Terri Windling's Blog, page 39

April 20, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I woke today with the strong desire to hear the simple beauty of women's voices. As the UK begins its second month of Coronavirus lock-down, I send these songs our from our little "house on a hill" in Devon to yours....

Above: " House on a Hill" by English singer/songwriter Olivia Chaney. Born in Italy and raised in Oxford, this song was written and filmed in her family cottage in the North York Moors. It appears on her most recent album, Shelter (2018), which I love.

Below: "Waxwing," written by Alasdair Roberts and sung by Olivia Chaney, from The Longest River (2015).

Above: "Burlap String" by American singer/songwriter Courtney Marie Andrews, from Phoenix, Arizona. This song was filmed in Bisbee, an old mining town close to the Arizona/Mexico border. It's from her lovely new album Burlap String (2020).

Below: "Downtown Train" written by Tom Waits and sung by Courtney Marie Adams. It's from Come On Up To The House: Women Sing Waits (2019), which is a terrific album.

Above: "My Silver Net" by Scottish singer/songwriter Amy Duncan, based in Edinburgh. The song is from her album Undercurrents (2016), a favourite from that year.

Below: "Labyrinth" by Amy Duncan, from her fine new album of the same name (2019). The animated video is by Tracy Foster.

April 19, 2020

Myth & Moor update

Dear readers,

I'm afraid that images are still disappearing, reappearing, then disappearing again on previous posts. I hear that other sites on Typepad (Myth & Moor's blogging platform) are also having the same problem, and the company is working on fixing it. I hope it will be soon.

If it's our local piskies and goblins causing the chaos, they seem to have spread through the Typepad network now. Perhaps instead of coders and trouble-shooters we need a hedgewitch to put it all to rights....

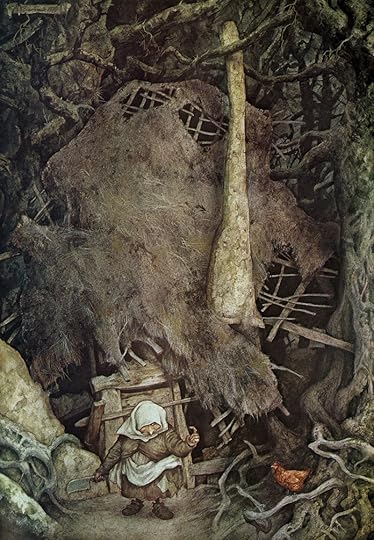

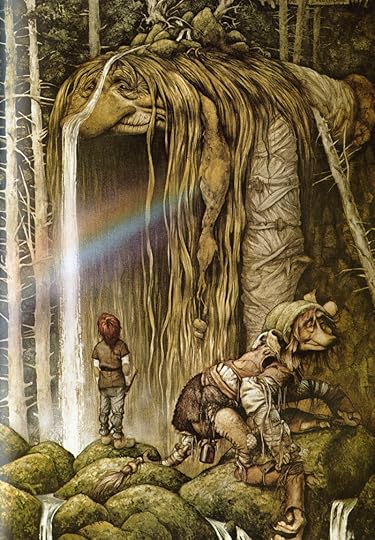

The art in this post (if it appears properly) is by my dear friends and village neighbours Brian Froud and Alan Lee, experts on the local fey folk. Follow the links if you'd like to read more about their work.

April 17, 2020

On a quiet day in the studio...

...Tilly snoozes on the sofa as I work, while outside the cabin's windows rain and mist has swallowed the world.

Friends keep asking, Are you and Howard all right? And the answer is, yes, we're doing okay. He's finding ways to do theatre work online, and for me, the days are much the same. A writer's life, or at least this writer's life, is one of semi-isolation anyway, for how else would the work get done? Here in my woodside studio, it's just me, Tilly, a blackbird calling, rain tapping on the cabin's tin roof as I tap words onto a laptop screen. The same thick mist that veils the hills also blots out everything beyond: the news, the noise, the gathering clouds of the world pandemic and economic collapse. It's there, but it's invisible, while I'm enfolded in fog and rain. Doing my work. Tapping out stories. And living with uncertainty as best as I can.

"Listen to me," Jean Rhys once said. "All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. And there are mere trickles, like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake. I don't matter. The lake matters. You must keep feeding the lake."

We are safe and well on our green hillside. Still working. Still feeding the lake.

The poem in the picture captions is from All of It Singing by Linda Gregg (Graywolf Press, 20018); all right reserved by the author.

April 16, 2020

Homemade ceremonies

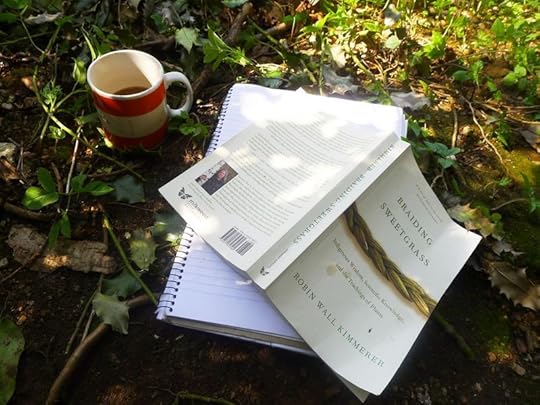

In Braiding Sweetgrass, Native American author and biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer (of the Potowatomi people) explains how her family was severed from their traditional culture when her grandfather, like so many children of his generation, was taken from home by the U.S. government and sent to the Carlisle Indian School to be "civilized" (a truly shameful chapter of my country's history). It was not until many years later that his descendants reclaimed their language and heritage. Against this painful background, Kimmerer writes movingly of her father's morning ritual when the family camped on the slopes of Tahawus each summer (the Algonquin name for Mount Marcy in the Adirondaks):

"When he lifts the coffee pot from the stove the morning bustle stops; we know without being told that it's time to pay attention. He stands at the edge of camp with the coffeepot in his hands, holding the top in place with a folded pot holder. He pours coffee on the ground in a thick brown stream. The sunlight catches the flow, striping it amber and brown and black as it falls to the earth and steams in the cool morning air. With his face to the morning sun, he pours and speaks into the stillness, 'Here's to the gods of Tahawus.' "

"I was pretty sure no other family I knew began their day like this, but I never questioned the source of those words and my father never explained. They were just part of our life among the lakes. But their rhythm made me feel at home and the ceremony drew a circle around our family. By those words we said, 'Here we are,' and I imagined that the land heard us -- murmured to itself, 'Ohh, here are the ones who know how to say thank you.' "

"Sometimes my father would name the gods of Forked Lake or South Pond or Brandy Brook Flow, wherever our tents were settled for the night. I came to know each place was inspirited, was home to others before we arrived and long after we left. As he called out the names and offered a gift, the first coffee, he quietly taught us the respect we owed these other beings and how to show our thanks for summer mornings.

"I knew that in the long-ago our people raised their thanks in morning songs, in prayer, in the offering of sacred tobacco. But at that time in our family history we didn't have sacred tobacco and we didn't know the songs -- they'd been taken away from my grandfather at the doors of the boarding school. But history moves in a circle and here we were, the next generation, back to the loon-filled lakes of our ancestors, back to the canoes....

"In the same way that the flow of coffee down the rock opened the leaves of the moss, ceremony brought the quiescent back to life, opened my mind and heart to what I knew, but had forgotten. The words and the coffee called us to remember that these woods and lakes were a gift. Ceremonies large and small have the power to focus attention to a way of living awake in the world. The visible became invisible, merging with the soil. It may have been a secondhand ceremony, but...I recognized that the earth drank it up as if it were right. The land knows you, even when you are lost.

"A people's story moves along like a canoe caught in the current, being carried closer and closer to where we had begun. As I grew up, my family found again the tribal connections that had been frayed, but never broken, by history. We found the people who knew our true names. And when I first heard in Oklahoma the sending of thanks to the four directions at the sunrise lodge -- the offering in the old language of the sacred tobacco -- I heard it as if in my father's voice. The language was different but the heart was the same.

"Ours was a solitary ceremony, but fed from the same bond with the land, founded on respect and gratitude. Now the circle drawn around us is bigger, encompassing a whole people to which we again belong. But still the offering says, 'Here we are,' and still I hear at the end of the words the land murmuring to itself, 'Ohh, here are the ones who know how to say thank you.' Today my father can speak his prayers in our language. But it was 'Here's to the gods of Tahawus' that came first, in the voice I will always hear. It was in the presence of ancient ceremonies that I understood that our coffee offering was not secondhand, it was ours."

The power of ceremony, writes Kimmerer,

"is that it marries the mundane to the sacred. The water turns to wine, the coffee to a prayer. The material and the spiritual mingle like grounds mixed with humus, transformed like steam rising from a mug into the morning mist. What else can you offer the earth, which has everything? What else can you give but something of yourself? A homemade ceremony, ceremony that makes a home."

I've written before about my own early morning ritual of climbing the hill up to my studio, and how I prefer to move in silence through the liminal space between waking up and creative work. We can draw parallels between the rituals of approach we employ to facilitate creative work and the morning ritual Kimmerer describes. Ritual, ceremony, meditation, creative routines and practices designed to ease us into work -- these are all means of acknowledging the transition from one state into another: from sleep into a brand new day, from morning chores and mundane concerns to the focused state of creativity and inspiration.

But there's also an important difference here -- which, I fear, often gets lost when First Nation ceremonies are too-casually adapted by non-Native peoples. While the coffee ritual may indeed have helped Kimmerer's father to feel more meditative, centered, and ready to start his day, this therapeutic aspect of the ceremony is not its purpose or focus. Rather, it is an act of gratitude, an acknowledgement of the larger world of which we humans are just one part. There is no ego in the ritual, no self-aggrandizing, no "look at me, look how spiritual I am" -- just the simple, humble act of a man offering a humble gift to creation.

In my own morning rituals, gratitude to the land, to our animal neighbors, to the vast nonhuman world plays a crucial part. It is why I write and why I paint: sheer gratitude for being alive, even on -- perhaps especially on -- those mornings when, because of poor health or other difficulties, life feels most burdensome. I want to create not from a place of ego and self-aggrandizement but as a means of gifting stories to the beautiful land that feeds and clothes and houses and sustains me; and to give, as Pablo Neruda once said, "something resiny, earthlike and fragrant in exchange for the gift of human brotherhood."

Some days I succeed, and some days I don't. But each morning I wake up, climb the hill with Tilly, pour steaming coffee from a silver thermos as birdsong greets the sun, and I try again. And again. And again. On the hill, I remember that my place in the world is very small. And very precious. And I'm grateful for it all.

Daily grace

In addition to "telling the holy" (as we were speaking about yesterday), I strive to "practice the holy" as well by living a life filled with rituals, large and small, that connect me to the land I live on and those I share it with -- expressing daily affinity and appreciation for it all. In her beautiful essay "Daily Grace," a discussion of rituals worldwide, cultural and ecological philosopher Jay Griffiths writes:

"No culture and few individuals live without ritual. There are the inaugurations of presidents, student graduations, the rituals of temples, mosques and synagogues, Christmas lights or Easter���s ritual opening of the doorway of spring. While large, public rituals might be vulnerable to commercialisation, tedium or cynicism, they can also be freighted with significance, and shine with what ��mile Durkheim in 1912 called the ���collective effervescence��� of ritual, a shared grandeur beyond the individual.

"For Indigenous Australians, ritual sings the natural world into continued life, in a diffuse and enspirited relationship between the Dreamtime ���past��� and the present. The Dreamtime surrounds the present, having created the landscape and order of the world, giving meaning and profundity to life and reflecting cosmic order, while rituals of the ���ordinary��� present, in turn, sustain the ���extraordinary��� Dreamtime order. In Bali, the ferocious flamboyance of the traditional cremation of a king unbuckled a terrible divinity from the very clouds: arrows that turn into flowers, coffins shaped like lions, snakes of cloth, doves flying from the foreheads of women committing ritual suicide. In his book Negara (1980), the cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz describes the lexicon of sensuous symbols in Balinese ritual, including carvings, flowers, dances, melodies, gestures, chants and masks, writing that the state rituals of classical Bali were ���metaphysical theatre: theatre designed to express���the ultimate nature of reality and���by presenting it, to make it happen���.

"Yet ritual is also alive in the slightest of phrases: a ���thank you��� that enhances gratitude; a ghost of a god in ���goodbye��� (god be with you); the grace spoken before eating. It is there in the little personal talismans touched a certain way for luck, because sometimes that one lucky strike of chance ��� before a journey, competition or meeting ��� is what ritual seeks to shelter, cradling the match to an Olympian flame. Given half a chance, habits seem to want to augment themselves into ritual: embellish a habit with attention, stylise it slightly, and it will elbow its way into the domain of rites, until even a cup of tea can be ceremonious.

"Tiny, everyday rituals are a hand-crafted prayer to domestic order, beckoning the divine to step inside a moment. In Bali, the making of the canang sari offerings is done individually but its effect is a collective efflorescence. Canang means a basket of flowers, while sari means essence, and what is essential, I was told, is the right intent, a kind of purity, paying heed to the scripture of the Bhagavad Gita in which Krishna describes what god requires of an offering: ���Whosoever offers to me with devotion a leaf, a flower, a fruit, or water, that offering of love, of the pure heart I accept.��� As in so many small rituals in so many cultures, an elemental grammar of nature is used: flowers suggest earth, candles suggest fire, then a little holy or purifying water, and the air is made visible by incense, with the ethereal element of prayer."

Like Griffiths, I find great meaning in personal rituals, both domestic and wild. When life is hard -- whether it's a personal hardship or the collective hardship of global pandemic -- the quiet beauty of daily ritual helps to center me within my own life, stripping away the swirl of fearful thoughts that might otherwise overwhelm me. I often think of these words by author Italo Calvino, who'd lived a harrowing life as an Italian Resistance fighter during World War II:

"Seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space."

Ritual, for me, is "not inferno," and I give it all the space I can.

In our modern, increasingly secular world we need ritual now more then ever, says Griffiths:

"Through the unregulated, unjust and unmetered use of resources, we have collectively created a cosmic disorder, and arguably the loss of ritual thinking is part of the reason. Some scholars argue that the loss of effective rituals leads to destructive behaviours, while the anthropologist Roy Rappaport in the 1990s called for a collective responsibility to ecological order, vitalised by ritualisation.

"To me, the most eloquent example of this is demonstrated by the Shinto priests at Lake Suwa in Japan who ritually recorded the lake���s freezing. As it froze, ridges of ice were formed and, when the world is viewed with twice-sight and nothing is only what it seems, the ice-ridges were seen as the footsteps of the gods. For 255 years, there were only three years when the lake did not freeze. Then between 2005 to 2014, there were five years when the lake didn���t freeze. Since 2013, it has frozen over just once, suggesting a terrifying planetary disorder. Confucius considered that ritual propriety guides humanity into authentic goodness (ren). ���If for a single day one were able to return to the observance of ritual propriety, the whole empire would defer to ren.���

"The sweet paradox of small daily rituals is that the ordinary is intensified into the sacred through the numinousness of the absolutely commonplace, an illustration of immanent divinity, demonstrating that all it takes to find cascades of enchantment is a tender attention in which the natural living world is blessed by the psyche, and the psyche by the natural world."

Or as the German philosopher Meister Eckhart wrote: "If the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough."

Words: The passage quoted above is from The poem in the picture captions is from "Daily Grace" by Jay Griffiths (Aeon Magazine, January 2019). I recommend reading the full essay here; and please consider supporting Griffiths' extraordinary work via her Patreon page. The poem in the picture captions is from Even in Quiet Places by William Stafford (Confluence Press, 2010). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The statue in our courtyard is by Wendy Froud. The drum was made by Munro Sickafoose, back in our Arizona days. The tree tied with rags is our local cloutie tree. To read more about clouties, go here. The pictures of me and Howard were taken last autumn before our annual hand-fasting ritual.

April 15, 2020

Myth & Moor update

Dear readers,

You may have noticed that images have been disappearing and reappearing from current and past posts. There is something wonky going on, and Typepad (Myth & Moor's blogging platform) is working on fixing it. Our apologies in the meantime.

Maybe the piskies and goblins are up to their tricks....

The art above is by my dear friends and village neighbours Brian Froud and Alan Lee, experts on the local fey folk.

Telling the holy

I keep returning to "Telling the Holy," Scott Russell Sanders' fine essay on myths and sacred stories from around the world. Each time I read it I find new things to ponder, and today it's this:

"Mystery is not much in favor these days. The notion that there are limits to what we can do, what we can know, limits to our dominion, does not sit well with kings and queens of the hill. Humility and reverence, we hear, are the attitudes of cowards. Why worship a force we can't measure on a meter? Why tell stories about a power we can't photograph?

"Flannery O'Connor once revealed to a correspondent that her 'gravest concern' was 'the conflict between an attraction for the Holy and the disbelief in it that we breathe in with the air of the times.' I feel that attraction for the holy, and my throat, too, burns with the air of disbelief.

"When the novelist Reynolds Price published his translation of stories from the Bible in a book called A Palpable God, he prefaced it with a long meditation on 'Origins and Life of Narrative,' in which he sought to explain why a cultivated person in our secular age might still take seriously these tales of the holy. The 'first -- and final -- aim of narrative,' he argued, is 'compulsion of belief in an ordered world.'

"Of course it would be reassuring to believe in an ordered world, say the sceptics. But what if the universe is chaotic, a hazard of bits and pieces, and our tales of order are but soothing lullabies we sing against the darkness?

"That line of reasoning leads to what I think of as the killjoy of sacred stories: they must be false because they are comforting. They are not, in fact, all comforting. Many are frightening. In myths, gods appear and disappear, play tricks, throw tantrums, devour the innocent and reward the wicked, bewilder the most patient seeker. The holy is often a holy terror. Still, the killjoy critique is forceful, as Reynolds Price acknowledged: 'Human narrative, through all its visible length, gives emphatic signs of arising from the profoundest need of one fragile species. Sacred story is the perfect answer given to the world to the hunger of the species for true consolation.'

"Mustn't so perfect an answer be an illusion? Not necessarily, Price added, 'for the fact that we hunger has not precluded food.' Water is nonetheless real for slaking our thirst, lovemaking nonetheless real for meeting our desire. I do not doubt the sun, even though it warms me and lights my way. Yes, tales about the holy may satisfy our craving for consolation, but that proves nothing about the truth of the tales or the reality of the power.

"The order we glimpse through myth is one that we did not create, that we cannot alter, that we can never fully grasp, and that we ignore at our peril. The achievements of science delude many into thinking that we have graduated from nature, that we can understand everything, that we can change or scorn conditions as we see fit, that we are bosses of the universe. Among those who resist this delusion of omnipotence are a number of scientists. The physicist Charles Misner, for example, has articulated a humbler view:

"'I do see the design of the universe as essentially a religious question. That is, one should have some kind of respect and awe for the whole business, it seems to me. It's very magnificent and shouldn't be taken for granted. In fact, I believe that is why Einstein had so little use for organized religion, although he strikes me as a basically very religious man. He must have looked at what the preachers said about God and felt they were blaspheming. He had seen much more majesty than they had ever imagined.'

By "mystery," Sanders clarifies,

"...I do not mean simply the blank places on our maps. I mean the divine source -- not a void, not a darkness, but an uncapturable fullness. We are sustained by processes and powers that we can neither fathom nor do without. I speak of that ground as holy because it is ultimate, it is what makes us possible, what shapes and upholds everything we see. The stories I am most interested in hearing, reading, and telling, are those that help us imagine our lives in relation to that ground."

And so am I. But for me, a certain kind of fantasy literature approaches the same ground as myth and sacred stories, albeit from a slantwise direction. Fantasy of this sort (Tolkien, Lewis, Le Guin, McKillip, Holdstock, Crowley, de Lint, Yolen, and numerous others) is all about mystery, and the magic inherent in life itself: the "processes and powers that we can neither see nor do without."

In our own myth-drenched, poetic, elvin-crafted way, we are telling the holy.

Sanders goes on to say:

"By telling the holy, we acknowledge that life is a gift. In fact, the whole universe is a gift. From where or what, and why, we cannot know. All we do know is that it issues forth, moment by moment, eon by eon, ever fresh, astounding in its richness and beauty. None of this is to gainsay the pain, the suffering, the eventual death that awaits all created things. But we measure that pain and suffering, we mourn that death against the sheer exuberant flow of things."

I want to work from that exuberant flow; to write of strange, improbable things that contain some kernal of truth within. I want to choose the winding road through the fernie brae that leads to mystery, wonder, and "miraculous grace" (to use Tolkien's phrase).

That is the road, I whisper to Tilly, where thou and I maun gae.

The quoted passage above is from "Telling the Holy" by Scott Russell Sanders, published in Wonder and Other Survival Skills, edited by H. Emerson Blake (The Orion Society, 2o12). The poem in the picture captions is from Even in Quiet Places by William Stafford (Confluence Press, 2010). All rights reserved by the authors.

April 14, 2020

Somewhere over the rainbow...

Tuesday morning note: My apologies for the pictures that aren't loading properly in this post. Typepad (this blog's platform) is aware of the problem, and I'm hoping it will be fixed soon. In the meantime, if you click on the links for the picture titles (Chagford rainbow 3, etc.), you'll see them.

Rainbows are proliferating in Chagford, as in many other parts of the world as well. Primarily drawn by children, they are a means of spreading cheer during the global pandemic, of expressing gratitude to our health workers, and of reaching out to friends and neighbours when social restrictions keep us physically apart.

The rainbow response to Covid-19 was begin by a group of mothers in northern Italy and then quickly spread to other virus-stricken nations, helping children to deal with all the stresses and changes that a medical lock-down has brought to their lives. In the UK, much of the rainbow art is addressed to our National Health Service, valiantly struggling to keep up with pandemic's demands despite years of underfunding (and may that finally change). The NHS was already associated with rainbow symbology due to the Rainbow Badge initiative begun last summer, affirming support for the LGBT community in hospitals all across Britain. The rainbow badges worn by health service staff now have double meaning, both of them poignant.

Here in Chagford, our days of pandemic lock-down have been brightened by two young artists on our the road, creators of the gorgeous rainbow drawings pictured in this post. This wonderful artwork makes me smile every time I go past on my walks with Tilly -- and thus the rainbows are doing exactly what they're intended to do: lifting spirits, and reminding us that even in Covid-19 isolation we are still a community.

In myth and folklore, the symbolism of rainbows shimmers with elusive enchantment. Mysterious and ephemeral, appearing and disappearing in the blink of an eye, rainbows in stories around the globe are magical pathways to Somewhere Else: the spirit world, the Faerie realm, the lands of the dead or the palaces of the gods.

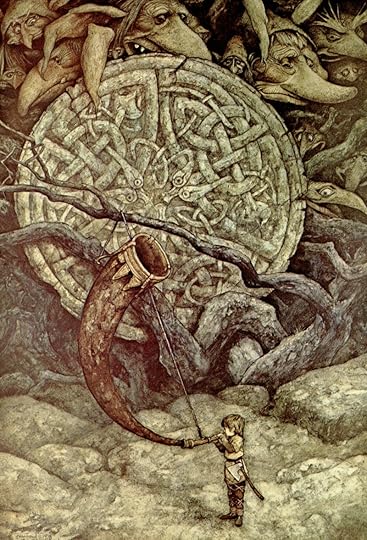

In Norse myth, Eddic Bifr��st is a rainbow bridge built by the gods themselves, leading to their home in Asgard. Heimdallr, with his Gjallarhorn ("yelling horn") stands guard at the place where the flaming rainbow bridge meet the clouds. Its heat is what keeps the frost giants out -- but at Ragnar��k the tri-coloured flames will cool, and the bridge into Asgard will stand open.

In Greek myth, the rainbow is personified as Iris, daughter of Thaumus (an ocean god) and Electra (a sea nymph), married to Zephyrus (god of the west wind). Iris prefigured Hermes in her role as the messenger of the gods, moving swiftly and easily between the mortal, immortal, and deathly realms. She has golden wings, which light the way on her passages through the underworld, and a coat of many colours, with which she creates the rainbows she travels on. Accordingly, the sight of a rainbow tells you that Iris is passing by.

The "rainbow serpent" is a sacred figure in disparate cultures around the world, from the indigenous peoples of North and South America to equatorial Africa, Australia, Malaysia, and ancient Persia. In Arabian tales, various gods, djinns, and culture heroes carry bows or swords made of the rainbow's colours; in Siberian lore, all rainbows belong to the thunder god, forming his hunting bow; while in Slavonic myth, rainbows make up the tri-coloured belt of the Mother Goddess (or, later, the Virgin Mary).

In Irish folklore, following a rainbow to its end leads to a pot of faery gold, while here in Devon it leads into Faerie itself -- but this is rarely depicted as a wise journey for a mortal man or woman to make. Leave it to the hares, who are quick enough to carry the Faerie Queen's messages on an unreliable road made of magic, raindrops, and light. Or, if you must travel over the rainbow and into the Good Folks' realm, be sure to carry salt or hawthorn berries in your pocket to bring you back home again.

In addition to traditional stories and legends, we all have our own personal lore and symbolism, accumulated throughout lives. Rainbows are part of my own mythic iconography, and this is the tale:

When I was 15, I sat in despair one day in a creaky old bus that was winding its way through central Mexico (that's another story), trying to decide if I truly believed in God. Not necessarily God with a big white beard looking down from a Biblical heaven, but some kind of sacred spirit above, beneath, and within all things. I'd aways had a deep, instinctive faith, even as a small child, in a sacred dimension to life, a Mystery I didn't need to fully define in order to know it, feel it, experience it. But recent gruelling events had shaken my faith and closed that connection.

I realize that sitting and railing at God is a perfect cliche of teenage angst -- but that doesn't make the experience any less urgent at age 15, and I was in a dark place. "Okay," I said, throwing the gauntlet down to whatever out there might be listening, "if there is something more than this, then prove it. Just prove it. Or I quit." The bus turned a corner on the narrow, dusty road, and a gasp went up from the people around me. Above us, a rainbow arched through a bright blue, cloudless, rainless desert sky.

Rainbows have been special to me ever since. I know the scientific explanation, of course, water and air and angles of sunlight and all that. But to me, they are always a message. They say: "The universe is a Mystery and you're part of it."

And sometimes that's all I need to hear; that's all the answer I need, no matter what the prayer.

The rainbow drawings on our road were photographed by Lunar Hine (editorial assistant here at the Bumblehill Studio) -- all except for the fourth photograph, which was taken by Claire-Shauna Saunders. I'm grateful to both of them for allowing me to use their pictures.

Lunar's daughters are the street artists -- and I'm grateful to them as well, for creating such beauty in troubled times, and sharing it with all of us.

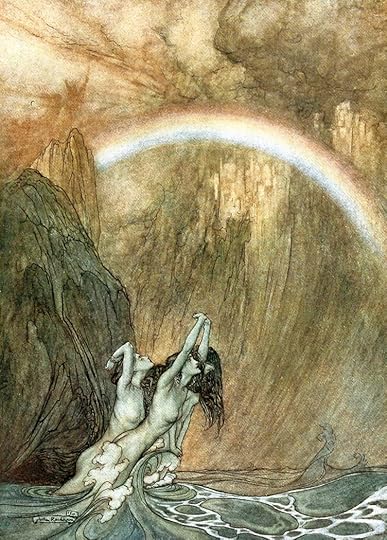

The illustrations, in order, are: Rhinemaidens (under the rainbow bridge to Asgard) and a rainbow nymph by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). A rainbow fairy by Willy Pogany (1882-1955). And a rainbow image of our local Dartmoor trolls by Brian Froud -- who knows them better than anyone.

April 13, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm starting my week with American music rooted in the Appalachian, bluegrass, blues, and gospel traditions. At troubled times, it's just good to hear songs from home....

Above: "Am I Born to Die" by husband-and-wife banjo masters B��la Fleck and Abigail Washburn, from their first duo album B��la Fleck & Abigail Washburn (2014). Washburn is from Illinois and D.C., and Fleck from New York City.

Below: "Don't Let It Bring You Down," from their second duo album, Echo in Valley (2017).

Above: "Don't Let Nobody Get You Down," a classic by blues musician Eric Bibb, performed in Maryland in 2008. Bibb grew up in New York City in a family of musicians and civil rights activists, and now makes his home in Stockholm, Sweden.

Below: "With My Maker," from Bibb's fifteenth solo album, Booker's Guitar (2010).

Above: "I'm On My Way" by bluegrass musician Rhiannon Giddens, from North Carolina, with Italian jazz musician Francesco Turrisi. The song appeared on their collaborative album There is No Other (2019).

Below: "Cuckoo Song" by Rising Appalachia (sisters Leah and Chloe Smith), from Georgia and New Orelans. The song appeared on their seventh album Leylines (2019).

Above: "Louise" by Mipso (Jacob Sharp, Wood Robinson, Joseph Terrell, and Libby  Rodenbough), from North Carolina. The song appeared on their first album, Dark Hollow Pop (2013).

Rodenbough), from North Carolina. The song appeared on their first album, Dark Hollow Pop (2013).

Below: Gillian Welch's beautiful song "Hard Times" covered by bluegrass mandolin master Chris Thile, with Emily King, Rich Dworsky, Chris Eldridge, Brittany Haas, Paul Kowert, and Ted Poor. Hard times ain't gonna rule my mind no more....

April 12, 2020

Morning has broken

Happy Easter to all of you who celebrate it, and happy springtime to all of you don't. Sadly, the Easter Sunrise Service usually held on the hill behind our house did not take place due to the UK's pandemic lockdown, but here's a post about it from a previous year. Tilly and I made the climb up the hill by ourselves this morning, and said our own quiet prayers....

The ancient church at the heart of our village hosts an annual Easter Sunrise Service -- held on the top of Nattadon, the tall hill just behind our house. I happened to wake very early on Easter morning, so while the rest of the family slept I dressed in my warmest jumper and skirt, laced on my studiest walking boots, whistled for Tilly, and headed out in the cold and dark.

We climbed through the oaks of Nattadon Woods and onto the open slope of the hill, the rain-rutted pathway grown visible now in the indigo light of dawn. Tilly raced ahead while I straggled behind, stopping often to catch my breath. During better times, the hound and I climb Nattadon almost every day, bounding up and down like mountain goats -- but health problems over the last several weeks have kept me on lower, easier trails. I was sorry to see how much strength I had lost as I wound my way slowly upward.

At last we reached the top of the hill. A number of people were gathered there, sharing tea and coffee and hot-cross buns, while a small fire blazed and the sun slowly rose behind clouds laying thick on the moor. *

It touched me to receive a warm welcome, despite not being Christian myself. I thought about all the centuries in which a pagan woman like me would have much to fear from the Christian church -- and so, as the Easter Service began and I silently added my own form of prayer, I felt a bone deep gratitude for this moment of inter-faith fellowship. A long time coming (historically speaking), hard won and precious. May it always be so.

The hymn chosen for the service was one I love: "Morning Is Broken" by Eleanor Farjeon. Yes, the same Eleanor Farjeon who wrote The Glass Slipper (a classic retelling of Cinderella) and other works of children's fiction.

I first knew the song through Cat Stevens' version in 1970, when I was growing up in north-east America, and it has personal significance. There were nights as a child when I could not sleep at home due to my stepfather's violence, so I'd sleep instead somewhere outdoors (if the weather was warm enough), or in the family car (if it was cold) -- sometimes alone, and sometimes with my young brothers curled up beside me. I've always been an early riser, and many a morning as the sky lightened I'd sing "Morning Has Broken" to cheer myself up. Back then, I could not have imagined I'd also sing it one day in the hills of south-west England, with my neighbors around me, my good dog beside me, my husband and daughter fast asleep in our warm little house below....

Yes, reader, I cried. I admit it.

Morning had broken. And we headed home.

A solitary Easter morning on Nattadon Hill during the global pandemic of 2020:

* I didn't photograph the Sunrise Service, or the people attending, in respect of privacy and the sacred nature of the event. These pictures of the fire were taken afterwards, with the Vicar's permission.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers