Terri Windling's Blog, page 185

July 21, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week, a quartet of lovely songs from the British Isles:

Above, Irish singer Mary Black joins Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh and the Donegal band Altan for a stirring performance of the Irish Gelic song "Siúil A Rúin," filmed in concert in Glasgow. (The English translation of the chorus is: Go, go, go my love/Go quietly and peacefully/Go to the door and fly with me.)

Below, Scots Gaelic singer Kathleen MacInnes performs "Oran a Cloiche (The Song of the Stone)" by Donald MacIntyre at a TransAtlantic Session in 2011, accompanied by Sarah Jarosz, Mike McGoldrick, Russ Barenberg, Donald Shaw, and Nollaig Casey. The song recounts the dramatic (but temporary) return of the Stone of Scone to Scotland in 1950, boldly retrieved from Westminister Abbey by four students on Christmas Day. (You can read the song's lyrics in translation here, and the full story of the stone here.) MacInnes comes from the Outer Hebrides and is now based in Glasgow.

Next:

"Ye Banks and Braes," performed by Scottish singer/songwriter Holly Tomás, from Edinburgh. The lyrics, based on a Robert Burns poem, are written from the point of view of a love-lorn woman as she walks by the banks of the River Doon in Ayrshire.

And last:

The Poozies, a wonderful Anglo-Scots all-women trad band, with their gorgeous song, "We Build Fires." The song refers both to the ancient system of building beacon fires on high hills as communication and defense signals, and also to the pagan ceremonial fires lit at various sacred times during the lunar calendar.

The

Poozies have had several line-ups over the twenty years that they've been performing, but in this video it's: Sally Barker (lead vocals and guitar), Jenny Gardner (fiddle), Mary Macmaster (harp), Pasty Seddon (harp), and Karen Tweed (accordion). If you'd like to hear more music from The Poozies this morning, go here and here, or try any of their seven CDs.

July 19, 2013

A gentle reminder...

Just two weeks left, if you're planning to catch the Widdershins exhibition. The poster image here is a detail from an extraordinary new painting by Virginia Lee, which is, in my humble opinion, worth a trip to Moretonhampstead all by itself. (But you'll also find many other treasures there.)

July 18, 2013

Coffee Break

This is the spot where Tilly and I

often go for a mid-morning coffee break, for it's the perfect place to linger for a stolen moment in a busy work day. Sitting in the old oak's shade, bare feet cooled by gold water in a pebble-bottomed stream, I read or

write while Tilly prowls, or splashes, or sits contentedly beside me.

It's also a spot favored by animals

that live or graze on Nattadon Hill; we find deer and fox prints in

the soil (and sometimes badger too), and once

encountered a large hare, who blinked at us and then strolled

leisurely away.

Most often it's the wild ponies who

join us, traveling down from the moor to drink and bathe and cool themselves among the leaves...

...or cows from the lower

field, much more standoffish since their calves were born.

Our foot

and paw prints mix with theirs, just two more animals on the hill,

drawn to cold water like all the rest....

And just as food tastes best when eaten

outdoors, and coffee transforms into the nectar of the

gods, a good book read in an oak tree's shade becomes somehow even better -- as

though the oak reads over my shoulder, murmuring its approval and pleasure. I lose myself, bees humming around me, the church bells

ringing faintly in the distance and sheep calling from the distant

hills...

...but when my cup is empty, I close the book, slip on my

shoes, and say, "Come, love. Let's go home."

Tilly leads the way down the streamside path that winds back to studio, her nose twitching as she reads the latest scent-news carried by the wind.

And I bring it all back to my desk: the wind, the water, the woods, and the wild. Words like fox prints tracked

across the page. Dark coffee, bright sun; the bitter and the sweet; the rustle of the ponies and the hare's bold gaze. The simple things that keep us going.

That I'm grateful for.

That aren't simple at all.

July 17, 2013

Into the Woods, 19: The Forest of Stories (Part II)

In her book Enchantedment Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood, Maria Tatar defends children's literature against the "Facts, Nothing But the Facts" brigade, writing:

"In 'Potter Has a Limited Effect on Reading Habits,' Michael L. Kamil worried that schools have 'overemphasized' reading 'stories and literature.' Children are better off 'reading for information' on the Internet, since they will one day enter a labor force that requires 'zero narrative' reading skills. Dicken's Thomas Gradgrind, a 'man of facts,' expressed equally dreary ideas more than a century ago about what children need. In 'Murdering the Innocents,' the first chapter of Hard Times, he insists with stern passion: 'Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else and root out everything else.... Stick to Facts, sir!'

"Stories ignite not just the imagination but also intellectual curiosity, tugging at us and drawing us into symbolic other worlds, where we all become wide-eyed tourists, eager to take in the sights. Like Lucy on the threshold to Narnia, we are both 'excited' and 'inquisitive.' Reading has a magical way of changing our affect, turning us into serene wanderers and visionaries....

"As readers we traverse vast regions 'without moving

an inch,' discovering the thrills of story worlds, recoiling from their

villains and empathizing with their champions, all the while shaping

our values as we build a relationship with the book and discover its

real magic -- that black marks on a white page can create scenes of

breathtaking beauty and heartstopping horror in our minds."

"Children know themselves to be the most single most powerless unit

in today's world, " says Jane Yolen (in her indispensible book Touch Magic: Fantasy Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood.)

"They cannot support themselves, they cannot vote, they have little

physical strength, they have but a small knowledge of the universe. They

cannot see over walls. As infants they are entirely dependant upon the

kindness of adults, and as they grow up further, they are still small

satellites in an adult world. They dream of being big enough and old

enough to tame the Wild Things.

"In reality, those Wild Things could well devour them.

"Therefore we give them tools with which to keep the real world at

bay until they are ready for it. We give them teachers, we give them

toys, we give them prayers and chants and cultural attitudes, and

surround them with tribes and tribal constraints.

"We give them stories.

"The stories we give our children are, in some ways, the most

important pieces in the ethical and moral puzzle they are asked to solve

from birth on."

"I believe that maturity is not an outgrowing but a growing up," writes Ursula K. Le Guin

"that an adult is not a dead child, but a child who has survived. I

believe that all the best faculties of a mature human being exist in the

child, and that if these faculties are encouraged in youth they will

act well and wisely in the adult, but if they are repressed and denied

in the child they will stunt and cripple the adult personality. And

finally, I believe that one of the most deeply human, and humane, of

these faculties is the power of imagination: so that it is our pleasant

duty, as librarians, or teachers, or parents, or writers, or simply as

grownups, to encourage that faculty of imagination in our children, to

encourage it to grow freely, to flourish, like the green bay tree, by

giving it the best, absolutely the best and purest, nourishment that it

can absorb. And never, under any circumstances, to squelch it, or sneer

at it, or imply that it is childish, or unmanly, or untrue.

"For

fantasy is true, of course. It isn't factual, but it's true. Children

know that. Adults know it too, and that's precisely why many of them are

afraid of fantasy. They know that its truth challenges, even threatens,

all that is false, all that is phony, unnecessary, and trivial in the

life that they have let themselves be forced into living. They're

afraid of dragons, because they are afraid of freedom." (The Language of the Night)

In Don't Tell the Grown-ups, Alison Lurie reflects on the enduring power of classic tales:

“The great subversive works of children's literature suggest that there

are other views of human life besides those of the shopping mall and the

corporation. They mock current assumptions and express the imaginative,

unconventional, noncommercial view of the world in its simplest and

purest form. They appeal to the imaginative, questioning, rebellious

child within all of us, renew our instinctive energy, and act as a force

for change. This is why such literature is worthy of our attention and

will endure long after more conventional tales have been forgotten.”

“There are some themes, some subjects, too large for adult fiction; they

can only be dealt with adequately in a children's book,” says Philip Pullman slyly. And perhaps he's right.

“Fiction is a kind of compassion-generating machine that saves us from

sloth," explains George Saunders (author of one of my favorite children's books, The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip). "Is life kind or cruel? Yes, Literature answers. Are people good

or bad? You bet, says Literature. But unlike other systems of knowing,

Literature declines to eradicate one truth in favor of another; rather,

it teaches us to abide with the fact that, in their own way, all things

are true, and helps us, in the face of this terrifying knowledge,

continually push ourselves in the direction of Open the Hell Up."

E.B. White (author of the children's classic's Stuart Little and Charlotte's Web) noted that “reading is the work of an alert mind, is demanding, and under ideal

conditions produces finally a kind of ecstasy. This gives the experience

of reading a sublimity and power unequalled by any other form of

communication.”

"Literature can shake our lives to the core," John Barth once said in an interview. "Our life can turn around

corners by simply reading words on a page....Literature remains the

only medium that gets directly inside our interior life."

And from Jorge Luis Borges: "I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.”

There are as many reasons to read, of course, as there are books, and readers to pluck them from the shelves. We read for pleasure, distraction, enlightenment, escape, instruction, aesthetic appreciation, even salvation...and sometimes simply to feed a fierce addiction to words printed on a crisp white page.

“I read," said Ann Tyler, "so that I can live more than one life in more than one place.”

Oh yes, that's it precisely.

“I know there are people who don’t read fiction at all," mused Diane Setterfield; "and I find it

hard to understand how they can bear to be in the same head all the

time."

Indeed. I've wondered that too.

Although reading is a solitary act, as readers we are not solitary creatures, not really, for our bookshelves contain multitudes. "We live inside each other's thoughts and works," writes Rebecca Solnit (in The Faraway Nearby), explicating the ways that, culturally, none of us can claim true solitude at all:

"As I write, I sit in a building erecting on a steep slope, so that what is on the first floor uphill is the second floor downhill. Someone thought through the site and designed this structure specifically for this corner; someone cut lumber in a forest up or down the coast; someone framed the structure, plastered the walls, laid the oak floorboards, the pipes, and the wires; someone designed and others made the chair I sit on, all of it long before I was born.

"Long before that people established ideas about what houses and chairs should be. I am in this moment hosted by anonymous craftspeople long gone, or rather by their ideas and labor, surrounded by more ghosts in the books in the room and other remnants of trees, the language I speak, the body I inhabit with the adaptations and innumerable ancestors running through it, the city around me, the countless gestures, acts, devotions that keep making the world.

"I am, we are, the inmost of an endless series of Russian dolls; you who read are now encased within a layer I built for you, or perhaps my stories are now inside you. We live as literally as that within each other's thoughts and works, in this world that is being made all the time, by all of us, out of beliefs and acts, information and materials."

Stories are one of the primary materials with with we shape our lives, our communities, our children, ourselves. Stories, as Angela Carter once said, are "the most vital connection we have with the

imaginations of the ordinary men and women whose labor created our

world". . .

. . .which in turn reminds me of these words by the Native American poet/novelist/essayist Linda Hogan (in her gorgeous essay collection Dwellings): "It is winter and there is smoke from the fires. The square, lighted windows of the houses are fogging over. It is a world of elemental attention, of all things working together, listening to what speaks in the blood...Suddenly all my ancestors are behind me. Be still, they say. Watch and listen. You are the result of the love of thousands."

The writers of all the books we've loved, and the tellers of the tales that have formed and colored our souls, are truly our ancestors too: not of the blood but of the spirit. Each

of us, by this count, is indeed the result of the love of thousands: we are the children of stories, inherited and then passed on to those who come behind us.

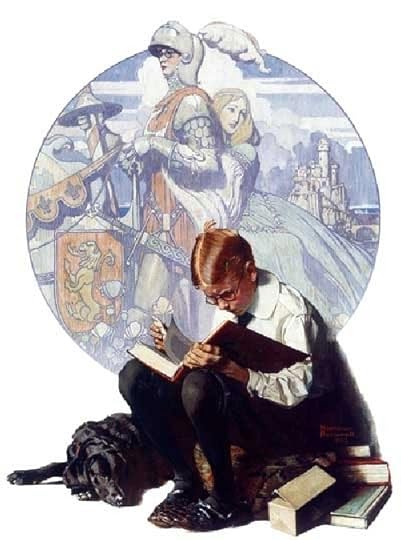

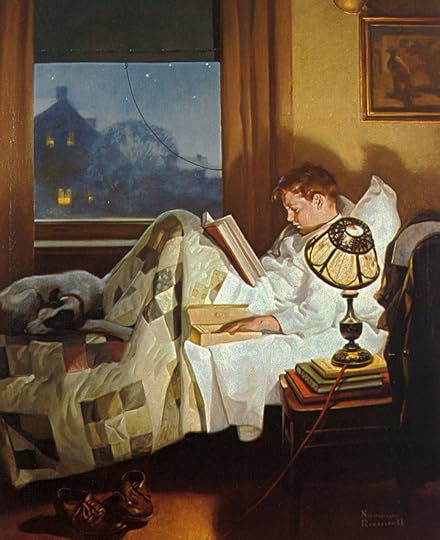

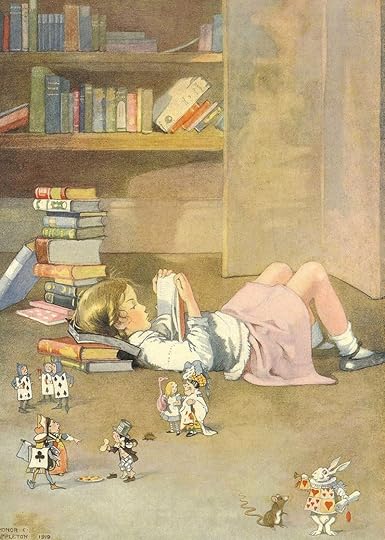

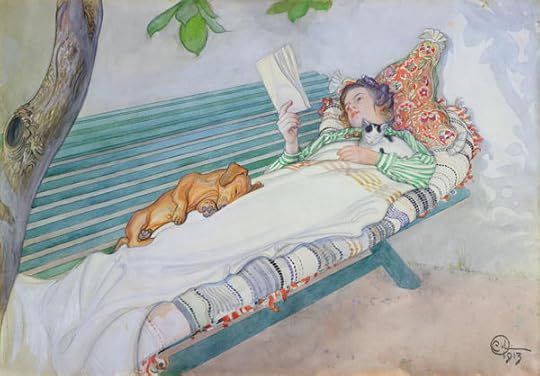

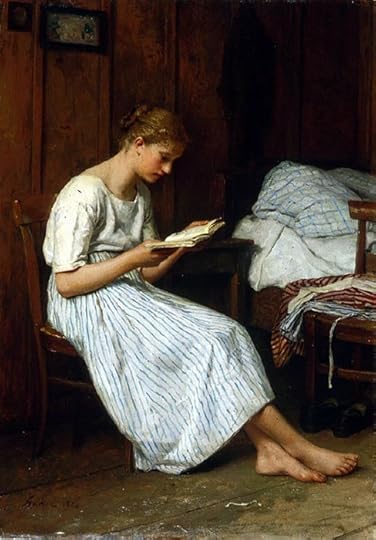

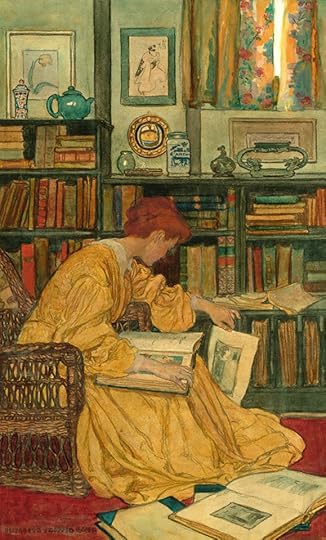

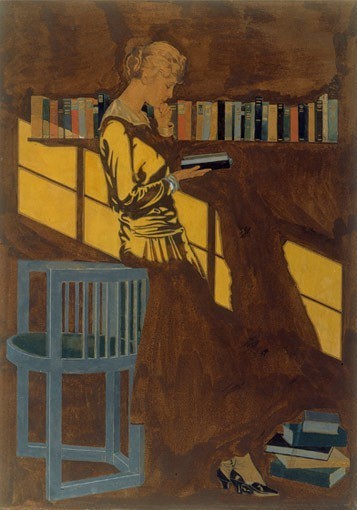

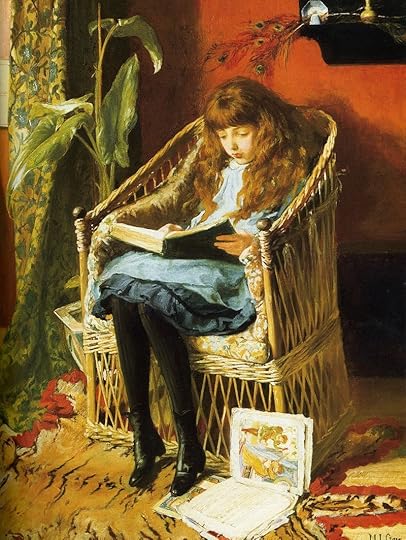

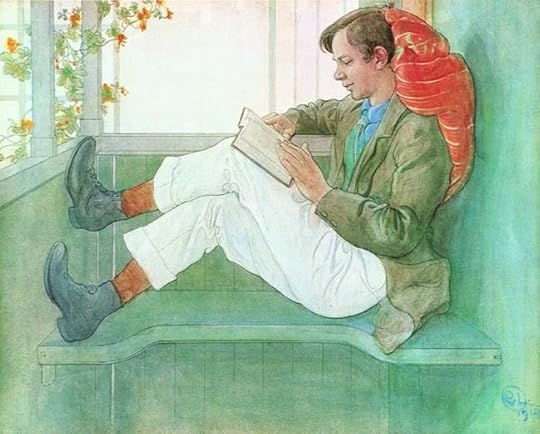

The "books and reading" imagery above: "The Lands of Enchantment" and "Crackers in Bed" by Normal Rockwell (American, 1994-1978); "The Story of Golden Locks" and "An Interesting Book" by Seymour Joseph Guy (American, 1824-1910); "In the Parlour" by Izsák Perlmutter (Hungarian, 1866-1932) / "Fairy Tales" by Jessie Willcox Smith (American, 1853-1935 ); "Alice in Wonderland by George Dunlop Leslie (English, 1834-1921); "Wonderland" by Adelaide Claxton (English, 1835-1905); "My Books by Honor C. Appleton (English, 1879-1951); "At Rest" by Carl Larsson (Swedish, 1853-1919); "The Artist's Wife Reading" by Leopold von Kalckreuth (German, 1855-1928); "Girl Reading" by Winslow Homer (American, 1836-1910); "Girl Reading in a Hammock" by Robert Archibald Graafland (Dutch, 1875 - 1940); "Girl Reading in the Landscape" by Ada Thilén (Finnish, 1852-1933); "A Gotthelf Reader" by Albert Anker (Swiss, 1831-1910); "Breton Children Reading" by Emile Vernon (French, 1872-1919); "Daydreaming" and "The Library" by Honor C. Appleton (English, 1879-1951); "The Library" by Elizabeth Shippen Green (American, 1871-1954); "Spring Morning" by Lilian Westcott Hale (1881-1963); "Reading" by Charles Francois Prosper Guérin (French, 1875-1939); "Reading" by Coles Phillips (American, 1880-1927); an illustration from the Butterick Poster Calendar. artist unknown (American, 1904; ""Little Women" by Jessie Willcox Smith (American, 1853-1935 ); "An Interlude" by William Sergeant Kendall (American, 1869-1938); and "This is Our Corner" by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (Dutch/English, 1836-1912).

July 16, 2013

Going outward and beyond

I sit by the banks of a cold, clear stream, my toes in the water, my nose in book, my thoughts far away. Tilly barks, just once, to let me know we have visitors....

I am reading Rebecca Solnit's new memoir, The Faraway Nearby, and this passage has arrested my attention:

"I was asked to talk to a roomful of undergraduates in a university in a beautiful coastal valley. I talked about place, about the way we often talk about love of place, but seldom how places love us back, of what they give us. They give us continuity, something to return to, and offer familiarity that allows some portion of our lives to remain collected and coherent.

"They give us an expansive scale in whch our troubles are set into

context, in which the largeness of the world is a balm to loss, trouble,

and ugliness.

"And distant places give us refuge in territories where our own histories

aren't so deeply entrenched and we can imagine other stories, other

selves, or just drink up quiet and respite.

"The bigness of the world is redemption.

"Despair compresses you into a

small space, and a depression is literally a hollow in the ground. To

dig deeper into the self, to go underground, is sometimes necessary, but

so is the other route of getting out of yourself, into the larger

world, into the openness in which you need not clutch your story and

your troubles so tightly to your chest.

"Being able to travel in both

ways matters, and sometimes the way back into the heart of the question

begins by going outward and beyond. This is the expansiveness that comes

literally in a landscape or that tugs you out of yourself in a

story.....

"I told the student that they were at an age when they might begin to

choose the places that would sustain them the rest of their lives, that

places were much more reliable than human beings, and often much

longer-lasting, and I asked each of them where they felt at home. They

answered, each of them, down the rows, for an hour, the immigrants who

had never stayed anywhere long or left a familiar world behind, the

teenagers who'd left the home they'd spent their whole lives in for the

first time, the ones who loved or missed familiar landscapes and the

ones who had not yet noticed them.

"I found books and places before I found friends and mentors, and they

gave me a lot, if not quite what a human being would. As a child, I spun

outward in trouble, for in that inside-out world [of my family],

everywhere but home was safe. Happily, the oaks were there, the hills,

the creeks, the groves, the birds, the old dairy and horse ranches, the

rock outcroppings, the open space inviting me to leap out of the

personal into the embrace of the nonhuman world."

In her luminous, collage-like memoir, Solnit talks about writing, art, fairy tales, the natural world, surviving cancer, her difficult relationship with her mother, and many other things that are deeply personal to me too, and perhaps to some of you as well. I highly recommend it....alongside her other fine books: Wanderlust, Hope in the Dark, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, etc..

"We think we tell stories," she writes shrewdly, "but stories often tell us, tell us to love or hate, to see or be seen. Often, too often, stories saddle us, ride us, whip us onward, tell us what to do, and we do it without questioning. The task of learning to be free requires learning to hear them, to question them, to pause and hear silence, to name them, and then become a story-teller."

Which is exactly what Solnit has accomplished here, in her deeply moving and beautifully crafted new book.

As for me, I've become a story-teller too, re-telling my life, re-making my world, and rooting here on the far side of the Atlantic, in this place of green grass, gold water, and wild ponies. Stories are powerful things, my dears. So tell yours wisely. Make it beautiful. Make it good.

Into the Woods, 19: In the Forest of Stories (Part I)

"At the beginning of my life was a forest," says Francis Spufford (in his charming memoir, The Child That Books Built). He means an actual forest (an 18th century park, turned wild, close to his parents' house), but also the metaphorical forest at the beginning of fiction, a forest made of stories:

"This one spread forever. Its canopy of branches covered the land, covered every form of the land, whether the ground beneath jagged or rolled. The forest went on. Up in its living roof birds flitted through greeness and bright air, but down between the trunks of the many trees there were shadows, there was dark. When you walked this forest, your feet made rustling sounds, but the

noises you made yourself were not the only noises, oh no. Twigs snapped;

breezes brought snatches of what might be voices. Lumpings and

crashings in the undergrowth marked the passages of heavy things far

off, or suddenly nearby.

"This was a populated wood. All wild creature lived here, dangerous or

benign, according to their natures. And all the other travelers you had

heard of were in the wood too, at

this very moment: kings and knights, youngest sons and third daughters,

simpletons and outlaws, a small girl whose bright hood flickered between

the pine trees like a scarlet beacon...

"...and a wolf moving on a different

vector to intercept her at the

cottage, purposefully arrowing through thickets, leaving a track of

disturbance behind him as an alpha particle does when it streaks across a

cloud chamber....

"These people, these dangers, were not far away, but you would never meet them. The adventures could never intersect, although they shared the forest; although they would be joined in time by more, and still more, wayfarers, the more elaborated beings who came from the more elaborate worlds of privately read story, rather than the primitives of fairy tale. Mole from Wind in the Willows would pelt in hunted panic through a nighttime tract of the forest, whose bare boughs jutted 'like a black reef in some still  southern sea.' Through twisted foliage would creep Wart, in The Sword and the Stone, past pale-eyed predators and baby dragons hissing under the stones, to his first sight of Merlyn swearing at a bucket. But each traveled separately, because it was the nature of the forest that you were alone in it. It was the place in which by definition you had no companions, and no resources except your uncertain self. It was the Wild, were relationship ceases, where connection is suspended."

southern sea.' Through twisted foliage would creep Wart, in The Sword and the Stone, past pale-eyed predators and baby dragons hissing under the stones, to his first sight of Merlyn swearing at a bucket. But each traveled separately, because it was the nature of the forest that you were alone in it. It was the place in which by definition you had no companions, and no resources except your uncertain self. It was the Wild, were relationship ceases, where connection is suspended."

There would be encounters in the forest, Spufford adds, for the solitary nature of a young hero's journey is spiritual and emotional, not literal. "Eventually the state that the whole wood represented [for you, the reader/traveler] would be embodied. One of those rustlings would become a footfall, would become a meeting, and you stepped forward to it as best you could. You could no more avoid the encounters of the wood -- all significant, all in their way tests -- than you could cross it on a neat dependable path. It existed to cause changes, and it had no pattern you could take hold of in the hope of evading change. You never went out the same as you went in."

Rebecca Solnit also examines the power of stories in childhood in her gorgeous new memoir, The Faraway Goodbye:

"Like many others who turn into writers," she tells us, "I disappeared into books when I was very young, disappeared into them like someone running into the woods. What surprised and still surprises me is that there was another side to the forest of stories and the solitude, that I came out that other side and met people there. Writers are solitaries by vocation and necessity. I sometimes think the test is not so much talent, which is not as rare as people think, but purpose or vocation, which manifests in part as the ability to endure a lot of solitude and keep working. Before writers are writers they are readers, living in books, through books, in the lives of others that are also the heads of others, in that act that is so intimate and yet so alone.

"These vanishing acts are a staple of children's books, which often tell of adventures that are magical because they travel between levels and kinds of reality, and the crossing over is often an initiation into power and into responsibility. They are in a sense allegories first for the act of reading, of entering an imaginary world, and then of the way that the world we actually inhabit is made up of stories, images, collective beliefs, all the immaterial appurtenances we call ideology and culture, the pictures we wander in and out of all the time."

In the pages of Enchantment Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood, the brilliant fairy tale scholar Maria Tatar notes:

"The journey as a master trope for the reading experience becomes evident in our use of the term armchair traveler, as well as in a wide range of velvety reports about the reading

experience. 'Most of the time I simply enjoyed the luxurious sensation

of being carried away by the words, and felt, in a very physical sense,

that I was actually traveling somewhere wonderfully remote, to a place

that I hardly dared glimpse on the secret last page of the book,'

Alberto Manguel reports in his history of reading. The novelist Katie

Roiphe describes a similar sense of kinetic exhileration while reading

during recovery from a childhood bout of pneumonia: 'I broke open the

books the chased the words. It was a breathless activity like running.'"

But it is deeply paradoxical, Tatar points out, "that a practice

involving nothing but sitting still and staring at black marks on a

white page is pitched as travel with the added benefit of powerful

sensory stimulation. Reading is often said to open up alternate world

superior to the one inhabited by the reader, producing an improbable

rush of life.

"'From that first moment in the schoolroom at Chatres,' C.S. Lewis recalls in contemplating the role of books in his life, 'my

secret imaginative life began to be so important and so distinct from

my outer life that I almost have to tell two separate stories.' It was in that imaginative world that the author of The Chronicles of Narnia felt 'stabs of joy' so keen that they rivaled any feelings attending real-life experience."

There is a point for most

bookish children when the choice of reading material becomes

private and deeply personal; when adult attempts to guide or share the reading

journey are no longer always welcome. From the bedside tales of our youngest years

we progress to reading with a parent or teacher's help, and then on to reading all by ourselves. Books become our private treasures, solitary journeys into

wondrous places that adults (except that magical creature called an Author) would surely

not understand...or so we think, as each succesive generation discovers the vast Forest of Stories anew.

And indeed, some adults don't understand. Many children tagged as "bookworms" endure a tedious amount of teasing (or worse) from non-readers, as if a passion for print is odd, effete, perhaps even slightly unsavory. "When I was a boy,"the novelist/playwright/critic Robertson Davies once wrote, "many patronizing adults assured me that there was nothing I liked better than to 'curl up with a book.' I despised them. I have never curled."

"Each time a child opens a book," writes Lois Lowry, "he pushes

open the gate that separates him from Elsewhere. It gives him choices.

It gives him freedom. Those are magnificent, wonderfully unsafe things."

"Books may be the only true magic," says Alice Hoffman.

And indeed they are.

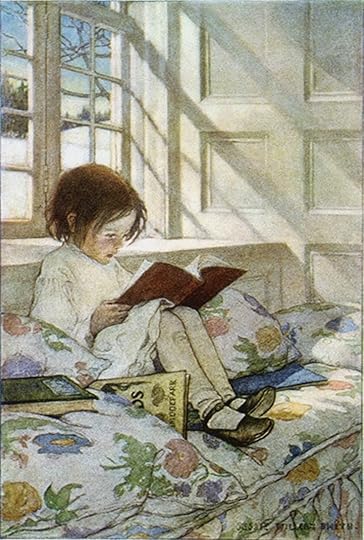

The "books and reading" imagery above: A charming, widely reprinted photograph from Transition Voice magazine; Leshy Forest illustrations by my friend and neighbor Rima Staines; four enchanting "book sculptures" by Su Blackwell, based in London; "Mole, Ratty, and Otter" by E.H. Shepard (1879-1976); "Fairy Tales" by Mary L. Gow (English, 1851-1929); two paintings of children reading by Jessica Willcox Smith (American, 1863-1935); "Five Little Pigs" by Elizabeth Shippen Green (American, 1871-1954);

"Jungle Tales" by James J. Shannon (Irish-American, 1862-1923); "Three Girls Reading" by Walter Firle (German, 1859-1929); "Children Reading" by Pekka Halonen (Finnish, 1865-1933);

"Young Girl Reading" by Henri Lebasque (French, 1865-1937); four paintings by Carl Larrson (Swedish, 1853-1991) of his children reading; "Little Red," one of my favorite paintings by Jackie Morris, based in Wales; and

a fabulous painting by Claire Fletcher at the Black Winkle Studio in Hastings (England).

I highly recommend the book The Red Rose Girls by Alice A. Carter, about the art and braided lives of Jessica Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green and Violet Oakley. The three met in an illustration class taught by Howard Pyle and spent many years living and working together in a rose-clad house in Pennylvania.

Into the Woods, 19: In the Forest of Stories

"At the beginning of my life was a forest," says Francis Spufford (in his charming memoir, The Child That Books Built). He means an actual forest (an 18th century park, turned wild, close to his parents' house), but also the metaphorical forest at the beginning of fiction, a forest made of stories:

"This one spread forever. Its canopy of branches covered the land, covered every form of the land, whether the ground beneath jagged or rolled. The forest went on. Up in its living roof birds flitted through greeness and bright air, but down between the trunks of the many trees there were shadows, there was dark. When you walked this forest, your feet made rustling sounds, but the

noises you made yourself were not the only noises, oh no. Twigs snapped;

breezes brought snatches of what might be voices. Lumpings and

crashings in the undergrowth marked the passages of heavy things far

off, or suddenly nearby.

"This was a populated wood. All wild creature lived here, dangerous or

benign, according to their natures. And all the other travelers you had

heard of were in the wood too, at

this very moment: kings and knights, youngest sons and third daughters,

simpletons and outlaws, a small girl whose bright hood flickered between

the pine trees like a scarlet beacon...

"...and a wolf moving on a different

vector to intercept her at the

cottage, purposefully arrowing through thickets, leaving a track of

disturbance behind him as an alpha particle does when it streaks across a

cloud chamber....

"These people, these dangers, were not far away, but you would never meet them. The adventures could never intersect, although they shared the forest; although they would be joined in time by more, and still more, wayfarers, the more elaborated beings who came from the more elaborate worlds of privately read story, rather than the primitives of fairy tale. Mole from Wind in the Willows would pelt in hunted panic through a nighttime tract of the forest, whose bare boughs jutted 'like a black reef in some still  southern sea.' Through twisted foliage would creep Wart, in The Sword and the Stone, past pale-eyed predators and baby dragons hissing under the stones, to his first sight of Merlyn swearing at a bucket. But each traveled separately, because it was the nature of the forest that you were alone in it. It was the place in which by definition you had no companions, and no resources except your uncertain self. It was the Wild, were relationship ceases, where connection is suspended."

southern sea.' Through twisted foliage would creep Wart, in The Sword and the Stone, past pale-eyed predators and baby dragons hissing under the stones, to his first sight of Merlyn swearing at a bucket. But each traveled separately, because it was the nature of the forest that you were alone in it. It was the place in which by definition you had no companions, and no resources except your uncertain self. It was the Wild, were relationship ceases, where connection is suspended."

There would be encounters in the forest, Spufford adds, for the solitary nature of a young hero's journey is spiritual and emotional, not literal. "Eventually the state that the whole wood represented [for you, the reader/traveler] would be embodied. One of those rustlings would become a footfall, would become a meeting, and you stepped forward to it as best you could. You could no more avoid the encounters of the wood -- all significant, all in their way tests -- than you could cross it on a neat dependable path. It existed to cause changes, and it had no pattern you could take hold of in the hope of evading change. You never went out the same as you went in."

Rebecca Solnit also examines the power of stories in childhood in her gorgeous new memoir, The Faraway Goodbye:

"Like many others who turn into writers," she tells us, "I disappeared into books when I was very young, disappeared into them like someone running into the woods. What surprised and still surprises me is that there was another side to the forest of stories and the solitude, that I came out that other side and met people there. Writers are solitaries by vocation and necessity. I sometimes think the test is not so much talent, which is not as rare as people think, but purpose or vocation, which manifests in part as the ability to endure a lot of solitude and keep working. Before writers are writers they are readers, living in books, through books, in the lives of others that are also the heads of others, in that act that is so intimate and yet so alone.

"These vanishing acts are a staple of children's books, which often tell of adventures that are magical because they travel between levels and kinds of reality, and the crossing over is often an initiation into power and into responsibility. They are in a sense allegories first for the act of reading, of entering an imaginary world, and then of the way that the world we actually inhabit is made up of stories, images, collective beliefs, all the immaterial appurtenances we call ideology and culture, the pictures we wander in and out of all the time."

In the pages of Enchantment Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood, the brilliant fairy tale scholar Maria Tatar notes:

"The journey as a master trope for the reading experience becomes evident in our use of the term armchair traveler, as well as in a wide range of velvety reports about the reading

experience. 'Most of the time I simply enjoyed the luxurious sensation

of being carried away by the words, and felt, in a very physical sense,

that I was actually traveling somewhere wonderfully remote, to a place

that I hardly dared glimpse on the secret last page of the book,'

Alberto Manguel reports in his history of reading. The novelist Katie

Roiphe describes a similar sense of kinetic exhileration while reading

during recovery from a childhood bout of pneumonia: 'I broke open the

books the chased the words. It was a breathless activity like running.'"

But it is deeply paradoxical, Tatar points out, "that a practice

involving nothing but sitting still and staring at black marks on a

white page is pitched as travel with the added benefit of powerful

sensory stimulation. Reading is often said to open up alternate world

superior to the one inhabited by the reader, producing an improbable

rush of life.

"'From that first moment in the schoolroom at Chatres,' C.S. Lewis recalls in contemplating the role of books in his life, 'my

secret imaginative life began to be so important and so distinct from

my outer life that I almost have to tell two separate stories.' It was in that imaginative world that the author of The Chronicles of Narnia felt 'stabs of joy' so keen that they rivaled any feelings attending real-life experience."

There is a point for most

bookish children when the choice of reading material becomes

private and deeply personal; when adult attempts to guide or share the reading

journey are no longer always welcome. From the bedside tales of our youngest years

we progress to reading with a parent or teacher's help, and then on to reading all by ourselves. Books become our private treasures, solitary journeys into

wondrous places that adults (except that magical creature called an Author) would surely

not understand...or so we think, as each succesive generation discovers the vast Forest of Stories anew.

And indeed, some adults don't understand. Many children tagged as "bookworms" endure a tedious amount of teasing (or worse) from non-readers, as if a passion for print is odd, effete, perhaps even slightly unsavory. "When I was a boy,"the novelist/playwright/critic Robertson Davies once wrote, "many patronizing adults assured me that there was nothing I liked better than to 'curl up with a book.' I despised them. I have never curled."

"Each time a child opens a book," writes Lois Lowry, "he pushes

open the gate that separates him from Elsewhere. It gives him choices.

It gives him freedom. Those are magnificent, wonderfully unsafe things."

"Books may be the only true magic," says Alice Hoffman.

And indeed they are.

The "books and reading" imagery above: A charming, widely reprinted photograph from Transition Voice magazine; Leshy Forest illustrations by my friend and neighbor Rima Staines; four enchanting "book sculptures" by Su Blackwell, based in London; "Mole, Ratty, and Otter" by E.H. Shepard (1879-1976); "Fairy Tales" by Mary L. Gow (English, 1851-1929); two paintings of children reading by Jessica Willcox Smith (American, 1863-1935); "Five Little Pigs" by Elizabeth Shippen Green (American, 1871-1954);

"Jungle Tales" by James J. Shannon (Irish-American, 1862-1923); "Three Girls Reading" by Walter Firle (German, 1859-1929); "Children Reading" by Pekka Halonen (Finnish, 1865-1933);

"Young Girl Reading" by Henri Lebasque (French, 1865-1937); four paintings by Carl Larrson (Swedish, 1853-1991) of his children reading; "Little Red," one of my favorite paintings by Jackie Morris, based in Wales; and

a fabulous painting by Claire Fletcher at the Black Winkle Studio in Hastings (England).

I highly recommend the book The Red Rose Girls by Alice A. Carter, about the art and braided lives of Jessica Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green and Violet Oakley. The three met in an illustration class taught by Howard Pyle and spent many years living and working together in a rose-clad house in Pennylvania.

July 14, 2013

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today's tunes come from the Canadian roots duo Madison Violet (Brenley MacEachern and Lisa MacIsaac, often accompanied by Adrian Lawryshyn on bass). I love these two women for their song-writing skills, bluegrass influences, and exquisite harmonies.

Above: "The Small of My Heart," performed on the Music Fog bus in Memphis, Tennessee. The song comes from Madison Violet's fourth album, No Fool For Trying.

Below, "The Ransom" (from the same album), a poignant song about life on the road as a musician...and the financial ups-and-downs so familiar to many of us in arts professions. This was also a Music Fog performance, this time at the Mansion on O, in Washington, DC.

And last:

"Lauralee," performed at a Folk Alley gig in Kent, Ohio.

July 13, 2013

Into the Woods, 18: Following the Deer (L'Envoi)

Deer Park

by Wang Wei

translated from the Chinese by David Hinton

No one seen. Among empty mountains,

hints of driftng voice, faint, no more.

Entering these deep woods, late sunlight

flares on green moss again, and rises.

* * *

Goodbye, deer friends, goodbye....

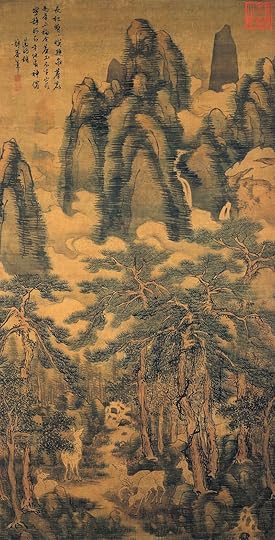

The poem above, by the Chinese painter/poet Wang Wei, was written during the Tang Dynasty, circa 750. (The poem has been translated into English many times, but David Hinton's well-known translation, and Billy Merrell's more recent translation, are the ones I love best.)

The first image above is "Tall Pine Trees and Five Deer" by Dai Jin (a.k.a. Tai Chin, 1833-1462), founder of the Zhe School of Ming Dynasty painting. (Alas, none of Wang Wei's paintings have surived.) The second image is "Roe Deer in the Forest" by the award-winning animal photographer Ben Hall.

July 11, 2013

Into the Woods, 18: Following the Deer (Part IV)

Psalm

by George Oppen

Veritas sequitur ...

In the small beauty of the forest

The wild deer bedding down —

That they are there!

Their eyes

Effortless, the soft lips

Nuzzle and the alien small teeth

Tear at the grass

The roots of it

Dangle from their mouths

Scattering earth in the strange woods.

They who are there.

Their paths

Nibbled thru the fields, the leaves that shade them

Hang in the distances

Of sun

The small nouns

Crying faith

In this in which the wild deer

Startle, and stare out.

skin

by Lynn Hardaker

i press

ochred hands onto the walls of this cave. my skin. my shelter.

my fingers crawl like night insects

to sing the running of the animals,

the wind of the chase, the beating of hearts and hooves

across the plains, of stone and dust.

each night i dream the chase

across my eyes’ black-lidded sky

each night

my body slick with sweat and smeared with ash

i run

as i run,

i hear the beating of the drum i’ve made -

taught and resonant - from my own skin,

feel the weight of the weapon i’ve made

from my own bone.

i leave the fire-painted walls

of this illusion

and i run

under the cool, many-eyed gaze of the night

i run until i feel my heart will beat its last beat and tear through my skin

i stop

my fear as dry as the dirt in my mouth.

i lower my antlers to the pool

and drink the stars.

The Faces of Deer

by Mary Oliver

When for too long I don't go deep enough

into the woods to see them, they begin to

enter my dreams. Yes, there they are, in the

pinewoods of my inner life. I want to live a life

full of modesty and praise. Each hoof of each

animal makes the sign of a heart as it touches

then lifts away from the ground. Unless you

believe that heaven is very near, how will you

find it? Their eyes are pools in which one

would be content, on any summer afternoon,

to swim away through the door of the world.

Then, love and its blessing. Then: heaven.

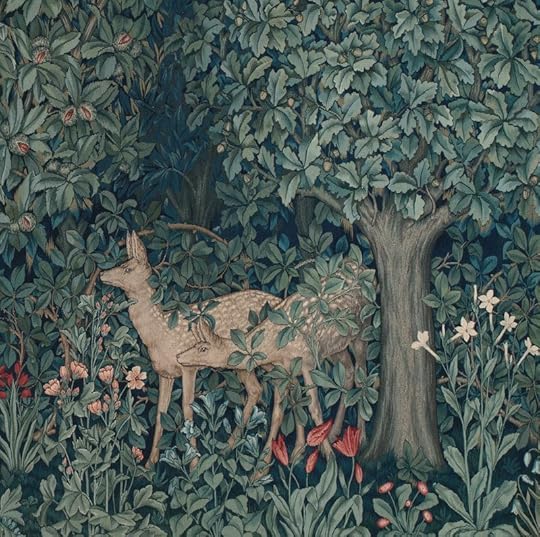

Deer tapestries above: The Woodland tapestry designed by John Henry Dearle for Morris & Co. (English, late 19th century); The Quest for the Holy Grail tapestry designed by William Morris for Morris & Co. (English, late 19th century); a detail from one of the four Devonshire Hunting Tapesteries (medieval French); one of the seven tapestries in the Hunt of the Unicorn series (medieval Dutch); and Tilly sits with the winged deer in the tapestry hanging over the studio sofa. (The design is medieval French.)

Publication credits: "Psalm" by George Oppen was published in New Collected Poems by George Oppen, 1965; "skin" by Lynn Hardaker was published in Mythic Delirium # 28, Winter/Spring 2013 issue; "The Faces of Deer" by Mary Oliver was published in New & Selected Poems, Vol. 2 by Mary Oliver, 2005.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 707 followers