Terri Windling's Blog, page 37

May 8, 2020

Time passing

Here in Chagford, one way to mark the passage of time is to watch the local pony herd, coming down from the moor each year to birth their foals on the village Commons.

The first of the foals was born just after the Corvid-19 lock-down began. There are nine foals now (the last time I counted), some of them still clinging to their mamas, others big and bold enough to prance across the grass together in play. My heart lifts every time I see them. There is too much death and grief right now, yet there is also new life everywhere I look: foals, lambs, fledgling birds, a litter of puppies down our road, and a baby girl born to good friends. The Great Wheel continues to turn, nothing stays still, everything is change.

In his beautiful letter to the generations of the future, Scott Russell Sanders writes:

"When I think of all the wild pleasures I wish for you, the list grows long. I want you to be able to chase fireflies as they glimmer in long grass, watch tadpoles turn into frogs in muddy pools, hear loons calling on clear lakes, glimpse deer grazing and foxes ambling, lay your fingers in the paw prints of grizzlies and wolves. I want there to be rivers you can raft down without running into dams, the water pure and filled with the colors of sky. I want you to thrill in spring and fall to the ringing calls of geese and cranes as they fly overhead. I want you to see herds of caribou following the seasons to green pastures, turtles clambering onshore to lay their eggs, alewives and salmon fighting their way upstream to spawn. And I want you to feel in these movements Earth���s great age and distances, and to sense how the whole planet is bound together by a web of breath.

"As I sit here in this shaggy yard writing to you, I remember a favorite spot from the woods behind my childhood house in Ohio, a meadow encircled by trees and filled with long grass that turned the color of bright pennies in the fall. I loved to lie there and watch the clouds, as I���m watching the high, surly storm clouds rolling over me now. I want you to be able to lie in the grass without worrying that the kiss of the sun will poison your skin. I want you to be able to drink water from faucets and creeks, to eat fruits and vegetables straight from the soil. I want you to be safe from lightning and loneliness, from accidents and disease. I would spare you all harm if I could. But I also want you to know there are powers much older and grander than our own -- earthquakes, volcanoes, tornados, thunderstorms, glaciers, floods. I pray that you will never be hurt by any of these powers, but I also pray that you will never forget them. And remember that nature is a lot bigger than our planet: it���s the shaping energy that drives the whole universe, the wheeling galaxies as well as water striders, the shimmering pulsars as well as your beating heart.

"Thoughts of you make me reflect soberly on how I lead my life. When I spend money, when I turn the key in my car, when I vote or refrain from voting, when I fill my head or belly with whatever���s for sale, when I teach students or write books, ripples from my actions spread into the future, and sooner or later they will reach you. So I bear you in mind. I try to imagine what sort of world you will inherit. And when I forget, when I serve only my own appetite, more often than not I do something wasteful. By using up more than I need -- of gas, food, wood, electricity, space -- I add to the flames that are burning up the blessings I wish to preserve for you....

"If Earth remains a blessed place in the coming century, you���ll hear crickets and locusts chirring away on summer nights. You���ll hear owls hoot and whippoorwills lament. You���ll smell wet rock, lilacs, new-mown hay, peppermint, lemon balm, split cedar, piles of autumn leaves....If we take good care in our lifetime, you���ll be able to sit by the sea and watch the waves roll in, knowing that a seal or an otter may poke a sleek brown head out of the water and gaze back at you. The skies will be clear and dark enough for you to see the moon waxing and waning, the constellations gliding overhead, the Milky Way arching from horizon to horizon. The breeze will be sweet in your lungs and the rain will be innocent....

"Thinking about you draws my heart into the future. I want you to look back on those of us who lived at the beginning of the 21st century and know that we bore you in mind, we cared for you, and we cared for our fellow tribes -- those cloaked in feathers or scales or chitin or fur, those covered in leaves and bark. One day it will be your turn to bear in mind the coming children, your turn to care for all the living tribes. The list of wild marvels I would save for you is endless. I want you to feel wonder and gratitude for the glories of Earth. I hope you���ll come to feel, as I do, that we���re already in paradise, right here and now."

Words: The passage by Scott Russell Sanders above is from "We Bear You in Mind," first published in Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril (Trinity University Press, 2012), and reprinted in Orion Magazine. The poem in the picture captions, "Another Spring" by Denise Levertov (1923-1997), first appeared in Poetry Magazine, October/November, 1952. All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Our local pony herd and some of their foals, spring 2020. For more information on Dartmoor's beloved ponies, go here.

The "wild time" of the sickbed

Following on from yesterday, here's another post on the flexible nature of time from the Myth & Moor archives....

As those who also have medical issues can concur, it's not just the large, dramatic things (surgery, chemo, and the like) that disrupt our schedules and overturn our plans, it's often the small things too: the side-effects of a medication, for example; or the body's shock after an invasive test; or a simple virus making the rounds, knocking others out for a couple of days while knocking us out for a couple of months. Illness takes time, and time for artists is a crucial resource. Writing, editing, or illustrating a book, for example, takes hours and hours of focused attention; and whenever we are knocked from the ladder of health, it feels like our time has been stolen.

Yet the loss is not really of time itself, but of one particular form of it: the "productive" time prized in our commerical culture, which priviliges results and finished products over process. "Time is money," as the old saying goes, and a sick person's time is not worth a bad penny. Yet paradoxically, when we're in poor health we are often rich in time, but in the wrong kind of time: the "unproductive" time of the sickbed. After a lifetime lived in the liminal space between disability and good health, I have come to believe "unproductive" time has its place and its value as well.

The business world operates on a linear concept time, structured in regular working hours, measured by schedules, spreadsheets, targets; products made, marketed, and sold. Art-making is not a linear process, but those of us who work in the arts professions do our damn best to pretend that it is: writing books to deadline, making film or theatre to schedule, etc., while walking a precarious tightrope stretched between the muse and the marketplace. It's not an easy balance, but we do it. We live in a market culture, after all, and daily life jogs along by its rules. But illness cares nothing for markets; we do not heal in a linear fashion; and the common symptoms of failing health (the brain-fog, fatigue, and fevers of a body engaged with repairing itself) are at odds with the fast and furious pace of an industrialized, digitalized world.

Time, during an illness, slows and meanders: we sleep and wake, sink and rise, drift through the days absorbed in the mysteries of the body -- its fluids and fevers, its terrors and comforts, its cycles of pain and merciful release -- while our colleagues rush past in a bright busy world that seems far removed and unreal.

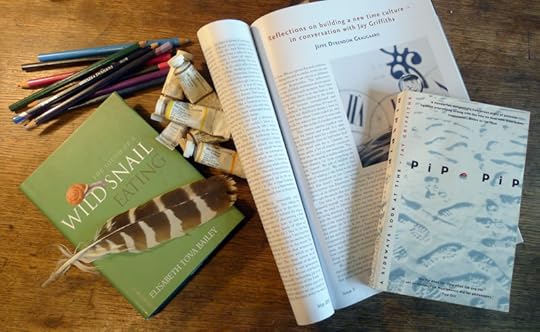

In her poetic memoir of illness, The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating, Elizabeth Tova Bailey reflects on the time she spent bedridden with a semi-paralysing auto-immune disease:

"The mountain of things I felt I needed to do reached the moon, yet there was little I could do about anything and time continued to drag me along its path. We are all hostages of time. We each have the same number of minutes and hours to live within a day, yet to me it didn't feel equally doled out. My illness brought me such an abundance of time that time was nearly all I had. My friends had so little time that I often wished I could give them what I could not use. It was perplexing how in losing health I had gained something so coveted but to so little purpose."

I sympathize with Bailey's despair about the "mountain of things" she suddenly could not do, (I've often felt the same), but I resist defining the slowed-down time of the sickbed as time that has no use. There are many modes of experiencing the world, and linear time is just one of them. During illness, I enter a different mode: slower, stranger, cyclical, tidal. Attuned to the immediate environment. I see it as a form of Wild Time, a term coin by cultural historian Jay Griffiths (in her excellent book on time, Pip Pip) -- defined as time that's not been dictated by modern industrial cultural norms; time rooted in the body, the land, the ebb and flow of sea and psyche.

It is always hard to remember the exact qualities of time experienced in the sickbed when we're back in the flow of the linear world; it blurs around the edges, bright and elusive as a fever dream. What I recall best about the strange Otherworld I enter whenever my body fails is how the world shrinks to the size of my bedroom, to the dimensions of a bed littered with books, and to a window view of the garden, the hill, and the oaks at the woodland's edge. Unable to summon the focused attention required to write, paint, or simply communicate, I surrender to those things that illness allows and facilitates: Reading, deeply and widely. Watching the natural world through window glass. Thinking the kind of thoughts that rise, for me, only in stillness and isolation.

Illness prevents me from being active. From climbing the hill up to my studio and re-engaging with the work I've left undone. But the art that I make in "productive" time is informed by the things I feel (and watch, hear, read, reflect on) during the slow, strange hours of fever and pain. Both aspects of life -- the busy studio, the quiet sickbed -- combine to make me the artist that I am.

Writing in EarthLines magazine in 2013, Deppe Dyrendom Graugaard described a conversation with musician and philosopher Morten Svenstrup about time in relation to nature and art -- reflecting on the way that time slows down when we are fully engaged in listening to music, looking at a painting, reading a book ... or, I'd add, communing with the body during the slow sensory days of an illness.

"Around the time this conversation took off, Morten was writing his thesis Time, Art, and Society, in which he explores the insight that when we engage with an artwork, we pay attention in a way we don't always do with other objects. The composition of an art piece, its inherent timing, cannot be forced to fit whatever our personal sense of time may be. Being a cellist, he was very aware that if we want to really engage with music, we have to surrender our immediate sense of time and listen. The question arose: what happens if we take the kind of attention we bring to bear on a painting, a symphony, or a poem into our everyday surroundings and listen to the inherent time of our neighbourhood, a nearby woodland, or our own bodies?

"Doing this, we encounter an astonishing diversity of timescales which make a mockery of the idea that there is such a thing as a singular, universal, abstract Time. The present is made up of a multiplicity of lifetimes, and getting past our personal view and tuning into what can best be described as a symphonic view of time, we immediately acquire the sense of the richness of life. By sidestepping our notion of time as something outside ourselves and independent of us, we see that everything has its own time, an Eigenzeit. This can work as an antidote to the speed that marks a society driven by principles of efficiency and growth. It is a practice which begins with noticing the world around us, paying attention and becoming present -- but which leads to a deeper understanding and connection with the places we inhabit."

Graugaard notes that an unrushed relationship with time is valuable in a digital age which constantly fractures our powers of concentration, and explains why cultivating Wild Time is a radical act.

"Wresting our attention from the flurry of information that is hurtled at us through fibre-optic communication and turning it toward the depth of time is not just about engaging new ways of seeing and honing the lifeskills we need to live fully in the context of a digitalized world. It is also a way of finding joy in the places we live in, whether they are urban or rural. Surrendering and accepting what is, and figuring out what we want to hold onto and what we can let go of. Without attention we are lost. Whatever distracts attention kills our potential to be free.

"This is why resisting the progressive notion of time as linear, singular, and above all placeless is profoundly political. It is about power. Tuning into the timescapes of the other allows us to dissolve the separation that modern life requires from us. That is what is meant by the beautiful metaphor of 'thinking like a mountain.' By thinking like a mountain, we open the possibility of becoming other."

There are many ways we can "think like a mountain" and pull ourselves from the frantic pace of the mechanized world into periods of soul-enriching (perhaps even soul-saving) Wild Time. We can take breaks from the Internet, for example; or immerse ourselves in nature; or cultivate "deep attention" by making art and engaging with art. And although it's not a method most of us would choose, illness, too, allows us to surrender to time in a slower, wilder way, thereby fostering a deeper, richer connection to the physical world we live in.

Don't get me wrong, I prefer good health. I prefer to be energetic and active. But during those times when I'm back in bed again, too weak, too tired, too pain-raddled to keep up with the friends and colleagues racing ahead on time's straight track, I am learning to accept that mine's a slower, more meandering trail. But it has its value. It has its use. It will get me where I want to go.

About the art:

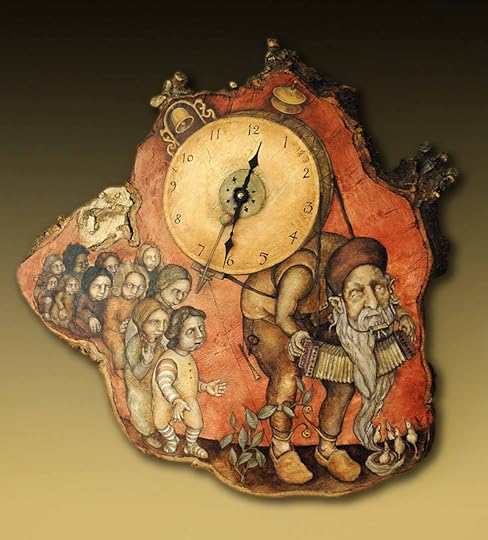

The wonderful painted clocks in this post are by my friend and Dartmoor neighbour Rima Staines, a multi-disciplinary artist who uses paint, wood, word, music, animation, puppetry, and story to "build a gate through the hedge that grows along the boundary between this world and that." Born in London to a family of artists, and raised on the roads of Bavaria in her early years, Rima has always been stubborn about living the things that make her heart sing.

With her partner Tom Hirons, Rima also runs the Hedgespoken folk arts project. For part of the year, they travel the lanes and byways of Britain in a glorious old truck converted into an off-grid venue for storytelling, folk theatre, and puppetry. In the winter months, they return to us on Dartmoor and focus on writing, painting, and running Hedgespoken Press.

Rima���s inspirations include the world and language of folk tales, folk music, folk art of Old Europe and beyond, peasant and nomadic living, wilderness, plant-lore, magics of every feather, and the beauty to be found in otherness. To see more of her extraordinary work, visit her website: Paintings in a Minor Key, her blog: The Hermitage, and seek out her book, Tatterdemalion, co-created with Sylvia V. Linsteadt.

The clock paintings above are by Rima Staines (the charming titles are in the picture captions - run your cursor over the pictures to read them); and all rights are reserved by artist. The drawing of Alice's White Rabbit checking his pocket watch ("Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be too late!") is by John Tenniel (1820-1940).

The passages quoted above are from The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elizabeth Tova Bailey (Algonquin Books, 2010), and Deppe Dyrendom Graugaard's introduction to an interview with Jay Griffiths (EarthLines magazine, 2013). I highly recommend Jay Griffith's book Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time (Flamingo, 1999). All rights reserved by the authors.

May 7, 2020

Once upon a time

The calendar turns, the lock-down rolls on, and time is going funny on us. It feels like we've been in lock-down forever; and it also feels like it hasn't been long at all, surely not six weeks since the UK lock-down began on March 23rd.

I've been thinking about the way time warps in so many fairy stories and myths. When we enter a story, and enter enchantment, we are in a place of profound uncertainty where even the steady ticking of the clock is something we cannot take for granted. Jay Griffiths wrote about this, I recalled, in her engrossing book Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time; so I pulled my copy down off the shelves and flipped through its pages until I found the following passage:

"Myth and stories across the world have a profound relationship to time. They enchant time, they represent its ambiguity and enigma. As western folktales begin Once Upon a Time, so Aboriginal Australian myths begin with a nod at time, thus: 'In the Dreamtime, when the earth was young....' 'In the time when the dreaming began, a time when there was neither birth nor death', or 'In the earliest days when time began'. Among the Iraqw of Tanzania, there are many 'once upon a time' openings for stories, often beginning bal geeza which literally means 'first days'. In Navajo myth and ritual, past, present, and future are interchangeable. The Achuar, a tribe of the Jivaro peoples in Ecuador, start their myths thus: 'A long time ago, a long, long time ago...', and tell their stories in the imperfect rather than in the cut-off perfect tense, ending the story in 'now'. Again, there is no absolute and simple break between now and then. There is a blurred border like a frayed cloud, not a separation of time but the difference of two modalities.

"Storyteller Michael Meade begins an Irish myth thus: 'Once upon a time, or below a time, or not, there was in Ireland a king named Conn Mor....' Another begins: 'There are five directions. East, where the sun rises. North, where there is trouble. South, where you may find a friend. West, where all that begins, ends. And the fifth direction; the place where stories come from and where they say Once Upon a Time....'

"Mythic stories talk time out of mind, charm and trick time, clogging or stretching it: fables make time fabulously paradoxical, a stubborn blot on the face of clock-time but true to the time of the psyche, where past, present and future are kaleidoscoped. Time can run anti-clockwise so the youngest child succeeds where the oldest fails, the dawn can be wiser than the dusk and birds can tell the future. Certain periods of time -- three days, a year and a day, seven years and a hundred years -- are enchanted. In these archetypal tales all over the world, 'sensible' time disappears into a wrinkle; a person dips into a fairy hill or disappears for a night with dwarves, but on their return finds that, Rip Van Winklish, a hundred ordinary years have passed. The dwarfish figures which inhabit so many tales are themselves squashed time, at once close to children, but yet grumpy old men, close to the underground past, but able to offer clues to the future; compressed and animated, like cartoons of time. Spellbound by a story, time stops for a child.

"The Inuit tell tales which begin 'long ago, in the future,' which is a beautiful expression of mythic time playing trickster to linear, logical conceptions. But all fairy tales play with time, from 'Once upon a time' to 'lived happily ever after.' Once tells of a past eternal, but the eternity it refers to is also a charmed present, just at one remove from now. French folk tales can begin 'Il y a une fois,' meaning some time ago, while il y a actually means 'there is.' This is the eternal-present tense, an enchanted present-continuous, a time in the past that still exists. The present, 'now and ever after,' is the present continuing, life everlasting, and even though the individual action is narrated and complete -- 'that's all folks' -- yet life goes on, ever after, back in the now....

"Mythic stories face death, time's most ferociously fearful aspect, and charm the sting out of it for this reason: the individual tale ends, myths imply, so the individual life story must end in death, but the life of the species lives from ever-before to ever-after. The consolation of life's continuing is most explicit in this Aboriginal Dreamtime myth: 'And so death comes, but life always returns.' Their transcendence of death is achieved in part by the archetypal nature of the characters of myths and folk tales; the totemic Dreamtime figures, the Jack and Jill of folk tales, even the Everyman of Morality Plays. Further, the tales themselves become 'immortal,' living stories retold from generation to generation in an oral culture, from ceilidh to corroboree."

Jeanette Winterson notes that as Western clock-time and lives speed up, urged ever faster by the restless, relentless gods of productivity, profit, and technology, this speed seeps into our narrative arts; and she makes a plea for letting fiction, and life, unfold at a more natural pace.

"Nobody would would expect to play a piece of music at twice the speed of the score and be able to enjoy it. Yet, in literature this is happening all the time. The reader chooses the pace without taking the trouble to first pick up the rhythm. To get used to a writer's rhythm, to move with a writer's own beat, needs a little more time. It means looking at the opening pages carefully. It can be helpful to read them out loud. Much of the delight everyone gets from radio adaptations of the classics is a straightforward delight in pace. The actors read much more slowly than the eye passes, especially the eye habituated to scanning the daily papers and skipping through the magazines. It is just not possible to read literature quickly. Neither poetry nor poetic fiction will respond to being rushed....

"It seems so obvious, this question of pace, and yet it is not. Reviewers, who can never waste more than an hour with a book, are the most to blame. Journalism encourages haste; haste in the writer, haste in the reader, and haste is the enemy of art. Art, in its making and in its enjoying, demands long tracts of time. Books, like cats, do not wear watches.

"Over and above all the individual rhythms of music, pictures and words, is the rhythm of art itself."

This is something I find myself thinking about as time moves so very strangely during these surreal days of lock-down. There is much that I miss of the pre-pandemic world, but not its frantic pace. If and when the lock-down eases, I want a different relationship to time itself. I want to move with the rhythms of the natural world, which is to say: with my own best natural rhythms. I want to live in art time, story time.

I want to live my life in enchantment.

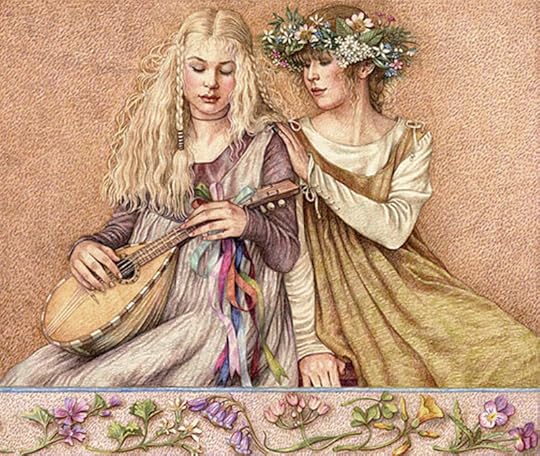

The imagery here today is by the award-winning Britist artist and illustrator Anne Yvonne Gilbert. Raised in Northumberland (in north-east England), Gilbert studied at Newcastle College and the Liverpool College of Art, and has worked as an illustrator and graphic artist since the late 1970s. She has published many beautiful children's books; provided cover art for fantasy classics by Diana Wynne Jones, Ursula K. Le Guin, Peter Dickinson, and John Crowley, among others; and designed everything from album covers to postage stamps -- working primarily with colored pencils and inks. Please visit her website and illustration blog to learn more.

Words: The passages by Jay Griffiths is from Pip Pip (HarperCollins, 1999); the passage by Jeanette Winterson is from Art Objects (Random House, 1995). All rights reserved by the authors and artist.

A note on punctuation: As an American living in the UK, I never know whether it's best to use standard American or British punctuation and spelling here (such as the difference in where periods are placed in relation to quotation marks). I quote a lot of passages from UK texts, yet I still work as an editor in the US publishing industry and am personally most comfortable with the American style. As a result (as long-time readers know), I go back and forth between the two in a highly confusing manner. Today, I've retained the British punctuation in the text quoted from Jay Griffiths' Pip Pip, as her style of writing is unique and I didn't want to mess with it.

May 6, 2020

The Bumblehill Studio Newsletter

We're very pleased to announce that the Bumblehill Studio now has a newsletter!

For those of you who have said you'd like a way to be alerted about new Myth & Moor posts, the letter will contain a round-up of each week's offerings, plus links to anything else I've published online and any events I'm participating in. There will also be a few reading recommendations, and occasional links to new works by other folks in the Bumblehill community.

Lunar Hine, my editorial assistant, will oversee the letter's production and send it out to subscribers once week. We promise to have mercy on your email Inbox and keep it short and sweet.

You can subscribe here (and easily unsubscribe any time you like).

The painting above is by Edmund Dulac. The drawing is by Arthur Rackham.

May 5, 2020

Moving forward like water

These words from Terry Tempest Williams' new book, Erosion, were written long before the global pandemic yet seem especially resonant right now:

"It is morning. I am mourning. And the river is before me. I am a writer without words who is struggling to find them. I am holding the balm of beauty, this river, this desert, so vulnerable, all of us. I am trying to shape my despair into some form of action, but for now, I am standing on the cold edge of grief."

The wet, green landscape I live in now is a world away from the Utah desert where Williams makes her home, and yet these essays speak directly to my soul -- and not just because I'm a former desert-dweller. Erosion is a work of beauty, sorrow, joy, rage, and bottomless compassion.

"Let us pause and listen and gather our strength with grace," she writes, "and move forward like water in all its manifestations: flat water, white water, rapids and eddies, and flood this country with an integrity of purpose and patience and persistence capable of cracking stone."

Here on quiet hillside in Devon, as the springtime unfolds in all of its wonder and the pandemic rolls on in all of its horror, I've been finding strength in Williams' words, and also in the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke. Plagued by poor health throughout his working life (eventually diagnosed as leukemia), Rilke knew a thing or two about living with the dark. He is a writer I keep returning to, at every stage of life, and he never fails me. Today it's this, from Sonnets to Orpheus, that is giving me courage:

Quiet friend who has come so far,

feel how your breathing makes more

feel how your breathing makes more

space around you.

Let this darkness be a bell tower

and you the bell. As you ring,

what batters you becomes your strength.

Move back and forth into the change.

What is it like, such intensity of pain?

If the drink is bitter, turn yourself to wine.

In this uncontainable night,

be the mystery at the crossroads of

your senses,

the meaning discovered there.

And if the world has ceased to hear you,

say to the silent earth: I flow.

To the rushing water, speak: I am.

Words: The Terry Tempest William quotes above and in the picture captions are from Erosion: Essays of Undoing (Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019). For a further taste of this exquisite book, you can read one of William's essays online here. Please don't miss it. Rainer Maria Rilke's poem "Let This Darkness Be a Bell Tower" is from Sonnets to Orpheus: Book II, 29. This lovely translation is from In Praise of Mortality: Selections from Rilke's Duino Elegies & Sonnets, translated by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows (Echo Point Books, 2016). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The drawing is by British illustrator Helen Stratton (1867-1961), who was born in India, trained in London, and spent much of her working life in London and Bath. The photographs are of the waterfall on our hill, swelled with rain.

May 4, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, some songs to welcome in the May....

Above: "Hal-An-Tow" sung by the hugely influential English folk group The Watersons, from Yorkshire. This performance was filmed for the BBC documentary Travelling for a Living (1965). The song appeared on The Waterson's album Frost and Fire (1965), where A.L. Lloyd wrote on the liner notes:

"The green calendar of spring has many songs, dances, and shows, particularly around the opening days of May. Here and there are clear traces of old cults and superstitions (well-dressing against droughts, etc.) but generally their original meaning is lost. So the customs are transformed into ritual spectacles, festivities, distractions, opportunities for a good time, such as the old May Games that once comprised four sections: the election and procession of the May king and queen: a sword or Morris dance of disguised men; a hobby horse dance; a Robin Hood play. The Hal-an-Tow song was sung for the procession that ushered in the summer."

Below: "The Night Before May Day" by Lisa Knapp, a London-based folk musician who has long been interested in the traditional songs of the season. I recommend her fine album Till April is Dead: A Garland of May, which is deeply folkloric, as well as her five-track release, Hunt the Hare: A Branch of May.

Above: "Hail! Hail! the First of May" performed by Jackie Oates, a folksinger and fiddle/viola player from Staffordshire. The song appeared on her lovely album The Spyglass and the Herringbone (2015).

Below: "May the Kindness," recorded by Oates on an earlier album, Hyperboreans (2009).

Above: "May Morning Dew" performed by Scottish folksinger Siobhan Miller, with Kris Drever, Innes White, Megan Henderson, John Lowrie, and Euan Burton. The song appears on her gorgeous new album, All is Not Forgotten (2020).

Below: "The Banks of the Sweet Primroses" (also known as "When I Roved Out") performed by Josienne Clarke and Ben Walker for the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards (2015). Their most recent album is Seedlings All (2018).

Above: "May Song" by the Oxfordshire folk band Magpie Lane, from their album Jack-in the Green: English Songs and Tunes (1998).

For the folklore of maypoles, Jack-in-the-Green, and other May Day traditions, go here.

May 3, 2020

The Bluebell Path

In this final post for Wildflower Week, I'm following Tilly on a bluebell path...which in folklore (as we discussed earlier) is a dangerous thing to do, for the bluepath path is the way into Faerie, and doesn't always lead home again. Like most of the season's wildflowers, bluebells are an ephemeral pleasure, here today and gone tomorrow. If I want to enjoy them fully then I must take the time to be outdoors right now, not wait until the day's chores are finished and goals are met. As a working artist tied to schedules and deadlines, my mind often dwelling in the past or the future, they pull me firmly back to present: to this fragrant, blue-tinted hillside, experienced with all of my senses.

Like every writer, I'm often asked where I find inspiration for my work. There's no single answer to the question, of course, for all kinds of things go into each author's creative mix: our personal histories, experiences, interests, and obsessions, along with the influence of other artists and other works of art. But for me, most of all, inspiration comes from the land: from the folklore-steeped Devon countryside, from the myth-haunted deserts of the American south-west, from the paths I've walked over and over again, all my senses open to hearing their stories.

Ursula K. Le Guin has this to say on the subject of inspiration:

"It's a big question -- where do writers get their ideas, where do artists get their visions, where do musicians get their music? It's bound to have a big answer. Or a whole lot of them. One of my favorite answers is this: Somebody asked Willie Nelson how he thought up his tunes, and he said, 'The air is full of tunes, I just reach up and pick one.'

"For a fiction writer -- a storyteller -- the world is full of stories, and when story is there, it's there; you just reach up and pick it.

"Then you have to be able to tell it to yourself.

"First you have to be able to wait. To wait in silence. Listen for the tune, the vision, the story. Not grabbing, not pushing, just waiting, listening, being ready for it when it comes. This is an act of trust. Trust in yourself, trust in the world. The artist says, 'The world will give me what I need and I will be able to use it rightly.'

"Readiness -- not grabbiness, not greed -- readiness: willingness to hear, to listen carefully, to see clearly and accurately -- to let the words be right. Not almost right. Right. To know how to make something out of the vision; that's what practice is for. Because being ready doesn't mean just sitting around, even if it looks like that's what most writers do; artists practice their art continually, and writing happens to involve a lot of sitting. Scales and finger exercises, pencil sketches, endless unfinished and rejected stories. The artist who practices knows the difference between practice and performance, and the essential connection between them. The gift of those seemingly wasted hours and years is patience andf readiness; a good ear, a keen eye, a skilled hand, a rich vocabulary and grammar. The gift of practice to the artist is mastery, or a word I like better, 'craft.'

"With those tools, those instruments, with that hard-earned mastery, that craftiness, you do your best to let the 'idea' -- the tune, the vision, the story -- come through clear and undistorted. Clear of ineptitude, awkwardness, amateurishness; undistorted by convention, fashion, opinion.

"This is a very radical job, dealing with the ideas you get if you are an artist and take your job seriously, this shaping a vision into the medium of words. It's what I like to do best in the world, and what I like to talk about when I talk about writing. I could happily go on and on about it. But I'm trying to talk about where the vision, the stuff you work on, the 'idea,' comes from, so:

"The air is full of tunes. A piece of rock is full of statues. The earth is full of visions. The world is full of stories.

"As an artist, you trust that."

The world is, indeed, full of stories upon stories...but sometimes I find that the quiet tales of the land, and my owner inner voice, are drowned out by the roar of the stories pressing in from the world outside: the urgent stories of politics, pandemics, economics, ecological crisis, all of them important, all of them overwhelming. On those days when "the world is too much with us," I lace on my boots, head for the hills, and let the roar diminish behind me. We need the quieter stories too...or, at least, I know that I need them. So I follow my dog on the bluebell path, and a different world is restored to me. Call it nature, call it Faerie, call it the place where poems and tales pluck at my sleeve saying: Tell me next. Tilly and I vanish into the blue....

And somehow we always find our way home.

Words: The passage above is from "Where Do You Get Your Ideas From?" by Ursula K. Le Guin, a talk for the Portland Arts & Lectures series, October, 2000, published in The World Spit Open (Tin House Books, 2014). Pictures: Walking the bluebell path.

May 2, 2020

Seasons, cycles, and Arum maculatum

Beltane has passed, and now the Great Wheel brings us to an enchanting and enchanted time of year, the turning of one season to the next: the liminal space between the quickening spring and the fecundity of summer. In folklore, the days of the In-Between have a particular magical potency. Certain herbs are gathered, following the cycles of the moon. Certain stories are told at this time of the year and no other. Certain flowers and leaves are brought into the house (conferring love, or health, or protection from fairy mischief), while others are best left to the wild, or avoided altogether.

Arum maculatum is a woodland plant in the later category. Emerging each year just before Beltane, it brings a fresh green cheer to the woods -- and yet it must be treated with care, for touching this plant can cause allergic reactions ranging from mild to severe, and its orange-red berries, beloved by rodents, are poisonous to everyone else.

Arum maculatum is a woodland plant in the later category. Emerging each year just before Beltane, it brings a fresh green cheer to the woods -- and yet it must be treated with care, for touching this plant can cause allergic reactions ranging from mild to severe, and its orange-red berries, beloved by rodents, are poisonous to everyone else.

I'm terribly fond of them nonetheless, and wait for them eagerly every year, noting their slow emergence as the daffodils begin to fade. Then, when the weather begins to warm, these lusty plants leap up bold as you please, unfurling their spear-shaped leaves to reveal a fleshy spadix in a pale green hood. Here in Devon, they're known by a number of names: cuckoo-pint, soldiers diddies, priest's pintle, wake robin, willy-lily, stallions-and-mares, and lords-and-ladies, all of them with rude connotations. In America, you probably know them best as Jack-in-the-pulpits.

The folklore attached to Arum maculatum has an equally zesty nature. The plant was associated with Britain's old May Day traditions, which included sexual congress in the fields to ensure the land's fertility. As such, it was deemed a "merry little plant" until Victorian times, and then denounced as devilish, lewd, and symbolic of unbridled sin. (Young girls were warned they must never touch it, because it could make them pregnant.) Herbalists from ancient Greece to medieval Britain extolled the arum's starchy roots for the making of aphrodisiacs, fertility aids, and other medicines focused on the reproductive system, while juice squeezed from the leaves was used for various skin complaints. Due to the arum's toxins, however, great skill was needed to render it safe. In the herb-lore of Wales and the West Country, the secret knowledge of how to to work with the plant came, it was said, from the local fairies -- handed down through mortal families entrusted to use it wisely.

As the days roll on towards Midsummer, the small patch of Armum maculatum in our woods will fade and disappear, leaving only their witchy stumps of toxic berries behind. And then the berries will vanish too, and full summer will be upon us. The brevity of their appearance is one of the things that endears these plants to me. I wait for them, enjoy their company, and then, a heartbeat later, they are gone. The movement of the woodland through its seasons reminds me there is vitality and a wondrous mystery to be found in nature's cycles and circles....

And as someone who works in the narrative arts, I find that I often need that reminder.

And as someone who works in the narrative arts, I find that I often need that reminder.

Narrative, in its most standard form, tends to run in linear fashion from beginning to middle to end. A story opens "Once upon a time," then moves -- prompted by a crisis or plot twist -- into the narrative journey: questing, testing, trials and tribulations -- and then onward to climax and resolution, ending "happily ever after" (or not, if the tale is a sad or ambiguous one). In the West, our concepts of "time" and "progress" are largely linear too. We circle through days by the hours of the clock, years by the months of the calendar, yet our lives are pushed on a linear track: infant to child to adult to elder, with death as the final chapter. Progress is measured by linear steps, education by grades that ascend year by year, careers by narratives that run along the same railway line: beginning, middle, and end.

But in fact, narratives are cyclical too if we stand back and look through a broader lens. Clever Hans will marry his princess and they will produce three dark sons or three pale daughters or no child at all until a fairy intervenes, and then those children will have their own stories: marrying frogs and turning into swans and climbing glass hills in iron shoes. No ending is truly an ending, merely a pause before the tale goes on.

As a folklorist and a student of nature, I know the importance of cycles, seasons, and circular motion -- but I've grown up in a culture that loves straight lines, beginnings and ends, befores and afters, and I keep expecting life to act accordingly, even though it so rarely does. Take health, for example. We envision the healing process as a linear one, steadily building from illness to strength and full function; yet for those of us managing  long-term conditions, our various trials don't often lead to the linear "ending-as-resolution" but to the cyclical "ending-as-pause": a time to catch one's breath before the next crisis or plot twist sets the tale back in motion.

long-term conditions, our various trials don't often lead to the linear "ending-as-resolution" but to the cyclical "ending-as-pause": a time to catch one's breath before the next crisis or plot twist sets the tale back in motion.

Relationships, too, are cyclical. Spousal relationships, family relationships, friendships, work partnerships: they aren't tales of linear progression, they are tales full of cycles, circles, and seasons. The path isn't straight, it loops and bends; the narrative side-tracks and sometimes dead ends. We don't progress in relationships so much as learn, change, and adapt with each season, each twist of the road.

As a writer and a reader, I'm partial to stories with clear beginnings, middles, and ends (not necessarily in that order in the case of fractured narratives) -- but when I'm away from the desk or the printed page (or the cinema or the television screen), I am trying to let go of the habit of measuring my life in a strictly linear way. Healing, learning, and art-making don't follow straight roads but queer twisty paths on which half the time I feel utterly lost...until, like magic, I've arrived somewhere new, some place I could never have imagined.

I want especially to be rid of the tyranny of Before and After. "After such-and-such is accomplished," we say, "then the choirs will sing and life will be good." When my novel is published. When I get that job. When I find that partner. When I lose ten pounds. No, no, no, no. Because even if we reach our goal, the heavenly choirs don't sing -- or if they do sing, you quickly discover it's all that they do. They don't do your laundry, they don't solve all your problems. You are still you, and life is still life: a complex mixture of the bad and the good. And now, of course, the goal posts have moved. The Land of After is no longer a published book, it's five books, a best-seller, a major motion picture. You don't ever get to the Land of After; it's always changing, always shimmering on the far horizon.

I don't want to live after, I want to live now. Moving with, not against, life's cycles and seasons, the twists and the turns, the ups and the downs, appreciating it all.

Today, I walked among the season's wildflowers, chose a few to bring back to the studio -- where they sit on the bookshelves in a pickle jar, glowing as bright as the sun and the moon. At my desk, I work in a linear artform, writing words in a line across a ruled page -- and the flowers remind me that cycles and seasons should be part of the narrative too. Circular patterns. Loops and digressions. Tales that turn and meander down paths that, surprise!, are the paths that were meant all along. Stories that reach resolutions and endings, but ends that turn into another beginning. Again. Again. Tell it again.

Once upon a time...

Words: The poem in the picture captions is from Jay Griffith's unusual and brilliant book on her journey with bipolar disorder, Tristimania (Penguin, 2016). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: The painting above is "Under the Dock Leaves" by Victorian fairy painter Richard Doyle ((1824-1883). The fairy tale drawings are by Helen Stratton, a British illustrator born in India (1867-1961). The charming little mouse is from Emma Mitchell's book Wild Remedy, which I recommend. The photographs of Arum maculatum and bluebells were taken in the woods behind my studio.

May 1, 2020

Up the May!

Happy May Day, everyone. Alas, out here in Devon and Cornwall all the usual May Day festivities have been cancelled due to the Covid-19 lockdown. There's no Obby Oss on the streets of Padstow, no Border Morris dancers bringing the sun up on Dartmoor, no maypoles, no lusty Jack-in-the-Greens. How will the seasons turn without them?

Tilly and I had our own private ceremony this morning, blessing the green in our own quiet way -- and we send that blessing from Dartmoor to each of you. Up the May!

The images above are from previous May Days: Howard dancing the Obby Oss down the high street of Chagford, with a Jack-in-Green close behind; and dancing the willow frame of the Jack around a Beltane fire. (To see more photos, go here.)

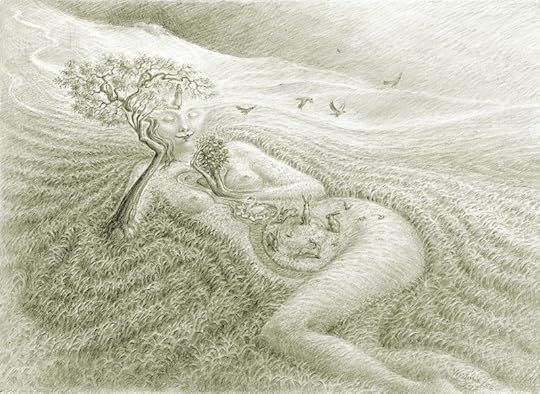

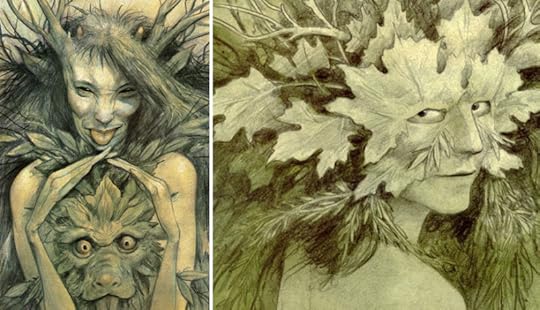

The art below is from village neighbours: Moor Maiden by Virginia Lee and two Green Women by Brian Froud. Despite the lockdown and physical distancing, we are still a community. We are dancing in spirit.

The folklore of foxgloves

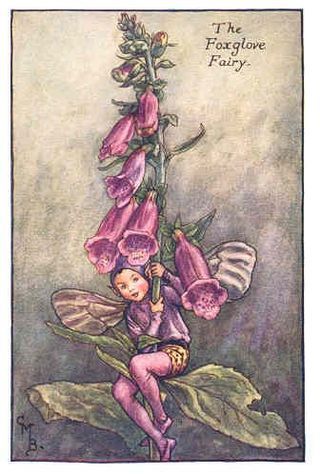

In the edge of the fields and along woodland trails, I see the green leaves of foxgloves begin to unfurl, but it will be some weeks yet before they grow tall and grace the hills with their spires of blooms.

Folklorists are divided on where the common name for Digitalis purpurea comes from. In some areas of the British Isles it's believed be a corruption of "folksglove," associating the flowers with the fairy folk, while in others the plant is also known as "fox fingers," its blossoms used as gloves by the foxes to keep dew off their paws. Another theory suggests that the name comes from the Anglo-Saxon word foxes-gleow, a "gleow" being a ring of bells. This is connected to Norse legends in which foxes wear the bell-shaped foxglove blossoms around their necks; the ringing of bells was a spell of protection against hunters and hounds.

Foxgloves give us digitalin, a glysoside used to treat heart disease, and this powerful plant has been used for heart tonics since Celtic and Roman times. Botanist Bobby J. Ward gives us this account of early foxglove use in his excellent book A Contemplation Upon Flowers:

"An old Welsh legend claims to be the first to proscribe it, because the knowledge of its properties came to the meddygon, the Welsh physicians, in a magical way. The legend is loosely based on the early 13th century historical figure Rhiwallon, the physician to  Prince Rhys the Hoarse, of South Wales. Young Rhiwallon was walking beside a lake one evening when from the mist rose a golden boat. A beautiful maiden was rowing the boat with golden oars. She glided softly away in the mist before he could speak to her. Rhiwallon returned every evening looking for the maiden; when he did not find her, he asked advice from a wise man. He told Rhiwallon to offer her cheese. Rhiwallon did as he was told, the maiden appeared and took his offering. She came ashore, became his wife, and bore him three sons.

Prince Rhys the Hoarse, of South Wales. Young Rhiwallon was walking beside a lake one evening when from the mist rose a golden boat. A beautiful maiden was rowing the boat with golden oars. She glided softly away in the mist before he could speak to her. Rhiwallon returned every evening looking for the maiden; when he did not find her, he asked advice from a wise man. He told Rhiwallon to offer her cheese. Rhiwallon did as he was told, the maiden appeared and took his offering. She came ashore, became his wife, and bore him three sons.

"After the sons grew and the youngest became a man, Rhiwallon's wife rowed into the lake one day and returned with a magic box hinged with jewels. She told Rhiwallon he must strike her three times so that she could return to the mist forever. He refused to hit her, but the next morning as he finished breakfast and prepared to go to work, Rhiwallon tapped his wife affectionately on the shoulder three times. Instantly a cloud of mist enveloped her and she disappeared. Left behind was the bejeweled magic box. When the three sons opened it, they found a list of all the medicinal herbs, including foxglove, with full directions for their use and healing properties. With this knowledge the sons became the most famous of physicians."

Foxglove is a plant beloved by the fairies, and its appearance in the wild indicates their presence. Likewise, fairies can be attracted to a dometic garden by planting foxgloves. Dew collected from the blossoms is used in spells for communicating with fairies, though gloves must be worn when handling the plant as digitalis can be toxic.

In the Scottish borders, foxgloves leaves were strewn about babies' cradles for protection from bewitchement, while in Shropshire they were put in children's shoes for the same reason (and also as a cure for Scarlet Fever). Picking foxglove flowers is said to be unlucky. Here in Devon and Cornwall, this is because it robs the fairies, elves, and piskies of a plant they particularly delight in; in the north of England, foxglove flowers in the house are said to allow the Devil entrance.

In the Scottish borders, foxgloves leaves were strewn about babies' cradles for protection from bewitchement, while in Shropshire they were put in children's shoes for the same reason (and also as a cure for Scarlet Fever). Picking foxglove flowers is said to be unlucky. Here in Devon and Cornwall, this is because it robs the fairies, elves, and piskies of a plant they particularly delight in; in the north of England, foxglove flowers in the house are said to allow the Devil entrance.

In Roman times, foxglove was a flower sacred to the goddess Flora, who touched Hera on her breasts and belly with foxglove in order to impregnate her with the god Mars. The plant has been associated with midwifery and women's magic ever since -- as well as with "white witches" (practitioners of benign and healing magic) who live in the wild with vixen familiars, the latter marked by bells made of foxglove blossoms tied around their necks. In medieval gardens, the plant was believed to be sacred to the Virgin Mary. In the earliest recordings of the Language of Flowers, foxgloves symbolized riddles, conundrums, and secrets, but by the Victorian era they had devolved into the more negative symbol of insincerity.

A lovely old legend told here in the West Country explains why foxgloves bob and sway even when there is no wind: this is the plant bowing to the fairy folk as they pass by. Wherever foxgloves grow in abundance you can be sure it's a place where the fey are present, for these flowers thrive in a loam of old stories, riddles, secrets, and Otherworldly enchantment.

The foxes themselves pad through folklore and myth as mischievous Tricksters in various forms: both clever and foolish, creative and destructive, perfectly civilized and utterly wild. Fox Tricksters appear in the popular tales of many cultures around the world, including Aesop's Fables from ancient Greece, the "Reynard" stories of medieval Europe, the "Giovannuzza" tales of Italy, the "Brer Fox" lore of the American South, and the diverse indigenous stories of North and South America. At the darker end of the fox-lore spectrum, however, we find creatures of a distinctly more dangerous cast: Reynardine, Mr. Fox, kitsune (the Japanese fox wife), kumiho (the Korean nine-tailed fox), and other treacherous shape-shifters.

Fox women appear in many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkle (in a good article on the subject) are seductive creatures who "entice unwary scholars and travelers with the lure of their sexuality and the illusion of their beauty and riches. They drain the men of their yang -- their masculine force -- and leave them dissipated or dead (much in the same way La Belle Dame Sans Merci in Keats's poem leaves her parade of hapless male victims).

Fox women appear in many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkle (in a good article on the subject) are seductive creatures who "entice unwary scholars and travelers with the lure of their sexuality and the illusion of their beauty and riches. They drain the men of their yang -- their masculine force -- and leave them dissipated or dead (much in the same way La Belle Dame Sans Merci in Keats's poem leaves her parade of hapless male victims).

"Korean fox lore, which comes from China (from sources probably originating in India and overlapping with Sumerian lamia lore) is actually quite simple compared to the complex body of fox culture that evolved in Japan. The Japanese fox, or kitsune, probably due to its resonance with the indigenous Shinto religion, is remarkably sophisticated. Whereas the arcane aspects of fox lore are only known to specialists in other East Asian countries, the Japanese kitsune lore is more commonly accessible. Tabloid media in Tokyo recently identified the negative influence of kitsune possession among members of the Aum Shinregyo (the cult responsible for the sarin attacks in the Tokyo subway). Popular media often report stories of young women possessed by demonic kitsune, and once in a while, in the more rural areas, one will run across positive reports of the kitsune associated with the rice god, Inari."

The "nine-tailed fox" of China and Japan is often (but not always) a demonic spirit, malevolent in intent. It takes possession of human bodies, both male and female, moving for one victim to another over thousands of years, seducing other men and women in order to dine on their hearts and livers. Human organs are also a delicacy for the nine-tailed fox, or kumiho, of Korean lore -- although the earliest texts don't present the kumiho as evil so much as amoral and unpredictable...occasionally even benevolent...much like the faeries of English folklore.

There are fox lovers and wives in the Western tradition, but their tales are less well known; and they tend, by and large, to be better disposed to the men that they take to their beds. Marriage to a fox is challenging at best, for they are not mortal, they are creatures of the wild: mysterious, independent, and not to be tamed nor taken for granted. (My favourite fox woman story of this sort is retold by Dartmoor mythographer Martin Shaw in his brilliant book Scatterlings. )

There are fox lovers and wives in the Western tradition, but their tales are less well known; and they tend, by and large, to be better disposed to the men that they take to their beds. Marriage to a fox is challenging at best, for they are not mortal, they are creatures of the wild: mysterious, independent, and not to be tamed nor taken for granted. (My favourite fox woman story of this sort is retold by Dartmoor mythographer Martin Shaw in his brilliant book Scatterlings. )

In the West, it's the fox men we need to be wary of -- such as Reynardine (in the old folk ballad of that name), a glib and handsome were-fox who lures young maidens to a bloody death. The title character of the fairy tale Mr. Fox, is cousin to the kumiho and Reynardine, with a bit of Bluebeard mixed in for good measure: he promises marriage to a gentlewoman while his lair is littered with her predecessors' bones. Neil Gaiman draws inspiration from the tale in his wry, wicked poem "The White Road" -- while Jeannine Hall Gailey, by contast, takes a more sympathetic view of shape-shifting foxes in "The Fox-Wife's Invitation," written from a kitsune's point of view.

There are a number of good novels that draw upon fox legends -- foremost among them, Kij Johnson's exquisite The Fox Woman, which no mythic fiction reader should miss. I also recommend Neil Gaiman's The Dream Hunters (with the Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano); Larissa Lai's When Fox Is a Thousand; and Ellen Steiber's gorgeous A Rumor of Gems (as well as her heart-breaking novella "The Fox Wife," published in Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears). Alice Hoffman's disquieting Here on Earth is a contemporary take on the Reynardine/Mr. Fox theme, as is Helen Oyeyemi's Mr. Fox, a complex work full of stories within stories within stories. For younger readers, try the "Legend of Little Fur" series by Isobelle Carmody. And for mythic poetry, I especially recommend She Returns to the Floating World by Jeannine Hall Gailey and Sister Fox���s Field Guide to the Writing Life by Jane Yolen. (More fox tales are listed here.)

For the fox in myth, legend, and lore, try: Fox by Martin Wallen; Reynard the Fox, edited by Kenneth Varty; Kitsune: Japan's Fox of Mystery, Romance, and Humour by Kiyoshi Nozaki; Alien Kind: Foxes and Late Imperial Chinese Narrative by Raina Huntington; The Discourse on Foxes and Ghosts: Ji Yun and Eighteenth-Century Literati Storytelling by Leo Tak-hung Chan; The Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary Japanese Inari Worship, by Karen Smythers; and an interesting post on the fox in folklore, literature and art by artist David Hollington.

Although chancy to encounter in myth, and too wild to domesticate easily (in stories and in life), some of us long for foxes nonetheless: for their musky scent, their hot breath, their sharp-toothed magic. "I needed fox," wrote Adrienne Rich:

Badly I needed

a vixen for the long time none had come near me

I needed recognition from a

triangulated face burnt-yellow eyes

fronting the long body the fierce and sacrificial tail

I needed history of fox briars of legend it was said she had run through

I was in want of fox

And the truth of briars she had to have run through

I craved to feel on her pelt if my hands could even slide

past or her body slide between them sharp truth distressing surfaces of fur

lacerated skin calling legend to account

a vixen's courage in vixen terms

Now go softly. Go gently. Go warily. Soon the tall spires of foxgloves will bloom, and then you will know that the Good Folk are near. Look for their gloves discarded on the path. Listen for the sound of foxglove bells. Breathe in the sharp scent of the wild...and go home, changed.

You will dream of foxes.

Art: Pages from The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady by Edith Holden (1871-1920), "Foxglove Fairy" by Cicely Mary Barker (1875-1973), "Foxglove" by botanical artist Christie Newman, a page from Flora Londinensis by English apothecary & botanist William Curtis (1746-1799), "Foxgloves" by Kelly Louise Judd, "Fox Woman" by Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997), "Fox Nest" by Flora McLachlan, "The Princess and the Fox" by H.J. Ford (1860-1941), "The Fox and Ivy" by Jessica Roux, "Crossing an Iced-Over Stream" by Gina Litherland, "The Winter Guest" by David Hollington, a small illustration by Julianna Swaney, "Little Evie in the Wild Wood" by Catherine Hyde, The beautiful fox photographs are by by wildlife photographer Richard Bowler. All rights reserved by the artists.

Words: The Bobby J. Ward passage quotes above is from A Contemplation on Flowers: Garden Plants in Myth & Literature (Timber Press, 2009). All rights reserved by the author.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers