Terri Windling's Blog, page 181

September 12, 2013

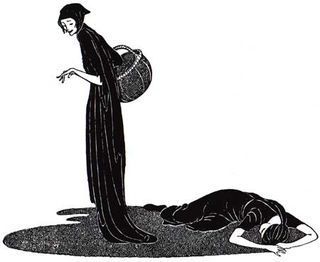

Into the Woods, 29: The Thirteenth Fairy

To finish our trio of Sleeping Beauty posts, let's turn to the figure of the Thirteenth Fairy.* This quote comes, once again, from About the Sleeping Beauty by P.L. Travers:

"The

"The

appearance of this lady at the christening is the great

moment of the tale, the hook from which everything hangs. Properly to

understand why this is so, we must turn to Wise Women in general and

their role in the world of men. To begin with, they are not mortal women. They are sisters, rather,

of the Sirens, kin to the Fates and the World Mothers. As such, as

creatures of another dimension, myth and legend have been at pains to

embody them in other than human shape -- the winged female figures of

Homer, the bird-headed women of the Irish tales, the wild women of

ancient Russian with square heads and the wisplike Jinn of the Middle

East...

"[I]t should be remembered that

no Wise Woman or Fairy is herself good or bad; she takes on one aspect

or another according to the laws of the story and the necessity of

events. The powers of these ladies are equivocal. They change with

changing circumstances; they are as swift to take umbrage as they are to

bestow a boon; they curse and bless with equal gusto. Each Wise Woman

is, in fact, an aspect of the Hindu goddess, Kali, who carries in her

multiple hands the powers of good and evil.

"It is clear, then, that the

Thirteenth Wise Woman becomes the Wicked Fairy solely for the purpose

of one particular story. It was by chance that she received no

invitation; it might just as well have been one of her sisters. So,

thrust by circumstances into the role, she acts according to law.

"Up

she rises, obstensibly to avenge an insult but in reality to thrust the

story forward and keep the drama moving. She becomes the necessary

antagonist, placed there to show that whatever is 'other,'  opposite and fearful, is as indispensable an instrument of creation as any force for

opposite and fearful, is as indispensable an instrument of creation as any force for

good. The pulling of the Devas and Asuras in opposite directions in the

Hindu myth and the interaction of the good and the bad Fairies produced

the fairy tale. The Thirteenth Wise Woman stands as guardian of the

threshold, the paradoxical adversary without whose presence no threshold

may be passed.

"This is the role played in so many other stories

by the Wicked Stepmother. The true mother, by her very nature, is bound

to preserve, protect, and comfort; that is why she is so often disposed

of before the story begins. It is the stepmother, her cold heart

unwittingly cooperating with the hero's need, who thrusts the child from

the warm hearth, out from the sheltering walls of home to find his own

true way.

"Powers such as these, at once demonic and divine, are

not to be taken lightly. They give a name to evil, free it, and bring it

into the light. For evil will out, they sharply warn us, no matter how

deeply buried. Down in its dungeon it plots and plans, waiting, like an

unloved child, the day of its revenge. What it needs, like the unloved

child, is to be recognized, not disclaimed; given its place and proper

birthright and allowed to contact and cooperate with its sister

beneficent forces. Only the integration of good and evil and the stern

acceptance of opposites will change the situation and bring about the

condition that is known as Happily Ever After. Without the Wicked Fairy there would have been no story. She, not the heroine, is the goddess in the machine."

Observing the Formalities

by Neil Gaiman

As you know, I wasn’t invited to the Christening. Get over it, you repeat.

But it’s the little formalities that keep the world turning.

My twelve sisters each had

an invitation, engraved, and delivered

By a footman. I thought

perhaps my footman had got lost.

Few invitations reach me

here. People no longer leave visiting cards. And even when they did I

And even when they did I

would tell them I was not at home,

Deploring the

unmannerliness of these more recent generations.

They eat with their mouths

open. They interrupt.

Manners are all, and the

formalities. When we lose those

We have lost everything.

Without them, we might as well be dead.

Dull, useless things. The

young should be taught a trade, should hew or spin,

Should know their place

and stick to it. Be seen, not heard. Be hushed.

My youngest sister

invariably is late, and interrupts. I am myself a stickler for

punctuality.

I told her, no good will

come of being late. I told her,

Back when we were still

speaking, when she was still listening. She laughed.

It could be argued that I

should not have turned up uninvited.

But people must be taught

lessons. Without them, none of them will ever learn.

People are dreams and

awkwardness and gawk. They prick their fingers

Bleed and snore and drool.

Politeness is as quiet as a grave,

Unmoving, roses without

thorns. Or white lilies. People have to learn.

Inevitably my sister

turned up late. Punctuality is the politeness of princes,

That, and inviting all

potential godmothers to a Christening.

They said they thought I

was dead. Perhaps I am. I can no longer recall.

Still and all, it was

necessary to observe the formalities.

I would have made her

I would have made her

future so tidy and polite. Eighteen is old enough. More than enough.

After that life gets so

messy. Loves and hearts are such untidy things.

Christenings are raucous

times and loud, and rancorous,

As bad as weddings.

Invitations go astray. We’d argue about precedence and gifts.

They would have invited me

to the funeral.

* There is some diagreement about which

fairy, in the story's cast, should be called the Thirteenth Fairy. For some, the designation belongs to the uninvited, malevolent

fairy who curses the infant princess with death. For others, it's the

very last fairy to bestow her gift, mitigating the wicked fairy's

curse by turning "death" into "sleep." For the purposes of this post, I'm using the former definition.

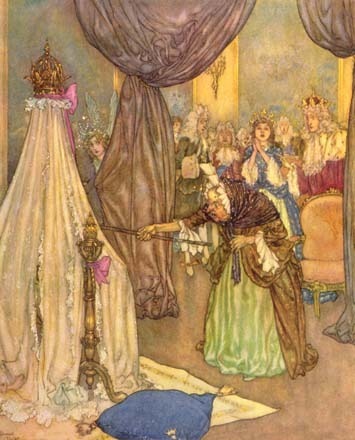

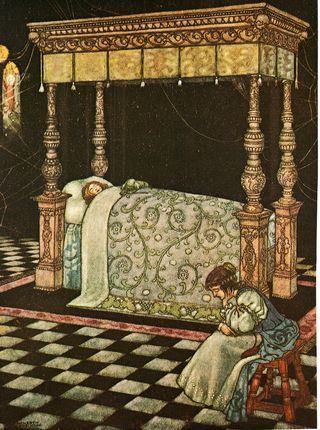

The images above are: Two views of "Sleeping Beauty, Scene 1," doll art by Anna Brahms (Israeli/American); "Sleeping Beauty," paper cut art by Su Blackwell (English); "The Thirteenth Fairy" by Harry Clarke (Irish, 1189-1931) Errol Le Cain (English, 1941-1989); "Sleeping Beauty and the Spinning Wheel" by Trina Schart Hyman (American, 1939-2004); two illustrations by Jennie Harbour (English, 1893-1959); "Sleeping Beauty, Scene 2" by Anna Brahms; and "Sleeping Beauty and the Spinning Wheel" by Edmund Dulac (French, 1882-1953). The poem is copyright 2009 by Neil Gaiman; it first appeared in Trolls Eye View (Datlow & Windling, eds).

September 11, 2013

Into the Woods, 28: Fairy Blessings

From About the Sleeping Beauty by P.L. Travers:

"Are there thirteen Wise Women at every christening? I think it very likely. I think, too, that whatever gifts they give are over and above those that life offers. If it is beauty it is of some supplementary kind that is not dependent on fine eyes and a perfect nose, though it may include these features. If it is wealth, it comes from some inner abundance that has no relation to pearls and rubies, though the lucky ones may get these too.

it comes from some inner abundance that has no relation to pearls and rubies, though the lucky ones may get these too.

"I shall never know which good lady it was who, at my own christening, gave me the everlasting gift, spotless amid all spotted joys, of love for the fairy tale. It began in me quite early, before there was any separation between myself and the world. Eve's apple had not yet been eaten; every bird had an emperor to sing to and any passing beetle or ant might be a prince in disguise....

"Perhaps we are born knowing the tales, for our grandmothers and all their ancestral kin continually run about in our blood repeating them endlessly, and the shock they give us when we first hear them is not of surprise but of recognition. Things long unknowingly known have suddenly been remembered. Later, like streams, they run underground. For a while they disappear and we lose them. We are busy, instead, with our personal myth in which the real is turned to dream and the dream becomes the real. Sifting this is a long process. It may perhaps take a lifetime and the few who come around to the tales again are those who are in luck."

There were twelve fairies at the feast. Never

Thirteen. The day the queen gave birth, the king

Sent out twelve messengers on horses,

One to each of us, begging us

To bless her, name her, crown her with our favor.

So we came.

There was a banquet — well, there'd have to be,

With jewelled plates and cups, the usual fee

For fairy-godmothering. My sisters returned

The usual gifts: Beauty. Wit. A lovely voice.

Goodness (of course). Good taste (that was Martha,

Wincing at the jewelled cups, the queen's gown).

Grace. Patience. An ear for music. Dexterity

(To help her learn Princessly skills, as sewing

Dancing, playing the lute). Amiability.

Intelligence.

I meant to give her a long life.

I raised my wand and caught her eyes. They were

Gray and awake. Her cheeks were flushed with pink,

Her hair transparent down. She batted at

My wand and laughed. The court transfixed me

With expectant eyes — the king and queen,

My sisters, ladies, nobles, serving men,

Waiting for my gift. I considered

Her life, her marriage to a prince raised

Blind to the world behind the jewelled cups,

And said, "Sweet child, I give your life to you

To lead as you will, to go or stay, to use

My sisters' gifts, or let them be. Rule

In your own right, consortless and free.

If you choose."

The king raged; the queen wept; my sisters

Stood aghast. Not marry? The kiss of death,

A harsher curse than marriage to a frog,

Or kissing a hedgehog, or serving a witch, or even

Herding geese, since all these led to mating.

As a good fairy, I did what I could; I gave her

A hundred years' sleep, a hedge of briars, a spell

That would sort her suitors, test them for grace,

For patience, for wit and intelligence and good taste,

For amiability and a lovely voice.

A man who would be her mate,

Not her master.

Images above: Two faires by Edmund Dulac (French, 1882-1953), "Places Were Set for Twelve Fairies" from The Ideal Fairy Tales, artist unknown; "Sleeping Beauty" from The Nursery Picture Book, artist unknown; "Sleeping Beauty" by Margaret Tarrant (English, 1888-1959); "A Spray of Hemlock" by Jessie Marion King (Scottish, 1875-1949); and "The Faery Godmother" by Brian Froud (English, contemporary). The poem is copyright 1999 by Delia Sherman, and has appeared in Silver Birch, Blood Moon and The Journal of Mythic Arts.

September 10, 2013

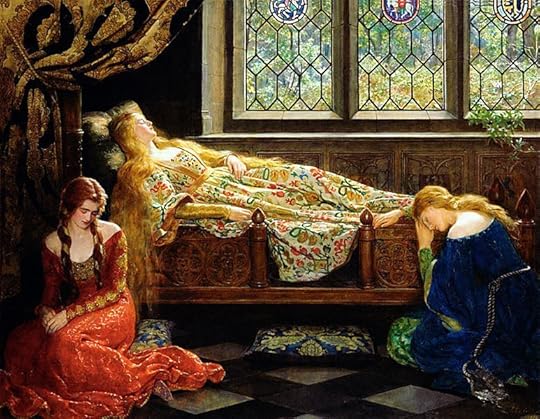

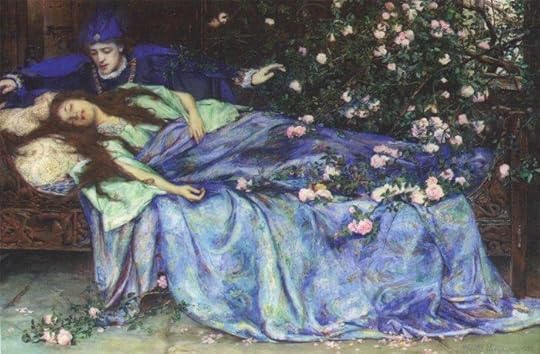

Into the Woods, 27: Enchanted Sleep

In her article on the "Sleeping Beauty" fairy tale, Midori Snyder wrestles with her ambivalent feelings towards its problematic protagonist. Out of all the brave, bold, and clever heroines to be found throughout the fairy tale canon, why (she asks) are we still so intrigued by a princess who swoons and sleeps and awaits a man's rescue? To better understand the story's tenacious hold on our imaginations, she turns to its oldest known variants -- one of which is "The 9th Captain's Tale," from The Book of the 1001 Nights:

"Despite an exotic Eastern setting, it begins with familiar

"Despite an exotic Eastern setting, it begins with familiar

conflict," Midori writes. "A woman longs for a child and declares, 'Give me a daughter,

even if she can't endure the odor of flax.' Her wish is granted and a

daughter is born. As she grows, the Sultan's son is taken with her

beauty and begins to court her. Then, in a mishap, the girl's hand

touches flax and she falls into a death–like sleep. Her distraught

parents transport her incorruptible body to an elaborate shrine on an

island.

The Sultan's son, still very much in love with her, comes to visit

her shrine. A kiss awakens the sleeping maiden and they have sexual

relations for forty days.

"But the Sultan's son cannot remain on the island indefinitely,

and eventually he abandons her. Angry, the young woman uses the magic

ring of Solomon and wishes for a palace to be built next door to the

Sultan's. She also wishes to be transformed into an even greater beauty,

unrecognizable and irresistible to her former lover. The Sultan's son

is quick to discover his exquisite neighbor and falls in love. He sends

her gifts, which she discards — feeding the gold to her chickens and

using the bolts of fine fabrics as rags. Desperate, the Sultan's son

begs to know how he can prove that he is worthy enough to be her

husband. She tells him that he must wrap himself in a shroud and allow

himself to be buried on the palace grounds and mourned as dead. The

young man agrees and permits his parents to dress him in funeral

clothing and bury him. His mother sits by the grave and mourns his

death. Satisfied, the young woman comes to the palace, retrieves the

Sultan's son from his grave, and reveals her true identity. 'Now I know,' she says, 'that you will go to any length for the

woman you love.'

"What is startling about this old version of Sleeping Beauty is

that the tale is about both of the lovers and both of their journeys of

transformation. Each one experiences a death, an end to their lives as

children. Two sets of parents prepare their children for funerals; two

sets of parents mourn the loss of a beloved child. The Sultan's son is

responsible for awakening Sleeping Beauty, but their subsequent

relationship is not an adult one — it is not sanctioned by the social

bonds of the community.

When she comes to him again, she is changed — transformed by the

fantastic. The Sultan's son, in accepting her condition of marriage, has

also accepted that his privileged life as a child must end. When she

revives him from the dead, they are now equal and their marriage is one

between adults. Who could not admire this Sleeping Beauty? She is a

divine bride sprung from the fantastic, incorruptible in death, able to

call upon magic to perform at her will a clever trick to test her future

husband. He dies and is buried in the earth

and her final act of reviving him only emphasizes her creative

powers and her fertility. He is a Sultan's son but she, confident in her

own power, is equal to him."

In Europe, the oldest known version of the story is "The Sun, the Moon, and Talia," scribed by the Italian writer and coutier Giambattista Basile (c. 1575 - 1632), published posthumously by the author's sister in a collection now known as The Pentamerone. Midori writes:

"In Basile's version (learned from women storytellers in the

countryside near Naples), Sleeping Beauty,

known as Talia, falls into a death–like sleep when a splinter of

flax is embedded under her fingernail. She sleeps alone in a small house

hidden deep within the forest. One day a King goes out hawking and

discovers  the sleeping maiden. Finding her beautiful, and unprotesting,

the sleeping maiden. Finding her beautiful, and unprotesting,

he has sex with her -- while Talia, oblivious to the King's ardent

embraces, sleeps on.

The King leaves the forest, returning not only to his castle but

also to his barren wife. Nine months later a sleeping Talia gives birth

to twins named Sun and Moon. One of the hungry infants, searching for

his mother's breast, suckles her finger and pulls out the flax splinter.

Freed of her curse by the removal of the splinter, Talia wakes up and

discovers her children.

"After a time, the King goes back to the forest and finds Talia

awake, tending to their son and daughter. Delighted, he brings them home

to his estate -- where his barren wife, naturally enough, is bitter and

jealous. As soon as the King is off to battle, the wife orders her cook

to murder Sun and Moon, then prepare them as a feast for her unwitting

husband. The kindhearted cook hides

the children and substitutes goat in a dizzying variety of dishes.

The wife then decides to murder Talia by burning her at the stake. As

Talia undresses, each layer of her fine clothing shrieks out loud (in

other versions, the bells sewn on her seven petticoats jingle).

Eventually the King hears the sound and comes to Talia's rescue. The

jealous wife is put to death, the cook reveals the children's hiding

place,

and the King and Talia are united in a proper marriage.

"Later in the 17th century, a French civil servant named Charles

Perrault wrote his own version of Sleeping Beauty based in part on

Basile's story. Fairy tale scholar Marina Warner (in From the Beast to the Blonde)

notes rather wryly that while rape and adultery were too scandalous for

Perrault, he had no problems with the cannibalism of the Italian

version. Perrault changed the King and his first

wife into a Prince and his dreadful mother: an ogress with a

terrible temper and a fondness for human flesh. Beauty's children are to

be served up in a gourmet sauce, and then Beauty herself is to be

butchered. But the kind  cook fools the ogress, hiding Beauty and her

cook fools the ogress, hiding Beauty and her

children and serving a kid, a lamb and a hind in their places. When the

ogress discovers the truth, she becomes enraged and makes plans to throw

them all into a pot of vipers and toads.

Once again the Prince arrives in time to save his lover from harm --

throwing his mother into the pot instead, destroying her .

"These European versions show a shift in emphasis from the older

Arabian narrative. Sleeping Beauty is still the centerpiece of the tale --

but less as an actor and more as an object of power to be acquired,

even at the expense of one's marriage and one's mother. The European tales seem to be focused on the men, not the

slumbering heroine. The need for an heir (first by her father, and then

by the younger King who wakes her) is pivotal here.

Basile spares not a moment of sympathy for the dishonored first

wife of the younger King. Her barrenness defines her as evil, and her

replacement by the fertile magical bride is a triumph. Talia, on the

other hand, is able to give birth even while she lies in the semblance

of death -- making her not quite human but almost a supernatural creature -- and making her impregnation not a crime (the rape it appears to our

modern eyes), but the act through which the King engages with the

fantastic,

simultaneously proving his virility.

"Sleeping Beauty underwent more changes in the mid-19th century when

"Sleeping Beauty underwent more changes in the mid-19th century when

the Brothers Grimm published their version, "Little Briar Rose," in

fairy tale collections aimed at children and their parents. [The Basile and Perrault stories had been published for adult readers.] While the Grimms retained some

of the dark imagery from the oral storytelling tradition, the sexuality

and bawdy humor of the tales all but disappeared.

"In late-19th century

England, Victorian publishers further sanitized fairy tales, toning down

the violence yet again and simplifying the narratives.

Victorian readers wanted these stories to be charming, to reflect

the gender roles of the time, and above all to instruct proper upper-

and middle-class children in appropriate morality. Innuendo replaced the

overt and troubling activity of carnal sex and violence. . .but as

modern writers from Angela Carter to Marina Warner have pointed out,

these underlying themes are tenacious.

"Looking at the Grimms' version in its original German, folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkl points to

"Looking at the Grimms' version in its original German, folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkl points to

a staccato list of suggestive language: the hedge is 'penetrated,'

Briar Rose is 'pricked,' and she sleeps not in a shrine or a wooded

cottage but enclosed within a phallic tower. And yet on the surface, the

narrative remains almost painfully chaste. The Prince need not even

kiss her to wake her -- he merely bends on one knee beside her bed. Sleeping Beauty is also diminished in other ways in these later, more

'civilized' versions. Earlier variants suggest that the father is the

character most at fault,

bringing the curse down on his daughter through improper dealings

with the fantastic (such as slighting an important fairy). But Victorian

versions seem to suggest the girl is responsible for her own fate,

punished for her disobedience to her father's command not to touch the

spinning wheel. In these versions, it is not only Briar Rose who

suffers, but her parents and the entire court who must sleep for a

hundred years. (One can imagine that to the class-obsessed Victorians, a

privileged daughter handling the tools of the lower classes

provoked alarm, threatening to lower the status of the family.

Briar Rose's sin can only be expiated when a man worthy enough, both in

heart and noble status, redeems her from her transgression -- restoring

both the princess and her family to its former social position.)

"What, then, became of Sleeping Beauty as she

entered the 20th century? And what does the fairy tale mean to us now, in our

post–industrial age? The modern response to the theme

has proven to be as varied as the individual artists drawn to the old

narrative. Sleeping Beauty no longer speaks to a common

identity, a single icon to shape the female image for new generations.

Instead, our Princess finds herself portrayed in many different guises:

as a helpless 1950s stay–at–home girl, a bold space opera heroine, an

oppressed time–traveling queen,

a stoic Holocaust survivor, a sexually abused child, and myriad

others. Her tale ranges in tone from unbearably bright to

psychologically dark and sinister, reflecting modern ambiguity

toward female sexual roles and women's identity."

(You can read Midori's full essay here.)

In her marvellous little book About the Sleeping Beauty, P.L. Travers (folklorist, and author of Mary Poppins) presents several different versions of the princess's story, and reflects on the symbolism of the tale:

"The idea of the sleeper," says Travers, "of somebody hidden from the mortal eye,

waiting until time shall ripen has always been dear to the folky mind; Snow White asleep in her glass coffin, Brynhild behind her wall of

fire, Charlemagne at the heart of  France, King Arthur in the Isle of

France, King Arthur in the Isle of

Avalon, Frederick Barbarossa under his mountain in Thuringia.

Muchukunda, the Hindu King, slept through eons till he was wakened by

the Lord Krishna; Oisin of Ireland dreamed in Tir n'an Og for over three

hundred years. Psyche in her magic sleep is a type of Sleeping Beauty,

Sumerian Ishtar in the underworld may be said to be another. Holga the

Dane is sleeping and waiting, and so, they say, is Sir Francis Drake.

Quetzalcoatl of Mexico and Virochocha of Peru are both sleepers. Morgan

le Fay of France and England and Dame Holle of Germany are sleeping in

raths and cairns. The theme of the sleeper is as old as the memory of

man....

"[I]f the fairy tale characters are our prototypes -- which is what

they are designed to be -- we must come to the point where we are forced

to relate the stories and their meanings to ourselves. No amount of

rationalizing will bring us to the heart of the fairy tale. To enter it

one must be prepared to let rational reason go. The stories have to be

loved for themselves before they will release their secrets. So, face

to face with the Sleeping  Beauty...we find ourselves compelled to ask:

Beauty...we find ourselves compelled to ask:

what is it in us that at certain moments suddenly falls asleep?

Who lies hidden deep within us? And who will come to wake us, what

aspect of ourselves?

"Are we dealing here with the sleeping soul and all the external affairs of life that hem it in and hide it; something that falls asleep after childhood, something that not to waken would make life meaningless? To give an answer, supposing we had it, would be breaking the law of fairy tale. And perhaps no answer is necessary. It is enough that we ponder upon and love the story and ask ourselves the question."

"We sleep," says David Abram (in Becoming Animal), "allowing gravity to hold us, allowing Earth -- our larger body --

to recalibrate our neurons, composting the keen encounters of our waking

hours (the tensions and terrors of our individual days), stirring them

back, as dreams, into the sleeping substance of our muscles. We give

ourselves over to the influence of the breathing earth. Sleep is the

shadow of the earth as it seeps into our skin and spreads throughout our

limbs, dissolving our individual will into the thousand and one selves

that compose it -- cells, tissues, and organs taking their prime

directives now from gravity and the wind -- as residual bits of sunlight,

caught in the long tangle of nerves, wander the drifting landscape of

our earth-borne bodies like deer moving across the forested valleys."

"She knew no greater

pleasure than that moment of passage into the other place, when her

limbs grew warm and heavy and the sparkling darkness behind her lids

became ordered and doors opened; when conscious thought grew owl's wings

and talons and became other than conscious." - John Crowley (Little, Big)

"We don’t sleep to sleep, dammit, any more than we eat to eat. We sleep

to dream. We’re amphibians. We live in two elements and we need both." - Lindsay Clarke (The Chymical Wedding)

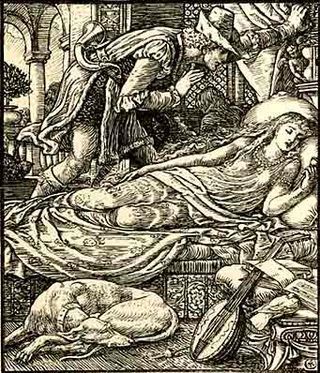

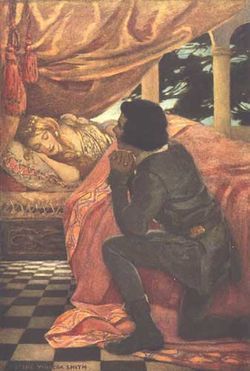

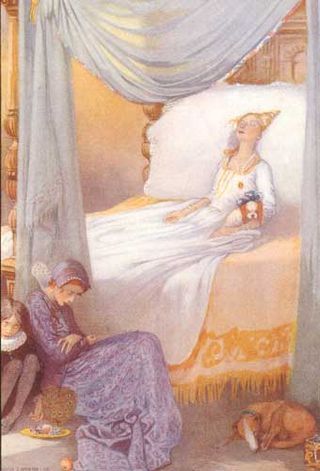

The Sleeping Beauty / Briar Rose art above is by: Arthur Wardle (English, 1860-1949), Edmund Dulac (French, 21882-1953), William Author Brakespeare (English, 1855-1914), Viktor Vasnetsov (Russian, 1848 - 1926), John Collier (English, 1850-1934), Walter Crane (English, 1845-1915), Richard Eisermann (German, 1853-1927), Edmund Dulac again, Henry Meynell Rheam (English, 1859-1920), Jessie Willcox Smith (American, 1863-1935), Margaret Evans Price (American, 1888-1973), Warwick Goble (English, 1862-1943), Ann MacBeth (Scottish, 1875-1948), and Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833-1898): studies and some of the final panels for "The Legend of Briar Rose."

September 9, 2013

Into the Woods, 26: As Necessary as Breathing and Sleeping

Below, three juicy excerpts from "Fairy Stories," an essay by A.S. Byatt (first published as the introduction to her

story collection The Djinn in the Nightingale's Eye):

"Fairy stories are related to dreams, which are maybe most people's first experience of unreal

narrative, and to myths. Realism is related to explanations and

orderings -- the tale of the man in the bar who tells you the story of

his life, the historian who explains the decisions of generals and the

decline of economies. Great  novels, I believe, always draw on both ways

novels, I believe, always draw on both ways

of telling, both ways of seeing. But because realism is agnostic and sceptical, human and reasonable, I have always felt it was what I ought

to do. And yet my impulse to write came, and I know it, from years of

reading myths and fairytales under the bedclothes, from the delights and

freedoms and terrors of worlds and creatures that never existed."

"There has recently been a great variety of interest in fairy stories.

The early psychoanalysts studied their relations to dreams and the

unconscious, and Bruno Bettelheim's The Uses of Enchantment

provides one description of the use of these stories in a culture -- a

description which is both exciting and limited. It is clear that an

explanation of The Sleeping Beauty in terms of the adolescent

girl's characteristic pre-sexual torpor is inspired and to the point -- but it isn't adequate, it doesn't do away with the enchantment of the

thicket of roses, or even the mystery of the bead of blood on the

pricked finger. Marina Warner has recently pointed out that the figure

of the usurping stepmother was dreadfully real in medieval and Renaissance societies, where so many women died in childbirth, leaving

children, but that does not explain away our terror of the hostile

parent, or  the witch. Modern feminists have used the 'irrationality' of

the witch. Modern feminists have used the 'irrationality' of

fairy tales to explore female desires and dreams; they have also

rewritten narratives to provide powerful heroines, sometimes arguing

that all women in the original fairy tales were meek victims, which is

simply not true. There are plenty of resourceful princesses and peasants

and goddesses -- that is one of the pleasures of the other world. Salman

Rushdie and others have used the fairy tale both to give an edge of

satiric licence to a picture of particular societies, and to play with

reality and fantasy as all societies have always done. The literary

fairy tale is a wonderful, versatile hybrid form, which draws on

primitive apprehensions and narrative motifs, and then uses them to

think consciously about human beings and the world. Both German Romantic

fairy tales and the self-conscious playful courtly stories of

seventeenth-century French ladies, combine the new thought of the time with the ancient tug of forest and castle, demon and witch, vanishing and shape-shifting, loss and restoration."

" 'Never trust the teller, trust the tale,' said D.H.Lawrence, in a

phrase which has been remembered because it accords with readers'

deepest instincts. What I have always believed is that the human

imagination, given any scene, any two people, any danger, any love, any

fear, will start elaborating, inhabiting, touching, tasting, feeling.

Fairy stories rely most simply and most powerfully on the imaginations

of readers and hearers, who create and recreate worlds, old and known in

part, new and unknown in part. Professional storytellers in Britain, a

thriving profession, believe the oral is more powerful than the written,

in this regard, and believe also that all great storytelling must

retell old and shared stories, the tales of Grimm and the epic of

Gilgamesh, that the new, individual insights of the literary fairytale

do not have the power or the common wisdom to compel our assent. I don't

believe that myself -- but I do believe that it is what is old in the new

that compels assent for the new -- that the Forest and the Dragon call up

worlds in which we can think about our own histories and life-stories.

Making up worlds is as natural and as necessary to human beings as

breathing and sleeping."

(You can read Byatt's whole essay here.)

The sleepy art above is by John D. Batten (English, 1860 - 1932), Honor Appleton (English, 1879-1951), William Heath Robinson (English, 1872-1944), Katerina Plotnikova (Russian, contemporary), Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1883-1898), Lisbeth Zwerger (Austrian, contemporary), and Anna Brahms (Israeli/American, contemporary).

September 8, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's tunes are from the British folk duo Josienne Clarke and Ben Walker, a classically trained vocalist and guitarist who infuse their mix of original, classic, and traditional songs with exquisite musicianship. Their lovely new CD, "Fire and Fortune," just came out in July.

Above: "Who Knows Where the Time Goes," the bitter-sweet folk anthem penned by the late, great Sandy Denny (recorded by Denny and Fairport Convention in '69) -- which seems suitable for a cold, misty morning here in Devon, as summer transitions rather abruptly into autumn.

Below: "My Love is Like a Red Red Rose," with lyrics by Robert Burns (late 18th century). Both videos were filmmed at the Bournemouth Folk Club in April.

And last: "Anyone But Me," a love-gone-wrong song written by Clarke herself, from the new CD. This performance was filmed at the Cambridge Folk Festival in July.

By the way, if you love traditional folk songs as much as I do, check out the new Song Collectors Collective site (via the amazing Sam Lee).

Recommended Reading

Grace Nuth alerted me to this beautiful post: "Dirt-Sense, Animal-Speak and Origin" by Aleah Sato. If you can get through the entire text with dry eyes, you're a better man than I.

"I grew up surrounded by magic," writes Sato. "As a little girl...I’d spend

hours conversing with trees, an old mare, feral cats, birds, spiders and

the moon that took me in like a lullaby, like a poem I could believe.

It never occurred to me that there was something strange about wishing

over weeds, speaking to the setting sun. As a child of field and

wildflower, I loved the freedom of communicating in ways that stretched

the impulse and ideal of communication, of the human alphabet. I

believed in possibility and transcendence. I still do."

Sato had me from the very beginning (with quotes from two of my favorite writers), and the piece just gets better from there....

Other recommendations:

* "Mythically Speaking" by John Patrick Pazdziora, on his blog The Paradoxes of Mr. Pond; and a follow-up post, "Mythically Thinking," by Jane Yolen and John on the Unsettling Wonders blog.

* "Joy" by Zadie Smith, published in The New York Review of Books, back in January. It's somehow taken me all this time to read it, and it's a delight. A follow-up: "Happiness" by Jane Kenyon, in Poetry Magazine.

* "Virtues of Madness and Vices," a beautiful interview with poet Mary Ruefle by David Andrew King, in The Kenyon Review.

* "What I Learned from Thomas Edison and Steven Soderbergh and How it Applies to Novelists" by Julianna Baggott, on the Writer Unboxed blog.

The magical images above are by Russian surrealist photographer Katerina Plotnikova, based in Moscow.

September 5, 2013

Radical amazement

"Our

goal should be to live life in radical amazement. Get up in the morning

and look at the world in a way that takes nothing for granted.

Everything is phenomenal. Everything is incredible. Never treat life

casually. To be spiritual is to be amazed.” - Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-1972)

(Click on the photos for larger versions, which are much nicer when they're in landscape format.)

(Click on the photos for larger versions, which are much nicer when they're in landscape format.)

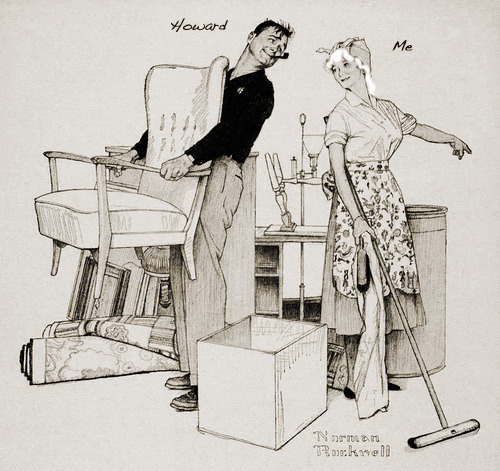

Moving Day, Chagford Style

Hallelujah! My mother-in-law's move is now over, and she's in her new home, Nonesuch Cottage, at last! It's just up the road from the old place, but it's all her own, and that makes a difference.

The picture above was taken on Moving Day morning, in the car park ("parking lot," for American readers) behind the Victorian building of flats that we've just moved her out of. That's our fabulous Moving Crew of friends, neighbors, and Chagford Filmmaking Group members above: Corrie, Rob, Deirdre, Jenny (my mother-in-law, in pink), Elizabeth-Jane, Ruth, Howard, and Jason. A big thank you to them all -- and also to Brian and Finn, who aren't pictured here. (And to Rima, Damien, Magda, Elaine, Virginia, and Marica, who helped out in the run-up to the move.)

The picture below was taken in the middle of the day, when we found ourselves (due to slow-moving banks) with a two hour gap between the time the old flat had to be vacated and the time when the keys to the new place would arrive. The move ground to an abrupt halt...but instead of despairing, we simply stopped for a lovely al fresco lunch in the car park. Elizabeth-Jane provided the dishes, cutlery, and an outrageously delicious home-cooked meal (a casserole of local vegetables, bread hot from the oven, and a large wheel of Brie), served with good conversation, a great deal of laughter, and plenty of late summer sunshine.

By supper time, thanks to everyone's hard work, Jenny was ensconsed in Nonesuch Cottage at last. Once again, Elizabeth-Jane provided the Moving Crew with a fabulous feast: an Italian meat pie with four kinds of cheeses, a salad of local produce, more fresh-baked bread, and a cake for dessert. Here she is carrying the Famous Pie through the back door of Jenny's barn, followed by Tilly and young Finn:

Once again we dined al fresco, but this time we sat in Jenny's peaceful new garden, surrounded by flowers instead of furniture, boxes, and trucks.

Below, a toast to Jenny's new house...and to friends and community who make life so sweet.

September 4, 2013

A moment's pause for adorableness....

The last time we helped my mother-in-law move was back in 2009, when she left her 30-year home in Oxfordshire to come down to Chagford. Tilly was just a wee pup then, and the journey up to Oxfordshire and back was her first long car ride. Here she is, sleeping in her traveling bed in Jenny's Oxfordshire kitchen. I came across this old photo recently, and it's too adorable not to share....

September 1, 2013

Moving update...

After a week of hard work (thank you everyone who's helped!), my mother-in-law is packed up and ready to move into her new cottage tomorrow morning. Oh, how we're praying for a nice dry day! We've got many, many boxes of books, fabrics, antique china, and theatre costumes to haul; furniture to maneuver up narrow, winding stairs; and paintings to transport gently (Howard's grandmother, Ruth Sudbury-Palmer, was a landscape artist)...but there will also be food and cake (thanks to the kind harpist across the road), and by nightfall it will all be done.

On Wednesday I plan to collapse, and I'll back in the studio by Thursday. See you then!

Tilly in the studio garden, waiting to get back to our usual daily routine...

Tilly in the studio garden, waiting to get back to our usual daily routine...

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers