Edward Feser's Blog, page 58

February 19, 2018

Drunk stoned perverted dead

The immorality of perverting a faculty is far from the whole of natural law moral reasoning, but it is an important and neglected part of it. The best known application of the idea is within the context of sexual morality, and it is also famously applied in the analysis of the morality of lying. Another important and perhaps less well known application is in the analysis of the morality of using alcohol and drugs. The topic is especially timely considering the current trend in the U.S. toward the legalization of marijuana.Before proceeding, the reader is asked to keep in mind that “perverted faculty arguments” in traditional natural law theory deploy the concept of perversion in a specific, technical sense. The perversion of a human faculty essentially involves both using the faculty but doing so in a way that is positively contrary to its natural end. As I’ve explained many times, simply to refrain from using a faculty at all is not to pervert it. Using a faculty for something that is merely other than its natural end is also not to pervert it. Hence, suppose faculty F exists for the sake of end E. There is nothing perverse about not using Fat all, and there is nothing perverse about using F but for the sake of some other end G. What is perverse is using F but in a way that actively prevents E from being realized. It is this contrarinessto the very point of the faculty, this outright frustration of its function, that is the heart of the perversity.

The immorality of perverting a faculty is far from the whole of natural law moral reasoning, but it is an important and neglected part of it. The best known application of the idea is within the context of sexual morality, and it is also famously applied in the analysis of the morality of lying. Another important and perhaps less well known application is in the analysis of the morality of using alcohol and drugs. The topic is especially timely considering the current trend in the U.S. toward the legalization of marijuana.Before proceeding, the reader is asked to keep in mind that “perverted faculty arguments” in traditional natural law theory deploy the concept of perversion in a specific, technical sense. The perversion of a human faculty essentially involves both using the faculty but doing so in a way that is positively contrary to its natural end. As I’ve explained many times, simply to refrain from using a faculty at all is not to pervert it. Using a faculty for something that is merely other than its natural end is also not to pervert it. Hence, suppose faculty F exists for the sake of end E. There is nothing perverse about not using Fat all, and there is nothing perverse about using F but for the sake of some other end G. What is perverse is using F but in a way that actively prevents E from being realized. It is this contrarinessto the very point of the faculty, this outright frustration of its function, that is the heart of the perversity.There is also nothing necessarily perverse about using some thing other than one’s own natural faculties in a way that is contrary to its end (e.g. using a toothbrush to clean the sink rather than one’s teeth, or using a plant or animal for food). Moral reasoning is about what I, the moral agent, ought to do. It is because certain acts would actively frustrate my own natural ends, which are constitutive of what is good for me, that they constitute a perverse exercise of practical reason. Doing what frustrates some other thing does not per se frustrate my own natural ends, and thus is not intrinsically perverse in the relevant sense. (It may or may not be wrong for some other reason, but that’s a different question.) As I have suggested elsewhere, perverting a faculty is in this way comparable in its irrationality to a performative self-contradiction.

I have spelled out the nature of perverted faculty reasoning in detail in my article “In Defense of the Perverted Faculty Argument,” from my anthology Neo-Scholastic Essays . I respond there to all the standard objections, most of which are based on misunderstandings. The uninitiated reader who objects to the perverted faculty reasoning that follows is urged to read that essay before commenting, because odds are I’ve already answered your objection there. For example, please don’t waste your time or mine by raising tired purported counterexamples like the use of ear plugs, a sterile married couple having sex, etc. I’ve already explained in the article why these do not count as perversions of a faculty.

On to our subject, then: The standard natural law position is that the use of alcohol or drugs is always and intrinsically immoral when (a) it subverts reason, and (b) it does so for the sake of an end which is not itself prescribed by reason. If conditions (a) and (b) are not both met, then the use of alcohol or drugs is not always and intrinsically wrong (even if certain circumstances might make it wrong). Let’s elaborate on these two conditions.

First, what counts as subverting reason? Merely altering one’s mood is not problematic. As the Thomistic natural law theorist John C. Ford notes in his book Man Takes a Drink: Facts and Principles about Alcohol, the natural law position regards the use of alcohol as legitimate when it merely leads to “a mild lift, or a comfortable sense of relaxation – a mild euphoria” (p. 52), or “mild relaxation, or mild exhilaration, or cheerfulness” (p. 56). One’s reason can still be perfectly in charge of one’s behavior in this case. (Thus does Proverbs 31:6-7 say: “Give strong drink to one who is perishing, and wine to those in bitter distress; let them drink and forget their poverty, and remember their misery no more.”)

The trouble comes when reason is either no longer in charge or its control is impaired. This would be true, for example, of someone who has drunk so much that he cannot think or perceive clearly, or whose moral inhibitions have become relaxed, or whose other inhibitions are lowered to the point where he does things he would otherwise be too embarrassed to do, or whose motor skills have been impaired.

What about condition (b)? Doing something that one knows will suspend reason is not always and intrinsically wrong. For example, as Aquinas writes:

For it is not contrary to virtue, if the act of reason be sometimes interrupted for something that is done in accordance with reason, else it would be against virtue for a person to set himself to sleep. (Summa Theologiae II-II.153.2)

The kind of rational thing a human being is is a rational animal, and our animality requires us to sleep, which temporarily interrupts reason. This is not contrary to our nature, because the whole point of sleep is precisely to preserve the health of the whole rational animal. Similarly, when for the sake of surgery we take an anesthetic, we temporarily suspend reason but are not acting contrary to reason, precisely because our aim is to preserve the whole organism of which reason is a faculty. For the same reason, when alcohol or drugs are used for medical purposes even though it is foreseen that they will subvert reason, such use is not necessarily wrong. The situation is analogous to the amputation of a diseased body part for the sake of preserving the whole body. Reason temporarily suspends itself precisely for the sake of preserving itself.

What is wrong is when reason is subverted for the sake of something inferior toreason, as when someone deliberately drinks to the point of suspending reason merely for the sake of the more intense sensory pleasure this would bring. Reason subverting itself for the sake of something inferior to reason is perverse, in the “perverted faculty argument” sense of the word. It is reason acting directly contrary to (rather than merely other than) its own natural end. It essentially involves a rational animal deliberately trying to make of himself, if only partially and temporarily, a non-rational animal.

Naturally, there are also other considerations that make intoxication morally problematic, such as the risks to health and safety it can pose. But it is the perversion of the rational faculty that makes it always and intrinsically wrong to use alcohol or drugs to the point of subverting reason for the sake of mere sensory pleasure. It is a kind of self-mutilation of rationality, the highest and distinctive human faculty. Ford writes:

It is interesting to note that some theologians treat of drunkenness, especially habitual drunkenness, under the commandment “Thou shalt not kill.” The Fifth Commandment, besides forbidding murder and self-destruction, is taken to forbid self-mutilation and to command a reasonable care of one’s own life and health. There is also a psychological appropriateness in considering drunkenness a kind of suicide. Especially for the alcoholic, each cup has a little death in it, a little of that oblivion which he seeks, consciously or unconsciously. (p. 74)

Ford’s thesis that the drunkard or stoner seeks a kind of temporary suicide of his rationality is lent support by the way descriptions like wasted, smashed, bombed, hammered, stoned, dead drunk, etc. are used approvingly.

A common libertarian rhetorical trick is to speak as if there is hypocrisy or inconsistency in approving of alcohol while disapproving of other intoxicating substances. This is quite silly and overlooks an obvious distinction. It is easy for most people to use alcohol in the moderate way that results merely in the “mild exhilaration” or “cheerfulness” that does not subvert reason, and a great many people do in fact habitually use it in precisely this way. By contrast, many other drugs are used precisely for the sake of attaining a high that subverts reason. If someone approves of recreational alcohol use only insofar as it does not subvert rationality, and disapproves of the recreational use of other drugs only insofar as they do subvert rationality, then there is no hypocrisy or inconsistency at all.

To be sure, it is true that sensibilities about what substances it is licit to use in moderation can be to some extent culturally relative and reflect mere prejudice. Ford gives an amusing example to illustrate the point:

It was only a few hundred years ago that the devout priests of a certain religious order in Europe protested bitterly against the introduction of coffee at breakfast. They maintained it was expensive, luxurious, imported and exotic, not in keeping with religious poverty, and not befitting men dedicated to God. They insisted on retaining their traditional breakfast beverage, which was beer. (p. 58)

All the same, not all misgivings about the use of a drug are based on mere cultural prejudice, and the imperative of avoiding the deliberate suspension of reason provides an objective and clear criterion by which to distinguish substances that can be used in moderation and those that should be avoided altogether.

As Plato warned in the Republic, egalitarian societies tend to be increasingly dominated by the pull of the lower appetites, and increasingly impatient with the counsel of reason. As with our society’s ever deepening immersion in sins of the flesh and the rise of the ridiculous “foodie phenomenon,” accelerating laxity with respect to drug use reflects this decadence, rather than more careful and consistent thinking about the subject. If you won’t listen to Plato, at least listen to Animal House.

Published on February 19, 2018 11:29

February 13, 2018

Time, space, and God

Samuel Clarke’s

A Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God

is one of the great works of natural theology. But Clarke’s position is nevertheless in several respects problematic from a Thomistic point of view. For example, Clarke, like his buddy Newton, takes an absolutist view of time and space. Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy of nature does not take an absolutist position (though it does not exactly take a relationalist position either). There are independent metaphysical reasons for this, but for the moment I want to focus on a theological problem.As Thomists sometimes point out, the absolutist position makes space and time infinite and uncreated, and thus effectively deifies them. Clarke and Newton don’t exactly deny this. They avoid making time and space out to be deities alongside God, though, by more or less making of them divine attributes. Recall that for Newton, famously, space is God’s sensorium. It essentially becomes identified with God’s omnipresence. Time becomes identical with his eternity, or rather with everlasting duration. God is brought into time.

Samuel Clarke’s

A Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God

is one of the great works of natural theology. But Clarke’s position is nevertheless in several respects problematic from a Thomistic point of view. For example, Clarke, like his buddy Newton, takes an absolutist view of time and space. Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy of nature does not take an absolutist position (though it does not exactly take a relationalist position either). There are independent metaphysical reasons for this, but for the moment I want to focus on a theological problem.As Thomists sometimes point out, the absolutist position makes space and time infinite and uncreated, and thus effectively deifies them. Clarke and Newton don’t exactly deny this. They avoid making time and space out to be deities alongside God, though, by more or less making of them divine attributes. Recall that for Newton, famously, space is God’s sensorium. It essentially becomes identified with God’s omnipresence. Time becomes identical with his eternity, or rather with everlasting duration. God is brought into time.The problems with this, from a Thomist (and more generally, classical theist) perspective, should be obvious. Space is extended. God is not. Time entails change. God is changeless. And if space and time are divine attributes, then we have to take a pantheist or at least panentheist view of the natural world. For the most general features of nature would then be aspects of God.

William Lane Craig thinks this isn’t quite right. He writes:

Newton… declares explicitly that space is not in itself absolute and therefore not a substance. Rather it is an emanent – or emanative – effect of God. By this notion Newton meant to say that time and space were the immediate consequence of God's very being. God's infinite being has as its consequence infinite time and space, which represent the quantity of His duration and presence. Newton does not conceive of space or time as in any way attributes of God Himself, but rather, as he says, concomitant effects of God. (Time and Eternity, p. 46)

Putting aside questions of Newton exegesis, would this get Clarke and Newton out of the frying pan? Only by landing them in the fire. For if time and space are “concomitant effects” or “the immediate consequence” of “God's very being,” then their existence follows of necessity from his. And there are several problems with this thesis.

First, it would entail that the act of creation was not free (or at least that the creation of space and time was not free). For according to this thesis, God cannot not create time and space. But freedom is one of the divine attributes, knowable even by way of purely philosophical argumentation. (See e.g. Summa Theologiae I.19.10; Summa Contra Gentiles I.81, I.88 and II.23; Five Proofs of the Existence of God , pp. 224-228.)

Second, for God to create of necessity would detract from his perfection. As Aquinas argues in Summa Theologiae I.19.3:

God wills things apart from Himself in so far as they are ordered to His own goodness as their end. Now in willing an end we do not necessarily will things that conduce to it, unless they are such that the end cannot be attained without them; as, we will to take food to preserve life, or to take ship in order to cross the sea. But we do not necessarily will things without which the end is attainable, such as a horse for a journey which we can take on foot, for we can make the journey without one. The same applies to other means. Hence, since the goodness of God is perfect, and can exist without other things inasmuch as no perfection can accrue to Him from them, it follows that His willing things apart from Himself is not absolutely necessary.

End quote. So, if this is correct, then if God is perfect, his willing of things other than himself is not necessary. But then, if his willing of things other than himself (in particular, time and space) isnecessary, then by modus tollens he is not perfect.

Similarly, in Summa Contra Gentiles II.23.8, Aquinas argues that since “agents which act by will are obviously more perfect than those whose actions are determined by natural necessity,” God must be free.

A third problem is that if the existence of time and space follows necessarily from God’s existence, then not only did they have no beginning but they in principle could not have had a beginning. This would not conflict with classical theism per se, but it would conflict with any version of classical theism which incorporates biblical revelation.

Fourth, we have a conflict with Catholic orthodoxy. The First Vatican Council teaches:

If anyone says that finite things, both corporal and spiritual, or at any rate, spiritual, emanated from the divine substance… let him be anathema.

If anyone… holds that God did not create by his will free from all necessity, but as necessarily as he necessarily loves himself… let him be anathema.

Fifth, the position Craig attributes to Newton is not really a coherent one, at least not on a Thomistic metaphysical analysis. For the position in question essentially holds that time and space cannot not exist and yet are not divine attributes. But if they cannot not exist, then time and space must be purely actual and there must be in them no distinction between essence and existence. But in that case they are divine attributes, since only of God can these things be said. On the other hand, if they are not divine attributes, then they must not be purely actual and there must be in them a distinction between essence and existence. In that case, though, it is false to say that they cannot not exist, since anything that is less than pure actuality, and anything in which there is a distinction between essence and existence, can in principle fail to exist.

So, there just is no sense to be made of the idea that there is something distinct from God that he cannot not create. If he cannot not create it then that is only because it cannot not exist, in which case it is purely actual and subsistent being itself and thus really identical with God. If it is really distinct from God, then it is not purely actual or subsistent being itself, and thus it can fail to exist and God can refrain from creating it. The supposed middle ground position between pantheism on the one hand, and affirming the contingency of time and space on the other, is an illusion.

Published on February 13, 2018 11:47

February 11, 2018

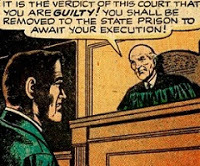

NOR on By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

In the latest issue of New Oxford Review, F. Douglas Kneibert kindly reviews

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

. From the review:

In the latest issue of New Oxford Review, F. Douglas Kneibert kindly reviews

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment

. From the review: Catholics are so accustomed to hearing that opposition to capital punishment is pro-life that few may realize there are good reasons to support it. Those reasons are set forth in a systematic and convincing manner in By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed. Edward Feser and Joseph M. Bessette find the pendulum has swung too far in one direction in the capital-punishment debate (to the extent there is one today), and Catholics are confused when told that something their Church upholds, and has always upheld, is now considered immoral…Their approach is rigorously logical, philosophical, and biblical, and they defend capital punishment as an essential recourse for society to punish the worst criminals. Feser and Bessette never stray from Catholic teaching and tradition in their treatment of the subject…

In the tradition of Aquinas, the authors not only lay out a solid case for capital punishment but also address the various arguments against it – that it’s an affront to human dignity, that it doesn’t deter, that it forecloses the possibility of reform, and that the innocent might sometimes be executed. After careful examination, the authors find all such arguments wanting…

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed asks much of the reader; its thorough and closely reasoned treatment of a complex subject allows no shortcuts. But those who persevere to the end are amply rewarded. Feser and Bessette accomplish what they set out to do: present a badly needed corrective to what recently has been a largely one-sided treatment of capital punishment. Catholics who are open to hearing the case for it – perhaps for the first time – will find this book indispensable.

Published on February 11, 2018 17:12

February 8, 2018

The latest on Five Proofs

Check out a short interview I did for EWTN’s Bookmark Brief, hosted by Doug Keck, on the subject of

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. The much longer interview I did for Bookmarkwill appear before long.

Check out a short interview I did for EWTN’s Bookmark Brief, hosted by Doug Keck, on the subject of

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. The much longer interview I did for Bookmarkwill appear before long. At First Things, Dan Hitchens reflects on how the arguments of Five Proofs might be received in an age of short attention spans.

Jeff Mirus at Catholic Culture recommends Five Proofs.

At Catholic World Report, Christopher Morrissey kindly reviews Five Proofs. From the review:Whether all readers are convinced by Feser’s proofs or not, Feser’s lively approach in this book nonetheless demonstrates at least this much: despite all their bluster, natural theology’s funeral directors will inevitably be buried first. Feser takes a shovel to them.

End quote. Morrissey also offers some interesting critical reflections on the Augustinian proof (to which I may respond in a future post). As they say, read the whole thing. Some further comments from Morrissey at B.C. Catholic.

The blog Ontological Investigations is critically examining the book in a series of posts. Some of what is said is quite off-base (e.g. the false claim that I do not address the most serious critics). But overall this seems to be a serious attempt to grapple with the book’s arguments, and I may respond to some of it in a future post.

Published on February 08, 2018 12:50

January 31, 2018

David Foster Wallace on abstraction

In his book

Everything and More: A Compact History of Infinity

(he had a way with titles), David Foster Wallace has some wise things to say about abstraction. To orient ourselves, let’s start with the definition of “abstract” he quotes from the O.E.D.: “Withdrawn or separated from matter, from material embodiment, from practice, or from particular examples. Opposed to concrete.” So, for example, a billiard rack or a dinner bell is a concrete, particular material object. Triangularity, by contrast, is a general pattern we mentally abstract or separate out from such objects and consider apart from their individualizing material features (being made of wood or steel, being brown or silver, weighing a certain amount, and so on).Mathematics is a paradigmatic example of a discipline that deals with abstractions, and it is the one that is the focus of Wallace’s book (though he has some things to say about philosophy too). He notes how children are introduced to numbers:

In his book

Everything and More: A Compact History of Infinity

(he had a way with titles), David Foster Wallace has some wise things to say about abstraction. To orient ourselves, let’s start with the definition of “abstract” he quotes from the O.E.D.: “Withdrawn or separated from matter, from material embodiment, from practice, or from particular examples. Opposed to concrete.” So, for example, a billiard rack or a dinner bell is a concrete, particular material object. Triangularity, by contrast, is a general pattern we mentally abstract or separate out from such objects and consider apart from their individualizing material features (being made of wood or steel, being brown or silver, weighing a certain amount, and so on).Mathematics is a paradigmatic example of a discipline that deals with abstractions, and it is the one that is the focus of Wallace’s book (though he has some things to say about philosophy too). He notes how children are introduced to numbers:First they are given, say, five oranges. Something they can touch or hold. Are asked to count them. Then they are given a picture of five oranges. Then a picture that combines the five oranges with the numeral ‘5’ so they associate the two. Then a picture of just the numeral ‘5’ with the oranges removed. The children are then engaged in verbal exercises in which they start talking about the integer 5 per se, as an object in itself, apart from five oranges. In other words they are systematically fooled, or awakened, into treating numbers as things instead of as symbols for things. Then they can be taught arithmetic, which comprises elementary relations between numbers. (pp. 8-9)

This little narrative nicely illustrates the sense in which an Aristotelian would regard numbers as abstract objects. (To be sure, Wallace himself was not an Aristotelian, but it turns out that some of his examples and remarks are readily adaptable to Aristotelian purposes.) Numbers are objects in the sense that we can refer to them, attribute features to them, etc. They are abstractobjects in the sense that they exist only as abstracted out from concrete reality by the intellect. There can be five apples in mind-independent reality, or five dogs, or five donuts, but not five itself, considered as a kind of freestanding entity. The number five is not an “abstract object” in the Platonic sense of the term common in contemporary philosophy (viz. an object that exists in some third kind of way over and above intellects on the one hand and concrete particulars on the other), and could not be. For what is abstract is, for the Aristotelian, what results from abstraction, and abstraction is a mental activity of considering one aspect of a thing in isolation from other aspects.

The example also indicates, at least obliquely, both the power and the perils of abstraction. That mathematical reasoning is powerful goes without saying, and it would not be powerful if it didn’t get at something deep in the nature of objective reality. The intellect doesn’t make up mathematical truth out of whole cloth, but pulls it out from the concrete reality into which it is, as it were, mixed. The peril is that we can easily be “fooled” (as Wallace puts it) into treating mathematical objects as if they existed outside the mind in precisely the abstract way in which they exist within the mind.

Nor is it merely that abstract objects – numbers, geometrical figures, universals, etc. – do not exist in this third, Platonic way. Another peril is that we are tempted to take what are really just artifacts of the abstractive exercise to be features of mind-independent reality. Commenting on Zeno’s dichotomy paradox, Wallace writes:

[T]here’s obviously some semantic shiftiness going on here… [which] lies in the implied correspondence between an abstract mathematical entity – here an infinite geometric series – and actual physical space… [T]raversing an infinite number of dimensionless mathematical points is not obviously paradoxical in the way that traversing an infinite number of physical-space points is… [T]he translation of an essentially mathematical situation into natural language somehow lulls us into forgetting that regular words can have vastly different senses and referents. (p. 70)

As the example of Zeno shows, the tendency to confuse abstractions with concrete reality is the source of many metaphysical errors. To be sure, as Wallace immediately goes on to say of the specific muddle he calls our attention to:

Note… that this is exactly what the abstract symbolism and schemata of pure math are designed to avoid, and why technical math definitions are often so numbingly dense and complex. You want no room for ambiguity or equivocation. Mathematics… is an enterprise consecrated to the ideal of precision.

Which all sounds very nice, except it turns out that there is also immense ambiguity – formal, logical, metaphysical – in many of the basic terms and concepts of math itself. In fact the more fundamental the math concept, the more difficult it usually is to define. This is itself a characteristic of formal systems. Most of math’s definitions are built up out of other definitions; it’s the really root stuff that has to be defined from scratch. Hopefully… that scratch will have something to do with the world we all really live in. (pp. 70-1)

Wallace seems to think that the way people study math at more advanced levels tends to exacerbate the problem:

The trouble with college math classes– which classes consist almost entirely in the rhythmic ingestion and regurgitation of abstract information, and are paced in such a way as to maximize this reciprocal data-flow – is that their sheer surface-level difficulty can fool us into thinking we really know something when all we really ‘know’ is abstract formulas and rules for their deployment. Rarely do math classes ever tell us whether a certain formula is truly significant, or why, or where it came from, or what was at stake. There’s clearly a difference between being able to use a formula correctly and really knowing how to solve a problem, knowing why a problem is an actual mathematical problem and not just an exercise. (p. 52)

Now, this is an extremely important point, which applies well beyond mathematics itself. The sheer difficulty of reasoning about abstractions can lead us to overestimate the significance of the payoff, especially when the payoff is indeed significant in some respects. Nowhere is this truer than in modern physics. As Wallace writes:

The modern transition from geometric to algebraic reasoning was itself a symptom of a larger shift. By 1600, entities like zero, negative integers, and irrationals are used routinely. Now start adding in the subsequent decades’ introductions of complex numbers, Napierian logarithms, higher-degree polynomials and literal coefficients in algebra – plus of course eventually the 1st and 2nd derivative and the integral – and it’s clear that as of some pre-Enlightenment date math has gotten so remote from any sort of real-world observation that we and Saussure can say verily it is now, as a system of symbols, “independent of the objects designated,” i.e. that math is now concerned much more with the logical relations between abstract concepts than with any particular correspondence between those concepts and physical reality. The point: It's in the seventeenth century that math becomes primarily a system of abstractions from other abstractions instead of from the world.

Which makes the second big change seem paradoxical: math’s new hyperabstractness turns out to work incredibly well in real-world applications. In science, engineering, physics, etc. (pp. 106-7)

But this tremendous effectiveness can be misleading (and I should note that in what follows I go beyond anything Wallace himself says). Modern physics is very difficult indeed; unlike mathematics, it is concerned with the physical world; and the payoff in predictive and technological success is enormous. The temptation is strong to conclude that everything in the mathematical model of the world presented by physics corresponds to something in physical reality, and that there is nothing in physical reality that isn’t captured by the model presented by physics.

But it simply isn’t so, and the mathematical abstractness of physics is precisely what guarantees that it isn’t so. Abstraction by its very nature leaves out much that is in concrete reality, and the more abstract the model arrived at (as when, to use Wallace’s nice phrase, we are dealing with “a system of abstractions from other abstractions”), the more that is left out. Physics can no more tell you everything there is to know about the material world than learning how to count oranges can tell a child everything there is to know about oranges. As Bertrand Russell put it in a passage I’ve often quoted:

It is not always realised how exceedingly abstract is the information that theoretical physics has to give. It lays down certain fundamental equations which enable it to deal with the logical structure of events, while leaving it completely unknown what is the intrinsic character of the events that have the structure… All that physics gives us is certain equations giving abstract properties of their changes. But as to what it is that changes, and what it changes from and to – as to this, physics is silent. (My Philosophical Development, p. 13)

Or, as Russell put it more pithily and wittily elsewhere:

Ordinary language is totally unsuited for expressing what physics really asserts, since the words of everyday life are not sufficiently abstract. Only mathematics and mathematical logic can say as little as the physicist means to say. (The Scientific Outlook, p. 82)

Like Zeno, contemporary popularizers of science, and sometimes scientists themselves, confuse mathematical abstractions with concrete physical reality and draw absurd metaphysical conclusions. This is precisely what happens when it is claimed that relativity has shown that time and change are illusory, as Lee Smolin and Raymond Tallis have recently pointed out. Indeed, as Tallis emphasizes, the tendency in modern physics is to abstract from the notion of time whatever isn’t space-like, but also to abstract from the notion of space everything but pure quantity – and thus to treat time as an abstraction from an abstraction, in other words.

But again, now I’m going beyond Wallace, so I’ll stop. Much more on these subjects forthcoming in the philosophy of nature/science book I am currently working on.

Further reading:

Concretizing the abstract

Think, McFly, think!

Progressive dematerialization

Rucker’s Mindscape

Five Proofs of the Existence of God , Chapter 3

Published on January 31, 2018 17:43

January 30, 2018

Coming to a campus near you

On Tuesday, February 6, I will be speaking at Brown University on the topic of capital punishment and natural law. Prof. James Keating will respond. The event is sponsored by the Thomistic Institute, and details are available at the Institute’s website and at Facebook.

On Tuesday, February 6, I will be speaking at Brown University on the topic of capital punishment and natural law. Prof. James Keating will respond. The event is sponsored by the Thomistic Institute, and details are available at the Institute’s website and at Facebook. On Saturday, March 17, I will be presenting a paper on the topic “Cooperation with Sins Against Prudence” at a conference on Cooperation with Evilat the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C. The other conference speakers will be Steven Long, Msgr. Andrew McLean Cummings, Christopher Tollefsen, and Fr. Ezra Sullivan, OP.

On Thursday, April 12, I will be speaking at Baylor University on the topic of capital punishment and natural law. The event is sponsored by the Thomistic Institute, and more information will be forthcoming at the Institute’s website.

On Thursday, April 19, I will be speaking at Southern Evangelical Seminary on the topic of the nature of God. Details forthcoming.

More talks for this year to be announced. Stay tuned.

Published on January 30, 2018 10:43

January 25, 2018

Prof. Fastiggi’s pretzel logic

I’m going to take a break from the topic of the death penalty soon – I’m quite sick of it myself, believe you me – but the trouble is that critics of

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

keep saying things that demand a response. The latest example is Prof. Robert Fastiggi, who in a series of combox remarks has replied to my recent Catholic World Report article on capital punishment and the ordinary magisterium. Once again, he ties himself in ever more convoluted logical knots trying to justify the unjustifiable, viz. the possibility of a reversal of 2000 years of clear and unbroken magisterial and scriptural teaching. But the attempt is well worth calling attention to, because it shows just how far one has to go through the looking glass in order to try to avoid the implications of the evidence Joe Bessette and I have set out in our book.Since one of his more oversensitive admirers has falsely accused me of gratuitous attacks on Prof. Fastiggi, I want to preface the remarks that follow by saying that they are in no way intended personally. On the contrary, I admire Prof. Fastiggi for his unwavering dedication to the Church, for his erudition, and for the unfailingly gentlemanly way he has engaged his critics both in the debate over capital punishment and in the other, often heated, theological debates that have arisen during the pontificate of Pope Francis. Prof. Fastiggi hits hard but he plays fair. I am only doing the same. (And any reader offended by the occasional joke or Photoshop image needs to get a sense of humor.)

I’m going to take a break from the topic of the death penalty soon – I’m quite sick of it myself, believe you me – but the trouble is that critics of

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

keep saying things that demand a response. The latest example is Prof. Robert Fastiggi, who in a series of combox remarks has replied to my recent Catholic World Report article on capital punishment and the ordinary magisterium. Once again, he ties himself in ever more convoluted logical knots trying to justify the unjustifiable, viz. the possibility of a reversal of 2000 years of clear and unbroken magisterial and scriptural teaching. But the attempt is well worth calling attention to, because it shows just how far one has to go through the looking glass in order to try to avoid the implications of the evidence Joe Bessette and I have set out in our book.Since one of his more oversensitive admirers has falsely accused me of gratuitous attacks on Prof. Fastiggi, I want to preface the remarks that follow by saying that they are in no way intended personally. On the contrary, I admire Prof. Fastiggi for his unwavering dedication to the Church, for his erudition, and for the unfailingly gentlemanly way he has engaged his critics both in the debate over capital punishment and in the other, often heated, theological debates that have arisen during the pontificate of Pope Francis. Prof. Fastiggi hits hard but he plays fair. I am only doing the same. (And any reader offended by the occasional joke or Photoshop image needs to get a sense of humor.)Let me start with Prof. Fastiggi’s strangest remark. In my article, I cited the CDF document Donum Veritatis, which rejects the thesis that the magisterium could be “habitually mistaken” in its prudential judgments. I argued that if the Church could not be habitually mistaken even in her prudential judgments, then a fortiori she could hardly be habitually mistaken on much graver matters of moral principle and scriptural interpretation. Now, the Church has for two millennia taught that the death penalty is legitimate at least in principle, and done so on biblical grounds. Hence, if she were to reverse this teaching – which Fastiggi claims is possible – then it would follow that the Church would be saying that she has after all been habitually mistaken, for two millennia, about grave matters of moral principle and scriptural interpretation. Therefore, I concluded, the Church cannot carry out such a reversal, consistent with her claims about her own infallibility.

Here is how Fastiggi responds:

Professor Feser, in his book co-authored with Prof. Bessette, states that St. John Paul II’s position [according to which capital punishment should be applied very rarely at most] “is a mistake, and a serious one” (p. 197). This, though, means that since 1995 the magisterium has been habitually mistaken on a prudential judgment (and it’s really much more than prudential). Feser, therefore, contradicts the very passage from the CDF’s 1990 instruction, Donum Veritatis, that he cites… To suggest that the magisterium has been habitually mistaken for 23 years on the death penalty seems very problematical. Does not Feser believe that the Church’s magisterium has enjoyed divine assistance in the last 23 years with regard to capital punishment?

End quote. So, according to Fastiggi, it “seems very problematical” to suppose that the magisterium could have gotten a prudential judgment wrong for 23years, but not problematical to suppose that the magisterium could have gotten a matter of basic moral principle and scriptural interpretation wrong for two millennia. What can one say about such a manifestly absurd position other than that it is manifestly absurd? I am sorry if that sounds unkind to Prof. Fastiggi, but the offended reader should worry less about whether this judgment sounds unkind, and more about whether it is true. And if the reader thinks it is not true, I challenge him to explain exactly howthis particular view of Prof. Fastiggi’s can be defended against the charge of absurdity.

Furthermore, I am also puzzled that someone with Prof. Fastiggi’s knowledge of Church history would think 23 years is a long time for the magisterium to have gotten a prudential judgment wrong. By the standards of Church history, 23 years is a mere blip. Moreover, there are many examples of bad prudential judgments that have stood for comparable lengths of time.

Take, for example, the notorious Cadaver Synod and its aftermath, which not only involved the bizarre spectacle of Pope Stephen VI putting the corpse of his predecessor Pope Formosus on trial and then desecrating it, but also Stephen’s nullifying all of Formosus’ official acts and declaring his ordinations invalid. Two later popes and two synods reversed Stephen’s decision, but then a yet laterpope, Sergius III, and a synod he called, reversed that decision and reaffirmedStephen’s judgments. Sergius also had his predecessor murdered and backed up his reaffirmation of Stephen’s decrees with threats of violence. The whole sorry spectacle was initiated by a scandalous and indeed insane public act by one pope, reinforced by gravely immoral acts by another, involved contradictory judgments made by several popes and synods, and lasted for about 15 years. As The Oxford Dictionary of Popes notes, given that the sacraments and much of the life of the Church depend on the validity of ordinations and the reliability of official papal acts, “the resulting confusion was indescribable” (p. 119).

Or consider the Great Western Schism, which lasted for forty years. It was a consequence of mistakes made by Pope Urban VI, whom the Catholic Encyclopediadescribes as “obstinate and intractable” and “inconstant and quarrelsome,” with “his whole reign [being] a series of misadventures.” It was perpetuated by further decisions made by other members of the hierarchy. At the lowest point of the schism there were threemen claiming to be the true pope, and theologians, and indeed even figures who would later be recognized as saints, were divided on the issue. As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, “to contemporaries this problem [seemed]… almost insoluble.”

Further examples could easily be given, but these suffice to show that it is possible for grave prudential errors to persist for years. In comparison with the Cadaver Synod and the Great Western Schism, the hypothesis that recent popes have been mistaken in their prudential judgment that capital punishment is no longer necessary for the protection of society is actually pretty modest.

Now, if a mistake that persists even for decades wouldn’t count as “habitual” in the sense ruled out by Donum Veritatis, then what would count as “habitual” prudential error? For exactly how many years would the mistake have to persist? That’s a good question, but we needn’t give a precise answer for present purposes. We need only note that, since the Church is 2000 years old, we can be certain that a mistake that persists for 2000 years would count as “habitual” in the relevant sense. But that is precisely the kind of mistake that Prof. Fastiggi (not me!) thinks might be attributable to the Church. Indeed, he thinks the Church might have been wrong for that long about matters of moral principle and scriptural interpretation, and not merely about a prudential judgment. So, how Fastiggi can maintain a straight face while suggesting that heis somehow more loyal to the teaching of Donum Veritatis than I am, I have no idea. But I would certainly think twice before playing poker against him.

Then there is Prof. Fastiggi’s assertion – and sheer assertion is all that it is – that Pope St. John Paul II’s teaching on capital punishment was “much more than prudential.” Now, Joe Bessette and I devote over fifty pages of our book (pp. 144-196) to a careful analysis of the statements made on the subject of capital punishment by popes John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis. We address in detail all the arguments made by theologians who claim that the teaching of these popes counts as either a reversal or development of doctrine, and we show that those arguments fail. We do so in a sober and scholarly manner, in no way heaping any abuse on those who disagree with us. We claim to establish that the teaching of these popes is indeed nothing more than a prudential judgment that is not binding on Catholics.

Not one of the critics of our book who appeals to Pope St. John Paul II’s teaching has addressed these arguments. Hart and Griffiths assert that we are wrong, but do absolutely nothing to back up this assertion other than to fling insults. Brugger and Fastiggi, to their credit, do not resort to insult, but they too simply make undefended assertions, without answering the arguments in the relevant section of By Man. Since they offer no actual criticisms of those arguments, they really give me nothing to respond to. Suffice it to say that their silence speaks volumes.

Let’s move on to some of Prof. Fastiggi’s other comments. In my Catholic World Reportarticle I had also appealed to the teaching of Lumen Gentium 12, which says that the entire body of the faithful cannot err when they show universal agreement on a matter of faith and morals. Fastiggi responds:

Feser… fails, though, to mention that this universal agreement “is exercised under the guidance of the sacred teaching authority, in faithful and respectful obedience to which the people of God accepts that which is not just the word of men but truly the word of God.” This last sentence underlines the role of the magisterium in determining whether a teaching is definitive and infallible or whether it isn’t.

End quote. The first thing to say in response to this is that I certainly agree that the universal agreement of the faithful would have to be in harmony with the judgment of the magisterium. Indeed, that follows trivially from the fact that the magisterial authorities are themselves included among the faithful. So, I obviously wasn’t talking about a case where the body of the faithful think one thing and the magisterium thinks another. Rather, the universal agreement that I was speaking of, and that Lumen Gentium is speaking of, has to do with a situation where the magisterium and the faithful at large are all in agreement on some matter of faith and morals. And what I noted was that the magisterium and the faithful as a whole were for centuries in agreement on the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment. Therefore, given the teaching of Lumen Gentium, that teaching cannot be erroneous.

But Fastiggi seems to think that even this centuries-long agreement is irrelevant if it ever turns out that magisterial authorities at some future date decide to reverse a teaching. The trouble with this, though, is that it completely evacuates the teaching of Lumen Gentium 12 of any substantive content. On Fastiggi’s interpretation, the universal agreement of the faithful cannot be wrong… except when it is wrong, because some future pope decides to declareit wrong! And that makes the universal agreement of the faithful of no ultimate significance whatsoever. For it is really the judgment of whoever happens currently to be pope that determines, retroactively as it were, when the centuries-long universal agreement of the faithful really counts. In that case, though, Lumen Gentium might as well not have bothered mentioning the universal agreement of the faithful at all. If, however, Lumen Gentium was intended to make a substantive claim about the authority of the universal agreement of the faithful (which it surely was), then Fastiggi’s position must be rejected.

Fastiggi also writes:

Trying to determine which teachings are infallible by virtue of the ordinary and universal magisterium, however, is not any easy task. In his article, it would have been good for Feser to cite Lumen Gentium, 25, which notes that the ordinary and universal magisterium is infallible when the Catholic bishops “maintaining the bond of communion among themselves and with the successor of Peter, and authentically teaching matters of faith and morals, are in agreement on one position as definitively to be held.” This sets a very high standard, for it’s not so easy to verify whether the bishops, teaching in communion with the Roman Pontiff, have come to an agreement that one position (unam sententiam) on faith or morals must be definitively held.

End quote. The trouble with this, though, is that Fastiggi once again simply begs the question. In By Man, Joe Bessette and I point out (in response to Brugger, who makes the same mistake Fastiggi is making here) that Lumen Gentium 25 is in fact giving only sufficientconditions for the infallible exercise of the ordinary and universal magisterium, not necessaryconditions. Yes, when the bishops teach in communion with the pope in precisely the manner Lumen Gentium specifies, they are teaching infallibly. But it doesn’t follow that that is the only way that the ordinary and universal magisterium can teach infallibly, and indeed, the texts I cite in my Catholic World Report article show that it is not the only way. Fastiggi simply assumes, without argument, the contrary view.

The most serious problem with Fastiggi’s position, however, is enshrined in remarks like the following:

The magisterium itself is usually the best source for determining which teachings of the ordinary and universal magisterium are infallible and which are not. When subsequent popes show they are not bound by judgments of their predecessors, that’s a good indication that those judgments were not definitive…

If the magisterium in the future declares capital punishment – even under certain conditions – to be intrinsically evil, I’ll abide by the magisterium’s judgment. This would be an indication that there was no prior definitive magisterial teaching on the subject.

Similarly, in a later comment he writes:

The fact that Pope Francis and the overwhelming majority of bishops now reject capital punishment is a sign that there never was a definitive magisterial tradition on the matter.

End quote. The trouble with this, like the trouble with Fastiggi’s remarks about Lumen Gentium 12, is that it appears to imply a voluntarist or Orwellian conception of the papal magisterium. No matter what scripture, tradition, and previous popes all have said, for Fastiggi none of it has any binding authority if the current pope decides that it has no binding authority, and every previous scriptural and magisterial statement means whatever the current pope decides it means.

Now, one problem with this is that it is simply incompatible with what the Church herself teaches about the authority of popes. In By Man and elsewhere, I have cited many texts (from Vatican I, Vatican II, Pope Benedict XVI, etc.) showing that popes have no authority to introduce novel doctrines, to contradict scripture, to reject the unanimous scriptural interpretations of the Fathers, to assign novel meanings to dogmas, etc. As in the case of Lumen Gentium12, Fastiggi’s position essentially evacuates these texts of any substantive content. For Fastiggi, the pope cannot contradict scripture, tradition, or the consensus of his predecessors… but only because he can simply stipulate that whatever he wants to teach is, appearances notwithstanding, really in harmony with what scripture, tradition, and previous popes were teaching all along. He’s like the Party in 1984 (“We are at war with Eastasia. We have always been at war with Eastasia”). Obviously, this is not what texts like the ones I have cited are saying. Their point is precisely that “the Pope is notan absolute monarch whose thoughts and desires are law” (as Pope Benedict XVI taught).

Not only is Fastiggi’s apparent position contrary to the Catholic conception of papal authority, it also commits what logicians call the “No True Scotsman” fallacy. No matter what text from scripture, the Fathers, or previous popes you appeal to, Fastiggi will wave it off by saying that if Pope Francis or some future pope decides to contradict it, then the text in question must not really be binding after all, or must not really have meant what everyone has always taken it to mean. All possible counterevidence is simply redefined away.

A third and related problem is that this position completely destroys the credibility of papal authority by effectively conceding to its Protestant and atheist critics the caricature they typically present of it. Catholic apologists constantly have to explain to critics that the pope is not a dictator who can create doctrines by fiat, that he cannot contradict or reinterpret scripture at will, etc. Though I don’t think he intends this, Fastiggi’s position essentially entails that the critics are right and the apologists are wrong.

Let’s turn to this set of remarks by Prof. Fastiggi:

Since when is it a “cheap shot” to appeal to the authority of the Roman Pontiff over that of a private scholar?… I think Feser’s arguments are convincing to those who already favor capital punishment. They are not convincing to me and many others… Feser could shout “error” all he wants, but his shouts could never match the authority of the Catholic magisterium.

End quote. The first problem with this is that Fastiggi simply misrepresents the nature of the dispute between us. It seems that Fastiggi is so enamored of arguments from authority that he has forgotten that there is any other kind. Hence he proposes that what is in question is whether the authority of a “private scholar” like me trumps that of the Roman Pontiff. But that is not what is in question. It has nothing at all to do with my “authority” or lack thereof. Rather, the question is a purely logical one, namely: Can a reversal of past teaching on capital punishment be reconciled with what the Church claims about her own infallibility? I have shown that such a reversal logically cannot be reconciled with those claims. And Fastiggi says absolutely nothing to show otherwise. He simply changes the subject by throwing out the “private scholar” red herring.

It is also quite absurd to pretend that it is only “those who already favor capital punishment” who would find my arguments convincing. For one thing, this is simply an ad hominem fallacy of poisoning the well which, if it had any force at all, could with equal plausibility be turned against Fastiggi himself by suggesting that only those who already disapprove of capital punishment would agree with hisarguments.

For another thing, Fastiggi’s claim is, as a matter of empirical fact, easily shown to be false. In the very article to which Fastiggi is responding, I cited Archbishop Charles Chaput as an example of a churchman who is strongly opposed to capital punishment but who also agrees that the Church cannot teach that it is intrinsically immoral “without repudiating her own identity.” Cardinal Avery Dulles also held both that capital punishment should be abolished in practice and that traditional teaching cannot be reversed. Even Mark Shea, whose hostility to capital punishment and its defenders knows almost no bounds, has consistently admitted that the Church’s traditional teaching is irreversible.

But at the end of the day, this kind of stuff is a distraction from the main issue, which is this: If capital punishment were intrinsically evil, then the magisterium of the Church will have been teaching grave moral error and badly misunderstanding scripture for two millennia. And that would undermine the credibility of the Church. If she could be that wrong for that long about something that serious, why should we trust anything else she says?

I have repeatedly hammered on this point, and I find that my critics repeatedly avoid addressing it. They do not say either: “Yes, that’s true, but here’s why it’s not in fact a problem” or: “No, it’s not true, and here’s why.” They simply change the subject. For example, they accuse me of being bloodthirsty, or they quote from the catechism, or they bring up slavery or the slaughter of the Canaanites, or they bemoan the cold rationalism of Thomists, or they start ranting about Donald Trump and “Republican Rite Catholicism,” or in some other way they try to dodge the question of exactly how the Church could be trusted on any other subject if she had been teaching grave moral error and badly misunderstanding scripture for two millennia. I’d ask whythey try to dodge it, but I think I already know the answer.

The closest Fastiggi comes to addressing the problem is in the following brief remarks:

I think the 2,000 year tradition is something of a myth. Before Pope Innocent I’s permission in 405 for public officials to use torture and capital punishment there was nothing handed down in prior tradition (as Innocent I himself states). Some of the patristic sources cited by Feser and Bessette do not really show support for capital punishment (not even in principle).

But it is no myth. First, though Fastiggi asserts that there is “nothing” in the tradition before Innocent I, nothing could be further from the truth. For one thing, there are, of course, all the relevant scriptural passages, which no Catholic denied supported capital punishment at least in principle until very recently. For another thing, there are all the patristic texts Joe and I cite in our book and which I have cited in earlier responses to critics. Even if Fastiggi were correct that some of these do not really acknowledge that capital punishment is legitimate at least in principle – and he is not correct about that (and in any case he offers no argument for this claim) – there are other patristic texts that clearly do affirm this. So, again, the claim that there is “nothing” in the tradition before the year 405 is simply false.

Second, what Fastiggi would need in order to show that the 2000 year tradition I have been speaking of here is a “myth” is an example of a patristic writer who not only does not approve of capital punishment in practice (and I have never denied that some of the Fathers opposed it in practice) but who regards it as always and intrinsically evil even in principle. And there are no Fathers who hold that. Even Brugger admits that. Indeed, even Hart seems at the end of the day to admit that the Fathers do not regard the death penalty as contrary to natural law; his point is rather to emphasize that some of them regarded it as contrary to the higher demands of Christianmorality, specifically.

Third, for the specific purposes of my argument about the ordinary magisterium in my Catholic World Report article, what matters is not what this or that writer held in his capacity as a private theologian, but rather what magisterial authorities have said when, precisely in their capacity as magisterial authorities, they explicitly address the question of what is legitimate in principle for Christians. And even if we started just with Pope Innocent I, we have an unbroken 1600 year tradition where no pope condemned capital punishment as intrinsically immoral and many popes explicitly affirmed that it is legitimate at least in principle, even by the standards of specifically Christian morality.

So, even by Fastiggi’s lights, that would be a 1600-year-long error, if capital punishment turned out to be intrinsically wrong. Again, why he thinks an error of even 23 years “seems very problematical,” but an error of 1600years does not, I have no idea.

Published on January 25, 2018 20:04

January 20, 2018

The latest on Catholicism and capital punishment

Is there still anything left to say about the death penalty? Yes, plenty. In the debate generated by

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

, the focus has been on questions about the interpretation of various individual scriptural passages, and the level of authority of various papal statements considered in isolation. But the critics have failed to consider the sheer cumulative force of two millennia of consistent ordinary magisterial teaching. Some of them have also wrongly supposed that, even if capital punishment is legitimate under natural law, the higher demands of the Gospel might nevertheless rule it out absolutely. In a new article at Catholic World Report, I show that the ordinary magisterium has taught infallibly that the death penalty is legitimate in principle even as a matter of specifically Christian morality. No reversal is possible consistent with the indefectibility of the Church. There’s a fair amount of new material in the article that goes beyond what Joe Bessette and I say in the book.Meanwhile, in the letters section of the February issue of First Things, Joe and I reply to Paul Griffiths’ nasty and question-begging review of the book, and Griffiths responds by doubling down on the nastiness and begged questions.

Is there still anything left to say about the death penalty? Yes, plenty. In the debate generated by

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

, the focus has been on questions about the interpretation of various individual scriptural passages, and the level of authority of various papal statements considered in isolation. But the critics have failed to consider the sheer cumulative force of two millennia of consistent ordinary magisterial teaching. Some of them have also wrongly supposed that, even if capital punishment is legitimate under natural law, the higher demands of the Gospel might nevertheless rule it out absolutely. In a new article at Catholic World Report, I show that the ordinary magisterium has taught infallibly that the death penalty is legitimate in principle even as a matter of specifically Christian morality. No reversal is possible consistent with the indefectibility of the Church. There’s a fair amount of new material in the article that goes beyond what Joe Bessette and I say in the book.Meanwhile, in the letters section of the February issue of First Things, Joe and I reply to Paul Griffiths’ nasty and question-begging review of the book, and Griffiths responds by doubling down on the nastiness and begged questions.While you’re at it, take a look at Michael Pakaluk’s recent essay at Public Discourse criticizing the “new natural law” critique of capital punishment. Christopher Tollefsen replied to Pakaluk at PD, and Pakaluk then responded to Tollefsen at Facebook.

Published on January 20, 2018 20:19

January 14, 2018

Barron and Craig in Claremont (Updated again)

Last night at Claremont McKenna College, Stephen Davis and I moderated an exchange between Bishop Robert Barron and William Lane Craig. You can watch a video recording of the event at Bishop Barron’s Facebook page. (It looks like you don’t need to be signed in in order to view it.) Michael Uhlmann is the gentleman you'll see introducing the participants, and Joe Bessette and Brandon Vogt organized the whole thing. The event was sponsored by the Claremont Center for Reason, Religion, and Public Affairs, with the assistance of Bishop Barron’s Word on Fire Catholic Ministries and Prof. Craig’s Reasonable Faith.

Last night at Claremont McKenna College, Stephen Davis and I moderated an exchange between Bishop Robert Barron and William Lane Craig. You can watch a video recording of the event at Bishop Barron’s Facebook page. (It looks like you don’t need to be signed in in order to view it.) Michael Uhlmann is the gentleman you'll see introducing the participants, and Joe Bessette and Brandon Vogt organized the whole thing. The event was sponsored by the Claremont Center for Reason, Religion, and Public Affairs, with the assistance of Bishop Barron’s Word on Fire Catholic Ministries and Prof. Craig’s Reasonable Faith.UPDATE: Photos from the afternoon symposium have now been posted at Bishop Barron's Facebook page. The post also indicates that audio from the symposium will be posted soon. I will update this post again when it is.

UPDATE 1/17: Audio from the afternoon symposium has now been posted at the Word on Fire website (scroll down).

Published on January 14, 2018 10:04

January 8, 2018

Five Proofs on television and radio (Updated)

UPDATE 1/12: You can now watch the EWTN Live episode on YouTube or at the EWTN Live web page.

UPDATE 1/12: You can now watch the EWTN Live episode on YouTube or at the EWTN Live web page.This Wednesday, January 10, I will be on EWTN Live with Fr. Mitch Pacwa to discuss Five Proofs of the Existence of God . I will also be taping an episode of EWTN Bookmark for future airing.

Also forthcoming is an interview about the book on Lauren Green’s Lighthouse Faith at Fox News Radio.Other recent interviews about the book include those on The Ben Shapiro Show , The Andrew Klavan Show , The Dennis Prager Show , The Michael Medved Show , The Patrick Coffin Show , Pints with Aquinas with Matt Fradd , Unbelievable? with Justin Brierley , CrossExamined with Frank Turek , and many others. Further media appearances forthcoming. Stay tuned.

Published on January 08, 2018 18:06

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 331 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.