Terri Windling's Blog, page 65

March 6, 2019

Living in a storied world

From "Storytelling and Wonder: On the Rejuvenation of Oral Culture" by David Abram:

"In the prosperous land where I live, a mysterious task is underway to invigorate the minds of the populace, and to vitalize the spirits of our children. For a decade, now, parents, politicians, and educators of all forms have been raising funds to bring computers into every household in the realm, and into every classroom from kindergarten on up through college. With the new technology, it is hoped, children will learn to read much more efficiently, and will exercise their intelligence in rich new ways. Interacting with the wealth of information available on-line, children���s minds will be able to develop and explore much more vigorously than was possible in earlier eras -- and so, it is hoped, they will be well prepared for the technological future.

"In the prosperous land where I live, a mysterious task is underway to invigorate the minds of the populace, and to vitalize the spirits of our children. For a decade, now, parents, politicians, and educators of all forms have been raising funds to bring computers into every household in the realm, and into every classroom from kindergarten on up through college. With the new technology, it is hoped, children will learn to read much more efficiently, and will exercise their intelligence in rich new ways. Interacting with the wealth of information available on-line, children���s minds will be able to develop and explore much more vigorously than was possible in earlier eras -- and so, it is hoped, they will be well prepared for the technological future.

"How can any child resist such a glad initiative? Indeed, few adults can resist the dazzle of the digital screen, with its instantaneous access to everywhere, its treasure-trove of virtual amusements, and its swift capacity to locate any piece of knowledge we desire. And why should we resist? Digital technology is transforming every field of human endeavor, and it promises to broaden the capabilities of the human intellect far beyond its current reach. Small wonder that we wish to open and extend this powerful dream to all our children.

"It is possible, however, that we are making a grave mistake in our rush to wire every classroom, and to bring our children online as soon as possible. Our excitement about the internet should not blind us to the fact that the astonishing linguistic and intellectual capacity of the human brain did not evolve in relation to the computer. Nor, of course, did it evolve in relation to the written word. Rather it evolved in relation to orally told stories. Indeed, we humans were telling each other stories for many, many millennia before we ever began writing our words down -- whether on the page or on the screen.

"Spoken stories were the living encyclopedias of our oral ancestors, dynamic and lyrical compendiums of practical knowledge. Oral tales told on special occasions carried the secrets of how to orient in the local cosmos. Hidden in the magic adventures of their characters were precise instructions for the hunting of various animals, and for enacting the appropriate rituals of respect and gratitude if the hunt was successful, as well as specific insights regarding which plants were good to eat and which were poisonous, and how to prepare certain herbs to heal cramps, or sleeplessness, or a fever. The stories carried instructions about how to construct a winter shelter, and what to do during a drought, and -- more generally -- how to live well in this land without destroying the land���s wild vitality.

"Such practical intelligence, intimately related to a particular place, is the hallmark of any oral culture. Continually tested in interaction with the living land, altering in tandem with subtle changes in the local earth, even today such living knowledge resists the fixity and permanence of the printed page. Because it is specific to the way things happen here, in this high desert -- or coastal estuary, or mountain valley -- this kind of intimate intelligence loses its meaning when abstracted from its terrain, and from the particular persons and practices that are a part of its terrain. Such place-specific savvy, which deepens its value when honed and tempered over the course of several generations, forfeits much of its power when uprooted from the soil of its home and carried -- via the printed page or the glowing screen -- to other places. Such intelligence, properly speaking, is an attribute of the living land itself; it thrives only in the direct, face-to-face exchange between those who dwell and work in this place.

"So much earthly savvy was carried in the old tales! And since, for our indigenous ancestors, there was no written medium in which to record and preserve the stories -- since there were no written books -- the surrounding landscape, itself, functioned as the primary mnemonic, or memory trigger, for preserving the oral tales. To this end, diverse animals common to the local earth figured as prominent characters within the oral stories -- whether as teachers or tricksters, as buffoons or as bearers of wisdom. Hence, a chance encounter with a particular creature as a tribesperson went about his daily business (an encounter with a coyote, perhaps, or a magpie) would likely stir the memory of one or another story in which that animal played a decisive role. Moreover, crucial events in the stories were commonly associated with particular sites in the local terrain where those events were assumed to have happened, and whenever one noticed that place in the course of one���s daily wanderings -- when one came upon that particular cluster of boulders, or that sharp bend in the river -- the encounter would spark the memory of the storied events that had unfolded there....

"There is something about this storied way of speaking -- this acknowledgement of a world all alive, awake, and aware -- that brings us close to our senses, and to the palpable, sensuous world that materially surrounds us. Our animal senses know nothing of the objective, mechanical, quantifiable world to which most of our civilized discourse refers. Wild and gregarious organs, our senses spontaneously experience the world not as a conglomeration of inert objects but as a field of animate presences that actively call our attention, that grab our focus or capture our gaze. Whenever we slip beneath the abstract assumptions of the modern world, we find ourselves drawn into relationship with a diversity of beings as inscrutable and unfathomable as ourselves. Direct, sensory perception is inherently animistic, disclosing a world wherein every phenomenon has its own active agency and power.

"When we speak of the earthly things around us as quantifiable objects or passive 'natural resources,' we contradict our spontaneous sensory experience of the world, and hence our senses begin to wither and grow dim. We find ourselves living more and more in our heads, adrift in a sea of abstractions, unable to feel at home in an objectified landscape that seems alien to our own dreams and emotions. But when we begin to tell stories, our imagination begins to flow out through our eyes and our ears to inhabit the breathing earth once again. Suddenly, the trees along the street are looking at us, and the clouds crouch low over the city as though they are trying to hatch something wondrous. We find ourselves back inside the same world that the squirrels and the spiders inhabit, along with the deer stealthily munching the last plants in our garden, and the wild geese honking overhead as they flap south for the winter. Linear time falls away, and we find ourselves held, once again, in the vast cycles of the cosmos -- the round dance of the seasons, the sun climbing out of the ground each morning and slipping down into the earth every evening, the opening and closing of the lunar eye whose full gaze attracts the tidal waters within and all around us.

"For we are born of this animate earth, and our sensitive flesh is simply our part of the dreaming body of the world. However much we may obscure this ancestral affinity, we cannot erase it, and the persistance of the old stories is the continuance of a way of speaking that blesses the sentience of things, binding our thoughts back into the depths of an imagination much vaster than our own. To live in a storied world is to know that intelligence is not an exclusively human faculty located somewhere inside our skulls, but is rather a power of the animate earth itself, in which we humans, along with the hawks and the thrumming frogs, all participate."

(You can read the full essay here.)

Yes, I'm aware of the irony inherent in using a digital space to discuss our culture's over-reliance on mediating life through phone and computer screens. The Internet is a wonderful tool -- but like all powerful magicks, as folklore tells us over and over, we must learn to use it wisely. In my own life, I prefer face-to-face conversation over texts and phones; printed books over words on a screen; storytelling and theatre unfolding in real time over drama slickly produced by the burghers of Hollywood. Don't get me wrong: I don't disdain modern media altogether; there is good to be found in almost all forms art. But my soul craves the touch of the wind and the rain, of stories that are sensory, intimate, and on a more human scale. As a writer and painter, my work is born from a hunger for life deeply rooted in nature, richly entwined with the more-than-human world. And as a blogger, if typing these words on a screen can prompt even one person to turn off their computer and go for a walk outside today, then my work here is done.

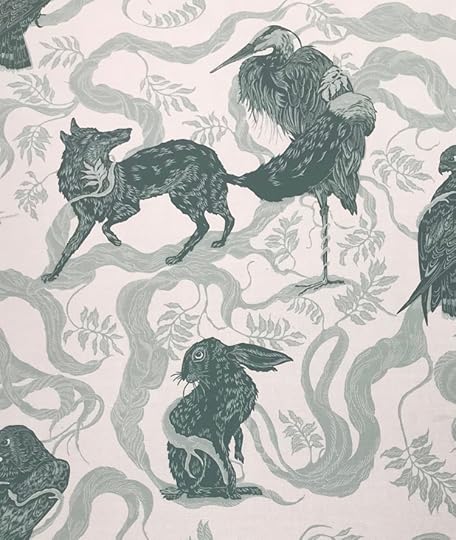

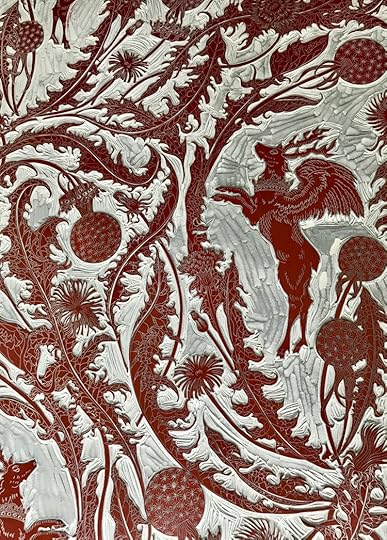

The exquisite art in this post is by Cally Conway, a British printmaker specializing in linocuts.

"For me, nature is not only beautiful and essential, but it continually inspires and sustains me," she says. "Being in nature makes me feel that everything is alright with the world, even if it���s not. And I think too many of us have lost touch with that. So I like to try and capture its beauty if I can, and maybe distill some of that. With my interest in folklore, sometimes it���s not that obvious, but I love finding out stories and meanings associated with plants or animals. When I���m creating a print I will research any folklore associated with what I want to include so that there might be a connection between the different elements.

"Living in London you could say it would be hard to find any aspect of nature to work from, but in truth there���s actually lots in London if you know where to find it! I spend most of my time at Kew Gardens and Hampstead Heath. I���m lucky enough to live really near Hampstead Heath and just a short train ride from Kew. Since becoming a member of Kew Gardens a few years back I can honestly say it feels like a second home. "

To see more of her work, please visit her website and shop. You can also follow her on Instagram and Twitter.

The passages above are from "Storytelling and Wonder" by David Abram, first published in Resurgence (Issue 222, Jan/Feb 2004). David's books, The Spell of the Sensuous and Becoming Animal, were influential texts for me (particularly Spell, when I was writing The Wood Wife), and I highly recommend them. The Cally Conway quotes are from an interview with the artist conducted by Claire Leach. All rights to text and art in this post are reserved by the authors and artist.

March 5, 2019

The call

From "The Miracle of the Mundane" by Heather Havrilesky:

"On a good day, humankind's creations make us feel like we're here for a reason. Our belief sounds like the fourth molto allegro movement of Mozart's Symphony no. 41, Jupiter: Our hearts seem to sing along to Mozart's climbing strings, telling us that if we're patient, if we work hard, if we believe, if we stay focused, we will continue to feel joy, to do meaningful work, to show up for each other, to grow closer to some sacred ground. We are thrillingly alive and connected to every other thing, in perfect, effortless accord with the natural world.

"On a good day, humankind's creations make us feel like we're here for a reason. Our belief sounds like the fourth molto allegro movement of Mozart's Symphony no. 41, Jupiter: Our hearts seem to sing along to Mozart's climbing strings, telling us that if we're patient, if we work hard, if we believe, if we stay focused, we will continue to feel joy, to do meaningful work, to show up for each other, to grow closer to some sacred ground. We are thrillingly alive and connected to every other thing, in perfect, effortless accord with the natural world.

"But it's hard to sustain that feeling, even on the best of days -- to keep the faith, to stay focused on what matters most -- because the world continues to besiege us with messages that we're failing. You're feeding your baby a bottle and a voice on the TV tells you that your hair should be shinier. You're reading a book but someone on Twitter wants you to know about a hateful thing a politician said earlier this morning. You are bedraggled and inadequate and running late for something and it's always this way. You are busy and distracted. You are not here."

"We are living in a time of extreme delusion, disorientation, and dishonesty," Havrilesky notes later in the essay. "At this unparalleled moment of self-consciousness and self-loathing, commercial messages have replaced real connection or faith as our guiding religion. These messages depend on convincing us that we don't have enough yet, and that everything valuable and extraordinary exists outside of ourselves.

"It's not surprising that in a culture dominated by such messages, many people believe that humility will only lead to being crushed under the wheels of capitalism or subsumed by some malevolent force that abhors weakness. Our anxious age erodes our ability to be open and show our hearts to each other. It severs our ability to connect to the purity and magic that we carry around inside us already, without anything to buy, without anything new to become, without any way to conquer and win the shiny luxurious lives we're told we deserve. So instead of passionately embracing the things we love the most, and in doing so reveal our fragility and self-hatred and sweetness and darkness and fear and everything that makes us whole, we present a fractured, tough, protected self to the world. Our shiny robot soldiers do battle with other shiny robot soldiers, each side calling the other side 'terrible,' because in a world that can't see poetry or recognize the divinity of each living soul, fragility curdles into macho toughness and soulless rage. All nuance is lost in a fearful rush to turn every passing though or idea or belief into dogma.

"Against this landscape, anything that celebrates the wildness and complexity of the human soul is worthy of celebration. This is true in a global sense, in communities, and it's true within a single human being. The antidote to a world that tells us sick stories about ourselves and and poisons us into thinking we're helpless is believing in our world and in our communities and in ourselves."

"We are called to resist viewing ourselves as consumers or as commodities," she concludes. "We are called to savor the process of our own slow, patient development, instead of suffering in an enervated, anxious state over our value and our popularity. We are called to view our actions as important, with or without consecration by forces beyond our control. We are called to plant these seeds in our world: to dare to tell every living soul that they already matter, that their seemingly mundane lives are a slowly unfolding mystery, that their small choices and acts of generosity are vitally important. "

I couldn't agree more.

I highy recommend seeking out Havrilesky's inspiring essay to read in full -- which you'll find it in her new collection What If This Were Enough?, along with other treasures. (Her essay on the subject of "bravado" is another one I can't stop thinking about.)

Words: The passages above are from What if This Were Were Enough? by Heather Havrilesky (Doubleday, 2017). The poem in the picture captions is from The House of Belonging by David Whyte (Many Rivers Press, 1997). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Dartmoor ponies grazing in the bog-land by the village Commons on a wet and wild day. The drawing is by English illustrator John D. Batten (1860-1932), who was born just across the moor in Plymouth.

A few related posts: For a discussion of avoiding the tyrany of critical voices on the Internet (and inside on our own heads), see "On Fear of Judgement." For a variety of thoughts on living life deliberately and contemplatively, see the thread of writings under the topic In Praise of Slowness.

March 3, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm inspired by the stars this week, and remembering something Carl Sagan once said: "The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself."

Above: "North Star" by Kyle Carey, based in Brooklyn, New York. The song was the title track of her second album, blending Scottish Gaelic and American roots music. I recommend it highly, along with her lastest: The Art of Forgetting.

Below: "Far Beyond the Stars" by The Henry Girls (sisters Karen, Lorna, and Joleen McLaughlin), from the west of Ireland. It's from their new album of the same name, released in January.

Above: "Bright Morning Star," an Applachian spiritual performed by Cara Dillon, from Northern Ireland. The song appeared on her fifth solo album, A Thousand Hearts (2014). If this video won't play in your area, you can watch it on YouTube here.

Above: "Underneath the Stars" by Kate Rusby, from Barnsley, South Yorkshire. This haunting song was the title track of her sixth solo album in 2003.

Below: "Staring at the Stars" by Salt House (Jenny Sturgeon, Ewan MacPherson and Lauren MacColl), a folk trio based in Scotland. It's from their thoroughly gorgeous new album Undersong (2017), recorded on the tiny island of Berneray in the Outer Hebrides.

Below: "All the Stars Are Coming Out Tonight" by singer-songwriter John Boden (formerly of Bellowhead, and creator of the Folk Song a Day project). The song appears on his new album Afterglow (2017), which is terrific.

The star-filled art today is, of course, by Jeannie Tomanek, who is based in Marietta, Georgia.

"I paint," she says, "to explore the significance of ideas, memories, events, feelings, dreams and images that seem to demand my closer attention. Some of the themes I investigate emerge first in the poems I write. Literature, folktales, and myths often inspire my exploration of the feminine archetype. My figures often bear the scars and imperfections, that, to me, characterize the struggle to become."

To learn more about the artist, go here. To view a photo-essay of her workspace, go . To see more of Jeannie's work, please visit her website, or seek out her book, Everywoman Art.

February 28, 2019

Honoring the wild

"I believe we need wilderness in order to be more complete human beings, to not be fearful of the animals that we are, an animal who bows to the incomparable power of natural forces when standing on the north rim of the Grand Canyon, an animal who understands a sense of humility when watching a grizzly overturn a stump with its front paw to forage for grubs in the lodgepole pines of the northern Rockies, an animal who weeps over the sheer beauty of migrating cranes above the Bosque del Apache in November, an animal who is not afraid to cry with delight in the middle of a midnight swim in a phospherescent tide, an animal who has not forgotten what it means to pray before the unfurled blossom of the sacred datura, remembering the source of all true visions.''

- Terry Tempest Williams ("A Prayer for a Wild Millennium," Red)

"Caught up in a mass of abstractions, our attention hypnotized by a host of human-made technologies that only reflect us back to ourselves, it is all too easy for us to forget our carnal inherence in a more-than-human matrix of sensations and sensibilities. Our bodies have formed themselves in delicate reciprocity with the manifold textures, sounds, and shapes of an animate earth -- our eyes have evolved in subtle interaction with other eyes, as our ears are attuned by their very structure to the howling of wolves and the honking of geese. To shut ourselves off from these other voices, to continue by our lifestyles to condemn these other sensibilities to the oblivion of extinction, is to rob our own senses of their integrity, and to rob our minds of their coherence. We are human only in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human."

- David Abram (The Spell of the Sensuous)

"What we need, all of us who go on two legs, is to reimagine our place in creation. We need to enlarge our conscience so as to bear, moment by moment, a regard for the integrity and bounty of the earth. There can be no sanctuaries unless we regain a deep sense of the sacred, no refuges unless we feel a reverence for the land, for soil and stone, water and air, and for all that lives. We must find the desire, the courage, the vision to live sanely, to live considerately, and we can only do that together, calling out and listening, listening and calling out."

- Scott Russell Sanders (Writing from the Center

"The wild. I have drunk it, deep and raw, and heard it's primal, unforgettable roar. We know it in our dreams, when our mind is off the leash, running wild. 'Outwardly, the equivalent of the unconscious is the wilderness: both of these terms meet, one step even further on, as one,' wrote Gary Snyder. 'It is in vain to dream of a wildness distinct from ourselves. There is none such,' wrote Thoreau. 'It is the bog in our brains and bowls, the primitive vigor of Nature in us, that inspires the dream.'

"And as dreams are essential to the psyche, wildness is to life.

"We are animal in our blood and in our skin. We were not born for pavements and escalators but for thunder and mud. More. We are animal not only in body but in spirit. Our minds are the minds of wild animals. Artists, who remember their wildness better than most, are animal artists, lifting their heads to sniff a quick wild scent in the air, and they know it unmistakably, they know the tug of wildness to be followed through your life is buckled by that strange and absolute obedience. ('You must have chaos in your soul to give birth to a dancing star,' wrote Nietzsche.) Children know it as magic and timeless play. Shamans of all sorts and inveterate misbehavers know it; those who cannot trammel themselves into a sensible job and life in the suburbs know it.

"What is wild cannot be bought or sold, borrowed or copied. It is. Unmistakeable, unforgettable, unshamable, elemental as earth and ice, water, fire and air, a quitessence, pure spirit, resolving into no contituents. Don't waste your wildness: it is precious and necessary."

- Jay Griffiths (Wild)

The imagery today is by Hib Sabin, an American artist based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Born in 1935, Sabin received a BFA in Art and Art History from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, worked with peace groups in Russian and Uzbekistan, and studied shamanism with indigenous peoples in Mexico, Tanzinia, Australia, and the American West. Working primarily in juniper wood, he carves totemic sculptures, masks, spirit bowls, and canoes inspired by world-wide mythology expressing the depth of the interconnection between the human, animal, and spirit realms. The titles of the works presented here can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

"My goal," he says, "is not to recreate a mythology, but bring past and present together in a multi-dimensional form that speaks to its mystery. What is the spirit of a bird and the power within it? To convey this artistically is to bring the physical and spiritual together in a carving that has power. What is the essence of this power and what does it mean to connect with it in the most primitive, archetypal sense? For the answer to this I turn to the mythologies of the world, for it is they that have the potential to divulge the mystery of these immortal characters."

Go here to see the online catalog of his 2017 exhibition, The Long Game, as well as catalogs of previous shows.

The passages above are from Red: Passion and Patience in the Desert by Terry Tempest Williams (Vintage, 2002 ), The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception & Language in More-Than-Human World by David Abram (Vintage, 1997), Writing from the Center by Scott Russell Sanders (Indiana University Press, 1995), and Wild: An Elemental Journey by Jay Griffiths (Hamish Hamilton, 2007) -- all of which are highly recommended. All rights to the text and art above are reserved by the authors and artist.

A few related posts: Keeping the World Alive, Making Sense of the More-Than-Human World, The Blessings of Otters, Wild Neighbors., The Speech of Animals, and On Animals & the Human Spirit,

Standing our ground

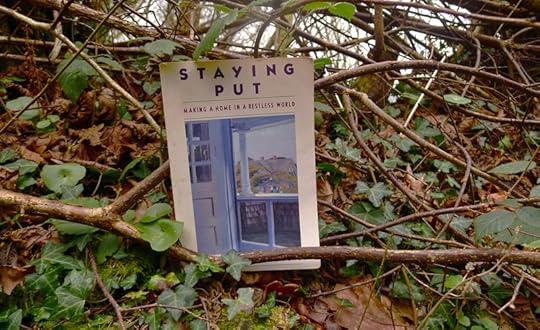

From Staying Put: Making a Home in a Restless World by Scott Russell Sanders:

"My friend Richard, who wears a white collar to his job, recently bought forty acres of land that had been worn out by the standard local regimen of chemicals and corn. Evenings and weekends, he has set about restoring the soil by spreading manure, planting clover and rye, and filling the eroded gullies with brush. His pond has gathered geese, his young orchard has tempted deer, and his nesting boxes have attracted swallows and bluebirds. Now he is preparing a field for the wildflowers and prairie grasses that once flourished here. Having contemplated this work since he was a boy, Richard will not be chased away by fashions or dollars or tornadoes. On a recent trip he was distracted from the book he was reading by thoughts of renewing the land. So he sketched on the flyleaf a plan of labor for the next ten years....

"I think about Richard's ten-year vision when I read a report chronicling the habits of computer users who, apparently, grow impatient if they have to wait more than a second for their machine to respond. I use a computer, but I am wary of the haste it encourages. Few answers that matter will come to us in a second; some of the most vital answers will not come in a decade, or a century.

"When the chiefs of the Iroquois nation sit in council, they are sworn to consider how their decisions will affect their descendants seven generations into the future. Seven generations! Imagine our politicians thinking beyond the next opinion poll, beyond the next election, beyond their own lifetimes, two centuries ahead. Imagine our bankers, our corporate executives, our advertising moguls weighing their judgements on that scale. Looking seven generations into the future, could a developer pave another farm? Could a farmer spray another pound of poison? Could the captain of an oil tanker flush his tanks at sea? Could you or I write checks and throw switches without a much greater concern for what is bought and sold, what is burned?

"As I write this, I hear the snarl of earthmovers and chain saws a mile away destroying a farm to make way for another shopping strip. I would rather hear a tornado, whose damage can be undone. The elderly woman who owned the farm had it listed in the National Register, then willed it to her daughters on condition they preserve it. After her death, the daughters, who live out of state, had the will broken, so the land could be turned over to the chain saws and earthmovers. The machines work around the clock. Their noise wakes me at midnight, at three in the morning, at dawn. The roaring abrades my dreams. The sound is a reminder that we are living in the midst of a holocaust. I do not use the word lightly. The earth is being pillaged, and every one of us, willingly or grudgingly, is taking part. We ask how sensible, educated, supposedly moral people could have tolerated slavery or the slaughter of Jews. Similar questions will be asked about us by our descendants, to whom we bequeath an impoverished planet. They will demand to know how we could have been party to such waste and ruin. They will have good reason to curse our memory.

"What does it mean to be alive in an era when the earth is being devoured, and in a country that has set the pattern for that devouring? What are we called to do?

"I think we are called to the work of healing, both inner and outer: healing of the mind through a change in consciousness, healing of the earth through a change in our lives. We can begin the work by learning how to abide in a place. I am talking about an active commitment, not passive lingering. If you stay with a husband or wife out of laziness rather than love, that is inertia, not marriage. If you stay put through cowardice rather than conviction, you will have no strength to act. Strength comes, healing comes, from aligning yourself with the grain of your place and answering its needs....

"In belonging to a landscape, one feels a rightness, at-homeness, a knitting of self and the world. This condition of clarity and focus, this being fully present, is akin to what the Buddhists call mindfulness, what Christian contemplatives refer to as recollection, what Quakers call centering down. I am suspicious of any philosophy that would separate this-worldly from other-worldly commitment. There is only one world, and we participate in it here and now, in our flesh and our place."

Words: The passage above is from "Settling Down," published in Staying Put: Making a Home in a Restless World by Scott Russell Sanders (Beacon Press, 1993). The poem in the picture captions is from The Woman Who Fell from the Sky by Native America poet Joy Harjo (WW Norton & Co., 1994). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The waterfall on our hill, swollen with winter rain.

A few related posts: Down by the Riverside, The Dance of Joy and Grief, The Landscape of Story, and, from a slightly different slant, On Loss and Transfiguration.

February 27, 2019

Chasing mystery

From "Ground Notes" by Scott Russell Sanders:

"Once when my father was studying a handful of dirt, I asked him if he had ever been lost. 'No,' he answered, 'but there's been a few times when I didn't know where anything else was.' By that definition, I am lost for days and weeks at a stretch, aware of myself but of little else. The only ground I notice is the grit under my shoes. The world is grey cardboard. I trudge through dullness, as though in a deep trench, wholly absorbed in taking the next step. Chores, chores, chores. Places to go, things to do.

"Then occasionally I wake up from my drowse and for a few minutes every toad becomes a dragon, every lilac is a fiery fountain, and I am walking on pure light.

"These luminous moments are the standards by which I measure my ordinary hours. It may be the oldest human standard, older than the desire for comfort, older than duty. As the maverick monk Thomas Berry put it in his stiff but dignified way: 'Awareness of an all-pervading mysterious energy articulated in the infinite variety of natural phenomena seems to be the primordial experience of human consciousness.' Energy is a word that scientists willingly use, but mystery is not. Let mystery into the discussion, they fear, and pretty soon you'll have astral travel and bloodletting and witch hunts; you'll be reading the future in the bones of birds. You'll lock up Galileo for saying the earth spins around the sun. You'll hoot at Darwin for tracing our descent from the apes.

"Cosmologists have tried every which way they can to avoid having to posit what they call 'initial conditions' -- those conditions that determine the features of our universe. Why, for example, does the electron have that charge? Why does energy convert to matter and matter to energy? Why do fundemental forces interact just so? Why does nature obey these rules, or any rules? Why are the parameters such that life could evolve, and, within life, conciousness? And how does it happen that conciousness has figured out so many of the rules?

"If you admit that you cannot answe those questions and simply appeal to initial conditions in order to explain the founding features of the universe, then you raise the question of how those conditions were set. You bump into the old conundrum: How can there be a design without a designer? You can't do physics on God. So cosmologists have proposed a steady-state universe, an oscillating universe, or a universe with zero net energy sprung from quantum fluctuations, anything to avoid having to concede that reality extends beyond the reach of science.

"With our twin hands, our paired eyes, our sense of split between body and mind, we favor dualism: design and designer, creation and creator, universe and God. But I suspect the doubleness is an illusion. 'How can we know the dancer from the dance?' Yeats asked in his poem "Among School Children." We hear treble and bass because we have two ears; the music itself is whole and undivided. The wind and the leaves shaking on the tree are two things; but the wave and the sea are one. When I sit on the pink granite of the Maine coast, stone and soul rubbed smooth by the strike of water, I see the ocean ripple and surge into whitecaps. Just so, the earth is a wave lifted up from the surf of space, and you and I are waves lifted up from earth.

"According to Hopi myth, long ago, at the beginning of our age, people emerged from a hole in the ground. They looked over the earth and liked what they saw, so they stayed. But at the end of time the people will go back again into the ground. When buried in graves of scattered as ashes, we also return to the ground. The throwing of the first shoveful of dirt on the coffin or the flinging of ash into the wind is a ritual moment when the earth reclaims us. Writing about the ground is in part my attempt to come to terms with death, with my own return to the source. But it is at least as much attempt to come to terms with life, with the issuing-forth.

"This is the light in which I have come to see Thoreau's best known sentence: 'The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the world.' Wildness here is usually understood to mean wilderness. But I think it has a larger meaning. I think it refers to the creative energy that continually throws new forms into existence and gives them shape. Thus Wildness is literally the 'preservation of the world,' because without it there would be no world. Gary Snyder may have had some such notion in mind when he insisted in The Practice of the Wild that nature is simply what is, the way of things: 'This, thusness, is the nature of the nature of nature. The wild in the wild.' By keeping in touch with wilderness, we preserve our sanity and world's health.

"Beneath or behind or within everything there is an unfathomable ground -- a suchness, as the Buddhists say -- that one can point to, bow to, contemplate, but cannot grasp. To speak of this ground as a mystery is not to say we know nothing, only that we cannot know everything. The larger the context we envision, the more tentative and partial our knowledge appears, the more humble we are forced to be. Merely think of the earth as a living organism, taking the health of this great body as the gauge of everything we do, and you recognize our ignorance is profound.

"The thawing of the eath brings me a whiff of the world's renewal. The green shoots of crocuses breaking through are the perennial thrusting-forth shapeliness out of the void. Breathing in the breath of soil, I feel the force of Thomas Berry's claim that 'Our deepest convictions arise in this contact of the human soul with some ultimate mystery whence the universe itself is derived.' The smell brings to my lips the words my Mississippi grandfather used to say about anything that delighted him: 'That suits me down to the ground.' "

Words: The passage above is from "Ground Notes," published in Staying Put: Making a Home in a Restless World by Scott Russell Sanders (Beacon Press, 1993); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: On the hillside behind my studio, in the pause between winter and spring. The photograph of me and Tilly was taken by our friend and village neighbor Jim Fortey, whom we happened to meet during woodland wanderings.

February 26, 2019

Chasing beauty

From "Beauty" by Scott Russell Sanders:

"As far back as I can remember, things seen or heard or smelled, things tasted or touched, have provoked in me an answering vibration. The stimulus might be the sheen of moonlight on the needles of a white pine, or the iridescent glimmer on a dragonfly's tail, or the lean silhouette of a ladder-back chair, or the glaze on a hand-thrown pot. It might be bird-song or a Bach sonata or the purl of water over stone. It might be a line of poetry, the outline of a cheek, the savor of bread, the sway of a bough or a bow. The provocation might be as grand as a mountain sunrise or as humble as an icicle's jeweled tip, yet in each case a familiar surge of gratitude and wonder swells up in me.

"As far back as I can remember, things seen or heard or smelled, things tasted or touched, have provoked in me an answering vibration. The stimulus might be the sheen of moonlight on the needles of a white pine, or the iridescent glimmer on a dragonfly's tail, or the lean silhouette of a ladder-back chair, or the glaze on a hand-thrown pot. It might be bird-song or a Bach sonata or the purl of water over stone. It might be a line of poetry, the outline of a cheek, the savor of bread, the sway of a bough or a bow. The provocation might be as grand as a mountain sunrise or as humble as an icicle's jeweled tip, yet in each case a familiar surge of gratitude and wonder swells up in me.

"Now and again some voice raised on the stairs leading to my study, some passage of music, some noise from the street, will stir a sympathetic hum from the strings of the guitar that tilts against the wall behind my door. Just so, over and over again, impulses from the world stir a responsive chord in me -- not just any chord, but a particular one, combining notes of elegance, exhileration, simplicity, and awe. The feeling is as recognizable to me, as unmistakable, as the sound of my wife's voice or the beating of my own heart. A screech owl calls, a comet streaks the night sky, a story moves unerringly to a close, a child lays an arrowhead in the palm of my hand, my daughter smiles at me through her bridal veil, and I feel for a moment at peace, in place, content. I sense in those momentary encounters a harmony between myself and whatever I behold. The word that seems to fit most exactly this feeling of resonance, this sympathetic vibration between inside and outside, is beauty.

"What am I to make of this resonant feeling? Do my sensory thrills tell me anything about the world? Does beauty reveal a kinship between my small self and the great cosmos, or does my desire for meaning only fool me into thinking so? Perhaps, as biologists maintain, in my response to patterns I am merely obeying the old habits of evolution. Perhaps, like my guitar, I am only a sounding box played on by random forces.

"I must admit that two cautionary sayings keep echoing in my head. Beauty is only skin deep, I've heard repeatedly, and beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Appealing surfaces may hide ugliness, true enough, as many a handsome villain or femme fatale should remind us. The prettiest of butterflies and mushrooms and frogs include some of the most poisonous ones. It's equally true that our taste may be influenced by our upbringing, by training, by cultural fashion. One of my neighbors plants in his yard a pink flamingo made of translucent plastic and a concrete goose dressed in overalls, while I plant my yard in oxeye daisies and jack-in-the-pulpits and maidenhair ferns, and both of us, by our own lights, are chasing beauty.

"Must beauty be shallow if it can be painted on? Musn't beauty be a delusion if it can blink on and off like a flickering bulb? I'll grant that we may be fooled by facades, led astray by our fickle eyes. But I've been married now for thirty years. I've watched my daughter grow for twenty-four years, my son for twenty, and these loved ones have taught me a more hopeful possibility. Season after season I've knealt over fiddleheads breaking ground, studied the wings of swallowtails nectaring on blooms, spied skeins of geese high in the sky. There are books I've read, pieces of music I've listened to, ideas I've revisited time and again with fresh delight. Having lived among people and places and works of imagination whose beauty runs all the way through, I feel certain that genuine beauty is more than skin deep, that real beauty dwells not in my eye alone but in the world.

"While I can speak with confidence of what I feel in the presence of beauty, I must go out on a speculative limb if I'm to speak about the qualities of the world that call it forth. Far out on that limb, therefore, let me suggest that a creature, an action, a landscape, a line of poetry or music, a scientific formula, or anything else that might seem beautiful, seems so because it gives us a glimpse of the underlying order of things. The swirl of a galaxy and the swirl of a [human-made object of beauty] resemble each other not merely by accident, but because they follow the grain of the universe. The grain runs through our own depths. What we find beautiful accords with our most profound sense of how things ought to be.

"Ordinarily we live in a tension between our perceptions and our desires. When we encounter beauty, that tension vanishes, and outward and inward images agree....

"As far back as we can trace our ancestors, we find evidence of a passion for design -- decorations on pots, beads on clothing, pigments on the ceilings of caves. Bone flutes have been found at human sites dating back more than 30,000 years. So we answer the breathing of the land with our own measured breath; we answer the beauty we find with the beauty we make. Our ears may be finely tuned for detecting the movements of predators or prey, but that does not explain why we should be so moved by listening to Gregorian chants or Delta blues. Our eyes may be those of a slightly reformed ape, trained for noticing whatever will keep skin and bones intact, but that scarely explains why we should be so enthralled by the lines of a Shaker chair or a Durer engraving, or by the photographs of Jupiter."

"I am convined there's more to beauty than biology, more than cultural convention. It flows around and through us in such abundance, and in such myriad forms, as to exceed by a wide margin any mere evolutionary need. Which is not to say that beauty has nothing to do with survival; I think it has everything to do with survival. Beauty feeds us from the same source that created us. It reminds us of the shaping power that reaches through the flower stem and through our own hands. It restores our faith in the generosity of nature. By giving us a taste of the kindship between our small minds and the great mind of the Cosmos, beauty assures us that we are exactly and wonderfully made for life on this glorious planet, in this magnificent universe. I find in that affinity a profound source of meaning and hope. A universe so prodigal of beauty may actually need us to notice and respond, may need our sharp eyes and brimming hearts and teaming minds, in order to close the circuits of Creation."

Words: The three passages above are from "Beauty," an essay by Scott Russell Sanders (Orion Magazine, 1998). The poem in the picture captions is from Thirst by Mary Oliver (Beacon Press, 2007). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The beauty of wild ponies. encountered this morning on our hill.

February 25, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm back in the studio at last after three weeks of flu, moving slowly still, but very glad to be here. Let's start the week with songs of the sea: of sailors and selkies and all those who wait on the shore....

Above: "Forfarashire" by London-based singer Kirsty Merryn, with Steve Knightley (from Show of Hands). The song -- which appeared on Merryn's first album, She & I (2017) -- tells the story of Grace Darling, the daughter of a lighthouse-keeper, who rescued survivors from the wreck of a paddlesteamer

Below: "Shipping Song" by Lisa Knapp, also based on London. This piece, woven from the language of the Shipping Forecast (the daily radio broadcast of weather reports for the seas off the British coast), appeared on Knapp's second album, Hidden Seam (2013).

Above: "The Call/Daughters of Watchet/Caturn's Night" by Ange Hardy and Lukas Drinkwater, based in Somerset and Devon. Watchet is a harbour town on the Somerset coast, its history bound up with fishing, farming, and mining. The song can be found on their joint album Findings (2017).

Below: "The Golden Vanity" (Child Ballad #286) performed by Iona Fyfe, from Aberdeenshire, Scotland. The song appears on her latest album, Dark Turn of Mind (2018).

Above: a gorgeous version of "The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry" (Child Ballad #113) sung by Julie Fowlis, from the Scottish Hebrides, with the The Unthanks from Northumbria.

Below: another version of the same ballad performed by English folksinger Maz O'Connor, who grew up in the Lake District. The song appears on her second album, This Willowed Light (2014). The video was filmed by a member of The Icicle Divers Sub Aqua Club, based in Crewe.

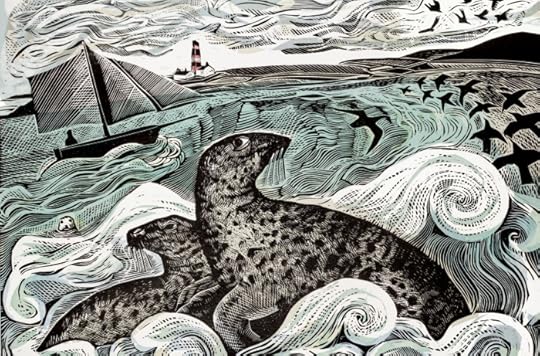

The art today is by printmaker and painter Angela Harding, from Rutland, in the East Midlands of England. "For the past 10 years," she says, "I have worked solely at my art practice in the village of Wing -- which is very apt for a women inspired by birds. My studio is at the bottom of the garden and houses all I need to make my work, including a recently acquired Rochat Albion press. The studio overlooks sheep fields surrounded by gentle sloping hills. It���s not a dramatic landscape but somehow a comforting one and to me feels very much like home. The Rutland countryside does have a wealth of animal and bird life that is a constant inspiration for my work. Rutland Water is just over the ridge which attracts a great diversity of bird life that is world renowned."

To see more of her beautiful work, please visit her website and online shop.

Art above: "Gannets at Rathlin Island," and details from "Seal Song" and "Black Throated Diver." All rights reserved by Angela Harding.

February 14, 2019

Vissi d'arte, vissi d'amore

I apologize for being gone so long; I'm still recovering from a very tenacious flu. I am longing to be back in the studio, back in the hills, and back here with you all. I hope it will be soon.

Magic healing quilt by Karen Meisner.

February 6, 2019

Myth & Moor update

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers