Loren C. Steffy's Blog, page 12

July 25, 2014

A Post-Chronicle memory

I still have the clip of my first Post column from 1985. Sorry, folks, there were no links in those days.

In a post on her Gray Matters site, the Houston Chronicle’s Lisa Gray has used the announcement that the paper is moving to the old Houston Post building to collect memories about the Post from former staffers and others. I have never set foot in that building, but I will always be grateful to those who did.

Lisa’s post includes a comment from me that the Post was the first professional paper to publish my columns. There’s a little more to the story. In mid-1985, I was writing a column and editing the opinion page for The Battlation, the student newspaper at Texas A&M. One of my professors (Don Sneed, for any former Batt-ratts reading this) got an op-ed published in the Post and the editor, Charles Rankin, mentioned that the Post was always on the lookout for younger voices to put on the opinion pages. The professor suggested I send them something.

So I mailed a dot-matrix printout of a column I wrote about some controversy involving the Doonesbury cartoon strip. The Post not only published it, they paid me $50.

From then on, I would send the Post pieces from time to time, and over the next couple of years I probably had a dozen or so that appeared in print. I tried something similar with the Chronicle, but it didn’t pay for op-eds, so I focused on the Post. Some of my columns even generated responses from readers in Houston.

I had hoped to parlay the opportunity into an editorial internship that the Post offered under Lynn Ashby, but my wife got an internship for her master’s working Dallas. So we moved there and I became a business writer. But I will always be grateful to the Post for giving me my first taste of big city journalism.

July 24, 2014

Why `Wolf’ List Shouldn’t Be Released

[Photo: Flickr]

My former colleague Susan Antilla had a nice piece in the New York Times recently on a judge’s decision to keep confidential the list of victims preyed upon by Jordan Belfort, the self-proclaimed “Wolf of Wall Street.” A TV news magazine had requested the judge release the name of Belfort’s 1,300 victims.As Antilla reported:

The potential harm that could come from releasing the list to the public is “substantial,” wrote Judge John Gleeson of Federal District Court in Brooklyn, citing the danger of “sucker lists” coveted by fraudsters on the prowl for easy marks.

It’s good to see a federal judge recognizing the public harm that could be caused by releasing this information. As Antilla points out, these “sucker lists” are highly valued by other scammers. While it may defy common sense, the fact is that someone who’s been cheated once is more likely to fall victim again. The crooks know it, and they covet these lists.

Belfort, of course, has turned the whole world into his sucker list, having written a best-selling book about his schemes and then conning Hollywood into glorifying it in film. Belfort has done little to repay the victims on the list. As Gleeson pointed out, releasing their names would only compound their insult and injury.

Unfortunately, the issue of selling or releasing sucker lists isn’t unique to Belfort’s case. The issue is far more common in bankruptcy cases, and many bankruptcy judge’s don’t share Gleeson’s views. In a bankruptcy, the judge is obligated to maximize the recovery for the estate, and often the “mullet list” is the only asset of value remaining when a scam company goes bankrupt. I wrote about a lot of oil and gas boiler rooms in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and I was amazed at how often a company would file for bankruptcy and sell its sucker list to another company, often founded by many of the same scammers who would then target the same victims.

Too often, we want to dismiss the victims of investment scams as gullible or ignorant, but con men know how to play our emotions against us. I once wrote about a Dallas con man who conned the prosecuting attorney who had sent him to prison for securities fraud years earlier. When I asked the attorney how he could have invested with someone he knew was so dishonest, he said he thought the con man had reformed.

The point is that everyone is vulnerable. In fact, the more sure you are you won’t get conned, the more vulnerable you are. The con men will pick up on that certainty and use it against you. Financial frauds, after all, are designed to separate you from your money. All the more reason that lists like Belfort’s need to remain locked away.

July 7, 2014

‘Watershed moment’ for fracking foes? h

Taking Oil Industry Cue, Environmentalis

May 27, 2014

A Two-fer in Texas Monthly

I have two stories in the June issue of Texas Monthly. In my regular column, I take a look at the burgeoning business of liquefied natural gas exports and how Texas, which helped pioneer the process of hydraulic fracturing, is now leading the way on the next phase of the natural gas boom — exporting production to countries in Asia and Europe. Here’s a sample:

I have two stories in the June issue of Texas Monthly. In my regular column, I take a look at the burgeoning business of liquefied natural gas exports and how Texas, which helped pioneer the process of hydraulic fracturing, is now leading the way on the next phase of the natural gas boom — exporting production to countries in Asia and Europe. Here’s a sample:

Four years ago, things looked bleak for Houston’s Cheniere Energy. It had about $3 billion in debt, its stock price had plunged from more than $40 to less than $1 in a year’s time, and bankruptcy seemed imminent. Cheniere had made one of the biggest wrong-way bets in the history of natural gas, a commodity that is the poster child for wrong-way bets. With America’s natural gas supplies growing thin, Cheniere built a massive terminal in Sabine Pass, just across the border in Louisiana, to import liquefied natural gas (LNG). But by the time it completed the project, the hydraulic fracturing boom had changed everything. U.S. gas production was soaring. The idea of importing the stuff suddenly looked like a Texas twist on the British idiom of carrying coals to Newcastle.

Cheniere’s response: take advantage of the fracking boom by betting billions more on revamping its terminal and sending the gas the other way—which turned out to be a right-way bet. In May 2011 Cheniere became the first company in the country to get a permit from the Department of Energy to export LNG to countries in Asia. More precisely, Cheniere’s customers will bring natural gas to the Sabine Pass facility, which Cheniere will turn into LNG and pump onto customers’ ships that are bound for overseas markets.

Cheniere isn’t alone. Freeport LNG, also based in Houston, has been on the same roller coaster. It too got burned by investing a billion dollars in an import facility, on Quintana Island, just down the coast from Galveston.

I also wrote about the Securities and Exchange Commission’s insider trading case against Dallas billionaire Sam Wyly. It was a must-win case for the SEC, especially after it lost a similar one against another Dallas billionaire. As I explain in the story:

The SEC can’t afford to lose. For years, the commission had a practice of allowing defendants to pay a fine without admitting wrongdoing. It was, from the perspective of some prosecutors and defendants, a win-win solution: the government got to collect hefty fines without risking embarrassing and expensive losses in the courtroom, and defendants got to save face by merely paying a fine that most of them could handily afford. But in 2009 a federal judge in New York balked at such an arrangement in a settlement of claims that Bank of America had misled shareholders about $5.8 billion paid to Merrill Lynch employees. He referred to the SEC’s practice as “a contrivance designed to provide the SEC with the facade of enforcement.” Two years later, the same judge refused to sign off on a similar deal with Citigroup. After that, the SEC decided to stop making such deals. And the defendants started lawyering up and fighting back, with results that the New York judge may not have expected.

May 19, 2014

The Return of the Charles W. Morgan

The Charles W. Morgan at Mystic Seaport. (Photo: Mystic Seaport)

As a child, I spent a lot of time at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Conn. As I discuss in The Man Who Thought Like a Ship, it was among my father’s favorite maritime museums, and we often stopped there as part our summer vacation. Before he got into nautical archaeology, my father’s dream was to volunteer at the museum once he retired.

Among other things, the museum housed the ship model collection of Charles G. Davis, whose books on built-up ship modeling techniques inspired my father’s own early work with models.

My dad also used to take pictures of the rigging of old sailing ships, and he probably photographed the rigging of the Charles W. Morgan more than any other ship. The Charles W. Morgan is the museum’s showcase and the oldest whaling ship still in existence. As a child, I spent hours running around her decks.

She was towed into Mystic in 1941, and she’s basically been there ever since. This summer, however, the Charles W. Morgan will set sail for the first time in more than 90 years. Fresh off a five-year renovation program, the museum is sending the her on a victory lap, of sorts that will take her to her former home port of New Bedford, Mass., as well as Boston, where she’ll be berthed next to the U.S.S. Constitution.

Smithsonian.com has more on the Charles W. Morgan’s “38th Voyage.”

April 29, 2014

How NRG capitalized on Energy Future Hol

How NRG capitalized on Energy Future Holdings’ financial woes http://ow.ly/whzRh #energy #deregulation

April 26, 2014

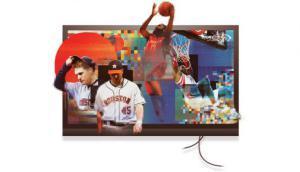

Why it’s hard to find an Astros game on TV

Illustration by Nigel Evan Dennis

This month’s Texas Monthly column discusses the bankrupt cable network Comcast SportsNet Houston and what its failure means for the Astros, the Rockets and the Dynamo. With the Rockets in the playoffs and the Astros rebuilding, can the teams find a way to solve the network’s financial problems and get their games in front of a wider audience?

Imagine there was a professional baseball team and only half its fans could see it win. Would the games still matter? For the Houston Astros, the worst team in baseball the past three years, the question has been moot so far—there have been precious few victories to witness. This season, though, fans may have more reason to watch. Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan is back with the team, as an executive adviser, and ESPN has declared the Astros’ rebuilt farm system the best in baseball. But finding an Astros game on a TV in Houston will be very difficult.

Comcast SportsNet Houston (CSN Houston), the network with the exclusive rights to broadcast Astros games, is in Chapter 11, and its three owners—the Astros (with a 46.5 percent stake), the Houston Rockets (31 percent), and the cable giant Comcast (22.5 percent)—are bickering over what to do next. Comcast plunged the year-old network into bankruptcy proceedings last fall after failing to shoehorn it into the lineups of providers such as DirecTV, Dish, and Time Warner, which are tired of jacking up the rates they charge to subscribers to pay for ever-more-specialized networks. As a result, Comcast itself is the only major provider that carries CSN Houston, meaning Astros and Rockets games—and Houston Dynamo soccer games—appear in just 40 percent of households with cable or satellite in the greater Houston area. “Both the Astros and the Rockets used to be staples in my home,” says Joseph Theis, a Houston restaurant owner and DirecTV subscriber. “Now they’re really not a part of my life.”

In many major markets, regional sports networks are the new profit centers for team owners, who are always looking to wring more revenue from their franchises. The Los Angeles Angels, for instance, signed a seventeen-year deal with Fox that brings in an average of $95 million in rights fees annually for the team. But without Time Warner and its brethren on board, CSN Houston found it couldn’t afford the Astros’ and Rockets’ licensing fees. And so, in late September, Comcast turned to bankruptcy court to preserve what little value was left in the network. The Astros immediately opposed the filing and have vowed to thwart any attempts to reorganize CSN Houston. The Rockets, by contrast, supported the bankruptcy and, given their status as a possible playoff contender, are eager to get the issue resolved.

April 15, 2014

Hamm and exports: the rhetoric and the r

Hamm and exports: the rhetoric and the reality. http://ow.ly/vO1CF With a side of Hess. My latest for BIC magazine. #energy

March 28, 2014

Fire Fight: Houston’s pension battle heats up

My column in the latest issue of Texas Monthly discusses the battle between Houston Mayor Annise Parker and the Houston Firefighters’ Relief and Retirement Fund. Parker has sued the pension fund twice, seeking to give the city more say over the contributions it’s required to make. The pension, though, has little incentive to come to the bargaining table.

My column in the latest issue of Texas Monthly discusses the battle between Houston Mayor Annise Parker and the Houston Firefighters’ Relief and Retirement Fund. Parker has sued the pension fund twice, seeking to give the city more say over the contributions it’s required to make. The pension, though, has little incentive to come to the bargaining table.

The offices of the Houston Firefighters’ Relief and Retirement Fund are nestled in a wooded enclave near the George Bush Intercontinental Airport. On a cold, wet morning in early February, behind the glass doors and the blond-brick facade, the building offered refuge from the harsh reality outside. For more than 6,500 active firefighters and retirees, the HFRRF itself does exactly that, providing protection against forces that want to reduce their retirement benefits. And recently those forces—once relegated to the realm of argument and public pressure—have turned to a full-scale legal assault.

In January Mayor Annise Parker brought suit against the fund, seeking changes to a thirties-era state law that has left the city powerless to control the amount it must contribute to the firefighters’ retirement. The suit is the second in as many years, and Todd Clark, the fund’s chairman, says he has no intention of bending to Parker’s demands. Sitting in the HFRRF’s second-floor boardroom, Clark dismisses the lawsuits as a political vendetta against the firefighters, who supported Parker’s opponents in the past three elections. He claims that she wants to gain control of the pension and slash its benefits to pay for other city programs. “We’re being attacked by this mayor, and we’ve been attacked since day one,” he says. For her part, Parker claims that she simply wants to have a say in how much the city commits to retirees.

While Houston is faring better than many other cities, it is, like cash-strapped municipalities across the country, confronting an ugly truth: thanks to rising health care expenses and longer life spans, cities are finding it difficult, if not impossible, to afford the open-ended promises made to workers in years past. Pensions like the $3.7 billion managed by the HFRRF are an anachronism in the modern American workplace, where cheaper, “self-directed” retirement plans such as 401(k)s tend to dominate, at least in the private sector. Houston’s firefighters have a defined-benefit plan, which means the fund must pay for employees’ retirement benefits for as long as they live, regardless of the actual cost.

Generous public-sector pension plans have endured because city leaders have realized that boosting retirement benefits is a lot easier than raising salaries. Raises, after all, come out of the current budget. Pensions don’t have to be paid for decades—long after the current leaders are out of office. “It’s just a complete abdication of responsibility,” says Shad Rowe, a Dallas investment manager and a former member of the state’s Pension Review Board. “It isn’t a problem that gets better as you ignore it.”