Into the Woods, 4: Wild Folklore

The Green Man is a pre–Christian symbol

found carved into the wood and stone of pagan temples and graves, of medieval

churches and cathedrals, and used as a Victorian architectural motif, across

an area stretching from Ireland in the west to Russia in the east. Although

commonly perceived as an ancient Celtic symbol, in fact its origins and

original meaning are shrouded in mystery. The name dates back only to 1939,

when folklorist Lady Raglan drew a connection between the foliate faces

in English churches and the Green Man (or "Jack of the Green")

tales of folklore. The evocative name has been widely adopted, but the legitimacy

of the connection still remains controversial, with little real evidence

to settle the question one way or the other. Earliest known examples of

the foliate head (as it was known prior to Lady Raglan) date back to classical

Rome — yet it was not until this pagan symbol was adopted by the Christian

church that the form fully developed and proliferated across Europe. Most folklorists conjecture that the foliate head symbolized mythic

rebirth and regeneration, and thus became linked to Christian iconography

of resurrection. (The Tree of Life, a virtually universal symbol of life,

death and regeneration, was adapted to Christian symbolism in a similar

manner.)

The Jack in the Green is a figure associated

The Jack in the Green is a figure associated

with the new growth of spring, fertility, and May Day celebrations. In a number of English towns (such as Hastings in East Sussex) the Jack pageant is still re-enacted each year. The Jack in the Green is played by a man in a towering eight–foot–tall costume of

leaves, topped by a masked face and a crown made out of flowers. He travels

through the streets accompanied by men (and now women) dressed and painted all in green, others dressed and painted entirely

black, and children bearing flowers. Morris and clog dancers entertain the crowds while the Jack, a

trickster figure (and traditionally lecherous) chases pretty girls and plays the fool. When he reaches a certain place, the Morris

dancers wield their wooden swords and strike the leaf man dead. A poem is solemnly

recited over his body, and then general merriment breaks out as the crowd plucks Jack's leaves off for luck.

("The killing of a tree spirit," notes James Frazer in The Golden Bough, "is always associated

with a revival or resurrection of him in a more youthful and vigorous form.")

Tree men aren't unique to the British Isles; they can be found in folk pageants all over Europe. In Bavaria, for example, a tree–spirit called the pfingstl roams through rural

towns clad in alder and hazel leaves, with a high pointed cap covered by

flowers. Two boys with swords accompany him as he knocks on the doors of

random houses, asking for presents but often getting thoroughly drenched

by water instead. This pageant also ends when the boys draw their wooden

swords and kill the green man. In a ritual from Picardy, a member of the Compagnons du Loup Vert (dressed in a green wolf skin and foliage)

enters the village church carrying a candle and garlands of flowers. He

waits until the Gloria is sung, then he walks to the alter and stands through

the mass. At its end, the entire congregation rushes up to strip the green

wolf of his leaves.

The Green Man's female

counterpart is the Green Woman, or the Sheela-Na-Gig . . .

. . . usually depicted in stone carvings as a primitive

female form giving birth to a spray of vegetation. Green Women are

far less common than Green Men, being rather harder to adapt to Christian

iconography or Victorian decoration -- and yet quite a few them appear in Romaneque churches built before the 16th century. Although Ireland has the greatest number of Sheela-Na-Gigs, they can be found throughout the British Isles, as well as in France, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, and the Czech Republic.

Like the sacred

"yoni" carvings of India, it was once customary to lick one's

finger and touch the Sheela-Na-Gig's vulva for good fortune.

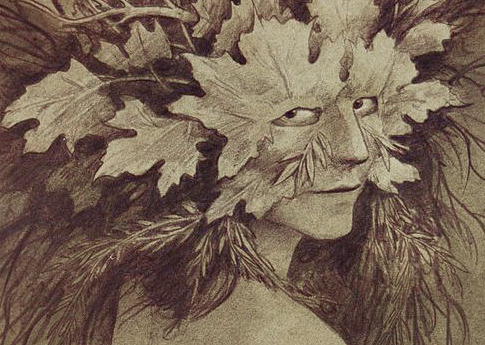

A number of contemporary artists have found inspiration in the

ancient lore of the wood, including Brian Froud in Devon (creator of the Green Man painting and Green Woman drawing in this post) and Fidelma Massey

in Ireland (creator of mythic sculpture like the magical tree-woman above,

"A Shrine to the Mother of All Birds"). There have also been two

international art series recently that have drawn their inspiration from

the folklore of the wild: Eyes as Big as Plates (originating in Norway) and Wilder Mann (originating in France).

The two photographs directly above, and the one directly below, come from Eyes as Big as Plates , an ongoing project dreamed up by the Norwegian artists Riitta Ikonen and Karoline Hjorth. "Inspired by the romantics’ belief that folklore is the clearest

reflection of the soul of a people," says Ikonen, "Eyes as Big as Plates started out as

a play on characters and protagonists from Norwegian folklore. During a

one month residency at the Kinokino Centre for Art and Film in south-west Norway, Karoline and I collaborated with sailors, farmers, professors, artisans, psychologists, teachers, parachuters and senior citizens. The series then moved on to exploring the mental landscape of the

neighborly and pragmatic Finns." The third chapter of the project has taken Ikonen and Hjorth to New York City this spring.

“This blending of figure and ground," explains the artists, "recalls the way in which folk

narratives animate the natural world through a personification of

nature. The slippage of elderly figures into the landscapes suggests a

return to the earth, a celebration of lives lived, reinforcing the link

between humanity and the natural world.”

The images below come from Wilder Mann, a photography series by Charles Fréger (based in Rouen, France), who spent two years traveling around Europe documenting the folk pageants and festivals of what he calls "tribal Europe." The resulting photographic exhibition just moved from New York to Switzerland, and the images have been collected into a stunningly beautiful art book. (You can see more of Fréger's photographs here.)

As Rachel Hartigan Shea explains in an article about the series, "Traditionally the festivals are a rite of passage for young men. Dressing in

the garb of a bear or wild man is a way of 'showing your power,' says

Fréger. Heavy bells hang from many costumes to signal virility. The question is whether Europeans — civilized Europeans — believe that

these rituals must be observed in order for the land, the livestock,

and the people to be fertile. Do they really believe that costumes and

rituals have the power to banish evil and end winter? 'They all know

they shouldn’t believe it,' says Gerald Creed, who has studied mask

traditions in Bulgaria. Modern life tells them not to. But they remain

open to the possibility that the old ways run deep.'"

Likewise, the mythic scholar Daniel C. Noel is struck by the masculine power of Green Man lore: "Whether the Green

Man, is some sort of Jungian archetype 'returning' from a primeval past, a

Celtic survival in the psyche, seems not

as important to me as the metaphor he constitutes for men, and for the

gender-embattled culture, in the present and future. Whatever the

metaphysics of this fascinating figure, it is enough that he is a green

ideal and a good idea arriving from wherever to inspire us. We have

needed a

Father Nature for a long time, and never more urgently than now, when

all

over the planet, armored men, in or out of uniform, terrorize each

other,

women and children, and what remains of the wildwood."

Let's give Henry David Thoreau the last word today on why the wild and the folklore of the wild still matter: "Shall I not have intelligence with the earth?" he asks (in Walden). "Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mould myself?"

The art above: A Green Man painting by Brian Froud; a Green Man carving in a church near Birmingham; Jack-in-the-Greens in Oxford and the City of London (photographs from the "In the Company of the Green Man" blog); a Green Woman drawing by Brian Froud; a Sheela-na-gig carving at a church in County Clare, Ireland; "A Shrine for the Mother of the Birds" by Fidelma Massey; three photographs from Riitta Ikonen and Karoline Hjorth's "Eyes as Big as Plates" collaborative art project, the first from Norway, the second two from Finland; and four photographs from Charles Fréger's "Wilder Mann" series: a sauvage in Switerland, three kurkeri in Bulgaria, a careto in Portugal, and a devil in St. Nicholas' retinue in the Czech Republic. All art works are copyright by the artists.

Recommended reading: (Nonfiction) "Gossip from the Forest" by Sara Maitland (published as "From the Forest" in the US), "Forests" by Robert Pogue Harrison, "Green Man" by William Anderson & Clive Hicks, and "Sheela-Na-Gigs" by Barbara Freitag. (Fiction) The Mythago Wood Series by Robert Holstock, "Forests of the Heart," "The Wild Wood," and "Jack in the Mist" by Charles de Lint, and "The Green Man: Tales from the Mythic Forest" anthology. (Poetry) "The Forest" by Susan Stewart. (Art) "Wood" by Andy Goldsworthy and "Wilder Mann" by Charles Fre gér.

Today's post goes out to mythic maskmaker's Shane & Leah Odom; and to Charles de Lint, who brough Green Men to Bordertown.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers