Terri Windling's Blog, page 190

May 23, 2013

I'm away today, as it's the start of a long holiday w...

I'm away today, as it's the start of a long holiday weekend here in the UK. I'll be back at my desk, and back to the "Into the Woods" series of posts, on Tuesday, May 28. Have a good weekend, everyone.

“I want so to live that I work with my hands and my feeling and my brain. I want a garden, a small house, grass, animals, books, pictures, music. And out of this, the expression of this, I want to be writing. (Though I may write about cabmen. That’s no matter.) But warm, eager, living life — to be rooted in life — to learn, to desire, to feel, to think, to act. This is what I want. And nothing less.” ― Katherine Mansfield

Amen.

I'm away today. I'll be back at my desk, and back to ...

I'm away today. I'll be back at my desk, and back to the "Into the Woods" series of posts, next week. Have a good weekend, everyone.

“I want so to live that I work with my hands and my feeling and my brain. I want a garden, a small house, grass, animals, books, pictures, music. And out of this, the expression of this, I want to be writing. (Though I may write about cabmen. That’s no matter.) But warm, eager, living life — to be rooted in life — to learn, to desire, to feel, to think, to act. This is what I want. And nothing less.” ― Katherine Mansfield

Amen.

Into the Woods, 6: The Dark Forest

"In the mid–path of my life, I woke to find myself in a dark wood," writes Dante in The Divine Comedy,

beginning a quest that will lead to transformation and redemption. A

journey through the dark of the woods is a motif common to fairy tales:

young heroes set off through the perilous forest in order to reach

their destiny, or they find themselves abandoned there, cast off and

left for dead. The path is hard to find and treacherous, prowled by wolves,

ghosts, and wizards...but helpers, too, appear along the way: good

fairies, wise elders, and animal guides, usually cloaked in unlikely disguises. The hero's task is to tell

friend from foe, and to keep walking steadily onward.

The Dark Forest is not the merry greenwood of Robin Hood legends, or a Disney glade where dwarves whistle as they work, or a National Park with walkways and signposts and designated camping sites; it's the forest primeval, true wilderness, symbolic of the deep, dark levels of the psyche; it's the woods where giants will eat you and pick your bones clean, where muttering trees offer no safe shelter, where the faeries and troll folk are not benign. It's the woods you may never come back from.

"The woods enclose," writes Angela Carter (in The Bloody Chamber). "You step between the fir trees and then you are no

longer in the open air; the wood swallows you up. There is no way

through the wood anymore; this wood has reverted to its original

privacy. Once you are inside it, you must stay there until it lets you

out again for there is no clue to guide you through in perfect safety;

grass grew over the tracks years ago and now the rabbits and foxes make

their own runs in the subtle labyrinth and nobody comes.... "

"I stood in the wood," Patricia McKillip tells us (in Winter Rose). "Now it was a grim and shadowy tangle of thick dark

trees, dead vines, leafless branches that extended twig like fingers to

point to the heartbeat of hooves. The buttermilk mare, eerily, eerily

pale in that silent wood, galloped through the trees;  tree boles turned

tree boles turned

toward it like faces. A woman in her wedding gown rode with a man in

black; he held the reins with one hand and his smiling bride with the other. She wore lace from throat to heel; the roses in her chestnut hair

glowed too bright a scarlet, mocking her bridal white…When they

stopped, her expression began to change from a pleased, astonished

smile, to confusion and growing terror. What twilight wood is this? she

asked. What dead, forgotten place?"

The goblins of the glen, in Christina Rossetti 's great poem "Goblin Market," are thoroughly dangerous creatures. When young Laura buys but will not eat

their fruit...

"Lashing their tails

They trod and hustled her,

Elbow’d and jostled her,

Claw’d with their nails,

Barking, mewing, hissing, mocking,

Tore her gown and soil’d her stocking,

Twitch’d her hair out by the roots,

Stamp’d upon her tender feet,

Against her mouth to make her eat."

To know the woods and to love the woods is to embrace it all, the light and the dark -- the sun dappled glens and the rank, damp hollows; beech trees and bluebells and also the deadly fungi and poison oak. The dark of the woods represents the moon side of life: traumas and trials, failures and secrets, illness and other calamities. The things that change us, temper us, shape us; that if we're not careful defeat or destroy us...but if we pass through that dark place bravely, stubbornly, wisely, turn us all into heroes.

"The sense of secrets, silence, surprises, good and bad, is fundamental to forests and informs their literatures," notes Sara Maitland (in Gossip from the Forest). "In fairy stories this is sometimes simple and direct: Hansel and Gretel get lost in the woods, and then suddenly they come upon the gingerbread house. Snow White runs in terror through the forest and suddenly stumbles upon the dwarves' cottage; characters spending scary nights in or under trees suddenly see a twinkling light -- and they make their laborious way towards it without having any idea what they will find when they arrive.....

"The forest is about concealment and appearances are not to be trusted. Things are not necessarily what they seem and can be dangerously deceptive. Snow White's murderous stepmother is truly the 'fairest of them all,' The wolf can disguise himself as a sweet old granny. The forest hides things; it does not open them out but closes them off. Trees hide the sunshine; and life goes on under the trees, in thickets and tanglewood. Forests are full of secrets and silences. It is not strange that the fairy stories that come out of the forest are stories about hidden identities, both good and bad."

Appearance deceive in the dark of the woods. You must beware of the helpful wolf by the path, of the beautiful woman who asks for a kiss, of the cozy little house with its door standing open, a meal on the table, and its owner nowhere in sight. No

matter how tired you are, warns Lisel Mueller (in her poem "Voice from the Forest"), do not enter that house, do not eat the bread, do not drink the wine: "It is only when you finish eating and, drowsy and grateful, pull off your shoes, that the ax falls or the giant returns or the monster springs or the witch locks the door from the outside and throws away the key."

But if you must enter, Neil Gaiman advises (in his poem "Instructions"), be courteous. And wary. "A red metal imp hangs from the green–painted front door, as a knocker, do not touch it; it will bite your fingers. Walk through the house. Take nothing. Eat nothing."

Those last words are important. Folk tales from all over the world warn

that eating the food of a witch, a demon, a djinn, a troll, an ogre, or

the faeries can be a dangerous proposition. You might owe your youngest

child in return, or be bound to your host for the rest of your life.

Likewise, don't kiss the beautiful woman who offers you a meal and a bed

in her sumptuous chateau hidden deep in the woods. By morning light

she'll be a monster, and her house but a pile of rocks and bones.

And yet, despite all the fairy tale warnings, sometimes we're compelled to run to the dark of the woods, away from all that is safe and familiar -- driven by desperation, perhaps, or the lure of danger, or the need for change. Young heroes stray from the safe, well-trodden path through foolishness or despair...but perhaps also by canny premeditation, knowing that venturing into the great unknown is how lives are tranformed. When Gretel walks into the woods, writes Andrea Hollander Budy

(in her poem "Gretel," from The House Without a Dreamer),

"she means to lose everything she is. She empties her dark pockets,

dropping enough crumbs to feed all the men who have touched her or

wished." In Ellen Steiber's "Silver and Gold," Red Riding Hood is asked to explain how she failed to distinguish her grandmother from a wolf. "It's complicated," she answers. "Sometimes it's hard to tell the difference between the ones who love you and the ones who will eat you alive." But what she doesn't say is that if the wolf comes again, she will surely follow. Why? Carol Ann Duffy answers in her poem "Little Red-Cap" (from The World's Wife): "Here's why. Poetry. The wolf, I knew, would lead me deep into the

woods, away from home, to a dark tangled thorny place lit by the light

of owls." To the place of poetry and adventure. The place where the hard and perilous work of transformation begins.

Sara Maitland compares the transformational magic in fairy tales to the everyday magic that turns caterpillars into butterflies. "[S]omething very dreadful and frightening happens inside the chrysalis," she points out. "We use the word 'cocoon' now to mean a place of safety and escape, but in fact the caterpillar, having constructed its own grave, does not develop smoothly, growing wings onto its first body, but disintegrates entirely, breaking down into organic slime which then regenerates in a completely new form. It goes as a child into the dark place and is lost; it emerges as the princess, or proven hero. The forest is full of such magic, in reality and in the stories."

My husband uses the term the Dark Forest to refer that part of the art-making process when we've suddenly lost our way...when the creation of a story or a painting or (in his case) a play reaches a crisis point...when the path disappears, the idea loses steam, the plot line tangles, that palette muddies, and there is no way, it seems, to move forward. This often occurs, interestingly enough, right before true magic happens: first the crisis, then a breakthrough, an unexpected solution, and the piece comes to life. In a journal Howard wrote while creating a fairy tale play with students in Portugal he notes:

"Today I arrived in the middle of the Dark Forest, and the path has

almost disappeared. It is scary now, and all the certainties have gone. The cast

members are weary, and their ability to come up with interesting work

has diminished. Even our opening meditation today felt tired. The Dark Forest. I knew I was heading into it, and, as always, the

forest has its own way of manifesting in each creative project. Perhaps the students are getting stuck and are unable to develop their

parts. Perhaps it's that our storytelling has become flat, or that I'm

forgetting important, simple things, like the development of the boy's

character throughout the play.

Or maybe it's all of these things....

"It's

difficult to keep my original vision of the piece as I travel through the

forest. I have to trust the vision I had at the start of the work, and

that the ideas that have been set in motion will somehow come to

fruition. I know that I can't lose faith now, even though at this point

in the creative process one often starts to question the show, the cast,

and one's own ability.

"I can't turn around. I have to keep going, through this tough

period, and find energy from somewhere! I'm reminded of the first day of

the pilgrimage I took seven years ago, across the mountains of France

and Spain to Santiago de Compostela. I cycled up route Napoleon late in

the day, as the sun was setting, knowing that no matter how exhausted I

was I had to push on to Roncesvalles.

I could not turn back as I was too far along the path — but if I did

not get to the monastery before sundown, I would surely lose my way and

die of exposure in the Pyrenees. This is the feeling I have now: I'm

exhausted, I don't know when the turning point will come, but I have to

plough on."

So what should we do when we're in the Dark Forest, creatively or personally? Perservere. As Howard says, plough on. The gifts of the journey are worth the hardship, as writer & writing teacher Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew notes: (I've quote this passage before, but it's well worth repeating in this context.)

"When you enter the woods of a fairy tale," says Andrew, "and it is night, the trees

tower on either side of the path. They loom large because everything in

the world of fairy tales is blown out of proportion. If the owl shouts,

the otherwise deathly silence magnifies its call. The tasks you are

given to do (by the witch, by the stepmother, by the wise old woman) are

insurmountable -- pull a single hair from the crescent moon bear's

throat; separate a bowl's worth of poppy seeds from a pile of dirt. The

forest seems endless. But when you do reach the daylight, triumphantly

carrying the particular hair or having outwitted the wolf; when the owl

is once again a shy bird and the trees only a lush canopy filtering the

sun, the world is forever changed for your having seen it otherwise.

From now on, when you come upon darkness, you'll know it has dimension.

You'll know how closely poppy seeds and dirt resemble each other. The

forest will be just another story that has absorbed you, taken you

through its paces, and cast you out again to your home with its rattling

windows...."

And as Rainer Maria Rilke suggests (in his beautiful little book Letters to a Young Poet), "Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are

princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty

and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest

essence, something helpless that wants our love." Including the bears and the beasties, the fungi and faeries, the wolves and witches hidden in the deep forest...and the frightening, spell-binding, life-changing stories to be found only in the dark of the woods.

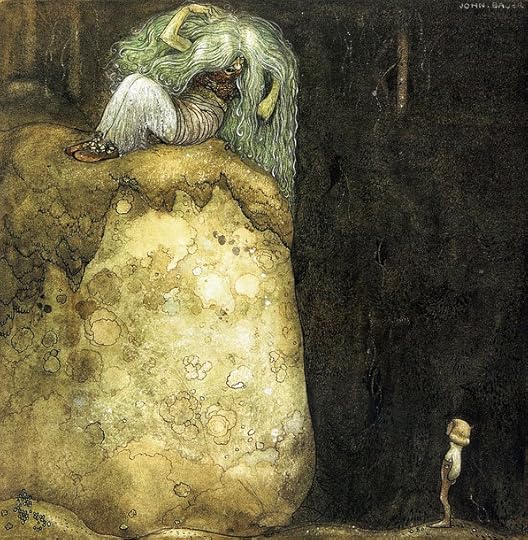

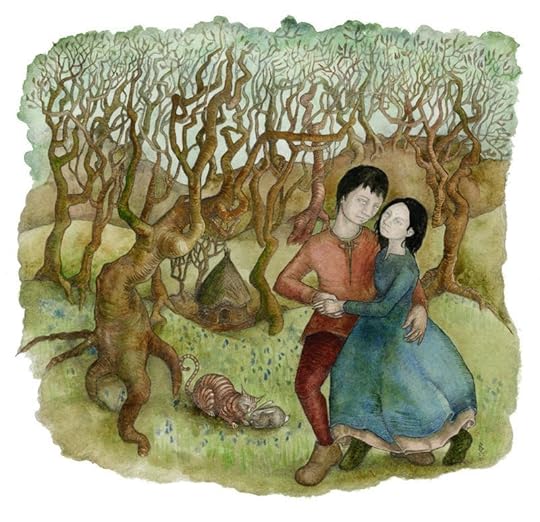

Art above: "Fur, Feather, Tooth and Nail" by Arthur Rackham, "The Faery Ring" by Alan Lee, two illustrations for Christina Rossetti's "Goblin Market" by Arthur Rackham, "Chase of the White Mouse" by John Anster Fitzgerald, "Goblins" by Brian Froud, "The Gingerbread House" by Trina Schart Hyman, "The Queen's Pearl Necklace" by John Bauer, "Hansel and Gretel" by Arthur Rackham, "The Lamb and the Serpent" by Arthur Rackham, "Little Red Riding Hood" by Richard Hermann Eschke, "The Briarwood" (from the Briar Rose series) by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, "Troll in the Wood" by John Bauer, and "She Kissed the Bear on the Nose" by John Bauer.

May 21, 2013

Into the Woods, 5: Wild Community

"Time and time again I am astounded by the regularity and repetition of

form in this valley and elsewhere in wild nature: basic patterns,

sculpted by time and the land, appearing everywhere I look. The twisted

branches in the forest that look so much like the forked antlers of the

deer and elk. The way the glacier-polished hillside boulders look like

the muscular, rounded bodies of the animals -- deer, bear -- that pass among

these boulders like loving ghosts. The way the swirling deer hair is

the exact shape and size of the larch and pine needles the deer hair

lies upon one it is torn loose and comes to rest on the forest floor. As

if everything up here is leaning in the same direction, shaped by the

same hands, or the same mind; not always agreeing or in harmony, but

attentive always to the same rules of logic and in the playing-out,

again and again, of the infinite variations of specificity arising from

that one shaping system of logic an incredible sense of community

develops . . .

. . . felt at night when you stand beneath the stars and see

the shapes and designs of bears and hunters in the sky; felt deep in the

cathedral of an old forest, when you stare up at the tops of the

swaying giants; felt when you take off your boots and socks and wade

across the river, sensing each polished, mossy stone with your bare

feet. Felt when you stand at the edge of the marsh and listen to the

choral uproar of the frogs, and surrender to their shouting, and allow

yourself, too, like those pine needles and that deer hair, like those

branches and those antlers, to be remade, refashioned into the shape and

the pattern and the rhythm of the land. Surrounded, and then embraced,

by a logic so much more powerful and overarching than anything that a

man or woman could create or even imagine that all you can do is marvel

and laugh at it, and feel compelled to give, in one form or another,

thanks and celebration for it, without even really knowing why."

- Rick Bass ("The Return," Orion Magazine)

“Ethics that focus on human interactions, morals that focus on

humanity's relationship to a Creator, fall short of these things we've

learned. They fail to encompass the big take-home message, so far, of a

century and a half of biology and ecology: life is -- more than anything

else -- a process; it creates, and depends on, relationships among

energy, land, water, air, time and various living things. It's not just

about human-to-human interaction; it's not just about spiritual

interaction. It's about all interaction. We're bound with the rest of

life in a network, a network including not just all living things but

the energy and nonliving matter that flows through the living, making

and keeping all of us alive as we make it alive."

― Carl Safina (The View from Lazy Point: A Natural Year in an Unnatural World)

“If you know wilderness in the way that you know love, you would be unwilling to let it go. We are talking about the body of the beloved, not real estate.” - Terry Tempest Williams

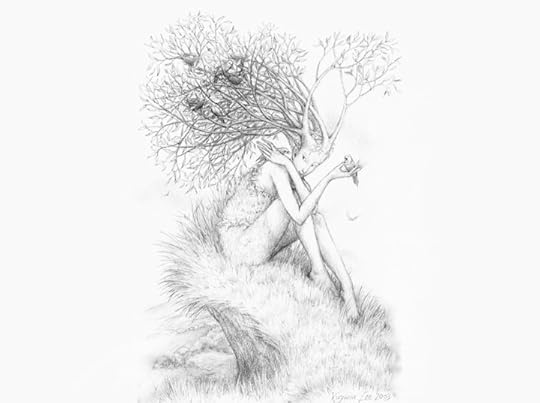

More art from the woods of Devon: "What He Didn't See" by Brian Froud, , woodland faery sculpture by Wendy Froud, woodland faery drawing by Alan Lee, "Imbolc" by Marja Lee Kruyt, "The Gidleigh Goat" by David Wyatt, Tilly among the roots, "Summer Land" by Virginia Lee, and "Bluebell Honeymoon" by Rima Staines.

More art from the woods of Devon: "What He Didn't See" by Brian Froud, , woodland faery sculpture by Wendy Froud, woodland faery drawing by Alan Lee, "Imbolc" by Marja Lee Kruyt, "The Gidleigh Goat" by David Wyatt, Tilly among the roots, "Summer Land" by Virginia Lee, and "Bluebell Honeymoon" by Rima Staines.

May 20, 2013

Into the Woods, 4: Wild Folklore

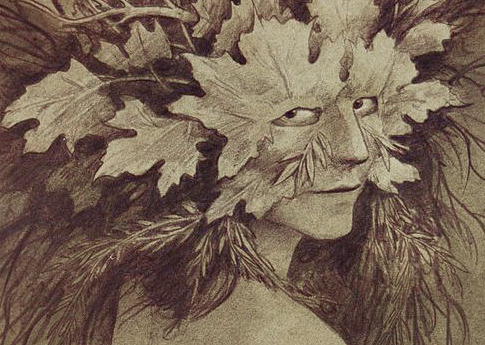

The Green Man is a pre–Christian symbol

found carved into the wood and stone of pagan temples and graves, of medieval

churches and cathedrals, and used as a Victorian architectural motif, across

an area stretching from Ireland in the west to Russia in the east. Although

commonly perceived as an ancient Celtic symbol, in fact its origins and

original meaning are shrouded in mystery. The name dates back only to 1939,

when folklorist Lady Raglan drew a connection between the foliate faces

in English churches and the Green Man (or "Jack of the Green")

tales of folklore. The evocative name has been widely adopted, but the legitimacy

of the connection still remains controversial, with little real evidence

to settle the question one way or the other. Earliest known examples of

the foliate head (as it was known prior to Lady Raglan) date back to classical

Rome — yet it was not until this pagan symbol was adopted by the Christian

church that the form fully developed and proliferated across Europe. Most folklorists conjecture that the foliate head symbolized mythic

rebirth and regeneration, and thus became linked to Christian iconography

of resurrection. (The Tree of Life, a virtually universal symbol of life,

death and regeneration, was adapted to Christian symbolism in a similar

manner.)

The Jack in the Green is a figure associated

The Jack in the Green is a figure associated

with the new growth of spring, fertility, and May Day celebrations. In a number of English towns (such as Hastings in East Sussex) the Jack pageant is still re-enacted each year. The Jack in the Green is played by a man in a towering eight–foot–tall costume of

leaves, topped by a masked face and a crown made out of flowers. He travels

through the streets accompanied by men (and now women) dressed and painted all in green, others dressed and painted entirely

black, and children bearing flowers. Morris and clog dancers entertain the crowds while the Jack, a

trickster figure (and traditionally lecherous) chases pretty girls and plays the fool. When he reaches a certain place, the Morris

dancers wield their wooden swords and strike the leaf man dead. A poem is solemnly

recited over his body, and then general merriment breaks out as the crowd plucks Jack's leaves off for luck.

("The killing of a tree spirit," notes James Frazer in The Golden Bough, "is always associated

with a revival or resurrection of him in a more youthful and vigorous form.")

Tree men aren't unique to the British Isles; they can be found in folk pageants all over Europe. In Bavaria, for example, a tree–spirit called the pfingstl roams through rural

towns clad in alder and hazel leaves, with a high pointed cap covered by

flowers. Two boys with swords accompany him as he knocks on the doors of

random houses, asking for presents but often getting thoroughly drenched

by water instead. This pageant also ends when the boys draw their wooden

swords and kill the green man. In a ritual from Picardy, a member of the Compagnons du Loup Vert (dressed in a green wolf skin and foliage)

enters the village church carrying a candle and garlands of flowers. He

waits until the Gloria is sung, then he walks to the alter and stands through

the mass. At its end, the entire congregation rushes up to strip the green

wolf of his leaves.

The Green Man's female

counterpart is the Green Woman, or the Sheela-Na-Gig . . .

. . . usually depicted in stone carvings as a primitive

female form giving birth to a spray of vegetation. Green Women are

far less common than Green Men, being rather harder to adapt to Christian

iconography or Victorian decoration -- and yet quite a few them appear in Romaneque churches built before the 16th century. Although Ireland has the greatest number of Sheela-Na-Gigs, they can be found throughout the British Isles, as well as in France, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, and the Czech Republic.

Like the sacred

"yoni" carvings of India, it was once customary to lick one's

finger and touch the Sheela-Na-Gig's vulva for good fortune.

A number of contemporary artists have found inspiration in the

ancient lore of the wood, including Brian Froud in Devon (creator of the Green Man painting and Green Woman drawing in this post) and Fidelma Massey

in Ireland (creator of mythic sculpture like the magical tree-woman above,

"A Shrine to the Mother of All Birds"). There have also been two

international art series recently that have drawn their inspiration from

the folklore of the wild: Eyes as Big as Plates (originating in Norway) and Wilder Mann (originating in France).

The two photographs directly above, and the one directly below, come from Eyes as Big as Plates , an ongoing project dreamed up by the Norwegian artists Riitta Ikonen and Karoline Hjorth. "Inspired by the romantics’ belief that folklore is the clearest

reflection of the soul of a people," says Ikonen, "Eyes as Big as Plates started out as

a play on characters and protagonists from Norwegian folklore. During a

one month residency at the Kinokino Centre for Art and Film in south-west Norway, Karoline and I collaborated with sailors, farmers, professors, artisans, psychologists, teachers, parachuters and senior citizens. The series then moved on to exploring the mental landscape of the

neighborly and pragmatic Finns." The third chapter of the project has taken Ikonen and Hjorth to New York City this spring.

“This blending of figure and ground," explains the artists, "recalls the way in which folk

narratives animate the natural world through a personification of

nature. The slippage of elderly figures into the landscapes suggests a

return to the earth, a celebration of lives lived, reinforcing the link

between humanity and the natural world.”

The images below come from Wilder Mann, a photography series by Charles Fréger (based in Rouen, France), who spent two years traveling around Europe documenting the folk pageants and festivals of what he calls "tribal Europe." The resulting photographic exhibition just moved from New York to Switzerland, and the images have been collected into a stunningly beautiful art book. (You can see more of Fréger's photographs here.)

As Rachel Hartigan Shea explains in an article about the series, "Traditionally the festivals are a rite of passage for young men. Dressing in

the garb of a bear or wild man is a way of 'showing your power,' says

Fréger. Heavy bells hang from many costumes to signal virility. The question is whether Europeans — civilized Europeans — believe that

these rituals must be observed in order for the land, the livestock,

and the people to be fertile. Do they really believe that costumes and

rituals have the power to banish evil and end winter? 'They all know

they shouldn’t believe it,' says Gerald Creed, who has studied mask

traditions in Bulgaria. Modern life tells them not to. But they remain

open to the possibility that the old ways run deep.'"

Likewise, the mythic scholar Daniel C. Noel is struck by the masculine power of Green Man lore: "Whether the Green

Man, is some sort of Jungian archetype 'returning' from a primeval past, a

Celtic survival in the psyche, seems not

as important to me as the metaphor he constitutes for men, and for the

gender-embattled culture, in the present and future. Whatever the

metaphysics of this fascinating figure, it is enough that he is a green

ideal and a good idea arriving from wherever to inspire us. We have

needed a

Father Nature for a long time, and never more urgently than now, when

all

over the planet, armored men, in or out of uniform, terrorize each

other,

women and children, and what remains of the wildwood."

Let's give Henry David Thoreau the last word today on why the wild and the folklore of the wild still matter: "Shall I not have intelligence with the earth?" he asks (in Walden). "Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?"

The art above: A Green Man painting by Brian Froud; a Green Man carving in a church near Birmingham; Jack-in-the-Greens in Oxford and the City of London (photographs from the "In the Company of the Green Man" blog); a Green Woman drawing by Brian Froud; a Sheela-na-gig carving at a church in County Clare, Ireland; "A Shrine for the Mother of the Birds" by Fidelma Massey; three photographs from Riitta Ikonen and Karoline Hjorth's "Eyes as Big as Plates" collaborative art project, the first from Norway, the second two from Finland; and four photographs from Charles Fréger's "Wilder Mann" series: a sauvage in Switerland, three kurkeri in Bulgaria, a careto in Portugal, and a devil in St. Nicholas' retinue in the Czech Republic. All art works are copyright by the artists.

Recommended reading: (Nonfiction) "Gossip from the Forest" by Sara Maitland (published as "From the Forest" in the US), "Forests" by Robert Pogue Harrison, "Green Man" by William Anderson & Clive Hicks, and "Sheela-Na-Gigs" by Barbara Freitag. (Fiction) The Mythago Wood Series by Robert Holstock, "Forests of the Heart," "The Wild Wood," and "Jack in the Mist" by Charles de Lint, and "The Green Man: Tales from the Mythic Forest" anthology. (Poetry) "The Forest" by Susan Stewart. (Art) "Wood" by Andy Goldsworthy and "Wilder Mann" by Charles Fre gér.

Today's post goes out to mythic maskmaker's Shane & Leah Odom; and to Charles de Lint, who brough Green Men to Bordertown.

May 19, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm running late this morning as I'm a bit under the weather today, but here are the Monday Tunes at last: some music from the woods and wilds in order to keep to our woodlands theme. These songs come from Soundcloud rather than YouTube because I couldn't find video performances of the pieces I particularly wanted to play this morning....

First up, "Home" by the Michigan alt-folk trio Breathe Owl Breathe, gently calling us out of the house and out of doors:

Next, "On Trees and Birds and Fire," a beautiful wind-and-rain filled song from I Am the Oak, the band of the Dutch singer/songwriter Thijs Kuijken, based in Utrecht:

Third is "Furr," an enchanting little song about woods and wolves from the Oregon alt-folk band Blitzen Trapper:

Next, "The Wild Hunt," a rather upbeat song about death and the Wild Hunt legends of northern Europe. It comes The Tallest Man On Earth, which is the stage name of the Swedish singer/songwriter Kristian Matsson:

And last, here's the English alt-folk band Matthew & the Atlas, calling us back from the wilds again with their utterly gorgeous song "Come Out of the Woods":

The drawings above are "Tree Nymph" and "Beauty as the Beast" by the always-amazing Virginia Lee, no stranger to the wilds herself.

May 18, 2013

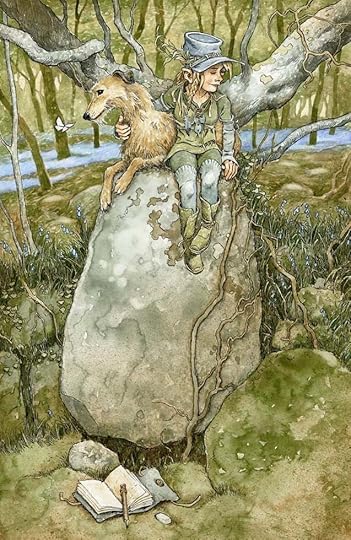

Into the Woods, 3: The Dog's Tale

I've been asked to give my thoughts on woods and wilderness from a furry, four-footed perspective. It's simple. We should spend more time there.

My People are intelligent People, and so I don't understand how they have gotten this matter precisely backwards. We spend some time each day outdoors, but many more hours in the House or Studio. Surely it is obvious that this is the reverse of what life ought to be?

My People like poetry, and so I present this poem by Mary Oliver to make my case. This poet belongs to a dog named Percy. Percy is very wise.

Percy and Books

Percy does not like it when I read a book.

He puts his face over the top of it, and moans.

He rolls his eyes, sometimes he sneezes.

The sun is up, he says, and the wind is down.

The tide is out, and the neighbor's dogs are playing.

But Percy, I say, Ideas! The elegance of language!

The insights, the funniness, the beautiful stories

that rise and fall and turn into strength, or courage.

Books? says Percy. I ate one once, and it was not enough. Let's go.

Photograph above: "Tilly Windling-Gayton Coming Down From Nattadon Hill" by Stu Jenks.

May 16, 2013

Into the Woods, 2: Tales of the Forest

From Gossip from the Forest: The Tangled Roots of Our Forests and Fairy Tales by Sara Maitland (which I'm reading now and highly recommend):

"Forests to the [early] Northern European peoples were dangerous and generous, domestic and wild, beautiful and terrible. And the forests were the terrain out of which fairy stories, one of our earliest and most vital cultural forms, evolved. The mysterious secrets and silences, gifts and perils of the forest are both the background to and source of these tales....

"Forests are places where a person can get lost and also hide -- and losing and hiding, of things and people, are central to European fairy stories in ways that are not true of similar stories in different geographies. Landscape informs the collective imagination as much as or more than it forms the individual psyche and its imagination, but this dimension is not something to which we always pay enough attention.

"I believe that the great stretches of forests in northern Europe, with their constant seasonal changes, their restricted views, their astonish biological diversity, their secret gifts and perils and the knowledge that you have to go through them to get anywhere else, created the themes and ethics of the fairy tales we know best. There are secrets, hidden identities, cunning disguises; there are rhythms of change like the changes of the seasons; there are characters, both human and animal, whose assistance can be earned or spurned; and there is -- over and over again -- the journey or quest, which leads first to knowledge and then to happiness. The forest is the place of trial in fairy stories, both dangerous and exciting. Coming to terms with the forest, surviving its terrors, utilising its gifts and gaining its help is the way to 'happy ever after.'

"Now fairy stories are at risk too, like the forests. Padraic Column has suggested that artificial lighting dealt them a mortal wound: when people could read and be productive after dark, something fundamental changed, and there was no longer need or space for the ancient oral tradition. The stories were often confined to books, which makes the text static, and they were handed over to children.

"The whole tradition of [oral] story telling is endangered by modern technology. Although telling stories is a very fundamental human attribute, to the extent that psychiatry now often treats 'narrative loss' -- the inability to construct a story of one's own life -- as a loss of identity or 'personhood,' it is not natural but an art form -- you have to learn to tell stories. The well-meaning mother is constantly frustrated by the inability of her child to answer questions like 'What did you do today?' (to which the answer is usually a muttered 'nothing' -- but the 'nothing' is cover for 'I don't know how to tell a good story about it, how to impose a story shape on the events'). To tell stories, you have to hear stories and you have to have an audience to hear the stories you tell. Oral story telling is economically unproductive -- there is no marketable product; it is out with the laws of patents and copyright; it cannot easily be commodified; it is a skill without monetary value. And above all, it is an activity requiring leisure -- the oral tradition stands squarely against a modern work ethic....Traditional fairy stories, like all oral traditions, need the sort of time that isn't money.

"The deep connect between the forests and the core stories has been lost; fairy stories and forests have been moved into different catagories and, isolated, both are at risk of disappearing, misunderstood and culturally undervalued, 'useless' in the sense of 'financially unprofitable.' "

From "Turning Our Fairy Tales Feral Again" by Sylvia Linsteadt:

“When we walk, holding stories in us, do they touch the ground

through our footprints? What is this power of metaphor, by which we

liken a thing we see to a thing we imagine or have seen before — the

granite crag to an old crystalline heart — changing its form, allowing

animation to suffuse the world via inference? Metaphor, perhaps, is the

tame, the civilised, version of shamanic shapeshifting, word-magic, the

recognition of stories as toothed messengers from the wilds. What if we

turned the old nursery rhymes and fairytales we all know into feral

creatures once again, set them loose in new lands to root through the

acorn fall of oak trees? What else is there to do, if we want to keep

any of the wildness of the world, and of ourselves?”

From Wild: An Elemental Journey by Jay Griffiths:

"What is wild cannot be bought or sold, borrowed or copied. It is. Unmistakeable, unforgettable, unshamable, elemental as earth and ice, water, fire and air, a quitessence, pure spirit, resolving into no contituents. Don't waste your wildness: it is precious and necessary.”

Fairy tale illustrations above: "The Princess in the Forest" by John Bauer (Norway), "He Too Saw the Image in the Water" by Kay Nielsen (Denmark), "Lost in the Woods" by Charles Robinson (England),"Thumbelina" by Adrienne Segur (France), "The Frog Prince" by Warwick Goble (England), and "Catskin" by Arthur Rackham (England).

Into the woods, Part II

From Gossip from the Forest: The Tangled Roots of Our Forests and Fairy Tales by Sara Maitland (which I'm reading now and highly recommend):

"Forests to the [early] Northern European peoples were dangerous and generous, domestic and wild, beautiful and terrible. And the forests were the terrain out of which fairy stories, one of our earliest and most vital cultural forms, evolved. The mysterious secrets and silences, gifts and perils of the forest are both the background to and source of these tales....

"Forests are places where a person can get lost and also hide -- and losing and hiding, of things and people, are central to European fairy stories in ways that are not true of similar stories in different geographies. Landscape informs the collective imagination as much as or more than it forms the individual psyche and its imagination, but this dimension is not something to which we always pay enough attention.

"I believe that the great stretches of forests in northern Europe, with their constant seasonal changes, their restricted views, their astonish biological diversity, their secret gifts and perils and the knowledge that you have to go through them to get anywhere else, created the themes and ethics of the fairy tales we know best. There are secrets, hidden identities, cunning disguises; there are rhythms of change like the changes of the seasons; there are characters, both human and animal, whose assistance can be earned or spurned; and there is -- over and over again -- the journey or quest, which leads first to knowledge and then to happiness. The forest is the place of trial in fairy stories, both dangerous and exciting. Coming to terms with the forest, surviving its terrors, utilising its gifts and gaining its help is the way to 'happy ever after.'

"Now fairy stories are at risk too, like the forests. Padraic Column has suggested that artificial lighting dealt them a mortal wound: when people could read and be productive after dark, something fundamental changed, and there was no longer need or space for the ancient oral tradition. The stories were often confined to books, which makes the text static, and they were handed over to children.

"The whole tradition of [oral] story telling is endangered by modern technology. Although telling stories is a very fundamental human attribute, to the extent that psychiatry now often treats 'narrative loss' -- the inability to construct a story of one's own life -- as a loss of identity or 'personhood,' it is not natural but an art form -- you have to learn to tell stories. The well-meaning mother is constantly frustrated by the inability of her child to answer questions like 'What did you do today?' (to which the answer is usually a muttered 'nothing' -- but the 'nothing' is cover for 'I don't know how to tell a good story about it, how to impose a story shape on the events'). To tell stories, you have to hear stories and you have to have an audience to hear the stories you tell. Oral story telling is economically unproductive -- there is no marketable product; it is out with the laws of patents and copyright; it cannot easily be commodified; it is a skill without monetary value. And above all, it is an activity requiring leisure -- the oral tradition stands squarely against a modern work ethic....Traditional fairy stories, like all oral traditions, need the sort of time that isn't money.

"The deep connect between the forests and the core stories has been lost; fairy stories and forests have been moved into different catagories and, isolated, both are at risk of disappearing, misunderstood and culturally undervalued, 'useless' in the sense of 'financially unprofitable.' "

From "Turning Our Fairy Tales Feral Again" by Sylvia Linsteadt:

“When we walk, holding stories in us, do they touch the ground

through our footprints? What is this power of metaphor, by which we

liken a thing we see to a thing we imagine or have seen before — the

granite crag to an old crystalline heart — changing its form, allowing

animation to suffuse the world via inference? Metaphor, perhaps, is the

tame, the civilised, version of shamanic shapeshifting, word-magic, the

recognition of stories as toothed messengers from the wilds. What if we

turned the old nursery rhymes and fairytales we all know into feral

creatures once again, set them loose in new lands to root through the

acorn fall of oak trees? What else is there to do, if we want to keep

any of the wildness of the world, and of ourselves?”

From Wild: An Elemental Journey by Jay Griffiths:

"What is wild cannot be bought or sold, borrowed or copied. It is. Unmistakeable, unforgettable, unshamable, elemental as earth and ice, water, fire and air, a quitessence, pure spirit, resolving into no contituents. Don't waste your wildness: it is precious and necessary.”

Fairy tale illustrations above: "The Princess in the Forest" by John Bauer (Norway), "He Too Saw the Image in the Water" by Kay Nielsen (Denmark), "Lost in the Woods" by Charles Robinson (England),"Thumbelina" by Adrienne Segur (France), "The Frog Prince" by Warwick Goble (England), and "Catskin" by Arthur Rackham (England).

May 15, 2013

Into the Woods, 1: The Language of the Earth

“The image of a wood has appeared often enough in English verse. It

has indeed appeared so often that it has gathered a good deal of verse

into itself; so that it has become a great forest where, with long

leagues of changing green between them, strange episodes of poetry have

taken place. Thus in one part there are lovers of a midsummer night, or

by day a duke and his followers, and in another men behind branches so

that the wood seems moving, and in another a girl separated from her two

lordly young brothers, and in another a poet listening to a nightingale

but rather dreaming richly of the grand art than there exploring it,

and there are other inhabitants, belonging even more closely to the

wood, dryads, fairies, an enchanter's rout. The forest itself has

different names in different tongues -- Westermain, Arden, Birnam,

Broceliande; and in places there are separate trees named, such as that

on the outskirts against which a young Northern poet saw a spectral

wanderer leaning, or, in the unexplored centre of which only rumours

reach even poetry, Igdrasil of one myth, or the Trees of Knowledge and

Life of another. So that indeed the whole earth seems to become this one

enormous forest, and our longest and most stable civilizations are only

clearings in the midst of it.” ― Charles Williams (The Figure of Beatrice)

"I’ve often thought of the forest as a living cathedral, but this

might diminish what it truly is. If I have understood Koyukon teachings,

the forest is not merely an expression or representation of sacredness,

nor a place to invoke the sacred; the forest is sacredness itself.

Nature is not merely created by God; nature is God. Whoever moves within

the forest can partake directly of sacredness, experience sacredness

with his entire body, breathe sacredness and contain it within himself,

drink the sacred water as a living communion, bury his feet in

sacredness, touch the living branch and feel the sacredness, open his

eyes and witness the burning beauty of sacredness.” - Richard Nelson (The Island Within)

“He stood staring into the wood for a minute, then said: 'What is it about the English countryside -- why is the beauty so much more than visual? Why does it touch one so?'

"He sounded faintly sad. Perhaps he finds beauty saddening -- I do myself sometimes. Once when I was quite little I asked father why this was and he explained that it was due to our knowledge of beauty's evanescence, which reminds us that we ourselves shall die. Then he said I was probably too young to understand him; but I understood perfectly.” - Dodie Smith (I Capture the Castle)

“All forests have their own personality. I don't just mean the obvious

differences, like how an English woodland is different from a Central

American rain forest, or comparing tracts of West Coast redwoods to the

saguaro forests of the American Southwest...they each have their own

gossip, their own sound, their own rustling whispers and smells. A voice

speaks up when you enter their acres that can't be mistaken for one

you'd hear anyplace else, a voice true to those particular tress,

individual rather than of their species.” ― Charles de Lint (The Onion Girl)

How I Go to the Woods

Ordinarily I go to the woods alone,

with not a single friend,

for they are all smilers and talkers

and therefore unsuitable.

I don’t really want to be witnessed talking to the catbirds

or hugging the old black oak tree.

I have my ways of praying,

as you no doubt have yours.

Besides, when I am alone

I can become invisible.

I can sit on the top of a dune

as motionless as an uprise of weeds,

until the foxes run by unconcerned.

I can hear the almost unhearable sound of the roses singing.

If you have ever gone to the woods with me,

I must love you very much.

Robert Pogue Harrison (author of the Forests: The Shadow of Civilization) recommends the work of four other fine poets of the forest: Andrea Zanzotto, Susan Stewart, A.R. Ammons, and W.S. Merwin. But Harrison's fear is that "the rapidity with which our society is losing daily

contact with the natural world will make it more and more unlikely that

we will have poets of the forest like Zanzotto or Merwin, or

Stewart, who grew up on a farm in the midst of Pennsylvania's forests.

The more our worlds are detached and abstracted from nature in this

daily way, the more I fear that poets will invoke the forests in only

the most superficial of ways, without the kind of full-bodied authority

that a lived relationship to the forest creates."

The late naturalist John Hay would have agreed that the forest poet must be one who knows the land, which takes both proximity and time. "There are occasions," he wrote (in The Immortal Wilderness), "when you can hear the mysterious language of the Earth: in water, or coming through the trees, emanating from the mosses, seeping through the under currents of the soil, but you have to be willing to wait and receive.”

As Tilly and I scramble over rock and root, as we do most mornings, rain or shine, I pray that our own small patch of woods remains safe, remains wild, remains here for future generations to come "home" to. I pray for patience to wait, and ears to listen, and a heart wide open, ready to receive. I want to be wild myself, like the woodland creatures in these paintings, in my quiet scribbler's way. But what is the wild? asks Louise Erdrich (in The Blue Jay's Dance). A place? A state of mind? The conjunction of these things? "What is wilderness?" she muses. "What are dreams but an internal

wilderness and what is desire but a wildness of the soul?”

Bernard Malamud's answer is simple and speaks to all of us, rural and urban, young and old. “The wild," he says, "begins where you least expect it, one step off your normal course."

All of the "wild art" above comes from artists here in the village: An illustration for JRR Tolkien's "The Hobbit" by Alan Lee, faery sculptures in the daffodils by Wendy Froud, Spring Watch by David Wyatt (from his Local Characters series), trolls by Brian Froud (from his new book "Trolls"), Telling Stories to the Trees by Rima Staines, and Wolf Boy by Danielle Barlow.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 707 followers