Loren C. Steffy's Blog, page 10

February 4, 2015

What’s Happening With Oil Prices?

That’s a question a lot of people are asking these days. Crude prices have tumbled more than 50 percent since last summer, and we now seem to be in the teeth of a full-scale oil bust. Last week, I talked about the industry and economic implications of oil prices with Straight Talk Money host Mike Robertson.

You can listen to the full interview here.��

January 29, 2015

Oil’s Well That Ends Well?

Perhaps not so much. These days, Texans are getting worried about what the plunge in oil prices in the past six months will mean for the economy. We’ve seen this before, of course, in the 1980s. In the latest issue of Texas Monthly, I compare then and now:

Perhaps not so much. These days, Texans are getting worried about what the plunge in oil prices in the past six months will mean for the economy. We’ve seen this before, of course, in the 1980s. In the latest issue of Texas Monthly, I compare then and now:

Late last June, the price of a barrel of oil, which stood at $108, began to slide. By July 14 it had dropped to $102. By August 19 it had reached $94. But it wasn���t until autumn, when West Texas Intermediate crude���the benchmark for U.S. oil prices���slid below $90, that producers and investors began to worry. The price kept slipping. On November 26, it stood at a measly $74. Then, a day later, on Thanksgiving, OPEC announced that, contrary to the hopes of many, it would do nothing to cut production. Oil went into a tailspin. By early January, the price of a barrel had sunk to $48, less than half of what it sold for just six months earlier.

That���s the sort of precipitous decline that changes everything���hiring practices, driving habits, consumer purchasing decisions. As if on cue, oil companies slashed jobs and drilling budgets. Permits for new wells fell 50 percent in November from the previous month. Bloomberg News wrote of a coming oil ���storm.��� But in Texas, people were thinking of another word that still sends chills down spines from Kilgore to the Permian Basin: bust.

It���s been almost thirty years since Texas has experienced a boom-bust cycle as extreme as this one. Sure, in the late nineties oil dropped below $11 a barrel, touching off a string of mega-mergers that brought us the likes of ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips. And in 2008 the global recession caused oil to plunge from $145 a barrel to less than $40 in six months. But those busts weren���t preceded by frenetic, dancing-in-the-gusher booms.

The best parallel to what���s happening now is the boom and bust of the eighties. At the beginning of the decade, Texas loomed large in America���s response to the OPEC oil embargoes that had panicked the country during the seventies. Never again, we vowed, would people line up at gas stations in the wee hours hoping to get a tankful before the stuff ran out.

December 22, 2014

Get Uber It

In almost every city it’s entered, the car-hailing service Uber has met with controversy. One of the few exceptions has been Lubbock, and in the latest issue of Texas Monthly, I explain why:

Last February, after Uber, the app-based ride-sharing company, announced its intention to enter the Houston market, local cab drivers crammed into a city council meeting wearing bright-yellow T-shirts with slogans like “Fair Play = Same Rules.” They claimed that Uber, which usually charges less than traditional cabs do, has an advantage because its drivers don’t have to meet the same insurance requirements as most cabbies. By the time the city council granted Uber the right to operate, last summer, the debate had raged for months, and local cab companies had sued Uber and its rival, Lyft. Uber has faced a similar backlash in Dallas, where the city has yet to finalize new ride-sharing rules.

On the High Plains, though, things have been a lot quieter, as usual. Uber began serving Lubbock in June, and its arrival garnered little controversy. That’s largely because Uber arrived just as the city’s only traditional cab service was winding down operations; Jim Sexton, the owner of the town’s decades-old Yellow Cab Company, had decided to retire, and no new buyer had emerged. But it certainly didn’t hurt Uber’s chances that the city also has a ready-made market for its service: thousands of smartphone-wielding Texas Tech students.

December 20, 2014

A Glimpse of Life at Sea, Circa 1943

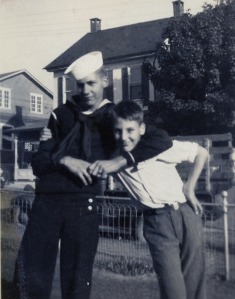

I’m excited about a new project I’ve just unveiled on my website – a page devoted to World War II photos my father took during his time in the Navy. I got the idea around Veteran’s Day, when many of my friends posted pictures on social media of family members who served. That sent me digging through my photo archives for a shot of my dad — shown here with his brother Milt, who also later joined the Navy.

I’m excited about a new project I’ve just unveiled on my website – a page devoted to World War II photos my father took during his time in the Navy. I got the idea around Veteran’s Day, when many of my friends posted pictures on social media of family members who served. That sent me digging through my photo archives for a shot of my dad — shown here with his brother Milt, who also later joined the Navy.

In looking for that picture, I found dozens of others that I had scanned when I was researching my book The Man Who Thought Like a Ship. In January 1943, my father, J. Richard Steffy, was assigned as an electrician’s mate to the USS Wyffels, DE6, a new Evarts-class destroyer escort. After a brief shakedown cruise off Bermuda, the Wyffels and her crew of 198 were assigned to the Sixth Fleet in the North Atlantic. In all, the Wyffels made 11 crossings of the Atlantic during World War II.

My father rarely talked about his time in the Navy, and he didn’t keep in touch with his shipmates. After his death in 2007, I found hundreds of these photos he’d taken during his deployment. Some of them were beginning to deteriorate, and I began the scanning project in hopes of preserving them. I found myself looking at them from time to time, wondering who the men where, how well my father knew them and what their shared experiences may have been. The Wyffels saw little combat, something for which my father was always thankful, and as a result, most of the photos capture the mundane duties and pastimes of life aboard ship.

I haven’t retouched any of the pictures, and I’ve labeled them as my father did — except, of course, for the ones that have no descriptions at all. In some cases, you can see my father’s handwriting on the margins. Citation Solutions’ Margie Seaman — who’s appropriately named for this project — put the page together and organized the photos. You can click on each one to enlarge it.

I still have many more photos to scan, so I hope to update the page periodically as I get more done. I’ll continue to share them on the website in hopes that others may enjoy seeing a glimpse of day to day life at sea during World War II.

November 29, 2014

The Passing of Nelson Bunker Hunt

Dallas’ Thanksgiving Tower, once home to the Hunt empire and the Petroleum Club

I moved to the Dallas area and became a business writer in the late 1980s, so I missed the oil boom of the early 1980s and the swagger that came with it. No one personified the audacity of the era more than Nelson Bunker Hunt and his brothers. Heir to one of the world’s great oil fortunes, Hunt died on Oct. 21 at the age of 88. My obituary of Hunt appears in the latest Texas Monthly.

By the time I got to the Dallas Times Herald, the Hunts were in bankruptcy, and the boom had turned to bust, serving as a referendum on the free-spending excess that defined Dallas. My only top-of-the-front-page byline was about the bankruptcy trustees suing extended members of the Hunt family to recover $100 million in assets.

But at one time, Hunt owned millions of acres of Australian ranch land, more than 1,000 racehorses and a collection of ancient coins. He and his brothers invested so heavily in commodity markets for soybeans and sugar beets that they influenced prices worldwide. But it was silver for which they became famous. Their notorious effort to corner the silver market ultimately cost them their fortune. Long before anyone coined the term “too big to fail,” Bunker and his brothers were. Their collapsed threatened a consortium of large banks, and a bailout plan was put together by other banks and blessed by the Federal Reserve.

Hunt and his brothers once defined an era upon which many Texas stereotypes were built. Ultimately, though, history may remember Bunker Hunt as the son who squandered one of the world’s greatest fortunes.

November 28, 2014

Radio Shack’s got problems. No one seems to have answers.

In the latest edition of Texas Monthly, I discuss the long, slow decline of Radio Shack and take a look at the retailer’s grim prospects for the future. Radio Shack is one of those iconic stores that played a big role in many childhoods, including my own. My brother was a Radio Shack regular, between building kit electronics and looking for components for various science fair projects.

In the latest edition of Texas Monthly, I discuss the long, slow decline of Radio Shack and take a look at the retailer’s grim prospects for the future. Radio Shack is one of those iconic stores that played a big role in many childhoods, including my own. My brother was a Radio Shack regular, between building kit electronics and looking for components for various science fair projects.

If it wasn’t the stores that you spent time in, then it’s likely you had some experience with the company’s early personal computers, the TRS-80 or the first laptop, the Model 100. Those glory days, however, are long gone.

During the Super Bowl last February, RadioShack ran an ad in which a mob of eighties pop-culture icons, including Erik Estrada, Hulk Hogan, and the California Raisins, looted one of its stores to the pounding beat of Loverboy’s “Working for the Weekend.” The tagline: “It’s time for a new RadioShack.”

Actually, it’s way past time for a new RadioShack. A month after the big game, the company reported a $400 million loss for the year. Sales had tumbled 15 percent from 2011, the last time the company made a profit. This year, sales for the first six months dropped another 18 percent. In September, RadioShack warned investors that if it couldn’t restructure its debt, it might have to file for bankruptcy. Even some of its lenders seem to think its demise is inevitable. Earlier this year, RadioShack said it would close 1,100 of its 4,400 stores to save money. Lenders blocked the deal, presumably to force the company into bankruptcy. As secured creditors, they would gain control of RadioShack and could shed whatever assets and employees they wanted.

In short, we shouldn’t expect to see a funny RadioShack ad during this season’s Super Bowl. The company may be in bankruptcy by then—if not liquidation.

November 5, 2014

Is the Free Market Slowing Down Your Internet?

When you compare the price that most Americans pay for Internet service, and the speeds they receive for that price, the U.S. is far from a leader in deploying the most important utility of the 21st century. The New York Times’ Claire Cain Miller recently explained why the U.S. has fallen so far behind in Internet speed and affordability.

When you compare the price that most Americans pay for Internet service, and the speeds they receive for that price, the U.S. is far from a leader in deploying the most important utility of the 21st century. The New York Times’ Claire Cain Miller recently explained why the U.S. has fallen so far behind in Internet speed and affordability.

Miller discussed a recent report comparing Internet access in large American cities with those in Europe and Asia. The results aren’t pretty. Some of the cities with the most cost-effective Internet service are those like Lafayette, La., and Chattanooga, Tenn. The reason? Those cities have city-run utilities or startups providing service. Others, such as Kansas City, are test beds for high-speed internet being developed by Google — also not a traditional internet service provider.

In my Texas Monthly piece last year on Google Fiber coming to Austin, I noted that the rollout of high-speed internet in the U.S. is following a similar path to that of electricity in the 1930s. Electric grids were controlled by large monopolies, and the availability was limited. Only after politicians got involved and local governments established city-run utilities or rural areas for cooperatives did electricity deployment become widespread.

Susan Crawford, a former science and technology policy adviser to President Barack Obama and author of Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age told me:

This is the most important input into twenty-first-century businesses, yet we are stumbling along, waiting for these mammoth companies to decide that it’s in

their best interest to make these upgrades. We’re going through all the steps that we went through with electricity.

We want to believe that the free market will address this problem, that competition will emerge that will improve service and lower costs. But that’s happened in only a few select areas. Once again, rural communities are being left even farther behind.

“The free market only does well with things like connectivity,” Crawford said. “We are dooming our own private marketplaces.”

In my own experience, I depend on the Internet to do my job, both via the computer and over the phone. Yet my provider, Comcast, has been plagued by frequent outages, one of which lasted five days. For a while, my outages were almost a monthly occurrence. Yet the only other alternative in my area is AT&T U-verse, which is slower than the service I have now. Despite widespread dissatisfaction with the options, no other company has entered the market to provide an alternative.

As a result, Comcast feels no pressure to improve its service or reduce its prices. Until we find a way to change the landscape, America will continue to fall farther behind in its connection with the world.

October 7, 2014

Rethinking Corporate Welfare

On Saturday, New York Times columnist Joe Nocera took a look at the troubling issue of tax abatements, from the $1.25 billion package that Nevada offered to electric car maker Tesla to the scrutiny that Apple is receiving from the European Union for tax breaks it allegedly received from Ireland.

On Saturday, New York Times columnist Joe Nocera took a look at the troubling issue of tax abatements, from the $1.25 billion package that Nevada offered to electric car maker Tesla to the scrutiny that Apple is receiving from the European Union for tax breaks it allegedly received from Ireland.

Nocera points out that the EU prohibits member countries from offering tax subsidies to companies if it gives them an advantage over rivals in the same country.

Here then is one difference between what transpires in the U.S. and what transpires in Europe: The E.U. has rules intended to prevent nations from giving unjustified tax breaks to companies.

. . . In truth, most tax subsidies don’t make much sense — not for countries and certainly not for states.

In most cases, states vastly overpay for the jobs that are created through such corporate giveaways, Nocera concludes.

Nowhere is the business of corporate welfare more shameless than Texas, where for a decade Gov. Rick Perry has doled out some $222 million at his discretion to any companies that asked — or in some cases didn’t ask.

During my time as a business columnist at the Houston Chronicle, I wrote a lot about the lack of oversight, transparency and accountability at the Texas Enterprise Fund and its sister, the Emerging Technology Fund. In an op/ed in Sunday’s paper, I followed up on a state audit that has finally been done. The results showed, not surprisingly, a lack of oversight, transparency and accountability since the fund’s inception in 2003.

The problem with this expensive economic development game is that no city or state is going to stop it. Politicians love to crow about the potential jobs that will be created by giving away tax money to corporations, and rarely are they held accountable if those promises don’t come true.

Companies, for their part, aren’t going to turn down the money, but few businesses are able to accurately predict their hiring needs years into the future. In the end, it amounts to a bizarre game in which, more often than not, the state pays a bribe to extract a lie from a company that promises to move in.

I’ve talked to economic development officials about this for years. Most hate the game, but feel compelled to play it because everyone else does. Perhaps it’s time to borrow a page from the EU. Only by prohibiting such giveaways across the board can we ever hope that state and local governments will stop wasting tax dollars on corporate welfare.

October 1, 2014

Wyly Slapped with “Staggering” Sanction

Back in June I wrote about the Securities and Exchange Commission’s must-win case against Dallas businessman Sam Wyly. Well, win the SEC did, and now a federal judge has slapped penalties of more than $300 million on Wyly and the estate of his late brother, Charles — sanctions that even the judge herself characterized as “staggering.”

Here’s my update for Texasmonthly.com:

After he was warned that an elaborate scheme of offshore trusts posed an “aggressive and risky” tax strategy, Dallas businessman Sam Wyly dismissed the concerns by saying “if the IRS ever challenged his position, he would litigate for years and settle for pennies on the dollar,” according to documents the government filed against him in court. It hasn’t quite worked out as he planned.

It wasn’t the Internal Revenue Service, but the Securities and Exchange Commission that challenged him – and won. Earlier this year, jurors found him liable for using the trusts to hide more than $550 million in profits from secret stock sales. Now, the judge overseeing the case has slapped Wyly and the estate of his late brother, Charles, with a judgment that requires them to pay a whopping $300 million in sanctions and interest.

The judgment is one of the biggest ever ordered against a single individual, and comprises 10 percent of all the penalties and disgorgements that the SEC ordered for all of last year. Even U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin called her decision “staggering.”

September 29, 2014

Patent trolls of the Piney Woods

(EFF-Graphics via Wikimedia Commons)

In my latest Texas Monthly column, I discuss how the tiny East Texas town of Marshall became a haven for patent trolls. One of the few things that Barack Obama and Antonin Scalia may agree on is that Marshall may be the worst thing that ever happened to intellectual property law. Not surprisingly, the locals don’t see it that way.

Corporate executives across the world are familiar with Marshall, a town of 24,000 people about twenty miles west of the Louisiana border that over the past couple of decades has become the unlikely patent litigation capital of America. More than 1,500 patent cases were filed in Marshall last year, compared with about 1,300 in the entire state of Delaware, the jurisdiction in which most U.S. companies are incorporated. For more than a decade Marshall juries have meted out billions of dollars in patent awards for and against some of the world’s biggest high-tech companies. Apple, Samsung, Motorola, Dell, and Hewlett-Packard are just a few of the household names that have spent time in the Sam B. Hall Jr. federal courthouse.

. . . Not everyone is happy about what goes on in Marshall’s courtrooms. After all, there are no major corporate headquarters in Marshall. Yet thanks to federal law, which has traditionally allowed companies to file patent suits pretty much anywhere, the town’s remoteness has not been an obstacle. Over the years, Marshall has earned a reputation as the intellectual property equivalent of a speed trap, a place where juries smack big companies with huge judgments. And over the years federal lawmakers have tried to do something about it, with little success. The U.S. Supreme Court and the federal appeals court in New Orleans have enacted restrictions on new filings. Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia declared Marshall “a renegade jurisdiction.” During his last State of the Union address, President Barack Obama was likely thinking about the town when he decried “costly, needless” patent litigation.