Terri Windling's Blog, page 186

July 11, 2013

Into the Woods, 18: Following the Deer (IV)

Psalm

by George Oppen

Veritas sequitur ...

In the small beauty of the forest

The wild deer bedding down —

That they are there!

Their eyes

Effortless, the soft lips

Nuzzle and the alien small teeth

Tear at the grass

The roots of it

Dangle from their mouths

Scattering earth in the strange woods.

They who are there.

Their paths

Nibbled thru the fields, the leaves that shade them

Hang in the distances

Of sun

The small nouns

Crying faith

In this in which the wild deer

Startle, and stare out.

skin

by Lynn Hardaker

i press

ochred hands onto the walls of this cave. my skin. my shelter.

my fingers crawl like night insects

to sing the running of the animals,

the wind of the chase, the beating of hearts and hooves

across the plains, of stone and dust.

each night i dream the chase

across my eyes’ black-lidded sky

each night

my body slick with sweat and smeared with ash

i run

as i run,

i hear the beating of the drum i’ve made -

taught and resonant - from my own skin,

feel the weight of the weapon i’ve made

from my own bone.

i leave the fire-painted walls

of this illusion

and i run

under the cool, many-eyed gaze of the night

i run until i feel my heart will beat its last beat and tear through my skin

i stop

my fear as dry as the dirt in my mouth.

i lower my antlers to the pool

and drink the stars.

The Faces of Deer

by Mary Oliver

When for too long I don't go deep enough

into the woods to see them, they begin to

enter my dreams. Yes, there they are, in the

pinewoods of my inner life. I want to live a life

full of modesty and praise. Each hoof of each

animal makes the sign of a heart as it touches

then lifts away from the ground. Unless you

believe that heaven is very near, how will you

find it? Their eyes are pools in which one

would be content, on any summer afternoon,

to swim away through the door of the world.

Then, love and its blessing. Then: heaven.

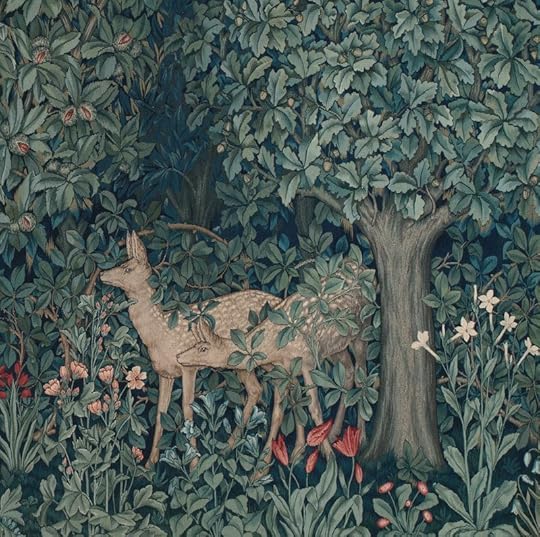

Deer tapestries above: The Woodland tapestry designed by John Henry Dearle for Morris & Co. (English, late 19th century); The Quest for the Holy Grail tapestry designed by William Morris for Morris & Co. (English, late 19th century); a detail from one of the four Devonshire Hunting Tapesteries (medieval French); one of the seven tapestries in the Hunt of the Unicorn series (medieval Dutch); and Tilly sits with the winged deer in the tapestry hanging over the studio sofa. (The design is medieval French.)

Publication credits: "Psalm" by George Oppen was published in New Collected Poems by George Oppen, 1965; "skin" by Lynn Hardaker was published in Mythic Delirium # 28, Winter/Spring 2013 issue; "The Faces of Deer" by Mary Oliver was published in New & Selected Poems, Vol. 2 by Mary Oliver, 2005.

July 10, 2013

Into the Woods, 18: Following the Deer (Part III)

In the earliest time,

when both people and animals lived on the earth,

a person could become an animal if he wanted to

and an animal could become a human being.

Sometimes they were people

and sometimes animals

and there was no difference.

All spoke the same language.

That was the time when words were like magic.

The human mind had mysterious powers.

A word spoken by chance

might have strange consequences.

It would suddenly come alive

and what people wanted to happen could happen -

all you had to do was to say it.

Nobody can explain this:

That's the way it was.

- after Nalugiaq (from Magic Words: Songs and Stories of the Netsilik Eskimos by Edward Field)

Ceremonial deer vessels from Chimbote, Santa Valley, Peru (100 BC-500 AD)

Ceremonial deer vessels from Chimbote, Santa Valley, Peru (100 BC-500 AD)

Iranian deer vessel, used for holding wine (1000-550 BC)

Iranian deer vessel, used for holding wine (1000-550 BC)

Native American olla from Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico. The exact date is unknown, but it's believed to be old, and the traditional "heartline deer" design even older.

Native American olla from Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico. The exact date is unknown, but it's believed to be old, and the traditional "heartline deer" design even older.

A ceramic deer vessel from the Hunal Tomb, Copan, Honduras (circa 437 AD)

A ceramic deer vessel from the Hunal Tomb, Copan, Honduras (circa 437 AD)

Enchanted is what they were

in the old stories, or if not that,

they were guides and rescuers of the lost,

the lonely, needy young men and women

in the forest we call the world.

That was back in a time

when we all had a common language.

- Lisel Mueller (from "Animals Are Entering Our Lives")

Doe and Deer Jars, made of blown glass, by American glass artist William Morris

, based in the Pacific Northwest.

Doe and Deer Jars, made of blown glass, by American glass artist William Morris

, based in the Pacific Northwest.

Deer in Trees bowl by American ceramicist C. Bacon

, based in New England.

Deer in Trees bowl by American ceramicist C. Bacon

, based in New England.

Deer and Doe porcelain boxes by English ceramicist Eleanor Bartleman

, based in Devon.

Deer and Doe porcelain boxes by English ceramicist Eleanor Bartleman

, based in Devon.

Long ago the trees thought they were people.

Long ago the mountains thought they were people.

Long ago the animals

thought they were people.

Someday they will say, long ago the humans

thought they were people.

- from a Native American (Tulalip) story recounted by Johnny Moses

The deer photographs above are: young fallow deer (by UK photographer Josh Smythe); a deer buck at Dunham Massey Deer Park, in north-west England, during the rutting season (rubbing antlers in grass is a common rutting behaviour); an early morning doe and deer encounter; and two white-tailed deer-people.

Into the Woods, 18: Following the Deer (III)

In the earliest time,

when both people and animals lived on the earth,

a person could become an animal if he wanted to

and an animal could become a human being.

Sometimes they were people

and sometimes animals

and there was no difference.

All spoke the same language.

That was the time when words were like magic.

The human mind had mysterious powers.

A word spoken by chance

might have strange consequences.

It would suddenly come alive

and what people wanted to happen could happen -

all you had to do was to say it.

Nobody can explain this:

That's the way it was.

- after Nalugiaq (from Magic Words: Songs and Stories of the Netsilik Eskimos by Edward Field)

Enchanted is what they were

in the old stories, or if not that,

they were guides and rescuers of the lost,

the lonely, needy young men and women

in the forest we call the world.

That was back in a time

when we all had a common language.

- Lisel Mueller (from "Animals Are Entering Our Lives")

Long ago the trees thought they were people.

Long ago the mountains thought they were people.

Long ago the animals

thought they were people.

Someday they will say, long ago the humans

thought they were people.

- from a Native American (Tulalip) story recounted by Johnny Moses

The deer imagery above is: A photography of a young fallow deer by Josh Smythe; deer vessels from Chimbote, Santa Valley, Peru (100 BC-500 AD); Iranian deer vessel (1000-550 BC); Pueblo Indian bowl from Acoma, New Mexico (circa 19th century); a photograph of a deer buck at Dunham Massey Deer Park, in north-west England, during the rutting season; a ceramic deer vessel from the Hunal Tomb, Copan, Honduras (circa 437 AD); Doe and Deer Jars, made of blown glass, by American glass artist William Morris; "Deer in Trees" bowl by American potter C. Bacon; Deer and Doe porcelain boxes by Devon ceramicist Eleanor Bartleman; and two white-tailed deer-people.

July 9, 2013

Into the Woods, 18: Following the Deer (Part II)

How to See Deer

by Philip Booth (1925-2007)

Forget roadside crossings.

Go nowhere with guns.

Go elsewhere your own way,

lonely and wanting. Or

stay and be early:

next to deep woods

inhabit old orchards.

All clearings promise.

Sunrise is good,

and fog before sun.

Expect nothing always;

find your luck slowly.

Wait out the windfall.

Take your good time

to learn to read ferns;

make like a turtle:

downhill toward slow water.

Instructed by heron,

drink the pure silence.

Be compassed by wind.

If you quiver like aspen

trust your quick nature:

let your ear teach you

which way to listen.

You've come to assume

protective color; now

colors reform to

new shapes in your eye.

You've learned by now

to wait without waiting;

as if it were dusk

look into light falling:

in deep relief

things even out. Be

careless of nothing. See

what you see.

Finis

The deer imagery above is: a photograph of deer in Glen Etive, Scotland; "This Isn't Happiness" by Myeongbeom Kim; photograph of a leaping row deer; an old illustration of a leaping dear (artist unknown); photograph of tiny muntjac fawn; "White-tail Fawn Reclining" by Mark Rossi; photograph of deer in the morning mist; sketch of deer on the Isle of Arran, Scotland, by Barbara Brassey (1911-2010); "A Forest" by Flora McLachlan, "Fawn" by Kiki Smith, "Young Deer" by Nicky Clacy; photograph of a white-tail deer and fawn; "Two Deer" by Franz Marc (1880-1916); "Deer in Ocean Surf" by Connie Cooper Edwards; "Deer" by Julianna Swaney; white doe photograph; "White Fawn" by Kelly Louise Judd; roe biuck photograph; "Nature Girl" by Christina Bothwell & "Queen of Beasts" by Fidelma Massey; "Out of Narnia" by Su Blackwell; "Deer" by Akitaka Ito; and "The Low Edge of the Storm" by Catherine Hyde.

Into the Woods, 18: Following the Deer (Part I)

"As long as people have lived or hunted alongside the deer's habitats," says writer and mythographer Ari Berk (in "Where the White Stag Runs"),

"there have been stories: some of kindly creatures who become the wives

of mortals; or of lost children changed into deer for a time, reminding

their kin to honor the relationship with the Deer People, their close

neighbors. And there are darker tales, recalling strange journeys into

the Otherworld, abductions, and dangerous transformations that don't end

well at all. But all stories about the deer share some common ground by

showing us that the line between our world and theirs is very thin

indeed."

Ovid's Metamorphoses, Ari continues, tells the story "of youthful Actaeon who

spends the day hunting with his dogs on the hillsides, catching so much

game that the slopes run red with blood. As the sun ascends the sky, he

calls off the chase, bidding his comrades retire with the promise of

renewing the hunt early the next day. Then he does a dangerous thing: he

wanders for a time in a wood he does not know, and so comes by accident

to the sacred grotto where Diana is accustomed to bathe with her

nymphs. To Actaeon's great misfortune, he spies the goddess of the hunt

naked and she, seeing him, blushes.

Then lifting up her hands, she throws water in Actaeon's face and he

flees that place. As he wanders back to find his friends he hears his

dogs barking and sees that they are chasing him. Confused he calls out

to them, but instead of his voice, he hears the bellowing of a great

stag, for stag he now is, transformed by the goddess's vengeful hand. So

he runs fast on four legs but soon his dogs chase him down and, tearing

him apart, find their old master toothsome indeed. The myth of Actaeon is an early example of the connection of deer

stories with the violation of taboos. Actaeon made three fatal errors:

overhunting the hillside, entering a sacred enclosure unknowingly, and

gazing upon the virgin mistress of the hunt. His punishment is perfectly

suited to address his errors for he learns to see the world, though

briefly, from the perspective of a shy creature who calls the wild home

and instinctively respects its boundaries.

"In the medieval Welsh Mabinogion, does and stags appear as

physical manifestations of the boundary between worlds. In the story of 'Pwyll,' the deer are followed into the forest during a hunt. But Pwyll,

the prince, and his dogs are soon separated from his companions and he

finds himself lost in the woods. Soon he hears other dogs and,

following their barking, comes upon a clearing in the woods where he

finds a strange pack—red-eared and white-furred—bearing down upon a

stag. Pwyll chases those dogs off and sets his own upon the stag

instead, most discourteously. When he later meets the owner of the

white dogs—who is none other than the Arawn, lord of the

Otherworld—satisfaction is demanded and Pwyll must repay Arawn by

assuming his form and exchanging places, traveling into the Otherworld

to kill one of Arawn's enemies. So following the deer is often a way

into the Otherworld, or a sign that we are very close to its borders."

as crows fly

in the dawn light

on the cold hill

the deer are running

the thud of their hooves

on the bed of the stream

is the drum that rocks

the roots of the birch

and the wind that shakes

the birch tree’s leaves

- Scottish poet Chris Powici (from "Deer")

Deer that roam the Western fairy tale tradition are guardians, guides, companions to the fairies, and occasionally fairies themselves in disguise -- or else they are men and women be-spelled, roaming the woods in animal-shape by day, briefly regaining their humanity each night. In Brother and Sister from Grimms' Fairy Tales, for example, two siblings flee their wicked stepmother through a

dark and fearsome forest. The path of escape lies across three

streams, and at each crossing the brother stops, intending to drink.

Each time his sister warns him away, but the third time he cannot

resist. He bends down to the water in the shape of a man and rises

again in the shape of a stag. Thereafter, the sister and her

brother-stag must live in a lonely hut in the woods . . . but

eventually, with

his sister’s help, (and after she marries a king), the young man resumes his true shape.

Ellen Steiber looked at this tale's archetypal patterns when writing her contemporary version, "In the Night Country" (published in The Armless Maiden). "Fairy tales are journey stories," she says in a beautiful essay on the subject. "They deal with initiation and

transformation, with going into the forest where one's deepest fears and

most powerful dreams are realized. Many of them offer a map for getting

through to the other side. Out of curiosity, I went back to the

patterns of three in [Brother and Sister], since the very rhythms of repetition set

them off and give them importance. There are three brooks, three days of

the hunt, and three times that the queen's ghost speaks [after the sister's marriage to the king, when her role as queen has been usurped by her step-sister]. Each of these

patterns presents challenge and transformation;

they are the places of power in the story, the points where true magic

occurs. In the first the brother is thirsty; he needs nourishment and

finally gets it, a difficult metamorphosis being the price. In the

second he must either follow his own deer nature or 'die of grief'; at great

risk he runs with the hunt, and that act takes both brother and sister

farther along on the path they must travel to a new state of being.

(It's worth noting that in the fairy tales one can rarely remain in the

forest — one takes what was found there and brings it back into the

world.)

In the third challenge, the king must recognize the [true] queen, an act that

will restore her to life and lead to a redress of wrongs, a final ending

of the curse, a coming into balance. As abuse [in a family] takes many forms, so does

salvation. Here are three of many acts that can get you through:

nourishing yourself, following your heart even at great risk, and being

seen for what you are."

Beloved, what can be, what was,

will be taken from us.

I have disappointed.

I am sorry. I knew no better.

A root seeks water.

Tenderness only breaks open the earth.

This morning, out the window,

the deer stood like a blessing, then vanished.”

- American poet and essayist Jane Hirshfield (from "Standing Deer")

In The

White Deer (a.k.a. The White Hind and The White Doe), from the French fairy tales of Madame d’Aulnoy,

a princess is cursed in infancy by a fairy who'd been insulted by her

parents. Disaster will strike, says the fairy, if the princess

sees the sun before her wedding day. Many years later, as she travels

to her wedding, a ray of sun penetrates her carriage. The princess

turns into a deer, jumps through the window, and disappears into the forest -- where she's eventually hunted by her own fiancé, who does not know what she has become.

As she flees the arrows of the royal hunting party, the prince is as "unescapable as memory" in this passage from Eve Sweetser's poem, "The White Hind at Bay":

She leads him through briars, bogs

scent-killing brooks — inexorably

the following fate comes on.

Always, till now, some twist has let her out.

In exhaulted desperation

she sees the cliff before her.

From teeth and knives

her white hide is no protection

"Leave off these fawnish fantasies,

her kind deer parents often said

"What's a white skin?

Does every third-born son

wed a princess?"

Can wild hope save her?

Can she be again

the princess she was in childhood

(or was it dreamed of?)

exquisite and beloved,

ideal and human both?

It is so far — so long ago

she left off thinking of glass slippers

accepted her four hooves.

two deer

came walking down the hill

and when they saw me

they said to each other, okay,

this one is okay,

let’s see who she is

and why she is sitting

on the ground like that,

so quiet, as if

asleep, or in a dream,

but, anyway, harmless;

and so they came

on their slender legs

and gazed upon me

not unlike the way

I go out to the dunes and look

and look and look

into the faces of the flowers;

and then one of them leaned forward

and nuzzled my hand, and what can my life

bring to me that could exceed

that brief moment?

- American poet Mary Oliver (from "The Place I Want to Get Back To")

"Deer is a common figure in American Indian myths, " notes Ari Berk, "often appearing

in stories that continue the focus on families, kinship, marriage,

child-rearing, hunting and pursuit. Among the Pueblos of the New Mexico,

stories are still told of Deer Boy, a baby left in the grass, abandoned

by its young mother, a girl of the village. It was a Deer Woman who

found the human child and brought him home to raise with her own fawns.

Time passed and the boy spent the days running with his fawn brothers

and sisters. Some time later, a hunter from the village noticed strange

tracks among those left by the Deer People. The Deer Woman knew the time

had come for the boy to return to his people. She readied him to be

caught by the hunter and told him what he must know about his real

mother and what she looked like. She told him that to remain among his

own people he must, upon returning to the village, be left alone and

unseen in a room for four days. So he was found by the hunter and taken

home and much happiness attended his homecoming. The boy told his family

he must be left alone for four days and they agreed. But his birth

mother, so impatient was she, stole a glance at her son before the four

days were finished. In an instant the boy took on the shape of a deer

and ran to the North where he joined his other mother and lived for the

rest of his days among the Deer People."

The Yaqui (Yoeme) people of the Sonoran desert traditionally divide themselves into

two related groups: the Vato'im (Baptized Ones), who remain in this

world and integrate seventeenth century Spanish Catholicism with the

rites of their own aboriginal religion, and the Surem (the Enchanted

People), who went away to the Wilderness World to preserve the ancient

ways. In the extraordinary Deer Dance, still performed at Easter and

other times in Arizona and northern Mexico, a dancer takes on the shape,

the movements, the consciousness of the sacred deer on the borderline

between these two worlds, blessing the ground he walks on. Yaqui Deer Songs

by Larry Evers and Felipe S. Molina is a beautiful account of a deer mythology that is not buried in history but still living,

still a vibrant part of everyday life for the modern Yoeme.

"Flower-cover fawn went out, enchanted, from each enchanted flower

wilderness world, he went out...," the singers sing as the deer dancer

moves, gourd rattles in his hands and strings of rattles bound around

his shins. A deer head rises over his own, antlers decorated with

flowers. "So this now is the deer person, so he is the deer person,

so he is the real deer person...." The drummers drum, the dancer

leaps, and it is the real deer person indeed.

Question: Can you tell us about what he is wearing?

Well, the hooves represent the deer’s hooves,

the red scarf represents the flowers from which he ate,

the shawl is for skin.

The cocoons make the sound of the deer walking on leaves and grass.

Listen.

Question: What is that he is beating on?

It’s a gourd drum. The drum represents the heartbeat of the deer.

Listen.

When the drum beats, it brings the deer to life.

We believe the water the drum sits in is holy. It is life.

Go ahead, touch it.

Bless yourself with it.

It is holy. You are safe now.

- Tohono O'Odham author Ofelia Zepeda (from "Deer Dance Exhibition")

Native American writer and educator Carolyn Dunn describes the Deer Woman tales she grew up with in a short, poetic essay on the subject:

"Deer Woman's specific magic and myth surrounds marriage and courtship

rituals," she says. "I write of Deer Woman from the

Cherokee/Muskogee/Seminole/Choctaw perspective because this is what I

know. But other cultures have encounters with Deer Woman or Deer Man.

Ella Cara Deloria recorded several traditional Dakota and Lakota

narratives which mirrored the Southeastern tribes' Deer Woman stories.

The Karuk, according to the Karuk artist and storyteller Lyn Risling,

have stories of the Deer Woman in which the spirit is associated with

fertility and maturation rituals and prepares young women for marriage.

The Southeastern stories are similar in that young people must be

instructed in the choosing of a societally-approved mate in order for

cultural survival and regeneration.

In these stories, a beautiful young woman meets a young man and

entrances him into a sexual relationship. The woman is so beautiful that

the young man is often swayed by her beauty away from family, home,

community. If the young man is so entranced as to not notice the young

woman's feet—which in the case of Deer Woman are hooves—then he falls

under her spell and stays with her forever, wasting away into

depression, despair, prostitution, and ultimately, death.

"The Deer Woman spirit teaches us that marriage and family life

within the community are important and these relationships cannot be

entered into lightly. Her tales are morality narratives: she teaches us

that the misuse of sexual power is a transgression that will end in

madness and death. The only way to save oneself from the magic of Deer

Woman is to look to her feet, see her hooves, and recognize her for what

she is. To know the story and act appropriately is to save oneself from a

lifetime lived in pain and sorrow; to ignore the story is to continue

in the death dance with Deer Woman. Deer Woman instructs us that sexual

attraction does not a proper marriage make; it is the societal and

cultural responsibility of each tribal member to choose a mate

wisely—therefore ensuring tribal survival into the next generation. Both

the Karuk stories and the Southeastern stories illustrate this cultural

responsibility."

Navajo author and musician Joy Harjo finds Deer Woman in a bar late on a winter's night in her haunting prose-poem "Deer Dancer":

"She was the myth slipped down through dreamtime. The promise of feast we

all knew was coming. The deer who crossed through knots of a curse to find

us. She was no slouch, and neither were we, watching.

"The music ended. And so does the story. I wasn't there. But I imagined her

like this, not a stained red dress with tape on her heels but the deer who

entered our dream in white dawn, breathed mist into pine trees, her fawn a

blessing of meat, the ancestors who never left."

Chickasaw writer Linda Hogan addresses the secret desire so many of us have to run away with the deer ourselves in this passage from her beautiful poem "Deer Dance":

That night, after everything human was resolved,

a young man, the chosen, became the deer.

In the white skin of its ancestors,

wearing the head of the deer

above the human head

with flowers in his antlers, he danced,

beautiful and tireless, until he was more than human,

until he, too, was deer.

Of all those who were transformed into animals,

the travelers Circe turned into pigs,

the woman who became the bear,

the girl who always remained the child of wolves,

none of them wanted to go back

to being human. And I would do it, too, leave off being human

and become what it was that slept outside my door last night,

rested in my sleep.

"Convince the deer you are one of

them," advises Shauna Osborne, a Comanche/German mestiza writer from New Mexico. "Dance with them and they will show you the way. Pay strict attention to

the leg positions and neck angles—that’s where the heart of their dance lies. Deer

have this natural grace, this presence, on the dance floor that just can't be

beat. Once you find it, you’ll know. Do some research: Ginger Rogers had a

definite tinge of deer blood in her and my mother always swore that Travolta

had to be part deer. "How else could he glide through the air like

that?" she would demand. However,

the best contemporary example of a deer dancer has to be, without doubt,

Christopher Walken. He defies the laws of physics with such style and does it

with a nonchalant matter-of-factness which all deer dancers should try to

emulate. Treat his work as it should be treated—a sacred text of the Deer

Dancers. Roll with this or roll with that—just make sure your feet never quite

touch the ground. However, you must remember: when the song ends, the story

does too."

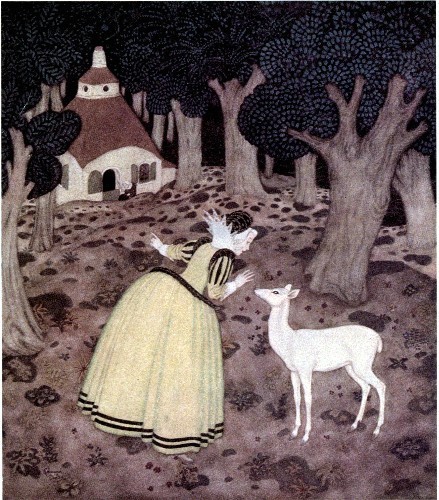

The enchanted deer imagery above is: Winged deer in a pattern from a medieval French tapestry; "Diana (Artemis) and Acteon" by Domenico Veneziano (1410-1461); "The Mystic Wood" and "The Lady Clare" by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917); "Running Deer" by Alex Herbert, "Brother and Sister" (the cover image for an edition of Grimms Fairy Tales) by John Barton Gruelle (1880-1938); “Brother and Sister” by Carl Offterdinger (1829-1889); "Perched" by Kelly Louise Judd; "Brother and Sister" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953); "The White Deer" by Adrienne Ségur (1901-1981); "All by Grandmothers" by Kristin Vestgard; an old photograph (provenance unknown); "The Deer Woman" by Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997); "Easter Procession, Rancho Camargo, Sonora" (from the "Miners & Mayos" photography series) by David Bacon; "Deer Dancer" portrait by Kyle Bowman; "The Deer Man" and "The Deer Woman" by Wendy Froud; "Deer Maiden" bronze by Erich Schmidt-Kestner (1887-1941); "Born" by Kiki Smith; three deer sketches by Daniel Egnéus; and a deer photograph (provenance unknown).

July 7, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's music comes from the smokey-voiced American singer/songwriter Aoife O'Donovan, whose wonderful new solo album, Fossils, has just been released. (We listened to her collaborations with Chris Thile, Yo Yo Ma, and Crooked Still on a previous Monday morning.)

Above,"Red & White & Blue & Gold," a song from the new album, performed for a recent Folk Alley Session.

Below, "The Beekeeper," performed at the Loveless Cafe for Music City Roots in late May. (O'Donovan has been glammed up a bit in recent videos and concerts, which I know is de rigueur in the music industry these days, but I have to admit I miss the smart-girl glasses.)

Above, the 2010 video for"Half of What We Know," with her terrific roots band, Crooked Still (which she still plays with when she's not involved with other projects). They're based in Boston.

Last, O'Donovan sings "Tears of Healing/After the Rain" (by Mark Simos) with the musical group Childsplay.

If you'd like a little more O'Donvan this morning, try these two: her beautiful bluegrass-inflected song "Lay My Burden Down" (which has been covered by Alison Krauss and others), and her lovely, gentle rendition of the Richard Thompson classic, Vincent Black Lightening."

July 4, 2013

Into the Woods, 17: The Wisdom of Mountains

"In East Asia, 'mountains' are often synonymous with wilderness," writes American poet and mythographer Gary Snyder. "The agrarian states have long since drained, irrigated, and terraced the lowlands. Forests and wild habitats start at the very place that farming stops. The lowlands, with their villages, markets, cities, palaces, and wineshops, are thought of as the place of greed, lust, competition, commerce, and intoxication -- the 'dusty world.' Those who would flee such a world and seek purity find caves or build hermitages in the hills -- and take up the practices which will bring realization or at least a long healthy life. These hermitages in time become the centers of temple complexes and ultimately religious sects. Dōgen says:

" 'Many rulers have visited mountains to pay homage to wise people or ask for instructions from great sages....At such time these rulers treat the sages as teachers, disregarding the protocol of the usual world. The imperial power has no authority over the wise people in the mountains.' "

"So 'mountains' are not only spiritually deepening," Snyder continues, "but also (it is hoped) independent of the control of the central government. Joining the hermits and priests in the hills are people fleeing jail, taxes, or conscription. (Deeper into the ranges of southwest China are the surviving hill tribes who worship dogs and tigers and have much equality between the sexes, but that belongs to another story.) Mountains (or wilderness) have served as a haven of spiritual and political freedom all over.

"Mountains also have mythic associations of verticality, spirit, height, transcendence, hardness, resistance, and masculinity. For the Chinese they are exemplars of the 'yang': dry, hard, male, and bright. Waters are feminine: wet, soft, dark 'yin' with associations of fluid-but-strong, seeking (and carving) the lowest, soulful, life-giving, shape-shifting. Folk (and Vajrayana) Buddhist iconography personifies 'mountains and waters' in the rupas -- 'images of Fudo Myo-o (Immovable Wisdom King) and Kannon Bosatsu (The Bodhisattva Who Watches the Waves)."

"Fudo is almost comically ferocious-looking," says Snyder, "with a blind eye and a fang, seated or standing on a slab of rock and enveloped in flames. He is known as an ally of mountain ascetics. Kannon (Kuan-yin, Avalokitesvara) gracefully leans forward with her lotus and vase of water, a figure of compassion. The two are seen as buddha-work partners: ascetic disciplin and relentless spirituality balanced by compassionate tolerance and detached forgiveness. Mountains and Waters are a dyad that together make wholeness possible: wisdom and compassion are the two components of realization."

"Mountains seem to answer an increasing imaginative need in the West," reflects English naturalist Robert Macfarlane. "More and more people are discovering a desire for them, and a powerful

solace in them. At bottom, mountains, like all wildernesses, challenge

our complacent conviction - so easy to lapse into - that the world has

been made for humans by humans. Most of us exist for most of the time in

worlds which are humanly arranged, themed and controlled. One forgets

that there are environments which do not respond to the flick of a

switch or the twist of a dial, and which have their own rhythms and

orders of existence. Mountains correct this amnesia. By speaking of

greater forces than we can possibly invoke, and by confronting us with

greater spans of time than we can possibly envisage, mountains refute

our excessive trust in the man-made. They pose profound questions about

our durability and the importance of our schemes. They induce, I

suppose, a modesty in us.”

French poet (and ardent mountain climber) René Daumal noted that you cannot stay on a mountain summit forever; you have to come down

again. "So why bother in the first place?" he asked.

"Just this: What is above knows what is below, but what is below

does not know what is above. One climbs, one sees. One

descends, one sees no longer, but one has seen. There is an art

of conducting oneself in the lower regions by the memory of what

one saw higher up. When one can no longer see, one can at least

still know."

Mountains are the homes of the gods, the winds, and a wide variety of

nature spirits both malevolent and benign in many mythic traditions:

fairies haunt isolated mountain peaks in numerous stories from Scotland

and Wales, for example, and the mountains of northern Europe are riddled

with tunnels and caves belong to trolls and dwarves (the latter being

experts in mining and metal-work). In hero myths the world over, a

journey to the mountains is one of great trials and terrors that lead,

if one is steadfast, to personal or spiritual transformation...a journey

that is echoed in modern fantasy tales from Lost Horizons to The Lord of the Rings.

Fairies, come take me out of this dull world,

For I would ride with you upon the wind,

Run on the top of the dishevelled tide,

And dance upon the mountains like a flame.

- William Butler Yeats (from his play Land of Heart's Desire)

Those of us who live beneath this cold mountain

have heard its voice in our dreams

lift us out of warm rooms and soft beds, up

onto it shoulders where we are light as leaves.

- Amy Barratt (from her poem "The Mountain" )

"The root word in 'religion' means 'to bind,' writes naturalist Gretel Ehrlich, based in the vast mountain landscape of Wyoming. "It is no mere co-incidence

that our feelings about a place take on spiritual dimensions. An old rancher told me once that he thought the lines in his hand had come directly from the earth, that the land had carved them there after so many years of work. We are bound to place. The Japanese poet and priest Ikkyu referred to any passionate connection as 'red threads.' Perhaps it is red thread that holds me here in Wyoming.

"The ways in which we come to know a landscape are preliterate. 'A sense of place' implies a sensory knowledge. It mounts up in our minds: empires of smells and sounds, textures and sights held fast by memory, flooding back again and again in such urgent, pungent ways as to let us re-enter those places. A river slits its neck for us; the eerie sound a sandhill crane makes comes into our throat as song; in the mountain fastness of granite cracks, a pine tree grows; and we humans dive backward and forward in time, beginning seventy million years ago, when mountains came into being. We rise with the landforms. We feel the upper altitudes of thin air, sharp stings of snow and ultraviolet on our flesh....

"All during our lives, in any and every place we live or visit, the sacramental landscape unrolls before us. It is our text. It is public and private, social and wild, political and aesthetic. To see -- that is, to discover -- is not an act of interpretation, of transfixing with preconceived ideas what is before us; rather, it is an act of surrender."

Let's end today with words from the great John Muir (1838-1914), one of America's earliest advocates for the protection of wilderness:

"Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people," he said, "are beginning

to find out going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a

necessity.”

Over one hundred years later, this is truer than ever.

The mountainous art above comes from China, and from just down the road here in Devon: "Three Visits to the Thatched Cottage" by Dai Jin/Tai Chin (1388-1462), "Poet on a Mountaintop" by Shen Zhou (1427-1509), "Lofty Mount Lu" by Shen Zho, five paintings and one drawing for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings by Alan Lee, and "Friends and Spring Mountain" by Tang Yin (1470-1523).

The passage by Gary Snyder comes from his brilliant book of essays, The Practice of the Wild, highly recommended. Robert Macfarlane is quoted from Mountains of the Mind -- but if you haven't read him before, I recommend starting with The Wild Places and The Old Ways. The quote by René Daumal comes from his unfinished novel Mt. Analogue. "The Mountain," by Canadian poet Amy Barratt, was published in The Antigonish Review, Autumn 1994 issue. The Gretel Ehrlich quote comes from "Landscape, " an essay published in The Legancy of Light, edited by Constance Sullivan. Ehrlich's own books, such as The Solace of Open Spaces and In the Empire of Ice, are all very fine.

July 3, 2013

The passage of time

Above, Tilly in our back courtyard, autumn 2009...when she still had her unfortunate penchant for munching on the flowers at the base of The Lady of Bumblehill, our statue by Wendy Froud.

Tilly and the Lady, summer 2013. Both have settled into Bumblehill nicely in the intervening years.

"I confess I do not believe in time," wrote Vladimir Nabokov. "I like to fold my magic carpet,

after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon

another. Let visitors trip. And the highest enjoyment of timelessness -- in

a landscape selected at random -- is when I stand among rare butterflies

and their food plants. This is ecstasy, and behind the ecstasy is

something else, which is hard to explain. It is like a momentary vacuum

into which rushes all that I love. A sense of oneness with sun and

stone. A thrill of gratitude to whom it may concern -- to the contrapuntal

genius of human fate or to tender ghosts humoring a lucky mortal.”

Below, the courtyard when we first moved in -- after we'd pulled down a

moldy old shed, covered in black tar paper, that took up most of its

space.

And next, the same view as it looks today, table spread for lunch with a William Morris cloth.

“Every instant of our lives," said André Gide, "is essentially irreplaceable: you must know this in order to concentrate on life.”

Every moment. Oh yes, and especially these...

...the quiet, simple, forgettable moments of salad and sunshine and convivial conversation...

... of foxgloves blooming and pansies unmolested, and a lazy black dog on the garden path.

“Pull up a chair. Take a taste. Come join us. Life is so endlessly delicious,” writes the food critic Ruth Reichl.

"Flowers are too," murmurs Tilly, falling fast asleep, tasting violets in her dreams.

Calling on the community....

Here are two Kickstarter campaigns worthy of support from the Mythic Arts community:

First, Gary A. Lippincott is the raising funds to publish a book of his beautiful, magical art. With only three days left, he's more than reached his goal, but every extra dollar allows him to expand the range of the book, which is a good thing indeed. Go here to learn more.

Second, Chagford's own Toby Froud (now living with his lovely wife and son in Portland, Oregon, where he works in the film industry) is raising funds for a live-action short fantasy film, Lessons Learned, featuring a cast of his magical puppets. He's raised half of his goal (in only two days!), with 28 days still to go for the rest. Go here to learn more.

July 2, 2013

Into the Woods, 16: By the Light of the Moon and Stars

"The world rests in the night. Trees, mountains, fields, and faces are

released from the prison of shape and the burden of exposure. Each thing

creeps back into its own nature within the shelter of the dark.

Darkness is the ancient womb. Night-time is womb-time. Our souls come

out to play."

- John O'Donohue (Anam Cara)

“Sometimes, when you're deep in the countryside, you meet three girls,

walking along the hill tracks in the dusk, spinning. They each have a

spindle, and on to these they are spinning their wool, milk-white, like

the moonlight. In fact, it is the moonlight, the moon itself, which is

why they don't carry a distaff. They're not Fates, or anything terrible;

they don't affect the lives of men; all they have to do is to see that

the world gets its hours of darkness, and they do this by spinning the

moon down out of the sky. Night after night, you can see the moon

getting less and less, the ball of light waning, while it grown on the

spindles of the maidens. Then, at length, the moon is gone, and the

world has darkness, and rest." - Mary Stewart (The Moonspinners)

“Night falls. Or has fallen. Why is it that night falls, instead of

rising, like the dawn? Yet if you look east, at sunset, you can see

night rising, not falling; darkness lifting into the sky, up from the

horizon, like a black sun behind cloud cover. Like smoke from an unseen

fire, a line of fire just below the horizon, brushfire or a burning

city. Maybe night falls because it’s heavy, a thick curtain pulled up

over the eyes. A wool blanket.” - Margaret Atwood (A Handmaid's Tale)

“Anything seems possible at night when the rest of the world has gone to sleep.”

- David Almond (My Name is Mina)

"Night does not show things, it suggests them. It disturbes and surprises

us with its strangeness. It liberates forces within us which are

dominated by our reason during the daytime.” - Brassaï

"Our fantastic civilization has fallen out of touch with many aspects of

nature, and with none more completely than with night. Primitive folk,

gathered at a cave mouth round a fire, do not fear night; they fear,

rather, the energies and creatures to whom night gives power; we of the

age of the machines, having delivered ourselves of nocturnal enemies,

now have a dislike of night itself. With lights and ever more lights, we

drive the holiness and beauty of night back to the forests and the sea;

the little villages, the crossroads even, will have none of it. Are

modern folk, perhaps, afraid of night? Do they fear that vast serenity,

the mystery of infinite space, the austerity of stars? Having made

themselves at home in a civilization obsessed with power, which explains

its whole world in terms of energy, do they fear at night for their

dull acquiescence and the pattern of their beliefs? Be the answer what

it will, today's civilization is full of people who have not the

slightest notion of the character or the poetry of night, who have never

even seen night. Yet to live thus, to know only artificial night, is as

absurd and evil as to know only artificial day.” - Henry Beston (The Outermost House)

Look, as the day slows towards the space

that draws it into dusk: rising became

upstanding, standing a laying down, and then

that which accepts its lying blurs to darkness.

Mountains rest, outgloried be the stars -

but even there, time’s transition glimmers.

Ah, nightly refuged in my wild heart,

roofless, the imperishable lingers.

- Rainer Maria Rilke (Uncollected Poems: 1912-1922, translation by Susan Ranson & Marielle Sutherland)

'This is the ending. Now not day only shall be beloved, but night too

shall be beautiful and blessed and all its fear pass away.” - J.R.R. Tolkien (The Return of the King)

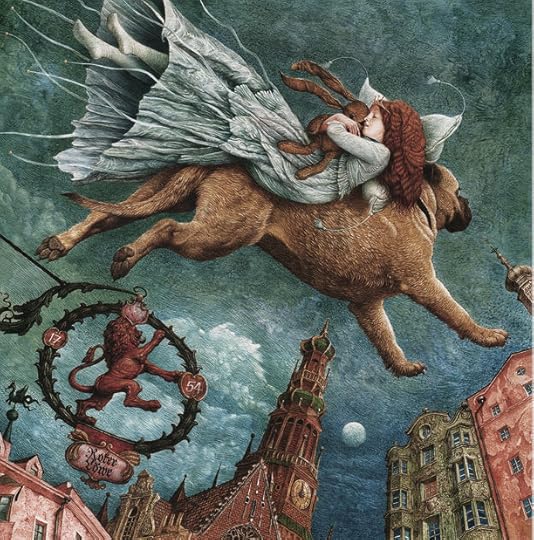

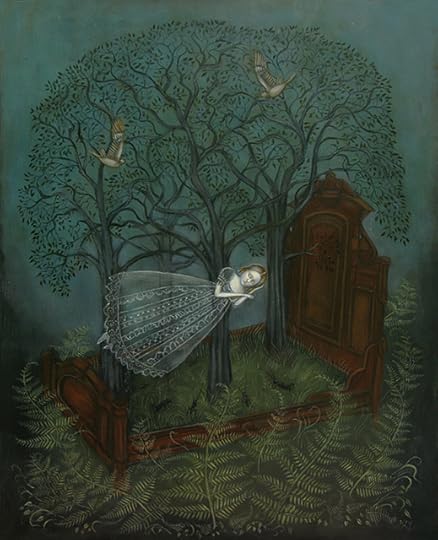

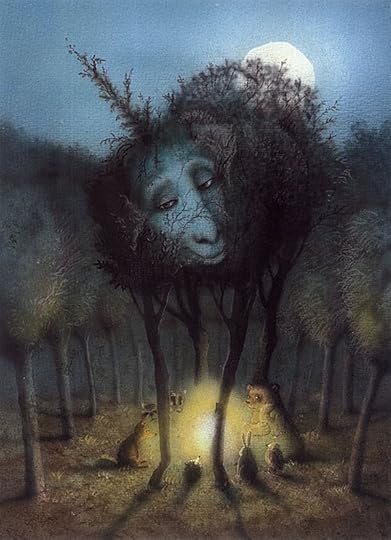

The illustrations above are : "Trolls" by John Bauer (1882-1918), "Celestial Pablum" by Remedios Varo (1908-1963),

"Capturing the Moon: by Jeanie Tomanek, Descent: The Arabian Nights by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), a drawing from the "Inner Seasons" series by Virginia Lee, "A Midsummer Night's Dream" by Arthur Rackham (1887-1969), "Nature Spirits and the Angel" by Sulamith

Wülfing (1901-1989), "Kip the Enchanted Cat" by Adrienne

Ségur (1901-1981), "The Tin Soldier: The Dog Carries the Princess on His Back" by Vladislav Erko, "Forest Sleep" by Kelly Louise Judd, "A Midsummer Night's Dream: Oberon and Titania" by

Arthur Rackham (1887-1969), "The Fairy Procession" by Charles Vess, "Marianna and the Whippets" by David Wyatt,

"Crossing the River" by Catherine Hyde, "The Moonrakers" by Karen Davis (of the lovely Moonlight and Hares blog), "The Wind and the Willows" by Inga Moore, and "The Legendary Unicorn" by Julia Gukova.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 707 followers