Terri Windling's Blog, page 182

August 23, 2013

Moving Day approaches...

Not mine, don't worry, but my mother-in-law's. She's moving house, and I'll be off-line all next week while we're doing the final packing.

Not mine, don't worry, but my mother-in-law's. She's moving house, and I'll be off-line all next week while we're doing the final packing.

Myth & Moor will resume the following week (the first week of September).

In the meantime, please feel free to carry on the discussion and poetry exchanges in the Comments sections of previous posts. And wish us luck!

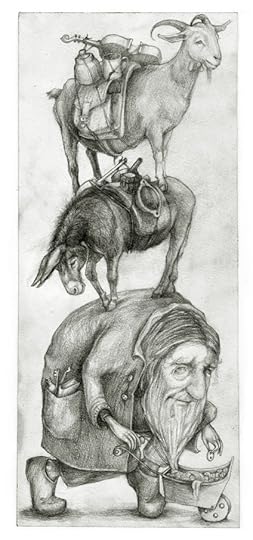

The art above, of course, is by the wonderful Rima Staines; it's called "The Goods and Chattels Man." Below, Tilly makes certain that no one packs up her dog toys by mistake...

Edited to add: The faeries in the old photograph below are my mother-in-law with her late husband and three other friends. As I've said before in relation to this picture, I've clearly married into the right family....

August 22, 2013

Into the Wood, 25: Swan Maidens and Crane Wives

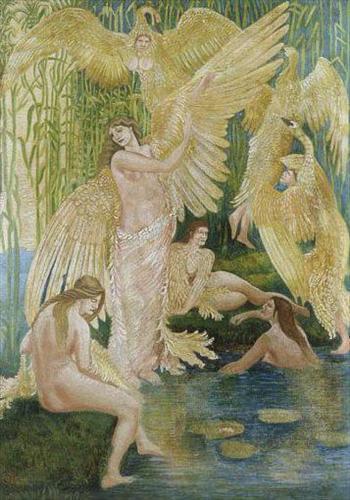

From "The Swan Maiden's Feathered Robe" by Midori Snyder:

"It is hard to imagine a more visually beautiful

image in folk tales than the one presented by the figures of the swan

maiden and her sisters. With a flurry of wings, they swoop down from the

sky to glide

elegantly across a clear pond. Then, throwing off their

feathered gowns, they bathe and frolic in the water as women. They are

always lovely, sensual, a combination of exotic sexuality and innocent

charm.

"In the traditional swan maiden narrative, a hunter or young

prince is smitten with love at first sight for the youngest swan sister —

smitten enough to commit several crimes against the very object of his

desire for the sole purpose of keeping such a magical creature within

his grasp. These crimes culminate in marriage and the attempted

domestication of the wild, fantastical swan maiden, turned into a wife

and mother. But this is less a tale about love than one about marital

coercion and confusion. Neither husband nor wife is on the same page;

their union is at best a tenuous détente, made possible only by the

husband's theft of the swan maiden's feathered gown, forcing her to

remain human and estranged from her own world. The husband has done

nothing to earn such a  powerful wife, and the swan maiden has no

powerful wife, and the swan maiden has no

opportunity to choose her own fate. This is a marriage that cannot last

in its fractured form. It must either go forward to find a level playing

field for husband and wife, or it must end in miserable dissolution.

"Let us consider a European version of the tale reconstructed from

a variety of sources by Victorian author Joseph Jacobs. A hunter is

spending the night in a clump of bushes on the edge of a pond, hoping to

capture wild ducks. At midnight, hearing the whirring of wings, he is

astonished to see not ducks but seven maidens clad in robes of feathers

alight on the bank, disrobe, and begin to bathe and sport in the water.

The hunter seizes the opportunity to creep through the bushes and steal

one of the robes. When dawn approaches, the sisters gather their

garments and prepare to leave, but the youngest sister is distraught,

unable to find her robe.

Daylight is coming and the older sisters cannot wait for her. They

leave her behind, telling her 'to meet your fate whatever it may be.'

"As soon as the sisters are out of sight, the hunter approaches

her, holding the feathered robe. The young maiden weeps and begs for its

return, but the hunter, already too much in love, refuses. Instead, he

covers her with his cloak and  takes her home. Once there, he hides her

takes her home. Once there, he hides her

robe, knowing that if she puts it on again, he will lose her. They are

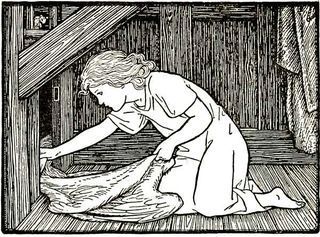

married, and she gifts him with two children, a boy and a girl. One day, while playing hide–and–seek, the little girl finds the

hidden robe and brings it to her mother. Without a moment's hesitation,

the wife slips on the robe. We can almost imagine the mother's sigh of

relief to be herself again, her true fantastic self, and not the pale

wife weighted down by domestic drudgery. And yet, she offers a spark of

hope for the future of the marriage. 'Tell your father, if he wishes to

see me again,

he must find me in the land East o' the Sun and West' o' the Moon,'

she says to her daughter just before flying out the window.

"No matter how compliant a swan maiden may appear as a wife, there

"No matter how compliant a swan maiden may appear as a wife, there

remains an unspoken anxiety and tension beneath the surface of her

marriage. Her husband can never be certain of her affection, for it has been held hostage by her stolen skin. He offers her his cloak, but it is

an exchange of unequal goods. Her feathered robe is the sign of her

wild nature, of her freedom, and of her power, while his cloak becomes

the instrument of her domestication, of her submission in human society.

He steals her identity, the very thing that attracted him, and then

turns her into his most precious prize,

a pale version of the original creature of magic.

"Conflict is never far beneath the veneer of the swan maiden's

compliance. In a German version of the tale, a hunter captures a swan

maiden's skin, and although she follows him home pleading for its

return, he offers her only marriage. She accepts, not out of love but to

remain close to the skin which is her identity. Fifteen years and

several children later, the hunter leaves to go on a hunting trip, for

once forgetting to lock the attic. Alone in the house, the wife searches

the attic and finds her skin in a dusty chest. She immediately puts it

on and flies out the window before the startled eyes of

her children, with nary a word of farewell....

"The swan maiden stories suggest that there are marriages that will

themselves to dissolution because of the inability of the pair to mature

and to integrate into each other's world. In the human

world, the swan

world, the swan maiden loses her fantastic nobility and is subjected to the daily labors

of a human wife – including childbearing, which is portrayed as so

distasteful the swan wives often seem to have few qualms about leaving

their children behind the moment they recover their skins.

The husband either cannot find her world (and dies of melancholy),

or, when he does succeed in arriving in her domain, he cannot accept the

fantastical world on his wife's terms. These are, at best, temporary

reunions....

"There was considerable renewed interest in the swan maiden tales

in Europe throughout the late 19th century. For the English Victorians

it was the era of the 'Married Woman's Property Acts' and of the 'New

Woman.' Marriage roles, divorce, and the appropriate role of a wife were

being re-examined and questioned. The swan maiden, with her ability to

effectively fly away from her marriage and her children, became a

fascinating study for Victorian folklorists, who saw in the narrative

the evolution of the institution of marriage. According to Carole Silver in her illuminating article 'East of the

Sun and West of the Moon': Victorians and Fairy Brides, the

interpretations of the tale varied widely, and depended on one's

attitudes toward women's role in marriage, an imbalance of power between

the sexes and women's sexuality.

"Joseph Jacobs felt that the reader's sympathy lay with the

abandoned husband, not the swan maiden as representative of a

matrilineal society with 'easy and primitive' marriage bonds that could

be more easily broken.

Silver reports that Jacobs believed 'that the "eerie wife," in

separating from her mate, forfeited the audience's respect; her behavior

reinforced the listener's sympathy with the husband. "Is he not,"

Jacobs asked, to be "regarded as the superior of the fickle, mysterious

maid that leaves him for the break of a  taboo?" ' Silver argues that

taboo?" ' Silver argues that

folklorists like Jacobs were expressing anxiety over the emerging

institution of divorce, believing that the looseness of the marriage

bond was a trait among 'savages.' Silver continues: 'Clearly, free and

easy

separation was associated with primitive societies and savage eras.

Complex and difficult divorce, on the other hand, was the hallmark of a

highly evolved society. . . .By diminishing the claims to superiority

of the fairy bride, neutralizing her sexuality, and limiting or denying

her right to divorce, Victorian folklorists rendered her acceptable to

themselves and their society.'

"Can we love the swan maiden? She seems to offer both an image of

feminine power and feminine weakness: a girl who submits to the

deceptions of a suitor and a woman who rejects the terms of an unfair

marriage. She is at once a doting mother and one who will happily

abandon her children in favor of her own needs. Her ambiguous tale can

be read as the suppression of women's rights and women's creative power

through enforced domestication, but it can also show such a woman's

resolve to not only survive a questionable marriage but to remain true

to her nature. When given the chance,

no amount of suppression can keep the swan maiden down. I feel a

terrible tenderness for the youngest swan–girl, abandoned by her sisters

to her fate on the ground. I want to shelter her from the routine

ordinariness of her human marriage, given over to the demands of others.

And I want to cheer, relieved and inspired, when she finds her own true

self again, and rises to soar."

(Read Midori's full article here.)

When the change came

When the change came

she was floating in the millpond,

foam like white lace tracing her wake.

First her neck shrinking,

candle to candleholder,

the color of old, used wax.

Wings collapsed like fans;

one feather left,

floating memory on the churning water.

Powerful legs devolving;

Powerful beak dissolving.

She would have cried for the pain of it

had not remembrance of sky sustained her....

- Jane Yolen (from "Swan/Princess")

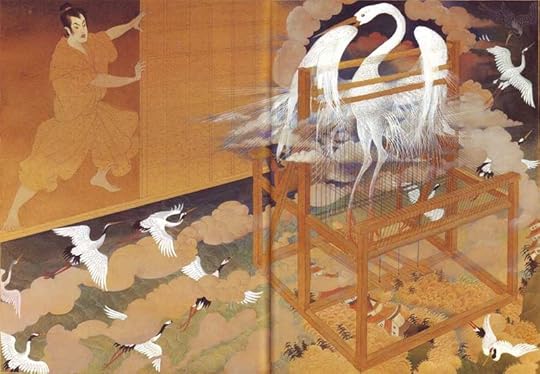

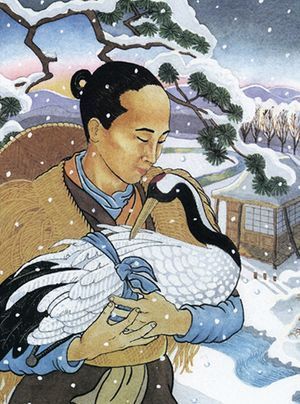

"The Crane Wife," from Asia, is a closely related tale in the animal bride

tradition. Details vary according to country, century, and teller, but the basic story is this: A poor weaver (or sailmaker) finds an injured crane on his doorstep (or in the fields, or by the side of a moonlit lake), dresses her

wounds, and nurses her back to health. He kindly releases the crane back into

the wild...after which a beautiful woman appears (the crane in

human form), and the two of them promptly marry.

All goes well for

a while, until the man's business falls on hard times. The crane wife

tells her husband that she can lift them out of poverty by weaving a

bolt of wondrous cloth (or an extraordinary sail) --

but he must solemnly promise not to watch her as she does it. She

weaves the cloth, they sell it for a tremendous price, and soon the

couple is rich. But now the man grows greedy, and he pressures her to

make more and more. His wife grows tired and begins to waste away,

but the man ignores this and continues to press for more cloth.

Finally, at death's door, she tells her husband she can make only one

more bolt. That night her husband decides it's time to learn what the

secret of her weaving is. Spying on her as she works, he's horrified to

see a crane at the loom, plucking feathers from her own breast and

weaving them into the magical cloth. He cries aloud, and the crane wife

knows he's broken his promise to her. She flies away, and he spends the

rest of his life lamenting his lost love.

Jeannine Hall Gailey gives voice to the Crane Wife's sorrow and anger in her poignant poem based on the folktale:

Jeannine Hall Gailey gives voice to the Crane Wife's sorrow and anger in her poignant poem based on the folktale:

I flew away, a crane who had given you

her white glory, and you knew the cloth

to be the sacrifice of my own skin, my feather coat.

A thousand cranes descended on your hut,

crying with betrayal. You searched all of Japan for me

until you found a lake of cranes, those white ciphers,

cried your goodbyes, useless, now, with age.

You had the gift of my wings, knew the lift

of flight and the gentle neck. Now, old man,

remember, when you watch a flash in the sky,

remember me, remember

The folk tale also inspired the title poem in Sharon Hashimoto's debut poetry collection The Crane Wife, winner of the Theodore Roerich Poetry Prize -- a haunting volume that explores the author's Japanese heritage and life in the Pacific Northwest.

Patrick Ness's new adult novel, The Crane Wife, explores the folk tale's theme of love and betrayal, transplanting its setting to modern-day London. In an interview with in Polari Magazine, Ness explains why he find the old tale so compelling:

"[U]nlike most folk and fairy tales, it starts with an act of kindness.Most start with an act of cruelty, but this one starts with a kind act and then turns into [a tale about] that kind person making a mistake, and letting their worst instincts get the best of them, and that's why it appeals to me. It's a really different flavour than most tales. It ends tragically but you can understand it in human terms, that you're given a chance with the eternal, the beautiful, the magical, but you blow it. I think that's really human."

"[U]nlike most folk and fairy tales, it starts with an act of kindness.Most start with an act of cruelty, but this one starts with a kind act and then turns into [a tale about] that kind person making a mistake, and letting their worst instincts get the best of them, and that's why it appeals to me. It's a really different flavour than most tales. It ends tragically but you can understand it in human terms, that you're given a chance with the eternal, the beautiful, the magical, but you blow it. I think that's really human."

Ness was inspired not only by the story itself, but by the Crane Wife songs penned by Colin Meloy and recorded by his alt-folk band, The Decemberists.

Meloy

Meloy

first came across the Crane Wife folk tale several years ago in the

children’s section of a bookstore in Portland, Oregon. “I thought that it would

be a great thing to try to put it to some sort of song form, be it a

single tune or something longer,” Meloy says. “So I struggled with that for

years until finally I realized that it just needed more parts and set

about building those.” He ended up with a collection of songs, three of

them based on the Japanese story and the rest using other old folk

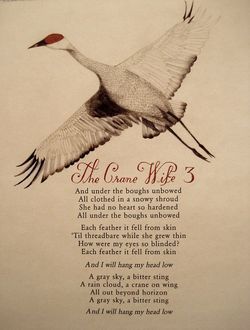

motifs: death, war, greed, and murder. (The full lyrics to Crane Wife 1 & 2 are here, to Crane Wife 3 here, and Meloy discusses his songs on National Public Radio's "Fresh Air" program here.)

Below, Meloy sings a stripped-down, solo version of the three Crane Wife songs at the Ace Hotel in New York City (recorded in October, 2010).

"There were as many truths - overlapping, stewed together - as

there were tellers. The truth mattered less than the story's life. A

story forgotten died. A story remembered not only lived, but grew." - Patrick Ness (from The Crane Wife)

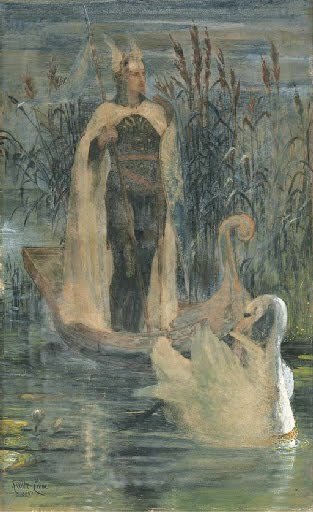

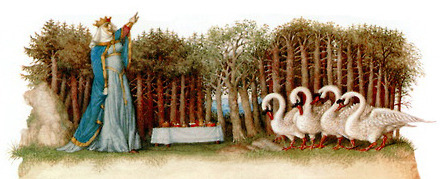

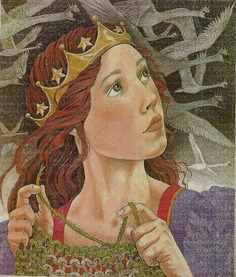

The illustrations above are: "Swans" by Gennardy Spirin (Russian); "Swan Maidens" and Lohengrin" by Walter Crane (English, 1845-915); "The Child Finds the Feather Dress," artist unknown (from Europa's Fairy Book, NYC, 1916); a swan maiden drawing of mine called "Wings" (inspired by a Kim Antieau poem); "Wild Swans" by John Bauer (Swedish, 1882-1918); "On the Shores of the Land of Death" by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (Finnish, 1865-1931) ); "Swans" by Jeanie Tomanek (American); "Six Swans" by Warwick Goble (English, 1862-1943); "The Crane Wife" by Diana Torledano (Spanish); three "Crane Wife" illustrations by

Gennardy Spirin (Russian); a "Crane Wife" illustration by Cheryl Kirk Noll (American); lyrics for Colin Meloy's Crane Wife 3, art by Carson Ellis; and "Swans" by

Walter Crane (English, 1845-915).

August 21, 2013

Into the Wood, 24: Swan's Wing

From The Faraway Nearby by Rebecca Solnit:

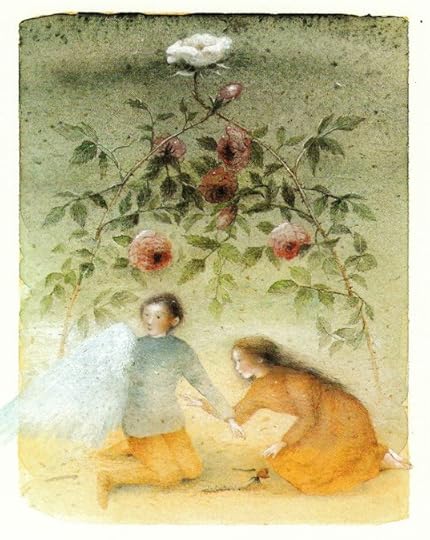

"Fairy tales are about trouble, about getting into and out of it, and trouble seems to be a necessary stage on the route to becoming. All the magic and glass mountains and pearls the size of houses and princesses beautiful as the day and talking birds and part-time serpents are distractions from the core of most of the stories, the struggle to survive against adversaries, to find your place in the world, and to come into your own.

"Fairy tales are almost always the stories of the powerless, of youngest sons, abandoned children, orphans, of humans transformed into birds and beasts or otherwise enchanted away from their own lives and selves. Even princesses are chattels to be disowned by fathers, punished by step-mothers, or claimed by princes, though they often assert themselves in between and are rarely as passive as the cartoon versions. Fairy tales are children's stories not in wh they were made for but in their focus on the early stages of life, when others have power over you and you have power over no one.

"Fairy tales are almost always the stories of the powerless, of youngest sons, abandoned children, orphans, of humans transformed into birds and beasts or otherwise enchanted away from their own lives and selves. Even princesses are chattels to be disowned by fathers, punished by step-mothers, or claimed by princes, though they often assert themselves in between and are rarely as passive as the cartoon versions. Fairy tales are children's stories not in wh they were made for but in their focus on the early stages of life, when others have power over you and you have power over no one.

"In them, power is rarely the right tool for survival anyway. Rather the powerless thrive on alliances, often in the form of reciprocated acts of kindness -- from beehives that were not raided, birds that were not killed but set free or fed, old women who were saluted with respect. Kindness sewn among the meek is harvested in crisis...

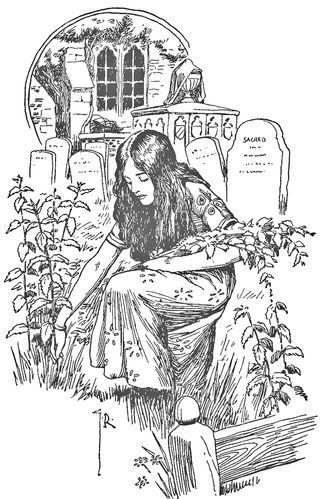

"In Hans Christian Andersen's retelling of the old Nordic tale that begins with a stepmother, "The Wild Swans," the banished sister can only disenchant her eleven brothers -- who are swans all day look but turn human at night -- by gathering stinging nettles barehanded from churchyard graves, making them into flax, spinning them and knitting eleven long-sleeved shirts while remaining silent the whole time. If she speaks, they'll remain birds forever. In her silence, she cannot protest the crimes she accused of and nearly burned as a witch.

"In Hans Christian Andersen's retelling of the old Nordic tale that begins with a stepmother, "The Wild Swans," the banished sister can only disenchant her eleven brothers -- who are swans all day look but turn human at night -- by gathering stinging nettles barehanded from churchyard graves, making them into flax, spinning them and knitting eleven long-sleeved shirts while remaining silent the whole time. If she speaks, they'll remain birds forever. In her silence, she cannot protest the crimes she accused of and nearly burned as a witch.

"Hauled off to a pyre as she knits the last of the shirts, she is rescued by the swans, who fly in at the last moment. As they swoop down, she throws the nettle shirts over them so that they turn into men again, all but the youngest brother, whose shirt is missing a sleeve so that he's left with one arm and one wing, eternally a swan-man. Why shirts made of graveyard nettles by bleeding fingers and silence should disenchant men turned into birds by their step-mother is a question the story doesn't need to answer. It just needs to give us compelling images of exile, loneliness, affection, and metamorphosis -- and of a heroine who nearly dies of being unable to tell her own story."

From my essay "Transformations" (published in Mirror, Mirror on the Wall):

"Silence is another element we find in classic fairy tales — girls

muted by magic or sworn to silence in order to break enchantment. In

"The Wild Swans,"

a princess is imprisoned by her stepmother, rolled in filth, then

banished from home (as her older brothers had been before her). She goes

in search of her missing brothers, discovers that they've been turned

into swans, whereupon the young girl vows to find a way to break the

spell.

A mysterious woman comes to her in a dream and tells her what to

do: 'Pick the nettles that grow in graveyards, crush and spin them into

thread,

then weave them into coats and throw  them over your brothers'

them over your brothers'

backs.' The nettles burn and blister, yet she never falters: picking,

spinning, weaving, working with wounded, crippled hands, determined to

save her brothers. All this time she's silent. 'You must not speak,' the dream woman has warned, 'for a single

world will be like a knife plunged into your brothers' hearts.'

"You must not speak. That's what my stepfather said: don't speak,

don't cry, don't tell. That's what my mother said as well, as we sat in

hospital waiting rooms -- and I obeyed, as did my brothers. We sat as

still and silent as stone while my mother spun false tales to explain

each break and bruise and burn. Our family moved just often enough that

her stories were fresh and plausible; each new doctor believed her, and

chided us children to be more careful. I never contradicted those tales.

I wouldn't have dared, or wanted to. They'd send me into foster care.

They'd send my young brothers away. And so we sat, and the unspoken

truth was as sharp as the point of a knife."

Youngest Brother, swan's wing,

where one arm should be, yours the shirt

of nettles short a sleeve

and me with no time left to finish --

I didn't mend you all the way back into man

though I managed for your brothers;

they flit again from court to playing-courts

to courting, while you station yourself,

wing folded from sight, avian eye

to the outside, no rebuke meant but love's.

Was it better then, the living on the water,

the taking to air...?

- Debora Gregor (from "Ever After," published in The Poets' Grimm)

“There are ways of being abandoned even when your parents are right there.” - Louise Erdrich (from The Plague of Doves)

The illustrations for The Wild Swans above are by: Kaarina Kaila (Finnish), Gennady Spirin (Russian), Nadezhda Illarionova (Russian), Susan Jeffers (American), Gordon Robinson (English, early 20th century), Yvonne Gilbert (English), Anna and Elena Balbusso (Italian), Steven Kenney (American),

Nadezhda Illarionova (Russian), and Anton Lomaev (Belorussian).

Also, four good novels inspired by the Wild Swans fairy tale.

August 20, 2013

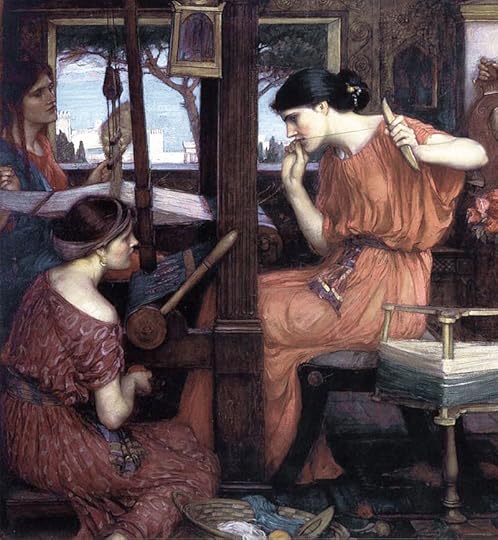

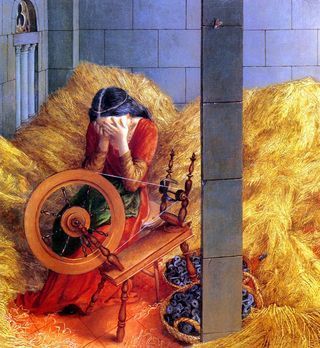

Into the Woods, 23: Spinning Straw into Gold

"A thread now most often means a line of conversation via e-mail or other electronic means, but thread must have been an even more compelling metaphor when most people witnessed or did the women's work that is spinning. It is a mesmerizing art, the spindle revolving below the strong thread that the fingers twist

out of the mass of fiber held on an arm or a distaff. The gesture turns the cloudy mass of fiber into lines with which the world can be tied together. Likewise the spinning wheel turns, cyclical time revolving to draw out the linear time of a thread. The verb to spin first meant just this act of making, then evolved to mean anything turning rapidly, and then it came to mean telling a tale.

out of the mass of fiber held on an arm or a distaff. The gesture turns the cloudy mass of fiber into lines with which the world can be tied together. Likewise the spinning wheel turns, cyclical time revolving to draw out the linear time of a thread. The verb to spin first meant just this act of making, then evolved to mean anything turning rapidly, and then it came to mean telling a tale.

"Strands a few inches long twine together into a thread of yarn that can go on forever, like words becoming stories. The fairy-tale heroines spin cobwebs, straw, nettles into whatever is necessary to survive. Scheherazade forestalls her death by telling a story that is like a thread that cannot be cut; she keeps spinning and spinning, incorporating new fragments, characters, incidents, into her unbroken, unbreakable narrative thread. Penelope at the other end of the treasury of stories prevents her wedding to any one of her suitors by unweaving at night what she weaves by day on her father-in-law's funeral garment. By spinning, weaving, and unraveling, these women master time  itself, and though master is a masculine word, this mastery is feminine.

itself, and though master is a masculine word, this mastery is feminine.

"Women were spinsters before the word became pejorative, when distaff meant the female side of the family. In Greek

mythology, each human life is a thread that the three Moirae, or Fates,

spin, measure, and cut. With Rumpelstiltskin's help, the unnamed

fairy-tale heroine spins straw into gold, but the wonder is that every

spinner takes the amorphous mass before her and makes thread appear,

from which comes the stuff that contains the world, from a fishing net

to a nightgown. She makes form out of formlessness, continuity out of

fragments, narrative and meaning out of scattered incidents, for the

storyteller is also a spinner or weaver and a story is a thread that

meanders through our lives to connect us each to each and to the purpose

and meaning that appear like roads that we must travel."

- Rebecca Solnit (The Faraway Nearby)

"Wanted: a needle swift enough to sew this poem into a blanket." - Charles Simic

"It’s no accident that spinning is associated with language, that we

may be said to 'spin' a tale or tell a 'yarn.' Spinning brings a cosmic

“'twist' into the raw materials of nature, giving them strength and

continuity. When we look at events with a higher awareness, we can

perceive the links between them and weave them into an ongoing story,

coming to an understanding of their true essence. The spinning of straw

into gold can be transformed from a mechanical search for material gain

into a quest for meaning and knowledge.

"As anyone who has tried it knows, spinning is not a mindless task. It

"As anyone who has tried it knows, spinning is not a mindless task. It

requires constant attention not to end up with a tangled mess or a

broken thread. At the same time, the rhythmical balance of manual and

mental activity, hand and mind working together to produce a continuous,

even thread, is deeply satisfying and calming. The spinner often finds

her thoughts becoming organized along with the fiber, leading to new

insights or creative inspiration. An inner 'golden thread' can be

sensed, one that we can try to cultivate ever more strongly.

"This is the thread that we can try to make of our lives, when we

accept the materials we are given; on the other hand, we reject them at

our peril. In “Sleeping Beauty,” for example, the king tries to avert

the prediction that his daughter will prick her finger on a spindle and

fall into a deathlike sleep by burning all the spinning wheels in the

kingdom. He thus brings about the very fate he seeks to escape, when the

princess’s curiosity leads her to touch the first spindle she sees.

Destiny cannot be averted through ignorance, but only transformed

through knowledge."

- Lori Widmer Hess (from "Spinning a Tale")

Each day she weaves for twelve brothers, twelve golden shirts twelve pairs of slippers, twelve sets of golden mail.

twelve pairs of slippers, twelve sets of golden mail.

She sleeps under olive trees, praying for rescue.

In her dreams doves fly in circles, crying out her name.

For a hundred years she is turned into a golden bird,

hung in a cage in a witch's castle. Her brothers

are all turned to stone. She cannot save them,

no matter how many witches she burns.

She weeps tears that cannot be heard

but turn to rubies when they hit the ground.

She lifted her hand against the light

and it became a feathered wing....

- Jeannine Hall Gailey (from "Becoming the Villainess")

Fire shadows on the wall,

A hand rises, falls, as steady as a heart beat,

Threading the strands of life.

This is the warp thread, this the woof

This the hero-line, this the fool.

Needle and scissors, scissors and pins,

Where one life ends, another begins.

- Jane Yolen (from "The Fates")

“Writing fiction is the act of weaving a series of lies to arrive at a greater truth.” - Khaled Hosseini

The spinning, weaving, and sewing art above is: "Rumplestiltskin" by Paul O. Zelinksy (American); "Sleeping Beauty" by Walter Crane (English, 1845-1915); "Sleeping Beauty" by Jennie Harbour (English, 1893-1959); a detail from "Penelope and the Suitors" by John William Waterhouse (English, 1849-1917); "Sleeping Beauty" by Nadezhda Illarionova (Russian); another illustration from "Rumplestiltskin" by Paul O. Zelinksy (American); "The Wild Swans" by Nadezhda Illarionova (Russian); "The Wild Swans" by Mercer Mayer (American) & Eleanor V. Abbott (English, 1909-1972); "The Wild Swans" by Adrienne Segur (French/Greek, 1901-18981); "The Wild Swans" by Susan Jeffers (American); "Sleeping Beauty" by John D. Batten (English, 1860-1932); "Woman Sewing" by Vilhelm Hammershøi (Danish, 1864-1916); "Woman Sewing in an Interior" by Marie-Gabriel Biessy (French, 1953-1945); "Three Muses" by Oliver Hunter (Australian); "Two Girls Sewing at the Window" and "Loom and Thread" by Carl Larsson (Swedish, 1853-1919).

Spinning Straw into Gold

"A thread now most often means a line of conversation via e-mail or other electronic means, but thread must have been an even more compelling metaphor when most people witnessed or did the women's work that is spinning. It is a mesmerizing art, the spindle revolving below the strong thread that the fingers twist

out of the mass of fiber held on an arm or a distaff. The gesture turns the cloudy mass of fiber into lines with which the world can be tied together. Likewise the spinning wheel turns, cyclical time revolving to draw out the linear time of a thread. The verb to spin first meant just this act of making, then evolved to mean anything turning rapidly, and then it came to mean telling a tale.

out of the mass of fiber held on an arm or a distaff. The gesture turns the cloudy mass of fiber into lines with which the world can be tied together. Likewise the spinning wheel turns, cyclical time revolving to draw out the linear time of a thread. The verb to spin first meant just this act of making, then evolved to mean anything turning rapidly, and then it came to mean telling a tale.

"Strands a few inches long twine together into a thread of yarn that can go on forever, like words becoming stories. The fairy-tale heroines spin cobwebs, straw, nettles into whatever is necessary to survive. Scheherazade forestalls her death by telling a story that is like a thread that cannot be cut; she keeps spinning and spinning, incorporating new fragments, characters, incidents, into her unbroken, unbreakable narrative thread. Penelope at the other end of the treasury of stories prevents her wedding to any one of her suitors by unweaving at night what she weaves by day on her father-in-law's funeral garment. By spinning, weaving, and unraveling, these women master time  itself, and though master is a masculine word, this mastery is feminine.

itself, and though master is a masculine word, this mastery is feminine.

"Women were spinsters before the word became pejorative, when distaff meant the female side of the family. In Greek

mythology, each human life is a thread that the three Moirae, or Fates,

spin, measure, and cut. With Rumpelstiltskin's help, the unnamed

fairy-tale heroine spins straw into gold, but the wonder is that every

spinner takes the amorphous mass before her and makes thread appear,

from which comes the stuff that contains the world, from a fishing net

to a nightgown. She makes form out of formlessness, continuity out of

fragments, narrative and meaning out of scattered incidents, for the

storyteller is also a spinner or weaver and a story is a thread that

meanders through our lives to connect us each to each and to the purpose

and meaning that appear like roads that we must travel."

- Rebecca Solnit (The Faraway Nearby)

"Wanted: a needle swift enough to sew this poem into a blanket." - Charles Simic

Each day she weaves for twelve brothers, twelve golden shirts twelve pairs of slippers, twelve sets of golden mail.

twelve pairs of slippers, twelve sets of golden mail.

She sleeps under olive trees, praying for rescue.

In her dreams doves fly in circles, crying out her name.

For a hundred years she is turned into a golden bird,

hung in a cage in a witch's castle. Her brothers

are all turned to stone. She cannot save them,

no matter how many witches she burns.

She weeps tears that cannot be heard

but turn to rubies when they hit the ground.

She lifted her hand against the light

and it became a feathered wing....

- Jeannine Hall Gailey (from "Becoming the Villainess")

Fire shadows on the wall,

A hand rises, falls, as steady as a heart beat,

Threading the strands of life.

This is the warp thread, this the woof

This the hero-line, this the fool.

Needle and scissors, scissors and pins,

Where one life ends, another begins.

- Jane Yolen (from "The Fates")

“Writing fiction is the act of weaving a series of lies to arrive at a greater truth.” - Khaled Hosseini

The spinning, weaving, and sewing art above is: "Rumplestiltskin" by Paul O. Zelinksy (American); "Sleeping Beauty" by Walter Crane (English, 1845-1915); "Sleeping Beauty" by Jennie Harbour (English, 1893-1959); a detail from "Penelope and the Suitors" by John William Waterhouse (English, 1849-1917); "The Wild Swans" by Nadezhda Illarionova (Russian); "The Wild Swans" by Mercer Mayer (American) & Eleanor V. Abbott (English, 1909-1972); "The Wild Swans" by Adrienne Segur (French/Greek, 1901-18981); "The Wild Swans" by Susan Jeffers (American); "Sleeping Beauty" by John D. Batten (English, 1860-1932); "Woman Sewing" by Vilhelm Hammershøi (Danish, 1864-1916); "Woman Sewing in an Interior" by Marie-Gabriel Biessy (French, 1953-1945); "Three Muses" by Oliver Hunter (Australian); "Two Girls Sewing at the Window" and "Loom and Thread" by Carl Larsson (Swedish, 1853-1919).

August 19, 2013

The path ahead

In these late summer days, the hills change once again, and the trails we travel are changing too. The bracken grows high, swallowing the paths; they are thick green jungles we push our way through...

...while the blackberry brambles clutch at my skirts and the thorns catch in Tilly's sleek fur.

Midsummer flowers now turn into late summer berries, first green, then red, than a plump, juicy black.

Tilly grazes, excited, and then disappointed; her beloved berries are not ripe and ready yet. But soon every walk will yield its wild harvest, its

sweetness, for the pup and me both. The hill will turn into her larder and she will feast on berries wherever we go, lipping them up

from the brambles, her chin covered with tiny thorn scratches and sticky with

juice.

I find a few wild rasberries, but the pup rejects this offerings. It's

blackberries she dreams of, blackberries she craves. Nevermind. There

are only a few here, and I am quite happy to eat them myself.

The pathway mirrors my life and my art right now: lush, green, and fertile, but thorny too. There's beauty, but also brambles to push through; there's sweetness ahead, but it's not ripened yet.

I just keep on walking, my good dog beside me, trusting the land, trusting my heart, trusting my feet to find the way.

An urgent appeal from Tilly and me...

Pebbles needs our help! Please follow this link, and Erzebet YellowBoy Carr (author, artist, and publisher of Papaveria Press) will explain. And once you'e read Erzebet's post, please help by boosting the signal and/or donating whatever you can.

Okay, mythic arts community, let's step up to the plate and bring Pebbles home...and also help others who are suffering beside her.

August 18, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Three beautiful songs to start off a beautiful summer week, all recorded for the The Mahogony Sessions here in the UK:

First (above), "Facing West," by The Staves, three sisters from Watford, Hertfordshire -- all of them songwriters and incredible musicians. This was recorded just ten days ago at the Secret Garden Party, a music and arts festival in Cambridgeshire.

Second (below), "Rooftops" by Liz Lawrence, a talented young singer/songwriter from London, recorded on the Secret Garden Party site earlier in the summer. This is one of those songs I can't get out of my head -- perhaps because I spent so much time on rooftops in my New York and Boston days -- but it's so lovely that I really don't mind. (This one goes out to Tom Canty, Rick & Sheila Berry, Richard Salvucci, and Phil Hale, with whom I spent so many Newbury Street nights, back in my Twenties, "drinking in the sky and eating the stars.")

Third (below), "Dandelion" by Ruby and the Rib Cage,

a four-piece London band backing the amazing young singer known only as

Ruby, who has been getting a lot of attention at the summer festivals

this year (And is it just me, or does she look like she stepped out of a Rossitti painting?) This

particular performance was recorded back in March 2012, I'm not sure

where.

And oh heck, here's one more for you today:

Liz Lawrence again -- this time with the new video for "Sons and Daughters," her gorgeous, gorgeous song with Allman Brown.

August 17, 2013

Beyond the fields we know

Beyond the Fields We Know was the title of a story collection by the Irish fantasy master Lord Dunsany, and it's become a well-known phrase in the mythic arts field ever since, used to describ those times when we move past the comfortably familiar to venture into the great unknown. For all too many readers, set in their reading habits, simply trying out fiction by a brand new author is uncomfortably risky; they prefer to stay within their literary comfort zones. Thus a handful of familiar authors sell over and over, dominating the bookstore shelves and bestsellers' lists, while new writers find it harder and harder to get published at all these days.

If we don't -- each of us -- make a concerted, regular effort to travel "beyond the fields we know" by trying the work of first-time authors, publishers will simply not publish them; and self-publication isn't the answer to the problem if such books simply don't get read. Without the support of risk-taking readers, too many of the most interesting new writers (the quirky writers, the ground-breaking writers, the uncategorizable writers) will be stocking the shelves at Walmart and serving coffee at Starbucks, not writing, (the bills have to be paid, after all), and risk-taking, boundary-busting first novels will disappear ... instead of leading on to the second, third, fourth, and fifth novels that might become the bestsellers and prize-winners of the future.

Okay, I'll get off my soapbox now. All this is a long-winded way to say I want to recommend a first novel to you: A Certain Prophesy by Chagford author/artist Damien Hackney.

Okay, I'll get off my soapbox now. All this is a long-winded way to say I want to recommend a first novel to you: A Certain Prophesy by Chagford author/artist Damien Hackney.

A Certain Prophesy is a highly unusual, compelling read by an author who falls in the interstices between all the usual literary genres: the book is part bildungsroman, part supernatural thriller, part psychological exploration of grief and its aftermath, and part philophical inquiry into some of the thornier aspects of ethics, art, science and religion. By this description alone, you can see why the novel doesn't fit squarely into any one section of the bookstore, and that's precisely what makes A Certain Prophesy unique, challenging, and fascinating.

Set in modern-day England (in the city of Exeter, just up the road from here), A Certain Prophesy is, primarily, the psychological coming-of-age story of Immanuel ("Mani") Dunn -- a young artist whose success in the professional world has not been matched by the maturation of his spirit and soul, both of which were badly scarred by the trauma of his mother's early death. Damien's particular skill as a writer is in exploring the inner workings of the young man's mind as he tries to find his way not only through a plot delicately laced with supernatural elements, but also through the dark places of Mani's life as he seeks to find himself as a man, and as a hero, in the moral muddle of the modern world. Along the way, he's surrounded by a wide and vivid cast of characters, whose own journeys (and distinct world views) intersect with Mani's for good and for ill.

Does that sound challenging? It is, but the novel is also a page turner, particularly for those readers of a philosophical bent of mind. (I know that "suspenseful" and "philosophical" sound like contradictory modes, but somehow they aren't here.) I don't know any other book quite like A Certain Prophesy. Nor do I know many novelists so willing to tackle what it means to be a "good man" in the Western world in quite so straight-forward a way. Cool detachment and distancing irony being almost de riguer among many of our younger writers today, this is a brave book for looking asking hard questions...and doing so with an entirely open heart.

Please do give it a try. And this is the time to do it, because for this weekend only, through Monday August 19th, it available entirely for free to Kindle readers. Go here if you're in Europe; and here for American readers.

And to read about Damien's next writing project (involving fairies!) go here.

August 15, 2013

The Soul's Code

''Most artists are brought to their vocation when their own nascent gifts are awakened by the work of a master. That is to say, most artists are converted to art by art itself. Finding one’s voice isn’t just an emptying and purifying oneself of the words of others but an adopting and embracing of filiations, communities, and discourses. Inspiration could be called inhaling the memory of an act never experienced. Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void but out of chaos.'' ― Lewis Hyde (The Gift)

"Every artist joins a conversation that's been going on for generations,

even millennia, before he or she joins the scene." - John Barth

''What needs to be counted on to have a voice? Courage. Anger. Love.

Something to say; someone to speak to; someone to listen.'' - Terry

Tempest Williams (When Women Were Birds)

When you engage in a work that taps your talent and fuels your

passion -- that rises out of a great need in the world that you feel drawn

by conscience to meet -- therein lies your voice, your calling, your

soul's code." - Stephen Covey

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers