Into the Woods, 27: Enchanted Sleep

In her article on the "Sleeping Beauty" fairy tale, Midori Snyder wrestles with her ambivalent feelings towards its problematic protagonist. Out of all the brave, bold, and clever heroines to be found throughout the fairy tale canon, why (she asks) are we still so intrigued by a princess who swoons and sleeps and awaits a man's rescue? To better understand the story's tenacious hold on our imaginations, she turns to its oldest known variants -- one of which is "The 9th Captain's Tale," from The Book of the 1001 Nights:

"Despite an exotic Eastern setting, it begins with familiar

"Despite an exotic Eastern setting, it begins with familiar

conflict," Midori writes. "A woman longs for a child and declares, 'Give me a daughter,

even if she can't endure the odor of flax.' Her wish is granted and a

daughter is born. As she grows, the Sultan's son is taken with her

beauty and begins to court her. Then, in a mishap, the girl's hand

touches flax and she falls into a death–like sleep. Her distraught

parents transport her incorruptible body to an elaborate shrine on an

island.

The Sultan's son, still very much in love with her, comes to visit

her shrine. A kiss awakens the sleeping maiden and they have sexual

relations for forty days.

"But the Sultan's son cannot remain on the island indefinitely,

and eventually he abandons her. Angry, the young woman uses the magic

ring of Solomon and wishes for a palace to be built next door to the

Sultan's. She also wishes to be transformed into an even greater beauty,

unrecognizable and irresistible to her former lover. The Sultan's son

is quick to discover his exquisite neighbor and falls in love. He sends

her gifts, which she discards — feeding the gold to her chickens and

using the bolts of fine fabrics as rags. Desperate, the Sultan's son

begs to know how he can prove that he is worthy enough to be her

husband. She tells him that he must wrap himself in a shroud and allow

himself to be buried on the palace grounds and mourned as dead. The

young man agrees and permits his parents to dress him in funeral

clothing and bury him. His mother sits by the grave and mourns his

death. Satisfied, the young woman comes to the palace, retrieves the

Sultan's son from his grave, and reveals her true identity. 'Now I know,' she says, 'that you will go to any length for the

woman you love.'

"What is startling about this old version of Sleeping Beauty is

that the tale is about both of the lovers and both of their journeys of

transformation. Each one experiences a death, an end to their lives as

children. Two sets of parents prepare their children for funerals; two

sets of parents mourn the loss of a beloved child. The Sultan's son is

responsible for awakening Sleeping Beauty, but their subsequent

relationship is not an adult one — it is not sanctioned by the social

bonds of the community.

When she comes to him again, she is changed — transformed by the

fantastic. The Sultan's son, in accepting her condition of marriage, has

also accepted that his privileged life as a child must end. When she

revives him from the dead, they are now equal and their marriage is one

between adults. Who could not admire this Sleeping Beauty? She is a

divine bride sprung from the fantastic, incorruptible in death, able to

call upon magic to perform at her will a clever trick to test her future

husband. He dies and is buried in the earth

and her final act of reviving him only emphasizes her creative

powers and her fertility. He is a Sultan's son but she, confident in her

own power, is equal to him."

In Europe, the oldest known version of the story is "The Sun, the Moon, and Talia," scribed by the Italian writer and coutier Giambattista Basile (c. 1575 - 1632), published posthumously by the author's sister in a collection now known as The Pentamerone. Midori writes:

"In Basile's version (learned from women storytellers in the

countryside near Naples), Sleeping Beauty,

known as Talia, falls into a death–like sleep when a splinter of

flax is embedded under her fingernail. She sleeps alone in a small house

hidden deep within the forest. One day a King goes out hawking and

discovers  the sleeping maiden. Finding her beautiful, and unprotesting,

the sleeping maiden. Finding her beautiful, and unprotesting,

he has sex with her -- while Talia, oblivious to the King's ardent

embraces, sleeps on.

The King leaves the forest, returning not only to his castle but

also to his barren wife. Nine months later a sleeping Talia gives birth

to twins named Sun and Moon. One of the hungry infants, searching for

his mother's breast, suckles her finger and pulls out the flax splinter.

Freed of her curse by the removal of the splinter, Talia wakes up and

discovers her children.

"After a time, the King goes back to the forest and finds Talia

awake, tending to their son and daughter. Delighted, he brings them home

to his estate -- where his barren wife, naturally enough, is bitter and

jealous. As soon as the King is off to battle, the wife orders her cook

to murder Sun and Moon, then prepare them as a feast for her unwitting

husband. The kindhearted cook hides

the children and substitutes goat in a dizzying variety of dishes.

The wife then decides to murder Talia by burning her at the stake. As

Talia undresses, each layer of her fine clothing shrieks out loud (in

other versions, the bells sewn on her seven petticoats jingle).

Eventually the King hears the sound and comes to Talia's rescue. The

jealous wife is put to death, the cook reveals the children's hiding

place,

and the King and Talia are united in a proper marriage.

"Later in the 17th century, a French civil servant named Charles

Perrault wrote his own version of Sleeping Beauty based in part on

Basile's story. Fairy tale scholar Marina Warner (in From the Beast to the Blonde)

notes rather wryly that while rape and adultery were too scandalous for

Perrault, he had no problems with the cannibalism of the Italian

version. Perrault changed the King and his first

wife into a Prince and his dreadful mother: an ogress with a

terrible temper and a fondness for human flesh. Beauty's children are to

be served up in a gourmet sauce, and then Beauty herself is to be

butchered. But the kind  cook fools the ogress, hiding Beauty and her

cook fools the ogress, hiding Beauty and her

children and serving a kid, a lamb and a hind in their places. When the

ogress discovers the truth, she becomes enraged and makes plans to throw

them all into a pot of vipers and toads.

Once again the Prince arrives in time to save his lover from harm --

throwing his mother into the pot instead, destroying her .

"These European versions show a shift in emphasis from the older

Arabian narrative. Sleeping Beauty is still the centerpiece of the tale --

but less as an actor and more as an object of power to be acquired,

even at the expense of one's marriage and one's mother. The European tales seem to be focused on the men, not the

slumbering heroine. The need for an heir (first by her father, and then

by the younger King who wakes her) is pivotal here.

Basile spares not a moment of sympathy for the dishonored first

wife of the younger King. Her barrenness defines her as evil, and her

replacement by the fertile magical bride is a triumph. Talia, on the

other hand, is able to give birth even while she lies in the semblance

of death -- making her not quite human but almost a supernatural creature -- and making her impregnation not a crime (the rape it appears to our

modern eyes), but the act through which the King engages with the

fantastic,

simultaneously proving his virility.

"Sleeping Beauty underwent more changes in the mid-19th century when

"Sleeping Beauty underwent more changes in the mid-19th century when

the Brothers Grimm published their version, "Little Briar Rose," in

fairy tale collections aimed at children and their parents. [The Basile and Perrault stories had been published for adult readers.] While the Grimms retained some

of the dark imagery from the oral storytelling tradition, the sexuality

and bawdy humor of the tales all but disappeared.

"In late-19th century

England, Victorian publishers further sanitized fairy tales, toning down

the violence yet again and simplifying the narratives.

Victorian readers wanted these stories to be charming, to reflect

the gender roles of the time, and above all to instruct proper upper-

and middle-class children in appropriate morality. Innuendo replaced the

overt and troubling activity of carnal sex and violence. . .but as

modern writers from Angela Carter to Marina Warner have pointed out,

these underlying themes are tenacious.

"Looking at the Grimms' version in its original German, folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkl points to

"Looking at the Grimms' version in its original German, folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkl points to

a staccato list of suggestive language: the hedge is 'penetrated,'

Briar Rose is 'pricked,' and she sleeps not in a shrine or a wooded

cottage but enclosed within a phallic tower. And yet on the surface, the

narrative remains almost painfully chaste. The Prince need not even

kiss her to wake her -- he merely bends on one knee beside her bed. Sleeping Beauty is also diminished in other ways in these later, more

'civilized' versions. Earlier variants suggest that the father is the

character most at fault,

bringing the curse down on his daughter through improper dealings

with the fantastic (such as slighting an important fairy). But Victorian

versions seem to suggest the girl is responsible for her own fate,

punished for her disobedience to her father's command not to touch the

spinning wheel. In these versions, it is not only Briar Rose who

suffers, but her parents and the entire court who must sleep for a

hundred years. (One can imagine that to the class-obsessed Victorians, a

privileged daughter handling the tools of the lower classes

provoked alarm, threatening to lower the status of the family.

Briar Rose's sin can only be expiated when a man worthy enough, both in

heart and noble status, redeems her from her transgression -- restoring

both the princess and her family to its former social position.)

"What, then, became of Sleeping Beauty as she

entered the 20th century? And what does the fairy tale mean to us now, in our

post–industrial age? The modern response to the theme

has proven to be as varied as the individual artists drawn to the old

narrative. Sleeping Beauty no longer speaks to a common

identity, a single icon to shape the female image for new generations.

Instead, our Princess finds herself portrayed in many different guises:

as a helpless 1950s stay–at–home girl, a bold space opera heroine, an

oppressed time–traveling queen,

a stoic Holocaust survivor, a sexually abused child, and myriad

others. Her tale ranges in tone from unbearably bright to

psychologically dark and sinister, reflecting modern ambiguity

toward female sexual roles and women's identity."

(You can read Midori's full essay here.)

In her marvellous little book About the Sleeping Beauty, P.L. Travers (folklorist, and author of Mary Poppins) presents several different versions of the princess's story, and reflects on the symbolism of the tale:

"The idea of the sleeper," says Travers, "of somebody hidden from the mortal eye,

waiting until time shall ripen has always been dear to the folky mind; Snow White asleep in her glass coffin, Brynhild behind her wall of

fire, Charlemagne at the heart of  France, King Arthur in the Isle of

France, King Arthur in the Isle of

Avalon, Frederick Barbarossa under his mountain in Thuringia.

Muchukunda, the Hindu King, slept through eons till he was wakened by

the Lord Krishna; Oisin of Ireland dreamed in Tir n'an Og for over three

hundred years. Psyche in her magic sleep is a type of Sleeping Beauty,

Sumerian Ishtar in the underworld may be said to be another. Holga the

Dane is sleeping and waiting, and so, they say, is Sir Francis Drake.

Quetzalcoatl of Mexico and Virochocha of Peru are both sleepers. Morgan

le Fay of France and England and Dame Holle of Germany are sleeping in

raths and cairns. The theme of the sleeper is as old as the memory of

man....

"[I]f the fairy tale characters are our prototypes -- which is what

they are designed to be -- we must come to the point where we are forced

to relate the stories and their meanings to ourselves. No amount of

rationalizing will bring us to the heart of the fairy tale. To enter it

one must be prepared to let rational reason go. The stories have to be

loved for themselves before they will release their secrets. So, face

to face with the Sleeping  Beauty...we find ourselves compelled to ask:

Beauty...we find ourselves compelled to ask:

what is it in us that at certain moments suddenly falls asleep?

Who lies hidden deep within us? And who will come to wake us, what

aspect of ourselves?

"Are we dealing here with the sleeping soul and all the external affairs of life that hem it in and hide it; something that falls asleep after childhood, something that not to waken would make life meaningless? To give an answer, supposing we had it, would be breaking the law of fairy tale. And perhaps no answer is necessary. It is enough that we ponder upon and love the story and ask ourselves the question."

"We sleep," says David Abram (in Becoming Animal), "allowing gravity to hold us, allowing Earth -- our larger body --

to recalibrate our neurons, composting the keen encounters of our waking

hours (the tensions and terrors of our individual days), stirring them

back, as dreams, into the sleeping substance of our muscles. We give

ourselves over to the influence of the breathing earth. Sleep is the

shadow of the earth as it seeps into our skin and spreads throughout our

limbs, dissolving our individual will into the thousand and one selves

that compose it -- cells, tissues, and organs taking their prime

directives now from gravity and the wind -- as residual bits of sunlight,

caught in the long tangle of nerves, wander the drifting landscape of

our earth-borne bodies like deer moving across the forested valleys."

"She knew no greater

pleasure than that moment of passage into the other place, when her

limbs grew warm and heavy and the sparkling darkness behind her lids

became ordered and doors opened; when conscious thought grew owl's wings

and talons and became other than conscious." - John Crowley (Little, Big)

"We don’t sleep to sleep, dammit, any more than we eat to eat. We sleep

to dream. We’re amphibians. We live in two elements and we need both." - Lindsay Clarke (The Chymical Wedding)

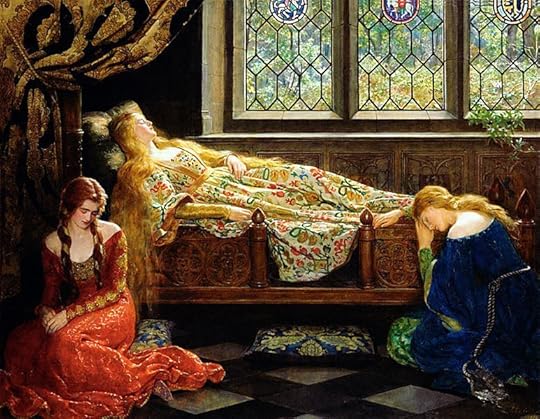

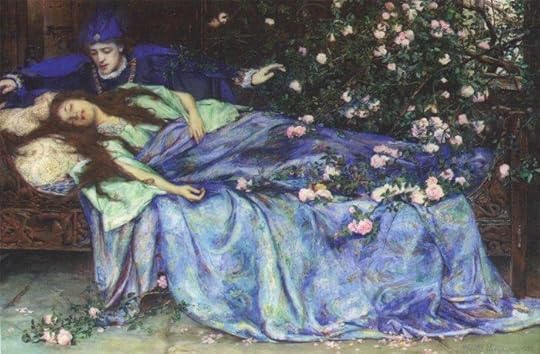

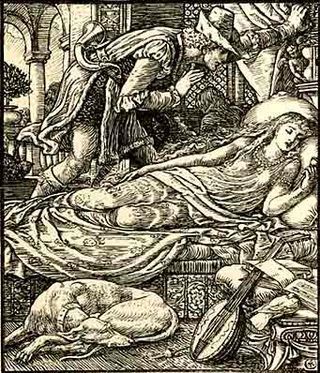

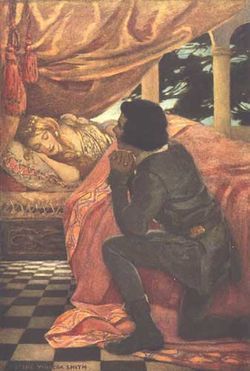

The Sleeping Beauty / Briar Rose art above is by: Arthur Wardle (English, 1860-1949), Edmund Dulac (French, 21882-1953), William Author Brakespeare (English, 1855-1914), Viktor Vasnetsov (Russian, 1848 - 1926), John Collier (English, 1850-1934), Walter Crane (English, 1845-1915), Richard Eisermann (German, 1853-1927), Edmund Dulac again, Henry Meynell Rheam (English, 1859-1920), Jessie Willcox Smith (American, 1863-1935), Margaret Evans Price (American, 1888-1973), Warwick Goble (English, 1862-1943), Ann MacBeth (Scottish, 1875-1948), and Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833-1898): studies and some of the final panels for "The Legend of Briar Rose."

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers