Terri Windling's Blog, page 36

May 19, 2020

Following the birds

Still thinking about birds, I love the following description from Through the Woods, the story of a year in an English woodland by H.E. Bates (1905-1975). He's writing here about the busy, beautiful, bird-filled months of the passage from winter to summer:

"And now, with the cherry in full blossom, the primroses at their fullest floppy lushness and the dark smoke of bluebells obscuring and finally putting out the fritillary lamps of the anemones, there is no longer any doubt about the wood or the spring. They have become synonymous, full of tree blossom and ground blossom and the ceaseless passion and passage of birds. The wood is alive as it will never be again. It is still a month from the edge of summer, trees are still more branch than leaf and all day long the birds have no interval of silence at all. And if the fullest frenzy of song, with nightingales and blackbirds mad in the drowsy hay-noons of June, has not been reached, there is a clarity and a shouting of bird life everywhere that is like a silver mocking of winter. The wood is full of it.

"The trees, just full enough in leaf to form a light sound canopy, seem to take the sound of singing and fluting and pinking and scissoring and throw it down the aisles and ridings until it is magnified through a new crescendo into a new beauty. One thrush fills a whole wood with a clash and jingle of silver. One pigeon moans and moans it into an almost summer slumber. A solitary cuckoo beats it with a bold and endless double note into an echoing monotony. The wood now is never silent. There is a constant mad rushing of blackbirds, low and fierce in flight, from place to place among the hazels, a sudden spring laughing of woodpeckers in the treetops. Noons are as noisy as mornings, evenings even fuller of clamour than afternoons. That summer break for silence, the hot bird-stifled uncanniness of June and July, is still a long way off. There is an everlasting restlessness everywhere. "

But it's not, Bates writes, until a few weeks later (when the bluebells, campions and orchis are in full bloom) that the wood looks its best, and sounds its best:

"Cuckoo and blackbird and nightingale, by the middle of May, are calling together, the blackbird all day long and in spite of everything, the cuckoo and the nightingale passionate in the warm spells, shy and almost silent at the slightest turn to cold and wet. The cuckoo mocks everything in the too bright early mornings and is himself mocked to silence before noon by wind and cloud. He goes with the weather like a cock on a church. He is all clatter of arrogance in the sunshine, charming us to death, monotonously cuckooing us into wishing him silent. The suddenly he shuts up, vanishes. All through the spell of cold and wet we hear him from some mysterious distance, as though he had found, somewhere, an inch of summer for himself.

"The nightingale is also fickle, but on a different plane. He seems amazingly temperamental. Far up in the thickening oaks, nothing but a slim bud himself, he is hard to see; also, like the cuckoo, he often vanishes completely, effaced by wind and wet into silence. But when he sings at last, there is no mistaking it. There is a notion that, since he is so named, he sings only by night. It is quite mistaken. He sings all day and, at the height of passion, all night.

"It is a strange performance, the nightingale's. It has some kind of electric, suspended quality that has a far deeper beauty than the most passionate of its sweetness. It is a performance made up, very often, more of silence than of utterance. The very silences have a kind of passion about them, a sense of breathlessness and restraint, of restraint about to be magically broken.

"It can be curiously seductive and maddening, the song beginning very often by a sudden low chucking, a kind of plucking of strings, a sort of tuning up, then flaring out in a moment into a crescendo of fire and honey and then, abruptly, cut off again in the very middle of the phrase. And then comes that long, suspended wait for the phrase to be taken up again, the breathless hushed interval that is so beautiful. And often, when it is taken up again, it is not that same phrase at all, but something utterly different, a high sweet whistling prolonged and prolonged for the sheer joy of it, or another trill, or the chuck-chucking beginning all over again."

For me, the challenge in writing fantasy fiction springing from the myths and folklore of the land is to evoke the numinous world of nature with such precise yet poetical language. Others have done it. Hope Mirrlees, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Patricia McKillip, Diana Wynne Jones, Jane Yolen, Alan Garner, Robert Holdstock, Graham Joyce...to name just a few. Not all fantasy does this, of course. It's a very broad form of literature, containing many different approaches to the "lands beyond the fields we know." But this is the kind of fantasy that thrills me best, and the tradition I want to follow. Whether writing rural stories or urban stories, whether set in this world or wholly imaginary lands, I want to go further and further into the green....

Following the birds.

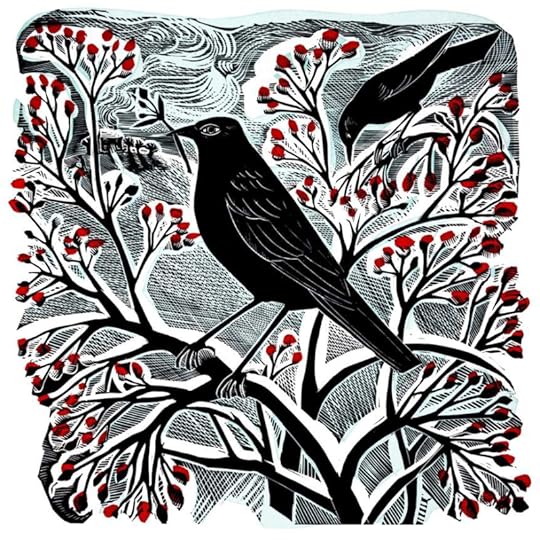

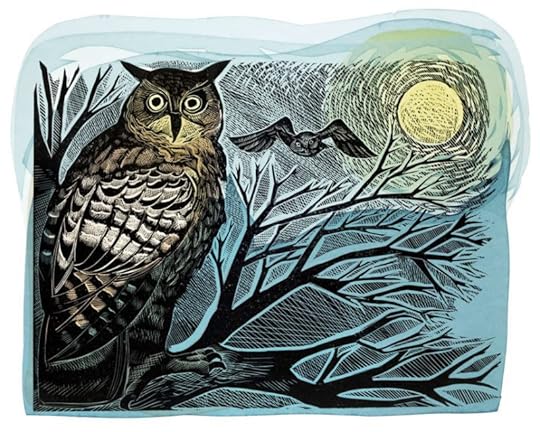

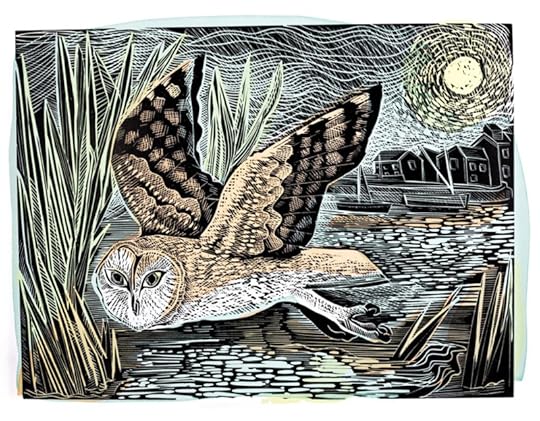

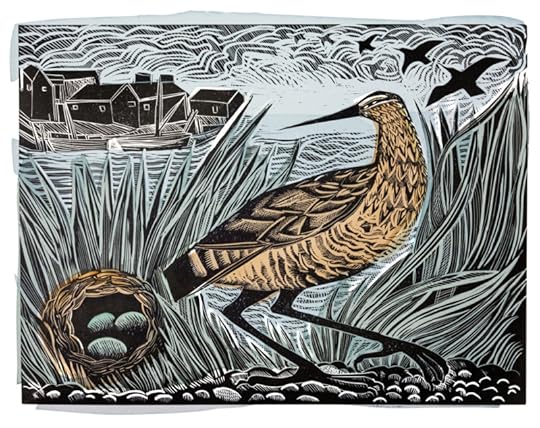

The art today is by printmaker and painter Angela Harding, from Rutland, in the East Midlands of England. "For the past 10 years," she says, "I have worked solely at my art practice in the village of Wing -- which is very apt for a women inspired by birds. My studio is at the bottom of the garden and houses all I need to make my work, including a recently acquired Rochat Albion press. The studio overlooks sheep fields surrounded by gentle sloping hills. It���s not a dramatic landscape but somehow a comforting one and to me feels very much like home. The Rutland countryside does have a wealth of animal and bird life that is a constant inspiration for my work. Rutland Water is just over the ridge which attracts a great diversity of bird life that is world renowned."

To see more of her beautiful work, please visit her website and online shop -- which includes a "Bird Alphabet" series of wood engravings, and her illustrated RSPS Bird Book.

And one last thing: I hope you all know the Singing With Nightingales project by folksinger, folk song collector, and environmental activist Sam Lee and The Nest Collective. If not, please do follow the link and have a listen....

Words: The passage quoted above is from Through the Woods by H.E. Bates (Little Toller Books edition, 2011). Pictures: The images are identified in the picture captions. (Hold your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artist and author's estate.

May 18, 2020

The folklore of birds

Birds have been creatures of the mythic imagination since the very earliest times. Various birds, from eagles to starlings, serve as messengers to the gods in stories the world over, carrying blessings to humankind and prayers up to the heavens. They lead shamans into the Spirit World and dead souls to the Realm Beyond; they follow heroes on quests, uncover secrets, give warning and shrewd council.

The movements, cries and migratory patterns of birds have been studied as oracles. In Celtic lands, ravens were domesticated as divinatory birds, although eagles, geese and the humble wren also had their prophetic  powers. In Norse myth, the two ravens of Odin flew throughout the world each dawn, then perched on the raven-god's shoulder to whisper news into his ears. A dove with the power of human speech sat in the branches of the sacred oak grove at Zeus's oracle at Dodona; a woodpecker was the oracular bird in groves sacred to Mars.

powers. In Norse myth, the two ravens of Odin flew throughout the world each dawn, then perched on the raven-god's shoulder to whisper news into his ears. A dove with the power of human speech sat in the branches of the sacred oak grove at Zeus's oracle at Dodona; a woodpecker was the oracular bird in groves sacred to Mars.

According to various Siberian tribes, the eagle was the very first shaman, sent to humankind by the gods to heal sickness and suffering. Frustrated that human beings could not understand its speech or ways, the bird mated with a human woman, and she soon gave birth to a child from whom all shamans are now descended. In a mystic cloak of bird feathers, the shaman chants, drums and prays him- or herself into a trance. The soul takes flight, soaring into the spirit world beyond our everyday perception. (Great care must be taken in this exercise, lest the wing-borne soul forgets its way back home.)

Likewise, the shamans of Finland call upon their eagle ancestors to lead them into the spirit realms and bring them safely back again. Shamans, like eagles, are blessed (or cursed) with the ability to cross between the human world and the realm of the gods, the lands of the living and the lands of the dead. Despite the healing powers this gives them (the "medicine" of their bird ancestry), men and women in shamanic roles were often seen as frightening figures, half-mad by any ordinary measure, poised between co-existent worlds, fully present in none. The Buriats of Siberia traced their lineage back to an eagle and a swan, honoring the ancestral swan-mother with migration ceremonies each autumn and spring. To harm a swan, or even mishandle swan feathers, could cause illness or death; likewise, to harm a woman could bring the wrath of the swans upon men.

A swan-maiden was the mother of Cuchulain, hero of Ireland's Ulster cycle, and thus the warrior had a geas (taboo) against killing these sacred birds. In "The Children of Lir," one of the Three Great Sorrows of Irish mythology, the four children of the lord of the sea are transformed into wild  swans by the magic of a jealous step-mother. Neither Lir himself nor all the great magicians of the Tuatha De Danann can mitigate the power of the curse, and the four are condemned to spend three hundred years on Lake Derryvaragh, three hundred years on the Mull of Cantyre, and a final three hundred years off the stormy coast of Mayo. During this time, the Children of Lir retain the use of human speech, and the swans are famed throughout the land for the beauty of their song. The curse is ended when a princess of the South is wed to Lairgren, king of Connacht in the North. The swan-shapes fall away at last, but now they resume their human shapes as four withered and ancient souls. They soon die, and are buried together in a single grave by the edge of the sea. For many centuries, Irishmen would not harm a swan because of this sad story -- and country folk still say that a dying swan sings a song of eerie beauty, recalling the music of the Children of Lir...and echoing the ancient Greek belief that a swan sings sweetly once in a lifetime (ie: a "swan song"), in the moments before it dies. (More swan tales can be found here and here.)

swans by the magic of a jealous step-mother. Neither Lir himself nor all the great magicians of the Tuatha De Danann can mitigate the power of the curse, and the four are condemned to spend three hundred years on Lake Derryvaragh, three hundred years on the Mull of Cantyre, and a final three hundred years off the stormy coast of Mayo. During this time, the Children of Lir retain the use of human speech, and the swans are famed throughout the land for the beauty of their song. The curse is ended when a princess of the South is wed to Lairgren, king of Connacht in the North. The swan-shapes fall away at last, but now they resume their human shapes as four withered and ancient souls. They soon die, and are buried together in a single grave by the edge of the sea. For many centuries, Irishmen would not harm a swan because of this sad story -- and country folk still say that a dying swan sings a song of eerie beauty, recalling the music of the Children of Lir...and echoing the ancient Greek belief that a swan sings sweetly once in a lifetime (ie: a "swan song"), in the moments before it dies. (More swan tales can be found here and here.)

The Tuatha De Danaan, the fairy race of old Ireland, were known to appear in the shape of white birds, their necks adorned with gold and silver chains; alternately, they also took human shape, wearing magical  cloaks of feathers. The Celtic islands of immortality had orchards thick with birds and bees, where beautiful fairy women lived in houses thatched with bright bird feathers.

cloaks of feathers. The Celtic islands of immortality had orchards thick with birds and bees, where beautiful fairy women lived in houses thatched with bright bird feathers.

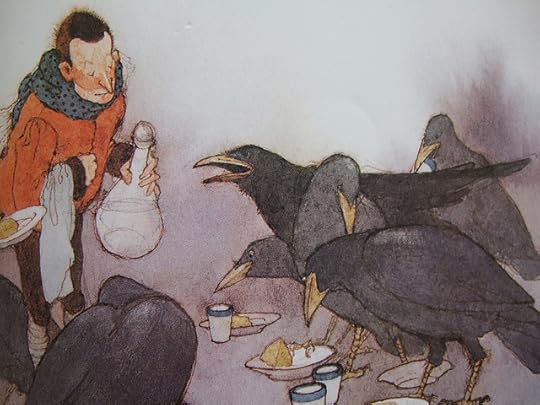

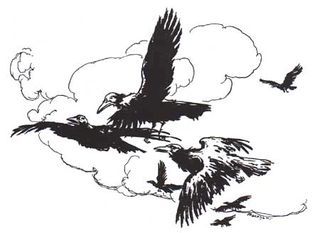

Crows and ravens are also birds omnipresent in myth and folklore. The crow, commonly portrayed as a trickster or thief, was considered an ominous portent -- and yet crows were also sacred to Apollo in Graeco-Roman myth; to Varuna, guardian of the sacred order in Vedic myth; and to Amaterasu Omikami, the sun-goddess of old Japan. The ancestral spirits of the Maratha in India resided in crows; in Egypt a pair of crows symbolized conjugal felicity. In the Aboriginal lore of Australia and the myths of many North American tribes, Raven appears as a dual-natured Trickster and Creator God, credited with bringing fire, light, sexuality, song, dance, and life itself to humankind.

In Celtic lore, the raven belonged to Morrigan, the Irish war goddess -- as well as to Bran the Blessed in the great Welsh epic, The Mabinogion. Tradition has it that Bran's severed head is buried under the Tower of London. A ceremonial Raven Master still keeps watch over the birds of the Tower; an old custom says that if Bran's birds ever leave the Tower, the kingdom will fall.

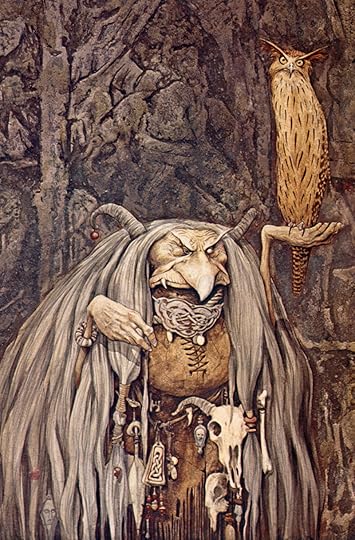

The owl is a bird credited with more malevolence than any other, even though its reputation for wisdom goes back to our earliest myths. In Greece, the owl (sacred to both Athena and Demeter) was revered as a prescient creature -- yet also feared, for its call or sudden appearance could foretell a death. Lilith, Adam's wife before Eve (banished for her lack of submissiveness) was associated with owls and depicted with wings or taloned feet.

In the Middle East, evil spirits took the shape of owls to steal children away -- while in Siberia, tamed owls were kept in the house as protectors of children. In Africa, sorcerers in the shape of owls caused mischief in the night.

To the Ainu of Japan, the owl was an unlucky creature -- except for the Eagle Owl, revered as a mediator between humans and the gods. In North America, the symbolism of the owl varied among indigenous tribes. The Pueblo peoples considered them baleful; the Navajo believed them to be the restless, dangerous ghosts of the dead. The Pawnee and Menominee, on the other hand, related to them as protective spirits, and Tohono O'Odham medicine singers used their feathers in healing ceremonies. When we turn to Celtic traditions we find that the owl, though sacred, is an ill omen, prophesying death, illness or the loss of a woman's honor. In the Fourth Branch of The Mabinogion, the magician Gwydion takes revenge upon Blodeuwedd (the girl he made out of flowers, who married and then betrayed his son) by turning her into an owl and setting her loose into the world. (I highly recommend two novels inspired by this fascinating myth:Owl Service by Alan Garner and The Island of the Mighty by Evangeline Walton.)

To the Ainu of Japan, the owl was an unlucky creature -- except for the Eagle Owl, revered as a mediator between humans and the gods. In North America, the symbolism of the owl varied among indigenous tribes. The Pueblo peoples considered them baleful; the Navajo believed them to be the restless, dangerous ghosts of the dead. The Pawnee and Menominee, on the other hand, related to them as protective spirits, and Tohono O'Odham medicine singers used their feathers in healing ceremonies. When we turn to Celtic traditions we find that the owl, though sacred, is an ill omen, prophesying death, illness or the loss of a woman's honor. In the Fourth Branch of The Mabinogion, the magician Gwydion takes revenge upon Blodeuwedd (the girl he made out of flowers, who married and then betrayed his son) by turning her into an owl and setting her loose into the world. (I highly recommend two novels inspired by this fascinating myth:Owl Service by Alan Garner and The Island of the Mighty by Evangeline Walton.)

The crane is another bird associated with death in the British Isles. It was one of the shapes assumed by the King of Annwn, the Celtic underworld. To the druids, cranes were portents of treachery, war, evil deeds and evil women...yet the bird enjoyed a better reputation in other lands. It was sacred to Apollo -- a messenger and a honored herald of the spring. The pure white cranes in Chinese lore inhabited the Isles of the Blest,  representing immortality, prosperity, and happiness. In Japan, the crane was associated with Jorojin, a god of longevity and luck. In the folktales of Russia, Sicily, India and other cultures the crane was the "animal guide" who led the hero on his adventures; and tales about cranes who marry human men can be found throughout the far East.

representing immortality, prosperity, and happiness. In Japan, the crane was associated with Jorojin, a god of longevity and luck. In the folktales of Russia, Sicily, India and other cultures the crane was the "animal guide" who led the hero on his adventures; and tales about cranes who marry human men can be found throughout the far East.

In Celtic lore, the magpie was a bird associated with fairy revels; with the spread of Christianity, however, this changed to a connection with witches and devils. In Scandinavia, magpies were said to be sorcerers flying to unholy gatherings, and yet the nesting magpie was once considered a sign of luck in those countries. In old Norse myth, Skadi (the daughter of a giant) was priestess of the magpie clan; the black and white markings of the bird represented sexual union, as well as male and female energies kept in perfect balance. In China the magpie was the Bird of Joy, and two magpies symbolized marital bliss; in Rome, magpies were sacred to Bacchus and a symbol of sensual pleasure. In England, the sighting of magpies is still considered an omen in this common folk rhyme: "One for sorrow, two for joy; three for a girl, and four for a boy. Five for silver, six for gold, and seven for a secret that's never been told."

The wren is another "fairy bird": a portent of fairy encounters, and sometimes a fairy in disguise. The wren was sacred to Celtic druids, and to the Welsh poet-magician Taliesin, thus it was unlucky to kill the wren at any time of year except during the ceremonial "Hunting of the Wren," around the winter solstice. In this curious custom (still practiced in some rural areas of the British Isles and France), "Wren Boys" dress in rag-tag costumes, bang on pots, pans and drums, and walk in procession behind a wren killed and mounted upon a pole decorated with oak leaves and mistletoe. In some areas, Wren Boys also appear on Michaelmas, 12th Night, or St. Stephen's Day carrying a live wren from cottage to cottage (in a small "Wren House" decorated with ribbons), collecting tributes of coins and mugs of beer wherever they stop. The wren is known as the king of the birds, an honorific explained in the following story: All the birds held a parliament and decided that whoever could fly the highest and fastest would be crowned king. The eagle easily outdistanced the others, but the clever wren hid under his wing until the eagle faltered -- then the wren jumped out and flew higher.

The wren is another "fairy bird": a portent of fairy encounters, and sometimes a fairy in disguise. The wren was sacred to Celtic druids, and to the Welsh poet-magician Taliesin, thus it was unlucky to kill the wren at any time of year except during the ceremonial "Hunting of the Wren," around the winter solstice. In this curious custom (still practiced in some rural areas of the British Isles and France), "Wren Boys" dress in rag-tag costumes, bang on pots, pans and drums, and walk in procession behind a wren killed and mounted upon a pole decorated with oak leaves and mistletoe. In some areas, Wren Boys also appear on Michaelmas, 12th Night, or St. Stephen's Day carrying a live wren from cottage to cottage (in a small "Wren House" decorated with ribbons), collecting tributes of coins and mugs of beer wherever they stop. The wren is known as the king of the birds, an honorific explained in the following story: All the birds held a parliament and decided that whoever could fly the highest and fastest would be crowned king. The eagle easily outdistanced the others, but the clever wren hid under his wing until the eagle faltered -- then the wren jumped out and flew higher.

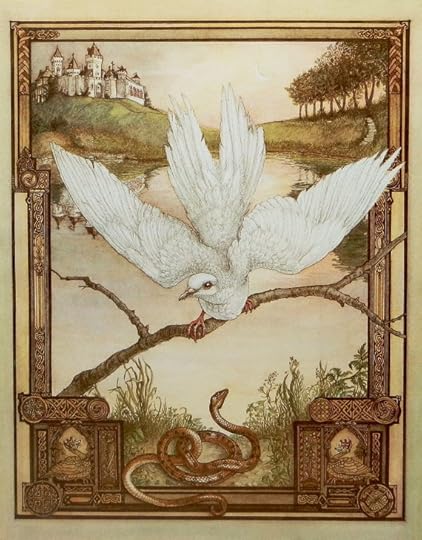

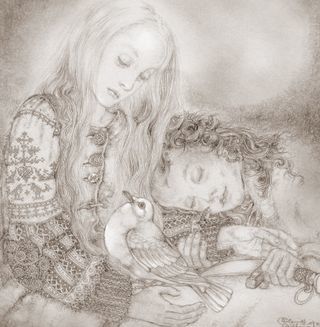

The dove is a bird associated with the Mother Goddesses of many traditions -- symbolizing light, healing powers, and the transition from one state of existence to the next. The dove was sacred to Astarte, Ishtar,  Freyja, Brighid, and Aphrodite. The bird also represented the external soul, separate from the life of the body -- and thus magicians hid their souls or hearts in the shape of doves. Doves give guidance in fairy tales, where (in contrast with their usual gentle image) they show a marked penchant for bloody retribution. White doves light upon the tree Cinderella has planted upon her mother's grave, transforming rags to riches so she can go to the prince's ball. These are the birds who warn the prince of "blood in the shoe!" when the stepsisters try to fit into the delicate slipper by hacking off their heels and toes. The birds eventually blind the treacherous sisters, pecking out their eyes. Murdered children in several fairy tales reappear as snow-white doves, hovering around the family home until vengeance

Freyja, Brighid, and Aphrodite. The bird also represented the external soul, separate from the life of the body -- and thus magicians hid their souls or hearts in the shape of doves. Doves give guidance in fairy tales, where (in contrast with their usual gentle image) they show a marked penchant for bloody retribution. White doves light upon the tree Cinderella has planted upon her mother's grave, transforming rags to riches so she can go to the prince's ball. These are the birds who warn the prince of "blood in the shoe!" when the stepsisters try to fit into the delicate slipper by hacking off their heels and toes. The birds eventually blind the treacherous sisters, pecking out their eyes. Murdered children in several fairy tales reappear as snow-white doves, hovering around the family home until vengeance  is finally served. Likewise, the white dove in the Scots Border ballad "The Famous Flower of Serving Men" is also a human soul in limbo: a knight cruelly murdered by his mother-in-law. He flies through the forest shedding blood-red tears and telling his story. The woman is eventually burned. (See Delia Sherman's Through a Brazen Mirror and Ellen Kushner's Thomas the Rhymer for literary adaptations of this tale.)

is finally served. Likewise, the white dove in the Scots Border ballad "The Famous Flower of Serving Men" is also a human soul in limbo: a knight cruelly murdered by his mother-in-law. He flies through the forest shedding blood-red tears and telling his story. The woman is eventually burned. (See Delia Sherman's Through a Brazen Mirror and Ellen Kushner's Thomas the Rhymer for literary adaptations of this tale.)

The mysterious song of the nightingale has also inspired several classic tales; most famously: "The Nightingale" by Denmark's Hans Christian Andersen and the tragic story of "The Nightingale and the Rose" by England's Oscar Wilde. (I recommend Kara Dalkey's lyrical novel The Nightingale, based on the former.)

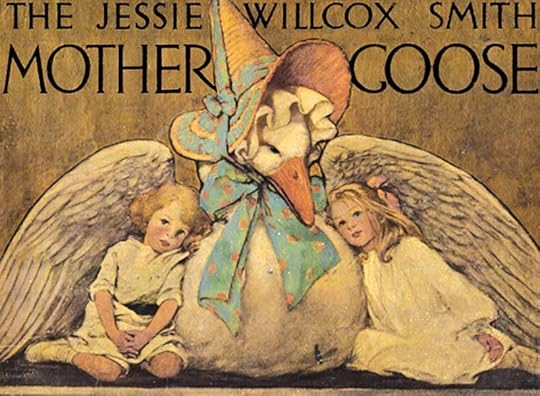

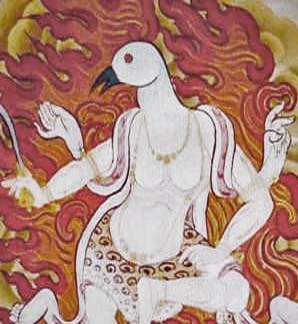

Geese were holy, protected birds in many ancient societies. In Egypt, the great Nile Goose created the world by laying the cosmic egg from which the sun was hatched. The goose was sacred to Isis, Osiris, Horus, Hera, and Aphrodite. In India, the goose -- a solar symbol -- drew the chariot of Vishnu; the wild  goose, a vehicle of Brahma, represented the creative principal, learning and eloquence. In Tibet, gooseheaded women can be found among the dakini, which are volatile female spirits that aid or hinder one's spiritual journey. In Siberia, the goddess Toman shook feathers from her sleeve each spring. They turned into geese, carefully tended and observed by Siberian shamans. Freyja, the goddess of northern Europe who travels the land in a chariot drawn by cats, is sometimes pictured with only one human foot and one foot of a goose or swan -- an image with shamanic significance in various traditions. Berchta, the fierce German goddess (or witch) associated with the Wild Hunt, is also pictured with a single goose foot as she rides upon the backs of storms. Caesar tells us that geese were sacred in Britain, and thus taboo as food -- a custom still existent in certain Gaelic areas today. Goose-girls, talking geese, and the goose who lays golden eggs are all standard ingredients in the folk tales ("Mother Goose" tales) of Europe. The phrase "silly as a goose" is recent; Ovid called them "wiser than the dog."

goose, a vehicle of Brahma, represented the creative principal, learning and eloquence. In Tibet, gooseheaded women can be found among the dakini, which are volatile female spirits that aid or hinder one's spiritual journey. In Siberia, the goddess Toman shook feathers from her sleeve each spring. They turned into geese, carefully tended and observed by Siberian shamans. Freyja, the goddess of northern Europe who travels the land in a chariot drawn by cats, is sometimes pictured with only one human foot and one foot of a goose or swan -- an image with shamanic significance in various traditions. Berchta, the fierce German goddess (or witch) associated with the Wild Hunt, is also pictured with a single goose foot as she rides upon the backs of storms. Caesar tells us that geese were sacred in Britain, and thus taboo as food -- a custom still existent in certain Gaelic areas today. Goose-girls, talking geese, and the goose who lays golden eggs are all standard ingredients in the folk tales ("Mother Goose" tales) of Europe. The phrase "silly as a goose" is recent; Ovid called them "wiser than the dog."

The stork is another Goddess bird -- sacred to Hera and nursing mothers, which may be why it appears in folklore carrying newborn babies to earth. The pelican is symbolic of women's faith, sacrifice, and maternal devotion -- due to the belief that it feeds its young on the blood of its own breast. Kites and gulls are the souls of dead fisherman returned to haunt the shores -- a tradition limited to the men of the sea, not their daughters or wives. "The women don't come back no more," explained one old English fisherman to folklorist Edward Armstrong. "They've seen trouble enough." The lark, the linnet, the robin, the loon...they, too, have engendered tales of their own, winging their way between heaven and earth in sacred stories, folktales, fairy tales, old rhymes and folkways from around the globe.

The following prayer comes from the Highlands of Scotland, recorded (in Gaelic) more than one hundred years ago:

Power of raven be yours,

Power of eagle be yours,

Power of the Fiann.

Power of storm be yours,

Power of moon be yours,

Power of sun.

Power of sea be yours,

Power of land be yours,

Power of heaven.

Goodness of sea be yours,

Goodness of earth be yours,

Goodness of heaven.

Each day be joyous to you,

No day be grievous to you,

Honor and compassion.

Love of each face be yours,

Death on pillow be yours,

And God be with you.

���I pray to the birds," says Terry Tempest Williams (in her gorgeous book Refuge) "because they remind me of what I love rather than what I fear. And at the end of my prayers, they teach me how to listen.���

The art above is identified in the picture captions (run your cursor over the images to see them). All rights reserved by the artists and photographers, who are: Ione Rucquoi, Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), Gregory Colbert, Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997), John Duncan (1866-1945), Milo Winter (1888-1956); Carson Ellis, Lisbeth Zwerger, Audrey Niffenegger, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Brian Froud, Rima Staines, Steven Kenny, Fred Hall, Henry Ryland (1856-1924), Heidi Holder, Sulamith Wulfing (1901-1989), H.J. Ford (1860-1941), Rie Cramer (1887-1997), Danielle Barlow, Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), J��zef Marian Che��mo��ski (1849-1914), Gretchen Jacobsen, Lisbeth Zwerger, and Fidelma Massey.

For more bird lore, I recommend: Secret Language of Birds by Adele Nozedar, The Language of the Birds edited by David M. Guss, The Healing Wisdom of Birds by Lesley Morrison, The Folklore of Birds by Edward A. Armstrong, and Birds in Legend, Fable and Folklore by E. Ingersoll.

May 17, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm out of the office this morning in order to take Tilly to the vet (she has an immune system impairment that requires monthly shots) -- which is a complicated procedure in the middle of Cornonavirus quarantine. Rather than leave you with no music to start the week, I pulled some favourite songs from this blog's archives. Inspired by the rich bird life we're experiencing during this quiet time of the world's "great pause," all the music today is on the theme of birds in the folk tradition....

I'm out of the office this morning in order to take Tilly to the vet (she has an immune system impairment that requires monthly shots) -- which is a complicated procedure in the middle of Cornonavirus quarantine. Rather than leave you with no music to start the week, I pulled some favourite songs from this blog's archives. Inspired by the rich bird life we're experiencing during this quiet time of the world's "great pause," all the music today is on the theme of birds in the folk tradition....

Above: "King of the Birds," written and performed by Karine Polwart, who grew up in a musical family in Sterlingshire, Scotland. This beautiful, folkloric song comes from Powart's fifth album, Traces (2012).

Below: Polwart performs another original song, "Follow the Heron," at the Shrewsbury Folk Festival in 2011. It comes from her second album, Scribbled in Chalk (2006).

Above: "Three Ravens" (audio only) performed by Breton harpist C��cile Corbel, from Finist��re. It's a variant of Child Ballad No. 26 (also known as "Twa Corbies," as performed here by Bert Jansch), and was recorded for the first of Corbel's five albums, Songbook 1 (2006).

Below: "Hela'r Dryw: Hunting of the Wren" (audio only), performed in Welsh by Fernhill, one of the leading bands in the "Welsh Renaissance" of folk music. The song concerns an old folk tradition once common throughout the British Isles, and still practiced in some communities today. The recording is from Fernill's Amser (2014).

The song above isn't exactly a folk song but I'm going to throw it in here anyway: Paul McCartney's "Blackbird" performed in Gaelic by Julie Fowlis, from the Gaelic-speaking island of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Fowlis has released six solo albums, of which Alterum (2017) is the latest.

Below: Kate Rusby, from Barnsley, Yorkshire, performs "Mockingbird" at the Cambridge Folk Festival in 2011. The song, written by Rusby, was first recorded on her ninth album, Make the Light (2010), and was also included on her double album, Twenty (2012).

Above: "Hawk and Crow" (audio only), a traditional ballad sung by Emily Smith, from Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. You'll find it on Smith's eighth solo album, Echoes (2014).

And to end with: "Come Home Pretty Bird," a lovely song co-written by Emily Smith & David Scott, performed in Switzerland in 2012. This one comes from Smith's third album, Too Long Away (2008).

If you'd like a few more bird songs this morning, try: "Blackbird," an old English ballad performed by C��cile Corbel, Show of Hand's version of "Crow on the Cradle" (by Sydney Carter), and three traditional songs for lark lovers: "The Lark in the Morning" sung by Maddy Prior; "The Lark" sung by Kate Rusby (backed up by Nic Jones), and "Waiting for the Lark" sung by the peerless June Tabor. Also, two fairy-tale-like songs: "The Gay Goshawk" (Child Ballad No. 96) performed by the folk-rock band Mr. Fox, and Natalie Merchant's beautiful rendition of "Crazy Man Michael" (by Richard Thompson & Dave Swarbrick), from Fairport Convention's Liege & Leaf.

If you'd like a few more bird songs this morning, try: "Blackbird," an old English ballad performed by C��cile Corbel, Show of Hand's version of "Crow on the Cradle" (by Sydney Carter), and three traditional songs for lark lovers: "The Lark in the Morning" sung by Maddy Prior; "The Lark" sung by Kate Rusby (backed up by Nic Jones), and "Waiting for the Lark" sung by the peerless June Tabor. Also, two fairy-tale-like songs: "The Gay Goshawk" (Child Ballad No. 96) performed by the folk-rock band Mr. Fox, and Natalie Merchant's beautiful rendition of "Crazy Man Michael" (by Richard Thompson & Dave Swarbrick), from Fairport Convention's Liege & Leaf.

Speaking of birds, I highly recommend The Bird's Child by Sandra Leigh Price (Fourth Estate/HarperCollins Australia, 2015), an utterly enchanting novel set in Australia in the 1920s. It's beautifully written, steeped in both bird lore and magic (of the sleight-of-hand variety), evokes a fascinating period of Australian history, and is well worth seeking out. Francis Hardinge's Young Adult fantasy novel Fly by Night (Macmillan, 2018), about a girl and a goose in a magical version of the 18th century, is also well worth seeking out. She is one of the best fantasy writers of her generation: brilliant, quirky, and consistently original.

Speaking of birds, I highly recommend The Bird's Child by Sandra Leigh Price (Fourth Estate/HarperCollins Australia, 2015), an utterly enchanting novel set in Australia in the 1920s. It's beautifully written, steeped in both bird lore and magic (of the sleight-of-hand variety), evokes a fascinating period of Australian history, and is well worth seeking out. Francis Hardinge's Young Adult fantasy novel Fly by Night (Macmillan, 2018), about a girl and a goose in a magical version of the 18th century, is also well worth seeking out. She is one of the best fantasy writers of her generation: brilliant, quirky, and consistently original.

The artwork today, in order of appearance, is "The Seven Ravens" by Teresa Jenellen, an illustrator based in Wales; a drawing by British book artist Honor C. Appleton (1879-1951);"Martha" (from the book of the same name) by the Russian author/illustrator Gennady Spirin; and "The Seven Doves" by British book artist Warwick Goble (1862-1943).

Fantasy in Times of Crisis

For those who missed yesterday's online Fantasy Symposium, here's the recorded version.

I thoroughly enjoyed discussing our field with five colleagues whose works I admire so much (plus our excellent moderator, Gabriel Schenk) -- despite the gremlins in the broadband wires who kept bouncing me off of Zoom. I was forced to flee the studio mid-symposium, run down the hill, and hook up to the broadband in our house...but fortunately, that did the trick!

Howard took the photo below before it all started. Coffee in hand on the studio steps, I was feeling quite relaxed at that moment, little knowing there were gremlins ahead....

Many thanks to all of you who took time out of your day to join us live on Zoom and YouTube. Although I still prefer real gatherings to virtual ones, it's good to keep the conversation going any way we can during these challenging times; and it was wonderful to be connected to so many fantasy readers all around the world. I hope we can do more things like this again.

May 16, 2020

Today!

Today I am taking part in the Symposium on Fantasy Literature sponsored by the good folks who run the annual "Tolkien Lectures" at Pembroke College -- which is Tolkien's old college at Oxford University. The symposium is online, it's free, and all are welcome. More information can be found here.

The Symposium takes place on Zoom (register here) from 4:00 to 5:30 pm British time (11 am ��� 12:30 U.S. Eastern time). It will also be broadcast live on YouTube (and, I believe, available for viewing afterwards).

The other speakers are Kij Johnson, Adam Roberts, Lev Grossman, V.E. Schwab, and Rebecca F. Kuang, and I'm honored to be among them. Our topic for discussion is a timely one: the importance of fantasy literature in times of crisis.

I hope you can join us.

The sponsors are inviting donations for The Society of Author���s COVID-19 Crisis Fund, which responds to the loss of income many writers have faced as a result of the coronavirus. (Please don't worry if you've lost income yourself and can't.) My apologies if this is the first you've heard about this event. I've been passing the word on Facebook and Twitter, and didn't even realize I'd failed to mention here. Mea culpa!

May 15, 2020

Harvesting stories

From Words Are My Matter by Ursula K. Le Guin:

"Gary Snyder gave us the image of experience as compost. Compost is stuff, junk, garbage, anything, that's turned to dirt by sitting around a while. It involves silence, darkness, time, and patience. From compost, whole gardens grow.

"It can be useful to think of writing as gardening. You plant the seeds, but each plant will take its own way and shape. The gardener's in control, yes; but plants are living, willful things. Every story has to find its own way to the light. Your great tool as a gardener is your imagination.

"Young writers often think -- are taught to think -- that a story starts with a message. That is not my experience. What's important when you start is simply this: you have a story you want to tell. A seedling that wants to grow. Something in your inner experience is forcing itself towards the light. Attentively and carefully and patiently, you can encourage that, let it happen. Don't force it; trust it. Watch it, water it, let it grow.

"As you write a story, if you can let it become itself, tell itself fully and truly, you may discover what its really about, what it says, why you wanted to tell it. It may be a surprise to you. You may have thought you planted a dahlia, and look what came up, an eggplant! Fiction is not information transmission; it is not message-sending. The writing of fiction is endlessly surprising to the writer.

"Like a poem, a story says what it has to say it the only way it can be said, and that is the exact words of the story itself. Why is why the words are so important, why it takes so long to learn how to get the words right. Why you need silence, darkness, time, patience, and a real solid knowledge of English vocabulary and grammar.

"Truthful imagining from experience is recognizable, shared by its readers."

I urge you to read Le Guin's lovely essay in full. You'll find it here in Words Are My Matter, from the good folks at Small Beer Press.

Words: The passage above is from "Making Up Stories," published in Words Are My Matter: Writings About Life & Books by Ursula K. Le Guin (Small Beer Press, 2016); all rights reserved by the author's estate. The poem in the picture captions is from Circles on the Water by Marge Piercy (Knopf, 1988), all rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: Corray Farm on Scotland's west coast, near Glenelg, photographed on a trip up to the Hebrides three years ago. (Gracious, has it really been that long?) Pictured here are the farm's polytunnels (with the tiny figures of Charles Vess, Karen Shaffer, Irene Gallo and Greg Manchess), its turf-roofed office, Howard reading in the yurt cafe, and the four-footed welcoming committee. Some day we'll all be able to travel again...and I would very much love to do so in the same company.

May 14, 2020

Recommended reading

"The essayist's job," writes Rebecca Solnit "is to gather up the shards or map them where they are, to find the pattern out there or make one with words about the disconnections and mysteries. This reading of the word is a form of travel, questing and searching and gathering. Essays are restless literature, trying to find out how things fit together, how we can think about two things at once, how the personal and the public can inform each other, how two overtly dissimilar things share a secret kinship, how intuitive and scholarly knowledge can cook down together, how discovery can be a deep pleasure."

I couldn't agree more. We're living in a Golden Age of essays due to the number of online publications that publish them -- particularly personal essays, many of them incredibly moving. It's a shame that the word "essay" connotes something dry and scholarly to many readers. The essays I love are anything but, and prejudice against the form (like the old prejudice against fantasy fiction) causes too many people to miss out on a whole field that is incredibly vital and exciting right now.

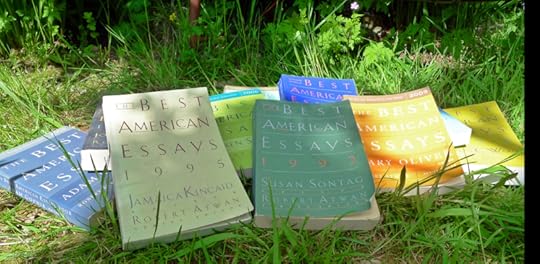

A friend of mine only recently stumbled upon the particular pleasure of essays, and in order to feed his growing addiction he wrote to ask for a list of my favorite collections published in last few years.

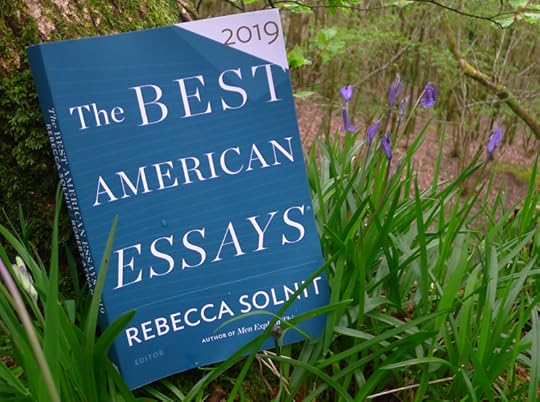

"The best essays?" I answered. "That's easy. Start with Best American Essays, edited by Robert Atwan, along with a different guest editor every year. I read it religiously and always discover new writers there."

"I'll check them out," my friend replied. "But what I really want are your favourite writers. Over the last, oh, two-three years, which collections did you truly love? I'm making a reading list."

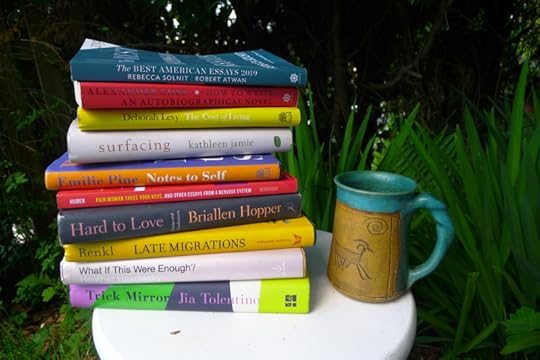

I duly compiled a list for my friend -- and, with his blessing, I'm also sharing it here: an extremely subjective handful of recent favorites. (By "recent," following my friend's guidelines, I stuck to books published from 2017 to the present.) My bias runs to personal essays (of a memoirist nature) and those on the subjects of writing, nature, or living with illness...but there's not a lot that I won't at least try. Restricting my picks to a reasonable number was hard, so I made this my measure: Did I like the book enough to re-read it? (Or, in the case of more recent publications, am I likely to re-read it?) That whittled the list down to eight.

In alphabetical order, so that I don't have to rank them:

1. How to Write an Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee (Martiner Books, 2018)

In this stunning collection, Chee writes about his childhood in coastal Maine, his years as a gay activist in San Francisco, and his long, fraught process of becoming a novelist in New York City. These are wonderful essays, beautifully rendered: honest, funny, searing, inspiring. (Go here for my post on the book.)

2. Out of the Woods: Seeing Nature in the Everyday by Julia Corbett (University of Nevada Press, 2018)

The title says it all really. These are wide-ranging essays on nature in urban and other non-wilderness settings: informative, eloquent, and fascinating. I picked this one up when I saw it had won the 2018 Reading the West Award, thoroughly enjoyed it, and learned a thing or two about the natural world as well.

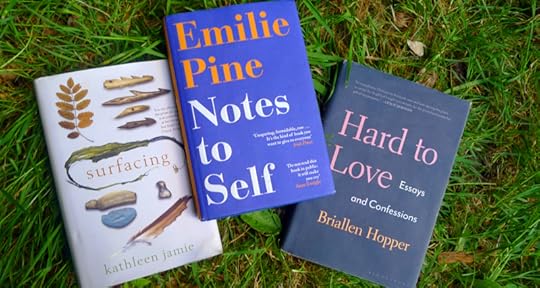

3. Hard to Love by Briallen Hopper (Bloomsbury, 2019)

I adore this book, full of smart, beautifully written, warm-hearted essays about family, community, and relationships in their many forms: relationships with siblings, housemates, friends, lovers, books. Please read my post about it, and then please seek out a copy. I've re-read this one twice already.

4. Pain Woman Takes Your Keys & Other Essays from a Nervous System by Sonya Huber (The University of Nebraska Press, 2017)

Here's another collection I still can't get off my mind -- a beautifully rendered inquiry into living with illness and disability. I know that sounds grim, but it's not -- and the quality of Huber's writing is not to be missed. (I wrote about it here: Spinning straw into gold, pain into art.)

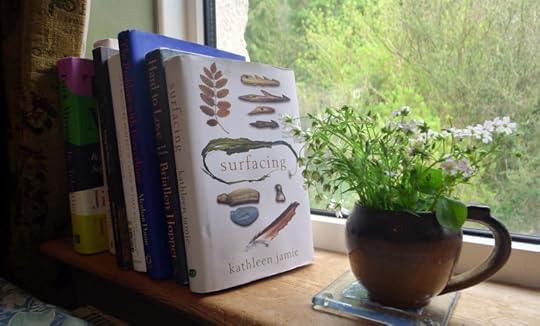

4. Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie (Sort of Books, 2019)

Although I've admired the previous books by this Scottish poet and naturalist, nothing prepared for the power and beauty of Surfacing. With settings ranging from the Orkney islands to Alaska and China, these essays emerge from liminal place where nature and culture meet, written in prose that invites comparison to Nan Shepard and Barry Lopez. (I wrote about Surfacing here.)

5. The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy (Penguin, 2019)

I read an online excerpt from Levy's slim, powerful collection, and immediately had to track down a copy -- which I then devoured in one long sitting. It was worth the lost sleep! Although written in the form of essays, each essay builds on the ones before it to create an incisive memoir, covering the end of Levy's marriage, the death of her mother, and her life as a working writer in London. Her wit is sharp her, her language precise, and the book is unforgettable.

6. Notes to Self by Emilie Pine (Penguin, 2019)

This debut collection from a young Irish writer is incredibly assured and beautifully penned. Pine writes personal essays grounded in her own life, but wrests universal insights from her material -- whether she's discussing her eccentric parents, the female body, or life as an Irish academic. I loved this gem of a book.

7. The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations by Toni Morrison (Pisces Books, 2019)

It's a bit of a grab-bag of material, this one -- but since I'd happily read Morrison's grocery list, this is well worth seeking out. The best of the work gathered here is smart, fierce, provocative, and inspiring, and even the minor pieces are good.

8. Erosions: Essays of Undoing by Terry Tempest Williams (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2019)

Williams is another writer whose work I can't get enough of, and her latest collection is no exception. Based in the Utah desert, she argues passionately for the land and its people, in prose that is achingly personal as well as political. Her work is endlessly inspiring to me. (But if you are new to it, don't start with this one; start with Refuge and work your way up.)

And here are a few other good reads:

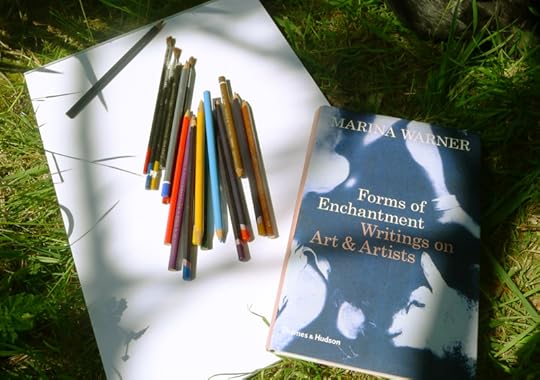

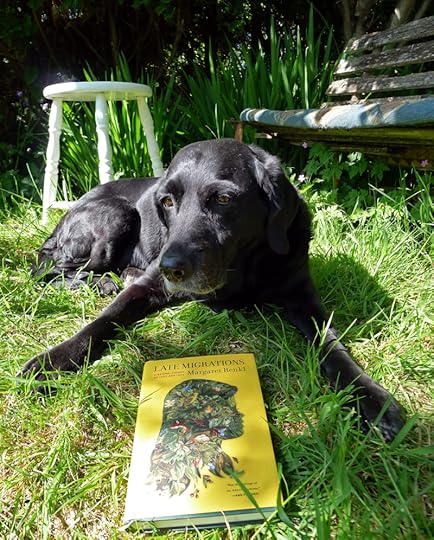

Jia Tolentino's Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion (HarperCollins, 2019) and Heather Havrilesky's What if This Were Enough? (Doubleday, 2018) are debut collections from two young American journalist, mixing personal essays with cultural pieces that are smart and insightful. Late Migrations: A History of Love & Loss by Margaret Renkl (Milkweed Editions, 2019) is a lyrical volume of short, bittersweet pieces on nature and family in the American south. Forms of Enchantment: Writing on Art & Artists by British mythographer and scholar Marina Warner (Thames & Hudson, 2018) contains erudite essays on fine artists whose work has a magical bent -- and not necessarily artists you would expect, mixing the likes of Paula Rego and Kiki Smith with Louise Bourgeois, Tacita Dean, and Jumana Emil Abboud. For feminist essays that really make you think, I loved The Mother of All Questions and Call Them by Their True Names by American cultural philosopher Rebecca Solnit (Granta, 2017 and 2018), and Bitch Doctrine: Essays for Dissenting Adults (Bloomsbury, 2018) by the fearless young British writer Laurie Penny.

I am genuinely addicted to the Best American Essays series -- including the excellent backlist of older volumes. The 2009 edition, for example, was guest edited by Mary Oliver, and the most recent by Rebecca Solnit.

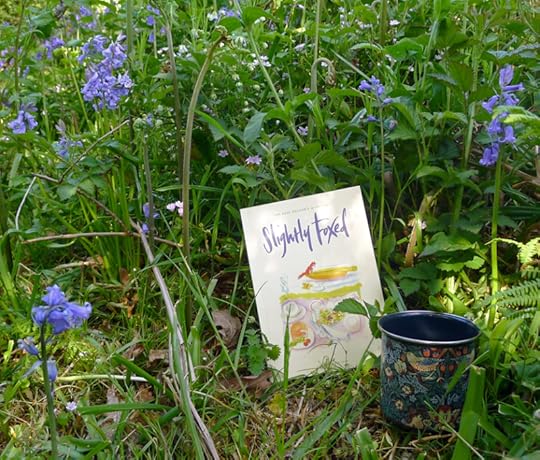

I also highly recommend Slightly Foxed, a quarterly magazine full of charming, informative essays about books and authors of an older vintage: favorite books, forgotten books, notorious books, and much more. The magazine is published here in England, but well worth the extra postage price if you subscribe from other parts of the world. It's delightful.

Are you an essay lover yourself? If so, what else would recommend (published between 2017 and the present)? Many of the authors I've listed above are female, white, and writing in English, so recommendations of recent essay collections by male and nonwhite authors would be especially welcome.

The quote by Rebecca Solnit is from The Best American Essays, 2019, edited by Solnit and Robert Atwan (Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin, 2019). All rights reserved by the author.

May 13, 2020

The myths we make, the stories we tell

In her early memoir Plant Dreaming Deep, May Sarton (1912-1995) recounted the experience of buying and renovating a late-18th century house in a tiny village in rural New Hampshire, where she crafted a life dedicated to poetry, nature, and solitude. At a time when selfless commitment to marriage and family was still the standard measure of a woman's virtue, Plant Dreaming Deep celebrated the pleasures of independence, self-reliance, and living alone.

Its author, mind you, was not a hermit. Sarton's days were amply stocked with friendship, romance, travel, adventure, and the international web of connection arising from a long literary career. She spent time with lovers and friends in Boston, she taught, she travelled around the country giving readings...but she did her best work in solitude, and work was her priority.

A woman living alone and unmarried by choice, privileging her writing over other social bonds, was rare enough when Plant Dreaming Deep was published in 1968 that the book caused something of a stir. "Sarton chose the way of solitude with all its costs," wrote feminist scholar Carolyn Heilbrun (in an essay published in 1982), "and heartened others with the news that this adventure, this terrible daring, might be endured."

This was a message that many in Sarton's generation hungered for and Plant Dreaming Deep was a popular success, appealing particularly to women who had given up their own work after marriage and children, and who had little solitude themselves. They romanticized the life she led, imagining a tranquil idyll of poetry and music and flowers from the garden -- not the hard labor and professional ups and downs of life as a working writer.

Sarton herself came to feel that she'd painted too rosy a picture of her sojourn in the country -- and so her next memoir, The Journal of Solitude, aimed to set the record straight. In this volume she recorded her doubts, her creative struggles, her professional frustrations, her poignant loneliness. The woman who emerges from this text is prickly, moody, and exasperating compared to the narrator of Plant Dreaming Deep, but also thoroughly human. Sarton's rigorous honesty throughout the book is astonishing, brave, and unsettling.

I recently dipped into these two volumes again, re-reading Sarton's reflections on solitude in light of the global pandemic that has isolated so many. Like Sarton, I have a taste for solitude, so days of semi-isolation are easier on me than on those of a more extroverted stamp -- but solitude chosen freely is a different beast than solitude imposed by crisis. My temperament is generally steady, and yet I, too, have been strangely moody of late. My heart soars as spring unfolds around me, plunges with the horror of the daily news, rises in my peaceful studio, and falls again as the world crowds in. Each day I ground myself in work, finding strength and purpose in language and paint; each night that ground crumbles underfoot as worry and fear move through my dreams.

In Plant Dreaming Deep and Journal of Solitude, Sarton acknowledges both aspects of self-isolation: the deep pleasure and concomitant pain of retreating from the wider world. It's the mixture of the two that makes this time, for me, feel so surreal.

In Plant Dreaming Deep, Sarton reflects on the difference between an "isolated" and "quiet" life, in words that echo my initial experience of the current lock-down:

"In that first week [in the farmhouse] I felt I was running all the time. There were hundreds of things I had in mind to do, things about the house, things about the garden, besides the spate of poems that had been pushing their way out. But I imagined that, as time went on, this state of affairs would calm down and I myself would calm down, to lead the meditative life, the life of a Chinese philospher, that my friends quite naturally imagine I must lead here, way all alone in a tiny village, with few interruptions and almost no responsibilities.

"But in all the eight years I have lived here, it has not yet become a quiet life. It is a life lived at a high pitch. One of the facts about solitude is that one becomes as alert as an animal to every change of mood in the skies, and to every sound. The thud of the first apple falling never fails to startle the wits out of me; there has been no sound like it for a year....The intense silence magnifies the slightest creak or whisper.

"But more than any such purely physical reasons for staying on the qui vive, there are inner reasons for being highly tuned up when one lives alone. The alertness is also there toward the inner world, which is always close to the surface for me when I am here, so it may be a mouse in the wainscot that keeps me awake, but it may just as well be a half-formed idea. The climate of poetry is also the climate of anxiety. And if I inhabit the house, it also inhabits me, and sometimes I feel as if I myself were becoming an intersection for almost too many currents of too intense a nature."

In Journal of Solitude, she speaks of the darker side of seclusion: the fears that arise, and the courage required to overcome them and keep on making art:

"I have said elsewhere that we have to make myths of our lives, the point being that if we do, then every grief or inexplicable seizure by weather, woe, or work can -- if we discipline ourselves and think hard enough -- be turned into account, be made to yield further insight into what it is to be alive, to be a human being, what the hazards are of a fairly usual, everyday kind. We go up to Heaven and down to Hell a dozen times a day -- at least I do. And the discipline of work provides an exercise bar, so that the wild, irrational motions of the soul become formal and creative. It literally keeps one from falling on one's face....

"We fear disturbance, change, fear to bring to light and to talk about what is painful. Suffering often feels like failure, but it is actually the door into growth."

By acknowledging both sides of solitude, Sarton helps me understand why my experience of pandemic self-isolation varies so widely from day to day, or even hour to hour. The joy I feel as the world slows down, and the deep anxiety that this produces, are just two sides of the same coin.

Knowing this, I'll continue to value the quiet hours the lock-down gives me -- and make my peace with the fretful, fearful dreams that are part of it too.

Make a myth of your life, says Sarton. Learn what hardship has to teach you, and use in your art.

I am making myths, and telling stories, and trying to do just that.

Words: The quotes above are from May Sarton's Journal of Solitude (W.W. Norton, 1973). The poem in the picture caption is from Sarton's Letters from Maine (W.W. Norton, 1984). All rights reserved by the authors estate. Pictures: The bliss of bluebells.

May 11, 2020

Time and creativity

I'm out of the studio today due to other commitments requiring attention -- including a commitment to myself to take some walking-and-thinking time to focus on a difficult passage in my novel-in-progress. I'll be back here bright and early tomorrow morning, and Myth & Moor will resume!

''Midway through writing a novel, I have regularly experienced moments of bowel-curdling terror, as I contemplate the drivel on the screen before me and see beyond it, in quick succession, the derisive reviews, the friends' embarrassment, the failing career, the dwindling income, the repossessed house, the divorce....

''Working doggedly on through crises like these, however, has always got me there in the end. Leaving the desk for a while can help. Talking the problem through can help me recall what I was trying to achieve before I got stuck. Going for a long walk almost always gets me thinking about my manuscript in a slightly new way.''

- Sarah Waters ("Sarah Waters' Rules for Writers")

''To allow ourselves to spend afternoons watching dancers rehearse, or sit on a stone wall and watch the sunset, or spend the whole weekend rereading Chekhov stories -- to know that we are doing what we���re supposed to be doing -- is the deepest form of permission in our creative lives. The British author and psychologist Adam Phillips has noted, 'When we are inspired, rather like when we are in love, we can feel both unintelligible to ourselves and most truly ourselves.' This is the feeling I think we all yearn for, a kind of hyperreal dream state. We read Emily Dickinson. We watch the dancers. We research a little known piece of history obsessively. We fall in love. We don���t know why, and yet these moments form the source from which all our words will spring.''

- Dani Shapiro (Still Writing: The Perils & Pleasures of a Creative Life)

Words: The Sarah Waters quote is from "Sarah Waters' Rules for Writers" (The Guardian, 23 February, 2010). The Dani Shapiro quote is from Still Writing (Grove Press/Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013), which I recommend. The quotes in the picture captions are from a variety of sources. (Move your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: My work studio, a small cabin by the woods on a Devon hillside.

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Let's start the week with songs of love lost and found in the countryside. I send them out to all of you locked down in urban spaces right now, and longing for a bit of green....

Above: "Down by the Sally Gardens" (from a poem William Butler Yeats, 1889, set to the air The Maids of Mourne Shore), performed by Emily Mae Winters -- a singer/songwriter born in England, raised in Ireland, and now based in London. The song appears on her gorgeous album Siren Serenade (2017).

Below: "The Lark in the Morning" (a traditional song collected in Sussex in 1904), sung by The Imagined Village's Eliza Carthy, with guest vocalist Jackie Oates. The song appears on the band's second album, Empire & Love (2010).

Above: "I Wandered by the Brookside" (a traditional song collected in Oxfordshire, circa 1916), performed by The Askew Sisters (Hazel and Emily Askew). The song appears on their album Enclosure (2019), a beautiful meditation on nature, Britain's Enclosures Acts, and enclosures of all kinds.

Below: An American Appalachian version of "Riddles Wisely Expounded" (Child Ballad #2), performed by folk musician, actor, and theatre director Sophie Crawford, based in London. The song appears on her first album Silver Pin (2019), which is well worth a listen.

Above: "The Gardener" (Child Ballad #219), performed by singer, cellist, fiddler, and viola player Rachel McShane, from north-east England. Best known for her work with Bellowhead, this song appeared on McShane's fine solo album No Man's Fool (2009).

Below: "The Broomfield Hill" (Child Ballad #43), performed by the long-running Scottish folk band Malinky. It's from their terrific album Flower & Iron (2008).

Above: "As I Roved Out," a traditional Irish song performed acapella by American singer-songwriter Becca Stevens and bluegrass mandolin master Chris Thile, filmed for the Live From Here television program (January, 2020).

And to end as we began, with William Butler Yeats...

Below: "Golden Apples of the Sun" ( from a poem by Yeats, 1899), performed by American folksinger Judy Collins. The song appeared on her classic album of the same title (1962).

For more information on Child Ballads, go here. Photos: Tilly in the local deer park, full of bluebells this time of year.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers