Terri Windling's Blog, page 66

February 5, 2019

Happy Chinese New Year!

On the first day of the Year of the Pig, let's look at a bit of porcine myth and folklore:

Pigs in their various forms, from wild boar to domesticated swine, are extremely ambivalent figures in myth, sacred in some contexts, demonic in others, or (in the paradoxical manner so common to magical tales) both revered and shunned at the same time. The pig as a sacred animal seems to belong to the early goddess religions, about which our knowledge is far from complete -- but carvings and other artifacts found all across what is now western Europe indicate that the pig was an aspect of the Great Goddess, associated with fertility, the moon, and the season cycles of life and death.

As Alison Hawthorne Deming explains in her excellent book Zoologies:

"The process of pig domestication began in the Tigris Basin thirteen thousand years ago; in Cyprus and China, eleven thousand years ago. Sculptures of pigs have been unearthed in Greece, Russian, Yugoslavia, and Macedonia. Marija Gimbutas, in her keystone work The Godddess and Gods of Old Europe, writes that 'the fast-growing body of the pig will have been compared to corn growing and ripening, so that its soft fats apparently came to symbolize the earth itself, causing the pig to become a sacred animal probably no later than 6000 BC.' The goddess of vegetation sometimes wears a pig mask. Sometimes the pig figurine, fleshy and round, is scored with traces of grain pressed into the clay or is graced with earrings. The prehistoric goddess of vegetation dates back to Neolithic times and is predicessor to Demeter, the Greek goddess of fertility and harvest, whose temple at Eleusis was built in the second century BCE.

"The Eleusinian Mysteries," Deming continues, "became the principal religious ritual of ancient Greece, begun circa 1600 BCE. Originally a secret cult devoted to Demeter, the rites honored the annual cycle of death and rebirth of grain in the fields. The resurrection of seeds buried in the ground inspired the faith that similar resurrection might  await the human body laid to rest in the earth. The religious rituals of the Eleusinian Mysteries lasted two thousand years, became the official state religion, and spread to Rome. They laid the groundwork for Christianity's belief in resurrection and were ultimately overthrown by the Roman emperor in the fourth century CE.

await the human body laid to rest in the earth. The religious rituals of the Eleusinian Mysteries lasted two thousand years, became the official state religion, and spread to Rome. They laid the groundwork for Christianity's belief in resurrection and were ultimately overthrown by the Roman emperor in the fourth century CE.

"The canonical source of Demeter's story, the 'Homeric Hymn to Demeter,' dates from about a thousand years into the practice of these rituals. It is called Homeric because it employs the same meter as The Iliad and The Odyssey -- dactylic hexameter, the rhythm of 'Picture yourself in a boat on the river / With tangerine trees and marmalade skies.'

"The foundation of the Mysteries is Demeter's power over the fertility of the land. When her daughter Persephone is stolen by Hades to be his lover in the underworld, the mother's grief is so acute that she refuses to let the fields produce grain. People are in danger of starving, but Demeter resists, saying there will be no crops until she sees her daughter return. When Persephone does come back, after many trials among mortals and much dealing making among the gods, Demeter's sudden transformation of bare ground into a 'vast sheet of ruddy grain' marks the miracle of fruition returning after a fallow time and sparks the fertility cult of the mysteries. This metamorphosis occurs in mythic time, so it is safe to say that it continues in the present moment for the mind embracing its truth.

"Suckling pigs played a key role in the festival of Thesmophoria, a three-day rite that took place in October, the time for autumn sowing of barley and winter wheat. As I write this, the word sow catches my eye, as both noun for the female pig and verb for planting seeds. The Oxford English Dictionary tells me that the two words come from different Old English roots, but nonetheless history delivers the homograph to modernity still carrying freight from the ancients. Pig = grain. And the corollary, embedded in prehistoric art: pig = Earth = survival."

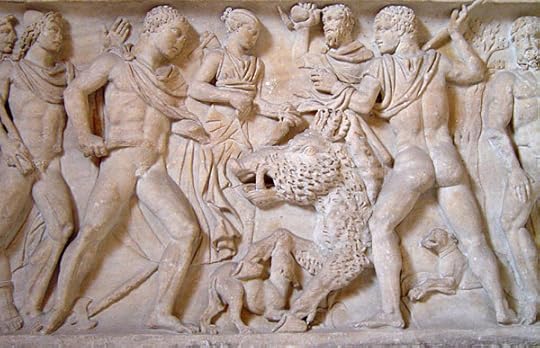

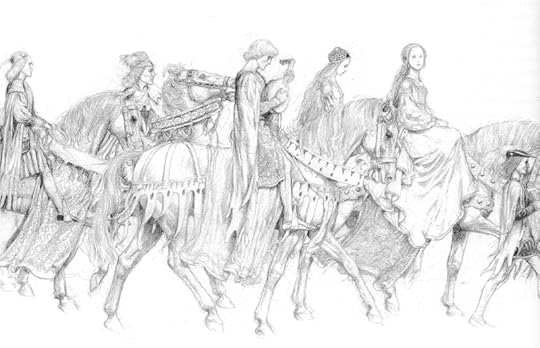

In stories from later periods of classical myth, the pig appears in a number of hero tales: not as a sacred animal now but as a monster to be slain. Thesues, for example, kills the Crommyonian Sow who is ravaging the countryside near Crommyon. This was no ordinary pig, but the daughter of Echidna (a snake-woman) and Typhone (the monstrous son of Gaia), named after the woman who raised her. The Crommoyonian Sow was, in turn, the mother of the Calydonian Boar sent by Artemis to punish the region of Calydon, where the king had neglected the rites of the gods. The creature is killed in the famous Hunt of the Calydonian Boar by the king's son Meleager, aided (for complicated reasons) by the goddess Atlanta.

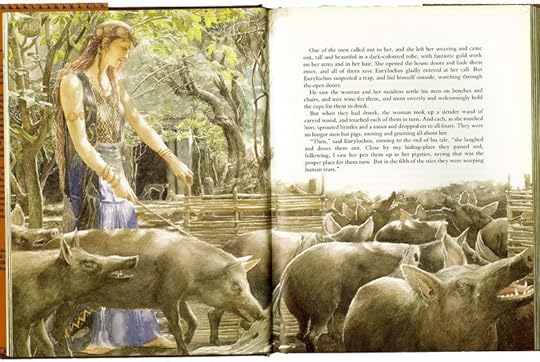

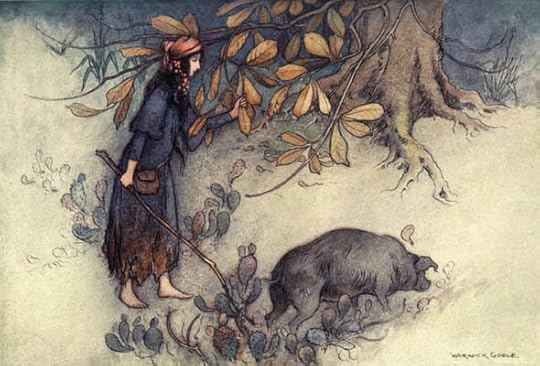

Pigs appear all throughout The Odyssey, though largely in the background of the story: Odysseus is the king of Ithaca, an island reknown for its farmland and herds of fat swine. He is the son of La��rtes, an Argonaut who participated in the Hunt of the Calydonian Boar. During his long journey home from the Trojan War, Odysseus encounters Circe the sorceress, who turns his men into swine (and other animals)...and then falls in love with Odysseus and releases the crew from enchantment. When our hero reaches Ithaca at last, he hides himself in his swineherd's house while taking measure of all that's gone on in his absence, and it's there, among dogs and pigs, that he is reunited with his son Telemachus. He finally makes his way to his own house, disguised, where his elderly nurse recognizes him: while washing his feet, she spies an old scar he received from a boar hunt many years before.

Aneas, another hero of the Trojan War, is also associated with pigs. In Book VIII of Virgil's Aeneid, the river god Tiberinus appears to Aeneas in a dream to tell him his son is destined to found the great city of Alba. He will know place when he sees this omen: a spotless white sow with thirty white piglets. This comes to pass and the city, which will be Rome, is duly founded.

The poor pig does not fare well in the myths the Middle and Near East, including those of the Abrahamic religions, where the animal is viewed as an unclean and defiled creature in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian stories alike. It is tempting to attribute the pig���s fall from grace to its association with women's mysteries -- but while this may have played a role, there are also practical reasons why the animal was shunned. As Mark Essig writes in his fascinating book Lesser Beasts:

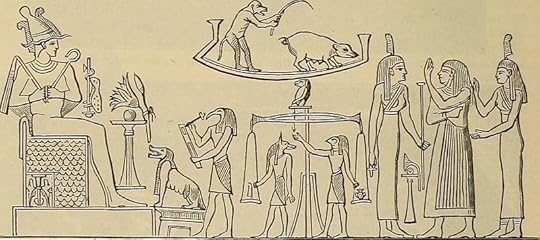

"By the start of the Iron Age, about 1200 bc, elites in the Near East had begun to see pigs as polluting, a view that arose in part from the habits of urban pigs. Though cities had grown large, sanitation systems had not kept pace. Residents threw garbage into the streets or piled it in heaps outside their doors....Dogs and pigs had first domesticated themselves by scavenging human waste, but now that role made them pariahs. Filthy animals offended the gods and therefore were excluded from holy places. The people of the Near East practiced many different religions, but all agreed that the key sacrificial animals were sheep, goats, and cattle and that pigs were unclean. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, pigs never appear in religious art. The Harris Papyrus, which describes religious offerings made by King Ramses III, includes a detailed list of every desirable item to be found in Egypt and the lands it had conquered, including plants, fruits, spices, minerals, and meat. Pork does not appear on the list. 'The pig is not fit for a temple,' a Babylonian text reads, because it is 'an offense to all the gods.' A Hittite text declares, 'Neither pig nor dog is ever to cross the threshold' of a temple. If anyone served the gods from a dish contaminated by pigs or dogs, 'to that one will the gods give excrement and urine to eat and drink.' "

"By the start of the Iron Age, about 1200 bc, elites in the Near East had begun to see pigs as polluting, a view that arose in part from the habits of urban pigs. Though cities had grown large, sanitation systems had not kept pace. Residents threw garbage into the streets or piled it in heaps outside their doors....Dogs and pigs had first domesticated themselves by scavenging human waste, but now that role made them pariahs. Filthy animals offended the gods and therefore were excluded from holy places. The people of the Near East practiced many different religions, but all agreed that the key sacrificial animals were sheep, goats, and cattle and that pigs were unclean. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, pigs never appear in religious art. The Harris Papyrus, which describes religious offerings made by King Ramses III, includes a detailed list of every desirable item to be found in Egypt and the lands it had conquered, including plants, fruits, spices, minerals, and meat. Pork does not appear on the list. 'The pig is not fit for a temple,' a Babylonian text reads, because it is 'an offense to all the gods.' A Hittite text declares, 'Neither pig nor dog is ever to cross the threshold' of a temple. If anyone served the gods from a dish contaminated by pigs or dogs, 'to that one will the gods give excrement and urine to eat and drink.' "

(You can read an engrossing except from Lessig's book here.)

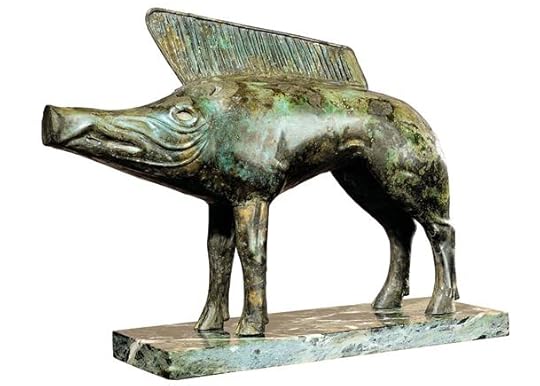

The pig fared better among the Norse and the Celts, for whom -- as with the Demeter cults -- it was valued not only as a source of food but also as a divine animal, associated with the cycle of birth and death, the moon, the underworld, and intuitive wisdom.

In Norse myth, both Freyr (god of virility and prosperity) and his sister Freyja (goddess of love, sex, and fertility) held the wild boar under special protection, and are sometimes depicted together in a chariot drawn by a heavenly boar with golden bristles. In Hyndlulj����, an Old Norse poem that forms part of the Poetic Eddas, Freyja has a companion boar named Hildisv��ni, whose name means "Battle Swine."

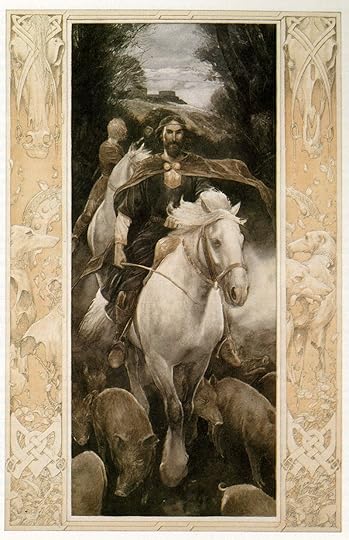

In Celtic Ireland, not only were wild boars and sows held in high esteem, but so were domestic pigs; and the swineherds who tended them were credited with magical powers. Their herds of swine would have been semi-wild, foraging for food in the forests of kings; the herders were thus semi-wild themselves and imbued with the woodland's magic. The T��in B�� C��ailnge and other ancient texts tell stories of swineherds who battle each other in contests of magic, or who utter prophesies at key moments in the lives of heroes and kings.

In Welsh legend, the enchantress Ceridwen (possessor of the Cauldron of Inspiration which turns Gwion Bach into Taliesin) is referred to as The White Sow; and in some Welsh folklore traditions she had the power to assume that shape. The following passage from The Mabinogion describes the introduction of pigs to that land:

"Lord," said Gwydion [to Math son of Mathonwy],I have heard tell there have come to the South such creatures as never came to this Island." "What is there name?" said he. "Hobeu, lord." "What kind of animals are those?" "Small animals, their flesh better than the flesh of oxen. But they are small and they change names: moch are they called nowadays." "To whom do they belong?" "To Pryderi son of Pwyll, to whom they were sent from Annwn [the Underworld], by Arawn king of Annwn."

Whereupon Gwydion concocts a plan to steal these animals for his own land, setting off all manner of troubles....

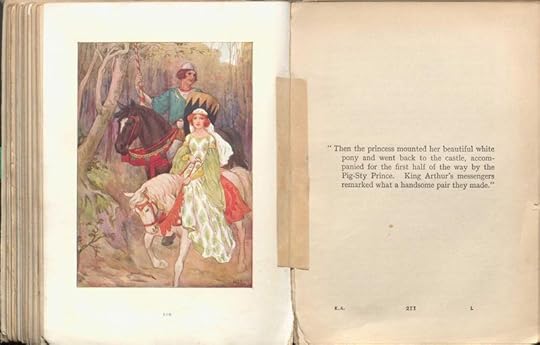

In fairy tales, lowly pig keepers usually turn out to be princes or princesses in disguise. Likewise, the "Pig-Sty Prince" of Arthurian lore, a child found abandoned among the swine, turns out to be cousin to Arthur himself and grows up to win the hand of a princess.

Today, science has confirmed that pigs are highly social and intelligent animals....which only makes their abuse by the modern system of factory farming all the more horrific. Perhaps if we recognized them (and all creatures) as sacred beings this could finally change.

The pig photographs in this post are from my friend Elizabeth-Jane Baldry (pictured below), a harpist, composer, and filmmaker here in Chagford who kept pigs for a time to forage in her beautiful woodland, Pigwiggen Wood. The sow is Blossom, and the piglets are ones she gave birth to back in 2010. They have since been re-homed...but not eaten, I assure you!

The art above (top to bottom): a Greek terracotta pig votive, circa 5th c. BCE; a figure of Demeter with pig found near Athens, circa 5th c. BCE; a marble pig votive; The Calydonian Hunt shown on a Roman frieze at the Amsmolean Museum, Oxford; Circe and her pigs in The Wanderings of Odysseus, illustrated by Alan Lee; a marble relief showing Aneas and his son with the White Sow of Alba; a Greek terracotta boar askos, circa 4th c. BCE; imagery from the Egyptian tomb of Ramses II depicting how Horus would judge souls in the afterlife, reincarnating the bad ones as pigs; a bronze boar statue from the Celtic sanctuary at Neuvy-en-Sullias, circa 1st c. BCE; "Gwydion steals the pigs of Pryderi" from The Mabinogion, illustrated by Alan Lee; The Pig Keeper by Warwick Goble (1862-1943); and The Pig-Style Prince by Harry G. Theaker (published in 1925).

The quotations above come from Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit by Alison Hawthorne Deming (Milkweed Editions, 2014), and Lesser Beasts: A Snout-to-Tail History of the Humble Pig by Mark Essig (Basic Books, 2015). The poem in the picture captions, "Circe's Power" by Louise Gluck, is from The New Yorker (April 10, 1995), with thanks to Christine Norstrand for introducing me to it. The passage from The Mabinogion comes from the Gwyn Jones & Thomas Jones translation (Dragon's Dream edition, 1982). All rights to the quoted text is reserved by the authors.

January 30, 2019

What winter is

''Winter, then in its early and clear stages, was a purifying engine that ran unhindered over city and country, alerting the stars to sparkle violently and shower their silver light into the arms of bare upreaching trees. It was a mad and beautiful thing that scoured raw the souls of animals and man, driving them before it until they loved to run.''

- Mark Halprin (A Winter's Tale)

"That���s what winter is: an exercise in remembering how to still yourself then how to come pliantly back to life again.���

- Ali Smith (Winter)

"May we find comfort in the 'repeated refrains of nature,' the softly sheltering snow, the changing seasons, the return of blackbirds to the marsh....

"May we find strength in light that pours in under snow and laughter that breaks through tears....

"May we go out into the light-filled snow, among meadows in bloom, with gratitude for life that is deep and alive. May Earth's fire burn in our hearts, and may we know ourselves part of this flame -- one thing, never alone, never weary of life."

- Kathleen Dean Moore (Wild Comfort)

"Love life first, then march through the gates of each season; go inside nature and develop the discipline to stop destructive behavior; learn tenderness toward experience, then make decisions based on creating biological wealth that includes all people, animals, cultures, currencies, languages, and the living things as yet undiscovered; listen to the truth the land will tell you; act accordingly."

- Gretel Ehrlich (The Future of Ice)

First snow of the season

It's snowing here on Dartmoor today...only lightly, but Tilly is thrilled nonetheless, and insists on going into the woods. Crossing over the stream, climbing up the hill, I follow my stalwart Animal Guide through tangles of holly, ash, and oak...

...leaving footsprints and pawprint to mark our passage into the green and white heart of winter.

The poem in the picture captions is from Emergences and Spinner Falls by Robert Haight (New Issues Poetry and Prose, 2002); all rights reserved by the author.

January 29, 2019

Working with words

I'm preparing a post on our last Modern Fairies session in Newcastle, and hope to have it ready for tomorrow. In the meantime I'd to revisit this piece on the magic inherent in words, as this was a subject that came up in discussions with the songwriters on the Modern Fairies project....

"Where words and place come together, there is the sacred," writes Kiowa poet and novelist N. Scott Momaday. "The question 'Where are you going?' is so commonplace in so many languages that it has the status of a universal greeting; it is formulaic. There is an American folksong that begins:

Well, where do you come from, and where do you go?

Well, where do you come from my cotton-eye Joe?

"The questions are so familiar that they are taken for granted. But their implications, their consequent meanings, are profound. In the deepest matter of these words are the riddles of origin and destiny, and by extension the stuff of story and ritual. I belong in the place of my departure, says Odysseus, and I belong in the place that is my destination. Only in this spectrum is the quest truly possible. The sense of place and the sense of belonging are bonded fast by the imagination. And words, in all their formal and informal manifestations, are the best expression of the imagination.

"Linguists have long suggested that we are determined by our native language, that language defines and confines us, " he notes. "It may be so. The definition and confinement do not concern me beyond a certain point, for I believe that language in general is practically without limits.

"We are not in danger of exceeding the boundaries of language, nor are we prisoners of language in any dire way. I am much more concerned with my place within the context of my language. This, I think, must be a principle of storytelling. And the storyteller's place within the context of his language must include both a geographical and mythic frame of reference. Within that frame of reference is the freedom of infinite possibility. The place of infinite possibility is where the storyteller belongs."

In an earlier interview, Momaday stated:

"Words are intrinsically powerful. And there is magic in that. Words come from nothing into being. They are created in the imagination and given life on the human voice. You know, we used to believe -- and I am talking about all of us, regardless of our ethnic backgrounds -- in the magic of words. The Anglo-Saxon who uttered spells over his field so that the seeds would come out of the ground on the sheer strength of his voice, knew a good deal about language, and he believed absolutely in the efficacy of language.

"That man's faith -- and may I say, wisdom -- has been lost upon modern man, by and large. It survives in the poets of the world, I suppose, the singers. We do not now know what we can do with words. But as long as there are those among us who try to find out, literature will be secure; literature will be a thing worthy of our highest level of human being."

Like Momaday, I believe that words have a magic and a power of their own, which those of us working in mythic arts and the fantasy field would be wise to remember. A good fantasy novel is literally spell-binding, using language to conjure up whole new worlds, or to invest our own with magic. The particular power of fantasy comes from its link with the world's most ancient stories, and from the author's careful manipulation of mythic archetypes, story patterns, and symbols.

A skillful writer knows that he or she must tell two stories at once: the surface tale, and a deeper story encoded within the tale's symbolic language. The magical tropes of fantasy, rooted as they are in world mythology, come freighted with meaning on a metaphoric level. A responsible writer works with these symbols consciously and pays attention to both aspects of the story.

In her fine book Touch Magic, Jane Yolen writes: "Just as a child is born with a literal hole in his head, where the bones slowly close underneath the fragile shield of skin, so the child is born with a figurative hole in his heart. What slips in before it anneals shapes the man or woman into which that child will grow. Story is one of the most serious intruders into the heart."

I believe that those of us who use the magic of words professionally should remember how powerful stories can be -- for children especially, but also for adults -- and take responsibility for the tenor of whatever dreams or nightmares we're letting loose into the world. This is particularly true in fantasy, where the tools of our trade include the language, symbolism and archetypal energies of myth. These are ancient, subtle, potent things, and they work in mysterious ways.

Words: The first passage by N. Scott Momaday is from The Man Made of Words: Essays, Stories, Passages (St. Martin's Press, 1997); the second passage is from Survival This Way: Interviews with American Indian Poets by Joseph Bruchac (Sun Tracks/U of Arizona Press, 1987). The poem in the picture captions is Momaday's "The Delight Song of Tsoai-talee" (Tsoai-Talee being one of Momady's own names), from In the Presence of the Sun: Stories and Poems, 1961-1991 (St. Martin's Press, 1991). All rights reserved by Momaday and Bruchac. Pictures: A magical encounter on our hill. Tilly is very good with these free-roaming Dartmoor ponies; she knows not to hassle or startle them...though sometimes they startle her.

Words: The first passage by N. Scott Momaday is from The Man Made of Words: Essays, Stories, Passages (St. Martin's Press, 1997); the second passage is from Survival This Way: Interviews with American Indian Poets by Joseph Bruchac (Sun Tracks/U of Arizona Press, 1987). The poem in the picture captions is Momaday's "The Delight Song of Tsoai-talee" (Tsoai-Talee being one of Momady's own names), from In the Presence of the Sun: Stories and Poems, 1961-1991 (St. Martin's Press, 1991). All rights reserved by Momaday and Bruchac. Pictures: A magical encounter on our hill. Tilly is very good with these free-roaming Dartmoor ponies; she knows not to hassle or startle them...though sometimes they startle her.

The power of language: Go here for previous posts on the subject, featuring Ben Okri, Jeanette Winterson, Jane Yolen and others; here for a short article by John Kelly on the rat-slaying poetry of the Irish bards; and here for an exploration of another form of language: the howling of wolves.

January 28, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm back home after two weeks on the road, and back in my hillside studio. My desk is piled high with work, my email Inbox is overflowing, and the pages of my neglected work-in-progress are glaring at me balefully...but the sun is shining, the birds are singing, and the hound lounges happily beside me, glad to return to normal routines. So let's start the week with some traditional ballads to put us all in a storytelling mood....

Above: "Lover's Ghost" (Child Ballad #272), performed by The Rosie Hood Trio. Rosie Hood is a singer/songwriter from Wiltshire, joined here by Nicola Beazley and Lucy Huzzard for a new video released last week.

Below: "The Bonnie Earl O' Moray" (Child Ballad #181) performed Said the Maiden (Jess Distill, Hannah Elizabeth, Kathy Pilkinton), a vocal harmony trio from Hertfordshire. The song can be found on their debut album, Here's a Health (2017).

Above: Said the Maiden again, performing "The Soldier and the Maid" (Child Ballad # 299).

Above: "False Lady: (Child Ballad #68) peformed by Teyr (James Gavin, Dominic Henderson, Tommie Black-Roff), from London. The song can be found on the trio's debut album, Far From The Tree (2016).

Abovee: "Banks of the Newfoundland," performed by Teyr. This one is a "capstan shanty" collected by Cecil Sharp in 1915, and may be related to the transportation ballad "Van Diemen's Land."

And last, an old performance from one of the primary bands of 20th century folk revival: "The Lady of Carlisle" (also known as "The Lion's Den") performed by Pentangle in 1972. Variants of this broadside ballad have been collected in Scotland, Ireland, Somerset, and the mountains of Kentucky.

For more information on Child Ballads go here, and on Broadside Ballads go here. The painting above is by Arthur Hughes (1832-1915).

January 22, 2019

Myth & Moor update

My apologies for the long pause in Myth & Moor posts and tweets. I've been on the road since last week, first with with the Modern Fairies project in Newcastle, and now catching up with friends, family, publishing colleagues, and Sir Edward-Burne Jones in London. (The B-J exhibition at the Tate is glorious beyond measure.)

I'll be back home and in the office on Monday, and have much to report....

January 14, 2019

Away with the fairies, once again

I'm currently on a train that's rolling from Dartmoor in south-west England to Newcastle in the far north-east, heading to the next Modern Fairies gathering at the Sage Theatre in Gateshead. I've been off-line due to health issues, but once again I am back on feet, a little shakey but up and moving, and I will do my best report on our journey into the Faerie Realm in the days ahead.

I love taking day-long train journeys, which hold a magic of their own, for time itself seems suspended in the liminal space between "here" and "there." As myth, folklore, and fairy tales remind us, the space between any two things is a traditional place of enchantment: a bridge between two banks of a river, the silvery light between night and day, the elusive moment between dreaming and waking, the instant of change in shape-shifting transformation ... and all those interstitial realms where cultures, myths, landscapes, languages, art forms, and genres meet. Modern Fairies was designed from the start as a cross-discipline, cross-genre project, so the cultural edgelands where we gather to work is the perfect place for summoning the Fair Folk.

I love taking day-long train journeys, which hold a magic of their own, for time itself seems suspended in the liminal space between "here" and "there." As myth, folklore, and fairy tales remind us, the space between any two things is a traditional place of enchantment: a bridge between two banks of a river, the silvery light between night and day, the elusive moment between dreaming and waking, the instant of change in shape-shifting transformation ... and all those interstitial realms where cultures, myths, landscapes, languages, art forms, and genres meet. Modern Fairies was designed from the start as a cross-discipline, cross-genre project, so the cultural edgelands where we gather to work is the perfect place for summoning the Fair Folk.

In some old tales, you must cross running water at least three times to enter into Faerieland. I crossed the River Exe early this morning, the River Aire moments ago, and will end the journey across the River Tyne. "We are often like rivers," writes Gretel Ehrlich, "careless and forceful, timid and dangerous, lucid and muddied, eddying, gleaming, still. Lovers, farmers, and artists have one thing in common, at least: a fear of 'dry spells,' dormant periods in which we do no blooming, internal droughts only the waters of imagination and psychic release can civilize."

The "waters of imagination" that run through Faerie are notoriously strange and dangerous, and one never quite knows just where they'll lead. We must carry salt and acorns in our pocket, wear hawthorne or rowan leaves in our hair, and we must not eat or drink the fairies' food. If we our wits about us, answer all riddles, mark our trail with feathers and stones, we'll come safely home again. Probably.

So now let's go. The gateway stands open. The moon is rising. I'll meet you there.

The art above is by Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, Alan Lee, and Charles Vess. To read previous posts on the Modern Fairies project, go here. You can follow the project through the Modern Faires website and blog, or on Twitter and Facebook.

January 6, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Morning

In a time of political discord, strife, and disconnection from the wider world, let's start the week grounded in harmony, community, and the wonders of the earth we share.

Above: "Rivermouth" by Rising Appalachia (Leah and Chloe Smith), based in the southern Appalachian region and New Orleans. The sisters are activists as well as musicians, working with Mississippi River, Gulf, and Klamath water protectors and other Waterkeepers around the world to preserve drinkable, fishable, swimmable water for everyone, everywhere. The song is from their sixth album, Wider Circles (2015).

Below: "Rang Tang Ring Toon" and "AGT" by Moutain Man, an Appalachian acappella trio (Molly Erin Sarle, Alexandra Sauser-Monnig, and Amelia Randall Meath). Both songs are from their second studio album, Magic Ship (2018).

Above: "Order and Chaos" by the English vocal harmony trip Lady Maisery (Hannah James, Hazel Askew, and Rowan Rheingans). The song is from their third album, Cycle (2016). The animation is by Minha Kim.

Below: "The Birds' Courting Song" by English vocal harmony trio Said the Maiden (Jess Distill, Hannah Elizabeth and Kathy Pilkinton), from their first album, Here's a Health (2017); and "Step Up, Speak Out," released by Rising Appalachia the same year.

Photographs: a favourite place of mine to retreat and write on the River Dart.

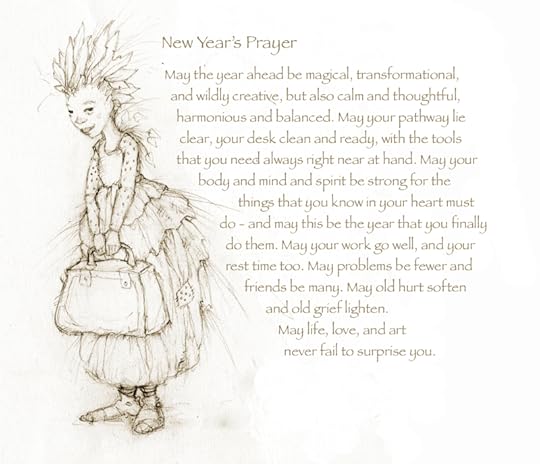

January 1, 2019

The turn of the calendar

Here in Chagford, the new year begins on a quiet, misty morning with sheep on the hills...

...ponies the fields...

...and Tilly at my side, as always.

On New Year's Day I'm always reminded of my favourite quote from L.D. Montgomery's Ann of Green Gables: Ann's practical and cheerful assertation that "every day is a new day without any mistakes in it yet."

My love of waking early is grounded in a similar attitude: each day begins as a bright clean slate and is thus an opportunity to work a little better, live a little better, perhaps make fewer mistake this time. (Or, as Samuel Beckett advised: "Try again. Fail again. Fail better.") Stepping into a new year is just the same, but a larger scale. It's a brand new year, with no mistakes in it yet.

I look forward to sharing it with you.

I've had some very kind requests to re-visit last year's New Year post: a reflection on the Pennsylvania Dutch folk customs my mother practiced on New Year's Day...and why she clung to them so tightly. You'll find the the piece here: "On the New Year and fresh starts."

The poem in picture captions above is from Words Under the Words by Naomi Shihab Nye (Far Corner Books, 1995). All rights reserved by the author.

December 31, 2018

Tunes for New Year's Eve

What could be better for Hogmanay -- the Scots word for the last day of the year -- than glorious music from the Band of Burns? The group, directed by Alastair Caplin, consistz of Adam Beattie, Rioghnach Connolly, Ellis Davis, Feilimi Devlin, Miley Kenney, John Langan, Ewan MacDonald, Lewis Murray, Dave Tunstall, Dila Vardar, and Chagford's own Dominie Hooper. These songs come Live from Union Chapel, a recording of a concert dedicated to the life and work of Robert Burns (1759-1796) last year.

The song above is ""Now Westlin Winds." Below, "Banks o'Doon."

Above: "John Anderson, My Jo."

Below: "One Hundred Years."

And to end: "Green Grow the Rushes."

As we cross the enchanted liminal space between the old year and the new, Tilly the Grumpy Reindeer and I wish you safe crossing, and much joy ahead. I'll be back in the studio, and back to Myth & Moor, on January 2nd.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers