Terri Windling's Blog, page 70

November 1, 2018

On the Day of the Dead

November 1st, in Mexican and other folklore traditions, is the Day of the Dead; tomorrow, in the Christian calendar, is All Souls' Day. The beginning of November is a traditional time for the honouring of our ancestors, remembering loved ones who have gone, tending graves and cleaning up cemetaries, and for cherishing life while contemplating its inevitable end.

In his wise and beautiful book Anam Cara, the late Irish poet-philosopher John O'Donohue wrote:

"One of the lovely things about the Irish tradition is its great hospitality to death. When someone in the village dies, everyone goes to the funeral. First everyone comes to the house to sympathize. All the neighbours gather round to support the family and to help them. It is a lovely gift. When you are really desperate and lonely, you need neighbours to help you, support you and bring you through that broken time. In Ireland there was a tradition known as caoineadh. These were people, women mainly, who came in and keened the deceased. It was a kind of high-pitched wailing cry full of incredible loneliness. The narrative of the caoineadh was actually the history of this person's life as the women had known him. A sad liturgy, beautifully woven of narrative was gradually put into the place of the person's new absence from the world. The caoineadh gathered all the key events of his life. It was certainly heartbreakingly lonely, but it made a hospitable, ritual space for the mourning and sadness of the bereaved family. The caoineadh helped people to let the emotion of loneliness and grief flow in a natural way.

"One of the lovely things about the Irish tradition is its great hospitality to death. When someone in the village dies, everyone goes to the funeral. First everyone comes to the house to sympathize. All the neighbours gather round to support the family and to help them. It is a lovely gift. When you are really desperate and lonely, you need neighbours to help you, support you and bring you through that broken time. In Ireland there was a tradition known as caoineadh. These were people, women mainly, who came in and keened the deceased. It was a kind of high-pitched wailing cry full of incredible loneliness. The narrative of the caoineadh was actually the history of this person's life as the women had known him. A sad liturgy, beautifully woven of narrative was gradually put into the place of the person's new absence from the world. The caoineadh gathered all the key events of his life. It was certainly heartbreakingly lonely, but it made a hospitable, ritual space for the mourning and sadness of the bereaved family. The caoineadh helped people to let the emotion of loneliness and grief flow in a natural way.

"We have a tradition in Ireland known as the wake," O'Donohue continued. "This ensures that the person who has died is not left on their own on the night after death. Neighbours, family members and friends accompany the body through the early hours of its eternal change. Some drinks and tobacco are usually provided. Again, the conversation of the friends weaves a narrative of rememberance from the different elements of that person's life.

"It takes a good while to really die. For some people it can be quick, yet the way the soul leaves the body is different for each individual. For some people it may take a couple of days before the final withdrawal of the soul is completed. There is a lovely anecdote from the Munster region, about a man who had died. As the soul left the body, it went to the door of the house to begin its journey back to the eternal place. But the soul looked back at the now empty body and lingered at the door. Then, it went back and kissed the body and talked to it. The soul thanked the body for being such a hospitable place for its life journey and remembered the kindnesses the body had shown it during life.

"In the Celtic tradition there is a great sense that the dead do not live far away. In Ireland there are always places, fields and old ruins where the ghosts of people were seen. That kind of folk memory recognizes that people who have lived in a place, even when they move to an invisible form, somehow still remain in that place. There is also the tradition of the coiste bodhar, or the dead coach. Living in a little village on the side of a mountain, my aunt as a young woman heard that coach late one night. This was a small village of houses all close together. She was at home on her own, and she heard what sounded like barrels crashing against each other. This fairy coach came right down along the street beside her house and continued along a mountain path. All the dogs in the village heard the noise and followed the coach. The story suggests that the invisible world has secret pathways where funerals travel.

"In the Irish tradition, there is also a very interesting figure called the Bean Si. Si is another word for fairies and the Bean Si is a fairy woman. This is a spirit who cries for someone who is about to die. My father heard her crying one evening. Two days later a neighbour, from a family for whom the Bean Si always cried, died. In this, the Celtic Irish tradition recognizes that the eternal and the transient worlds are woven in and through each other.

"Very often at death, the inhabitants of the eternal world come out towards the visible world. It can take a person hours or days to die, and preceding the moment of death they might see their deceased mother, grandmother, grandfather or some relation, husband, wife, or friend. When a person is close to death, the veil between this world and the eternal world is very thin. In some cases, the veil is actually removed for a moment, so that you can indeed be given a glimpse into the eternal world. Your friends who now live in the eternal world come to greet you, to bring you home. Usually, for people who are dying, to see their own friends gives them great strength, support and encouragement.

"This elevated perception shows the incredible energy that surrounds the moment of death. The Irish tradition shows great hospitality to the possibilities of this moment. When a person dies, holy water is sprinkled in a circle around them. This helps to keep dark forces away and to keep the presence of light with the newly dead as they go on their final journey."

If you'd like more reading for the Day of the Day, I suggest:

"Imagined Afterlives: Death in Classic Fantasy" by Katherine Langrish; "Tuscon's All Souls Procession" by Stu Jenks; and own essay on "Death in Folk & Fairy Tales."

The passage above is from Anam Cara by John O'Donohue (Bantam, 1997); the poem in the picture captions is from American Primitive by Mary Oliver (Little, Brown, 1983); all rights reserved by the authors. The photographs were taken last week in the graveyard of our village church. The building dates back to 1261, but there was probably a much older church on the same spot before it, and a pagan holy site before that. John O'Donohue, raised in a Gaelic-speaking family in the west of Ireland, was a Catholic priest before devoting himself to writing and scholarship, creating works rooted in the mystical place where pagan and Christian philosophies meet.

October 31, 2018

Happy Halloween & Samhain from all of us at Bumblehill

For Halloween: At the Death of the Year

In Celtic lore, October 31st is Samhain (All Hallow's Eve, or Halloween): the night when Arawn, lord of the Dead, rides the hills with his ghostly white hounds, and the Faery Court rides forth in stately procession across the land. In ancient times, hearth fires were smothered while bonfires blazed upon the hills, surrounded by circular trenches to protect all mortals from the faery host and the wandering spirits of the dead. In later centuries, Halloween turned into a night of revels for witches and gouls, eventually tamed into the modern holiday of costumes, tricks and treats.

Although the prospect of traffic between the living and the dead has often been feared, some cultures celebrated those special times when doors to the Underworld stood open. In Egypt, Osiris (god of the Netherworld, death, and resurrection) was drowned in the Nile by his brother Seth on the 17th of Athyr (November); each year on this night dead spirits were permitted to return to their homes, guided by the lamps of living relatives and honored by feasts. In Mexico, a similar tradition was born from a mix of indigenous folk beliefs and medieval Spanish Catholism, resulting in los Dias de Muertos (the Days of the Dead) -- a holiday  still widely observed across Mexico and parts of the American South-West. The holiday varies from region to region but generally take place over the days of October 31st, November 1st, and November 2nd, celebrated with graveyard gatherings and Carnival-like processions in the streets. Within the house, an ofrenda or offering is painstakingly assembled on a lavishly decorated altar. Food, drink, clothes, tequila, cigarettes, chocolates and children's toys are set out for departed loved ones, surrounded by candles, flowers, palm leaves, tissue paper banners, and the smoke of copal incense. Golden paths of marigold petals are strewn from the altar to the street (sometimes all the way to the cemetary) to help the confused souls of the dead find their way back home.

still widely observed across Mexico and parts of the American South-West. The holiday varies from region to region but generally take place over the days of October 31st, November 1st, and November 2nd, celebrated with graveyard gatherings and Carnival-like processions in the streets. Within the house, an ofrenda or offering is painstakingly assembled on a lavishly decorated altar. Food, drink, clothes, tequila, cigarettes, chocolates and children's toys are set out for departed loved ones, surrounded by candles, flowers, palm leaves, tissue paper banners, and the smoke of copal incense. Golden paths of marigold petals are strewn from the altar to the street (sometimes all the way to the cemetary) to help the confused souls of the dead find their way back home.

According to Fredy Mendez, a Totonac man from Veracruz: "Between 31 October and 2 November, past generations were careful always to leave the front door open, so that the souls of the deceased could enter. My grandmother was constantly worried, and forever checking that the door had not been shut. Younger people are less concerned, but there is one rule we must obey: while the festival lasts, we treat all living beings with kindness. This includes dogs, cats, even flies or mosquitoes. If you should see a fly on the rim of a cup, don't frighten it away -- it is a dead relative who has returned. The dead come to eat tamales and to drink hot chocolate. What they take is vapor, or steam, from the food. They don't digest it physically: they extract the goodness from what we provide. This is an ancient belief. Each year we receive our relatives with joy. We sit near the altar to keep them company, just as we would if they were alive. At midday on 2 November the dead depart. Those who have been well received go laden with bananas, tamales, mole and good things. Those who have been poorly received go empty handed and grieving to the grave. Some people here have even seen them, and heard their lamentations."

(Go here for Stu Jenks' Guest Post on the Day of the Dead festivities in Tucson, Arizona.)

In Greek mythology, Persephone regularly crosses the border between the living and the dead, dwelling half the year with her mother (the goddess Demeter) in the upper world, and half the year with her husband (Hades) in the realm of the dead below. In another Greek story, Orpheus follows his dead wife deep into Hades' realm, where he bargains for her life in return for a demonstration of his musical skills. Hades agrees to release the lovely Eurydice back to Orpheus, provided he leads his wife from the Underworld without looking back. During the journey, he cannot hear his wife's footsteps and so he breaks the taboo. Eurydice vanishes and the pathway to Land of the Dead is closed. A similar tale is told of Izanagi in Japanese lore, who attempts to reclaim his beloved Izanami from the Land of Shadows. He may take her back if he promises not to try to see Izanami's face -- but he breaks the taboo, and is horrified to discover a rotting corpse.

When we look at earlier Sumarian myth, we find the goddess Inana is more successful in bringing her lover, Dumuzi, back from the Underworld; in Babylonian myth, this role falls to Ishtar, rescuing her lover Tammuz: "If thou opens not the gate," she says to the seven gatekeepers of the world below, "I will smash the door, I will shatter the bolt, I will smash the doorpost, I will move the doors, I will raise up the dead, eating the living, so that the dead will outnumber the living." During the three days of Ishtar's descent, all sexual activity stops on earth. The third day of the drama is the Day of Joy, the time of ascent, resurrection and procreation, when the year begins anew.

Coyote, Hermes, Loki, Uncle Tompa and other Trickster figures from the mythic tradition have a special, uncanny ability to travel between mortal and immortal realms. In his brilliant book Trickster Makes This World: Michief, Myth, & Art, Lewis Hyde explains that Trickster is the lord of in-between:

"He is the spirit of the doorway leading out, and the crossroads at the edge of town. He is the spirit of the road at dusk, the one that runs from one town to another and belongs to neither. Travellers used to mark such roads with cairns, each adding a stone to the pile in passing. The name Hermes once meant 'he of  the stone heap,' which tells us that the cairn is more than a trail marker -- it is an altar to the forces that govern these spaces of heightened uncertainty. The road that Trickster travels is a spirit road as well as a road in fact. He is the adept who can move between heaven and earth, and between the living and the dead."

the stone heap,' which tells us that the cairn is more than a trail marker -- it is an altar to the forces that govern these spaces of heightened uncertainty. The road that Trickster travels is a spirit road as well as a road in fact. He is the adept who can move between heaven and earth, and between the living and the dead."

Trickster is one of the few who passes easily through the borderlands. The rest of us must confront the guardians who rise to bar the way: the gods, faeries, and supernatural spirits whose role is to help or hinder our passage over boundaries and through gates, thresholds, and liminal states of mind. In folk tales, guardians can be propitiated, appeased, outwitted, even slain -- but often at a price which is somewhat higher than one really wants to pay.

On Samhain, we cross from the old year to the new -- and that moment of crossing, as the clock strikes the midnight hour, is a time of powerful enchantment. For a blink of an eye we stand poised between two years, two tales, two worlds; between the living and the dead, the mortal and the fey. We must remember to give food to Hecate, wine to Janus, and flowers, songs, smoke, and dreams to the gate-keepers along the way. Shamans, mythic artists, and fantasy writers: they all cast paths of spells, stories, and marigold petals for us to follow, keeping us safe until the sun rises and the world begins anew.

The art above is by my friend and neighbour Brian Froud, from The Land of Froud, Good Faeries/Bad Faeries, The Runes of Efland (with Ari Berk) and Trolls (with Wendy Froud). Some related posts full of spooky tales for All Hallow's Eve: Death in Folklore & Fairy Tales, The Wild Hunt, and Following the Hare.

October 30, 2018

The Blessings of Otters

I'm re-posting this piece from 2015 not only because it reminded me of mythographer Martin Shaw's recent video on the subject of blessings (which I recommend), but also because it is one that I keep thinking about in this angry, divisive political climate. As the Indian sage Ramana Maharshi once said when asked how we should be treating others: "There are no others."

One of the mythic borderlands I'm especially drawn to (as evidenced by my writing and art over the decades) is the place where humans and animals meet: as neighbors, as cousins who speak each other's language, as shape-shifters in each other's skins.

"Long ago the trees thought they were people," says Tulalip storyteller Johnny Moses, recounting a traditional Native America tale. "Long ago the mountains thought they were people. Long ago the animals thought they were people. Someday they will say, 'long ago the humans thought they were people.' "

In "Voyageur," a gorgeous essay by Scott Russell Sanders, the writer and his daughter watch otters during a camping trip in the geographic borderlands between Minnesota and Ontario. What was it that kept him riveted to the spot, watching the animals with such intense fascination? What did the otters mean to him, and what did he want from them?

In "Voyageur," a gorgeous essay by Scott Russell Sanders, the writer and his daughter watch otters during a camping trip in the geographic borderlands between Minnesota and Ontario. What was it that kept him riveted to the spot, watching the animals with such intense fascination? What did the otters mean to him, and what did he want from them?

Not their hides, not their meat, not even a photograph, says Sanders, "although I found them surpassingly beautiful. I wanted their company. I desired their instruction -- as if, by watching them, I might learn to belong somewhere as they so thoroughly belonged here. I yearned to slip out of my skin and into theirs, to feel the world for a spell through their senses, to think otter thoughts, and then to slide back into myself, a bit wiser for the journey.

"In tales of shamans the world over, men and women make just such leaps, into hawks or snakes or bears, and then back into human shape, their vision enlarged, their sympathy deepened. I am a poor sort of shaman. My shape never changes, except, year by year, to wrinkle and sag. I did not become an otter,  even for an instant. But the yearning to leap across the distance, the reaching out in imagination to a fellow creature, seems to me a worthy impulse, perhaps the most encouraging and distinctive one we have. It is the same impulse that moves us to reach out to one another across differences of race or gender, age or class. What I desired from the otters was also what I most wanted from my daughter and from the friends with whom we were canoeing, and it is what I have always desired from neighbors and strangers. I wanted their blessing. I wanted to dwell alongside them with understanding and grace. I wanted them to go about their lives in my presence as though I were kin to them, no matter how much I might differ from them outwardly."

even for an instant. But the yearning to leap across the distance, the reaching out in imagination to a fellow creature, seems to me a worthy impulse, perhaps the most encouraging and distinctive one we have. It is the same impulse that moves us to reach out to one another across differences of race or gender, age or class. What I desired from the otters was also what I most wanted from my daughter and from the friends with whom we were canoeing, and it is what I have always desired from neighbors and strangers. I wanted their blessing. I wanted to dwell alongside them with understanding and grace. I wanted them to go about their lives in my presence as though I were kin to them, no matter how much I might differ from them outwardly."

Later in essay, Sanders writes about two loons who wake him in the middle of the night, "wailing back and forth like two blues singers demented by love," and the bald eagle who watches their progress down the river from its perch on a dead tree's branch. What did the eagle see, he wonders?

"Not food, surely, and not much of a threat, or it would have flown. Did it see us as fellow creatures? Or merely as drifting shapes, no more consequential than clouds? Exchanging  stares with this great bird, I dimly recalled a passage from Walden that I would look up after my return to the company of books: 'What distant and different beings in the various mansions of the universe are contemplating the same one at the same moment! Nature and human life are as various as our several constitutions. Who shall say what prospect life offers to another? Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other's eyes for an instant?'

stares with this great bird, I dimly recalled a passage from Walden that I would look up after my return to the company of books: 'What distant and different beings in the various mansions of the universe are contemplating the same one at the same moment! Nature and human life are as various as our several constitutions. Who shall say what prospect life offers to another? Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other's eyes for an instant?'

"Neuroscience may one day pull off that miracle," Sanders continues, "giving us access to other eyes, other minds. For the present, however, we must rely on our native sight, on patient observation, on hunches and empathy. By empathy, I do not mean the projecting of human films onto nature's screens, turning grizzly bears into teddy bears, crickets into choristers, grass into lawns; I mean the shaman's leap, a going out of oneself into the inwardness of other beings.

"The longing I heard in the cries of the loons was not just a feathered version of mine, but neither was it wholly alien. It is risky to speak of courting birds as blues singers, of diving otters as children taking turns on a slide. But it is even riskier to pretend we have nothing in common with the rest of  nature, as though we alone, the chosen species, were centers of feeling and thought. We cannot speak of that common ground without casting threads of metaphor outward from what we know and what we do not know.

nature, as though we alone, the chosen species, were centers of feeling and thought. We cannot speak of that common ground without casting threads of metaphor outward from what we know and what we do not know.

"An eagle is other, but it is also alive, bright with sensation, attuned to the world, and we respond to that vitality wherever we find it, in bird or beetle, in moose or lowly moss. Edward O. Wilson has given this impulse a lovely name, biophilia, which he defines as the urge 'to explore and affiliate with life.' Of course, like the coupled dragonflies that skimmed past our canoes or like osprey hunting fish, we seek other creatures for survival. Yet even if biophilia is an evolutionary gift, like the kangaroo's leap or the peacock's tail, our fascination with living things carries us beyond the requirements of eating and mating. In that excess, that free curiosity, there may be a healing power. The urge to explore has scattered humans across the whole earth -- to the peril of many species, including our own; perhaps the other dimension of biophilia, the desire to affiliate with life, could lead us to honor the entire fabric and repair what has been torn."

In the conclusion of his essay, Sanders points out that the fellowship of all creatures "is more than a handsome metaphor. The appetite for discovering such connections is also entwined in our DNA. Science articulates in formal terms affinities that humans have sensed for ages in direct encounters with wildness. Even while we slight or slaughter members of our own species, and while we push other species toward extinction, we slowly,  painstakingly acquire knowledge that could enable us and inspire us to change our ways. Only if that knowledge begins to exert a pressure in us, and we come to feel the fellowship of all beings as potently as we feel hunger and fear, will we have any hope of creating a truly just and tolerant society, one that cherishes the land and our wild companions along with our brothers and sisters.

painstakingly acquire knowledge that could enable us and inspire us to change our ways. Only if that knowledge begins to exert a pressure in us, and we come to feel the fellowship of all beings as potently as we feel hunger and fear, will we have any hope of creating a truly just and tolerant society, one that cherishes the land and our wild companions along with our brothers and sisters.

"In America lately, we have been carrying on two parallel conversations: one about respecting human diversity, the other about preserving natural diversity. Unless we merge those conversations, both will be futile. Our efforts to honor human differences cannot succeed apart from our effort to honor the buzzing, blooming, bewildering variety of life of earth. All life rises from the same source, and so does all fellow feeling, whether the fellow moves on two legs or four, on scaly bellies or feathered wings. If we care only for human needs, we betray the land; if we care only for the earth and its wild offspring, we betray our own kind. The profusion of creatures and cultures is the most remarkable fact about our planet, and the study and stewardship of that profusion seems to me our fundamental task."

The sculptures pictured here are by the New Mexican artists Gene & Rebecca Tobey, who worked for years in a fertile partnership creating scuptures, paintings, and drawings inspired by nature and the mythic symbolism of the North American continent. (The titles of the pieces can be found in the picture captions.) Gene died of leukemia in 2006, but Rebecca carries on their beautiful work. Please visit the Tobey Studios website to see more of their collaborative art, and the Rebecca Tobey website for her current pieces.

The passages by Scott Russell Sanders above are from "Voyageurs," an essay in Writing from the Center (Indiana University Press, 1997), highly recommended. All rights to text & imagery above reserved by the author and artists. Many thanks to Ellen Kushner for the opening quote by Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950). For more otters, go here.

The passages by Scott Russell Sanders above are from "Voyageurs," an essay in Writing from the Center (Indiana University Press, 1997), highly recommended. All rights to text & imagery above reserved by the author and artists. Many thanks to Ellen Kushner for the opening quote by Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950). For more otters, go here.

October 29, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week, with Halloween and the Days of the Dead just ahead of us, I've chosen songs of ghosts, revenants, and the uncanny border between life and death....

Above: "There Once Was a Man" by Aiden O'Rourke (co-founder of Lau), who explains:

"It all began with short stories. James Robertson, one of my favourite Scottish authors, wrote a short story every day for a year, and each story had exactly 365 words. I loved reading those stories: a daily dose of poetry and wisdom. And I loved the writing. The language is emotional, concise, apposite. Somehow the words and the pacing of the stories felt musical. I was intrigued by the discipline of setting such a quantifiable daily creative ritual. Would the same be possible in music? In 2016, I decided I would take on a similar writing challenge each day for a year. I told James and he replied, 'Don't do it!' then suggested I give it a month and see if it drove me mad. By 2017, I had 365 new tunes, each one linked to a story from James' collection. There's no doubt the tunes are based in Scottish folk music; that's my backbone, the place I come from, the traditional language I love. There's a parallel with James here, too, because he loves old Scots words and tales."

O'Rourke's music is featured on his lovely album 365: Volume I, released earlier this year, with a second volume forthcoming. In the video above, O'Rourke is accompanied by pianist Kit Downes; and by James Robertson himself, reading the uncanny tale that inspired the tune.

Below: "Fair Margaret & Sweet William" (Child Ballad #74), a ghostly song of tragic love, performed by the great English folksinger June Tabor. The ballad appears on her excellent album An Echo of Hooves (2003).

Above: "I Am Stretched on Your Grave," based on the 17th century Irish poem "T��im s��nte ar do thuama," beautifully sung by Dominie Hooper from Band of Burns. Dominie grew up here in Chagford, dazzling us all with the power of her voice since she was young.

Below: "Wife of Usher's Well" (Child Ballad #79), performed by Scottish singer/songwriter Karine Polwart. In this song, a mother longs for her three dead sons to return to her...but when they do, they come as revenants, not men of flesh and blood. Powart first recorded the song for Fairiest Floo'er (2007), a wonderful CD of traditional ballads -- but this version appeared a year later on the expanded edition of This Earthly Spell.

Above: "Death and the Lady," performed by folk legends Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy, from the north of England. Norma introduces the song, explaining its history and connection to the Black Death.

Below: "The Ballad of George Collins" (also known as "Clerk Colvill," Child Ballad #42), a traditional song performed in an extravagantly untraditional way by the brilliant young folksinger Sam Lee, based in London.

Above: "Kitty Jay" by Seth Lakeman, a song from his 2004 album of the same name, performed in New York earlier this year. Seth, who lives here on Dartmoor, draws much of his song-writing material from local history and lore. Kitty Jay (as the legend goes) was a poor young woman who worked on a remote farm in the late 18th century. Impregnated and betrayed by her master's son, she resolved to take her own life, and for this sin she was buried in unhallowed ground at the Manaton crossroads. The grave, which is not far from our village, is said to be haunted by a shadowy figure. (Kitty herself? Her remorseful lover?) There are always fresh flowers upon it, although no one is ever seen putting them there.

And to end, below: "In a Week," a very dark yet strangely beautiful song about the process of death, written and performed by Hozier (Andrew Hozier-Byrne). He's accompanied here by Alana Henderson. Both musicians are from Ireland.

Dartmoor photographs: An ncient cross near Crzaywell Pool, and Jay's Grave at the edge of the moor near Manaton. If you'd like more spooky songs, last year's Halloween tunes are here,

October 26, 2018

From the archives: Twilight Tales

Between the setting of the sun and the black of night, dusk is a potent, magical time, for in its eerie half-light (according to folklore found around the globe) one can cross the borders dividing our mundane world from supernatural realms.

When I was a child, I longed to discover a doorway into Faerieland or a wardrobe leading to Narnia...and I actually attempted to find one, in the quiet twilight hour of a certain evening on the cusp of autumn. I remember it still: sitting huddled in the shadows, escaping the chaos of a troubled home, determined to conjure a portal to a magic realm by sheer force of will. I failed, of course. But like many children hungry for a deeper connection with the spirit-filled unknown, what I couldn't find in New Jersey that night I discovered in the pages of fantasy books...and, later, in the study of folklore and a life-time of wandering the landscape of myth.

My younger self may have been in the wrong place, but I'd instinctively managed to chose the right time, for twilight, according to British and other folk tales, contains powerful magic.

"Anytime that is 'betwixt and between' or transitional is the faeries' favorite time," says painter and mythographer Brian Froud. "They inhabit transitional spaces like the bottom of the garden: existing in the boundary  between cultivation and wilderness. Or at the edges of water, the spot that is neither land nor lake, neither path nor pond. They relish moments of 'flux and flow': the hush between night and day, the times of change between one season and the next. They come when we are half-asleep. They come at moments when we least expect them; when our rational mind balances with the fluid irrational."

between cultivation and wilderness. Or at the edges of water, the spot that is neither land nor lake, neither path nor pond. They relish moments of 'flux and flow': the hush between night and day, the times of change between one season and the next. They come when we are half-asleep. They come at moments when we least expect them; when our rational mind balances with the fluid irrational."

In myth, it is rarely easy to cross from the human world to the Otherlands, whatever those Otherlands may be: Faerie, Tir-na-nog, the Spirit World, the Underworld and the Realm of the Dead. Gods and guardians of the threshold are the border guards who will either stamp your passport or block your way -- such as Janus, the god of doorways, gateways, passages, beginnings and endings in Roman mythology; or Cardea, with whom he is often paired, the goddess of door-hinges, domestic thresholds, passageways of the body, and liminal states. According to Robert Graves' mad and brilliant book, The White Goddess, Cardea was propitiated at weddings by lighting torches of hawthorne, her sacred tree, for she had the power "to open what is shut; and shut what is open." (She was thus associated with virginity, virginity's end, and, consequently, with childbirth.)

A wide variety of guardian figures around the world (gods, faeries, supernatural spirits) regulate passage through mystic thresholds and access to sacred groves, glens, springs and wells. Some of them guard whole forests and mountains, while others protect individual trees,  hills, stones, bridges, crossings, and crossroads. Myth and folklore tells us these guardians can be appeased, tricked, outwitted, even slain -- but usually at a price which is somewhat higher than one wants to pay.

hills, stones, bridges, crossings, and crossroads. Myth and folklore tells us these guardians can be appeased, tricked, outwitted, even slain -- but usually at a price which is somewhat higher than one wants to pay.

Sometimes it is the land itself preventing casual passage across mythic boundaries. In the Scottish ballad "Thomas the Rhymer," a river of human blood stands between Faerieland and the mortal world, and Thomas must pay the price of seven years servitude to make that crossing. In the German fairy tale "Brother and Sister," an enchanted stream must be crossed three times in the siblings' flight through the deep, dark woods. They are sternly warned not to stop and drink -- but the brother breaks this magical taboo and is transformed into a deer. In other tales, one princess must climb seven iron mountains to reach the land where her love is imprisoned; another must trick the winds into carrying her where her feet cannot. A magical hedge of thorns is the boundary between Sleeping Beauty's castle and the everyday world, and it cannot be penetrated until time, blood, and prophesy all stand aligned.

Trickster is a rare mythic figure who crosses borders and boundaries with ease. In his various guises around the globe (Hermes, Mercury, Loki, Legba, Maui, Monkey, Anansi, Coyote, Raven, Manabozho, Br'er Rabbit, Puck, etc.) he moves back and forth between the realms carrying messages, stealing fire and cattle, making mischief on both sides of the border, dancing in the borderlands between, and (in his role of Psychopomp) leading the dead in their journey to the Underworld or the Spirit Lands.

Tricksters, Lewis Hyde points out, "are the lords of in-between. A trickster does not live near the hearth; he does not live in the halls of justice, the soldier's tent, the shaman's hut, the monastery. He passes through each of these when there is a moment of silence, and he enlivens each with mischief, but he is not their guiding spirit. He is the spirit of the doorway leading out, and of the crossroad at the edge of town (the one where a little market springs up). He is the spirit of the road at dusk, the one that runs from one town to another and belongs to neither. There are strangers on that road, and thieves, and in the underbrush a sly beast whose stomach has not heard about your letters of safe passage....

"Travellers used to mark such roads with cairns," Hyde continues, "each adding a stone to the pile in passing. The name Hermes once meant 'he of the stone heap,' which tells us that the cairn is more than a trail marker -- it is an altar to the forces that govern these spaces of heightened uncertainty, and to the intelligence needed to negotiate them. Hitchhikers who make it safely home have somewhere paid homage to Hermes."

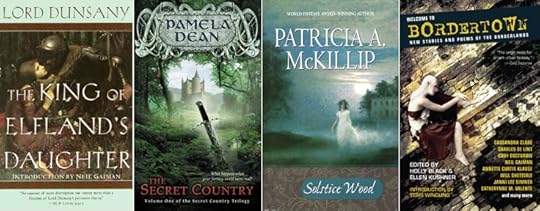

Many fantasy novels grow from the desire to go beyond the fields we know or to find the hidden door in the hedge. Unlike Tolkien's Lord of the Rings or Le Guin's Earthsea books, set entirely in invented landscapes, the protagonists of these tales cross over a border, or through a magical portal, traveling from our world to a strange Otherland. This device was used most famously in C.S. Lewis's The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (and his other Narnia books), but also in Andre Norton's Witchworld series, Pamela Dean's Secret Country books, Joyce Ballou Gregorian's Tredana trilogy, Charles de Lint's Moonheart, Phillip Pullman's His Dark Materials (although Lyra's Oxford, or Will's, aren't exactly our own), and numerous others. There are also tales in which movement across the border goes in the opposite direction, spilling magic from the Otherworld into our own, such as Robert Holdstock's Mythago Wood series, Patricia McKillp's Solstice Wood, and William Hope Hodgson's The House on the Borderlands (1908). In his classic novel The King of Elfland's Daughter (1924), the great Irish fantasist Lord Dunsany focused on the borderland itself: the tricksy, shifting landscape squeezed between the mortal and magical realms...a device that was then irreverently updated by Bordertown, one of the earliest series in the "urban fantasy" genre, with its motorcycle-riding and rave-dancing elves, humans, and halflings in a crumbling city at the edge-lands of Faerie.

Magical Realist works on the mainstream shelves also make use of border-crossing themes. Rick Collignon's The Journal of Antonio Montoya, Pat Mora's House of Houses, Alfredo Vea Jr.'s La Maravilla, Kathleen Alcala's Spirits of the Ordinary, and Susan Power's The Grass Dancer are all extraordinary books where the membrane between the worlds of the living and the dead is thin and torn; as is Leslie Marmon Silko's wide-ranging refutation of borders, The Almanac of the Dead. In Thomas King's Green Grass, Running Water, Trickster crosses easily from the mythic to modern world; while in Antelope Wife by Louise Erdrich these worlds are stitched together in the intricate patterns of Indian beadwork.

As myth, folklore, and fairy tales remind us, the border between any two things is a traditional place of enchantment: a bridge between two banks of a river; the silvery light between night and day; the liminal moment between dreaming and waking; the motion of shape-shifting transformation; and all those interstitial realms where cultures, myths, landscapes, languages, art forms, and genres meet.

We cross the border every time we step from the mundane world to the lands of myth; from mainstream culture to the pages of a mythological study or a magical tale. As a folklorist and fantasist, I cannot resist an unknown road or an open gate. I'm still that child at twilight on an autumn eve, willing magic into existence.

Words: The quote by Brian Froud is from a conversation I noted down when I was editing his book Good Faeries, Bad Faeries (Simon & Schuster, 1998). The quote by Lewis Hyde is from his excellent book Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, & Art (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1998). Pictures: Art credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to the text and imagery above is reserved by their respective creators.

Words: The quote by Brian Froud is from a conversation I noted down when I was editing his book Good Faeries, Bad Faeries (Simon & Schuster, 1998). The quote by Lewis Hyde is from his excellent book Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, & Art (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1998). Pictures: Art credits can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to the text and imagery above is reserved by their respective creators.

October 25, 2018

Tales from the Hedge

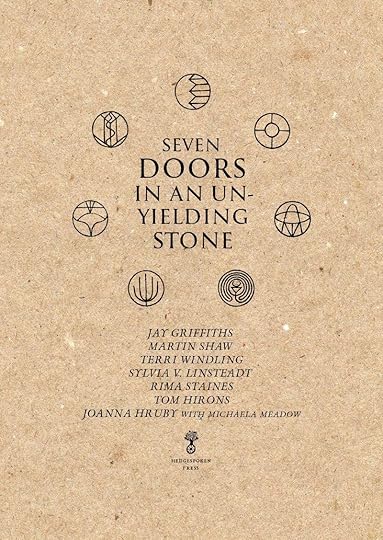

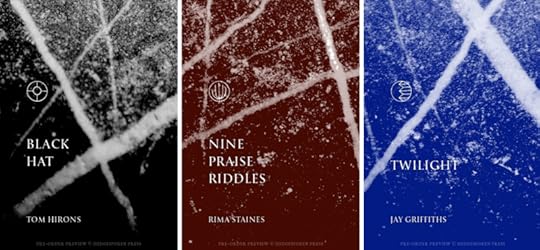

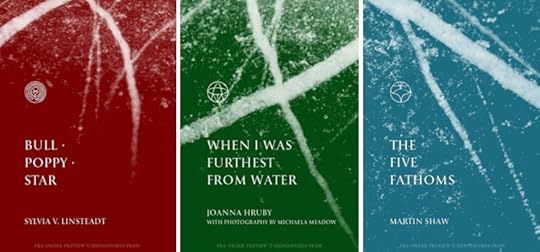

Earlier this year, I received an intriguing invitation from my friends Tom Hirons & Rima Staines -- storytellers, mythic wanderers, and proprietors of Hedgespoken Press. They were planning an unusual new project, and asked if I'd like to join in.

They envisioned a series of pocket-sized books designed by and published by Hedgespoken. Seven authors. Seven beautiful books. Seven ways to approach the unapproachable and speak about the unspeakable.

They envisioned a series of pocket-sized books designed by and published by Hedgespoken. Seven authors. Seven beautiful books. Seven ways to approach the unapproachable and speak about the unspeakable.

"We picture," they said, "a small book found somewhere in the wilds or in some threshold place: a railway station or the waiting room of an undertaker or a nurse; the book is a flash of lightning, a searing experience, something initiatory. We imagine a reader finding a book unexpectedly, picking it up and being drawn in, to another world, leaving that world slightly stunned and perhaps a little changed."

What a marvelously mythic concept! And also, what a challenging one. I wondered what on earth I could write...but I said yes to them at once.

The seven small books are now complete, and will be available as of mid-November. There's a launch party at Dartington Village Hall on November 10th, and all are welcome -- so please come join us for stories and revelry if you happen to be in travelling distance of Dartmoor.

The seven small books are now complete, and will be available as of mid-November. There's a launch party at Dartington Village Hall on November 10th, and all are welcome -- so please come join us for stories and revelry if you happen to be in travelling distance of Dartmoor.

My own contribution to the series is a collection of seven tiny tales that fall somewhere between poetry and prose: mythic messages that you might find buried in ivy and leaves or under a mossy stone. Tom calls them "poems-prayers-chants," and that's as good a description as any.

The other authors in the series are Jay Griffiths, Martin Shaw, Sylvia V. Linsteadt, and Joanna Hruby, plus Tom and Rima themselves. For more information, or to pre-order the books (either individually or as a boxed set), please visit the Hedgespoken Press site.

October 24, 2018

Finding the Words

From "Writing With and Through Pain" by Sonya Huber:

"It���s an odd thing to continue to show up at the page when the brain and the fingers you bring to the keyboard have changed. Before the daily pain and head-fog of rheumatoid disease, I could sit at my computer and dive headlong into text for hours. Like many writers, I had a quasi-religious attachment to the feeling of jet-fuel production, the clear writing process of my twenties: the silence I required, the brand of pen I chose when I wrote long-hand, those hours when I would sit and pour out words and forget to breathe.

"Then, I thought that my steel-trap focus made for good writing, but I confess that I���m not sure what 'good writing' means anymore. For example, what happens when the fogged writing you thought was sub-par results in your most popular book? ...

"Today I am tired -- despite a full night���s sleep -- merely because I had a busy workday yesterday. I���m actually hungover, in a sense, from standing upright and talking between 9:00 am and 5:00 pm. Before I got sick, I would have declared this day a rare lost cause. But this is the new normal. Now, even the magic of caffeine doesn���t allow me to smash through the pages like I used to. As my body and mind changed, I feared that I would become unhinged from text itself, and from the thinking and insight that text provides. In a way, that did happen. Over the past decade, I have had to remake my contract with sentences and with every step of the writing process. The good thing is that there���s plasticity in that relationship, as long as I am patient.

"I don���t know a lot about neurology, but here���s what it feels like: there���s a higher register, buzzing, logical, and mathematical, in which I could often write when I was at full energy. And then there���s a lower tone, slower and quieter -- my existence these days. The music of the words sounds completely different at this lower register, producing different voices and different shapes, but it still resonates. It requires me to intuit more, to pay much more attention to non-verbal senses and emotional structures and to try to put them into words, rather than to follow the intellectual string of words themselves.

"Although our diseases are very different, I have felt what Floyd Skloot describes in his essay 'Thinking with a Damaged Brain,' in which he traces the ways his thought processes have been altered by the aftermath of a virus that ravaged his attention and memory:

'I must be willing to write slowly, to skip or leave blank spaces where I cannot find words that I seek, compose in fragments and without an overall ordering principle or imposed form. I explore and make discoveries in my writing now, never quite sure where I am going but willing to let things ride and discover later how they all fit together'

"I do work more slowly. Of necessity, I place more faith in Tomorrow Me. When I stop writing, daunted by a place where I���m stuck, my energy plummets and I hand it off, knowing I���ll pick up the challenge on the next session....The dim semaphore through which my sentences arrive today leads to a strange by-product: I have less energy to worry about all the ways in which I might be wrong (though maybe age and confidence have also helped). In plodding along slowly, my voice has become clearer, at least in my own head. This slow writing forces me to make each word count."

Please take the time to read Huber's insightful essay in full (published online at Literary Hub), as this is just a small taste of it. I also recommend her collection Pain Takes Your Keys & Other Essays from a Nervous System, as well as her other fine books.

Some other good pieces on writing with, or about, illness and pain:

"Stephanie Burgis Talks about Snowspelled" (Mary Robinette Kowal's blog)

If you're having trouble with this link, try this url: https://maryrobinettekowal.com/journa...

"Out of My Mind" by Sarah Perry (The Guardian)

"On the Harmed Body: A Tribute to Hillary Gravendyk" by Diana Arterian (Los Angeles Review of Books)

"On Telling Ugly Stories: Writing with a Chronic Ilnness" by Nafissa Thompson-Spires (The Paris Review)

"Writing and Illness: More Than Metaphor" by Victoria Brownworth (Lambda Literary)

"The Heart-Work: Writing About Trauma as a Subversive Act" by Melissa Febos (Poets & Writers)

My own various writings on illness, posted on this blog, are collected here.

"In order to keep me available to myself," wrote Audre Lord in The Cancer Journals, "and able to concentrate my energies upon the challenges of those worlds through which I move, I must consider what my body means to me. I must also separate those external demands about how I look and feel to others, from what I really want for my own body, and how I feel to my selves."

This is also a challenge for all of us, the sick and the well alike.

Words: The passage above is from "Writing With and Through Pain" by Sonya Huber (Literary Hub, June 25, 2018). The Andre Lorde quote is from The Cancer Journals (Aunt Lute Books, 1980). The poem in the picture captions is from Guts Magazine (November 19, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors. Drawing: "The Little Mermaid" by Helen Stratton (1867-1961). Photographs: A walk on the pebble beach at Budleigh Salterton on the south Devon coast, late summer, with my old friends Ellen Kushner and Delia Sherman, and my husband Howard.

October 23, 2018

The magic of the in-between

From "Notes to a Modern Storyteller" by Ben Okri:

"Our age is lost in sensational tales. Without genuine mystery, the mystery of art, a story will not linger in the imagination."

"A fragment is more fascinating than the whole."

"The mind likes completion. If you give the mind complete stories you give it nothing to do. The Trojan War lasted twenty years. But Homer tells only of one year, one quarrel, one rage. Yet has a war haunted us more? It is a war story to which others turn, as a source."

"Indirection fascinates. Straight roads make the mind fall asleep. But we all love to take hidden paths, roads that bend and curve. The Renaissance artists understood the appeal of paths that wander out of view. We want to travel the untravelled road.

"We should learn to tell untold stories, stories that wander off the high roads; stories like roads untaken. This is the only cure for the despair that all the stories have been told, that there are no stories under the sun. All the high road stories have been told, but not the hidden road stories that lead to the true center."

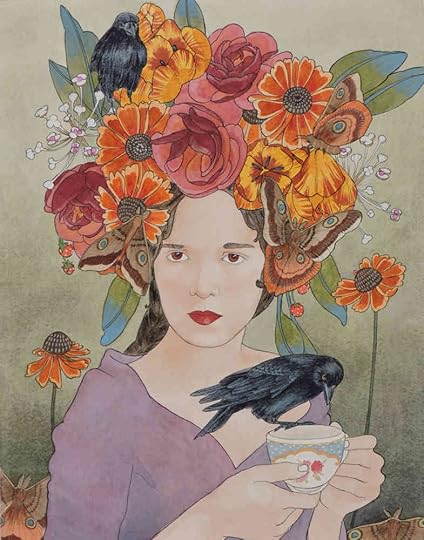

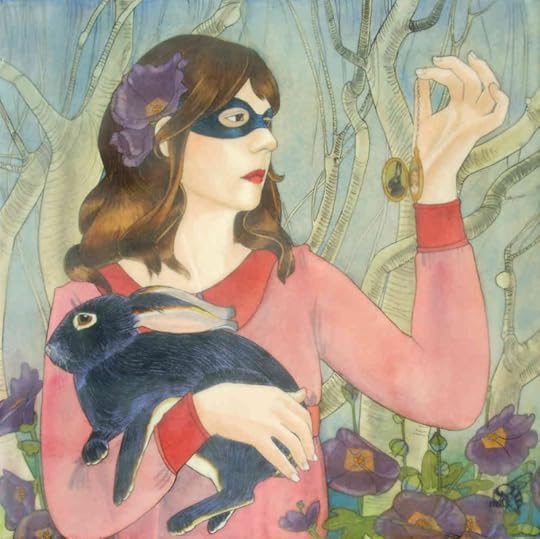

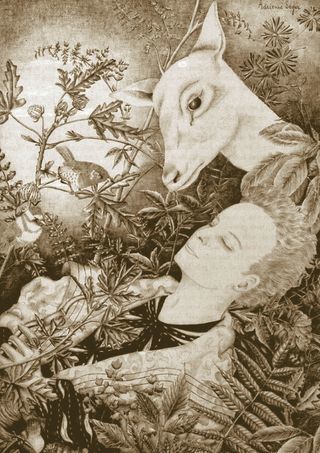

The imagery today is by Mary Alyne Thomas, an American artist raised in the high desert of New Mexio and now based on the North-West coast.

"My paintings are a complex layering of encaustic and silkscreen over a watercolor painting," she explains. "There is a sense of mystery, a softness that emanates from the floating art forms within the transparent, waxy surface. It creates an atmospheric work, a dreamy ethereal expression.

"I am constantly inspired by the wildlife, forests and dark beauty of my home in Portland, Oregon, but childhood memories of wandering the mesas in Santa Fe continue to compel my work. I strive to capture those magical ephemeral moments we all experience, real or imagined."

Thomas' enigmatic paintings are perfectly suited to Okri's words on the power of mystery, for the title of each reads like the fragment of a story -- conjuring an archetypal tale that the view must imagine and complete. (Run your cursor over the pictures to read the titles. They are also listed at the bottom of the post.)

A story dwells, says Okri, "in the ambiguous place between the teller and the hearer, between the writer and reader. The greatest storytellers understand this magical fact, and use the magic of the in-between in their stories and in their telling."

I couldn't agree more.

Pictures: The paintings above are Mary Alayne Thomas. The titles, from top to bottom, are: Reading the Tea Leaves, Playing for Keeps, The Search, The Mystery of the Golden Locket, Even the Tiger Stopped to Listen to her Tale, All Clues Led Them to this Place, and The Librarian. All rights reserved by the artist. Words: The quotes above are are from The Mystery Feast: Thoughts on Storytelling by Ben Okri (Clairview Books, 2015). All rights reserved by the author.

October 22, 2018

Tunes for a Monday Morning

As the hills of Devon turn gold and rust, and the leaves start to fall from the oaks of the wood, here are folk songs of harts and foxes, hounds and hares, the hunters and the hunted.

Above: "The Death of the Hart Royal," performed by the English folk trio Faustus (Paul Sartin, Benji Kirkpatrick, and Saul Rose). This unusual ballad of Robin Hood, Lord of the Greenwood, was found in the archives of Somerset folk song collector Ruth Tongue. The band recorded it for their third album, Death and Other Animals (2017), when they were Artists in Residence at Halsway Manor, the National Folk Arts Centre in Somerset's Quantock Hills.

Below, "While Gamekeepers Lie Sleeping," a traditional poaching song performed by the great English folk singer June Tabor (in a rare video from 1990), followed by another hunting song from the animal's point of view: "The Hare's Lament" sung by Susan McKeown, an Irish musician based in New York City.

Above: "I am the Fox," written and performed by Nancy Kerr (from London) and James Fagan (from Sydney, Australia). This is my favourite hunting song. You'll soon see why.

Below: "The Fox," a traditional song exuberantly performed by the Celtgrass band We Banjo 3 (Enda Scahill, Fergal Scahill, Martin Howley, David Howley) from Galway, Ireland. The song appears on the band's second album, Gather the Good (2014), and features Sharon Shannon on accordion.

Above: "Hares on the Mountain," performed by Radie Peat and Daragh Lynch from Lankum, the anarchic folk-punk band based in Dublin, Ireland.

Below: "Stags Bellow" by singer-songwriter Martha Tilston, based on the Cornish coast. It comes from her album Machines of Love and Grace (2012), and captures the beauty of the Devon/Cornwall peninsula in the rich golden light of autumn.

For a sequence of five posts about deer in myth, folklore, and poetry, start here. For the folklore of hares and rabbits, go here and here. For the folklore of foxes, go here and here.

The white stag painting above is by American book artist Ruth Sanderson.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers