Terri Windling's Blog, page 62

April 10, 2019

Myth & Moor update

There will not be a Myth & Moor post today, as I'm hard at work on two super-tight deadlines. My apologies.

Instead, I recommend reading the latest interview with always-inspiring Terry Tempest Williams: "Putting the Language of the Earth on the Agenda." Or Anne Boyer's beautifully written essay, "What Cancer Takes Away" (which some of us can relate to all too well). Or have a look at Mariano Renter��a Garnica's video "Dance with the Devil," about the survival of an old folkloric form of dance in Mexico.

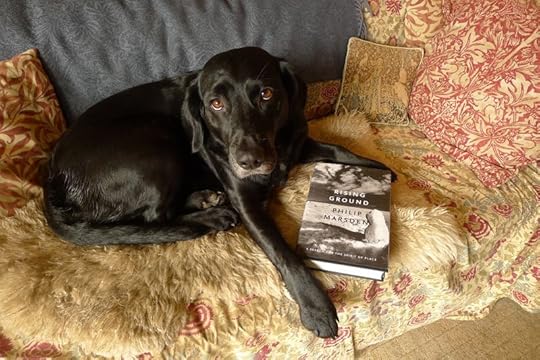

Tilly I wish you a good, creatively productive, and quietly enchanting day...or outrageously enchanting, if you prefer.

April 9, 2019

Rituals of Approach

In the previous post today, Susan Cooper touched lightly on the thorny subject of procrastination...and I'm going to go out on a limb here to suggest procrastination is not always bad.

The form of procrastination that Copper describes can, unless it gets out of hand, be a useful part of the working process, a circling of the water before one plunges in. To push the water metaphor a little further, some of us are divers and some of us inch into a cold pool of water bit by bit -- not because we don't intend to swim, but because that's how we're psychologically built to best handle transitions. The initial shock of a cold plunge invigorates some swimmers, but is uncomfortable, almost painful, to others; and we learn by trial and error which approach works best for us, physically and temperamentally.

For me, the slow circling of my writing desk in the morning isn't one of avoidance (though it can be, on a bad day, if I'm not careful), it's simply part of my transition from the everyday world into the cold, clear pool of my imagination. Here's how the work day starts for me, after an early walk up Nattadon Hill with Tilly:

I do a quick tidy of the studio (I like a calm, ordered environment), put music on the stereo (something without words: classical, medieval, music for the Celtic harp or Native American flute), settle Tilly on the sofa with her morning treat (a piece of carrot), pluck a book from the shelves and read a few pages (essays, folklore, poetry), pour a cup of coffee from my thermos (if I haven't already finished it off outdoors), write this blog (as a writing warm-up), turn my connection to the Internet off, and then finally get down to work: generally, like Susan Cooper, by reading over previous pages and notes from the day before, and trying my damnedest to resist editing those pages instead of pushing on into new material. All through this process, I must be wary of the other kind of procrastination, the kind that really is avoidance or distraction: getting overly absorbed in the reading, for example, or hooked by the lures of Internet. That's where discipline comes in: the commitment and professionalism required to keep my transition-into-work process on track.

I could, of course, simply come into the studio, sit myself down and get right to it -- but I've learned, over all these years, that this is just not the best method for me; I write better, and faster, if I honor the process of transition that suits my creative temperament. My family knows not to disturb me during this process -- even though, to the outside eye, I might not appear to be actually working yet. While I'm not such a fragile flower that I can't get back into my work if an interruption does occur, and of course life is unpredictable, as a general rule I try to sweep unnecessary obstacles from my working day by making my schedule and habits as conducive to the work as possible. Ideally, I want to be challenged by the writing itself, not by the journey it takes to get down to it.

I could, of course, simply come into the studio, sit myself down and get right to it -- but I've learned, over all these years, that this is just not the best method for me; I write better, and faster, if I honor the process of transition that suits my creative temperament. My family knows not to disturb me during this process -- even though, to the outside eye, I might not appear to be actually working yet. While I'm not such a fragile flower that I can't get back into my work if an interruption does occur, and of course life is unpredictable, as a general rule I try to sweep unnecessary obstacles from my working day by making my schedule and habits as conducive to the work as possible. Ideally, I want to be challenged by the writing itself, not by the journey it takes to get down to it.

I'm not advocating this working method for everyone, of course; I'm advocating that we all find out our own best way of working, and implement it to whatever extent our lives make possible. I'm an inch-into-the-water kind of girl; you might be a diver, or something else altogether. But take heart fellow-inchers: ours, too, is a perfectly valid approach, provided we are clear about the good and bad -- or perhaps, I should say "useful" and "not useful" -- forms of procrastination. For me, for example, reading a book or journal is useful because the quiet intimacy of this kind of reading serves me in my state of transition, easing me into the quiet Lake of Words I seek to enter -- whereas reading on the Internet, with its mass choir of voices and its speedy, amped-up rhythms, spins me away from my inner Lake of Words and off into other directions. The myriad attractions on-line are tempting -- oh, so tempting! -- but I've learned to limit my time here, especially in the morning during the "ritual of approach" into my writing day.

The useful notion of a "ritual of approach" is borrowed from the Irish poet/philosopher John O'Donohue, who discusses the mythic roots of the term in his wise book Beauty: The Invisible Embrace. "Many of the ancient cultures practiced careful rituals of approach," he notes. "An encounter of depth and spirit was preceded by careful preparation. When we approach with reverence, great things decide to approach us. Our real life comes to the surface and its light awakens the concealed beauty in things. When we walk on the earth with reverence, beauty will decide to trust us. The rushed heart and arrogant mind lack the gentleness and patience to enter that embrace."

This is not to imply that the "divers" among us are "rushed and arrogant"; if they are working well, then their rituals of approach are swift, rather than rushed, and they are blessed to have a creative rhythm in tune with our fast-moving times. Inchers often (not always) move at a slower pace, and while that can be at odds with our production-focused world, neither method is inherently "better" than the other. Divers and inchers, we seek the same goal: immersion into the Lake of Story, whose cold, sweet waters sustain us all.

But let's speak of the bad side of procrastination for a moment -- for the very same tasks that can be used to inch our way into our work (clearing the desk, clearing the decks, reading, blogging, etc.) can also be used to avoid our work, blocking the "ritual of approach" altogether; and it takes self-knowledge and rigorous self-honesty to know the difference.

If procrastination of the bad sort has become a problem for you...well, you're not alone. Many writers I've worked with over the years, including highly successful ones, have struggled with this; and some are struggling still. The most useful text I know on the subject is Hillary Rettig's very practical book The Seven Secrets of the Prolific: The Definitive Guide to Overcoming Procrastination, Perfectionism, and Writers' Block. Rettig takes readers step by step through the kinds of fears and toxic belief systems that usually lie at the heart of chronic procrastination, especially targeting the "perfectionist thinking" that seems to derail so many creative folks.

"Perfectionism," write Rettig, "is a toxic brew of anti-productive habits, attitudes and ideas. It is not the same as having high standards, and there is no such thing as 'good perfectionism.' "

These habits, as Rettig defines them, include: "Defining success narrowly and unrealistically; punishing oneself harshly for perceived failures. Grandiosity; or the deluded idea that things that are difficult for other people should be easy for you. Shortsightedness, as manifested in a 'now or never' or 'do or die' attitude. Over-identification with the work. Overemphasis on product (vs. process), and on external rewards."

"Grandiosity," says Rettig, "is a problem for writers because our media and culture are permeated with grandiose myths and misconceptions about writing, which writers who are under-mentored or isolated fall prey to. Red Smith���s famous bon mot about how, to write, you need only 'sit down at a typewriter and open a vein,' and Gene Fowler���s similarly sanguinary advice to 'sit staring at a blank sheet of paper until the drops of blood form on your forehead,' are nothing but macho grandiose posturing, as is William Faulkner���s overwrought encomium to monomaniacal selfishness, from his Paris Review interview:

'The writer���s only responsibility is to his art. He will be completely ruthless if he is a good one. He has a dream. It anguishes him so much that he can���t get rid of it. He has no pece until then. Everything goes by the board: honor, pride, decency, security, happiness, all, to get the book written. If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ���Ode on a Grecian Urn��� is worth any number of old ladies.'

"Many of the famous quotes about writing are grandiose," Rettig continues. "I���m not saying that all of these writers were posturing -- perhaps that���s how they truly perceived themselves and their creativity. What I do know is that, for most writers, a strategy based on pain and deprivation is not a route to productivity. In fact, it is more likely a route to a block. I actually find quotes about how awful writing and the writing life are to be not just perfectionist, but self-indulgent. No one���s forcing these writers to write, after all; and there are obviously far worse ways to spend one���s time, not to mention earn one���s living. All worthwhile endeavors require hard, and occasionally tedious, work; and, if anything, we writers have it easy, with unparalleled freedom to work where and how we wish -- in contrast to, say, potters who need a wheel and kiln, or Shakespearean actors who need a stage and ensemble. Non-perfectionist and non-grandiose writers recognize all this. Flaubert famously said 'Writing is a dog���s life, but the only life worth living,' and special kudos go to Jane Yolen for her book Take Joy: A Writer���s Guide to Loving the Craft, which begins with a celebration of the inherent joyfulness of writing. She also responds to Smith���s and Fowler���s sanguinary comments with the good-natured ridicule they deserve: 'By God, that���s a messy way of working.' "

I'll let Jane have the final words today, for she is certainly one of the most prolific writers I know, as well as a Master in the fine and worthy art of living a creative life. In this quote, she offers writing advice that is as practical and down-to-earth as it is wise:

"Exercise the writing muscle every day, even if it is only a letter, notes, a title list, a character sketch, a journal entry. Writers are like dancers, like athletes. Without that exercise, the muscles seize up."

Succinct and true. And now it's time for me to head on out into the Lake of Story myself....

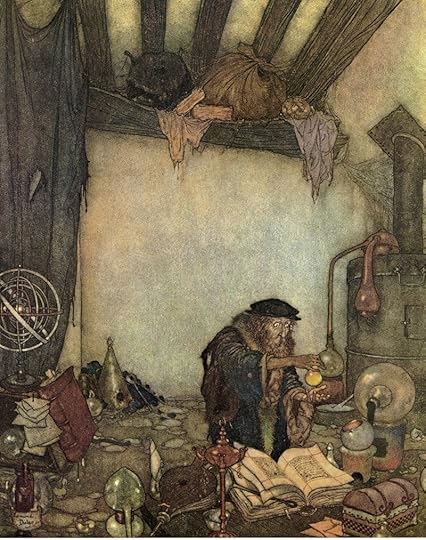

Pictures: Nattadon Hill at dawn. Illustration by Anne Anderson (1874-1930). Words: The passages above are quoted from The Seven Secrets of the Prolific by Hillary Rettig (Infinite Art, 2011); Beauty by John O'Donohue (Harper Perennial, 2005), and Take Joy by Jane Yolen (Writer's Digest Books, 2005). All rights reserved by the authors. A related post: On fear of judgement (and pernicious perfectionism).

Casting Spells

From "Worlds Apart," a talk by Susan Cooper at Oxford University (1992):

"Writing is one of the loneliest professions in the world because it has to be practiced in this very separate private world, in here. Not in the mind; in the imagination.  And I think it is possible that the writing of fantasy is the loneliest job of the lot, since you have to go further inside. You have to make so close a connection with the the subconscious that the unbiddable door will open and images fly out, like birds. It's not unlike writing poetry.

And I think it is possible that the writing of fantasy is the loneliest job of the lot, since you have to go further inside. You have to make so close a connection with the the subconscious that the unbiddable door will open and images fly out, like birds. It's not unlike writing poetry.

"It makes you superstitious. Most writers indulge in small private rituals to start themselves writing each day, and I find that when I'm working on a fantasy I'm even more ludicrously twitchy than usual. The very first half hour at the desk has nothing much to do with fantasy or even ritual: it's what J.B. Priestley used to call 'sharpening pencils' -- the business of doing absolutely everything you can think of to put off the moment of starting to work. You make another cup of coffee. You find a telephone call that must be made, a letter that must be answered. You do sharpen pencils. You look at the plant on the windowsill and decide that this is just the time to water it, or fertilize it, or prune it. Maybe it's even time to repot it. You hunt for the houseplant book, and look this up, and it says severely that this kind of plant enjoys being pot-bound and should never be repotted. So you turn to the bowl of paperclips on your desk, and find that safety pins and pennies and buttons have found their way in, so of course you really ought to sort out the paperclips....

"Finally guilt drives you to the manuscript -- and that's when the real ritual begins. (I should go back to the first person, because in this respect everyone is different.) I have to start by reading. I read a lot of what I've already written, maybe two or three chapters, even though I already know it all by heart. I read the notes I made to myself the day before when I stopped writing -- those were the end-of-the-day ritual, to help with the starting of the next. During this process I've picked up one of the toys scattered around my study, and my fingers are half-consciously playing with it: a smooth sea-washed pebble from an island beach, a chunky ceramic owl from Sweden, a little stone wombat from Australia. I read the last chapter again. I wander to a bookshelf and read a page of something vaguely related to my fantasy: Eliot's Quartets, maybe, or de la Mare's notes to Come Hither. I have even been known to blow bubbles, from a little tube that sits on my desk, and to sit staring at the colors that swirl over their brief surfaces. This the moment someone else usually choses to come into the room, and I can become very irritable if they don't appreciate that they are observing a writer seriously at work.

"What I'm doing, of course, is taking myself out of the world I'm in, and trying to find my way back into the world apart. Once I've managed that, I am inside the book that I'm writing, and am seeing it, so vividly that I do not see what I am actually staring at: the wall, or the typewriter, or the tree outside the window. I suppose it is a variety of trance state, though that's a perilous word. It makes one think of poor Coleridge,  waking from an opium-induced sleep with two hundred glowing lines of Kubla Khan in his head, being interrupted by a person from Porlock when he'd written down only ten of them, and finding, when the person had gone, that he'd forgotten all the rest. Trance is fragile.

waking from an opium-induced sleep with two hundred glowing lines of Kubla Khan in his head, being interrupted by a person from Porlock when he'd written down only ten of them, and finding, when the person had gone, that he'd forgotten all the rest. Trance is fragile.

"The world of the imagination is not fragile, not once you've reached it, but because it is set apart, you can never be sure of reaching it. It seems very curious to be standing here in the university which tried to teach me reason, and confessing to uncertainty and superstition of a kind which would have appalled my tutor. Reason, however, is singularly unhelpful to a novelist except in a few specialized situations, like the matter of chosing a publisher, or arguing points of English grammar with a copy editor. The imagination is not reasonable -- or tangible, or visible, or obedient. It's an island out in the ocean, which often seems to retreat as you sail toward it. Sometimes it vanishes altogether, mirage-like, and nothing can be done to bring it back into reach. This produces a bad day during which you write nothing of value and have to wait until tomorrow and start again.

"We cast spells to find our way into the unconscious mind, and the imagination that lives there, because we know it's the only way to get into a place where magic is made."

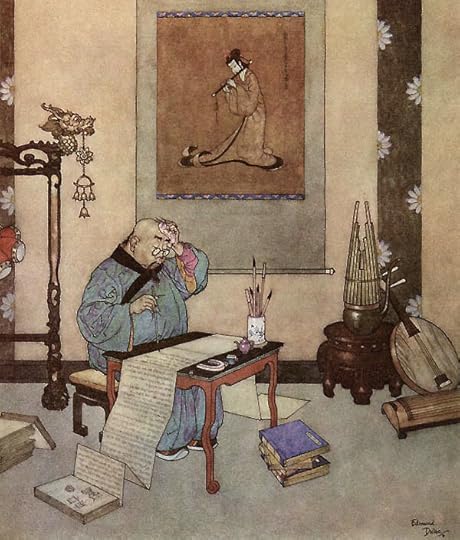

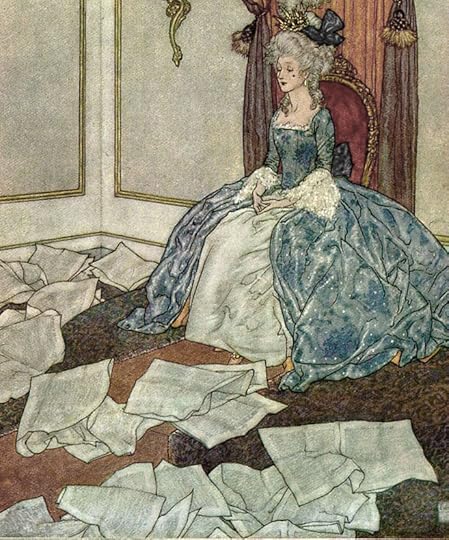

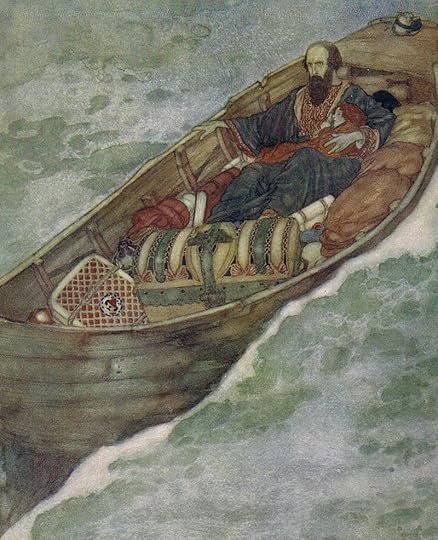

Pictures: The fairy tale illustrations above are by the great Golden Age book artist Edmund Dulac (1882-1953). Born in Toulouse, France, he moved to London in 1904, and became a naturalized British citizen in 1912. Words: The passage quoted above is from "Worlds Apart" by Susan Cooper, from her essay collection Dreams and Wishes (Margaret K. McKelderry, 1996). All rights reserved by the author.

How we begin

The theme I'm exploring this week is "writers and readers," beginning with a passage from I Could Tell You Stories by essayist & memorist Patricia Hampl:

"It still comes as a shock to realize that I don't write about what I know, but in order to find out what I know. Is it possible to convey the enormous degree of blankness, confusion, hunch, and uncertainty lurking in the act of writing? When I am the reader, not the writer, I too fall into the lovely illusion that the words before me, which read so inevitably, must also have been written exactly as they appear, rhythm and cadence, language and syntax, the powerful waves of the sentences laying themselves on the smooth beach of the page one after another faultlessly.

"But here I sit before a yellow legal pad, and the long lines of the preceding paragraph is a jumble of crossed-out lines, false starts, confused order. A mess. The mess of my mind trying to find out what it wants to say. This is a writer's frantic, grabby mind, not the poised mind of a reader waiting to be edified or entertained.

"I think of the reader as a cat, endlessly fastidious, capable by turns of mordant indifferance and riveted attention, luxurious, recumbent, ever poised. Whereas the writer is absolutely a dog, panting and moping, too eager for an affectionate scratch behind the ears, lunging frantically after any old stick thrown in the distance.

"The blankness of a new page never fails to intrigue and terrify me. Sometimes, in fact, I think my habit of writing on long yellow sheets comes from an atavistic fear of the writer's stereotypic 'blank white page.' At least when I begin writing, my page has a wash of color on it, even if the absence of words must finally be faced on a yellow sheet as much as on a blank white one. We all have our ways of whistling in the dark."

Indeed we do.

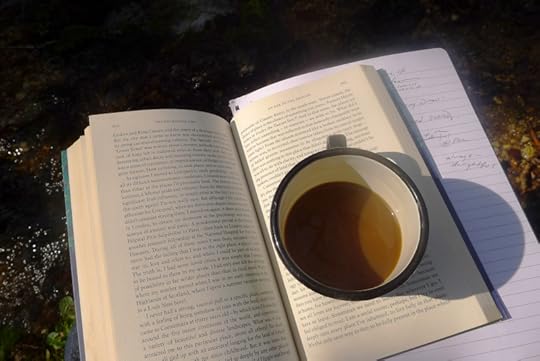

Mine, when possible, is beginning each new piece I write in a notebook outdoors. Away from my desk, computers, phones, from stacks of mail and schedules and lists, I am better able to find the words I need to carry me over the fear of "the blank white page" -- and once I bring these scribbles back to my desk, their momentum carries me forward.

Fellow writers (and other creators), what about you? How do you begin?

Words: The passage quoted above is from the essay "Memory and Imagination," published in I Could Tell You Stories: Sojourns in the Land of Memory by Patricia Hampf (W.W. Norton & Co., 1999). The piece in the picture captions is from Selected Poems by Welsh poet Gillian Clarke (Carcanet Press, 1985). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: An old stone wall between woods and hill, now overgrown with trees, grass, and moss. Devon folklore tells us that fairies love such liminal spaces, "betwixt and between." The hound and I love them too.

April 8, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Some tunes and songs from Scotland today....

Above: "Fair Weather Beggar" by Claire Hastings, a singer/songwriter based in Glasgow. It's from her new album, Those Who Roam, songs of journeys and travel (2019).

Below: The Trooper and the Maid," performed by The Claire Hastings Band at the Cottiers Theatre in Glasgow, 2016.

Above: "Montreal" by Talisk, a Scottish folk trio consisting of Mohsen Amini, Hayley Keenan, and Graeme Armstrong. The tune appears on their latest album, Beyond (2018).

Below: "Farewell" by Talisk, from the same album.

Above: "Miller Tae My Trade" performed by Scottish singer Hannah Rarity, with Innes White, Sally Simpson, and Conal McDonagh. It's from Rarity's debut EP, Beginnings (2017). Her first full album, Neath a Gloaming Star, was released last autumn.

Below: "I Once Loved a Lass" performed by Hannah Rarity, with Ryan MacKenzie and Bernadette Kellermann. The video was filmed at Castlesound Studios, Pencaitland (2016).

April 5, 2019

What we are here for

Kith and Kin

To end a week focused on the theme of "home, place, and connection to the land," I'd like to re-visit a post from 2015 that seems particularly germane, discussing home, homelessness, and the places that call to us in myth, fiction, and the real world....

Today, I'm thinking about the ways that some people's lives are defined by attachment to the place they come from, whereas others (in increasing numbers) live uprooted from their original place, or un-rooted in any place at all. The world has always had its wanderers, of course -- but the balance has shifted in modern times, with more of us in motion than staying put. As we move, and move, and move again, can  we genuinely root ourselves in each new place, learn the language of each land's flora and fauna, its myths and folklore, its unique spirit? Or are we doomed to transient, restless lives in which the voices of the land, of the plant world and our animal neighbors, are ones we can no longer hear?

we genuinely root ourselves in each new place, learn the language of each land's flora and fauna, its myths and folklore, its unique spirit? Or are we doomed to transient, restless lives in which the voices of the land, of the plant world and our animal neighbors, are ones we can no longer hear?

In discussing the Aboriginal culture of Australia, which, like most indigenous cultures, is deeply rooted in their sacred landscape from birth until death, Jay Griffiths writes:

"From song, from dream, from elements of earth and water, spirit-children are imminent in the land. They are left there by the Ancestors of the Dreaming, who sang their way across the land, leaving an imprint of music like an aural footstep. And sometimes a woman who has already physically conceived a child chances to step in that same footstep, and, if she does, part of the song and the spirit-child leap up into her so she feels a quickening, sharp as an intake of breath at a kick within, sweet as a night surprised by song. Sometimes it is the father who, seeing something unusual -- a particularly large fish or an animal behaving strangely -- may know it as an indication of a spirit-child. Or a man walking by a lake may find a spirit-child jumping into his mind, which he will send in a dream to his wife, inseminating the spirit-child within her. Then the Lawmen, the knowers of the songline which the mother or father was on, can tell which stanzas of the song belong to that child, its conception totem and, in that sinuous reflexivity of belonging, its quintessential home.

"To be born," notes Griffiths, "is, in Latin, nasci, and the word is related to natura, so birth, nature, the laws of nature and the idea of an essence are related. It is as if the language itself has embedded birth in the natural world. In the Amazon, people say childbirth should always take place in forest-gardens so that the condensed energy of the plants can nourish the child. In New Guinea, future generations are called 'our children who are still in the soil' and when I was in West Papua, the western half of the island, I was told that in the Dani language the expression for digging potatoes is the same as that for giving birth to a child. Women say they can sometimes hear the unearthed potatoes, which are always handled gently, calling out to them, the land singing things into being to be mothered into the world.

"Legends of childhood across the world suggest whole landscapes lit with incipience. Everywhere is potential, beginningness. It may be the inheld energy of an acorn or the liquid and endless possibilities of water; it may be the fattening of a potato in the secret earth or the leaping of a salmon that is the child Taliesin -- in whatever form it takes, the land itself is kindling children.

"In indigenous Australian culture," Griffiths continues, "there is a common idea that the land is a mentor, teacher, and parent to a child. People talk of being 'grown up by' their land; their country as kin. So do English-speakers -- without quite realizing it. A child may be looked after by its 'kith and kin,' we say, as if both terms meant family or relations. Not so. 'Kith' is from the Old English cydd, which can mean kinship but which in this phrase means native country -- one's home outside the house -- but no one I have ever met has known that meaning. This sense of belonging has nothing whatsoever to do with a nation state or political homeland, but rather with one's immediate locale, one's square mile, the first landscape that we know as children. W.H. Auden wrote of this as 'Amor Loci,' the love of his childhood landscape. Kith kindles the kinship which children so easily feel for the natural world and without that kinship, nature also loses out, bereft of the children who grow up to protect it."

Novelist Alan Garner's "kith" is in Cheshire in north-west England, where Garners have lived for centuries. As a descendant of rural craftsmen, he was the first of his family to attend a private grammar school and then go on to Oxford University. "My family," he writes (in The Voice That Thunders), "was, in the abstract, delighted that I was going to 'get an education,' just as I might have been going to get a car. For them it was a concrete object. None of us was prepared for its effect. That deep but narrow culture from which I came could not share my excitement over the wonders of the deponent verb. To them, it was an attack on their values, an attempt to make them feel inferior. A shocking alienation resulted, which we could not resolve."

At the end of his education, Garner sits on a stump by an old stone wall (built by his great-great-grandfather, Robert Garner) and ponders his future. His education has made it impossible for him to live as his father and grandfather lived, but the strength of his kith-ties makes the life of an Oxford don, living far from the soil of Cheshire, impossible too. What is the answer?

"It was staring me in the face. It was Robert's wall. On it was carved his banker mark, the rune Tyr, the boldest of the gods. When the Aesir went to bind Fenriswolf with the rope Gleipnir, which was made of the sound of a cat's footsteps, the beard of a woman, the roots of a mountain, the longings of a bear, the voices of fishes and  the spittle of birds, Fenris would not allow himself to be bound unless one of the Aesir put his right hand in Fenris' mouth as a token of goodwill. Only Tyr was willing to do so. And when Fenris was bound, and helpless, he bit Tyr's hand off at the wrist, which is still called the wolf's joint. But had Robert known this? Was it a part of the Craft and Mystery of his trade? Or was it simply that an arrow is easy to carve? Yet he had got the proportions of it right; and we are all left-handed.

the spittle of birds, Fenris would not allow himself to be bound unless one of the Aesir put his right hand in Fenris' mouth as a token of goodwill. Only Tyr was willing to do so. And when Fenris was bound, and helpless, he bit Tyr's hand off at the wrist, which is still called the wolf's joint. But had Robert known this? Was it a part of the Craft and Mystery of his trade? Or was it simply that an arrow is easy to carve? Yet he had got the proportions of it right; and we are all left-handed.

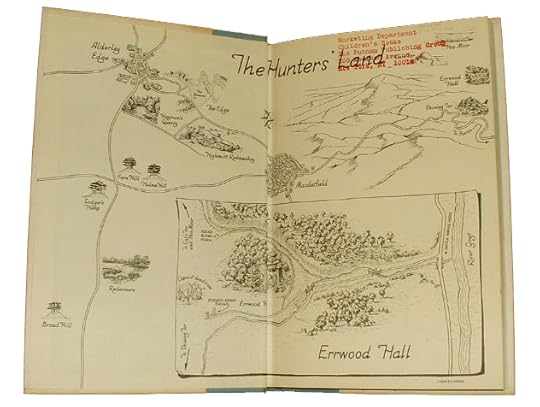

"I loved Oxford, but it was not the wall. The wall was mine. Oxford was not mine. The rune was mine. It claimed me. Whatever it was that I was going to do with my life, it would have to be done here. This was my unique place. I owned it, and it owned me. There is no word in English to express the relationship. In Russian, the word is rodina; in German, Heimat. And there, on the tree stump, by my great-great-grandfather's rune and wall, I saw my rodina, my Heimat. This is what I must serve, as no one else could. This is the integration of my divided selves....So, after a period of reflection, at three minutes past four o'clock on the afternoon of Tuesday, 4 September, 1956, I began to write a novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, and I have been writing ever since."

For writers like Garner, with a deep sense of belonging to an ancestral landscape, the creation of art rooted in and expressive of that landscape can be an almost sacred calling...but what about the rest of us in this fast-paced, foot-loose, transient world: immigrants, exiles, travelers, nomads, incomers of one form or another?

Katherine Paterson addressed this question in her essay "Where is Terabithia?":

Katherine Paterson addressed this question in her essay "Where is Terabithia?":

"Flannery O'Connor, whose words about writing have meant a great deal to me, has said that writing is incarnational. By incarnational we mean that somehow the word or the idea has taken on flesh, has become physical, actual, real. We mean that the abstract idea can be percieved by the way of the senses. This immediately makes fiction different from other kinds of stories. The fairy tale begins, 'Once upon a time,' thus clearly signaling its intent to escape the actual and the everyday, but a novel takes its life from the petty details of its geography, history, and culture.

"This is one of the reasons that writers like Flannery O'Connor and Eudora Welty and William Faulkner move us so powerfully. Their roots are planted very deep in a particular soil, and they grow up and reach out from that place with a strength unknown to most writers. It is also the reason why a writer like Pasternak would refuse the Nobel Prize rather than leave Russia. For Russia, despite her terror and oppression, was the soil from which his genius sprang, and he feared that if he left her, he would leave behind his ability to write.

"What happens, then," asks Paterson, "to a writer without roots -- who is not grounded in a particular place? When I was four years old, we left 'home,' and I've never been back since. Indeed, I couldn't go back if I wanted to because the house in which we lived was torn down so that a bus station could be built on the site. Since I was four, I've lived in three different countries and seven states at about thirty different addresses. I was once asked as part of an imaginative exercise to remember in detail the house I had grown up in. I nearly had a mental breakdown on the spot. But the fact that I have no one place to call home does not make me feel that place in fiction is unimportant. On the contrary, it convinces me that I must work harder than any almost any writer I know to create or re-create the world in which a story is set and grows if I want to make a reader believe it."

Many of us today have no kith, no rodina, no alia (to use the Islandian term), no ancestral place. Or we had one once, but lost it long ago. Or we've been transplanted into new soil, our roots still shallow, our claim still tenuous. Or we are homesick for a home we never actually had; for the idea of home, and of truly belonging.

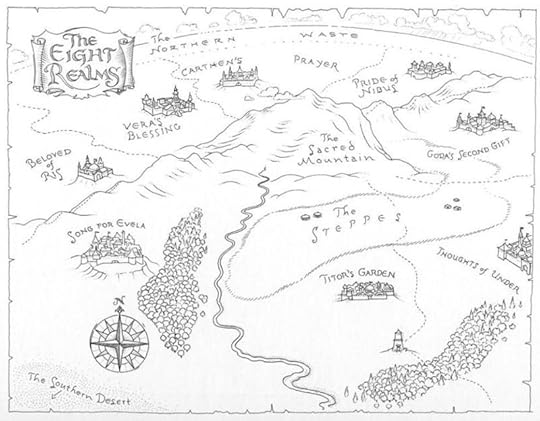

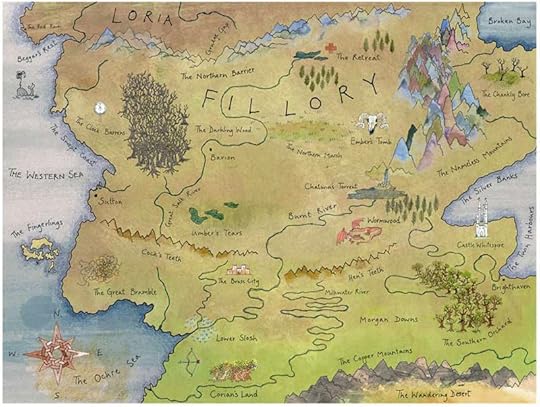

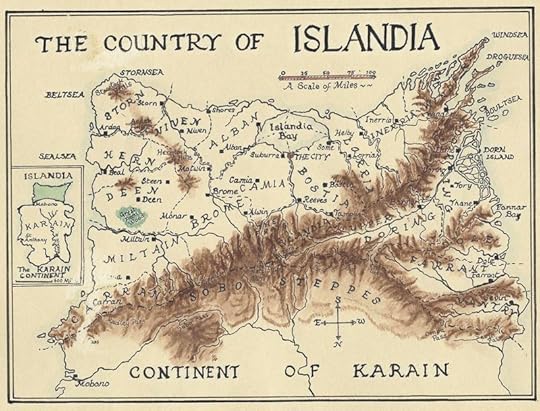

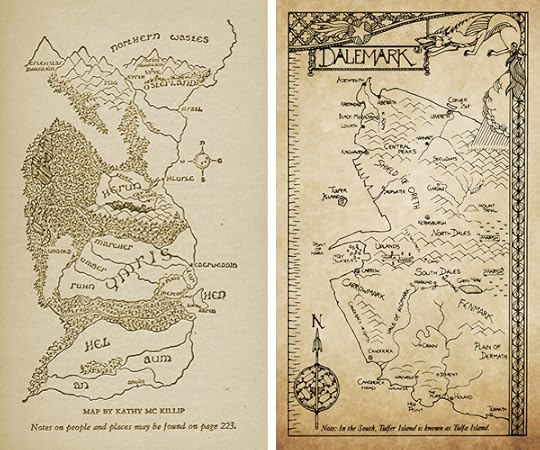

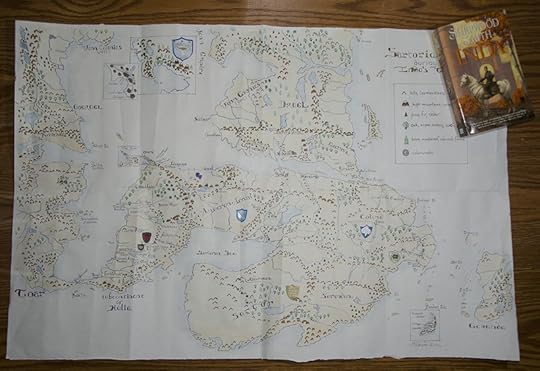

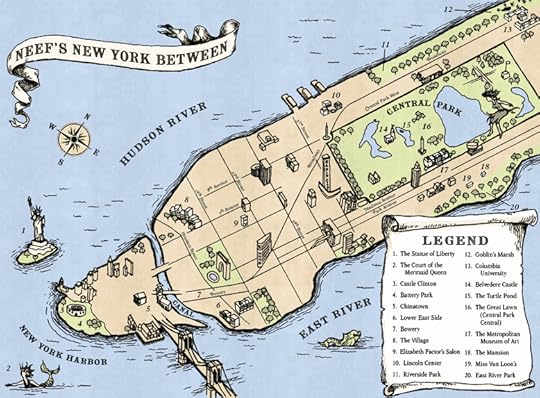

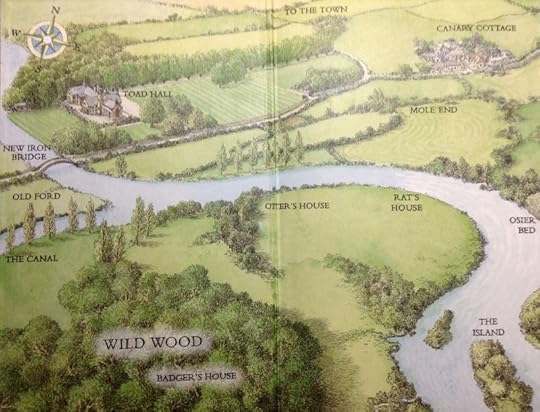

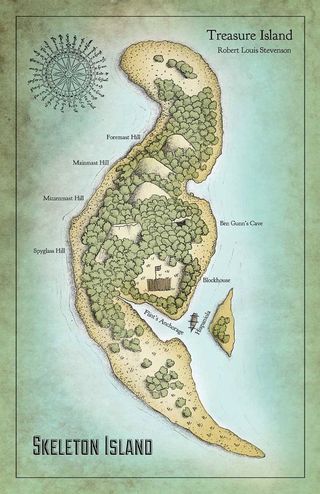

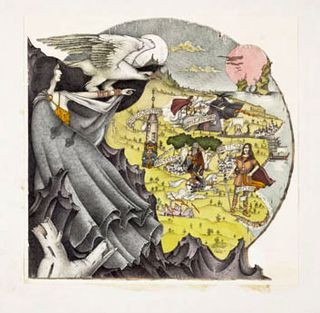

That's how it was for me for many years, until I crossed the ocean to Devon and, to my eternal surprise, its rain-drenched hills whispered in my ears: Welcome home. You've come at last. We've been waiting and waiting, and now you're here. Until then, I'd found my home in the world only in the pages of certain books, and in the earth-colored tones of certain works of art: in Earthsea and Islandia, Rhyhope Wood and the farmyards of Hed, among Burne-Jones' briar roses and Arthur Rackham trees with goblins stirring at their roots. Those imaginary lands are as precious to me now as they were in my kithless, unmoored youth, and they formed me as much as any "real" place. They are real places. Or rather, I should say that they are true places, which is even better; and which, of course, is precisely why I able to take shelter inside them. Some kiths exist in the physical world, and some only in the imagination. But all of them are real. All of them matter. All of them place us, nourish us, and give us the stories we most need.

That's how it was for me for many years, until I crossed the ocean to Devon and, to my eternal surprise, its rain-drenched hills whispered in my ears: Welcome home. You've come at last. We've been waiting and waiting, and now you're here. Until then, I'd found my home in the world only in the pages of certain books, and in the earth-colored tones of certain works of art: in Earthsea and Islandia, Rhyhope Wood and the farmyards of Hed, among Burne-Jones' briar roses and Arthur Rackham trees with goblins stirring at their roots. Those imaginary lands are as precious to me now as they were in my kithless, unmoored youth, and they formed me as much as any "real" place. They are real places. Or rather, I should say that they are true places, which is even better; and which, of course, is precisely why I able to take shelter inside them. Some kiths exist in the physical world, and some only in the imagination. But all of them are real. All of them matter. All of them place us, nourish us, and give us the stories we most need.

Now, as a writer and artist myself, my aim is to fashion, as Anais Nin once put it, "a world in which one can live"... out of words and paint, out of myth and life, out of rain, wind, earth and flame. I want to tell stories born of my love for Devon, but also for the Arizona desert and the lands I wandered during the homeless years: Narnia, Gramarye, Dorimare, Eldwold, Prydain, Dalemark, the Earthsea Archipelago, Vandarei, Tredana, the Old Kingdom, Dorn Island, and so many others. Most of all I, too, want to create landscapes and storyscapes so real, so vivid, so true that they might whisper in a weary traveler's ear:

Welcome home. You've come at last. We've been waiting and waiting, and now you're here.

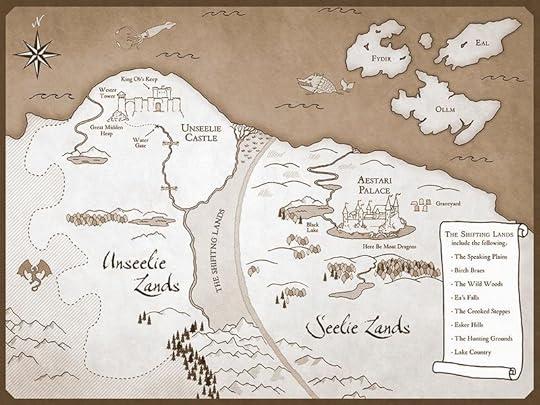

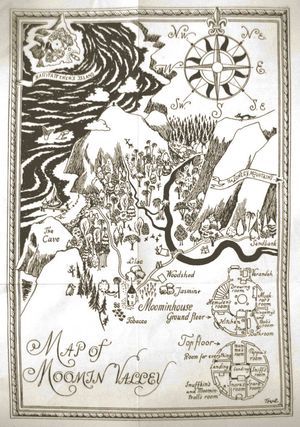

Map titles are in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) A related post, On Loss and Transfiguration, looks at the ways "loss of home" has shaped several writers of classic children's fiction.

April 4, 2019

Falling in love with a place

In yesterday's post, Sharon Blackie suggests that one way to feel at home wherever it is you find yourself planted is to "learn the ecology, history, language, culture, mythology of your place." Philip Marsden did exactly than when he moved into a tumbledown farmhouse in Cornwall. In his beautiful book Rising House: A Search for the Spirit of Place, he recounts his experience renovating the house, puzzles out the history of the land that it sits on, then widens his scope to the mythic and social history of Cornwall , tramping the land to better understand the rugged, wild county he loves.

"We weren't looking to move house," he writes. "We were perfectly happy living in a Cornish seaside village. Our children had just started at the primary school. We had a little boat, and I thought that after the chaotic years of early parenthood, a degree of control was once again settling over our lives. But that May, Charlotte spotted in the local newspaper an old farmhouse for sale. We arranged to view it -- curiosity, nothing more. Yet as we drove down the grass-centered track, and saw the arena of rounded hills and the network of oak-fringed creeks and the first glimpse of the house, its chimneys and slate roof rising from beyond a field of barley, I had the sense that our cozy domestic world was about to be shattered....

"Built at a time before railways made their full impact on Cornwall, the farmhouse was designed for work. The garden was a narrow strip of grass before the proper business of pasture. Mains power only reached the house in the 1980s; its water was still pumped up from a hand-dug well. A field was attached, and it rose slightly -- sheltering the house from the worst of the wind -- before dropping on three sides to the creek. Standing in the field on our first visit, seeing the house with only the roof and top-floor windows visible, I convinced myself that it represented an ageless integrity with the land around it, and felt sure it would pour beneficence over anyone lucky enough to live there. Such delusions are only possible for the besotted. In the days and weeks that followed, I learned that 'falling in love with a place' meant exactly that -- with all its downsides, its yearnings and mood swings."

But the progress of love was not smooth. Marsden and his wife put their seaside house on the market, but could find no buyer. A year passed, and the farmouse was withdrawn from sale. Then, just as suddenly, it was back on the market again.

"Now like a stalker, I began to take real walks down through the woods towards it," he relates. "I learnt to anticipate the exact point, just under a mile away, where the roof would appear through the trees (beside the pheasant pens, on the edge of the maize field). The path led down toward a side creek and the house was then lost from view -- but I could see the field across the corridor of mud flats and the sessile oaks that bordered it. Every tree and shrub I scrutinized. I knew it was unwise to dwell on something that might never happen -- but, well, I couldn't help myself.

"Another year passed. Our house did not sell. Viewers came and went. Buyers turned out not to be buyers. The banks froze up. And then, suddenly, it was all resolved. A date was fixed. I scrambled to finish the manuscript of a book and sent it off to my publisher just days before the removal lorries arrived. Clearing out years of accumulated junk, burning papers, scooping up yards and yards of books, watching the dismantling of rooms I had known all my life, the stripping of a house I had once yearned for in the same way, I felt only reckless excitment about what was ahead. I kept expecting the leg-buckling coup of nostalgia, even the tiniest stab of sadness or regret -- but it never came."

They move into the farmhouse at last, and begin the long, slow work of reclaiming a place neglected for many years -- recovering the farm's original features, its kitchen garden, its history. Marsden writes:

"Long before the farmhouse was built in the mid-nineteenth century, a substantial manor had stood on the site -- not exactly here, but eighty meters or so towards the creek. In the diocesan records, there remain a few scant references to the house, to its lands stretching many miles to the south, and to a Norman family, the Petits, who owned it all. A strategic position on the river -- as well as the ancient Cornish name [Ardevora] -- suggests long use of the site, and I imagined it as one of those hubs in the nation-of-sorts that once connected estuaries in Wales and Ireland and Brittany, Iberia and Scotland.

"In 1420, an application was made by the Petits to build a chapel. But within a century, the estate was breaking up. A generation of daughters married away -- the eldest into the Killigrew family, whose lands at the mouth of the Fal were better suited to the new age. The upper reaches of the river, a conduit for Cornish tin since antiquity, were suffering a slow paralysis. Silt was clogging the riverbed, pushing the navigatable waters far back to the open sea.

"One evening, working on a length of overgrown wall, I sliced through the stem of a cotoneaster, yanked it out and exposed what looked like part of a large stone basin. I cleared the roots and found it was a piece of black granite, dry-laid on the slate wall. I heaved it free. Upended on the grass, it was clear what it was: a piece of medieval tracery, the top half of a cinquefoil window. The chapel! I ran my fingers along the crescent edges of the rebate. I thought of sunlight falling through the glass, patterning the wood benches below and morning prayers, and the yards around the building busy with animals and work, and ships at anchor in the deep-water creek, and the mingle of Breton and Cornish, Welsh and Irish.

"Knowing a little of the past brought with it the first sense of belonging. In 1954, Martin Heidegger wrote in an influential essay called 'Building Dwelling Thinking,' in which he explores the close connection of the three '-ings' of his title -- a connection emphasized by his mannered omission of commas. He takes as his example a two-hundred-year-old farmhouse in the Black Forest. Such a place -- with echoes of Ardevora -- combined religious belief, domestic life and local topography: 'Here the self-sufficiency of the power to let earth and heaven, divinities and mortals, enter in simple oneness into things, ordered the house. It placed the farm on the wind-sheltered mountain slope looking south, among the meadows close to the spring.'

" 'Dwelling' for Heidegger meant much more than just living in a house. It described a way of being in the world. In Old English and High German, he shows how the word buan -- meaning both 'building' and 'to dwell' -- is linked to the verb 'to be.' (The same is true of Cornish and Brittonic languages: bos in Cornish is a verbal noun meaning both 'to be' and a 'building' or 'dwelling.') So to be is 'to be in a place.' Only by knowing our surroundings, being aware of topography and the past, can we live what Heidegger deems an 'authentic' existence. Heidegger is pretty severe about what constitutes authenticity, but his 'dwelling' does highlight something we've lost in our hyper-connected world, something I found myself rediscovering that spring down the end of a long track: the ability to immerse ourselves in one place. Heidegger also wrote: 'Only if we are capable of dwelling, only then can we build' (his italics). I felt he was pointing his magisterial finger directly at me."

If you'd like to know more about Marsden's Rising Ground, I wrote about it here, in 2015, after my first read of it. (I'm half-way through my second read now, and finding it even more interesting this time around.) You'll also find a good interview with the author on the Granta website here.

The photographs today were taken on a sheep farm here in Devon. I'm afraid they don't relate to the text very well, but these sweet and gentle creatures are simply too lovely not to share. Perhaps the connection is that my love for Devon is every bit as strong as Marsden's for Cornwall.

Words: The passage quoted above is from Rising Ground by Philip Marsden (Granta, 2014). The poem in the picture captions is about abstract painter Bryan Wynter (1915-1975), who lived in Zennor on the Cornish coast. It's from Selected Poems by W.S. Graham (Ecco Press, 1980). All rights reserved by the authors.

April 3, 2019

The places that claim us

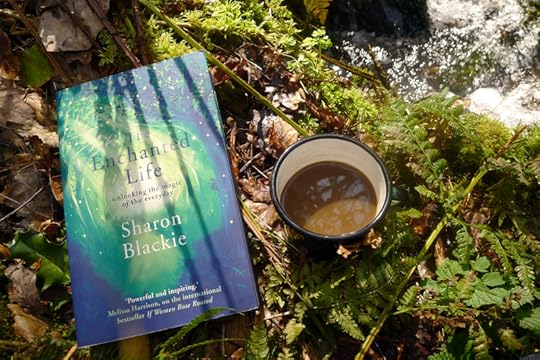

Here's one more passage from The Enchanted Life by Sharon Blackie, reflecting on her own life's journey and the "holy mysteries of place":

"I never had a strong, visceral pull to a specific place, combined with a feeling of somehow being in tune with the land, until I first came to Connemara at thirty years old -- by which time I'd travelled around the five major continents of the world, and experienced a variety of beautiful and diverse landscapes. What was it that attracted me to this place, above all others? No doubt it was all tied up with an ancestral longing for the land of Ireland which had been with me since childhood. But it was more than that, because I hadn't been affected so deeply by any other place in Ireland, including the equally wild and beautiful Dingle and Iveragh peninsulas of County Kerry, in the south-west.

"I never had a strong, visceral pull to a specific place, combined with a feeling of somehow being in tune with the land, until I first came to Connemara at thirty years old -- by which time I'd travelled around the five major continents of the world, and experienced a variety of beautiful and diverse landscapes. What was it that attracted me to this place, above all others? No doubt it was all tied up with an ancestral longing for the land of Ireland which had been with me since childhood. But it was more than that, because I hadn't been affected so deeply by any other place in Ireland, including the equally wild and beautiful Dingle and Iveragh peninsulas of County Kerry, in the south-west.

"'Never casual, the choice of place is the choice of something you crave,' Frances Mayes writes in Under the Tuscan Sun. And in that sense, the places we love reflect some something -- or someone -- we wish to be. What did I wish to become that was reflected in that famously changeable west coast light? From the islands scattered like a broken necklace in its stormy seas, to its crystal-clear interior lakes; from its central ranged of folded granite mountains to its ubiqitous wide-open bogs -- there was nothing in this place that didn't speak to me. The message was all to do with clarity, and integrity: the commanding, unrelenting presence of land that is entirely and fully itself -- that couldn't be broken, couldn't possibly ever be made into something else.

"Connemara was, quite simply, the place where I began to wake up. It is also the place where I have finally been able to return. I believe, too, that it's the place where I'll stay -- because sometimes, like your first 'proper' human love, the place that you first truly love will hook itself deep into your heart and won't let you go. Sometimes a place just claims you, right from the very beginning. Mine, it says. Mine. And nowhere else, not even remotely, will ever really feel like home....

"I've always believed you can learn to sort-of-belong to any place, if you choose -- indeed, that there's a moral imperative to do so, because the land which bears us and nourishes us deserves no less of us. I know how to cultivate that kind of belonging. Learn the ecology, history, language, culture, mythology of your place. Go out into it for long periods of time, every day. Sit in the same place every day for an entire year, in all the seasons and weathers; talk to the land and listen to it, and maybe then you have some claim on belonging to it. And a feeling of being at home, for however long you happen to be in that place -- because not all loves are forever; not all places are forever. Sometimes we have to leave. Sometimes we need to leave. But wherever I go, I feel obligated to root. I am a serial rooter, perhaps, but I try to root deeply into every place I've inhabited, to live fully in that place. It's the only sane way to live: to be fully present in the place where your feet are actually planted, right here, right now. It's also the only way to live that is deeply respectful of the earth.

"That's one kind of belonging: the kind you learn to do, wherever it is that you happen to be living at the time. Then there's the feeling of belonging that comes with heritage: a sense of belonging to a place which you may or may not ever inhabit, which is encoded in your DNA....

"But maybe there's another kind of belonging altogether: the kind of belonging that happens when a place claims you -- when it makes itself known to you, and you in turn open yourself fully to it. These are the places we've been to once, but can't get out of our heads; the places we can't seem to help but return to on vacation, year after year; the places we look for as settings in the novels we choose to read.

"This 'claiming' kind of belonging is expressed perhaps in the beautiful old story of Gobnait, an Irish saint who lived in the early sixth century. Gobnait was born in County Clare, and when she was older she fled a family feud, taking refuge in Inis O��rr in the Arran Islands. While she was there,  an angel appeared and told her she must leave, because this was 'not the place of her resurrection.' She should, the angel said, look for a place where she would find nine white deer grazing.

an angel appeared and told her she must leave, because this was 'not the place of her resurrection.' She should, the angel said, look for a place where she would find nine white deer grazing.

"So Gobnait wandered through Waterford, Kerry and Cork. First she saw three white deer in Clondrohid in County Cork, and she followed them to Ballymakeera, where she saw six more. But it wasn't until she arrived in Ballyvourney, in the south-west corner of Cork, that Gobnait saw nine white deer grazing all together. This was where she settled, and founded her monastic community. That was the 'place of her resurrection,' and there she remained: a beekeeper, and a woman who is now thought of as the patron saint of bees.

"From the first moment I heard the story of Gobnait, it resonated with me, and with a life in which I'd been wandering, like her, from place to place, in search of who knows what. Learning to sort-of-belong to each of them, but always, sooner or later, feeling some sense of being driven on. In search of the 'place of my resurrection'? The place where the soul is happiest on earth, from where it will happily and freely leave the body, when the time comes? It's been rambling and rather peripatetic, this journey of mine. I've imagined time and again that I've found my final resting place, when in fact what I've found were beautiful but temporary sanctuaries along a path I didn't even know I was following -- each place offering its own lessons, its own transformations.

"But these days, with the benefit of long perspective, above all I see my journey from place to place not so much as a form of restless wandering, but as the acceptance of an invitation -- an invitation to delve more deeply into the holy mysteries of place. And I see myself undertaking that journey as pilgrims do, knowing that something is lacking, but not ever knowing quite what it was until they've reached their journey's end.

"So here I am: not really a line but a meshwork of places. A unique web of placeworlds lives in me -- informing, creating, teaching, as I've walked my own Dreaming into the land. Places that made me -- literally, contributing air and water and food; places where I've left parts of myself behind -- contributing skin cells, hairs, bodily fluids, breath. But through it all, there has always been Connemara. Tugging, tugging. Nipping. Biting. Itching. Come home, Connemara called, and I did."

Words: The passage above is from The Enchanted Life: Unlocking the Magic of the Everyday by Sharon Blackie (September Publishing, 2018). The poem in the picture captions, based on the folk custom of "telling the bees" of a death in the household and other major life events, is from Poetry magazine (September 2008). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: A vintage drawing of a bee skep (artist unknown), a deer drawing by Walter Crane (1845-1915), and photographs of the hills that claimed me many years ago, on the edge of Dartmoor.

April 2, 2019

Knowing our place

Continuing last week's conversation on the connection between our interior and exterior landscapes, here's a passage from Sharon Blackie's fine book The Enchanted Life:

"We think of ourselves as 'in' landscape, but sometimes we forget that landcape is also in us. We are formed by the ground we walk on: that which lies beneath our feet. That which holds us, supports us, feeds us. Ground is where we stand, the foundation for our lives. Whether its hard and cold or warm and soft, ground is the foundation of our being in the world.

"Ground is the safe place at the heart of us; we 'go to ground' when we are trying to hide or escape from something which is hurting us. We 'hold our ground' when we stand firm against something which challenges or threatens us. We 'have an ear to the ground' when we are properly paying attention to what is going on around us. To 'keep our feet on the ground' is to be realistic, not to get too big for our boots. Without ground, we are nothing.

"Some pieces of ground are also 'places.' To find our ground, then, is to find our place -- but what makes ground into a place is so much more than just a defined (or confined) location. Places have their own distinct names, features, landforms, environmental conditions -- but places are more than just physical: they are reflections of the human cultures which formed from them and belong to them.

"As human animals who are inextricably enmeshed in the world around us, it is hardly surprising that the nature of our relationship with our places is critical to our ideas about who we are, and what it might be possible for us to become. We construct the daily texture of our lives and our systems of meaning in relation to our places: they are part of our existence, intrinsic to our being; they are more fundamental to us than the language we speak, the jobs we hold, the buildings we live in and the things we possess. It's in our places that we come face to face with (or sometimes, perhaps, choose to turn away from) the bright face of the Earth to which we belong. The need to make sense of, and find meaning in, our relationship to the places we inhabit is a fundamental and universal part of the human journey in this world.

"To put it quite simply, we cannot be human without the land. Our humanity cannot exist in isolation: it requires a context, and its context is this wide Earth that supports us, and the non-human others who share it with us.

"Every ecology, every community of plants and animals and soil, has its own particular kind of personality, or intelligence, which affects the people who live in it many different ways. We all know it; we feel it in the places we live, and we feel it especially as we move around the planet. Modern science might use different words, but it tells us exactly the same thing: the topography of a place, its weather, the flora and fauna which inhabit it alongside us -- all these aspects of a place contribute to the character and sense of identity of the people who live there. The experience of inhabiting high, bare granite hills bears little similarity to the experience of inhabiting lush, grassy, chalk downlands; to occupy a city, with its manufactured concrete floors and walls, shapes you in an altogether different way.

"Psychologist Carl Jung called this process of shaping 'the conditioning of the mind by the earth': every country, he said, along with the people who belong to it, is characterized by a collective attitude or state of mind called the spiritus loci. 'The soil of every country holds...mystery,' he wrote. 'We have an unconscious reflection of this in the psyche.' "

"I have lived in several countries, and spent time in many different landscapes during my life," Blackie notes, "and each in its own way has left its mark on me. Inside me is [a remote Scottish island] on which I once became stranded, castaway; on which I merged so deeply with the oldest, hardest rock on the planet that I feared petrification. But inside me too is the gentleness of the rain-haunted west of Ireland, and the dense silence of a misty early morning bog. There is a stripped-to-the-bone south-western American desert, fierce sun laying bare all my imagined inadequacies; there are lush green oak-groves in an ancient Breton wood where Merlin sleeps still, trapped in a tree. I am a collection of all the landscapes I have loved.

"I have never been rainforest, though, and I could never be jungle -- there is nothing of me or mine in those humid, colourful, shouting places. And isn't this true for so many of us? That there is a single kind of landscape in which we feel a sense of homecoming; a particular kind of landscape in which we feel so much more whole? For the lucky ones among us, those are the landscapes in which we finally have come to rest; for others, they're the hauntingly vivid landscapes of the imagination which never quite let us go.

"What surprises me still, perhaps, is that so many of us can resonate so deeply with a landscape we've imagined, but to which we've never actually been. In his masterful book Space and Place, geographer Yi-Fu Tuan offers the example of C.S. Lewis, a lifelong devotee of the far north. As we can clearly see from the vividly portrayed winterlands of his Narnia chronicles, Lewis loved the idea of 'northerness.' It was, Tuan says, a vision of huge, clear spaces hanging above the Atlantic in the endless twilight of northern summer which drew him, and which appealed to something very deep in his psyche. But not only did Lewis never live in northern lands -- he never even travelled to the extreme north.

"We think we imagine the land," she concludes, "but perhaps the land imagines us, and in its imagining it shapes us. The exterior landscape interacts with our interior landscape, and in the resulting entanglements, we become something more than we otherwise could ever hope to be."

Words: The passage above is from The Enchanted Life: Unlocking the Magic of the Everyday by Sharon Blackie (September Publishing, 2018). The poem in the picture captions is from Rounding the Human Corners by Chickasaw poet Linda Hogan (Coffee House Press, 2008). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Waterfalls swelled with winter rains on our greening, dreaming hillside.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers