Terri Windling's Blog, page 34

June 7, 2020

The animals returning

"Animals Are Entering Our Lives" by Liesel Mueller

���I will take care of you,��� the girl said to her brother, who had been turned into a deer. She put her golden garter around his neck and

made him a bed of leaves and moss." - from an old tale

Enchanted is what they were

Enchanted is what they were

in the old stories, or if not that,

they were guides and rescuers of the lost,

the lonely, the needy young men and women

in the forest we call the world.

That was back in a time

when we all had a common language.

Then something happened. Then the earth

became a place to trample and plunder.

Betrayed, they fled to the tallest trees,

the deepest burrows. The common language

became extinct. All we heard from them

were shrieks and growls and wails and whistles, nothing we could understand.

nothing we could understand.

Now they are coming back to us,

the latest homeless, driven by hunger.

I read that in the parks of Hong Kong

the squatter monkeys have learned to open

soft drink bottles and pop-top cans.

One monkey climbed an apartment building

and entered a third-floor bedroom.

He hovered over the baby���s crib

like a curious older brother.

Here in Illinois the gulls swarm over the parking lots

the gulls swarm over the parking lots

miles from the inland sea,

and the Canada geese grow fat

on greasy leftover lunches

in the fastidious, landscaped ponds

of suburban corporations.

Their seasonal clocks have stopped.

They summer, they winter. Rarer now

is the long, black elegant V

in the emptying sky. It still touches us,

though we do not remember why.

But it���s the silent deer who come

and eat each night from our garden,

as if they had been invited. They pick the tomatoes and the tender beans,

They pick the tomatoes and the tender beans,

the succulent day-lily blossoms

and dewy geranium heads.

When you labored all spring,

planting our food and flowers,

you did not expect to feed

an advancing population

of the displaced. They come,

like refugees everywhere,

defying guns and fences

and risking death on the road

to reach us, their dispossessors,

who have become their last chance.

Shall we accept them again?

Shall we fit them with precious collars?

They scatter their tracks around the house,

closer and closer to the door,

like stray dogs circling their chosen home.

(from Alive Together: New and Selected Poems, 1996)

German-American poet and translator Lisel Mueller left us in February, at the age of 96. Learning of her death, I pulled her books down off the shelves and have been taking them with me on my walks with Tilly, stopping beneath a favourite tree, or by the stream, or at the crest of the hill to re-read her life's work...marvelling again at how fine it is, and how much of it has steeped into my dreams and language over the years.

The piece above is Mueller's folkloric response to Phillip Levine's "Animals Are Passing from Our Lives" (named for a line in an Isak Dinesen interview). The Levine poem was published in 1968, but still resonates in our own age of factory farming and ecological crisis; while Mueller's response, published in 1996, seems remarkably pertinent now, in the "great pause" of the global pandemic, as wildlife resurges and reclaims space usually dominated by humankind.

(For a previously posted Mueller poem, "Why I Need the Birds," go here.)

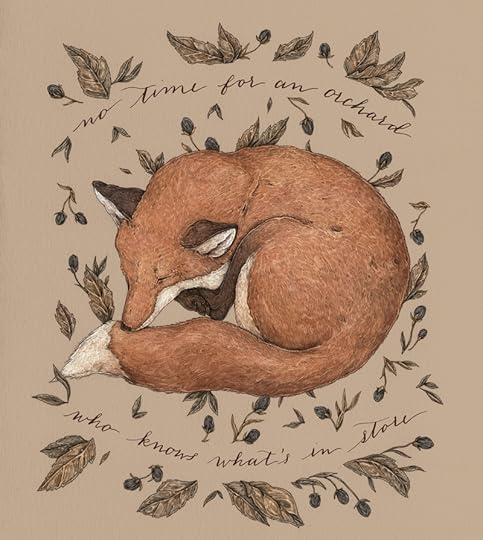

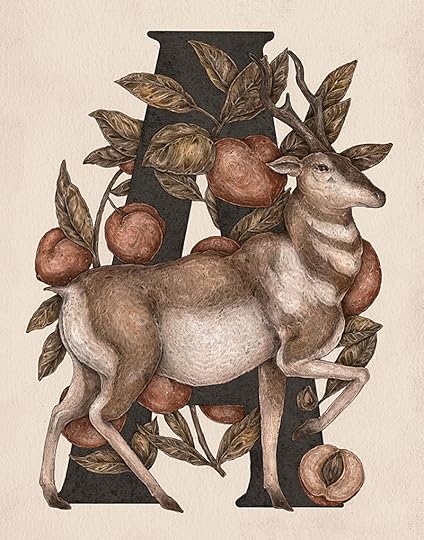

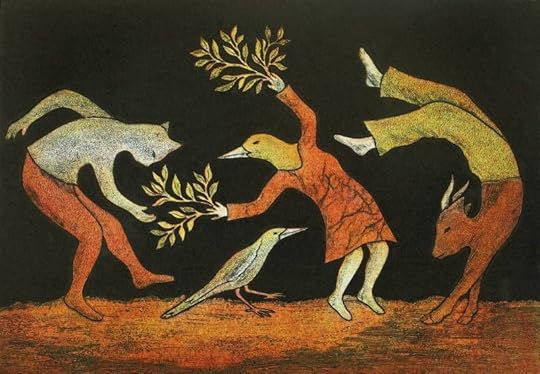

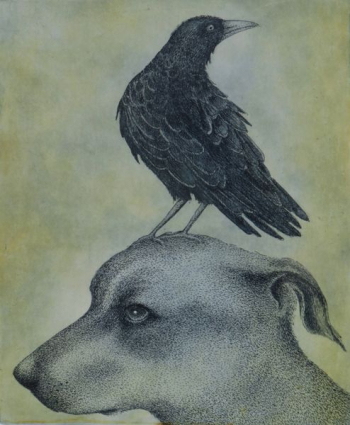

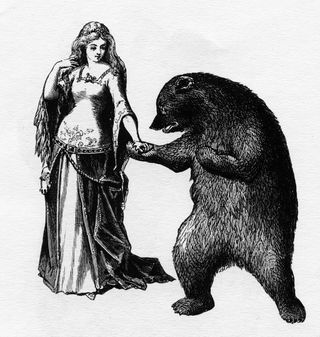

The art today is by Jessica Roux, whose work (animal lover that I am) I just adore. Raised in the woodlands of North Carolina, Roux studied at the Savannah College of Art & Design in Georgia, and now works as a freelance illustrator and stationary designer based in Nashville.

"I can���t get enough of history," she says. "Old lithographs and studies by early naturalists are some of my favorite things. I love medieval bestiaries and the early Northern Renaissance. I���m also really inspired by nature. There are just so many strange plants and animals out there that I want to know more about."

You can see more of Roux's art in a previous post, Skunk Dreams, as well as on the artist's beautiful website.

"Animals Are Entering Our Lives" is from Alive Together: New and Selected Poems by Lisel Mueller (Louisiana State University Press, 1996). All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artist and the author's estate.

June 6, 2020

Hen Wives, Spinsters, and Lolly Willowes

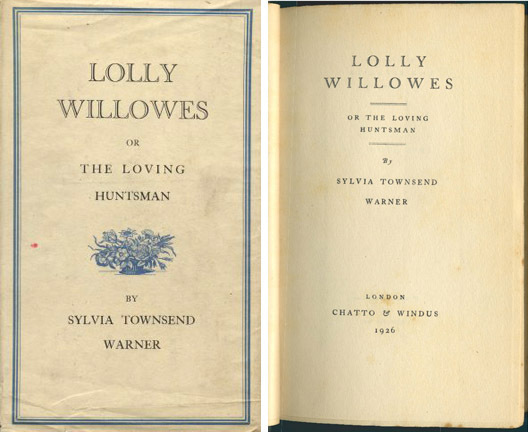

One of my favourite mid-20th century writers is Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978), who publish seven novels during her life, as well as sparkling short stories and poetry, and a biography of T.H. White. This week, my friend (and Modern Fairies colleague) Carolyne Larrington has produced a podcast on Warner's Lolly Willowes and Kingdoms of Elfin, which I highly recommend. You'll find it here, as part of Oxford University's Fantasy Literature series. Now here's a post from the Myth & Moor archives on some of the folklore and social history underlying Lolly Willowes...

In the colored fairy books of Andrew Lang (The Red Fairy Book, The Blue Fairy Book, etc.), there is a figure who has always intrigued me: the Hen Wife, related to the witch, the seer, and the herbalist, but different from them too: a distinct and potent archetype of her own, an enchanted figure beneath a humble white apron. We find her dispensing wisdom and magic in the folk tales of the British Isles and far beyond (all the way to Russia and China): a woman who is part of the community, not separate from it like the classic "witch in the woods"; a woman who is married, domesticated like her animal familiars, and yet conversant with women's mysteries, sexuality, and magic.

Writer and mythographer Sharon Blackie describes the Hen Wife like this:

"If you look up the definition of ���henwife��� in most dictionaries, you���ll find it given as something along the lines of ���woman who keeps poultry���. But that isn���t it at all: a henwife is so much more than that, as so many folk and fairytales from Ireland and Scotland show. In those tales, the henwife is often a herbalist or a healer, and is  always synonymous with the Wise Old Woman archetype: the Cailleach personified. Think, for example, of the fine Scottish tale ���Kate Crackernuts,��� about the henwife and her cauldron of wisdom. Or the old Irish tale about three sisters, ���Fair, Brown and Trembling.��� The fact that the henwife also keeps hens is part and parcel of this archetype, but although the heroine of the story may go to her looking simply for eggs, she always comes away with rather more than she bargained for."

always synonymous with the Wise Old Woman archetype: the Cailleach personified. Think, for example, of the fine Scottish tale ���Kate Crackernuts,��� about the henwife and her cauldron of wisdom. Or the old Irish tale about three sisters, ���Fair, Brown and Trembling.��� The fact that the henwife also keeps hens is part and parcel of this archetype, but although the heroine of the story may go to her looking simply for eggs, she always comes away with rather more than she bargained for."

Colleen Szabo, writing in Cabinet des F��es, views the Hen Wife through a Jungian lens. She is, says Szabo, "a combination of the old bird goddesses and the figure we now call 'witch'; a crone or wise woman who knows of the inner life, of natural processes and developments, of all their alchemical magic. She is also a keeper of knowledge about a woman���s sexuality; the old tradition of a 'hen���s night' is currently being revived. In that tradition, the night before a wedding, older and wiser hen-wives teach the wife-to-be about sexuality, including pregnancy, all of which falls within the overall category of creative power, of course. Whatever our creative genres might be, their products can always be symbolized by the metaphor of the child, including our creative efforts to renew and transform ourselves."

My favorite depiction of the Hen Wife is in this gorgeous passage from the novel Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978):

"Laura never became as clever with the birds as Mr. Saunter. But when she had overcome her nervousness, she managed them well enough to give herself a great deal of pleasure. They nestled against her, held fast in the crook of her arm, while her fingers probed among the soft feathers and rigid quills of their breasts. She liked to feel their acquiescence, their dependence upon her. She felt wise and potent. She remembered the henwife in fairy tales, she understood now why kings and queens resorted to the henwife in their difficulties. The henwife held their destinies in the crook of her arm, and hatched the future in her apron. She was sister to the spaewife, and close cousin to the witch, but she practiced her art under cover of henwifery; she was not, like her sister and her cousin, a professional. She lived unassumingly at the bottom of the king's garden, wearing a large white apron and very possibly her husband's cloth cap; and when she saw the king and queen coming down the gravel path she curtseyed reverentially, and pretended it was eggs they had come about. She was easier to approach than the spaewife, who sat on a creepie and stared at the smoldering peats till her eyes were red and unseeing; or

the witch, who lived alone in the wood, her cottage window all grown over with brambles. But though she kept up this pretense of homeliness she was not inferior in skill to the professionals. Even the pretence of homeliness was not quite so homely as it might seem. Laura knew that the Russian witches live in small huts mounted upon three giant hen's legs, all yellow and scaly. The legs can go; when the witch desires to move her dwelling the legs stalk through the forest, clattering against the trees, and printing long scars upon the snow.

"Following Mr. Saunter up and down between the pens, Laura almost forgot where and who she was, so completely had she merged her personality into the henwife's. She walked back along the rutted track and down the steep lane as obliviously as though she were flitting home on a broomstick."

I first discovered Sylvia Townsend Warner's fiction through Kingdoms of Elfin (a collection of the adult fairy stories as dry and fizzy as the best champagne), but Lolly Willowes, when I first read it back in my 20s, seemed altogether different. I'm embarrassed now to admit that I found the novel slight and unmemorable, almost twee, and it wasn't until a later re-reading that I finally understood it as the masterpiece it is. I had been too young for Lolly Willows the first time, and too ignorant of the social context in which Townsend Warner was writing in the 1920s: the restricted lives of "spinisters" in Victorian and Edwardian England. "The issue that the novel tackles head-on is that of gender," explains another Townsend Warner fan, contemporary British novelist Sarah Waters:

"In the 1910s and 20s British sexual mores were shaken up as never before: the war saw women taking on new jobs, gaining new responsibilities and freedom, and, though the majority of the jobs were savagely withdrawn with the return to peace, many of the liberties remained; in 1918, partly as a recognition of their contribution during the years of conflict, women were at last granted the vote. For the first decade of its life, however, the new franchise was an incomplete one, available only to women over 30 who were also householders or married to householders (which meant that single women such as Laura, middle-aged but financially dependent on male relatives, remained without it), and there was still huge pressure on women to conform to social norms.

"The recent tragic loss of so many young male lives had inflamed existing tension over the idea of the 'surplus woman' and, with postwar anxiety about British 'racial health' prompting celebrations of family life and maternity, the spinster -- a benign if dowdy figure in 19th-century culture -- was being subtly redefined as a social problem. The popularisation of Freudian ideas about sexual repression only added to her woes, pathologising elderly virgins as chronically unfulfilled. Many novelists of the period responded to this ��� some, such as Clemence Dane, with representations of emotionally vampiric single women, which reinforced the new stereotypes, but others, such as Radclyffe Hall, Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain, with more sensitivity to the pressures faced by ageing, unmarried daughters, and more sympathy for them in their efforts to follow non-traditional paths. Two fascinating novels that particularly resemble Lolly Willowes, and which Townsend Warner could be said effectively to have rewritten, are W.B. Maxwell's Spinster of this Parish (1922) and F.M. Mayor's The Rector's Daughter (1924).

"Like Townsend Warner, Maxwell and Mayor chose as their subjects unmarried women of the late-Victorian age -- that is, the final generation to have assumed as a matter of course that its single daughters would remain in the family home, dutifully servicing the needs of senior relatives. Again like her, they produced novels that are intensely alive to the contrast between the unglamorous exteriors of their 'old maid' heroines and the women's actual, deeply passionate, emotional lives. But the titles of the three novels reveal a significant difference. As phrases, 'spinster of this parish' and 'the rector's daughter' testify to the ways in which women are often occluded by social and familial roles. Lolly Willowes, by contrast, is a statement of individuality. Laura's journey, too, is very different from that of Maxwell's and Mayor's heroines, the former of whom spends decades as the unacknowledged mistress of a celebrated explorer, and is finally rewarded by marriage to him, while the latter dies after a short but 'useful' life, with her passionate love for a clergyman unfulfilled.

"For the first half of Townsend Warner's novel, Laura looks set to follow their example. A tomboy in childhood, she is soon 'subdued into young-ladyhood,' and after the death of her parents she joins the London household of her unimaginative brother, Henry, where she becomes the spinster 'Aunt Lolly,' slightly pitied, slightly patronised, but 'indispensable for Christmas Eve and birthday preparations' -- an embodiment, in other words, of an old-fashioned female tradition for which her up-to-the-minute niece,

Fancy, who has driven lorries during the war, has fine, flapperish contempt. But Laura has depths unsuspected by her deeply conventional relatives, and with her move to Great Mop she grows ever more subversive. She quietly rejects her family. She refuses to be defined by her relationships with men. She breaches the social barriers between gentry and working people. And, though she enjoys being part of the Great Mop community, her intensest pleasures are solitary ones. Again looking forward to Virginia Woolf, the novel asserts the absolute necessity of 'a room of one's own', and Laura gains a clear-sighted understanding of the combined financial and cultural interests that serve to keep women in domestic, dependent roles: 'Society, the Law, the Church, the History of Europe, the Old Testament . . . the Bank of England, Prostitution, the Architect of Apsley Terrace, and half a dozen other useful props of civilisation' have robbed her of her freedom just as effectively as have her patronising London relatives. It is this analysis that informs her conversation with Satan near the end of the novel, in which she unfolds her memorable vision of women as sticks of dynamite, 'long[ing] for the concussion that may justify them.' If women, Townsend Warner implies, are denied access to power through legitimate means, they will turn instead to illegitimate methods -- in this case to Satan himself, who pays them the compliment of pursuing them and then, having bagged them, performs the even more valuable service of leaving them alone."

I highly recommended reading Waters' excellent essay in full if you can track down a copy. ("Sylvia Townsend Warner: The Neglected Writer," The Guardian, March 2012.)

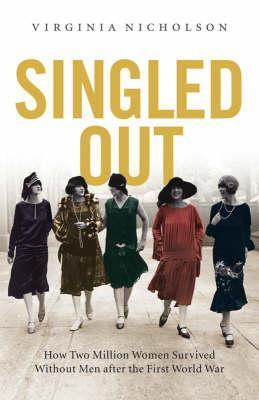

I think if I was teaching Lolly Willowes today, I would first ask students to read Singled Out by Virginia Nicholson, an absolutely engrossing book about single women in Britain between the wars, which I can't recommend highly enough. (All of Nicholson's books on social history are just terrific.)  It's also interesting to read Townsend Warner's fiction with some knowledge of her fascinating life as a feminist, leftist, and lesbian (she was in a long-term relationship with fellow writer Valentine Ackland) at a time when this was far from the norm for respectable "lady writers." She loved living in the countryside, and some of her best stories take place in rural settings -- but they are so much more than charming tales of villages and vicarages; beneath the mannered surface they contain a biting wit, deep wisdom, and sharp social critique, �� la Jane Austen. For those who would like to learn more about the writer, there's a good biography of Townsend Warner by Claire Harman, various volumes of the author's lively and erudite correspondence, plus a lovely memoir by Townsend Warner's wife (or so she'd be acknowledged today), Valentine Ackland: For Sylvia: An Honest Account.

It's also interesting to read Townsend Warner's fiction with some knowledge of her fascinating life as a feminist, leftist, and lesbian (she was in a long-term relationship with fellow writer Valentine Ackland) at a time when this was far from the norm for respectable "lady writers." She loved living in the countryside, and some of her best stories take place in rural settings -- but they are so much more than charming tales of villages and vicarages; beneath the mannered surface they contain a biting wit, deep wisdom, and sharp social critique, �� la Jane Austen. For those who would like to learn more about the writer, there's a good biography of Townsend Warner by Claire Harman, various volumes of the author's lively and erudite correspondence, plus a lovely memoir by Townsend Warner's wife (or so she'd be acknowledged today), Valentine Ackland: For Sylvia: An Honest Account.

And this brings us back to the Hen Wife -- that figure of magic who dwells comfortably among us, not off by the crossroads or in the dark of the woods; who is married, not solitary; who is equally at home with the wild and domestic, with the animal and human worlds. She is, I believe, among us still: dispensing her wisdom and exercising her power in kitchens and farmyards (and the urban equivalent) to this day -- anywhere that women gather, talk among themselves, and pass knowledge down to the next generations.

And Hen Husbands? What is their role in folklore, fairy tales, and daily life? I confess I do not know. Those are Men's Mysteries, hidden and ancient, and not for the likes of me to speak of....

Words: The passage by Sharon Blackie is from "The Henwife" (The Art of Enchantment, October 2014). The passage by Colleen Szabo is from "Katie Crackernuts: The Hen-Wife and her Cauldron of Wisdom" (Cabinet des F��es, July 2011). The passage by Sylvia Townsend Warner is from her novel Lolly Willowes, first published in 1926. The passage by Sarah Waters is from "Sylvia Townsend Warner: the neglected writer" (The Guardian, March 2012). All rights reserved by the authors. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in February 2015.

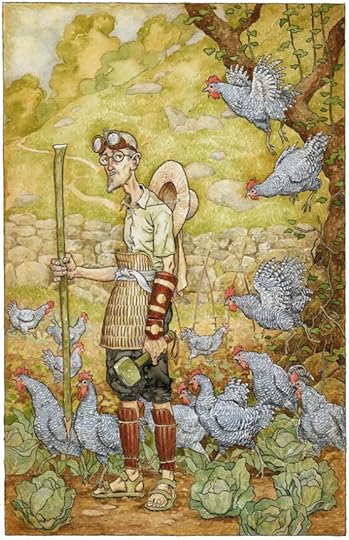

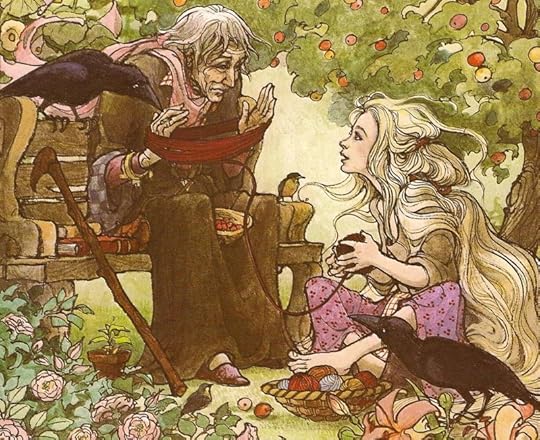

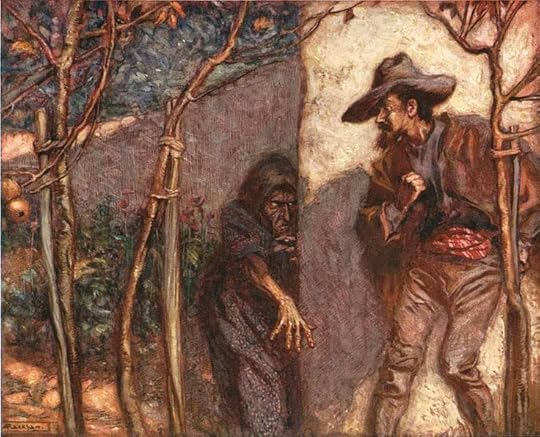

Pictures:

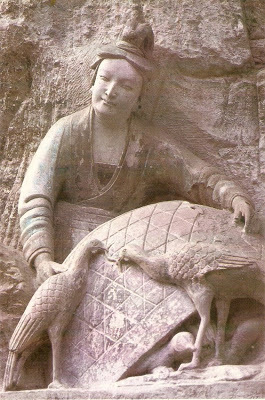

a folktale illustration by Vladislav Erko; "The Hen Wife" by Helen G. Stevenson (circa 1930s); a Danzu carving of a Chinese hen wife; "The Hen Wife" by Charles Sims (1872-1928); a nursery rhyme illustrated by Walter Crane (1845-1915); "Baba Yaga" (from Russian folklore) by Rima Staines; a Mother Goose illustration, artist unknown; a photograph of Sylvia Townsend Warner; the first edition of Lolly Willowes; a stereotypical Victorian image of a spinster by English painter Walter Dendy Sadler (1854-1923); an 18th century spinster by Thomas Cheesman (1760-1834) - reminiscent of the fact that the term was once used for all women who spin, card, and weave, rather than as a pejorative term for unmarried women; a decoration by Walter Crane (1845-1915); and "Samurai Chicken Defender" by my Chagford neighbor David Wyatt, from his "Mythic Village" series. All rights reserved by the artists or their estates.

June 5, 2020

The Handless Maiden

...with art by Jeanie Tomanek

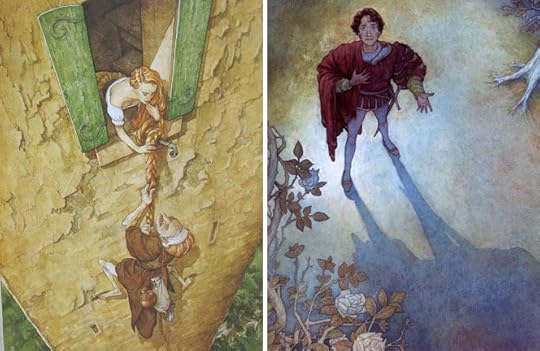

After months of pandemic lockdown, "isolation" themes in fairy tales have taken on new meaning and relevance. All of us who have been isolating at home, shut away from the world, are sister to Rapunzel now, brother to the Beast in his woodland castle, waiting for someone to break the spell of Covid-19 and restore us to life as we knew it. But fairy tales are not stories of restoration, they are stories of transformation. They say: Yes, you can escape the witch, flee from the tower, emerge from the woods and regain your humanity...but your life and your world won't be the same. You are different now. There's no going back. It is time to forge something new.

Yesterday, we discussed Maiden-in-a-Tower tales, and isolation as a form of imprisonment. Today, let's look at The Handless Maiden (also known as The Armless Maiden, The Girl Without Hands, and Silver Hands), in which an isolated forest hut is a place of sanctuary and, ultimately, of healing.

Yesterday, we discussed Maiden-in-a-Tower tales, and isolation as a form of imprisonment. Today, let's look at The Handless Maiden (also known as The Armless Maiden, The Girl Without Hands, and Silver Hands), in which an isolated forest hut is a place of sanctuary and, ultimately, of healing.

In this tale, a miller's daughter loses her hands as the result of a foolish bargain her father has made with the devil. (In darker variants, it is because she will not give in to incestuous demands.) She then leaves home, makes her way through the forest, and ends up foraging for pears (a fruit symbolic of female strength) in the garden of a tender-hearted king -- who falls in love, marries her, and gives her two new hands made of silver. The young woman gives birth to a son -- but this is not the usual happy ending to the story. The king is away at war and the devil interferes once again (or, in some versions, a malicious mother-in-law), tricking the court into casting both mother and child back into the forest.

The Handless Maiden then encounters an angel who leads her to a hut deep in the woods. Her human hands are magically restored during this time of forest retreat. When her husband returns from the war, learns that she's gone, and comes to fetch his wife and child home, she insists that he court her all over again, as the new woman she is now. Her husband complies -- and then, only then, does the tale conclude happily. The Handless Maiden's transformation is now complete: from wounded child to whole, healed woman; from miller's daughter to queen.

In her classic book The Feminine in Fairy Tales, Jungian scholar Marie-Louise von Franz compared the Handless Maiden's time of solitude in the woods to that of religious mystics seeking communion with god through nature.

"In the Middle Ages, there were many hermits," she noted, "and in Switzerland there were the so-called Wood Brothers and Sisters. People who did not want to live a monastic life but who wanted to live alone in the forest had both a closeness to nature and also a great experience of spiritual inner life. Such Wood Brothers and Sisters could be personalities on a high level who had a spiritual fate and had to renounce active life for a time and isolate themselves to find their own inner relationship to God. It is not very different from what the shaman does in the Polar tribes, or what the medicine men do all over the world, in order to seek immediate personal religious experience in isolation."

In other versions of the Handless Maiden narrative, the young queen's time in the woods is not solitary. The angel (or "white spirit") leads her to an inn at the very heart of the forest, where she's taken in by gentle "folk of the woods." (It's not always made clear whether they are human or magical beings.) The queen stays with them for a full seven years (a traditional period of time for magical/shamanic initiation in ancient Greece and other cultures world-wide), during which time her hands slowly re-grow.

In her essay "Healing the Wounded Wild," Kim Antieau uses this variant of the story to reflect on illness, the healing process, and the ways our relationship with the natural world impacts both physical and psychic health. "In many cultures," she writes, "the prescription for chronic illness was a stay in the country (not necessarily the wild country). In ancient Greece, the chronically ill went to Asklepian Temples for relief. The priests created tenemos ��� sacred space ��� for the patient to help facilitate healing. The ill went to the temples and prepared with purification and ritual for a healing dream. Then the patient went to the abaton ��� the sleeping chamber ��� and dreamed. Often the dreams either healed the patients or told them of a remedy which would heal them.

"Today, practitioners of integrated medicine believe the body wants to heal, and the patient needs the time, encouragement, support and space to be able to get well. In many instances the time, encouragement, and support can be found, but wild spaces are lacking. Silvia [the Handless Maiden] was able to travel deep into a wild place. Where do we go? Where do the wild things go (including human beings) when no wild remains?"

Midori Snyder comes at the story from a different angle in her luminous article "The Armless Maiden and the Hero's Journey," examining the tale, in its various forms, as a classic rite-of-passage narrative.

When such stories are devised for young men, she notes, the hero typically sets off from home seeking adventure or fortune in the unknown world, where the fantastic waits to challenge him. "Along the journey, his worth as a man and as a hero is tested. But when the trials are done, he returns home again in triumph, bringing to his society new-found knowledge, maturity and often a magical bride....

"While no less heroic, how different are the journeys of young women. In folktales, the rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood is confirmed by marriage and the assumption of adult roles. In traditional exogamous societies, young women were required to leave forever the familiar home of their birth and become brides in foreign and sometimes faraway households. In the folktales, a young girl ventures or is turned out into the ambiguous world of the fantastic, knowing that she will never return home. Instead at the end of a perilous and solitary journey, she arrives at a new village or kingdom. There, disguised as a dirty���faced servant, a scullery maid, or a goose girl, she completes her initiation as an adult and, like her male counterpart, brings to her new community the gifts of knowledge, maturity, and fertility."

Although fairy tales have been known as children's stories from roughly the 19th century onward, older versions of these same narratives (aimed at older audiences) looked unflinchingly at the darkest parts of life: at poverty, hunger, abuse of power, domestic violence, incest, rape, the sale of young daughters to the highest bidder under the guise of arranged marriages, the effects of remarriage on family dynamics, the loss of inheritance or identity, the survival of treachery or calamity. In rite-of-passage tales devised for young women, the heroes don't tend to ride merrily off into the forest in search of fame and fortune, they are usually driven there by desperation; the forest, despite its perils, is a place of refuge from worse dangers left behind.

The Handless/Armless Maiden is not a passive princess in the old Disney mold, waiting for romance to rescue her. She finds her own way to the orchard of a king in her search of food, and although she agrees to marry him, a royal wedding is not the conclusion of her story, it's the half-way point. "It is a narrative with a strange hiccup in the middle," Midori points out. "The brutality of the opening scene seems resolved as the Armless Maiden is rescued in a garden and then married to a compassionate young man. But she has not completed her journey of transformation from adolescence to adulthood. She is not whole, not the girl she was nor the woman she was meant to be. The narratives make it clear that without her arms, she is unable to fulfill her role as an adult. She can do nothing for herself, not even care for her own child.

"Conflict is reintroduced into the narrative to send the girl back on her journey of initiation in the woods. There the fantastic heals her, and she returns reborn as a woman. Every narrative version concludes with what is in effect a second marriage. The woman, now whole, her arms restored by an act of magic, has become herself the magic bride, aligned with the creative power of nature. She does not return immediately to her husband but waits with her child in the forest or a neighboring homestead for him to find her. When he comes to propose marriage this second time, it is a marriage of equals, based on respect and not pity.

"I have come to believe," Midori continues, "that robust narratives such as the Armless Maiden speak to women not only when they are young and setting out on that first rite of passage, but throughout their lives. In Women Who Run With the Wolves, psychologist Clarissa Pinkola Est��s presents a fascinating analysis of this tale, demonstrating the guiding role the armless maiden plays in a woman's psychic life:

" 'The Handless Maiden is about a woman's initiation into the underground forest through the rite of endurance. The word endurance sounds as though it means "to continue without cessation," and while this is an occasional part of the tasks underlying the tale, the word endurance also means "to harden, to make robust, to strengthen," and this is the principal thrust of the tale, and the generative feature of a woman's long psychic life. We don't just go on to go on. Endurance means we are making something.'

"To follow the example of the armless maiden," Midori concludes, "is an invitation to sever old identities and crippling habits by journeying again and again into the forest. There we may once more encounter emergent selves waiting for us. In the narrative, the Armless Maiden sits on the bank of a rejuvenating lake and learns to caress and care for her child, the physical manifestation of her creative power. Each time we follow the Armless Maiden she brings us face to face with our own creative selves."

Poet Vicki Feaver has also reflected on the story in relationship to creativity. In an interview in Poetry Magazine, Feaver discusses her poem "The Handless Maiden," inspired by the fairy tale :

"The story is that the girl���s hands are cut off by her father and she is given silver hands by the king who falls in love with her. Eventually, she goes off into the forest with her child and her own hands grow back. In the Grimms' version it is because she���s good for seven years. But there���s a Russian version which I like better where she drops her child into a spring as she bends down to drink. She plunges her handless arms into the water to save the child and it���s at that moment that her hands grow. I read a psychoanalytic interpretation by Marie Louise von France in her book, The Feminine in Fairytales in which she argues that the story reflects the way women cut off their own hands to live through powerful and creative men. They need to go into the forest, into nature, to live by themselves, as a way of regaining their own power. The child in the story represents the woman���s creativity that only the woman herself can save. This was such a powerful idea that I had to write about it. It took me three years to find a way of doing it. In the end I chose the voice of the Handless Maiden herself -- as if I was writing the poem with the hands that grew at the moment that she rescued her work, her child.

"I suppose I go through the process of endlessly cutting off my hands and having to grow them again. You ask if I���ve found any strategies for writing. Only to go away on my own, to be myself, and just to write."

"Fairy tales are journey stories," says Ellen Steiber (in a beautiful essay on the fairy tale Brother and Sister). "They deal with initiation and transformation, with going into the forest where one's deepest fears and most powerful dreams are realized. Many of them offer a map for getting through to the other side."

In the universe of fairy tales, the Just often find a way to prevail, the Wicked generally receive their comeuppance -- but there's more to such tales than a formula of abuse and retribution. The trials these wounded young heroes encounter illustrate the process of transformation: from youth to adulthood, from victim to hero, from a maimed state to wholeness, from passivity to action. Fairy tales are, as Ellen says, maps through the woods, trails of stones to mark the path, marks carved into trees to let us know that other women and men have been this way before.

Though they warn us to steer clear of gingerbread houses and huts that stalk the woods on chicken's feet, they also show the way to true shelter, sanctuary, and places of healing deep in the forest. (The real lesson here, it seems to me, is to learn to tell the difference.) Think of the hut in Brother and Sister" for example, where the siblings set up housekeeping in the woods, far from the everyday world (and their stepmother's malice), adapting to the rhythms of the forest, of self-sufficiency, and of the brother's enchantment. Or the woodland cabin in The White Deer, where the deer-princess sleeps safely each night. Or the cottage (or cave) where Snow White finds shelter with a band of rough forest-dwelling men (the metal-working dwarves of Teutonic folklore in some versions, outlaws and brigands in others). Even the Beast's lonely castle deep in the woods is more sanctuary than prison...a place where captor and prisoner both transform, in true fairy tale fashion.

These places are linked not only by their woodland settings, but by the temporary nature of the sanctuary provided. The curse is broken or the secret revealed, or the magical task finished, or the trial survived; transformation is complete, and the hero must now return to the human world. Traditionally, rite-of-passage ceremonies are designed to propel initiates into a sacred place and sacred state (the realm of the spirits, gods, or ancestors; the place of vision, instruction, and metamorphosis)...but then to bring them back again, back to the tribe or community and to ordinary life. We're meant to come out of sweatlodge, down from the Vision Quest hill, home from the Moon Hut, back from the sacred hunt, bringing with us new knowledge, new dreams, a new status, a new name or role to play....intended not just for the sake of personal growth but in service to the whole tribe or community. Likewise, we're not meant to remain in the circle of enchantment deep in the fairy tale forest -- we're meant to come back out again, bringing our hard-won knowledge and fortune with us...in service to the family (old or new), the realm, the community; to children and the future.

These places are linked not only by their woodland settings, but by the temporary nature of the sanctuary provided. The curse is broken or the secret revealed, or the magical task finished, or the trial survived; transformation is complete, and the hero must now return to the human world. Traditionally, rite-of-passage ceremonies are designed to propel initiates into a sacred place and sacred state (the realm of the spirits, gods, or ancestors; the place of vision, instruction, and metamorphosis)...but then to bring them back again, back to the tribe or community and to ordinary life. We're meant to come out of sweatlodge, down from the Vision Quest hill, home from the Moon Hut, back from the sacred hunt, bringing with us new knowledge, new dreams, a new status, a new name or role to play....intended not just for the sake of personal growth but in service to the whole tribe or community. Likewise, we're not meant to remain in the circle of enchantment deep in the fairy tale forest -- we're meant to come back out again, bringing our hard-won knowledge and fortune with us...in service to the family (old or new), the realm, the community; to children and the future.

Unless, that is, we stay in the woods and take on a different role in the story...not a hero this time, but one of the forest dwellers who aids (or hinders) another's journey: the woodwose, the hermit, the sage, the mad prophet...the men and woman who run with the wolves...the femme sauvage with her herbs and charms... the conjure man with his beehives and songs....

But those are stories for another day, and another journey into the woods.

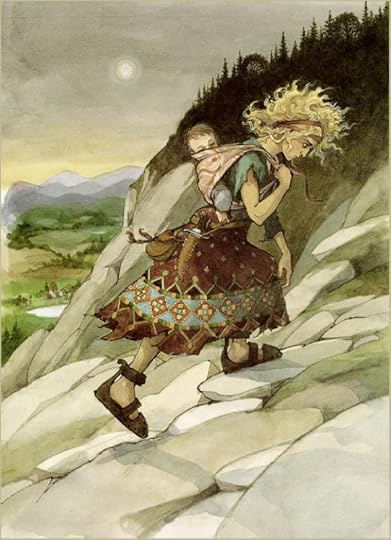

Pictures:

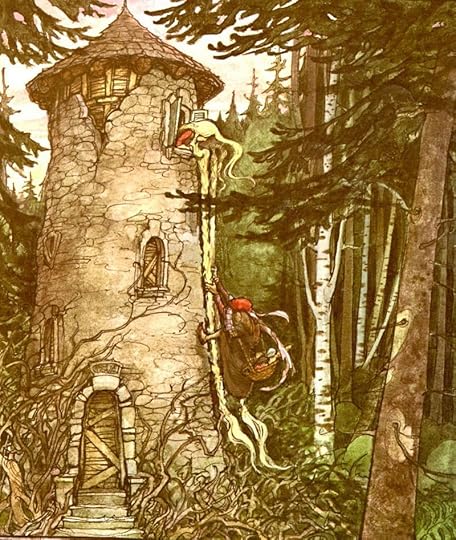

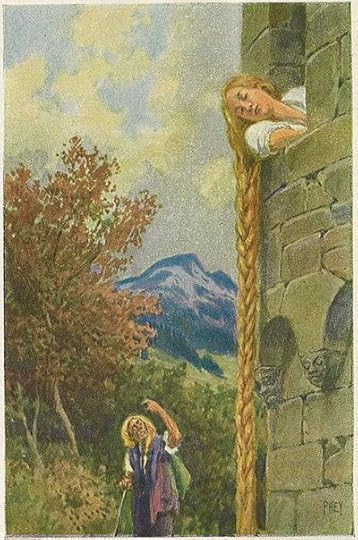

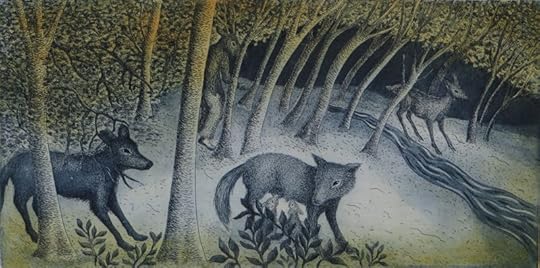

The paintings above are by Jeanie Tomanek, who lives and works in Georgia, near Atlanta.

"My all-time favorite folktale is 'The Handless Maiden," she says. "It is about a woman���s journey toward wisdom and self-realization and the obstacles and helpers she encounters. This tale encompasses many of the archetypical representations of women. My 'Everywomen' portray the mothers, daughters, lovers, and crones. Strong, wise women who will survive. These are filtered through my own experiences many times." All rights to imagery here are reserved by the artist. The drawing of Rapunzel's tower is by A.H. Watson.

Words: I am grateful to Midori Snyder for allowing me to quote such a long passage from her Armless Maiden essay. I urge anyone interested in the tale to please read this insightful essay in full. All right to text above, included quoted passages, are reserved by the authors.

June 4, 2020

The Maiden in the Tower

After two-and-half months of coronavirus lockdown, I've been thinking about fairy tales of isolation: young women locked away in towers or high atop steep hills of glass; young men turned to swans or beasts and likewise banished from human society. Rapunzel, isolated in her lonely tower, is one of the best known of such stories, and so I'd like to take a closer look at its history....

The version of Rapunzel we know today was published as a German folk tale by the Brothers Grimm in 1857 -- but it's now believed that their Rapunzel was neither German nor a proper folk tale. Scholars have shown that a number of the storytellers from whom the Brothers Grimm obtained their material were recounting "authored" tales from German, French, and Italian literary sources rather than anonymous folk stories passed orally from teller to teller. The Grimms' Rapunzel, for example, was derived from a story of the same name published by Friedrich Schultz in 1790 -- which was a loose translation of an earlier French story, Persinette by Charlotte-Rose de La Force, published in 1698 at the height of the "adult fairy tale" literary movement in Paris. La Force's tale was influenced by an even earlier Italian story, Petrosinella by Giambattista Basile, published in 1634 in his story collection Lo cunto de li cunti (also known as the Pentamerone).

Each writer in this chain used folk motifs drawn from oral tales (associated with peasants and the countryside), reworking them into literary tales (for adult readers who were educated, urban, and upper-class). It is difficult, however, to draw a sharp line between folk tales and literary fairy tales, placing Rapunzel in one category or another -- for after the Basile, La Force, and Schultz publications, Rapunzel slipped into the oral tradition of storytellers throughout the West, where it's now part of our folk culture even though it didn't start there.

Each writer in this chain used folk motifs drawn from oral tales (associated with peasants and the countryside), reworking them into literary tales (for adult readers who were educated, urban, and upper-class). It is difficult, however, to draw a sharp line between folk tales and literary fairy tales, placing Rapunzel in one category or another -- for after the Basile, La Force, and Schultz publications, Rapunzel slipped into the oral tradition of storytellers throughout the West, where it's now part of our folk culture even though it didn't start there.

Let's go back to the start, however, with Giambattista Basile's Petrosinella. Basile, born near Naples, drew plots and characters from the folk tales of the region, re���working them into courtly tales for the Italian aristocracy. What follows is a bare-bones summary of his story, without the clever turns of language that make Basile's work so sprightly and distinctive. (I suggest reading Basile's story in full in a good English translation -- such as the one provided by Jack Zipes in his fine book The Great Fairy Tale Tradition.)

Once upon a time, the tale begins, a woman looked out her window at the garden of her neighbor, an ogress, and developed a terrible hunger for the fine parsley growing there. Now, this woman was pregnant, and it was widely believed that denying the cravings of a pregnant woman could cause grave harm to mother and child -- so she snuck into her neighbor's garden, not once, but over and over. The ogress laid a trap and caught her. "What do you have to say for yourself, thief?"

The woman threw herself on her neighbor's mercy, but the ogress was not appeased. "I will spare your life only if you give me the child you carry, be it boy or girl." The frightened woman agreed and slunk back home, pockets full of parsley.

She soon gave birth to a beautiful baby girl and named her Petrosinella (derived from the word for parsley in the Neapolitan dialect). By the time the child was seven years old, her mother had forgotten all about her promise. But when Petrosinella started school, her path took her by the ogress's house.

Each time that Petrosinella passed, the old ogress called out to her: "Tell your mother to remember the promise she made to me, Petrosinella!" The child did as she was told. Her mother grew more and more frightened, until one day she cried out: "Tell that woman my answer is: 'Take her!'"

Each time that Petrosinella passed, the old ogress called out to her: "Tell your mother to remember the promise she made to me, Petrosinella!" The child did as she was told. Her mother grew more and more frightened, until one day she cried out: "Tell that woman my answer is: 'Take her!'"

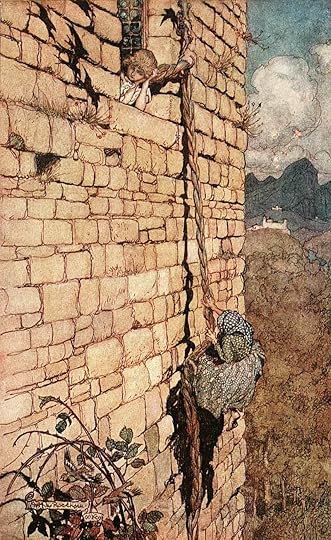

When Petrosinella delivered this message, the ogress grabbed her by the hair, carried her deep into the forest, and locked her in a tall stone tower. The tower had no door or stairs, just a small window at the very top, and there the child would sit, straining to catch a small ray of sun. The girl grew up in this lonely place. The ogress was her only company, climbing in and out of the tower on the long, gold braids of Petrosinella's hair.

Years passed, and Petrosinella grew into a beautiful young woman, her golden braids so long they coiled on the ground below. It happened that a prince, who was hunting nearby, became separated from his fellows. He stumbled through the forest, lost, and came upon the tower. The ogress was away and Petrosinella sat in the window sunning her hair. She was the most beautiful young woman the prince had ever seen, and he instantly fell in love. He called up to Petrosinella, and for several days they conversed and sighed and pledged their love. Then Petrosinella proposed a plan to meet when the moon had risen. That night, she gave the old ogress a dose of poppy to make her sleep, then she threw her braids over the windowsill and pulled the young man up. The prince then "made a little meal out of the parsley sauce of love."

[image error]More nights of love-making followed until an old gossip got wind of this. She told the ogress what was going on, warning her that her "daughter" might up and fly if she didn't act quickly. The ogress was unperturbed, saying: "She won't be able to get very far without the use of my magic acorns, and I've carefully hidden them in a little spot above the rafters."

Petrosinella had been listening at the window, and she quickly made a plan. She told her lover to bring some rope, then she drugged the ogress to sleep again, stole the three acorns, and used the rope to leave the tower. They hadn't gone very far when the ogress woke and discovered the girl's escape, using her magic to catch up to the fleeing lovers in no time. Petrosinella threw down the first acorn. It turned into a ferocious dog ��� but the ogress drew bread from her pocket and fed the dog so it let her pass. Petrosinella threw down the second acorn. It turned into a raging lion. The ogress stole the skin from a grazing ass and charged into the lion, which reared back from this monstrous apparition and fled in fright. Petrosinella threw down the third acorn. It turned into a hungry wolf, which quickly gobbled up the ogress before she could use her magic again to save herself.

Now the lovers were safe. They traveled on to the prince's own kingdom, where "with the kind permission of his father, the prince made Petrosinella his wife and proved that, after many trials and tribulations, one hour in a safe harbor can make you forget one hundred years of storm."

Sixty years after Basile's Petrosinella, the French writer Charlotte-Rose de La Force borrowed elements from it to use in her own Maiden-in-a-Tower story, Persinette, published in her fairy tale collection Les contes des contes in 1697. (This, of course, was a practice much more common in the days before copyright laws; particularly among writers of fairy tales, where the practice continues to this day.) La Force was part of a group of writers (including Madame D'Aulnoy, Madame de Murat, and Charles Perrault) who created a vogue for adult fairy stories in the literary salons of Paris. Like Basile, La Force was writing for an educated, aristocratic audience, creating stories that were meant both to entertain and to comment on issues of contemporary life.

Sixty years after Basile's Petrosinella, the French writer Charlotte-Rose de La Force borrowed elements from it to use in her own Maiden-in-a-Tower story, Persinette, published in her fairy tale collection Les contes des contes in 1697. (This, of course, was a practice much more common in the days before copyright laws; particularly among writers of fairy tales, where the practice continues to this day.) La Force was part of a group of writers (including Madame D'Aulnoy, Madame de Murat, and Charles Perrault) who created a vogue for adult fairy stories in the literary salons of Paris. Like Basile, La Force was writing for an educated, aristocratic audience, creating stories that were meant both to entertain and to comment on issues of contemporary life.

One issue of particular concern to women of the period was the common practice of arranged marriages, particularly among the upper classes. Women had no legal say in these arrangements, often conducted as business transactions between one aristocratic family and another. Daughters were used to cement alliances, to curry favor, and to settle debts. Sex was a husband's legal right, and there was no possibility of divorce. Young girls could find themselves married off to men many years their senior or of vile temper and habits; disobedient daughters could be shut away in convents or locked up in mad���houses. Little wonder, then, that French fairy tales are filled with girls handed over to various wicked creatures by cruel or feckless parents, or locked up in enchanted towers where only true love can save them.

La Force and other writers of the period championed the idea of consensual, companionate marriages ruled by love and civility. (Some also believed that Fate intended certain souls to be together.) The emphasis on love and romance in their stories can seem quaint and saccharine today, but such stories were progressive, even subversive, in the context of the time. La Force herself was an independently���minded woman from a noble family who caused several scandals in her quest to live a life that was self���determined. She fell in love and attempted to marry a young man without parental permission. When his family locked him up to prevent an elopement, she snuck into his room dressed as a bear with a traveling theater troupe! The couple escaped, and married -- but the law eventually caught up to them and the marriage was annulled. She then got caught publishing satirical works critical of King Louis XIV. La Force was exiled to a convent for this crime -- where she wrote her book of fairy tales and a series of popular historical novels. Eventually released, she spent the rest of her life earning her own living through her writing.

Like all of La Force's fairy tales, Persinette is a sensual, sparkling confection with a sly, sharp humor at its center. It's not hard to see why the tale of a girl locked away in a tower would have appealed to her.

Once upon a time, the tale begins, a young couple prepares for the birth of their child and all is well until the wife conceives a passionate craving for parsley. Her doting husband steals the parsley out of a fairy's enchanted garden. (The gate stands temptingly open, implying the fairy knows very well what will happen -- and may, indeed, have magically caused the craving that sets the tale in motion. Fairies are well known, after all, for their penchant for stealing infants.) The second time the husband sneaks into the garden (again he finds the gate open), the fairy catches him and demands his unborn child as payment. The man agrees "after a short deliberation." When his wife gives birth to a beautiful baby girl, she promptly hands the child over to the fairy without a word of protest.

The fairy raises the child tenderly until Persinette (as she's come to be called) reaches the age of puberty. Then, in order to keep the girl safe from harm (the eyes and attention of men), the fairy builds a magnificent silver tower deep in the forest. It contains all that the girl could desire: large and airy rooms elegantly furnished; wardrobes full of sumptuous clothes; delicious meals that are gracefully served by invisible fairy servants; books, paints, and instruments so Persinette need never be bored. What it doesn't have is a door or stairs, so whenever the fairy comes to call she says, "Persinette, let down your hair," and she climbs up through the window.

The fairy raises the child tenderly until Persinette (as she's come to be called) reaches the age of puberty. Then, in order to keep the girl safe from harm (the eyes and attention of men), the fairy builds a magnificent silver tower deep in the forest. It contains all that the girl could desire: large and airy rooms elegantly furnished; wardrobes full of sumptuous clothes; delicious meals that are gracefully served by invisible fairy servants; books, paints, and instruments so Persinette need never be bored. What it doesn't have is a door or stairs, so whenever the fairy comes to call she says, "Persinette, let down your hair," and she climbs up through the window.

Years pass, and one day the son of the king is hunting in the forest nearby. He hears the maiden singing and falls in love with her, sight unseen. He finds his way to the tower and spies a shadowy figure far above -- but when he calls to her, Persinette takes fright. It's been many years since she's seen a man, and the fairy has told her that some are monsters who can kill with a single look. The prince leaves discouraged, but he cannot forget the sound of that lonely, lovely voice. He makes inquiries in a nearby village and learns that the girl is a fairy's prisoner.

The prince returns, waits, and watches how the fairy goes in and out of the tower. The next day, when the fairy is gone, he stands and calls out in the fairy's voice: "Persinette, let down your hair." Her long gold hair comes tumbling down, he climbs, and steps into the tower. Persinette is frightened once again -- but she soon recovers her aplomb as the prince persuades her of his love. He proposes to marry her there and then, and she "consented without hardly knowing what she was doing. Even so," writes La Force archly, "she was able to complete the ceremony."

The prince returns, waits, and watches how the fairy goes in and out of the tower. The next day, when the fairy is gone, he stands and calls out in the fairy's voice: "Persinette, let down your hair." Her long gold hair comes tumbling down, he climbs, and steps into the tower. Persinette is frightened once again -- but she soon recovers her aplomb as the prince persuades her of his love. He proposes to marry her there and then, and she "consented without hardly knowing what she was doing. Even so," writes La Force archly, "she was able to complete the ceremony."

The prince continues to visit the tower, and before long Persinette grows fat. Innocent, she doesn't know she's pregnant -- but the fairy certainly does. Furious, the fairy takes up a knife and cuts off Persinette's long braids, then she sends her off in a flash of fairy magic to a remote place. The fairy hangs the braids from the tower window and waits for the prince to come. He clambers over the windowsill and is shocked to find his lover gone. The fairy angrily informs the prince he'll never see Persinette again, and she flings him from the tower. He lands in briar thorns, which blind him.

For several years the prince wanders the world, living on charity, till at last he reaches a remote place where he hears his wife singing. Persinette now has twin children, who instantly recognize the blind man as their father. Persinette cries with joy, and her tears magically restore his sight.

But wait! The fairy is still angry, and not yet prepared to leave them be. The food in the larder turns into stones, the well fills up with venomous snakes, the birds in the sky above turn into dragons breathing fire. The little family huddles together, preparing to die of the fairy's wrath -- but the lovers are happy, nonetheless, to have found each other at last. At this, the fairy's heart finally melts. She sees that their love is strong and true. She forgives them, blesses their marriage, and transports them to the king's castle, where the king and queen welcome their son and his family with open arms.

Friedrich Schultz's Rapunzel, published in Germany one hundred years later, faithfully follows La Force's plot while toning down the flowery language common to fairy tales of the earlier period. The only marked change Schultz makes to the story is that the fairy is portrayed with greater sympathy. Confronting Rapunzel's pregnancy, she's more Disappointed Mother than Vengeful Fury; and she doesn't throw the prince from the tower -- he leaps himself, in a fit of despair. Overall, Schultz merely re-tells La Force's tale rather than spinning it into something new.

The oral version of "Rapunzel" collected by the Grimms half a century after the Schultz publication follows the Schultz and La Force plot and is clearly derived from one or both. But the Grimms made several changes before they published their Rapunzel in 1857. Once again, the story begins with the overwhelming cravings of a pregnant woman. She craves rapunzel (a form of lettuce), which grows in the garden of a sorceress. (The Grimms often edited fairies out of their stories, for they considered the creatures to be too French. It was not until later English versions that the sorceress became a witch.) When she reaches the age of puberty, the girl is locked up in a tower by the woman she now calls Mother Gothel (a generic name for a godmother). The tower has no door or stairs, and the only way to enter it is to stand and deliver the famous line: "Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair."

The prince hears the maiden singing, finds the tower, and cannot get into it. He rides home again, but returns each day, compelled by the beauty of her song. When he sees the sorceress come and go, he learns at last how the tower is entered. "If that's the ladder one needs," he says, "I'm also going to try my luck."

He enters the tower, calms the frightened princess, and declares his undying love for her. He offers her his hand in marriage, and Rapunzel chastely accepts. Thereafter, he visits Rapunzel each evening when Mother Gothel is safely away. Each time he comes, he brings a skein of silk so she can weave a ladder to escape.

He enters the tower, calms the frightened princess, and declares his undying love for her. He offers her his hand in marriage, and Rapunzel chastely accepts. Thereafter, he visits Rapunzel each evening when Mother Gothel is safely away. Each time he comes, he brings a skein of silk so she can weave a ladder to escape.

One day, as the sorceress climbs her hair, Rapunzel absentmindedly asks her why is she so much heavier than the prince? Mother Gothel guesses all and flies into a terrible rage. She cuts off Rapunzel's hair, banishes her to a distant wilderness, and waits for the prince to come that night, where she confronts him with his crimes. He leaps from the tower, is blinded by the thorns, and then wanders the world seeking Rapunzel -- who's now referred to as his "wife." They re-unite, his sight is restored, and he learns he has two children. He takes them home to his father's court, and no further mention is made of Mother Gothel.

Although the Grimms originally expected their folk tale collection to be of interest primarily to scholars, they soon realized they had a large and lucrative readership among children and their parents. With each subsequent edition, they edited the stories further to make them more appropriate for young readers, deleting sexual references and making heroines more virtuously moral. Thus, in their version of Rapunzel, they glide right over the conception of the twins, and over the fact of her pregnancy, until the children appear, without explanation, at the story's end. Because of the world-wide popularity of the Grimms' now-classic volume of tales, this children's version of Rapunzel is the one best known today.

As fairy tales continued to be pushed to the children's shelves in the 20th century, the Grimms' version of Rapunzel was re-told over and over in countless picture books -- sometimes edited further to delete the existence of those awkward twins altogether. In the public mind, Rapunzel's tale was one intended for very young readers -- with few realizing that at its root this is a story about puberty, sexual desire, and the evils of locking young women away from life and self���determination. In the children's version, Rapunzel is just another passive princess waiting for her prince to come. In the older tales we glimpse a different story: about a girl whose life is utterly controlled by greedy, selfish, capricious adults...until she disobeys, chooses her own fate, and bursts from captivity into adult life, symbolized by the birth of her own children in a distant land.

In the latter decades of the 20th century, Rapunzel's story began to change again as fairy tales began re-appearing in poetry and fiction for adult readers. This new literary fairy tale movement was pioneered by feminist writers such as Anne Sexton and Angela Carter, and by genre writers such as Robin McKinley, Jane Yolen, and Tanith Lee.

Kate Forysth's Bitter Greens is my favourite retelling of the tale. In this unusual novel, Forsyth moves from the painters and palazzos of Renaissance Venice to the "fairy tale salons" of 17th century France, braiding three stories into one while mixing historical and magical characters to great effect. (The use of the life story of Charlotte-Rose de la Force, one of the real French salonni��res, is utterly delicious.) Donna Jo Napoli's Zel, set in 16th century Switzerland, is also highly recommended. This dark, psychologically complex rendition is written in a chorus of three voices: a mother unhinged by the possessive nature of her love, a daughter scarred by imprisonment, and a young man obsessively in love with a girl he barely knows.

In her fine story "Touk's House," Robin McKinley uses elements from Rapunzel, but re-works the plot extensively. Here, a woodcutter's newborn daughter is the price he pays for stealing healing herbs. The witch is a sympathetic figure, raising the girl like her own daughter and teaching her the herb lore with which she'll eventually win the hand of a prince. But the girl doesn't want the prince in the end, choosing the witch's sweet son instead. Gregory Frost's "The Root of the Matter," by contrast, is a dark and very adult tale exploring the sexual tensions inherent in the story, and its consequences. Here Mother Gothel is a woman deeply damaged by a history of abuse, and she damages the child she has forcibly adopted in turn. The story is told from three points of view: Mother Gothel, Rapunzel, and the Prince -- the latter two undergoing true transformation by the story's end. Lisa Russ Spaar's story "Rapunzel's Exile" is brief but packs an emotional wallop. Spaar imagines Rapunzel's journey as her Godmother leads her into the forest, and her dawning horror as she realizes that the tower will be her fate. For twelve years her Godmother raised her kindly ��� but now, with the onset of menstruation (her skirts still bloody, her body still seeping), her Godmother has turned into a different creature, pushing her into the tower at knife point, and walling up the door with stones.

In her fine story "Touk's House," Robin McKinley uses elements from Rapunzel, but re-works the plot extensively. Here, a woodcutter's newborn daughter is the price he pays for stealing healing herbs. The witch is a sympathetic figure, raising the girl like her own daughter and teaching her the herb lore with which she'll eventually win the hand of a prince. But the girl doesn't want the prince in the end, choosing the witch's sweet son instead. Gregory Frost's "The Root of the Matter," by contrast, is a dark and very adult tale exploring the sexual tensions inherent in the story, and its consequences. Here Mother Gothel is a woman deeply damaged by a history of abuse, and she damages the child she has forcibly adopted in turn. The story is told from three points of view: Mother Gothel, Rapunzel, and the Prince -- the latter two undergoing true transformation by the story's end. Lisa Russ Spaar's story "Rapunzel's Exile" is brief but packs an emotional wallop. Spaar imagines Rapunzel's journey as her Godmother leads her into the forest, and her dawning horror as she realizes that the tower will be her fate. For twelve years her Godmother raised her kindly ��� but now, with the onset of menstruation (her skirts still bloody, her body still seeping), her Godmother has turned into a different creature, pushing her into the tower at knife point, and walling up the door with stones.

The heroine of Emma Donoghue's "The Tale of the Hair" has chosen to live in a crooked stone tower. She's blind, and she has come to fear the sounds of the forest around her. "Block up the windows and doors," she tells the wise-woman who is her guardian and companion. One night a prince hears her singing, climbs up the tower, and introduces her to love. But soon she learns that the unseen prince is not quite what she thought.... Elizabeth Lynn's delightful "The Princess in the Tower" is set in an obscure and remote village somewhere in the hills of Europe: a place with fabulous, fattening food, and where zaftig women are prized. Poor Margeritina is so slim that everyone thinks she's ill and hideous. She stays in the family house in shame, trying to no avail to put on weight -- until a young man stumbles into the village, hears her singing from her high window, falls in love and whisks her away to marry him and start a restaurant. The charm of the story lies in Lynn's telling, and in the sumptuous food descriptions. Anne Bishop's "Rapunzel" is a moving tale that is broken into three distinct parts: the mother's story, the witch's story, and finally Rapunzel's story. The first two parts are contrasting narratives of jealousy and greed; the third follows Rapunzel to the wilderness, where she finds new life beyond the tower.

Contemporary poets have also looked at the tale through the eyes of its different characters, finding in the story's themes issues relevant to our lives today.

Carolyn Williams-Noren gives voice to the least sympathetic character in the story in "Rapunzel's Mother":

I can't explain why I wanted that simple

thing so much: dark green rampion leaves, the curled

coverlets of them stacked together on the sideboard,

the rainy steam of them cooking, the hot full softness

and the bittersweet bite in my throat, mouthful

after mouthful. It was as if there was no other way to keep alive.

Nicole Cooley reflects on a troubled mother���daughter relationship in her poem "Rampion":

Tiny blue flowers furred with dirt are all the woman desires

in the story my mother reads over and over. Once upon a time

a woman longed for a child, but see how one desire easily

replaces the next, see her husband climbing the tall garden wall

with a handful of rampion, flowering scab she's traded for a child.

Look, my mother says, see

how the mother disappears

as rampion's metallic root splits the tongue like a knife

and the daughter spends the rest of the story alone.

Dorothy Hewett's chilling poem "Grave Fairy Tale" looks at the witch, through Rapunzel's eyes:

She was there when I woke, blocking the light,

or in the night, humming, trying on my clothes.

I grew accustomed to her; she was as much a part of me

as my own self; sometimes I thought, "She is myself!"

a posturing blackness, savage as a cuckoo. . . .

Both Anne Sexton and Olga Broumas cast the relationship between Rapunzel and Mother Gothel as a sexual one. In Sexton's "Rapunzel," she writes of a lesbian affair between a student and her mentor, which the younger woman ends when a "prince" offers her a more socially acceptable life:

As for Mother Gothel,

her heart shrank to the size of a pin,

never again to say: Hold me, my young dear,

hold me,

and only as she dreamt of the yellow hair

did moonlight sift into her mouth.

Broumas, by contrast, celebrates such relationships in her answering poem "Rapunzel," writing in the voice of a younger woman who has no such temptation to stray:

Climb

through my hair, climb in

to me, love / hovers here like a mother's wish.

...How many women

have yearned

for our lush perennial, found

themselves pregnant, and had

to subdue their heat, drown out their appetite

with pickles and hard weeds.

David Trinidad's "Rapunzel" grows desperate in her isolation:

Like hair, the days and nights are growing longer and longer.

...And each evening the crone comes. Her crackled fingers appear

pinching the key....

If only once she'd say: "Here,

take this pair of scissors and cut your hair before it twists

into spaces between the bricks like vines." I'd slit my wrists.

In Liz Lochhead's "Three Twists," on the other hand, Rapunzel discovers there are worse things than solitude ��� like a prince who hasn't got a clue about what she really needs:

& just when our maiden had got

good & used to her isolation

stopped daily expecting to be rescued,

had come almost to love her tower,

along comes This Prince / with absolutely all the wrong answers

The prince in Sara Henderson Hay's "Rapunzel" is all too skilled at the language of love:

Oh God, let me forget the things he said.

Let me not lie another night awake

Repeating all the promises he made....

I knew I was not the first to twist

Her heartstrings to a rope for him to climb.

I might have known I would not be the last.

Alice Friman's poem "Rapunzel" displays a bit more sympathy for the prince:

If she was unwise about such things

that girls are taught of men

with chocolate kisses / who offer lifts to lessons

who stand too close in subways

playing with their change

then what was he?

Caught in that small room,

the braid

coiling the floorboards like a snake,

and she all Rubens���ripe and curious.

Oh, the tower���singing on the wheezy couch.

Forbidden fruits in platters of her flesh

and he with scars to touch along his side

and many wondrous things to name.

Bruce Bennett's "The Skeptical Prince" wants proof that there's really a maiden in that tower:

The town has grown accustomed to the sight:

he drinks by day, then hangs around at night,

purveying sad and antiquated lore,

insisting he will act once he is sure

Essex Hemphill's "Song of Rapunzel" reminds us that sometimes men need rescuing too:

His hair

almost touches

his shoulders.

He dreams

of long braids,

ladders,

vines of hair.

He stands

like Rapunzel,

waiting on his balcony

to be rescued

from the fire���breathing

dragons of loneliness.

Rosemary Dun's "Rapunzel" rescues herself from prince and tower alike:

. . .I cut off the long hank of my

just���for���him hair with golden shears,

so that / no more would he climb,

prick my finger,

nor ravish me awake.

Instead, my howls which once

had filled my madwoman's attic

with despair.

announce the birth of my

daughter.

We hold hands and jump.

Lisa Russ Spaar's "Rapunzel Shorn" is a young woman tasting sweet freedom at last:

I'm redeemed, head light

as seed mote, as a fasting

girl's among these thorns, lips

and fingers bloody with fruit.

Years I dreamed of this:

the green, laughing arms

of old trees extended over me,

my shadow lost among theirs.

Gwen Strauss' "The Prince" is an old man now, living with his beloved wife and looking back over the events of his life:

For a long time I was blind,

even before the thorns tattered my eyes.

I was bored, handsome, a Prince.

The thrill was in what I could get away with.

. . .All my childhood I heard about love

but I thought only witches could grow it

in gardens behind walls too high to climb.

Rapunzel's story has become part of our folk tradition because its themes are universal and timeless. We've all hungered for things with too high a price, we've all felt imprisoned by life at times; we've all been carried away by love, only to end up broken and alone; we all hope for grace at the end of our suffering and a happy ending.

In the end, the story tells us, we have to leave the tower one way or another, weave a ladder or leap into the thorns. We can't stay in childhood forever. The adult world, with all its terrors and wonders, waits for us just beyond the forest.

Words: All rights to the quoted text reserved by the various authors, and to the rest of the text reserved by me. The essay above is one of three about orphaned, abandoned, or stolen children, the others two being "From Remus & Romulus to Harry Potter: The Orphaned Hero" and "The Stolen Child: Tales of Fairy Changelings." For further reading on the subject of Rapunzel, I recommend Kate Forsyth's excellent The Rebirth of Rapunzel: A Mythic Biography of the Maiden in the Tower (FableCroft Publishing, 2016).

Pictures: Credits for the Rapunzel illustrations above can be found in the picture captions. (Hold your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights reserved by the artists.

June 3, 2020

There is no time for despair

It seems like a good time to post this piece again, although I dearly wish it wasn't....

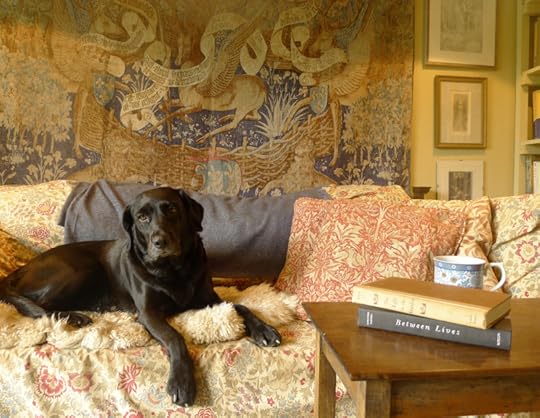

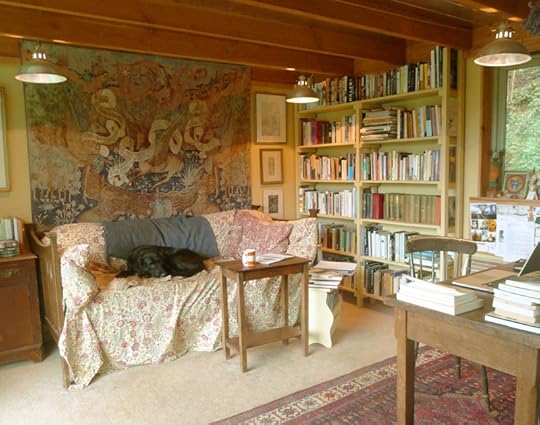

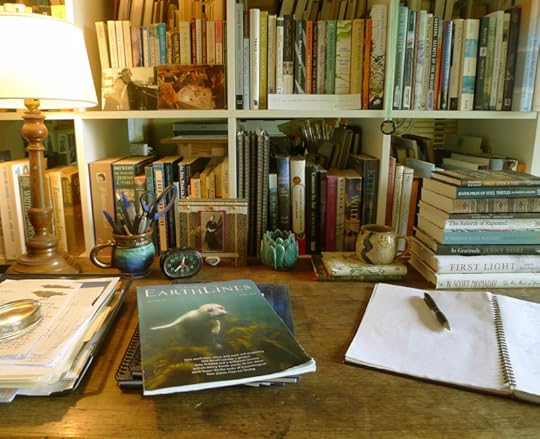

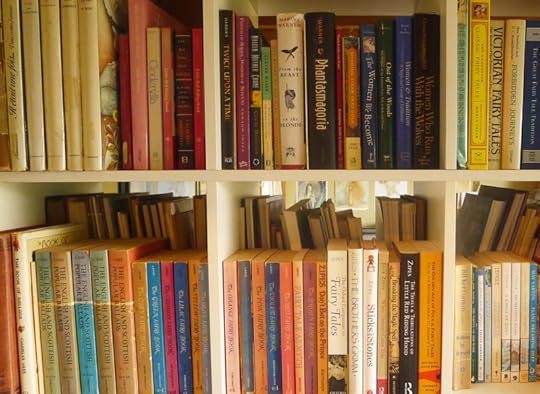

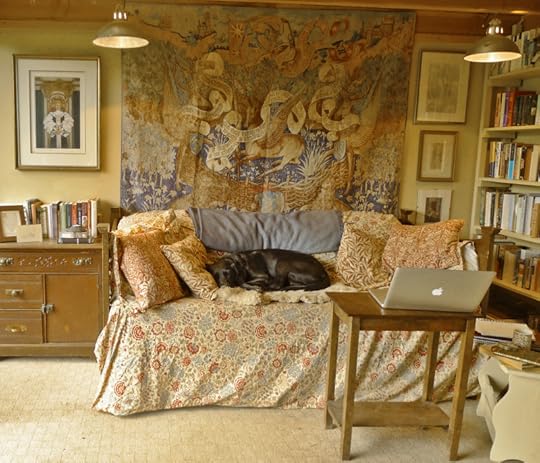

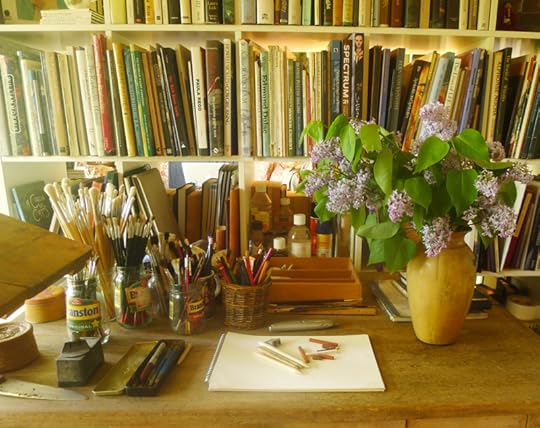

When the clamour of the world (and the Internet) grows harsh and cacophonous, I find it healing, grounding, and necessary to turn away from keyboards and screens, to ration the time I spend online, and to be fully present in the tactile world: in the morning light sifting through the studio, in the rising of the wind through the trees behind, in the words slowly forming in ink on fresh white paper spread out on my wooden desktop.

Instead of flicking through Web pages, imbibing the Internet's manic energy and then coming offline feeling fractured and spent, I pull books from down the shelves and turn their rustling pages at a measured, more human pace...and my soul unclenches. My attention deepens. Something vital in me is quickened back to life. And yes, I am using a keyboard now to share these thoughts with you online, but it's not a full rejection of modern technology I'm after. It's proportion and balance.

Instead of flicking through Web pages, imbibing the Internet's manic energy and then coming offline feeling fractured and spent, I pull books from down the shelves and turn their rustling pages at a measured, more human pace...and my soul unclenches. My attention deepens. Something vital in me is quickened back to life. And yes, I am using a keyboard now to share these thoughts with you online, but it's not a full rejection of modern technology I'm after. It's proportion and balance.

The Internet is a useful communication platform, and an increasingly important one...but books, oh, books are more than paper and ink. They are powerful medicine. Real books, I mean. Physical books, sitting on the dusty shelves of my studio and surrounding me like old friends, dog-earred and battered with love and use, their pages thick with margin notes and underlines. How could I ever doubt that art matters? Words have saved me over and over. Words are saving me right now. Books are what I turn to when the world grows dark, and they never fail to give me strength.

This morning, for instance, Ben Okri asks me:

"What hope is there for individual reality or authenticity, when the forces of violence and orthodoxy, the earthly powers of guns and bombs and manipulated public opinion make it impossible for us to be authentic and fulfilled human beings?"

I've been asking myself the same question all week.

"The only hope," he answers, "is in the creation of alternative values, alternative realities. The only hope is in daring to redream one's place in the world -- a beautiful act of imagination, and a sustained act of self becoming. Which is to say that in some way or another we breach and confound the accepted frontiers of things."

Then Rebecca Solnit joins the conversation:

"Cause-and-effect assumes history marches forward," she notes, "but history is not an army. It's a crab scuttling sideways, a drip of soft water wearing away stone, an earthquake breaking centuries of tension. Sometimes one person inspires a movement, or her words do decades later, sometimes a few passionate people change the world; sometimes they start a mass movement and millions do; sometimes those millions are stirred by the same outrage or the same ideal, and change comes upon us like a change of weather. All that these transformations have in common is that they begin in the imagination, in hope."

"To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic," adds Howard Zinn. "It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places -- and there are so many -- where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction."

Barry Lopez pulls me out of a Western-centric point of view, reminding me of the things I share in common with people the world over:

"I believe in all human societies there is a desire to love and be loved," he says, "to experience the full fierceness of human emotion, and to make a measure of the sacred part of one's life. Wherever I've traveled -- Kenya, Chile, Australia, Japan -- I've found the most dependable way to preserve these possibilities is to be reminded of them in stories. Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives. It is through story that we embrace the great breadth of memory, that we can distinguish what is true, and that we may glimpse, at least occasionally, how to live without despair in the midst of the horror that dogs and unhinges us."

Terry Tempest Williams concurs, and affirms the role that artists play in the transmission of such stories:

"Bearing witness to both the beauty and pain of our world is a task that I want to be part of. As writers, this is our work. By bearing witness, the story that is told can provide a healing ground. Through the art of language, the art of story, alchemy can occur. And if we choose to turn our backs, we've walked away from what it means to be human."

Then Toni Morrison takes me firmly by the shoulders and sends me back to my desk again:

Troubled times, she says, are "precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.

"I know the world is bruised and bleeding," she adds, "and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge -- even wisdom. Like art."

Like art indeed.

Words: The first five quotes above are from the following books, all recommended: A Way of Being Free by Ben Okri (Phoenix, 1998); Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit (Nation Books, 2005); You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train by Howard Zinn (Beacon Press 2002), About This Life by Barry Lopez (Vintage, 1999), and A Voice in the Wilderness: Conversations with Terry Tempest Williams, edited by Michael Austin (Utah State University Press, 2006). The final quote is from "No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear" by Toni Morrison (The Nation, March 2013); I owe thanks to Maria Popova of Brain Pickings for introducing me to it. Pictures: The drawing and painting above are by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). The photographs are from my studio cabin, perched on a Devon hillside at the edge of a small wood.

June 2, 2020

On Black Tuesday