Edward Feser's Blog

November 27, 2025

Liberalism and the virtue of gratitude

In a new essayat Postliberal Order, I reflecton the virtue of gratitude or thanksgiving and the ways it tends to be erodedin liberal societies.

In a new essayat Postliberal Order, I reflecton the virtue of gratitude or thanksgiving and the ways it tends to be erodedin liberal societies.

November 21, 2025

Pope Leo on immigration enforcement

Pope Leo wasrecently asked by a reporter about the deportation and detention of illegal immigrants. In response,he made the following remarks:

Pope Leo wasrecently asked by a reporter about the deportation and detention of illegal immigrants. In response,he made the following remarks:I think we have to look for ways of treating people humanely,treating people with the dignity that they have. If people are in the United States illegally,there are ways to treat that. There arecourts, there’s a system of justice. Ithink there are a lot of problems in the system. No one has said that the United States shouldhave open borders. I think every countryhas a right to determine who and how and when people enter. But when people are living good lives, andmany of them for ten, fifteen, twenty years, to treat them in a way that isextremely disrespectful to say the least, and there has been some violenceunfortunately, I think that the Bishops have been very clear in what they saidand I think that I would just invite all people in the United States to listento them.

This is arefreshingly calm, reasonable, and nuanced approach. As I have shown in earlier articles (atPublic Discourse and at UnHerd), the Church hastraditionally affirmed both that wealthy nations have a general obligation towelcome immigrants to the extent they are able, but also that they are notobligated to let in all who seek to enter, that they may put conditions onentry that take account of the economic needs and cultural cohesion of thereceiving nation, and that immigrants must obey the law.

Churchmenwho comment on immigration these days sometimes acknowledge the right of anation to control its borders, but only in the vaguest way, and while seemingto criticize all actual efforts at enforcement. The pope’s acknowledgement is much more concrete. He not only eschews the idea of open borders,but specifically says that a nation “has a right to determine who and how andwhen people enter.” That entails that noteveryone must be allowed in, and that a nation can put conditions on the entryof those who are allowed in. The popealso says that it is legitimate to “treat” the problem of those who are in thecountry illegally, namely through “courts… [and the] system of justice.” That entails that a country need not, ingeneral, simply accept the presence of those who are in the country illegally,but may resort to the legal penalties appropriate to this particular sort oflawbreaking.Though hedoesn’t explicitly say so, deportation is obviously among these penalties. (It would make no sense to say that peopleshouldn’t enter illegally but then refuse ever to deport someone, just as itwould make no sense to say that people shouldn’t steal but then refuse ever tomake a thief give back what he has stolen.) The qualification the pope puts on his remarks on controlling borders isnot that the law should not be enforced, but rather that this should be done ina humane and respectful way.

He also putsspecial emphasis on the need to deal respectfully with illegal immigrants who “areliving good lives, and many of them for 10, 15, 20 years.” This seems implicitly to acknowledge that thecase for punishment or deportation is stronger for those who are engaged incriminal activity (beyond just illegal entry) and for those whose illegal entrywas more recent.

This much islikely to be welcome to those who support the Trump administration’s efforts touse deportation to reverse the Biden administration’s lax border policies. However, many of them are also likely to beunhappy with the pope’s view that illegal immigrants who otherwise obey thelaw, and who have been in the country a long time, ought to be treated moregently. Some seem to take the view thatthe only thing that matters is whether someone entered the country illegally,so that deportation is equally appropriate for all such people, regardless ofhow long they have been in the country or how law-abiding they have otherwisebeen.

However, themoral issues here are not that simple, and the pope’s remarks reflect important and longstanding principlesin natural law and Catholic moral theology. Catholics need to consider these principles and resist the temptation toview everything churchmen say about this issue through a political lens, as ifabsolutely every expression ofsympathy for illegal immigrants reflects liberal political commitments ratherthan Catholic tradition. That just isn’tthe case.

St. Alphonsus on custom

Among therelevant considerations here are what moral theologians have said about the waythat custom can, under certaincircumstances, override human law. St.Alphonsus Liguori addresses the topic in Book I, Treatise II of his Theologia Moralis. He identifies three conditions that custommust meet in order to have this effect.

First, thecustom must not be merely a matter of what this or that individual does, butmust reflect the practice of the entire community, or at least themajority. The reason is that if the governingauthorities tolerate a custom that prevails within the community at large, thatcan be interpreted as their having at least tacitly consented to it.

Second, whatis in question must indeed be merely humanlaw. Custom cannot override natural law ordivine law. However, it is not necessarythat the initial introduction of the custom have been sinless. Liguori says that although those who firstviolated the law in such a case sinned, once the custom of violating it hastaken hold and been tolerated, those who later follow this custom do not sin,and if the custom prevails long enough it would not be justifiable topunish them for following it.

Third,Liguori says that “a continuous and long-lasting period of time is required” inorder for the custom to take root (Granttranslation, p. 192). Exactly howlong is a matter of dispute, but Liguori notes that some theologians hold thatten years is sufficient. (In thisconnection, it is interesting to note that Pope Leo refers to those who havebeen in the country illegally for “ten, fifteen, twenty years.”)

But howcould custom override law even given these conditions? I’d explain how as follows. Note first that in the natural law tradition,promulgation is essential to law. If acustom that conflicts with some human law takes root and the governingauthorities do not enforce the law but instead implicitly consent to the customthat is contrary to it, then a kind of virtual promulgation of the custom canbe said to have occurred.

Note secondthat law exists for the good of the social order, and social life requires stabilityand predictability. When a custom isestablished and then tolerated by public authorities long enough for people tocome to rely on it, suddenly to punish them for following the custom wouldundermine the stability of the lives they have built. And that would be contrary to the reason forwhich the law exists.

However, St.Alphonsus also indicates that if the governing authorities begin to enforce thehuman law that the custom conflicts with, this would undermine the force of thecustom. From the context, it seems hemay be talking about a case where such enforcement prevents the custom fromtaking deep root in the first place. Buthe may also mean that even after the custom has taken deep root, if thegoverning authorities start enforcing the law again, the force of the custom isnullified. Certainly such enforcementwould plausibly amount to the authorities’ once again promulgating the originallaw.

Though St.Alphonsus does not explicitly say so, the implication of his principles wouldseem to be that those who violated the law during the long but temporary periodwhen the governing authorities were still tolerating such violation should notbe punished, but that more recent violators may be punished.

Application to immigrationenforcement

This is, ofcourse, all very abstract. How would itapply to the concrete case of illegal immigration? The idea would be this. For decades until recently, U.S. immigrationenforcement was more lax, with public authorities tolerating large numbers ofillegal immigrants. And this has been abipartisan tendency, so that the federal government as such (and not merelythis or that party that held power at any particular time) can he said to havetolerated this. To be sure, there hasalways been some enforcement, so thatit cannot be said that the authorities had ever tacitly consented to an openborders policy. But (so the argumentwould continue) they did nevertheless tacitly consent to permitting largenumbers of illegal immigrants to remain in the country relatively unmolested, andto secure employment, build families, etc. A custom of forming such communities had taken root and been tacitly consentedto by the public authorities.

In recentyears, however, the public authorities have once again begun vigorously to enforcethe immigration laws. There has beensome inconsistency, insofar as vigorous enforcement during the first Trumpadministration was followed by lax enforcement under Biden, followed byvigorous enforcement once again during the second Trump administration. But it can no longer be said that the federalgovernment as such tacitly consentsto the custom of forming communities of large numbers of illegal immigrants. Those who have entered the country illegallyin recent years therefore cannot appeal to the force of custom, in the way thatthose who have been here illegally since the years prior to Trump might appealto it.

Applying St.Alphonsus’s principles, then, there are grounds for treating illegal immigrantswho have been in the country for decades with more leniency than those who haveentered the country in recent years. Andthis, I believe, is basically the thinking that underlies the pope’s remarks. It doesn’t follow that those who have beenhere for decades may not be punished at all (through fines, for example),because while enforcement was during that time more lax, it was notnon-existent. Hence the tacit message sentwas not that the public authorities consented to illegal immigration, butrather that they would treat it leniently. But neither does the pope say that those who illegally entered thecountry decades ago may not be punished at all. What his remarks indicate is rather that they should not be dealt with inthe same manner as those who have entered more recently. Because they have been here so long,peremptorily deporting them can be greatly disruptive (to families, forexample) and thus contrary to the good of the social order, in a way thatdeporting those who entered recently is not.

To be sure,reasonable people can disagree about the details. There are multiple moral principles to bringto bear here, and multiple empirical considerations that have to be takenaccount of in applying them. As in otherareas of prudential judgment, it is wise for the Church to set out the generalprinciples and leave it to the faithful and to public authorities to debate and determinethe best way to implement them.

The point,though, is that the pope’s remarks cannot justly be dismissed as a sellout tofashionable liberal political opinion. They have a solid foundation in traditional Catholic moral theology anddeserve a respectful hearing.

November 13, 2025

Searle contra deconstruction

In a newessay at Postliberal Order, I recallthe late John Searle’s critique of deconstructionism and postmodernism moregenerally, which were major influences on today’s woke ideologies.

In a newessay at Postliberal Order, I recallthe late John Searle’s critique of deconstructionism and postmodernism moregenerally, which were major influences on today’s woke ideologies.

November 12, 2025

Remembering John Searle

I wrote an obituary forJohn Searle, which appears in the December 2025 issue of First Things.

I wrote an obituary forJohn Searle, which appears in the December 2025 issue of First Things.

November 4, 2025

Cardinal Fernández on doctrinal clarity

From Twitter/X today,apropos of MaterPopuli Fidelis:

October 24, 2025

There are two sides to the Catholic immigration debate

Everyoneknows that the Catholic Church teaches that wealthy nations ought to welcomeimmigrants. It is less well known thatshe also teaches that a nation may put conditions on immigration, that it neednot take in all those who want to enter it, and that those it does allow inmust follow the law. In anarticle at UnHerd, I spell outthis neglected side of Catholic teaching. Defenders and critics of Trump administration policy alike can appeal tomoral premises from the Church’s tradition.

Everyoneknows that the Catholic Church teaches that wealthy nations ought to welcomeimmigrants. It is less well known thatshe also teaches that a nation may put conditions on immigration, that it neednot take in all those who want to enter it, and that those it does allow inmust follow the law. In anarticle at UnHerd, I spell outthis neglected side of Catholic teaching. Defenders and critics of Trump administration policy alike can appeal tomoral premises from the Church’s tradition.

October 18, 2025

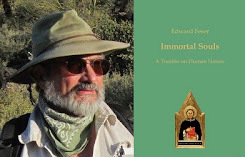

Vallicella on Immortal Souls

At hisSubstack Philosophy in Progress, myold buddy Bill Vallicella engageswith my book

Immortal Souls: A Treatise on HumanNature

. Bill kindly opines:“[It] may well be the best compendium of Thomist philosophical anthropologypresently available. I stronglyrecommend it.” All the same, he hasdoubts about the compatibility of two of the books key themes: the Aristotelianhylomorphic conception of the soul as the form of the body, and the continuedexistence of any particular individual’s soul after the death of his body. Let’s take a look at his objection.

At hisSubstack Philosophy in Progress, myold buddy Bill Vallicella engageswith my book

Immortal Souls: A Treatise on HumanNature

. Bill kindly opines:“[It] may well be the best compendium of Thomist philosophical anthropologypresently available. I stronglyrecommend it.” All the same, he hasdoubts about the compatibility of two of the books key themes: the Aristotelianhylomorphic conception of the soul as the form of the body, and the continuedexistence of any particular individual’s soul after the death of his body. Let’s take a look at his objection.Hylomorphism in brief

Longtimereaders of this blog or of my books will be familiar with theAristotelian-Thomistic conception of physical substances as composites of formand matter, where (to a first approximation) matter is the stuff out of which sucha substance is made and form is what organizes that stuff in a way that allowsit to manifest its characteristic properties and powers. More precisely, it is substantial form that does so. And the soul is a substantial form of the kind that gives a physicalsubstance the distinctive properties and powers of a living thing.

Matter, onAquinas’s account, is what makes it possible for there to be more than one instanceof any species of physical substance (using “species” here in the traditionalbroad metaphysical sense, not the narrower biological sense). Different lumps of iron all have the samebasic nature, as do different oak trees and different poodles. But if they have the same nature, how canthey be different substances? The answeris that there are different bits of matter which have all taken on the samenature. Matter is in this way the “principleof individuation” of physical substances.

When thematter of a purely physical substance loses its substantial form, thatparticular substance goes out of existence altogether. For example, when you chop down an oak treeand burn it in the fireplace, that particular oak tree is gone. The matter out of which it is made persists,but it has taken on an entirely different form, the form of ash. The substantial form of an oak tree is nolonger present in it (even though there are, of course, other oak trees, and they have such a substantial form).

Now, Aquinasthinks of angels as substances that are purely intellectual in nature, and thus(since he takes the intellect to be incorporeal) to be immaterialsubstances. Because they are immaterial,there is no way to individuate one member of an angelic species fromanother. There can still be differentspecies of angel, but each will have exactly one member. Hence there are as many angelic species asthere are angels.

The humanintellect, like angelic intellects, is incorporeal. How, then, can there be more than one memberof the human species? The answer, for Aquinas,is that while human beings are not purely corporeal substances (unlike iron,oak trees, and poodles) neither are they purelyincorporeal substances (as angels are). A human being is a unique sort of substance that has both corporealproperties and powers (such as eating, walking, seeing, and hearing) andincorporeal ones (thinking and willing).

Becausehuman beings are partly corporeal, they can be individuated from one another asdifferent members of the same species. But because they are partly incorporeal, they do not go out of existencealtogether at death. They carry on as incompletesubstances after death, reduced to just their intellectual (and thusincorporeal) operations. Because everysubstance has a form, and human beings continue on as incomplete substances, ahuman being’s form continues on after death. And since the soul just is the substantial form of a human being, that meansthat the soul carries on after death. Itno longer manifests the corporealpowers that it would normally give human beings (since, absent the body, there’sno matter for it to inform). But the incorporeal powers can stillmanifest.

Vallicella’s objection

Bill beginshis criticism of this view by saying that Aristotelian-Thomistic hylomorphism holdsthat “substances of the same kind have the same substantial form.” In the case of human beings, he continues, “sincethese substances of the human kind have the same form, it is not their formthat makes them numerically different… It is the matter of their respective bodies that makesnumerically different human beings numerically different.”

But in thatcase, Bill argues, when the matter of some particular human being goes atdeath, there is nothing left to individuate him. Hence there can be nothing of him, in particular, that carrieson. Bill writes:

After death a human person ceases to exist as the particularperson that he or she is. But that is tosay that the particular person, Socrates say, ceases to exist, full stop. What survives is at best a form which iscommon to all persons. That form,however, cannot be you or me. Thus theparticularity, individuality, haecceity, ipseity of persons, which is essentialto persons, is lost at death and does not survive post mortem.

Bill appearsto think that if the Aristotelian-Thomistic view were applied consistently, itwould have to say of human beings what it says of iron, oak trees, andpoodles. Just as the particularindividual oak tree that you burn in the fireplace is altogether gone (eventhough there are other oak trees that carry on), so too, after death, is theparticular individual human being altogether gone (even though there are otherhuman beings who carry on).

But thereare two problems with Bill’s argument. The first is that it rests on a mistaken conception of substantialform. The second is that it neglects thecrucial difference the Thomist says exists between human beings and every othercorporeal substance, which is that human beings have incorporeal intellectualpowers.

Let’sconsider these points in order. WhenBill says that, for hylomorphism, “substances of the same kind have the samesubstantial form,” he speaks ambiguously. That could mean that, while each individual physical substance has itsown substantial form, with physical substances of the same species theirsubstantial forms are of the same kind. That would be a correct characterization of the Aristotelian-Thomisticposition, but unfortunately it does not seem to be what Bill means. He seems to mean instead that there is onesubstantial form shared by all human beings in common – not one kind of substantial form, but one substantial form.

But that isnot what Aristotelian-Thomistic hylomorphism says, and it is not true. There are, it seems to me, two ways to readBill’s claim. On one reading, thesubstantial form of human beings is a kind of Platonic Form, and differenthuman bodies are all human because they participate in that same one Form. The problem with this is that it isn’t an Aristotelian conception of form at all,but a Platonic conception. A substantialform, for the Aristotelian, isn’t an abstract Platonic object in which a thingparticipates. Rather, it is a concreteprinciple intrinsic to a substance that grounds its characteristic propertiesand powers.

The otherway to read Bill’s characterization of hylomorphism is as holding that humanbeings share one substantial form in the sense that they are all part of onebig substance – humanity considered as something like a single organism, withdifferent individual human beings as analogous to body parts that that organismgains or loses as people are conceived or die. But this is obviously not Aristotle’s or Aquinas’s view. They take human beings to be substances, not parts of a substance. And assubstances, each must have his own substantial form.

I think it’sthe first of these interpretations (what I’m characterizing as the Platonicone), rather than the second, that Bill has in mind. But, again, it is a mistakeninterpretation. It just isn’t the casethat you, me, and Socrates all share the same one substantial form in the senseBill’s argument requires. Rather, youhave your own substantial form (and thus soul), I have mine, and Socrates hashis.

The samething is true of an oak tree. This oaktree has its own individual substantial form, that oak tree has its own individualsubstantial form, and so on. The reasonnone of them continue after death is that everything an oak tree has or does –and thus every property or power its substantial form gives it – depends onmatter. Hence when the matter goes,there’s nothing left for the form to inform, nothing left for it to be the formof.

This bringsus to the second crucial point, which is that a human being, unlike an oaktree, has properties and powers that do notdepend on matter – namely, the intellectual properties and powers. Hence, a human being is not an entirelycorporeal substance, but a partly incorporeal one. This incorporeal part carries on after thebody dies, so that there is in thiscase (unlike the case of the oak tree) something for the form to continue to bethe form of.

And that isthe sense in which the soul carries on beyond the death of the body. Yes, the soul is the form of the body,because it is the form of a substance that it partially bodily in nature. But unlike an oak or a poodle, a human being is not entirely bodily in nature, so that there is (as it were) still workfor the human soul to do even after the body is gone.

Why doesthis not make the human soul after death like an angel, the unique member ofits own distinct species? The answer isthat the soul was once conjoined to its body and always retains its orientationto that particular body. An angelwithout a body is no less an angel for that. It is complete in its incorporealmode of existence. By contrast, a humanbeing without a body (that is to say, a disembodied soul) is less of a humanbeing insofar as it is an incompletehuman being. Incorporeality is normalfor an angel, but not for a human being. This orientation toward matter, which persists even in the absence ofmatter, suffices to individuate human souls.

Of course, Billmay raise further objections, to some or all of what I’ve said here. The point, though, is to indicate why I thinkthe particular objection he raises in his post fails. (Longtime readers might remember that thisissue is in fact a matter of longstanding dispute between Bill and me. I’ve linked to some earlier posts on thesubject below.)

I want toadd in closing that I have been reading Bill’s recent book Life’s Path with pleasure and profit, and advise you to do thesame. Bill is among the rarecontemporary philosophers who live up to the traditional ideal of producing bothsolid technical academic philosophical work (as in his superb earlier book A ParadigmTheory of Existence) and insightful moral, political, and other practicalreflections accessible to a more popular audience (as in the more recentbook). Read and learn.

Relatedposts:

Vallicellaon hylemorphic dualism

October 10, 2025

Fastiggi and Sonna on Catholicism and capital punishment (Updated)

Recently, theologianRobert Fastiggi was interviewed aboutthe topic of the Church and the death penalty by apologist Suan Sonna on hispodcast Intellectual Catholicism. Fastiggi’s views are the focus of thediscussion, but Sonna, who largely agrees with him, adds some points of hisown. Their main concern in thediscussion is to try to defend the changes Pope Francis made to the Church’spresentation of her teaching on the subject.

Recently, theologianRobert Fastiggi was interviewed aboutthe topic of the Church and the death penalty by apologist Suan Sonna on hispodcast Intellectual Catholicism. Fastiggi’s views are the focus of thediscussion, but Sonna, who largely agrees with him, adds some points of hisown. Their main concern in thediscussion is to try to defend the changes Pope Francis made to the Church’spresentation of her teaching on the subject. I appreciatetheir civility, and Fastiggi’s call at the end of the interview for charity indealing with those who disagree. But theirattempt fails. Much of what Fastiggi hasto say are reheated claims that I have already refuted in past exchanges withhim, such as the two-part essay I wrote in response to his series on the deathpenalty at Where Peter Is. (You can find it hereand here. The essay was reprinted as a single longarticle in Ultramontanism and Tradition,edited by Peter Kwasniewski.) Fastiggisimply repeats his assertions without acknowledging, much less answering, myrebuttals. He also makes some new claims,which are no more plausible than the older ones. Let’s take a look.

A straw man

In anyfruitful discussion of this topic, it must constantly be kept in mind that thereare two questions that need to be clearly distinguished. First, is the death penalty intrinsicallywrong? And second, even if it is notintrinsically wrong, is it nevertheless morally better never to resort toit? To answer “Yes” to the firstquestion is to say that capital punishment ofits very nature, and regardless of the circumstances, is wrong, and thuscan never even in principle be used. Butsomeone could answer “No” to the first question and still answer “Yes” to thesecond. To take this view is to say thatwhile in theory the death penalty could be justified in certain circumstances,in practice those circumstances never obtain, at least not today, and that themoral considerations that tell against its use outweigh those that speak infavor of it.

People whocomment on the topic of Catholicism and capital punishment very frequentlyignore this distinction. The result isthat they often talk past one another and the discussion generates more heatthan light. Now, at the beginning oftheir conversation, Fastiggi and Sonna are, to their credit, careful to notethe distinction. But unfortunately, laterin their discussion, they ignore it, and this leads them to attack a straw man.

Inparticular, Fastiggi claims (after the 35 minute mark in the video) that “peoplesay, well, the Church has always taught, always allowed for the [death penalty].” Arguing against this, Fastiggi cites someFathers of the Church who were against capital punishment, and concludes that “it’salmost like a myth, this 2,000 year old tradition, but if it’s repeated enoughby commentators and writers, then people begin to believe it.” Similarly, Sonna remarks (around the 45minute mark) that “a lot of people have this impression that the Church, as ifit were this uniform block, this constant unchanging permanent wall, has justconsistently said the death penalty’s fine, you know, go ahead and do it.” But in fact, he continues, “historically,there was an uneasiness at times with the death penalty.” Fastiggi and Sonna make a big deal out of thistheme, as if it is a damning point against Catholic defenders of the deathpenalty.

But not sofast. For here too we need todistinguish two claims, namely:

(1) TheChurch always taught for 2,000 years that the death penalty is notintrinsically wrong.

(2) TheChurch always taught for 2,000 years that the death penalty is not only notintrinsically wrong, but that it is generally a good idea and should be used.

I know ofmany Catholic defenders of capital punishment who have asserted claim (1),including myself. But claim (1) is by nomeans a “myth.” It is demonstrably true,as Joseph Bessette and I document in detail in our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A CatholicDefense of Capital Punishment. Indeed, in hisown book on the subject, E. Christian Brugger, the foremost Catholictheologian who argues against capital punishment – and someone who even claimsthat the death penalty isintrinsically wrong – admits that (1) is true. In fact, even Fastiggi and Sonna appear to concede it. Fastiggi acknowledges that the Fathers hecites “don’t necessarily challenge the state’s right to [execute],” but merelyargue against exercising that right. AndSonna admits that “maybe we can’t dispute that the state has the right,technically, to do it.”

By contrast,claim (2) is indeed false, for just the reasons Fastiggi gives. But I cannot think of a single person who endorsesclaim (2) in the first place. (CertainlyJoe Bessette and I explicitly acknowledge in our book that some Fathers andpopes held that it was morally better not to resort to the death penalty.) So, when Fastiggi cites what certain of theFathers say as evidence against a “myth” he alleges many are peddling, he isattacking a thesis that no one in fact holds. It seems otherwise to him and to Sonna only because they ignore thedistinction between (1) and (2).

Misrepresenting John Paul II

Sloppinessof this kind often leads Fastiggi to misrepresent the views of his opponentsand the nature of their disagreement with him. It also leads him to misrepresent a pope he appeals to in defense of hisposition, namely Pope St. John Paul II. Aboutseven minutes into the video, Fastiggi suggests that the Church now condemnsnot only killing the innocent, but “intentional killing” as such. He says:

The reason why the Church has now developed her teaching tobe opposed to capital punishment is because it involves intentional killing,and then the question of course of whether or not a murderer loses humandignity and the right to life. Andreally, the turning point of this was St. John Paul II. In EvangeliumVitae number 9, he says not even a murderer loses his dignity.

After the 50minute mark, Fastiggi returns to the theme, and says:

I think a leap was made with the understanding that punishingpeople by intentionally killing them is an offense against the inviolability oflife. The theoretical question is, doesa serious crime take away the right to life? And John Paul II answered that in EvangeliumVitae 9. That was the breakthrough,that not even a murderer loses his dignity and right to life.

This issleight of hand. It is true that EvangeliumVitae 9 says that “not even a murderer loses his personaldignity.” But the encyclical nowheresays that a murderer does not lose his rightto life. Instead, it speaks of “theabsolute inviolability of innocenthuman life,” “the inviolable right to life of every innocent human being” and again, of “fundamental human rights,beginning with the right to life of every innocenthuman being”; it says that “as far as the right to life is concerned, everyinnocent human being is absolutelyequal to all others”; it teaches that “a law which violates an innocent person's natural right to lifeis unjust and, as such, is not valid as a law”; and it calls for “unconditionalrespect for the right to life of every innocentperson” (emphasis added). And itexplicitly allows that the execution of those guilty of the gravest offenses ispermissible “in cases of absolute necessity.” That would not be possible if the murderer never loses his right tolife.

It is truethat Evangelium Vitae also says thatbloodless means are preferable where possible because they are “more in line with human dignity” and “more in conformity to the dignity of thehuman person.” But notice that that doesnot entail that capital punishment is notat all in line with human dignity, only that it is less in line with it. (Compare: To say that Ricky is more talented than Fred does not entailthat Fred is altogether untalented; to say that Ethel is more intelligent thanLucy does not entail that Lucy is altogether unintelligent; and so on.) So, from the claim that (a) not even a murderer loses his dignity, togetherwith the claim that (b) the death penaltyis less in line with human dignity than milder punishments, it simply doesnot follow that (c) capital punishment isflatly incompatible with the murderer’s dignity, and neither does it followthat (d) the murderer does not lose hisright to life. Nor, again, does JohnPaul II draw those conclusions.

PerhapsFastiggi would say that John Paul II shouldhave drawn those conclusions, and that in failing to do so he was beinginconsistent. But there are severalproblems with such a response. First, itwouldn’t change the fact that John Paul II did not in fact draw them, and thus didnot in fact say the things Fastiggi attributes to him. Second, for the reasons I have given, theconclusions do not in fact follow logically from John Paul II’s premises, sothat the pope was not being inconsistent. Third, if there are two ways of reading a papal document, in one ofwhich it contains an inconsistency and in the other of which it does not, thesecond is to be preferred. Hence, forthat reason alone, we should reject Fastiggi’s reading. Fourth, Fastiggi’s reading would imply thatJohn Paul II was not only not consistent with himself, but also contradictedhis predecessors – such as Pope Pius XII, who taught:

Even when it is a question of the execution of a mancondemned to death, the State does not dispose of the individual's right tolive. It is reserved rather to thepublic authority to deprive the criminal of the benefit of life when already,by his crime, he has deprived himself ofthe right to live. (Address to the First International Congress on theHistopathology of the Nervous System, 1952, emphasis added)

Certainly,implicitly to accuse one pope (John Paul II) of inconsistency and another pope (PiusXII) of grave moral error is a strange way to try to defend a third pope(Francis)!

In anyevent, Joe Bessette and I provide a very detailed analysis of John Paul II’steaching at pp. 144-82 of our book. Aswe demonstrate there, when one considers the entirety of the evidence (and notjust the usual cherry-picked phrases Catholic opponents of capital punishmentlike to quote), it is crystal clear that the pope’s teaching was in no way analteration or even development of traditional doctrine, but simply a prudentialjudgment about how to apply that doctrine to contemporary circumstances. Like so many of our critics, Fastiggi offersno response at all to the arguments we give there, but pretends they don’texist.

Obfuscating on Pope Francis

Beginning atabout 12 minutes into their discussion, Fastiggi and Sonna argue that PopeFrancis has, in any event, not actually taught that the death penalty isintrinsically wrong. They focus on thepope’s 2018 revision to the Catechism, and suggest that it implicitlyacknowledges that capital punishment is permissible in theory, and simplyteaches that it is inadmissible under current circumstances.

This is adefensible position, as far as it goes. I have always myself acknowledged that the revision can and should beread in such a way that it is not teaching that capital punishment isintrinsically evil. But that is onlypart of the story. For one thing, theproblem with the revision is that this is not a natural reading of it. Therevised text characterizes the death penalty as “an attack on the inviolabilityand dignity of the person.” On a naturalreading, that seems to imply that capital punishment is intrinsically at odds with human dignity (rather than being at oddswith it only if certain conditionsfail to hold), and thus intrinsicallywrong. Yes, it need not be read thatway, but magisterial statements should be clearlyconsistent with traditional teaching, not merely consistent with it on astrained reading.

For anotherthing, other magisterial statements made during Pope Francis’s pontificate aremuch harder to reconcile with the traditional teaching. For example, in a2017 address, the pope asserted that “the death penalty is aninhumane measure that, regardless of howit is carried out, abases human dignity. It is per se contrary to theGospel” (emphasis added). Theitalicized phrases are most naturally read as claiming that capital punishmentis always and intrinsically wrong.

Some mightreply that this entails only that the death penalty is contrary to the higherdemands of Christian morality, not that it is contrary to natural law. That would be bad enough, because (as I haveshown elsewhere, such as in thisarticle) the traditional teaching of the Church is that it is not contrary to Christian morality anymore than it is contrary to natural law.

But to makematters worse, the declaration DignitasInfinita, issued by the DDF during Francis’s pontificate,implies that capital punishment iscontrary even to natural law. For itasserts that “the death penalty… violates the inalienable dignity of everyperson, regardless of the circumstances,” and that this dignity is grounded in“human nature apart from all cultural change.” The declaration also asserts that humandignity must be upheld “beyond every circumstance,” “in all circumstances,”“regardless of the circumstances,” and so on. Here there is no wiggle room for saying thatthe document judges capital punishment to be contrary to human dignity only ifcertain conditions are not met. For itflatly asserts that it violates human dignity “regardless of thecircumstances.” Nor is there any wiggleroom for saying that the document nevertheless allows in principle for such aviolation of human dignity under certain circumstances (which would be abizarre idea in any case). For itexplicitly says that human dignity “prevails in and beyond every circumstance,state, or situation the person may ever encounter,” and so on. The logical implication of all this is thatcapital punishment is absolutely ruled out as always and intrinsically wrong. And that straightforwardly contradictstraditional teaching.

Sonna, atleast, appears to acknowledge that the traditional teaching cannot bereversed. So, if he is going to beconsistent, he will have to admit that these statements issued during Francis’spontificate are problematic – that they are poorly formulated at best, anderroneous at worst (which is possible in non-ex cathedra magisterial statements).

Parallel doctrinal reversals?

Fastiggi isanother story. At around 40 minutes in,he says: “But hasn’t the Church definitively taught that the death penalty isallowed? No, it hasn’t.” And earlier, at around 25 minutes in, he saysthat “even if the Church has not yet, maybe someday she’ll say it’sintrinsically immoral, but because it had been accepted for so long we don’tneed to say that right now.”

But Fastiggiis simply mistaken. When all therelevant evidence is taken account of, it is manifest that the doctrine thatthe death penalty is not intrinsically wrong has been taught by both scriptureand the Church in an irreformable manner. I set out some of this evidence in along Catholic World Report articlefrom some years back, and Joe Bessette and I do so in greater depth in ourbook. Fastiggi says nothing even toacknowledge, much less answer, these arguments. He merely begs the question against them.

Fastiggialso says that even if the Church does not hold that the death penalty isintrinsically wrong, it doesn’t follow that its teaching against it is merely aprudential judgment which Catholics need only respectfully consider but notnecessarily follow. For the Church hasthe authority to prohibit even certain practices that are not inherentlywrong. Fastiggi gives the example ofcremation, which was for a long time prohibited by the Church but now ispermitted under certain circumstances. Healso cites polygamy and divorce, which were tolerated under the old covenantbut have been forbidden under the new covenant.

Fastiggi isright about that much, but these facts don’t suffice to show that the Churchcan do more than issue a non-binding prudential judgment against use of thedeath penalty. The reason is that it isthe state and not the Church which has the responsibility and right undernatural law to do what is necessary to ensure the safety of the community. This is why, after setting out the criteriafor fighting a just war, the Catechism goes on to say that “the evaluation ofthese conditions for moral legitimacy belongs to the prudential judgment ofthose who have responsibility for the common good” (2309). In other words, the Church can teach that awar is just only when the cause is just, there is a serious chance of success, noother options are likely to work, and so on. But the Church does not have the expertise or authority to determine howthese criteria apply in a particular case. For example, it does not have the relevant expertise to determinewhether some option other than war would suffice to repel an aggressor in aparticular case, or whether a certain military strategy is likely tosucceed. These are matters of prudentialjudgment, and it is the state rather than the Church that has the right andresponsibility to make that judgment.

But the sameapplies, mutatis mutandis, to capitalpunishment. The revision to thecatechism claims, for example, that modern systems of imprisonment aresufficient to protect others against the most dangerous offenders. But the Church has no more expertise on thatsort of issue than it does on military strategy. If government officials have good empiricalreason to believe that the death penalty saves lives – for example, if theyhave evidence that it has a significant deterrent effect, or that it is neededto protect prison guards or other prisoners from the most violent offenders –then they have just as much a right under natural law to utilize capitalpunishment as they do to fight a just war.

This sort ofreasoning does not apply to cremation, which is why it is not an interestingparallel to the case of capital punishment. The examples of polygamy and divorce also do nothing to help Fastiggi’scase, and not just because (unlike capital punishment) the state does not needto keep them open as options in order to do its job of protecting society. There is also the following glaringdisanalogy: The New Testament explicitly forbidsdivorce and clearly opposes polygamy too, as has the Church ever since. But the New Testament explicitly allows capital punishment (e.g. inRomans 13), as has the Church ever since. Cremation, polygamy, and divorce thus offer no precedent for an absoluteprohibition on capital punishment.

Fastiggi andSonna suggest other alleged doctrinal reversals that they think provide aprecedent for a reversal on capital punishment. But they are all bad analogies that provide no support whatsoever forsuch a reversal. For example, Fastiggipoints to the fact that theologians were once free to disagree about theImmaculate Conception, but later the Church made a dogmatic pronouncement onthe matter so that such legitimate disagreement is no longer possible.

The problemwith this purported analogy should be obvious. To teach that capital punishment is intrinsically wrong would directlycontradict what the Church had consistently taught for 2,000 years and what shehad always understood scripture to teach. Proclaiming the dogma of the Immaculate Conception involved nothingremotely like that. In particular, it inno way involved the Church contradictingsome doctrine she had previously taught.

Fastiggialleges that there is also a parallel between capital punishment and the caseof torture. He contrasts a passingremark on the subject from Pope Innocent I, which left its use open, with themore recent teaching of the Church condemning torture. Here too the alleged parallel isspurious. The Church holds thatscripture cannot teach moral error, and she has for two millennia acknowledgedthat scripture repeatedly sanctions capital punishment. But there is no such scriptural sanction fortorture. The Church has also for twomillennia herself consistently and clearly taught that capital punishment canunder certain circumstances be licit, to the point of including this doctrinein major teaching documents such as the catechisms of Pope St. Pius V and PopeSt. John Paul II. The teaching was alsoendorsed by the Fathers (even those who opposed the use of capital punishmentin practice), has been consistently affirmed by the Church’s greatesttheologians (including many Doctors of the Church), and routinely endorsed inapproved manuals of moral theology. Noneof this can be said of torture.

Fastiggi andSonna also suggest that the development of the Church’s teaching on slaveryprovides a precedent for a change on capital punishment. But this alleged parallel too is phony. For one thing, here too Fastiggi and Sonnamuddy the waters by ignoring long-established and crucial distinctions. For the word “slavery” is ambiguous. What most people think of when they hear thisterm is chattel slavery, whichinvolves claiming ownership of another human being in the way one might own ananimal or inanimate object. The Churchdoes indeed teach that this is intrinsically evil, but she has never taughtotherwise. Indeed, she has condemnedthis practice for centuries (as I document in my book All One inChrist: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory).

There are,however, less extreme forms of servitude that the Church has taken to be atleast in theory not unjust. Inparticular, there is penal servitude,which is forced labor in punishment for a crime. The idea here is that if the state can, inpunishment for a sufficiently grave crime, take away an offender’s liberty fora prolonged period of time (even for life), then it can also require him towork. And there is indentured servitude, a prolonged period of labor without paymentas a way to repay a debt or in exchange for some benefit. The idea here is that if someone canlegitimately enter a work contract, or have his wages garnished in order to paya debt, then by extension he can make himself a servant in order to pay a debt.

The troublewith these practices is that in concrete circumstances they are fraught withmoral hazard, and were often used to rationalize what amounted to chattelslavery (such as when captives taken in war were enslaved on the spuriousgrounds that they were guilty of the offense of fighting an unjust war, andthus could be forced into penal servitude). Hence, moral theologians settled on the view (quite correctly, I wouldsay) that when all relevant moral considerations are brought to bear, it isclear that they ought flatly to be banned altogether.

There isalso the consideration that in scripture, slavery is merely tolerated as aninstitution that happened to exist, rather than put forward as a positivegood. By contrast, the death penalty is not merely tolerated, but in some casesis positively sanctioned (not only in the Mosaic law, but in other contextssuch as Genesis 9 and Romans 13).

So, when allthe distinctions are made, the argument that “the Church reversed herself onslavery, so she can reverse herself on capital punishment” falls apart. There was no such reversal, and thus noprecedent for a reversal on capital punishment.

Magisterial credibility

This bringsus to Fastiggi’s remarks about Genesis 9 and Romans 13, where he repeats claimsthat I have already refuted in my previous exchange with him. And once again, he simply ignores rather thananswers the objections I raised there. Idirect the interested reader to thatearlier essay of mine. (Inparticular, see the sections titled “Genesis and the death penalty” and “TheMosaic Law versus the Gospel?”)

Fastiggiacknowledges that, in the instruction DonumVeritatis, the Church affirms that Catholics have the rightrespectfully to raise questions about deficient magisterial statements and askfor clarification. He says that thisnevertheless gives Catholics no right to “dissent” from the teaching of theChurch. I agree with him about allthat. But Fastiggi seems to think thatit rules out the sort of respectful criticisms that I and others with therelevant expertise have raised. It doesnot, and I have many times given arguments that show that it does not. These arguments too are ones that Fastiggisimply ignores rather than tries to answer.

For example,the criticisms I have raised with respect to the 2018 revision of the Catechismhave nothing to do with “dissenting” from some teaching of the Church. Rather, the whole point is that the teachingis unclear – that it is far from obvious exactlywhat it is that Catholics are being asked to assent to. True, the revisiondeclares that the death penalty is now “inadmissible.” But the trouble is that the force of this teaching is notobvious. Ihave argued that there are only two ways to read it. On the one hand, it might be read as claimingthat the death penalty is intrinsicallywrong and thus “inadmissible” in an absoluteand unqualified way. The problem isthat this would contradict scripture and tradition, and thus amount to adoctrinal error (something that can occur in non-ex cathedra statements). Moreover, even Fastiggi and Sonnaacknowledge that this is not the right way to read it.

But when wetake account of all the relevant considerations (both from within the documentand from the larger tradition of the Church), the only other way to read it isas saying that the death penalty is “inadmissible” unless certain conditions hold (such as that resort to it is necessaryin order to protect society). And ifthis is the case, then the teaching amounts to a non-binding prudentialjudgment. For the “unless” part is notsomething concerning which the Church has any special authority. For example, whether capital punishment has asignificant deterrence effect, and whether modern prison systems really doafford the means of protecting others from all violent offenders, are empiricalmatters of social science, not matters of faith or morals.

For sevenyears now, Fastiggi and I have been arguing about this issue, and in all thattime I have never gotten a clear answer from him about what a third possibleinterpretation would look like. In anyevent, if someone asks me “Do you dissent from the teaching of the revision ofthe Catechism?” my answer is “No, I do not dissent from it. I assent to it, and interpret it in the onlyway I know of that makes sense – namely, as a non-binding prudentialjudgment.” I also say, however, that therevision is badly formulated and potentially misleading. And I have every right respectfully to raisesuch a criticism, by the norms set out in DonumVeritatis. Fastiggi and others maycontinue to yell “Dissent!” but yelling is all they would be doing. I have yet to hear an actual argument showing that my positionamounts to dissent.

Iacknowledge that my criticism of DignitasInfinita goes beyond this. Here, Ithink we have a document that is not merely ambiguous, but very hard (at best)to defend from the charge of flatly contradicting scripture and tradition andthus being erroneous. But if someone hasa plausible way of reconciling it with scripture and tradition, I’m allears.

Even if itis indeed in error, however, this is possible in non-ex cathedra documents. Indeed, Fastiggi himself is implicitly committed to this thesis. For, again, he holds that the Church couldend up teaching that capital punishment is intrinsically immoral. And if that were correct, it would followthat for two millennia, the Church got things gravely wrong on matters of basicmoral principle and biblical interpretation. That is a very radical claim, and indeed far more radical than anything I have said. If I am right, then one pope has gottenthings wrong about capital punishment. If Fastiggi is right, then every previouspope who has taught on this topic has been wrong, as have the Fathers andDoctors of the Church (and indeed scripture itself). Fastiggi likes to paint views like mine asextreme, but in fact it is his viewsthat are extreme.

The factthat he presents them politely and under the guise of obedience to themagisterium doesn’t change that one whit. It is the content of the viewsthat matter, and the content is radically subversive of the credibility of theChurch, because it implies that the Churchmay have been gravely in error about a matter of natural law, the demands ofthe Gospel, and the proper understanding of scripture for her entire historyuntil now. And if she could be thatwrong for that long, what else might she be wrong about?

At about onehour and three minutes into the interview, Fastiggi says, with no sense ofirony: “There has to be trust in the Holy Spirit’s guidance of themagisterium. And that’s what I findmissing in many of these papal critics. They don’t trust the Holy Spirit.” Yet Fastiggi is the onesuggesting that the magisterium may have, for two millennia, consistently erredabout a grave matter of natural law, Christian morality, and scriptural interpretation. Fastiggiis the one suggesting that the Holy Spirit might have permitted this. But what is more likely – that that is thecase, or that a single pope (Francis) issued a badly formulated catechismrevision and permitted the DDF to slip a doctrinal error into a declaration? I submit that, if the Holy Spirit truly isguiding the magisterium, the scenario I posit is manifestly more plausible thanthe one Fastiggi is positing.

The realityis that the critics do trust in the HolySpirit’s guidance of the magisterium. They trust that the Holy Spirit would not have allowed the Church to bethat wrong for that long about something that important, so that it must bethose who now contradict the past magisterium who are mistaken. This has always been theoretically possible,because the Church has always acknowledged that non-definitive exercises of themagisterium can fall into error. Indeedthis has in fact happened before in the case even of papal teaching, as the famousexamples of popes Honorius I and John XXII illustrate. And Fastiggi’s own position entails it. If, as he insists, it may turn out that twomillennia of past teaching of the magisterium on capital punishment was wrong,then it follows logically that it is also possible that it is instead PopeFrancis’s statements on the subject that are wrong. And as I have shown elsewhere (hereand here),the Church has also always affirmed that there can be cases where the faithfulmay respectfully criticize the magisterium, even a pope, for teaching contraryto the tradition.

What Fastigginever seems to appreciate is that his approach damages the credibility of themagisterium by appearing to saddle it with what, in logic, is known as a “NoTrue Scotsman” fallacy. Suppose I say“No true Scotsman would be an empiricist,” and you respond “But David Hume wasan empiricist!” And suppose I reply “Well,then David Hume must not really havebeen a true Scotsman,” and that I insist that everybody has for 250 years beenmisinterpreting all the evidence that seems obviously to show that he was anempiricist. Needless to say, this wouldnot lend me or my thesis any credibility at all, but would do precisely theopposite. It would reveal me to beintellectually dishonest and unwilling to look at the evidence objectively.

Now, theFirst Vatican Council declared that “the Holy Spirit was promised to thesuccessors of Peter not so that they might, by his revelation, make known somenew doctrine.” The Second VaticanCouncil stated that “the living teaching office of the Church… is not above theword of God, but serves it, teaching only what has been handed on.” Pope Benedict XVI taught that the pope “mustnot proclaim his own ideas… he is bound to the great community of faith of alltimes, to the binding interpretations that have developed throughout theChurch's pilgrimage.”

But theliceity in principle of the death penalty has for two millennia beenconsistently taught by the Church, and has for two millennia been understood bythe Church to be the teaching of scripture, which is the word of God. Hence, for a pope to teach that the deathpenalty is intrinsically immoral would manifestly be a case of attempting to“make known some new doctrine.” It wouldmanifestly be a case of putting himself “above the word of God” instead of“teaching only what has been handed on.” It would manifestly be a case of attempting to “proclaim his own ideas”rather than being “bound to the great community of faith of all times.”

Fastiggi,however, takes the view that if a pope were to teach such a thing, then the conclusionwe should draw is that the liceity in principle of capital punishment mustafter all not really ever have beenthe teaching of scripture; that it must not reallybe a “new doctrine” but somehow implicit in what scripture and the Church havealways taught; that it must not reallyafter all have been among “the binding interpretations” to which a pope mustconform himself. And that is likedogmatically insisting that Hume must not reallyhave been a true Scotsman after all. Itgives aid and comfort to Protestant and skeptical critics of Catholicism, whoargue that the Church’s claim to continuity with scripture and tradition is asham – that at the end of the day, the popes will just teach whatever they likeand then arbitrarily slap the label “traditional” on it.

It may bethat Fastiggi is not sufficiently sensitive to this problem, whereas I havealways emphasized it, in part because of the differences in our academic andintellectual contexts. Fastiggi is atheologian teaching at a seminary, the primary job of which is the formation ofpriests. And it seems that he writespretty much exclusively for Catholic audiences. I’m a philosopher teaching at a secular college, who often writes onmatters of apologetics. And my writingis directed as much to the general public as it is to fellow Catholics. When Fastiggi sees Catholics criticizing evenobviously deficient magisterial statements, even in a respectful and well-informedway, his instinctive reaction appears to be: “It’s unseemly for Catholics to bedoing that, no matter what the pope says! Just keep quiet, and trust providence to sort it out.” When I see Catholics tying themselves inlogical knots trying to defend obviously deficient magisterial statements, myinstinctive reaction is: “Those are manifestly terrible arguments, you’remaking Catholicism look ridiculous! Justfrankly admit that there’s a problem, and trust providence to sort it out.” What Fastiggi and I agree about is thatprovidence will sort it out, but we disagree about what form this might takeand what role respectful criticism of deficient magisterial statements can play.

At the endof the day, though, such psychological speculations are not what matter. What matters is what the evidence ofscripture, tradition, and the entiretyof the magisterial history of the Church (not just the last few years of it)have to say. And as I have argued, thatevidence tells decisively against Fastiggi’s position.

UPDATE 10/18: At Substack, Suan Sonna offers some comments which clarify his position. I thank him for his civil and charitable reply.

Fastiggi and Sonna on Catholicism and capital punishment

Recently, theologianRobert Fastiggi was interviewed aboutthe topic of the Church and the death penalty by apologist Suan Sonna on hispodcast Intellectual Catholicism. Fastiggi’s views are the focus of thediscussion, but Sonna, who largely agrees with him, adds some points of hisown. Their main concern in thediscussion is to try to defend the changes Pope Francis made to the Church’spresentation of her teaching on the subject.

Recently, theologianRobert Fastiggi was interviewed aboutthe topic of the Church and the death penalty by apologist Suan Sonna on hispodcast Intellectual Catholicism. Fastiggi’s views are the focus of thediscussion, but Sonna, who largely agrees with him, adds some points of hisown. Their main concern in thediscussion is to try to defend the changes Pope Francis made to the Church’spresentation of her teaching on the subject. I appreciatetheir civility, and Fastiggi’s call at the end of the interview for charity indealing with those who disagree. But theirattempt fails. Much of what Fastiggi hasto say are reheated claims that I have already refuted in past exchanges withhim, such as the two-part essay I wrote in response to his series on the deathpenalty at Where Peter Is. (You can find it hereand here. The essay was reprinted as a single longarticle in Ultramontanism and Tradition,edited by Peter Kwasniewski.) Fastiggisimply repeats his assertions without acknowledging, much less answering, myrebuttals. He also makes some new claims,which are no more plausible than the older ones. Let’s take a look.

A straw man

In anyfruitful discussion of this topic, it must constantly be kept in mind that thereare two questions that need to be clearly distinguished. First, is the death penalty intrinsicallywrong? And second, even if it is notintrinsically wrong, is it nevertheless morally better never to resort toit? To answer “Yes” to the firstquestion is to say that capital punishment ofits very nature, and regardless of the circumstances, is wrong, and thuscan never even in principle be used. Butsomeone could answer “No” to the first question and still answer “Yes” to thesecond. To take this view is to say thatwhile in theory the death penalty could be justified in certain circumstances,in practice those circumstances never obtain, at least not today, and that themoral considerations that tell against its use outweigh those that speak infavor of it.

People whocomment on the topic of Catholicism and capital punishment very frequentlyignore this distinction. The result isthat they often talk past one another and the discussion generates more heatthan light. Now, at the beginning oftheir conversation, Fastiggi and Sonna are, to their credit, careful to notethe distinction. But unfortunately, laterin their discussion, they ignore it, and this leads them to attack a straw man.

Inparticular, Fastiggi claims (after the 35 minute mark in the video) that “peoplesay, well, the Church has always taught, always allowed for the [death penalty].” Arguing against this, Fastiggi cites someFathers of the Church who were against capital punishment, and concludes that “it’salmost like a myth, this 2,000 year old tradition, but if it’s repeated enoughby commentators and writers, then people begin to believe it.” Similarly, Sonna remarks (around the 45minute mark) that “a lot of people have this impression that the Church, as ifit were this uniform block, this constant unchanging permanent wall, has justconsistently said the death penalty’s fine, you know, go ahead and do it.” But in fact, he continues, “historically,there was an uneasiness at times with the death penalty.” Fastiggi and Sonna make a big deal out of thistheme, as if it is a damning point against Catholic defenders of the deathpenalty.

But not sofast. For here too we need todistinguish two claims, namely:

(1) TheChurch always taught for 2,000 years that the death penalty is notintrinsically wrong.

(2) TheChurch always taught for 2,000 years that the death penalty is not only notintrinsically wrong, but that it is generally a good idea and should be used.

I know ofmany Catholic defenders of capital punishment who have asserted claim (1),including myself. But claim (1) is by nomeans a “myth.” It is demonstrably true,as Joseph Bessette and I document in detail in our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A CatholicDefense of Capital Punishment. Indeed, in hisown book on the subject, E. Christian Brugger, the foremost Catholictheologian who argues against capital punishment – and someone who even claimsthat the death penalty isintrinsically wrong – admits that (1) is true. In fact, even Fastiggi and Sonna appear to concede it. Fastiggi acknowledges that the Fathers hecites “don’t necessarily challenge the state’s right to [execute],” but merelyargue against exercising that right. AndSonna admits that “maybe we can’t dispute that the state has the right,technically, to do it.”

By contrast,claim (2) is indeed false, for just the reasons Fastiggi gives. But I cannot think of a single person who endorsesclaim (2) in the first place. (CertainlyJoe Bessette and I explicitly acknowledge in our book that some Fathers andpopes held that it was morally better not to resort to the death penalty.) So, when Fastiggi cites what certain of theFathers say as evidence against a “myth” he alleges many are peddling, he isattacking a thesis that no one in fact holds. It seems otherwise to him and to Sonna only because they ignore thedistinction between (1) and (2).

Misrepresenting John Paul II

Sloppinessof this kind often leads Fastiggi to misrepresent the views of his opponentsand the nature of their disagreement with him. It also leads him to misrepresent a pope he appeals to in defense of hisposition, namely Pope St. John Paul II. Aboutseven minutes into the video, Fastiggi suggests that the Church now condemnsnot only killing the innocent, but “intentional killing” as such. He says:

The reason why the Church has now developed her teaching tobe opposed to capital punishment is because it involves intentional killing,and then the question of course of whether or not a murderer loses humandignity and the right to life. Andreally, the turning point of this was St. John Paul II. In EvangeliumVitae number 9, he says not even a murderer loses his dignity.

After the 50minute mark, Fastiggi returns to the theme, and says:

I think a leap was made with the understanding that punishingpeople by intentionally killing them is an offense against the inviolability oflife. The theoretical question is, doesa serious crime take away the right to life? And John Paul II answered that in EvangeliumVitae 9. That was the breakthrough,that not even a murderer loses his dignity and right to life.

This issleight of hand. It is true that EvangeliumVitae 9 says that “not even a murderer loses his personaldignity.” But the encyclical nowheresays that a murderer does not lose his rightto life. Instead, it speaks of “theabsolute inviolability of innocenthuman life,” “the inviolable right to life of every innocent human being” and again, of “fundamental human rights,beginning with the right to life of every innocenthuman being”; it says that “as far as the right to life is concerned, everyinnocent human being is absolutelyequal to all others”; it teaches that “a law which violates an innocent person's natural right to lifeis unjust and, as such, is not valid as a law”; and it calls for “unconditionalrespect for the right to life of every innocentperson” (emphasis added). And itexplicitly allows that the execution of those guilty of the gravest offenses ispermissible “in cases of absolute necessity.” That would not be possible if the murderer never loses his right tolife.

It is truethat Evangelium Vitae also says thatbloodless means are preferable where possible because they are “more in line with human dignity” and “more in conformity to the dignity of thehuman person.” But notice that that doesnot entail that capital punishment is notat all in line with human dignity, only that it is less in line with it. (Compare: To say that Ricky is more talented than Fred does not entailthat Fred is altogether untalented; to say that Ethel is more intelligent thanLucy does not entail that Lucy is altogether unintelligent; and so on.) So, from the claim that (a) not even a murderer loses his dignity, togetherwith the claim that (b) the death penaltyis less in line with human dignity than milder punishments, it simply doesnot follow that (c) capital punishment isflatly incompatible with the murderer’s dignity, and neither does it followthat (d) the murderer does not lose hisright to life. Nor, again, does JohnPaul II draw those conclusions.

PerhapsFastiggi would say that John Paul II shouldhave drawn those conclusions, and that in failing to do so he was beinginconsistent. But there are severalproblems with such a response. First, itwouldn’t change the fact that John Paul II did not in fact draw them, and thus didnot in fact say the things Fastiggi attributes to him. Second, for the reasons I have given, theconclusions do not in fact follow logically from John Paul II’s premises, sothat the pope was not being inconsistent. Third, if there are two ways of reading a papal document, in one ofwhich it contains an inconsistency and in the other of which it does not, thesecond is to be preferred. Hence, forthat reason alone, we should reject Fastiggi’s reading. Fourth, Fastiggi’s reading would imply thatJohn Paul II was not only not consistent with himself, but also contradictedhis predecessors – such as Pope Pius XII, who taught:

Even when it is a question of the execution of a mancondemned to death, the State does not dispose of the individual's right tolive. It is reserved rather to thepublic authority to deprive the criminal of the benefit of life when already,by his crime, he has deprived himself ofthe right to live. (Address to the First International Congress on theHistopathology of the Nervous System, 1952, emphasis added)

Certainly,implicitly to accuse one pope (John Paul II) of inconsistency and another pope (PiusXII) of grave moral error is a strange way to try to defend a third pope(Francis)!

In anyevent, Joe Bessette and I provide a very detailed analysis of John Paul II’steaching at pp. 144-82 of our book. Aswe demonstrate there, when one considers the entirety of the evidence (and notjust the usual cherry-picked phrases Catholic opponents of capital punishmentlike to quote), it is crystal clear that the pope’s teaching was in no way analteration or even development of traditional doctrine, but simply a prudentialjudgment about how to apply that doctrine to contemporary circumstances. Like so many of our critics, Fastiggi offersno response at all to the arguments we give there, but pretends they don’texist.

Obfuscating on Pope Francis

Beginning atabout 12 minutes into their discussion, Fastiggi and Sonna argue that PopeFrancis has, in any event, not actually taught that the death penalty isintrinsically wrong. They focus on thepope’s 2018 revision to the Catechism, and suggest that it implicitlyacknowledges that capital punishment is permissible in theory, and simplyteaches that it is inadmissible under current circumstances.

This is adefensible position, as far as it goes. I have always myself acknowledged that the revision can and should beread in such a way that it is not teaching that capital punishment isintrinsically evil. But that is onlypart of the story. For one thing, theproblem with the revision is that this is not a natural reading of it. Therevised text characterizes the death penalty as “an attack on the inviolabilityand dignity of the person.” On a naturalreading, that seems to imply that capital punishment is intrinsically at odds with human dignity (rather than being at oddswith it only if certain conditionsfail to hold), and thus intrinsicallywrong. Yes, it need not be read thatway, but magisterial statements should be clearlyconsistent with traditional teaching, not merely consistent with it on astrained reading.

For anotherthing, other magisterial statements made during Pope Francis’s pontificate aremuch harder to reconcile with the traditional teaching. For example, in a2017 address, the pope asserted that “the death penalty is aninhumane measure that, regardless of howit is carried out, abases human dignity. It is per se contrary to theGospel” (emphasis added). Theitalicized phrases are most naturally read as claiming that capital punishmentis always and intrinsically wrong.

Some mightreply that this entails only that the death penalty is contrary to the higherdemands of Christian morality, not that it is contrary to natural law. That would be bad enough, because (as I haveshown elsewhere, such as in thisarticle) the traditional teaching of the Church is that it is not contrary to Christian morality anymore than it is contrary to natural law.

But to makematters worse, the declaration DignitasInfinita, issued by the DDF during Francis’s pontificate,implies that capital punishment iscontrary even to natural law. For itasserts that “the death penalty… violates the inalienable dignity of everyperson, regardless of the circumstances,” and that this dignity is grounded in“human nature apart from all cultural change.” The declaration also asserts that humandignity must be upheld “beyond every circumstance,” “in all circumstances,”“regardless of the circumstances,” and so on. Here there is no wiggle room for saying thatthe document judges capital punishment to be contrary to human dignity only ifcertain conditions are not met. For itflatly asserts that it violates human dignity “regardless of thecircumstances.” Nor is there any wiggleroom for saying that the document nevertheless allows in principle for such aviolation of human dignity under certain circumstances (which would be abizarre idea in any case). For itexplicitly says that human dignity “prevails in and beyond every circumstance,state, or situation the person may ever encounter,” and so on. The logical implication of all this is thatcapital punishment is absolutely ruled out as always and intrinsically wrong. And that straightforwardly contradictstraditional teaching.

Sonna, atleast, appears to acknowledge that the traditional teaching cannot bereversed. So, if he is going to beconsistent, he will have to admit that these statements issued during Francis’spontificate are problematic – that they are poorly formulated at best, anderroneous at worst (which is possible in non-ex cathedra magisterial statements).

Parallel doctrinal reversals?

Fastiggi isanother story. At around 40 minutes in,he says: “But hasn’t the Church definitively taught that the death penalty isallowed? No, it hasn’t.” And earlier, at around 25 minutes in, he saysthat “even if the Church has not yet, maybe someday she’ll say it’sintrinsically immoral, but because it had been accepted for so long we don’tneed to say that right now.”

But Fastiggiis simply mistaken. When all therelevant evidence is taken account of, it is manifest that the doctrine thatthe death penalty is not intrinsically wrong has been taught by both scriptureand the Church in an irreformable manner. I set out some of this evidence in along Catholic World Report articlefrom some years back, and Joe Bessette and I do so in greater depth in ourbook. Fastiggi says nothing even toacknowledge, much less answer, these arguments. He merely begs the question against them.

Fastiggialso says that even if the Church does not hold that the death penalty isintrinsically wrong, it doesn’t follow that its teaching against it is merely aprudential judgment which Catholics need only respectfully consider but notnecessarily follow. For the Church hasthe authority to prohibit even certain practices that are not inherentlywrong. Fastiggi gives the example ofcremation, which was for a long time prohibited by the Church but now ispermitted under certain circumstances. Healso cites polygamy and divorce, which were tolerated under the old covenantbut have been forbidden under the new covenant.

Fastiggi isright about that much, but these facts don’t suffice to show that the Churchcan do more than issue a non-binding prudential judgment against use of thedeath penalty. The reason is that it isthe state and not the Church which has the responsibility and right undernatural law to do what is necessary to ensure the safety of the community. This is why, after setting out the criteriafor fighting a just war, the Catechism goes on to say that “the evaluation ofthese conditions for moral legitimacy belongs to the prudential judgment ofthose who have responsibility for the common good” (2309). In other words, the Church can teach that awar is just only when the cause is just, there is a serious chance of success, noother options are likely to work, and so on. But the Church does not have the expertise or authority to determine howthese criteria apply in a particular case. For example, it does not have the relevant expertise to determinewhether some option other than war would suffice to repel an aggressor in aparticular case, or whether a certain military strategy is likely tosucceed. These are matters of prudentialjudgment, and it is the state rather than the Church that has the right andresponsibility to make that judgment.

But the sameapplies, mutatis mutandis, to capitalpunishment. The revision to thecatechism claims, for example, that modern systems of imprisonment aresufficient to protect others against the most dangerous offenders. But the Church has no more expertise on thatsort of issue than it does on military strategy. If government officials have good empiricalreason to believe that the death penalty saves lives – for example, if theyhave evidence that it has a significant deterrent effect, or that it is neededto protect prison guards or other prisoners from the most violent offenders –then they have just as much a right under natural law to utilize capitalpunishment as they do to fight a just war.

This sort ofreasoning does not apply to cremation, which is why it is not an interestingparallel to the case of capital punishment. The examples of polygamy and divorce also do nothing to help Fastiggi’scase, and not just because (unlike capital punishment) the state does not needto keep them open as options in order to do its job of protecting society. There is also the following glaringdisanalogy: The New Testament explicitly forbidsdivorce and clearly opposes polygamy too, as has the Church ever since. But the New Testament explicitly allows capital punishment (e.g. inRomans 13), as has the Church ever since. Cremation, polygamy, and divorce thus offer no precedent for an absoluteprohibition on capital punishment.