Edward Feser's Blog, page 16

July 19, 2023

What is classical theism?

Recently, Iwas interviewed by John DeRosa for the Classical Theism Podcast. The focus of our discussion is my essay “Whatis Classical Theism?,” which appears in the anthology

ClassicalTheism: New Essays on the Metaphysics of God

, edited by Jonathan Fuquaand Robert C. Koons. We also addresssome other matters, such as the book on the soul that I’m currently workingon. You can listen to the interview here.

Recently, Iwas interviewed by John DeRosa for the Classical Theism Podcast. The focus of our discussion is my essay “Whatis Classical Theism?,” which appears in the anthology

ClassicalTheism: New Essays on the Metaphysics of God

, edited by Jonathan Fuquaand Robert C. Koons. We also addresssome other matters, such as the book on the soul that I’m currently workingon. You can listen to the interview here.

July 18, 2023

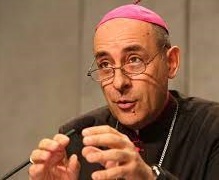

Archbishop Fernandez’s clarification

Recently, itwas announced that Archbishop Víctor Manuel Fernandez would become the newprefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF). As I noted in anarticle last week, Pope Francis has stated that he wants the DDF under thenew prefect to operate in a “very different” way than it has in the past, when “possibledoctrinal errors were pursued.” Thearchbishop himself has said that he wants the DDF to pursue “dialogue” and to avoid“persecutions and condemnations” or “the imposition of a single way of thinking.” He also indicated that he took this to mark adifference from the way the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (as theDDF was known until recently) has operated in recent decades. As I argued in the article, the logicalimplication of the pope’s and archbishop’s words seemed to be that the DDF wouldlargely no longer be exercising its traditional teaching function.

Recently, itwas announced that Archbishop Víctor Manuel Fernandez would become the newprefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF). As I noted in anarticle last week, Pope Francis has stated that he wants the DDF under thenew prefect to operate in a “very different” way than it has in the past, when “possibledoctrinal errors were pursued.” Thearchbishop himself has said that he wants the DDF to pursue “dialogue” and to avoid“persecutions and condemnations” or “the imposition of a single way of thinking.” He also indicated that he took this to mark adifference from the way the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (as theDDF was known until recently) has operated in recent decades. As I argued in the article, the logicalimplication of the pope’s and archbishop’s words seemed to be that the DDF wouldlargely no longer be exercising its traditional teaching function. However, in aninterview with The Pillar yesterday,the archbishop was asked whether the DDF would move away from its traditionalrole in safeguarding doctrine, and he answered:

Look, if you read the pope's lettercarefully, it is clear that at no time does he say that the function ofrefuting errors should disappear.

Obviously, if someone says that Jesusis not a real man or that all immigrants should be killed, that will requirestrong intervention.

But at the same time, that[intervention] can be an opportunity to grow, to enrich our understanding.

For example, in those cases, it wouldbe necessary to accompany that person in their legitimate intention to bettershow the divinity of Jesus Christ, or it will be necessary to talk about someimperfect, incomplete or problematic immigration legislation.

In the letter, the pope says veryexplicitly that the dicastery has to “guard” the teaching of the Church. Only that at the same time – and this is hisright – he asks me for a greater commitment to help the development of thought,such as when difficult questions arise, because growth is more effective thancontrol.

Heresies were eradicated better andfaster when there was adequate theological development, and they spread andperpetuated when there were only condemnations.

But Francis also asks me to helpcollect the recent magisterium, and this evidently includes his own. It is part of what must be “guarded.”

Endquote. It is only just to acknowledgethat these words clearly state that the DDF’s traditional function of rebutting“possible doctrinal errors” will notbe abandoned. All well and good.

However, thesenew comments make the significance of the earlier ones I quoted in my previousarticle less clear, not more. For thepope and the archbishop indicated that they want the DDF to operate in a way thatis “very different” from the way it has operated in recent decades. But if the DDF is going to continue with its “functionof refuting errors,” including “strong intervention” to rebut those who promotesuch errors, how does that differ from how the CDF operated in recent decades?

Presumablythe answer has to do with an emphasis on “accompanying” the person guilty ofthe errors, rather than “only condemnations.” But this too is not in fact a departure from the way the CDF operatedunder prefects like cardinals Ratzinger, Levada, Müller, and Ladaria. For example, though Ratzinger was caricaturedin the liberal press as a “panzer cardinal,” that is the opposite of how heactually ran the CDF. As hecomplained in 1988:

The mythical harshness of the Vaticanin the face of the deviations of the progressives is shown to be mere emptywords. Up until now, in fact, onlywarnings have been published; in no case have there been strict canonicalpenalties in the strict sense.

For instance,theologian Edward Schillebeeckx was investigated by the CDF under Ratzinger,for Schillebeeckx’s dubious Christological opinions – precisely the sort ofthing Archbishop Fernandez offers as an example of an error the DDF should dealwith. But Schillebeeckx was given theopportunity to explain and defend his views, and his books were nevercondemned. More famously, Hans Küng losthis license to teach Catholic theology because of his heterodox views on papalinfallibility and other matters. But he continuedteaching at the same university and remained a priest in good standing. So far was he from being “condemned” by theChurch that one of Ratzinger’s first acts after being elected Pope Benedict XVIwas to invite Küng over for a friendly dinner and theological conversation.

In reality,the person dealt with most harshly by the CDF under Ratzinger was not aprogressive, but rather someone with whom Ratzinger was accused of being toosympathetic – namely, the traditionalist Archbishop Lefebvre, who was excommunicatedin 1988. And it is preciselytraditionalists whom PopeFrancis has also dealt with most harshly during his own pontificate. Indeed, Pope Francis’s treatment oftraditionalists seems the reverse of what Archbishop Fernandez characterizes asan “accompanying” rather than “condemning” approach.

Hence, whilethe archbishop’s most recent remarks are welcome, they make the import of hisearlier remarks, and the pope’s, murkier rather than clearer. In any event, if a patient and charitableapproach to dealing with doctrinal disputes is what the archbishop is after,then PopeBenedict XVI in fact provided a model to emulate rather than abandon. And Pope Francis too provides something of aroadmap, insofar as hehas many times said that he welcomes respectful criticism.

ArchbishopFernandez ends the interview by asking for prayers as he takes up his new post,and makes clear that he would be “grateful” for the prayers of his critics noless than those of his supporters. It wouldbe most contrary to justice and charity for anyone to refuse this humblerequest, and I happily offer up my own prayers for the archbishop.

July 14, 2023

Cardinal Newman, Archbishop Fernandez, and the “suspended Magisterium” thesis

St. JohnHenry Newman famously noted thatduring the Arian crisis, “the governing body of the Church came short” infighting the heresy, and orthodoxy was preserved primarily by the laity. “The Catholic people,” he says, “were theobstinate champions of Catholic truth, and the bishops were not.” Even Pope Liberius temporarily caved in topressure to accept an ambiguous formula and to condemn St. Athanasius, thegreat champion of orthodoxy. Newmanwrote:

St. JohnHenry Newman famously noted thatduring the Arian crisis, “the governing body of the Church came short” infighting the heresy, and orthodoxy was preserved primarily by the laity. “The Catholic people,” he says, “were theobstinate champions of Catholic truth, and the bishops were not.” Even Pope Liberius temporarily caved in topressure to accept an ambiguous formula and to condemn St. Athanasius, thegreat champion of orthodoxy. Newmanwrote:The body of the Episcopate wasunfaithful to its commission, while the body of the laity was faithful to itsbaptism… at one time the pope, at other times a patriarchal, metropolitan, orother great see, at other times general councils, said what they should nothave said, or did what obscured and compromised revealed truth; while, on theother hand, it was the Christian people, who, under Providence, were theecclesiastical strength of Athanasius, Hilary, Eusebius of Vercellae, and othergreat solitary confessors, who would have failed without them.

As Newmanemphasized, this is perfectly consistent with the claim that the pope andbishops “might, in spite of this error, be infallible in their ex cathedra decisions.” The problem is not that they made ex cathedra pronouncements and somehowerred anyway. The problem is that therewas an extended period during which, in their non-ex cathedra (and thus non-infallible) statements and actions, theypersistently failed to do their duty. Inparticular, Newman says:

There was a temporary suspense of thefunctions of the ‘Ecclesia docens’ [teaching Church]. The body of Bishopsfailed in their confession of the faith. They spoke variously, one against another; there was nothing, afterNicaea, of firm, unvarying, consistent testimony, for nearly sixty years.

Newman goeson to make it clear that he is not sayingthat pope and bishops lost the power to teach, and in a way that was protectedfrom error when exercised in an excathedra fashion. Rather, while theyretained that power, they simply did not use it.

In recentyears, some have borrowed Newman’s language and suggested that with thepontificate of Pope Francis, we are once again in a period during which theexercise of the Magisterium or teaching authority of the Church has temporarilybeen suspended. Now, this “suspendedMagisterium” thesis is not correct as a completely general description ofFrancis’s pontificate. For there clearlyare cases where he has exercised his magisterial authority – such as when,acting under papal authorization, the Congregation for the Doctrine of theFaith under its current prefect Cardinal Ladaria hasissued various teaching documents.

To be sure,there may nevertheless be particular caseswhere the “suspended Magisterium” characterization is plausible. Consider the heated controversy that followedupon Amoris Laetitia, and inparticular the dubia issued by fourcardinals asking the pope to reaffirm several points of irreformable doctrinethat Amoris seems to conflictwith. As Fr. John Hunwicke hasnoted, because Pope Francis has persistently refused to answer thesedubia, he can plausibly be said atleast to that extent to havesuspended the exercise of his Magisterium. Again, this does not mean that he has lost his teaching authority. The point is rather that, insofar as he hasrefused to answer these five specific questions put to him, he has not, atleast with respect to those particular questions, actually exercised thatauthority. As Fr. Hunwicke notes, hecould do so at any time, so that his teaching authority remains.

Again,though, it doesn’t follow that the “suspended Magisterium” thesis is correct asa general description of Pope Francis’s pontificate up to now. However, recently there has been a newdevelopment which, it seems to me, could make the thesis more plausible as acharacterization of the remainder of Francis’s pontificate. The pope has announced that Cardinal Ladariawill soon be replaced by Archbishop Víctor Manuel Fernandez as Prefect of whatis now called the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF).

Fernandez isa controversial figure, in part because heis widely thought to have ghostwritten Amoris. What is relevant to the present point,however, is what Pope Francis and the archbishop himself have said about thenature of his role as Prefect of DDF. Inapublicly-released letter to Fernandez describing his intentions, thepope writes:

I entrust to you a task that Iconsider very valuable. Its centralpurpose is to guard the teaching that flows from the faith in order to “to givereasons for our hope, but not as an enemy who critiques and condemns.”

The Dicastery over which you willpreside in other times came to use immoral methods. Those were times when, rather than promotingtheological knowledge, possible doctrinal errors were pursued. What I expect from you is certainly somethingvery different…

You know that the Church “grow[s] inher interpretation of the revealed word and in her understanding of truth”without this implying the imposition of a single way of expressing it. For “Differing currents of thought inphilosophy, theology, and pastoral practice, if open to being reconciled by theSpirit in respect and love, can enable the Church to grow.” This harmonious growth will preserveChristian doctrine more effectively than any control mechanism…

“The message has to concentrate onthe essentials, on what is most beautiful, most grand, most appealing and atthe same time most necessary.” You arewell aware that there is a harmonious order among the truths of our message,and the greatest danger occurs when secondary issues end up overshadowing thecentral ones.

There areseveral points to be noted here. First,the pope makes it clear that he wants the DDF under Archbishop Fernandez tooperate in a “very different” way than it has in the past. Second, he indicates that part of what thisentails is that the DDF should focus on “essentials” and “central” issuesrather than “secondary issues.” PopeFrancis doesn’t spell out precisely what this means, but the context indicatesthat he regards many of the issues the CDF has dealt with in the past to be“secondary.” Third, when the DDF doesaddress an issue, it should not do so as a “control mechanism” that “pursue[s]…possible doctrinal errors” or “impos[es]… a single way of expressing” theFaith. Fourth, it should speak “not asan enemy who critiques and condemns.”

In arecent interview, Archbishop Fernandez has commented on his ownunderstanding of his role as head of DDF, and his remarks echo and expand uponthe pope’s. Fernandez says:

So you can imagine that being namedin this place is a painful experience. Thisdicastery that I am going to lead was the Holy Office, the Inquisition, whicheven investigated me…

There were great theologians at thetime of the Second Vatican Council who were persecuted by this institution…

[The pope] told me: ‘Don't worry, Iwill send you a letter explaining that I want to give a different meaning tothis dicastery, that is, to promote thought and theological reflection indialogue with the world and science, that is, instead of persecutions andcondemnations, to create spaces for dialogue.’…

Thearchbishop went on to say that he wants the DDF to avoid:

All forms of authoritarianism thatseek to impose an ideological register; forms of populism that are alsoauthoritarian; and unitary thinking. Itis obvious that the history of the Inquisition is shameful because it is harsh,and that it is profoundly contrary to the Gospel and to Christian teachingitself. That is why it is so appalling…

But current phenomena must be judgedwith the criteria of today, and today everywhere there are still forms ofauthoritarianism and the imposition of a single way of thinking.

Here toothere are several points to be noted. First, like the pope, the archbishop indicates that he wants the DDF tomove away from the sort of activity that occupied it in the past, but he is abit more specific than the pope was. Hecites, as examples, investigations of theologians at around the time of VaticanII, and the investigation the CDF made of his own views (which, as theinterview goes on to make clear, had to do with some things he’d written on thetopic of homosexuality). So, he doesn’thave long-ago history in mind, but the recentactivity of the CDF. Furthermore, hecriticizes even this sort ofinvestigation (and not merely the harsh methods associated with theInquisition) as a kind of “persecution.”

Second, thearchbishop says that what the pope wants is for the DDF not only to avoid such “persecutions”of individuals, but also to refrain from “condemnations” of their views. In place of such persecutions andcondemnations, he wants “dialogue.” Third,he takes this to entail that the DDF will refrain from “the imposition of asingle way of thinking.”

Taking allof Pope Francis’s and Archbishop Fernandez’s comments into account yields thefollowing. The DDF, which has heretoforebeen the main magisterial organ of the Church:

(a) will infuture focus on central and essential doctrinal matters and pay less attentionto secondary ones;

(b) where itdoes address some such matter, will not approach it by way of ferreting out doctrinalerrors or imposing a single view;

(c) willemphasize dialogue with individual thinkers rather than the investigation,critique, and condemnation of their views;

(d) should inall these respects be understood as playing a role very different from the oneplayed by the CDF in recent decades.

In short,this main magisterial organ of the Church willlargely no longer be exercising its magisterial function. It will issue statements about central themesof the Faith, but it will no longer pay as much attention to secondarydoctrinal matters, will no longer pursue the identification and condemnation oferrors, will no longer investigate wayward theologians or warn about theirworks, and will in general promote dialogue rather than impose a singleview. Hence it will no longer do thesort of job it did under popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI, let alone the jobthat Newman says the bishops failed to do during the Arian crisis. And notice that, followed out consistently,this means that the teaching of Pope Francis himself (let alone the deposit ofFaith it is his job to safeguard) is not something the DDF is in the businessof imposing. It too would simply amountto a further set of ideas to dialogue about.

The implicationsof these recent remarks are, accordingly, quite dramatic. And while it is possible that the remarkswill be clarified and qualified after Archbishop Fernandez takes office, thetrend of Francis’s pontificate is precisely one of avoiding the clarificationand qualification of theologically problematic statements. But whereas, in the past, this avoidancepertained to a handful of specific issues, it now seems as if it is beingraised to the level of general DDF policy.

If so, letus hope that this “temporary suspense of the functions of the ‘Ecclesia docens’”does not last sixty years, as the previous one did. St. John Henry Newman, ora pro nobis.

July 7, 2023

The vice of insensibility

Temperance ormoderation is the virtue governing the enjoyment of sensory pleasures. In particular, and as Aquinas says,“temperance is properly about pleasures of meat and drink and sexual pleasures.” These pleasures reflect our bodily nature(which is why angels, unlike us, neither need the virtue of temperance norexhibit the vices opposed to it). Specifically, they reflect our needs for self-preservation and forpreservation of the species. Eating anddrinking exist in order to meet the first need and sex exists in order to meetthe second. The pleasures associatedwith these activities exist in turn so that we will be drawn to carrying themout. And temperance is needed so that thepleasures will perform that motivating task successfully. In short, temperance exists in order that wewill be drawn to the right kinds of sensory pleasures and to the right degree;those pleasures exist for the sake of encouraging eating, drinking, and sexualintercourse at the right times and in the right ways; and those actions exist,in turn, in order that the individual and species will carry on.

Temperance ormoderation is the virtue governing the enjoyment of sensory pleasures. In particular, and as Aquinas says,“temperance is properly about pleasures of meat and drink and sexual pleasures.” These pleasures reflect our bodily nature(which is why angels, unlike us, neither need the virtue of temperance norexhibit the vices opposed to it). Specifically, they reflect our needs for self-preservation and forpreservation of the species. Eating anddrinking exist in order to meet the first need and sex exists in order to meetthe second. The pleasures associatedwith these activities exist in turn so that we will be drawn to carrying themout. And temperance is needed so that thepleasures will perform that motivating task successfully. In short, temperance exists in order that wewill be drawn to the right kinds of sensory pleasures and to the right degree;those pleasures exist for the sake of encouraging eating, drinking, and sexualintercourse at the right times and in the right ways; and those actions exist,in turn, in order that the individual and species will carry on.It goeswithout saying that it is extremely common for people to seek these pleasures toofrequently, or at the wrong time, or in the wrong way. In doing so they exhibit the vice of intemperance or licentiousness. But mostvirtues are means between extremes, one of excess and one of deficiency. And that is true in this case. Intemperance is the vice of excess where sensorypleasure is concerned. The vice ofdeficiency in this area – of being toolittle disposed to seek sensory pleasure – is known as insensibility. Becauseintemperance is far and away the more common vice, especially today,insensibility is rarely discussed. But,precisely because intemperance is more common, it is important to understandinsensibility, because those rightly concerned to avoid the first vicesometimes overreact and fall into the second.

Aquinas sumsup as follows the reason why insensibility is a vice:

Whatever is contrary to the naturalorder is vicious. Now nature hasintroduced pleasure into the operations that are necessary for man's life. Wherefore the natural order requires that manshould make use of these pleasures, in so far as they are necessary for man'swell-being, as regards the preservation either of the individual or of thespecies. Accordingly, if anyone were toreject pleasure to the extent of omitting things that are necessary for nature'spreservation, he would sin, as acting counter to the order of nature. And this pertains to the vice ofinsensibility. (SummaTheologiae II-II.142.1)

Hence, hegoes on to say, it is an error to think that avoiding pleasure altogether is agood way to avoid sin. On the contrary,“in order to avoid sin, pleasure must be shunned, not altogether, but so thatit is not sought more than necessity requires.”

Now, doesthis entail that it is always andinherently wrong to avoid a certain kind of sensory pleasurealtogether? And what does it mean for akind of pleasure to be “necessary”? Let’s address these questions in order. First, Aquinas acknowledges that there are cases where it is good toshun sensory pleasure. In the samearticle, he writes:

It must, however, be observed that itis sometimes praiseworthy, and even necessary for the sake of an end, toabstain from such pleasures as result from these operations. Thus, for the sake of the body's health,certain persons refrain from pleasures of meat, drink, and sex; as also for thefulfilment of certain engagements: thus athletes and soldiers have to denythemselves many pleasures, in order to fulfil their respective duties. On like manner penitents, in order to recoverhealth of soul, have recourse to abstinence from pleasures, as a kind of diet,and those who are desirous of giving themselves up to contemplation and Divinethings need much to refrain from carnal things. Nor do any of these things pertain to the vice of insensibility, becausethey are in accord with right reason.

Endquote. Similarly, Aquinas says thatforsaking marriage (and thus the pleasure of sex) for the sake of the highergood of complete devotion to the contemplation of God is not only lawfulbut superior to marriage.

However, ineach of these cases, sensory pleasure is forsaken for the sake of some specialsituation or state in life. Absent suchcircumstances, it can be vicious to eschew the pleasures in question. For example, suppose a person is married, anddesires to abstain from sex altogether for the sake of complete devotion tospiritual things, but his spouse has not consented to this. Then, as Aquinas says,it would be wrong to refuse sexual intercourse with the spouse. In the typical case, sexual pleasure issimply a normal part of married life, and ought no more to be shunned than thepleasures of eating and drinking that are also a normal part of life.

What, then,of the other qualification Aquinas makes, to the effect that “pleasure must beshunned, not altogether, but so that itis not sought more than necessityrequires”? Some readers might assumethat he is saying that we ought to indulge in those pleasures that simplycannot be avoided (such as the minimal pleasure that accompanies any normal actof eating or having sexual relations) but should avoid any pleasure that goesbeyond that.

But that is notwhat he is saying. To see why, considerfirst what more he says about the nature of the pleasures associated witheating, drinking, and sex, in the context of defending his view that sensorypleasures have primarily to do with the sense of touch. He allows that there are secondary pleasuresassociated with these activities that involve the other senses:

Temperance is about the greatestpleasures, which chiefly regard the preservation of human life either in thespecies or in the individual. On thesematters certain things are to be considered as principal and others assecondary. The principal thing is theuse itself of the necessary means, of the woman who is necessary for thepreservation of the species, or of food and drink which are necessary for thepreservation of the individual: while the very use of these necessary thingshas a certain essential pleasure annexed thereto. In regard to either use we consider assecondary whatever makes the use more pleasurable, such as beauty and adornmentin woman, and a pleasing savor and likewise odor in food. (Summa Theologiae II-II.141.5)

In otherwords, with food and drink, though what is absolutely inseparable from them arepleasures known through touch (such as a pleasing texture, temperature, and thelike), there are also secondary pleasures of taste and smell. Nor are these somehow pointless, for as hegoes on to say, they “make the food pleasant to eat, in so far as they aresigns of its being suitable for nourishment.” Similarly, though the pleasure of sex involves primarily the sense oftouch, the activity is made “more pleasurable… [by] beauty and adornment inwoman,” and these pleasures are associated with sight more than touch.

Now, itwould be absurd to suppose that Aquinas thinks that temperance allows for theenjoyment only of what is “necessary” in the strictest sense of beingabsolutely inseparable from food, drink, and sex – for example, that it istemperate to enjoy the texture of food but intemperate to enjoy its taste orodor, and temperate to enjoy the feel of sexual intercourse but intemperate tofind pleasure in one’s wife’s beauty. For one thing, these pleasures, despite being “secondary” in Aquinas’ssense, are obviously as naturally associated with food, drink, and sex as thepleasures of touch are. Nature makesfood taste and smell good for the same reason it makes eating it feel good,namely to get us to eat. And the beautyof the female body, no less than the pleasures of touch associated withintercourse, is obviously also part of nature’s way of getting men togetherwith women so that they will have children.

For anotherthing, Aquinas explicitly says elsewhere that temperance allows for theenjoyment not only of pleasures that are necessary in the strictest sense, but alsothose that are necessary in a looser sense or even not necessary at all:

The need of human life may be takenin two ways. First, it may be taken inthe sense in which we apply the term “necessary” to that without which a thingcannot be at all; thus food is necessary to an animal. Secondly, it may be taken for somethingwithout which a thing cannot be becomingly. Now temperance regards not only the former of these needs, but also thelatter. Wherefore the Philosopher says(Ethic. iii, 11) that “the temperate man desires pleasant things for the sakeof health, or for the sake of a sound condition of body.” Other things that are not necessary for thispurpose may be divided into two classes. For some are a hindrance to health and a sound condition of body; andthese temperance makes not use of whatever, for this would be a sin againsttemperance. But others are not ahindrance to those things, and these temperance uses moderately, according tothe demands of place and time, and in keeping with those among whom onedwells. Hence the Philosopher (Ethic.iii, 11) says that the “temperate man also desires other pleasant things,”those namely that are not necessary for health or a sound condition of body, “solong as they are not prejudicial to these things.” (Summa Theologiae II-II.141.6)

So, sensorypleasure can in a relevant sense be “necessary,” for Aquinas, not only when itis strictly unavoidable in order for eating, drinking, and sex to exist at all,but also when it is simply “becoming” in relation to these things. And temperance allows for pleasures as longas they are not a “hindrance” or “prejudicial” to health and soundness of body,even if they are not quite necessary either. One need merely consider the “demands of place and time, and [what is]in keeping with those among whom one dwells.”

Aquinas doesnot think, then, that temperancerequires a meal or sexual relations to be quick and businesslike, such that anypleasure beyond the bare minimum associated with that would amount tointemperance. And that is, of course,just common sense. It is normal forhuman beings simply to get on with eating, drinking, or lovemaking withoutscrupling over whether they are taking too much pleasure in it. Indeed, apart from cases where someoneclearly has disordered appetites (alcoholism, hypersexuality, or the like) itwould ordinarily be neurotic and spiritually unhealthy to fret over such things– to worry that one is guilty of sin for eating an extra slice of bacon, orkissing one’s spouse with great passion, or what have you.

That is notto deny that there can be excess short of addictions like the ones mentioned. For example, Aquinas notesthat one manifestation of the vice of gluttony is evident in those preoccupiedwith “food prepared too nicely – I.e. ‘daintily.’” I would suggest that the sort of thing he hasin mind is evident today among people who call themselves “foodies” – alwaysgoing on about food in an embarrassingly overenthusiastic way, endlesslyseeking out new culinary adventures, and so on. Similarly, even people who are not quite sex addicts can develop anunhealthy preoccupation with it. Whenfood, drink, or sex becomes, not just a background part of normal human life,but a fixation, that is an indication that someone has fallen into hedonism andthus the vice of intemperance.

Then thereis the fact that one might now and again forego the pleasures of food, drink,or sex not because enjoying them would be excessive or in any other waydisordered, but simply in a spirit of sacrifice – that is to say, not out of ajudgment that they are bad, but rather out of a judgment that they are good butthat it would be better still to do without them for the sake of some higherend (to do penance, to develop self-discipline, or whatever).

However,supposing that one is neither engaged in such occasional asceticism nor proneto hedonism, then, as I have said, it would be neurotic and spirituallyunhealthy to fret over the minutiae of everyday eating, drinking, and maritalsexual relations – to try to ferret out subtle sins, in oneself or others,relating to these things. A person whotends to be overly suspicious of such pleasures is often characterized as aprig, killjoy, or “stick in the mud,” and I’d suggest that this character typeis one manifestation of the vice of insensibility. Specifically, it involves insensibility of akind related to scrupulosity, the obsessive tendency to see sin where it doesnot exist. It can arise as anoverreaction to the opposite extreme vice of intemperance, either in oneself orin the larger society around one.

However,that is not the only source of the vice of insensibility. Some people are simply “cold fish,” eschewingsensory pleasures of one kind or another not because they suspect them of beingsinful but rather because they just lack much if any interest in them. Of course, there is a normal range ofvariation in appetites for food, drink, and sex, just as there are normalranges of variation with respect to all human traits. But just as some people have extremely strongappetites for one or more of these things and thus are in greater danger thanothers of falling into intemperance, so too do some people have extremely weakappetites and are in greater danger of falling into insensibility.

Whatever thepsychological factors behind a given person’s insensibility, it is truly a vicerather than a mere variation in temperament, because it can harm both theperson himself and those with whom he lives. In his 1953 dissertation TheThomistic Concept of Pleasure, Charles Reutemann explains the individual’sneed for pleasure as follows:

The conscious suppression of pleasurewithout some form of sublimation can have very harmful effects, since therebyan appetitive tendency is frustrated in its natural movement. Not only would the appetitive movement tend tobecome atrophied, but the whole man would be reduced to a state of sorrow anddepression…

Inasmuch as [intellectual] activitieshave constant recourse to the ministrations of sense, there must be a restingto relieve the attendant “soul-weariness.”

If pleasure is necessary as a curefor “soul-weariness,” it must be more necessary for the body, since even“soul-weariness” is reductively attributed to the body. For two reasons the body demands pleasure: asa remedy against pain, and as an incentive to its own activity which isgenerally laborious.(p. 22)

And on thenecessity of pleasure to human social life, Reutemann writes:

Pleasure contributes mightily to theestablishing and facilitating of harmonious relations among men. For, just as society would lose its integrityif men did not respect and manifest the truth to one another, so it would loseits intrinsic dynamism if pleasure were not used as a “lubricant” to facilitateinter-personal relationships. Givingpleasure and living agreeably with one’s neighbor is considered by St. Thomasto be a matter of natural equity. (p.23)

Reutemannhas pleasure in general in mind here, but let’s consider, specifically, thepleasures governed by temperance. Inhuman beings, eating is not mere feeding, but the having of a meal, which iscommonly a social occasion. Drinking,too, is something people prefer to do together – in a bar, at a party, whilewatching a game together, or what have you. Routinely to have to eat or drink alone is commonly regarded assad. Breaking bread or having a drink togetheris commonly thought to foster peace and understanding between people who mightotherwise be at odds. What all thisreveals is that the pleasures of food and drink are typically shared pleasures, and the more intensewhen they are shared. We take pleasurenot just in the meal, but in the fact that our family, friends, oracquaintances are taking pleasure in it too, and taking pleasure in it with us. Food and drink thereby reinforce social bonds, and all the goods thatfollow from having those bonds. A personwho, due to the vice of insensibility, is insufficiently drawn to such pleasuresis thereby going to be less fulfilled as a social animal – lonelier, moreself-centered, less able to contribute to or benefit from the social orders ofwhich he is a part.

Sexualpleasure too, when rightly ordered, is inherently social in nature insofar asit functions to bond the spouses together via the most intense sort of intimacyand affection. The vice of insensibilitymanifests itself in this context when, due either to priggishness or a colddisposition, one refuses sexual relations to one’s spouse, or participates inthem only grudgingly and unenthusiastically. The frumpish wife or boorish husband can contribute to an atmospherewherein this vice is likely to take root. When it does, sex is likely to become a source of marital tension ratherthan amity.

Temperance in sexual matters, specifically, isknown as the virtue of chastity, andit is a large topic of its own. Needlessto say, for Aquinas and Catholic moral theology, the fundamental principle hereis that sexual intercourse is virtuous only between a man and a woman married toone another, and when not carried out in a contraceptive manner. Within these constraints, there is much inthe way of lovemaking that is consistent with chastity. I have spelled out the details in my essay “InDefense of the Perverted Faculty Argument,” from my book Neo-Scholastic Essays. And I’ve said a lot more about sexualmorality in a number of other articles and blog posts, linksto which are collected here.

Whenaddressing matters of sexual morality, Thomist natural law theorists andCatholic moral theologians have much to say about the vice of intemperance inthis area. This is quite natural andproper, given the extreme sexual depravity that surrounds us today. Sins of excess related to matters of sex areby far the more common ones, and the ones modern people are most resistant tohearing criticism of. All the same, thisis only part of the story, because there is an opposite extreme vice too, evenif less common. Marital happiness, andthe good of the social order that depends on it, require avoiding that vice aswell.

June 28, 2023

Pilkington responds

Philip Pilkington sent me a responseto myreply to his American Postliberalarticle. I thank him for it and am happy to post it here:

Philip Pilkington sent me a responseto myreply to his American Postliberalarticle. I thank him for it and am happy to post it here:Feser'sresponse to my piece is a welcome effort at clarification. We need suchclarification if postliberalism and related thought is to move from theabstract to the concrete. Here I will address the key points, as best I can.

Regardingthe base versus superstructure distinction, we should probably better determinewhat we are talking about. When Marxists discuss them – typically in thebroader context of their ‘science’ of ‘dialectical materialism’ – they appearto be engaged in something in between metaphysics and political economy. AsFeser says, for them the economy truly determines all – and it does so on an apriori basis.

I wouldsuggest that, to the extent that postliberals choose to use this terminology,they completely abandon any a priori conceptions beyond the terminology itself.Base and superstructure should be seen as metaphors – rather loose metaphors inmany ways – to organise thinking on political and policy issues. Feser'sterminology of spheres is probably, as he says, less loaded. On the other hand,the base and superstructure terminology plugs into decades of political economydiscussion.

Moreimportantly is the question of cause. Here we truly descend into the realm ofthe practical. Yes, the norms that we may seek to set are groundedmetaphysically in the natural law tradition. But beyond this, everything isempirical. The problem, of course, is that social science cannot reallydetermine cause in any meaningful sense. The best that can be done is toestablish correlation – and, perhaps, in the best case correlation at a lag(econometricians call this ‘Granger causality’. In such questions, we are allHumeans whether we like it or not.

Feser hintsthat I may be emphasising economic causality over cultural in my initial essay –and I think he is correct. Some of this is rhetorical – I want to shakeconservatives into seeing these connections. But some of it is not. I doincreasingly think that many of the developments we are seeing in our cultureare being driven primarily by liberal economic relations being pushed past thepoint where they yield anything positive.

Take theexample of birth rates in Islamic countries that Feser references. It is nodoubt true that birth rates in Muslim countries are higher than inpost-Christian countries, but this is only true on a diminishing basis. ManyMuslim countries simply remain economically undeveloped. In these countries,people live for most part as they have for centuries. In the countries thathave made efforts in the direction of economic development – most notably Iran –birth rates have fallen precipitously.

In 1978,when the Iranian Revolution was launched, Iran's fertility rate was just above6.3. Recall, this was the fertility rate in an Iran run by the famously rathersecular Shah. Today, after years of economic modernisation, the fertility rateis well below replacement at 1.7. Recall, in contrast to the Shah's secularstate, this is Iran under the Mullahs – complete with its infamous moralitypolice. If we look at indicators of economic change, this starts to make sense.At the time of the Revolution less than 5% of Iranian women were enrolled intertiary schooling. Today this number is around 60%. Iran is a fascinating casestudy because it is a model in tension with itself. The revolutionaries wantedto modernise society but maintain an Islamic state. The results have been,shall we say, mixed.

But let usthink about this in positive terms. Imagine if we could run a successful familypolicy that pushed the fertility rate back up to around 3 (similar to whatexists in Israel today, but we would hope one more spread out and lessconcentrated amongst the Haredi). In such a society, the average family wouldhave three children and the state would be promoting this as something great.Could this possibly not drastically change the culture? It seems highly unlikelyto me that a nihilistic, hyperconsumer culture that we have today would fit insuch a society. People would simply not have time to be interested in suchfrivolities and much of it would be driven back underground, the province ofbohemians and oddballs.

On the otherhand, do we really think that a conservative cultural turn would vastly impactthese trends? We had a conservative revolution of sorts in the late-1970s. Andeven though the 1980s and 1990s were far more culturally conservative than the1960s and 1970s, none of the fundamental forces were reversed. Divorcecontinued to rise, family formation fell, birth rates fell – and so on. As withIran, the packaging can look as conservative as you please, but it matterslittle if people are not living it out.

A few yearsago I visited Croatia. On Sunday the churches were full. I expect that attendancerates were around 80-90%. All over the towns were spontaneous Catholic shrines.The air was thick with conservative sentiment. And yet, for all that, therewere few families. People were just sort of milling around aimlessly. While onthe beach I looked up the fertility rate on Google. It was 1.5.

June 27, 2023

Postliberalism, economics, and culture

I commend toyou economist Philip Pilkington’s fine essay “Towardsa Postliberal Political Economy,” at The American Postliberal. Itis in part a response to my recent PostliberalOrder article “InDefense of Culture War.” Itseems to me that we are essentially in agreement, and that for the most partthe essays complement rather than contradict one another. But there might be some differences overdetails, or at least of emphasis. Let’stake a look.

I commend toyou economist Philip Pilkington’s fine essay “Towardsa Postliberal Political Economy,” at The American Postliberal. Itis in part a response to my recent PostliberalOrder article “InDefense of Culture War.” Itseems to me that we are essentially in agreement, and that for the most partthe essays complement rather than contradict one another. But there might be some differences overdetails, or at least of emphasis. Let’stake a look.Liberalism and postliberalism

First, letme address a terminological matter that will not throw off readers who havebeen closely following the recent debate over postliberalism, but doessometimes confuse those who are not familiar with it. Pilkington frequently refers to the “liberalconservative” approach to cultural and economic issues. American readers who use the word “liberal” toconnote views of the kind associated with the Democratic Party are liable tomisunderstand him. They may find the phraseoxymoronic, or perhaps will suppose that Pilkington must be referring tosocially liberal Republicans or the like. But “liberal conservative” is not intended to refer to such people (ornot them alone, anyway), and the phrase is perfectly sensible when properlyunderstood.

In politicalphilosophy, the word “liberal” has a broader sense than it has in contemporaryAmerican politics. It refers to a broad traditionthat goes back to thinkers like John Locke, Adam Smith, and John Stuart Mill,and that has among its fundamental themes individualism, the thesis thatpolitical authority is the product of a social contract, and the principle thatthe state ought to be neutral between competing religious doctrines. Secondary themes would be an emphasis on themarket economy and limited government, though these are not per se liberal. (To be sure, doctrinaire or ideologicalversions of market economics and limited government are essentially liberal, but my point is that a non-liberal couldfavor non-doctrinaire or non-ideological policies of a free market or limitedgovernment sort.) In the twentiethcentury, thinkers like John Rawls took liberalism in a more egalitariandirection, and thinkers like Robert Nozick took it in a more radicallylibertarian direction. In the Americancontext, the word “liberalism” has come to be associated with egalitarian liberalismin particular. But in reality, that kindof liberalism is just one specieswithin a wider genus.

Now, manymodern conservatives are liberals in the broader sense in question. They are not egalitarian liberals and they are not libertarian liberals, but they are still liberals in the sense that they regard the work of thinkers likeLocke and Smith as foundational to a sound political philosophy, and more orless take for granted liberalism’s commitment to individualism, the idea ofpolitical authority as deriving from contract, and state neutrality on mattersof religion. This is especially true ofconservatives influenced by the “fusionism” of Frank Meyer, which came to beassociated with William F. Buckley’s NationalReview. Fusionism is essentially theidea that a commitment to individual liberty as understood in the Lockeantradition can and ought to be “fused” with a commitment to traditional moralityas enshrined in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

“Liberalconservatives” in this sense are, accordingly, as prone as libertarians are toargue for market-based approaches to social problems, and to see governmentaction as itself part of the problem rather than a possible solution. Accordingly, they deploy the rhetoric of“freedom” as often as, or even more often than, they appeal to tradition,family, or religion. That they would putEdmund Burke alongside Locke and Smith in their pantheon of early modernthinkers, and prefer F. A. Hayek to Nozick or Ayn Rand among contemporaryfree-marketers, is what makes their liberalism “conservative.” But, again, itis still a kind of liberalism in thebroad sense.

Now, the postliberal Right is defined by itsrejection of liberalism in this broad sense no less than in the narrow sense,and thus by its rejection of fusionism and any other attempt to marryconservatism to the liberalism of Locke, Smith, and Co. For postliberals, the paradigmatic politicalphilosophers are thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, Augustine and Aquinas. For theoretical articulation and defense ofthe foundations of political morality, they would look to Thomistic natural lawtheory (or something in that ballpark) rather than Lockean natural rightstheory. They take the family rather thanthe individual to be the basic unit of society, and regard the state as anatural institution rather than the product of a social contract. In addition, Catholic postliberals tendtoward the “integralist” position that it is preferable at least in theory forthe state to favor the Church rather than to remain neutral on matters ofreligion. (Whether it is better in practice, and exactly what it would looklike for the state to favor the Church, are complicated matters that Ihave addressed elsewhere.)

Naturally,the views of individual thinkers of either a liberal conservative sort or apostliberal sort are bound to be more complicated than this summaryindicates. A liberal conservative might countAristotle and Aquinas as influences too, and a postliberal might acknowledgethat there are insights to be drawn from a Burke or a Hayek. What I am describing here are the generaltendencies and basic commitments that differentiate the two points of view.

I wouldn’twant to put words in Pilkington’s mouth, and perhaps he would disagree with orqualify some of what I’ve said so far. But that is how I understand liberal conservatism and postliberalism,and I am supposing that that is more or less how he understands them too.

From culture to economics and backagain

In my ownessay, I discussed the famous Marxist distinction between the economic “base”of society and the political, legal, and cultural “superstructure” constructedon that base. The distinction providesthe organizing theme of Pilkington’s article, and he appeals to it in order tocharacterize the different approaches to economics and culture represented byMarxism, liberal conservatism, and postliberalism.

The Marxistposition, of course, is that the economic base determines everything else. Law, politics, and culture merely function tokeep in place the prevailing economic order and its ruling class, and have noother significance. By contrast, liberalconservatives, says Pilkington, take the economic and cultural spheres to beautonomous. They take the market economyto be a neutral wealth-generating mechanism that can and should be left toitself or at most tinkered with slightly so as to improve its output. They take the real action to be at the levelof culture, and they think that advancing their goals in that sphere is simplya matter of convincing people to adopt them by making good arguments (asopposed, say, to changing basic economic structures).

Postliberalism,says Pilkington, rejects both of these positions. Like Marxism and unlike liberal conservatism,it holds that economics influences culture. But, unlike Marxism, it holds that culture also influenceseconomics. Hence, like liberalconservatism and unlike Marxism, it rejects economic reductionism and takesculture and argumentation to enjoy some independence of economic factors. But it also rejects the liberal conservativeview of the economy as a neutral mechanism that should largely be leftalone. Securing cultural goals requires economicchange, and not just making good arguments. In short, economics and culture significantly affect one another, sothat policy cannot focus just on one to the exclusion of the other.

So far I warmlyagree with Pilkington, though there is a terminological difference between us,albeit one which is – probably – merelyterminological rather than substantive. Throughout his essay, Pilkington retains the Marxist jargon of economic“base” and cultural “superstructure.” Again, he rejects Marxism’s claims about their relationship, andemphasizes their mutual influence. Butto keep referring to economics as the “base” leaves the impression that it isstill somehow more fundamental. Iimagine that Pilkington does not intend this, and that he retains theterminology merely for ease of exposition. But I would prefer to speak of economic and cultural “spheres” (or somesuch term) rather than maintain the loaded terminology of “base” and“superstructure.”

On the otherhand, some of what Pilkington says might at least give some the impression thathe does indeed take economics to be fundamental. In particular, he discusses several examplesof phenomena that might at first glance appear to have purely cultural significance,but where, he argues, closer inspection will reveal underlying economicfactors. To be sure, his point may bemerely that economics and culture interpenetrate in these cases, without eitherbeing the more fundamental. And Isuspect that that is indeed his view. But it seems to me that even in the cases he discusses, the culturalfactors are indeed the more fundamental ones, even if he is right to note thatthere are crucial economic factors as well.

Hence,consider what Pilkington has to say about modern changes in familystructure. Liberal conservatives, hesays, attribute this mainly to moral decline, and in part to the welfarestate. But he notes that other crucialfactors are the dramatic decline in the birth rate and the entry of women intothe modern workforce. Pilkington emphasizesthat while women worked in earlier ages (for example, in agriculture) what is distinctiveabout modern women’s workplace is that it has separated work from home andfamily life. Now, these changes areeconomic in nature. Hence, it seems, wehave a clear case where economics has driven cultural change.

That is fairenough as far as it goes. But I’d pointout that the story doesn’t end there. For why have birth ratesdeclined, and why have women entered the modern work force in such largenumbers? The answer, in large part, hasto do with the legalization of birth control and the rise of modern feminism,with the political and legal changes that went along with it. And those factors, in turn, were the resultof cultural changes. Notice too that, despite the tremendousinfluence of Western capitalism on the rest of the world, the birth rate andthe economic situation of women has not changed nearly as radically in Muslimcountries. Why not? Because of legal, political, and culturalfactors. So, as I argued in my earlieressay, we see once again that lurking behind economic factors are deeper culturalpreconditions.

Somethingsimilar can be said even of the most seemingly crudely material offactors. For example, it is often claimedthat the birth control pill changed sexual mores more than all the propagandaof sexual revolutionaries could have. And the pill is a drug that directly affects body chemistry, not people’sideas. But the birth control pill didnot fall from the sky. It had to beinvented, produced, and marketed. Andits mere existence doesn’t force anyone to take it. Tobacco also still exists, but the number ofpeople using it has dramatically declined. Nor does the fact that tobacco poses health risks entirely explain that,because alcohol and marijuana also pose risks, yet alcohol use has not greatlydeclined, whereas marijuana use has increased.

The reason,of course, is that there has been vastly greater cultural pressure against tobacco use than against alcohol use, andalso cultural pressure in favor ofmarijuana use. And cultural pressuresare also responsible for the development and use of the pill. It was precisely because of changes in sexualattitudes that the pill was developed, marketed, and used in the first place,even if this in turn went on to accelerate the changes in sexualattitudes. Hence even the pill is not apurely material factor, nor indeed even primarily material in nature, allthings considered.

Pilkingtonalso argues that changes in economic policy can improve the health of thefamily, and that improving the health of the family will in turn bring aboutcultural changes. For example, “studiesshow that strong families tend to vote more conservative than atomisedindividuals.” Hence, he suggests, “itmay not be too much of an exaggeration to say, given how integrated personaland economic life are in today’s intensive consumption-production economy, theonly way to engage in meaningful reforms is to tackle them first at an economiclevel.”

But here toothe idea that economic policy is more basic than culture, or even equallybasic, collapses on closer inspection. For suppose we were to try to follow Pilkington’s advice and focus for atime just on the economic question of what sorts of policies would contributeto strengthening the family. What countsas “family”? And what counts as a“strong” family? Woke ideologues willhave answers to those questions, and they will be very different from theanswers a postliberal would give. Andthe difference in the answers will reflect different assumptions of a moral andphilosophical nature – in short, of a culturalnature. Yet again, lurking behindpurportedly purely economic considerations are deeper cultural issues.

Similarpoints can be made in response to Pilkington’s other examples. And then there is the fact that, no matterhow important some specific economic reform is, actually to achieve it willrequire political action, whichrequires changing minds. That, in turn, will require convincing acritical mass of people of the importance of such-and-such economic factorsrelative to other considerations. Andthat is an essentially philosophical task rather than an economic one.

Pilkingtonmay well agree with this. Indeed, asI have discussed elsewhere, Pilkington is well aware of the philosophicalassumptions that underlie economic lines of argument. Again, there may at the end of the day be lessof a substantive difference between our views than there is a difference ofemphasis, or perhaps at most of short-term strategy. And I certainly do not deny that economics isa crucial part of a complete postliberal program. But that is not because economics is morebasic than culture, or even because it is equally basic. It is because culture works in part through economics,and indeed because economics is itself a part of culture.

June 20, 2023

In defense of culture war

FromMarxists on the left to former House Speaker Paul Ryan on the right, manyvoices in the political discussion assure us that the “culture war” is a distractionand that what matter most are economic issues. But economic order has cultural prerequisites, and indeed economicphenomena themselves cannot even be conceptualized apart from cultural presuppositions. I make the case for the priority of cultureto economics in my essay “InDefense of Culture War,” which appears this week at

Postliberal Order

.

FromMarxists on the left to former House Speaker Paul Ryan on the right, manyvoices in the political discussion assure us that the “culture war” is a distractionand that what matter most are economic issues. But economic order has cultural prerequisites, and indeed economicphenomena themselves cannot even be conceptualized apart from cultural presuppositions. I make the case for the priority of cultureto economics in my essay “InDefense of Culture War,” which appears this week at

Postliberal Order

.

June 12, 2023

The associationist mindset

WhenAristotelian-Thomistic philosophers say that human beings are by naturerational animals, they don’t mean that human beings always reason logically(which, of course, is obviously not the case). They mean that human beings by nature have the capacity for reason, unlike other animals. Whether they exercise that capacity well isanother question. Human beings are oftenirrational, but you have to have the capacity for reason to be irrational. A dog or a tree doesn’t even rise to the levelof irrationality. They are non-rational, not irrational.

WhenAristotelian-Thomistic philosophers say that human beings are by naturerational animals, they don’t mean that human beings always reason logically(which, of course, is obviously not the case). They mean that human beings by nature have the capacity for reason, unlike other animals. Whether they exercise that capacity well isanother question. Human beings are oftenirrational, but you have to have the capacity for reason to be irrational. A dog or a tree doesn’t even rise to the levelof irrationality. They are non-rational, not irrational.Rationality,on the Aristotelian-Thomistic account, involves three basic capacities: tograsp abstract concepts (such as the concept of being a man or the concept of beingmortal); to put concepts together into complete thoughts or propositions(such as the proposition that all men aremortal); and to reason logically from one proposition to another (as whenwe reason from the premises that all menare mortal and that Socrates is a manto the conclusion that Socrates is mortal). Logic studies the ways concepts can becombined into propositions and the ways propositions can be combined intoinferences. Deductive logic studies,specifically, inferences in which the conclusion is said to follow from thepremises of necessity; and inductive logic studies inferences in which it issaid to follow with probability.

Any adequatephilosophical or psychological theory of the human mind has to be consistentwith our possession of these capacities. Many such theories fail this test, but might accurately describe somenon-human creatures. For example,Skinnerian behaviorism is hopeless as a theory of human nature, and isn’t evenplausible as a description of many of the higher animals. But asDaniel Dennett suggests, it might be true of simple invertebrateslike sea slugs. (It is also possible fora theory to do justice to our rational capacities, but still fail in some otherrespect accurately to describe human nature. For example, Cartesian dualism does so insofar as it wrongly takes the humanintellect to be a complete substance in its own right stocked with innate ideas. But this is at least an approximation of whatangelic minds are like.)

Then thereare theories which get the human mind wrong, but nevertheless afford an approximatedescription of what a certain kind of disorderedthinking is like. Consider the disputebetween voluntarism and intellectualism. For the intellectualist, the intellect is prior to the will in the sensethat the will is of its nature always directed at what the intellect judges tobe good. Voluntarism, which comes indifferent forms, seriously modifies or denies this claim. Like other Thomists,I take intellectualism to be the correct view. But asI have argued elsewhere, with a certain kind of irrationality it is as if the person’s will floated free ofhis intellect. (I’ve labeled this “thevoluntarist personality.”)

Anotherexample, I want to suggest here, is afforded by associationism. Associationisttheories attempt to account for all transitions from one mental state toanother by reference to causal connections established via experience. For example, David Hume famously positedthree principles of association: resemblance,contiguity in time or space, and cause and effect. Resemblance has to do with how one idea mighttrigger another because of some similarity between the things represented bythe ideas. For instance, seeing anorange might cause you to think of a basketball because they are similar inshape and color; smelling the marijuana smoke wafting from a nearby apartmentmight call to mind a skunk because the odor is similar; and so on. Examples involving contiguity in time orspace would be the way that thinking about World War II might bring to mind thesound of swing music (since it was popular at the time of the war), or the waythat seeing the White House might generate an image of the Washington Monument,since they are in the same city. Examples involving cause and effect would be the sight of a puddle onthe ground triggering the thought of rain (since that is often a puddle’scause) and the thought of a gun generating a mental image of a dead man (sincethat is often a gun’s effect).

Notice thatall of these relations are sub-rational. Suppose that, by way of the operation ofHume’s three principles, some particular person somehow developed a strongtendency to have the thought that it’sraining in Cleveland every time it occurred to him that it is now five o’clock just as heremembered that Charles is the currentking of England. Obviously, thatwould not entail the validity of the following argument:

It is now five o’clock

Charles is the current king of England

Therefore,it’s raining in Cleveland

That is tosay, the causal relations by whichone thought might come to generate another are not the same thing as the logical relations by which oneproposition might entail another. As aresult, associationist theories, even if they might provide plausible accountsof the mental processes of some non-human animals, simply cannot account forthe rational powers that set human beings apart from other animals. For the causal relations they posit do notsuffice to guarantee that the right logicalrelations will hold between the thoughts governed by those causal relations.

This is alongstanding problem for associationist theories. In contemporary philosophy of mind, cognitivescience, and artificial intelligence research, the most influential variationon associationism is known as connectionismor the “neural network” approach. It hasbeen vigorously criticized by thinkers like Jerry Fodor and Zenon Pylyshyn forits inability to account for the rationality of thought. What connectionist models (and the AI builton them) are good at is patternrecognition. But sensitivity topatterns is not the same thing as a grasp of the logical relationships betweenconcepts and propositions. If all we didwas pattern recognition, we would not be capable of the valid inferences thatwe carry out all the time.

Likevoluntarism, though, associationism is not a bad approximate description ofcertain disordered habits of thinking. For many people’s minds seem to operate as if they were governed by purelyassociationist principles. Inparticular, those chronically prone to fallacious reasoning are like this. For many logical fallacies involve a kind ofjumping to conclusions on the basis of an association between ideas that seems tight but is in fact too weak to grounda deductively valid or even inductively strong inference.

The mostobvious example involves a fallacy that happens to go by the name of “guilt byassociation.” Suppose someone reasons asfollows: “Chesterton criticized capitalism, and communists criticizecapitalism, so Chesterton must have been a communist.” The premises are true but the conclusion isfalse. The speaker is assuming thatbecause communism is associated with criticism of capitalism and Chesterton isassociated with criticism of capitalism, it is reasonable to associateChesterton with communism. The reasonthis is fallacious, of course, is that though all communists are critics ofcapitalism, the converse is not true – not all critics of capitalism arecommunists.

Sometimeswhen people commit this fallacy, they give it up immediately once it is pointedout to them. That is a good indicationthat the psychological source of the error is simply that they made theinference too quickly or inattentively, nothing more. But sometimes people are very reluctant togive up such an argument even after the error is explained to them. For example, suppose someone argues: “Racistsare opposed to illegal immigration and you are opposed to it, so you must be aracist.” The fallacy here is exactly thesame. Even if all racists are opposed toillegal immigration, the converse is not true, so the conclusion does notfollow. But people can be very reluctantto give up this argument even though it is a straightforward case of thefallacy of guilt by association. That isan indication that there is more going on here than merely too hasty aninference.

I’d proposethat an additional factor is a further association in the speaker’s mind. It’s not just that the speaker associates theidea of opposition to illegalimmigration with the idea ofracism. There are, in addition, strong emotional associations at work. The speaker has a strongly negative emotional reaction to opposition toillegal immigration, and one that is similar to the strongly negative emotionalreaction he has to racism. Hence eventhough there isn’t the needed logical connection to make the inference frompremise to conclusion valid, the emotionalconnection between the ideas makes it hard for the speaker to give up theconclusion that you must be a racist. Thisassociation is merely psychologicalrather than logical, so the inference remains fallacious, but the strength ofthe association makes it nevertheless difficult for the speaker to see that.

Otherfallacies too involve jumping to conclusions on the basis of an associationthat seems logical but is in fact merely psychological, rendering the inferencefallacious but easy to fall into. Consider the “straw man” fallacy, wherein the speaker attacks acaricature of his opponent’s position rather than anything the opponent has actuallysaid. For instance, suppose you express theview that the Covid lockdowns did no net good but caused grave economic andpsychological harm, and in response someone accuses you of being a libertarianwho puts individual freedom ahead of the lives of others. The speaker is misrepresenting your position,making it sound as if your view is that even though the lockdowns saved lives,your right to do what you want trumps that. But that is not what you said. What you said is that they did not save lives and in addition causedgrave harm, and you made no appeal to any libertarian premises.

Here too itis psychological associations rather than logical connections that account forthe error. The speaker associatesopposition to lockdowns with libertarianism (perhaps on the basis of a furtherfallacy of guilt by association, or because the lockdown critics he’s dealtwith before happen to have been libertarians, or for some other reason). The one idea simply happens to trigger the other one in his mind, andthus he supposes that you must be a libertarian and attacks the straw man. The causalconnection between the ideas makes the inference quite natural for him, but itdoes not make it logical.

Yet other fallaciesare plausibly generated by such associationist psychological mechanisms. Take the “circumstantial ad hominem” fallacy, also known as the fallacy of appeal tomotive. This involves rejecting a claimor argument merely on the basis of some suspect motive attributed (whethercorrectly or incorrectly) to the person advocating it. For example, suppose some writer gives anargument to the effect that cutting taxes would promote economic growth, andyou dismiss it on the grounds that it reflects mere self-interest on his part,or because the writer works for a think tank which is known for advocating suchpolicies. The problem with this is thatwhether the argument is sound or not is completely independent of the motivesof the person giving it. A person withbad motives can give a good argument and a person with good motives can give abad argument.

However,motives are not alwaysirrelevant. For example, they areimportant when evaluating the reliability of testimony or expert advice. If the sole witness in a murder trial isindependently known to be hostile to the suspect, then that gives at least somereason to doubt his testimony implicating the suspect. If a salesman assures you that the product hesells is the best on the market, the fact that he has a motive to sell it toyou gives you reason to doubt him despite his expertise regarding products ofthat kind.

In a fallacyof appeal to motive, what no doubt often happens is that, on the basis ofexamples like these, the person committing the fallacy forms a psychologicalassociation between having a suspectmotive and being untrustworthy. Then, when he encounters an argument given bysomeone he suspects of having a bad motive, he goes on to associate being untrustworthy not just with theperson in question but with the argumentthe person gives. But again, thesoundness or otherwise of an argument is independent of the character of theperson who gives it, so that this transference is fallacious. Once again, the causal connection between theideas makes an inference seem natural, despite it’s not actually being logical.

There areyet other kinds of irrationality that can plausibly be said to reflectassociationist psychological mechanisms. ElsewhereI’ve argued that “wokeness” can be characterized as “a paranoid delusionalhyper-egalitarian mindset that tends to see oppression and injustice where theydo not exist or greatly to exaggerate them where they do exist.” An example would be the way that mild or evenentirely innocuous language in some vague way related to race is frequentlyshrilly denounced by wokesters as “racist.” For example, the well-known market chain Trader Joe’s sells a Mexican beerlabeled “Trader Jose’s,” and Chinese food products labeled “Trader Ming’s.” To any sane mind, there is nothing remotelyobjectionable about this. In particular,there is nothing in these labels that entails the slightest degree of hostilitytoward Mexican or Chinese people. Butthe woke mind is not sane, and, unsurprisingly, therewas a call a few years back to drop these labels (which, wisely, the chaindecided to ignore).

What seemsto be going on is that in the mind of the wokester, labels like these triggerthe idea of race, which in turntriggers the idea of racism, and thestrongly negative emotional associations of the latter in turn set up asimilarly negative emotional association with the labels. There is no logical connection at all, but the strength of the psychologicalassociations makes the fallacious inference seem natural. The woke mind is analogous to an overlysensitive smoke alarm, which blares out its obnoxious warning any time someonemerely breathes too hard. (In the articlelinked to, I discuss some of the disordered psychological tendencies which leadto the formation of such bogus associations.)

Anotherexample of fallaciously associationist thinking would be the construction of fanciful“narratives” that seem to lend plausibility to dubious conspiracy theories ofboth left-wing and right-wing kinds. I’veelaborated on this elsewhere and so direct interested readers to thatearlier discussion.

Naturally,since they are human beings, even people who exhibit what I am calling “theassociationist mindset” do in fact possess rationality, which is why they cancome to see their errors. Their mindsare not in fact correctly described by associationist psychologicaltheories. But reason is so weak in themand the mechanisms in question so strong that they can often behave as if these theories were true ofthem. They seem to be disproportionatelyrepresented in social media contexts like Twitter. And in fact such social media seem to fosterassociationist habits of thought, inways I’ve discussed before.

June 2, 2023

Reconsidering corporal punishment

Debatesabout crime and punishment today typically concern disagreements about thedeath penalty, or about the length, and in some cases the appropriateness, ofprison sentences. Largely neglected isthe topic of corporal punishment – the infliction of bodily pain as a penaltyfor an offense. No doubt many willregard the very idea as a relic of a less enlightened age. But that is not a view shared universally. And the practice made headlines in the Westwithin living memory, when, in 1994, the American teenager Michael Fay wascaned in Singapore for vandalism (specifically, for stealing road signs anddamaging a number of cars).

Debatesabout crime and punishment today typically concern disagreements about thedeath penalty, or about the length, and in some cases the appropriateness, ofprison sentences. Largely neglected isthe topic of corporal punishment – the infliction of bodily pain as a penaltyfor an offense. No doubt many willregard the very idea as a relic of a less enlightened age. But that is not a view shared universally. And the practice made headlines in the Westwithin living memory, when, in 1994, the American teenager Michael Fay wascaned in Singapore for vandalism (specifically, for stealing road signs anddamaging a number of cars).Vandalismmuch more grave than the kind Fay was punished for has become rife in Westerncountries in recent years. The riots ofthe summer of 2020 saw widespread defacement and pulling down of statues andother monuments. The riot of January 6,2021 saw the U.S. Capitol vandalized. Environmentalistsfrequently deface or glue themselves to works of art, or block traffic bysitting in major roadways and refusing to move. That the physical damage caused by such acts is often worse than thesort of thing Fay was punished for is bad enough. But these acts are worse in another way. Fay’s actions were mere obnoxious hijinks ofthe kind boys are sometimes prone to. The political vandalism of recent years is much more sinister, being anassault on the social order itself and on works of art that are the heritage ofthe human race.

If relativelymilder vandalism of the kind Fay was caned for can merit corporal punishment –and I would argue that it can – then the political vandalism of recent yearscan hardly merit less. It might seem anextreme way to deal with the current problem. But the current problem is itself extreme, and calls for a proportionateremedy.

To see whythis is a remedy worthy of consideration, let’s consider the natural law moraljustification of the use of corporal punishment, and also what the tradition ofthe Church has to say about it. Beforedoing so, however, we need to put aside a potential red herring.

Not the same thing as torture

In thedecade or so after 9/11, a rather nasty debate arose in Catholic circles abouttorture. Surprisingly, few seemed ableor willing to define it, including those who were extremely confident in theirpronouncements about its moral status. My own view is that the most plausible definition is along the linesendorsed at the time by Thomists like James Chastek, who definedtorture as “the use of physical pain to break the will of another”(though I’d alter this to note that the pain could also be psychological innature).