Edward Feser's Blog, page 9

September 1, 2024

The problem with the “hard problem”

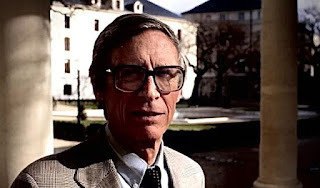

RobertLawrence Kuhn is well-known as the creator and host of the public televisionseries

Closer to Truth

, an invaluablesource of interviews with major contributors to a variety of contemporarydebates in philosophy, theology, and science. (Longtime readers will recall an exchange Kuhn and I had at First Things some years back on thequestion of why there is something rather than nothing, which you can find here,here,and here.) Recently, Kuhn’s article “Alandscape of consciousness: Toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications” appeared in the journal Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. It is an impressively exhaustive survey ofthe field, and will be extremely helpful to anyone looking for guidance throughits enormous and often bewildering literature. Kuhn kindly includes a section on my own contributions to the subject.

RobertLawrence Kuhn is well-known as the creator and host of the public televisionseries

Closer to Truth

, an invaluablesource of interviews with major contributors to a variety of contemporarydebates in philosophy, theology, and science. (Longtime readers will recall an exchange Kuhn and I had at First Things some years back on thequestion of why there is something rather than nothing, which you can find here,here,and here.) Recently, Kuhn’s article “Alandscape of consciousness: Toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications” appeared in the journal Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. It is an impressively exhaustive survey ofthe field, and will be extremely helpful to anyone looking for guidance throughits enormous and often bewildering literature. Kuhn kindly includes a section on my own contributions to the subject.The “hard problem”

Whether bydesign or not, the article marks the thirtieth anniversary since David Chalmersintroduced the phrase “hard problem of consciousness” to label what has inrecent analytic philosophy of mind become a focus of obsessive attention. Introducing the problem, Kuhn notes:

Key indeed are qualia, our internal, phenomenological, feltexperience – the sight of your newborn daughter, bundled up; the sound ofMahler's Second Symphony, fifth movement, choral finale; the smell of garlic,cooking in olive oil. Qualia – the feltqualities of inner experience – are the crux of the mind-body problem.

Chalmers describes qualia as “the raw sensations of experience.” He says, “I see colors – reds, greens,blues – and they feel a certain way to me. I see a red rose; I hear a clarinet; I smellmothballs. All of these feel a certainway to me. You must experience them toknow what they're like. You couldprovide a perfect, complete map of my brain [down to elementary particles] – what'sgoing on when I see, hear, smell – but if I haven't seen, heard, smelled formyself, that brain map is not going to tell me about the quality of seeing red,hearing a clarinet, smelling mothballs. You must experience it.”

Those lasttwo sentences indicate why qualia areregarded by so many contemporary philosophers as problematic. The problem has to do with the metaphysicalgap that seems to exist between physical facts on the one hand (including factsabout the brain) and facts about conscious experience on the other (especiallyfacts about qualia).

The natureand reality of this gap has been spelled out in various ways. Consider Chalmers’ famous “zombieargument.” It is possible atleast in principle, he says, for there to be a world physically identical toour own down to the last particle, but where there are none of the qualia ofconscious experience. Thus, in thisimagined world, there are creatures who are not only anatomically but alsobehaviorally identical to us, in that they speak and act exactly as we do inresponse to the same stimuli. But theypossess no inner life of the kind characterized by qualia. They are “zombies” in the technical sensefamiliar to readers of contemporary work in the philosophy of mind (a sensevery different from that familiar from Nightof the Living Dead and similar movies). But if they can be physically identical without possessing qualia, thenthe facts about qualia must be something over and above the physical facts.

A relatedargument known as the “knowledgeargument” was famously put forward by Frank Jackson. Imagine Mary, a scientist of the future who,for whatever reason, has spent her entire life in a black and white room, neverhaving experiences of colors. She has,nevertheless, through her studies come to learn all the physical facts thereare to know about the physics and physiology of color perception. For example, she knows down to the lastdetail what is going on in the surface of a red apple, and in the eyes andnervous system, when someone sees the apple. Suppose she leaves the room and finally comes to learn for herself whatit is like to see red. In other words,she comes for the first time to have the qualia associated with the consciousexperience of seeing a red apple. Surelyshe has learned something new. Butsince, by hypothesis, she already knew all the physical facts there were toknow about the situation, her new knowledge of the qualia in question must beknowledge of something over and above the physical facts.

As you mightexpect, the lesson many draw from these arguments is that materialism, whichholds that the physical facts are all the facts there are, is false. And this is taken to show in turn thatconsciousness will never be explicable in neuroscientific terms. But while this certainly makes qualia aproblem for the materialist, you might wonder why they would be a problem foranyone else. Can’t the dualist happilytake these implications to be, not a problem, but rather a confirmation of hisposition? But it’s not that simple. For arguments like the zombie argument alsoseem to imply that qualia are epiphenomenal, having no causal influence on thephysical world. And if qualia have nocausal influence on anything we do or say, how are we even talking aboutthem? Indeed, how can we know they arereally there?

How toresolve such puzzles, and determining whether it is materialism, dualism, orsome alternative view that will survive when they are resolved, is what the“hard problem” is all about. An enormousamount of ink has been spilled on it in recent decades, as Kuhn’s article shows. Now, philosophical work can often be of greatvalue even when it is based on erroneous presuppositions, because it can teachus about the logical relationships between certain concepts, and theconsequences of following out consistently certain philosophicalassumptions. That is why it will alwaysbe important for philosophers to study thinkers of genius who got things badlywrong (which would in my view include Heraclitus, Parmenides, Zeno, Ockham,Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Berkeley, Hume, Kant, and many others).

In myopinion, the literature on the hard problem is of value in just this way. We learn from it important things about therelationships between key philosophical ideas, such as the conceptions ofmatter and of consciousness that have dominated modern philosophy. And it shows us, in my view, that materialismis false, since the conception of matter the materialist operates with rulesout any materialist explanation of consciousness, and denying the existence ofconsciousness in order to get around this problem would be incoherent. This literature also illuminates the problemthat post-Cartesian forms of dualism have in explainingthe tight integration between mind and body that everyday experiencereveals to us to be real.

Origin of the problem

All thesame, the so called “hard problem” is, in my view, a pseudo-problem that restson a set of mistakes. There is a reasonwhy ancient and medieval philosophy knew nothing of the “mind-body problem” asmodern philosophers conceive of it, and nothing of the so-called “hard problemof consciousness” in particular. Andit’s not because they somehow overlooked some obvious features of mind andmatter that make their relationship problematic. It’s because the problem only arises if onemakes certain assumptions about the nature of mind and/or matter that ancientand medieval philosophers generally did not make, but modern philosophers oftendo make.

Points likethe ones to follow have often been made not only by Aristotelian-Thomisticphilosophers like me but also by Wittgensteinians like PeterHacker and Maxwell Bennett and Heideggerians like FrederickOlafson. The key moves thatgenerated the so-called mind-body problem can be found in Descartes, so thatThomists, Wittgensteinians, Heideggerians, and others commonly characterizethem as “Cartesian.” But variations onthese moves are found in early modern thinkers more generally.

On the sideof the body, modern philosophy introduced a conception of matter that isessentially reductionist and mathematicized. It is reductionist insofar as it essentiallytakes everyday material objects to be aggregates of microscopic particles. A stone, an apple, a tree, a dog, a humanbody – all of these things are, on this view, really “nothing but” collectionsof particles of the same type, so that the differences between the everydayobjects are as superficial as the differences between sandcastles of diverseshapes. The new conception of matter ismathematicized insofar as it holds that the only properties of the microscopicparticles are those that can be given a mathematical characterization. This would include size, shape, position in space,movement through space, and the like, which came to be called the “primaryqualities” of matter.

With color,sound, heat, cold, and other so-called “secondary qualities,” the idea was thatthere is nothing in matter itself that corresponds to the way we experiencethem. For example, there is nothing inan apple that in any way resembles the red we see, and nothing in ice waterthat in any way resembles the cold we feel. The redness and coldness exist only in our experience of the apple andthe water, in something like the way the redness we see when looking throughred-tinted glasses exists only in the glasses rather than in the objects we seethrough them. Physical objects, on thisconception, are nothing more than collections of colorless, soundless,odorless, tasteless particles. Thisincludes the brain, which is as devoid of these qualities as apples and waterare.

On the sideof the mind, meanwhile, the modern picture makes of it the repository of thesequalities that are said not truly to exist in matter. Redness, coldness, and the like, are on thisview not the qualities of physical things, but rather of our consciousexperiences of physical things. They arethe “qualia” of experience. Oftenassociated with this view is an indirectrealist theory of perception, according to which the immediate objects ofperception are not physical objects themselves, but only mental representationsof such objects. For example, when yousee an apple, the immediate object of your perception is not the apple outsideyou, but rather an inner representation of it. The situation is analogous to looking at someone who is ringing yourdoorbell through a security camera that is generating an image of the person ona computer screen. What you are directlylooking at is the screen rather thanthe person, and the colors you see on the screen are strictly speaking featuresof the screen rather than the person(even if they are caused by something really there in the person).

On theindirect realist theory of perception, conscious experience is experience ofthe inner “screen” of the mind itself rather than of the physical world. The physical world is the cause of what we see on this innerscreen, just as the person ringing your doorbell is the cause of what you seeon your computer. But we have no directaccess to it, and can know it only by inference from what we see on the innerscreen. Our awareness of the screeninvolves something called “introspection,” which is analogous to perceptionexcept that its objects are purely mental and known directly, whereas theobjects of perception are physical and known indirectly. For example, by introspection you directlyknow your experience of the apple and the reddish, sweet, fragrant, etc. qualiaof this experience. Perception involvesindirect knowledge of an external physical object that is the cause of yourhaving this experience and those qualia.

The mind asconceived of on this picture is often called the “Cartesian theater.” The reductionist-cum-mathematicizedconception of the physical world I described is often called the “mechanicalworld picture.” The modern mind-bodyproblem is essentially the problem of determining how these two pictures arerelated to one another, which is why no such problem existed in ancient andmedieval philosophy (or at least not in its mainstreams, though the ancientatomist Democritus noteda paradox facing his own position that is at least in the ballpark).

The problemis that, on the one hand, since the Cartesian theater is characterized byproperties that the mechanical world picture entirely extrudes from thematerial world, that theater itself cannot be part of the material world. Thus are we left with Cartesian dualism orsomething in its ballpark. But on theother hand, the separation between them is so radical that it becomes utterlymysterious how the Cartesian theater can get into any sort of epistemic orcausal contact with the mechanistically described material world. Thus are we left with skepticism and with theinteractionproblem or something in its ballpark.

The “hardproblem of consciousness” is just the latest riff on this post-Cartesianproblematic. On the one hand, it issaid, neuroscience can shed light on the relatively “easy problems” about howneural processes mediate between sensory input and bodily behavior, but not onthe “hard problem” of why any of this processing is associated withqualia. On the other hand, it is said, itis hard to see how qualia could be other than epiphenomenal given the “causalclosure of the physical.” The formerpoint recapitulates traditional Cartesian arguments against materialism and thelatter recapitulates the interaction problem the materialist traditionally raisesagainst the Cartesian.

Dissolution of the problem

From thepoint of view of Aristotelians, Wittgensteinians, Heideggerians and others, whatis needed is, not further efforts to try to find a way to stop this merry-go-round,but rather not to get on it in the first place. In particular, we need to abandon the backgroundmodern philosophical assumptions that generate the “hard problem of consciousness”and other variations on the mind-body problem. For instance, we need to reject the reductionist-cum-mathematicizedconception of the material world we’ve inherited from early modern philosophy’smechanical world picture. With naturalsubstances, it is simply a mistake to think of them as no more than the sum oftheir parts, and to suppose that to understand them involves determining howtheir higher-level features arise out of lower-level features in a strictly bottom-upway.

In the caseof a human being or non-human animal, it is a mistake to look for consciousnessat the level of the particles of which the body is made, or at the level of nervecells, or even at the level of the brain as a whole. Consciousness is a property of the organism as a whole. The mathematicized description of matter thatthe physicist gives us, and the neural description the physiologist gives us,are abstractions from the organism asa whole, useful for certain purposes but in no way capturing the entirety ofthe organism, any more than a blueprint captures all there is to a home. We should no more expect to findconsciousness at the level of physics or neuroscience than we should expect tofind Sunday dinner, movie night, or other aspects of everyday home life in theblueprint of a house.

We shouldalso reject the assumptions about perception and introspection inherited from post-Cartesianphilosophy of mind. As Bennett andHacker show in detail in their book PhilosophicalFoundations of Neuroscience and elsewhere,discussions of the hard problem of consciousness routinely characterize therelevant phenomena in ways that are not only tendentious, but bizarre from thepoint of view of common sense no less than of Aristotelian and Wittgensteinian philosophy.

For example,consider Chalmers’ remark, quoted above, that seeing a red rose, hearing aclarinet, and smelling mothballs all “feel a certain way.” It is common in the literature on qualia andconsciousness to see claims like this. The idea seems to be that different kinds of conscious experience aredifferentiated from one another insofar as each has a unique “feel” to it. But this is not the way people normallytalk. Suppose you asked the averageperson what it feels like to see a red rose, hear a clarinet, or smellmothballs. He might suppose that whatyou had in mind was whether these perceptions evoked certain emotions ormemories or the like. For example, hemight imagine that what you are wondering about is whether seeing the rose evokesa feeling of longing for a girlfriend to whom you once gave such a rose, orwhether hearing the clarinet evokes happy memories of first hearing a BennyGoodman record, or whether smelling mothballs generates a feeling ofnausea.

Suppose yousaid to him “No, I don’t mean anything like that. I mean, what is the feel that the experience of seeing red has even apart from thatsort of thing, and how does it differ from the feel that the experience of hearing a clarinet has?” He would likely not know what you are talkingabout. In the ordinary sense of the word“feel,” it doesn’t “feel like” anything to see a red rose or hear a clarinet. Seeing an object is one thing, hearing aclarinet played is another, and “feeling” something (like an emotion) is yetanother thing, and not at all like the first two. Discussions of qualia routinely take forgranted that there must be some special “feeling” that demarcates one experiencefrom another. But as Bennett and Hackernote, that is not how we ordinarily do in fact distinguish one experience fromanother. Instead, we distinguish them byreference to the object of theexperience (a rose versus a clarinet, say) or the modality of the experience (seeing as opposed to hearing). There is no “feel” on top of that that playsa role in distinguishing one experience from another.

Similarly,it is often said that each experience has a distinct “qualitative character” toit. There is, we are told, a “qualitativecharacter” to an experience of seeing one’s newborn daughter that is differentfrom the “qualitative character” of an experience of smelling garlic cooking inolive oil. But as Bennett and Hackerpoint out, this too is an odd way of speaking, and certainly not what the ordinaryspeaker would say. To be sure, seeingone’s newborn daughter may cause one to feel affectionate, and smelling garlic cookingin olive oil may make one hungry. Inthat sense there is a different feel or qualitative character to theexperiences. But all this means, asBennett and Hacker stress, is that personfeels a certain way as a result of the experiences. It’s not a matter of the experiences themselves possessing some sort of “feel”or “qualitative character.”

Then thereis the fact that in discussions of the hard problem, it is constantly assertedthat one’s experiences involve areddish color, a garlicky smell, and so on. But here too, that is simply not the way people ordinarily talk. They would say that the rose is red, not that their experienceof the rose is red, and that the garlichas a certain distinctive smell, not that their experience of garlic does. Common sense treats colors, smells, and the like as qualities of thingsout there in the physical world, not as the qualia of our experience of thatworld.

Now, theseodd ways of talking become intelligible (sort of, anyway) if one thinks of themind on the model of the Cartesian theater. Suppose that what we are directly aware of are only innerrepresentations of physical things, rather than the things themselves. Then it might seem that we cannot entirely distinguishdifferent experiences by reference to the objects or modalities of theexperiences. For the experiences could,on this model, be just as they are even if the physical objects didn’t existand indeed even if the organs associated with the different modalities (eyes,ears, etc.) didn’t exist. How todifferentiate them, then? Positing aunique “feel” or “qualitative character” for each experience might seemnecessary. Similarly, if it is only ourown experiences, rather than physical things themselves, that we are directlyaware of, then it is understandable why it would seem that in experiencing areddish color, a garlicky smell, etc. we are encountering the qualia of experiences rather than the qualitiesof physical objects.

Aristotelians,Wittgensteinians, Heideggerians, and others would say that this way of carvingup the conceptual territory is wrong, and that common sense is right. Of course, others would say that common sensehas it wrong, and that post-Cartesian philosophy was correct to go in thedirection it did. The point, though, isthat the “hard problem of consciousness” is not something that arises just froma consideration of the relevant phenomena. Rather, it is an artifact of a certain set of philosophical assumptionsthat are read into thephenomena. And those assumptions are byno means unproblematic or unavoidable. Indeed, the fact that they generate the “hard problem of consciousness”is itself a good reason to question them. (I have argued against the mechanical world picture and the Cartesiantheater conception of the mind in several places. For example, I do so at length in Aristotle’sRevenge, and also in ImmortalSouls, in chapters 6 and 7 especially.)

All thesame, the contemporary debate about the “hard problem” remains worthy of study –not because it teaches us where the truth about human nature lies, but ratherbecause it illuminates the nature and consequences of certain very common andtenacious errors.

August 19, 2024

Rawls’s liberal integralism

John Rawls’spolitical liberalism is no more neutral and no less religiously particular thana comprehensively Catholic society. Ielaborate in “PoliticalLiberalism and Rawlsian Religion,” my latest article at Postliberal Order.

John Rawls’spolitical liberalism is no more neutral and no less religiously particular thana comprehensively Catholic society. Ielaborate in “PoliticalLiberalism and Rawlsian Religion,” my latest article at Postliberal Order.

August 10, 2024

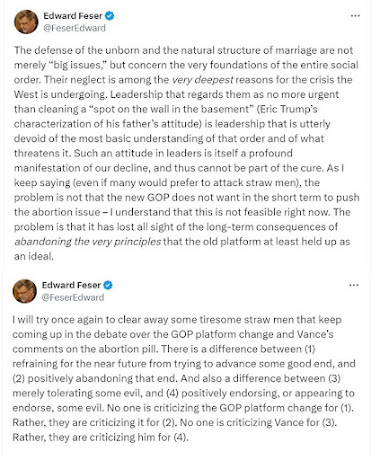

Trump has put social conservatives in a dilemma

Let’s beginwith the obvious. No social conservativecould possibly justify voting for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz. They are pro-abortion extremists, as Ryan Andersonshows in an articleon Harris at First Things andDan McLaughlin shows in an articleon Walz at National Review. Their records on other matters of concern tosocial conservatives areno better. It goes withoutsaying that they are absolutely beyond the pale.

Let’s beginwith the obvious. No social conservativecould possibly justify voting for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz. They are pro-abortion extremists, as Ryan Andersonshows in an articleon Harris at First Things andDan McLaughlin shows in an articleon Walz at National Review. Their records on other matters of concern tosocial conservatives areno better. It goes withoutsaying that they are absolutely beyond the pale. Despite hisrecent betrayal of social conservatives, Donald Trump remains lessbad on these issues. Indeed, hisappointments to the Supreme Court made possible the overturning of Roe v. Wade. It is understandable that many socialconservatives have concluded that, his faults notwithstanding, they must votefor him in order to prevent a Harris/Walz victory. The argument is a serious one. But the matter is not as straightforward asthey suppose, because the problem is not merely that Trump will no longer doanything to advance the pro-life cause. It is that his victory would likely do positive harm, indeed graveand lasting damage, to the pro-life cause and to social conservatism ingeneral.

For thatreason, a case can also be made for voting for neither Harris norTrump. Yes, a reasonable person couldjudge that the case for voting for him is stronger. But before drawing that conclusion, it isimperative for social conservatives carefully to weigh the costs, no less than the benefits, of supporting him. And it is imperative for those who do decideto vote for him not to simply close ranks and quietly acquiesce to his betrayalof social conservatives. They mustloudly, vigorously, and persistently protest this betrayal and do everything intheir power to mitigate it.

In whatfollows, I will first explain the nature and gravity of this betrayal. Then I will set out the relevant moralprinciples for deciding how to vote when faced with a choice between candidateswhose positions on matters related to abortion, marriage, and the like aregravely immoral. Finally, I will discusshow these principles apply to the present case.

Trump’s threat to social conservatism

First, let’sput aside a common straw man. Trump’spro-life critics are routinely accused of foolishly demanding that heimmediately push for a national ban on abortion or some other pro-life policyproposal that is currently politically unrealistic. But I know of no one who is demanding anysuch thing. The critics’ concerns arevery different. It is one thing simplyto refrain from pursuing pro-lifegoals for a time. It is quite anotherthing to abandon those goals outright,and yet another thing to advocate policies that are positively contrary to those goals. The trouble with Trump is not that he has done the first of these things– that much would be perfectly defensible – but rather that he has done thesecond and the third.

Considerfirst his change to the Republican party platform, which not only gutted it ofits longstanding pro-life language, but introduced elements positively contraryto the pro-life cause. The platform’slongstanding general principle that “the unborn child has a fundamentalindividual right to life which cannot be infringed” was removed. Only “late term abortion” is explicitly opposed. Not only was support for a national ban onabortion also removed, but the new platform indicates that the matter should beleft entirely to the states. Theemphasis is now not on the rights of the innocent but rather on the purelyprocedural question of who gets to determine whether and where abortion shouldbe legal. The new platform also addsthat the party supports “policies that advance… access to… IVF.” Into the bargain, the party platform’s supportfor traditional marriage was also removed.

The mannerin which these changes were made is an outrage. As reportedin First Things, theplatform process was rigged in a shockingly brazen manner so that the changescould be rammed through, with social conservatives prevented from having anyinput or even a chance to read the revised platform before voting on it. When asked whether the platform changes markeda move to the center on Trump’s part, his son Eric answeredthat his father “has alwaysbeen there on those issues, to tell you the truth” and dismissively comparedsocial conservatives’ concerns about abortion and traditional marriage to “worryingabout the spot on the wall in the basement.”

It will notdo to suggest, as some have, that the platform change was merely motivated by reasonableconcerns over the political fallout from the Dobbs decision. For onething, evenwell before Dobbs, Trumpwanted to make dramatic changes to the platform that would likely anger socialconservatives, but until now lacked sufficient control over the party to do so. For another thing, even if the controversythat followed Dobbs were the onlyconsideration, Trump did not need to change the platform in the way he did. He could have let the existing platform standwhile basically ignoring it, as he did in 2020. Or he could have merely softened the platform, preserving the generalprinciple of defending the rights of the unborn while leaving it vague how orwhen this would be done at the federal level. Nor did he need ruthlessly to bar social conservatives from having anyinfluence on the platform process. Nordid he need to add insult to this injury by having an OnlyFans porn model speak at theconvention.

Some socialconservatives have suggested that while the changes to the platform are bad,they can be reversed after Trump is elected. This is delusional. Obviously,Trump has judged that he and the GOP are now in a strong enough positionpolitically not only to ignore social conservatives, but even to rub their facesin their loss of influence, without electoral consequences. And if he wins in November, this will confirmthis judgment. There will be noincentive to restore the socially conservative elements of the platform, andevery incentive not to do so, given their unpopularity.

Thelong-term consequences for social conservatives are bound to bedisastrous. Outside the churches, socialconservatism currently has no significant institutional support beyond theRepublican Party. The universities,corporations, and most of the mass media are extremely hostile to it. And those media outlets that are less hostile(such as Fox News) tolerate social conservatives largely because of theirpolitical influence within the GOP. IfTrump’s victory is seen as vindicating his decision to throw socialconservatives under the bus, then the national GOP will be far less likely inthe future even to pay lip service to their agenda, much less to advance it. Opposition to abortion and resistance toother socially liberal policies will become primarily a matter of local ratherthan national politics, and social conservatives will be pushed further intothe cultural margins. They will graduallylose the remaining institutional support they have outside the churches (evenas the churches themselves are becoming ever less friendly to them). And their ability to fight against the moraland cultural rot accelerating all around us, and to protect themselves fromthose who would erode their freedom to practice and promote their religiousconvictions, will thereby be massively reduced.

Trump hasthus put social conservatives in a dilemma. If they withdraw their support from him, they risk helping get Harriselected, which would be a disaster both for them and for the country. But if they roll over and accept histransformation of the party for the sake of near-term electoral victory, theyrisk long-term political suicide – which would also be a disaster for them andfor the country.

But in factthe situation is much worse than that. For,again, it’s not just that Trump has gotten the GOP to abandon the goals ofsocial conservatives. It is that heendorses policies that are positivelycontrary to those goals. Forexample, when asked about whether he would block the “abortion medication”mifepristone, Trump responded:“The Supreme Court just approved the abortion pill. And Iagree with their decision to have done that, and I will not block it”(emphasis added). Echoing Trump, his runningmate J. D. Vance hasalso said that he supports mifepristone “being accessible.”

Trump’sdefenders might claim that he is merely acknowledging a Supreme Courtdecision. But as Alexandra DeSanctis haspointed out, Trump’s remarks misrepresent what happened. The court did not “approve the abortion pill.” It merely made the narrow technical determination that those who hadbrought a certain case lacked legal standing. There is nothing in the decision that requiresanyone to support keeping the abortion pill accessible. Now, the abortion pill currently accounts forover60% of abortions in the U.S. So, it’s not just that Trump has gotten the GOP to drop the stated goalof ending abortion. It’s that he positively supports preserving access to themeans responsible for the majority of abortions in the country.

It getsworse. On the one hand, Trump says thathe is in favor of letting the states decide whether to have restrictions onabortion. But he has been critical ofthose who have tried to enact such restrictions at the state level. For example, when Florida governor RonDeSantis signed a law banning abortion after six weeks, Trumpsaid: “I think what he did is a terrible thing and a terriblemistake.” When the Arizona Supreme Courtruled in favor of enforcing an abortion ban, Trumpcomplained that it “went too far.” It is worth noting that Trump ally and Arizona U.S. Senate candidateKari Lake alsodenounced the ban, and atone point even appeared to adopt Bill Clinton’s rhetoric to theeffect that abortion should “safe, legal, and rare.”

And it getseven worse. As already noted, Trump’s new GOP platformcalls for “policies that advance… access to… IVF.” He has sinceonce again “strongly” emphasized “supporting the availability of fertilitytreatments like IVF in every state in America.” But it is a routine part of the process of IVF to discard unwantedembryos. Indeed, as the National Catholic Register notes,“more human embryos [are] destroyed through IVF than abortion every year.” There is no moral difference between killingembryos during abortion and doing so as part of IVF. So, once again, it is not just that Trump isrefraining from advancing the pro-life cause. He positively supports a practicethat murders more unborn human beings than even abortion does. And here too we similar positions taken byTrump allies, suchas Senator Ted Cruz.

As theexamples of Vance, Lake, and Cruz indicate, the problem is not confined toTrump himself, but is spreading through the political movement he started. He is effectively transforming the GOP intoa second pro-choice party. Indeed, he istransforming it into a second socially liberal party. Since the Obergefelldecision did for same-sex marriage what Roehad done for abortion, the topic of same-sex marriage has receded into thebackground. The transgender phenomenonhas taken center stage in debates about sexual morality. But the legalization of same-sex marriage iswhat opened the door to it, and asI have argued elsewhere, the issues are inseparable. Once the premises by which same-sex marriagewas justified were in place, it was inevitable that what we have seen over thelast decade would follow.

Trump hassaid that he is “fine with” same-sex marriage, and, again, he removedfrom the GOP platform its statement of support for traditional marriage. Indeed, hehas made it clear that in his vision for the Republican Party, “weare fighting for the gay community, and we are fighting and fighting hard.” The president of the LGBT organization LogCabin Republicans hashailed the “radical and revolutionary” changes to the GOP platformas “one of the most important things that’s happened in Republican Partyhistory,” by which Trump “has put his DNA into the party.”

Many ofTrump’s defenders point to the overturning of Roe as evidence that, whatever his faults, he has done so much goodfor social conservatives that it is unseemly to criticize him for his lapsessince. But there are several problemswith this argument.

First, itwas by no means a sure thing that the justices Trump appointed to the SupremeCourt would vote to overturn Roe, andit is not clear that Trump himself believed they really would or even wantedthem to. that he was privately critical of state-levelmeasures to put limits on abortion even prior to Dobbs, and that when the court’s decision was revealed he “privatelytold friends and advisers the ruling will be ‘bad for Republicans’” and wasinitially reluctant to take credit. Politics rather than principle appearsalways to have been his main concern. Itseems that he favored talking aboutoverturning Roe, because he judged itto be good politics, but fretted about actuallyoverturning it because he judged that to be bad politics.

Second, the Dobbs decision, while indeed a greatvictory, nevertheless fell crucially short of what pro-lifers had actually longbeen arguing for. In order to secure amajority, the decision declined to go as far as affirming that the unborn childis a human being with the same right to life that any other innocent humanbeing has. As Hadley Arkes hasargued, this defect helped open the door to the problems thepro-life movement has faced since Dobbs.

Third, it issilly to pretend that because a politician (or anyone else) does somethinggood, he ought to be given a pass when he does something bad. And in any event, overturning Roe was for pro-lifers never an end initself, but only a means to the end of banning abortion. It is quite preposterous to expect them to beso thankful to Trump for providing this means that they refrain fromcriticizing him for doing things that are positively contrary to that end.

By no meanscan it be denied that Harris, Walz, and the Democratic Party in general areworse on the issues that concern social conservatives. They are more extreme on abortion and onLGBT-related matters, and a threat to the religious liberty of socialconservatives. But the fact remains thata Trump victory is bound to ratify his transformation of the GOP. It will no longer be a socially conservativeparty, but a second and more moderate socially liberal party.

How should social conservatives vote?

Catholicmoral theology provides guidelines for voters in situations like this, andbecause these guidelines are matters of natural law, they can also be useful tosocial conservatives who are not Catholic.

The firstthing to emphasize is that the issues we have been discussing are the most fundamental of all politicalissues. The family is the basic unit ofall social order, and it is grounded in marriage, which exists for the sake ofthe children to which it naturally gives rise. And the protection of innocent human life is the fundamental duty ofgovernment. A society that attacks thenatural structure of marriage, that makes of a mother’s womb anything but thesafest place in the world for a child to be, and whose governing authoritiesrefuse to protect the most helpless of the innocent, is a society that iscorrupt in its very foundations. Mattersof economics, foreign policy, and the like are all of secondaryimportance.

Twenty yearsago, in “OnOur Civic Responsibility for the Common Good,” Archbishop (nowCardinal) Raymond Burke set out the moral principles which Catholic theologysays ought to guide voters. Afterdiscussing abortion and other threats to innocent life, and same-sex marriage,he wrote:

Among the many “social conditions” which the Catholic musttake into account in voting, the above serious moral issues must be given the first consideration. The Catholic voter must seek, above every other consideration, toprotect the common good by opposing these practices which attack its veryfoundations. Thus, in weighing all ofthe social conditions which pertain to the common good, we must safeguard, before all else, the good of human lifeand the good of marriage and the family. (Emphasis added)

Similarly,the 2002 document “TheParticipation of Catholics in Political Life,” issued by the CDFunder then-Cardinal Ratzinger, teaches:

A well-formed Christian conscience does not permit one tovote for a political program or an individual law which contradicts thefundamental contents of faith and morals… When political activity comes upagainst moral principles that do not admit of exception, compromise orderogation, the Catholic commitment becomes more evident and laden withresponsibility… This is the case with laws concerning abortion and euthanasia…Such laws must defend the basic right to life from conception to natural death. In the same way, it is necessary to recallthe duty to respect and protect the rights of the human embryo. Analogously, the family needs to besafeguarded and promoted, based on monogamous marriage between a man and a woman…In no way can other forms of cohabitation be placed on the same level asmarriage, nor can they receive legal recognition as such.

So crucialare these issues that some moral theologians seem to hold that any candidatewho takes an immoral position on them must, accordingly, flatly be disqualifiedfrom consideration under any circumstances. For example, Fr. Matthew Habiger argues:

Can a Catholic in good conscience vote for a politician whohas a clear record of supporting abortion? Or is it a sin to vote for a politician whoregularly uses his public office to fund or otherwise encourage the killing ofunborn children? I take the positionthat it is clearly a sin to vote for such a politician…

The argument can be made that voting is a very remote form ofcooperation in abortion. But is it allthat remote? The legislator who votesfor abortion is clearly a formal accomplice, giving formal cooperation withabortion. S/he shares both in theintention of the act, and in supplying material support for the act. If I vote for such a candidate, knowing fullwell that he will help make available public monies for abortion, or continueits decriminalization, then I am aiding him/her…

It is not sufficient to think that, since candidate X takesthe ‘right position’ on other issues such as the economy, foreign relations,defense, etc. but only goes wrong on abortion, one can in good conscience, votefor him/her. Abortion deals with the first and most basic human right, without whichthere is nothing left to talk about.

CardinalBurke seems, at least at first glance, to take a similar position, when hewrites:

It is sometimes impossible to avoid all cooperation withevil, as may well be true in selecting a candidate for public office. In certain circumstances, it is morallypermissible for a Catholic to vote for a candidate who supports some immoralpractices while opposing other immoral practices. Catholic moral teaching refers to actions ofthis sort as material cooperation, which is morally permissible when certainconditions are met…

But, there is no element of the common good, no morally goodpractice, that a candidate may promote and to which a voter may be dedicated,which could justify voting for a candidate who also endorses and supports thedeliberate killing of the innocent, abortion, embryonic stem-cell research,euthanasia, human cloning or the recognition of a same-sex relationship aslegal marriage. These elements are sofundamental to the common good that they cannot be subordinated to any othercause, no matter how good.

Thesearguments seem to imply that a candidate’s support for abortion or same-sexmarriage are absolutely disqualifying,so that the principle of double effect cannot justify voting for such acandidate even when there is noviable alternative candidate who does not support these things.

However,that is a more stringent position than the Church and moral theologians havetraditionally taken, and on closer inspection Cardinal Burke does not seem tointend it. For he goes on to say:

A Catholic may vote for a candidate who, while he supports anevil action, also supports the limitation of the evil involved, if there is nobetter candidate. For example, acandidate may support procured abortion in a limited number of cases but beopposed to it otherwise. In such a case,the Catholic who recognizes the immorality of all procured abortions mayrightly vote for this candidate over another, more unsuitable candidate in aneffort to limit the circumstances in which procured abortions would beconsidered legal. Here the intention ofthe Catholic voter, unable to find a viable candidate who would stop the evilof procured abortion by making it illegal, is to reduce the number of abortionsby limiting the circumstances in which it is legal. This is not a question of choosing the lesserevil, but of limiting all the evil one is able to limit at the time…

Thus, a Catholic who is clear in his or her opposition to themoral evil of procured abortion could vote for a candidate who supports thelimitation of the legality of procured abortion, even though the candidate doesnot oppose all use of procured abortion, if the other candidate(s) do notsupport the limitation of the evil of procured abortion. Of course, the end in view for the Catholicmust always be the total conformity of the civil law with the moral law, thatis, ultimately the total elimination of the evil of procured abortion.

Similarly,then-Cardinal Ratzinger, in a2004 memo which emphasizes the necessity of Catholic politicians andvoters to oppose abortion and euthanasia, allows that:

When a Catholic does not share a candidate’s stand in favourof abortion and/or euthanasia, but votes for that candidate for other reasons,it is considered remote material cooperation, which can be permitted in thepresence of proportionate reasons.

Naturally,among the proportionate reasons that may justify such a vote would be that thealternative viable candidates are even worse on issues like abortion andeuthanasia, as Cardinal Burke says. Burke adds some further important points:

[M]aterial cooperation… is morally permissible when certainconditions are met. With respect to thequestion of voting, these conditions include the following: 1) there is noviable candidate who supports the moral law in its full integrity; 2) the voteropposes the immoral practices espoused by the candidate, and votes for thecandidate only because of his or her promotion of morally good practices; and3) the voter avoids giving scandal by telling anyone, who may know for whom heor she has voted, that he or she did so to advance the morally good practicesthe candidate supports, while remaining opposed to the immoral practices thecandidate endorses and promotes.

This thirdcondition merits special emphasis. Somewho argue for voting for Trump as the less bad of two bad options have alsobeen very critical of those who publicly criticize Trump for his betrayal ofthe pro-life cause and of social conservatives. Such criticism, they worry, might lose him votes. But as Burke’s remarks indicate, one problemwith this attitude is that it threatens to give scandal. It “sends the message” that socialconservatives put politics over principle, and that winning elections is moreimportant to them than the ends for which they are supposed to be winningelections in the first place, such as protecting innocent life and theinstitution of marriage. I would addthat another problem is that if politicians who take immoral positions onabortion, same-sex marriage, and the like are not publicly criticized for doingso, this will encourage them to continue taking these positions in the future,or even more extreme positions. Suchpoliticians should be made to fearthat they will lose votes, since nothing else is likely to deter them.

There is afurther consideration. As Germain Grisezpoints out in his treatment of the ethics of voting in Volume 2 of The Way of the Lord Jesus:

Since politics is an ongoing process, votes can haveimportant political effects even when not decisive. The size of the vote by which a candidate winsoften affects the candidate’s power while in office. Hence, it usually is worthwhile to use one’svote to widen the margin by which a good candidate wins or narrow the margin bywhich a bad one wins. Moreover, the sizeof a losing candidate’s vote often determines whether he or she will again benominated or run for the same office or another one. From this perspective, too, it often isworthwhile to use one’s vote for a good candidate or against a bad one. (p.870)

Here is oneway this consideration is relevant to the question at hand. Suppose Trump not only won the election, butwon by a wide margin, or won without losing a significant number of sociallyconservative voters. This wouldencourage the GOP in the future to maintain Trump’s changes to the party andcontinue its trajectory in a more socially liberal direction. But suppose instead that Trump won by a verynarrow margin, or won but lost many socially conservative voters in theprocess, or lost because many socially conservative voters defected. Thatwould encourage the GOP to reverse course, and move back in a more sociallyconservative direction lest it permanently alienate a major part of itstraditional voter base.

I have beenemphasizing abortion and same-sex marriage, but obviously there are otherimportant issues too. On inflation,crime, immigration, appointing judges, and so on, Harris is in my opinionmanifestly far worse than Trump. Indeed,the Democrats in general are in my view now so extremely irresponsible on thesematters that voting for them is unimaginable even apart from their depravedviews on abortion, marriage, transgenderism, and related issues. It is important to acknowledge, however, thateven if he is not as bad as the Democrats, Trump too has grave deficiencieseven apart from his betrayal of social conservatives. The most serious of these is his attempt,after the 2020 election, to pressure then-Vice President Mike Pence to setaside Electoral College votes from states Trump contested – something Pence had noauthority to do. This was avery grave affront to the rule of law, and should have been sufficient toprevent Republican voters from ever nominating him again.

But they did nominate him, so the question is whatto do now, in light of the principles I’ve just been setting out. The first thing to say is that, though otherissues are of course important, competing candidates’ positions on matters suchas abortion and marriage are mostimportant. For Catholics and otherscommitted to a natural law approach to politics, comparing candidates’positions on these matters is the first and most fundamental step indetermining how to vote, and only after that should other issues beconsidered. And as I have already said,the fact that Harris and Walz are worse than Trump on these issues suffices todisqualify them, by the criteria of Catholic moral theology I’ve beendiscussing. The question is not whetherto vote for Trump or Harris – no one should vote for Harris. The question is whether to vote for Trump orinstead to vote for neither of the major candidates (by voting for a thirdparty candidate, or for a write-in candidate, or by leaving this part of theballot blank).

The argumentfor voting for Trump is that Harris and the Democrats would do far more damageto the country, not least in the respects social conservatives most careabout. The argument for sitting theelection out is that the GOP must be punished – either by losing or by onlynarrowly winning – for moving in a socially liberal direction, since its doingso will do enormous damage to the country in the long run unless the loss ofvotes convinces the party to reverse course.

These are inmy opinion both powerful arguments. Andtogether they imply that the least bad result would be one where Trump wins,but only narrowly, and in particular in such a way that it is manifest that theGOP will in future lose the votes of social conservatives (and thus loseelections) if it does not reverse the socially liberal direction Trump hastaken it in. Unfortunately, theindividual voter cannot guarantee this result, because he can control only howhe votes, not how others vote. He can’tensure that Trump gets just enough votes narrowly to win, but loses enoughvotes to punish the GOP for its betrayal of social conservatives.

But thereare nevertheless some general considerations to guide socially conservativevoters here. One of them is that thosewho reside in states that Trump will definitely not win anyway should not votefor him, but either abstain or vote for some other conservative candidate as aprotest. For example, I live inCalifornia (which Trump will definitely lose anyway) and I will not vote forhim, but will instead, as a protest, cast a write-in vote for Ron DeSantis (whoin my opinion was clearly the candidate GOP primary voters should have chosen –though that is neither here nor there for present purposes). I have also publicly been very critical ofTrump’s betrayal of social conservatives, and have tried to do what I can in mycapacity as a writer to encourage others to make their displeasure known.

Meanwhile, sociallyconservative voters in swing states could, by the criteria set out by Ratzingerand Burke, justify voting for Trump as the less bad of two bad candidates. But a condition on their doing so is that theymust neither approve of nor keep silent about Trump’s betrayal of the unbornand of social conservatives. They mustmake their disapproval publicly known in whatever way they are able, so as toavoid scandal and pressure the GOP to reverse the socially liberal course Trumpis putting it on.

The aim ofthis strategy is, again, to prevent the grave damage that Harris would do tothe country, while at the same time preventing the long-term grave damage thatwould be done to the country by having both major parties become pro-choice andsocially liberal. Trump’s winning is necessaryfor the first, and his winning only narrowly and in the face of strong socialconservative resistance is necessary for the second.

That,anyway, is my considered opinion. Iwelcome constructive criticism. But Iask my fellow social conservatives who disagree with me seriously to considerthe gravity of the situation Trump has put us in, and the imperative not to letpartisan passions overwhelm reason and charity when debating what to do aboutit. ThomasMore, patron saint of statesmen, pray for us.

August 6, 2024

Damnation roundup

The realityof hell is the clear and infallible teaching of scripture and tradition. I would argue that even purely philosophicalargumentation can establish that the soul that is in a state of rebellionagainst God at death will remain that way forever. The universalist heresy denies these truths,and insists that all will be saved. Ithas in recent years seen a remarkable rise in popularity. In Catholic circles, Balthasar’s view thatthere is at least a reasonable hopethat all human beings will be saved has also gained currency.

The realityof hell is the clear and infallible teaching of scripture and tradition. I would argue that even purely philosophicalargumentation can establish that the soul that is in a state of rebellionagainst God at death will remain that way forever. The universalist heresy denies these truths,and insists that all will be saved. Ithas in recent years seen a remarkable rise in popularity. In Catholic circles, Balthasar’s view thatthere is at least a reasonable hopethat all human beings will be saved has also gained currency.These are extremelygrave delusions which, by fostering complacency, are sure to add to the numberof the damned. In reality, there is noreasonable hope whatsoever that all are saved. The relevant philosophical and theological considerations make this conclusionunavoidable. I have addressed theseissues in some depth in many articles over the years, and it seemed to me agood idea to collect them in one place for readers who might find thatuseful.

My most detailedand academic presentation of the philosophical considerations showing that asoul that is locked on evil at death will remain so perpetually can be found inmy New Blackfriars article “Aquinason the Fixity of the Will After Death” and in chapter 10 of my book ImmortalSouls: A Treatise on Human Nature.

I have alsoaddressed this issue, along with other questions that frequently arise inconnection with the idea of damnation, in a series of articles here at theblog. Why can a soul that is damned notrepent? Is there a sense in which Goddamns us, or are we damned only insofar as we damn ourselves? Would annihilation not be a more suitablepunishment than perpetual suffering? Couldwe really be happy in heaven knowing that some are in hell? Might we deny that hell is everlasting withoutalso denying that heaven is everlasting? If there is no hell, why is it urgent torepent and be baptized? Is it hateful towarn people that they are in danger of hell? Wouldn’t it be pointless for God to create people who end updamned? These and other questions areaddressed in the following posts:

Speaking(what you take to be) hard truths ≠ hatred

The evidencefrom scripture, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and the Magisterium thatthe reality of hell has been infallibly taught is overwhelming. I set this evidence out, and address somecommon attempts to get around it, in the following articles:

Scriptureand the Fathers contra universalism

Popes,creeds, councils, and catechisms contra universalism

In recentyears, the most influential defender of universalism has been David BentleyHart. At Catholic Herald, I reviewed Hart’s book That All Shall Be Saved:

DavidBentley Hart’s attack on Christian tradition fails to convince

Hart respondedto this review, and in reply to his response I wrote the following much more detailedcritique of his book:

I had reasonto revisit Hart’s arguments in a further article:

I addressBalthasar’s views and the dangerous complacency they foster in another seriesof articles:

Finally, afew posts that are not on the topic of hell per se, but are relevant. I would suggest that contemporary discomfort withthe doctrine of hell is, at least in part, more a reflection of the softness ofmodern Western society than a genuinely Christian understanding of the divinenature and the human condition. Modern peoplesimply cannot fathom a God who would permit great suffering, much less a Godwho would actually inflict it as punishment. But Christianity has always taught that suffering is necessary even forthe righteous, and is a feature rather than a bug of salvation history. And if even the righteous must suffer, howmuch more the unrepentant wicked? A few relevantarticles are:

The“first world problem” of evil

Augustineon divine punishment of the good alongside the wicked

July 24, 2024

Word on Fire Institute course

My six-partvideo course on Six Arguments for theExistence of God is available for free from the Word on Fire Institute. A short preview and sign-up information are availablehere. An interview about the course can be read here.

My six-partvideo course on Six Arguments for theExistence of God is available for free from the Word on Fire Institute. A short preview and sign-up information are availablehere. An interview about the course can be read here.

July 20, 2024

More on the GOP and social conservatism

For thosenot following me on X (Twitter), someposts from the last couple of days attempting further to clarify what is at issue, andat stake, in the debate over the direction of the GOP:

July 17, 2024

Now is the time for social conservatives to fight

Readers who follow me on X (Twitter) will know of theintense debate occurring there over the last week between social conservativescritical of Trump’s gutting of the GOP platform and those defending it. A pair of bracing, must-read articles at FirstThings and NationalReview recount how pro-lifers were brazenly shut out of the platformprocess. For social conservatives toacquiesce out of partisan loyalty would be to commit assisted politicalsuicide. Today I posted the following,which elaborates on considerations I raised in anearlier article:

A brief memoto social conservatives worried that criticism of the GOP will cost it votes,and who claim that the critics are politically naïve:

First, yes,criticism could cost the party votes. That’s precisely the point. The party couldlose votes IF, in the months remaining before the election, it does not try seriouslyto meet the concerns of social conservatives. In particular, the GOP must bemade to see that it cannot take their votes for granted. And the party must dosomething to make up for the appalling injustice that was done to socialconservatives during the platform process, as recounted in the First Things article linked to.

Second, itis not the critics, but those who urge their fellow social conservatives tokeep their mouths shut, who are politically naïve. The only thing politicianscan be relied on to respond to is the prospect of losing votes or losing money.If the GOP fears that it might lose the votes or financial contributions of acritical mass of social conservatives, it will have to take their concernsseriously. If, instead, social conservatives acquiesce to what has happenedrather than fighting back, the party will have no incentive to try to addresstheir concerns in the future – and every incentive not to do so, given theunpopularity of social conservatism in the culture at large.

The stakesare high, and that is precisely why social conservatives must raise the alarmNOW, while they might still influence the direction of the party, not in somefantasy post-election future. The actual political reality is that if the GOPwins, having thrown social conservatives under the bus without any pushbackfrom them, the party will draw the lesson that it no longer needs to worryabout them or their concerns.

July 14, 2024

Fight, yes, but for what?

It isimpossible not to admire the resilience and fighting spirit with which DonaldTrump responded – literally within moments – to the failed attempt to take hislife. And that he is among the luckiestof politicians is evidenced not just by his survival, but by the fact that the momentwas captured in photographs as dramatic as any seen in recent history. His supporters are understandably inspired,indeed electrified. And his enemies aresure to be demoralized by the sympathy this event will generate – not tomention the blinding contrast between Trump’s virility and the acceleratingdecline of his doddering opponent. Naturally,that those enemies include some very bad people only reinforces Trump’ssupporters’ devotion to him, which is now at a fever pitch. But it is precisely at moments of highemotion that the cold water of reason, however unpleasant, is most needed.

It isimpossible not to admire the resilience and fighting spirit with which DonaldTrump responded – literally within moments – to the failed attempt to take hislife. And that he is among the luckiestof politicians is evidenced not just by his survival, but by the fact that the momentwas captured in photographs as dramatic as any seen in recent history. His supporters are understandably inspired,indeed electrified. And his enemies aresure to be demoralized by the sympathy this event will generate – not tomention the blinding contrast between Trump’s virility and the acceleratingdecline of his doddering opponent. Naturally,that those enemies include some very bad people only reinforces Trump’ssupporters’ devotion to him, which is now at a fever pitch. But it is precisely at moments of highemotion that the cold water of reason, however unpleasant, is most needed.In the weekbefore the assassination attempt, a fierce controversy began to arise withinconservative ranks over some radical changes to the Republican Party platform madeat Trump’s insistence, and apparently rammedthrough without allowing potential critics sufficient time to study them ordeliberate. The changes involved guttingthe platform of the staunchly pro-life position that has in some form or otherbeen in it for almost fifty years, and also removing the platform’s statementof support for the traditional understanding of marriage. The platform no longer affirms the fundamentalright to life of all innocent human beings. Instead, it opposes only late term abortions, while leaving it to thestates to determine whether there should be any further restrictions, and explicitlyendorses IVF (which typically involves the destruction of embryos).

In short, theplatform now essentially reflects a soft pro-choice position rather than aclear anti-abortion position. As Robert P.George has noted,the platform has in this respect become what liberal Republicans like ArlenSpecter had long but heretofore unsuccessfully tried to make it. That would be alarming enough by itself, butit is made more so when seen in light of other recent moves by once pro-life Republicansin the direction of watering down their opposition to abortion. For example, Senator J.D. Vance, apparentlythe frontrunner for the position of Trump’s running mate, has said that hesupports access to the abortion pill mifepristone, which is said to beresponsible for half of the abortions in the U.S. Senator Ted Cruz supportsIVF, despite the destruction of embryos that it entails. Arizona U.S. Senate candidate Kari Lake hasdenounced a ban on abortion she once supported, and atone point even appeared to adopt Bill Clinton’s rhetoric to the effect thatabortion should “safe, legal, and rare.”

Trumphimself now not only favors keeping abortion legal in cases involving rape,incest, and danger to the mother’s life, but declines to say much more, otherthan that the matter should be left to the states. He no longer treats the abortion issue asfundamentally about protecting the rights of innocent human beings, but insteadas a merely procedural question concerning which level of government shouldmake policy on the matter. Nor do most observersseriously believe that abortion (much less the defense of traditional marriage)are issues that Trump is personally much concerned about, given his notoriouspersonal life and the pro-choice and otherwise socially liberal views heexpressed for decades before running for president in 2016. The most plausible reading of Trump’s recordis that he was willing to further the agenda of social conservatives when doingso was in his political interests, but has no inclination to do so any longer nowthat their support has been secured and their views have become a politicalliability.

Some socialconservatives have defended the change to the platform precisely on thesepolitical grounds, arguing that they cannot accomplish anything unless thecandidates who are least hostile to them first win elections. They note that a federal ban on abortion ishighly unpopular and has no chance of occurring in the foreseeable future, sothat for Trump to push for such a ban would be politically suicidal. But the problem with this argument is thatTrump does not need radically to change the platform in order to win theelection. For one thing, even hisbitterest opponents have for some time judged that he is likely to win theelection anyway, despite the unpopularity of the GOP’s traditional stance onabortion. For another thing, he could letthe existing platform stand while basically ignoring it. Or he could have merely softened the platform,preserving the general principle of defending the rights of the unborn whileleaving it vague how or when this would be done at the federal level.

In short, itis one thing to refrain from advancinga certain position, and quite another positivelyto abandon that position. The mostthat Trump would need to do for political purposes is the former, but thechange to the platform goes beyond this and does the latter. If this change stands, the long-termconsequences for social conservatives could be disastrous. Outside the churches, social conservatism hasno significant institutional support beyond the Republican Party. The universities, corporations, and most of themass media are extremely hostile to it. And those media outlets that are less hostile (such as Fox News)tolerate social conservatives largely because of their political influencewithin the GOP.

Some social conservativeshave suggested that while the change to the platform is bad, it can be reversedafter Trump is elected. This isdelusional. Obviously, the change hasbeen made because Trump judges that, politically, the best course of action isto appease those who are hostile to social conservatism and gamble that socialconservatives themselves will vote for him anyway. If he wins – and especially if he wins without significant pushback from social conservativeson the platform change – then this will be taken to be a vindication of thejudgment in question. There will be no incentiveto restore the socially conservative elements of the platform, and everyincentive not to do so.

The resultwill be that the national GOP will be far less likely in the future to advancethe agenda of social conservatives, or even to pay lip service to it. Opposition to abortion and resistance to othersocially liberal policies will become primarily a matter of local rather thannational politics, and social conservatives will be pushed further into the culturalmargins. They will gradually lose theremaining institutional support they have outside the churches (even as thechurches themselves are becoming ever less friendly to them). And their ability to fight against the moraland cultural rot accelerating all around us, and to protect themselves fromthose who would erode their freedom to practice and promote their religiousconvictions, will thereby be massively reduced.

In short, forsocial conservatives to roll over and accept Trump’s radical change to theRepublican platform would be to seek near-term electoral victory at the cost oflong-term political suicide. Robert P.George, Ryan Anderson, Albert Mohler, and other socially conservative leaders have called onthe delegates at this week’s Republican National Convention to vote down therevised platform and recommit to the party’s traditional pro-life position. It is imperative that all socialconservatives join in this effort in whatever way they are able.

July 12, 2024

The future of the Magisterium

The latest issue of First Things features a symposium on thefuture of the Catholic Church, to which I contributed an article on the futureof the Magisterium. You can read the entiresymposium online here.

The latest issue of First Things features a symposium on thefuture of the Catholic Church, to which I contributed an article on the futureof the Magisterium. You can read the entiresymposium online here.

July 11, 2024

Rawls on religion

Though JohnRawls wrote much that is of relevance to religion – and in particular, to thequestion of what influence it can properly have on politics (basically none, inRawls’s view) – he wrote little on religion itself. After his death, his undergraduate seniorthesis, titled

ABrief Inquiry into the Meaning of Sin and Faith

, waspublished. Naturally, it is of limitedrelevance to his mature thought. However, published in the same volume was a short 1997 personal essaytitled “On My Religion,” which is not uninteresting as an account of thedevelopment of his religious beliefs. Ithink it does shed some light on his political philosophy. From Rawls’s best-known works, theconservative religious believer is bound to judge Rawls’s knowledge andunderstanding of religion to be shallow. And indeed, I think his views on these matters were shallow. But as the essay reveals, that is not becausehe didn’t give much thought to them.

Though JohnRawls wrote much that is of relevance to religion – and in particular, to thequestion of what influence it can properly have on politics (basically none, inRawls’s view) – he wrote little on religion itself. After his death, his undergraduate seniorthesis, titled

ABrief Inquiry into the Meaning of Sin and Faith

, waspublished. Naturally, it is of limitedrelevance to his mature thought. However, published in the same volume was a short 1997 personal essaytitled “On My Religion,” which is not uninteresting as an account of thedevelopment of his religious beliefs. Ithink it does shed some light on his political philosophy. From Rawls’s best-known works, theconservative religious believer is bound to judge Rawls’s knowledge andunderstanding of religion to be shallow. And indeed, I think his views on these matters were shallow. But as the essay reveals, that is not becausehe didn’t give much thought to them.In his earlylife, Rawls was an Episcopalian, and he was religious enough to have consideredgoing to the seminary. He lost faith intraditional Christianity while serving as a soldier during World War II, and headmits that he does not know for certain what the reasons were. But they seem to have had primarily to dowith the problem of evil, and in particular with the way the significance ofthat problem was impressed on him by experiences he had during the war, such asthe death of a friend and learning of the Holocaust. Not unrelatedly, he later came to findChristian doctrines such as predestination and damnation morallyobjectionable. In general, he says, hisdifficulties with Christianity had to do with moral matters, rather thanevidential ones such as the question of whether there are any good argumentsfor God’s existence.

What he hasto say about all this is pretty commonplace and doesn’t add anything new toskeptical arguments already familiar (not that it was meant by Rawls to addanything – he’s just summarizing the considerations that he personally foundmost significant). Rawls also expressesthe view – totally wrong in my opinion, but common in the late twentieth centuryespecially – that arguments for God’s existence like Aquinas’s lack anyreligious significance. For reasons I’veexplained elsewhere,I don’t think someone could properly understand those arguments and still saythat. But Rawls merely makes a passingremark to this effect, so there’s no actual worked-out position there tocomment on.

This much ispretty pedestrian and wouldn’t make the article of much interest (though infairness to Rawls, it was not written for publication, and starts outexplicitly saying that his personal religious development was not especiallyunusual or likely to be of interest to anyone else). However, there are several other remarks hemakes that are of interest for the light they shed on how Rawls’s views aboutreligion influenced his political philosophy.

First, Rawlsis fairly frank about his hostility to Catholicism in particular. He says that the history of the Inquisitionwas of special interest to him in the years immediately after the war, and heis critical of the Church’s “use of political power to establish its hegemonyand to oppress other religions” (p. 264). He indicates that it is natural that it would do so, given that it is “areligion of eternal salvation requiring true belief,” so that “the Church sawitself as having justification for its repression of heresy” (pp. 264-5). He says that he has “come to think of thedenial of religious freedom and liberty of conscience as a very great evil, andfor me it makes the claims of the Popes to infallibility impossible to accept”(p. 265). These freedoms and liberties,he goes on to tell us, would become “fixed points of my moral and politicalopinions” and “basic political elements of my view of constitutional democracy”(Ibid.). It is significant that his judgment on papal infallibility remainsharsh despite his acknowledgement of the qualifications Catholicism puts onit. It is also significant that he doesnot mention the teaching of Vatican II on religious liberty, which seems tohave been irrelevant to him in evaluating Catholicism. That the popes are said to be infallibleunder certain circumstances, yet the Church once claimed and used temporalpower in the way she did, is for him enough to falsify the doctrine.

It is noteworthythat some of Rawls’s basic political convictions traced precisely to ahostility to the medieval Church and its doctrinal inflexibility and claims todivine authority, since that was, of course, true also of progenitors of theliberal tradition like Hobbes and Locke. Rawls, widely considered the most influential modern theorist ofliberalism, is in this way very much in line with the early liberal traditionand its primary concerns.

A secondnoteworthy set of remarks made by Rawls evinces hostility to Christianity moregenerally. He says that “to the extentthat Christianity is taken seriously, I came to think it could have deleteriouseffects on one’s character” (p. 265). That’sa pretty strong statement. What is hisbasis for it? The problem, as he seesit, is that the Christian’s concern for his personal salvation in the afterlifetends to make him insufficiently attentive to his social obligations in thisworld. He spells this out in thefollowing curious passage:

Christianity is a solitary religion:each is saved or damned individually, and we naturally focus on our ownsalvation to the point where nothing else might seem to matter. Whereas actually, while it is impossible notto be concerned with ourselves, at least to some degree – and we should – ourown individual soul and its salvation are hardly important for the largerpicture of civilized life, and often we have to recognize this. Thus, how important is it that I be savedcompared to risking my life to assassinate Hitler, had I the chance? It’s not important at all. (p. 265)

Note firstthat the example is very odd. We canagree that it would be extremely important for someone to stop Hitler,including by way of an assassination that might risk one’s own life, if one wasin a position to do so. But thoughperhaps a few Christians would disagree with that (pacifists, say), why onearth would Rawls think Christians in general would? Yet maybe he doesn’t mean to imply that theywould, but instead intends only to say that while Christians would agree thatstopping Hitler is important, they would regard salvation as even moreimportant.

The examplestill seems odd, but put that aside. Forit is also very odd for Rawls to claim that salvation is “hardly important for the larger picture of civilized life,” andindeed “not important at all.” For salvation concerns the eternal happinessof one’s immortal soul, and the avoidance of eternal damnation. Not even the greatest blessings of this lifecan compare to salvation, and not even the greatest evils of this life cancompare to damnation. Hence, it is obvious that nothing could be moreimportant than these things. Why onearth, then, would Rawls suggest that in fact they are “hardly important” andeven “not important at all”?

No doubtRawls believed that there is no such thing as salvation or damnation in thehereafter. But that is beside thepoint. For the fact remains that if salvation and damnation are real, then they would indeed be far moreimportant than anything that occurs in this life. What Rawls should say, then, is not thatsalvation is unimportant, but that itis unreal, if that’s indeed what hethinks. It would be silly, and indeedmad, to say that salvation and damnation might indeed be real but still somehow hardly important oraltogether unimportant.

Anyway,these remarks evince a very this-worldly moral and spiritual orientation, and arejection of Christianity’s traditional emphasis on the hereafter. And here too Rawls has much in common withthe early modern liberals, who also wanted to reorient the West away from theotherworldly concerns of medieval Christianity and focus it on the here andnow.