Terri Windling's Blog, page 184

July 31, 2013

Into the Woods, 21: Up in the trees

Robert Macfarlane begins his book The Wild Places at the top of a 30 foot beech tree situated in a city woodland. "I had started climbing trees about three years earlier," he tells us. "Or rather, re-started; for I had been at a school that had a wood for its playground. We had climbed and christened the different trees (Scorpio, The Major Oak, Pegagsus), and fought for their control in territorial conflicts with elaborate rules and fealties. My father built my brother and me a tree house in our garden, which we had defended successfully against years of pirate attack. In my late twenties, I had begun to climb trees again. Just for the fun of it: no ropes, and no danger either.

"In the course of my climbing, I learned to discriminate between tree species. I liked the lithe springiness of silver birch, the alder and the young cherry. I avoided pines -- brittle branches, callous bark -- and planes. And I found that the horse chestnut, with its limbless lower trunk and prickly fruit, but also its tremendous canopy, offered the tree-climber both a difficulty and an incentive.

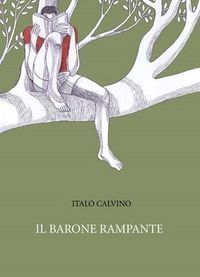

"I explored the literature of tree-climbing," Macfarlane continues; "not extensive, but so exciting. John Muir had swarmed up a hundred-foot Douglas Spruce during a Californian windstorm, and looked out over a forest, 'the whole mass of which was kindled into one continuous blaze of white sun-fire!' Italo Calvino had written his  magical novel, The Baron in the Trees, whose young hero, Cosimo, in an adolescent huff, climbs a tree on his father's forested estate and vows never to set foot on the ground again. He keeps his impetuous word, and ends up living and even marrying in the canopy, moving for miles between olive, cherry, elm, and holm oak. There were the boys in B.B.'s Brendan Chase, who go feral in an English forest rather than return to boarding-school, and climb a 'Scotch pine' in order to reach a honey buzzard's nest scrimmed with beech leaves. And of course there was the realm of Winnie the Pooh and Christopher Robin: Pooh floating on his sky-blue balloon up to the oak-top bee's nest, in order to poach some honey; Christopher ready with his pop-gun to shoot Pooh's balloon down once the honey had been poached....

magical novel, The Baron in the Trees, whose young hero, Cosimo, in an adolescent huff, climbs a tree on his father's forested estate and vows never to set foot on the ground again. He keeps his impetuous word, and ends up living and even marrying in the canopy, moving for miles between olive, cherry, elm, and holm oak. There were the boys in B.B.'s Brendan Chase, who go feral in an English forest rather than return to boarding-school, and climb a 'Scotch pine' in order to reach a honey buzzard's nest scrimmed with beech leaves. And of course there was the realm of Winnie the Pooh and Christopher Robin: Pooh floating on his sky-blue balloon up to the oak-top bee's nest, in order to poach some honey; Christopher ready with his pop-gun to shoot Pooh's balloon down once the honey had been poached....

"There was nothing unique about my beech tree, nothing difficult in its ascent, no biological revelation

at its summit, nor any honey, but it had become a place to think. A

roost. I was fond of it, and it -- well, it had no notion of me. I had

climbed it many times; at first light, dusk, and glaring noon. I had

climbed it in winter, brushing snow from the branches of my hand, with

the wood cold as stone to the touch, and real crows' nests black in the

branches of nearby trees. I had climbed in in early summer, and looked

out over the countryside with heat jellying the air and the drowsy buzz

of a tractor from somewhere nearby. And I had climbed it in monsoon

rain, with water falling in rods thick enough for the eye to see.

Climbing the tree was a way to get perspective, however slight; to look

down on a city that I usually looked across. The relief of relief. Above

all, it was a way of defraying the city's claims on me."

The city (Cambridge, England) is Macfarlane's home, the center of his work and family life...but even his forays into the city's trees did not satisfy his craving for the natural world and his hunger for true wilderness. "Anyone who lives in a city," he writes, "will know the feeling of having been there too long. The  gorge-vision that the streets imprint on us, the sense of blockage, the longing for surfaces other than glass, brick, concrete and tarmac....I have lived in Cambridge on and off for a decade, and I imagine I will continue to do so for years to come. And for as long as I stay here, I know I will have to also get to the wild places."

gorge-vision that the streets imprint on us, the sense of blockage, the longing for surfaces other than glass, brick, concrete and tarmac....I have lived in Cambridge on and off for a decade, and I imagine I will continue to do so for years to come. And for as long as I stay here, I know I will have to also get to the wild places."

Macfarlane's need for "wild life" is our good fortune, for out of that need has come four gorgeous books that I highly recommend: The Wild Places, The Old Ways, Holloways (with Stanley Donwood & Dan Richards) and Mountains of the Mind. (He also wrote the introduction to the new ebook edition of M. John Harrison's fine novel, Climbers.)

In a piece for the Guardian a few years back, Macfarlane lauded Richard Preston's The Wild Trees, an account of the the scientists who research (and climb) the giant redwoods of California and Oregon. "I

first encountered Preston's book about two years ago," he noted, "in its ur-form as a

long New Yorker essay. It stayed with me as an influence as I wrote a

book of my  own, describing the journeys I made in search of 'other

own, describing the journeys I made in search of 'other

worlds' - the remaining wild places of Britain and Ireland. That search

took me from the sea cliffs of Cornwall to the river mouths of

Sutherland, from East Anglia's shingle beaches to the salt marshes of

Essex, from the moors of the Pennines to the mines and sea caves of

North Wales.

"I traveled widely, and I tried to travel wildly. I

walked, swam and climbed through landscape and seascape. Wherever

possible, I slept out. I traveled in all four seasons, in sunlight,

rain and blizzard, and by night as well as day. I also sought out the

company of native guides: people who had lived in those landscapes for

many years, or come to know them intimately as scientists, artists,

shepherds or foresters - people who had acquired the wisdom of sustained

contact with a place. I tried, in short, to find new ways of

approaching this much-written-about archipelago of ours. Ways of 'coming

at the landscape' - as the Georgian travel writer Stephen Graham

memorably put it - 'diagonally'....

"Woods and forests were important features of my journeys. I explored the dwarf hazel forests of the Burren in County

Clare, the oakwood 'thicks' of Suffolk, and the wild hedgerows of

Dorset. I went alone to the Black Wood of Rannoch, the cloud forests of

Dartmoor, and the birch woods of Cumbria.

"Wherever I could," Macfarlane adds, "I climbed trees."

Another way to experience life in the trees is to create a dwelling nested in the branches. I always wanted a tree house as a child and never had one, so I covet these grown-up versions:

The Bird's Nest, on the California Coast near Big Sur

The Bird's Nest, on the California Coast near Big Sur

Two French tree houses: one hidden in the trees in La Croix-Valmer, and one perched elegantly in Rambouillet Forest.

Two French tree houses: one hidden in the trees in La Croix-Valmer, and one perched elegantly in Rambouillet Forest.

The Bird's Nest room at the Treehotel in Swedish Lapland.

The Bird's Nest room at the Treehotel in Swedish Lapland.

In 2008, the Japanese sculptor and installation artist Tadashi Kawamata created

the Tree Huts project in Madison Square Park in New York City -- a small park that I happen to know well, as I worked for many years for Tor Books in the elegant old Flat Iron

building (pictured in the photo below), and before that for Ace Books, just a few blocks north on Madison Avenue.

For this site-specific project,

Kawamata built twelve wooden huts high in the trees of the park, created

out of raw lumber, found objects, and construction scraps. For the

artist, this artwork explored ideas about the meaning of shelter in an

urban context....but for children (and those of us with magically-inclined imaginations) it was as though Peter Pan and his tribe of Lost Boys had

taken up residence in this most urban of settings, or perhaps some

tree-dwelling clan of faeries who were now staking an urban claim. The huts

appeared in early October, charmed residents and tourists alike for several months...and vanished with the turning of the year, leaving the faintest trace of Mystery behind.

"To the great tree-loving fraternity we belong," Henry Ward Beecher (an early defender of the American wild) once said. 'We love trees with

universal and unfeigned love, and all things that do grow under them or

around them -- the whole leaf and root tribe."

I spent a good deal of time high in trees when I was young -- both for the physical pleasure that climbing gave me and also as an escape from home: in the tree tops I could think, cry, read, or do my homework undisturbed, high above the world. All these years later, I can still remember what it feels like to shimmy up an oak's rough trunk or to sway in the slender branches of a birch; to be strong, quick, supple, and fearless, climbing higher than others dared to go. I still count myself a member of the "leaf and root tribe" though my forays into trees are rare and tame these days; I'm slower, stiffer, an earthy root elder now, not a budding green leaf. On the outside, I'm a middle-aged woman with health concerns, who sometimes looks like the wind could blow me over; inside, I'm still that strong, quick, straw-haired girl who could and did climb anything.

I spent a good deal of time high in trees when I was young -- both for the physical pleasure that climbing gave me and also as an escape from home: in the tree tops I could think, cry, read, or do my homework undisturbed, high above the world. All these years later, I can still remember what it feels like to shimmy up an oak's rough trunk or to sway in the slender branches of a birch; to be strong, quick, supple, and fearless, climbing higher than others dared to go. I still count myself a member of the "leaf and root tribe" though my forays into trees are rare and tame these days; I'm slower, stiffer, an earthy root elder now, not a budding green leaf. On the outside, I'm a middle-aged woman with health concerns, who sometimes looks like the wind could blow me over; inside, I'm still that strong, quick, straw-haired girl who could and did climb anything.

A friend of mine, from a troubled background, describes his upbringing as being "raised by wolves." I was raised by trees, whenever and wherever I could find them.

And thank heavens they were there.

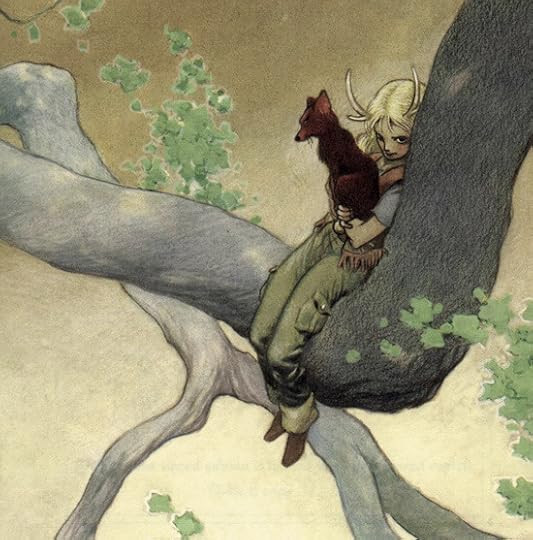

The aboreal art above is: "The Faery Reel" and "Puck" (from A Midsummer's Night Dream) by the brilliant, incomparable Charles Vess;"The Baron in the Trees" by Yan Nascimbene;

and "The Baron in the Trees" by Leredana Canini; "The Baron in the Trees," Italian edition (artist uncredited); "Pooh and the Honey Pots" by Howard Earnest Shepard (1879-1976); "Tapping the Dream Tree" by Charles Vess; two drawings by Virginia Lee: "The Capture" and "Tree People"; "Nest," a photograph by Ione Rucquoi; sundry photographs of tree houses and huts; a little tree girl of mine; and "Red Dog and Jackalope" by Charles Vess (from Medicine Road).

July 30, 2013

Into the Woods, 20: The Deepwood (Part ll)

From The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane:

"Before coming to the Black Wood, I had read as widely in tree lore as possible. As well as the many accounts I encountered of damage to trees and woodland -- of what in German is called Waldsterben, or 'forest-death' -- I also met with and noted down stories of astonishment at woods and trees. Stories of how Chinese woodsmen in the T'ang and S'ung dynasties -- in obedience to the Taoist philosophy of a continuity of nature between humans and other species -- would bow to the trees which they felled, and offer a promise that the tree would be used well, in buildings that would dignify the wood once it had become timber. The story of Xerxes, the Persian king who so loved sycamores that, when marching to war with the Greeks, he halted his army of many thousands of men in order that they might contemplate and admire one outstanding specimen. Thoreau's story of how he felt so attached to the trees in the woods around his home-town of Concord, Massachusetts, that he would call regularly on them, glady tramping 'eight or ten miles through the deepest snow to keep an appointment with a beech-tree, or yellow-birch, or an old acquaintance among the pines.'

"When Willa Cather moved to the prairies of Nebraska, she missed the

wooded hills of her native Virginia. Pining for trees, she would

sometimes travel south 'to our German neighbors, to admire their catalpa

grove, or to see the big elm tree that grew out of a crack in the

earth. Trees were so rare in that country that we used to feel anxious

about them, and visit them as if they were persons'....

"Single trees are extraordinary; trees in number more extraordinary still. To walk in a wood is to find fault with Socrates's declaration that 'Trees and open country cannot teach me anything, whereas men in town do.' Time is kept and curated and in different ways by trees, and so it is experienced in different ways when one is among them. This discretion of trees, and their patience, are both affecting. It is beyond our capacity to comprehend that the American hardwood forest waited seventy million years for people to come and live in it, though the effort of comprehension is itself worthwhile. It is valuable and disturbing to know that grand oak trees can take three hundred years to grow, three hundred years to live and three hundred years to die. Such knowledge, seriously considered, changes the grain of the mind.

"Thought, like memory, inhabits external things as much as the inner

regions of the human brain. When the physical correspondents of thought

disappear, then thought, or its possibility, is also lost. When woods

and trees are destroyed -- incidentally, deliberately -- imagination and

memory go with them. W.H. Auden knew this. 'A culture,' he wrote

warningly in 1953, 'is no better than its woods.' "

From Ross Anderson's interview of Robert Pogue Harrison (in The LA Review of Books):

Robert Anderson: Your book [Forests], particularly the end of

it, criticizes some of the basic ideas that motivate environmentalism

and ecology. In particular you argue that when we conceive of

deforestation as "loss of wildlife habitat," or "loss of nature," or

"loss of biodiversity," we're not capturing the full loss that we face.

First of all, what is the extent of that loss, and in your view has

ecology changed much in the past twenty years?

Robert Pogue Harrison: That's a good question. When I'm critical of

modern approaches to ecology, I'm really trying to remind my reader of

the long relationship that Western civilization has had to these forests

that define the fringe of its place of habitation, and that this

relationship is one that has a rich history of symbolism and imagination

and myth and literature. So much of the Western imagination has

projected itself into this space that when you lose a forest, you're

losing more than just the natural phenomenon or biodiversity; you're

also losing the great strongholds of cultural memory.

Is there a sound? There is a forest.

What is the world? The word is wilderness.

What is the answer? The answer is the world.

What is the beginning? A beginning is happiness.

What is the end? No one lives there now.

What is a beginning? The beginning is light.

- Bim Ranke (from "Trouble Deaf Heaven: Sonnet 29")

July 29, 2013

Into the Woods, 20: The Deepwood (Part 1)

From The Wild Places by English naturalist Robert MacFarlane:

"To understand the wild you must understand the wood. For civilization, as the historian Robert Pogue Harrison writes, 'literally cleared its space in the midst of forests.' For millennia, 'a sylvan fringe of darkness defined the limits of cultivation, the margins of its cities, the boundaries of its domains, but also the extravagance of its imagination.'

"Although the disappearance of the true wildwood [in the British Isles] occurred in the

Neolithic period, before humanity began to record its own history, creation myths in almost all cultures look fabulously back to a forested earth. In the ancient Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, the quest-story which begins world literature, Gilgamesh sets out on his journey from Uruk to the Cedar Mountains, where he has been charged to slay the Huwawa, the guardian of the forest. The Roman empire also defined itself against the forests in which its capital city was first established, and out of which its founders, the wolf-suckled twins, emerged. It was the Roman Empire which would proceed to destroy the dense forests of the ancient world.

"The association of the wild and the wood also run deep in etymology. The two words are thought to have grown out of the root word wald and the old Teutonic word walthus, meaning 'forest.' Walthus entered Old English in its variant forms of 'weald,' 'wald,' and 'wold,' which were used to designate both 'a wild place' and 'a wooded place,' in which wild creatures -- wolves, foxes, bears -- survived. The wild and wood also graft together in the Latin word silva, which means 'forest,' and from which emerged the idea of 'savage,' with its connotations of fertility....

"The deepwood is vanished in these islands -- much, indeed, had vanished before history began -- but we are still haunted by the idea of it. The deepwood flourishes in our architecture, art and above all in our literature. Unnumbered quests and voyages have taken place through and over the deepwood, and fairy tales and dream-plays have been staged in its glades and copses. Woods have been a place of inbetweenness, somewhere one might slip from one world to another, or one time to a former: in Kipling's story 'Puck of Pook's Hill,' it is by right of 'Oak and Ash and Thorn' that the children are granted their ability to voyage back into English history.

"There is no mystery in this association of woods and otherworlds, for

as anyone who has walked the woods knows, they are places of

correspondence, of call and answer. Visual affinities of color, relief

and texture abound. A fallen branch echoes the deltoid form of a

streambed into which it has come to rest. Chrome yellow autumn elm

leaves find their color rhyme in the eye-ring of the blackbird.

Different aspects of the forest link unexpectedly with each other, and

so it is that within the stories, different times and worlds can be

joined.

"Woods and forests have been essentialt to the imagination of these islands, and of countries throughout the world, for centuries. It is for this reason that when woods are felled, when they are suppressed by tarmac and concrete and asphalt, it is not only unique species and habitats that disappear, but also unique memories, unique forms of thought."

What Tilly and I saw on our morning walk...

...in-between bursts of summer showers: a rainbow stretching from the open moor to the rolling green fields of Chagford.

In myth, rainbows often lead from the human world to the spirit world or the realm of the gods: Eddic

Bifröst in Norse myth, for example, is a rainbow bridge built by the gods themselves, leading to their home in Asgard. In Arabian myth, the rainbow is often portrayed as the bow of a god or djinn responsible for sending rain and storms, while in Slavonic myth it's the tri-colored belt of the Mother Goddess or the Virgin Mary. The Rainbow Serpent is a well-known sacred figure from Australian aboriginal lore -- but it can also be found in Brazilian myth, and in tales from equitorial Africa.

Click on the picture to see it larger

Click on the picture to see it larger

I've written about rainbows in my personal symbology before, and they never fail to fill me with awe. Tilly and I stopped to watch this one until fresh rain showers drove us home again, shrieking (me, not Tilly) as we ran through the woods, getting very wet indeed.

Now Tilly lounges by the studio window, damp but content, while the rain drums patterns on the cabin's tin roof. Outside, the parched hills drink it down; and inside, all is snug and dry. With Celtic fiddles on the stereo and a fresh mug of coffee to hand, the work week begins ....

July 28, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

After posting photographs of the Morris troupe dancing near Fingle Bridge last week, I was reminded of my favorite local troupe: Beltane, performers of the wild, almost shamanic form of the dance called Border Morris.

Americans tend to view Morris dancing as a quaintly charming slice of "olde England," and don't often realize how many of the English themselves find it hopelessly twee.* (This is the kind of dance they're generally thinking of.) As an oft-repeated quote (variously attributed to Thomas Beecham, Wilde, Shaw, and others) says snidely: "Try everything at least once once, my dear, except incest and Morris dancing." Personally, I like Morris dancing of all sorts (thereby "outing" myself as deeply uncool); and I especially love modern Border Morris as practiced by younger troupes like Beltane, with goth, punk, and neo-pagan leanings.

Americans tend to view Morris dancing as a quaintly charming slice of "olde England," and don't often realize how many of the English themselves find it hopelessly twee.* (This is the kind of dance they're generally thinking of.) As an oft-repeated quote (variously attributed to Thomas Beecham, Wilde, Shaw, and others) says snidely: "Try everything at least once once, my dear, except incest and Morris dancing." Personally, I like Morris dancing of all sorts (thereby "outing" myself as deeply uncool); and I especially love modern Border Morris as practiced by younger troupes like Beltane, with goth, punk, and neo-pagan leanings.

Border Morris originated in the west of Britain -- probably sometime in the late Middle Ages, arising from dance traditions that were older still -- developed primarily by dancers and musicians along the border of England and Wales. The distinguishing characteristics of Border Morris (as opposed to other forms) are shorter sticks, higher steps, ragged costumes,  blackened faces, and larger bands of musicians. The history of the blackened face is much disputed: it may have had ceremonial significance in the dance's deeply pagan origins; or it might have been a form of disguise adopted in years when Border Morris was frowned upon as rowdy, subversive, and un-Christian.

blackened faces, and larger bands of musicians. The history of the blackened face is much disputed: it may have had ceremonial significance in the dance's deeply pagan origins; or it might have been a form of disguise adopted in years when Border Morris was frowned upon as rowdy, subversive, and un-Christian.

It certain is rowdier than most other forms of Morris; it's also more overtly pagan, and thus (to me) more powerful. Often performed at sacred times in the Celtic lunar calendar, the dances invoke a palpable magic tied to the land, the seasons, and the mythic wheel of life, death, and rebirth. Like other forms of sacred dance the world over, the drum beat and the dancers' steps weave patterns intended to keep the seasons turning and maintain the balance of the human/nonhuman worlds. Yet in contrast to other, more mannered forms of Morris, Border dancers unleash an energy that is earthier, lustier, more anarchic...both joyous and unsettling to watch, especially by dusk or firelight.

Howard and I once came across Beltane dancing in our village square, just as dark began to fall. At one moment in the dance, the music went quiet. The troupe dropped to their knees in unison, sticks pounding the ground in a slow, steady rhythm. Then, just as slowly, the dancers rose...the music started faintly...quickened and loudened...and the dance romped on again. It was breathtaking to watch: both beautiful and chilling. If a portal into Faerie had opened at that moment, I would not have been at all surprised.

In the video at the top of this post, Beltane performs a Fire Dance at the dawn of May Day (Beltane), 2012. The dance took place on Dartmoor, on a foggy crossroad near Hay Tor.

Below, a dance for Winter Solstice at Stonehenge, filmed last December.

And last, just for fun:

Dancing in the sea. This video (complete with wind and barking dog) was filmed at Teignmouth on the south Devon coast.

* The American equivalent of the English word "twee" would be "hokey" or "corny."

July 25, 2013

On Singing & Music

“It may be laid down as a general rule that if a man begins to sing,

no one will take any notice of his song except his fellow human beings.

This is true even if his song is surpassingly beautiful. Other men may

be in

raptures at his skill, but the rest of creation is, by and large,

unmoved. Perhaps a cat or a dog may look at him; his horse, if it is an

exceptionally intelligent beast, may pause in cropping the grass, but

that is the extent of it. But when the fairy sang, the whole world

listened to him. Stephen felt clouds pause in their passing; he felt

sleeping hills shift and murmur; he felt cold mists dance. He understood

for the first time that the world is not dumb at all, but merely

waiting for someone to speak to it in a language it understands. In the

fairy's song the earth recognized the names by which it called itself.” -

Susanna Clarke (Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell)

"Why does exquisite song stir us deeply? Perhaps, more than any

instrument, song can capture us because the human voice is our very own

sound; the voice is the most intimate signature of human individuality

and, of all the sounds in creation, comes from an utterly different

place. Though there is earth in the voice, the voice is not of the

earth. It is the voice of the in-between creature, the one in whom both

earth and heaven become partially vocal." - John O'Donohue (Beauty)

"There is a profound sense in which music opens a secret door in time

and reaches in to the eternal. This is the authority and grace of music:

it evokes or creates an atmosphere where presence awakens to its

eternal depth. In our everyday experience the quality of presence is

generally limited and broken. Much of the time we are distracted; we

might manage to be externally present, but often our minds are secretly

elsewhere. Music can transform this fragmentation, for when you enter

into a piece of music your feeling deepens and your presence clarifies.

It brings you back to the mystery of who you are....Listening to music

stirs the heavy heart; it alters the gravity." - John O'Donohue (Beauty)

I want to thank

my mother for working and always paying for

my piano lessons

before she paid the Bank of America loan

or bought the groceries

or had our old rattling Ford repaired.

I was a quiet child,

afraid of walking into a store alone,

afraid of the water,

the sun,

the dirty weeds in back yards,

afraid of my mother’s bad breath,

and afraid of my father’s occasional visits home,

knowing he would leave again;

afraid of not having any money,

afraid of my clumsy body,

that I knew

no one would ever love

But I played my way

on the old upright piano

obtained for $10,

played my way through fear,

through ugliness,

through growing up in a world of dime-store purchases,

and a desire to love

a loveless world.

- Diane Wakoski (an excerpt from her poem "Thanking My Mother for Piano Lessons")

“Our songs travel the earth. We sing to one another. Not a single note

is ever lost and no song is original. They all come from the same place

and go back to a time when only the stones howled.”

- Louise Erdrich

(The Master Butcher's Singing Club)

"Singing

has always seemed to me the most perfect means of expression. It is so

spontaneous. And after singing, I think the violin. Since I cannot sing,

I paint." - Georgia O'Keeffe

“Then the musical instruments appeared. Dad’s snare drum from the house,

Henry’s guitar from his car, Adam’s spare guitar from my room. Everyone

was jamming together, singing songs: Dad’s songs, Adam’s songs, old

Clash songs, old Wipers songs. Teddy was dancing around, the blond of

his hair reflecting the golden flames. I remember watching it all and

getting that tickling in my chest and thinking to myself: This is what

happiness feels like.”

- Gayle Forman (If I Stay)

(That's how I feel when the instruments come out too.)

“I believe in kindness. Also in mischief. Also in singing, especially when singing is not necessarily prescribed.” - Mary Oliver

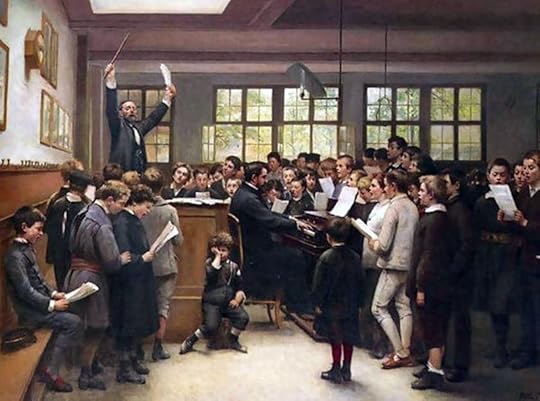

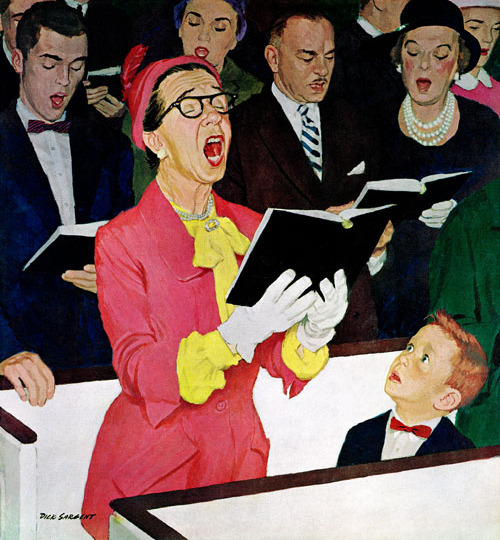

The art above is: "A Fairy Song" by Arthur Rackham (English, 1867-1939); "Beauty & the Beast: After She Had Done Her Work She Would Sing and Play" by Edmund Dulac (French, 1882-1953); "The Green Singing Book" by Elizabeth Shippen Green (American, 1871-1954 ); "The Piano Lesson" by Carl Larsson (Swedish, 1853-1919); "Choir Rehearsal" by Otto Piltz (German, 1846-1910);

"The Choir Lesson" by Auguste Joseph Trupheme (French, 1836-1898); "A Woman Singing" by Godfried Schalcken (Dutch, 1643-1706); "The Singing Lesson" by Frederico Zandomeneghi (Italian, 1841-1917); and "Singing Praise" by Richard Sargent (American, 1911-1979 ), for the Saturday Evening Post.

Happy Birthday, Tilly!

She's four years old today, and more loveable than ever.

"Any glimpse into the life of an animal quickens our own and makes it larger and better in every way." - John Muir

July 24, 2013

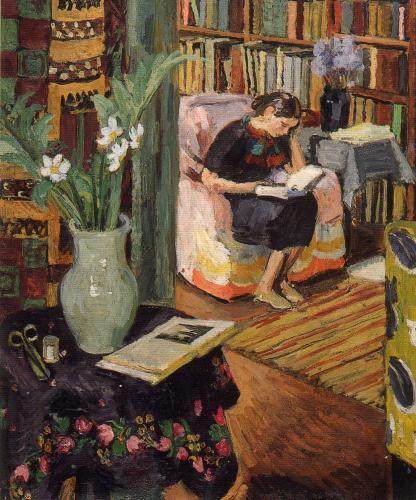

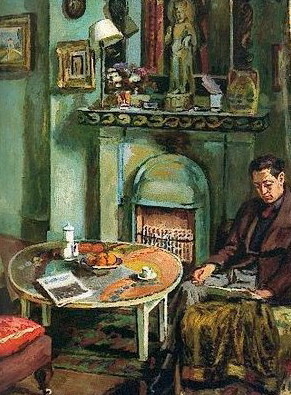

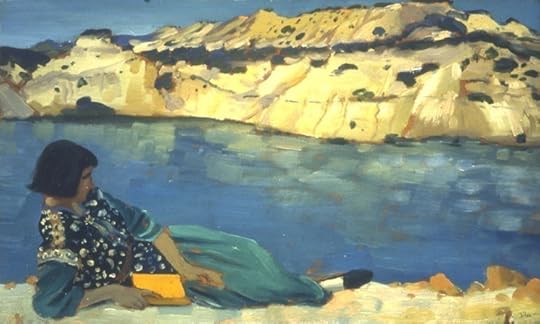

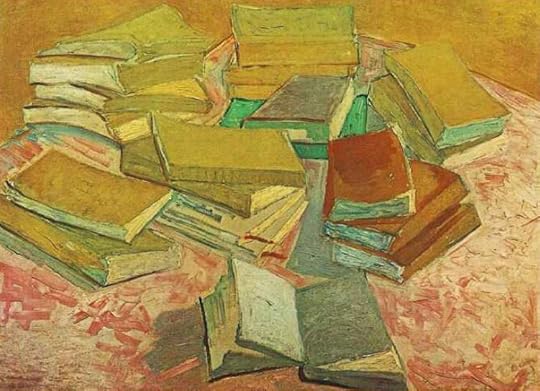

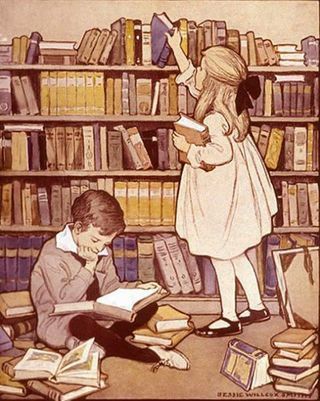

More "reading art" (for Ellen Kushner):

“Literature duplicates the experience of living in a way that nothing

else can, drawing you so fully into another life that you temporarily

forget you have one of your own. That is why you read it, and might even

sit up in bed ’till early dawn, throwing your whole tomorrow out of

whack, simply to find out what happens to some people who, you know

perfectly well, are made up.” – Barbara Kingsolver

"You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the

history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me

that the things that tormented me most were the very things that

connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been

alive." - James Baldwin

“We possess the books we read, animating the waiting stillness of their

language, but they possess us also, filling us with thoughts and

observations, asking us to make them part of ourselves." – David L. Ulin

"Live for a while in the books you love. Learn from them what is

worth learning, but above all love them. This love will be returned to

you a thousand times over. Whatever your life may become, these books

-of this I am certain- will weave through the web of your unfolding.

They will be among the strongest of all threads of your experiences,

disappointments, and joys." - Rainer Maria Rilke

“So often, a visit to a bookshop has cheered me, and reminded me that

there are good things in the world.” – Vincent van Gogh

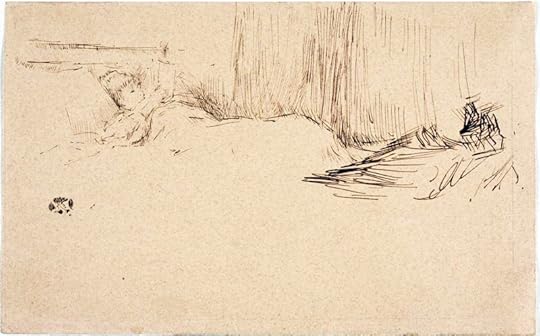

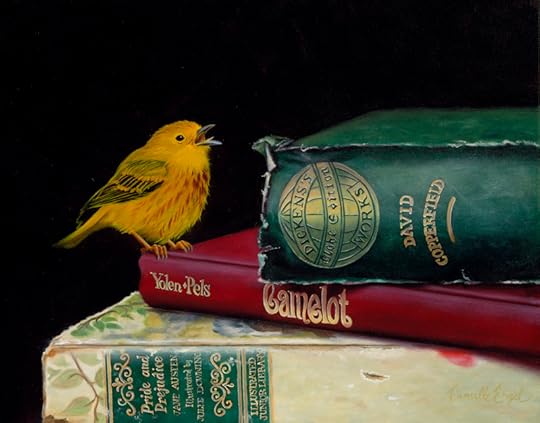

"The Poor Poet" by Carl Spitzweg (German, 1808-1834); "My Life in Bed" by Joseph Hubbard (American), "Girl Reading," an etching by James Abbott MacNeill Whistler (American, 1934-1903); "Reading in Bed" by Peter Brannan (English, 1926-1994); "Boys Reading," a photograph by André Kertész (Hungarian-American, 1894-1985 ), "The Dramatist: A Portrait of the Artist's Husband" by Brigit Ganley (Irish, 1909-2002); "Girl Reading" and "Interior with Duncan Grant Reading" by Vanessa Bell (English, 1879-1961); "Portrait of Chattie Salaman" by Duncan Grant (English, 1885-1978); "Woman Reading" by Alexander Deineka (Russian, 1899-1969); "A Lady Reading" and "Reader With Yellow Necklace" by Félix Vallotton (Swiss, 1865-1925); "Sally" by Mia Wolff (American); "The Blue Pool: Dorelia with Book" by Augustus John (Welsh, 1878-1961); "The Precious Book" and "Brown Tea Pot with Yellow Book" by his sister, Gwen John (Welsh, 1876-1939); "Novels" and "Novel Reader" by Vincent Van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890)' "Hall's Bookshop in Royal Tunbridge Wells, west Kent" by John Wheatley (English, 1892-1955); and a "A Song Worth Volumes by Camille Engle (American), from her lovely Literary Roost series.

July 23, 2013

Down by the riverside

Oh Earth, Wait for Me

by Pablo Neruda

Return me, oh sun,

to my wild destiny,

rain of the ancient wood,

bring me back the aroma and the swords

that fall from the sky,

the solitary peace of pasture and rock,

the damp at the river-margins,

the smell of the larch tree,

the wind alive like a heart

beating in the crowded restlessness

of the towering araucaria.

Earth, give me back your pure gifts,

the towers of silence which rose

from the solemnity of their roots.

I want to go back to being what I have

not been,

and learn to go back from such deeps

that among all natural things

I could live or not live; it does not matter

to be one stone more, the dark stone,

the pure stone which the river bears

away.

"Is beauty a reminder of something we once knew, with poetry one of its vehicles? Does it give us a brief vision of that 'rarely glimpsed bright face behind/ the apparency of things'? Here, I suppose, we ought to try the impossible task of defining poetry. No one definition will do. But I must admit to a liking for the words of Thomas Fuller, who said: 'Poetry is a dangerous honey. I advise thee only to taste it with the Tip of thy finger and not to live upon it. If thou do'st, it will disorder thy Head and give thee dangerous Vertigos.' "

― P.K. Page (The Filled Pen)

"What I love is one foot in

front of another. South-south-west and down the contours. I go slipping

between Black Ridge and White Horse Hill into a bowl of the moor where

echoes can't get out

listen

a

lark

spinning

around

one

note

splitting

and

mending

it

and I find you in the reeds, a trickle coming out of a bark, a foal of a river"

--Alice Oswald (from "Dart," her gorgeous long poem about the River Dart in Devon)

"My poetry was born between the hill and the

river, it took its voice from the rain, and like the timber, it steeped

itself in the forests." - Pablo Neruda (in an interview, 1985)

How Poetry Comes to Me

by Gary Snyder

It comes blundering over the

Boulders at night, it stays

Frightened outside the

Range of my campfire

I go to meet it at the

Edge of the light

"Quoting Greek philosopher Plotinus, Tarnas writes, 'The stars are

like letters that inscribe themselves at every moment in the sky.

Everything in the world is full of signs. All events are coordinated.

All things depend on each other. Everything breathes together.' For me,

poetry is the music of being human. And also a time machine by which we

can travel to who we are and to who we will become." - Carol Ann Duffy

Ars Poetica

by Jorge Luis Borges

To gaze at the river made of time and water

And recall that time itself is another river,

To know we cease to be, just like the river,

And that our faces pass away, just like the water.

To feel that waking is another sleep

That dreams it does not sleep and that death,

Which our flesh dreads, is that very death

Of every night, which we call sleep.

To see in the day or in the year a symbol

Of mankind's days and of his years,

To transform the outrage of the years

Into a music, a rumor and a symbol,

To see in death a sleep, and in the sunset

A sad gold, of such is Poetry

Immortal and a pauper. For Poetry

Returns like the dawn and the sunset.

At times in the afternoons a face

Looks at us from the depths of a mirror;

Art must be like that mirror

That reveals to us this face of ours.

"This wounded Earth we walk upon

She will endure when we are gone

But still I pray that you may know

How rivers run and rivers flow..."

- Karine Polwart (from her song "Rivers Run")

"There is poetry as soon as we realize that we possess nothing." - John Cage

Publication credits: "Oh Earth, Wait for Me" by Pablo Neruda is from Pablo Neruda: Selected Poems, translated from the Spanish by Anthony Kerrigan; "How Poetry Comes to Me" by Gary Snyder is from his collection No Nature: New and Selected Poems; "Ars Poetica" by Jorge Luis Borges is from his collection Dreamtigers, translated from the Spanish by Mildred Vincent Boyers and Harold Morland.

July 22, 2013

Into the Woods, 19: The Forest of Stories (Part III)

In his memoir The Child That Books Built, Francis Spufford quotes this wonderful description of a library from Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes:

The library deeps lay waiting for them. Out in the world, not much happened. But here in the special night, a land bricked with paper and leather, anything might happen, always did. Listen! and you heard ten thousand people screaming so high only dogs feathered their ears. A million folk ran toting cannons, sharpening guillotines; Chinese, four abreast, marched on forever. Invisible, silent, yes, but Jim and Will had the gift of ears and noses as well as tongues. This was a factory of spices from far countries. Here alien deserts slumbered. Up front was the desk where the nice old lady, Miss Watriss, purple-stamped your books, but down off away were Tibet and Antarctica, the Congo....

The library deeps lay waiting for them. Out in the world, not much happened. But here in the special night, a land bricked with paper and leather, anything might happen, always did. Listen! and you heard ten thousand people screaming so high only dogs feathered their ears. A million folk ran toting cannons, sharpening guillotines; Chinese, four abreast, marched on forever. Invisible, silent, yes, but Jim and Will had the gift of ears and noses as well as tongues. This was a factory of spices from far countries. Here alien deserts slumbered. Up front was the desk where the nice old lady, Miss Watriss, purple-stamped your books, but down off away were Tibet and Antarctica, the Congo....

But Bradbury, notes Spufford, "writes as if stories burst out of their library bindings on their own. I never found that. For me, they had to be stalked, sampled, weighed, measured, sniffed, tasted, often rejected. There were so many possibilities that the different invitations each book made would have blended together, if they had been audible, into a constant muttering hum. To hear the separate call of a book, you had to take it up and detach it from all the other possibilities by concentrating on it, and giving it a little silence in which to work. Then you learned what it was offering. Be a Roman soldier, said a book by Rosemary Sutcliffe. Be an urchin in Georgian London, said Leon Garfield. Be  Milo, 'who was bored, not just some of the time but all of the time,' and drives past the purple tollbooth to the Lands Beyond. Be where you can hear cats talking by tasting the red liquid in the big bottle in the chemist shop's window. Be where magic works easily. Be where magic works frighteningly. Be where you can work magic, but have to conceal being invisible or being able to fly from the eyes of the grown-ups. Be an Egyptian child beside the Nile, be a rabbit on Watership Down, be a foundling so lonely in a medieval castle that the physical ache of it reaches to you out of the book; be one of a gang of London kids playing on a bombsite among the willowherb and loosestrife, only fifteen years or so before 1972, but already far, far in the past. Be a king. Be a slave. Be Biggles. All this was there in the library basement, if you picked up the books and coaxed them into activity, and uncountably more besides....When I made my choice, and walked back up to the Ironmarket from the library to the bus stop, I knew I might have melancholy tucked under my arm; or laughter; or fear; or enchantment.

Milo, 'who was bored, not just some of the time but all of the time,' and drives past the purple tollbooth to the Lands Beyond. Be where you can hear cats talking by tasting the red liquid in the big bottle in the chemist shop's window. Be where magic works easily. Be where magic works frighteningly. Be where you can work magic, but have to conceal being invisible or being able to fly from the eyes of the grown-ups. Be an Egyptian child beside the Nile, be a rabbit on Watership Down, be a foundling so lonely in a medieval castle that the physical ache of it reaches to you out of the book; be one of a gang of London kids playing on a bombsite among the willowherb and loosestrife, only fifteen years or so before 1972, but already far, far in the past. Be a king. Be a slave. Be Biggles. All this was there in the library basement, if you picked up the books and coaxed them into activity, and uncountably more besides....When I made my choice, and walked back up to the Ironmarket from the library to the bus stop, I knew I might have melancholy tucked under my arm; or laughter; or fear; or enchantment.

"Or longing. My favorite books were the ones that took books' explicit status as other worlds, and acted on it literally, making the window of writing a window into imaginary countries. I didn't just want to see in books what I saw anyway in the world around me, even if it was perceived and understood and articulated from angles I could never have achieved; I wanted to see things I never saw in life. More than I wanted books to do anything else, I wanted them to take me away."

Spufford was eight when he read Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy for the first time, paging quickly through Pippin and Merry's adventures in order to "get back to Sam and Frodo and the ring. I identified their journey as the story." Later, he says, "I discovered and cherished Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea novels. They were utterly different in feeling, with their archipelago of bright islands like ideal Hebrides, and their guardian wizards balancing light and dark like yin and yang. All they shared with Tolkien was the deep consistency that allows an imagined world to unfold from its premises solidly, step by certain step, like something that might really exist. Consistency is to an imaginary world as the laws of physics are to ours. The spell-less magic of Earthsea gave power to those who knew the true names of things: a beautifully simple idea. Once I had seen from the first few pages of the first book, A Wizard of Earthsea, that Le Guin was always going to obey her own rules, I could trust the entire fabric of her world."

Spufford was eight when he read Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy for the first time, paging quickly through Pippin and Merry's adventures in order to "get back to Sam and Frodo and the ring. I identified their journey as the story." Later, he says, "I discovered and cherished Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea novels. They were utterly different in feeling, with their archipelago of bright islands like ideal Hebrides, and their guardian wizards balancing light and dark like yin and yang. All they shared with Tolkien was the deep consistency that allows an imagined world to unfold from its premises solidly, step by certain step, like something that might really exist. Consistency is to an imaginary world as the laws of physics are to ours. The spell-less magic of Earthsea gave power to those who knew the true names of things: a beautifully simple idea. Once I had seen from the first few pages of the first book, A Wizard of Earthsea, that Le Guin was always going to obey her own rules, I could trust the entire fabric of her world."

Yet the books that Spufford loved best were those "that started in this world and took you to another. Earthsea and Middle Earth were separate. You traveled in them in imagination as you read Le Guin and Tolkien, but they had no location in relation to this world. Their richness did not call to you at home in any way. It did not lie just beyond a threshold in this world that you might find if you were particularly lucky, or particularly blessed.

Yet the books that Spufford loved best were those "that started in this world and took you to another. Earthsea and Middle Earth were separate. You traveled in them in imagination as you read Le Guin and Tolkien, but they had no location in relation to this world. Their richness did not call to you at home in any way. It did not lie just beyond a threshold in this world that you might find if you were particularly lucky, or particularly blessed.

"I wanted there to be a chance to pass through a portal, and by doing so to pass through rusty reality with its scaffolding of facts and events into the freedom of story. I wanted there to be doors. If, in a story, you found the one panel in the fabric of the workaday world that was hinged, and it opened, and it turned out that behind the walls of the world flashed the gold and peacock blue of something else, and you were able to pass through, that would be a moment in which all the decisions that have been taken in this world, and all the choices that had been made, and all the facts that had been settled, would be up for grabs again: all possibilities would be renewed, for who knew what lay on the other side?

"And once open, the door would never entirely shut behind you either. A kind of mixture would begin. A tincture of this world's reality would enter the other world, as the ordinary children in the story -- my representatives, my ambassadors -- wore their shorts and sweaters amid cloth of gold, and said Crumbs! and Come off it! among people speaking the high language of fantasy; while this world would be subtly altered too, changed in status by the knowledge that it had an outside."

"Storytelling draws on the magic of language to created Elsewheres," says Maria Tatar (in Enchantment Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood). "Writers use a linguistic sleight-of-hand to take an attribute, attach them to new objects, and create enchantment."

Tatar quotes this passage from J.R.R. Tolkien's famous essay "On Fairy-Stories":

Tatar quotes this passage from J.R.R. Tolkien's famous essay "On Fairy-Stories":

The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make things light and able to fly, turn grey into yellow gold, and the still rock into swifter water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood we already have an enchanter's power -- upon one plane; and the desire to wield that power in the world external to our mind awakes.

"Magic happens," says Tatar, "when the wand of language strikes a stone and makes it melt, touches a spindle and turns it into gold, or taps a trunk and makes it fly. By drawing on a syntax of enchantment that conjures fluidity, ethereality, flimsiness, and transparency, writers turn solidity into resplendent airy lightness to produce miracles of linguistic transubstantiation.

"What is the effect of that beauty? How do readers repond to words that create that beauty? In a world that has discredited that particular attribute and banished it from high art, beauty has nonetheless held on to its enlivening power in children's books. It draws readers in, then draws them to understand the fictional worlds it lights up."

This is one of the many reasons, I believe, that the best of the books published for children and young adults have devoted adult readers too (despite the baffled surprise this seems to incur in certain literary quarters). Beauty is to our age, Shirley Hazzard once said dryly, as sex was to the Victorians: a subject we don't talk about, except in the most superficial of terms. And yet we need beauty, and wonder, in our lives -- especially now, as a balancing corrective to a culture addicted to novelty and awash in irony and detachment. As the Irish poet/philosopher John O'Donohue wrote in his insightful book Beauty: The Invisible Embrace, "When our eyes are graced with wonder, the world reveals its

wonders to us. There are people who see only dullness in the world and

that is because their eyes have already been dulled. So much depends on

how we look at things. The quality of our looking determines what we

come to see."

With beauty and wonder scorned in so many of stories now told to adults (in books, in films, on television), no wonder it's to fantasy and to children's fiction that so many of us turn.

C.S. Lewis once wrote:

"When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret, and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up."

“When we are young," muses Louise Erdrich (in The Plague of Doves), "the words are scattered all around us. As they are assembled by experience, so also are we, sentence by sentence, until the story takes shape.”

We build ourselves through the stories we imbibe, both consciously and unconsciously...and it's in the latter realm that danger arises if we're not wary.

We in the West, says Rebecca Solnit , "have been muddled by Plato's assertion that art is imitation and illusion; we believe it is a realm apart, one whose impact on our world is limited, one in which we do not live. Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me, my mother liked to recite, though words hurt her all the time, and behind the words the stories about how things should be and where she fell short, as told by my father, by society, by the church, by the happy flawless women of advertisements. We all live in that world of images and stories, and most of us are damaged by some version of it, and if we're lucky, find others or make better ones that embrace and bless us." (The Faraway Nearby)

Solnit expresses so beautifully the very thing that I have long been trying to do as a writer, editor, and painter: I want find better stories, make better stories, stories that will "embrace and bless" the readers who find them.

I think that's what we're all doing here in the mythic arts field, writers and readers alike, in our many different ways.

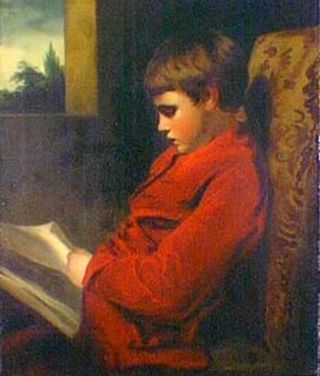

The "books and reading" art above is: "The Library Lions" by Graeme Base (Austrlian), from his book Animalia; "The Library" by Jessie Willcox Smith (American, 1853-1935 ); "Little Boy Reading a Book" by William Henry Hunt (English, 1790-1864); "The Reading Boy" by Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723-1792); Sunday Afternoon, Interior with Girl Reading" and "A Young Girl Reading" by Michael Peter Ancher ( (Danish, 1849-1927); "Captivated" by Adolphe Alexandre Lesrel (France, 1839-1929); "Study at a Reading Desk" by Lord Frederick Leighton (English, 1830-1896); "Evening Reading" by Georg Pauli (Finnish, 1855-1935); "Reading Aloud" by Julius LeBlanc Steward (American, 1855-1919); "Farmer Sitting at the Fireside and Reading" by Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890); "A Lady Reading" by Gwen John (Welsh, 1876-1939); "Man Reading," a portrait of Gustaf Dalstrom, the artist's hysband, by Frances Foy (American, 1890-1963); and "Whilst Reading," a portrait of Sofia Kramskoya, the artist's wife, by Ivan Kramskoi (Russian, 1837-1887).

All the works quoted from above are highly recommended: The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading, a charming and poignant memoir by Francis Spufford; Something Wicked This Way Comes, the classic novel by Ray Bradbury; The Enchantment Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood by the great fairy tale scholar Maria Tatar; J.R.R. Tolkien's essay "On Fairy-stories," published in his collection Leaf by Niggle (it can also be read online here, and my memoir-ish essay about the essay is here); John O'Donohue's insightful examination of beauty in life and art,

Beauty: The Invisible Embrace; Louise Erdich's fine novel The Plague of Doves; and Rebecca Solnit's gorgeous new memoir, The Faraway Nearby.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 707 followers