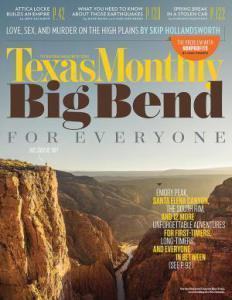

Loren C. Steffy's Blog, page 9

May 24, 2015

Find the Perfect Video Clip Online in a Snap

A shot from The Daily Show’s Vine montage “50 Fox News lies in 6 seconds,” which was assembled with the help of Snapstream’s technology.

Ever wonder how daily comedy programs like The Daily Show and The Colbert Report are able to find so many perfect video clips on such a tight production schedule? The answer is a Houston company founded 15 years ago. Snapstream makes it possible to search for video clips as easily as most people use Google.

But, as I discuss in the latest issue of Texas Monthly, the service isn’t cheap. And unlike Google, Snapstream’s algorithms can only sift through video that’s been recorded for that purpose. That’s why the service is so expensive — all that video storage doesn’t come cheap.

So how long before Snapstream offers an app that let’s you find video clips on your smartphone and lets you paste them to your social media accounts? It will probably be a while.

May 17, 2015

Blue Bell’s response to crisis decidedly corporate

Blue Bell likes to call itself “The Little Creamery,” but its recent response to a listeria outbreak shows it’s really a big corporation. The company continues to receive unprecedented levels of public support, despite a listeria outbreak that killed three people, sickened others.

The dessert maker has recalled of all its products, shutdown of its plants and laid off or furloughed hundreds of employees. Make no mistake: Blue Bell’s lived up to its claim of making “the best ice cream in the country.” But as I write in today’s Houston Chronicle, it’s handling of the crisis and its knowledge that it had a listeria problem years ago that it didn’t reveal raises questions of whether it deserves such unquestioning support.

A half-gallon of Blue Bell Natural Bean Vanilla sits in my freezer, untouched. I could have returned it for a refund or sold it on Craigslist (going rate: $5). Yet I keep it, like a spurned lover holding onto a discarded ring, hoping for the day when the romance is rekindled.

I was born in dairy country and grew up eating fresh-from-the-farm ice cream. Then my family moved to College Station, a mere 40 miles from Brenham, and discovered Blue Bell. My mother, a discerning ice cream aficionado, quickly declared that the “The Little Creamery” made the best she’d ever eaten.

Like so many others, I wanted to believe that Blue Bell’s recent listeria contamination and eventual recall was simply a case of misfortune that would be quickly remedied.

Sadly, a recently revealed U.S. Food and Drug Administration report found that Blue Bell knew of listeria in at least one of its plants two years ago, yet continued selling us its products. Three people have since died and seven others in four states, including Texas, have been sickened.

April 28, 2015

Margin of Error: Why Everyone Hates the Texas Business Tax

How did a state like Texas, which views all taxes with disdain, wind up with a tax like the one it levies on business? This tax is so bad that few other states that adopted one like it kept it for very long. But Texas has had it for almost 10 years.

How did a state like Texas, which views all taxes with disdain, wind up with a tax like the one it levies on business? This tax is so bad that few other states that adopted one like it kept it for very long. But Texas has had it for almost 10 years.

As I explain in my latest Texas Monthly column, few levies have drawn more scorn than the Texas business tax. People complain that it’s too complicated to calculate and that it punishes businesses that are losing money. Tax experts say it impedes economic growth. And many lawmakers criticize it for generating less revenue than it was supposed to. Even lawmakers who supported it a decade ago now say they regret voting for it.

In fact, the tax is the target of more than two dozen bills in the current legislative session, which call for revising it or eliminating it altogether. What were lawmakers thinking, and what are they going to do to fix it?

April 26, 2015

The Elissa: The Untold Story

I was recently in Galveston, and I stopped by to see the tall ship Elissa. She wasn’t there, but before too long she pulled into view and I snapped the above picture. For those who aren’t familiar, the Elissa is a barque, a three-masted, iron-hulled merchant ship built in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1877.

I was recently in Galveston, and I stopped by to see the tall ship Elissa. She wasn’t there, but before too long she pulled into view and I snapped the above picture. For those who aren’t familiar, the Elissa is a barque, a three-masted, iron-hulled merchant ship built in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1877.

How she came to Galveston, though, is a colorful tale that indirectly involves my father, the details of which I pieced together when I was working on my book, The Man Who Thought Like a Ship.�� However, it was an aside to the main narrative, so I left it out of the book.

The Elissa was discovered in Piraeus, near Athens, by Peter Throckmorton, a photojournalist an early pioneer of nautical archaeology. Throckmorton was an early supporter of my father’s work on the Kyrenia Ship and recommended my father for the prestigious Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology in 1974, when my father was still a relative unknown in the field.

The official story is that Throckmorton spotted the Elissa near a shipbreaker’s yard awaiting salvage, but the real story, as it was relayed to me by people who knew him, is more involved. He saw what appeared to be a beaten-down old cargo ship in the Piraeus harbor and guessed by the cut of her bow that she had been a sailing ship even though all her masts had been removed.

Throckmorton made some inquiries around the harbor and found that the ship was owned by smugglers who were bringing in coffee from Italy. He talked his way aboard, and eventually made his way below deck, spotting the plaque that indicated the ship had been built in Aberdeeen in 1877. (You can still see the plaque if you tour the Elissa today.)

Throckmorton knew he had found a classic sailing ship that needed to be preserved. He made an offer to buy her, keeping the ship’s true nature a secret because he didn’t want the smugglers to raise the price. He took out a second mortgage on his apartment in Piraeus, and bought the Elissa. He then set about finding someone who would help him preserve the ship. Among those who were interested were members of the Galveston Historical Foundation, which was looking for a sailing ship to preserve as part of its efforts to restore the city’s historic Strand district.

Throckmorton knew he had found a classic sailing ship that needed to be preserved. He made an offer to buy her, keeping the ship’s true nature a secret because he didn’t want the smugglers to raise the price. He took out a second mortgage on his apartment in Piraeus, and bought the Elissa. He then set about finding someone who would help him preserve the ship. Among those who were interested were members of the Galveston Historical Foundation, which was looking for a sailing ship to preserve as part of its efforts to restore the city’s historic Strand district.

But who would do the restoration work? Peter paid my father a visit in the castle in Kyrenia. In an April 30, 1974 letter to my mother, my father wrote:

Peter Throckmorton has asked me to build or rebuild a three-masted bark, probably in Galveston, Texas, and probably for the ’76 celebration. We don’t know much about it yet except that he has a $300,000 budget.

He didn’t. The $300,000 was likely the money Throckmorton had gotten from mortgaging his apartment. At any rate, nothing ever became of the discussions. The Elissa didn’t make it to Texas for the U.S. Bicentennial. She was finally towed there in 1979 and underwent an extensive two-year restoration effort.

By then, my father had completed the Kyrenia Ship reconstruction and had become one of the founding faculty for the nautical archaeology program at Texas A&M University in College Station, about 150 miles from Galveston.

March 30, 2015

Schlitterbahn: Lucrative When Wet

If you grew up in Texas, you probably are familiar with Schlitterbahn, the water park on the banks of the Comal River in New Braunfels. Among many of my friends, “Schlitterbahn” was synonymous with floating the river, because the original portion of the park actually used river water for its rides. Park and river were, in many ways, one.

If you grew up in Texas, you probably are familiar with Schlitterbahn, the water park on the banks of the Comal River in New Braunfels. Among many of my friends, “Schlitterbahn” was synonymous with floating the river, because the original portion of the park actually used river water for its rides. Park and river were, in many ways, one.

In my latest��Texas Monthly��column, I explain how Schlitterbahn went from four slides on the Comal to five locations in two states, and how its biggest growth push came during a time of drought and tight finances. It helps that the family that runs Schlitterbahn includes a water park savant whose designs have influenced water parks worldwide.

In the early eighties, a family rolling down Interstate 35 between Georgetown and San Antonio would have confronted a string of uniquely Texan tourist attractions. Over the years, Wonder World, Inner Space Cavern, the Snake Farm, and Ralph the Swimming Pig at Aquarena Springs probably pried millions of dollars from the hands of road-weary parents pestered by their carsick kids. Schlitterbahn, the German-themed water park overlooking the Comal River, in New Braunfels, seemed like just another attraction on this highway of homespun entertainment.

But over the past fifteen years, Schlitterbahn has left its fellow I-35 attractions in the dust. Today its parent company operates five parks, hosts 2 million annual visitors, employs 500 full-time and 4,500 seasonal workers, and holds more than sixty patents on ride designs and water park technology. In 2013 attendance at the top twenty water parks in the United States fell by 2.3 percent from the year before, according to Aecom Technology Corporation and the Themed Entertainment Association. During that same period, attendance at Schlitterbahn���s flagship park���which has the highest of any water park in the country outside Orlando, Florida���rose by 1 percent. ���The brand is so strong that there���s probably not a week that goes by that we don���t receive a solicitation to open a new park,��� says Gary Henry, the oldest of the three siblings who run the company.

March 16, 2015

BizRadio: The Next Chapter in Controversy

The devastation left by a tornado that hit Joplin, Mo., in 2011.

Sunday’s Houston Chronicle had a lengthy article on former Sugar Land mayor David Wallace and his business to help rejuvenate struggling cities. Wallace has apparently closed up shop, leaving several cities in the lurch and investors wondering what happened to their money.

Wallace also was a major backer of BizRadio, an AM network that once broadcast investment advice and other business information in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Denver and Colorado Springs.�� I first wrote about BizRadio after its founders ran afoul of the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2009.

Wallace and a business partner, Costa Bajjali, had a firm that offered investors a chance to invest in real estate projects, although large portions of the funds the firm raised were funneled into BizRadio, the Chronicle reported. Although Wallace’s disputes involving BizRadio were settled, he later went on to pitch his services to cities such as Waco and Amarillo to help with redevelopment projects. Few materialized as planned, according to the Chronicle. The biggest deal came in 2011, when the Wallace Bajjali firm was hired to rebuild Joplin, Mo., after it was leveled by a tornado.

As the Chronicle reported:

. . . Officials learned the same lesson that Wallace’s investors had a few years earlier: Neither he nor his company was quite what it seemed. For all the plans and vision statements, they couldn’t make good on their plans.

By the time Wallace Bajjali quietly left town – after receiving $1.7 million in fees from the city and $5 million in a private loan – the partners had failed to get so much as a parking lot built.

The firm apparently closed up shop at the beginning of the year.