Terri Windling's Blog, page 38

April 29, 2020

The folklore of nettles

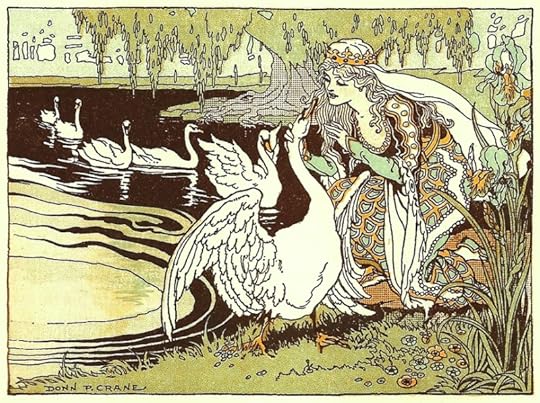

In the fairy tale of "The Wild Swans" by Hans Christian Andersen, the heroine's brothers have been turned into swans by their evil stepmother. A kindly fairy instructs her to gather nettles in a  graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

This was one of my favorite stories as a child, for I too had brothers in harm's way, and I too was a silent sister who worked as best I could to keep them safe, and sometimes succeded, and sometimes failed, as the plot of our lives unfolded. The story confirmed that courage can be as painful as knitting coats from nettles, but that goodness can still win out in the end. Spells can broken, and gentle, loving persistence can be the strongest magic of them all.

I grew up with the story, but not with Urtica dioica: "common nettles" or "stinging nettles." I imagined them as dark, thorny, and witchy-looking -- and although they're actually green and ordinary, growing thickly in fields and hedges here in Devon, nettles emerge nonetheless from the loam of old stories and glow with a fairy glamour. It is a plant that heralds the return of spring, a tonic of vitamins and minerals; and also a plant redolent of swans and spells, of love and loss and loyalty, of ancient powers skillfully knotted into the most traditional of women's arts: carding, spinning, knitting, and sewing.

According to the Anglo-Saxon "Nine Herbs Charm," recorded in the 10th century, sti��e (nettles) were used as a protection against "elf-shot" (mysterious pains in humans or livestock caused by the arrows of the elvin folk) and"flying venom" (believed at the time to be one of the four primary causes of illness). In Norse myth, nettles are associated with Thor, the god of Thunder; and with Loki, the trickster god, whose magical fishing net is made from them. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are fairy dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against fairy mischief, black magic, and other forms of sorcery.

Nettles once rivalled flax and hemp (and later, cotton) as a staple fiber for thread and yarn, used to make everything from heavy sailcloth to fine table linen up to the 17th/18th centuries. Other fibers proved more economical as the making of cloth became more mechanized, but in some areas (such as the highlands of Scotland) nettle cloth is still made to this day. "In Scotland, I have eaten nettles," said the 18th century poet Thomas Campbell, "I have slept in nettle sheets, and I have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The young and tender nettle is an excellent potherb. The stalks of the old nettle are as good as flax for making cloth. I have heard my mother say that she thought nettle cloth more durable than any other linen."

"Nettles have numerous virtues," writes Margaret Baker in Discovering the Folklore of Plants. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin; the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness.

"Mixing medicine and magic, a healer could cure fever by pulling up a nettle by its roots while speaking the patient's name and those of his parents. Roman soldiers in damp Britain found that rheumatic joints responded to a beating with nettles. Tyroleans threw nettles on the fire to avert thunderstorms, and gathered nettle before sunrise to protect their cattle from evil spirits."

The medicinal value of nettles is confirmed by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal in their useful book Hedgerow Medicine:

"Nettle was the Anglo-Saxon sacred herb wergula, and in medieval times nettle beer was drunk for rheumatism. Nettle's high vitamin C content made it a valuable spring tonic for our ancestors after a winter of living on grain and salted meat, with hardly any green vegetables. Nettle soup and porridge were popular spring tonic purifiers, but a pasta or pesto from the leaves is a worthily nutritious modern alternative. Nettle soup is described by one modern writer as 'Springtime herbalism at one of its finest moments.' This soup is the Scottish kail. Tibetans believe that their sage and poet Milarepa (AD 1052-1135) lived solely on nettle soup for many years until he himself turned green: a literal green man.

"Nettles enhance natural immunity, helping protect us from infections. Nettle tea drunk often at the start of a feverish illness is beneficial. Nettles have long been considered a blood tonic and are a wonderful treatment for anaemia, as they are high in both iron and chlorophyll. The iron in nettles is very easily absorbed and assimilated. What cooks will tell you is that two minutes of boiling nettle leaves will neutralize both the silica 'syringes' of the stinging cells and the histamine or formic acid-like solution that is so painful."

Here's our family recipe for Bumblehill Nettle Soup, which is easy to make and delicious:

First, pick your nettles by pinching off the fresh leaves at the tip of the plant, leaving the plant itself intact. It's best to do this in  the spring when the plants are young and the vitamin content at its highest, before the flowers appear. Rinse your nettle tips in cold water, and cut off any woody bits or thick stems. You need to wear gloves while you handle them, but once the nettles are cooked you can safely eat them without any stinging.

the spring when the plants are young and the vitamin content at its highest, before the flowers appear. Rinse your nettle tips in cold water, and cut off any woody bits or thick stems. You need to wear gloves while you handle them, but once the nettles are cooked you can safely eat them without any stinging.

Melt some butter in the bottom of the soup pot, add a chopped onion or two, and cook slowly until softened.

Add a litre or so of vegetable or chicken stock, with salt, pepper, and any herbs you fancy.

Add 2 large potatoes (chopped), a large carrot (chopped), and simmer until almost soft. If you like your soup thick, use more potatoes.

Throw in several large handfuls of fresh nettle leaves, and simmer gently for another 10 minutes.

Add some cream (to taste), and a pinch of nutmeg. Pur��e with a blender, and serve. (If you happen to have some truffle oil in your pantry, a light sprinkling on the soup tastes terrific.) Use the left-over nettles for tea, sweetened with honey.

You can also throw young nettle leaves into pancake, crepe, scone, biscuit, and bread recipes -- just rinse them, chop them, and blanch them in boiling water (to get the sting out) first. Below, for example: savoury squares of nettle-and-herb flatbread with sea salt, and sweet nettle pancakes.

Nettles, folk tales around the world agree, have long been associated with women's domestic magic: with inner strength and fortitude, with healing and also self-healing, with protection and also self-protection, with the ability to "enrich the soil" wherever we have been planted. Nettle magic is steeped in dualities: both fierce and soft, painful and restorative, common as weeds and priceless as jewels. Potent. Tenacious. Humble and often overlooked. Resilient.

And pretty tasty too.

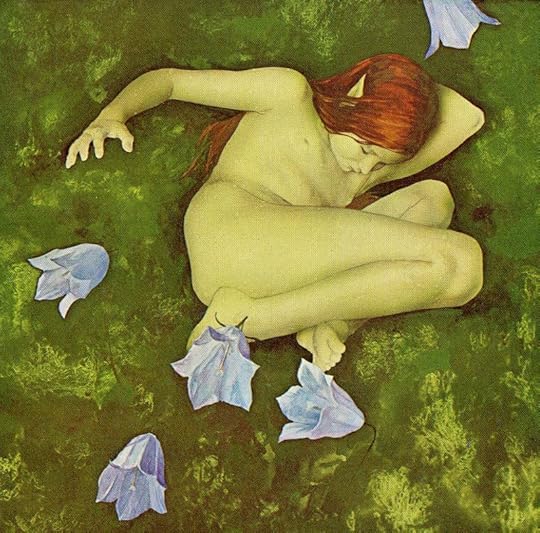

Pictures: The illustrations for "The Wild Swans" fairy tale are by Nadezhda Illarionova, Susan Jeffers, Mercer Mayer, Eleanor V. Abbott, Yvonne Gilbert, and Donn P. Crane. The Nettle Coat is by Alice Maher. Words: The quoted passages are from Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008) and Hedgerow Medicine by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal (Merlin Unwin Books, 2008). All rights reserved by the artists and authors.

Related posts: The folklore of food, and, for more on the Wild Swan fairy tale, Swan's wing. I've written about my personal connection to the fairy tale in "Transformations," but I must give you fair warning that this essay is a dark one.

More folklore of the wild flowers

As the pandemic lockdown rolls on, I want to share our blossoming countryside with all of you confined to urban or less wild spaces, along with a little more of the wildflower lore that's rooted in the land below our feet. I love knowing and passing on such things. "Re-storying" the land is, I believe, an important part of re-wilding the land, re-wilding our culture, and re-wilding ourselves.

In the springtime, writes herbalist Judith Berger,

"the earth herself seems overtaken with desire to create for the sake of beauty and joy, unveiling at an astounding rate those creations which were conceived and protected in winter's ground-dark womb. Young, delectable leaves shoot up out of the soil, becoming clorophyll-rich as they soak up the food of the sun's fire. Food and medicine plants carpet the ground abundantly, delighting the eyes and tastebuds with a palette of green hues and an array of distinctive earthy flavors. Daily, as light seeps into the unfurling leaves, the plants grow greener and greener with the blood of the sun. As we ingest these plants, we increase our inner fires and pulse with the blood of life, thus inspired to move through our days with the same abandon as the maiden goddess of spring."

Stitchwort (below), appears in Devon in two distinctive colors: white and pink. Greater stitchwort, with its white star-like blooms, also goes by the name star flower, thunder flower (because picking it will cause a storm), Mother Shimbles, snick needles, and snapjacks (due to the popping sound made by its seed pods as they ripen). Lesser stitchwort, with its small pink flowers, is known as piskie, or piskie flower, here in Devon -- though in fact both kinds of stitchwort are under the special protection of the piskies (our local faery folk). They zealously guard the flowers against hedgewitches, who use them for making medicines and charms of protection against piskie mischief -- including a salve that heals the "side stitches" caused when mortals are hit by elf-shot.

Stitchwort often grows among stands of nettles -- which is certainly one way to protect it from being picked. Nettles themselves are a wonderful plant (despite their sting), prized by witches, cunning men, herbalists, and wild food foragers. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are faery dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against faery enchantment, black magic, and other forms of sorcery. Historically, nettles have had a wide variety of uses, from making medicines to making cloth. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin," notes folklorist Margaret Baker; "the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness." Today, many of us still harvest the tender top leaves of nettles in the spring. Rich in iron and vitamins, they are an excellent tonic for the immune system when cooked in soups and stews, or brewed for tea.

(We'll take a closer look at the folklore of nettles in tomorrow's post.)

Germander speedwell ( above), also known as birds-eye or angels-eye, is a flower associated with vision, with magical oinments allowing mortals to see faeries, and with healing afflictions of the eyes -- whether medical or caused by witchcraft. Although largely unmentioned by modern herbalists, it was once considered a valuable plant in hedge-lore here in the West Country. A tea made from its leaves and flower petals is said to be good for coughs (when brewed at strength), or settling the nerves (when brewed more delicately), while also fostering clarity of vision, focus, and purpose.

According to Welsh folklore, wild Welsh poppies (above) don't flourish outside Wales itself -- but in fact they are ubiquitous here in the West Country, and in other parts of the British Isles too. Perhaps they are bigger and brighter in Wales...?

Although the Welsh poppy (Meconopsis cambrica) is somewhat different than the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), it too is associated with sleep, dreams, the spirit world, and various forms of divination. Yellow poppies must never be brought into the house -- they will cause headaches, storms, or lightning strikes -- but wild poppy seeds placed under a pillow will show a young man or maid their future lover's face, or give the dreamer the answer to any question posed while falling asleep. The seeds can also be carried in one's pocket, or strewn in a circle around one's home, to provide protection from faery enchantments, especially those that cause confusion or memory loss.

The cuckoo flower (above) is said to herald the first cuckoo of spring. It grows in damp, grassy meadows and bogs, its petals tinted pink or lavendar, and is also known by the names lady's-smock, milkmaid, May flower, and fairy flower. Associated with the revels of May, hedgewitches used various parts of the plant for love potions and fertility spells -- as well as for the opposite: charms intended to keep love and fertility at bay. Cuckoo flower teas and tonics restored appetites diminished by poor health, while also aiding digestion, treating survy, and easing bowel complaints. The leaves, when young, are edible, tasting peppery, like cress.

In the folk tradition of the West Country, buttercups (above) are a benificent plant -- associated with the sun, yellow butter and the dairy, and ease in domestic labor. On May Day, farmers rubbed the udders of their cows with buttercup flowers to increase the yield and richness of their milk; this also protected them from theft by faeries -- who were always eager to improve their herds of fairy cattle by interbreeding with cows from mortal fields. Buttercups are toxic to ingest so medicinal use of the plant is limited, although some old herbals suggest that a poulstice made of the crushed flowers and leaves is helpful in relieving colds, coughs, and bronchial complaints. "Buttercup water," made by infusing the flower petals in water heated by the sun, was used to bathe sore eyes, and "sweeten" the complexion. Buttercups are part of Rananculus family, related to spearwort, crowfoot and lesser celandine. It was once believed that swallows fed their young on a diet of these flowers, giving them prophetic abilities and clear sight.

Red campion (above and below) -- also known as ragged-robin or robin flower -- is associated with Robin Goodfellow (or Puck), a faery Trickster who is charming, sly, amoral, and rather dangerous to encounter. In some parts of country, the picking of campion is discouraged, for this invites the faeries' attention -- but here in the West Country, it's a lucky flower. Campion in the house represents the faeries' blessing, provided it's been picked with care and respect. Red campion is not edible, and its herbal use is limited -- but the roots have been used to make a soap substitute, and the flowers for charms and spells to ward against loneliness.

In Norse myth, wild columbine (below) is the flower of Freya, goddess of love, sensuality, and women's independence; in Celtic lore, too, it's a flower associated with women and their Mysteries. Columbine's primary use in hedgerow medicine was as an abortificant: its seeds were ground and mixed wine and other herbs to produce this effect; and then used with wine and a different set of herbs to restore the woman's strength. Also known as Granny's bonnet, lady's shoes, sow wort, and lion's herb, the flower is linked with both the dove and the eagle, with peace and war, and the balancing of opposites: strength in fragility and fragility in strength. Columbine was used for spells invoking courage, wisdom, and clarity in making choices.

Herb Robert (below) is a modest little flower, but it's become one of my favorite sights in the hedgerows...and in our garden too, where it kept appearing in spaces that I'd intended for other things. At first, I confess, I pulled it out as a troublesome weed, until its gentle persistence caused me to look a little closer at this tiny wildflower. I learned that the plant was once much prized by herbalists (and magicians!) in medieval times; and that herbalist today hail its ability to boost the immune system (precisely the thing I most needed). In folklore, according to Margaret Barker, herb Robert is known as "the plant of equality, all its parts being equal and harmonious." It's also another faery plant: its appearance in the garden betokes the blessing of the particular spirits who "quicken" all green living things. The great mystic and herbalist Hildegard of Bingen extolled the virtues of this humble flower, recommending its use (in a powdered form, eaten on bread) to strengthen the blood, balance the mind, and ease all heartbreak.

Valerian (below) is another that has moved itself from the hillside to our garden, rooting firmly in a sunny front slope. "Valerian's botanical name (Valerianna officinalis) comes from the Latin word valere, 'to be strong,' " writes Margaret Baker. "It is said to be a witch-deterrent, to provoke love, and to be a telling aphrodisiac. In the West of England a girl who wore a sprig would never lack lovers." Well. You can't beat that.

In her lovely book Herbal Rituals, Judith Berger envisions the springtime as the Goddess in her maiden aspect:

"In Hebrew the word for life, chai, is also the root of the word meaning wild she-animal, (chaiya), and this is how I see the spring: as a wild, untamed maiden bounding over the dark earth, her footfall touching all life with more life. Hair flying behind her, she leaves in her wake a trail of color, scent, and nourishment, her mood of wicked delight spreading across the ground like green fire. Roused by her passion, the green nations leap toward the sun, brimming with sheer joy, until everywhere we turn our heads we find life unfolding, changing shape, and blossoming, each form in nature dripping with beauty and transformed by the nurture of sun, rain, earth, and air."

Above, the Lady of Bumblehill (a statue made by my friend Wendy Froud) stands in our back courtyard with flowers at her feet. The flowers change a little every year, as Welsh poppies, foxgloves, columbine and other plants self-seed and move about the land. I love these untameable flowers...and so does Tilly. Here she is at just ten weeks old, mesmorized by a hawkweed's bloom. Entranced by its colour. Scenting its magic. And listening closely to its stories.

The passages quoted above are from Herbals Rituals by Judith Berger (St. Martin's Press, 1998) and Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008). All rights reserved by the authors.

More folklore of the wild flowers

Following on from Friday's wildflower post...

As the woods and fields, green hills and hedgerows continue to burst with color and bloom, here's a little more of the wildflower lore that's rooted in the land below our feet. I love knowing and passing on such things. "Re-storying" the land is, I believe, an important part of re-wilding the land, re-wilding our culture, and re-wilding ourselves.

In the springtime, writes herbalist Judith Berger,

"the earth herself seems overtaken with desire to create for the sake of beauty and joy, unveiling at an astounding rate those creations which were conceived and protected in winter's ground-dark womb. Young, delectable leaves shoot up out of the soil, becoming clorophyll-rich as they soak up the food of the sun's fire. Food and medicine plants carpet the ground abundantly, delighting the eyes and tastebuds with a palette of green hues and an array of distinctive earthy flavors. Daily, as light seeps into the unfurling leaves, the plants grow greener and greener with the blood of the sun. As we ingest these plants, we increase our inner fires and pulse with the blood of life, thus inspired to move through our days with the same abandon as the maiden goddess of spring."

Stitchwort (below), appears in Devon in two distinctive colors: white and pink. Greater stitchwort, with its white star-like blooms, also goes by the name star flower, thunder flower (because picking it will cause a storm), Mother Shimbles, snick needles, and snapjacks (due to the popping sound made by its seed pods as they ripen). Lesser stitchwort, with its small pink flowers, is known as piskie, or piskie flower, here in Devon -- though in fact both kinds of stitchwort are under the special protection of the piskies (our local faery folk). They zealously guard the flowers against hedgewitches, who use them for making medicines and charms of protection against piskie mischief -- including a salve that heals the "side stitches" caused when mortals are hit by elf-shot.

Stickwort often grows among stands of nettles -- which is certainly one way to protect it from being picked. Nettles themselves are a wonderful plant (despite their sting), prized by witches, cunning men, herbalists, and wild food foragers. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are faery dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against faery enchantment, black magic, and other forms of sorcery. Historically, nettles have had a wide variety of uses, from making medicines to making cloth. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin," notes folklorist Margaret Baker; "the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness." Today, many of us still harvest the tender top leaves of nettles in the spring. Rich in iron and vitamins, they are an excellent tonic for the immune system when cooked in soups and stews, or brewed for tea.

(For a lengthier discussion of the folklore and use of nettles, go here.)

Germander speedwell ( above), also known as birds-eye or angels-eye, is a flower associated with vision, with magical oinments allowing mortals to see faeries, and with healing afflictions of the eyes -- whether medical or caused by witchcraft. Although largely unmentioned by modern herbalists, it was once considered a valuable plant in hedge-lore here in the West Country. A tea made from its leaves and flower petals is said to be good for coughs (when brewed at strength), or settling the nerves (when brewed more delicately), while also fostering clarity of vision, focus, and purpose.

According to Welsh folklore, wild Welsh poppies (above) don't flourish outside Wales itself, but in fact they can be found throughout the West Country, and in parts of Ireland too. Although the Welsh poppy (Meconopsis cambrica) is somewhat different than the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), it too is associated with sleep, dreams, the spirit world, and various forms of divination. Yellow poppies must never be brought into the house -- they will cause headaches, storms, or lightning strikes -- but wild poppy seeds placed under a pillow will show a young man or maid their future lover's face, or give the dreamer the answer to any question posed while falling asleep. The seeds can also be carried in one's pocket, or strewn in a circle around one's home, to provide protection from faery enchantments, especially those that cause confusion or memory loss.

The cuckoo flower (above) is said to herald the first cuckoo of spring. It grows in damp, grassy meadows and bogs, its petals tinted pink or lavendar, and is also known by the names lady's-smock, milkmaid, May flower, and fairy flower. Associated with the revels of May, hedgewitches used various parts of the plant for love potions and fertility spells -- as well as for the opposite: charms intended to keep love and fertility at bay. Cuckoo flower teas and tonics restored appetites diminished by poor health, while also aiding digestion, treating survy, and easing bowel complaints. The leaves, when young, are edible, tasting peppery, like cress.

In the folk tradition of the West Country, buttercups (above) are a benificent plant -- associated with the sun, yellow butter and the dairy, and ease in domestic labor. On May Day, farmers rubbed the udders of their cows with buttercup flowers to increase the yield and richness of their milk; this also protected them from theft by faeries -- who were always eager to improve their herds of fairy cattle by interbreeding with cows from mortal fields. Buttercups are toxic to ingest so medicinal use of the plant is limited, although some old herbals suggest that a poulstice made of the crushed flowers and leaves is helpful in relieving colds, coughs, and bronchial complaints. "Buttercup water," made by infusing the flower petals in water heated by the sun, was used to bathe sore eyes, and "sweeten" the complexion. Buttercups are part of Rananculus family, related to spearwort, crowfoot and lesser celandine. It was once believed that swallows fed their young on a diet of these flowers, giving them prophetic abilities and clear sight.

Red campion (above and below) -- also known as ragged-robin or robin flower -- is associated with Robin Goodfellow (or Puck), a faery Trickster who is charming, sly, amoral, and rather dangerous to encounter. In some parts of country, the picking of campion is discouraged, for this invites the faeries' attention -- but here in the West Country, it's a lucky flower. Campion in the house represents the faeries' blessing, provided it's been picked with care and respect. Red campion is not edible, and its herbal use is limited -- but the roots have been used to make a soap substitute, and the flowers for charms and spells to ward against loneliness.

In Norse myth, wild columbine (below) is the flower of Freya, goddess of love, sensuality, and women's independence; in Celtic lore, too, it's a flower associated with women and their Mysteries. Columbine's primary use in hedgerow medicine was as an abortificant: its seeds were ground and mixed wine and other herbs to produce this effect; and then used with wine and a different set of herbs to restore the woman's strength. Also known as Granny's bonnet, lady's shoes, sow wort, and lion's herb, the flower is linked with both the dove and the eagle, with peace and war, and the balancing of opposites: strength in fragility and fragility in strength. Columbine was used for spells invoking courage, wisdom, and clarity in making choices.

Herb Robert (below) is a modest little flower, but it's become one of my favorite sights in the hedgerows...and in our garden too, where it kept appearing in spaces that I'd intended for other things. At first, I confess, I pulled it out as a troublesome weed, until its gentle persistence caused me to look a little closer at this tiny wildflower. I learned that the plant was once much prized by herbalists (and magicians!) in medieval times; and that herbalist today hail its ability to boost the immune system (precisely the thing I most needed). In folklore, according to Margaret Barker, herb Robert is known as "the plant of equality, all its parts being equal and harmonious." It's also another faery plant: its appearance in the garden betokes the blessing of the particular spirits who "quicken" all green living things. The great mystic and herbalist Hildegard of Bingen extolled the virtues of this humble flower, recommending its use (in a powdered form, eaten on bread) to strengthen the blood, balance the mind, and ease all heartbreak.

Valerian (below) is another that has moved itself from the hillside to our garden, rooting firmly in a sunny front slope. "Valerian's botanical name (Valerianna officinalis) comes from the Latin word valere, 'to be strong,' " writes Margaret Baker. "It is said to be a witch-deterrent, to provoke love, and to be a telling aphrodisiac. In the West of England a girl who wore a sprig would never lack lovers." Well. You can't beat that.

In her lovely book Herbal Rituals, Judith Berger envisions the springtime as the Goddess in her maiden aspect:

"In Hebrew the word for life, chai, is also the root of the word meaning wild she-animal, (chaiya), and this is how I see the spring: as a wild, untamed maiden bounding over the dark earth, her footfall touching all life with more life. Hair flying behind her, she leaves in her wake a trail of color, scent, and nourishment, her mood of wicked delight spreading across the ground like green fire. Roused by her passion, the green nations leap toward the sun, brimming with sheer joy, until everywhere we turn our heads we find life unfolding, changing shape, and blossoming, each form in nature dripping with beauty and transformed by the nurture of sun, rain, earth, and air."

Above, the Lady of Bumblehill (a statue made by my friend Wendy Froud) stands in our back courtyard with flowers at her feet. The flowers change a little every year, as Welsh poppies, foxgloves, columbine and other plants self-seed and move about the land. I love these untameable flowers...and so does Tilly. Here she is at just ten weeks old, mesmorized by a hawkweed's bloom. Entranced by its colour. Scenting its magic. And listening closely to its stories.

The passages quoted above are from Herbals Rituals by Judith Berger (St. Martin's Press, 1998) and Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008). All rights reserved by the authors.

April 28, 2020

Wildflower Week

As the weather warms and wildflowers emerge, I've been asked to re-publish some of my previous posts containing flower and herb folklore, and I'm happy to oblige. I hope you'll enjoy revisiting these pieces. (New posts will resume on Monday.)

This will also give me some extra time to catch up on my Patreon page and other projects -- all which came to a sudden stop in the weeks follow my brother's death, even though he wouldn't have wanted that. I keep thinking of these words by Ana��s Nin: "And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom."

Grief is hard, and the global pandemic makes it harder still. But it's time to begin unfurling.

Wildflower season

I love the spring months here in Devon, when wildflowers turn the woods and fields and hedgerows into Faerieland, scenting the air with their perfume and the echo of ancient stories. The stress of lockdown and the unfolding pandemic becomes a little easier to bear when the land around us is washed with colour and the hills are breathing magic.

Bluebells are especially loved by faeries, and as such they are dangerous. A child alone in a bluebell wood might be whisked Under the Hill and never seen again, while adults can find themselves lost for days, or years, until the faery spell is broken.Other names the plant is known by: Faery Thimbles, Wood Hyacinths, Harebells (in Scotland, for they grow in fields frequented by hares), and Dead Man's Bells (because the faeries are not kind to those who trample willfully upon them).

Bluebells in the house can be lucky or unlucky, depending on where in British Isles you live. Here in Devon, it's the former: a bouquet of bluebells, picked with gratitude and tended with care, confers the faeries' blessings on the household and "sweetens" spirits sagging after a long winter. Love potions are made of bluebell blossoms, and a bluebell wreath compels the wearer to tell the truth about his or her affections. Despite this association with love, bluebells in Romantic poetry are symbols of loneliness and regret; while in the Victorian's Language of Flowers they represent kindness, humility, and a sense of wonder.

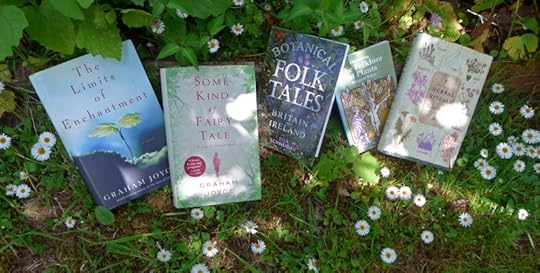

In Some Kind of Fairy Tale, Graham Joyce captured the uncanny magic of a bluebell wood:

"The bluebells made such a pool that the earth had become like water, and all the trees and the bushes seem to have grown out of the water. And the sky above seemed to have fallen down to the earth floor; and I didn't know if the sky was the earth or the earth was water. I had been turned upside down. I had to hold the rock with my fingernails to stop me falling into the sky of the earth or the water of the sky."

Graham's faery novel for adult readers is both magical and sinister, and highly recommended; as is The Limits of Enchantment, a fine novel rich in the folklore of plants and hares.

Wild violets are often associated with the Greek myth of Persephone, for she was out in the fields gathering the flowers when Hades abducted her into the Underworld; they are flowers of change, transition, transformation, and the cycle of death-and-rebirth. In the Middle Ages, the violet represented love that was new, uncertain, changeable or transitory; yet by Victorian times, in the Language of Flowers the violet was a symbol of constancy.

Here in Devon, old country folk are wary of bringing violets (and snowdrops) into the house, for this will curse the farmwife's hens and make them unable to lay. Dreaming of violets is lucky, however, as is wearing the flowers pinned to your clothes...but only if the violets are worn outdoors. Take them off at your doorstep and leave them for the faeries, alongside a bowl of fresh milk.

Primroses guard against dark witchcraft if you gather their blossoms properly: always thirteen or more in a bunch, and never a single flower. On May Day, small primrose bouquets were hung over farmhouse windows and doors to keep black magic and misfortune out, while allowing white magic to enter freely. Primroses were braided into horses' manes and plaited into balls hung from the necks of cows and sheep as protection from piskie mischief on May Day and Beltane.

Hedgewitches made primrose oinment and infusions for "women's troubles" (menstrual cramps) and "melancholy" (depression), while oil of primrose, rubbed on the eyelids, strengthened the ability to see faeries. Primrose wine was a courting gift, proclaiming the giver's constancy -- though by Victorian times, in the Language of Flowers, primroses symbolized the opposite, so a gift of them demonstrated how little you trusted a fickle lover's fine words.

Blue sicklewort (also known as bugle, bugleweed, middle comfrey, and horse & hound) is related to the mint family, and has longed been used as a medicinal herb. The foliage contains a digitalis-like substance, which causes a mild narcotic effect when ingested. In folklore, too, it's a medicine plant, associated with the healing of the body and of hearts broken by sorrow. Once, during a time of great sadness, I felt myself compelled to keep visiting this patch of blue sicklewort in the woods behind my studio. I'd sit on the ground with my coffee thermos and notebooks, finding a strange kind of comfort there. It was only later that I discovered the plant's traditional use as a healer of heartbreak.

The wild orchid is another flower associated with faeries, particularly those who delight in seducing mortals in the woods. It is a plant associated with faery revels, amours, and sensuality. The dried root was a faery aphrodisiac.

The old folk of Devon still know pink stichwort as "piskie" or "the piskie flower." Anyone who dares to pick them (as I do) is in danger of being piskie-led.

Foxglove, with its long pink and white spires, has long been associated with the faeries. Some scholars believe that ''fox'' is a corruption of ''folk,'' and that the name thus means ''the gloves of the Good Folk'' (the faeries). Foxglove used to be known as goblin's gloves in the mountains of Wales, where the flowers were worn by hobgoblins. In Scandinavian lore, foxglove is associated with both foxes and faeries, for the faeries taught foxes to ring the bell-like flowers in warning when hunters approached.

In her lovely book Botanical Folk Tales of Britain and Ireland, my friend Lisa Schneidau writes:

"I was lucky. I was a little girl growing up in 1970s Buckinghamshire with a mother and grandmother who loved wild plants, and six fields of ridge-and-furrow, green-winged orchid meadow behind our house. I remember when the moon daisies were nearly as tall as me, when we picked field mushrooms from the fairy rings and fried them for breakfast, when I could run through the middle of ancient hawthorne hedgerows and travel by secret ways down to the magic old willow tree over the pond. I remember the carpets of cowslips, the endless butterflies, the quivering quaking grass, and the blackberries in autumn....I inherited an insatiable curiosity for plants of all kinds and, with a vivid imagination as always, I wanted to know the stories: why? what? how does it feel to be a green living plant, a meadowsweet compared to a bee orchid?"

"Flowers lure us into the present moment by the miracle of their beauty," writes another friend, Judith Berger (in Herbal Rituals, a beautiful book about medicine plants through the four seasons). "Watching and waiting for a particular plant to bloom gives birth to patience within us. We slow our rhythm down in order to fully experience the process of flowering; expectancy and excitement deepen hand in hand with our patience. As we observe, we come to see that the full unfolding of the flower petals is the culmination of an unhurried dance in which the flower senses and responds, moment by moment, to the environmental conditions which surround and penetrate it. These conditions include termperature, moisture, light, and shadow, as well as the more subtle influences of sound vibrations, heartful care, and respect.

"In Buddhist poetry, there is a verse which reads: 'I entrust myself to the earth, the earth entrusts herself to me.' To entrust is to place something in another's hands with the confidence that what has been given will be cared for."

And so in the changeable days following winter -- now warm, now cold, now wet, now dry -- I entrust myself to the flowers of our hill: bluebell, primrose, blue sicklewort, white and pink stitchwort, red campion. They all emerge whatever the weather, bursts of color and joy in the rain-soaked hills. They do not wait for a "perfect" day to bloom...and neither must I await the "perfect" time to write, or paint, or to pick up the reins of daily life again after illness and grief knocked me flat earlier this year. Recovering one's health is not like stepping through a gateway into bright sun; there is no clear line between "sick" and "well," only the deep, invisible processes of healing, slowly unfolding day by day. To wait for strength, ease and "perfect" pain-free hours is to wait for life to begin instead of living.

And so in the changeable days following winter -- now warm, now cold, now wet, now dry -- I entrust myself to the flowers of our hill: bluebell, primrose, blue sicklewort, white and pink stitchwort, red campion. They all emerge whatever the weather, bursts of color and joy in the rain-soaked hills. They do not wait for a "perfect" day to bloom...and neither must I await the "perfect" time to write, or paint, or to pick up the reins of daily life again after illness and grief knocked me flat earlier this year. Recovering one's health is not like stepping through a gateway into bright sun; there is no clear line between "sick" and "well," only the deep, invisible processes of healing, slowly unfolding day by day. To wait for strength, ease and "perfect" pain-free hours is to wait for life to begin instead of living.

This is life. This is spring. Bright and beautiful yesterday. Cold, wet, and grey now. Tomorrow, something else again. But full of wildflowers.

Words: The passages quoted above are from Some Kind of Fairy Tale by Graham Joyce (Doubleday, 2012), Botanical Folktales of Britain & Ireland by Lisa Scheidau (The History Press, 2018), and Herbals Rituals by Judith Berger (St. Martin's Press, 1998). The quotes in the picture captions are from a variety of sources, including Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker (Shire Classics, 2008), A Contemplation on Flowers: Garden Plants in Myth & Literature by Bobby J. Ward (Timber Press, 2009) and Hedgerow Medicine by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal (Merlin Unwin Books, 2008). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The paintings, by Brian Froud, are from Faeries by Brian Froud & Alan Lee (Abrams, 1978). All rights reserved by the artist.

April 27, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

For many of us of a certain age, Britain's great folk music revival in the middle of the 20th century couldn't have come at a better time. For me, growing up in the Sixties and Seventies, the "electric folk" music of the era was the gateway drug that lead to a deeper exploration of folk music in general, and thence to the adjacent fields of folklore, folk dance, folk drama, and the like. I stumbled upon my first folk album (Steeleye Span's Hark! The Village Wait) in the sale bin of a record store in a depressed Pennyslvania steel town at the age of 13. What it was doing in that improbable place I'll never know -- but the cover intrigued me, I took it home and was hooked by the very first song. In those isolated, pre-Internet days, it was difficult to seek other music like it, or even to know if there was other music like it...but over the next few years I managed to find my way to Pentangle, Fairport Convention, The Albion Country Band, The Watersons, June Tabor, and the rest. I learned what a Child Ballad was. I discovered Cecil Sharp and the English Folk Dance and Song Society; and, through Sharp, the American folk tradition. Thus a chance album discovery grew into a life-long love of folk music in all of its permutations.

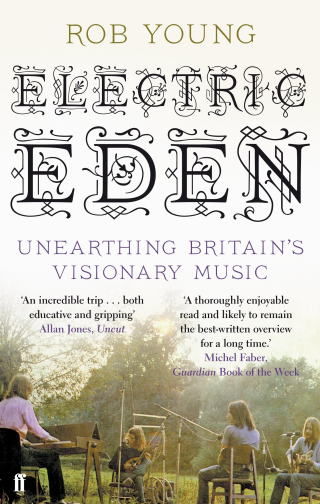

If you, too, remember, the Sixties/Seventies folk revival fondly, I recommend Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain's Visionary Music by Bob Young (Faber & Faber 2011). The book documents the history of British folk music through the 20th century, with information ranging from insights of music scholarship and historical context to pure gossip about who was sleeping with/living with/working with/feuding with whom. It's a lengthy volume, and rambles a bit, but I found it engrossing nonetheless...reminding me of a bands and musicians I'd long forgotten, and introducing me to some new ones too.

If you, too, remember, the Sixties/Seventies folk revival fondly, I recommend Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain's Visionary Music by Bob Young (Faber & Faber 2011). The book documents the history of British folk music through the 20th century, with information ranging from insights of music scholarship and historical context to pure gossip about who was sleeping with/living with/working with/feuding with whom. It's a lengthy volume, and rambles a bit, but I found it engrossing nonetheless...reminding me of a bands and musicians I'd long forgotten, and introducing me to some new ones too.

Okay now, on to this morning's music....

Above: "A Calling On Song" by Steeleye Span (Ashley Hutching, Tim Hart, Maddy Prior, Terry Woods, and Gay Woods), from their first album, Hark! The Village Wait (1970). As the album notes explain: "Songs similar to this one are used by the leaders of rapper and long sword dance teams to preface the dancing and to drum up a crowd. The duration of these songs depended on how long it took for a satisfactory audience to assemble. It was customary to introduce each member of the team as the son of a famous person such as Bonaparte, Nelson, Wellington, etc. This, however is our own 'calling-on', the tune and the basis for the words coming from the captain's song of the Earsdon Sword Dance Team."

Below: "The Lark in the Morning," also from Hark! The Village Wake, performed live in 1971. (Martin Carthy and Peter Knight had replaced the Woods as band members shortly after the album was released.) This version of the song was collected in Sussex by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1904.

Above: A live performance of "Hunting Song" by Pentangle (Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Jacqui McShee, Danny Thompson, and Terry Cox), filmed for a BBC television production in 1970. The song, adapted from 13th century Arthurian narratives, appeared on Pentangle's second album, A Basket of Light (1969).

Below: A live performance of "Willy O Winsbury" by Pentangle, filmed for a Granada television production in 1972. The song is Child Ballad #100, and appeared on Pentangle's fifth album, Solomon's Seal (1972).

Above: "The Famous Flower of Serving Men" (Child Ballad #106 ) sung by Martin Carthy, from his solo album Shearwater (1972). Delia Sherman's first novel, Through a Brazen Mirror, was inspired by the ghostly song, and I highly recommend it.

Below: "Geordie" (Child Ballad #209) sung by June Tabor as part of the duo Silly Sisters, with Maddy Prior. The song appeared on their self-titled debut album (1976).

Above: "Blood and Gold/Mohacs," from Silly Sisters' second album, No More to the Dance. recorded over a decade later in 1988.

Go here for the final song today: "Four Loom Weaver," sung by Maddy Prior and June Tabor -- reunited for a performance at Cecil Sharp House in London in 2008. (I'm not able to embed the video here.) The song, collected in Lancashire by Ewan MacColl, appeared on their first Silly Sisters album in 1976.

Art: two Child Ballad illustrations by Arthur Rackham.

April 24, 2020

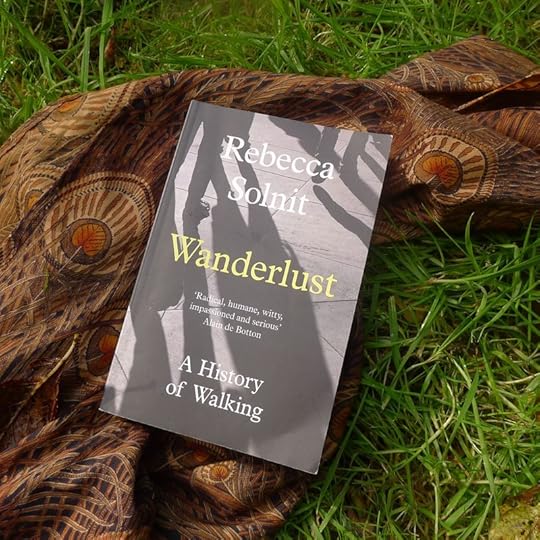

Living at a walker's pace

It's our fifth week of lock-down in the UK, and the circumference of our daily lives has shrunk to places we can reach on foot, "walking for exercise" being one of the few acceptable reasons to leave the house. I live in the country and work from home, so this isn't an enormous change for me -- but for many, accustomed to fast-paced lives mediated by cars or public transit, re-discovering the physical, mental, and creative benefits of experiencing the world solely on foot has been one of the rare gifts of this hard and worrisome time.

In her beautiful book Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit looks at the history of walking through the lens of philosophy, sociology, environmental science, politics, literature and other arts. Reflecting on her own practice of walking in the hills near San Francisco, she writes:

In her beautiful book Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit looks at the history of walking through the lens of philosophy, sociology, environmental science, politics, literature and other arts. Reflecting on her own practice of walking in the hills near San Francisco, she writes:

"These linked paths and roads form a circuit of about six miles that I began hiking ten years ago to ward off my angst during a difficult year. I kept coming back to this route for respite from my work and for my work too, because thinking is generally thought of as doing nothing in a production-oriented culture, and doing nothing is hard to do. It is best done as disguising it as something, and the something closest to nothing is walking. Walking itself is the intentional act closest to the unwilled rhythms of the body, to breathing and the beating of the heart. It strikes a delicate balance between working and idling, being and doing. It is a bodily labor that produces nothing but thoughts, experiences, arrivals."

"The rhythm of walking," she notes, "generates a kind of rhythm of thinking, and the passage through a landscape echoes or simulates the passage through a series of thoughts. This creates an odd consonance between internal and external passage, one that suggests that the mind is also a landscape of sorts and that walking is one way to traverse it. A new thought often seems like a feature of the landscape that was there all along, as thought thinking were traveling rather than making. And so one aspect of the history of walking is the history of thinking made concrete -- for the motions of the mind cannot be traced, but those of the feet can.

"Walking can also be imagined as a visual activity, every walk a tour leisurely enough both to see and think over the sights, to assimilate the new into the known. Perhaps this is where walking's peculiar utility for thinkers comes from. The surprises, liberations, and clarifications of travel can sometimes be garnered by going around the block as well as going around the world, and walking travels both near and far.

"Or perhaps walking should be called movement, not travel, for one can walk in circles or travel around the world immobilized in a seat, and a certain kind of wanderlust can only be assuaged by the acts of the body itself in motion, not the motion of the car, boat, or plane. It is the movement as well as the sights going by that seems to make things happen in the mind, and this is what makes walking ambiguous and endlessly fertile: it is both means and end, travel and destination."

For all her love of the natural world, Solnit, a long-time city dweller, recognizes that a city traversed on foot can be just as creatively inspiring as a woodland path or wilderness trail, at least for those open to its rhythms; for those who are paying attention.

"There is a subtle state most urban walkers know," she writes, "a sort of basking in solitude -- a dark solitude punctuated with encounters as the night sky is punctuated with stars -- one is altogether outside society, so solitude has a sensible geographical explanation, and there is a kind of communion with the nonhuman. In the city, one is alone because the world is made up of strangers, and to be a stranger surrounded by strangers, to walk along silently bearing one's secrets and imagining those of the people one passes, is among the starkest of luxuries. This uncharted identity with its illimitable possibilities is one of the distinctive qualities of urban living, a liberatory state for those who come to emancipate themselves from family and community expectation, to experiment with subculture and identity. It is an observer's state, cool, withdrawn, with senses sharpened, a good state for anybody who needs to reflect or create. In small doses, melancholy, alienation, and introspection are among life's most refined pleasures.

"Speaking as a Londoner, Virginia Woolf described anonymity as a fine and desirable thing, in her 1930 essay 'Street Haunting.' Daughter of the great alpinist Leslie Stephen, she had once declared to a friend, 'How could I think mountains and climbing romantic? Wasn't I brought up with alpenstocks in my nursery and a raised map of the Alps, showing every peak my father had climbed? Of course, London and the marshes are the places I like best.' Woolf wrote of the confining oppression of one's own identity, of the way the objects in one's home 'enforce the memories of our experience.' And so she set out to buy a pencil in a city where safety and propriety were no longer considerations for a no-longer-young woman on a winter evening, and in recounting -- or inventing -- her journey, wrote one of the great essays on urban walking."

Whatever landscape we inhabit (urban, suburban, rural, or other), walking and re-walking the land or neighborhood each day confirms our place in it, deepening our connection to the more-than-human world and expanding our concept of home.

"Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors," Solnit observes, "disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it."

When I look at the way that Tilly takes in the world, "inside" and "outside" are alike to her, with only the annoyance of human doors between them. Nattadon Hill is home to Tilly . . . and I mean all of the hill, from top to bottom: its Commons, its woods, its tumbling streams, the brown bracken slopes, the green farmers' fields, and our warm little house on the woodland's edge. It's all home to her, both the land that is "ours" and the larger landscape that is not.

And perhaps I'm not so different from Tilly. I have walked this hill day after day, season after season, year after year, and it has become my home ground too. The concept of "home" is complex for me (being the woman that I am, with the history that I have), but the weather that sweeps across the hill has pared that concept down to essentials:

Home is a house that I share with my loved ones. It's a landscape walked with a good black dog. It's a hill that knows my particular footsteps, and a wood where the trees all know my name. It's as simple and as solid as the earth below . . . but also fragile, ephemeral, therefore all the more precious. Like life itself.

The passages quoted above are from Wanderlust by Rebecca Solnit (Penguin, 2001); all rights reserved by the author. The drawing is by New Zealand illustrator E.M. Taylor (1906-1964).

April 23, 2020

Happy World Book Day!

Tilly would like to share a few of her favourites:

1. Dog by Susan McHugh, from the wonderful Animal Series published by Reaktion Books. (We're slowly, slowly collecting them all.)

2. God's Dog by Hope Ryden. (We won't tell Tilly that the title refers to North American coyotes, not to Springadors like her.)

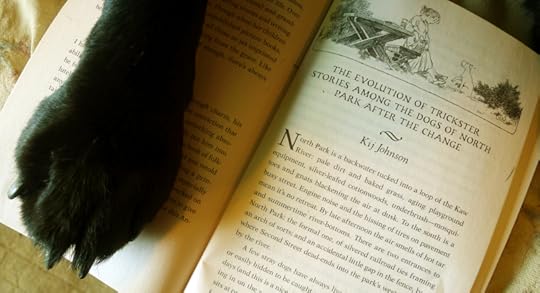

3. The Evolution of Trickster Stories Among the Dogs of North Park After the Change," an absolutely brilliant story by Kij Johnson. The book is The Coyote Road, an anthology of new fiction inspired by traditional Trickster stories, edited by me and Ellen Datlow.

4. Dogsbody by Diana Wynne Jones, a delightful book which was meant to be here too (if only I could find my copy).

What other dog-related books should be on Tilly's reading list?

"Reading is sometimes thought of as a form of escapism, and it���s a common turn of phrase to speak of getting lost in a book. But a book can also be where one finds oneself; and when a reader is grasped and held by a book, reading does not feel like an escape from life so much as it feels like an urgent, crucial dimension of life itself."

- Rebecca Mead (My Life in Middlemarch)

And here's one that Tilly doesn't recommend. (But I do. Shhh! Don't tell her.)

April 22, 2020

Giving voice to the voiceless

For those of us who care about what's going on in the world politically, medically, and ecologically, it can be a struggle to understand how this relates to making art, particularly if we work in mythic, nonrealist forms far removed from the global pandemic and other worrisome headlines of the day.

In her lovely little book Writing the Sacred Into the Real, American poet and essayist Alison Hawthorne Deming discusses the tension between art and activism in her work; and although she's speaking in terms of poetry here, her insights can be applied to the writing of fantasy as well...at least to the kind of poetic, deeply mythic fantasy that rarely appears on the bestsellers list, by writers like Alan Garner, Robert Holdstock, Patricia McKillip, Elizabeth Knox, and so many others (including some of you reading this now).

Writing poetry, says Deming, "is an act of dissent in at least three ways: economically, because the poet labors to make a thing that will never be worth money; temporally, because the poem is an argument with the erosive passage of time; and politically, because in an age that values aggregate data, poetry -- all true art -- insists on the passionate importance of the individual.

"The turning inwards to explore the world through the lens of subject does not necessarily mean a turning away from the world. Denise Levertov turned Wordsworth's lament inside out by writing 'the world is / not with us enough.' Her poetics insisted upon both the lyric impulse -- the song of the soul singing in the present moment -- and the political impulse -- the cry for social justice and peace."

Though Levertov's poetic spirit infuses Deming's, trying to honor these two opposing impulses, she says, "can cause a chronic psychic whiplash. Just when attention is focused on the inner excitement of consciousness, the world calls you a solipsist and demands your attention. Try to tell the world what you think of it, and consciousness will insist that it -- consciousness itself -- is the only thing you can know in its passing, so you had better take heed, right now. But Levertov found balance in the meditative mode, which asks for both introspection and realism -- or as Muriel Rukeyser suggested, the meeting of consciousness and the world -- and she wove a tenuous unity out of contradictions. I take that lesson to heart.

"For me," she explains, "the natural world in all its evolutionary splendor is a revelation of the divine -- the inviolable matrix of cause and effect that reveals itself to us in what we cannot control or manipulate no matter how pervasive our meddling. This is the reason that our technological mastery of nature will always remain flawed. The matrix is more complex than our intelligence. We may control a part, but the whole body of nature must incorporate the change, and we are not capable of anticipating how it will do so.

"We will always be humble before nature, even as we destroy it. And to diminish nature beyond its capacity to restore itself, as our culture seems perversely bent to do, is to desecrate the sacred force of Earth to which we owe a gentler hand. That the diminishment has been caused by abuses of human power makes this issue political. Why should one species have the right to deprive so many others of their biological heritage and future? To write about nature, to record the magnificence, cruelty, and mysteriousness of it, is then an act both spiritual and political.

"Italo Calvino describes how literature's interior explorations can be put to political use:

'Literature is necessary to politics above all when it gives voice to whatever is without a voice, when it gives a name to what as yet has no name, especially to what the politics of language excludes or attempts to exclude. I mean aspects, situations, and languages both of the outer and of the inner world, the tendencies repressed both in individuals and in society. Literature is like an ear that can hear things beyond the understanding of the language of politics; it is like an eye that can see beyond the color spectrum perceived by politics. Simply because of the solitary individualism of his work, the writer may happen to explore areas that no one has explored before, within himself or outside, and to make discoveries that sooner or later turn out to be vital areas of collective awareness.'

"My early interests as a poet," Deming continues, "were to understand the modernist and postmodernist traditions, and to locate myself within their trajectory. And these conditions set aesthetic concerns in opposition to social ones -- the artist as rebel, dissident, and iconoclast. But the wellspring for that inconoclastic energy was for me the belief that art can be a voice of moral and spiritual empathy, an antidote to the cold-hearted self-interest that drives so much of American culture. I have a hunger / for harmony that I feel with dissent.

"Realizing the importance of nature as a subject was a slow process of conversion for me. Way stations along the route: hearing Richard Nelson speak about writing his beautiful meditative book The Island Within after decades of working as a cultural anthropologist and his explaining that he had decided to write about what he loved; hearing Stanley Kunitz say to Fellows at the Work Center that originality in art could come only from what was unique in one's character and experience, not from manipulating the surface of one's technique; remembering that all my life I have hungered for wild places and all of my life wild places have fed me and that this is central to who I am and would have to inform my aesthetic decisions; sitting up in bed as a child, darkness surrounding me, and staring at the mystery of how I came to exist in the world in this body, and how it is an impossible fact that I will one day stop being here; assessing what I most love about being here and what I would like to understand and contribute before leaving."

"I write to make peace with the things I cannot control, " says fellow writer and activist Terry Tempest Williams. "I write to create red in a world that often appears black and white. I write to discover. I write to uncover. I write to meet my ghosts. I write to begin a dialogue. I write to imagine things differently and in imagining things differently perhaps the world will change. I write to honor beauty. I write to correspond with my friends. I write as a daily act of improvisation. I write because it creates my composure. I write against power and for democracy. I write myself out of my nightmares and into my dreams. I write in a solitude born out of community. I write to the questions that shatter my sleep. I write to the answers that keep me complacent. I write to remember. I write to forget....I write as ritual. I write because I am not employable. I write out of my inconsistencies. I write because then I do not have to speak. I write with the colors of memory. I write as a witness to what I have seen. I write as a witness to what I imagine....

I write because it is dangerous, a bloody risk, like love, to form the words, to say the words, to touch the source, to be touched, to reveal how vulnerable we are, how transient we are. I write as though I am whispering in the ear of the one I love."

Can we write fantasy and mythic fiction in this manner as well? Fantasy as ritual, fantasy as witness, fantasy that gives "voice to the voiceless" -- including the whispering more-than-human voices of the land we live on? I believe we can. Or at least I intend to try, and to see where it might take me....

Words: The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming above is from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (The Credo Series, Milkweed Editions, 2010); the passage by Terry Tempest Williams is from Red: Passion and Patience in the Desert (Pantheon, 2001); and the poem by Denise Levetov in the picture captions is from O Taste and See (New Directions, 1964); all rights reserved by the authors. I highly recommend all three of these books.

Pictures: Spring wildflowers on our hill. The drawing is by English illustrator Honore Appleton (1879-1951).

April 21, 2020

Light and shadow

Springtime in Devon is beautiful: the greening of the hills, the budding of the oaks, the bluebells emerging in the woods, the wild ponies giving birth to their leggy foals. Yesterday a neighbour stopped by our gate to ask, "How are you coping with it all?"

"Locked-down in paradise?" I answered. "How could I possibly complain?"

But of course it's not really paradise, and we're not immune from the world's travails. The UK's death rate rises and rises, with no clear government strategy in sight. Friends working for the NHS and other essential services are looking increasingly haggard and discouraged. Much of Howard's theatre work has been cancelled. The bills keep coming while income keeps disappearing. Community life in the village has halted. Family life has closed down too: we see our daughter and other loved ones only on phone and computer screens, with no idea when we'll next be together. My youngest brother's ashes are sitting in a box; no one can gather for a memorial now. We're surrounded by beauty, and it sustains me, but the shadow side of life is equally vivid, equally present.

Most days I focus on all that's good: the gentle rhythms of the countryside, the daily miracle of spring unfolding, the quiet hours in my studio coaxing a  novel into shape, and the small domestic pleasures that I share with Howard and Tilly. But there are days when the shadows press too close, and refuse to be ignored or reasoned with. All I can do then is breathe deeply, accept their presence, and carry on.

novel into shape, and the small domestic pleasures that I share with Howard and Tilly. But there are days when the shadows press too close, and refuse to be ignored or reasoned with. All I can do then is breathe deeply, accept their presence, and carry on.

What I didn't say to my neighbour is that I am coping, even on the hard days, because this is all strangely familiar -- and I suspect that those of you who have also experienced personal (rather than global) medical crisis know what I mean. This is not the first springtime in our lives when beauty and fear have co-existed; when simply being alive each day is a wonder to be grateful for; and when love for family, friends, and community assumes its rightful place at the center of our existence, holding the shadows at bay.

How do we balance light and shadow when crisis puts us on the narrow path between them? How do we avoid despair's passivity, or optimism's blindness to the challenges ahead? The ecological writer Joanna Macy suggests that despair and hope are not oppositional, but two sides of the same coin:

"By honoring our despair, and not trying to suppress it or pave over it as some personal pathology, we open a gateway into our full vitality and to our connection with all of life. Beneath what I call our 'pain for the world,' which includes sorrow and outrage and dread, is the instinct for the preservation of life. When we are unafraid of the suffering of our world, and brave enough to sustain the gaze and speak out, there is a redemptive sanity at work.

"The other side of that pain for our world is a love for our world. That love is bigger than you would ever guess from what our consumer society conditions us to want. It's a love so raw, so ancient, so deep that if you get in touch with it, you can just ride it; you can just be there and it doesn't matter. Then nothing can stop you. But to get to that, you have to stop being afraid of hurting. The price of reaching that is tears and outrage, because the tears and the power to keep on going, they come from the same source."

The transformation of despair into hope is alchemical work, creative work. And what all transformations have in common, writes Rebecca Solnit, is that they begin in the imagination:

"To hope is to gamble. It's to bet on the future, on your desires, on the possibility that an open heart and uncertainty are better than gloom and safety. To hope is dangerous, and yet it is the opposite of fear, for to live is to risk. I say all this to you because hope is not like a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. I say this because hope is an ax you break down doors with in an emergency; because hope should shove you out the door, because it will take everything you have to steer the future away from endless war, from annihilation of the earth's treasures and the grinding down of the poor and marginal. Hope just means another world might be possible, not promised, not guaranteed. Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope."

As I rise and follow Tilly back home, she dances ahead of me on the trail, a four-footed embodiment of exuberance, joy, and living fully in the present. I have known despair, we have all known despair, but on this misty morning I am choosing hope. I am choosing movement, action, transformation. Art is the "ax" I choose to carry: sharp and not too heavy, fit to the limited strength I have. Stories are the light I choose to guide me. They won't banish the shadows completely; nothing and no one can do that. But they keep the light and dark in balance, and help me find meaning in it all .

"It is Story that heals us, that shapeshifts us, that saves us," writes author and artist Sylvia Linsteadt.

Tilly waits on the path ahead. I take a deep breath. And carry on.

The Joanna Macy quote above is from "Women Reimagining the World" (in Moonrise, edited by Nina Simons, 2010); the Rebecca Solnit quote is from her book Hope in the Dark (2004); all rights reserved by the authors. The drawing above is by Scottish illustrator Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916).

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers