Into the Woods, 9: Wild Children

Today I'm on the trail of the Wild Children of myth, lore, and fantasy: children lost in the forest, abandoned, stolen, reared by wild animals, and those for whom wilderness is their natural element and home.

Tales of babies left in the woods (and other forms of wilderness) can found in the myths, legends, and sacred texts of cultures all around the globe. The infant is usually of noble birth, abandoned and left to certain death in order to thwart a prophesy -- but  fate intervenes, the child survives and is raised by wild animals, or by humans who live on the margin of wild: shepherds, woodsmen, gamekeepers, and the like. When the child grows up, his or her true identity is revealed and the prophesy is fulfilled. In Persian legends surrounding Cyrus the Great, for example, it is prophesized at his birth that he will grow up to take the crown of his grandfather, the King of Media. The king orders the baby killed and Cyrus is left on a wild mountainside, where he's rescued either by the royal herdsman or a bandit (depending on the version of the tale) and raised in safety. He grows up, learns his true parentage, and not only captures the Median throne but goes on to conquer most of central and southeast Asia. In Assyrian myth, a fish-goddess falls in love with a beautiful young man, gives birth to a half-mortal daughter, abandons the child in the wilderness, and then kills herself in shame. The baby is fed by doves and survives to be found and raised by a royal shepherd...and grows up to become Semiramis, the great Warrior Queen of Assyria. In Greek myth, Paris, the son of King Priam, is born under a prophesy that he will one day cause the downfall of Troy. The baby is left on the side of Mount Ida, but he's suckled by a bear and manages to live -- growing up to fall in love with Helen of Troy and spark the Trojan War.

fate intervenes, the child survives and is raised by wild animals, or by humans who live on the margin of wild: shepherds, woodsmen, gamekeepers, and the like. When the child grows up, his or her true identity is revealed and the prophesy is fulfilled. In Persian legends surrounding Cyrus the Great, for example, it is prophesized at his birth that he will grow up to take the crown of his grandfather, the King of Media. The king orders the baby killed and Cyrus is left on a wild mountainside, where he's rescued either by the royal herdsman or a bandit (depending on the version of the tale) and raised in safety. He grows up, learns his true parentage, and not only captures the Median throne but goes on to conquer most of central and southeast Asia. In Assyrian myth, a fish-goddess falls in love with a beautiful young man, gives birth to a half-mortal daughter, abandons the child in the wilderness, and then kills herself in shame. The baby is fed by doves and survives to be found and raised by a royal shepherd...and grows up to become Semiramis, the great Warrior Queen of Assyria. In Greek myth, Paris, the son of King Priam, is born under a prophesy that he will one day cause the downfall of Troy. The baby is left on the side of Mount Ida, but he's suckled by a bear and manages to live -- growing up to fall in love with Helen of Troy and spark the Trojan War.

From Roman myth comes one of the most famous babes-in-the-wood stories of all, the legend of Remus and Romulus. Numitor, the good King of Alba Long, is overthrown by Amulius, his wicked brother, and his daughter is forced to become a Vestal Virgin in order to end his line. Though locked in a temple, the girl becomes pregnant (with the help of

Mars, the god of war) and gives birth to a beautiful pair of sons: Remus and Romulus. Amulius has the twins exposed on the banks of the Tiber, expecting them to perish; instead,  they are suckled and fed by a wolf and a woodpecker, and survive in the woods. Adopted by a shepherd and his wife, they grow up into noble, courageous

they are suckled and fed by a wolf and a woodpecker, and survive in the woods. Adopted by a shepherd and his wife, they grow up into noble, courageous

young men and discover their true heritage — whereupon they overthrow

their great-uncle, restore their grandfather to his throne, and,

just for good measure, go on to found the city of Rome.

In Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children, Michael Newton

delves into the mythic symbolism inherent in the moment when abandoned

children are saved by birds or animals. "Restorations and

substitutions are at the very heart of the Romulus and Remus story," he

writes; "brothers take the rightful place of others, foster parents

bring up other people's children,

the god Mars stands in for a human suitor. Yet the crucial

substitution occurs when the she-wolf saves the lost children. In that

moment, when the infants' lips

close upon the she-wolf's teats, a transgressive mercy removes the

harmful influence of a murderous culture. The moment is a second birth:

where death is expected, succor is given, and the children are

miraculously born into the order of nature. Nature's mercy admonishes

humanity's unnatural cruelty: only a miracle of kindness can restore the

imbalance created by human iniquity."

In myth, when we're presented with children orphaned, abandoned, or raised by

animals, it's generally a sign that their true parentage is a

remarkable one and they'll grow up to be great leaders, warriors, seers,

magicians, or shamans. As they grow, their beauty, or physical prowess

or magical abilities betray a lineage that cannot be hidden by their

humble upbringing. (Rarely do we encounter a mythic hero whose origins are

truly low; at least one parent must be revealed as noble, supernatural,

or divine.)

After a birth trauma and a miraculous survival always comes a span

of time symbolically described as "exile in the wilderness," where they

hone their skills, test their mettle, and gather their armies, their

allies, or their magic, before returning (as they always do) to the

world that is their birthright.

When we turn to folk tales and fairy tales, however, although we also find stories of

children abandoned in the wild and befriended by animals, the

tone and intent of such tales is markedly different. Here, we're not concerned with the affairs of the gods

or with heroes who conquer continents -- for folk tales in the Western tradition, unlike myths and hero epics, were passed

through the centuries primarily by storytellers of lower classes (usually women), and tended to be focused on themes more relevant to ordinary people. Abandoned children in fairy tales (like Hansel and Gretel, Little Thumbling, or the broommaker's twins in The Two Brothers) aren't destined for greatness or infamy; they are

exactly what they appear to be: the children of cruel or feckless

parents. Such parents exist, they have always existed, and fairy tales

did not gloss over these dark facts of life. Indeed, they

confronted them squarely. The heroism of such children lies not in the recovery of a noble lineage but in

the ability to survive and transform their fate -- and to outwit those

who would do them harm without losing their lives, their souls, or their

humanity in the process.

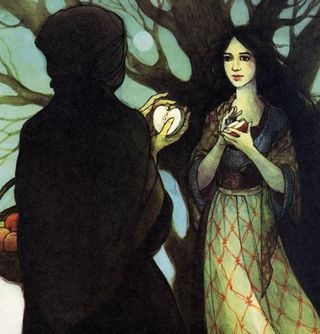

Children also journey to the forest of their own accord, but usually in response to the actions of adults: they enter the woods at a parent's behest (Little Red Riding Hood), or because they're not truly wanted at home (Hans My Hedgehog), or in order to flee a wicked parent, step-parent, or guardian (Seven Swans, Snow White and Brother & Sister). Disruption of a safe, secure home life often comes in the form a parent's remarriage: the child's mother has died and a heartless, jealous step-mother has taken her place. The evil step-mother is so common in fairy tales that she has become

an iconic figure (to the bane of real step-mothers everywhere), and her

history in the fairy tale canon is an interesting one. In some tales,

she didn't originally exist. The murderous queen of Snow White, for example, was the girl's own mother in the oldest versions of the story (the Brothers Grimm changed her into a step-parent in the 19th century) -- whereas other stories, such as Cinderella and The Juniper Tree, have featured second wives since their earliest known tellings.

Some scholars who view fairy tales in psychological terms (most notably Bruno Bettelheim in The Uses of Enchantment)

Some scholars who view fairy tales in psychological terms (most notably Bruno Bettelheim in The Uses of Enchantment)

believe that the "good mother" and "bad step-mother" symbolize two

sides of a child's own mother: the part they love and the part they

hate. Casting the "bad mother" as a separate figure, they say, allows

the child to more safely identify such socially unacceptable feelings.

While this may be true, it ignores the fact that fairy tales were

not originally stories specially intended for children. And, as Marina

Warner points out (in From the Beast to the Blonde), this "leeches the history out of fairy tales. Fairy

or wonder tales, however farfetched the incidents they include, or

fantastic the enchantments they concoct, take on the color of the actual

circumstance in which they were or are told. While certain structural

elements remain, variant versions of the same story often reveal the

particular conditions of the society

in which it is told and retold in this form. The absent mother can

be read as literally that: a feature of the family before our modern

era, when death in childbirth was the most common cause of female

mortality, and surviving orphans would find themselves brought up by

their mother's successor."

We rarely find step-fathers in fairy tales, wicked or otherwise, but

the fathers themselves can be treacherous. In stories like Donkeyskin, Allerleirauh, or The Handless Maiden, it is a cowardly, cruel, or incestuous father who forces his daughter to flee to the wild. Even those fathers portrayed more sympathetically as the dupes of their black-hearted wives are still somewhat suspect: they are happy at the story's end to have their children return unscathed, but are curiously powerless or unwilling to protect them in the first place. Though the father is largely absent from tales such as Cinderella, The Seven Swans, and Snow White, the shadow he casts over them is a large one. He is, as Angela Carter has pointed out, "the unmoved mover, the unseen organizing principle. Without the absent

father there would have been no story because there would have been no

conflict."

Family upheaval has another function in these tales, beyond reflecting real issues encountered in life: it propels young heroes out of their homes, away from all that is safe and familiar; it forces them onto the uknown road to the dark of the forest. It's a road that will lead, after certain

tests and trials, to personal and worldly transformation,

pushing the hero past childhood and pointing the way to a re-balanced life -- symbolized by new prosperity, or a family home that has been restored, or (for older youths) a wedding feast at the end of the tale. These young people are "wild" only for a time: it's a liminal state, a rite-of-passage that moves the hero from one distinct phase of life to another. The forest, with all its wonders and terrors, is not the final destination. It is a place to hide, to be tested, to mature. To grow in strength, wisdom, and/or power. And to gain the tools needed to return to the human world and repair what's been broken...or build anew.

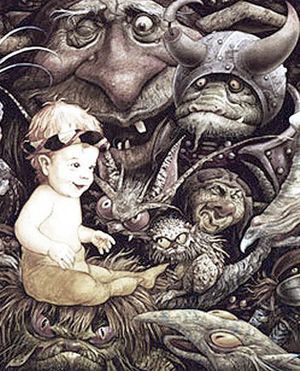

In one set of folk tales, however, children who disappear into the woods do not often return: the "changeling" stories of babies (and older children) stolen by faeries, goblins, and trolls. Why, we might ask, are the denizens of Faerie so interested in stealing the offspring of mortals? Some faery lore suggests that the children are

destined for lives as servants or slaves of the Faerie court; or that they are kept, in the manner of

pets, for the amusement of their faery masters. Other stories and ballads (Tam Lin, for example) speak of a darker purpose: that the faeries

must pay a tithe of blood to the Devil every seven years,

and prefer to pay with mortal blood rather than blood of their own.

In other traditions, however, it's simply the beauty of the children that

attracts the faeries, who are also known to kidnap pretty young men and women, artists, poets, and

musicians.

The ability of faeries to procreate is a debatable issue in faery lore. Some stories maintain that the faeries do procreate, though

The ability of faeries to procreate is a debatable issue in faery lore. Some stories maintain that the faeries do procreate, though

not as often as humans. By occasionally interbreeding with mortals and

claiming mortal babes as their own,

they bring new blood into the Faerie Realm and keep their bloodlines

strong. Other tales suggest that they cannot breed, or do so with such

rarity that jealousy of human fertility is the motive behind

child-theft.

Some stolen children, the tales tell us, will spend their

whole lives in the Faerie Realm, and may even find happiness there, losing all

desire for the lands of men. Other tales tell us that human children

cannot thrive in the otherworld, and eventually sicken and die for want

of mortal food and drink. Some faeries maintain their interest in child

captives only during their infancy, tossing the children out of the Faerie Realm when they show signs of age.

Such children, restored to the human world, are not always happy

among their own kind, and spend their mortal lives pining for a way to

return to Faerie.

Another type of story that comes from the deep, dark forest is the Feral Child tale, found in the shadow realm that lies between legend and fact. There have been a number of cases throughout history of young

children discovered living in the wild, a few of which have been documented

to a greater or lesser degree. Generally, these seem to be children who

have been abandoned or fled abusive homes, often at such a young

age that they've ceased to remember any other way of life. Attempts to "civilize"

these children, to teach them language,

and to curb their animal-like behaviors, are rarely entirely

successful -- which leads to all sorts of questions about what it is that

shapes human culturalization as we know it.

One of the most famous of these children was Victor, the Wild Boy

of Avignon, discovered on a mountainside in France in the early 19th

century. His teacher, Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard, wrote an extraordinary

account of his six years with the boy -- a document which inspired François Truffaut's film The Wild Child, and Mordicai Gerstein's wonderful novel The Wild Boy. In an essay for The Horn Book, Gerstein wrote: "Itard's reports not only provide the best

documentation

we have of a feral child, but also one of the most thoughtful,

beautifully written, and moving accounts of a teacher pupil

relationship, which has as its object nothing less than learning to be a

human being (or at least what Itard, as a man of his time, thought a

human being to be).... Itard's ambition to have Victor speak

ultimately failed, but even if he had succeeded, he could never know

Victor better or be more truly, deeply engaged with him than those

evenings, early on, when they sat together as Victor loved to,

with the boy's face buried in the man's hands. But the more Itard

taught Victor, the more civilized he became, the more the distance

between them grew." (You'll find Gerstein's full essay here; scroll to the bottom of the page.)

In India in the 1920s two small girls were discovered living in the

wild among a pack of wolves. They were captured (their "wolf mother"

shot) and taken into an orphanage run by a missionary, Reverend Joseph

Singh. Singh attempted to teach the girls to speak, walk upright, and

behave like humans, not as wolves — with limited success. His diaries make for fascinating (and horrifying) reading. Several works of fiction were inspired by this story, but the ones I particularly recommend are Children of the Wolf, a poignant children's novel by Jane Yolen, and "St. Lucy's Home for Girls Raised by Wolves," a wonderful short story by Karen Russell (published in her collection of the same title). Also, Second Nature by Alice Hoffman is an excellent contemporary novel on the Feral Child theme.

More recently, in 1996, an urban Feral Child was discovered

living with a pack of dogs on the streets of Moscow. He resisted capture

until the police finally separated the boy from his pack. "He had been

living on the street for two years," writes Michael Newton. "Yet, as he

had spent four years with a human family [before this], he could talk

perfectly well. After a brief spell in a Reutov children's shelter, Ivan

started school. He appears to be just like any other Moscow child. Yet

it is said that, at night, he still dreams of dogs."

When we read about such things as adults and parents, the thought

of a child with no family but wolves or dogs is a deeply disturbing

one. . .but when we read from a child's point of view, there is

something secretly thrilling about the idea of life lived among an

animal pack, or shedding the strictures of civilization to head into the

woods. In this, of course, lies the enduring appeal of stories like

Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book and Edgar Rice Burroughs's Tarzan of the Apes.

Explaining his youthful passion for such tales,

Mordecai Gerstein writes: "The heart of my fantasy was leaving the

human world for a kind of jungle Eden where all one needed was readily

available and that had, in Kipling's version, less hypocrisy, more

nobility. I liked best the idea of being protected from potential

enemies by powerful animal friends."

And here we begin to approach another aspect of Wild Child (and Orphaned Hero) tales

that makes them so alluring to many young readers: the idea that a parentless life in the wild might be a better, or a more exciting, one. For

children with difficult childhoods, the appeal of running away to the forest is obvious: such stories

provide escape, a vision of life beyond the confines of a troubled home.

But even children from healthy families need fictional escape from time to

time. In the wild, they can shed their usual roles

(the eldest daughter, middle son, the baby of the family, etc.)

and enter other realms in which they are solitary actors. Without

adults to guide them (or, contrarily, to restrict them), these young heroes

are thrown back, time and time again, on their own resources. They must

think, speak, act for themselves. They have no parental safety net

below. This can be a frightening prospect, but it is also a liberating

one — for although there's no one to catch them if they fall, there's no

one to scold them for it either.

J.M. Barrie addresses this theme, of course, in his much-loved children's fantasy Peter Pan -- which draws upon themes from Scottish changling legends, twisted into interesting new shapes. Barrie's Peter is human-born, not a faery, but he's lived in Never Land so long

that he's as much a faery as he is a boy: magical, capricious and

amoral. He's a complex

mixture of good and bad, with little understanding of the difference

between them -- both cruel and kind, thoughtless and generous, arrogant

and tender-hearted, bloodthirsty and sentimental. This dual nature makes Peter Pan a classic

trickster character (kin to Puck, Robin Goodfellow, and other

delightful but exasperating sprites of faery lore): both faery and child, mortal and

immortal, villain (when he lures children from their homes) and hero

(when he rescues them from pirates).

Peter's last name derives from the Greek god Pan, the son of the

Peter's last name derives from the Greek god Pan, the son of the

trickster god Hermes by a wood nymph of Arcadia. Pan is a creature of

the wilderness, associated with vitality, virility, and ceaseless

energy. Like Peter, the god Pan is a contradictory figure. He haunts

solitary mountains and groves, where he's quick to anger if he's

disturbed, but he also loves company, music, dancing, and riotous

celebrations. He is the leader of a woodland band of satyrs — but these

"Lost Boys" are a wilder crew than Peter's, famed for drunkenness,

licentiousness, and creating havoc (or "panic"). Pan himself is a

distinctly lusty god — and here the comparison must end, for Peter's

wildness has no sexual edge. Indeed, it's sex and the other mysteries of

adulthood that he's specifically determined to avoid. ("You mustn't

touch me. No one must ever touch me," Peter tells Wendy.)

Although Peter Pan makes a brief appearance in Barrie's 1902 novel The Little White Bird, his story as we know it now really began as a children's play, which debuted on the London stage in 1904. The playscript was subsequently published under the title Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up; and eventually Barrie novelized the story in the book Peter and Wendy. (It's a wonderful read in Barrie's original text, full of sharp black humor.) Peter and Wendy ends with a poignant scene that does not exist in the play: Peter comes back

to Wendy's window years later, and discovers she is all grown up. The

little girl in the nursery now is Wendy's own daughter, Jane. The girl

examines Peter with interest, and soon she's off to Never Land herself...where Wendy can no longer go, no matter how much she longs to

follow.

The fairy tale forest, like Never Land, is not a place we are meant to remain, lest, like Peter or the children stolen by faeries, we become something not quite human. Young heroes return triumphant from the woods (trials completed, curses broken, siblings saved, pockets stuffed with treasure), but the blunt fact is that they must return. In the old tales, there is no sadness in this, no lingering, backward glance to the forest; the stories end "happily ever after" with the children restored to the human world. In this sense, the wild depths of the wood represent the realm of childhood itself, and the final destination is an adulthood rich in love, prosperity, and joy. From Victorian times onward, however, a new note of regret creeps in at the end of the story. A theme that we find over and over again in Victorian fantasy literature is that magic and wonder are accessible only

to children, lost on the threshold of adulthood. From Lewis

Carroll’s "Alice" books to J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, these

writers grieved that their wise young heroes would one day grow up and leave the woods behind.

Of course, many of us never do leave the woods behind: we return through the pages of magical books and we return in actuality, treasuring our interactions with the wild world through all the years of our lives. But that part of the forest specific to childhood does not truly belong to us now -- and that's exactly as it should be. Each generation bequeaths it to the next. Our job as adults, as I see it, is to protect that enchanted place by preserving wilderness and stories both. Our job is to open the window at night and to watch from the shadows as Peter arrives; it's our children's turn to step over the sill. Our job is to teach them to navigate by the stars and to bless them on their way.

Barrie was wrong, by the way, for we adults have our owns forms of magic too, and the wild wood still welcomes us. But it's right, I think, that there should be a corner of it forever marked "Grown-ups, keep out!" Where children are heroes of their own stories, kings and queens of their own wild worlds.

The art above is: "The Miracle of Tears" by Sulamith Wulfing (Germany); "Moses in the Bulrushes," artist unknown; "Remus and Romulus," an Ertruscan bronze; "Wolf Mama" and "Starchild" by Susan Seddon-Boulet (England/Brazil/USA); "Hansel & Gretel" by Kay Nielsen (Denmark); "Little Red Cap" by Lisbeth Zwerger (Austria); "Snow White" by Trina Schart Hyman (USA); Donkeyskin by Anneclaire Macé (France); "Three Black Dogs" by Kelly Louise Judd (USA), "Baby Stolen by Gobins" by Maurice Sendak (USA); "Toby and the Goblins" by Brian Froud (UK); a still from the film "L'Enfant sauvage" by François Truffaut (France); "Tiger Girls by Fay Ku (Tawain/USA); a photograph from the "Ashes and Snow" series by Gregory Colbert (Canada); "Mowgli" by Edward Julius Detmold (UK); "Where the Wild Things Are" by Maurice Sendak (USA); "Peter Pan" by David Wyatt (UK); "Peter Pan" by Brian Froud (UK); "Peter Pan at the Window" by F.D. Beford (UK); an illustration by Robert Ingapen (Australia); and "Peter Pan" by Charles Buchel (Germany/England).

Parts of this post have been drawn from these articles: The Orphaned Hero, Changelings, Peter Pan.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 712 followers