Edward Feser's Blog, page 57

March 30, 2018

Holy Triduum

I wish all my readers a holy Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Some Triduum-related posts from past years:

I wish all my readers a holy Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Some Triduum-related posts from past years: The meaning of the Passion

The meaning of the Resurrection

Putting the Cross back into Christmas

God’s wounds

Published on March 30, 2018 16:10

No hell, no heaven

As Aquinas teaches, Christ did not die to save the fallen angels, because they cannot be saved. They cannot be saved because their wills are locked on to evil. It is impossible for them to repent. It is impossible for them to repent because they are incorporeal, and thus lack the bodily preconditions for the changeability of the will’s basic orientation toward either good or evil. An angel makes this basic choice once and for all upon its creation. It is because we are corporeal that Christ can save us. But he can do so only while we are still in the flesh. Upon death, the soul is divorced from the body and thus, like an angel, becomes locked on to a basic orientation toward either good or evil. If it is not saved before death, it cannot be saved. It’s game over. I explained the reasons for all this in a post on the metaphysics of damnation.Now, there is an exact parallel with the condition of the saved. Theycannot be unsaved, and for the same reason. Their wills are locked on to good. It is impossible for them, after death, ever to fall away again into evil. You might say that that just is heaven, or what is fundamental to heaven. It is the impossibility of ever doing evil. It involves rewards beyond that, of course, but the rewards follow upon the fact that you are forever safe in only ever willing good, and thus can be forever worthy of such rewards.

As Aquinas teaches, Christ did not die to save the fallen angels, because they cannot be saved. They cannot be saved because their wills are locked on to evil. It is impossible for them to repent. It is impossible for them to repent because they are incorporeal, and thus lack the bodily preconditions for the changeability of the will’s basic orientation toward either good or evil. An angel makes this basic choice once and for all upon its creation. It is because we are corporeal that Christ can save us. But he can do so only while we are still in the flesh. Upon death, the soul is divorced from the body and thus, like an angel, becomes locked on to a basic orientation toward either good or evil. If it is not saved before death, it cannot be saved. It’s game over. I explained the reasons for all this in a post on the metaphysics of damnation.Now, there is an exact parallel with the condition of the saved. Theycannot be unsaved, and for the same reason. Their wills are locked on to good. It is impossible for them, after death, ever to fall away again into evil. You might say that that just is heaven, or what is fundamental to heaven. It is the impossibility of ever doing evil. It involves rewards beyond that, of course, but the rewards follow upon the fact that you are forever safe in only ever willing good, and thus can be forever worthy of such rewards. The parallel is so exact that you cannot deny hell without denying heaven. As Aquinas writes:

It was Origen's opinion [Peri Archon i. 6] that every will of the creature can by reason of free-will be inclined to good and evil; with the exception of the soul of Christ on account of the union of the Word. Such a statement deprives angels and saints of true beatitude, because everlasting stability is of the very nature of true beatitude; hence it is termed “life everlasting.”

If the wills of the damned could change after death, then so too could the wills of the saved. Thus, they wouldn’t truly be saved any more than the former would truly be damned. They would forever be in danger of falling again into evil and facing punishment for doing so. The travails and instability of this life would never end. Hence, no hell, no heaven either.

But doesn’t the parallel break down insofar as God could simply annihilate the damned souls while preserving those that are saved? No, and for two reasons. First, as I have argued elsewhere, there is a sense in which the damned perpetually choose to continue existing insofar as their will is locked, upon death, on a certain (evil) way of being, rather than on non-being. God gives everyone what he wants. It’s just that what the saved perpetually want is a way of being that is good and what the damned perpetually want is a way of being that is evil.

Second, there are consequences to getting what we want. It is often said that we damn ourselves, and that is true. But that is only part of the story, and as I have argued elsewhere, there is also a sense in which God really does damn us. For good and evil choices merit, respectively, rewards and punishments, so that just as someone who perpetually chooses good perpetually merits rewards, so too do those who perpetually will evil perpetually merit punishments. And in both cases, God ensures that this is exactly what they get. Again, the parallel between heaven and hell is exact.

This is just cold, hard metaphysical reality, and has nothing to do with what the defender of the doctrine of hell wants. Suppose there’s a fork in the road, the right side of which leads safely home and the left side of which leads to a yawning chasm. Suppose I veer left and you warn me to turn back before I drive off the cliff and meet a fiery end. It would be extremely bizarre if I responded to this friendly advice by accusing you of wantingme to die in such a crash, and insisted that if you really cared about me you would tell me that the left road too leads home, or at least will lead only to a minor and temporary inconvenience (a roadblock, say) rather than to death. The truth, of course, is that you want me not to be harmed and that that is precisely why you are warning me, and that if you were to tell me that a left turn would not lead to a fiery death you would be deceiving me and putting me in grave danger.

But blaming the messenger in this irrational way is precisely the reaction of many critics of the doctrine of hell. They accuse the defender of the doctrine of lacking mercy, and of wanting people to be damned. This is delusional, and as with the motorist who ignores all warnings and keeps speeding toward the cliff, it is a delusion that only increases the danger of calamity. But in neither case can the delusion last. The soul in danger, like the motorist in danger, will, one way or the other, realize eventually that the warnings were accurate. The only question is whether he finds out the easy way or the hard way.

Related posts:

How to go to hell

Does God damn you?

Why not annihilation?

A Hartless God?

Published on March 30, 2018 11:10

March 23, 2018

Bellarmine on capital punishment

In a recent Catholic World Report article supplementing the argument of

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

, I called attention to the consistent support for capital punishment to be found in the Doctors of the Church. (See the article for an explanation of the doctrinal significance of this consensus.) As I there noted, St. Robert Bellarmine is an especially important witness on this topic. For one thing, among all the Doctors, Bellarmine wrote the most systematically and at greatest length about how Christian principles apply within a modern political order, specifically. For another, he addressed the subject of capital punishment at some length, in chapters 13 and 21 of De Laicis, or the Treatise on Civil Government. What Bellarmine has to say strongly reinforces the judgment that the Church cannot reverse her traditional teaching that capital punishment is legitimate in principle (a judgment for which there is already conclusive independent evidence, as the writings referred to above show).A lot could be said about Bellarmine’s various lines of argument, but for the moment I will focus on just two points. (In what follows I quote from the Stefania Tutino translation of De Laicis in the new Liberty Fund volume of Bellarmine’s political writings.)

In a recent Catholic World Report article supplementing the argument of

By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed

, I called attention to the consistent support for capital punishment to be found in the Doctors of the Church. (See the article for an explanation of the doctrinal significance of this consensus.) As I there noted, St. Robert Bellarmine is an especially important witness on this topic. For one thing, among all the Doctors, Bellarmine wrote the most systematically and at greatest length about how Christian principles apply within a modern political order, specifically. For another, he addressed the subject of capital punishment at some length, in chapters 13 and 21 of De Laicis, or the Treatise on Civil Government. What Bellarmine has to say strongly reinforces the judgment that the Church cannot reverse her traditional teaching that capital punishment is legitimate in principle (a judgment for which there is already conclusive independent evidence, as the writings referred to above show).A lot could be said about Bellarmine’s various lines of argument, but for the moment I will focus on just two points. (In what follows I quote from the Stefania Tutino translation of De Laicis in the new Liberty Fund volume of Bellarmine’s political writings.) Absolute opposition to capital punishment is heretical

Early in De Laicis, Bellarmine makes the following striking remark:

Among the chief heretical beliefs of the Anabaptists and Antitrinitarians of our time there is one that says that it is not lawful for Christians to hold magistracy and that among Christians there must not be power of capital punishment, etc., in any government, tribunal, or court. (p. 5, emphasis added)

To understand the significance of this remark, several points have to be kept in mind. First, Bellarmine’s aim in this book is to address the topic of how Christian moral principles, specifically, apply to politics. He is not addressing questions about what might be merely theoretically possible under natural law considered apart from the Gospel. Second, Bellarmine is also concerned in the book to respond to the heretical movements of his day, and not merely to take a side in disputes between orthodox Catholics. Third, he classifies the thesis that capital punishment is contrary to Christian morality as a heresy, and not merely an error of some lesser sort. Nor is this an incidental remark. Again, he devotes two chapters to the subject, and what he has to say about it is theologically closely integrated with what he says about other topics (e.g. just war) and about Catholic political philosophy in general.

Furthermore, he has ample grounds for this judgment. He appeals first to scriptural evidence, including Genesis 9:6, Romans 13, and many other passages. Bellarmine explicitly considers and explicitly rejects a “proverbial” reinterpretation of Genesis 9:6, and among the points he makes is that such a reinterpretation is contrary to the traditional Jewish understanding of the passage. He points out that in the Targums the passage is paraphrased as: “Whoever sheds men’s blood before witnesses, by sentence of a judge his blood should be shed” (p. 49, emphasis added). The attempt to read opposition to capital punishment out of the Sermon on the Mount is one that Bellarmine characterizes as a heretical Anabaptist reading, and he cites Augustine, Chrysostom, Hilary, Aquinas, and Bonaventure against this reading.

Second, Bellarmine cites the teaching of the Fathers of the Church as evidence of the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment. He also cites papal teaching, specifically the teaching of Pope Innocent I and Pope Leo X. Finally, he cites the natural law. In short, Bellarmine’s defense of capital punishment is essentially of the same kind that Joe Bessette and I develop at greater length in the first two chapters of By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed.

Now, it won’t do for Catholics who claim that capital punishment is always and intrinsically immoral to dismiss Bellarmine’s remarks on the grounds that they are not infallible. First of all, Bellarmine is a Doctor of the Church, and a Doctor who specializes precisely in the bearing of Christian moral principles on matters of politics in the modern world. He is, in effect, recognized by the Church as someone uniquely qualified to advise Catholics on matters like the one in question. And again, his doctrine on capital punishment is not some incidental teaching, but instead is argued for systematically and integrated into the rest of his thought.

Second, Bellarmine makes the remark about the heretical nature of absolute opposition to capital punishment in a casual or matter-of-fact way. Evidently, he takes himself merely to be expressing the received wisdom on the matter among orthodox Catholics, not some controversial opinion of his own. And as the evidence cited in By Man and the CWR article linked to above demonstrate, he was absolutely correct to do so.

So, to dismiss Bellarmine on this issue is to claim that a Doctor of the Church who specialized in such matters – not to mention all the other authorities he cites, and the centuries-old teaching of the Church – got it wrong, and that the heretics he opposed were right all along.

I submit that this is not possible if the claims the Catholic Church makes about her own authority are true. There are cases in Church history where a teaching once regarded as optional was later regarded as a requirement of orthodoxy. But there is no case where a teaching once regarded as heretical was later regarded as orthodox. And it would be a major problem if there were such a case, given what the Church claims about the reliability of the ordinary magisterium. (And no, slaveryand religious liberty are not counterexamples.)

The apostles didn’t play games

In another striking passage, Bellarmine writes:

[I]n Acts 5 Peter killed Ananias and Sapphira because they dared to lie to the Holy Spirit, while in Acts 13 Paul punished with blindness a false prophet who tried to turn a proconsul away from the faith. (p. 104)

I say this is “striking,” but actually I don’t think that this passage (or for that matter, the earlier passage describing absolute opposition to capital punishment as heretical) would have been at all striking to the Catholic readers of Bellarmine’s time. It is striking to modern readers, who are so used to thinking of violence of any kind as extremely morally problematic at best that the idea of an apostle inflicting it seems to them unfathomable.

Now, a critic might quibble about whether it is accurate to say that Peter – as opposed to God – killed Ananias and Sapphira. But Bellarmine’s reading is by no means idiosyncratic. Though the deaths of the pair are directlycaused by God, Peter clearly plays an instrumental role. As the Catholic Encyclopedia says:

When Ananias and Sapphira attempt to deceive the Apostles and the people Peter appears as judge of their action, and God executes the sentence of punishment passed by the Apostle by causing the sudden death of the two guilty parties. (Emphasis added)

Even if it were argued that in fact Peter merely witnessed, rather than in any way caused, Ananias’s death, it is difficult to make the same argument with respect to Sapphira’s death. Acts tells us:

After an interval of about three hours [Ananias’s] wife came in, not knowing what had happened. And Peter said to her, “Tell me whether you sold the land for so much.” And she said, “Yes, for so much.” But Peter said to her, “How is it that you have agreed together to tempt the Spirit of the Lord? Hark, the feet of those that have buried your husband are at the door, and they will carry you out.” Immediately she fell down at his feet and died.

Clearly, Peter is testing Sapphira here, and on finding her guilty pronounces that she will die just as Ananias did. Even if it were suggested that Peter is merely predictingwhat will happen, he knows full well what fate Sapphira faces if she says the wrong thing. He doesn’t warn her, doesn’t beg her to repent, and doesn’t fret over the affront to her dignity as a human person after she drops dead. Nor can it be maintained that Peter showed thereby that he didn’t understand the Gospel as well as we do. For it is God who strikes Sapphira down on the occasion of Peter’s testing of her, where Peter fully expects God to do this. That is a kind of divine seal of approval on Peter’s action. The Holy Spirit doesn’t make of this a “teaching moment,” by which Peter might be brought to a deeper understanding of mercy. Rather, He simply summarily inflicts on Sapphira exactly the punishment that Peter anticipates and thinks she deserves.

Something similar can be said of the action of St. Paul cited by Bellarmine. Acts tell us:

[T]he proconsul, Sergius Paulus, a man of intelligence… summoned Barnabas and Saul and sought to hear the word of God. But Elymas the magician (for that is the meaning of his name) withstood them, seeking to turn away the proconsul from the faith. But Saul, who is also called Paul, filled with the Holy Spirit, looked intently at him and said, “You son of the devil, you enemy of all righteousness, full of all deceit and villainy, will you not stop making crooked the straight paths of the Lord? And now, behold, the hand of the Lord is upon you, and you shall be blind and unable to see the sun for a time.” Immediately mist and darkness fell upon him and he went about seeking people to lead him by the hand. Then the proconsul believed, when he saw what had occurred, for he was astonished at the teaching of the Lord.

Though not a capital sentence, this is pretty harsh stuff. Paul does not warn this false prophet to repent (much less initiate ecumenical dialogue with him or the like). He strikes him blind. Nor can it be maintained that Paul didn’t understand the Gospel and its call to mercy as well as we do, for Acts tells us that Paul “was filled with the Holy Spirit,” and of course it is Godwho miraculously carries out Paul’s sentence. Here too we have a divine seal of approval on a harsh action, rather than a divine rebuke of it.

Clearly, St. Peter, St. Paul, and St. Robert Bellarmine (not to mention all the other saints I’ve cited elsewhere in connection with this subject) were not men likely to get weepy at the execution of sadistic perverts like Ted Bundy or John Wayne Gacy. Somebody has gotten the demands of Christian morality wrong, but why should we suppose it is them?

Published on March 23, 2018 11:51

March 13, 2018

Divine causality and human freedom

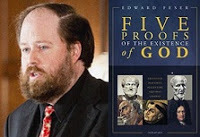

Is the conception of divine causality defended by classical theists like Aquinas (and which I defend in

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

) compatible with our having free will? The reason they might seem not to be compatible is that for Aquinas and those of like mind, nothing exists or operates even for an instant without God sustaining it in being and cooperating with its activity. The flame of a stove burner heats the water above it only insofar as God sustains the flame in being and imparts causal efficacy to it. And you scroll down to read the rest of this article only insofar as God sustains you in being and imparts causal efficacy to your will. But doesn’t this mean that you are not free to do otherwise? For isn’t it really God who is doing everything and you are doing nothing?No, that doesn’t follow at all. Keep in mind, first of all, that Aquinas’s position is

concurrentist rather than occasionalist

. The flame really does heat the water, even if it cannot do so without God’s cooperation. You might say that God is in this way like the battery that keeps a toy car moving. The car’s motor really does move the wheels even if it cannot do so without the battery continually imparting power to it. It’s not that the battery alone moves the wheels and the motor does nothing. Similarly, it is not God alone heating the water. The flame, like the motor, makes a real contribution. Now, in voluntary action, the human will also makes a real contribution. It is not that God causes our actions and we do nothing. We really are the cause of them just as the flame really causes the water to boil, even if in both cases the causes act only insofar as God imparts efficacy to them.

Is the conception of divine causality defended by classical theists like Aquinas (and which I defend in

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

) compatible with our having free will? The reason they might seem not to be compatible is that for Aquinas and those of like mind, nothing exists or operates even for an instant without God sustaining it in being and cooperating with its activity. The flame of a stove burner heats the water above it only insofar as God sustains the flame in being and imparts causal efficacy to it. And you scroll down to read the rest of this article only insofar as God sustains you in being and imparts causal efficacy to your will. But doesn’t this mean that you are not free to do otherwise? For isn’t it really God who is doing everything and you are doing nothing?No, that doesn’t follow at all. Keep in mind, first of all, that Aquinas’s position is

concurrentist rather than occasionalist

. The flame really does heat the water, even if it cannot do so without God’s cooperation. You might say that God is in this way like the battery that keeps a toy car moving. The car’s motor really does move the wheels even if it cannot do so without the battery continually imparting power to it. It’s not that the battery alone moves the wheels and the motor does nothing. Similarly, it is not God alone heating the water. The flame, like the motor, makes a real contribution. Now, in voluntary action, the human will also makes a real contribution. It is not that God causes our actions and we do nothing. We really are the cause of them just as the flame really causes the water to boil, even if in both cases the causes act only insofar as God imparts efficacy to them.A critic might respond that that is all well and good, but while Aquinas’s position avoids occasionalism, that does not suffice to save free will. The flame really does heat the water, but it does not do so freely. So if divine cooperation with the will is like divine cooperation with the flame, how is the will any more free than the flame is?

The answer is that God’s cooperation with a thing’s action does not change the nature of that action. Impersonal causes act without freedom because they are not rational. Human beings act freely because they are rational. That God cooperates with each sort of action is irrelevant. Suppose, per impossibile, that you and the flame could exist and operate without God’s conserving action. Then there would be no question that whereas the flame does not act freely, you do, because you are rational. There would in this scenario be no additional divine causal factor that might seemto detract from your freedom.

Of course, this scenario is impossible. Again, for the Thomist, neither the flame nor your will could exist or operate for an instant without divine conservation and concurrence. But the point of the per impossibile scenario is to emphasize that God is not some additional causal factor within the universe the presence or absence of which might affect the specific causal situation in the waythat the presence or absence of oxygen would affect the flame’s causal efficacy, or the presence or absence of temptations and other distractions would affect your will’s causal efficacy. Rather, God is the metaphysical precondition of there being any causality at all, whether causality of the unfree kind or of the voluntary kind.

Here’s an analogy. Consider a triangle you’ve drawn with a ruler on notebook paper. What you’ve drawn has straight sides. Why? One answer is: because you used a ruler to draw it. Another answer is: because it instantiates triangularity. These answers are, of course, in no way in competition. Indeed, both answers are true. Each explains a different aspect of the situation.

Now, the relation of our actions to the will’s causality and to divine causality, respectively, is somewhat like that. Why did you scroll down the page to read the rest of this article? One answer is: because you freely chose to do so. Another answer is: because God has created a world in which that happens. These answers too are in no way in competition. Both are true, and both explain a different aspect of the situation.

In Five Proofs, I deploy another analogy, between God and the world on the one hand and an author and the story he has written on the other. Suppose you finish a detective novel, find out that the butler did it, and then complain to a friend that you were troubled that the butler was punished at the end of the book, because he didn’t act of his own free will. Your friend responds: “Oh, was the butler acting under threat from someone else in the story? Was he acting under the influence of hypnosis or some other kind of mind control? Did he go temporarily insane? Did he squeeze the trigger only because of a muscle spasm?” You respond: “No, nothing like that. It’s just that I found out after reading it that the novel had an author! That means that the butler didn’t act freely after all, since he only did it because the author wrote the story that way.”

That would be a silly comment, of course. The author’s causal relation to the butler’s actions is simply not like the causal relation that a threat, or hypnosis, or insanity, or a muscle spasm might have to the butler’s actions. The author is not one causal element of the story among others, but rather the precondition of there being any story, and any causality within it, at all. Similarly, God is not one causal factor among others within the universe, but rather the precondition of there being any universe, and any causality within it, at all.

Of course, like any analogy, this one is imperfect. But a critic might claim that it nevertheless fails to illuminate the compatibility of free will and divine causality, even given the limitations facing any analogy. For the bottom line, the critic might say, is that absolutely nothing happens in the story that doesn’t happen because the author wrote it that way. And for the Thomist, absolutely nothing happens in the world that doesn’t happen because God simply created a world where it happens. So (the critic concludes) neither the characters in the story nor the human beings who exist in reality (at least as the Thomist conceives of reality) ever really act freely. The story analogy, the critic might claim, really exacerbates the problem for the Thomist rather than solves it. For it shows that human beings are really no more free than characters in a story are.

But on careful analysis this objection can be seen to have no force, for it doesn’t treat the different elements of the story analogy in a consistent way. If such a critic were consistent, then he would also have to say that the gun that the butler used didn’t really fire any bullets, that the bullets are not really what killed the victim, that the judge and jury didn’t really punish the butler, etc. – all on the grounds that it was really the author who did all these things, since, after all, he was the one who wrote the story that way.

Of course, this too would be silly. To understand and describe a story at all, we have to treat it as if it were real. For example, we have to speak of the characters and events in the story as if they really existed and occurred. But if we are going to do that much, then to be consistent, we also have to speak of the characters and physical objects in the story (e.g. the gun, bullets, etc.) as if they had real efficacy. That is to say, we have to speak of the gun as if it really fired bullets, of the bullets as if they really tore into the victim’s body, of the judge and jury as if they really punished the butler, and so on.

But by the same token, to be consistent, we alsohave to speak of the butler and other characters as if they acted freely. We can’t have it both ways. If we are correctly to understand and describe the story at all, we have to treat every part of it, including the free will of the characters, as if it were real. It is silly to pretend that the fact that the story had an author gives us special reason to think that the free will of the characters, specifically, is unreal. Of course the free will of the characters is unreal. Everythingin the story is unreal, because it’s only a story. There’s nothing special about the characters’ free will in this regard. If a critic were to claim that the story analogy shows that Thomism undermines free will, he might as well claim that the story analogy shows that Thomism leads to occasionalism, on the grounds that it is really the author and not the butler who fired the gun, etc.

The story analogy shows no such thing, of course. But then, neither does it in any way undermine free will. It can seem to do so only given a selective treatment of the different elements of the analogy.

The critic might at this point try a different tack. He may say that the Thomist account of free will is problematic. Again, Aquinas takes the will to be free because it is a rational appetite. Human beings, unlike lower animals, act in light of what their intellects take to be good. But, the critic might ask, why does this matter? Suppose your intellect judges that it would be good to read the rest of this article, and so you choose to do so and scroll down to keep reading. How would this make your action free? Indeed, wouldn’t this act of the intellect simply be one further member of the series of causes that led to your action, in no relevant respect different from the neural firing patterns and muscular contractions that play a role in it?

There are two main points to be made in response to this. The first is that it is hard to see why any critic would think this a serious objection to the Thomist unless he conceived of causality entirely in terms of efficient causal relations. In particular, such a critic would be supposing that the way to understand the role of the intellect is to think in terms of some specific mental event (identified either with a neural event or with something going on in a Cartesian res cogitans) functioning as the efficient cause of some chain of bodily events, where said mental event was itself in turn the effect of some preceding series of efficient causes. The critic’s objection would be that such a mental event seems to be merely one further member of the series of events that led to the action, each of which might for all Aquinas has shown be as causally determined as any other.

The problem with such an objection, of course, is that it simply takes for granted a view of causality that no Thomist would accept. For the Thomist, there are four irreducible modes of causal explanation – formal, material, efficient, and final – and the role of the intellect is primarily to be understood in terms of formal and final causality rather than in terms of efficient causality. Furthermore, the Thomist would, for that matter, also reject the reductionist and physicalist assumptions about efficient causality that inform much contemporary discussion of causality and free will. Objections like the one I have put into the mouth of my imagined critic simply read into Aquinas assumptions that he would not accept, and thus beg the question.

The second thing to be said in response to this imagined objection is that it changes the subject. For if the critic’s problem is with Aquinas’s account of free will as a consequence of intellect, then it isn’t any longer divine causality that is at issue.

Much more could be said, but for now I’ll end with this: Misgivings about Aquinas’s account of divine causality and free will seem largely to derive from two errors. The first involves reading into Aquinas modern philosophical assumptions about free will and causality that he would not accept, the result of which is a travesty of what he actually thinks about the nature of free will. (Hence all the heavy going about whether Aquinas was a compatibilist, a libertarian, etc. I don’t think he is properly understood in terms of any of the categories that have now become standard, any more than his views on the mind-body problem are properly classified as Cartesian, materialist, functionalist, etc.) The second error involves treating God as if he were simply one further efficient cause alongside all the others in the universe, only more powerful and further back in the line of efficient causes.

Published on March 13, 2018 19:54

March 9, 2018

The missing links

Feedspot has released its list of the Top 15 Christian Philosophy Blogs and Websites. This blog is ranked at #1. Thank you, Feedspot!

Feedspot has released its list of the Top 15 Christian Philosophy Blogs and Websites. This blog is ranked at #1. Thank you, Feedspot! At Public Discourse, Fr. Nicanor Austriaco responds to Fr. Michael Chaberek’s book on Thomism and evolution.

At First Things, Matthew Rose on Christianity and the alt-right.

Philosophers Jonathan Ellis and Eric Schwitzgebel argue that philosophers are as prone to post-hoc rationalization as anyone else.Bishop Robert Barron and William Lane Craig each comment on their recent exchange at Claremont McKenna College. Brian Huffling of Southern Evangelical Seminary comments on Craig’s critique of divine simplicity.

Also at Public Discourse, Matthew Franck reviews Ryan Anderson’s new book When Harry Became Sally: Responding to the Transgender Moment . Anderson offers a précis of the book.

The Times Literary Supplement on the religion of Isaac Newton.

Comics writer Mark Millar on why Marvel movies work and DC movies don’t. Kevin Feige notes that, even if the deal with Fox goes through, not all of Marvel’s characters will have “come home” to the company.

At Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Jerry Walls reviews Adrian Reimers’ book Hell and the Mercy of God .

Philosopher Christopher Kaczor critiques a recent defense of abortion, at Public Discourse.

Gil Sanders develops an Aristotelian approach to quantum mechanics.

In Los Angeles, the Thomistic Institute recently hosted a lecture by John Haldane on the theme “Darkness in the City of Angels: Evil as a Theme and Vice as a Fact.” You can listen to it via Soundcloud.

Eyjólfur Emilsson’s new book on Plotinus is reviewed by Luc Brisson at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews.

Catholic University of America philosopher John Rist challenges Cardinal Cupich and judges Pope Francis to be “possibly the worst pope we have ever had.” At First Things, Cardinal Müller on “paradigm shifts” and the development of doctrine. At the Catholic Herald, Damian Thompson looks back on Pope Benedict XVI’s resignation.

At the Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective, philosopher Christopher Brown critiques scientism.

National Review really likes, doesn’t like, and sort of likes Black Panther.

Stephen L. Talbott on evolution and the purposes of life, at The New Atlantis.

Speaking of paradigm shifts: the Times Literary Supplement on Thomas Kuhn’s philosophy of science.

Alex Rosenberg is interviewed at What Is It Like to Be a Philosopher?

At The Catholic Thing, philosopher Michael Pakaluk on contraception and intrinsically evil acts.

Michael Ruse’s Darwinism as Religion is reviewed at the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Published on March 09, 2018 10:05

March 5, 2018

Carrier carries on

Richard Carrier has replied to my recent response to his critique of

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

, both in the comments section of his original post and in a new post. “Feser can’t read,” Carrier complains. Why? Because – get this – I actually took the first six paragraphs of the section he titled “Argument One: The Aristotelian Proof” to be part of his response to the Aristotelian proof. What wasI thinking?It’s all at about that level. Trash talk, unacknowledged backpedaling, rookie misinterpretations of Thomistic claims, misrepresentations of what I said, question-begging scientism, persistent missing of the point, all expressed in prose with the flow and clarity of tar. It would take a second book to explain all the ways Carrier gets the first one wrong. Several readers have begged me not to engage with him any further, on the grounds that it would manifestly be a waste of time to do so. And they are right.

Richard Carrier has replied to my recent response to his critique of

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

, both in the comments section of his original post and in a new post. “Feser can’t read,” Carrier complains. Why? Because – get this – I actually took the first six paragraphs of the section he titled “Argument One: The Aristotelian Proof” to be part of his response to the Aristotelian proof. What wasI thinking?It’s all at about that level. Trash talk, unacknowledged backpedaling, rookie misinterpretations of Thomistic claims, misrepresentations of what I said, question-begging scientism, persistent missing of the point, all expressed in prose with the flow and clarity of tar. It would take a second book to explain all the ways Carrier gets the first one wrong. Several readers have begged me not to engage with him any further, on the grounds that it would manifestly be a waste of time to do so. And they are right.Except for this: Carrier’s self-confidence is soabsurdly out of proportion to his actual competence that he does not realize that the only deathblows he delivers are of the self-inflicted kind. In particular, in no fewer than three places in his response, Carrier has inadvertently revealed himself to be either an extremely reckless liar or guilty of malpractice that would make any actual scholar (as opposed to the online hobbyist Carrier is) a professional laughingstock.

No honest and objective Carrier reader who considers the examples that follow can have any further doubt (if any still remained) that Carrier has no credibility and should not be taken seriously, certainly not on the subject of Five Proofs. Establishing that, as I think all my readers will agree, is worth one more post on Carrier. So let’s get to it.

Exhibit A:

In my initial response, I pointed out that the apparent force of one of Carrier’s objections rested in part on his conflation of two separate premises from my Aristotelian proof. In his latest post, Carrier responds as follows:

I won’t address every weird and false thing Feser says about my article. There are many. But, for example, Feser falsely claims I collapsed two premises into one when addressing his Aristotelian argument. Nope. I quote only Premise 41, exactly as he wrote it, verbatim. (Emphasis added)

End quote. Now, why Carrier would bother making so easily refutable an assertion, I have no idea, but there it is. Let’s now compare what he actually said in his original post with what I actually said in my book. Here is the relevant passage from Carrier’s original post:

Feser’s formalization of this argument appears around page 35. It has 49 premises. I shit you not. Most of them are uncontroversial on some interpretation of the words he employs (that doesn’t mean they are credible on his chosen interpretation of those words, but I’ll charitably ignore that here), except one, Premise 41, where his whole argument breaks down and bites the dust: “the forms or patterns manifest in all the things [the substrate] causes…can exist either in the concrete way in which they exist in individual particular things, or in the abstract way in which they exist in the thoughts of an intellect.” (Emphasis added)

End quote. And here is the passage from my book that he is quoting from, at p. 37:

40. So, the forms or patterns manifest in all the things it causes must in some way be in the purely actual actualizer.

41. These forms or patterns can exist either in the concrete way in which they exist in individual particular things, or in the abstract way in which they exist in the thoughts of an intellect.

End quote. As you can plainly see, Carrier really did do exactly what I said he didand what he now strenuously denies doing – he collapsed steps 40 and 41 into one step without telling the reader that that is what he was doing. (See my previous response to Carrier for an explanation of why this is significant.) Anyone who actually has a copy of my book and reads Carrier’s original review can easily check and see that I am telling the truth and Carrier is not. (By the way, as a precaution, I took a screen capture of this Carrier passage and the ones to follow. I will post these if Carrier attempts to go back and doctor his original posts by way of damage control.)

Exhibit B:

In his latest post, Carrier writes:

His attempt to defend his Aristotelian argument against my rebuttal illustrates this very point: he falsely claims I argued that he did not consider Platonism; false. I said he did not consider Aristotelian Forms Theory, not Platonic Forms Theory. And lo, he didn’t. Nowhere in his book.And still not even in this response to my rebuttal. It’s almost like he does not comprehend there is a difference between those two theories or what it is. (Emphasis added)

End quote. Yes, you read that right. Carrier actually asserts that “nowhere” in my book do I “consider Aristotelian Forms Theory,” and that it seems that I do not even “comprehend that there is a difference between those two theories or what it is.” Anyone with even a cursory knowledge of my work will find this an absolutely bizarre claim, given that one of the things for which I am best known is, of course, being an unreconstructed Aristotelian hylemorphist. For example, I devote a whole chapter of Scholastic Metaphysics and big chunks of Aquinas , The Last Superstition , and other works to defending the Aristotelian approach to form.

More to the present point, I do in fact explicitly address the topic several times in Five Proofsitself. For example, at p. 97 I write: “There are three alternatives: Platonic realism, Aristotelian realism , and Scholastic realism. Let’s consider each in turn.” I then go on to do exactly that from pp. 97-102. Earlier in the book, at pp. 28-29, I explicitly discuss the Aristotelian hylemorphist analysis of material substances as composites of substantial form and prime matter. I discuss it again at pp. 55-56, 72-73, and elsewhere in the book.

Again, anyone who has a copy of my book can easily verify that I am telling the truth and Carrier is not. (And again, I’ve taken a screen capture in case Carrier decides to alter what he wrote in order to save himself from embarrassment.)

Exhibit C:

In a combox remark under his original post, a reader asks Carrier if my book “argue[s] for the Judeo-Christian God or just a generic diety [sic] he calls God.” Carrier responds:

His closing chapters attempt to bootstrap his way to a traditional Christian God of some sort , by building on his five Proofs (which alone don’t get that far). But since his Five Proofs don’t work, there was no need to bother addressing his attempts to build on them. One could perhaps write a critique of just how he gets from the God of his Proofs, all the way to Christianity, but I found that a tedious waste of time. His Proofs are false. So why bother exploring what else he does with them? (Emphasis added)

End quote. Now, as anyone who has read Five Proofs knows, in fact not only do I not address any specifically Christian claims in the book, I explicitly decline to do so. For example, at p. 15, I write:

The real debate is not between atheism and theism. The real debate is between theists of different stripes – Jews, Christians, Muslims, Hindus, purely philosophical theists, and so forth – and begins where natural theology leaves off. This book does not enter into, much less settle, that latter debate. (Emphasis added)

End quote. On pp. 268-9 I consider the following objection:

“Even if it is proved that there is a First Cause, which is omnipotent, omniscient, perfectly good, and so forth, this would not by itself show that God sent prophets to ancient Israel, inspired the Bible, is a Trinity, and so forth.”

And then in response, I write:

This is true, but completely irrelevant. Arguments like the ones defended in this book are not claiming in the first place to establish every tenet of any particular religion, but rather merely one central tenet that is common to many of them – namely, that there is a cause of the world which is one, simple, immaterial, eternal, immutable, omnipotent, omniscient, perfectly good, and so forth. If they succeed in doing that, then they show that atheism is false, and that the only remaining question is what kind of theism one ought to adopt – a purely philosophical theism, or Judaism, or Christianity, or Islam, or some other more specific brand of theism. Deciding that would require further investigation and argumentation. It would be silly to pretend that since the arguments of this book don’t answer every question about God, it follows that they don’t answer any question about God. (Emphasis added)

End quote. Once again, anyone who has a copy of my book can easily verify that I am telling the truth and Carrier is not.

Since Carrier cannot get even simple matters like theseright, it is no surprise that he horribly mangles the more complex topics he addresses. For example, he clearly hasn’t the faintest clue as to what Thomists and other classical theists mean when they attribute simplicity or intellect to God. But that doesn’t stop him from devoting paragraph after turgid paragraph to developing objections that intersperse these misunderstandings with completely irrelevant blathering about the nature of space-time. Then he declares victory when I don’t follow him on this wild goose chase.

If you’ve ever gotten stuck at a party sitting next to some bore who won’t shut up about the Trilateral Commission, or UFOs, or some other crackpot subject, and thinks he’s scored some major points because you’ve simply nodded politely and then beat a hasty retreat without having rebutted his assertions, then you have an idea of what it’s like to engage in an online exchange with Richard Carrier. The guy badly needs someone to take him aside and offer some bracing maternal advice.

Published on March 05, 2018 18:43

March 4, 2018

It’s the latest open thread

It’s your opportunity once again to converse about anything that strikes your fancy. From film noir to The Cars, Freud to cigars, set theory to dive bars. As always, keep it civil, keep it classy, no trolling or troll-feeding.

It’s your opportunity once again to converse about anything that strikes your fancy. From film noir to The Cars, Freud to cigars, set theory to dive bars. As always, keep it civil, keep it classy, no trolling or troll-feeding. Previous open threads linked to here, if memory lane is your thing.

Published on March 04, 2018 10:17

March 1, 2018

Hart on Five Proofs

At Church Life Journal, David Bentley Hart kindly reviews

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. From the review:

At Church Life Journal, David Bentley Hart kindly reviews

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. From the review:Edward Feser has a definite gift for making fairly abstruse philosophical material accessible to readers from outside the academic world, without compromising the rigor of the arguments or omitting challenging details… Perhaps the best example of this gift in action hitherto was his 2006 volume Philosophy of Mind: A Beginner’s Guide (at least, speaking for myself, I have both recommended it to general readers and used it with undergraduates, in either case with very happy results). But this present volume is no less substantial an achievement…It is also a virtue on Feser’s part that the only God he cares to argue foris the God of “classical theism.” He does not waste any attention on debates (of the kind all too depressingly common in Anglophone philosophy of religion) over the possible reality of a single “supreme being” who exists alongside other, lesser beings, on the same ontological plane (so to speak), and set off from them only by virtue of his “maximal greatness,” or some other property that makes him far larger and far older than all other things. Feser clearly grasps that, even if one could prove that such a being exists, this would bring us no nearer to an understanding of the true source of all reality (which for monotheists, presumably, is what the word “God” ideally refers to), but would merely provide us with one more entity whose existence must be accounted for…

The third argument Feser calls the “Augustinian” proof; it proceeds from the reality of universals, propositions, abstract truths, logical possibilities, and so forth, to that reality in which all these things must necessarily subsist: which (so the argument at last concludes) must be the divine intellect… Feser manages to bring out the logical force of this approach better than most of its other expositors…

In sum, Feser’s is an admirable achievement, and this book can be recommended for the classroom quite vigorously – but also, happily, not onlyfor the classroom. It accomplishes much in a fairly compact space, and does so with exemplary clarity. In fact, it is among the best such volumes currently available in English.

End quote. I thank Prof. Hart for his very kind words. Hart also raises a couple of minor but useful criticisms, which I may address in a future post. As they say, read the whole thing.

Published on March 01, 2018 16:00

February 28, 2018

The Oxford Handbook of Freedom

My essay “Freedom in the Scholastic Tradition” appears in

The Oxford Handbook of Freedom

, edited by David Schmidtz and Carmen Pavel and just out from Oxford University Press. The other contributors to the volume are Elizabeth Anderson, Richard Arneson, Ralf M. Bader, David Boonin, Jason Brennan, Allen Buchanan, Mark Bryant Budolfson, Piper L. Bringhurst, Kyla Ebels-Duggan, Gerald Gaus, Ryan Patrick Hanley, Michael Huemer, David Keyt, Frank Lovett, Fred D. Miller Jr., Elijah Millgram, Eddy Nahmias, Serena Olsaretti, James R. Otteson, Orlando Patterson, Carmen E. Pavel, Mark Pennington, Daniel C. Russell, David Sobel, Hillel Steiner, Virgil Henry Storr, Steven Wall, and Matt Zwolinski.More information about the volume can be found at the OUP webpage and at the Oxford Handbooks Online page.

My essay “Freedom in the Scholastic Tradition” appears in

The Oxford Handbook of Freedom

, edited by David Schmidtz and Carmen Pavel and just out from Oxford University Press. The other contributors to the volume are Elizabeth Anderson, Richard Arneson, Ralf M. Bader, David Boonin, Jason Brennan, Allen Buchanan, Mark Bryant Budolfson, Piper L. Bringhurst, Kyla Ebels-Duggan, Gerald Gaus, Ryan Patrick Hanley, Michael Huemer, David Keyt, Frank Lovett, Fred D. Miller Jr., Elijah Millgram, Eddy Nahmias, Serena Olsaretti, James R. Otteson, Orlando Patterson, Carmen E. Pavel, Mark Pennington, Daniel C. Russell, David Sobel, Hillel Steiner, Virgil Henry Storr, Steven Wall, and Matt Zwolinski.More information about the volume can be found at the OUP webpage and at the Oxford Handbooks Online page.

Published on February 28, 2018 18:18

February 24, 2018

Carrier on Five Proofs

In an article at his blog, pop atheist writer Richard Carrier grandly claims to have “debunked!” (exclamation point in the original)

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. It’s a bizarrely incompetent performance. To say that Carrier attacks straw men would be an insult to straw men, which usually bear at least a crude resemblance to the argument under consideration. They are also usually at least intelligible. By contrast, consider this paragraph from the beginning of Carrier’s discussion of the Aristotelian proof:Really, the most nothingly nothing you can have without facing a logical contradiction, is the absence of everything except logically contradictory states of affairs. And that means everything. Including gods, laws of physics, rules, objects, minds, or extensions of space or time. And by Feser’s own reasoning, the absence of everything except logically contradictory states of affairs entails the presence of every logically necessary thing. And nothing else. The absence of everything but logical contradictions is the same thing as the presence of only the logically necessary. Since if some entity’s existence is logically necessary, by definition its absence would entail a logical contradiction. That’s literally what “logically necessary” means.

In an article at his blog, pop atheist writer Richard Carrier grandly claims to have “debunked!” (exclamation point in the original)

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. It’s a bizarrely incompetent performance. To say that Carrier attacks straw men would be an insult to straw men, which usually bear at least a crude resemblance to the argument under consideration. They are also usually at least intelligible. By contrast, consider this paragraph from the beginning of Carrier’s discussion of the Aristotelian proof:Really, the most nothingly nothing you can have without facing a logical contradiction, is the absence of everything except logically contradictory states of affairs. And that means everything. Including gods, laws of physics, rules, objects, minds, or extensions of space or time. And by Feser’s own reasoning, the absence of everything except logically contradictory states of affairs entails the presence of every logically necessary thing. And nothing else. The absence of everything but logical contradictions is the same thing as the presence of only the logically necessary. Since if some entity’s existence is logically necessary, by definition its absence would entail a logical contradiction. That’s literally what “logically necessary” means.End quote. If, after fewer than two or three readings, you have the remotest idea what the hell Carrier is going on about here, you are a sharper man than I am. Certainly it has nothing at all to do with the Aristotelian proof. Yet Carrier goes on for paragraph after paragraph of this gobbledygook.

As near as I can tell after reading and rereading those mind-numbingly obscure passages, what Carrier is criticizing is an argument that tries to show that God is the cause of the universe arising from nothing. And as near as I can tell, his objection is something to the effect that if we think carefully about what a “nothing-state” would be, we will see that that theistic conclusion isn’t warranted. Other scenarios, such as a multiverse scenario, are no less likely or even more likely. Of course, this has, again, absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with what the Aristotelian proof actually says, and so Carrier’s objection would be completely irrelevant even if it were at all clear what that objection is. Carrier’s readers will learn as much about what my Aristotelian argument actually says as they would if they’d read an automotive repair manual instead. Only that would have been more lucid and interesting reading.

Here, Carrier seems to be making a mistake common to so many pop atheist writers and amateur philosophers, viz. attacking some argument he thinks he knows something about and feels confident he can refute, instead of what his opponent actually said. In this case, he appears fixated on the idea that causal arguments for God are essentially attempts to answer the question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” and that they all assume that there could at least in principle have been nothing. As anyone knows who has actually read my book (as opposed to reading weird things into my book), that is nowhere close to how any of my arguments proceed. In fact, I explicitly say in the book (at p. 155) that that is a bad way to frame the issue and that in my view there could not in principle have been nothing.

In response to the argument I actually gave for the existence of a purely actual actualizer (what Aristotle calls the Unmoved Mover), Carrier has absolutely nothing to say. He is very slightly better when responding to the arguments I gave for ascribing the divine attributes to the purely actual actualizer. But only insofar as this time he responds, at least initially, to something I really did write. Discussing my argument for attributing omniscience to the purely actual actualizer, Carrier begins:

[In] Feser’s formalization of this argument… Premise 41… [says] “the forms or patterns manifest in all the things [the substrate] causes… can exist either in the concrete way in which they exist in individual particular things, or in the abstract way in which they exist in the thoughts of an intellect.” This is a false dichotomy, otherwise known as a bifurcation fallacy. It’s simply not true that those are the only two options.

End quote. “Substrate” is Carrier’s word for the purely actual actualizer and not a good one, but let that pass. The main problem with this is that I would be guilty of a false dichotomy here only if I did not consider, and give arguments to rule out, alternatives to the two I refer to in premise 41. But of course, I do consider and give arguments to rule out alternatives to those two. (Carrier is here quoting from a summary of the argument, and ignoring what I say earlier and later in the book.) For example, I explicitly note at p. 209, in the context of discussing omniscience in greater detail, that a third alternative would be the Platonic view that forms exist in a third realm distinct from either concrete particular things or intellects. This is after I spend much of chapter 3 arguing against this third, Platonic alternative.

Furthermore, Carrier distorts what I say here because he collapses two steps of the argument he’s quoting from (steps 40 and 41) into one, without telling the reader that that is what he is doing. The argument up to step 40 establishes that the forms or patterns in question exist in the purely actual actualizer. Since the purely actual actualizer is not an abstract entity, that already rules out a third alternative such as the Platonic realm. Hence the thesis in step 41 is not the leap in logic that Carrier represents it as being.

Carrier, in any case, at this point unfortunately once again lapses back into vigorously attacking an argument that exists only in his imagination. For some reason, he seems to think I am adopting something like Plato’s view. (“Aristotle took Plato to task for the mistake Feser is making,” he writes. No, I don’t know what the hell he’s talking about either.) As if responding to something I had actually said, he writes: “It’s thus self-contradictory of Feser to insist that potential things must be ‘actualized’ somewhere,” and continues in this vein at obscure and tedious length. Since I never said anything of the kind, and once again can barely make heads or tails of Carrier’s remarks other than to note that they bear no relation to any argument I actually gave, I will skip these further irrelevancies and move on to what seems to be Carrier’s main objection.

Carrier proposes that instead of the purely actual actualizer, it is plausibly just space-time that is the ultimate reality. He thinks it could even be said to have the key divine attributes. He doesn’t endorse this position himself, but thinks that it no less plausibly follows from my premises than my own conclusion does.

One problem with this is that, contrary to what Carrier supposes, this would not be consistent with atheism, but would amount to a kind of pantheism. The main problem, though, is that space-time simply could not be the ultimate reality, for reasons that should be obvious to anyone who has read my book. Space-time, for all Carrier has shown, is contingent. Accordingly, its essence is distinct from its existence, it is by itself merely potential unless actualized, and thus it requires a cause distinct from it. Since it is extended, it is also in the relevant sense material (contrary to what Carrier asserts) and is composite rather than simple (contrary to what Carrier asserts). Of course, Carrier would reject these claims and the philosophical arguments I deploy in order to defend them, but the point is that he gives absolutely no non-question-begging reason to reject them.

There are plenty of other foolish remarks. For example, Carrier claims that the Aristotelian notions I deploy are “obsolete” and accuses me of “ignoring the sciences.” But he never tells us exactly whythe notions in question are obsolete or exactly what is the relevant scientific evidence that I ignore. And in fact, at pp. 43-60 I explicitly address the various scientific objections (from Newton, from quantum mechanics, from relativity, etc.) that might be raised against the Aristotelian proof and I explicitly address the charge that the argument presupposes obsolete Aristotelian scientific ideas and show that it has no force. Carrier says nothing in response to these points.

Carrier repeatedly asserts that my arguments must be non-starters because they are metaphysical rather than scientific. But of course, throughout the book I defend the claim that science is not the only rational form of inquiry. For example, at pp. 273-285 I explicitly argue against the scientism that Carrier simply takes for granted. He has nothing to say in response to those arguments either.

Carrier alleges that the last chapter of my book, wherein I respond to the standard general objections to the project of natural theology, “only ‘succeeds’ by omitting everything that actually undermines his conclusions.” But not only does he give no actual examples of objections I ignore that undermine my conclusions, he explicitly declines to respond to anything I say in that chapter, claiming that “it won’t serve any function” to do so. (Evidently, responding to what an author actually wrote is not in Carrier’s view a “function” of a book review.)

Carrier characterizes the purely actual actualizer as “self-actualizing” and says that the intelligence I attribute to the purely actual actualizer is an “organized complexity.” This is cringe-makingly incompetent, for of course, no Aristotelian or Thomist would ever say such things. The divine intellect, being absolutely simple, is the opposite of complex, and God’s being purely actual entails that he is not actualized at all, let alone “self-”actualized. Such basic errors would by themselves suffice to show that Carrier simply doesn’t know what he is talking about, if that weren’t blindingly obvious already.

My favorite piece of Carrier incompetence is this:

Though there is a lot there of interest if you want to explore Feser’s theology – including a really bizarre, sexist argument for God being a man (around pages 246-57).

End quote. First of all, the argument he’s referring to is actually at pp. 246-48. Second, of course I do not argue that God is a “man.” In fact I explicitly say at pp. 246-7 that “since [God] is not a human being, he is not literally either a man or a woman. He is sexless” (emphasis added). Rather, I argue for the appropriateness of using masculine languagein a non-univocal way when speaking of God. Third, I do give actual arguments, which Carrier simply ignores. Fourth, of course Carrier couldn’t care less about all that, but is just interested in throwing out some red meat to the SJW crowd.

The rest is trash talk (“He’s done. Cooked,” “100% bullshit,” etc.), central casting New Atheist straw men (“Giant Ghost hypothesis”), and relentless and relentlessly question-begging dime-store scientism. Nothing intellectually serious.

It is hard to believe that Carrier actually read Five Proofs through, but I certainly did not bother to read the rest of his critique, judging that if what he has to say about the Aristotelian proof is this awful, it would be a waste of time and energy to proceed any further. If any reader has bothered to read it and found some gold among the dross, feel free to call our attention to it in the combox below.

Published on February 24, 2018 10:52

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 330 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.