Terri Windling's Blog, page 61

May 17, 2019

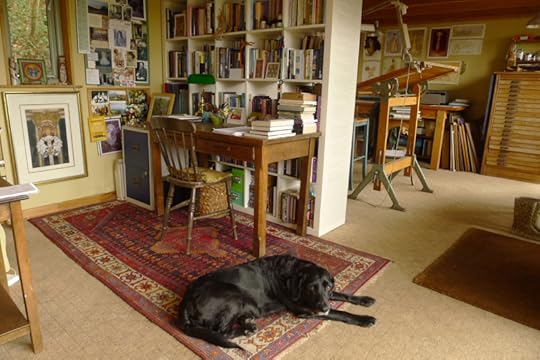

A quiet day in the studio

From an interview with Anthony Doerr (author of All the Light We Cannot See, etc.):

"Life is wonderful and strange, and it���s also absolutely mundane and tiresome. It���s hilarious and it���s deadening. It���s a big, screwed-up morass of beauty and change and fear and all our lives we oscillate between awe and tedium. I think stories are the place to explore that inherent weirdness; that movement from the fantastic to the prosaic that is life.

Words: The passage by Anthony Doerr is from an interview in Ways Revue. The poem in the picture captions is from The American Academy of Poets Poem-a Day, June 21, 2017. All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The small, cozy cabin where I work on a green hillside at the edge of the moor...and its resident hound.

May 16, 2019

Home again, home again

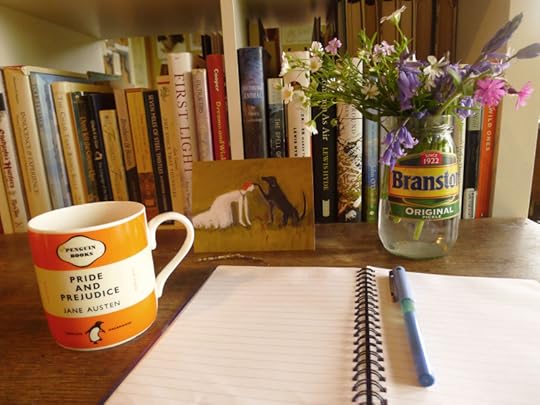

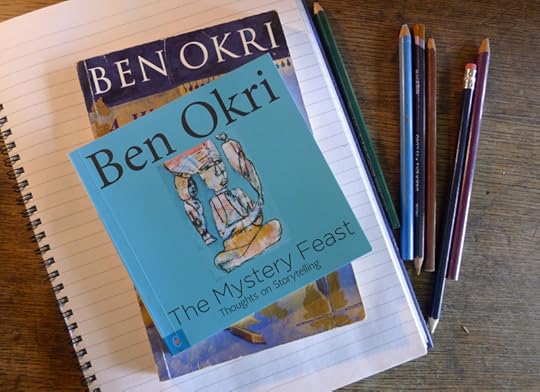

I'm back from a series of travels and adventures, and have many things to tell you about...but first I must catch up on all that I missed at home and work while I was away, and reassure my anxious Hound that I'm not heading off again anytime soon. As I unpack my bags, sweep the dust from the studio, and prepare to dive back into  my manuscript-in-process, I've been re-reading these bracing words from Ben Okri's The Mystery Feast:

my manuscript-in-process, I've been re-reading these bracing words from Ben Okri's The Mystery Feast:

"In ancient Africa, in the Celtic lands, storytellers were magicians," he says. "They were initiates. They understood the underlying nature of reality, its hidden forces. The old Celtic bards could bring out welts on the body with a string of syllables. They could heal sickness with a tale. They could breathe life into a dying civilization with the magic of a story.

"The historian deals with the past, but the true storyteller works with the future. You can tell the strength of an age by the imaginative truth-grasping vigour of its storytellers. Stories are matrices of thought. They are patterns formed in the mind. They weave their effect on the future. To be a storyteller is to work with, to weave with, the material of time itself."

"Storytellers," Okri urges, "reclaim the fire and sorcery of your estate. Take an interest in everything. You cannot be a magician in stories if you are not a magician in life. Go forward into the future, but also return to the secret gnosis of the bards.

"As the world gets more confused, storytellers should become more centered. What we need in our age are not more specialists and spin-doctors. What we need are people deeply rooted in the traditions of their art, but who are also at ease in the contemporary world.

"Storytellers are the singing conscious of the land, the unacknowledged guides. Reclaim your power to help our age become wise again."

Drawing by E.M. Taylor (1909-1999)

May 7, 2019

Heading north

Myth & Moor will be on hiatus for the next week and a bit, because I'll be on the road again.

This time, I'm heading up to Scotland for the Symposium for Fantasy & the Fantastic at the University of Glasgow (Friday, May 10) -- where I'll be giving the Keynote address on The Power of Storytelling: Re-creating the World Through Fantasy. It's is a subject I feel rather passionate about, and if you're anywhere near Glasgow, please do come. The talk is open to all (not just Symposium partipants), and the tickets are free but you need to book them as space is limited. You'll find more information here.

On May 11th & 12th, I'll be in Dungworth, Sheffield for a Soundpost folk music gathering, where several of us from the Modern Fairies project will be giving workshops on how to use folk tales as a source of creative inspiration in music, writing, and art. In the video below, Fay Hield explains all. Please join us if you possibly can.

I'll be back in the studio (and on-line again) on Thursday, May 16. I hope you all have a good, creative week.

Remember in the midst of dire news headlines and daily chaos that seeds are stretching upwards through the soil, bluebells are nodding in the wind, a fox slips by unseen in the shadows, and the world is still a magical place.

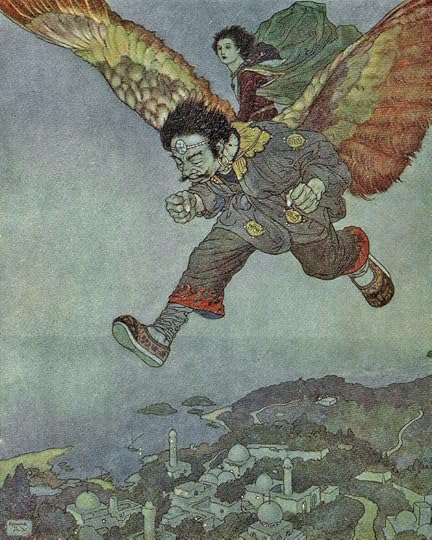

The painting above is "The East Wind" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953)

May 6, 2019

Tunes for a Monday Evening

Above: "The Foggy Dew" by Ye Vagabonds (brothers Br��an & Diarmuid Mac Gloinn), from Dublin, Ireland. The song appears on their fine new album, The Hare's Lament (2019).

Below: "Lath' a' siubhal sleibhe dhomh (On A Day As I Traversed The Mountain)" performed by Sarah-Jane Summers, a Scottish fiddler based in Norway. The song appears on her award-winning album Solo (2018).

Above: "House on a Hill" by singer-songwriter Olivia Chaney, from Oxford. It's from her beautiful new album, Shelter (2018).

Below: "Shelter," the title song from the new album.

Above: "The House at Rosehill" by singer/songwriter Claire Hastings, from Glasgow. The song appears on her second album, Those Who Roam (2016).

Below: "Keep it Whole" by singer/songwriter Anna Mieke, from Wicklow, Ireland. The song was released as a single last autumn; the video was filmed in Montana.

Drawing by William Heath Robinson.

April 24, 2019

The mnemonics of words on the Isle of Lewis

In his luminous book Landmarks, Robert Macfarlane writes about the interconnection of language and place on Lewis in the Outer Hebrides:

"Ultra-fine description operates in Hebridean Gaelic place-names, as well as in descriptive nouns. In the 1990s an English linguist called Richard Cox moved to northern Lewis, taught himself Gaelic, and spent several years retrieving and recording place-names in the Carloway district of Lewis's west coast. Carloway contains thirteen townships and around five hundred people; it is fewer than sixty square miles in area. But Cox's magnificent resulting work, The Gaelic Place-Names of Carloway, Isle of Lewis: Their Structures and Significance (2002), runs to almost five hundred pages and details more than three thousand place-names. Its eleventh section, titled "The Onimasticon,' lists the hundreds of toponyms identifying 'natural features' of the landscape. Unsurprisingly for such a martime culture, there is a proliferation of names for coastal features -- narrows, currents, indentations, projections, ledges, reefs -- often of exceeptional specificity. Beirgh, for instance, a loanword from the Old Norse, refers to ' a promontory or point with a bare, usually vertical rock face and sometimes with a narrow neck to land,' while corran has the sense of 'rounded point,' derived from its common meaning of 'sickle.'

"There are more than twenty different terms for eminences and precipices, depending on the sharpness of the summit and the aspects of the slope. S��thean, for example, deriving from s��th, 'a fairy hill or mound,' is a knoll or hillock possessing the qualities which were thought to

constitute desirable real estate for fairies -- being well-drained, for instance, with a distinctive rise, and crowned by green grass. Such qualities also fulfilled the requirements for a good sheiling site, and so almost all toponyms including the word s��thean indicates sheiling locations. Characterful personifications of place also abound: A' Gh��ig, for instance, means 'the steep slope of a scowling expression.'

"Reading 'The Onomasticon,' you realize that Gaelic speakers of this landscape inhabit a terrain which is, in Proust's phrase, 'magnificently surcharged with names.' For centuries these place-names have spilled their poetry into everyday Hebridean life. They have anthologized local history, anecdote and myth, binding story to place. They have been functional -- operating as territory markers and ownership designators -- and they have also served as navigational aids. Until well into the 20th century, most inhabitants of the Western Isles did not use conventional paper maps, but relied instead on memory maps, learnt on the island and carried in the skull.

"These memory maps were facilitated by first-hand experience and were also -- as Finlay [MacLeod] put it -- 'lit by the mnemonics of words.' For their users, these place-names were necessary for getting from location to location, and for the purpose of guiding others to where they needed to go. It is for this reason that so many toponyms incorporate what is known in psychology and design as 'affordance' -- the quality of an environment or object that allows an individual to perform an action on, to or with it. So a bealach is a gap in a ridge or cliff which may be walked through, but the element be��rn or beul in a place-name suggests an opening that is unlikely to admit human passage, as in Am Beul Uisg, 'the gap from which the water gushes.' Bl��r a' Chalchain means 'the plain of stepping stones,' while Clach an Line means 'rock of the link,' indicating a place where boats can be safely tied up. To speak out a run of these names is therefore to create a story of travel-- an act of naming that is also an act of wayfinding.

"Angus MacMillan, a Lewisian, remembers being sent by his father seven miles across Brindled Moor to fetch a missing sheep spotted by someone the night before: 'C��l Leac Ghlas ri taobh Sloc an Fhithich fos cionn Loch na Muilne.' 'Think of it,' writes MacMillan drily, 'as an early form of GPS: the Gaelic Positioning System.' "

The history and significance of place-names in land-based societies is something that those of us writing mythic fiction would do well to bear in mind -- whether we're working with myth or folktales born from a specific landscape, or creating an imaginary one.

"Invented names are a quite good index of writers' interest in their instrument, language, and ability to place it," says Ursula Le Guin. "To make up a name of a person or place is to open the way to the world of the language the name belongs to. It's a gate to Elsewhere. How do they talk in Elsewhere? How do we find out how they talk?"

Perhaps by knowing the land they walk. Which begins with knowing our own.

Words: The passage by Robert Macfarlane is quoted f rom Landmarks (Hamish Hamilton, 2015; Penguin Books, 2016). The passage by Ursula K. Le Guin is quoted from her essay "Inventing Languages," in Words Are My Matter (Small Beer Press, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from The Bonniest Companie by Kathleen Jamie (Picador, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures:.Not the moors of Lewis but of our own moor, Dartmoor, taken at

Scorhill, a bronze age stone circle not far from our village. The illustration is "Looking Into the Fairy Hill" by my friend & neighbor Alan Lee, from his now-classic book Faeries, with Brian Froud (Abrams, 1978). All rights reserved by the artist.

Silence and stillness on the Isle of Skye

In A Book of Silence, Sara Maitland explores the cultural history of silence and retreat while seeking to create more room for silence within her own life. It's a fascinating book, leading through myth, religion, philosophy, sociology, natural history and literature to a place of stillness at the center of them all. "In Silence there is eloquence," wrote the great Persian poet Jal��l ad-D��nRumi. "Stop weaving and see how the pattern improves."

Early on in her quest for silence, Maitland arranged to spend forty days alone at Allt Dearg, a remote cottage on the Isle of Skye in the Inner Hebrides, noting the changes in her psyche and imagination as the weeks went by and her silence and solitude deepened.

Describing the last days of her time on Skye, she says: "Part of me had already moved on from Allt Dearg, and another part of me never wanted to leave. The weather became appalling so that I could not go out for a final walk or round off the time with any satisfying sense of closure. I had to clean the house and then drive a long way. I had felt quite depressed for about forty-eight hours...

"...and then, the very final evening, I suddenly was seized with an overwhelming moment of jouissance. I wrote:

'They say it is not over till the fat lady sings. Well, she is singing now. She is singing in a wild fierce wind -- and I am in here, just. Now I am full of joy and thankfulness and a sort of solemn and bubbling hilarity. And gratitude. Exultant -- that is what I feel -- and excited, and that now, here, right at the very edge of the end, I have been given back my joy.'

"For several hours I enjoyed an extraordinary rhythmical sequence of emotions -- great waves of delight, gratitude, and peace; a realization of how much I had done in the last six weeks, how far I had traveled; a powerful surge of hope and possibility for myself and my future; and above all a sense of privilege. But also a nakedness or openness that needed to be honored somehow.

"I experienced a fierce joyful ... joyful what? ... neither pride nor triumph felt like the right word. Near the end of Ursula Le Guin's The Farthest Shore (the third part of The Earthsea Trilogy), Arren, the young prince-hero, who has with an intrepid courage born of love rescued the magician Sparrowhawk, and by implication the whole of society, from destruction, wakes along on the western shore of the island of Selidor. 'He smiled then, a smile both somber and joyous, knowing for the first time in his life, and alone, and unpraised and at the end of the world, victory.'

"That was what I felt like, alone on An t-Eilean Sgitheanach, The Winged Isle. I felt an enormous victorious YES to the world and to myself. For a short while I was absorbed in joy. I was dancing my joy, dancing, and flowing with energy. At one point I grabbed my jacket, plunged out into the wind and the storm. It was physically impossible to stay out for more than about a minute because the wind and rain were so strong and I came back in soaked even from that brief moment; but I came back in energized and laughing and exulting as well. I was both excited and contented. This is a rare and precious pairing. I knew, and wrote in my journal, that this would not last, but it did not matter. It was NOW. At the moment that now, and the enormous wind, felt like enough. Felt more than enough.

"And once again," she concludes, "I am not alone. Repeatedly, in every historical period, from every imaginable terrain, in innumerable different languages and forms, people who go freely into silence come out with slightly garbled messages of intense jouissance, of some kind of encounter with nature, their self, their God, or some indescribable source of power."

It was interesting reading Maitland's fine book while I was confined to bed with health problems. With Tilly snuggled close beside me, I was not entirely alone -- but the quiet and stillness of recovering from an illness can be another form of retreat from the rapid rhythms of the noisy modern world. There were long hours when the only sounds were Tilly's snores, the rustle of a book's turning page, rain or bird song outside the window glass. Like a spiritual retreat or pilgrimage, illness takes us deep inside ourselves, shaking away all other concerns except those of the body, those of the soul. Afterwards, I always return to life changed. The world is restored to me piece by piece, with each step noted and celebrated: the first hour out of bed; the first morning outdoors, tucked up in a blanket on the garden bench; the first slow climb to my studio on the hill; the first shaky walk in the woods with Tilly. There's a joy in all this that we rarely speak about, as if to admit that there's any pleasure or value in illness might be to dismiss its overwhelming difficulties. We'd all prefer, of course, to plan our times of retreat, not to have them forced upon us by physical collapse, not to have them come at the most disruptive of times, not to have them overshadowed by pain and fear. But there is a gift in the journey of illness: the gift of long hours of quiet and stillness. A gift that's increasingly precious and rare in our fast-paced society.

And, if we are prepared to except them, there are these further gifts as well: jouissance, wonder, and fresh gratitude for our fragile bodies, our fleeting lives, and the exquisite beauty of the world we return to.

Pictures: Tilly on our Devon coast (not so wild as Skye, but just as beautiful), and at the bedroom window. The magical "Healing Quilt" is by Karen Meisner. Words: The passage above is from A Book of Silence by Sara Maitland (Granta, 2009); all rights reserved by the author.

April 22, 2019

A language of land and sea

From Love of Country: A Hebridean Journey by Madeleine Bunting:

"Every nation has its lost histories of what was destroyed or ignored to shape its narrative of unity so that it has the appearance of inevitability. The British Isles with their complex island geography have known various configurations of political power. Gaelic is a reminder of some of them: the multinational empires of Scandinavia, the expansion of Ireland, and the medieval Gaelic kingdom, the Lordship of the Isles, which lost mainland Scotland, and was ultimately suppressed by Edinburgh. The British state imposed centralization, and insisted on English-language education. Only the complex geography of islands and mountains ensured that Gaelic survived into the 21st century.

"What would be lost if Gaelic disappeared in the next century, I asked, when I visited hospitable [Lewis] islanders who pressed me with cups of tea and cake. There is a Gaelic word, cianalas, and it means a deep sense of homesickness and melancholy, I was told. The language of Gaelic offers insight into a pre-industrial world view, suggested Malcolm Maclean, a window on another culture lost in the rest of Britain. As with any language, it offers a way of seeing the world, which makes it precious. Gaelic's survival is a matter of cultural diversity, just as important as ecological diversity, he insisted. It is the accumulation of thousands of years of human ingenuity and resilience living in these island landscapes. It is a heritage of human intelligence shaped by place, a language of the land and sea, with a richness and precision to describe the tasks of agriculture and fishing. It is a language of community, offering concepts and expressions to capture the tightly knit interdependence required in this subsistence economy.

"Gaelic scholar Michael Newton points out how particular words describe the power of these relationships intertwined with place and community. For example, d��thchas is sometimes translated as 'heritage' or 'birthright,' but conveys a much richer idea of a collective claim on the land, continually reinforced and lived out through the shared management of the land. D��thchas grounds land rights in communal daily habits and uses of the land. It is at variance with British concepts of individual private property and these land rights received no legal recognition and were relegated to cultural attitudes (as in many colonial contexts). Elements of d��thchas persist in crofting communities, where the grazing committees of the townships still manage the rights to common land and the cutting of peat banks on the moor. Crofting has always been dependent on plentiful labor and required co-operation with neighbors for many of the routine tasks, like peasant cultures across Europe, born out of the day-to-day survival in a difficult environment.

"The strong connection to land and community means that 'people belong to places rather than places belong to people,' sums up Newton. It is an understanding of belonging which emphasizes relationships, of responsibilities as well as rights, and in return offers the security of a clear place in the world."

Bunting also notes:

"Gaelic's attentiveness to place is reflected in its topographical precision. It has a plentiful vocabulary to describe different forms of hill, peak or slope (beinn, stob, d��n, cnoc, sr��n), for example, and particular words to describe each of the stages of a river's course from its earliest rising down to its widest point as it enters the sea. Much of the landscape is understood in anthropomorphic terms, so the names of topographical features are often the same as those for parts of the body. It draws a visceral sense of connection between sinew, muscle and bone and the land. Gaelic poetry often attributes character and agency to landforms, so mountains might speak or be praised as if they were a chieftain; the Psalms (held in particular reverence in Gaelic culture) talk of landscape in a similar way, with phrases such as the 'hills run like a deer.' In both, the land is recognized as alive.

"Gaelic has a different sense of time, purpose and achievement. The ideal is to maintain an equilibrium, as a saying from South Uist expresses it: Eat bread and weave grass, and then this year shall be as thou wast last year. It is close to Hannah Arendt's definition of wisdom as a loving concern for the continuity of the world."

And, I would add, to the Dineh (Navajo) concept of h��zh��, or Walking in Beauty.

Words: The poem in the picture captions is by Kathleen Jamie, from the Scottish Poetry Library. I highly recommend her poetry volumes, and her two gorgeous essay collections: Findings and Sightlines. The passage above is from Love of Country by Madeleine Bunting (Granta, 2016), also recommended. All rights to the prose and poetry in this post is reserved by the authors. Pictures: The Fairy Glen near Uist, Isle of Skye.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Since we were speaking of lives and literature from remote islands last week, I'd like to start the new week with music from some of those same islands. (I apologise for the lack of posts at the end of last week -- I've been down with health problems yet again.)

Above: "Dh�����irich mi moch, b' fhe��rr nach do dh�����irich" by singer/songwriter Julie Fowlis, from North Uist in the Outer Hebrides. The song appears on her beautiful and rather magical album Alterum (2017).

Below: Singer Ellen MacDonald discusses her maternal ties to North Uist and Scalpay during the recording of The Hebridean Sessions with the G��idhealtachd band D��imh. Though born and raised on the mainland (in Inverness), Macdonald studied at Sabhal M��r Ostaig, the Gaelic language college on the the Isle of Skye.

Above: "The Wren and the Salt Air," a song written by Jenny Sturgeon (of Salt House and Northern Flyway) while on St Kilda in the Outer Hebrides. This haunting piece is one of four works commissioned by the National Trust for Scotland to celebrate the 30th anniversary of St Kilda's designation as a World Heritage Site for Nature. Sturgeon trained as a biologist as well as a musician, and many of her exquisite songs evoke various aspects of the natural world. On this one, she's backed up by field recordings of St Kilda wrens, plus Pete MacCallum on guitar.

Below: "An L��imras/Harris Dance" by Brighde Chaimbeul, a young pipe and whistle player who grew up in a musical family on the Isle of Skye in the Inner Hebrides. The tune comes from Chaimbeul's debut album The Reeling (2019). The video was filmed by D��mhnall E��ghainn MacKinnon over the Isle of Harris in the Outer Hebrides.

Above: "Louise's Waltz" by Chris Stout and Catriona McKay, an award-winning folk duo from Shetland. The song appears on their album Bare Knuckle (2017).

Below: "Three Fishers" performed by Fara (Jennifer Austin, Jeana Leslie, Catriona Price, and Kristan Harvey), whose music is rooted in the distinctive fiddle style of Orkney. The song appears on their album Cross the Line (2017).

The Shetland and Orkney archipelagos lie off the northern coast of Scotland, and share musical influences from Scandinavia.

And something a little different to end with:

"Air F��ir an L��" by Niteworks (Ruairidh Graham, Allan MacDonald, Christopher Nicolson and Innes Strachan), a trad-electronica band from the Isle of Skye -- with vocals by Sian (Eilidh Cormack, Ellen MacDonald and Ceitlin Lilidh). The song is based on a 17th century poem by Mairi nighean Alasdair Ruaidh (Mary Macleod). It's from the band's strange but wonderful second album, also called Air F��ir an L�� (2018).

For more music from the islands of Scotland, see previous posts on the lost songs of St. Kilda, Jenny Sturgeon and Inge Thompson's Northern Flyway, the music of Salt House, the Songs of Separation project, and Hannah Tuulikki's Away with the Birds. Photographs above: The Isle of Skye, Inner Hebrides.

April 15, 2019

Writers and islands

Having lost my heart to the Hebridian islands off Scotland's west coast, I'm fascinated by islands' natural and cultural history. If you are too, I recommend David Brown's essay "Orwell's Last Neighborhood," a discussion of George Orwell's time on the remote island of Jura. "The conventional wisdom," writes Brown, "is that Orwell���s years on Jura killed him, nearly robbing the world of 1984. None of his biographers or friends seemed to consider that Jura, despite or because of its harshness, might have extended his life and given him the psychic space to imagine a place utterly unlike it."

Also of interest: "Island Mentality" by Madeleine Bunting, a short piece discussing Orwell and other writers drawn to the Hebrides, along with her book-length survey of the islands: Love of Country: A Hebridean Journey.

And finally, I recommend three good novels set in the Hebrides: Sarah Moss' darkly comic Night Waking (Granta, 2011), Anna Mazzola's darkly folkloric The Story Keeper (Headline, 2018), and Andrew Miller's beautifully-crafted historial novel Now We Shall Be Entirely Free.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week, Appalachian folk & American roots music played by musicians from both sides of the Atlantic....

Above: "I Must And Will Be Married," an American folk song from the Anglo-Scots tradition performed by Naomi Bedford and Paul Simmonds -- from their forthcoming album Singing It All Back Home: Appalachian Ballads of English and Scottish Origin. The album was produced by Ben Walker here in the UK, with contributions from Justin Currie, Rory McLeod and Lisa Knapp, and the great Shirley Collins. It will launch at the Cecil Sharpe House in London in June, so if you're anywhere nearby, keep an eye out for tickets. This is a great project to support.

Below: "The Spider and the Wolf," written and performed by Naomi Bedford and Paul Simmonds. It's from a previous album, A History Of Insolence (2015).

Above: "Gallows Pole" performed by American bluegrass musician Willie Watson, a founding member of Old Crow Medicine Show, from his solo album Folksinger, Vol. II (2017). This Appalachian song is related to the Anglo-Scots ballad "The Maid from Freed from the Gallows."

Below: "I'm On My Way," peformed by the brilliant bluegrass musician Rhiannon Giddens, from North Carolina, with Italian jazz musician Francesco Turrisi. The song will appear on their collaborative album There is No Other, due out next month.

Above: "Rain and Snow," an Appalachian ballad performed by American bluegrass musician Molly Tuttle and her band. This performance was recorded in Bristol, England, in 2016.

Below: "Jericho" by Mile Twelve, a five-piece bluegrass band from Boston (Evan Murphy, Catherine Bowness, Nate Sabat, Bronwyn Keith-Hynes and David Benedict). The song is from their new album, City on a Hill (2019).

Above: "All in One" by Copper Viper (Robin Joel Sangster and Duncan Menzies), an American bluegrass & British folk duo based in London. The song is from their new album, Cut it Down, Count the Rings (2018).

And to end with something just a little different: "Pipeline Swallowtails" by Sarah Louise, a 12-string guitarist from North Carolina who is half of the Appalachian folk duo House and Land. The song is from her strange and magical solo album, Deeper Woods (2018).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers