Terri Windling's Blog, page 189

June 11, 2013

Into the Woods, 9: Wild Children

Today I'm on the trail of the Wild Children of myth, lore, and fantasy: children lost in the forest, abandoned, stolen, reared by wild animals, and those for whom wilderness is their natural element and home.

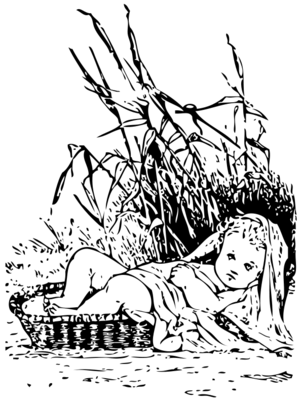

Tales of babies left in the woods (and other forms of wilderness) can found in the myths, legends, and sacred texts of cultures all around the globe. The infant is usually of noble birth, abandoned and left to certain death in order to thwart a prophesy -- but  fate intervenes, the child survives and is raised by wild animals, or by humans who live on the margin of wild: shepherds, woodsmen, gamekeepers, and the like. When the child grows up, his or her true identity is revealed and the prophesy is fulfilled. In Persian legends surrounding Cyrus the Great, for example, it is prophesized at his birth that he will grow up to take the crown of his grandfather, the King of Media. The king orders the baby killed and Cyrus is left on a wild mountainside, where he's rescued either by the royal herdsman or a bandit (depending on the version of the tale) and raised in safety. He grows up, learns his true parentage, and not only captures the Median throne but goes on to conquer most of central and southeast Asia. In Assyrian myth, a fish-goddess falls in love with a beautiful young man, gives birth to a half-mortal daughter, abandons the child in the wilderness, and then kills herself in shame. The baby is fed by doves and survives to be found and raised by a royal shepherd...and grows up to become Semiramis, the great Warrior Queen of Assyria. In Greek myth, Paris, the son of King Priam, is born under a prophesy that he will one day cause the downfall of Troy. The baby is left on the side of Mount Ida, but he's suckled by a bear and manages to live -- growing up to fall in love with Helen of Troy and spark the Trojan War.

fate intervenes, the child survives and is raised by wild animals, or by humans who live on the margin of wild: shepherds, woodsmen, gamekeepers, and the like. When the child grows up, his or her true identity is revealed and the prophesy is fulfilled. In Persian legends surrounding Cyrus the Great, for example, it is prophesized at his birth that he will grow up to take the crown of his grandfather, the King of Media. The king orders the baby killed and Cyrus is left on a wild mountainside, where he's rescued either by the royal herdsman or a bandit (depending on the version of the tale) and raised in safety. He grows up, learns his true parentage, and not only captures the Median throne but goes on to conquer most of central and southeast Asia. In Assyrian myth, a fish-goddess falls in love with a beautiful young man, gives birth to a half-mortal daughter, abandons the child in the wilderness, and then kills herself in shame. The baby is fed by doves and survives to be found and raised by a royal shepherd...and grows up to become Semiramis, the great Warrior Queen of Assyria. In Greek myth, Paris, the son of King Priam, is born under a prophesy that he will one day cause the downfall of Troy. The baby is left on the side of Mount Ida, but he's suckled by a bear and manages to live -- growing up to fall in love with Helen of Troy and spark the Trojan War.

From Roman myth comes one of the most famous babes-in-the-wood stories of all, the legend of Remus and Romulus. Numitor, the good King of Alba Long, is overthrown by Amulius, his wicked brother, and his daughter is forced to become a Vestal Virgin in order to end his line. Though locked in a temple, the girl becomes pregnant (with the help of

Mars, the god of war) and gives birth to a beautiful pair of sons: Remus and Romulus. Amulius has the twins exposed on the banks of the Tiber, expecting them to perish; instead,  they are suckled and fed by a wolf and a woodpecker, and survive in the woods. Adopted by a shepherd and his wife, they grow up into noble, courageous

they are suckled and fed by a wolf and a woodpecker, and survive in the woods. Adopted by a shepherd and his wife, they grow up into noble, courageous

young men and discover their true heritage — whereupon they overthrow

their great-uncle, restore their grandfather to his throne, and,

just for good measure, go on to found the city of Rome.

In Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children, Michael Newton

delves into the mythic symbolism inherent in the moment when abandoned

children are saved by birds or animals. "Restorations and

substitutions are at the very heart of the Romulus and Remus story," he

writes; "brothers take the rightful place of others, foster parents

bring up other people's children,

the god Mars stands in for a human suitor. Yet the crucial

substitution occurs when the she-wolf saves the lost children. In that

moment, when the infants' lips

close upon the she-wolf's teats, a transgressive mercy removes the

harmful influence of a murderous culture. The moment is a second birth:

where death is expected, succor is given, and the children are

miraculously born into the order of nature. Nature's mercy admonishes

humanity's unnatural cruelty: only a miracle of kindness can restore the

imbalance created by human iniquity."

In myth, when we're presented with children orphaned, abandoned, or raised by

animals, it's generally a sign that their true parentage is a

remarkable one and they'll grow up to be great leaders, warriors, seers,

magicians, or shamans. As they grow, their beauty, or physical prowess

or magical abilities betray a lineage that cannot be hidden by their

humble upbringing. (Rarely do we encounter a mythic hero whose origins are

truly low; at least one parent must be revealed as noble, supernatural,

or divine.)

After a birth trauma and a miraculous survival always comes a span

of time symbolically described as "exile in the wilderness," where they

hone their skills, test their mettle, and gather their armies, their

allies, or their magic, before returning (as they always do) to the

world that is their birthright.

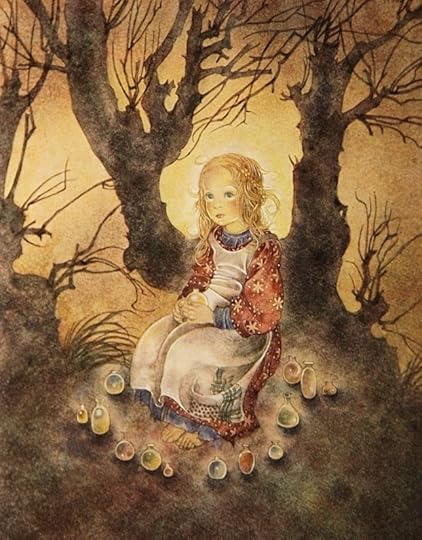

When we turn to folk tales and fairy tales, however, although we also find stories of

children abandoned in the wild and befriended by animals, the

tone and intent of such tales is markedly different. Here, we're not concerned with the affairs of the gods

or with heroes who conquer continents -- for folk tales in the Western tradition, unlike myths and hero epics, were passed

through the centuries primarily by storytellers of lower classes (usually women), and tended to be focused on themes more relevant to ordinary people. Abandoned children in fairy tales (like Hansel and Gretel, Little Thumbling, or the broommaker's twins in The Two Brothers) aren't destined for greatness or infamy; they are

exactly what they appear to be: the children of cruel or feckless

parents. Such parents exist, they have always existed, and fairy tales

did not gloss over these dark facts of life. Indeed, they

confronted them squarely. The heroism of such children lies not in the recovery of a noble lineage but in

the ability to survive and transform their fate -- and to outwit those

who would do them harm without losing their lives, their souls, or their

humanity in the process.

Children also journey to the forest of their own accord, but usually in response to the actions of adults: they enter the woods at a parent's behest (Little Red Riding Hood), or because they're not truly wanted at home (Hans My Hedgehog), or in order to flee a wicked parent, step-parent, or guardian (Seven Swans, Snow White and Brother & Sister). Disruption of a safe, secure home life often comes in the form a parent's remarriage: the child's mother has died and a heartless, jealous step-mother has taken her place. The evil step-mother is so common in fairy tales that she has become

an iconic figure (to the bane of real step-mothers everywhere), and her

history in the fairy tale canon is an interesting one. In some tales,

she didn't originally exist. The murderous queen of Snow White, for example, was the girl's own mother in the oldest versions of the story (the Brothers Grimm changed her into a step-parent in the 19th century) -- whereas other stories, such as Cinderella and The Juniper Tree, have featured second wives since their earliest known tellings.

Some scholars who view fairy tales in psychological terms (most notably Bruno Bettelheim in The Uses of Enchantment)

Some scholars who view fairy tales in psychological terms (most notably Bruno Bettelheim in The Uses of Enchantment)

believe that the "good mother" and "bad step-mother" symbolize two

sides of a child's own mother: the part they love and the part they

hate. Casting the "bad mother" as a separate figure, they say, allows

the child to more safely identify such socially unacceptable feelings.

While this may be true, it ignores the fact that fairy tales were

not originally stories specially intended for children. And, as Marina

Warner points out (in From the Beast to the Blonde), this "leeches the history out of fairy tales. Fairy

or wonder tales, however farfetched the incidents they include, or

fantastic the enchantments they concoct, take on the color of the actual

circumstance in which they were or are told. While certain structural

elements remain, variant versions of the same story often reveal the

particular conditions of the society

in which it is told and retold in this form. The absent mother can

be read as literally that: a feature of the family before our modern

era, when death in childbirth was the most common cause of female

mortality, and surviving orphans would find themselves brought up by

their mother's successor."

We rarely find step-fathers in fairy tales, wicked or otherwise, but

the fathers themselves can be treacherous. In stories like Donkeyskin, Allerleirauh, or The Handless Maiden, it is a cowardly, cruel, or incestuous father who forces his daughter to flee to the wild. Even those fathers portrayed more sympathetically as the dupes of their black-hearted wives are still somewhat suspect: they are happy at the story's end to have their children return unscathed, but are curiously powerless or unwilling to protect them in the first place. Though the father is largely absent from tales such as Cinderella, The Seven Swans, and Snow White, the shadow he casts over them is a large one. He is, as Angela Carter has pointed out, "the unmoved mover, the unseen organizing principle. Without the absent

father there would have been no story because there would have been no

conflict."

Family upheaval has another function in these tales, beyond reflecting real issues encountered in life: it propels young heroes out of their homes, away from all that is safe and familiar; it forces them onto the uknown road to the dark of the forest. It's a road that will lead, after certain

tests and trials, to personal and worldly transformation,

pushing the hero past childhood and pointing the way to a re-balanced life -- symbolized by new prosperity, or a family home that has been restored, or (for older youths) a wedding feast at the end of the tale. These young people are "wild" only for a time: it's a liminal state, a rite-of-passage that moves the hero from one distinct phase of life to another. The forest, with all its wonders and terrors, is not the final destination. It is a place to hide, to be tested, to mature. To grow in strength, wisdom, and/or power. And to gain the tools needed to return to the human world and repair what's been broken...or build anew.

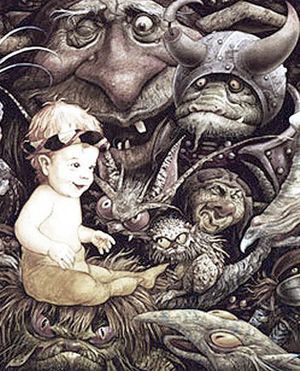

In one set of folk tales, however, children who disappear into the woods do not often return: the "changeling" stories of babies (and older children) stolen by faeries, goblins, and trolls. Why, we might ask, are the denizens of Faerie so interested in stealing the offspring of mortals? Some faery lore suggests that the children are

destined for lives as servants or slaves of the Faerie court; or that they are kept, in the manner of

pets, for the amusement of their faery masters. Other stories and ballads (Tam Lin, for example) speak of a darker purpose: that the faeries

must pay a tithe of blood to the Devil every seven years,

and prefer to pay with mortal blood rather than blood of their own.

In other traditions, however, it's simply the beauty of the children that

attracts the faeries, who are also known to kidnap pretty young men and women, artists, poets, and

musicians.

The ability of faeries to procreate is a debatable issue in faery lore. Some stories maintain that the faeries do procreate, though

The ability of faeries to procreate is a debatable issue in faery lore. Some stories maintain that the faeries do procreate, though

not as often as humans. By occasionally interbreeding with mortals and

claiming mortal babes as their own,

they bring new blood into the Faerie Realm and keep their bloodlines

strong. Other tales suggest that they cannot breed, or do so with such

rarity that jealousy of human fertility is the motive behind

child-theft.

Some stolen children, the tales tell us, will spend their

whole lives in the Faerie Realm, and may even find happiness there, losing all

desire for the lands of men. Other tales tell us that human children

cannot thrive in the otherworld, and eventually sicken and die for want

of mortal food and drink. Some faeries maintain their interest in child

captives only during their infancy, tossing the children out of the Faerie Realm when they show signs of age.

Such children, restored to the human world, are not always happy

among their own kind, and spend their mortal lives pining for a way to

return to Faerie.

Another type of story that comes from the deep, dark forest is the Feral Child tale, found in the shadow realm that lies between legend and fact. There have been a number of cases throughout history of young

children discovered living in the wild, a few of which have been documented

to a greater or lesser degree. Generally, these seem to be children who

have been abandoned or fled abusive homes, often at such a young

age that they've ceased to remember any other way of life. Attempts to "civilize"

these children, to teach them language,

and to curb their animal-like behaviors, are rarely entirely

successful -- which leads to all sorts of questions about what it is that

shapes human culturalization as we know it.

One of the most famous of these children was Victor, the Wild Boy

of Avignon, discovered on a mountainside in France in the early 19th

century. His teacher, Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard, wrote an extraordinary

account of his six years with the boy -- a document which inspired François Truffaut's film The Wild Child, and Mordicai Gerstein's wonderful novel The Wild Boy. In an essay for The Horn Book, Gerstein wrote: "Itard's reports not only provide the best

documentation

we have of a feral child, but also one of the most thoughtful,

beautifully written, and moving accounts of a teacher pupil

relationship, which has as its object nothing less than learning to be a

human being (or at least what Itard, as a man of his time, thought a

human being to be).... Itard's ambition to have Victor speak

ultimately failed, but even if he had succeeded, he could never know

Victor better or be more truly, deeply engaged with him than those

evenings, early on, when they sat together as Victor loved to,

with the boy's face buried in the man's hands. But the more Itard

taught Victor, the more civilized he became, the more the distance

between them grew." (You'll find Gerstein's full essay here; scroll to the bottom of the page.)

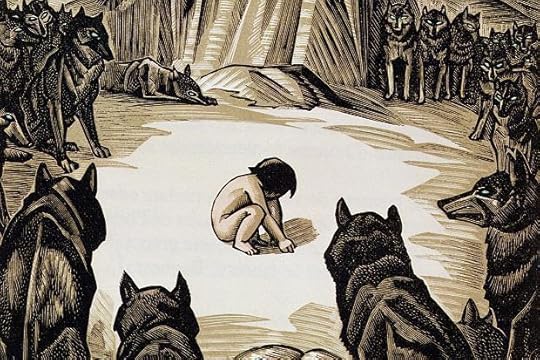

In India in the 1920s two small girls were discovered living in the

wild among a pack of wolves. They were captured (their "wolf mother"

shot) and taken into an orphanage run by a missionary, Reverend Joseph

Singh. Singh attempted to teach the girls to speak, walk upright, and

behave like humans, not as wolves — with limited success. His diaries make for fascinating (and horrifying) reading. Several works of fiction were inspired by this story, but the ones I particularly recommend are Children of the Wolf, a poignant children's novel by Jane Yolen, and "St. Lucy's Home for Girls Raised by Wolves," a wonderful short story by Karen Russell (published in her collection of the same title). Also, Second Nature by Alice Hoffman is an excellent contemporary novel on the Feral Child theme.

More recently, in 1996, an urban Feral Child was discovered

living with a pack of dogs on the streets of Moscow. He resisted capture

until the police finally separated the boy from his pack. "He had been

living on the street for two years," writes Michael Newton. "Yet, as he

had spent four years with a human family [before this], he could talk

perfectly well. After a brief spell in a Reutov children's shelter, Ivan

started school. He appears to be just like any other Moscow child. Yet

it is said that, at night, he still dreams of dogs."

When we read about such things as adults and parents, the thought

of a child with no family but wolves or dogs is a deeply disturbing

one. . .but when we read from a child's point of view, there is

something secretly thrilling about the idea of life lived among an

animal pack, or shedding the strictures of civilization to head into the

woods. In this, of course, lies the enduring appeal of stories like

Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book and Edgar Rice Burroughs's Tarzan of the Apes.

Explaining his youthful passion for such tales,

Mordecai Gerstein writes: "The heart of my fantasy was leaving the

human world for a kind of jungle Eden where all one needed was readily

available and that had, in Kipling's version, less hypocrisy, more

nobility. I liked best the idea of being protected from potential

enemies by powerful animal friends."

And here we begin to approach another aspect of Wild Child (and Orphaned Hero) tales

that makes them so alluring to many young readers: the idea that a parentless life in the wild might be a better, or a more exciting, one. For

children with difficult childhoods, the appeal of running away to the forest is obvious: such stories

provide escape, a vision of life beyond the confines of a troubled home.

But even children from healthy families need fictional escape from time to

time. In the wild, they can shed their usual roles

(the eldest daughter, middle son, the baby of the family, etc.)

and enter other realms in which they are solitary actors. Without

adults to guide them (or, contrarily, to restrict them), these young heroes

are thrown back, time and time again, on their own resources. They must

think, speak, act for themselves. They have no parental safety net

below. This can be a frightening prospect, but it is also a liberating

one — for although there's no one to catch them if they fall, there's no

one to scold them for it either.

J.M. Barrie addresses this theme, of course, in his much-loved children's fantasy Peter Pan -- which draws upon themes from Scottish changling legends, twisted into interesting new shapes. Barrie's Peter is human-born, not a faery, but he's lived in Never Land so long

that he's as much a faery as he is a boy: magical, capricious and

amoral. He's a complex

mixture of good and bad, with little understanding of the difference

between them -- both cruel and kind, thoughtless and generous, arrogant

and tender-hearted, bloodthirsty and sentimental. This dual nature makes Peter Pan a classic

trickster character (kin to Puck, Robin Goodfellow, and other

delightful but exasperating sprites of faery lore): both faery and child, mortal and

immortal, villain (when he lures children from their homes) and hero

(when he rescues them from pirates).

Peter's last name derives from the Greek god Pan, the son of the

Peter's last name derives from the Greek god Pan, the son of the

trickster god Hermes by a wood nymph of Arcadia. Pan is a creature of

the wilderness, associated with vitality, virility, and ceaseless

energy. Like Peter, the god Pan is a contradictory figure. He haunts

solitary mountains and groves, where he's quick to anger if he's

disturbed, but he also loves company, music, dancing, and riotous

celebrations. He is the leader of a woodland band of satyrs — but these

"Lost Boys" are a wilder crew than Peter's, famed for drunkenness,

licentiousness, and creating havoc (or "panic"). Pan himself is a

distinctly lusty god — and here the comparison must end, for Peter's

wildness has no sexual edge. Indeed, it's sex and the other mysteries of

adulthood that he's specifically determined to avoid. ("You mustn't

touch me. No one must ever touch me," Peter tells Wendy.)

Although Peter Pan makes a brief appearance in Barrie's 1902 novel The Little White Bird, his story as we know it now really began as a children's play, which debuted on the London stage in 1904. The playscript was subsequently published under the title Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up; and eventually Barrie novelized the story in the book Peter and Wendy. (It's a wonderful read in Barrie's original text, full of sharp black humor.) Peter and Wendy ends with a poignant scene that does not exist in the play: Peter comes back

to Wendy's window years later, and discovers she is all grown up. The

little girl in the nursery now is Wendy's own daughter, Jane. The girl

examines Peter with interest, and soon she's off to Never Land herself...where Wendy can no longer go, no matter how much she longs to

follow.

The fairy tale forest, like Never Land, is not a place we are meant to remain, lest, like Peter or the children stolen by faeries, we become something not quite human. Young heroes return triumphant from the woods (trials completed, curses broken, siblings saved, pockets stuffed with treasure), but the blunt fact is that they must return. In the old tales, there is no sadness in this, no lingering, backward glance to the forest; the stories end "happily ever after" with the children restored to the human world. In this sense, the wild depths of the wood represent the realm of childhood itself, and the final destination is an adulthood rich in love, prosperity, and joy. From Victorian times onward, however, a new note of regret creeps in at the end of the story. A theme that we find over and over again in Victorian fantasy literature is that magic and wonder are accessible only

to children, lost on the threshold of adulthood. From Lewis

Carroll’s "Alice" books to J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, these

writers grieved that their wise young heroes would one day grow up and leave the woods behind.

Of course, many of us never do leave the woods behind: we return through the pages of magical books and we return in actuality, treasuring our interactions with the wild world through all the years of our lives. But that part of the forest specific to childhood does not truly belong to us now -- and that's exactly as it should be. Each generation bequeaths it to the next. Our job as adults, as I see it, is to protect that enchanted place by preserving wilderness and stories both. Our job is to open the window at night and to watch from the shadows as Peter arrives; it's our children's turn to step over the sill. Our job is to teach them to navigate by the stars and to bless them on their way.

Barrie was wrong, by the way, for we adults have our owns forms of magic too, and the wild wood still welcomes us. But it's right, I think, that there should be a corner of it forever marked "Grown-ups, keep out!" Where children are heroes of their own stories, kings and queens of their own wild worlds.

The art above is: "The Miracle of Tears" by Sulamith Wulfing (Germany); "Moses in the Bulrushes," artist unknown; "Remus and Romulus," an Ertruscan bronze; "Wolf Mama" and "Starchild" by Susan Seddon-Boulet (England/Brazil/USA); "Hansel & Gretel" by Kay Nielsen (Denmark); "Little Red Cap" by Lisbeth Zwerger (Austria); "Snow White" by Trina Schart Hyman (USA); Donkeyskin by Anneclaire Macé (France); "Three Black Dogs" by Kelly Louise Judd (USA), "Baby Stolen by Gobins" by Maurice Sendak (USA); "Toby and the Goblins" by Brian Froud (UK); a still from the film "L'Enfant sauvage" by François Truffaut (France); "Tiger Girls by Fay Ku (Tawain/USA); a photograph from the "Ashes and Snow" series by Gregory Colbert (Canada); "Mowgli" by Edward Julius Detmold (UK); "Where the Wild Things Are" by Maurice Sendak (USA); "Peter Pan" by David Wyatt (UK); "Peter Pan" by Brian Froud (UK); "Peter Pan at the Window" by F.D. Beford (UK); an illustration by Robert Ingapen (Australia); and "Peter Pan" by Charles Buchel (Germany/England).

Parts of this post have been drawn from these articles: The Orphaned Hero, Changelings, Peter Pan.

June 9, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

For today's tunes we go into the woods of Finland, where musicians of the Forest Folk movement compose experimental music rooted in Finnish folk traditions, inspired by the sounds of the natural world.

First, if you're unfamiliar with Forest Folk, have a look at the ArtsWorld video above, which provides a short introduction to the music.

Below: "Painovoimaa, valoa" from Lau Nau (the stage name of Laura Naukkarinen), from her second albumn, Nukkuu (2008). Lau Nau is a leading figure in the development of Forest Folk (living and working in remote countryside on Kimito island), although she herself is wary of labels and describes her music as "ethnic tinged experimental folk." I recommend her first two albums as examples of Forest Folk, as her most recent album is more wideranging -- incorporating elements of pop, electronica, and dance music. It's interesting, but for me works best when she goes back to her folk roots and her love of "quiet sounds."

Above: "Rohkaisulaulu" by Islaja (the stage name of Merja Kokkonen), from her third album, Ulual Yyy (2007). Her most recent work is more electronic, so it's this early work that links Islaja to the Forest Folk movement.

Below: "Nainen Tarina" by Violeta Päivänkakkara, from her album Kuu (2012).

If you'd like to listen a little more of this atmospheric music this morning, go here. More information about Finnish experimental music can be found here.

June 7, 2013

Embracing it all...

...good days and bad, healthy days and sick ones, and the astonishing beauty of Devon in the spring. The best kind of medicine.

I'm dealing with some health issues at present and have found myself unable to keep up with posting this week. I hope to return to my regular blog schedule next week, which is when I'll continue the "Into the Wood" series. In the meantime, dear Readers, here is a gift of spring wildflowers for you, with love from me and Tilly....

"A human being is a part of the whole called-by-us universe, a part

limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and

feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion

of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us,

restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few

persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this

prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living

creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.” - Albert Einstein

"The heart of it all is mystery, and science is at best only the

peripheral trappings to that mystery -- a ragged barbed-wire fence through

which mystery travels, back and forth, unencumbered by anything so

frail as man's knowledge.” - Rick Bass

"We have lived by the assumption that what was good for us would be good for the world. And this has been based on the even flimsier assumption that we could know with any certainty what was good even for us. We have fulfilled the danger of this by making our personal pride and greed the standard of our behavior toward the world - to the incalculable disadvantage of the world and every living thing in it. And now, perhaps very close to too late, our great error has become clear. It is not only our own creativity - our own capacity for life - that is stifled by our arrogant assumption; the creation itself is stifled. We have been wrong. We must change our lives, so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption that what is good for the world will be good for us. And that requires that we make the effort to know the world and to learn what is good for it. We must learn to cooperate in its processes, and to yield to its limits. But even more important, we must learn to acknowledge that the creation is full of mystery; we will never entirely understand it. We must abandon arrogance and stand in awe. We must recover the sense of the majesty of creation, and the ability to be worshipful in its presence." - Wendell Berry

Amen.

June 4, 2013

A pony interlude

I'm a bit under the weather again today, and thus moving rather

slowly. I'll get the next "Into the Woods" post up just as soon as I

can. In the meantime: ponies on the hill behind our house, encountered

on a walk with Victoria, Theodora Goss, and Tilly on a Sunday afternoon.

June 2, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

We can hardly spend all this time in the woods without mentioning "Into the Woods," the Tony Award winning musical by Stephen Sondheim. And so here are a few songs from the show to kick off our last week of woodland posts...

Above: The play's opening, performed by the original Broadway cast.

Below: Tessa Burbridge and Clive Carter (as Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf in the original London cast) sing "Hello Little Girl."

Above: Robert Westenberg and Chuck Wagner (as Cinderella's Prince and Rapunzel's Prince in the original Broadway cast) singing "Agony Reprise" from Act II.

Below: Bernadette Peters sings the "Children Will Listen" (from the show's Finale) in concert at London's Royal Festival Hall.

May 31, 2013

Into the Wood, 8: Wild Men & Women

Merlin (pictured in the beautiful drawing by Alan Lee above) is a figure intimately connected with forests in Arthurian lore. After the disastrous Battle of Arderydd, Merlin goes mad and spends years as a

wild man in the woods, living a solitary, animal existance, before he emerges

into his full power as a magician and seer. His prophesies are contained

in Welsh poems said to be written by Myrddin himself from the 9th century onward;

many can be found in the Llyfr Du Caerfryddin and The Black Book of

Carmarthen. In the "Afallennau" and "Oineau" poems

(from The Black Book, translated by Meirion Pennar), Myrddin portrays

his life among apple trees in the forest of Celydonn: "Ten years and

two score have I been moving along through twenty bouts of madness with

wild ones in the wild; after not so dusty things and entertaining minstrels,

only lack does now keep me company. . . ." He despairs

that he, who once lay in women's arms, now lies alone on the cold, hard

ground, with only a wild piglet for company (a creature much revered by

the Celts).

This flight into wilderness is a common theme in shamanic initiation

from cultures around the globe. Through deprivation, an elemental existence,

and even madness, the shaman embarks on an inward journey; when he returns

to the world he is a changed man, aligned with the powers of nature, able

to converse with animals and to see into the hearts of men. Suibhne (or Sweeny) in Irish lore, for example, is a warrior cursed in battle and forced to flee to the

woods in the shape of a bird. Like Merlin, Suibhne goes stark raving mad during his long

exile — but when he emerges from the trial, he has mastery over

creatures of the forest. (For a gorgeous modern rendition of this tale, I recommend the book Sweeny's Flight,

an edition containing Seamus Heany's long poem based on the myth, along

with photographs of the Irish countryside by Rachel Giese.)

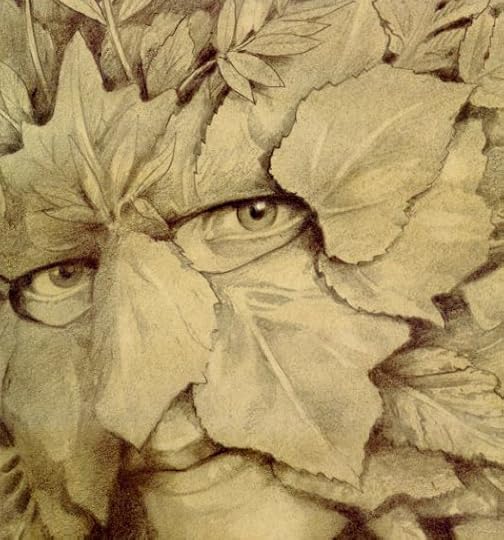

In epic romances, knights and other heroes go into the woods

to test their strength, courage, and faith; yet some of them also madness there, like the lovelorn Orlando in Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, one of the most popular poems of the Italian Renaissance. In Gawaine and the Green Knight, an Arthurian romance from the 14th century, a mysterious figures rides

out of the woods and into Camelot on New Year's eve. His clothes are green,

his horse is green, his face is green, even his jewels are green. He

carries a holly bush in one hand and an axe of green steel in the other.

The Green Knight issues a challenge that any knight in the court may strike

off his head — but in one year's time, his opponent must come to the forest

and submit to the same trial. Gawaine agrees to this terrible challenge

in order to save the honor of his king. He slices off the stranger's

head — but the knight merely picks it up and rides back to the forest,

bearing the head in the crook of his arm. One year later, Gawaine seeks

out the Green Knight in the Green Chapel in the woods. He survives the trial,

but is humbled by the green man and his beautiful wife through an act of

dishonesty.

In the French romance Valentine and Orson, the Empress of Constantinople is accused of adultery,

thrown out of her palace, and gives birth to twins in the wildwood. One

son (along with the mother) is rescued by a nobleman and raised at court,

while the other son, Orson, is stolen by a she-bear and raised in the wild.

The twins eventually meet, fight, then become bosom companions — all before

a magical oracle informs them of their kinship. The wild twin becomes civilized,

while retaining a primitive kind of strength — but when, at length, his

brother dies, he retires back into the forest.

Rather than a shamanic figure or a legendary hero, Orson is an example of the Wodehouse (or wild man) archtype: a primitive yet powerful

creature of the wilderness. Other examples can be found in tales ranging from Gilgamesh (in the figure

of Enkidu) to Tarzan of the Apes.

"The medieval imagination

was fascinated by the wild man," notes Robert Pogue Harrison (in his book Forests: The Shadow of Civilization), "but

the latter were by no means merely imaginary in status during the Middle

Ages. Such men (and women as well) would every now and then be discovered

in the forest — usually insane people who had taken to the woods. If hunters

happened upon a wild man, they would frequently try to capture him alive

and bring him back for people to marvel and wonder at."

Other famous

wild men of literature can be found in Chretien de Troyes's romance Yvain,

Jacob Wasserman's Casper Hauer (based on the real life incident of

a wild child found in the market square of Nuremberg in 1829), and in the

heart–stealing figure of Mowgli in Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book...but we'll talk more about "wild children" in another post.

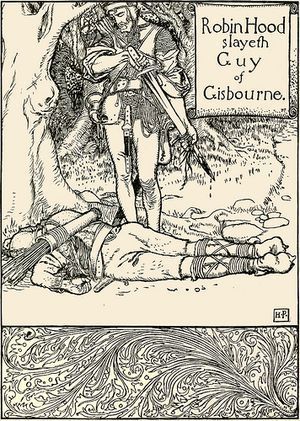

Mythic tales of forest outlaws feature a very different kind of wild

man, for in such stories (the Robin Hood cycle, for example) the hero

is generally a civilized man compelled, through an act of injustice, to

seek the wild life -- without every quite losing the trappings of civility in the process. These tales tend to take place in the merry Greenwood and not the fearsome Dark Forest: a place of shelter and refuge rather than a perilous world inhospitable to mortals.

"This British take on the forest evolved long before Shakespeare," writes poet and scholar Ruth Padel, "centered on the 'Rymes of Robyn Hood': eighty or so fourteenth–century

"This British take on the forest evolved long before Shakespeare," writes poet and scholar Ruth Padel, "centered on the 'Rymes of Robyn Hood': eighty or so fourteenth–century

ballads, full of James Bond fights, male camaraderie, adventures and

escapes, but also of passionate longing for a 'people's hero.' They date

from the time of the Peasant's Revolt, 1381. Sometimes Robin is a

disaffected Saxon lord who flees to the woods to become a mediaeval

Batman, dressing his men in green, robbing the rich to give to the poor.

Behind them is the star role of the forest in the politics of

disaffection which, kick–started by Norman rule, runs through English

history from the thirteenth century on. Outlaws, outside the law, took

to the forest, which was outside civilization. Yet the law itself was

unjust. 'They were not outlaws because they were murderers,' says T.H.

White of Robin's men in The Sword in the Stone. 'They were

Saxons who had revolted against the Norman conquest. The wild woods of

England were alive

with them.' Forest law claimed most forest for the king. 'The

king's deer' were protected by Norman barons and their officers, Sheriff

of Nottingham clones. It was death for a commoner to kill the deer —

yet they did, all the time. They plundered the forest for meat and

firewood; they cut down trees for grazing. Most Robin Hood films begin

with a peasant killing deer and Robin protecting him against a Norman

lord. Helping the poor, outlawed Robin stands for the hope of better law

against corrupt nobles, sheriffs, priests, injustice.

"And yet the forest is the base of British dreams for the better,

"And yet the forest is the base of British dreams for the better,

sadly absent, king. The sheriff has bad King John behind him while

Richard Lionheart is away. And the dream went on, tucked imaginatively

into key niches of British civil angst. Robert Louis Stevenson, in The Black Arrow,

imagines green–clad outlaws during the Wars of the Roses. They call

themselves 'John Amend–All' and punish wrongs done by the corrupt 'Knight of Tunstall.' 'O they must need to walk in wood that may not

walk in town,'

sings 'Hugh Lawless' as he strolls through Tunstall Forest. So the 'royal' British forest stands paradoxically for freedom for common men

as well as beasts. Freedom to use their bodily skills best. Robin's men

excel in 'woodcraft.' They appear and vanish soundlessly; they are a

meritocracy based not on birth but physique and the understanding of

nature. As one of Robin's men explains to T.H. White's Arthur, 'They'm

free places, the 'oods. . . .Let thee stand in 'em that thou be'st not

seen, and move in 'em that thou be'st not 'eard — they'm proper fine

places, the 'oods, for a free man of hands and heart.' "

Magical tales of hermits and woodland mystics form another category of the wild man (and woman) archetype. Christian legendry, for example, is filled with tales of saints living

in the wilderness on a diet of honey and acorns. This, again, is bolstered

by the actual experience of people in earlier times, when it was not uncommon

for folk marginalized by the community (mystics, herbalists or witches,

widows, eccentrics, and simpletons) to live in the wilds beyond the village,

by choice or necessity. An elderly neighbor of mine here in Devon remembered such

a figurefrom her youth — a harmless old soul who lived in a cave and was

believed to have prophetic powers.

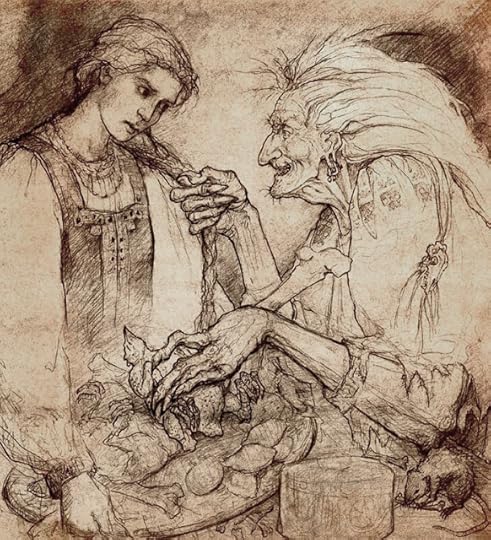

The wild woman archetype has come down through the centuries primarily in a scorned and diminished form: the wicked witch of the fairy tale forest. These women are invariably portrayed as ugly old crones (at least in the versions of the tales that we know best today): godless or pagan creatures aligned with nature, not civilization; evil, or at least amoral; knowledgeable, and therefore dangerous. Their spells and potions are remnants of pagan ways and beliefs, natural magic, hedgerow medicine, herbalism, and rural midwifery...all of the things that came to be seen as wild, wanton, associated with women, peasants, and other "backwards" folk of the countryside.

(We should remember, however, that there's also a long folkloric and historic tradition of "cunning

men" living in the wild, versed in natural magic and folk medicine.

Among the root workers and hoodoo doctors of the American South, for

example, or practioners of the Cunning Arts of the British Isles, one

finds both women and men weaving magic and medicine from herbs, charms,

roots, stones, wax and flame; from words, songs, music, and the

whispering of the bees.)

Baba Yaga, from Russian fairy tales, is one of the few fairy tale witches distinguished with a name, and the complexity of her character can be seen in the many stories told about her:

"Baba Yaga brings many of the dominant

themes of Russian fairy tales together," writes fairy tale scholar Helen Pilinovsky. "She travels on the wind,

occupies the domain of the leshii, the forest spirits, is associated with death, and is an acceptable surrogate for the generic ved'ma, or witch. Also known as 'Baba Yaga Kostinaya Noga,'

or 'Baba Yaga Bony Leg,' she possesses gnashing steel teeth and

penetrating eyes, and, in short, is quite enough to intimidate even the

most courageous (or foolhardy, depending on the tale) hero or heroine.

Like the witches of other cultures, her preferred method of

transportation is an implement commonly used for household labor, though

unlike the witches of the West, rather than traveling upon a broom, she

chooses to ride in a mortar, rowing with a pestle, and uses a broom to

sweep away the tracks that she leaves. Her home is a mobile hut

perched upon chicken legs, which folklorist Vladimir Propp hypothesized

might be related to the zoomorphic izbushkii, or initiation huts, where neophytes were symbolically 'consumed' by the monster, only to emerge later as adults.

"In his book An Introduction to the Russian Folktale,

Jack Haney points out that Baba Yaga's hut 'has much in common with the

village bathhouse … the place where many ritual ceremonies occurred,

including the initiatory rituals.' This corresponds to the role that her

domicile plays in the fairy tales of Russia: though the nature of the

initiation differs from story to story, dependent upon the circumstances

of the protagonist, Baba Yaga's presence invariably serves as a

signifier of change. Baba Yaga's domain is the forest, widely

acknowledged as a traditional symbol of change and a place of peril,

where she acts as either a challenger or a helper to those innocents who

venture into her realm. In Western tales, these two roles are

typically polarized, split into different characters stereotyped as

either 'witch' or 'fairy godmother.'

Baba Yaga, however, is a complex individual: depending on the

circumstances of the specific story, she may choose to use her powers

for good or ill."

In her excellent book From the Beast to the Blonde, Marina Warner suggests a kinship between forest-dwelling crones and the beasts of the woods. "In the witch-hunt fantasies of early modern Europe they [wolf and crone] are the kinds of being associated with marginal knowledge, who possess pagan secrets and in turn are possessed by them." In Little Red Riding Hood, for example: "Both [wolf and crone] dwell in the woods, both need food urgently (one because she's

sick, the other because he hasn't eaten in three days), and the little

girl cannot quite tell them apart."

In older versions of the story, called The Grandmother's Tale, the wolf-in-Granny-disguise tricks the girl into dining on meat and wine. She doesn't know that it is her grandmother's flesh and blood she's ingesting. Folklore scholar Yvonne Verdier liken this grisley meal to a sacrificial act, a physical

incorporation of the grandmother by her granddaughter. It's a scene

reminiscent of a wide variety of myths in which a warrior, shaman,

sorcerer, or witch attains another's knowledge or power through the

ritual ingestion of the other's heart, brain, liver, or spleen -- but

Verdier views it in more symbolic terms: "What

the tale tells us is the necessity of the

female biological transformation by which the young eliminate the old in

their own lifetime. Mothers will be replaced by their daughters and the

circle will be closed with the arrival of their children's children."

Several poets have explored the connection between the young female heroes of fairy tales and the witches who dwell at the heart of the woods, speculating on how the first might one day turn into the second. In "Becoming the Villainess," Jeanine Hall Gailey writes of one such young woman: "It seems unlikely now that she will ever return home, remember what it was like, her mother and father, the promises. She will adopt a new costume, set up shop in a witch's castle, perhaps lure young princes and princesses to herself, to cure what ails her — her loneliness, her grandeur, the way her heart has become a stone."

"The daughter is too bold to be anything but a cuckoo in the nest," says Holly Black in "Bone Mother." "Good girls sit home and sew in the dark. They don't go seeking fire in the witch's woods....There, she learns to part seed from stone, sweet from spoilt, fate from fortune."

In "Baba Yaga Duet" by mother-and-daughter authors Midori Snyder and Taiko Haessler, the younger initiate boasts to the witch: "I will teach you, now that you have burned your old recipes, the new ones I remedied. And I will uncover the hidden plants I've stashed in my hair, the worlds I have in my mouth, the tattoos woven in my skin and the sky I discovered in my breast."

"Here is the part I like, where I become the one to grant those wishes as I please," says narrator of Wendy Froud's poem "Faery Tale" (in the anthology Troll's Eye View), who has done her time in the hero role and is now relishing her cronehood. "Snakes and lizards, toads, diamonds, pearls and gold, a poisoned apple, gingerbread, a pumpkin coach, a gilded dress. Tools of my trade, my teaching aid. My gifts, my curses. Prince to frog, frog to prince, iron shoes and feet that dance and dance and dance, and I like it both ways, like to bless them and eat them."

There is, of course, a more positive way to look at the Wild Woman of the woods, which psychologist and cantadora storyteller Clarissa Pinkola Estés has explored extensively in works such as Women Who Run With the Wolves:

"Fairy tales, myths, and stories provide understandings which sharpen our sight so we can pick out and pick up the path left by the wildish nature. The instruction found in stories reassures us that the path has not run out, but still leads women deeper, and more deeply still, into their own knowing. The tracks which we are following are those of the Wild Woman archetype, the innate instinctual self....

"To adjoin the instinctual nature does not mean to come undone, change everything from right to left, from black to white, to move from east to west, to act crazy or out of control. It does not mean to lose one's primary socializations, or to become less human. It means quite the opposite. The wildish nature has vast integrity to it. It means to establish territory, to find one's pack, to be in one's body with certainty and pride regardless of the body's gifts and limitations, to speak and act in one's behalf, to be aware, alert, to draw on the powers of intuition and sensing, to come into one's cycles, to find out what one belongs to, to rise with dignity, to retain as much consciousness as we can."

"It's not by accident that the pristine wilderness of our planet disappears as the understanding of our own inner wild nature fades," Estés adds. "It is not so difficult to comprehend why old forests and old women are viewed as not very important resources. It is not such a mystery. It is not so coincidental that wolves and coyotes, bears and wildish women have similar reputations. They all share related instinctual archetypes, and as such, both are erroneously reputed to be ingracious, wholly and innately dangerous, and ravenous."

I'll end today with another quote on the Wild Woman from Estés, which I believe applies to all you Wild Men out there too:

"We are all filled with longing for the wild. There are few culturally sanctioned antidotes for this yearning. We were taught to feel shame for such a desire. We grew our hair long and used it to hide our feelings. But the shadow of the Wild Woman still lurks behind us during our days and in our nights. No matter where we are, the shadow that trots behind us is definitely four-footed."

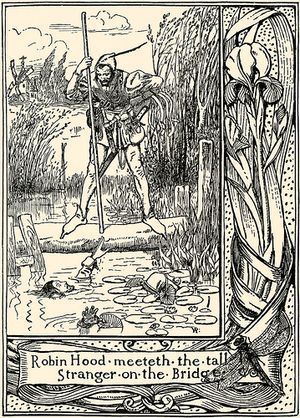

The wonderful wild-wood art above is: "Merlin" by Alan Lee; a 14th century manuscript illustration for Gawaine and the Green Knight; a scene from Valentine and Orson published in 1844 (artist unknown); a Robin Hood illustration by N.C. Wyeth; two Robin Hood illustrations by Howard Pyle; "Gretel and the Witch" by Arthur Rackham; Baba Yaga" by Forest Rogers; "Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf" by Trina Schart Hyman; "Vasilisa" by Ivan Bilibin; and two Wild Women drawn by Brian Froud.

May 30, 2013

The music of crows

I'm sorry that there's no post today, folks. I was out way too late watching Howard's band play, and must conserve the spoons I have left for work. (Am I just getting too old to be a folk-rocker's wife? Heaven forbid!) I'll be back to "Into the Woods" series tomorrow, with a post on Wild Men & Women this time.

Image above: The Nosy Crows (Steve Dooley, Howard, David Wyatt, and Jenny Dooley). Photograph by Stu Jenks.

May 29, 2013

Into the Woods, 7: The Handless Maiden and Forest Sanctuary

Jungian scholar Marie-Louise von Franz

saw the fairy tale forest not only as a place of trials for the hero, but also an archetypal setting for retreat, reflection, and healing. In a lecture presented to the

C.G. Jung Institute in Switzerland in the winter of 1958-59 (subsequently published as The Feminine in Fairytales), she looked at the role of

the forest in the story of "The Handless Maiden" (also known as "The Armless Maiden," "The Girl Without Hands," and "Silver Hands").

In this tale, a miller's daughter loses her hands as the result of a

foolish bargain her father has made with the devil. (In darker variants, it is because she will not give in to incestuous demands.) She then leaves home,

makes her way through the forest, and ends up foraging for pears (a fruit symbolic of female strength) in the garden of a tender-hearted king —

who falls in love, marries her, and gives her two new hands made of silver. The young woman gives birth to a son — but this is not the usual happy ending to the story. The king is away at war and the

devil interferes once again (or, in some versions, a malicious mother-in-law), tricking the court into casting both mother

and child back into the forest. "She is driven into nature," von Franz

points out. "She has to go into deep introversion.... The forest [is]

the place of unconventional inner life, in the deepest sense of the

word."

The Handless Maiden then encounters an angel who leads her to

a hut deep in the woods. Her human hands are

magically restored during this time of forest retreat. When her husband returns from the war, learns that

she's gone, and comes to fetch his wife and child home, she insists that he court her

all over again, as the new woman she is now. Her husband complies -- and

then, only then, does the tale conclude happily. The Handless Maiden's

transformation is now complete: from wounded child to whole, healed

woman; from miller's daughter to queen.

Von Franz compares the Handless

Maiden's time of solitude in the woods to that of religious mystics

seeking communion with god through nature. "In the Middle Ages, there

were many hermits," she notes, "and in Switzerland there were the

so-called Wood Brothers and Sisters. People who did not want to live a

monastic life but who wanted to live alone in the forest had both a

closeness to nature and also a great experience of spiritual inner life.

Such Wood Brothers and Sisters could be personalities on a high level

who had a spiritual fate and had to renounce active life for a time and

isolate themselves to find their own inner relationship to God. It is

not very different from what the shaman does in the Polar tribes, or

what the medicine men do all over the world, in order to seek immediate

personal religious experience in isolation."

In other versions of the Handless Maiden narrative, the young queen's time in the woods is not solitary. The angel (or "white spirit") leads her to an inn at the very heart of the forest, where she's taken in by gentle "folk of the woods." (It's not always made clear whether they are human or magical beings.) The queen stays with them for a full seven years (a traditional period of time for magical/shamanic initiation in ancient Greece and other cultures world-wide), during which time her hands slowly re-grow.

In an article titled "Healing the Wounded Wild," Kim Antieau uses this variant of the story to reflect on illness, the healing process, and the ways our relationship with the natural world impacts both physical and psychic health. "In many cultures," she writes, "the prescription for chronic illness was a stay in the

country (not necessarily the wild country). In ancient Greece, the

chronically ill went to Asklepian Temples for relief. The priests

created tenemos — sacred space — for the patient to help

facilitate healing. The ill went to the temples and prepared with

purification and ritual for a healing dream.

Then the patient went to the abaton — the sleeping

chamber — and dreamed. Often the dreams either healed the patients or

told them of a remedy which would heal them.

"Today, practitioners of integrated medicine believe the body wants to

heal, and the patient needs the time, encouragement, support and space

to be able to get well. In many instances the time, encouragement, and

support can be found, but wild spaces are lacking. Silvia [the Handless Maiden] was able to

travel deep into a wild place. Where do we go? Where do the wild things

go (including human beings) when no wild remains?"

Midori Snyder comes at the story from a different angle in her luminous article "The Armless Maiden and the Hero's Journey," examining the tale, in its various forms, as a classic rites of passage narrative.

When such stories are devised for young men, she notes, the hero typically sets off from home seeking adventure or fortune in the unknown world, where the

fantastic waits to challenge him. "Along the journey, his worth as a man

and as

a hero is tested. But when the trials are done, he returns home

again in triumph, bringing to his society new–found knowledge, maturity

and often a magical bride....

"While no less heroic, how different are the journeys of young

women. In folktales, the rite of passage from adolescence to adulthood

is confirmed by marriage and the assumption of adult roles. In

traditional exogamous societies, young women

were required to leave forever the familiar home of their birth and

become brides in foreign and sometimes faraway households. In the

folktales, a young girl ventures or is turned out into the ambiguous

world of the fantastic, knowing that she will never return home. Instead

at the end of a perilous and solitary journey, she arrives at a new

village or kingdom. There,

disguised as a dirty–faced servant, a scullery maid, or a goose

girl, she completes her initiation as an adult and, like her male

counterpart, brings to her new community the gifts of knowledge,

maturity, and fertility."

Although fairy tales have been known as children's stories from roughly the 19th century onward, older versions of these same narratives (aimed at older audiences) looked unflinchingly at the darkest parts of

life: at poverty, hunger, abuse of power, domestic violence, incest,

rape, the sale of young daughters to the highest bidder under the guise of

arranged marriages, the effects of remarriage on family dynamics, the

loss of inheritance or identity, the survival of treachery or calamity. In rites of passage tales devised for young women, the heroes don't tend to ride merrily off into the forest in search of fame and fortune, they are usually driven there by desperation; the forest, despite its perils, is a place of refuge from worse dangers left behind.

The Handless/Armless Maiden is not a passive princess in the old Disney mold, waiting for romance to rescue her. She finds her own way to the orchard of a king in her search of food, and although she agrees to marry him, a royal wedding is not the conclusion of her story, it's the half-way point. "It is a narrative with a strange hiccup in the middle," Midori points out. "The brutality of

the opening scene seems resolved as the Armless Maiden is rescued in a

garden and then married to a compassionate young man. But she

has not completed her journey of transformation from adolescence to

adulthood. She is not whole, not the girl she was nor

the woman she was meant to be. The narratives make it clear that

without her arms, she is unable to fulfill her role as an adult. She can

do nothing for herself, not even care for her own child.

"Conflict is reintroduced into the narrative

"Conflict is reintroduced into the narrative

to send the girl back on her journey of initiation in the woods. There

the fantastic heals her, and she

returns reborn as a woman. Every narrative

version concludes with what is in effect a second marriage. The

woman, now whole, her arms restored by an act of magic, has become

herself the magic bride, aligned with the creative power of nature. She

does not return immediately to her husband but waits with her child in

the forest or a neighboring homestead for him to find her.

When he comes to propose marriage this second time, it is a marriage

of equals, based on respect and not pity.

"I have come to believe," Midori continues, "that robust narratives such as the Armless

Maiden speak to women not only when they are young and setting out on

that first rite of passage, but throughout their lives. In Women Who Run With the Wolves, psychologist Clarissa Pinkola Estés presents a fascinating analysis of this tale, demonstrating

the guiding role the armless maiden plays in a woman's psychic life:

'The Handless Maiden' is about a woman's initiation into the underground forest through the rite of endurance. The word endurance

sounds as though it means 'to continue without cessation,' and while

this is an occasional part of the tasks underlying the tale, the word endurance

also means 'to harden, to make robust, to strengthen,' and this is the

principal thrust of the tale, and the generative feature of a woman's

long psychic life. We don't just go on to go on. Endurance means we are

making something.'

"To follow the example of the armless maiden is an invitation to

sever old identities and crippling habits by journeying again and again

into the forest. There we may once more encounter emergent selves

waiting for us. In the narrative, the Armless Maiden sits on the bank of a

rejuvenating lake and learns to caress and care for her child, the

physical manifestation of her creative power. Each time

we follow the Armless Maiden she brings us face to face with our

own creative selves."

British poet Vicki Feaver has also reflected on the story in relationship to creativity. In an interview in Poetry Magazine, Feaver discusses her poem "The Handless Maiden," inspired by the fairy tale :

"The story is that the girl’s hands are cut off by her father and she

is given silver hands by the king who falls in love with her.

Eventually, she goes off into the forest with her child and her own

hands grow back. In the Grimms' version it is because she’s good for

seven years. But there’s a Russian version which I like better where she

drops her child into a spring as she bends down to drink. She plunges

her handless arms into the water to save the child and it’s at that

moment that her hands grow. I read a psychoanalytic interpretation by

Marie Louise von France in her book, The Feminine in Fairytales in

which she argues that the story reflects the way women cut off their

own hands to live through powerful and creative men. They need to go

into the forest, into nature, to live by themselves, as a way of

regaining their own power. The child in the story represents the woman’s

creativity that only the woman herself can save. This was such a

powerful idea that I had to write about it. It took me three years to

find a way of doing it. In the end I chose the voice of the Handless

Maiden herself -- as if I was writing the poem with the hands that grew

at the moment that she rescued her work, her child.

"I suppose I go through the process of endlessly cutting off my hands

and having to grow them again. You ask if I’ve found any strategies for

writing. Only to go away on my own, to be myself, and just to write."

"Fairy tales are journey stories," says Ellen Steiber (in a beautiful essay on the fairy tale "Brother and Sister"). "They deal with initiation and

transformation, with going into the forest where one's deepest fears and

most powerful dreams are realized. Many of them offer a map for getting

through to the other side."

In the universe of fairy tales, the Just often find a way to prevail,

the Wicked generally receive their comeuppance — but there's more to

such tales than a formula of abuse and retribution.

The trials these wounded young heroes encounter illustrate the

process of transformation: from youth to adulthood, from victim to hero,

from a maimed state to wholeness, from passivity to action. Fairy tales are, as Ellen says, maps through the woods, trails of stones to mark the path, marks carved into trees to let us know that other women and men have been this way before.

Though they warn us to steer clear of gingerbread houses and huts that stalk the woods on chicken's feet, they also show the way to true shelter, sanctuary, and places of healing deep in the forest. (The real lesson here, it seems to me, is to learn to tell the difference.) Think of the hut in "Brother and Sister," for example, where the siblings set up housekeeping in the woods, far from the everyday world (and their stepmother's malice), adapting to the rhythms of the forest, of self-sufficiency, and of the brother's enchantment. Or the woodland cabin in "The White Deer," where the deer-princess sleeps safely each night. Or the cottage (or cave) where Snow White finds shelter with a band of rough forest-dwelling men (the metal-working dwarves of Teutonic folklore in some versions, outlaws and brigands in others). Even the Beast's lonely castle deep in the woods is more sanctuary than prison...a place where captor and prisoner both transform, in true fairy tale fashion.

These places are linked not only by their woodland settings, but by the temporary nature of the sanctuary provided. The curse is broken or the secret revealed, or the magical task finshed, or the trial survived; transformation is complete, and the hero must now return to the human world. Traditionally, rites-of-passage ceremonies are designed to propel initiates into a sacred place and sacred state (the realm of the spirits, gods, or ancestors; the place of vision, instruction, and metamorphosis)...but then to bring them back again, back to the tribe or community and to ordinary life. We're meant to come out of sweatlodge, down from the Vision Quest hill, home from the Moon Hut, back from the sacred hunt, bringing with us new knowledge, new dreams, a new status, a new name or role to play....intended not just for the sake of personal growth but in service to the whole tribe or community. Likewise, we're not meant to remain in the circle of enchantment deep in the fairy tale forest -- we're meant to come back out again, bringing our hard-won knowledge and fortune with us...in service to the family (old or new), the realm, the community; to children and the future.

These places are linked not only by their woodland settings, but by the temporary nature of the sanctuary provided. The curse is broken or the secret revealed, or the magical task finshed, or the trial survived; transformation is complete, and the hero must now return to the human world. Traditionally, rites-of-passage ceremonies are designed to propel initiates into a sacred place and sacred state (the realm of the spirits, gods, or ancestors; the place of vision, instruction, and metamorphosis)...but then to bring them back again, back to the tribe or community and to ordinary life. We're meant to come out of sweatlodge, down from the Vision Quest hill, home from the Moon Hut, back from the sacred hunt, bringing with us new knowledge, new dreams, a new status, a new name or role to play....intended not just for the sake of personal growth but in service to the whole tribe or community. Likewise, we're not meant to remain in the circle of enchantment deep in the fairy tale forest -- we're meant to come back out again, bringing our hard-won knowledge and fortune with us...in service to the family (old or new), the realm, the community; to children and the future.

Unless, that is, we stay in the woods and take on a different role in the story...not a hero this time, but one of the forest dwellers who aids (or hinders) another's journey: the woodwose, the hermit, the sage, the mad prophet...the men and woman who run with the wolves...the femme sauvage with her herbs and charms... the conjure man with his beehives and songs....

But those are stories for another day, and another journey into the woods.

The gorgeous paintings above are by one of my all-time favorite artists, Jeanie Tomanek, who lives and works in Georgia, near Atlanta.

"My all-time favorite folktale is 'The Handless Maiden,'" says Jeanie. "It is

about a woman’s journey toward wisdom and self-realization and the

obstacles and helpers she encounters. This tale encompasses many of the

archetypical representations of women. My 'Everywomen' portray the

mothers, daughters, lovers, and crones. Strong, wise women who will

survive. These are filtered through my own experiences many times."

The paintings here are: The Handless Maiden, Forget Me Not, Communion,

Fairy Tales, The Diary, Silver Hands, Silver Hands and the Numbered

Pears, The Diary, Envoy, and Sometimes in the Forest. (All imagery copyright by the artist.) Please visit Jeanie Tomanek's website to see more of her work, and Everywoman Art on Etsy to purchase originals and prints. You'll find a recent interview with the artist here.

May 27, 2013

Tunes for a Tuesday Morning

Since yesterday was a holiday, our "Monday Tunes" are on Tuesday this week, and we're still roaming among the trees, led on this time by women's voices....

Above: "Stags Bellow," a wonderful woodland (and ocean) song by Martha Tilston, who lives not far from here on the Cornish coast. It's an autumnal piece, but it fits our theme, if not the season, and is too lovely to wait until autumn to share. It comes from Tilston's 9th album, Machines of Love and Grace (2012).

I wish I could also play her Little Riding Hood song, "Red," this morning -- but there are no good videos for it, alas. (There's a poor quality one here, but it doesn't do the song justice.) "Red" is on Tilston's 2004 album Bimbling, and if you're a fairy tale fan, it's well worth seeking out the recorded version.

Next, two songs by the American folk singer and songwriter Alela Diane, who is based in Portland, Oregon.

Above: "Pieces of String," a lovely song from her debut album, The Pirate's Gospel, back in 2006.

Below: "The Alder Trees, " a gently magical arboreal song from her second album To Be Still, 2009.

Next:

"The Willow Tree," a sad but very beautiful song performed by the Celtic harp trio Triskela (Diane Stork, Portia Diwa, and Shawna Spiteri), from the Bay Area of California.

And for the last song, let's add some men's voices too:

Here's "Oak, Ash, and Thorn," sung by the English folk singer & folk scholar Fay Hield, backed up by The Hurricane Party: Rob Harbron, Sam Sweeney, Andy Cutting, and Hield's partner Jon Boden. This impromptu performance was filmed in the bar at Cecil Sharpe House (home of The English Folk Dance and Song Society) after Hield's gig there last autumn. The words are from a Rudyard Kipling poem, put to music by the great Peter Bellamy.

May 24, 2013

The Dog's Tale

We're supposed to be out of the office this weekend, but I've snuck back in while my People aren't looking so I can write up my Saturday post. My paws are a little clumsy, but if I sit up like a Person, I can just about manage the computer by myself. My post today is my first piece of canine poetry:

Ode to the Neighbor's Cats

Thou still unravish'd demons of fur,

Thou taunting creatures of tooth and tail,

As brazen beasts as e'er there were

Whilst over garden wall do sail:

What evil does thou plot today

To taunt a brave and noble dog

Who's honor bound to chase away

All cats who set foot in this yard?

What beasts are these, half Siamese?

What mad pursuit? What fleet escape?

What howls and barks? What wild ecstasies...

But wait, but wait...what's this?

Oh no! I hear my People coming!

Quick! Turn the computer off!

"Me? What am I doing? Uh...nothing."

"Just sitting here chewing my bone...."

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 707 followers