Edward Feser's Blog, page 56

May 4, 2018

Claremont Center

The recent exchange between Bishop Robert Barron and William Lane Craig was sponsored by the Claremont Center for Reason, Religion, and Public Affairs, with which I am associated. The Center’s website has just gone live, and will give you more information about the Center and its associated scholars and activities. Links to audio and video of the Barron-Craig events can be found here.

The recent exchange between Bishop Robert Barron and William Lane Craig was sponsored by the Claremont Center for Reason, Religion, and Public Affairs, with which I am associated. The Center’s website has just gone live, and will give you more information about the Center and its associated scholars and activities. Links to audio and video of the Barron-Craig events can be found here.

Published on May 04, 2018 15:48

April 28, 2018

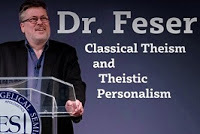

SES podcast on classical theism

While at Southern Evangelical Seminary last week, I recorded a podcast with Adam Tucker on the topic of classical theism and theistic personalism. You can listen to it here. If and when the evening lecture I gave at SES is also posted online, I’ll let you know. Stay tuned.

While at Southern Evangelical Seminary last week, I recorded a podcast with Adam Tucker on the topic of classical theism and theistic personalism. You can listen to it here. If and when the evening lecture I gave at SES is also posted online, I’ll let you know. Stay tuned.

Published on April 28, 2018 14:17

April 25, 2018

Cooperation with sins against prudence (and chastity)

Last month I gave a talk on the theme “Cooperation with Sins against Prudence” at a conference on Cooperation with Evil at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C. You can now listen to the talk at the Thomistic Institute’s Soundcloud page. Prudence is the virtue by which we know the right ends to pursue and the right means by which to pursue them. Aquinas argued that sexual immorality tends more than other vices to erode prudence. The erosion of prudence, in turn, tends to undermine one’s general capacity for moral reasoning. Hence, when we facilitate the sexual sins of others, we tend thereby (whether we realize it or not) to promote their general moral corruption. In the talk, I develop and defend this theme and apply it to a critique of the views of Fr. Antonio Spadaro and Fr. James Martin. The other presenters at the conference were Msgr. Andrew McLean Cummings, Steven Long,Fr. Ezra Sullivan, and Christopher Tollefsen. You can find their talks at the Soundcloud page as well.

Last month I gave a talk on the theme “Cooperation with Sins against Prudence” at a conference on Cooperation with Evil at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C. You can now listen to the talk at the Thomistic Institute’s Soundcloud page. Prudence is the virtue by which we know the right ends to pursue and the right means by which to pursue them. Aquinas argued that sexual immorality tends more than other vices to erode prudence. The erosion of prudence, in turn, tends to undermine one’s general capacity for moral reasoning. Hence, when we facilitate the sexual sins of others, we tend thereby (whether we realize it or not) to promote their general moral corruption. In the talk, I develop and defend this theme and apply it to a critique of the views of Fr. Antonio Spadaro and Fr. James Martin. The other presenters at the conference were Msgr. Andrew McLean Cummings, Steven Long,Fr. Ezra Sullivan, and Christopher Tollefsen. You can find their talks at the Soundcloud page as well.

Published on April 25, 2018 17:52

April 22, 2018

Lessons from St. Justin Martyr

My article “The Unapologetic Apologist: Five Lessons from St. Justin Martyr” appears today at Catholic World Report. You can find links to my other CWR articles here.

My article “The Unapologetic Apologist: Five Lessons from St. Justin Martyr” appears today at Catholic World Report. You can find links to my other CWR articles here.

Published on April 22, 2018 17:54

April 20, 2018

Best T-shirt ever

Just back from a very enjoyable visit to Southern Evangelical Seminary, where I gave a lecture last night on classical theism. Many thanks to the very kind folks at SES for their hospitality. And thanks also for what is probably the best T-shirt I’ve ever seen – SES’s Act and Potency T-shirt, emblazoned with an image of Aquinas together with the first of the Twenty-Four Thomistic Theses. You can pick one up via the SES store website, where I see they also have a matching Act and Potency coffee mug and Act and Potency poster. Amaze your friends, or at least baffle them! (Readers of p. 56 of

The Last Superstition

will know why this makes me feel a little like a prophet!)

Just back from a very enjoyable visit to Southern Evangelical Seminary, where I gave a lecture last night on classical theism. Many thanks to the very kind folks at SES for their hospitality. And thanks also for what is probably the best T-shirt I’ve ever seen – SES’s Act and Potency T-shirt, emblazoned with an image of Aquinas together with the first of the Twenty-Four Thomistic Theses. You can pick one up via the SES store website, where I see they also have a matching Act and Potency coffee mug and Act and Potency poster. Amaze your friends, or at least baffle them! (Readers of p. 56 of

The Last Superstition

will know why this makes me feel a little like a prophet!)

Published on April 20, 2018 16:44

April 15, 2018

Does God have emotions?

An accusation sometimes leveled by theistic personalists against the classical theism of thinkers like Augustine, Anselm, and Aquinas is that their position makes God out to be “unemotional” or “unfeeling” and thus less than personal. Is the charge just? It is not, as I’ve argued many times. So, does God have emotions? It depends on what you mean. On the one hand, as Aquinas argues in Summa Contra Gentiles I.89, it is not correct to attribute to God what he calls “the passions of the appetites.” For passions involve changeability, and since God is purely actual and without passive potentiality, he cannot change. Hence it makes no sense to think of God becoming agitated or calming down, feeling a sudden pang of sadness or a surge of excitement, or undergoing any of the other shifts in affect that we often have in mind when we talk of the emotions. On the other hand, no sooner does Aquinas say this than he immediately goes on in SCG I.90-91 to argue that there is in God delight, joy, and love. And of course, delight, joy, and love are also among the things we have in mind when we talk of the emotions. I have discussed the sense in which God can be said to love in

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

(at pp. 228-29), and I won’t repeat here what I already said there. But let’s talk about Aquinas’s arguments for attributing delight and joy to God.

An accusation sometimes leveled by theistic personalists against the classical theism of thinkers like Augustine, Anselm, and Aquinas is that their position makes God out to be “unemotional” or “unfeeling” and thus less than personal. Is the charge just? It is not, as I’ve argued many times. So, does God have emotions? It depends on what you mean. On the one hand, as Aquinas argues in Summa Contra Gentiles I.89, it is not correct to attribute to God what he calls “the passions of the appetites.” For passions involve changeability, and since God is purely actual and without passive potentiality, he cannot change. Hence it makes no sense to think of God becoming agitated or calming down, feeling a sudden pang of sadness or a surge of excitement, or undergoing any of the other shifts in affect that we often have in mind when we talk of the emotions. On the other hand, no sooner does Aquinas say this than he immediately goes on in SCG I.90-91 to argue that there is in God delight, joy, and love. And of course, delight, joy, and love are also among the things we have in mind when we talk of the emotions. I have discussed the sense in which God can be said to love in

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

(at pp. 228-29), and I won’t repeat here what I already said there. But let’s talk about Aquinas’s arguments for attributing delight and joy to God.Delight and joy both essentially involve the actual possession of some perceived good that one wills, with the difference, in Aquinas’s view, being that in delight the good in question is “really conjoined” to the one who is delighted whereas in joy it need not be. Hence, suppose you and your child are both looking forward to some ice cream you have ordered on a hot summer’s day. When you actually get it and start eating it you take delight in it insofar as it is sweet, cool, and refreshing. Your child also delights in it, for the same reasons. Now, as Aquinas uses the term, you don’t, strictly speaking, delight in your child’s ice cream, precisely because he (and not you) is the one who is eating and enjoying it (and is thus “conjoined” to that good). However, you do take joy in his having the ice cream, insofar you take his possession and enjoyment of his ice cream to be good in just the way your possession and enjoyment of your own ice cream is good.

In God’s case, Aquinas says, “it is apparent that God properly delights in Himself, but He takes joy both in Himself and in other things.” However, there are aspects of joy and delight as they exist in us that cannot be attributed to God. Most obviously, in us joy and delight wax and wane. We might go from being miserable to merely feeling blah to being in a moderately good mood to feeling deliriously happy and then back again to misery, or blah-ness, or mere moderately good spirits. Since God is immutable, no such transitions can occur in him.

Another difference derives from the fact that while there are intellect and will in God, there are no sense organs in him, since he is incorporeal and impassible. Go back to your enjoyment of the ice cream. It occurs because certain sense organs are altered by the ice cream, and this occurs at a particular time and place. It is this particular sweetness of this particular object that affects you and that you enjoy here and now. And the enjoyment is associated with certain sensations in particular parts of the body. These material, spatial, and temporal limitations do not apply to God. His delight and joy in a thing does not have anything to do with his being altered by it, or with him having sensations in body parts, or with some particular need being satisfied in a particular way on a particular occasion.

Critics of classical theism are apt to judge that such qualifications must entail that delight and joy can exist in God only in some thin and disappointing manner. They are likely to suppose that God, as the classical theist conceives of him, lacks the rich delight and joy of which we are capable, and can possess only some bloodless, machine-like ersatz. But that is exactly the opposite of the lesson they should be drawing. In fact, our delight and joy are much less than God’s, and precisely because they are limited by the body and the senses. God’s delight and joy never wane, and they are not limited to a succession of fleeting experiences of particular finite goods at specific times and places. Rather, they involve the eternal and metaphysically necessary possession of an infinite good. It is preposterous to think of that as somehow inferior to the piddling pleasures of which we poor rational animals are capable.

The theological imaginations of critics of classical theism are limited precisely because they rely on imagination, in the sense of forming mental imagery – on exercises like considering what things would seem like for them if they remained conscious and able to think but lost their sense organs and viscera, and concluding, absurdly, that that must be the kind of thing the classical theist has in mind. In effect, they start conceiving of God as a kind of defective human being. They are so lost in anthropomorphism that even when they think they are avoiding it they are in fact only sinking deeper into it. Tell them that God lacks our bodily limitations and they conclude that what he has must be something less than what we have, when in fact the whole point is that it is something morethan what we have.

Even these critics of classical theism seem not to make this mistake where the divine intellect is concerned, or at least not to make it as badly. If you tell them that God’s intellect is not limited by having to take in information through sense organs or by having to process it through neural activity, they don’t conclude from this that God must therefore be dumber than us. Yet for some reason they suppose that if God lacks experiential episodes like ours, then he must be less capable of joy, delight, and the like than we are!

(At pp. 215-16 of Five Proofs, I proposed a series of analogies – the conjunction of all true propositions, the way that colors are contained in a beam of white light, and the way that a variety of shapes are contained virtually in a lump of dough – as means by which to get a handle on what it means to say that there is in God all knowledge. It might be a useful exercise for the reader to try to apply such analogies to the attempt to get a better handle on what it means to say that there is in God unlimited delight and joy.)

Related posts:

Olson contra classical theism

The divine intellect

A complex god with a god complex

Progressive dematerialization

Classical theism roundup

Published on April 15, 2018 19:20

April 13, 2018

Upcoming speaking engagements

Just back from a very enjoyable speaking engagement at Baylor University. Here are the next few scheduled talks:

Just back from a very enjoyable speaking engagement at Baylor University. Here are the next few scheduled talks:On Thursday, April 19, I will be speaking on the topic of classical theism and the divine attributes at Southern Evangelical Seminary near Charlotte, North Carolina. More information here.

I will be speaking at the Society of Catholic Scientists conference on The Human Mind and Physicalism which will be held at Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. from June 8-10. More information here.

On June 27, I will be speaking at Fermilab near Chicago, Illinois, on the topic “What is a Law of Nature?” More information here.

Further speaking engagements to be announced. Stay tuned.

Published on April 13, 2018 16:32

April 5, 2018

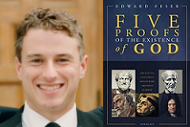

Chalk on Five Proofs, etc.

At The American Conservative, Casey Chalk recounts some of the public controversies I’ve been party to over the last few years, and judges them a model of how academic debate ought to proceed. (David Bentley Hart drops by to comment in the TAC combox.) Meanwhile, at The University Bookman, Chalk kindly reviews

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. From the review: The book will satisfy a diversity of readers… [A]n effective introduction to natural theology and many of its most salient concepts…

At The American Conservative, Casey Chalk recounts some of the public controversies I’ve been party to over the last few years, and judges them a model of how academic debate ought to proceed. (David Bentley Hart drops by to comment in the TAC combox.) Meanwhile, at The University Bookman, Chalk kindly reviews

Five Proofs of the Existence of God

. From the review: The book will satisfy a diversity of readers… [A]n effective introduction to natural theology and many of its most salient concepts…After considering the clarity and acuity of Five Proofs, one wonders how the New Atheists would manage against a thinker with the training, wit, and rhetorical ability of an Ed Feser. God willing, we may one day find out.

Published on April 05, 2018 18:36

April 4, 2018

Five Books on Arguments for God’s Existence (Updated)

Five Books is a website devoted to in-depth interviews with leaders in a wide variety of fields – philosophy, politics, science, literature, and so forth – about five books in their fields that they would recommend. Recently I was interviewed for the site on the subject of five books on arguments for the existence of God. It’s a pretty long interview (and conversational in style insofar as it was conducted by telephone).While you’re over there, take a look around. There are over 1000 interviews at Five Books with public figures as diverse as Karl Rove, Woody Allen, Paul Krugman and Jerry Coyne, including interviews with prominent contemporary philosophers.

Five Books is a website devoted to in-depth interviews with leaders in a wide variety of fields – philosophy, politics, science, literature, and so forth – about five books in their fields that they would recommend. Recently I was interviewed for the site on the subject of five books on arguments for the existence of God. It’s a pretty long interview (and conversational in style insofar as it was conducted by telephone).While you’re over there, take a look around. There are over 1000 interviews at Five Books with public figures as diverse as Karl Rove, Woody Allen, Paul Krugman and Jerry Coyne, including interviews with prominent contemporary philosophers.UPDATE 4/6: Commenting on the interview, Jerry Coyne does an absolutely brilliant, dead-on parody of a Jerry Coyne blog post.

Published on April 04, 2018 16:17

Five Books on Arguments for God’s Existence

Five Books is a website devoted to in-depth interviews with leaders in a wide variety of fields – philosophy, politics, science, literature, and so forth – about five books in their fields that they would recommend. Recently I was interviewed for the site on the subject of five books on arguments for the existence of God. It’s a pretty long interview (and conversational in style insofar as it was conducted by telephone). While you’re over there, take a look around. There are over 1000 interviews at Five Books with public figures as diverse as Karl Rove, Woody Allen, Paul Krugman and Jerry Coyne, including interviews with prominent contemporary philosophers.

Five Books is a website devoted to in-depth interviews with leaders in a wide variety of fields – philosophy, politics, science, literature, and so forth – about five books in their fields that they would recommend. Recently I was interviewed for the site on the subject of five books on arguments for the existence of God. It’s a pretty long interview (and conversational in style insofar as it was conducted by telephone). While you’re over there, take a look around. There are over 1000 interviews at Five Books with public figures as diverse as Karl Rove, Woody Allen, Paul Krugman and Jerry Coyne, including interviews with prominent contemporary philosophers.

Published on April 04, 2018 16:17

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 332 followers

Edward Feser isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.