Edward Feser's Blog, page 13

December 12, 2023

On Vallier, Vermeule, and straw men (Updated)

Over at hisSubstack, KevinVallier responds to my recent reviewat The Josias of his book

Allthe Kingdoms of the World

. Vallier claims that I “mislead the reader” vis-à-vis hischaracterization of the views of Adrian Vermeule. In particular, says Vallier, “Feser… makesseveral claims that make it sound as if I think Vermeule endorses violence andauthoritarianism. Feser does note at onepoint that I say Vermeule does not want coercion. But that leaves the impression that I only saythis in passing.” He then cites fiveremarks from his book that he says show that he clearly acknowledges thatVermeule does not endorse violence.

Over at hisSubstack, KevinVallier responds to my recent reviewat The Josias of his book

Allthe Kingdoms of the World

. Vallier claims that I “mislead the reader” vis-à-vis hischaracterization of the views of Adrian Vermeule. In particular, says Vallier, “Feser… makesseveral claims that make it sound as if I think Vermeule endorses violence andauthoritarianism. Feser does note at onepoint that I say Vermeule does not want coercion. But that leaves the impression that I only saythis in passing.” He then cites fiveremarks from his book that he says show that he clearly acknowledges thatVermeule does not endorse violence.So, have Igiven a misleading impression of Vallier’s treatment of Vermeule? Not in the least. Note, first, that I explicitly said in myreview that Vallier acknowledges that Vermeule does not advocate violence. I wrote:

Vallier tells us [that]… whether they like it or not, in orderto bring their desired regime about, integralists “must use violence in waysthat the Catholic Church rejects” (p. 137)…

Vallier admits that infact “Vermeule wants to avoid coercion” and “says little about how hard integralists should fight for the ideal”(pp. 134-35).

Most of what Vallier describes is not anything Vermeule himself actually says, but onlywhat Vallier claims would have to bedone in order to realize Vermeule’s vision .

End quote. The problem, as I show, is that Vallier also says things that give theimpression that Vermeule advocates a radically revolutionary political programthat manifestly could not be realized without violence. And material of this latter sort greatlyoutweighs the qualifying statements Vallier makes here and there, and which hecites in his response to me.

Hence, as Inoted in my review, we have page after harrowing page in Vallier’s bookdescribing how the political program he attributes to Vermeule “probablyrequires abolishing democracy” (p. 136) and would entail “mass surveillance… [to]suppress dissent” (p. 150), “Chinese-level tactics” (p. 148), “modern heresytrials” (p. 149), “pressure to segregate religiously diverse populations” (p.154), “ultra-loyal troops [to] subdue career military officials. (Hitler’s SSsprings to mind)” and “youth programs to increase loyalty to their leader.(Hitler Youth springs to mind)” (p. 146), “human rights violations” and “secretpolice” (pp. 151-52), and “leadership purges, replete with execution, torture,and show trials. A one-party state” (p. 147). Vallier warns that to uphold the regime Vermeule would set up,“Protestants could face heresy charges” (p. 153); that “according tointegralism, Black Protestant churches have no right to exist” and “the statemust decide whether to declare Black Protestant churches criminalorganizations” (ibid.); and that “we should not assume that an integralistregime will treat Jews well” (ibid.).

And soon. Vallier concludes that “Vermeule’sintegration from within requires massive violence” (p. 239). Indeed, the political program he attributesto Vermeule is so extreme andunhinged that it is hard to see how anyone could fail to perceive that it wouldrequire massive violence. And again,though Vallier makes a few disclaimers here and there, they are nowhere near asnumerous or prominent as the detailed descriptions he gives of the coerciveregime he says Vermeule’s views would entail. When an author briefly notes here and there that Vermeule doesn’t advocate violence, but also goes on at greatlength about how Vermeule’s extremepolitical program would manifestly require massive violence, it is hardlyunfair to judge that he has given his readers a misleading impression ofVermeule’s views.

Then thereis the fact that Vallier’s qualifying statements are hardly full-throated. For example, as Vallier notes in his reply tome, he concedes that “Vermeule would not suppress liberalism with violence” (p.134). But here is the longer passage inVallier’s book from which that line is taken:

Vermeule wants to protect the Churchfrom malignant states. His method: trainstrong Christian leaders who will take power and defend the church. When Ihave spoken with Vermeule’s defenders, often young people, they characterizehis strategy as concerned chiefly with defense rather than offense. I do not think Vermeule’stheory of liberalism allows for any such distinction. Vermeule would not suppressliberalism with violence. Liberalismwill destroy itself. But liberals andthe liberal state can still do significant damage in the meanwhile. Further, once liberalism dies, it couldrevive.

As Vermeule so evocativelyclaims, we must “sear the liberal faith with hot irons.” It must not rise again. Only a strong state combined with a strongchurch can complete this urgent task. Vermeulean protectors must become conquerors. They must then rule with an iron rod. And so, however much Vermeulewants to avoid coercion, he is stuck with it. Integralists must exercise hard power. (p. 134)

Endquote. The impression given here is thatwhile Vermeule does not endorse violence and even eschews it, he does endorse a radical political programthat would clearly requireviolence. But as I showed in my review,the problem is not just that Vermeule does not endorse violence itself. The problem is that Vermeule does not in the first place actually endorse the extremepolitical program Vallier attributes to him.

Hence, in “Integrationfrom Within” (from which the “hot irons” remark is quoted), Vermeuleis not talking about Catholicintegralism, but “nonliberal” politics more generally. Indeed, he explicitly says that “there can be no return to the integratedregime of the thirteenth century, whatever its attractions.” Nor does he advocate any positive concretepolitical program of any other kind for replacing liberalism, and indeedexplicitly says that the “postliberal future [is] of uncertain shape.” Vermeule says that “for the foreseeablefuture, the problem will be to mitigate the spasmodic, but compulsive andrepetitive, aggression of the decaying liberal state” rather than promote analternative. Indeed, he says thatnonliberals who follow his advice will:

mainly attempt to ensure the survivalof their faith communities in an interim age of exile and dispossession. They donot evangelize or preach with a view to bringing about the birth of an entirelynew regime, from within the old. They mitigate the long defeat for thosewho become targets of the regime in liberalism’s twilight era, and this will surely have to be the main aimfor some time to come.

Endquote. Similarly, in “AChristian Strategy,” far from endorsing the “party capture” approach thatVallier attributes to him, Vermeule says that “the Church… must stand detached from all subsidiary political commitments, willingto enter into flexible alliances of convenience with any of the parties.” Rather than calling for going on offense witha revolutionary political program, he says that “the main proximate short-rungoal must be largely one of survival.” Rather than pushing some doctrinaire integralist vision, he emphasizesflexibility: “Christians will always have many different options for politicalengagement. In some or othercircumstances, one or another of them will prove best in the light ofprudential judgment; none has any logical or theological priority.”

In short, Vallieris saying, “I didn’t accuse Vermeule of advocating B! I accused him ofadvocating A, which will inevitably lead to B!” And the problem is that Vermeule not onlydoes not advocate B, he doesn’t advocate A either.

Or consider Vallier’sremark that “Vermeule has publicly declaimed all such [violent] tactics.” Here is the passage in Valler’s book in whichthat remark appears:

Vermeule has publicly declaimed allsuch tactics. Indeed, even in“Integration from Within” he indicates hesitancy about coercion, though what hesays is curious: “It would be wrong to conclude that integration from within isa matter of coercion, as opposed to persuasion and conversion, for thedistinction is so fragile as to be nearly useless.” On the one hand, integration from within isnot “a matter of coercion.” But thedistinction between coercion and noncoercion is “nearly useless” – which leavesone to wonder which tactics Vermeule has in mind. (p. 147)

End quote. One problem here is that Vallier is misusingthe word “declaim,” which literally means “to speak in an eloquent orimpassioned way.” So, the literalmeaning of what Vallier says in the first line here is “Vermeule has publicly spokenin an eloquent way of all such [violent] tactics”! Obviously, that is not what Vallier means,which is why I didn’t bother quoting this particular line.

The moreimportant point here, though, is this. Onthe one hand, Vallier here acknowledges that Vermeule shows “hesitancy aboutcoercion.” But on the other hand,Vallier says that it is “curious” that Vermeule says that the distinction betweencoercion and persuasion is “nearly useless,” so that one “wonder[s] whichtactics Vermeule has in mind.” Since thelarger context is a discussion of the violent means Vermeule’s program wouldallegedly require, some readers might get the impression that Vermeule mightnot be entirely committed to eschewing violence after all.

But here isthe longer passage from Vermeule’s article “Integration from Within” where hemakes the remark in question:

It would be wrong to conclude thatintegration from within is a matter of coercion, as opposed to persuasion andconversion, for the distinction is so fragile as to be nearly useless. As J. F. Stephen noted, there is a type ofintellectual and rhetorical “warfare” in which “the weaker opinion – the lessrobust and deeply seated feeling – is rooted out to the last fiber, the placewhere it grew being seared as with a hot iron.” In a more recent register, we have learnedfrom behavioral economics that agents with administrative control over defaultrules may nudge whole populations in desirable directions, in an exercise of“soft paternalism.” It is a uselessexercise to debate whether or not this shaping from above is best understood ascoercive, or rather as an appeal to the “true” underlying preferences of thegoverned.

Endquote. Seen in this context, there isnothing at all “curious” about Vermeule’s remark, or remotely suggestive ofviolence. On the contrary, as I noted inmy review of Vallier’s book, it is clear from this passage that when Vermeule speaksof cases where the distinction between coercion and persuasion is unclear, whathe actually had in mind were soft incentives of the kind liberals like RichardThaler and Cass Sunstein describe in their book Nudge:Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

Here is anotherexample where Vallier’s reading of Vermeule is careless to such an extent thathe ends up attributing to Vermeule the opposite of what he actually said. As I noted my review, Vallier comparesVermeule’s program to that of a Marxist revolutionary party. Hence, in his book, Vallier writes: “Vermeuleanalogizes his view [of liberalism] with Karl Marx’s claims about capitalism: ‘Liberalismis inherently unstable and is structurally disposed to generate the very forcesthat destroy it’” (p. 127). The remarkfrom Vermeule is quoted from “A Christian Strategy.” But here is the larger passage in thatarticle in which it appears:

There are two ways of understanding[the liberal] dynamic. One is that inthe long run, liberalism undermines itself by transforming tolerance intoincreasingly radical intolerance of the “intolerant” – meaning those who holdilliberal views. On this view, militantprogressivism is distinct from liberalism, indeed a betrayal of it. Such anaccount would make liberalism analogous to Marx’s claim about capitalism:Liberalism is inherently unstable and is structurally disposed to generate thevery forces that destroy it.

A different view, andmy own, is that liberal intolerance represents not the self-undermining ofliberalism, but a fulfillment of its essential nature. When a chrysalis shelters aninsect that later bursts forth from it and leaves it shattered, the chrysalishas in fact fulfilled its true and predetermined end. Liberalism of the purportedly tolerant sort isto militant progressivism as the chrysalis is to the hideous insect.

End quote. As the reader can clearly see, in the lineVallier quotes, Vermeule is notstating his own view, but on the contrary, a view he explicitly says is “different [from his] own.”

More couldbe said, but that suffices to make the point. Vallier is for the most part admirably fair-minded, and I don’t thinkfor a moment that he intentionallymisrepresents Vermeule. But that he doesin fact give a misleading characterization of Vermeule’s views, however inadvertently,there can be no doubt. (Vallieraddresses some other issues too, and says that he will address yet others in a futurepost. I may return to those in a futurereply.)

UPDATE 12/15:Vallier responds overat Substack. Here’s the reply Iposted atTwitter:

Sorry, but thecase remains unmade. When @Vermeullarmine offers us specific models for a Christianpolitics to look to, he gives biblical examples like Joseph in Egypt, Esther andMordecai, and St. Paul. Are these models of the integralist “state capture”envisaged by @kvallier? No, they involve using state power defensively, toprotect a faithful minority (in the first two cases) and seeding the ground fora centuries-long change in the culture (in the case of Paul). Any “statecapture” that such models could lead to are so very far down the line (perhaps centuries) that the relevant concretecultural circumstances are impossible to predict, giving Vallier’s imagined Catholicintegralist state capture scenarios no purchase. And as I keep saying, Vermeule himself does not, in any event,actually propose any such scenario. In order to attribute it to him, Vallier’slatest response has to rely in part on what otherpeople have said, and on extrapolationfrom a tweet from Vermeule (despite conceding, at p. 123 of his book, thattweets and other off-the-cuff social media ephemera are not a good basis onwhich reconstruct someone’s considered views).

On Vallier, Vermeule, and straw men

Over at hisSubstack, KevinVallier responds to my recent reviewat The Josias of his book

Allthe Kingdoms of the World

. Vallier claims that I “mislead the reader” vis-à-vis hischaracterization of the views of Adrian Vermeule. In particular, says Vallier, “Feser… makesseveral claims that make it sound as if I think Vermeule endorses violence andauthoritarianism. Feser does note at onepoint that I say Vermeule does not want coercion. But that leaves the impression that I only saythis in passing.” He then cites fiveremarks from his book that he says show that he clearly acknowledges thatVermeule does not endorse violence.

Over at hisSubstack, KevinVallier responds to my recent reviewat The Josias of his book

Allthe Kingdoms of the World

. Vallier claims that I “mislead the reader” vis-à-vis hischaracterization of the views of Adrian Vermeule. In particular, says Vallier, “Feser… makesseveral claims that make it sound as if I think Vermeule endorses violence andauthoritarianism. Feser does note at onepoint that I say Vermeule does not want coercion. But that leaves the impression that I only saythis in passing.” He then cites fiveremarks from his book that he says show that he clearly acknowledges thatVermeule does not endorse violence.So, have Igiven a misleading impression of Vallier’s treatment of Vermeule? Not in the least. Note, first, that I explicitly said in myreview that Vallier acknowledges that Vermeule does not advocate violence. I wrote:

Vallier tells us [that]… whether they like it or not, in orderto bring their desired regime about, integralists “must use violence in waysthat the Catholic Church rejects” (p. 137)…

Vallier admits that infact “Vermeule wants to avoid coercion” and “says little about how hard integralists should fight for the ideal”(pp. 134-35).

Most of what Vallier describes is not anything Vermeule himself actually says, but onlywhat Vallier claims would have to bedone in order to realize Vermeule’s vision .

End quote. The problem, as I show, is that Vallier also says things that give theimpression that Vermeule advocates a radically revolutionary political programthat manifestly could not be realized without violence. And material of this latter sort greatlyoutweighs the qualifying statements Vallier makes here and there, and which hecites in his response to me.

Hence, as Inoted in my review, we have page after harrowing page in Vallier’s bookdescribing how the political program he attributes to Vermeule “probablyrequires abolishing democracy” (p. 136) and would entail “mass surveillance… [to]suppress dissent” (p. 150), “Chinese-level tactics” (p. 148), “modern heresytrials” (p. 149), “pressure to segregate religiously diverse populations” (p.154), “ultra-loyal troops [to] subdue career military officials. (Hitler’s SSsprings to mind)” and “youth programs to increase loyalty to their leader.(Hitler Youth springs to mind)” (p. 146), “human rights violations” and “secretpolice” (pp. 151-52), and “leadership purges, replete with execution, torture,and show trials. A one-party state” (p. 147). Vallier warns that to uphold the regime Vermeule would set up,“Protestants could face heresy charges” (p. 153); that “according tointegralism, Black Protestant churches have no right to exist” and “the statemust decide whether to declare Black Protestant churches criminalorganizations” (ibid.); and that “we should not assume that an integralistregime will treat Jews well” (ibid.).

And soon. Vallier concludes that “Vermeule’sintegration from within requires massive violence” (p. 239). Indeed, the political program he attributesto Vermeule is so extreme andunhinged that it is hard to see how anyone could fail to perceive that it wouldrequire massive violence. And again,though Vallier makes a few disclaimers here and there, they are nowhere near asnumerous or prominent as the detailed descriptions he gives of the coerciveregime he says Vermeule’s views would entail. When an author briefly notes here and there that Vermeule doesn’t advocate violence, but also goes on at greatlength about how Vermeule’s extremepolitical program would manifestly require massive violence, it is hardlyunfair to judge that he has given his readers a misleading impression ofVermeule’s views.

Then thereis the fact that Vallier’s qualifying statements are hardly full-throated. For example, as Vallier notes in his reply tome, he concedes that “Vermeule would not suppress liberalism with violence” (p.134). But here is the longer passage inVallier’s book from which that line is taken:

Vermeule wants to protect the Churchfrom malignant states. His method: trainstrong Christian leaders who will take power and defend the church. When Ihave spoken with Vermeule’s defenders, often young people, they characterizehis strategy as concerned chiefly with defense rather than offense. I do not think Vermeule’stheory of liberalism allows for any such distinction. Vermeule would not suppressliberalism with violence. Liberalismwill destroy itself. But liberals andthe liberal state can still do significant damage in the meanwhile. Further, once liberalism dies, it couldrevive.

As Vermeule so evocativelyclaims, we must “sear the liberal faith with hot irons.” It must not rise again. Only a strong state combined with a strongchurch can complete this urgent task. Vermeulean protectors must become conquerors. They must then rule with an iron rod. And so, however much Vermeulewants to avoid coercion, he is stuck with it. Integralists must exercise hard power. (p. 134)

Endquote. The impression given here is thatwhile Vermeule does not endorse violence and even eschews it, he does endorse a radical political programthat would clearly requireviolence. But as I showed in my review,the problem is not just that Vermeule does not endorse violence itself. The problem is that Vermeule does not in the first place actually endorse the extremepolitical program Vallier attributes to him.

Hence, in “Integrationfrom Within” (from which the “hot irons” remark is quoted), Vermeuleis not talking about Catholicintegralism, but “nonliberal” politics more generally. Indeed, he explicitly says that “there can be no return to the integratedregime of the thirteenth century, whatever its attractions.” Nor does he advocate any positive concretepolitical program of any other kind for replacing liberalism, and indeedexplicitly says that the “postliberal future [is] of uncertain shape.” Vermeule says that “for the foreseeablefuture, the problem will be to mitigate the spasmodic, but compulsive andrepetitive, aggression of the decaying liberal state” rather than promote analternative. Indeed, he says thatnonliberals who follow his advice will:

mainly attempt to ensure the survivalof their faith communities in an interim age of exile and dispossession. They donot evangelize or preach with a view to bringing about the birth of an entirelynew regime, from within the old. They mitigate the long defeat for thosewho become targets of the regime in liberalism’s twilight era, and this will surely have to be the main aimfor some time to come.

Endquote. Similarly, in “AChristian Strategy,” far from endorsing the “party capture” approach thatVallier attributes to him, Vermeule says that “the Church… must stand detached from all subsidiary political commitments, willingto enter into flexible alliances of convenience with any of the parties.” Rather than calling for going on offense witha revolutionary political program, he says that “the main proximate short-rungoal must be largely one of survival.” Rather than pushing some doctrinaire integralist vision, he emphasizesflexibility: “Christians will always have many different options for politicalengagement. In some or othercircumstances, one or another of them will prove best in the light ofprudential judgment; none has any logical or theological priority.”

In short, Vallieris saying, “I didn’t accuse Vermeule of advocating B! I accused him ofadvocating A, which will inevitably lead to B!” And the problem is that Vermeule not onlydoes not advocate B, he doesn’t advocate A either.

Or consider Vallier’sremark that “Vermeule has publicly declaimed all such [violent] tactics.” Here is the passage in Valler’s book in whichthat remark appears:

Vermeule has publicly declaimed allsuch tactics. Indeed, even in“Integration from Within” he indicates hesitancy about coercion, though what hesays is curious: “It would be wrong to conclude that integration from within isa matter of coercion, as opposed to persuasion and conversion, for thedistinction is so fragile as to be nearly useless.” On the one hand, integration from within isnot “a matter of coercion.” But thedistinction between coercion and noncoercion is “nearly useless” – which leavesone to wonder which tactics Vermeule has in mind. (p. 147)

End quote. One problem here is that Vallier is misusingthe word “declaim,” which literally means “to speak in an eloquent orimpassioned way.” So, the literalmeaning of what Vallier says in the first line here is “Vermeule has publicly spokenin an eloquent way of all such [violent] tactics”! Obviously, that is not what Vallier means,which is why I didn’t bother quoting this particular line.

The moreimportant point here, though, is this. Onthe one hand, Vallier here acknowledges that Vermeule shows “hesitancy aboutcoercion.” But on the other hand,Vallier says that it is “curious” that Vermeule says that the distinction betweencoercion and persuasion is “nearly useless,” so that one “wonder[s] whichtactics Vermeule has in mind.” Since thelarger context is a discussion of the violent means Vermeule’s program wouldallegedly require, some readers might get the impression that Vermeule mightnot be entirely committed to eschewing violence after all.

But here isthe longer passage from Vermeule’s article “Integration from Within” where hemakes the remark in question:

It would be wrong to conclude thatintegration from within is a matter of coercion, as opposed to persuasion andconversion, for the distinction is so fragile as to be nearly useless. As J. F. Stephen noted, there is a type ofintellectual and rhetorical “warfare” in which “the weaker opinion – the lessrobust and deeply seated feeling – is rooted out to the last fiber, the placewhere it grew being seared as with a hot iron.” In a more recent register, we have learnedfrom behavioral economics that agents with administrative control over defaultrules may nudge whole populations in desirable directions, in an exercise of“soft paternalism.” It is a uselessexercise to debate whether or not this shaping from above is best understood ascoercive, or rather as an appeal to the “true” underlying preferences of thegoverned.

Endquote. Seen in this context, there isnothing at all “curious” about Vermeule’s remark, or remotely suggestive ofviolence. On the contrary, as I noted inmy review of Vallier’s book, it is clear from this passage that when Vermeule speaksof cases where the distinction between coercion and persuasion is unclear, whathe actually had in mind were soft incentives of the kind liberals like RichardThaler and Cass Sunstein describe in their book Nudge:Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

Here is anotherexample where Vallier’s reading of Vermeule is careless to such an extent thathe ends up attributing to Vermeule the opposite of what he actually said. As I noted my review, Vallier comparesVermeule’s program to that of a Marxist revolutionary party. Hence, in his book, Vallier writes: “Vermeuleanalogizes his view [of liberalism] with Karl Marx’s claims about capitalism: ‘Liberalismis inherently unstable and is structurally disposed to generate the very forcesthat destroy it’” (p. 127). The remarkfrom Vermeule is quoted from “A Christian Strategy.” But here is the larger passage in thatarticle in which it appears:

There are two ways of understanding[the liberal] dynamic. One is that inthe long run, liberalism undermines itself by transforming tolerance intoincreasingly radical intolerance of the “intolerant” – meaning those who holdilliberal views. On this view, militantprogressivism is distinct from liberalism, indeed a betrayal of it. Such anaccount would make liberalism analogous to Marx’s claim about capitalism:Liberalism is inherently unstable and is structurally disposed to generate thevery forces that destroy it.

A different view, andmy own, is that liberal intolerance represents not the self-undermining ofliberalism, but a fulfillment of its essential nature. When a chrysalis shelters aninsect that later bursts forth from it and leaves it shattered, the chrysalishas in fact fulfilled its true and predetermined end. Liberalism of the purportedly tolerant sort isto militant progressivism as the chrysalis is to the hideous insect.

End quote. As the reader can clearly see, in the lineVallier quotes, Vermeule is notstating his own view, but on the contrary, a view he explicitly says is “different [from his] own.”

More couldbe said, but that suffices to make the point. Vallier is for the most part admirably fair-minded, and I don’t thinkfor a moment that he intentionallymisrepresents Vermeule. But that he doesin fact give a misleading characterization of Vermeule’s views, however inadvertently,there can be no doubt. (Vallieraddresses some other issues too, and says that he will address yet others in a futurepost. I may return to those in a futurereply.)

December 8, 2023

Contra Vallier on integralism

Over at The Josias, I critique Kevin Vallier’snew book

Allthe Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism

.

Over at The Josias, I critique Kevin Vallier’snew book

Allthe Kingdoms of the World: On Radical Religious Alternatives to Liberalism

.

November 26, 2023

Ryle on microphysics and the everyday world

Science,we’re often told, gives us a description of the world radically at odds withcommon sense. Physicist Arthur Eddington’sfamous “two tables” example illustrates the theme. There is, on the one hand, the table familiarfrom everyday experience – the extended, colored, solid, stable thing you mightbe sitting at as you read this. Thenthere’s the scientific table – a vast aggregate of colorless particles infields of force, mostly empty space rather a single continuous object, andrevealed by theory rather than sensory perception. What is the relationship between them? Should we say, as is often done, that thefirst table is an illusion and only the second real?

Science,we’re often told, gives us a description of the world radically at odds withcommon sense. Physicist Arthur Eddington’sfamous “two tables” example illustrates the theme. There is, on the one hand, the table familiarfrom everyday experience – the extended, colored, solid, stable thing you mightbe sitting at as you read this. Thenthere’s the scientific table – a vast aggregate of colorless particles infields of force, mostly empty space rather a single continuous object, andrevealed by theory rather than sensory perception. What is the relationship between them? Should we say, as is often done, that thefirst table is an illusion and only the second real?As philosopherGilbert Ryle showed in chapter 5 of his classic book Dilemmas,the real illusion is not the table of common sense, but rather the notion thatscience gives us any reason to doubt it. In fact, science is not even addressing the sorts of question commonsense might ask about the table, much less giving an answer that conflicts withthe one common sense would give. And itis only conceptual confusion that makes some suppose otherwise.

Ryle’s reminders

Ryleidentifies two main sources of this confusion concerning what science tells usabout the world. The first has to dowith the word “science” and the second with the word “world.” For one thing, there is not even a primafacie conflict between our common sense conception of the world and the vastbulk of what falls under the label “science.” No one thinks philology casts the slightest doubt on the reality ofwords, or that botany, geology, and meteorology cast any doubt on the realityof plants, earth, or weather. Thefindings of such areas of research are not taken to undermine our confidence inthe reality of everyday objects. Nor aretelescopes and microscopes taken to give any reason for doubting it, despiterevealing objects vastly larger or vastly smaller than the ones we encounter ineveryday life. Nor is what physics tellsus about middle-sized objects (pendulums, water pumps, etc.) regarded aschallenging our belief in tables and the like.

In fact,Ryle suggests, it is only two special areas of scientific study that peoplesuppose somehow casts doubt on such belief: the microstructure of materialobjects, and the physiology of perception. But even here, it is not, strictly speaking, the findings of modernscience that are the source of the problem. Similar claims about the unreality of ordinary objects were mademillennia ago on the basis of the speculations of the ancient atomists.

Why don’tthe scientific findings, any more than the speculations, cast doubt on theworld of common sense? This brings us tothe word “world.” When we hear tell of the world as described by microphysics,we are, says Ryle, too quick to suppose that “world” should in this context beunderstood the way it is understood by theologians when they talk about theworld’s creation, or that it should interpreted as a synonym for “cosmos.” But we should think of it instead on themodel of phrases like “the world of poultry” as a farmer or butcher might meanit, or “the entertainment world” as a newspaper reporting on what is going onin the field of entertainment would use it. “World” in such contexts means something like “sphere of interest” or“the collection of matters pertaining to a certain subject” (such as poultry orentertainment).

Now, no onethinks there is some conflict between “the world of poultry” or “theentertainment world” on the one hand, and the world of everyday physicalobjects on the other. But neither isthere any conflict between the latter world and the world of facts which arethe sphere of interest of the scientist who studies the microstructure ofmatter or the physiology of perception. As with poultry or entertainment, the “world” of the latter is reallyjust a relatively small subset of all the facts that make up reality. It is not a comprehensive description ofreality that competes with the description taken for granted by common sense.

Ryle offersa couple of analogies to illustrate the point. When economics characterizes human behavior by way of considerations ofprofit and loss, supply and demand, and so on, it is not putting forward anexhaustive characterization of the nature of human beings or of any particularhuman being. Nor is it mischaracterizingthem. It is simply noting what peoplewill tend to do if they are in circumstances of a certain specific sort, andare attentive to considerations of a certain specific sort. That’s all. Similarly, when microphysics characterizes matter in the way it does, itis not to be understood as offering an exhaustive characterization of tables andother everyday physical objects, but simply calling attention to certain featuresthat are manifest under certain circumstances. That’s all.

Ryle speaksas if the average reader at the time he was writing (the early 1950s) would readilygrant that it would be a crude mistake to think that the economist’sdescription captured the entirety of human nature. It may be doubted whether all readers todaywould be immune to such economic reductionism, but in any case, Ryle alsooffers another analogy. He asks us toimagine an accountant who has put together an exhaustive description of thefinancial operations of a certain college – tuition, salaries, rents, costs forutilities and groundskeeping, expenditures on library books, food services,sports, special events, and so on. Suppose the description covers all the activities and assets of theinstitution and is extremely precise and useful.

Theobjectivity, precision, comprehensiveness, and utility of this descriptionwould hardly justify the accountant in claiming that he has captured all there is to the college. Even though there is no part of the collegethat is not referred to in his ledger, the ledger obviously doesn’t capture allthere is to those parts or to the whole they make up. For example, even if the price of everylibrary book can be found there, the sorts of things that, say, a book reviewerwould want to know about a book will not be captured. But neither would it be correct to say thatthe description of the college that the accountant gives is in competition withthe description that might be given by, say, a student. Nor would it be correct to say that theaccountant’s description is mistaken. Itis correct as far as it goes, but itis simply not meant in the first place to capture everything.

Obviously, itwould be silly so speak of there being two colleges, the way that Eddingtonspeaks of there being two tables. Thereis just the one college, and certain features of it are focused on by thestudent for his purposes, whereas others are focused on by the accountant forhis own, different purposes. But thesame thing is true of tables and other physical objects as common senseunderstands them and as the physicist approaches them. There is just the one table, and the ordinaryperson in everyday life focuses on certain aspects of it, whereas physics focuseson different aspects. That’s all. Physics, rightly understood, no more competeswith or refutes the ordinary person’s understanding of the table than theaccountant competes with or refutes the student’s understanding of the college.

Ryle notesthat it is tempting to say that common sense and microphysics give differentbut complementary “descriptions” or “pictures” of the same reality, but heargues that even this is misleading, insofar as it implicitly attributes a fargreater commonality of purpose that actually exists between the two. For there is no reason to think ofmicrophysics as attempting in the first place to “picture” the reality of atable or any other ordinary physical object (as opposed to explaining certainfeatures of it, or predicting its behavior under such-and-such circumstances,or figuring out how to manipulate it in certain ways – none of which entails orrequires a “picture” of its full reality).

Ryle alsonotes that nothing in what he says implies or is intended to imply any contributionto, or criticism of, scientific practice or scientific results. It is merely a point about the fallaciousnessof certain kinds of claims made about the everyday world on the basis ofscience.

Hossenfelder and Goff

Regrettably,even seventy years after Ryle wrote, too many philosophers and scientists alikestill need a reminder of these observations, simple and obvious though theyought to be. Physicist Brian Greeneprovided a good example nottoo long ago. Another case in pointis a recentTwitter exchange between philosopher Philip Goff and physicistSabine Hossenfelder, and the debate on Twitter that it engendered. To be sure, neither Hossenfelder nor Goffwould say that physics provides an exhaustive description of physicalreality. In that way their views alignwith Ryle’s main point (albeit neither brings up Ryle). However, they miss some of its otherimplications.

For example,Hossenfelder not only takes an instrumentalist view of physics, but seems tothink it obvious that physics just is,of its nature, instrumentalist – that when it makes reference to electrons, forexample, there is no implication whatsoever that electrons actually exist, asopposed to being merely a useful fiction for organizing observations and makingpredictions. But while instrumentalismis certainly defensible, it seems to me a mistake to think it the obviously correct interpretation ofphysics. This is like saying that theaccountant’s description of the college, in Ryle’s example, is obviously nothing more than a usefulfiction, and that its utility gives us no reason at all to believe that itcaptures anything really there in the college. In fact, of course, the accountant’s description does capture realfeatures of the college, even if only very abstract economic relations and farfrom all, or even the most important, features of the college. Similarly, the utility of physics gives usreason to think it does capture real features of the world, even if they are highlyabstract structural features and very far from an exhaustive description ofnature. I defend this epistemic structural realistinterpretation of physics in Aristotle’sRevenge.

Goff, meanwhile,himself accepts this interpretation of physics. However, he falls into another error. Physics captures only very abstract structural features of physicalreality. But what about the otherfeatures? What fleshes out thisabstract structure? Goff is among thegrowing number of writers who argue for panpsychismby proposing that qualia, the characteristic features of conscious experience(the way red looks, the way coffee smells, and the like) provide a model forunderstanding the intrinsic nature of all physical reality. He presents this as a bold solution to whatwould otherwise be a great mystery.

To see whatis wrong with this, imagine someone who noted that Ryle’s accountant providesonly a very abstract description of the college’s economic structure, and thenargued: “Something must flesh out that abstract structure. Whatever could it be? What a mystery! I postulate that it is qualia that flesh it out, and thus that, strange as it may seem,the college is – from the lecture halls to the library to the cafeteria anddown to every floorboard of the gym – a panpsychist entity pulsating with consciousness!”

The main problemwith this argument is not that it leads to a ludicrous conclusion, though itcertainly does. The problem is that itis a “solution” to something that isn’t a mystery in the first place. Certainly, the abstractness of the accountant’sdescription of the college doesn’t pose any mystery whatsoever. We already know what the intrinsic propertiesof the college are – they are simply those that every student, professor, administratorand janitor already knows about, just by walking around and looking at it fromday to day. The accountant has simplyignored all this detail that we already know about, and focused instead oncertain abstract economic features.

Similarly,we already know what the intrinsic features are of tables and other ordinary physicalobjects. They are precisely those wecome across in dealing with these objects every day. Physics simply ignores these features andfocuses on those of which it can give a precise mathematical treatment. There is no mystery that needs solving interms of some bizarre metaphysics like panpsychism, but merely a reminder ofwhat we already know from common sense. Ryle (like Aristotle, Aquinas, Wittgenstein, and other critics ofrevisionist metaphysics) offers precisely such a reminder. (I have criticized Goff’s views along theselines but at greater length before, hereand here.)

Somescientists who commented on the exchange between Hossenfelder and Goff onTwitter opined that it illustrates why many scientists don’t find such discussionsfruitful. According to one of them, thereason they are unfruitful is that they don’t help us do physics better. But why on earth should anyone suppose thatthe only reason why a discussion between physicists and philosophers would beworthwhile would be if it helps the former do physics better? Putting the implicit narcissism to one side,there is another problem. As Ryle says,the point of his own remarks is not to either criticize or add to science’smethodology or results, but rather to reveal the fallaciousness of certaininferences drawn from its methodologyor results. A scientist who thinks sucha message not worthwhile is precisely the sort of person most in need ofhearing it.

Relatedposts:

Theparticle collection that fancied itself a physicist

Dupréon the ideologizing of science

Cartwrighton theory and experiment in science

November 18, 2023

What is free speech for?

In a new articleat Postliberal Order, I discussthe teleological foundations of, and limitations on, the right to free speech,as these are understood from the perspective of traditional natural law theory’sapproach to questions about natural rights.

In a new articleat Postliberal Order, I discussthe teleological foundations of, and limitations on, the right to free speech,as these are understood from the perspective of traditional natural law theory’sapproach to questions about natural rights.

November 9, 2023

All One in Christ at Public Discourse

At Public Discourse, John F. Doherty kindly reviews mybook

AllOne in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

. From the review:

At Public Discourse, John F. Doherty kindly reviews mybook

AllOne in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

. From the review:In Feser’s book, Catholics, otherChristians, and even non-Christians will find much to help them confront CRTand the perennial challenges of living in a racially diverse society…

Critical race theorists routinely useconfusing, tough-to-pin-down logical fallacies. Feser does us the service of laying thesefallacies out methodically and succinctly…

For anyone who knows nothing aboutCRT, All One inChrist is an excellent place to start. It has a decidedly negative perspective on themovement, but Feser takes pains to be fair to his opponents.

November 4, 2023

The Thomist's middle ground in natural theology

TheAristotelian-Thomistic tradition holds that knowledge must begin with sensoryexperience but that it can nevertheless go well beyond anything that experiencecould directly reveal. Its empiricism isof a moderate kind consistent with the high ambitions of traditional metaphysics. For example, beginning a posteriori with the fact that change occurs, it claims to be ableto demonstrate the existence of a divine Prime Unmoved Mover. Similarly demonstrable, it maintains, are theimmateriality and immortality of the soul.

TheAristotelian-Thomistic tradition holds that knowledge must begin with sensoryexperience but that it can nevertheless go well beyond anything that experiencecould directly reveal. Its empiricism isof a moderate kind consistent with the high ambitions of traditional metaphysics. For example, beginning a posteriori with the fact that change occurs, it claims to be ableto demonstrate the existence of a divine Prime Unmoved Mover. Similarly demonstrable, it maintains, are theimmateriality and immortality of the soul.Two crucialcomponents of this picture of human knowledge are the theses that concepts areirreducible to sensations and mental images, but can nevertheless be abstractedfrom imagery by the intellect. As I havediscussed before,a key difference between the Aristotelian-Thomistic position on the one handand early modern forms of rationalism and empiricism on the other is that eachof the latter kept one of these Aristotelian-Thomistic theses while rejectingthe other. Rationalism maintained thethesis that concepts are irreducible to sensations and mental images, butconcluded that many or all concepts therefore could not in any way be derivedfrom them. Hence, rationalistsconcluded, many or all concepts must be innate. Modern empiricism held on to the thesis that concepts derive from mentalimagery, but concluded that they must not really be distinct from them. Hence the modern empiricist tendency toward “imagism,”the view that a concept just is an image (or an image together with a generalterm).

Thesefateful moves are key to understanding the later trajectories of therationalist and empiricist traditions. Thenotion of innate ideas gave rationalism confidence that it had the conceptual andepistemic wherewithal to ground an ambitious metaphysics. But rationalist metaphysical systems can beso bizarre and revisionary that they are open to the objection that their lackof an empirical foundation leads them to float free of objective reality. Modern empiricism, by contrast, has usuallybeen much more metaphysically modest. But it has also had a tendency to be toomodest, to the point of collapsing into skepticism even about the world ofcommon sense and ordinary experience. Here the critic can charge that collapsing concepts into imagery hasprevented modern empiricism from being able to account for any knowledge beyondthe here and now.

Now, bothapproaches can be and have been modified by various thinkers in ways that seekto avoid problems like those mentioned – though from the Thomistic point ofview, only a return to the broadly Aristotelian conception of knowledge fromwhich they each in their own ways departed can afford a sure remedy.

But general epistemologyis not my concern here. What I want todo instead is note two general approaches to natural theology that mightloosely be labeled “rationalist” and “empiricist,” even if their practitionersdon’t necessarily all self-identify as such. They are approaches that are, from the Thomist point of view, deficientin something analogous to the ways in which rationalist and modern empiricistepistemology and metaphysics in general are deficient. And like those views, they represent oppositevicious extremes between which, naturally, Thomism stands as the sober middleground.

On the onehand we have an approach that aims to establish admirably ambitious traditionalmetaphysical conclusions – such as the existence of God and the immortality ofthe soul – by way of an essentially rationalist methodology. One example would be Plantinga’sontological argument for God’s existence, and another would be Swinburne’s conceivabilityargument for dualism. Plantinga’sargument proceeds by considering what might or must be the case in variouspossible worlds, and on that basis aims to establish the existence of God inthe actual world. Swinburne’s argumentbegins with what we can conceive about the mind, and draws the conclusion thatits essence or nature must be of an immaterial kind.

From theAristotelian-Thomistic point of view, both these arguments get things preciselybackwards. We don’t start withpossibilities and then reason from them to actualities. Rather, we start with actual things,determine their essences, and then from there deduce what is or is not possiblefor them. We don’t start with what wecan conceive and then determine a thing’s essence from that. Rather, we start with a knowledge of itsessence and then determine, from that, what is actually conceivable withrespect to it, and what merely falsely seemsto be conceivable.

From theThomist point of view, while the metaphysical conclusions of such arguments are not too ambitious, the method for arriving at them is. We cannot do so entirely a priori. To be sure, oncewe do establish the existence of God (through arguments of the kind I’vedefended at length elsewhere),we discover that he is such that, were we fully to know his essence, we wouldsee that his existence follows from it of necessity, just as the ontologicalargument claims. But what we can’t do isjump directly to such an argument as a standalone proof of his existence. Similarly, when we first establish that theintellect is by nature immaterial, we will see that it is indeed conceivablefor it to exist independently of the body (topics I’ve dealt with e.g. hereand here). But in that case the appeal to conceivabilityis rendered otiose as grounds for establishing the intellect’s immateriality.

On the otherhand, we have arguments that proceed aposteriori, but are way too unambitiousin their conclusions. This wouldinclude, for example, arguments that treat God’s existence as at best the mostprobable “hypothesis”among others that might account for such-and-such empirical evidence, or evenfail to get to God, strictly speaking, as opposed to a “designer” of somepossibly finite sort. And it wouldinclude arguments for survival of death that put the primary emphasis on out-of-bodyexperiences and other phenomena that can at best render a probabilistic judgment.

Thomiststend to put little or no stock in such “god of the gaps” and “soul of the gaps”arguments. At best they are distractionsfrom the more powerful arguments of traditional metaphysics, and thus can makethe grounds for natural theology seem weaker than they really are. At worst, they can promote seriousmisunderstandings of the nature of the soul, of God, and of his relationship tothe world. (For example, they can givethe impression that it is at least possible in principle that the world mightexist without God, which entails deism at best rather than theism. And they can give the impression that the disembodiedsoul is a kind of spatially located or even ghost-like thing.)

For the Thomist,the correct middle ground position is to hold that the soul’s immateriality andimmortality, and the existence and nature of God as understood within classicaltheism, can all be demonstrated viacompelling philosophical arguments, but that the epistemology underlying thesearguments is of the Aristotelian rather than rationalist sort. (Again, I defend such arguments for theexistence and nature of God in FiveProofs of the Existence of God, and have argued for the immaterialityand immortality of the soul hereand here. Muchmore on the latter topics to come in the book on the soul that I am currentlyworking on.)

Related reading:

Therationalist/empiricist false choice

IsGod’s existence a “hypothesis”?

October 24, 2023

Cartwright on reductionism in science

In hersuperb recent book

APhilosopher Looks at Science

, Nancy Cartwright revisits some ofthe longstanding themes of her work in the philosophy of science. In anearlier post, I discussed what she has to say in the first chapterabout theory and experiment. Let’s looknow at what she says in her second chapter about reductionism, of which she haslong been critical.

In hersuperb recent book

APhilosopher Looks at Science

, Nancy Cartwright revisits some ofthe longstanding themes of her work in the philosophy of science. In anearlier post, I discussed what she has to say in the first chapterabout theory and experiment. Let’s looknow at what she says in her second chapter about reductionism, of which she haslong been critical. Reductionismdoes not have quite the same hold in philosophy of science that it once did, havingbeen subjected to powerful attack not only from Cartwright, but from PaulFeyerabend, JohnDupré, and many others. (Idiscuss the anti-reductionist literature in detail in Aristotle’sRevenge.) Still, the ideathat whatever is real is somehow ultimately nothing more than what can inprinciple be described in the language of a completed physics exerts a powerfulhold on many. Cartwright cites JamesLadyman and Don Ross as adherents of this view, and AlexRosenberg is another prominent advocate. As Cartwright notes, in contemporary writingabout science, the lure of reductionism is especially evident in discussions ofthe purported implications of neuroscience for topics like free will.

Cartwrightsets the stage for her discussion by quoting a famous passage from physicistSir Arthur Eddington’s book TheNature of the Physical World:

I have settled down to the task ofwriting these lectures and have drawn up my chairs to my two tables. Two tables! Yes; there are duplicates of every object about me – two tables, twochairs, two pens…

One of them has been familiar to mefrom earliest years. It is a commonplaceobject of that environment which I call the world. How shall I describe it? It has extension; it is comparativelypermanent; it is coloured; above all it is substantial… [I]f you are a plain commonsense man, not toomuch worried with scientific scruples, you will be confident that youunderstand the nature of an ordinary table…

Table No. 2 is my scientific table…It does not belong to the world previously mentioned – that world whichspontaneously appears around me when I open my eyes... My scientific table ismostly emptiness. Sparsely scattered inthat emptiness are numerous electric charges rushing about with great speed;but their combined bulk amounts to less than a billionth of the bulk of thetable itself…

There is nothing substantial about my second table. It isnearly all empty space – space pervaded, it is true, by fields of force, butthese are assigned to the category of “influences”, not of “things”. (pp.xi-xiii)

Now, reductionismholds that in some sense the first table is really “nothing but” the secondtable – or even that the first table does not, strictly speaking, really existat all, and that only the second table does (though philosophers typicallycharacterize the latter sort of view as eliminativist rather thanreductionist).

Reduced reductionism

The firstconsideration Cartwright raises to illustrate how problematic reductionism isconcerns the way reductionists have, over the last few decades, repeatedly hadto qualify their claims. The ambitionsof reductionism have, you might say, been greatly reduced. Bold type-typereductionism gave way first to a weaker token-tokenreductionism, and then to yet weaker superveniencetheories.

Type-typereductionist theories hold that each typeof feature described at some higher-level science can be identified with some type of feature described at alower-level science, and ultimately at the level of physics. Perhaps the best-known theory of this kind isthe original mind-brain identity theory,which holds that every type of psychological state (the belief that it israining, the belief that it is sunny, the desire for a cheeseburger, the fearthat the stock market will crash, etc.) can be identified with some specifictype of brain process. A stock examplefrom the physical sciences would be the claim that temperature is identical tomean kinetic energy.

AsCartwright notes, one problem with this sort of view is that it is difficult tofind plausible cases of successful type-type reductions beyond such stockexamples. Another is that the stockexamples themselves are not in fact unproblematic. “Reduction” claims seem really to be eliminativistclaims after all. For example, given theso-called reduction of temperature, it’s not that what we’ve always understoodto be temperature is really just mean kinetic energy. It’s that what we’ve always understood to betemperature is not real after all (or exists only as a quale of our experienceof the physical world, rather than something there in the physical worlditself) and all that really exists is mean kinetic energy instead.

A problemwith supposing otherwise is that the laws that govern the features of somehigher-level description and the laws that govern the features of some allegedlycorresponding lower-level description can yield conflicting predictions. One way to think about this – though notCartwright’s own example – is in terms of DonaldDavidson’s view that descriptions at the psychological level are notlaw-governed in the way that the materialist supposes that descriptions at theneurological level are. Hence, even if abrain event of a certain type is strictly predictable, the corresponding mentalevent will not be. Given this sort ofmismatch, there is pressure on the type-type reductionist to treat thehigher-level description as not strictly true.

Anespecially influential consideration that led philosophers to abandon type-typereductionism is the “multiple realizability” problem – the fact thathigher-level features can be “realized in” more than one type of lower-levelfeature, so that there is no smooth mapping of higher-level types on tolower-level types of the kind an ambitious reductionist project aims for. In the case of the mind-brain identitytheory, the problem is that the same mental state (believing that it israining, say) could plausibly be associated with different types of brainprocess in different people, or even in the same person at differenttimes. Or consider how an economicproperty like being one dollar can berealized in paper currency, in metal currency, or as an electronic record ofone’s bank account balance.

This ledphilosophers to embrace less ambitious token-tokenreductionist theories. The idea here isthat even if types of feature at ahigher level cannot be smoothly correlated with types of feature at a lower level, nevertheless every token or individual instance of a featureat the higher level can be identified with some token or individual instance ofa lower-level feature. For example, this particular instance of believing that it’s raining is identicalwith that particular instance of acertain type of brain process.

AsCartwright notes, however, token reductions in fact tend to yield, after all, typereduction claims of a sort. An examplewould involve disjunctive types atthe lower level of description. Forinstance, a token reductionist view of mind-brain relations may entail that atype of mental state like believing thatit is raining is identical to a “type” of neural property defined as being in brain state of type B1 OR being inbrain state of type B2 OR being in brain state of type B3 OR… And this will, in turn, open up thepossibility of a conflict between what the laws that govern the higher-leveldescription entail and what the laws that govern the lower-level descriptionentail.

If it isobjected that disjunctive “types” of the kind just described seem artificial, thatis certainly plausible. But the problem,as Cartwright notes, is that this illustrates how identifying what counts as aplausible type is going to require detailed metaphysical analysis, and cannotbe read off the science, as the reductionist supposes.

In anyevent, token-token reductionism gave way in turn to talk of supervenience. The basic idea here is that phenomena at somehigher level of description A superveneon phenomena at some lower level of description B just in case there could not be any difference at what happens atlevel A without some correspondingdifference in what happens at level B.

But exactlywhat this amounts to is not obvious, and debating the meaning of superveniencehas, Cartwright complains, been a bigger concern of philosophers thanexplaining exactly why anyone should believe in it in the first place. (More on this in a moment.) As its vagueness indicates, supervenience entailsan even weaker claim than token-token reduction. Though, in recent years, there has been a lotof heavy going about “grounding,” which, Cartwright notes, is stronger thansupervenience. The idea is that allfacts are “grounded” in the facts described at the level of physics, in thesense that whatever happens at the higher levels is “due to” what happens atthe lower, physics level. But here too, why suppose this is the case?

Groundless grounding

Where theclaim that everything supervenes on the level described by physics isconcerned, Cartwright says, there are three basic reasons given for it, none ofthem well worked out or convincing. First, there is a leap from the fact that the lower-level featuresdescribed by physics affect whathappens at the higher levels, to the conclusion that those features by themselvesentirely fix what happens at thehigher levels. This is simply a non sequitur.

Second,there is a leap from the supposition that successful reductions have beencarried out in a handful of cases, tothe conclusion that reductionism is ingeneral true. But this too is a non sequitur (and on top of that, thepremise is questionable). Third, thereis the claim that physicalistic reductionism is in fact the method appliedwithin science. But this, Cartwrightargues, is simply not true to the facts of actual scientific practice.

“Grounding”accounts of reduction suppose that the level described by physics is the sole cause of what happens at the higherlevels, and also that it is in no way itself caused by what happens at thehigher levels. These claims too, arguesCartwright, are not supported by actual scientific practice.

Here sheappeals in part to recent work in the philosophy of chemistry, in which twogeneral lines of anti-reductionist argument have been developed. The first and more ambitious of them arguesthat chemistry as a discipline rests on classificatory and methodologicalassumptions that are simply sui generisand make the features of the world it uncovers irreducible to those uncoveredby physics. The second does not rule outreductions a priori, but argues on acase by case basis that purported reductions have not in fact successfully beencarried out. (I discuss this work inphilosophy of chemistry at pp. 330-40 of Aristotle’sRevenge.)

But it isnot just that chemistry and other higher-level sciences are not in fact “allphysics” at the end of the day. AsCartwright emphasizes, “even physics isn’t all physics.” For one thing, “physics” covers a range ofbranches, theories, and practices, not all of which have been reduced to the mostfundamental theories. For another, eventhe fundamental theories themselves are not fully compatible with each other,the notorious inconsistency between quantum mechanics and the general theory ofrelativity being a longstanding and still unresolved problem. She adds:

The third and to me most importantpoint is that in real science about real systems in the real world, forpredictions and explanations of even the purest of physics results, physicsmust work in cooperation with a motley assembly of other knowledge, from othersciences, engineering, economics, and practical life. (p. 110)

Cartwrightthen goes on to describe in detail the Stanford Gravity Probe Bproject as an illustration of the vast quantity of theoretical knowledge andpractical know-how that are necessary in order to apply and test abstract physicaltheory, yet cannot itself be reduced to such theory. This recapitulates a longtime theme inCartwright’s work over the decades, viz. that the mathematical models and lawsof physics are idealized and simplified abstractionsfrom concrete physical reality, and do not themselves constitute or captureconcrete physical reality.

In short,reductionism, Cartwright judges, is poorly defined and poorly argued for. Its lingering prestige is unearned.

I’ve mainlyjust summarized Cartwright’s arguments here, since I sympathize with them andthey supplement those that I develop in Aristotle’sRevenge. They give us, though, onlyher case against the views sheopposes, rather than the positive account she’d put in place of them, which isdescribed later in the book. More onthat in a later post.

Relatedreading:

Dupréon the ideologizing of science

Scientism:America’s State Religion

October 12, 2023

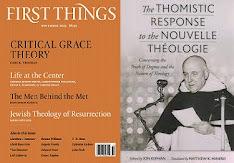

Thomism and the Nouvelle Théologie

My review of Jon Kirwan and Matthew Minerd’s important new anthology

TheThomistic Response to the Nouvelle Théologie

appears in the November 2023 issue of First Things.

My review of Jon Kirwan and Matthew Minerd’s important new anthology

TheThomistic Response to the Nouvelle Théologie

appears in the November 2023 issue of First Things.

October 10, 2023

A little logic is a dangerous thing

Some famousand lovely lines from Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” observe:

Some famousand lovely lines from Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” observe:A little learning is a dangerous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring.

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Think of theperson who has read one book on a subject and suddenly thinks he knowseverything. Or the beginning student ofphilosophy whose superficial encounter with skeptical arguments leads him todeny that we can know anything. A deeperinquiry, if only it were pursued, would in each case yield a more balancedjudgement.

Similardelusions of competence often afflict those who have studied a littlelogic. ElsewhereI’ve discussed the phony rigor often associated with the application of formalmethods. Here, however, what I have inmind is the abuse of a more elementary part of logic – the study of fallacies(that is to say, of common errors in reasoning).

The principle of charity

Beginningstudents of logic, when they first learn the fallacies, often start thinkingthey can see them everywhere – or more precisely, everywhere in the argumentsof people whose opinions on politics or religion they already disagree with,though not so much in the arguments of people on their own side. (What are the odds?) A good teacher will inform them thatknowledge of the fallacies must be applied in conjunction with what is calledthe “principle of charity.” Thisprinciple tells us that, when an argument that could be read as committing a fallacy could also be plausiblyinterpreted instead in a different way, we should presume that the latter interpretationis the correct one.

The point ofthis principle is not merely, or even primarily, to be nice. The point is rather that the study of logicis ultimately about pursuing truth,not about winning a debate. If wedismiss some argument too quickly because we haven’t considered a more charitableinterpretation, then we might miss out on learning some important truth –perhaps a truth that we are reluctant to learn, precisely because it comes fromsomeone we dislike.

But it’s notjust a failure to apply the principle of charity that can lead someone wronglyto accuse another of committing a fallacy. Sometimes people just don’t correctly understand the nature of someparticular fallacy.

Ad hominem?

Let’sconsider some common examples, beginning with the ad hominem fallacy. Whatmatters when evaluating an argument is whether its premises are true, andwhether the conclusion really follows from the premises, either with deductivevalidity or at least with significant probability. And that’s all that matters, logically speaking. The character of the person giving theargument is entirely irrelevant to that. Ad hominem fallacies arefallacies that neglect this fact – that pretend that by attacking a person insome way, you’ve thereby cast doubt on the argument the person has given or thetruth of some claim he has made.

There aredifferent ways this might go. Thecrudest way is the abusive ad hominem,wherein, instead of addressing the merits of some argument the person hasgiven, you simply call him names – “racist,” “fascist,” “commie,” or whatever –and pretend that sticking such a label on him casts doubt on what he said. Another common variation on the ad hominem fallacy is the circumstantial ad hominem or appeal to motive, wherein one attributesa suspect motive to the person and pretends that doing so casts doubt on whatthe person says. Of course, it doesnot. A good argument remains a goodargument, however bad the motives (or alleged motives) of the person giving it,and a bad argument remains a bad argument however good the motives of theperson giving it.

It iscrucial to emphasize, though, that calling someone a name, attributing badmotives to him, or in some other way attacking a person or his character is not in itself a fallacy. It amounts to a fallacy only when what is at issue, specifically, is themerits of some claim he made or some argument he gave, and instead ofaddressing that, you change the subject and attack theperson.

But ofcourse, there are other contexts where the subject is the person or his character, rather than some argument he gave. For example, if a jury is trying to determinewhether a person’s eyewitness testimony is reliable, a lawyer is not committingan ad hominem fallacy if he notesthat the witness has been caught in lies in the past, or is known to harbor apersonal grudge against the person he’s testifying against. Or, when you are deciding whether to believea used car salesman, you are not guilty of an ad hominem fallacy when considering that his motive to sell you acar might bias the advice he gives you. Again, in cases like these, what is at issue is not some argument theperson gave, which might be considered entirely apart from him. What is at issue is the credibility of theperson himself.

Or supposeyou call someone a “jerk” precisely because he is acting like a jerk. There is no fallacy in that. Indeed, there is no fallacy even if he is not acting like a jerk, but you’re justin a bad mood. Name-calling may bejustified in the one case and unjustified in the other, but it is not a fallacy if the context isn’t one wherethe cogency of some argument he gave is what at issue, and you’re distractingattention from that.

People areespecially prone to make the mistake of confusing attacks on a person with the ad hominem fallacy when the context is adebate or public exchange of some other kind – where, of course, one or bothsides may be making arguments. SupposePerson A and Person B are engaged in some public dispute (on a blog, onTwitter, or wherever). Suppose Person Aaddresses the arguments of Person B, but Person B refuses to respond in kind,resorting instead to ad hominemattacks, or mockery, or changing the subject. Suppose that Person A, appalled by this behavior, calls attention toPerson B’s personal failings – characterizing Person B as intellectuallydishonest, or as a sophist, or as a buffoon, or the like. And suppose that Person B then objects tothis and accuses Person A of committingan ad hominem fallacy.

Is Person Aguilty of such a fallacy? Of coursenot. He has not attacked Person B as a way of avoiding addressing PersonB’s claims or arguments. On thecontrary, he has addressed those claimsand arguments. His negative estimation ofPerson B’s character is a separatepoint, and a correct one. Person B – whether out of cluelessbefuddlement or cynical calculation – makes of the false accusation that PersonA is guilty of an ad hominem fallacya smokescreen to hide the fact that it is really Person B himself who is guilty of this.

In the caseI just described, a person is accused of committing an ad hominem fallacy when he is notin fact doing so. But it can also happenthat a person pretends (or maybe even sincerely believes) that he is notcommitting an ad hominem fallacy whenhe is fact doing so. To change my example a bit, suppose Person Aand Person B are engaged in some public dispute. Suppose Person B never addresses Person A’sarguments, but simply and repeatedly flings terms of abuse, questions hismotives, and so on, with the aim of undermining Person A’s credibility with hisreaders. Suppose Person A accuses PersonB of ad hominem fallacies, and PersonB responds: “I’ve committed no such fallacy! After all, using such terms of abuse is not by itself fallacious. It’s only a fallacy when addressing anargument, and I haven’t beenaddressing your arguments. I’m justtelling people what a horrible person you are.”

Is Person Bthus innocent of an ad hominemfallacy in this case? Not at all. He may not have committed this fallacy in a direct way, but he has still done so indirectly. True, he has avoided addressing any specific argument Person A hasgiven. Hence he has not in that way committed an ad hominem fallacy. At the same time, though, he has, through ad hominem abuse, tried to poison hisreaders’ minds against taking seriously anyargument that Person A might happen to give. Hence he has deployed a fallaciously adhominem tactic in a general way.

The bottomline is this. Is a speaker resorting to ad hominem abuse as a way of trying to avoid having to address some claim orargument another person has given? Ifso, he is guilty of an ad hominemfallacy. If not, then he is not guiltyof such a fallacy (whether or not his abusive language is unjustifiable forsome other reason – that’s a separatequestion).

Appeal to emotion?

An appeal to emotion fallacy is committedwhen, instead of trying to convince one’s listener of a certain conclusion byoffering reasons that provide actual logical support for that conclusion, oneplays on the listener’s emotions. The strengthof the emotional reaction makes the conclusion seem well-supported, when in fact the premises do not providestrong grounds for believing it.

But here itis important to emphasize that the presence of an emotional reaction does notby itself make an argumentfallacious, not even if the speaker foresees such a reaction and indeed even ifhe intends it. To take an artificial examplein order to illustrate the point, suppose some follower of Socrates, havingjust heard the fatal verdict, wants desperately to believe that his heroSocrates will somehow never die. Youhope to bring him back to reality, and present him with the following argument:

All men are mortal

Socrates is a man

Therefore, Socrates is mortal

He contemplates this reasoning, sighs heavily and resignshimself to the cold, hard truth. Theargument raises profound emotions in him, as you knew it would. But have you committed a fallacy of appeal toemotion? Obviously not. The argument is no less sound than it wouldbe if someone with no emotional reaction at all had heard it.

Still, you might think, the reason there is no fallacy hereis that the emotions in question are not such as to incline the person to want to believe the conclusion. Quite the opposite. But suppose the emotions in question were of that sort. For example, suppose one of Socrates’ enemiesfeared that the hemlock would not kill him, and worried that perhaps Socrateswas immortal and could never be gotten rid of. Suppose you present him withthe same argument just given. He isreassured. But have you now, in thiscase, committed a fallacy of appeal to emotion?

No. Here too, theargument remains just as sound as it would be if some unemotional person who couldn’tcare one way or the other about Socrates had heard it. But what if you not only know that the personwill be pleased by the conclusion, but intendfor him to be pleased by it? What ifyou hope that his positive emotional response to the argument will make himmore likely to accept it? Wouldn’t that make it a fallacious appeal toemotion?

No, it would not. Forthe bottom line is that the premises are clearly true and the conclusionclearly follows validly from them. Thepresence or absence of an emotional reaction, of whatever kind, does not changethat in the least. Hence there is nofallacy of appeal to emotion. Such afallacy is committed only when there is some logical gap in the support the premises supply the conclusion,which the emotional reaction is meant to fill. But there is no such gap – and thus no fallacy.

Indeed, an emotional reaction can in some cases get a personto be more rational, not less. In the second example, the person’s fear thatSocrates might be immortal is unreasonable. He’s letting his fear of Socrates’ influence within Athens get the betterof him, and lead him to paranoid delusions. The argument you give him, preciselybecause it is pleasing to him, draws his attention away from these paranoidfeelings and back to reality.

Again, the example is admittedly artificial. But there are many topics that dorealistically carry heavy emotional baggage, yet where this does not entailthat arguments having to do with them must be guilty of the fallacy of appealto emotion. Matters of life and death –war, abortion, capital punishment, and the like – are like that. No matter what conclusions you draw and whatpremises you appeal to, they are bound to generate emotional reactions of somekind in your listener. But that does notentail that you are guilty of a fallacy of appeal to emotion.

The bottom line is this. Are the premises of the argument true? Do they in fact provide logical support for the conclusion (whetherdeductive validity or inductive strength)? Then the argument is not guilty of a fallacy of appeal to emotion,whether or not it also happens to generate an emotional reaction in thelistener, and whatever that reaction happens to be.

Slippery slope?

A third fallacy that is widely misunderstood is the slippery slope fallacy. Someone commits this fallacy when he claimsthat a certain view or policy will lead to disastrous consequences, but withoutoffering adequate support for this judgement. It is an instance of the more general error of jumping to conclusions orinferring well beyond what the evidence appealed to would support.