Terri Windling's Blog, page 69

November 17, 2018

An invitation from the fairies

Please join us on Monday night (UK time) to see what the Modern Fairies interdisciplinary art project has been up to.

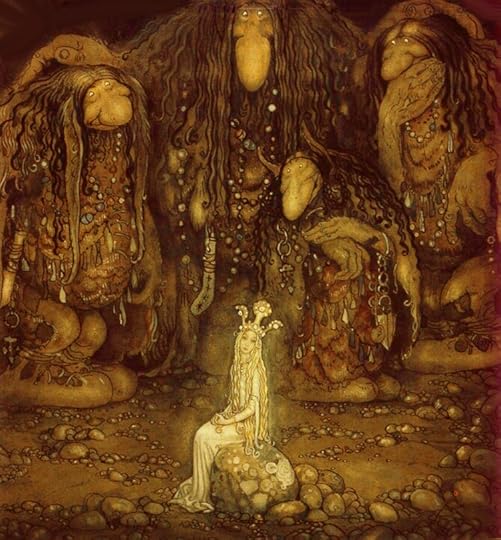

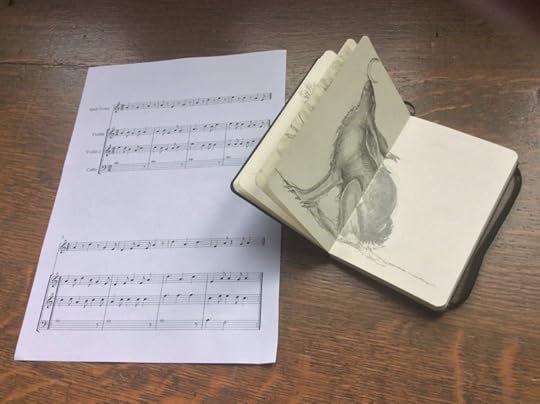

The paintings above are by John Bauer (1882-1918 ) and John Anster "Fairy" Fitzgerald (1819-1906). The sketchbook drawing is by Jackie Morris, for Fay Hield'a song-in-progress, "I Shall Go Into a Hare."

The Modern Fairies website & blog is here. My posts about the project are here and here.

November 16, 2018

On loss and transfiguration

"The classic makers of children's literature," writes Alison Lurie, "are not usually men and women who had consistently happy childhoods -- or even consistently unhappy ones. Rather they are those whose early happiness ended suddenly and often disastrously. Characteristically, they lost one or both parents early. They were abruptly shunted from one home to another, like Louisa May Alcott, Kenneth Grahame, and Mark Twain -- or even, like Frances Hodgson Burnett, E. Nesbit, and J.R.R. Tolkien, from one country to another. L. Frank Baum and Lewis Carroll were sent away to harsh and bullying schools; Rudyard Kipling was taken from India to England by his affectionate but ill-advised parents and left in the care of stupid and brutal strangers. Cheated of their full share of childhood, these men and women later re-created, and transfigured, their lost worlds. "

J.M Barrie falls into this catagory, the happiness of his early childhood vanishing into darkness and gloom when an elder brother, the family favorite, died in a skating accident, after which Barrie's mother retreated permanently to her bed. C.S. Lewis was ten when he lost his mother to cancer (and just four when his beloved dog, Jacksie, was killed by a car -- a loss that so effected him that he insisted upon being called Jack for the rest of his life). George MacDonald lost his mother to tuberculosis at the age of eight. Enid Blyton's happy childhood in Kent ended  abruptly when her beloved father left the family for another woman, leaving Enid behind with a mother who disapproved of her interest in nature, literature, and art.

abruptly when her beloved father left the family for another woman, leaving Enid behind with a mother who disapproved of her interest in nature, literature, and art.

The sudden loss of a happier childhood world doesn't turn everyone into a children's book writer, of course, but it's interesting to note how many fine writers' backgrounds are marked by such loss; and Lurie may be correct that the desire to re-create the lost world lies at the heart of a particular form of creative inspiration. Or perhaps I'm just struck by Lurie's idea because it maps onto my own childhood, which was, from a child's point of view, safe and stable for the first six years when I lived in my grandmother's household (with my teenage mother and her sisters), and then plunged into darkness upon my mother's marriage to a brutal man, a stranger to me until the day of the wedding. Loss of home at a tender age can indeed send an unhappy child inward, seeking lands in imagination uncorrupted by the treacherous adult world.

In many previous posts (such as this and this), we've taked about concepts of home, place, connection to the landscape, and the way these things influence our creative work. In yesterday's post, we looked at longing -- for a lost home, a lost world, a lost way of life -- as a frequent theme in fantasy fiction. But loss can come about in so many different ways, and needn't be dramatic to cause lasting trauma. I'm thinking, for example, of a loss all too common today in our over-populated world: the loss of treasured chilhood landscapes to the unchecked sprawl of cities and suburbs, of beloved old houses and places we can never return to, buried under shopping malls and parking lots.

In her essay collection Language and Longing, Carolyn Servid writes poignantly of her husband's childhood in an isolated valley in the mountains of Colorado. Lightly populated by old ranching families, artists, and hermits, the valley was a sanctuary for humans and animals alike...until the development of the nearby  town of Aspen into a ski resort and playground for the wealthy began to raise property prices on Aspen's periphery. When the dirt road into the valley was paved, change was not long behind: land speculation, housing developments, a golf course. The valley as generations had known and loved it was gone.

town of Aspen into a ski resort and playground for the wealthy began to raise property prices on Aspen's periphery. When the dirt road into the valley was paved, change was not long behind: land speculation, housing developments, a golf course. The valley as generations had known and loved it was gone.

Servid writes that her husband "had witnessed this gradual transformation during summers home from college. He witnessed more changes every time he visited after marriage and various jobs took him out of the valley. He chronicled those changes to me before he ever drove me up the Crystal River Road to the Redstone house. The landscape stunned me the first time I saw it, and I watched it bring a deep smile of recognition to Dorik's eyes, but I knew his memories were of a wholeness that was no longer there. I realized he held a kind of perspective and knowledge that has been lost over and over again in the settlement of the continent, over and over again in the civilzation of the world."

A little later, he learns that a neighbor's ranch has been sold off to a developer. "I watched his face tighten," Servid writes, "and knew that a deepening ache was filling him. Places and people he loved were both caught in the wake of rampant development that grew like a cancer. The impact was like a diagnosis of the disease itself, as though one of the most fundamental aspects of his life was being eaten away. I wondered then about the grief that comes to us when we lose the places we love. This grief doesn't have much standing among the range of emotions that our society values. We have yet to fully acknowledge and accept just how much our hearts are entwined with the places that shape us, tolerate us, hold us, provide for us. We have yet to openly testify and accede to the necessity of such places and love of them in our daily lives. We have yet to fully understand that our links as people living together in communties will never be more than transient and vulnerable without rootedness in the place itself."

Just as Servid wonders "about the grief that comes to us when we lose the places we love," I wonder about the ways such a loss impacts us as writers and artists. Grief is a powerful thing, and especially so when it rumbles away, unexpressed, in the depth of our souls, the quiet but constant base note of our lives. Grief for landscapes paved over, ways of life that are gone, for whole species that are rapidly vanishing around us. Grief can indeed be a spur to art, leading us to "re-create or transfigure" our cherished lost worlds, or it can do the reverse: deaden and silence and paralyze us.

Your thoughts?

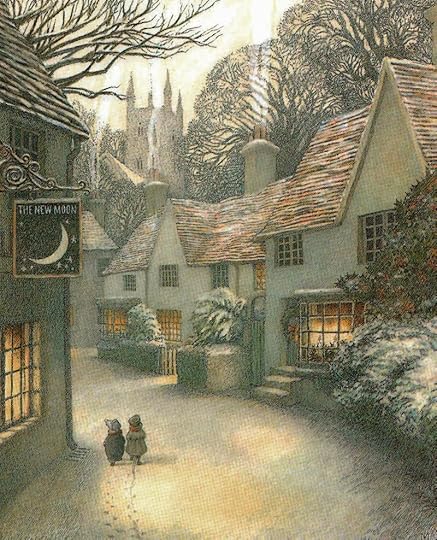

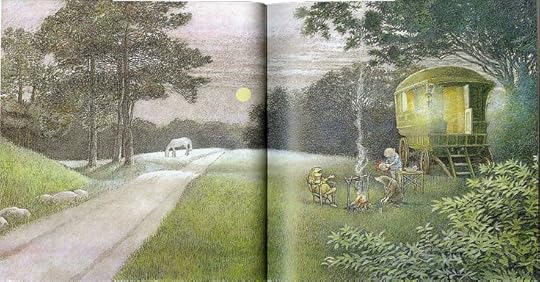

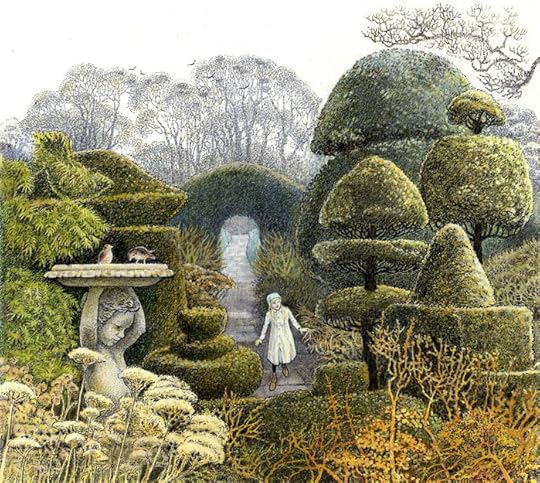

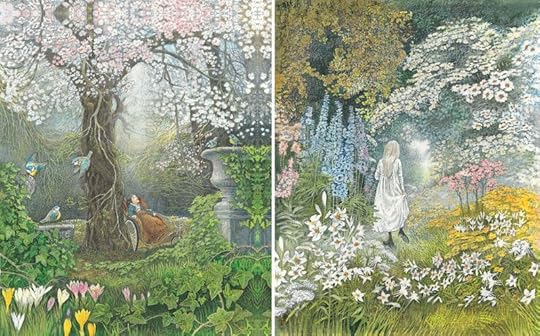

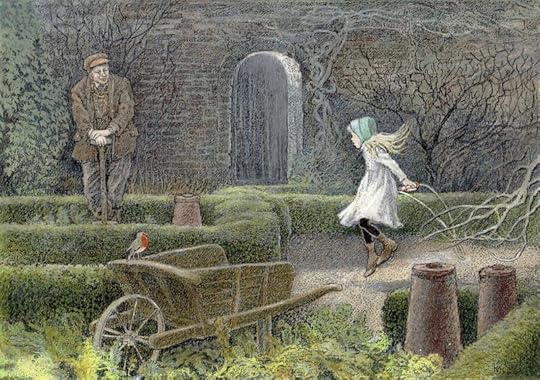

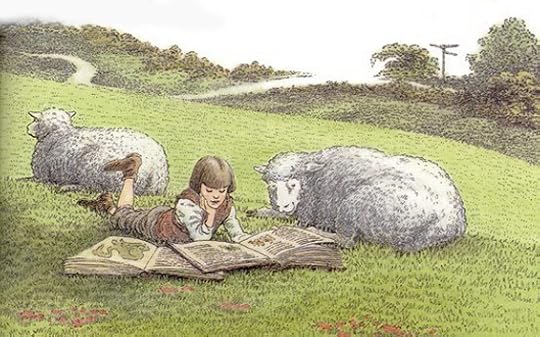

The art today is by Inga Moore, who was born in Sussex, raised in Australia (from the age of eight), and returned to England when she reached adulthood. Joanna Carey, in her lovely portrait of the artist, writes:

"An imaginative, somewhat subversive child, she drew constantly, illustrating not just her own stories but also her schoolbooks, her homework, tests and exam papers. 'If you'd only stop all this silly drawing,' said the Latin teacher, 'you might one day amount to something.' She did stop -- 'for a long time' -- and is still resentful about that teacher's attitude. She regrets not going to art school, and endured 'one boring job after another' before eventually getting back to the drawing board. Supporting herself making maps for a groundwater company, she embarked on a series of landscapes and happily rediscovered her passion for drawing."

"An imaginative, somewhat subversive child, she drew constantly, illustrating not just her own stories but also her schoolbooks, her homework, tests and exam papers. 'If you'd only stop all this silly drawing,' said the Latin teacher, 'you might one day amount to something.' She did stop -- 'for a long time' -- and is still resentful about that teacher's attitude. She regrets not going to art school, and endured 'one boring job after another' before eventually getting back to the drawing board. Supporting herself making maps for a groundwater company, she embarked on a series of landscapes and happily rediscovered her passion for drawing."

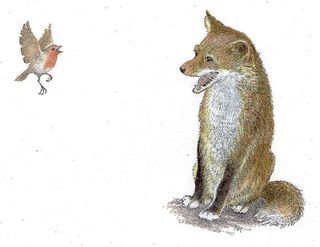

Moore worked as an illustrator in London until the economic downturn caused her to lose her home there -- a fortunate loss, as it turns out. She relocated to the Gloucester countryside, discovered this corner of England to be her heart's home, and produced the remarkable illustrations for The Wind in the Willows and The Secret Garden for which she is now justly famed. The pictures above are from those two volumes; the picture below is from The Reluctant Dragon.

The passage by Alison Lurie is from Don't Tell the Grown-ups: Subversive Children's Literature (Little, Brown Publishers, 1990). The passage by Carolyn Servid is from Of Language and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge (Milkweed Editions, 2000). The quote by Joanna Carey is from "Inga Moore, illustrator of The Wind in the Willows" ( The Guardian, Feburary 6, 2010). All rights to the text and art above reserved by their creators. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor three years ago, and relates to yesterday's post on "longing" in fantasy fiction.

The passage by Alison Lurie is from Don't Tell the Grown-ups: Subversive Children's Literature (Little, Brown Publishers, 1990). The passage by Carolyn Servid is from Of Language and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge (Milkweed Editions, 2000). The quote by Joanna Carey is from "Inga Moore, illustrator of The Wind in the Willows" ( The Guardian, Feburary 6, 2010). All rights to the text and art above reserved by their creators. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor three years ago, and relates to yesterday's post on "longing" in fantasy fiction.

November 15, 2018

Longing for a better world

From an interview with Lev Grossman (author of The Magician trilogy), in which he is asked for his definition of fantasy literature:

"My working definition? Any book with magic in it. It���s crude but effective. It helps if you take the long view, historically speaking, because it���s not like J.R.R. Tolkien invented fantasy with The Hobbit. Take a giant step back and you can���t help but notice that the greater part of all human literature is fantasy, in the sense that it has monsters and magic and things like that in it. Shakespeare is infested with ghosts and spirits and witches. Look at Spenser. Look at Dante. Look at Ovid, or Homer. Go back past the 18th century and practically everything could be called fantasy.

"It���s only relatively recently, at the start of the 18th century, that you see the arrival and dizzying ascent of what we might broadly call realism. Suddenly, around about Robinson Crusoe or so, Western culture was seized by this powerful idea that literature was supposed to resemble real life, and fictional worlds were supposed to behave like the real world, as it was coming to be understood by scientists, and anything that didn���t do so wasn���t literature. Magic and the supernatural were exiled to other, lesser categories: Gothic fiction, fairy tales, ghost stories, children���s books, fantasy. A lot of people still think it belongs there."

"There is a specific modern tradition of fantasy fiction," he clarifies, "that starts in the 1920s and 1930s in England and America with writers like Lord Dunsany and Hope Mirrlees, and which really takes off with C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, as well as T.H. White and Robert E. Howard....That generation -- the ones who were writing in the 1920s and '30s -- had been the victim of a historical trauma: They bore witness to a period of catastrophic social and technological change. The Victorian world of their childhood was shattered and swept away by the 'advances' of the early 20th century -- the electrification of cities, the rise of mass media, the replacement of horses by cars, the rise of psychoanalysis, the invention of mechanised warfare. As a result, the world that they found themselves in as adults was virtually unrecognisable to them.

"Some of those writers responded to this cataclysm by creating strange, fragmented masterpieces that we now know as literary modernism: Joyce, Hemingway, Kafka, Woolf, Faulkner and so on. Gertrude Stein famously called them the Lost Generation, and she wasn���t wrong. But other writers -- like Lewis and Tolkien, who were both veterans of the Somme -- wrote fantasy instead. They used it as a way to express their sense of longing for a lost world, an idyllic, more grounded, more organic, more connected world that they would never see again. They were part of the Lost Generation too."

Returning to these ideas in his essay "What is Fantasy About?," Lev notes that "longing" is a prominent theme in fantasy: the longing for a lost world, or a better one.

"Lewis and Tolkien were virtuosos of longing," he writes. "They had, after all, lost a world, the world of their Victorian childhoods....They lived through, if not a singularity, then a pretty serious historical inflection point, and they longed for that pre-inflected world. (Laura Miller writes about this really compellingly, albeit somewhat differently, in The Magician���s Book, her excellent book about Narnia. She quotes Lewis on his special notion of Joy: 'an unsatisfied desire that is itself more desirable than another satisfaction.')

"We too have lived through an inflection point: a great deal of technological and social change. We can lay claim to a certain amount of longing.

"Longing for what exactly? A different kind of world. A world that makes more sense -- not logical sense, but psychological sense. We���re surrounded by objects that we don���t understand. Like iPods -- they���re typical. They���re gorgeous, but they���re also really alienating. You can���t open them. You can���t hack them. You don���t even really know how they work, or how they���re made, or who made them. Their form is abstractly beautiful, but it has nothing to do with their function. We really like them, but it���s somehow not a liking that makes us feel especially good.

"The worlds that fantasy depicts are very different from that. They tend to be rural and low-tech. The people in a fantasy world tend to be connected to it -- they understand it, they belong in it. People in Narnia don���t long for some other world (except when they long for Aslan���s Land, which I always found unsettling). They���re in sync with it....To be sure, fantasy worlds are often animated by weird mysterious forces -- like magic -- but even those forces on some level come from inside us. They���re not made in China. They express deep human wishes and primal emotions. Likewise the worlds of fantasy are inhabited by demons and monsters, but only because we���re inhabited by monsters, the ones that live in our subconsciouses (subconsci?) Those monsters are grotesque and not-human, and sometimes they even destroy us, but we recognize them instinctively.

"This longing for a world to which we���re connected -- and not connected Zuckerberg-style, but really connected, like a dryad with its tree ��� surfaces in a lot of places these days, not just in fantasy. You see it in the whole crafting movement ��� the Etsy/Makerfaire movement. You see it in the artisanal food movement. And it you see it in fantasy."

For more of Lev Grossman's thoughts on the evolution of fantasy, I recommend "Fear and Loathing in Aslan's Land," the third annual J.R.R Tolkien Lecture on Fantasy Literature at Pembroke College (Tolkien's college), Oxford, in 2015.

Words: The passages above are from "Lev Grossman on Fantasy" ( on Five Books.com) and "What is Fantasy About?" on Lev Grossman's blog (November, 2011). The Lisel Mueller poem in the picture captions was first published in The New Yorker (November, 1967) and also appears in her book Alive Together: New & Selected Poems (Louisiana State University Press, 1996), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The hound has a surprise encounter on Meldon Hill.

November 14, 2018

On writing fantasy

From an interview with Lev Grossman, author of The Magician trilogy:

"I���m not a political writer, particularly, or even at all, but I cannot overstate how much what is happening in this country politically right now has affected what I do as a storyteller. What we all do. The grotesque, violently mendacious way that Trump uses language -- when I write now, I am writing against that. I am watching him trash the tools I use for my art -- words --and I have to take that into account, and work with the damage.

"And this affects fantasy in specific ways. By its nature fantasy focuses on power relationships a lot, whether that power is political or military or magical in nature. You get a lot of monarchies, with the usual abuses. It also deals with outsiders a lot, and the question of who is human and who isn���t, who matters and who doesn���t. These issues have always been important, but right now in this country they are urgent and central."

When asked the usual question about writing in a genre often disregarded by literary critics, Lev responds:

"Literature is truly jurassic in the way that it handles issues of genre and high and low. It���s not just visual media. When your medium is getting lapped by ballet and opera and poetry, you know you are not in the vanguard anymore.

"Why should that be? Fantasy cuts against a lot of the literary values we inherited from the modernists (whom I love). Fantasy is traditionally less about psychological interiority and more about externalizing inner conflicts in symbolic forms. Fantasy is plotty, it runs on heavy narrative rails, whereas the modernists were vigorous critics and disassemblers of narrative architecture.

"Fantasy is also, in its way, quite anti-establishment. It announces its priorities up front: the reality with which we are going to be concerning ourselves is not the reality of your job, or your school, or your government. We are going to be talking about something else. It���s in a lot of people���s interests to marginalize or trivialize that reality."

"I think our project, collectively, as fantasy writers, is to question fantasy���s basic assumptions," he reminds us. "We need to find its blind spots and attack everything that���s sacred to it. The coming of age story. The fatherly mentor. The faithful comic sidekick. The easy moral choices. The more we chip away at the foundations the genre rests on, the stronger it will become. There���s no end to where we can take it. Fantasy may have limitations as a genre, but whenever I���ve thought I���ve found them in the past, somebody has always come along and blown right past them."

Words: The passages above are from interviews on LitHub (January, 2017) and Tor.com (November, 2011). The quotes in the picture captions are from "Why Fantasy Isn't Just for Kids" (The Wall Street Journal, July, 2011). Pictures: A contemplative moment in a field near the studio. Tilly is wearing her shaggy winter coat as the days grow colder.

November 13, 2018

Finding the colors again

"We read fantasy to find the colors again, I think. To taste strong spices, and hear the songs the sirens sang. There is something old and true in fantasy that speaks to something deep within us, to the child who dreamed that one day he would hunt the forests of the night, and feast beneath the hollow hills, and find a love to last forever, somewhere south of Oz, and north of Shangri-La." - George R.R. Martin

"Current cant equates fantasy with escapism, and current fashion would have it that fantasy is both easy to read and to write. It isn't. When it is done honestly, by a skillful writer, fantasy takes us far enough beyond our daily perceptions to open us to the essential realities beneath it. This is the true goal of all art." - Ellen Kushner

"All art, by definition of the word, is fantasy in the broadest sense. The most uncompromisingly (should I say sordidly?) naturalistic novel is still a manipulation of reality. Fantasy, too is a manipulation, a reshaping of reality. There is no essential conflict or contradiction between literary realism and literary fantasy, any more than between science and humanism. Technical details aside, most of the things you can say about fantasy also apply to realism. I suppose you might define realism as fantasy pretending to be true; and fantasy as reality pretending to be a dream." - Lloyd Alexander

"The world of reality has no room for wistful backward-looking; and even if it had, there are no more than a few people who actively retain the desire for [the sense of wonder] known in childhood or have the capacity to evoke it at will. These few, moreover, soon become strangers to their fellows, for they are the incomprehensible ones--the dreamers who take the sky for their skull, the ribs of mountains for their bones, who sense always the faculties of the primitive, and see always with the wondering eye of the child.

"They are the ones who never pass a secret place in the woods without a stare of curiosity; for the mystery implied in all its mounds and hollow, who still turn corners with a lift of expectation at the heart. And to be a writer of fantasy, one must be among those few -- those fortunate few; for, to produce a work that answers all the demands of fantasy, is to suddenly turn the corner which does at last show something strange and wonderful waiting to be seen, and -- most gloriously -- to know that long-ago sense of yearning at last fulfilled." - Mollie Hunter

Words: The poem in the picture captions is from Poetry Magazine (May 2005). All rights to quotes and poem above reserved by the authors. Pictures: a dream of autumn in the little woodland behind the studio.

November 12, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning: trouble & woe

Above: "Trouble and Woe" by singer/songwriter Ruth Moody, from Winnipeg, Canada. The song appeared on her third solo album, These Wilder Things (2013).

Below: "Wayfarin' Stranger," an old American gospel song performed by the Hayde Bluegrass Orchestra, from Oslo, Norway. The song was released as a single last year. The vocalist is Rebekka Nilsson.

Above: "Last Kind Words," written by the great southern blues musician Geeshie Wiley (1908-1950) and sung by the equally great Rhiannon Giddens, from North Carolina. This performance was filmed for A Prairie Home Companion in 2015.

Below: "A Day For The Hunter, A Day For The Prey" by Leyla McCalla, a Haitian-American singer/songwriter based in New Orleans. It appears on her album of the same name, released last year.

Above: "No Hard Feelings" by The Avett Brothers (Scott and Seth Avett, with Bob Crawford on bass and Joe Kwon on cello), from North Carolina. The song appeared on the band's ninth studio album, True Sadness (2016). This performance was filmed for A Prairie Home Companion in 2017. The fiddler is Tania Elizabeth.

Below: "San Luis" by singer/songwriter Gregory Alan Isakov. The song is from his new album, Evening Machines, recorded on his farm near Boulder, Colorado. The video was shot in the Great Sand Dunes National Park and the San Luis Valley of southern Colorado by conservation photographer Andy Mann, with filmmakers Keith Ladzinski and Chris Alstrin.

The art today is by American painter Winslow Homer (1836-1910).

November 7, 2018

Leaning into the light

On the day after the U.S. midterm elections, which brought us both good news and bad, we storytellers just have to keep on going, and keep leaning into the light....

From Linda Hogan's beautiful memoir, The Woman Who Watches Over the World:

"To open our eyes, to see with our inner fire and light, is what saves us. Even if it makes us vulnerable. Opening the eyes is the job of storytellers, witnesses, and the keepers of accounts. The stories we know and tell are reservoirs of light and fire that brighten and illuminate the darkness of human night, the unseen. They throw down a certain slant of light across the floor each morning, and they throw down also its shadow."

"As time has passed," Hogan reflects, "things in me have been burned away and I see my life more clearly, more cleanly, than I had ever seen it before. And in that vision of my past, my history, my body, I also saw that there was something inside me that had survived and not merely survived but had done so whole and nearly intact. The hurt child raises itself and doesn't just walk but swims and flies. This child sees that life may never be easy but may be beautiful...

"Fire, like pain, like love, is a power we do not know. Yet from the ashes of each, something will grow. No one knows if it will be something beautiful and strong. But in our lives it is sometimes the broken vessel, as writer Andre Dubus calls it, that spills the light."

''How is one to live a moral and compassionate existence," asks Barry Lopez, "when one is fully aware of the blood, the horror inherent in life, when one finds darkness not only in one���s culture but within oneself? If there is a stage at which an individual life becomes truly adult, it must be when one grasps the irony in its unfolding and accepts responsibility for a life lived in the midst of such paradox. One must live in the middle of contradiction, because if all contradiction were eliminated at once life would collapse.

''There are simply no answers to some of the great pressing questions. You continue to live them out, making your life a worthy expression of leaning into the light.''

Words: The passages above are from The Woman Who Watches Over the World: A Native Memoir by Linda Hogan (WW Norton, 2001) and Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez (Scribner's, 1986); all rights reserved by the authors. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2014. A related post: "The beauty of brokeness."

Pictures: "Expansion, New York City" by Paige Bradley (U.S.), and light installations by Rune Guneriussen (Norway) and Bruce Munro (U.K.).

November 6, 2018

Hope and faith

I had a post-in-progress planned for you today, but my morning got waylaid by dealing with a family problem. (Not a serious one, don't worry; just time consuming.) This post is from the Myth & Moor archives, but is worth re-visiting on a day when we are all holding our breaths over the American midterm elections.

From Rebecca Solnit's Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities:

"A friend of mine, Jaime Cortez, tells me I should consider the difference between hope and faith. Hope, he says, can be based on the evidence, on the track record of what might be...but faith endures even when there's no way to imagine winning in the foreseeable future. Faith is more mystical. Jaime sees the American Left as pretty devoid of faith, and connects faith to what it takes to change things in the long term, beyond what you might live to see or benefit from. I argue that what was once the Left is now so full of anomalies -- of indigenous intellectuals and Catholic pacifists and the like -- that maybe we do have faith -- some of us.

"Activism isn't reliable. It isn't fast. It isn't direct either, most of the time, even though the term direct action is used for that confrontation in the streets, those encounters involving law breaking and civil disobedience. It may be because activists move like armies through the streets that people imagine effects as direct as armies. An army assaults the physical world and takes physical possession of it; activists reclaim the streets and occasionally seize a Bastille or swarm a Berlin Wall, but the terrain of their action is usually immaterial, the realm of the symbolic, political discourse, collective imagination. They enter the conversation forcefully, but it remains a conversation. Every act is an act of faith, because you don't know what will happen. You just hope and employ whatever wisdom and experience seems most likely to get you there.

"I believe all this," Solnit continues, "because I've lived it, and I've lived it because I am a writer. For twenty years I have sat alone at a desk tinkering with sentences and then sending them out, and for most of my literary life, the difference between throwing something in the trash and publishing it was imperceptible, but in the past several years the work has started coming back to me, or the readers have. Musicians and dancers face their audience and visual artists can spy on them, but reading is mostly as private as writing. Writing is lonely. It's an intimate talk with the dead, with the unborn, with the absent, with strangers, with readers who may never come to be and who, even if they do read you, will do so weeks, years, decades later. An essay, a book, is one statement in a long conversation you could call culture or history; you are answering something or questioning something that may have fallen silent long ago, and the response to your words may come long after you're gone and never reach your ears -- if anyone hears you in the first place....

"You write your books. You scatter your seeds. Rats might eat them, or they might rot. In California, some seeds lie dormant for decades because they only germinate after fire, and sometimes the burned landscape blooms most lavishly. In her book Faith, Sharon Salzberg recounts how she put together a collection of teachings by the Buddhist monk U Pandita and consigned the project to the 'minor good-deed category.' Long afterward, she found out that while Aung San Suu Kyi, the Burmese democracy movement's leader [back in the days when she was a true force for good], was isolated under house arrest by that country's dictators, the book and its instructions in meditation 'became her main source of spiritual support during those intensely difficult years.' Thought becomes action becomes the order of things, but no straight road takes you there.

"Nobody can know the full consequences of their actions, and history is full of small acts that changed the world in surprising ways."

Words: The passage above is from Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit (Haymarket, 2004), which I highly recommend. The poem in the picture captions is from The Crooked Inheritance by Marge Piercy (Knopf, 2006). All rights reserved by the authors. This post first appeared in November 2016, not long after the American presidential election.

Pictures: Black dog, golden leaves, and the colourful funghi community in the Devon woods. My "Bunny Girls" drawing at the end goes out to American friends and family, with special thanks to all who are helping voters get to the polls today.

November 5, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week I'm focused on Child Ballads: on old, old songs performed in new ways, along with a couple of other good pieces rooted in traditional folkways.

Above: "The Fair Flower of Northumberland" (Child Ballad #9) performed by Scottish musician Alasdair Roberts, with Amble Skuse and David McGuinness. The song appears on their strange and remarkable new album, What News. The video, filmed at the University of Glasgow, features performance artist Sg��ire Wood.

Below: "Cruel Mother" (Child Ballad #20) performed by Scottish singer and cellist Fiona Hunter. The song is from her first solo album, Fiona Hunter (2014), with animation by Gavin C. Robinson.

Above: "Abbots Bromley Horn Dance" performed by Stick in the Wheel, from East London. The video, containing archival footage from Abbots Bromley, was directed by Ian Carter, with animation by Teresa Elizabeth Lobos. To learn more about the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance go here. To read about deer in folk ritual and myth, go here and here.

Below: "Over Again" performed by Stick in the Wheel.

Both songs are from their terrific new album, Follow Them True.

Above: "Willie's Lady" (Child Ballad #6) performed by the English folk trio Lady Maisery (Hannah James, Hazel Askew, Rowan Rheingans). It's from their lovely first album, Weave & Spin (2011).

Below: "The Elfin Knight" (Child Ballad #2) performed by folk legend Norma Waterson, her daughter Eliza Carthy, and the Gift Band. It's from their new album, Anchor, which I highly recommend.

Oh heck, here's one more:

"Matty Groves" (Child Ballad 81) performed by the French/American band Moriarty. The song travelled to the New World with early Anglo/Scots settlers, becoming part of the North American traditional songbook too.

The art today is by Daniel Egn��us.

November 2, 2018

Rooted in life

''I want so to live that I work with my hands and my feeling and my brain. I want a garden, a small house, grass, animals, books, pictures, music. And out of this, the expression of this, I want to be writing (Though I may write about cabmen. That���s no matter.) But warm, eager, living life -- to be rooted in life -- to learn, to desire, to feel, to think, to act. This is what I want. And nothing less.''

- Katherine Mansfield (Letters and Journals: A Selection)

Yes, that's it exactly.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers