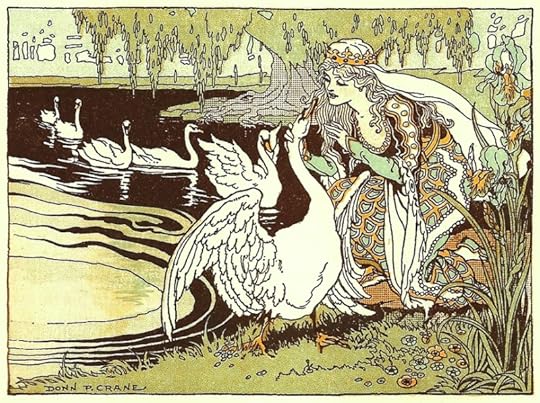

In the fairy tale of "The Wild Swans" by Hans Christian Andersen, the heroine's brothers have been turned into swans by their evil stepmother. A kindly fairy instructs her to gather nettles in a  graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

This was one of my favorite stories as a child, for I too had brothers in harm's way, and I too was a silent sister who worked as best I could to keep them safe, and sometimes succeded, and sometimes failed, as the plot of our lives unfolded. The story confirmed that courage can be as painful as knitting coats from nettles, but that goodness can still win out in the end. Spells can broken, and gentle, loving persistence can be the strongest magic of them all.

I grew up with the story, but not with Urtica dioica: "common nettles" or "stinging nettles." I imagined them as dark, thorny, and witchy-looking -- and although they're actually green and ordinary, growing thickly in fields and hedges here in Devon, nettles emerge nonetheless from the loam of old stories and glow with a fairy glamour. It is a plant that heralds the return of spring, a tonic of vitamins and minerals; and also a plant redolent of swans and spells, of love and loss and loyalty, of ancient powers skillfully knotted into the most traditional of women's arts: carding, spinning, knitting, and sewing.

According to the Anglo-Saxon "Nine Herbs Charm," recorded in the 10th century, sti��e (nettles) were used as a protection against "elf-shot" (mysterious pains in humans or livestock caused by the arrows of the elvin folk) and"flying venom" (believed at the time to be one of the four primary causes of illness). In Norse myth, nettles are associated with Thor, the god of Thunder; and with Loki, the trickster god, whose magical fishing net is made from them. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are fairy dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against fairy mischief, black magic, and other forms of sorcery.

Nettles once rivaled flax and hemp (and later, cotton) as a staple fiber for thread and yarn, used to make everything from heavy sailcloth to fine table linen up to the 17th/18th centuries. Other fibers proved more economical as the making of cloth became more mechanized, but in some areas (such as the highlands of Scotland) nettle cloth is still made to this day. "In Scotland, I have eaten nettles," said the 18th century poet Thomas Campbell, "I have slept in nettle sheets, and I have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The young and tender nettle is an excellent potherb. The stalks of the old nettle are as good as flax for making cloth. I have heard my mother say that she thought nettle cloth more durable than any other linen."

"Nettles have numerous virtues," writes Margaret Baker in Discovering the Folklore of Plants. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin; the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness.

"Mixing medicine and magic, a healer could cure fever by pulling up a nettle by its roots while speaking the patient's name and those of his parents. Roman soldiers in damp Britain found that rheumatic joints responded to a beating with nettles. Tyroleans threw nettles on the fire to avert thunderstorms, and gathered nettle before sunrise to protect their cattle from evil spirits."

The medicinal value of nettles is confirmed by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal in their useful book Hedgerow Medicine:

"Nettle was the Anglo-Saxon sacred herb wergula, and in medieval times nettle beer was drunk for rheumatism. Nettle's high vitamin C content made it a valuable spring tonic for our ancestors after a winter of living on grain and salted meat, with hardly any green vegetables. Nettle soup and porridge were popular spring tonic purifiers, but a pasta or pesto from the leaves is a worthily nutritious modern alternative. Nettle soup is described by one modern writer as 'Springtime herbalism at one of its finest moments.' This soup is the Scottish kail. Tibetans believe that their sage and poet Milarepa (AD 1052-1135) lived solely on nettle soup for many years until he himself turned green: a literal green man.

"Nettles enhance natural immunity, helping protect us from infections. Nettle tea drunk often at the start of a feverish illness is beneficial. Nettles have long been considered a blood tonic and are a wonderful treatment for anaemia, as they are high in both iron and chlorophyll. The iron in nettles is very easily absorbed and assimilated. What cooks will tell you is that two minutes of boiling nettle leaves will neutralize both the silica 'syringes' of the stinging cells and the histamine or formic acid-like solution that is so painful."

Here's our family recipe for Bumblehill Nettle Soup, which is easy to make and delicious:

First, pick your nettles by pinching off the fresh leaves at the tip of the plant, leaving the plant itself intact. It's best to do this in the spring when the plants are young and the vitamin content at its highest, before the flowers appear. Rinse your nettle tips in cold water, and cut off any woody bits or thick stems. You need to wear gloves while you handle them, but once the nettles are cooked you can safely eat them without any stinging.

Melt some butter in the bottom of the soup pot, add a chopped onion or two, and cook slowly until softened.

Add a litre or so of vegetable or chicken stock, with salt, pepper, and any herbs you fancy.

Add 2 large potatoes (chopped), a large carrot (chopped), and simmer until almost soft. If you like your soup thick, use more potatoes.

Throw in several large handfuls of fresh nettle leaves, and simmer gently for another 10 minutes.

Add some cream (to taste), and a pinch of nutmeg. Pur��e with a blender, and serve. (If you happen to have some truffle oil in your pantry, a light sprinkling on the soup tastes terrific.) Use the left-over nettles for tea, sweetened with honey.

You can also throw young nettle leaves into pancake, crepe, scone, biscuit, and bread recipes -- just rinse them, chop them, and blanch them in boiling water (to get the sting out) first. Below, for example: savoury squares of nettle-and-herb flatbread with sea salt, and sweet nettle pancakes.

Nettles, folk tales around the world agree, have long been associated with women's domestic magic: with inner strength and fortitude, with healing and also self-healing, with protection and also self-protection, with the ability to "enrich the soil" wherever we have been planted. Nettle magic is steeped in dualities: both fierce and soft, painful and restorative, common as weeds and priceless as jewels. Potent. Tenacious. Humble and often overlooked. Resilient.

And pretty tasty too.

Pictures: The illustrations for "The Wild Swans" fairy tale are by Nadezhda Illarionova, Susan Jeffers, Mercer Mayer, Eleanor V. Abbott, Yvonne Gilbert, and Donn P. Crane. The Nettle Coat is by Alice Maher. Words: The quoted passages are from Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008) and Hedgerow Medicine by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal (Merlin Unwin Books, 2008). All rights reserved by the artists and authors. Related posts: Wildflower season, More folklore of the wild flowers, The folklore of food, and Swan's wing.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers