Terri Windling's Blog, page 188

June 27, 2013

Into the Woods, 13: Art From the Fairy Tale Forest

"What

was the appeal [of fairy tales]? It's hard to be definite about that.

The stories didn't have any direct application to our real lives. They

weren't much good from a practicle point of view. At this time, we were

living half the year in the Canadian north woods, and we knew if we went

for a walk there, we were unlikely to come upon any castles, if we met

any wolves or bears they wouldn't be the talking kind, if we kissed a

frog it would most likely pee on us, and if we got lost, we wouldn't

find any short-sighted, evil old women with patisserie cottages and

child-sized ovens. Rescue, if any, would not be applied by princes. So

it wasn't our outer lives that Grimms' tales addressed: it was our inner

ones. These stories have survived as stories, over so many centuries

and in so many variations, because they do make such an appeal to the

inner life -- you could say 'the dreaming self' and not be far wrong,

because they are both the stuff of nightmare and magical thinking. As

Margaret Drabble says, there is a mystery in such stories which is

beyond the rational mind."

- Margaret Atwood

"From time to time, I still pull [Grimms' Fairy Tales] down from the shelf,

especially when I am writing; I recently discovered details from 'The

Maiden Without Hands' and 'Godfather Death' popping up in the novel at

which I am currently at work. I found myself rereading the stories,

mesmerized once again.; I was startled to realize that the fairy tales

were still deeply twined into my unconscious life, and because the act

of writing taps the vein of the unconcious so silently, the tales flood

back into my current stories with their metaphors and morals at the

times when I am most unaware, most deeply immersed in creation. I

thought I could leave the Grimms brothers behind, but -- as with any

strong and complicated relationship -- it has not proved to be nearly as

simple as that." - Linda Gray Sexton

"Fairy

Tales were the refuge of my troubled childhood. Despite all the

messages contained in them about being a dutiful daughter, a good

girl, which I internalized to some extent, I was most obsessed with

the idea of justice, the insistence in most tales that the righteous

would prevail.”

- bell hooks

"The more one knows fairy tales the less fantastical they appear; they

can be vehicles of the grimmest realism, expressing hope against all the

odds with gritted teeth.” - Marina Warner

"Early on I realized that stories could save you. " - Julia Alvarez

Kinder– und Haumärchen

by Diane Thiel

Liegt in dem Märchen miener Kinderjahre

Als in der Wahrheit, die das Leben lehrt.

—Frederich Schiller

(Deeper meaning lies in the fairy tales of my childhood

than in the truth that is taught in life.)

Saint Nikolaus had a giant gunny sack

to put the children in if they were bad.

It was a hole so deep you'd never come back.

A porch swing full of stories, where the smoke

went up in hot, concentric, perfect rings

and filled our heads with unbelievable things

A nursery heavy with a history

where nothing was whatever it had seemed,

where Aschenputtel's sisters cut their feet

half off — so desperate they were to fit.

And in the end, they also lost their eyes

when steel–grey birds descended from the skies.

Rotkäppchen's wolf was someone that she knew,

who wooed her with a man's words in the woods.

But she escaped. It always struck me most

how Grandmother, whose world was swallowed whole,

leapt fully formed out of the wolf alive.

Her will came down the decades to survive

in mine — my heart still desperately believes

the stories where somebody re–conceives

herself, emerges from the hidden belly,

the warring home dug deep inside the city.

We live today those stories we were told.

Es war einmal im tiefen tiefen Wald.

"This earth that we live on is full of stories in the same way that, for a

fish, the ocean is full of ocean. Some people say when we are born

we’re born into stories. I say we’re also born from stories."

- Ben Okri

Indeed, we are.

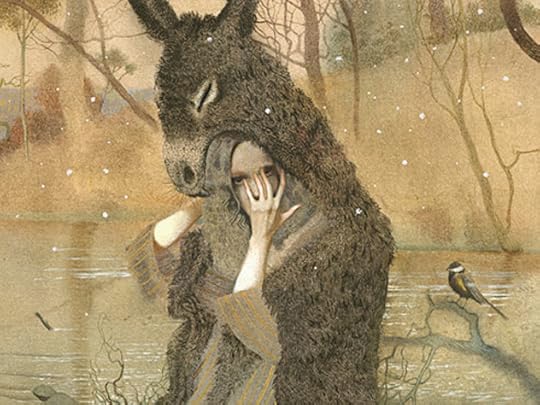

The art of the fairy tale forest above is: "Snow White" by Nancy Ekholm Burkert, "Snow White" by Yvonne Gilbert, The Twelve Dancing Princesses" by Ruth Sanderson, "Donkeyskin" by Nadezhda Illarionova, "Donkeyskin" by Toshiyuki Enoki, "Little Red Riding Hood" by

Daniel Egnéus, "Little Red Cap" by Lisbeth Zwerger,

"Sleeping Beauty" illustrations by Errol Le Cain,

Kinuko Y. Craft, and Mercer Mayer.

June 25, 2013

Into the Woods, 12: Deep in the Forest, a guest post by Valerianna Claff

What would it be like to live and work at the heart of a forest? I put this question to artist and educator Valerianna Claff, whose RavenWood Studio nestles among the hemlocks of western

Massachusetts....

"Early morning sun finds its way through

the trees in long, angled rays," writes Valerianna, describing a typical day at RavenWood. "Dew rises from the glistening mosses

becoming a gentle mist, a hermit thrush sings far off in the forest.

I sit in a chair outside the back door, watching the majesty of the

morning, taking note of the inch or two of unfurling the ferns have

managed since yesterday. Sipping coffee, I mostly look and listen –

a kind of morning meditation – letting my mind wander and feeling

the shape of twinleaf and foamflower in my body. I feel the gentle

movement of the long, lacelike hemlock boughs, blown by a slight

movement of air. The towering trunks bring me to the awareness of my

spine and I watch as a red eft meanders through the woodland garden.

I rise and pinch a bit of new spring hemlock needles, put it in my

mouth, tasting yellow-greenness and a slight hint of citrus. Under

the Grandmother tree, I bend and pick a partridge berry – not very

tasty – but offering some red to my morning nutrition. Kicking off

my clogs, I find a place on the mosses, and go through my Qigong

routine. Swatting at mosquitoes, I wish I might become evolved enough

to let them be. Pasha brushes past my leg, damp from his morning

wander, full of purrs and stories, a wild glint in his green-gold

eyes.

"It has been ten years since I came to

this forest, and I think I am beginning to know something of the

nature here. I am not so far from civilization, only a mile from the

center of town, but such a tiny town with nothing more than a library

(about the size of my downstairs), a general store, church, fire

station, post office and a few bed-and-breakfasts. Not one stoplight

or gas station or pub. Livestock and wildlife outnumber people, and

the lack of human-made sounds is noticeable. Unlike my years in the

city, when I hear a lawnmower here, it seems to bring me some

comfort, as if to say, no, you are not completely alone in the

wilderness. A twenty-minute drive brings me to Northampton, a small

city with a big heart. From there, the road leads to small towns and

cities, famous educational institutions, museums and the house of

Emily Dickenson, which seems always to be waving at me from across

the valley.

"When I arrived here, I had a plan of a

small retreat center with drum circles and large seasonal gatherings

and guest teachers and performances. Wandering the land in that first

autumn, my plans fell off me, floating to the earth to mingle with

oak leaves. As I began to feel the spirit of this forest, I

understood that this was not a place of grand views and loud,

expansive expression, but a quiet, inward land, asking for listening

and rooting and reflecting beside still pools and moss covered

ledges. On the first misty walk my mother took with me here, she said

she was expecting King Arthur to ride over the hill, as the land

seemed to be whispering stories as we walked.

"As the steward of a deep and inward

forest, I am called to sit and listen and trust in stillness. Again

and again, as the twenty-first century woman that I am becomes

uncomfortable with stillness, I am asked to wait, to listen longer,

remain still, root deeper.

"The seasonal gatherings to celebrate

Equinoxes and Solstices do happen, but they are small, intimate

gatherings around a small fire where songs and stories are shared and

owls and coyotes offer their calls to the circle. Small groups of

seekers come to do their inner work, learning from the stillness and

remembering something about dreaming and how to let their bodies be

held by the earth and to find ways of communicating and knowing

beyond words and intellect.

"The forest has taught me – as any

wild place would – to embrace the long, dark days of winter as a

time to nourish the soul with fire and stories and deep, deep

dreaming. I understand something of a dark underworld journey, and

the enormous gifts of seeing it through to the end. A few years ago,

after the loss of a loved one, I found myself on such a journey… it

seemed to never end. I had to ignore impulses to go out and manifest

and DO as a stronger voice continued to tell me to wait. One cold

February morning, I awoke with a clear knowing of how to move outward

again. I understood that I needed to bring my teaching more fully to

the forest, to integrate all the parts of me, to share my

relationship with the wild and to invite others to know stillness. I

needed a grant to build a studio. I looked up a grant I had heard

about that offers assistance to forest-based businesses encouraging

forest owners to keep their land forested. The grant had not given

out money in several years, but that year they were offering grants

and the application was due in a month. I applied, got the grant, and

RavenWood Forest, Studio of Mythic & Environmental Arts was

built.

"A precious gift I have received from

this forest is the gift of remembering. Finding a place just far

enough away from the bustle, where the wild feels bigger than the

human world, I remember myself as a soul being, quite removed from

the definitions, boxes and labels that culture puts on me. When the

owl comes to spend the day on her sunny perch outside my window, or a

bear lumbers by, or I find a luna moth resting in a shady spot under

a leaf, or I walk out to a garden filled with hundreds of dragon

flies, darting this way and that, I am entranced and fully present

with what is left of the wild within me.

A bear comes out of the trees, seeking ants to eat

A bear comes out of the trees, seeking ants to eat

"But there are shadows here, too. One

cannot spend years peering into the dark, still pools without being

brought to one’s knees. Living alone here, I sometimes need to seek

refuge in a town to walk around and look in shops and NOT be down

under the towering trees. I need to go to the ridge top and be loud

and expansive. My job as an adjunct art professor helps with getting

me out, and, as teaching does, keeps my world full of young folk and

forces me out of dreaming and into intellectual conversation. This is

good for me. The long commute and the less than fair pay isn’t so

good, but I stay connected.

"So it might seem that I have become a

bit like the witch in the woods, like the character from my favorite

childhood film, “The Three Lives of Thomasina”. She lives in an

idyllic cottage in the forest, knows the language of birds and foxes,

grows her own food and is the wise woman healer that the children

bring their injured animals to. This is the romantic version, in

truth, I can’t quite get enough light for a vegetable garden to

grow well, there is a big mortgage to pay, I live very close to the

financial edge, and my sensitivities to chemicals and mold have me

flattened more than active these days.

"Being flattened however, isn’t always

a negative thing, I am called to stillness again, and there is good

medicine in that. As a storyteller in image, words and song, whose

inspiration is the mystery of the forest, quiet dreaming is essential

to my creative work. This past year, as I grieve the loss of my

mother, and am healing the roots of my illness, I find myself

painting images that tell the stories of the deep forest. I’m

beginning to get at the essence of this place - a dark and mysterious

woodland – with gentle wildflowers growing from the leaf mold, and

root-tangled caverns under fallen trees that might well lead to the

underworld. The stories that find me here are fierce as well as

gentle. I live amongst large predators who might eat my beloved cat

friend or even me, where the tiny Woolly Adelgid threatens to kill

all my trees, and the well has run dry once or twice, leaving the

herbs in the garden to wilt. I sometimes fantasize about life in a

gypsy caravan, traveling from town to town, telling stories and

singing with my drum, but I am more like a tree than a

songbird, and its good to know who I am, lest I follow someone else’s

dream and find myself utterly lost without my tribe of trees.

"Late Winter Forest,” watercolor, 11” x 15”, V. Claff, 2013

"Late Winter Forest,” watercolor, 11” x 15”, V. Claff, 2013

"Strange Light,” watercolor, 22" x 30", V. Claff, 2013

"Strange Light,” watercolor, 22" x 30", V. Claff, 2013

"Forest Mystery,” watercolor, 22" x 30”, V. Claff, 2013

"Forest Mystery,” watercolor, 22" x 30”, V. Claff, 2013

"I spread my mother’s ashes in the

moss garden on the last day of May, as she asked me to do. I think

about the blessing of this – of how humans of old stayed where

their ancestor’s bones decayed and became part of the soil, and how

their very DNA became a part of that land. I wonder how living on

land where one’s ancestors have been buried for centuries might be

– would it be easier to speak with stones? Will the mosses begin to

whisper their secrets to me, now that my mother’s spirit mingles

with the ground here?

"Winter Mists,” watercolor, 11” x 15”, V. Claff, 2013

"Winter Mists,” watercolor, 11” x 15”, V. Claff, 2013

"The path beneath my feet is soft and

spongy. I think about the generations of trees that have fallen to

earth and become this ground, the tree-ancestors of the forest. Bones

of the Eastern Woodland Indians and the first European settlers, long

gone to dust, mingle here. The bear who didn’t put on enough fat

before an unusually long winter is curled beneath the roots of an

enormous pine tree, her body nourishing its roots as she dreams her

forever dream. As I walk, I hear the call of a raven, shattering the

quiet and filling the vast space between us. I sit on a boulder I

call the whispering stone, my quiet cat beside me, listening as the

raven’s call fades and the sound of black wings thrums past

overhead."

"Three Seed Stones," ink on paper, V. Claff

"Three Seed Stones," ink on paper, V. Claff

To

see more of Valerianna's beautiful work and learn more about the

RavenWood Forest Studio of Mythic & Environmental Arts, please visit

the RavenWood website and blog.

Once upon a time....

" 'Once upon a time,' the stories would begin...no particular time, fictional time, fairy-story time. This is a doorway; if you're lucky, you go through it as a child, aurally, before you can read, and if you are very lucky, you become a free citizen of an ancient republic and can come and go as you please. These stories are deeply embedded in my imagination. As I grew up and became a writer, I found myself going back and using them, retelling them ever since, working partly on the principle that a tale which has been around for centuries is highly likely to be a better story than one I just made up yesterday; and partly on the deep sense that they can tell more truth, more economically, than slices of contemporary realism. The stories are so tough and shrewd formally that I can use them for anything I want -- feminist revisioning, psychological exploration, malicious humour, magical realism, nature writing. They are generous, true, and enchanted." - Sara Maitland

"Deeper meaning resides in the fairy tales told to me in my childhood than in any truth that is taught in life." - Johann C. Friedrich von Schiller

"Do people choose the art that inspires them — do they think it

over, decide they might prefer the fabulous to the real? For me, it was

those early readings of fairy tales that made me who I was as a reader

and, later on, as a storyteller." - Alice Hoffman

"For most of human history, 'literature,' both fiction and poetry,

has been narrated, not written -- heard, not read. So fairy tales, folk

tales, stories from the oral tradition, are all of them the most vital

connection we have with the imaginations of the ordinary men and women

whose labor created our world." - Angela Carter

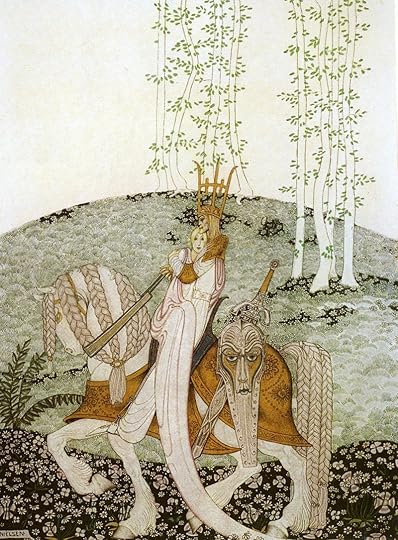

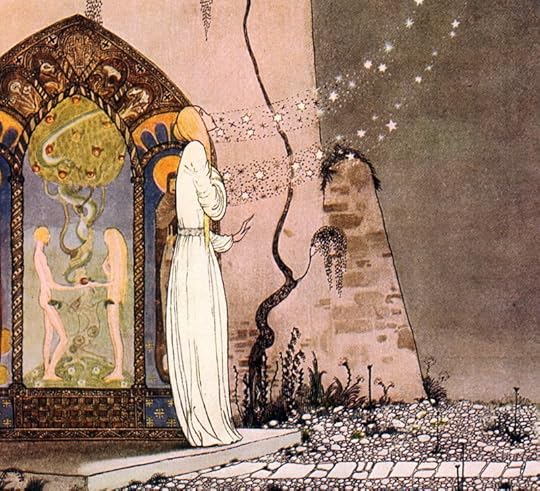

The illustrations above are by the great Kay Nielsen (1886-1957). To learn more about his enchanted and tragic life in Denmark and California, go here. For further reading on the authors quoted in the post, follow the links above. I'll be heading back "Into the Woods" tomorrow, with a guest post: "Deep in the Forest." (I also hope to get back to my usual early-morning posting time, just as soon as health permits.)

June 24, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

My apologies for being gone for so long. Health issues and exhaustion swallowed me up, but I'm back in the office this morning, attempting to get back on my feet.

Today's music is "Passacaglia: Partita for 8 Voices" by Caroline Shaw -- who, though only 30, won the Pulitzer Prize for music this year. In the video above, Shaw's composition is performed by the vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

"They say that a young artist should master the idioms of the past before

discarding them for whatever’s next," says J. Bryan Lowder (in an article about the piece worth reading in full). "Despite the unconventional

markings, Shaw has clearly done this. She raids the vocal traditions of

different eras and cultures in order to assemble something fresh and yet

familiar, but only just.... This is a deceptive sort of music, with an elegant, easy smoothness

built from distinct and fascinating bits-and-pieces. Listening to it is a

little like examining a great mosaic, both from a distance and

occasionally with a magnifying glass, the better to see the grout

between the tiles. Perhaps coincidentally, one of Shaw’s idiosyncratic

style guidelines is 'silk shoes gliding over marble mosaic.' She’s

trying to tell her musicians how to sound, but she might as well have

been telling us how to listen—no description could be more apt. "

Below, Shaw herself, as a member of Va Vocals (Martha Cluver, Caroline Shaw and Mellissa Hughes), singing "I Want to Live Where You Live" by David Lang. This simple but haunting performance was recorded in the Rare Book Room in the Strand bookstore, New York City, this past April. The song comes from Shelter, a musical collaboration between Lang, Michael Jordan, and Julia Wolfe.

June 23, 2013

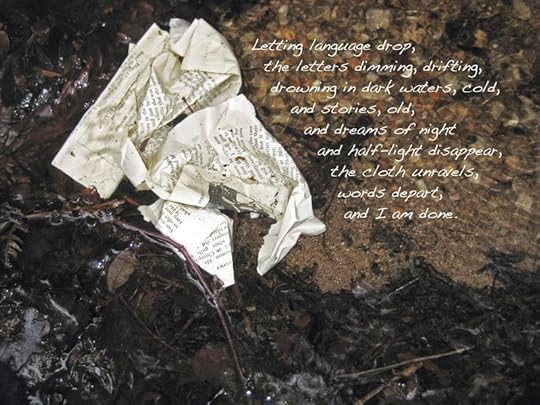

Mysteries

As I climb back into life again, following a period of poor health, I'm thinking about cycles of life and art and moon and stars and the land around us: the bright and the dark...the gentle and the cruel...the soft, sweet days and the days as hard as stone...the art that flies and the art that fails...the words that flow and words that choke...the physical strength that comes and goes. The seasons turn. The days roll by: we wake, we sleep, we wake again. Our lives are lived in cycles that take no notice of schedules, lists and plans, embedded as we are in larger turnings: the rising of the sap and the falling of the leaves; the rhythmic slap of water on the shore; the world breathing in and out, in and out, as we rise and fall, and rise once more.

"Illness is one of the Mysteries," says poet Marjorie Clarke. "I fear it. I respect it. I learn from it.''

I want to be fully present in this world; to move with its rhythms and not against them; to accept and respect the dark days too. To learn. To breathe. To fall and rise again. And again. And again.

And what else can we do when the mysteries present themselves

but hope to pluck from the basket the brisk words

that will applaud them,

the heron, the turtle, the catbird, the seed-grain

kneeling in the dark earth, its body

opening into the golden world?

- Mary Oliver (from "Mysteries, Four of the Simple Ones")

''Where is our comfort but in the free, uninvolved, finally mysterious beauty and grace of this world that we did not make, that has no price? Where is our sanity but there? Where is our pleasure but in working and resting kindly in the presence of this world?''

- Wendell Berry (from The Art of the Commonplace)

June 22, 2013

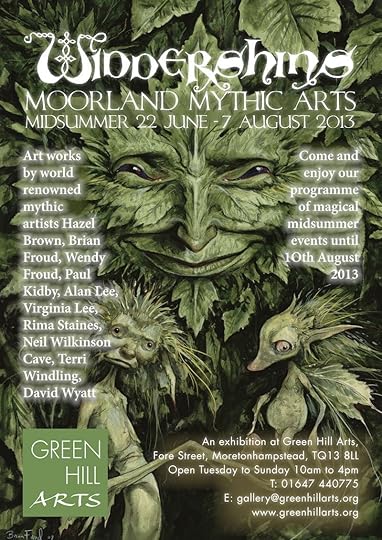

Widdershins: Dartmoor Mythic Arts

The Widdershins exhibition is now open, running

until August 10 at the Green Hill Arts Centre in Moretonhampstead, Devon. If you're in the West Country, or coming down here over the summer, please stop in.

I'll be giving a talk on women in fairy tales (looking

at the adult history of the tales), with storytelling by Howard, next

Saturday evening, June 29. The ticket

price is £6, all proceeds going to the gallery (which is a nonprofit

community arts space). There are many other magical events connected to the

show...music, workshops, a tea party, a screening of The Dark Crystal with a talk by Brian & Wendy Froud, and more. Information can be found on the Green Hill website.

Below, just a few pieces on display in the exhibition....

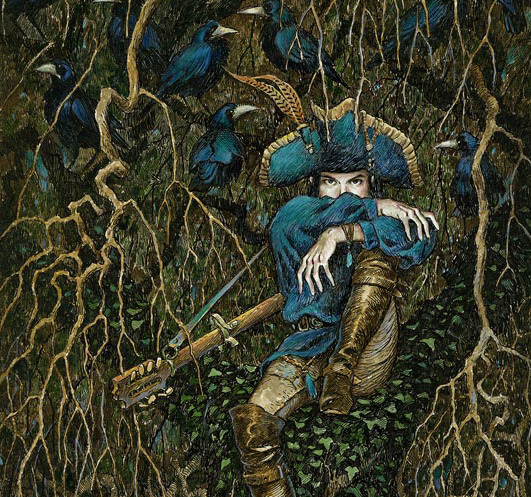

detail from a painting by David Wyatt

detail from a painting by David Wyatt

detail from a painting by Rima Staines

detail from a painting by Rima Staines

fairy boxes and books by Hazel Brown, with fairies by Wendy Froud

fairy boxes and books by Hazel Brown, with fairies by Wendy Froud

detail from a painting by Virginia Lee

detail from a painting by Virginia Lee

detail from a sculpture by Virginia Lee

detail from a sculpture by Virginia Lee

June 16, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, songs about fathers....

Above: "My Father" by Bruce Springsteen, the great poet of working class New Jersey life (which is where I did some of my growing up too). He wrote quite a lot of songs about his complicated relationship with his father -- and this, I think, is one of the best. There's no video to go along with it, but the song is powerful just on its own. (To learn more about Springsteen and his father, I recommend the article "Springsteen at 62," published in the New Yorker not too long ago. You can read it online here.)

Below: English folk musician Martin Simpson sings "Never Any Good," a beautifully bittersweet song about his dad, performed live at the Union Chapel. That's Andy Seward on double-bass, Andy Cutting on squeeze box, and Kellie While singing back-up.

Above: "Tank Park Salute," a sad, touching song from England's Billy Bragg (recorded back in 1991), about the death of his father. A lot of people I know have have lost parents in the last year, so this one's for all of you.

And last, turning from from fathers past to fathers of the present: "A Father's First Spring" by North Carolina's The Avett Brothers. This simple (and simply lovely) performance was filmed up in Alaska.

June 13, 2013

Following Tilly

Just pictures today for I've run out of words. Tilly is going to take you up the hill and it's your turn to decide what the story is....

There will be more "Into the Woods" posts, and other things, in the week ahead. Have a good weekend, everyone.

Into the Woods, 11: Water, Wild and Sacred

On a bright, clear morning some years ago, during the long, lovely days leading up to summer solstice, Wendy Froud and I drove through the lanes to the village of Callington in Cornwall (the county just to the west of Devon). We parked at the edge of a farmyard and

followed what was then an overgrown footpath to Dupath Well (originally "Theu Path" Well)...a deeply magical place buried in the green of the Cornish countryside.

Like other holy wells in Devon and Cornwall, the spring that runs through Dupath Well is

Like other holy wells in Devon and Cornwall, the spring that runs through Dupath Well is

believed to have been a sacred site to Celtic peoples in the distant

past, its older use now overlaid with a gloss of Christian legendry.

At one time, this spring may have sat in a woodland grove of oak,

rowan and thorn — trees sacred to the island's indigenous religions. In 1510, a group of Augustinian monks claimed

the Dupath site for their own use, enclosing the sacred spring in a small

well-house made out of rough-hewn granite. This was a common fate for many of the ancient sacred sites in the West Country. Unable to dissuade

the local people from visiting their holy places, Christian authorities simply took them over, building churches where

standing stones once stood and baptisteries over sacred springs, cutting down ceremonial groves and putting woodhenges to the torch. There are many, many wells like Dupath Well, scattered all over the West Country --- some of them covered and some still in use -- often named now for the Saints and associated

with their miraculous lives. But scratch the surface of these legends

and the palimpsests of older tales emerge: stories of fairies and piskies, the knights of King Arthur, and the old gods of the land.

Inside the

tiny, chapel-like building erected over Dupath Well, the water

pools in a shallow trough carved from a single granite slab. The air is thick, heavy with shadows, and with the ghosts, perhaps, of men

and women drawn to this spot for many centuries. The stones are

worn where they once knelt and prayed to the Virgin Mary, or to the Lady of the Waters. That day, on the bottom of the trough lay a handful of

copper coins, a modern custom of making wishes that is not so very

different from the older practice of throwing pins (associated with women's labor and magic) into a spring to ask for the water spirit's blessing. Wendy placed a small offering of

wildflowers by the water -- which, too, is an ancient practice, recalling a

time when it was the land itself our ancestors thanked for the gift of water, and of life itself.

Today, with

clean water piped directly into our homes and largely taken for

granted, it takes a leap of imagination to consider how precious water would have beento those who fetched it daily from the riverside

or village well. Deeply dependent on good local water sources, it's only natural that our ancestors would have revered those

places where pure, life-sustaining water emerged like magic from the depths of

the earth. Water plays a central role in myth, folk tales, fairy lore, and

sacred stories not only here in the rain-soaked British Isles but all around the globe -- particularly, of course, in

arid lands where the gift of water is most precious.

Many

Many

cultures associate water with women: with the Goddess, or

with several goddesses, or a variety of female nature spirits. The !Kung

of Botswana, for example attribute the mythic origin of water to

women, granting all women special power over water in all its form.

All-mother, in an Aboriginal myth from northern Australia, arrived

from the sea in the form of a rainbow serpent with children (the

Ancestors) inside her. It was All-mother who made water for the

Ancestors by urinating on the land, creating lakes, rivers and water

holes to quench their thirst. The "living water" (running

water) of springs and natural fountains is particularly associated in

ancient mythological systems with women, fertility and childbirth.

Greek wells and fountains were sacred to various goddesses and had miraculous powers – such as the fountain at Kanathos, in which

Hera regained her virginity each year. Greek springs were the haunts

of water nymphs, elemental spirits shaped like lovely young girls.

(The original meaning of the Greek word for spring was "nubile

maiden.") In Teutonic myth, the wild wood-wife (a kind of forest

fairy) who loves the hero Wolfdietrich is transformed into a human

girl when she's baptized in a sacred fountain. The Norse god Odin

seeks wisdom and cunning from the fountain of the nature spirit

Mimir; he sacrifices one of his eyes in exchange for a few precious

sips of the water. In Celtic legend, the salmon of knowledge swims in

a sacred spring or pool under the shade of a hazel tree; the falling

hazelnuts contain all the wisdom of the world, swallowed by the fish.

Ritual washing in

water, or immersion in a pool, has been part of various religious

systems since the dawn of time. The priests of ancient Egypt washed

themselves in water twice each day and twice each

night; in Siberia, ritual washing of the body — accompanied by

certain chants and prayers — was (and still is) a vital part of shamanic practices. In

Hindu, ghats are traditional sites for public ritual

bathing, an act by which one achieves both physical and spiritual

purification. In strict Jewish household, hands must be washed before

saying prayers and before any meal including bread; in Islam, mosques

provide water for the faithful to wash before each of the five daily

prayers. In the Christian tradition, baptism is described by St. Paul

as "a ritual death and rebirth which simulates the death and

resurrection of Christ." According to mythologist Mircea Eliade,

"Immersion in water symbolizes a return to the pre-formal, a

total regeneration, a new birth, for immersion means a dissolution of

forms, a reintegration into the formlessness of pre-existence; and

emerging from the water is a repetition of the act of creation in

which form was first expressed."

The idea of

regeneration through water is echoed in tales around the world about

fountains and springs with miraculous powers. Indigenous stories in

Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Hispaniola all described a magical

Fountain of Youth, located somewhere in the lands to the north. So

pervasive were these stories that in the 16th century the Spanish

conquistador Ponce de Leon actually set out to find it once and for

all, equipping three ships at his own expense. He found Florida

instead.

One Native American story describes a Fountain of Youth

created by two hawks in the nether-world between heaven and earth --

but this fountain brings grief as those who drink of it outlive their

children and friends, and eventually it's destroyed. In Japanese

legends, the white and yellow leaves of the wild chrysanthemum confer

blessings from Kiku-Jido, the chrysanthemum boy who dwells by the

Fountain of Youth. These leaves are ceremonially dipped in sake to

assure good health and long life. In the Alexander Romances,

Alexander sets off to find the fabled Fountain of Life in the Land of

Darkness beyond the setting sun. The prophet Khizr is Alexander’s

guide, but the two take separate forks in the road. It is Khizr, not

his master, who finds the fountain, drinks the water, and obtains

knowledge of god. Khizr is still venerated in modern India, in both

Hindu and Muslim traditions. In Muslim practices, Khizr is honored by

lighting lamps and setting them on little boats afloat on rivers and

ponds. In fairy tales, heroes are sent to the snake-guarded Well at the End of the World, or a spring in darkest part of the forest, to retrieve a vial of the Water of Life. A few drops from this water confers beauty, wisdom, fluency in the language of animals, or immortality.

To the ancient

peoples of the West Country, certain waters were deemed to have

healing properties and thus were under divine protection. The famous

hot spring at Bath in Somerset (the county just to the east of Devon) was dedicated to a Celtic goddess local to the place. When the Roman's took the hot springs over and built the temple complex we know today, Sulis was linked with their goddess Minvera to become Sulis Minerva. Chalice Well

in Glastonbury, also in Someset, is reputed to be among the oldest of continually used

holy wells in all of Europe; archaeological evidence suggests it has been a

sacred site for at least two thousands years. Even the standing stones and

circles of Britain are generally found near wells or running water.

As Christianity spread, more and more springs were built over with chapels and well houses, and the groves around them removed. Devon and Cornwall, in particular, were deemed to be troublesome bastions of paganism. In the 5th

century, a canon issued by the Second Council of Arles stated: "If in the territory of a bishop infidels light

torches or venerate trees, fountains, or stones, and he neglects to

abolish this usage, he must know that he is guilty of sacrilege." Yet pagan beliefs proved

harder to eradicate than the sites themselves, for

in the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries a stream of edicts were issued

from church authorities denouncing the worship of "the sun or the moon, fire or flood,

wells or stones or any kind of forest tree."

Over time, however,

pagan and Christian practices slowly blended together, and holy wells all over Great Britain were celebrated with Christian festivals that fell on the

old pagan holy days. On the Isle of Man, for example, holy

wells are frequented on August 1st, a day sacred to the Celtic god Lugh. August 1st is Lammas in the

Christian calendar, but the older name for the holiday, Lugnasad, was still in

use on the island until late in the 19th century. In Scotland, the well

at Loch Maree is dedicated to St. Malrubha but its annual rites --

involving the sacrifice of a bull, an offering of milk poured on the ground, and coins

driven into the bark of a tree -- are pagan in origin. The

custom of "well dressing" is another Christian rite with

pagan roots. During these ceremonies (still practiced in Derbyshire

and other parts of Britain), village wells are decorated with

pictures made of flowers, leaves, seeds, feathers and other natural

objects. In centuries past, the wells were "dressed" to

thank the patron spirit of the well and request good water for the

year to come; now the ceremonies generally take place on Ascension

Day, and the pictures created to dress the wells are biblical in

nature.

The Christian tales attached to springs and wells are often as magical as

The Christian tales attached to springs and wells are often as magical as

any to be found in Celtic lore. Wells were said to have sprung up

where saints were beheaded or had fought off dragons,

or where the Virgin Mary appeared and left small footprints pressed

into the stone. Over the Channel in Brittany (which has linguistic and mythic connections to the West Country) "granny wells" dedicated to St. Anne (so called bcause Anne was the mother of Mary, and therefore the

grandmother of Christ) were attributed with particular powers

concerning fertility and childbirth. According to one old Breton legend,

St. Anne settled there in her old age, where she was visited by Christ before she died. She asked him for a holy well to help the sick

people of the region; he struck the ground three times, and the

well of St. Anne-e-la-Palue was created.

Up until the 19th century,

the holy wells of the West Country were still considered to have

miraculous properties, and were visited by those seeking

cures for disease, disability, or mental illness. Some wells

were famous for offering prophetic information — generally determined

through the movements of the water, or leaves floating upon the

water, or fish swimming in the depths. At some wells, sacred water was drunk from circular cups carved out of animal bone (an echo

of the cups carved out of human skulls by the ancient Celts). Pins

(usually bent), coins, bits of metal, and flowers are common well offerings; and rags

(called clouties) are tied to nearby trees, the cloth representing disease or misfortune left behind as one departs.

Some wells, known

as cursing wells, were rather less beneficent. The curses were made by

dropping special cursing stones into the well, or the victim's name

written on a piece of paper, or a wax effigy. At the famous  cursing

cursing

well of Ffynnon Elian, up in Wales, one could arrange for a curse by

paying the well's guardian a fee to perform an elaborate cursing

ritual. A curse could also be removed at this same well, for a

somewhat larger fee.

In the mid-19th

century, Thomas Quiller-Couch (father of Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch) became interested in the history of holy wells; he spent much of his life wandering the

wilds of his native Cornwall seeking them out. Extensive notes on

this project were discovered among his papers after his death, and in

1884 The Ancient and Holy Wells of Cornwall was published by

the antiquarian's daughters, Mabel and Lillian.

More recently, folklorist Paul Broadhurst re-visited

the sites documented by Quiller Couch, and in 1991 he published

Secret Shrines: In Search of the Old Holy

Wells of Cornwall, an informative guide to the many wells

still to be found in the Cornish countryside.

In addition to sites dedicated to Celtic goddesses and Christian saints, Broadhurst

discovered crumbling old wells half-buried in ivy, bracken and briars

inhabited by spirits somewhat less exalted: the piskies (fairies) of

Cornish folklore. Wells under the protection of the piskies are not

wells to be trifled with, for the piskies will take their revenge on

any who dare to disturb their homes. A farmer decided to move the

stone basin at St. Nun's Well (also known as Piskey's Well), with the

intention of using it as a water trough for his pigs. He chained the

stone to two oxen and pulled it the top of a steep hill — whereupon

the stone broke free of the chains, rolled downhill, made a sharp

turn right, and settled back into its place. One of the ox died on

the spot, and the farmer was struck lame.

All running water,

not just spring water, can prove to be the haunt of fairies, for

crossing over (or through) running water is one of the ways to enter

their realm. Here in Devon and Cornwall, one still finds country folk

who avoid running water by dusk or dark -- for the spirits who

inhabit water can be troublesome, even deadly. The water spirit of

the River Dart, for instance, is believed to demand sacrificial

drownings, leading  to the well-known local rhyme "Dart, Dart,

to the well-known local rhyme "Dart, Dart,

cruel Dart, every year she claims a heart." The water-wraithe of

Scotland is thin, ragged, and invariably dressed in green, haunting

riversides by night to lead travelers to a watery death. In the

Border Country between Scotland and England, the Washer by the Ford

wails as she washes the grave clothes of those who are about to die;

this frightening apparition is similar to the dreaded Bean-Sidhe

(Banshee) of Irish legends. The Bean-nighe is a similar creature

found in both Highland and Irish lore, a dangerous little faerie with

ragged green clothes and webbed red feet. (Yet if one can get between

the Bean-nighe and her water source, she is obliged to grant three

wishes and refrain from doing harm.) Jenny Greenteeth specializes in

dragging children down in stagnant pools. The Welsh water-leaper

(Llamhigyn Y Dwr) is a toad-like creature who delights in tangling

fishing lines and devouring any sheep who fall into the river. The

fideal is a fairy who haunts lonely pools and hides herself in the

grasses by the water; the glaistig, half-woman and half-goat, tends

to lurk in the dark of caves behind waterfalls. The loireag of the

Hebrides is a gentler breed of water fairy, although — as a

connoisseur of music — even she can prove dangerous to those who

dare to sing out of tune. In Ireland, the Lady of the Lake bestows blessings and good

weather to those who seek her favor; in some towns she is still

celebrated (or propitiated) at mid-summer festivals. Her name recalls

the Lady of the Lake of Arthurian lore, who gave King Arthur his sword and now

guards his body as he sleeps in Avalon.

Chalice Well in Glastonbury is one of several sites

where the Holy Grail is reputed to be hidden. At the foot of ancient

Glastonbury Tor is a lovely garden where one can drink the red-tinged

water of well — colored, according to legend, by the blood of

Christ carried in the Grail. Although the well's association with

Arthur may be (as some Arthurian scholars suggest) a legend of recent

vintage, archaeological excavations in the 1960s established the

site's antiquity — and the place manages to retain a tranquil,

mystical atmosphere despite now doing dual duty as a sacred site and a tourist attraction. One often finds small offerings in the circle

around the well's heavy lid: flowers, feathers, stones, small bits of

cloth tied to a near-by tree . . . the old pagan ways still quietly practiced by many people to this day.

In North America, numerous springs, wells, and pools are sacred to land's First Nations. In such holy places one also finds

offerings similar to those by Chalice Well: feathers, flowers,

stones, sage, tobacco, small carved animal forms, scraps of red cloth

tied to trees, and other tokens of prayer. The Native American

sweat-lodge ceremony uses water sprinkled over red-hot rocks to create the steam

that is called the "breath of life"; the lodge itself is

the womb of mother earth in which one is washed clean, purified and

spiritually reborn. In Native American Church ceremonies, a pail of Morning Water is traditionally carried and prayed over by a

woman before being sent sun-wise around the circle to be shared by

all. Water is sacred through its absence in the four-day Sundance

ceremony, or the ritual of Crying for a Vision; after four days

without water (or food), the first drop on the tongue is a potent

reminder to be thankful for this precious gift from mother earth.

Some years ago at the Mythic Journeys conference in Atlanta, Tom Blue Wolf of

Some years ago at the Mythic Journeys conference in Atlanta, Tom Blue Wolf of

the Eastern Lower Muscogee Creek Nation spoke of the need to cherish the wild waters of our lands -- particularly now, as water tables

world-wide diminish at alarming rates. “Once upon a time,” he

said, “the Chattahoochee River was known to the people here as the

source of life. Every morning we would go to the water and fill

ourselves with gratitude, and thank the Creator for giving us this

source of life. We would honor it throughout the day. At that time,

water was known as the Long Man. It came from a place that has no

beginning, and goes to a place that has no end. But now, for the

first time in the history of our people, we can see the end of

water.”

At the same conference, mythologist Michael

Meade spoke of the ancient symbolism of water and its mythic

role in our lives today. “Of the elements (which some people count

as four, and others count as five), water is the element for

reconciliation. Water is the element of flow. When water goes

missing, flow goes missing. The ancient Irish used to say that there

are two suns in the world. One you see rise in the morning. The other

is very deep in the earth, and it’s called the black sun or inner

sun. It’s a hot fire in there; no one knows how hot. The earth is

roughly seventy per cent water because of that hidden sun inside.

When the water goes down, the earth heats up too much – part of the

global warming that’s happening everywhere. It happens inside

people also, because people are like the earth. People are seventy

per cent water like the earth, and people have a hidden sun – or

else we wouldn’t be ninety-six degrees when its forty degrees

outside. Everyone in the world is burning, and the water in the body

keeps that burning from becoming a fever. What happens literally also

happens emotionally and spiritually, so when people forget how to

carry water and how to use water to reconcile, you get an increasing

amount of heated conflict, as we’re seeing around the world today.

…In many cultures it’s the elders who carry the water, because

elders are the peace-bringers. When a culture can’t remember or

imagine peace on its streets or how to negotiate peace. it means its

elders have forgotten what to do, how to carry water.”

I'll give Margaret Atwood the last words today, from her lovely mythic novel The Penelopiad. They are words that rustle like wind in my ears as Tilly and I follow the cold, clear stream winding through our our own beloved piece of woods:

"Water does not resist. Water flows. When you plunge your hand into it, all you feel is a caress. Water is not a solid wall, it will not stop you. But water always goes where it wants to go, and nothing in the end can stand against it. Water is patient. Dripping water wears away a stone. Remember that, my child. Remember you are half water. If you can't go through an obstacle, go around it. Water does.”

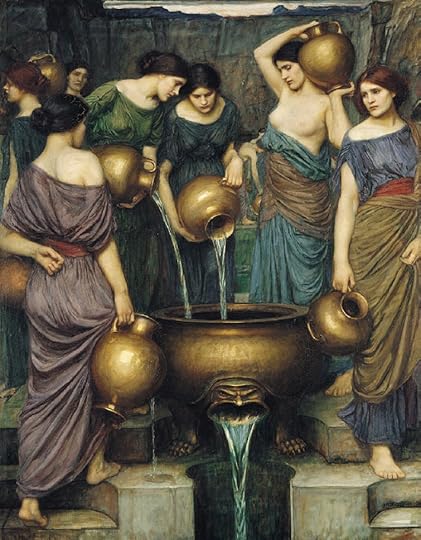

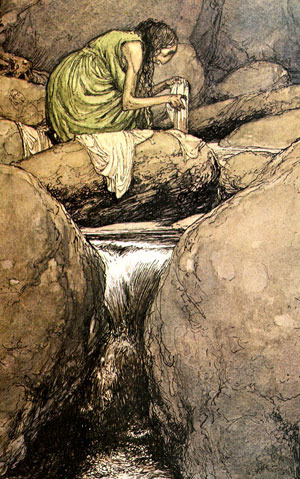

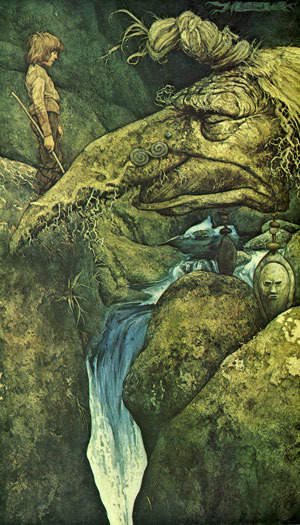

Art above: Wendy as "Lady of the Waters" by Brian Froud, "Circe Invidiosa" and "The Danaides" by John William Waterhouse, a water faery by Brian Froud, a Bean-nighe by Alan Lee, "Arthur in Avalon" and "The Last Sleep of King Arthur" by Sir Edward Burne-Jones.

The photographs of wells, springs, and baths above come from various British heritage sites. Please look in the picture captions for identifcation. (Run your cursor over the pictures to see the captions.) For more photographs of the wells of the West Country, go here. There's also a lovely post about The Well of St. John's in the Wilderness by the late (and much-missed) folklorist Thomas Hine on the Westcountry Folklore site.

Text for this post has been adapted from three previous articles of mine published in: Folkroot, JoMA, and Masaru Emoto's The Healing Power of Water .

June 12, 2013

Into the Woods, 10: Wild Neighbors

"What would Robin Hood have made of Country Life's

recent excavation into the fantasies of British 7-to-14-year-olds

concerning the wild life and wild places of their native land?" asks poet and scholar Ruth Padel.

"Two thirds had no idea where acorns come from, most had never heard

of gamekeepers (do they  mug people or protect the Pokemons?), and most

mug people or protect the Pokemons?), and most

believed there were elephants and lions running round the English

countryside. A third did not know why you had to keep gates

shut — was it to keep the elephants in (or was some joker taking

the piss just then?), or stop cows 'sitting on cars,' upsetting the

countryside's most vital beast — the traffic?

"In a closed, traditional society there is something special about

animals born in the land where you, too, were born. The British used to

look lazily at gardens, thickets, and moors, and know — without

bothering to think about it — that foxes, hedgehogs, badgers, squirrels,

and deer were out there flecking the undergrowth....

"Dangerous or vulnerable, shy or cunning, a pest or welcome visitor, our

native animals are part of our romance with the secret wildness of the

place we live, even if we never see much of them. We grew up with them

in imagination. They were inside us, furry heroes of nursery rhymes,

pictures and stories through which we learned the world. Little Grey

Rabbit. The Stoats and Weasels of the Wild Wood. The Fox who Looked Out

on a Moonlight Night. The Frog who would A Wooing Go. They are deep in

British folk song, poetry, and popular art. 'Three Ravens Sat in an Old

Oak Tree.' The holly and the ivy, the running of the deer. Landseer's 'Monarch of the Glen.'

"But that's the way it used to be. We are not a mono–traditional

society any more — most kids' traditions center on the TV and the city

street. To most children, a weasel is as unknowable as daffodils to a

young Indian struggling with Wordsworth during the Raj."

How did we become so disconnected to the land we live on, and the wild neighbors we share it with? I think it's partly because we're losing the stories specific to the local landscape: the stories about this plant that grows on the hill nearby and that bird that migrates here each spring and not just the pan-cultural stories we share with everyone on the television and cinema screens. We no longer know the tales of the animals, and, increasingly, we no longer know animals themselves.

What a different attitude is conveyed by these words from a member of the Carrier Indian nation in British Columbia (quoted in Becoming Animal by David Abram):

"We know what the animals do, what are the needs of the beaver, the bear, the salmon, and other creatures, because long ago men married them and acquired this knowledge from their animal wives. Today the priests say we lie, but we know better. The white man has only been a short time in this country and knows very little about the animals; we have lived here thousands of years and were taught long ago by the animals themselves. The white man writes everything down in a book so it will not be forgotten; but our ancestors married animals, learned their ways, and passed on this knowledge from one generation to another."

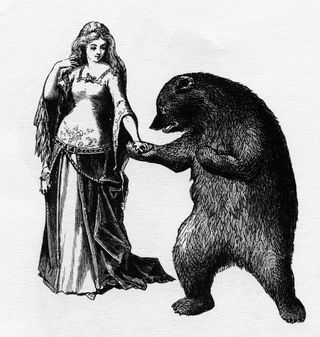

The old story of a woman who marries a bear, for example, is one that used to roam widely, like the bears themselves, throughout North America. In a Nishga version recounted by Agnes Haldane of the Wolf clan

of Gitkateen (in Wisdom of the Myth Tellers by

Sean Kane), a tribal princess picking berries in the forest steps on a

bit of bear scat and mutters angry remarks about the bears. As the women

head for home, her basket breaks; repairing it, she is left behind. Two

handsome men appear and tell her they've come to fetch her and lead her

from the forest. Instead of leading her home, they take her to the

village of the Bear People. The princess tricks the People into

believing she is a woman of great power, and as a result she ends up

marrying the son of the Bear Chief. She lives with him rather happily,

and gives birth to two fine bear sons. But during a period of

hibernation, her own brothers find her husband's cave and kill the bear

in a rescue attempt. Her husband has foreseen this event. "When they

skin me," he'd instructed her, "tell them to burn my bones so that I may

go on to help my children. At my death they shall take human form and

become skillful hunters. Now listen as I sing my dirge song. This you

must remember and take to your father. My cloak he shall don as his

dancing garment. His crest shall be the Prince of Bears."

The bear's sacrifice of his life for the benefit of human beings might seem suprising, but it's not an unusual theme in the indiginous tales of North America, where many story traditions say the animals were the

First People, here before humans came. Sacred tales from many different Indian nations recount how Bear, or Coyote, or Eagle, or Deer first gave humans the precious, vital gift of fire -- while in other tales language,

hunting skills, dancing, even love-making, were first taught by the animals. Though we've

come to expect such respectfulness towards and from other species in American Indian lore, it can also be found in many other storytelling traditions around world -- such as in the sacred stories of the Ainu of Japan. As Gary Snyder notes (in The Practice of the Wild):

"In the Ainu world, a few human houses are in a valley by a little river.

Food is often foraged in the local area, but some of the creatures come

down from the inner mountains and up from the deeps of the sea. The

animal or fish (or plant) that allows itself to be killed or gathered,

and then enters the house to be consumed, is called a 'visitor,'

marapto. Bear sends his friends the deer down to visit humans. Orca [the

Killer Whale] sends his friends the salmon up the streams. When they

arrive their 'armor is broken' -- they are killed -- enabling them to shake

off their fur or scale coats and step out as invisible spirit beings.

They are then delighted by witnessing the human entertainments -- sake and

music. (They love music.) Having enjoyed their visit, they return to the

deep sea or the inner mountains and report, 'We had a wonderful time

with the human beings.' The others are then prompted themselves to go on

visits. Thus if the humans do not neglect proper hospitality, the

beings will be reborn and return over and over."

In another essay in the same volume, Snyder writes: "A young white woman asked me: 'If we have made such good use of

animals, eating them, singing about them, drawing them, riding them, and

dreaming about them, what do they get back from us?' An excellent

question, directly on the point of etiquette and propriety, and putting

it from the animals' side. The Ainu say that the deer,

salmon, and bear like our music and are fascinated by our languages. So

we sing to the fish or the game, speak words to them, say grace.

Periodically we dance for them. A song for your supper: performance is

currency in the deep world's gift economy. The other creatures probably

do find us a bit frivolous: we keep changing our outfits and we eat too

many different things. Nonhuman nature, I can't help feeling, is well

inclined towards humanity and only wishes that modern people were more

reciprocal, not so bloody."

The idea that animals love human song reminds me of this passage from Linda Hogan's gorgeous novel Power:

'[T]he panther remembers when humans were so beautiful and whole that her own people envied them and wanted to be like them. They admired the humans and the way the two-legged people stood beneath trees with leaves leaning down over them as they picked ripe fruits, how their beautiful eyes were fully open. How straight they walked! How beautiful the beads about their necks, the dresses women made in fabric that was the dark green of the trees and the light colors of flowers. How intelligent the little shell and wooden bowls they ate from, how good they were at devising ways to catch fish with simple bone and metal, at making trails through the thickets. They stood so gracefully and full of themselves, they sang so beautifully; it remembers all this, how they sang. The whole world rejoiced with their voices....

"[The panther] remembers when its own people surrounded the humans and gave them life and power, medicine to heal, to hunt, even to direct lightning and stormclouds away from their beautiful dark-eyed children....But now they have turned against her. Now that they have no need for her, Sisa and her people, the panther, are leaving. They leave in sadness and grief. Now so few of the humans have songs or presence, so many have such heaviness that they can barely walk or move, raise themselves from their beds in the morning. And Sisa believes, sees, that the world could end with their human misery."

And in Wild: An Elemental Journey (another book that I highly recommended), Jay Griffiths shares this:

"Creatures are gente, I'm told, everywhere I go in the Amazon:

they are 'people like us' with customs and homes and they are accorded

gentleness for being gente. You must address the world gently, I was

told, even to the wind you should speak con cariño -- with tenderness.

The Harakmbut say that all animals were people más allá -- long ago -- and

there is therefore a profound equality between us and them; they are

like distant family, and one has duties and expectations as one would

with family members. People are 'familiar' with the habits and ways of

animals, and this familarity is cherished. (By contrast in the West,

close familiarity with animals was considered devilish: the witch and

her 'familiar.')

"Animals should be treated kindly, even in hunting,

for they are kin to humans. 'We owe...kindliness to other creatures:

there is an intercourse and mutual obligation between then and us,'

wrote Michel de Montaigne, sounding uncannily like an Amazonian Indian."

"Homo sapiens," wrote the late naturalist Ellen Meloy (in Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild) "have left themselves few scant places and scant ways to witness other species in their own world, an estangement that leaves us hungry and lonely. In this famished state, it is no wonder that when we do finally encounter wild animals, we are quite surprised by the sheer truth of them."

Louise Erdrich portrays this sense of surprise in a passage from her novel The Painted Drum:

“Coming down off the trail, I am lost in my own thoughts and

unprepared when a bear chugs across the path just before it gives out on

the gravel road. I am so distracted that I keep walking towards the

bear. I only stop when it rears, stands on hind legs, and stares at me,

sensitive nose pressed into the air, weak eyes searching. I have never

been this close to a wild bear before, but I am not frightened. There is

no menace in its stance; it is not even curious. The bear seems to know

who or what I am. The bear is not impressed. ”

No, I don't expert that the bear would be impressed with many of us these days, nor the bees and badgers, the hares and hedgehogs and other wild folk here in the hills of Devon. We don't know their stories any longer. We've forgotten their songs. We don't "stand with presence."

No, I don't expert that the bear would be impressed with many of us these days, nor the bees and badgers, the hares and hedgehogs and other wild folk here in the hills of Devon. We don't know their stories any longer. We've forgotten their songs. We don't "stand with presence."

In From the Beast to the Blonde, Marina Warner

discusses the role of "beasts" in fairy tales, and how our perceptions

of these stories have changed as attitudes towards animals have changed.

"Just as the rise of the teddy bear matches the decline of real bears in

the wild," she notes, "so soft toys today have taken the shape of rare

animal species. Some of these are not very furry in their natural state:

stuffed killer whales, cheetahs, gorillas, snails, spiders and snakes

-- and of course dinosaurs -- are made in the most inviting deep-pile

plush. They act as a kind of totem, associating the human being with the

animal's capacities and value. Anthropomorphism traduces the creatures

themselves; their loveableness sentimentally exaggerated, just as

formerly, belief in their viciousness crowded out empircal observation."

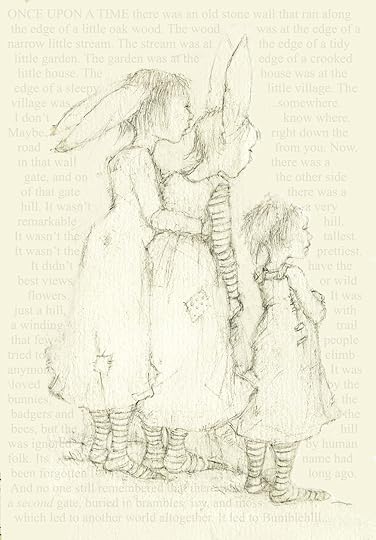

This is clearly true, and a world in which children interact only with animal-shape-objects while remaining ignorant about the creatures outside their own back door (be it country badger or urban fox) is clearly a world out of balance. And yet, for me, those soft animal toys awakened my interest in and life-long love of the wild, as did the anthropomorphised animals of tales like Peter Rabbit, Winnie the Pooh, and Wind and Willows. I'm thinking quite a lot about this these days, as I work on a book project involving bunny girls and other animal children. I want these magical beings to lead children back to nature, not to be nature's safe, cuddly substitute. Is this possible? At this point in the process, I have more questions than I have answers....

When I think back to my own childhood, what I wish is that someone had noted my passion for animals and placed a wildlife guide in my hands alongside those tales of Mole and Rat and Benjamin Bunny...or better still, led me out of doors and into the wild, and told tales of the land we then lived on. Not in place of those books, which had done their work in opening the door into wonder for me, but as the next necessary step of attaching wonder to the living world around us.

"How, then to renew our viceral experience of a world that exceeds us -- of a world that is wider than ourselves and our own creations?" asks David Abram (in Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology). "Does a revitalizing of oral [storytelling] culture mean that mean that we must renounce reading and writing? Must we empty our bookcases? Must we unplug our computers and drag them down to the dump?

"Hardly," David answers. "The renewal of oral culture entails no renunciation of books, and no rejection of technology. It entails only that we leave abundant space in our days for interchange with one another and with our surroundings that is not mediated by technology: neither by television nor the cell phone, neither by the handheld computer or the GPS satellite...nor even the printed page.

"Among writers, for example, it entails a

recognition (even an anticipation) that there are certain stories we may

stumble against that ought not to be written down -- stories that we

might instead begin to tell with our tongue in the particular topography

where those stories live. Among parents, it requires that we set aside,

now and then, the books that we read to our children in order to

recount a vital story with the whole of our gesturing body -- or better

yet, that we draw our kids out of doors in order to improvise a tale

about how the nearby river feels when the fish return to its waters, or

about the wild wind that's even now blustering its way through the city

streets, plucking the hats off people's heads...Among educators, it

requires that we begin to rejuvenate the arts of telling, and of

listening, in relation to the geographical place where our lessons

actually happen."

"Can we renew in ourselves an implicit sense of the land's meaning, of it's own many-voice eloquence?" Dave wonders. "Not without renewing the sensory craft of listening, and the sensuous art of storytelling. Can we help our students to carefully translate the quantified abstractions of science into the qualitative language of direct experience, so that those necessary insights begin to come alive in their felt encounters with cumulus clouds and bleaching corals, with owls and deformed dragonflies and the intricate tangle of mycelial mats? ...Most important, can we begin to restore the health and integrity of the local earth? Not without restorying the local earth."

"We

are of the animal world," Linda Hogan reminds us (in her beautiful collection of essays, Dwelling: A Spiritual History of the Living World). "We are part of the cycles of growth and decay.

Even having tried so hard to see ourselves apart, and so often without a

love for even our own biology, we are in relationship with the rest of

the planet, and that connectedness tells us we must reconsider the way

we see ourselves and the rest of nature.

"A change is required of

us, a healing of the betrayed trust between humans and earth. Caretaking

is the utmost spiritual and physical responsibility of our time, and

perhaps that stewardship is finally our place in the web of life, our

work, our solution to the mystery of what we are."

Indeed. Part of that stewardship, surely, is caretaking our local, traditional stories as well as the land that gave birth to them. And listening for the land's new stories. Telling them. And singing, so the animals can hear us.

The photographs above, of our four-footed and winged neighbors here in Devon, come from the Devon Wildlife Trust website. The art above: "Ratty" by my two-footed neighbor Steve Dooley (from the enchanting new Wind and the Willows for iPad); "Woman & Bear," a Victorian illustration (artist unknown); Peter Rabbit by the great Beatrix Potter; and my wee Rabbit Sisters.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 707 followers