The Dark Forest

In late January, Howard and I gave a talk here in Chagford titled The Path Through the Dark Forest, discussing how myth and mythic fiction can help us through challenging times. Little did we know how appropriate the subject would be in the months ahead....

A journey through the dark of the woods is a common motif in fairy tales: young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach their destiny, or they find themselves abandoned there. The road is long and treacherous, prowled by ghosts, ghouls, wicked witches, wolves and the more malign sorts of faeries....but helpers also appear on the path: wise crones, good faeries, and animal guides, often cloaked in unlikely disguise. The hero's task is to tell friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

"When you enter the woods of a fairy tale, and it is night, the trees tower on either side of the path," writes Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew. "They loom large because everything in the world of fairy tales is blown out of proportion. If the owl shouts, the otherwise deathly silence magnifies its call. The tasks you are given to do (by the witch, by the stepmother, by the wise old woman) are insurmountable -- pull a single hair from the crescent moon bear's throat; separate a bowl's worth of poppy seeds from a pile of dirt. The forest seems endless. But when you do reach the daylight, triumphantly carrying the particular hair or having outwitted the wolf; when the owl is once again a shy bird and the trees only a lush canopy filtering the sun, the world is forever changed for your having seen it otherwise."

At the time of our talk, my own path was sunny and clear...but then the road dipped and plunged into the dark pines. I spent a few weeks in the forest's undergrowth while coping with serious health issues, and just as the road seemed to clear once again, I learned that my youngest brother had died, in a way that was sudden, shocking, and desperately sad. The next weeks were a blur, overwhelmed by the numerous tasks that the death of a loved one requires -- complicated by my great distance from the small Texas town where my brother had died, yet eased by the steady support of friends (both my brother's and mine, many blessings upon them all). As those heartbreaking tasks finally came to an end, I emerged from a haze of grief to find Corvid-19 spreading across Europe. Now the whole of Britain has gone into lock-down, while virus infection rates rise and rise.

Howard was meant to be in Berlin right now, as part of his year-long "Journey Into the Heart of the Fool." Just two weeks ago we were still debating whether it was wise for him to travel or not -- but life changes fast, and our decision to keep him home quickly proved to be the right one. Between his teaching/directing work, Fool training and PhD studies, he's been on the road a lot this year -- which has all ground to a halt as theaters and universities shut their doors. The loss of work is a worry, of course; but I'm deeply relieved that he's home with us. (And the hound is over the moon to have him back.)

As those of you who are also on lock-down know, daily life is now full of practical and emotional challenges; each day seems to bring brand new ones, and nothing has settled yet into a routine. I don't discount the gravity of those challenges (those of us with "high risk" medical conditions know full well the danger we're facing), but the questions I want to focus on here on Myth & Moor are these: How do we create thoughtful and artful lives despite that danger? How do live through the hard days ahead as artists?

For me, these are not unfamiliar questions. My particular health condition affects my immune system, so I'm already used to periods of self-isolation. I'm used to putting time and thought each day into the practical business of staying alive, and of taking mortality seriously. For many of us with a range of illnesses to manage, this is already familiar territory, so perhaps we can be of particular help now to those for whom such concerns are new. We know how to live in the shadow of death. We know how to let fear and joy co-exist inside us. We've learned to live without certainty. We've learned to accept we're not in full control. We've learned to keep working, to keep creating, to keep showing up and to live fully in the present. Just as important, we've learned to forgive ourselves on those hard, weary, painful days when we simply can't.

Because I'm writer and scholar of stories, it's to stories I turn when the going gets rough. It's through stories I find the tools I need: imagination, wonder, beauty, compassion for others, compassion for myself, courage, persistence, understanding, discernment...and narratives that make sense of it all.

In Wonder and Other Survival Skills, H. Emerson Blake argues for the cultivation of "wonder" especially:

"The din of modern life constantly pulls our attention away from anything that is slight, or subtle, or ephemeral," he says. "We might look briefly at a slant of light while walking through a parking lot, but then we're on to the next thing: the next appointment, the next flickering headline, the next task, the next thing that has to be done before the end of the day. But maybe it's for just that reason -- how busy we are and distracted and connected we are -- that wonder really is a survival skill. It might be the thing that reminds us of what really matters, and of the greater systems that our lives are completely dependent on. It might be be the thing that helps us build an emotional connection -- an intimacy -- with our surroundings that, in turn, would make us want to do anything we can to protect them. It might build our inner reserves, give us the strength to turn ourselves outward and meet those challenges with grace.

"In a day and age when we are reminded unendingly of the urgency and magnitude of the problems we face, wonder may seem like something we no longer have time for -- a luxury, or a dalliance. But in one of Orion's live web events, David Abram said this:

'When we trivialize people's sensory attachment to the beauty of their place, to the beauty of the land where they live...we need to at least be aware that it is undermining peoples' sense of solidarity to the rest of the earth. Sensory perception is the glue that binds our separate nervous systems into the encompassing ecosystem.'

"In other words, Abram ties our terrible, selfish decision-making about how we treat the earth -- what we take from it, what we put into it, what we demand of it -- directly to our estrangement from its beauty. He is saying that wonder is the antidote. That wonder is the thing that can save us."

Myth, folklore, fantasy fiction, and mythic arts are vibrant sources of wonder, and thus good medicine for these troubled times. We must keep creating such stories, and sharing such stories, for wondrous tales are not frivolous things. When created with heart, honesty, and skill, they are fresh water and bread to sustain us.

In the days ahead, I'm going to talk about some of the books that I have carried with me through the deep dark forest, highlight art that shines silver light on the path, and share (as always) the magic and beauty of the land here on Dartmoor's edge. I'm also going to re-visit old posts that might have something new to tell us right now: on living slowly, on living rooted in "place," and on embracing the quieter rhythms of life that a pandemic lock-down requires.

I hope you will share your own stories here too, in the Comments section below each post. How are you doing? How are you coping? Are you still creating...and if so, how? And if not, why? (No judgements on the latter, I promise; just community and solidarity.)

"[W]hile the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new," wrote the great James Baldwin, "it always must be heard. There isn���t any other tale to tell, it���s the only light we���ve got in all this darkness."

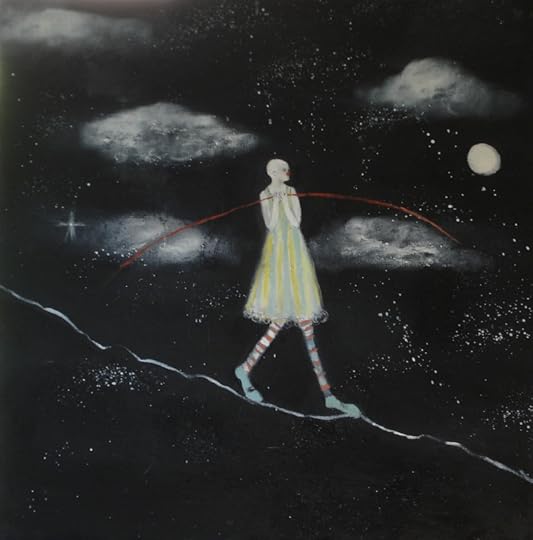

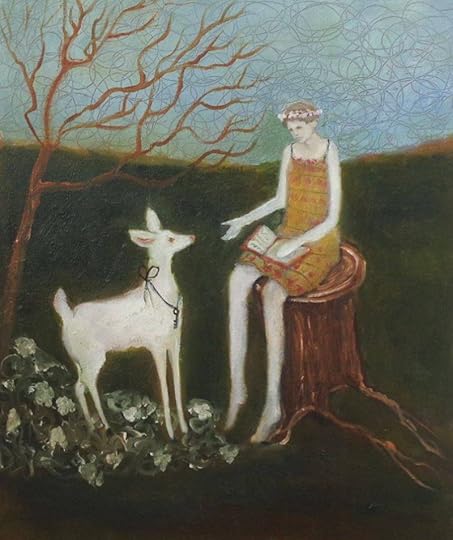

Pictures: The art above, of course, is by the wonderful American painter Jeanie Tomanek. All rights reserved by the artist. Please visit her website to see more.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers