Edward Feser's Blog, page 14

November 18, 2023

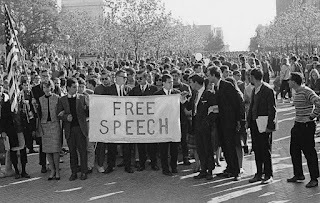

What is free speech for?

In a new articleat Postliberal Order, I discussthe teleological foundations of, and limitations on, the right to free speech,as these are understood from the perspective of traditional natural law theory’sapproach to questions about natural rights.

In a new articleat Postliberal Order, I discussthe teleological foundations of, and limitations on, the right to free speech,as these are understood from the perspective of traditional natural law theory’sapproach to questions about natural rights.

November 9, 2023

All One in Christ at Public Discourse

At Public Discourse, John F. Doherty kindly reviews mybook

AllOne in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

. From the review:

At Public Discourse, John F. Doherty kindly reviews mybook

AllOne in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

. From the review:In Feser’s book, Catholics, otherChristians, and even non-Christians will find much to help them confront CRTand the perennial challenges of living in a racially diverse society…

Critical race theorists routinely useconfusing, tough-to-pin-down logical fallacies. Feser does us the service of laying thesefallacies out methodically and succinctly…

For anyone who knows nothing aboutCRT, All One inChrist is an excellent place to start. It has a decidedly negative perspective on themovement, but Feser takes pains to be fair to his opponents.

November 4, 2023

The Thomist's middle ground in natural theology

TheAristotelian-Thomistic tradition holds that knowledge must begin with sensoryexperience but that it can nevertheless go well beyond anything that experiencecould directly reveal. Its empiricism isof a moderate kind consistent with the high ambitions of traditional metaphysics. For example, beginning a posteriori with the fact that change occurs, it claims to be ableto demonstrate the existence of a divine Prime Unmoved Mover. Similarly demonstrable, it maintains, are theimmateriality and immortality of the soul.

TheAristotelian-Thomistic tradition holds that knowledge must begin with sensoryexperience but that it can nevertheless go well beyond anything that experiencecould directly reveal. Its empiricism isof a moderate kind consistent with the high ambitions of traditional metaphysics. For example, beginning a posteriori with the fact that change occurs, it claims to be ableto demonstrate the existence of a divine Prime Unmoved Mover. Similarly demonstrable, it maintains, are theimmateriality and immortality of the soul.Two crucialcomponents of this picture of human knowledge are the theses that concepts areirreducible to sensations and mental images, but can nevertheless be abstractedfrom imagery by the intellect. As I havediscussed before,a key difference between the Aristotelian-Thomistic position on the one handand early modern forms of rationalism and empiricism on the other is that eachof the latter kept one of these Aristotelian-Thomistic theses while rejectingthe other. Rationalism maintained thethesis that concepts are irreducible to sensations and mental images, butconcluded that many or all concepts therefore could not in any way be derivedfrom them. Hence, rationalistsconcluded, many or all concepts must be innate. Modern empiricism held on to the thesis that concepts derive from mentalimagery, but concluded that they must not really be distinct from them. Hence the modern empiricist tendency toward “imagism,”the view that a concept just is an image (or an image together with a generalterm).

Thesefateful moves are key to understanding the later trajectories of therationalist and empiricist traditions. Thenotion of innate ideas gave rationalism confidence that it had the conceptual andepistemic wherewithal to ground an ambitious metaphysics. But rationalist metaphysical systems can beso bizarre and revisionary that they are open to the objection that their lackof an empirical foundation leads them to float free of objective reality. Modern empiricism, by contrast, has usuallybeen much more metaphysically modest. But it has also had a tendency to be toomodest, to the point of collapsing into skepticism even about the world ofcommon sense and ordinary experience. Here the critic can charge that collapsing concepts into imagery hasprevented modern empiricism from being able to account for any knowledge beyondthe here and now.

Now, bothapproaches can be and have been modified by various thinkers in ways that seekto avoid problems like those mentioned – though from the Thomistic point ofview, only a return to the broadly Aristotelian conception of knowledge fromwhich they each in their own ways departed can afford a sure remedy.

But general epistemologyis not my concern here. What I want todo instead is note two general approaches to natural theology that mightloosely be labeled “rationalist” and “empiricist,” even if their practitionersdon’t necessarily all self-identify as such. They are approaches that are, from the Thomist point of view, deficientin something analogous to the ways in which rationalist and modern empiricistepistemology and metaphysics in general are deficient. And like those views, they represent oppositevicious extremes between which, naturally, Thomism stands as the sober middleground.

On the onehand we have an approach that aims to establish admirably ambitious traditionalmetaphysical conclusions – such as the existence of God and the immortality ofthe soul – by way of an essentially rationalist methodology. One example would be Plantinga’sontological argument for God’s existence, and another would be Swinburne’s conceivabilityargument for dualism. Plantinga’sargument proceeds by considering what might or must be the case in variouspossible worlds, and on that basis aims to establish the existence of God inthe actual world. Swinburne’s argumentbegins with what we can conceive about the mind, and draws the conclusion thatits essence or nature must be of an immaterial kind.

From theAristotelian-Thomistic point of view, both these arguments get things preciselybackwards. We don’t start withpossibilities and then reason from them to actualities. Rather, we start with actual things,determine their essences, and then from there deduce what is or is not possiblefor them. We don’t start with what wecan conceive and then determine a thing’s essence from that. Rather, we start with a knowledge of itsessence and then determine, from that, what is actually conceivable withrespect to it, and what merely falsely seemsto be conceivable.

From theThomist point of view, while the metaphysical conclusions of such arguments are not too ambitious, the method for arriving at them is. We cannot do so entirely a priori. To be sure, oncewe do establish the existence of God (through arguments of the kind I’vedefended at length elsewhere),we discover that he is such that, were we fully to know his essence, we wouldsee that his existence follows from it of necessity, just as the ontologicalargument claims. But what we can’t do isjump directly to such an argument as a standalone proof of his existence. Similarly, when we first establish that theintellect is by nature immaterial, we will see that it is indeed conceivablefor it to exist independently of the body (topics I’ve dealt with e.g. hereand here). But in that case the appeal to conceivabilityis rendered otiose as grounds for establishing the intellect’s immateriality.

On the otherhand, we have arguments that proceed aposteriori, but are way too unambitiousin their conclusions. This wouldinclude, for example, arguments that treat God’s existence as at best the mostprobable “hypothesis”among others that might account for such-and-such empirical evidence, or evenfail to get to God, strictly speaking, as opposed to a “designer” of somepossibly finite sort. And it wouldinclude arguments for survival of death that put the primary emphasis on out-of-bodyexperiences and other phenomena that can at best render a probabilistic judgment.

Thomiststend to put little or no stock in such “god of the gaps” and “soul of the gaps”arguments. At best they are distractionsfrom the more powerful arguments of traditional metaphysics, and thus can makethe grounds for natural theology seem weaker than they really are. At worst, they can promote seriousmisunderstandings of the nature of the soul, of God, and of his relationship tothe world. (For example, they can givethe impression that it is at least possible in principle that the world mightexist without God, which entails deism at best rather than theism. And they can give the impression that the disembodiedsoul is a kind of spatially located or even ghost-like thing.)

For the Thomist,the correct middle ground position is to hold that the soul’s immateriality andimmortality, and the existence and nature of God as understood within classicaltheism, can all be demonstrated viacompelling philosophical arguments, but that the epistemology underlying thesearguments is of the Aristotelian rather than rationalist sort. (Again, I defend such arguments for theexistence and nature of God in FiveProofs of the Existence of God, and have argued for the immaterialityand immortality of the soul hereand here. Muchmore on the latter topics to come in the book on the soul that I am currentlyworking on.)

Related reading:

Therationalist/empiricist false choice

IsGod’s existence a “hypothesis”?

October 24, 2023

Cartwright on reductionism in science

In hersuperb recent book

APhilosopher Looks at Science

, Nancy Cartwright revisits some ofthe longstanding themes of her work in the philosophy of science. In anearlier post, I discussed what she has to say in the first chapterabout theory and experiment. Let’s looknow at what she says in her second chapter about reductionism, of which she haslong been critical.

In hersuperb recent book

APhilosopher Looks at Science

, Nancy Cartwright revisits some ofthe longstanding themes of her work in the philosophy of science. In anearlier post, I discussed what she has to say in the first chapterabout theory and experiment. Let’s looknow at what she says in her second chapter about reductionism, of which she haslong been critical. Reductionismdoes not have quite the same hold in philosophy of science that it once did, havingbeen subjected to powerful attack not only from Cartwright, but from PaulFeyerabend, JohnDupré, and many others. (Idiscuss the anti-reductionist literature in detail in Aristotle’sRevenge.) Still, the ideathat whatever is real is somehow ultimately nothing more than what can inprinciple be described in the language of a completed physics exerts a powerfulhold on many. Cartwright cites JamesLadyman and Don Ross as adherents of this view, and AlexRosenberg is another prominent advocate. As Cartwright notes, in contemporary writingabout science, the lure of reductionism is especially evident in discussions ofthe purported implications of neuroscience for topics like free will.

Cartwrightsets the stage for her discussion by quoting a famous passage from physicistSir Arthur Eddington’s book TheNature of the Physical World:

I have settled down to the task ofwriting these lectures and have drawn up my chairs to my two tables. Two tables! Yes; there are duplicates of every object about me – two tables, twochairs, two pens…

One of them has been familiar to mefrom earliest years. It is a commonplaceobject of that environment which I call the world. How shall I describe it? It has extension; it is comparativelypermanent; it is coloured; above all it is substantial… [I]f you are a plain commonsense man, not toomuch worried with scientific scruples, you will be confident that youunderstand the nature of an ordinary table…

Table No. 2 is my scientific table…It does not belong to the world previously mentioned – that world whichspontaneously appears around me when I open my eyes... My scientific table ismostly emptiness. Sparsely scattered inthat emptiness are numerous electric charges rushing about with great speed;but their combined bulk amounts to less than a billionth of the bulk of thetable itself…

There is nothing substantial about my second table. It isnearly all empty space – space pervaded, it is true, by fields of force, butthese are assigned to the category of “influences”, not of “things”. (pp.xi-xiii)

Now, reductionismholds that in some sense the first table is really “nothing but” the secondtable – or even that the first table does not, strictly speaking, really existat all, and that only the second table does (though philosophers typicallycharacterize the latter sort of view as eliminativist rather thanreductionist).

Reduced reductionism

The firstconsideration Cartwright raises to illustrate how problematic reductionism isconcerns the way reductionists have, over the last few decades, repeatedly hadto qualify their claims. The ambitionsof reductionism have, you might say, been greatly reduced. Bold type-typereductionism gave way first to a weaker token-tokenreductionism, and then to yet weaker superveniencetheories.

Type-typereductionist theories hold that each typeof feature described at some higher-level science can be identified with some type of feature described at alower-level science, and ultimately at the level of physics. Perhaps the best-known theory of this kind isthe original mind-brain identity theory,which holds that every type of psychological state (the belief that it israining, the belief that it is sunny, the desire for a cheeseburger, the fearthat the stock market will crash, etc.) can be identified with some specifictype of brain process. A stock examplefrom the physical sciences would be the claim that temperature is identical tomean kinetic energy.

AsCartwright notes, one problem with this sort of view is that it is difficult tofind plausible cases of successful type-type reductions beyond such stockexamples. Another is that the stockexamples themselves are not in fact unproblematic. “Reduction” claims seem really to be eliminativistclaims after all. For example, given theso-called reduction of temperature, it’s not that what we’ve always understoodto be temperature is really just mean kinetic energy. It’s that what we’ve always understood to betemperature is not real after all (or exists only as a quale of our experienceof the physical world, rather than something there in the physical worlditself) and all that really exists is mean kinetic energy instead.

A problemwith supposing otherwise is that the laws that govern the features of somehigher-level description and the laws that govern the features of some allegedlycorresponding lower-level description can yield conflicting predictions. One way to think about this – though notCartwright’s own example – is in terms of DonaldDavidson’s view that descriptions at the psychological level are notlaw-governed in the way that the materialist supposes that descriptions at theneurological level are. Hence, even if abrain event of a certain type is strictly predictable, the corresponding mentalevent will not be. Given this sort ofmismatch, there is pressure on the type-type reductionist to treat thehigher-level description as not strictly true.

Anespecially influential consideration that led philosophers to abandon type-typereductionism is the “multiple realizability” problem – the fact thathigher-level features can be “realized in” more than one type of lower-levelfeature, so that there is no smooth mapping of higher-level types on tolower-level types of the kind an ambitious reductionist project aims for. In the case of the mind-brain identitytheory, the problem is that the same mental state (believing that it israining, say) could plausibly be associated with different types of brainprocess in different people, or even in the same person at differenttimes. Or consider how an economicproperty like being one dollar can berealized in paper currency, in metal currency, or as an electronic record ofone’s bank account balance.

This ledphilosophers to embrace less ambitious token-tokenreductionist theories. The idea here isthat even if types of feature at ahigher level cannot be smoothly correlated with types of feature at a lower level, nevertheless every token or individual instance of a featureat the higher level can be identified with some token or individual instance ofa lower-level feature. For example, this particular instance of believing that it’s raining is identicalwith that particular instance of acertain type of brain process.

AsCartwright notes, however, token reductions in fact tend to yield, after all, typereduction claims of a sort. An examplewould involve disjunctive types atthe lower level of description. Forinstance, a token reductionist view of mind-brain relations may entail that atype of mental state like believing thatit is raining is identical to a “type” of neural property defined as being in brain state of type B1 OR being inbrain state of type B2 OR being in brain state of type B3 OR… And this will, in turn, open up thepossibility of a conflict between what the laws that govern the higher-leveldescription entail and what the laws that govern the lower-level descriptionentail.

If it isobjected that disjunctive “types” of the kind just described seem artificial, thatis certainly plausible. But the problem,as Cartwright notes, is that this illustrates how identifying what counts as aplausible type is going to require detailed metaphysical analysis, and cannotbe read off the science, as the reductionist supposes.

In anyevent, token-token reductionism gave way in turn to talk of supervenience. The basic idea here is that phenomena at somehigher level of description A superveneon phenomena at some lower level of description B just in case there could not be any difference at what happens atlevel A without some correspondingdifference in what happens at level B.

But exactlywhat this amounts to is not obvious, and debating the meaning of superveniencehas, Cartwright complains, been a bigger concern of philosophers thanexplaining exactly why anyone should believe in it in the first place. (More on this in a moment.) As its vagueness indicates, supervenience entailsan even weaker claim than token-token reduction. Though, in recent years, there has been a lotof heavy going about “grounding,” which, Cartwright notes, is stronger thansupervenience. The idea is that allfacts are “grounded” in the facts described at the level of physics, in thesense that whatever happens at the higher levels is “due to” what happens atthe lower, physics level. But here too, why suppose this is the case?

Groundless grounding

Where theclaim that everything supervenes on the level described by physics isconcerned, Cartwright says, there are three basic reasons given for it, none ofthem well worked out or convincing. First, there is a leap from the fact that the lower-level featuresdescribed by physics affect whathappens at the higher levels, to the conclusion that those features by themselvesentirely fix what happens at thehigher levels. This is simply a non sequitur.

Second,there is a leap from the supposition that successful reductions have beencarried out in a handful of cases, tothe conclusion that reductionism is ingeneral true. But this too is a non sequitur (and on top of that, thepremise is questionable). Third, thereis the claim that physicalistic reductionism is in fact the method appliedwithin science. But this, Cartwrightargues, is simply not true to the facts of actual scientific practice.

“Grounding”accounts of reduction suppose that the level described by physics is the sole cause of what happens at the higherlevels, and also that it is in no way itself caused by what happens at thehigher levels. These claims too, arguesCartwright, are not supported by actual scientific practice.

Here sheappeals in part to recent work in the philosophy of chemistry, in which twogeneral lines of anti-reductionist argument have been developed. The first and more ambitious of them arguesthat chemistry as a discipline rests on classificatory and methodologicalassumptions that are simply sui generisand make the features of the world it uncovers irreducible to those uncoveredby physics. The second does not rule outreductions a priori, but argues on acase by case basis that purported reductions have not in fact successfully beencarried out. (I discuss this work inphilosophy of chemistry at pp. 330-40 of Aristotle’sRevenge.)

But it isnot just that chemistry and other higher-level sciences are not in fact “allphysics” at the end of the day. AsCartwright emphasizes, “even physics isn’t all physics.” For one thing, “physics” covers a range ofbranches, theories, and practices, not all of which have been reduced to the mostfundamental theories. For another, eventhe fundamental theories themselves are not fully compatible with each other,the notorious inconsistency between quantum mechanics and the general theory ofrelativity being a longstanding and still unresolved problem. She adds:

The third and to me most importantpoint is that in real science about real systems in the real world, forpredictions and explanations of even the purest of physics results, physicsmust work in cooperation with a motley assembly of other knowledge, from othersciences, engineering, economics, and practical life. (p. 110)

Cartwrightthen goes on to describe in detail the Stanford Gravity Probe Bproject as an illustration of the vast quantity of theoretical knowledge andpractical know-how that are necessary in order to apply and test abstract physicaltheory, yet cannot itself be reduced to such theory. This recapitulates a longtime theme inCartwright’s work over the decades, viz. that the mathematical models and lawsof physics are idealized and simplified abstractionsfrom concrete physical reality, and do not themselves constitute or captureconcrete physical reality.

In short,reductionism, Cartwright judges, is poorly defined and poorly argued for. Its lingering prestige is unearned.

I’ve mainlyjust summarized Cartwright’s arguments here, since I sympathize with them andthey supplement those that I develop in Aristotle’sRevenge. They give us, though, onlyher case against the views sheopposes, rather than the positive account she’d put in place of them, which isdescribed later in the book. More onthat in a later post.

Relatedreading:

Dupréon the ideologizing of science

Scientism:America’s State Religion

October 12, 2023

Thomism and the Nouvelle Théologie

My review of Jon Kirwan and Matthew Minerd’s important new anthology

TheThomistic Response to the Nouvelle Théologie

appears in the November 2023 issue of First Things.

My review of Jon Kirwan and Matthew Minerd’s important new anthology

TheThomistic Response to the Nouvelle Théologie

appears in the November 2023 issue of First Things.

October 10, 2023

A little logic is a dangerous thing

Some famousand lovely lines from Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” observe:

Some famousand lovely lines from Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” observe:A little learning is a dangerous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring.

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Think of theperson who has read one book on a subject and suddenly thinks he knowseverything. Or the beginning student ofphilosophy whose superficial encounter with skeptical arguments leads him todeny that we can know anything. A deeperinquiry, if only it were pursued, would in each case yield a more balancedjudgement.

Similardelusions of competence often afflict those who have studied a littlelogic. ElsewhereI’ve discussed the phony rigor often associated with the application of formalmethods. Here, however, what I have inmind is the abuse of a more elementary part of logic – the study of fallacies(that is to say, of common errors in reasoning).

The principle of charity

Beginningstudents of logic, when they first learn the fallacies, often start thinkingthey can see them everywhere – or more precisely, everywhere in the argumentsof people whose opinions on politics or religion they already disagree with,though not so much in the arguments of people on their own side. (What are the odds?) A good teacher will inform them thatknowledge of the fallacies must be applied in conjunction with what is calledthe “principle of charity.” Thisprinciple tells us that, when an argument that could be read as committing a fallacy could also be plausiblyinterpreted instead in a different way, we should presume that the latter interpretationis the correct one.

The point ofthis principle is not merely, or even primarily, to be nice. The point is rather that the study of logicis ultimately about pursuing truth,not about winning a debate. If wedismiss some argument too quickly because we haven’t considered a more charitableinterpretation, then we might miss out on learning some important truth –perhaps a truth that we are reluctant to learn, precisely because it comes fromsomeone we dislike.

But it’s notjust a failure to apply the principle of charity that can lead someone wronglyto accuse another of committing a fallacy. Sometimes people just don’t correctly understand the nature of someparticular fallacy.

Ad hominem?

Let’sconsider some common examples, beginning with the ad hominem fallacy. Whatmatters when evaluating an argument is whether its premises are true, andwhether the conclusion really follows from the premises, either with deductivevalidity or at least with significant probability. And that’s all that matters, logically speaking. The character of the person giving theargument is entirely irrelevant to that. Ad hominem fallacies arefallacies that neglect this fact – that pretend that by attacking a person insome way, you’ve thereby cast doubt on the argument the person has given or thetruth of some claim he has made.

There aredifferent ways this might go. Thecrudest way is the abusive ad hominem,wherein, instead of addressing the merits of some argument the person hasgiven, you simply call him names – “racist,” “fascist,” “commie,” or whatever –and pretend that sticking such a label on him casts doubt on what he said. Another common variation on the ad hominem fallacy is the circumstantial ad hominem or appeal to motive, wherein one attributesa suspect motive to the person and pretends that doing so casts doubt on whatthe person says. Of course, it doesnot. A good argument remains a goodargument, however bad the motives (or alleged motives) of the person giving it,and a bad argument remains a bad argument however good the motives of theperson giving it.

It iscrucial to emphasize, though, that calling someone a name, attributing badmotives to him, or in some other way attacking a person or his character is not in itself a fallacy. It amounts to a fallacy only when what is at issue, specifically, is themerits of some claim he made or some argument he gave, and instead ofaddressing that, you change the subject and attack theperson.

But ofcourse, there are other contexts where the subject is the person or his character, rather than some argument he gave. For example, if a jury is trying to determinewhether a person’s eyewitness testimony is reliable, a lawyer is not committingan ad hominem fallacy if he notesthat the witness has been caught in lies in the past, or is known to harbor apersonal grudge against the person he’s testifying against. Or, when you are deciding whether to believea used car salesman, you are not guilty of an ad hominem fallacy when considering that his motive to sell you acar might bias the advice he gives you. Again, in cases like these, what is at issue is not some argument theperson gave, which might be considered entirely apart from him. What is at issue is the credibility of theperson himself.

Or supposeyou call someone a “jerk” precisely because he is acting like a jerk. There is no fallacy in that. Indeed, there is no fallacy even if he is not acting like a jerk, but you’re justin a bad mood. Name-calling may bejustified in the one case and unjustified in the other, but it is not a fallacy if the context isn’t one wherethe cogency of some argument he gave is what at issue, and you’re distractingattention from that.

People areespecially prone to make the mistake of confusing attacks on a person with the ad hominem fallacy when the context is adebate or public exchange of some other kind – where, of course, one or bothsides may be making arguments. SupposePerson A and Person B are engaged in some public dispute (on a blog, onTwitter, or wherever). Suppose Person Aaddresses the arguments of Person B, but Person B refuses to respond in kind,resorting instead to ad hominemattacks, or mockery, or changing the subject. Suppose that Person A, appalled by this behavior, calls attention toPerson B’s personal failings – characterizing Person B as intellectuallydishonest, or as a sophist, or as a buffoon, or the like. And suppose that Person B then objects tothis and accuses Person A of committingan ad hominem fallacy.

Is Person Aguilty of such a fallacy? Of coursenot. He has not attacked Person B as a way of avoiding addressing PersonB’s claims or arguments. On thecontrary, he has addressed those claimsand arguments. His negative estimation ofPerson B’s character is a separatepoint, and a correct one. Person B – whether out of cluelessbefuddlement or cynical calculation – makes of the false accusation that PersonA is guilty of an ad hominem fallacya smokescreen to hide the fact that it is really Person B himself who is guilty of this.

In the caseI just described, a person is accused of committing an ad hominem fallacy when he is notin fact doing so. But it can also happenthat a person pretends (or maybe even sincerely believes) that he is notcommitting an ad hominem fallacy whenhe is fact doing so. To change my example a bit, suppose Person Aand Person B are engaged in some public dispute. Suppose Person B never addresses Person A’sarguments, but simply and repeatedly flings terms of abuse, questions hismotives, and so on, with the aim of undermining Person A’s credibility with hisreaders. Suppose Person A accuses PersonB of ad hominem fallacies, and PersonB responds: “I’ve committed no such fallacy! After all, using such terms of abuse is not by itself fallacious. It’s only a fallacy when addressing anargument, and I haven’t beenaddressing your arguments. I’m justtelling people what a horrible person you are.”

Is Person Bthus innocent of an ad hominemfallacy in this case? Not at all. He may not have committed this fallacy in a direct way, but he has still done so indirectly. True, he has avoided addressing any specific argument Person A hasgiven. Hence he has not in that way committed an ad hominem fallacy. At the same time, though, he has, through ad hominem abuse, tried to poison hisreaders’ minds against taking seriously anyargument that Person A might happen to give. Hence he has deployed a fallaciously adhominem tactic in a general way.

The bottomline is this. Is a speaker resorting to ad hominem abuse as a way of trying to avoid having to address some claim orargument another person has given? Ifso, he is guilty of an ad hominemfallacy. If not, then he is not guiltyof such a fallacy (whether or not his abusive language is unjustifiable forsome other reason – that’s a separatequestion).

Appeal to emotion?

An appeal to emotion fallacy is committedwhen, instead of trying to convince one’s listener of a certain conclusion byoffering reasons that provide actual logical support for that conclusion, oneplays on the listener’s emotions. The strengthof the emotional reaction makes the conclusion seem well-supported, when in fact the premises do not providestrong grounds for believing it.

But here itis important to emphasize that the presence of an emotional reaction does notby itself make an argumentfallacious, not even if the speaker foresees such a reaction and indeed even ifhe intends it. To take an artificial examplein order to illustrate the point, suppose some follower of Socrates, havingjust heard the fatal verdict, wants desperately to believe that his heroSocrates will somehow never die. Youhope to bring him back to reality, and present him with the following argument:

All men are mortal

Socrates is a man

Therefore, Socrates is mortal

He contemplates this reasoning, sighs heavily and resignshimself to the cold, hard truth. Theargument raises profound emotions in him, as you knew it would. But have you committed a fallacy of appeal toemotion? Obviously not. The argument is no less sound than it wouldbe if someone with no emotional reaction at all had heard it.

Still, you might think, the reason there is no fallacy hereis that the emotions in question are not such as to incline the person to want to believe the conclusion. Quite the opposite. But suppose the emotions in question were of that sort. For example, suppose one of Socrates’ enemiesfeared that the hemlock would not kill him, and worried that perhaps Socrateswas immortal and could never be gotten rid of. Suppose you present him withthe same argument just given. He isreassured. But have you now, in thiscase, committed a fallacy of appeal to emotion?

No. Here too, theargument remains just as sound as it would be if some unemotional person who couldn’tcare one way or the other about Socrates had heard it. But what if you not only know that the personwill be pleased by the conclusion, but intendfor him to be pleased by it? What ifyou hope that his positive emotional response to the argument will make himmore likely to accept it? Wouldn’t that make it a fallacious appeal toemotion?

No, it would not. Forthe bottom line is that the premises are clearly true and the conclusionclearly follows validly from them. Thepresence or absence of an emotional reaction, of whatever kind, does not changethat in the least. Hence there is nofallacy of appeal to emotion. Such afallacy is committed only when there is some logical gap in the support the premises supply the conclusion,which the emotional reaction is meant to fill. But there is no such gap – and thus no fallacy.

Indeed, an emotional reaction can in some cases get a personto be more rational, not less. In the second example, the person’s fear thatSocrates might be immortal is unreasonable. He’s letting his fear of Socrates’ influence within Athens get the betterof him, and lead him to paranoid delusions. The argument you give him, preciselybecause it is pleasing to him, draws his attention away from these paranoidfeelings and back to reality.

Again, the example is admittedly artificial. But there are many topics that dorealistically carry heavy emotional baggage, yet where this does not entailthat arguments having to do with them must be guilty of the fallacy of appealto emotion. Matters of life and death –war, abortion, capital punishment, and the like – are like that. No matter what conclusions you draw and whatpremises you appeal to, they are bound to generate emotional reactions of somekind in your listener. But that does notentail that you are guilty of a fallacy of appeal to emotion.

The bottom line is this. Are the premises of the argument true? Do they in fact provide logical support for the conclusion (whetherdeductive validity or inductive strength)? Then the argument is not guilty of a fallacy of appeal to emotion,whether or not it also happens to generate an emotional reaction in thelistener, and whatever that reaction happens to be.

Slippery slope?

A third fallacy that is widely misunderstood is the slippery slope fallacy. Someone commits this fallacy when he claimsthat a certain view or policy will lead to disastrous consequences, but withoutoffering adequate support for this judgement. It is an instance of the more general error of jumping to conclusions orinferring well beyond what the evidence appealed to would support.

For example, suppose someone criticized a proposed small taxhike by claiming that it would inevitably lead to a radically egalitarian redistributionof wealth. It is hard to imagine howthis would fail to count as a slippery slope fallacy. Is there a logical connection between raising taxes slightly and radicallyequalizing shares of wealth by way of redistribution? No, and itis not hard to formulate principles that would both allow for some taxation while at the same time rulingout radically redistributive taxation. Isthere nevertheless some strong causal connectionbetween raising taxes slightly and radically redistributing wealth? Obviously not, since there have as a matterof historical fact been many cases where taxes were raised, but were neverfollowed by a radically egalitarian redistribution of wealth.

Notice that the problem here, though, is not that the argument claims that bad consequences wouldfollow. The problem is that the argumentdid not back up this claim. This is often overlooked by people who accuseothers of the slippery slope fallacy. They seem to think that anyclaim that bad consequences will follow from a certain view or policy amountsto a slippery slope fallacy.

In fact, there is no fallacy as long as someone explains exactly how the bad consequences aresupposed to follow. If you can show thatA logically entails Z, or that itdoes so when conjoined with some other clearly true assumptions, then you havenot committed a slippery slope fallacy. Or if you can identify some specificcausal mechanism by which A will lead to Z, then you have not committed aslippery slope fallacy. You commit such afallacy only when you jump from A to Z withoutfilling in the gap between them.

What if you are wrong about the claim that A logicallyentails Z, or wrong about the causal mechanism you claim links them? You are still not guilty of a slippery slopefallacy. True, you are mistaken, and perhaps guilty of someother logical error. But you haven’tcommitted a slippery slope fallacy,specifically, if you at least proposed some specific means by which A wouldlead to Z.

There are other fallacies too that are often misunderstood,but that suffices to make the point. Knowledge of the fallacies is essential to reasoning well, but it is oflimited value if it is merely superficialknowledge, and may in that case even impede careful reasoning. It can lead to seeing fallacies where they donot exist, and thus lead away from truth rather than toward it. And if one’s knowledge of fallacies isdeployed merely as a further rhetoricalmeans of trying to make an opponent look bad, it constitutes sophistry rather than remedying sophistry.

Furtherreading:

Thead hominem fallacy is a sin

October 2, 2023

Michael F. Flynn (1947-2023)

It is withmuch sadness that I report that Michael F. Flynn, well-known science fictionwriter and longtime friend of this blog, has passed away. Mike’s daughter made the announcement athis blog yesterday.

It is withmuch sadness that I report that Michael F. Flynn, well-known science fictionwriter and longtime friend of this blog, has passed away. Mike’s daughter made the announcement athis blog yesterday. That Mikewill be remembered for his work in science fiction goes without saying. But it is worth emphasizing too that he wasan irreplaceable presence in the blogosphere, who showed the potential of themedium for work of substance and lasting value. I doubt he ever posted anything that didn’t reward his readers’attention, with writing that wore lightly Mike’s learning not only in the sciencesbut also in philosophy, theology, and history. He was for many years a regular and welcome contributor to the commentssection of this blog, raising the tone simply by virtue of his presence. One of the things I most admired about himwas the calm and patient manner with which he would respond to even the mostobnoxious and ignorant interlocutors. Henever had to say that he knew what hewas talking about, while his opponent didn’t. He simply showed it by typing up a few sentences.

I had thehonor and pleasure of meeting Mike in person only once, at a conference in NewYork City at which the esteemed Matt Briggswas also present. The three of us “bloggersin arms” marked the event with aphoto. (It was also an honor, and athrill, when Mike had a character cite me as an authority in his philosophicalSF short story “Places Where the Roads Don’t Go,” in his collection CaptiveDreams. Thanks, Mike!)

Matt hasposted his own reflections about Mike at his blog.

Though Iknew Mike mainly from our online interactions, I have to say it felt like a gutpunch to learn of his death. Perhapsthat was for the usual selfish reason that all of us are sad at the death of aperson we like and admire – that we know wewill be worse off. Thank you for yourwork, Mike, and may God bless and protect your soul. You and yours are in our prayers. RIP.

September 27, 2023

Aquinas on the will’s fixity after death

My essay “Aquinas onthe Fixity of the Will After Death” appears in New Blackfriars. (It’sbehind a paywall, I’m afraid.) Here’sthe abstract:

My essay “Aquinas onthe Fixity of the Will After Death” appears in New Blackfriars. (It’sbehind a paywall, I’m afraid.) Here’sthe abstract:Aquinas holds that after death, thehuman soul can no longer change its basic orientation either toward God or awayfrom him. He takes this to be knowablenot only from divine revelation but by purely philosophical reasoning. The heart of his position is that the basicorientation of an angelic will is fixed immediately after its creation, andthat the human soul after death is relevantly like an angel. This article expounds and defends Aquinas'sposition, paying special attention to the action theory underlying it.

This is atopic I’ve written about here at the blog, but this new academic articleexplores it more systematically and in greater depth. I will also be addressing it in the book onthe soul and I have been working on for some time and hope to finish by year’send.

September 26, 2023

Augustine on false community

In anew article at Postliberal Order,I discuss the perverse forms of human community identified and criticized byAugustine in the Confessions, and howwhat he has to say applies to our times.

In anew article at Postliberal Order,I discuss the perverse forms of human community identified and criticized byAugustine in the Confessions, and howwhat he has to say applies to our times.

September 20, 2023

The Death Penalty and Genesis 9:6: A Reply to Mastnjak (Guest article by Timothy Finlay)

Genesis 9:6 famously states: “Whoever sheds the blood ofman, by man shall his blood be shed; for God made man in his own image” (RSV).This has traditionally been understood by Jews and Christians alike assanctioning capital punishment. In arecent article at Church Life Journal,Nathan Mastnjak has argued on grammatical grounds for an alternative reading ofthe passage, on which it does not support the death penalty. What follows is aguest article replying to Mastnjak by Timothy Finlay, who is Professor ofBiblical Studies at Azusa Pacific University and a member of the NationalAssociation of Professors of Hebrew.

Genesis 9:6 famously states: “Whoever sheds the blood ofman, by man shall his blood be shed; for God made man in his own image” (RSV).This has traditionally been understood by Jews and Christians alike assanctioning capital punishment. In arecent article at Church Life Journal,Nathan Mastnjak has argued on grammatical grounds for an alternative reading ofthe passage, on which it does not support the death penalty. What follows is aguest article replying to Mastnjak by Timothy Finlay, who is Professor ofBiblical Studies at Azusa Pacific University and a member of the NationalAssociation of Professors of Hebrew.In his article, Nathan Mastnjak writes,“The translation ‘by a human shall that person’s blood be shed’ is not strictlyimpossible, but given the norms of Classical Hebrew grammar, it should beviewed as prima facie unlikelyespecially since there is a much more plausible translation that iscontextually appropriate and grammatically mundane.” This has it completelybackward. It is Mastnjak’s claim that the ב inGenesis 9:6 be construed as expressing price or exchange that, while notstrictly impossible, flies in the face of Hebrew lexicons and grammars – incontrast to the standard translations (both Jewish and Christian) which arecontextually and canonically appropriate and grammatically mundane.

Mastnjak rightly examines bothgrammatical issues about the specific phrase translated in the NRSV as “by ahuman shall that person’s blood be shed” (Gen 9:6) and contextual issuesarising from its literary connection. Unfortunately, both aspects of hisargument are seriously flawed and completely ignore the mountain ofscholarship, Jewish and Christian, medieval and modern, which support thetraditional translations. The implications of the traditional translations, asMastnjak correctly diagnoses, install “the death penalty as a common principleof the Natural Law and thus would make it be applicable and theoreticallyusable by all human societies.” This includes recent Catholic scholarship thatexplicitly supports Pope Francis in his desire to abolish the death penalty butconcedes that the God who executed retribution for violence in the flooddelegated in Genesis 9:6 this power to humans created in the image of God. Andit goes at least as far back as the Toseftain the late second century. The Toseftaregards the establishing of human courts of justice to administer the deathpenalty as part of the Noahic code in Genesis 9.

Mastnjak’s central grammatical pointsare that “Of the hundreds of passive verbs in the Hebrew Bible, the grammarianscan find only a handful of possible cases where the agent of a passive verb isexplicitly expressed” and that a frequent usage of the Hebrew preposition ב is “toexpress price or exchange.” One problem for Mastnjak is that major lexicons andgrammars with entries on the Hebrew preposition ב are wellaware of both these facts and prefer to render the ב inGenesis 9:6 not as a ב pretii expressing price or exchangebut as indicating that humans are involved as the instrument through whichmurderers will be executed. These lexicons and grammars include GKC (the grammar byGesenius-Kautzsch-Cowley), BDB (thelexicon by Brown-Driver-Briggs), BHRG(the reference grammar by van der Merwe-Naudé-Kroeze), IBHS and HSTE (the syntaxgrammars by Waltke-O’Connor and by Davidson repectively) and DCH (Dictionary of Classical Hebrew,edited by David Clines, which does use a “perhaps” for Genesis 9:6 as anexample of the ב pretii but includes it straightforwardly as an example of ב ofagent). Other than a second option “perhaps” in DCH, the major grammars and lexicons discussing the relevant ב in Genesis 9:6 do not support Mastnjak’s contention.

Another problem for Mastnjak is thatthe construction need not be an agent of a passive verb for Genesis 9:6 toestablish the death penalty for murder as a standard judicial principle.Genesis 21:12, another construction with a passive and a ב plus nounsegment with human semantics, is plausibly translated “it is through Isaac thatoffspring will be named for you.” Although Isaac is not the direct agent here,without Isaac’s involvement the people of Israel as Abraham’s quintessentialoffspring would not have existed. Such a usage applied to Genesis 9:6 wouldhave emphasized humans not as the agents of execution but that it is throughhumans sentencing the murderer that the murderer’s blood would be shed. Thiswould still entail an establishment of capital punishment.

And this is precisely how two of the major targums (earlyAramaic translations, which often engage in elaboration) translate the verse.Targum Onqelos renders the clause, “He who sheds the blood of a human beforewitnesses, through sentence of the judges shall his blood be shed.” Moreextensive legal codes in Torah prescribe the presence of two or three witnessesas a necessary condition for a murderer to be executed. Targum Onqelosclarifies that Genesis 9:6 does not override this condition. TargumPseudo-Jonathan further expands: “Whoever sheds the blood of a human in thepresence of witnesses, the judges shall condemn him to death, but whoever shedsit without witnesses, the Lord of the world will take revenge of him on the dayof great judgment.” Targum Pseudo-Jonathan also provides a rebuttal toMastnjak’s second argument – that the context of the preceding verse, Genesis9:5, where God requires an accounting for human blood shed by animals orhumans, precludes capital punishment in Genesis 9:6. Pseudo-Jonathan clearlyincludes the context of Genesis 9:5 in its understanding of the followingverse; God authorizes capital punishment in circumstances of due legal processwhere the evidence is clear but will personally revenge the murder victimotherwise.

The third problem for Mastnjak on the grammatical side isthat the two resources he does cite do more to hurt his position than to helphim. His first resource is a paragraph in a four page book review of a Hebrewgrammar, not the type of source one would expect to carry the weight ofrefuting over two millennia of Jewish and Christian interpretation of Genesis9:6. His second resource, the Hebrew grammar by Joüon and Muraoka, has higherrenown but argues against Mastnjak’s position.

First, here is page 151 of Dennis Pardee’s book review involume 53 of Journal of Near EasternStudies (1994) of Waltke and O’Connor’s AnIntroduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax: “Occasionally they give in to thenorms of Indo-European syntax or do not indicate the rarity of a givenconstruction. For example, on p. 385, they state that ‘in the complete passive,the agent may be indicated by a prepositional phrase…’ (cf. also p. 213). Notonly have they omitted a statement regarding the rarity of the construction butmost of their examples can be explained, within the terms of the Hebrewprepositional construction, otherwise (bin Gen. 9:6 = b of price; bhm in Exod. 12:16 = ‘among them’).”Unfortunately, Waltke and O’Connor only cite three examples of passiveinvolving ב of agent (Gen 9:6; Exod 12:16; and Deut33:29), and I would go farther than Pardee and argue that Exodus 12:16 isbetter translated “among them” than “by them.” Exodus 12:16 is not construed byother grammarians as indicating an agent. Genesis 9:6 is the verse underdispute. Tellingly, even Pardee does not object (in this book review anyway) toregarding Deuteronomy 33:29 as a ב of agent or atleast some instrumental usage. But the list of plausible passive constructionswith a ב of agent extends beyond those mentioned byWaltke and O’Connor. Leaving the disputed Genesis 9:6 aside, the examples ofthe construction in question in at least one of DCH or BDB are “wascommanded by the Lord” (Num 36:2); “a people saved by the Lord” (Deut 33:29),“Israel is saved by the Lord” (Isa 45:17), “by a prophet he was guarded” (Hosea12:13), and “by you, the orphan finds mercy” (Hosea 14:3). In short, Pardee iscorrect that Waltke and O’Connor could have done a better job on thisconstruction, but if Mastnjak had consulted some lexicons in addition to a bookreview, he would have discovered that the construction is not as rare as he hadpresumed.

Things get much worse for Mastnjak in regard to his secondsupposed support, Joüon and Muraoka’s deservedly influential A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew (Rome:Biblico, 2006). That resource (ON THE VERY PAGE MASTNJAK REFERENCES) explicitlyargues for the traditional translation of Genesis 9:6 that Mastnjak wants toreject! Mastnjak cites Joüon and Muraoka as follows, “In Hebrew (and classicalSemitic languages in general) the marking of an agent with a verbmorphologically marked as passive is rather limited in scope when compared withmany Indo-European languages” (page 454). True, but what really matters iswhether Genesis 9:6 is an example of an agent with a verb morphologicallymarked as passive. And this is what Joüon-Muraoka say about that on the samepage 454: “In Gn 9.6 ב is used and not מן because man ishere the instrument of justice (the exception to the law which forbids theshedding of blood, vs. 5): He who sheds aman’s blood, by (means of) a man shall his blood be shed(1).”2

Like Mastnjak, Joüon-Muraoka note the connection betweenverses 5 and 6 but draw a different conclusion to him. The footnote in thisquote mentions not only Ernst Jenni’s entire volume on the Hebrew preposition ב in his massive three volume work on Hebrew prepositions, butalso the medieval Jewish commentator Ibn Ezra. Ibn Ezra argues that Genesis 9:6obligates the descendants of Noah to execute a murderer. Radak (Rabbi DavidKimhi), perhaps the greatest medieval Hebrew grammarian, explains theconnection to Genesis 9:5 in similar manner as do Targum Onqelos and TargumPseudo-Jonathan: if there are witnesses, then the judges must ensure that themurderer is executed; but when there are no witnesses, God may personallyrequire the reckoning.

Other modern Hebraists see more examples of agential ב with passive than do Joüon and Muraoka, and the disagreementmay be more terminological than substantial. Joüon-Muraoka argue that themeaning in Deuteronomy 33:29 and Isaiah 45:17 is saved “through YHWH” ratherthan “by YHWH” but this is an exceptionally fine distinction given thatBrown-Driver-Briggs (on page 89) equates “through YHWH” with “by YHWH’s aid” asan agential subcategory of the more general ב of instrument or means. Even if one argued that Joüon-Muraokashould, by consistency with their understanding of Deuteronomy 33:29 and Isaiah45:17, have translated Genesis 9:6 as “through humans shall his man be shed,” withthe “through” designating witnesses and judges rather than the “by” ofexecutioners, i.e. along the lines of Targums Onqelos and Pseudo-Jonathan, thiswould not have helped Mastnjak’s case that Genesis 9:6 does not establishcapital punishment.

Mastnjak’s grammatical argument regarding באדם is a complete bust. His second argumentis likely worse. He states that context supplies the “implied agent responsiblefor shedding the blood the murderer. We need search the context no further thanthe immediately previous verse, Genesis 9:5: ‘But indeed I will seek your bloodfor your lives. From every beast I will seek it. From the hand of man, each manfor his brother, I will seek the blood of a man.’” And when Mastnjak says, “weneed search the context no further than the immediately previous verse,” hebacks this hermeneutical decision up by spectacularly ignoring the contexts of:the preceding flood narrative after which Genesis 9 represents a new beginning;the pattern of violence from Cain to Lamech through to the whole earth beingfilled with violence to which Genesis 9:5-6 is a new response; thehistorical-comparative context of other flood stories in the Ancient Near East;the historical setting of the author of Genesis 9 living at a time whensocieties including Ancient Israel had law codes prescribing capital punishmentfor murder; and the literary setting of Genesis 1-11 which is replete withetiologies of how present institutions and other realities originated.

In fact, in his contextual argument for how to translate thefirst half of Genesis 9:6, Mastjnak does not even consider the second half ofthe verse, whose discussion of the image of God clearly connects it back toGenesis 1:27-28. Genesis 9:6b looks like a narratorial comment within thedivine speech3 and certainly is a clause which purports to explainthe rationale for the prescription in the first half of the verse; surely atleast that context would have been germane! But all Mastnjak gives us is that“God commits himself in Genesis 9:5 to a mysterious mode of intervention in theworld in which somehow – he does not say how – he himself will intervene toavenge any creature, man or beast, that violates the sanctity of human life.This commitment to avenge the blood of any manslayer interprets the followingverse, Genesis 9:6, and provides the agent that the grammar does not specify.Who will shed the blood of the murderer? God himself.” In this interpretation,Genesis 9:6a adds basically nothing to what is said in verse 5, a weaknesscompared to the traditional translation which shows one manner in which Godpunishes the murderer (no one believes that all murderers are executed). VictorHamilton points out that reading Genesis 9:6 as “for man shall his blood beshed” entails that Genesis 9:5-6 exhibits a tautology; and Kenneth Matthewsargues, “Since the value of the victim’s life already is presented in v. 5, v.6a is best taken as building on this by adding that the divine means of God’s‘accounting’ includes human agency.”4

Mastnjak is entitled to offer counterarguments to Matthews,Hamilton, and others. What he is not entitled to do is give the impression thatthose who translate Genesis 9:6 in the traditional manner have not taken thecontext of the previous verse into account; they most certainly have and thatis part of why they reject seeing Genesis 9:6 as an example of ב pretii.

However much Mastnjak’s grammatical argument lackedengagement with the relevant lexicons, it did at least cite two resources (evenif one of them actually sunk his position). But in his contextual argument,Mastnjak’s audacity reaches new heights. He seeks to overturn the overwhelmingconsensus of Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant commentators and translators by acontextual argument that ignores almost all the contexts that responsibleexegetes take into account – and breathlessly does so without citing a singlescholar in making this argument.

Mastnjak is right thatthere is a certain vagueness concerning the agent of execution. But this fitswith a variety of agents, not just God himself. John Wesley comments, “That is,by the magistrate, or whoever is appointed to be the avenger of blood. Beforethe flood, as it should seem by the story of Cain, God took the punishment of murder into his own hands; but nowhe committed this judgement to men, to masters of families at first, andafterwards to the heads of countries.”5 Likewise, John Waltonwrites, “Accountability to God for preserving human life is put into humanity’shands, thus instituting blood vengeance in the ancient world and capitalpunishment in modern societies. In Israelite society blood vengeance was in thehands of the family of the victim.”6

Regarding the context of Genesis 9:6b, “Because in the imageof God he made man,” Gordon Wenham comments, “It is because of man’s specialstatus among the creatures that this verse insists on the death penalty formurder.”7 But it is also “man’s special status” as being in theimage of God – whether this refers to analogically shared attributes such asintellect and will or whether it is as God’s royal representatives to the restof creation – that befits humans to be instruments of divine punishment.8David vanDrunen comments, “The image of God carried along with it a naturallaw, a law inherent to human nature and directing human beings to fulfill theirroyal commission to rule over creation in righteousness and justice.”9

We now turn to the context of Genesis 9:1-7 as theconclusion and remedy episode to the Genesis flood narrative, comparing andcontrasting it with the flood account in the Atrahasis Epic. Tikvah Frymer-Kenskywrites, “The structure presented by the Atrahasis Epic is clear. Man is created… there is a problem in creation … remedies are attempted but the problemremains … the decision is made to destroy man … this attempt is thwarted by thewisdom of Enki … a new remedy is instituted to ensure that the problem does notarise again.”10 In Genesis, a similar structure occurs with lessemphasis on earlier remedy attempts and with God paralleling both the role ofthe main gods to destroy human beings and Enki’s role in providing a means ofescape for Noah/Atrahasis. Comparing these stories helps us focus on the reasonfor the flood and on the changes made so that the world after enabled thecontinued existence of human beings.11

In the Atrahasis Epic, the problem was overpopulation. Thisis emphatically not the case in Genesis. God’s speech in Genesis 9:1b-7 isstructured so that introductory commands to be fertile (Gen 9:1-b) andconcluding commands to be fertile (Gen 9:7) envelop instruction concerning animals(Gen 9:2-4) and concerning the shedding of human blood (Gen 9:5-6).

The instruction concerning animals includes an assertivethat animals will fear humans (Gen 9:2a), an exercitive granting humansdominion over animals (Gen 9:2b, linking back to Gen 1:28), a permission to eatanimals (Gen 9:3), and a restriction of the permission by prohibiting theeating of blood (Gen 9:4). If the Jewish understanding is correct that Genesis9:2-4 signals that prior to the deluge humans were forbidden to eat animals (Genesis1 contains a permission to eat plants, but no permission to eat animals orprohibition thereof is mentioned), then the antediluvian mandating ofvegetarianism might have been a contributing cause to the violence. Againstthis interpretation is that the distinction between clean and unclean foods ismentioned in the flood story, or in one of its sources, and that the text makesno link between human dietary habits and the divine decision to bring about aflood.

In any case, Genesis 9:5-6 which concerns human blood shedmust be read as the remedy to the violence filling the earth which Genesisexplicitly records as the reason for the divine decision to destroy all flesh(Gen 6:11, 13). As Frymer-Kensky observes, “Only three stories are preserved inGenesis from the ten generations between the expulsion from the Garden and thebringing of the flood. Two of these, the Cain and Abel story (Gen 4:1-15) andthe tale of Lemech (Gen 4:19-24), concern the shedding of human blood.”12Frymer-Kensky then discusses the remedy of Genesis 9:1-7, developed in laterJudaism as the Noahic Code,13 as “a system of universal ethics, a‘Natural Law’ system in which the laws are given by God” in which Genesis 9:6contains “the declaration of the principle of the inviolability of human lifewith the provision of capital punishment for murder.”14 Nahum Sarna,justifies rendering Genesis 9:6 as “by man,” indicating the instrument ofpunishment, similarly sees it as a remedy to the pre-flood situation: “Humaninstitutions, a judiciary, must be established for the purpose. Thisrequirement seeks to correct the condition of ‘lawlessness’ that existed priorto the Flood (6:11).”15 Sarna also makes a grammatical argumentabout the crucial clause, namely that a phrase containing “blood” and thepassive “shall be shed” always occurs in the Bible with a human agent (Lev 4:7,18, 25, 30, 34; Deut 12:17; 19:10), not a divine one. Jozef Jancovic is anotherscholar who makes the connection between Genesis 9:5-6 and the shedding of bloodin the Cain and Lamech stories as well as the violence in Genesis 6:11-13 thatwas the reason for the flood.16 Jancovic concludes, “God heredelegates humanity with the power to punish human blood-shedding, and just asin the creation story, this delegation of power by God is justified by thecreation of humanity in God’s image (Gen 9:6b).”17 He also connectsthe first plain poetry in Genesis 4:23-24 with the poetic structure in Genesis9:6a as indicating that the permanent problem of violence had been solved inthe lex talionis.18 Ofcourse, by the time Genesis 9:6 was written, the lex talionis was a part of many ancient societies, so Genesis 9:6can be seen as one of the many etiologies in Genesis 1-11.

None of these larger settings, which provide furtherevidence for the traditional translation of Genesis 9:6, are considered inMastnjak’s contextual argument. And only by neglecting to discuss what othercommentators have said about the grammatical considerations, the largersetting, and the immediate context in Genesis 9:5-6 can Mastnjak dare toconclude his article, “These observations on Genesis 9:6 do not, of coursesettle the question of the morality of capital punishment or how Pope Francis’srevision of the Catechism should be understood in relation to previous Churchteaching. But they do entail that ifsupport for the death penalty is to be found in Sacred Scripture, it should besought outside the covenant with Noah in Genesis 9.” No they do not entail thatat all! The entire article is a bust.

Timothy Finlay, Professor ofBiblical Studies, Azusa Pacific University

Notes:

1 SeeJenni, Beth, 178–80, but so alreadyIbn Ezra ad loc.

2 PaulJoüon and T. Muraoka, A Grammar ofBiblical Hebrew (Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico, 2006), 454.

3 JohnSailhammer notes not only the conjunction , “because,” but the shift to the 3rdperson reference to God, and comments, “Already the narrative has become aplatform for the development of the biblical law,” in “Genesis,” The Expositor’s Bible Commentary:Genesis-Leviticus (Revised Edition) (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 132.

4 KennethA. Matthews, Genesis 1-11:26 (NewAmerican Commentary; Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1996), 405.

5John Wesley, Explanatory Notes upon theOld Testament (Bristol: William Pine, 1765), 41.

6 John H.Walton, Genesis (NIV ApplicationCommentary; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001), 343.

7 GordonJ. Wenham, Genesis 1–15, vol. 1 of Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word,Incorporated, 1987), 194.

8 See David Novak, Natural Law in Judaism (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1998) and Steven Wilf, The Law before the Law (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008) who drawsfrom Maimonides’ Guide to the Perplexed.

9 David vanDrunen, A Biblical Case for Natural Law (GrandRapids: Acton Institute, 2008), 14. VanDrunen comes from a Calvinist tradition.Calvin, like Luther and Wesley, regarded Genesis 9:6 as establishing capitalpunishment for homicide. See also Gerhard von Rad’s commentary on Genesis. Radobserved that Genesis 9:6 holds in tension the sanctity of human life (murderdeserves capital punishment) and human responsibility to carry out punishment(executing a murderer is permissible). Similarly, Rusty Reno’s commentary onGenesis sees this tension as “the capacity to exercise authority for the sakeof a higher principle” Genesis (GrandRapids: Brazos Press, 2010), 125.

10 Tikvah Frymer-Kensky,“The Atrahasis Epic and its Significance for our Understanding of Genesis 1-9,”Biblical Archaeologist (1977), 149.

11 Frymer-Kensky, 150.

12 Frymer-Kensky, 152-53.

13 See for example Tosefta Abodah Zarah 8:4.

14 Frymer-Kensky, 152.

15 Nahum Sarna, Genesis (The JPS Torah Commentary;Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 62.

16 Josef Jancovic, “BloodRevenge in Light of the Imago Dei in Genesis 9:6,” The Biblical Annals 10 (2020) 198-99.

17 Jancovic, 203.

18 Jancovic, 199.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 335 followers