Terri Windling's Blog, page 35

May 28, 2020

Wild empathy

In yesterday's post, Scott Russell Sanders discussed the act of empathy with animals, and others unlike ourselves, in relation to shamanic shape-shifting: as a means of "reaching out in imagination to a fellow creatures." Reflecting on this has led me back to Jay Griffith's essay "Forests of the Mind" (2012), on the power of metaphor in shamanism and art. She writes:

"[Shape-shifting] is part of the repertoire of the human mind, cousin to mimesis, empathy and Keats���s 'negative capability,' known to poets and healers since the beginning of time. It did not hold literal truth, quite obviously, but had a 'slanted, metaphoric truth' ....

"Shape-shifting is a transgressive experience, a crossing over: something flickers inside the psyche, a restless flame in a gust of wind, endlessly transformative. The mind moves from its literal pathways to its metaphoric flights. Art is made like this, from a volatile bewitchment, of a self-forgetting and an identification with something beyond.

"Ted Hughes once said that the secret of writing poetry is to 'imagine what you are writing about. See it and live it ... Just look at it, touch it, smell it, listen to it, turn your self into it.' One writing exercise Hughes suggested for students was titled: 'I am the Amazon.' We are what we think, and we humans have a way to become other, in a necessary, wild and radical empathy.

"Shape-shifting involves a willingness to make mimes in the mind, copying something else. Art, meanwhile, depends on mimesis furthering our desire to know and to understand. In a recent, Ovidian, dance piece, 'Swan,' French dancers performed and swam with live swans, imitating the birds in a mime which alluded to the metamorphosis of all art, and to the artists��� ability to lose themselves in order to mirror something beyond.

"'But we, when moved by deep feeling, evaporate; we/breathe ourselves out and away,' wrote Rilke in 'The Second Elegy.'

"In making art, the artist expires, breathing herself out to allow the inspiring to happen, the breathing in of glinting universal air, intelligent with many minds, electric and on the loose. Artist, shape-shifter, shaman or poet, all are lovers of metamorphosis, all are minded to vision, insight and dream."

I recommend reading Griffith's essay in full, as well as her splendid book Wild: An Elemental Journey -- an exploration of "wildness" and "wilderness" in nature, culture, myth, and art.

Words: The quoted passage by Jay Griffiths above is from "Forests of the Mind" (Aeon Magazine, 12 October, 2012). The poem in the picture captions is from Dark Sweet: New & Selected Poems by Linda Hogan (Coffeehouse Press, 2014). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: An afternoon walk and a visit with some of our neighbours in the Devon hills.

May 27, 2020

For World Otter Day: the blessing of otters

One of the mythic borderlands I'm especially drawn to (as evidenced by my writing and art over the decades) is the place where humans and animals meet: as neighbors, as cousins who speak each other's language, as shape-shifters in each other's skins.

"Long ago the trees thought they were people," says Tulalip storyteller Johnny Moses, recounting a traditional tale. "Long ago the mountains thought they were people. Long ago the animals thought they were people. Someday they will say, 'long ago the humans thought they were people.' "

In "Voyageur," a gorgeous essay by Scott Russell Sanders, the writer and his daughter watch otters during a camping trip in the borderlands between Minnesota and Ontario. What was it that kept him riveted to the spot, watching the animals with such intense fascination? What did the otters mean to him, and what did he want from them?

In "Voyageur," a gorgeous essay by Scott Russell Sanders, the writer and his daughter watch otters during a camping trip in the borderlands between Minnesota and Ontario. What was it that kept him riveted to the spot, watching the animals with such intense fascination? What did the otters mean to him, and what did he want from them?

"Not their hides, as the native people of this territory, the Ojibwa, or the old French voyageurs might have wanted; not their souls or meat," he writes. "I did not even want their photograph, although I found them surpassingly beautiful. I wanted their company. I desired their instruction -- as if, by watching them, I might learn to belong somewhere as they so thoroughly belonged here. I yearned to slip out of my skin and into theirs, to feel the world for a spell through their senses, to think otter thoughts, and then to slide back into myself, a bit wiser for the journey.

"In tales of shamans the world over, men and women make just such leaps, into hawks or snakes or bears, and then back into human shape, their vision enlarged, their sympathy deepened. I am a poor sort of shaman. My shape never changes, except, year by year, to wrinkle and sag. I did not become an otter,  even for an instant. But the yearning to leap across the distance, the reaching out in imagination to a fellow creature, seems to me a worthy impulse, perhaps the most encouraging and distinctive one we have. It is the same impulse that moves us to reach out to one another across differences of race or gender, age or class. What I desired from the otters was also what I most wanted from my daughter and from the friends with whom we were canoeing, and it is what I have always desired from neighbors and strangers. I wanted their blessing. I wanted to dwell alongside them with understanding and grace. I wanted them to go about their lives in my presence as though I were kin to them, no matter how much I might differ from them outwardly."

even for an instant. But the yearning to leap across the distance, the reaching out in imagination to a fellow creature, seems to me a worthy impulse, perhaps the most encouraging and distinctive one we have. It is the same impulse that moves us to reach out to one another across differences of race or gender, age or class. What I desired from the otters was also what I most wanted from my daughter and from the friends with whom we were canoeing, and it is what I have always desired from neighbors and strangers. I wanted their blessing. I wanted to dwell alongside them with understanding and grace. I wanted them to go about their lives in my presence as though I were kin to them, no matter how much I might differ from them outwardly."

Later in essay, Sanders writes about two loons who wake him in the middle of the night, "wailing back and forth like two blues singers demented by love," and the bald eagle who watches their progress down the river from its perch on a dead tree's branch. What did the eagle see, he wonders?

"Not food, surely, and not much of a threat, or it would have flown. Did it see us as fellow creatures? Or merely as drifting shapes, no more consequential than clouds? Exchanging

"Not food, surely, and not much of a threat, or it would have flown. Did it see us as fellow creatures? Or merely as drifting shapes, no more consequential than clouds? Exchanging

stares with this great bird, I dimly recalled a passage from Walden that I would look up after my return to the company of books:

"'What distant and different beings in the various mansions of the universe are contemplating the same one at the same moment! Nature and human life are as various as our several constitutions. Who shall say what prospect life offers to another? Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other's eyes for an instant?'

"Neuroscience may one day pull off that miracle, giving us access to other eyes, other minds. For the present, however, we must rely on our native sight, on patient observation, on hunches and empathy. By empathy, I do not mean the projecting of human films onto nature's screens, turning grizzly bears into teddy bears, crickets into choristers, grass into lawns; I mean the shaman's leap, a going out of oneself into the inwardness of other beings.

"The longing I heard in the cries of the loons was not just a feathered version of mine, but neither was it wholly alien. It is risky to speak of courting birds as blues singers, of diving otters as children taking turns on a slide. But it is even riskier to pretend we have nothing in common with the rest of nature, as though we alone, the chosen species, were centers of feeling and thought. We cannot speak of that common ground without casting threads of metaphor outward from what we know and what we do not know.

"The longing I heard in the cries of the loons was not just a feathered version of mine, but neither was it wholly alien. It is risky to speak of courting birds as blues singers, of diving otters as children taking turns on a slide. But it is even riskier to pretend we have nothing in common with the rest of nature, as though we alone, the chosen species, were centers of feeling and thought. We cannot speak of that common ground without casting threads of metaphor outward from what we know and what we do not know.

"An eagle is other, but it is also alive, bright with sensation, attuned to the world, and we respond to that vitality wherever we find it, in bird or beetle, in moose or lowly moss. Edward O. Wilson has given this impulse a lovely name, biophilia, which he defines as the urge 'to explore and affiliate with life.' Of course, like the coupled dragonflies that skimmed past our canoes or like osprey hunting fish, we seek other creatures for survival. Yet even if biophilia is an evolutionary gift, like the kangaroo's leap or the peacock's tail, our fascination with living things carries us beyond the requirements of eating and mating. In that excess, that free curiosity, there may be a healing power. The urge to explore has scattered humans across the whole earth -- to the peril of many species, including our own; perhaps the other dimension of biophilia, the desire to affiliate with life, could lead us to honor the entire fabric and repair what has been torn."

In the conclusion of his essay, Sanders points out that the fellowship of all creatures "is more than a handsome metaphor. The appetite for discovering such connections is also entwined in our DNA. Science articulates in formal terms affinities that humans have sensed for ages in direct encounters with wildness. Even while we slight or slaughter members of our own species, and while we push other species toward extinction, we slowly,  painstakingly acquire knowledge that could enable us and inspire us to change our ways. Only if that knowledge begins to exert a pressure in us, and we come to feel the fellowship of all beings as potently as we feel hunger and fear, will we have any hope of creating a truly just and tolerant society, one that cherishes the land and our wild companions along with our brothers and sisters.

painstakingly acquire knowledge that could enable us and inspire us to change our ways. Only if that knowledge begins to exert a pressure in us, and we come to feel the fellowship of all beings as potently as we feel hunger and fear, will we have any hope of creating a truly just and tolerant society, one that cherishes the land and our wild companions along with our brothers and sisters.

"In America lately, we have been carrying on two parallel conversations: one about respecting human diversity, the other about preserving natural diversity. Unless we merge those conversations, both will be futile. Our efforts to honor human differences cannot succeed apart from our effort to honor the buzzing, blooming, bewildering variety of life of earth. All life rises from the same source, and so does all fellow feeling, whether the fellow moves on two legs or four, on scaly bellies or feathered wings. If we care only for human needs, we betray the land; if we care only for the earth and its wild offspring, we betray our own kind. The profusion of creatures and cultures is the most remarkable fact about our planet, and the study and stewardship of that profusion seems to me our fundamental task."

The sculptures pictured here are by the New Mexican artists Gene and Rebecca Tobey, who worked for years in a fertile partnership creating scuptures, paintings, and drawings inspired by nature and the mythic symbolism of the North American continent. (The titles of the pieces can be found in the picture captions.) Gene died of leukemia in 2006, but Rebecca carries on their beautiful work. Please visit her website to learn more.

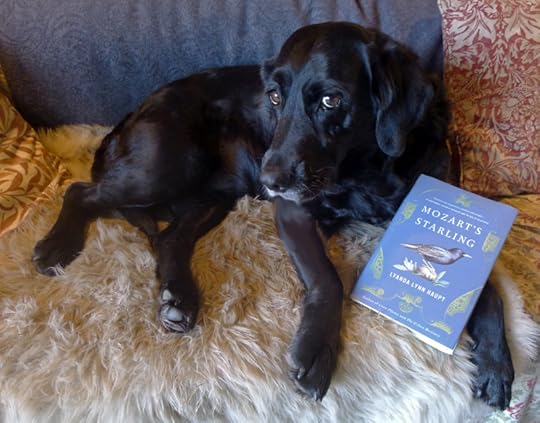

The essay quoted above is from Scott Russell Sander's Writing From the Center, which I highly recommend. My well-thumbed copy of the book is pictured below, alongside our own furry shape-shifter....

There are days when she's a wolf prowling through the woods, days when she's a grass owl nesting in the green, and days when she answers only to Little Bear. But at her core she remains her dear unique self. Just as we do, shape-shifters every one of us.

Writing from the Center by Scott Russell Sanders was published by Indiana University Press, 1997. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artists.

May 26, 2020

One more post for the feathered ones

Why I Need the Birds

by Lisel Mueller (1924-2020)

When I hear them call

in the morning, before

I am quite awake,

my bed is already traveling

the daily rainbow,

the arc toward evening;

and the birds, leading

their own discreet lives

of hunger and watchfulness,

are with me all the way,

always a little ahead of me

in the long-practiced manner

of unobtrusive guides.

By the time I arrive at evening,

they have just settled down to rest;

already invisible, they are turning

into the dreamwork of trees;

and all of us together --

myself and the purple finches,

the rusty blackbirds,

the ruby cardinals,

and the white-throated sparrows

with their liquid voices ���

ride the dark curve of the earth

toward daylight, which they announce

from their high lookouts

before dawn has quite broken for me.

Words: The poem above is from Lisel Mueller's splendid collection Alive Together: New and Selected Poems (Louisiana State University Press, 1996); all rights reserved by the author's estate. I was gutted to learn of this extraordinary poet's death earlier this year. Her work has been highly influential for me; and her kindness in donating an original poem to my Armless Maiden anthology (raising money for children at risk) will never be forgotten.

Pictures: The paintings and drawing above are by me today. All rights reserved.

May 25, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

As a follow-up to last week's music, here are a few more songs with the rustle of wings....

Above: "Seven Hundred Birds" by Monika Gromek's band Quickbeam, from Glasgow, Scotland. The atmospheric video was filmed in the hills of Cumbria.

Below: "Starlings" by Welsh composer and guitarist Toby Hay. The song first appeared on his Birds EP -- five songs inspired by starlings, ravens, curlews, and red kites. It can also be found on his fine album The Gathering, which came out last year.

Above: "The Lark" performed by singer/songwriter Kate Rusby, from South Yorkshire, with Nic Jones, based here in Devon. The song appeared on her album The Girl Who Couldn't Fky (2005).

Below: "Hour of the Blackbird" performed by Ninebarrow (Jon Whitley and Jay LaBouchardiere), from Dorset, accompanied by Lee Cuff (from Kadia) on cello. The song appeared on their album The Waters and the Wild (2018).

Above: "The Sweet Nightingale" performed by folksinger and fiddle/viola player Jackie Oates, from Staffordshire. The song appeared on her album Saturnine (2010)

Below: Lal Waterson's "The Bird," performed by Oates on her album The Joy of Living (2018).

Above: "What's the Use of Wings," written by Brian Bedford, performed by Jackie Oates and Megan Henwood, a singer/songwriter from Oxfordshire. Oates and Henwood are accompanied here by video clips of starling murmurations, and Pete Thomas on double bass.

Below: "The Wren and the Salt Air" by Scottish singer/songwriter Jenny Sturgeon (of Salt House), inspired by the wildlife and human history of St. Kilda in the Outer Hebrides. (St. Kilda was discussed in a previous post here.) I also recommend Sturgeon's album Northern Flyway with Inge Thomson (from the Shetland Isles): a musical exploration of birdsong, ecology, folklore, and themes of migration (discussed in a previous post here).

Above: "The Cuckoo" performed by British folk duo Josienne Clarke & Ben Walker on their EP The Birds (2017).

Below: "Hushabye" by the great Northumbrian piper Kathrine Tickell, and her band the Darkening. It's from their new album Hollowbone (2020), with a new video by Marry Waterson.

Images above: Starling murmurations on the Isle of Wight, photographed by Sophie Hale, 2019. (All rights reserved by the artist.)

May 24, 2020

Wild Communion

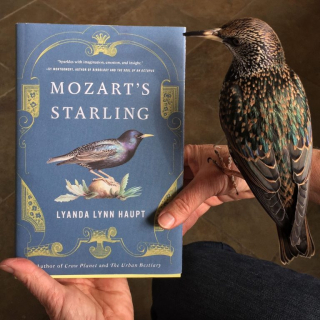

In yesterday's post, I recommended Mozart's Starling by Lyanda Lynn Haupt, a marvelous book about Mozart's bird companion (Star), the writer's own pet starling (Carmen), and reflections on this common bird, widely detested in North America for being nonnative and invasive. Today, I'd like to quote a beautiful passage from the latter chapters of the text looking at the nature of our wild relationships with the more-than-human world, a subject that often comes up in our discussions in the Mythic Arts field.

Haupt writes:

"When I set out to follow the story of Mozart and his starling, I saw in its center a shining, irresistible paradox: one of the greatest and most loved composers in all of history was inspired by a common, despised starling. Now I muse upon the many facets of this tale, and it is wonderful, yes, even more wonderful than I had imagined. But looking back at the trail that I have wandered with these kindred birds -- one in history and one in my home -- I see also that, as both humans and animals so often are, I have been tricked by my attraction to the shiny little object. For in the end, it is not the exceptionality of this story that is the true wonder. It is its ordinariness.

"In the creatures that intertwine with our lives, those we see daily and those that watch us from urban and wild places -- from between branches and beneath leaves and under eaves and stairwells and culverts and the sides of walks and pathways -- we share everything. We share breath, and biology, and blood. She share our needs for food and water and shelter. We share the imperative to mate and to give new life and to keep our young safe and warm and fed. We share susceptibility to disease and the potential to suffer and an inevitable frailty in the face of these things. We share a certain death. We share everything, constantly, every moment of the day and night, across eons. And in this shared earthly living, when we give our attention to it, we find the basis of our compassion, and our empathy for other creatures....

Each creature has its particular ways and wiles. Each being has its own presence, voice, silence, song, body, place. We are bound by our sameness and uniqueness in equal measure -- both spring from our shared being on a vital, conscious earth. This is wild communion. And it is in this recognition that we move beyond simple compassion to a more certain, more essential sense of relatedness, of kinship.

"Mozart felt this, I know. Like me, he was drawn at first to the shiny thing -- in his case it was Star's singing back to him the song he himself had written. But in his elegy poem [written upon Star's death] we see that a different relationship evolved. The bird's mimicry is not once mentioned. This is a poem to a kindred creature whose presence brought play, sound, song, joy, and friendliness to the maestro's life. And in the work that Star inspired, this is what we see too. A shared sense of mischief, music, and delight. The word kinship comes from the Old English -- of the same kind, and therefore related. Kindly and kindness also grow from this root -- the bearing toward others that kinship inspires.

"I have always thought of all creatures -- all organisms really -- as relations. Whether wandering alone in deep wilderness or just leaning against a tree growing beside an urban sidewalk, I have no difficulty feeling, as if in a dreamtime, the roots of our relatedness -- ecologically, yes, but also with an overlay of the sacred, the holy. Starlings, though pretty, were a rift in this vision. They fluttered outside this wholeness. But my thinking has evolved. Ecologically, it is true -- starlings do not belong in this country, this city; but relationally, it is not true. We live together in a tangled complexity. I listen to the starlings mimic back to me my own profound ecological shortcomings. Carmen is a creature with a body, voice, and consciousness in the world. In this, we are sisters. And all these unwelcome starlings on the grassy parking strip? Yes, they are my relations too.

"The Cartesian belief in the absolute separateness of lives, bodies, and brains maintains a foothold in the traditions of our modern culture. We see it in the ways we are pitted against one another in commerce, in education, and in the small, daily jealousies of our own minds. We see it in the ways that we continue to find it culturally acceptable to diminish animals in agriculture, in entertainment, and in scientific experimentation. And yes, when we are attentive, we find that we are not separate, not alone. We are not isolated little minds wandering on a large, indifferent earth. We are surrounded by our kin, by all of life, beings with whom we are wayfarers together. Instead of walking upon, we walk within, and this within-ness brings our imaginations to life. We are inspired -- literally "breathed upon" -- together.

"Our creativity and our connection to other beings is tangled in a beautiful etymology. The words creative and creature spring from the same Latin root, creare, "to produce, to grow, to bring into existence." It was Ged, Ursula Le Guin's beloved young wizard of Earthsea, who learned after the fall of his individual pride that the wise person is "one who never sets himself apart from other living things, whether they have speech or not, and in later years he strove long to learn what can be learned, in silence, from the eyes of animals, the flight of birds, the slow gestures of trees." Through such understanding we arrive at a new wholeness. We become more receptive and free in body and imagination, and our unique potential for creative magnificence is enlivened. We become the listening artists of our own lives and culture."

Yes, indeed.

The art today is by Scottish photographer Laurence Winram. The imagery here is from his Shadow, Conemen, and Mythologos series. Please visit Winram's website and blog to see more.

"The ancient Greeks made sense of their world not only by logic but by myth too," says the artist. "They saw it was necessary to view things in these opposite ways in order to have a balanced understanding of their lives. I feel we have moved out of that balance, unconsciously letting go of that mythic element to our lives. As a result we've lost touch with our own personal vision and creativity. We let a dogmatic scientific perspective rule everything, from our dreams to our notions of the spiritual.

"I try to reflect on this, creating images that sometimes imagine a world where logic has been sidelined by the mythic, or images that mock our need to analyse and break down those parts of our life that we should truly respond to more intuitively."

The passages above is from Mozart's Starling by Lyanda Lynn Haupt (Little, Brown & Co., 2017); all rights reserved by the author. Thanks again to William Todd Jones (via composer Hillary Tann) for passing the book on to me; and to Steve Toase for recommending Laurence Winram's work. All rights to the photogaphy above reserved by the artist.

May 23, 2020

Mozard, starlings, and the inspiration-wind

From Mozart's Starling by Lyanda Lynn Haupt:

"People always ask how I get ideas for by books. I think all authors hear this question. And, at least for me, there is only one answer: You can't think up an idea. Instead, an idea flies into your brain -- unbidden, careening, and wild, like a bird out of the ether. And though  there is a measure of chance, luck, and grace involved, for the most part ideas don't arise from actual ether; instead they spring from the metaphoric opposite -- from the rich soil that has been prepared, with and without our knowledge, by the whole of our lives: what we do, what we know, what we see, what we dream, what we fear, what we love....

there is a measure of chance, luck, and grace involved, for the most part ideas don't arise from actual ether; instead they spring from the metaphoric opposite -- from the rich soil that has been prepared, with and without our knowledge, by the whole of our lives: what we do, what we know, what we see, what we dream, what we fear, what we love....

"And as a writer, of course, I live by inspiration. I watch it come and go; when it's missing, I pray for its reappearance. I light a candle and put it in my window hoping that this little ritual might help inspiration find its way back to me, like a lover lost in a snowstorm. The word itself is beautiful. Inspire is from the Latin, meaning 'to be breathed upon; to be breathed into.' Just as I ponder the migrations of birds, I ponder the migrations of inspiration's light breeze. If it's not with me, where has it been? Who has it breathed upon while it was away, and when, and how? Over and over again, I have come to terms with the sad truth that inspiration never visits at my convenience, nor in accordance with my sense of timing, nor at the behest of my will. Most of all, the inspiration-wind has no interest whatsoever in what I think I want to write about."

Haupt is an ecophilosopher and naturalist who has has studied birds for much of her life; she has also worked as a raptor rehabilitator, and once this history became known in her neighborhood, "it seemed that all the injured birds within a fifty-mile radius had a way of finding me." So it's no surprise that birds are the focus of several of her books, including Crow Planet, Pilgrim on the Great Bird Continent, and Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds. What did surprise her was when inspiration came in the form of a starling.

In conservation circles, she explains, starlings are easily the most despised birds in all North America: a ubiquitous, nonnative species that has invaded sensitve habitats and outcompetes native birds for food and nest sites. One day as she sat at her desk, she looked out the window and saw "a plague of starlings" on a strip of grass beyond the house. Other birds find starlings intimidating, so Haupt pounded on the window to make them leave. This had little effect. "So I rapped the window harder," she writes, "and again they lifted. But this time, they turned toward the light and I was dazzled by the glistening iridescence of their breasts. So shimmery, ink black and scattered with pearlescent spots, like snow in sun. Hated birds, lovely birds. In this moment of conflicted beauty, a story I'd heard many times came to mind.

"Mozart had kept a pet starling."

"Mozart discovered the starling in a Vienna pet shop," Haupt explains, "where the bird had somehow learned to sing the motif from his newest piano concerto. Enchanted, he bought the bird for a few kreuzer and kept it for three years before it died. Just how the starling learned Mozart's motif is a wonderful musico-ornithological mystery. But there is one thing we know for certain: Mozart loved his starling. Recent examinations of his work during and after the period he lived with the bird shows that the starling influenced his music and, I believe, at least one of the opera world's favorite characters. The starling in turn was his companion, distraction, consolation, and muse. When his father, Leopold, died, Wolfgang did not travel to Salzburg for the services. When his starling died, two months later, Mozart hosted a formal funeral in his garden and composed a whimsical elegy that proclaimed his affinity with the starling's mischievousness and his sorrow over the bird's loss."

"What did Mozart learn from his bird? The juxtaposition of the hated and sublime is fascinating enough. But how did they interact? What was the source of their affinity? And how did the starling come to know Mozart's tune? I dove into research, making detailed notes on the starlings in my neighborhood. But gaps in my understanding of starling behavior remained and niggled, and within a few weeks I reluctantly realized that to truly understand what it meant for Mozart to live with a starling, I would, like the maestro, have to live with a starling of my own." And so she did.

The resulting book is Mozart's Starling, which I highly recommend: a skillful blend of musical history, natural science, and personal memoir, with meditations on creativity, migration, and so much more.

The resulting book is Mozart's Starling, which I highly recommend: a skillful blend of musical history, natural science, and personal memoir, with meditations on creativity, migration, and so much more.

"Following Mozart's starling, and mine," Haupt relates in the Introduction, "I was led on a crooked, beautiful, and unexpected path that would through Vienna and Salzburg, the symphony, the opera, ornithological labs, the depths of music theory, and the field of linguistics. It led me to outer space. It led me deep into the natural world and our constant wild animal companions. It led me to the understanding that there is more possibility in our relationships with animals -- with all the creatures of the earth, not just the traditionally beautiful, or endangered, or loved -- than I had ever imagined. And in this potential for relationship there lies our deepest source of creativity, of sustenance, of intelligence, and of inspiration."

Words: The passages above are from Mozart's Starling by Lyanda Lynn Haupt (Little, Brown & Co., 2017); all rights reserved by the author. Many thanks to William Todd Jones (via composer Hillary Tann) for passing the book on to me.

Pictures: My collage "The Luminosity of Birds" and a various "bird children" from my sketchbooks. All rights reserved.

May 22, 2020

Life as bird

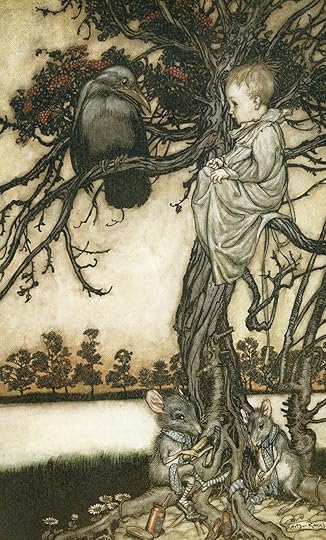

In his introduction to Beasts at Bedtime: Revealing the Environmental Wisdom in Children's Literature, Irish ecologist and poet Liam Heneghan writes this touching passage about the imaginative connection between children, birds, and animals:

"Newly arrived in the United States and setting foot on the red soils of Georgia for the very first time, Fiacha, our eldest and then a three-year-old, perched himself on top of a fire ant mound. It's a rare child who makes that mistake a second time since fire ants sting ferociously. We had moved into a small ranch house a few miles from the campus of the University of Georgia in Athens, where I was to work for four years. The house was aesthetically unremarkable. There were parched lawns to the front and rear, both of which hosted innumerable fire ant mounds. In the front yard, right outside the door, grew two desiccated shrubs. What that neighborhood lacked in conventional wildlife it made up for with feral dogs. They howled all night and packed together in the morning, leisurely hunting the neighborhood for those who, like me, were foolish enough to go walking in the early hours. It was in this unpromising location that Fiacha -- an Irish name that means 'raven,' and whose second name is Daedalus, the father of Icarus -- became a bird.

"The care and feeding of a bird who is morphologically and physically human, though psychologically somewhat avian, is not an entirely trivial undertaking. While he was in motion, there was little inconvenience to us -- he simply flapped his featherless wings as he migrated from place to place.

"He was something of a restless bird: now in the living room, now the kitchen, and now perched in his bedroom. Whenever and wherever he perched, the primaries on his wings would tremble, occasionally he would ruffle the length of his wings, and, at times, he would fold them back and tuck them close to his little body. We learned to live with the concerned glances of strangers. Feeding time could be a little strenuous, although we could entice him with shredded morsels that he would grab by his 'beak' and toss back into his mouth. Sometimes he would disappear from the house, and after those initial panicked occasions where we searched high and low for him, we knew he could be found sequestered in one of those forlorn-looking shrubs in the front yard. He would cling to a lower branch, peering out at the world through the patchy foliage. At least he was safely out of the reach of the packs of dogs and of the fire ants.

"In those early years, we read a lot about birds, looked at a lot of birds, and drew a lot of birds; and by sketching birds on folded pieces of paper and then cutting them out, we made innumerable models of birds. It lead to a later interest of his in dinosaurs, then aircraft, then military history, after which there was another thousand twists and turns in his interests. That bird now studies philosophy, but he remains an avid birder. He admitted to me recently that he occasionally writes with a quill. To this day if you look at him long enough, you may still spot his flight feathers flutter ever so slightly, even on windless afternoons."

Heneghan goes on to explain that Beasts at Bedtime was written for the parents, teachers, librarians and guardians of children who might think they are birds:

"It's possible, of course, and not at all uncommon, that your child might assume themselves to be a cat or a dog; this is a book for those families also. It's also for the family of a child I've learned of recently who alternates between a crocodile, a rhino, and a snake. When she was quite young, a friend imagined herself to be a gorilla. A child of another friend thinks he is a deep-sea shrimp that scares predators who get too close by squirting out a glowing substance. He alternates this with being a porcupine. You should give this child wide berth....

"Some children do not identify with being any animal other than the higher primates they already are. The stories that I write about here will be instructive to guardians of these children also, for it is a rare child who is not already inclined to nature.

"Central to the task of caring for your little creature is to create the most nurturing environment for them. This, quite obviously, is not as simple as attending to their peculiar physical needs. It requires a careful tending to their spirits. This later task can be assisted by the stories you tell and read to them. To help with the task, this book is intended to illustrate the thematic richness of children's stories. There is a surprising depth of environmental information in many of the titles that children find immensely appealing."

Heneghan's text covers pastoral stories, wilderness stories, urban stories, and "children on wild islands" -- ranging from fairy and folk tales to Peter Rabbit and Pooh -- and then onward to White's Forest Sauvage, Tolkien's Middle-Earth, Le Guin's Earthsea, and much more. I loved re-visiting favorite tales through the eyes of an ecosystem ecologist, and heartily recommend this charming, informative, bird-filled and beastly book.

Words: The passage quoted above is from Beasts at Bedtime: Revealing the Environmental Wisdom in Children's Literature by Liam Heneghan (University of Chicago Press, 2018). All rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: The illustrations above are by the great Golden Age book artist Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), from editions of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by J.M. Barrie, The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, Aesop's Fables, and Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll.

Related posts: Kissing the Lion's Nose (on children and animals) and Finding the way to the green (on children and nature).

May 21, 2020

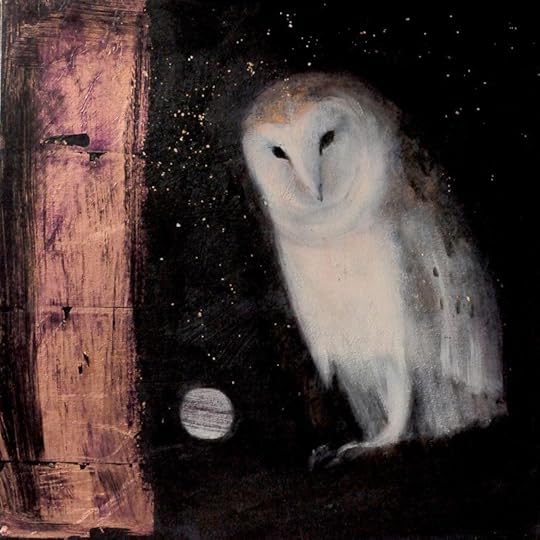

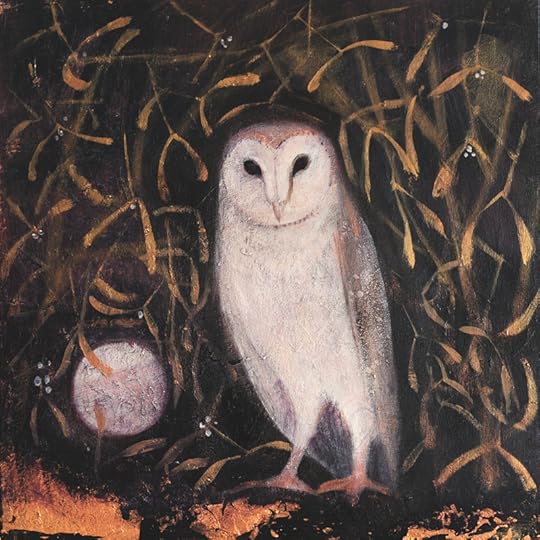

The song of owls

The little woodland behind my studio is thick with owls. I hear their cries each morning as I start my work at the break of dawn. I hear them again at the midnight hour in our little house just down the hill, the song of owls slipping the bedroom window into my dreams.

In this luminous passage from her book Dwellings, Chickasaw poet and novelist Linda Hogan follows the call of the owls who gather near her home in the American south-west:

"It was early in February, during the mating season of the great horned owls. It was dusk, and I had hiked up the back of a mountain to where I'd heard the owls a year before. I wanted to hear them again, the voices so tender, so deep, like a memory of comfort. I was halfway up the trail when I found a soft, round nest. It had fallen from one of the bare-branched trees. It was a delicate nest, woven together of feathers, sage, and strands of wild grass. Holding it in my hands in the rosy twilight, I noticed that blue thread was entwined with the other gatherings there. I pulled at the thread a little, and then I recognized it. It was a thread from one of my skirts. It was blue cotton. It was the unmistakeable color and shape of a pattern I knew. I liked it, that a thread of my life was in an abandoned nest, one that had held eggs and new life. I took the nest home. At home, I held it to the light and looked more closely. There, to my surprise, nestled into the grey-green sage, was a gnarl of black hair. It was also unmistakeable. It was my daughter's hair, cleaned from a brush and picked out in the sun beneath the maple tree, or the pit cherry where birds eat from the overladen, fertile branches until only the seeds remain on the trees.

"I didn't know what kind of nest it was, or who had lived there. It didn't matter. I thought of the remnants of our lives carried up the hill that way and turned into shelter. That night, resting inside the walls of our home, the world outside weighed so heavily against the thin wood of the house. The sloped roof was the only thing between us and the universe. Everything outside our wooden boundaries seemed so large. Filled with the night's citizens, it all came alive. The world opened in the thickets of the dark. The wild grapes would soon ripen on the vines. The burrowing ones were emerging. Horned owls sat in treetops. Mice scurried here and there. Skunks, fox, the slow and holy porcupine, all were passing by this way. The young of the solitary bees were feeding on pollen in the dark. The whole world was a nest on its humble tilt, in the maze of the universe, holding us."

The art today is by fellow owl-lover Catherine Hyde, who trained at the Central School of Art in London and now lives and works in Cornwall. Catherine has published five books (The Princess��� Blankets, Firebird, Little Evie in the Wild Wood, The Star Tree, and The Hare and the Moon), all of which I recommend. Her art is extensively exhibited in London, Cornwall, and father afield.

���I am constantly attempting to convey the landscape in a state of suspension," she says, "in order to gain glimpses of its interconnectedness, its history and beauty. Within the images I use the archetypical hare, stag, owl and fish as emblems of wildness, fertility and permanence: their movements and journeys through the paintings act as vehicles that bind the elements and the seasons together."

Please visit the artist's website to see more of her exquisite work.

The passage above is from one of my all-time favourite books, Dwellings: The Spiritual History of the Living World by Linda Hogan (W.W. Norton & Co, 1995), which I highly, highly recommend. The paintings are by Catherine Hyde. All rights to the text and art in the post reserved by the author and artist.

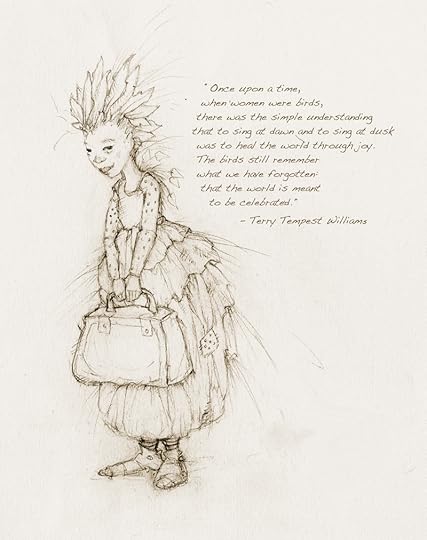

When women were birds

The quote above is from When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice by Terry Tempest Williams (Sarah Crichton Books, 2012) -- a sequel (of sorts) to Williams' equally beautiful book Refuge. Both books are meditations on family, art, voice, the natural world, and, yes, many many birds. The drawing is one of mine, called "The Strayaway Child." All rights reserved by the author and artist.

May 19, 2020

Storks in the spring

As we end our second month in the UK lock-down, here's something to celebrate: wild white storks have hatched in southern England for the first time in six centuries. Isabella Tree, co-owner of the estate where the storks are nesting, says: "There���s something so magical and charismatic about white storks when you see them wheeling around in the sky, and I love their association with rebirth and regeneration. They���re the perfect emblem for rewilding. A symbol of hope. It���s going to be amazing to have them back in the British countryside, bill-clattering on their nests in spring -- perhaps even setting up nests on our rooftops like they do in Europe. When I hear that clattering sound now, coming from the tops of our oak trees where they���re currently nesting at Knepp, it feels like a sound from the Middle Ages has come back to life."

In Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit, poet and essayist Alison Hawthorne Deming tells us:

"Stork stories go back millenia, crossing the cultures that the birds have crossed in their flight along their pilgrimage through time. Stork is a hieroglyph that transcends death in ancient Egypt, where the bird is depicted as Ba, an untranslatable concept according to Egyptologist Louis V. ��abkar, who published the first extensive study of the Ba in 1947. Ba is not unlike the Judeo-Christian idea of the soul, a duality between the material and the spiritual. It is not a constituent part of the human, but 'one of various modes of existence in which the deceased continues to live.' Ba is considered to 'represent the man himself, the totality of his physical and psychic capabilities.' In gods, Ba is the embodiment of the divine powers; in kings, the embodiment of kingly powers; and in citizens Ba is the embodiment of vital force.

"Ba has a quantum strangeness, interweaving the very notions of living and dead. It frees itself of the body at death but maintains contact. The Ba of the deceased man, depicted as a stork on the papyrus of Nebqed, flies down the shaft of the tomb to deliver food (a whole fish!) and drink to sustain his very own mummy. In this context 'living' and 'dead' conflate and confuse like 'particle' and 'wave' in the study of light. Elsewhere Bas are depicted as falcon-headed humans attending as servants or as a human-headed stork perched calmly on the arm of a scribe. But it is the image of the story as Ba flying down the shaft of the tomb to bring life-giving nourishment to the dead that owns me. The Ba flies on the papyrus on stairs that are flanked by rows of a scribes careful hieroglyphic inscriptions. I imagine the hand that inked that bird, the scribe who chose to make everything else on the page -- hieroglyphs, sarcophagus, cheetah pelt -- clear and heavily inked, while this Ba, performing the most important task of bringing the promise of the renewal to the realm of the dead, is inked with so delicate a hand that the image is barely perceptible. Such is the challenge of speaking of the 'soul.'

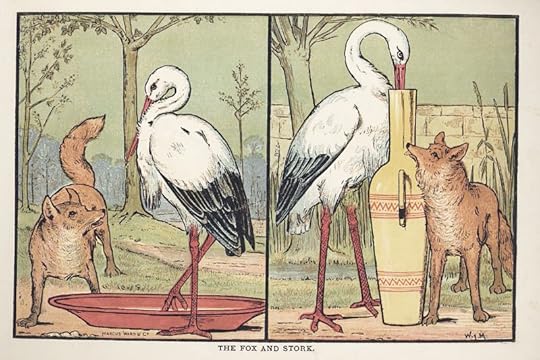

"Stork is a fable of moral instruction in ancient Greece. Aristotle wrote that 'it is a common story of the stork that the old birds are fed by their grateful progency.' Stories tell that a stork will carry an aged parent on its back when it has finally lost its feathers and is unable to fly, a lesson in filial duty. Aesop, or the unnamed scribe who gathered the tales attributed to that name, tells the tale of the bird catcher and the stork. The bird catcher has set his nets for cranes, and he watches from a distance. A stork lands amid the cranes and the bird catcher captures her. She begs him to release her, saying that far from harming men, she is very useful, for she eats snakes and other reptiles. The bird catcher replies, 'If you are really harmless, then you deserve punishment anyway for landing among the wicked.' The moral: 'We, too, ought to flee from the company of wicked people so that no one takes us for the accomplice of their wrongdoing.' This particular fable had some legal backup. In ancient Thessaly, a law prohibited the killing of storks because of their usefulness in killing snakes.

"In another Aesop fable, the fox and the stork are on visiting terms and seem to be very good friends. So the fox invites the stork to dinner. For a joke he serves her soup in a shallow dish from which the fox can easily lap but the stork can only wet the tip of her long bill. 'I am sorry,' says the fox, 'that the soup is not to your liking.'

"'Pray do not apologize,' says the stork.

"She returns the dinner invitation. When the fox arrives, the meal is brought to the table contained in a long-necked jar with a narrow mouth, into which the fox cannot insert his snout. All he can do is lick the outside of the jar.

"'I will not apologize for the dinner,' says the stork. 'One bad turn deserves another.' It is a tale of skillful means.

"Lessons in skillful means, or, in Sanskrit, up��ya, come from Mah��y��na Buddhism, a school of Buddhism that originated in India. And it is no surprise to see the spirit of ancient India embodied in an ancient Greek fable, because Aesop gathered stories from the same sources as did The Panchatantra, India's age-old treasure trove of animal stories that came up through the oral tradition and were first recorded some fifteen hundred years ago. This tradition influenced Aesop's and La Fontaine's fables, the tales of the Arabian Nights, and Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. They are stories of 'wise conduct' meant to 'awaken the intelligence.' Storks and stories share the same migratory urge.

"Storks in the great American marketplace carry forward one of the most pervasive associations with the bird: its relationship to the arrival of human babies. Baby announcements, greeting cards, wrapping paper, baby lawn ornaments and diaper services all boast the brand. Stork carries a newborn in a downy sling draped from its long bill. German folklore tells that storks find babies in caves or marshes then carry them in baskets on their backs or in their beaks into human houses. Sometimes the babies are dropped down the chimney. If a baby arrives disabled or stillborn, the stork may have dropped it on the way to the house. Households could leave sweets on the windowsill to give notice they wanted a child. Slavic folklore tells of storks bringing unborn souls from the old paradise of the pagan religion in spring.

"In spring, white storks, flying from Africa and over Mecca, arrive in eastern Europe during the season when the old pagan fertility rituals of pole dancing and wreath strewing and forest coupling would be performed. Call it synchronicity that great and graceful white birds would arrive and join the joviality each each year, making it easy for imagination -- that great coupling force between inner and outer reality -- to fuse the bird with the love of life and promise of resilience that is what spring means and has meant in temperate climes for aeons."

Words: The passage above is from Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit by Alison Hawthorn Deming, whose gorgeous work comes from the edgelands between the arts and sciences. Zoologies was published by Milkweed Editions (2014); all rights reserved by the author.

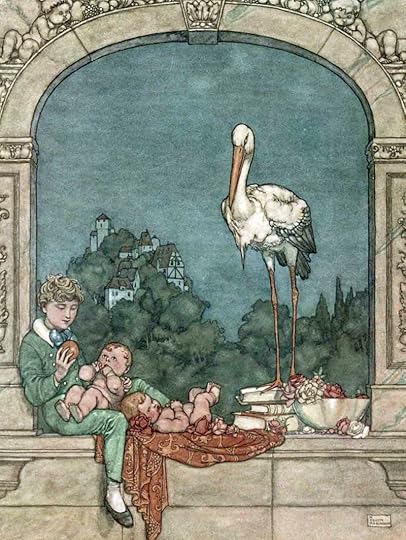

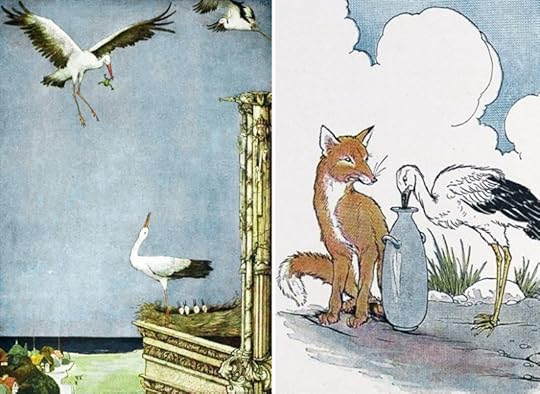

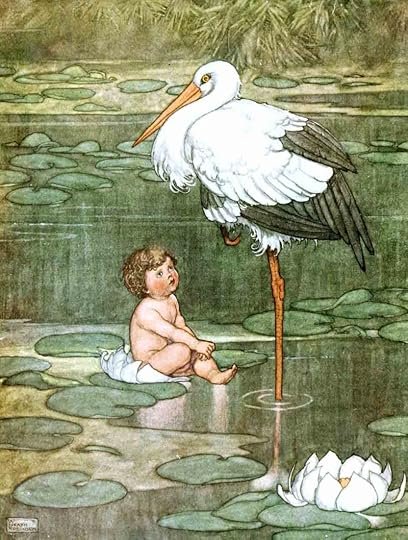

Pictures: Hans Christian Andersen's "The Storks" illustrated by William Heath Robinson (1872-1944), Ba (the soul) bringing sustenance on an ancient Egyptian papyrus, "The Storks" illustrated by Dugald Stuart Walker (1883-1937), "The Storks" illustrated by Harry Clarke (1889-1931), Aesop's "The Fox and the Stork" illustrated by Milo Winter (1888-1956), "The Fox and the Stork" illustrated by Walter Crane (1845-1915), two illustrations from Hans Christian Andersen's "The Marsh King's Daughter" and two other stork drawings by William Heath Robinson.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers