Terri Windling's Blog, page 179

October 5, 2013

The Dog's Tale

The Dog's Tales: a series of posts in which Tilly has her say....

The Dog's Tales: a series of posts in which Tilly has her say....

I consider it a gross dereliction of duty on the part of this blog that sometimes entire weeks go by without pictures of me. Am I not the Muse of the studio? Am I not more important than foxes and mice? Thank goodness I have my own Tumblr now. So if you want to check in on me, go to The Tilly Tumblr for a daily photo. (Except on Sundays. Even Muses have to rest.)

Don't worry, I'll still be here as well. Just as soon as these darn rodents go away....

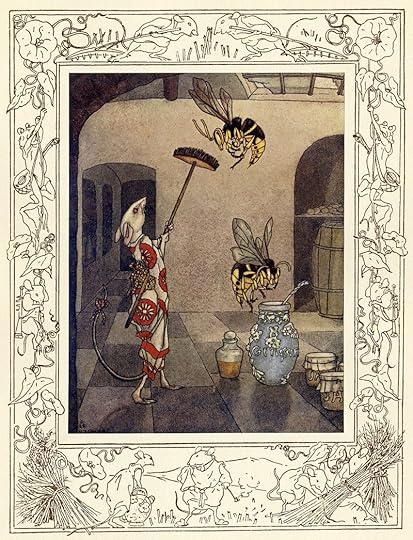

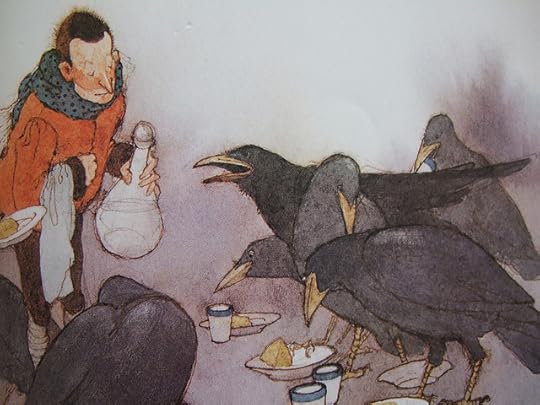

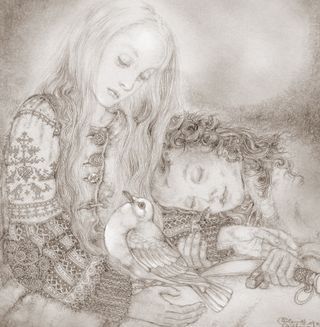

Drawing above: "Oddity" by Erik Blegvad

Drawing above: "Oddity" by Erik Blegvad

October 3, 2013

A Mischief of Mice

"The mouse ne'er shunn'd the cat as they did budge

From rascals worse than they." - William Shakespeare (Coriolanus)

“Mice are terribly chatty. They will chat about anything, and if

there is nothing to chat about, they will chat about having nothing to

chat about. Compared to mice, robins are reserved.”

- Robin McKinley (Spindle's End)

Where has he gone, my meadow mouse,

Where has he gone, my meadow mouse,

My thumb of a child that nuzzled in my palm? --

To run under the hawk's wing,

Under the eye of the great owl watching from the elm-tree,

To live by courtesy of the shrike, the snake, the tom-cat.

- Theodore Roethke (from "The Meadow Mouse")

Washed in the River

Of course the woman with the mouse-child was famous,

Of course the woman with the mouse-child was famous,

as grace is famous

a rarity

at the end of suffering. She kept him in

a nest in the dry bathtub

and washed in the river.

And though only children were meant

to believe this, I still believe this.

The fate of the body

is to confound

itself with everything. That's why in another tale, the fair sister

in another tale, the fair sister

opened her mouth and spoke

rubies

and the plain sister, vipers and toads.

Meanwhile the mother

of the gray thing

bathed him in a teacup.

Plucked him out and let him

run along the shore

to the window. Where both of them

were struck with longing —

he behind the great glass,

she behind the gray boy.

The second you see yourself in the suffering

the story's over.

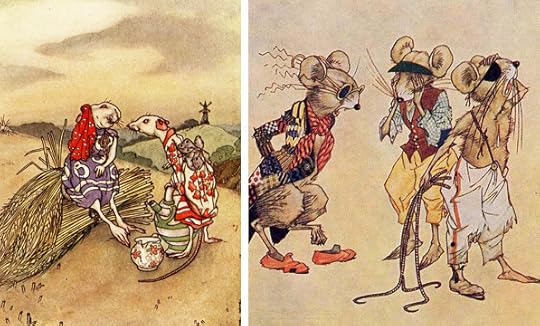

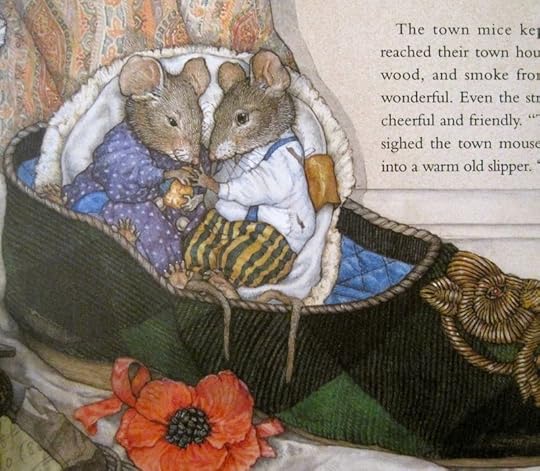

The art above: Five illustrations by Beatrix Potter (from The Tailor of Gloucester and Two Bad Mice); "The Cat and the Mouse" by Johnny B. Gruelle; "Belling the Cat" and "Thumbelina" by Milo Winter -- the latter picture paired with "CIty Mouse, Country Mouse" by Charles Folkard; an illustration from the Brambly Hedge series by Jill Barklem; a decoration and two full-page illustrations from "The Robber Bridgegroom" (a Grimms fairy tale delightfully but inexplicably illustrated with pictures of mice and frogs in Japanese clothing) by H.S. Owen, published in 1922; a detail from a "Robber Bridegroom" painting by H.S. Owen paired with "Three Blind Mice" by Charles Folkard; "Three Blind Mice" by Walton Corbould; fairy tale mice by Igor Oleinikov; two illustrations from "Town Mouse Country Mouse" by Jan Brett; "Mousekin" by Edna Miller; a full painting and a small sketch/study for "Thumbelina" by Lisbeth Zwerger; a drawing of E.B. White's "Stuart Little" by Garth Williams; a mouse drawing by H.S. Owen; a painting of mine called "The Mouse Child," and an image from the animated film "The Tale of Desperaux," based on the charming book by Kate DiCamillo. Below is another Brambly Hedge illustration by Jill Barklem.

For a delightful response to Robert Burns' poem "To a Mouse," see "From a Mouse," by the contemporary Scottish poet Liz Lochhead.

October 2, 2013

A Skulk of Foxes

The vixen who trotted through yesterday's post came to us in a mischievous Trickster guise: both clever and foolish, creative and destructive, perfectly civilized and utterly wild. Trickster foxes appear in old stories gathered from countries and cultures all over the world -- including Aesop's Fables from ancient Greece, the "Reynard" stories of medieval Europe, the "Giovannuzza" tales of Italy, the "Brer Fox" lore of the American South, and stories from diverse Native American traditions.

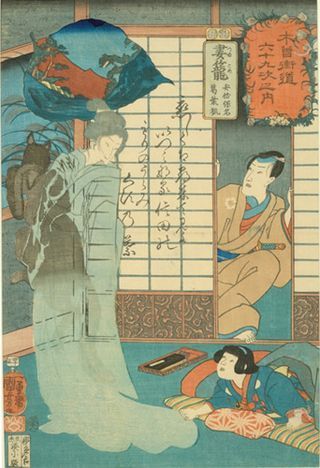

At the darker end of the fox-lore spectrum, however, we find creatures of a distinctly more dangerous cast: Reynardine, Mr. Fox, kitsune (the Japanese fox wife), kumiho (the Korean nine-tailed fox), and other treacherous shape-shifters.

Fox women can be found in many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkle (in a good article on the subject) are seductive

Fox women can be found in many story traditions but they're particularly prevalent across the Far East. Fox wives, writes folklorist Heinz Insu Fenkle (in a good article on the subject) are seductive

creatures who "entice unwary scholars and travelers with the lure of

their sexuality and the illusion of their beauty and riches. They drain

the men of their yang -- their masculine force -- and leave them

dissipated or dead (much in the same way La Belle Dame Sans Merci in

Keats's poem leaves her parade of hapless male victims).

"Korean fox lore, which comes from China (from sources probably

originating in India and overlapping with Sumerian lamia lore) is

actually quite simple compared to the complex body of fox culture that

evolved in Japan. The Japanese fox, or kitsune, probably due to its resonance with the indigenous Shinto religion, is remarkably sophisticated. Whereas the arcane aspects of fox lore  are only known to specialists in other East Asian countries, the Japanese kitsune lore is more commonly accessible. Tabloid media in Tokyo recently identified the negative influence of kitsune

are only known to specialists in other East Asian countries, the Japanese kitsune lore is more commonly accessible. Tabloid media in Tokyo recently identified the negative influence of kitsune

possession among members of the Aum Shinregyo (the cult responsible for

the sarin attacks in the Tokyo subway). Popular media often report

stories of young women possessed by demonic kitsune, and once in a while, in the more rural areas, one will run across positive reports of the kitsune associated with the rice god, Inari."

There are tales of fox wives in the West as well, but fewer of them; and they tend, by and large, to be gentler creatures. (To marry them is unlucky nonetheless, for they're skittish, shy, and not easily tamed.) An exception to this general rule can be found in the räven stories of Scandinavia. The fox-women who roam the forests of northern Europe are portrayed as heart-stoppingly beautiful, fiercely independent, and extremely dangerous.

In a musical composition inspired by these legends, the Swedish/Finnish band Hedningarna sings:

In a musical composition inspired by these legends, the Swedish/Finnish band Hedningarna sings:

Fire and frost are in your eyes

are you a woman or a fox?

Wild and sly you hunt in time of darkness

long sleeves hide your claws

with your prey you play

your mouth is red with blood.

The "nine-tailed fox" of China and Japan is often (but not always) a demonic spirit, malevolent in intent. It takes possession of human bodies, both male and female, moving for one victim to another over thousands of years, seducing other men and women in order to dine on their hearts and livers. Human organs are also a delicacy for the nine-tailed fox, or kumiho, of Korean lore -- although the earliest texts don't present the kumiho as evil so much as amoral and unpredictable...occasionally even benevolent...much like the faeries of English folklore.

In the West, it's the fox-men we need to beware of -- such as Reynardine in the old folk ballad, a handsome were-fox who lures young maidens to a bloody death. Below, the ballad is performed by Jon Boden and The Remnant Kings at the Cecil Sharp House in London:

Mr. Fox, in the English fairy tale of that name, is cousin to the kumiho and Reynardine, with a bit of Bluebeard mixed in for good measure, promising marriage to a gentlewoman while his lair is littered with her predecessors' bones. Neil Gaiman drew inspiration from the tale when he wrote his wry, wicked poem "The White Road":

There was something sly about his smile,

There was something sly about his smile,his eyes so black and sharp, his rufous hair. Something

that sent her early to their trysting place,

beneath the oak, beside the thornbush,

something that made her climb the tree and wait.

Climb a tree, and in her condition.

Her love arrived at dusk, skulking by owl-light,

carrying a bag,

from which he took a mattock, shovel, knife.

He worked with a will, beside the thornbush,

beneath the oaken tree,

he whistled gently, and he sang, as he dug her grave,

that old song...

shall I sing it for you, now, good folk?

Jeannine Hall Gailey, by contrast, casts a sympathetic eye on fox shape-shifters, writing plaintively from a kitsune's point of view in "The Fox-Wife's Invitation":

These ears aren't to be trusted.

These ears aren't to be trusted.

The keening in the night, didn't you hear?

Once I believed all the stories didn’t have endings,

but I realized the endings were invented, like zero,

had yet to be imagined.

The months come around again,

and we are in the same place;

full moons, cherries in bloom,

the same deer, the same frogs,

the same helpless scratching at the dirt.

You leave poems I can’t read

behind on the sheets,

I try to teach you songs made of twigs and frost.

you may be imprisoned in an underwater palace;

I'll come riding to the rescue in disguise.

Leave the magic tricks to me and to the teakettle.

I've inhaled the spells of willow trees,

spat them out as blankets of white crane feathers.

Sleep easy, from behind the closet door

I'll invent our fortunes, spin them from my own skin.

Although chancy to encounter in myth, and too wild to domesticate easily (in stories and in life), some of us long for foxes nonetheless, for their musky scent, their hot breath, their sharp-toothed magic. "I needed fox," wrote Adrienne Rich:

Badly I needed

a vixen for the long time none had come near me

I needed recognition from a

triangulated face burnt-yellow eyes

fronting the long body the fierce and sacrificial tail

I needed history of fox briars of legend it was said she had run through

I was in want of fox

And the truth of briars she had to have run through

I craved to feel on her pelt if my hands could even slide

past or her body slide between them sharp truth distressing surfaces of fur

lacerated skin calling legend to account

a vixen's courage in vixen terms

a vixen's courage in vixen terms

Ah, but Fox is right here, right beside us, Jack Roberts answers, a little warily:

Not the five tiny black birds that flew

out from behind the mirror

over the washstand,

nor the raccoon that crept

out of the hamper,

nor even the opossum that hung

from the ceiling fan

troubled me half so much as

the fox in the bathtub.

There's a wildness in our lives.

We need not look for it.

There are a number of good books that draw upon fox legends -- foremost among them, Kij Johnson's exquisite novel The Fox Woman. I also recommend Neil Gaiman's The Dream Hunters (with the Japanese artist Yoshitaka Amano); Larissa Lai's unusual novel, When Fox Is a Thousand; Helen Oyeyemi's recent novel, Mr. Fox; and Ellen Steiber's gorgeous urban fantasy novel, A Rumor of Gems, as well as her heart-breaking novella "The Fox Wife" (published in Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears). For younger readers, try the "Legend of Little Fur" series by Isobelle Carmody. You can also support a fine mythic writer by subscribing to Sylvia Linsteadt's The Gray Fox Epistles: Wild Tales By Mail (more information here). Many other good fox tales are listed here.

For the fox in myth, legend, and lore, try: Fox by Martin Wallen; Reynard the Fox, edited by Kenneth Varty; Kitsune: Japan's Fox of Mystery, Romance, and Humour by Kiyoshi Nozaki;Alien

Kind: Foxes and Late Imperial Chinese Narrative by Raina Huntington; The

Discourse on Foxes and Ghosts: Ji Yun and Eighteenth-Century Literati

Storytelling by Leo Tak-hung Chan; and The

Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary

Japanese Inari Worship, by Karen Smythers.

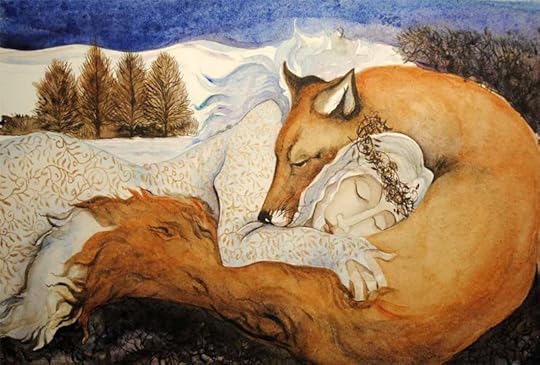

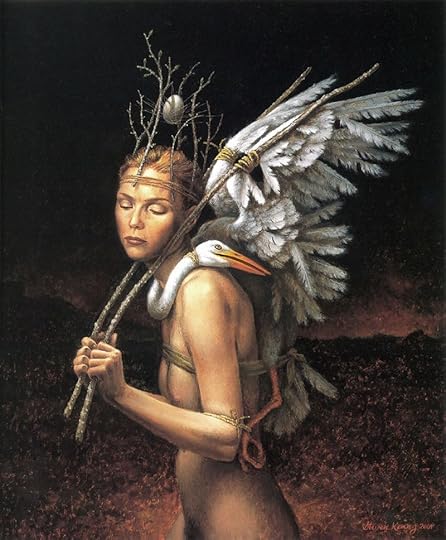

The foxy art above is: "Fox Maiden" by Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997); "Foxgloves" by Kelly Louise Judd; "Foxes" by Erica Il Cane; "Yasune Watching His Wife Change into a Fox-spirit" and "Fox Mother and Child: by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

(1797-1861); a fox drawing by Julie Morstad; "Fox" by Jackie Morris; "Fox in the Reeds by Ohara Koson (1877-1945); "Girl and Fox" by Xiaoqing Ding; two paintings of mine: "The Fox-wife of Rushford Wood" and "Fox Spirit"; "The Princess Saves the White Fox" by H.J. Ford; and two charming paintings by

Julianna Swaney:

"Night Migrations" and "Reading Together."

The foxy art above is: "Fox Maiden" by Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997); "Foxgloves" by Kelly Louise Judd; "Foxes" by Erica Il Cane; "Yasune Watching His Wife Change into a Fox-spirit" and "Fox Mother and Child: by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

(1797-1861); a fox drawing by Julie Morstad; "Fox" by Jackie Morris; "Fox in the Reeds by Ohara Koson (1877-1945); "Girl and Fox" by Xiaoqing Ding; two paintings of mine: "The Fox-wife of Rushford Wood" and "Fox Spirit"; "The Princess Saves the White Fox" by H.J. Ford; and two charming paintings by

Julianna Swaney:

"Night Migrations" and "Reading Together."

October 1, 2013

Sisters Fox and Coyote

Well, it's certainly no secret on this blog that my Sacred Trinity of

favorite living poets consists of Lisel

Mueller, Mary Oliver, and our own Jane Yolen. When any of them have a

new book on the shelves, it's cause for celebration -- and doubly so in

the case of Jane's luminous new collection, Sister Fox’s Field Guide to the Writing Life, for a number of the poems made their first appearance here, in response to posts on Myth & Moor.

Drawing on myth, folklore, fairy tales, and the everyday enchantments of the natural

world, Sister Fox (a most  beguiling little Trickster) presents poems dedicated to the daily vocation of writing: the rigours and the pleasures, the sweat and the magic, the practical craft and the numinous art.

beguiling little Trickster) presents poems dedicated to the daily vocation of writing: the rigours and the pleasures, the sweat and the magic, the practical craft and the numinous art.

A storyteller, Jane says,

unpacks his bag of tales

with fingers quick

as a weaver’s

picking the weft threads

threading the warp.

Watch his fingers.

Watch his lips

speaking the old familiar words:

“Once there was

and there was not..."

Storytellers, poets, and Tricksters alike are liars whose lies speak truths. "We reveal in stories, " she writes, "even as we revel in them, stripping off skin, muscle, tendons, flensing down to the bone."

All arts have their mystical elements, their Muses and moments of inspiration flashing like thunderbolts thrown by the gods, but these poems do not shy away from the mundane, earth-bound aspects of the writing life, or the labor that it entails.

At the start of her poem "Switching on the Light," Jane quotes scientist and inventor Thomas Alva Eddison. "Opportunity is missed by most people," he said, "because it arrives in overalls and looks like work.” Jane responds:

Just so my Muse arrives, sleeves rolled up,

apron tied in front, garden gloves hiding

broken, dirt-encrusted nails.

She hands me a hammer, a spirit level, a saw,

says: Get to work, slug-a-bed, don’t be a sloven!

her language as archaic as her ethic.

Although this is a book that will speak most of all to fellow writers (especially here in the Mythic Arts field), it also has much to offer to creative artists in general....and isn't that all of us? We all create in one way or another: not only in forms traditionally labelled as art, but also in crafting our homes, our gardens, our meals, our families, our work, our communities, and in sculpting the very shape of our lives. In this book, Sister Fox gathers poems that address the daily-yet-timeless process of making, and how that effects our lives and our world. Her bright bushy tail wrapped snugly around her, she sits and she quietly ponders these poems:

She thinks about their habitats, their markings,

the chunnering and chatter of their songs.

They are the birdlife of the writer’s world.

She likes the feel of them, the scent.

She licks her lips.

Sister Fox's Field Guide to the Writing Life by Jane Yolen (with decorations by Laura Anderson) will be published this autumn by Unsettling Wonders (John Patrick Pazdziora, editor) in conjunction with Papaveria Press (Erzebet Carr, editor). The publication date is October 31, and the book can pre-ordered here.

In the world of Tricksters, Coyote is the big, bad, bold-as-brass cousin of Sister Fox. The following poem from Jane's new book is reprint here with the kind permission of Jane and her publisher.

Trickster

by Jane Yolen

I didn’t see you trotting sideways,

Coyote, thicket-born shape-shifter,

ears pointing toward the wind.

Where were you when the story turned,

faltered, placed a stake in its own heart?

When need was so great, I wept

When need was so great, I wept

over the keyboard, mistaking

your bold footprints, that wild track,

for something much tamer.

Help me find the trail again,

out here in the wold where stories start,

where crag and sinkhole

speak a language we all knew once;

and stories poured forth,

gushing like a freshet in the spring.

The art above is: "Woman and Fox" by the surrealist photographer Katerina Plotnikova (Russia); one of Laura Anderson's Sister Fox decorations; "Hare and Fox" by Jackie Morris (Wales); a Little Elvie illustration by Catherine Hyde (Cornwall); "Fox Confessor" by Julie Morstad (Vancouver, B.C.); an unattributed coyote photograph; a Medicine Road illustration by Charles Vess (Virginia); a detail from my "Coyote Woman" (painted in the Arizona desert); and another unattributed coyote photograph.

September 30, 2013

Fox Dreams

I'm out of the studio today due to simple exhaustion. I'll be back tomorrow.

In the meantime, there's this....

The art above is "Winter Queen and Fox Lover" by Jackie Morris.

Speaking of Jackie, did you all see her expanded post on writers' notebooks?

September 29, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

We're in Spain today, with three groups who interpret Ibérica's oldest musical traditions in wonderful ways...

Above, "María Ramo de Palma" and "La Zorra" by Coetus, from Barcelona, filmed last year for the Concert Privats series. This Spanish percussion orchestra specializes in instruments that are "little or not known at all, which over time

have been used to accompany songs, ballads, processions, festivals and

dances in the Iberian Peninsula (tambourines, rods,

jars, mortars, pans, drums, kettledrums, rustic drums, etc.), creating a

proprietary and innovative language inspired by traditional rhythms and

dialogues with the voice."

Below, "La cantiga del fuego," a Sephardic song performed by Ana Alcaide and her band in Huesca (in the north-east of the country). Alcaide is a musican, composer, and music historian from Madrid, now based in Toledo. FolkWorld describes her work as "a fusion between the Nordic sonorities of the nyckelharpa (Swedish keyed

fiddle), the Sephardic (Spanish-Jewish) music, and the traditional

sounds from several places around the Mediterranean Sea." For more information, there's a good interview with Alcaide here.

And third, on a somewhat different note:

"Nueva vida" by Ojos de Brujo, from Barcelona, whose thoroughly addictive music combines flamenco and gyspy jazz with hiphop. The last time they appeared on this blog was back in 2010, and that's way too long.

September 27, 2013

Ondine

by Mary Barnard

At supper time an ondin...

Ondine

by Mary Barnard

At supper time an ondine’s narrow feet

made dark tracks on the hearth.

Like the heart of a yellow fruit was the fire’s heat,

but they rubbed together quite blue with the cold.

The sandy hem of her skirt dripped on the floor.

She sat there with a silvered cedar knot

for a low stool; and I sat opposite,

my lips and eyelids hot

in the heat of the fire. Piling on dry bark,

seeing that no steam went up from her dark dress,

I felt uneasiness

as though firm sand had shifted under my feet

in the wash of a wave.

I brought her soup from the stove and she would not eat,

but sat there crying her cold tears,

her blue lips quivering with cold and grief.

She blamed me for a thief,

saying that I had burned a piece of wood

the tide washed up. And I said, No,

the tide had washed it out again; and even so,

a piece of sodden wood was not so rare

as polished agate stones or ambergris.

She stood and wrung her hair

so that the water made a sudden splash

on the round rug by the door. I saw her go

across the little footbridge to the beach.

After, I threw the knot on the hot coals.

It fell apart and burned with a white flash,

a crackling roar in the chimney and dark smoke.

I beat it out with a poker

in the soft ash.

Now I am frightened on the shore at night,

and all the phosphorescent swells that rise

and all the phosphorescent swells that risecome towards me with the threat of her dark eyes

with a cold firelight in them;

and crooked driftwood writhes

in dry sand when I pass.

Should she return and bring her sisters with her,

the withdrawing tide

would leave a long pool in my bed.

There would be nothing more of me this side

the melting foamline of the latest wave.

The images above: two paintings for "Undine" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), and two drawings by Alan Lee. Barnard's poem, based on ondine/undine folklore, comes from the 1935 issue Poetry magazine; all rights reserved by the Barnard estate.

September 26, 2013

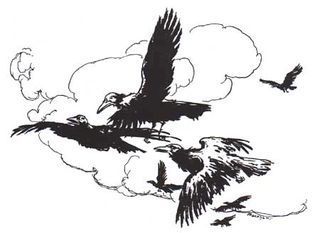

Into the Woods, 30: When Stories Take Flight

Birds have been creatures of the mythic imagination since the very earliest times. Various birds, from eagles to starlings, serve as messengers to the gods in stories the world over, carrying

blessings to humankind and prayers up to the heavens. They lead shamans into the Spirit World and dead souls to the Realm Beyond; they follow heroes

on quests, uncover secrets, give warning and shrewd council.

The movements,

cries and migratory patterns of birds have been studied as oracles. In Celtic

lands, ravens were domesticated as divinatory birds, although eagles, geese

and the humble wren also had their prophetic  powers. In Norse myth, the two ravens

powers. In Norse myth, the two ravens

of Odin flew throughout the world each dawn, then perched on the raven-god's

shoulder to whisper news into his ears. A dove with the power of human speech

sat in the branches of the sacred oak grove at Zeus's oracle at Dodona;

a woodpecker was the oracular bird in groves sacred to Mars.

According to various Siberian tribes, the

eagle was the very first shaman, sent to humankind by the gods to heal sickness

and suffering. Frustrated that human beings could not understand its speech

or ways, the bird mated with a human woman, and she soon gave birth to a

child from whom all shamans are now descended. In a mystic cloak of bird

feathers, the shaman chants, drums and prays him- or herself into a trance.

The soul takes flight, soaring into the spirit world beyond our everyday

perception. (Great care must be taken in this exercise, lest the wing-borne

soul forgets its way back home.)

Likewise, the shamans of Finland call upon

their eagle ancestors to lead them into the spirit realms and bring them

safely back again. Shamans, like eagles, are blessed (or cursed) with the

ability to cross between the human world and the realm of the gods, the

lands of the living and the lands of the dead. Despite the healing powers

this gives them (the "medicine" of their bird ancestry), men and women in

shamanic roles were often seen as frightening figures, half-mad by any ordinary

measure, poised between co-existent worlds, fully present in none. The Buriats

of Siberia traced their lineage back to an eagle and a swan, honoring the

ancestral swan-mother with migration ceremonies each autumn and spring.

To harm a swan, or even mishandle swan feathers, could cause illness or

death; likewise, to harm a woman could bring the wrath of the swans upon

men.

A swan-maiden was the mother of Cuchulain, hero of Ireland's Ulster

cycle, and thus the warrior had a geas (taboo) against killing these sacred

birds. In "The Children of Lir," one of the Three

Great Sorrows of Irish mythology, the four children of the lord of the sea

are transformed into wild  swans by the magic of a jealous step-mother. Neither

swans by the magic of a jealous step-mother. Neither

Lir himself nor all the great magicians of the Tuatha De Danann can mitigate

the power of the curse, and the four are condemned to spend three hundred

years on Lake Derryvaragh, three hundred years on the Mull of Cantyre, and

a final three hundred years off the stormy coast of Mayo. During this time,

the Children of Lir retain the use of human speech, and the swans are famed

throughout the land for the beauty of their song. The curse is ended when

a princess of the South is wed to Lairgren, king of Connacht in the North.

The swan-shapes fall away at last, but now they resume their human shapes

as four withered and ancient souls. They soon die, and are buried together

in a single grave by the edge of the sea. For many centuries, Irishmen would

not harm a swan because of this sad story -- and country folk still say

that a dying swan sings a song of eerie beauty, recalling the music of the

Children of Lir...and echoing the ancient Greek belief that a swan sings

sweetly once in a lifetime (ie: a "swan song"), in the moments before it

dies. (More swan tales can be found here and here.)

The Tuatha De Danaan, the fairy race of old Ireland, were known to appear

in the shape of white birds, their necks adorned with gold and silver chains;

alternately,

they also took human shape, wearing magical  cloaks of feathers.

cloaks of feathers.

The Celtic

islands of immortality had orchards thick with birds and bees,

where beautiful

fairy women lived in houses thatched with bright bird feathers.

Crows and ravens are also birds omnipresent

in myth and folklore. The crow, commonly portrayed as a trickster or thief,

was considered an ominous portent -- and yet crows were also sacred to Apollo

in Graeco-Roman myth; to Varuna, guardian of the sacred order in Vedic myth;

and to Amaterasu Omikami, the sun-goddess of old Japan. The ancestral spirits

of the Maratha in India resided in crows; in Egypt a pair of crows symbolized

conjugal felicity. In the Aboriginal lore of Australia and the myths of

many North American tribes, Raven appears as a dual-natured Trickster and

Creator God, credited with bringing fire, light, sexuality, song, dance,

and life itself to humankind.

In Celtic lore, the raven belonged to Morrigan,

the Irish war goddess -- as well as to Bran the Blessed in the great Welsh

epic, The

Mabinogion. Tradition has it that Bran's severed head is buried

under the Tower of London. A ceremonial Raven Master still keeps watch over

the birds of the Tower; an old custom says that if Bran's birds ever leave

the Tower, the kingdom will fall.

The owl is a bird credited with more malevolence

than any other, even though its reputation for wisdom goes back to our earliest

myths. In Greece, the owl (sacred to both Athena and Demeter) was revered

as a prescient creature -- yet also feared, for its call or sudden appearance

could foretell a death. Lilith, Adam's wife before Eve (banished for her

lack of submissiveness) was associated with owls and depicted with wings

or taloned feet.

In the Middle East, evil spirits took the shape of owls

to steal children away -- while in Siberia, tamed owls were kept in the

house as protectors of children. In Africa, sorcerers in the shape of owls

caused mischief in  the night. To the Ainu of Japan, the owl was an unlucky

the night. To the Ainu of Japan, the owl was an unlucky

creature -- except for the Eagle Owl, revered as a mediator between humans

and the gods. In North America, the symbolism of the owl varied among indigenous

tribes. The Pueblo peoples considered them baleful; the Navajo believed

them to be the restless, dangerous ghosts of the dead. The Pawnee and Menominee,

on the other hand, related to them as protective spirits, and Tohono O'Odham

medicine singers used their feathers in healing ceremonies. When we turn

to Celtic traditions we find that the owl, though sacred, is an ill omen,

prophesying death, illness or the loss of a woman's honor. In the Fourth

Branch of The Mabinogion, the magician Gwydion takes revenge upon Blodeuwedd

(the girl he made out of flowers, who married and then betrayed his son)

by turning her into an owl and setting her loose into the world. (I highly

recommend two novels inspired by this fascinating myth:Owl

Service by Alan Garner and The

Island of the Mighty by Evangeline Walton.)

The crane is another bird associated with

death in the British Isles. It was one of the shapes assumed by the King

of Annwn, the Celtic underworld. To the druids, cranes were portents of

treachery, war, evil deeds and evil women...yet the bird enjoyed a better

reputation in other lands. It was sacred to Apollo -- a messenger and a

honored herald of the spring. The pure white cranes in Chinese lore inhabited

the Isles of the Blest,  representing immortality, prosperity, and happiness.

representing immortality, prosperity, and happiness.

In Japan, the crane was associated with Jorojin, a god of longevity and

luck. In the folktales of Russia, Sicily, India and other cultures the crane

was the "animal guide" who led the hero on his adventures; and tales about cranes who marry human men can be found throughout the far East.

In Celtic lore, the magpie was a bird associated

with fairy revels; with the spread of Christianity, however, this changed

to a connection with witches and devils. In Scandinavia, magpies were said

to be sorcerers flying to unholy gatherings, and yet the nesting magpie

was once considered a sign of luck in those countries. In old Norse myth,

Skadi (the daughter of a giant) was priestess of the magpie clan; the black

and white markings of the bird represented sexual union, as well as male

and female energies kept in perfect balance. In China the magpie was the

Bird of Joy, and two magpies symbolized marital bliss; in Rome, magpies

were sacred to Bacchus and a symbol of sensual pleasure. In England, the

sighting of magpies is still considered an omen in this common folk rhyme:

"One for sorrow, two for joy; three for a girl, and four for a boy. Five

for silver, six for gold, and seven for a secret that's never been told."

The wren is another "fairy bird": a portent

The wren is another "fairy bird": a portent

of fairy encounters, and sometimes a fairy in disguise. The wren was sacred

to Celtic druids, and to the Welsh poet-magician Taliesin, thus it was unlucky

to kill the wren at any time of year except during the ceremonial "Hunting

of the Wren," around the winter solstice. In this curious custom (still

practiced in some rural areas of the British Isles and France), "Wren Boys"

dress in rag-tag costumes, bang on pots, pans and drums, and walk in procession

behind a wren killed and mounted upon a pole decorated with oak leaves and

mistletoe. In some areas, Wren Boys also appear on Michaelmas, 12th Night,

or St. Stephen's Day carrying a live wren from cottage to cottage (in a

small "Wren House" decorated with ribbons), collecting tributes of coins

and mugs of beer wherever they stop. The wren is known as the king of the

birds, an honorific explained in the following story: All the birds held

a parliament and decided that whoever could fly the highest and fastest

would be crowned king. The eagle easily outdistanced the others, but the

clever wren hid under his wing until the eagle faltered -- then the wren

jumped out and flew higher.

The dove is a bird associated with the Mother

Goddesses of many traditions -- symbolizing light, healing powers, and the

transition from one state of existence to the next. The dove was sacred

to Astarte, Ishtar,  Freyja, Brighid, and Aphrodite. The bird also represented

Freyja, Brighid, and Aphrodite. The bird also represented

the external soul, separate from the life of the body -- and thus magicians

hid their souls or hearts in the shape of doves. Doves give guidance in

fairy tales, where (in contrast with their usual gentle image) they show

a marked penchant for bloody retribution. White doves light upon the tree

Cinderella has planted upon her mother's grave, transforming rags to riches

so she can go to the prince's ball. These are the birds who warn the prince

of "blood in the shoe!" when the stepsisters try to fit into the delicate

slipper by hacking off their heels and toes. The birds eventually blind

the treacherous sisters, pecking out their eyes. Murdered children

in several fairy tales reappear as snow-white doves, hovering around the

family home until vengeance  is finally served. Likewise, the white dove in the Scots Border ballad "The

is finally served. Likewise, the white dove in the Scots Border ballad "The

Famous Flower of Serving Men" is also a human soul in limbo: a knight cruelly murdered

by his mother-in-law. He flies through the forest shedding blood-red tears

and telling his story. The woman is eventually burned. (See Delia Sherman's

Through

a Brazen Mirror and Ellen Kushner's Thomas

the Rhymer for literary adaptations of this tale.)

The mysterious song of the nightingale has

also inspired several classic tales; most famously: "The Nightingale" by

Denmark's Hans Christian Andersen and the tragic story of "The Nightingale and the Rose" by England's Oscar Wilde. (I recommend Kara Dalkey's lyrical

novel The

Nightingale, based on the former.)

Geese were holy, protected birds in many ancient

societies. In Egypt, the great Nile Goose created the world by laying the

cosmic egg from which the sun was hatched. The goose was sacred to Isis,

Osiris, Horus, Hera, and Aphrodite. In India, the goose -- a solar

symbol -- drew the chariot of Vishnu; the wild  goose, a vehicle of Brahma,

goose, a vehicle of Brahma,

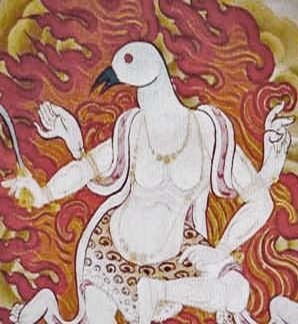

represented the creative principal, learning and eloquence. In Tibet, gooseheaded women can be found among the dakini, which are volatile female spirits that aid or hinder one's spiritual journey. In Siberia,

the goddess Toman shook feathers from her sleeve each spring. They turned

into geese, carefully tended and observed by Siberian shamans. Freyja, the

goddess of northern Europe who travels the land in a chariot drawn by cats,

is sometimes pictured with only one human foot and one foot of a goose or

swan -- an image with shamanic significance in various traditions. Berchta,

the fierce German goddess (or witch) associated with the Wild Hunt, is also

pictured with a single goose foot as she rides upon the backs of storms.

Caesar tells us that geese were sacred in Britain, and thus taboo as food

-- a custom still existent in certain Gaelic areas today. Goose-girls, talking

geese, and the goose who lays golden eggs are all standard ingredients in

the folk tales ("Mother Goose" tales) of Europe. The phrase "silly as a

goose" is recent; Ovid called them "wiser than the dog."

The stork is another Goddess

bird -- sacred to Hera and nursing mothers, which may be why it appears

in folklore carrying newborn babies to earth. The pelican is symbolic of

women's faith, sacrifice, and maternal devotion -- due to the belief that

it feeds its young on the blood of its own breast. Kites and gulls are the

souls of dead fisherman returned to haunt the shores -- a tradition limited

to the men of the sea, not their daughters or wives. "The women don't come

back no more," explained one old English fisherman to folklorist Edward

Armstrong. "They've seen trouble enough." The lark, the linnet, the robin,

the loon...they, too, have engendered tales of their own, winging their way

between heaven and earth in sacred stories, folktales, fairy tales, old rhymes and folkways from around the globe.

The following prayer comes from the Highlands of Scotland, recorded (in Gaelic) more than one hundred years ago:

Power of raven be yours,

Power of eagle be yours,

Power of the Fiann.

Power of storm be yours,

Power of moon be yours,

Power of sun.

Power of sea be yours,

Power of land be yours,

Power of heaven.

Goodness of sea

be yours,

Goodness of earth be yours,

Goodness of heaven.

Each day be

joyous to you,

No day be grievous to you,

Honor and compassion.

Love of

each face be yours,

Death on pillow be yours,

And God be with you.

“I pray to the birds," says Terry Tempest Williams (in her gorgeous book Refuge) "because they remind me of what I love rather

than what I fear. And at the end of my prayers, they teach me how to

listen.”

The art above: The lead piece is "The Wicked Witch of the Oeuf" by my friend and neighbor Ione Rucquoi. If you're not familiar with her beautiful (and often hard-hitting) work, do visit her website. After that, from top to bottom: "The Seven Ravens" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), a photograph from the "Ashes and Snow" series by Gregory Colbert, "Shadow Play" by Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997), "The Children of Lir" by John Duncan (1866-1945), "The Wild Swans" by Milo Winter (1888-1956); "The Fairies' Tiff with the Birds" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), "Hank" by Carson Ellis, "The Seven Ravens" by Lisbeth Zwerger, "Raven Girl" by Audrey Niffenegger, "Woman With Raven" by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), "Slova Sova" by Rima Staines, "Troll Witch with Owl" by Brian Froud, "Decision," "The Nightingale," and "The Crane" by Steven Kenny, "One for Sorrow" by Fred Hall (1860-1949), an old photograph of Irish Wren Boys, "Captive's Return" by Henry Ryland (1856-1924), "Aesop's Fables: The Dove and the Snake" by Heidi Holder, "Bird of Peace" by Sulamith Wulfing (1901-1989), "The Nightingale" by H.J. Ford (1860-1941), "The Goose Girl" by Rie Cramer (1887-1997), "The Heron Girl" by Danielle Barlow, a Tibetan Goosehead Dakini, "Mother Goose" by Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935), "Storks Overhead" by Józef Marian Chełmoński (1849-1914), "The Fates" by Gretchen Jacobsen, "Thumbelina" by Lisbeth Zwerger, "Guided" by Sulamith Wulfing (1901-1989), "The Great Egg" by Fidelma Massey, and another photograph from the "Ashes and Snow" series by Gregory Colbert.

For

more bird lore, I recommend: Secret Language of Birds by Adele Nozedar, The

Language of the Birds edited by David M. Guss, The Healing Wisdom of

Birds by Lesley Morrison, The Folklore of Birds by Edward A. Armstrong,

and Birds

in Legend, Fable and F

olklore by E. Ingersoll.

September 25, 2013

We are story-attentive beings

“I used to feel guilty about spending morning hours working on a book; about fleeing to the brook in the afternoon. It took several summers of being totally frazzled by September to make me realize that this was a false guilt. I'm much more use to family and friends when I'm not physically and spiritually depleted than when I spend my energies as though they were unlimited. They are not. The time at the typewriter and the time at the brook refresh me and put me into a more workable perspective.” - Madeleine L'Engle (The Summer of the Great-Grandmother)

Admit that once you have got up

from your chair and opened the door,

from your chair and opened the door,

once you have walked out into the clean air

toward that edge and taken the path up high

beyond the ordinary, you have become

the privileged and the pilgrim,

the one who will tell the story...

- David Whyte (from "Mameen")

"Do not let writing be a special event; let it be a normal part of your

day. It is normal. We are all storytellers and story-attentive beings."

- Brian Doyle's dad

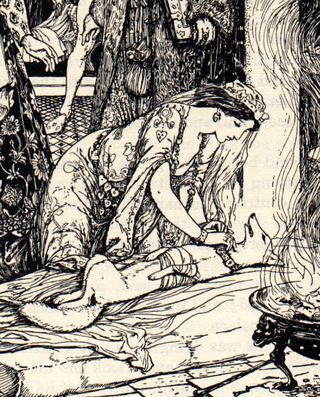

Illustration above: "Little Wildrose" by H.J. Ford (1860-1941)

Illustration above: "Little Wildrose" by H.J. Ford (1860-1941)

September 24, 2013

The capacity for astonishment

A quiet morning. The sky has cleared at last and Tilly is filled with joy. After a week of illness, she's well again and our morning walks through the hills resume.

But wait. What's this? Behind her, something is crashing and splashing through the undergrowth, moving up the stream bed in the shadow of the trees.

A friend? A foe? A monster? Tilly stands alert. Will barking be required?

Ah, but it's only a shy young calf, as surprised by us as we are by her.

Tilly throws me a glance over her shoulder, tail wagging briskly. A friend! What fun!

She trots up the stony bank eagerly...

...and then backs up fast, for the calf is not alone.

A whole herd of cows is climbing upstream, scrambling up the rocks of the waterfall like enormous mountain goats, pushed up the slope by a big black bull. He is moving them from one field to another...and we are in the way.

"Bark, bark, bark!" cries Tilly, excited. Monsters! Monsters! Run quick as you can!

I grab my book, my thermos, my jacket, and follow behind her, laughing as I run.

We run the entire length of the field, the cows and the bull bellowing behind...and flop in the grass by the field's rusty gate, hearts racing and grinning like fools. I settle back against an ancient oak, my book in hand, fresh coffee in my cup. Tilly sits close, ears cocked, alert and on guard. Just in case there are any more monsters.

She's perfectly happy. The cows and the bull had startled her, astonished her, and perhaps even frightened her a little, but it was all part of a good morning's adventure. (She'll be hoping for cows in the waterfall now when we walk this way again.)

I'd like to be more like Tilly myself, when life throws up unexpected things and bulls emerge to block the path ahead. Far better to be astonished than anxious; far better to move in new directions than stand there frozen by dismay. As Mary Oliver says in her exquisite poem titled "When Death Comes":

When it's over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms....

I want to say that I walked through life with rapt attention, like the eager, clear-eyed little creature at my side.

I'm reminded of these words from graphic designer Milton Glaser on value of astonishment:

"If you can sustain your interest in what you’re doing, you’re an

extremely fortunate person. What you see very frequently in people’s

professional lives, and perhaps in their emotional life as well, is that

they lose interest in the third act. You sort of get tired, and

indifferent, and, sometimes, defensive. And you kind of lose your

capacity for astonishment -- and that’s a great loss, because the world

is a very astonishing place. What I feel fortunate about is

that I’m still astonished, that things still amaze me. And I think that

that’s the great benefit of being in the arts, where the possibility for

learning never disappears, where you basically have to admit you never

fully learn it."

The lesson for today: Be astonished.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers