Edward Feser's Blog, page 11

May 4, 2024

Dignitas Infinita at The Catholic Thing

At The Catholic Thing, Diane Montagna interviewsme about the Vatican’s recent Declaration Dignitas Infinita.

At The Catholic Thing, Diane Montagna interviewsme about the Vatican’s recent Declaration Dignitas Infinita.

April 29, 2024

Plato and Aristotle on youth and politics

As faculty,including even philosophy professors, aid and abet student bad behavior oncampus, it is worth considering what the most serious thinkers of the Westerntradition would have thought about the political opinions and activities of theyoung. What follows are some relevantpassages from Plato and Aristotle in particular. For purposes of the present article, I put toone side the specific subject matter of the recent protests, because it is notrelevant to the present point. What isrelevant is that the manner in which the protesters’ opinions are formed andexpressed is contrary to reason. Thatwould remain true whatever they were protesting. Part of this is because mobsare always irrational. Butthey are bound to be even more irrational when they are composed of youngpeople.

As faculty,including even philosophy professors, aid and abet student bad behavior oncampus, it is worth considering what the most serious thinkers of the Westerntradition would have thought about the political opinions and activities of theyoung. What follows are some relevantpassages from Plato and Aristotle in particular. For purposes of the present article, I put toone side the specific subject matter of the recent protests, because it is notrelevant to the present point. What isrelevant is that the manner in which the protesters’ opinions are formed andexpressed is contrary to reason. Thatwould remain true whatever they were protesting. Part of this is because mobsare always irrational. Butthey are bound to be even more irrational when they are composed of youngpeople.Don’t trust anyone under thirty

Plato heldthat even the guardians in his ideal city should not be permitted to studyphilosophy, and in particular the critical back-and-form of philosophical debate,before the age of thirty. And even then,they could do so only after acquiring practical experience in military service,the acquisition of a large body of general knowledge, and the intellectual disciplineafforded by mathematical reasoning. Ashe says in The Republic, “dialectic”(as he referred to this back-and-forth), when studied prematurely, “doesappalling harm” and “fills people with indiscipline” (Book VII, at p. 271 ofthe DesmondLee translation). For young andinexperienced people tend to make a game of argument and criticism, a means oftearing down traditional ideas without seriously considering what might be saidin favor of them or putting anything better in their place. Describing the young person who pursues suchsuperficial philosophizing, Plato writes:

He is driven to think that there’s nodifference between honourable and disgraceful, and so on with all the othervalues, like right and good, that he used to revere… Then when he’s lost anyrespect or feeling for his former beliefs but not yet found the truth, where ishe likely to turn? Won’t it be to a lifewhich flatters his desires? … And so we shall see him become a rebel instead ofa conformer…

You must have noticed how young men,after their first taste of argument, are always contradicting people just forthe fun of it; they imitate those whom they hear cross-examining each other,and themselves cross-examine other people like puppies who love to pull andtear at anyone within reach… So when they’ve proved a lot of people wrong andbeen proved wrong often themselves, they soon slip into the belief that nothingthey believed before was true…

But someone who’s a bit older… willrefuse to have anything to do with this sort of idiocy; he won’t copy those whocontradict just for the fun of the thing, but will be more likely to follow thelead of someone whose arguments are aimed at finding the truth. He’s a more reasonable person and will getphilosophy a better reputation. (Book VII, at pp. 272-273)

Similarly,in the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotlesays that political science (by which he meant, not primarily what is todaycalled by that name, but rather what we would today call political philosophy)is not a suitable area of study for the young. He writes:

A young man is not a fit person toattend lectures on political science, because he is not versed in the practicalbusiness of life from which politics draws its premises and subjectmatter. Besides, he tends to follow hisfeelings, with the result that he will make no headway and derive no benefitfrom his course… It makes no difference whether he is young in age or youthfulin character; the defect is due not to lack of years but to living, andpursuing one’s various aims, under the sway of feelings. (Book I, pp. 65-66 of the Thomsonand Tredennick translation)

This lack ofexperience and domination by feelings is commented on by Aristotle elsewhere inthe Ethics. For example, he observes that “the lives ofthe young are regulated by their feelings, and their chief interest is in theirown pleasure and the opportunity of the moment” (Book VIII, at p. 262). And he notes:

Although the young develop ability ingeometry and mathematics and become wise in such matters, they are not thoughtto develop prudence. The reason for thisis that prudence also involves knowledge of particular facts, which becomeknown from experience; and a young man is not experienced, because experiencetakes some time to acquire. (Book VI, at p. 215)

In the Rhetoric, Aristotle develops thesethemes in greater detail, writing:

The young are by character appetitiveand of a kind to do whatever they should desire. And of the bodily appetites they areespecially attentive to that connected with sex and have no control over it…They are irate and hot-tempered and of a kind to harken to anger. And they are inferior to their passions; forthrough their ambition they do not tolerate disregard but are vexed if theythink they are being wronged.

And they are ambitious, but even morekeen to win (for youth craves excess and victory is a kind of excess), and theyare both of these things rather than money-loving (they are least money-lovingof all through never having yet experienced shortage…) and they are notsour-natured but sweet-natured through their not having yet observed muchwickedness, and credulous through their not yet having been many timesdeceived, and optimistic… because they have not frequently met with failure…

And in all things they err rathertowards the excessively great or intense… (for they do everything in excess:they love and hate excessively and do all other things in the same way), andthey think they know everything and are obstinate (this is also the reason fortheir doing everything in excess), and they commit their crimes from arrogance ratherthan mischievousness. (Book II, Part 12, at pp. 173-74 of the Lawson-Tancredtranslation)

To summarizethe points made by Plato and Aristotle, then, young people: are excessivelydriven by emotion and appetite; lack the experience that is required forprudence or wisdom in practical matters; in particular, are prone to naïve idealismand an exaggerated sense of injustice coupled with arrogant self-confidence; andtend, in their intellectual efforts, toward sophistry and unreasonable skepticismtoward established ways. For thesereasons, their opinions about matters of ethics and politics are liable to befoolish.

Democracy dumbs down

This shouldsound like common sense, because it is. Andnotice that so far, Plato and Aristotle are describing the tendencies of theyoung as such, even in the best kinds of social and politicalarrangements. But things are even worsewhen those arrangements are bad. In The Laws, Plato warns that the youngbecome soft when pampered and affluent. “Luxury,”he says, “makes a child bad-tempered, irritable and apt to react violently totrivial things” (Book VII, at p. 231 of the Saunderstranslation). And again: “Supposeyou do your level best during these years to shelter him from distress andfright and any kind of pain at all… That’s the best way to ruin a child,because the corruption invariably sets in at the very earliest stages of hiseducation” (ibid.).

In The Republic, Plato argues that musicand entertainments that celebrate what is ignoble and encourage the indulgenceof desire corrupt the moral character of the young in a way that cannot fail tohave social and political repercussions:

The music and literature of a countrycannot be altered without major political and social changes… The amusements inwhich our children take part must be better regulated; because once they andthe children become disorderly, it becomes impossible to produce seriouscitizens with a respect for order. (Book IV, at pp. 125-26)

Similarly,in the Politics, Aristotle cautions:

Unseemly talk… results in conduct ofa like kind. Especially, therefore, mustit be kept away from youth… And since we exclude all unseemly talk, we mustalso forbid gazing at debased paintings or stories… It should be laid down thatyounger persons shall not be spectators at comedies or recitals of iambics,not, that is to say, until they have reached the age at which they come torecline at banquets with others and share in the drinking; by this time theireducation will have rendered them completely immune to any harm that might comefrom such spectacles… We must keep all that is of inferior quality unfamiliarto the young, particularly things with an ingredient of wickedness or hostility. (Book VII, at pp. 446-47 of the Sinclairand Saunders translation)

Plato’s Republic also famously argues thatoligarchies, or societies dominated by the desire for wealth, are disordered,and tend to degenerate into egalitarian democracies, which are even moredisordered. Ihave discussed elsewhere Plato’s account of the decay of oligarchy intodemocracy, and of democracy, in turn, into tyranny. Among the passages relevant to the subject athand are the following, from Book VIII:

The oligarchs reduce their subjectsto the state we have described, while as for themselves and their dependents –their young men live in luxury and idleness, physical and mental, become idle,and lose their ability to resist pain or pleasure. (p. 291)

The young man’s mind is filledinstead by an invasion of pretentious fallacies and opinions… [He] call[s] insolence good breeding, licenseliberty, extravagance generosity, and shamelessness courage… [He] comes tothrow off all inhibitions and indulge[s] desires that are unnecessary anduseless...

If anyone tells him that somepleasures, because they spring from good desires, are to be encouraged andapproved and others, springing from evil desires, to be disciplined andrepressed, he won’t listen or open his citadel’s doors to the truth, but shakeshis head and says all pleasures are equal and should have equal rights. (pp. 297-98)

A democratic society… goes on toabuse as servile and contemptible those who obey the authorities and reservesits approval, in private life as well as public, for rulers who behave likesubjects and subjects who behave like rulers…

It becomes the thing for father andson to change places, the father standing in awe of his son, and the sonneither respecting nor fearing his parents, in order to assert what he callshis independence…

The teacher fears and panders to hispupils… and the young as a whole imitate their elders, argue with them and setthemselves up against them, while their elders try to avoid the reputation ofbeing disagreeable or strict by aping the young and mixing with them on termsof easy good fellowship. (pp. 299-300)

In short,the affluence and egalitarian spirit of a wealth-oriented society that hasdecayed into a democracy (in Plato’s sense of that term, which has more to dowith ethos than the mechanics of governance) greatly exacerbate the failings towhich the young are already prone. Inparticular, it makes them even softer and thus unable to deal maturely withchallenges and setbacks, even more prone to sophistry and excessive skepticism,even more contemptuous of authority and established customs, and more vulgarand addicted to vice. Even worse, theegalitarian spirit of democracy makes adults more prone to acquiesce in this badbehavior, or even to ape it themselves. A general spirit of license and irrationality sets in and undermines thesocial order, greasing the skids for tyranny (in a way that, again, I describein the article linked to earlier).

What then,would Plato and Aristotle think of the mobs of shrieking student protesters wesee on campuses today (or for that matter, the student mobs of the 1960s and ofevery decade between then and now)? To askthe question is to answer it. Nor is ita mystery what they would think of the professors who egg on this foolishness. They are the heirs, not of Plato andAristotle, but of the sophists to whom Plato and Aristotle sharply contrastedthe true philosopher.

April 19, 2024

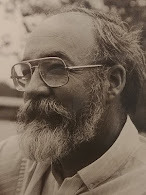

Daniel Dennett (1942-2024)

Prominentphilosopher of mind, apostle of Darwinism, and New Atheist writer DanielDennett hasdied. I have been very critical ofDennett over the years, but he had two great strengths. First, he wrote with crystal clarity, nomatter how difficult the subject matter. Second, as even we critics of materialism canhappily concede, he could be very insightful on the distinctive nature ofpsychological modes of description and explanation (even if he went wrong when addressinghow these relate metaphysically to physical modes of description andexplanation). It is also only fair toacknowledge that of the four original New Atheist tomes (the others penned byDawkins, Harris, and Hitchens) his Breakingthe Spell, despite its faults, was the one that was actually intellectuallyinteresting. RIP

Prominentphilosopher of mind, apostle of Darwinism, and New Atheist writer DanielDennett hasdied. I have been very critical ofDennett over the years, but he had two great strengths. First, he wrote with crystal clarity, nomatter how difficult the subject matter. Second, as even we critics of materialism canhappily concede, he could be very insightful on the distinctive nature ofpsychological modes of description and explanation (even if he went wrong when addressinghow these relate metaphysically to physical modes of description andexplanation). It is also only fair toacknowledge that of the four original New Atheist tomes (the others penned byDawkins, Harris, and Hitchens) his Breakingthe Spell, despite its faults, was the one that was actually intellectuallyinteresting. RIP

April 13, 2024

Mansini on the development of doctrine

My review of Guy Mansini’s excellent new book TheDevelopment of Dogma: A Systematic Account appears in the May 2024 issue of First Things.

My review of Guy Mansini’s excellent new book TheDevelopment of Dogma: A Systematic Account appears in the May 2024 issue of First Things.

April 11, 2024

Two problems with Dignitas Infinita

This weekthe Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) published the Declaration

DignitasInfinita

, on the topic of human dignity. I am as weary as anyone of the circumstancethat it has now become common for new documents issued by the Vatican to be metwith fault-finding. But if the faultsreally are there, then we oughtn’t to blame the messenger. And this latest document exhibits two seriousproblems: one with its basic premise, and the other with some of theconclusions it draws from it.

This weekthe Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) published the Declaration

DignitasInfinita

, on the topic of human dignity. I am as weary as anyone of the circumstancethat it has now become common for new documents issued by the Vatican to be metwith fault-finding. But if the faultsreally are there, then we oughtn’t to blame the messenger. And this latest document exhibits two seriousproblems: one with its basic premise, and the other with some of theconclusions it draws from it.Capital punishment

To beginwith the latter, I hasten to add that mostof the conclusions are unobjectionable. They are simply reiterations of longstanding Catholic teaching onabortion, euthanasia, our obligations to the poor and to migrants, and soon. The document is especially helpfuland courageous in strongly condemning surrogacy and gender theory, which willwin it no praise from the progressives the pope is often accused of being tooready to placate.

There areother passages that are more problematic but perhaps best interpreted asimprecise rather than novel. Forexample, it is stated that “it is very difficult nowadays to invoke therational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of the possibilityof a ‘just war.’” That might seem tomark the beginnings of a reversal of traditional teaching that has beenreiterated as recently as the current Catechism. However, DignitasInfinita also “reaffirm[s] the inalienable right to self-defense and theresponsibility to protect those whose lives are threatened,” which are themesthat recent statements of just war doctrine have already emphasized.

The oneundeniably gravely problematic conclusion DignitasInfinita draws from its key premise concerns the death penalty. Pope Francis already came extremely close todeclaring capital punishment intrinsically immoral when he changed theCatechism in 2018, so that it now says that “the death penalty is inadmissiblebecause it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person.” But that left open the possibility that whatwas meant is that it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the personunless certain circumstances hold,such as the practical impossibility of protecting others from the offenderwithout executing him (even if this reading is a bit strained). The new DDF document goes further and flatlydeclares that “the death penalty… violates the inalienable dignity of everyperson, regardless of the circumstances”(emphasis added).

This simplycannot be reconciled with scripture and the consistent teaching of all popeswho have spoken on the matter prior to Pope Francis. That includes Pope St. John Paul II, despitehis well-known opposition to capital punishment. In EvangeliumVitae, even John Paul taught only:

Punishment… ought not go to theextreme of executing the offender exceptin cases of absolute necessity: in other words, when it would not be possibleotherwise to defend society. Todayhowever, as a result of steady improvements in the organization of the penalsystem, such cases are very rare, if not practically non-existent.

And theoriginal version of the Catechism promulgated by John Paul II stated:

The traditional teaching of theChurch has acknowledged as well-founded the right and duty of the legitimatepublic authority to punish malefactors by means of penalties commensurate withthe gravity of the crime, not excluding,in cases of extreme gravity, the death penalty. (2266)

In short, JohnPaul II (like scripture and like every previous pope who spoke on the matter)held that some circumstances can justifycapital punishment, whereas Pope Francis now teaches that no circumstances can ever justify capitalpunishment. That is a directcontradiction. Now, Joseph Bessette andI, in our book ByMan Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment,have shown that the legitimacy in principle of the death penalty has in factbeen taught infallibly by scripture and the tradition of the Church. I’ve also made the case for this claim onother occasions, such as in thisarticle. Hence, if PopeFrancis is indeed teaching that capital punishment is intrinsically wrong, itis clear that it is he who is in thewrong, rather than scripture and previous popes.

If defendersof Pope Francis deny this, then they are logically committed to holding thatthose previous popes erred. Either way, some pope or other has erred, so that itwill make no sense for defenders of Pope Francis to pretend that they aresimply upholding papal magisterial authority. To defend Pope Francis is to reject the teaching of the previous popes;to defend those previous popes is to reject the teaching of Pope Francis. There is no way to defend all of them atonce.

This is inno way inconsistent with the doctrine of papal infallibility, because thatdoctrine concerns ex cathedradefinitions, and nothing Pope Francis has said amounts to such adefinition (as Cardinal Fernández, Prefect of the DDF, hasexplicitly acknowledged). Butit refutes thosewho claim that all papalteaching on faith and morals is infallible, and those who hold that, even ifnot all such teaching is infallible, no pope has actually taught error. For that reason alone, Dignitas Infinita is a document of historic significance, albeitnot for the reasons Pope Francis or Cardinal Fernández would have intended.

Dignity and the death penalty

The otherproblem with the document, I have said, concerns the premise with which itbegins. That premise is referred to inits title, and it is stated in its opening lines as follows:

Every human person possesses aninfinite dignity, inalienably grounded in his or her very being, which prevailsin and beyond every circumstance, state, or situation the person may everencounter. This principle, which isfully recognizable even by reason alone, underlies the primacy of the humanperson and the protection of human rights… [Thus] theChurch… always insist[s] on “the primacy of the human person and the defense ofhis or her dignity beyond every circumstance.”

The moststriking part of this passage – indeed, I would say the most shocking part ofit – is the assertion that human dignity is infinite. I will come back to that. But first note the other aspects of itsteaching. The Declaration implies thatthis dignity follows from human natureitself, rather than from grace. Thatis implied by its being fully knowable by reason alone (as opposed to specialdivine revelation). It is ontological rather than acquired innature, reflecting what a human being israther than what he or she does. Forthis reason, it cannot be lost no matter what one does, in “every circumstance,state, or situation the person may ever encounter.” And again, the dignity human beings are saidin this way to possess is also claimed to be infinite in nature.

It is nosurprise, then, that the Declaration should later go on to say what it does aboutthe death penalty. According to PopeFrancis’s revision of the Catechism, the death penalty is “an attack on theinviolability and dignity of the person.” But Dignitas Infinita saysthis dignity exists in “everycircumstance, state, or situation the person may ever encounter.” Thatimplies that it is retained no matter what evil the person has committed, andno matter how dangerous he is to others. Thus, if we must “always insist on…the primacy of the human person and the defense of his or her dignity beyond every circumstance,” it wouldfollow that the death penalty would be impermissible in every circumstance.

This aloneentails that there is something wrong with the Declaration’s premises. For it is, again, the infallible teaching ofscripture and all previous popes that the death penalty can under somecircumstances be justifiable. Hence, ifthe Declaration’s teaching on human dignity implies otherwise, it is that teachingthat is flawed, not scripture and not two millennia of consistent papal teaching.

There isalso the problem that, in defense of its conception of human dignity, theDeclaration appeals to scriptural passages from, among other places, Genesis,Exodus, Deuteronomy, and Romans. But allfour of these books contain explicit endorsements of capital punishment! (See ByMan Shall His Blood Be Shed for detailed discussion.) Hence, their conception of human dignity isclearly not the same as that of theDeclaration. Perhaps the defender of theDeclaration will suggest that these scriptural texts erred on the specifictopic of capital punishment. One problemwith that is that the Church holds that scripture cannot teach error on amatter of faith or morals. So, thisattempt to get around the difficulty would be heterodox. But another problem is that this move wouldundermine the Declaration’s own use of these scriptural texts. For if Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy, andRomans are wrong about something as serious the death penalty, why should we believethey are right about anything else, such as human dignity?

At thispoint the defender of the Declaration might suggest that we aremisunderstanding these scriptural passages if we think they support capitalpunishment. One problem with this suggestionis that it is asinine on its face. Jewish and Christian theologians alike have for millennia consistentlyunderstood the Old Testament to sanction capital punishment, and the Church hasalways understood both the Old Testament passages and Romans to sanctionit. To pretend that it is only now thatwe finally understand them accurately defies common sense (and rests on utterlyimplausible arguments, as Bessette and I show in our book). But it also contradicts what the Church hassaid about its own understanding of scripture. The Church claims that on matters of scriptural interpretation, no oneis free to contradict the unanimous opinion of the Fathers or the consistentunderstanding of the Church over millennia. And the Fathers and consistent tradition of the Church hold that scripture teaches that the death penaltycan under some circumstances be licit. (See the book for more about this subject too.)

Infinite dignity?

But evenputting all of that aside, attributing “infinitedignity” to human beings is highly problematic. If we are speaking strictly, it is obvious that only God can be said to have infinitedignity. Dignitas conveys “worth,” “worthiness,” “merit,” “excellence,”“honor.” Try replacing “dignity” withthese words in the phrase “infinite dignity,” and ask whether the result can beapplied to human beings. Do human beingshave “infinite merit,” “infinite excellence,” “infinite worthiness”? The very idea seems blasphemous. Only God can have any of these things.

Or considerthe attributes that impart special dignity to people, such as authority,goodness, or wisdom, where the more perfectly they manifest these attributes,the greater is their dignity. Can humanbeings be said to possess “infinite authority,” “infinite goodness,” or“infinite wisdom”? Obviously not, andobviously it is only God to whom these things can be attributed. So, how could human beings have infinitedignity?

Aquinas makesseveral relevant remarks. He tells usthat “the equality of distributive justice consists in allotting various thingsto various persons in proportion to their personal dignity” (Summa Theologiae II-II.63.1). Naturally, that implies that some people havemore dignity than others. So, how could all human beings have infinitedignity (which would imply that none has more than any other)? He also says that “by sinning man departsfrom the order of reason, and consequently falls away from the dignity of hismanhood” (Summa Theologiae II-II.64.2). But if a person can lose his dignity, how canall people have infinite dignity?

Some willsay that what Aquinas is talking about in such passages is only acquireddignity rather than ontological dignity – that is to say, dignity that reflectswhat we do or some special status we contingently come to have (which canchange), rather than dignity that reflects what we are by nature. But that will not work as an interpretationof other things Aquinas says. Forinstance, he notes that “the dignity of the divine nature excels every otherdignity” (Summa Theologiae I.29.3). Obviously, he is talking about God’sontological dignity here. And naturally,God has infinite dignity if anything does. So if his ontological dignity excels ours, how could we possibly haveinfinite ontological dignity?

Aquinas alsowrites:

Now it is more dignified for a thingto exist in something more dignified than itself than to exist in its ownright. And so by this very fact thehuman nature is more dignified in Christ than in us, since in us it has its ownpersonhood in the sense that it exists in its own right, whereas in Christ itexists in the person of the Word. (Summa Theologiae III.2.2,Freddoso translation)

Now, if thedignity of human nature is increased by virtue of its being united to Christ inthe Incarnation, how could it already be infinite by nature? Then there is the fact that Aquinas explicitly denies that human dignity isinfinite:

But no mere man has the infinitedignity required to satisfy justly an offence against God. Therefore there hadto be a man of infinite dignity who would undergo the penalty for all so as tosatisfy fully for the sins of the whole world. Therefore the only-begotten Word of God, trueGod and Son of God, assumed a human nature and willed to suffer death in it soas to purify the whole human race indebted by sin. (De Rationibis Fidei, Chapter7)

To be sure,Aquinas also allows that there is a sensein which some things other than God can have infinite dignity, when he writes:

From the fact that (a) Christ’s humannature is united to God, and that (b) created happiness is the enjoyment ofGod, and that (c) the Blessed Virgin is the mother of God, it follows that theyhave a certain infinite dignity that stems from the infinite goodness which isGod. (Summa Theologiae I.25.6,Freddoso translation)

But notethat the infinite dignity in question derives from a certain special relation to God’s infinite dignity– involving the Incarnation, the beatific vision, and Mary’s divine motherhoodrespectively – and not from humannature as such.

Relevant tooare Aquinas’s remarks on the topic of infinity. He says that “besides God nothing can be infinite,” for “it is againstthe nature of a made thing to be absolutely infinite” so that “He cannot makeanything to be absolutely infinite” (SummaTheologiae I.7.2). How, then, could human beings by nature haveinfinite dignity?

Some mightrespond by saying that Aquinas is not infallible, but that would miss thepoint. For it is not just that Aquinas’stheology has tremendous authority within Catholicism (though it does have that,and that is hardly unimportant here). Itis that he is making points from Catholic teaching itself about the nature ofdignity, the nature of human beings, and the nature of God that make it highlyproblematic to speak of human beings as having “infinite dignity.” It is no good just to say that he is wrong. Thedefender of the Declaration owes us an argument showing that he is wrong, or showing that talk of “infinitedignity” can be reconciled with what he says.

Possible defenses?

Onesuggestion some have made on Twitter is that further remarks Aquinas makesabout infinity can resolve the conflict. For in the passage just quoted, he also writes:

Things other than God can berelatively infinite, but not absolutely infinite. For with regard to infinite as applied tomatter, it is manifest that everything actually existing possesses a form; andthus its matter is determined by form. But because matter, considered as existing under some substantial form,remains in potentiality to many accidental forms, which is absolutely finitecan be relatively infinite; as, for example, wood is finite according to itsown form, but still it is relatively infinite, inasmuch as it is inpotentiality to an infinite number of shapes. But if we speak of the infinite in referenceto form, it is manifest that those things, the forms of which are in matter,are absolutely finite, and in no way infinite. If, however, any created forms are notreceived into matter, but are self-subsisting, as some think is the case withangels, these will be relatively infinite, inasmuch as such kinds of forms arenot terminated, nor contracted by any matter. But because a created form thus subsisting hasbeing, and yet is not its own being, it follows that its being is received andcontracted to a determinate nature. Henceit cannot be absolutely infinite. (Summa TheologiaeI.7.2)

What Aquinasis saying here is that there is a sense in which matter is relatively infinite, and a sense in which an angel is relatively infinite. The sense in which matter is relativelyinfinite is that it can at least in principle take on, successively, one formafter another ad infinitum. The sense in which an angel is relativelyinfinite is that it is not limited by matter.

But thereare several problems with the suggestion that this passage can help us to makesense of the notion that human beings have “infinite dignity.” First, Aquinas explicitly says that things “theforms of which are in matter, are absolutelyfinite, and in no way infinite.” For example, while the matter that makes up a particular tree is relatively infiniteinsofar as it can take on different forms adinfinitum (the form of a desk, the form of a chair, and so on) the tree itself qua having the form of a tree isin no way infinite. Now, a human beingis, like a tree, a composite of form and matter. Hence, Aquinas’s remarks here would implythat, even if the matter that makes up the body is relatively infinite insofaras it can successively take on different forms ad infinitum, the human being himself is not in any wayinfinite. Obviously, then, this wouldtell against taking human nature tobe even relatively infinite in its dignity.

Furthermore,it’s not clear how the specific examples Aquinas gives are supposed to berelevant to the question at hand in the first place. The sense in which he says matter isrelatively infinite is, again, that it can take on different forms successivelyad infinitum – first one form, then asecond, then a third, and so on. But ofcourse, at any particular point in time, matter does not have an infinite numberof forms. So, how would this provide amodel for human beings having “infinite dignity”? Is the idea that they have only finitedignity at any particular point in time, but will keep having it at laterpoints in time without end? Surely thatis not what is meant by “infinite dignity.” It would entail that even something with the least dignity possible atany particular point in time would have “infinite dignity” as long as it simplypersisted with that minimal dignity forever!

Nor does theangel example help. Again, the sense in which angels are relativelyinfinite, Aquinas says, is that they are not limited by matter. But human beings are limited by matter. So, thisis no help in explaining how we could be even relatively infinite in dignity.

Another,sillier suggestion some have made on Twitter is that we can make sense of humanbeings having “infinite dignity” in light of set theory, which tells us thatsome infinities can be larger than others. The idea seems to be that while God has infinite dignity, we too canintelligibly be said to have it, so long as God’s dignity has to do with alarger infinity than ours.

The problemwith this is that the “infinity” that is attributed to God and to his dignity(and to human dignity, for that matter) has nothing to do with the infinitiesstudied by set theory. Set theory isabout collections of objects (such as numbers), which might be infinite insize. But when we say that God isinfinite, we’re not talking about a collection any kind. We’re not saying, for example, that God’sinfinite power has something to do with him possessing an infinite collectionof powers. What is meant is merely thathe has causal power to do or to make whatever is intrinsically possible. And his infinite dignity too has nothing todo with any sort of collection (such as an infinitely large collection of unitsof dignity, whatever that would mean). Set theory is simply irrelevant.

Anotherdefense that has been suggested is to appeal to Pope St. John Paul II’s havingonce used the phrase “infinite dignity” in anAngelus address in 1980. Indeed, the Declaration itself makes note of this. But there are several problems here. First, John Paul II’s remark was merely apassing comment made in the course a little-known informal address of littlemagisterial weight that was devoted to another topic. It was not a carefully worded formaltheological treatment of the nature of human dignity, specifically. Nor did John Paul put any special emphasis onthe phrase or draw momentous conclusions from it, the way the new Declarationdoes. For example, he never concludedthat, since human dignity is “infinite,” the death penalty must be ruled outunder every circumstance. On thecontrary, despite his strong personal opposition to the death penalty, healways acknowledged that there could be circumstances where it was permissible,and that that was the Church’s traditional teaching. There is no reason whatsoever to take theAngelus address reference to be anything more than a loosely wordedoff-the-cuff remark. Moreover, even ifit were more than that, that wouldnot make the problems I’ve been setting out here magically disappear.

Some havesuggested that the Declaration’s remark about the death penalty does not infact amount to saying that capital punishment is intrinsically wrong. What it entails, they claim, is only that itis always intrinsically contrary to human dignity. But that, they say, leaves it open that itmay sometimes be permissible to do what is contrary to human dignity.

But thereare two reasons why this cannot be right. First, Dignitas Infinita doesnot say that what violates our dignity is unacceptable except when such-and-such conditions hold. On the contrary, it says that the Church “always insist[s] on… the defense of [thehuman person’s] dignity beyond everycircumstance.” It says that man’s“infinite dignity” is “inviolable,”that it “prevails in and beyond everycircumstance, state, or situation the person may ever encounter,” and that our respect for it must be “unconditional.” It repeatedlyemphasizes that “circumstances” are irrelevant to what a respect fordignity requires of us, and it does so preciselybecause it claims that our dignity is “infinite.” Asserting that human dignity has such radical“no exceptions” implications is the wholepoint of the Declaration, the whole point of its making a big deal of thephrase “infinite dignity.”

Second, theDeclaration makes a special point of lumping in the death penalty with evilssuch as “murder, genocide, abortion, [and] euthanasia.” It says: “Here,one should also mention the death penalty, for this also violates the inalienable dignity of every person, regardless of the circumstances.” Obviously, if the death penalty really doesviolate human dignity under every circumstance in just the way murder, genocide, abortion, euthanasia, etc. do,then it is no less absolutely ruled out than they are. And obviously, the Declaration would notallow us to say that there are cases where murder, genocide, abortion, andeuthanasia might be allowable despite their being affronts to human dignity.

Hyperbole?

The bestdefense that some have made of the Declaration is that the phrase “infinitedignity” is mere hyperbole. But thoughthis is the best defense, that doesnot make it a good defense. First of all, magisterial documents shoulduse terms with precision. This is especially true of a document comingfrom the DDF, whose job is precisely to clarifymatters of doctrine. It is simplyscandalous for a document intended to clarify a doctrinal matter – especially onethat we are told has been in preparation for years – to deploy a key theological term in a loose and potentiallyhighly misleading way (and, indeed, to put special emphasis on this loosemeaning, even in the very title of the document!)

But second,the idea that the phrase is meant as mere hyperbole is simply not a natural readingof the Declaration. For it is not justthat special emphasis is put on the phrase itself. It is also that special emphasis is put onthe radical implications of thephrase. We are told that it is preciselybecause human dignity is “infinite”that the moral conclusions asserted by the Declaration hold “beyond all circumstances,” “beyond every circumstance,” “in all circumstances,” “regardless of the circumstances,” and soon. If you don’t take the “infinite”part seriously, then you lose the grounds for taking the “beyond allcircumstances” parts seriously. They gohand in hand. Hence, the “hyperbole”reading simply undermines the whole point of the document.

That thisextreme language of man’s “infinitedignity” has now led the pope to condemn the death penalty in an absolute way – and thereby to contradictscripture and all previous papal teaching on the subject – shows just how graveare the consequences of using theological language imprecisely. And this may not be the end of it. Asked at a pressconference on the Declaration about the implications of man’s“infinite dignity” for the doctrine of Hell, Cardinal Fernández did not denythe doctrine. But he also said: “’Withall the limits that our freedom truly has, might it not be that Hell is empty?’This is the question that Pope Francis sometimes asks.” Asked aboutthe Catechism’s teaching that homosexual desire is “intrinsically disordered,”the cardinal said: “It’s a very strong expression, and it needs to be explaineda great deal. Perhaps we could find anexpression that is even clearer, to understand what we mean… But it is truethat the expression could find other more suitable words.” When churchmen put special emphasis on theidea that human dignity is infinite,then there is a wide range of traditional Catholic teaching that they are boundto be tempted to soften or find some way to work around.

High-flownrhetoric about human dignity has, in any event, always been especially prone toabuse. As Allan Bloom once wrote, “thevery expression dignity of man, evenwhen Pico della Mirandola coined it in the fifteenth century, had a blasphemousring to it” (The Closing of the AmericanMind, p. 180). Similarly, JacquesBarzun pointed out that “[Pico’s] word dignitycan of course be interpreted as flouting the gospel’s call to humility and denyingthe reality of sin. Humanism isaccordingly charged with inverting the relation between man and God” (From Dawn to Decadence, p. 60).

Somehistorians would judge this unfair to Pico himself, but my point is not abouthim. Rather, it is about how modernpeople in general, from the Renaissance onward, have gotten progressively moredrunk on the idea of their own dignity – and, correspondingly, less and lesscognizant of the fact that what is most grave about sin is not that itdishonors us, but that it dishonors God. This, and not their owndignity, is what modern people most needreminding of. Hence, while it is notwrong to speak of human dignity, one must be cautious and always put the accenton the divine dignity rather than onour dignity. I submit that sticking aword like “infinite” in front of the latter accomplishes the reverse of this.

And I submitthat a sure sign that the rhetoric of human dignity has now gone too far isthat it has led the highest authorities in the Church to contradict theteaching of the word of God itself (on the topic of the death penalty). Such an error is possible whenpopes do not speak ex cathedra. But it is extremelyrare, and always gravely scandalous.

April 10, 2024

Western civilization's immunodeficiency disease

Liberalismis to the social order what AIDS is to the body. By relegating the truths of natural law anddivine revelation to the private sphere, it destroys the immune system of thebody politic, opening the way to that body’s being ravaged by moral decay andideological fanaticism. I develop thistheme in anew essay over at Postliberal Order.

Liberalismis to the social order what AIDS is to the body. By relegating the truths of natural law anddivine revelation to the private sphere, it destroys the immune system of thebody politic, opening the way to that body’s being ravaged by moral decay andideological fanaticism. I develop thistheme in anew essay over at Postliberal Order.

April 2, 2024

Ed Piskor (1982-2024)

This week, cartoonistEd Piskor committed suicide in the wake of the relentless online pillorying andovernight destruction of his career that followed upon allegations of sexual misconduct,of which he insisted he was innocent. Piskor’s work was not really to my taste,but I often enjoyed the CartoonistKayfabe YouTube channel he co-hosted. I was always impressed by the manifestlove, respect, and appreciation he showed for the great comic book artists ofthe past. These are attractive and admirable attitudes to take toward thosefrom whom one has learned.

This week, cartoonistEd Piskor committed suicide in the wake of the relentless online pillorying andovernight destruction of his career that followed upon allegations of sexual misconduct,of which he insisted he was innocent. Piskor’s work was not really to my taste,but I often enjoyed the CartoonistKayfabe YouTube channel he co-hosted. I was always impressed by the manifestlove, respect, and appreciation he showed for the great comic book artists ofthe past. These are attractive and admirable attitudes to take toward thosefrom whom one has learned.Piskor’ssuicide note is heartbreaking, and includes this passage:

I have no friends in this life anylonger. I’m a disappointment to everybody who liked me. I’m a pariah. Newsorganizations at my door and hassling my elderly parents. It’s too much.Putting our addresses on tv and the internet. How could I ever go back to mysmall town where everyone knows me? Some good people reached out and tried tohelp me through this whole thing but I’m just not strong enough. Theinstinctual part of my brain knows that I’m no longer part of the tribe. I’mexiled and banished. I’m giving into my instincts and fighting them at the sametime. Self preservation has lost out.

This episodevividly illustrates how diabolical is the moment through which we are currentlyliving, when the lust to defame others and stir up a mob against them – always atemptation to which human beings are prone – has been massively exacerbated bysocial media. I don’t know if Piskor was indeed innocent, but neither do thosewho hounded him to the point where he lost hope. May God have mercy on his souland on his family.

The illusion of AI

My essay “TheIllusion of Artificial Intelligence” appears in thelatest issue of the Word on Fire Institute’s journal Evangelization & Culture.

My essay “TheIllusion of Artificial Intelligence” appears in thelatest issue of the Word on Fire Institute’s journal Evangelization & Culture.

March 29, 2024

Wishful thinking about Judas

In a recentarticle at Catholic Answers titled “Hopefor Judas?” Jimmy Akin tells us that though he used to findconvincing the traditional view that Judas is damned, it now seems to him that “wedon’t have conclusive proof thatJudas is in hell, and there is still a ray of hope for him.” But there is a difference between hope andwishful thinking. And with all duerespect for Akin, it seems to me that given the evidence, the view that Judasmay have been saved crosses the line from the former to the latter.

In a recentarticle at Catholic Answers titled “Hopefor Judas?” Jimmy Akin tells us that though he used to findconvincing the traditional view that Judas is damned, it now seems to him that “wedon’t have conclusive proof thatJudas is in hell, and there is still a ray of hope for him.” But there is a difference between hope andwishful thinking. And with all duerespect for Akin, it seems to me that given the evidence, the view that Judasmay have been saved crosses the line from the former to the latter.Scriptural evidence

The reasonit has traditionally been held that Judas is in hell is that this seems to bethe clear teaching of several scriptural passages, including the words ofChrist himself. In Matthew 26:24, Jesussays of Judas: “Woe to that man by whom the Son of man is betrayed! It would have been better for that man if hehad not been born” (RSV translation). (Mark 14:21 records the same remark.) It is extremely difficult at best to see howthis could possibly be true of someone who repented and was saved. It makes perfect sense, though, if Judas wasdamned. Matthew also tells us thatJudas’s very last act was to commit suicide (27:5), which is mortally sinful.

The evidenceof John’s gospel seems no less conclusive. Praying to the Father about his disciples, Jesus, once again referringto Judas, says that “none of them is lost but the son of perdition”(17:12). It is, needless to say,extremely hard to see how Judas could be “lost” and of “perdition” and yet besaved.

Then thereis the Acts of the Apostles. It reportsthat Peter, referring to Judas’s death and the need to replace him, said: “Forit is written in the book of Psalms, ‘Let his habitation become desolate, andlet there be no one to live in it’ and ‘His office let another take’”(1:20). This implies the opposite of ahappy fate for Judas, and a later verse confirms this pessimisticjudgment. We are told that Matthias wasselected “to take the place in this ministry and apostleship from which Judasturned aside, to go to his own place” (1:25). As Haydock’scommentary notes, the reference appears to be “to his own place ofperdition, which he brought himself to” (p. 1435).

Commentingon Christ’s remark in Matthew 26:24, Akin suggests that it may have beenintended as a warning rather than a prediction. On this interpretation, Jesus was merely saying that it would be betterfor his betrayer not to have been born ifhe does not repent. But this leavesit open that Judas did indeed repent. And in fact, Akin claims, we have evidence that Judas repented in thevery next chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, which tells us:

When Judas, his betrayer, saw that hewas condemned, he repented and brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the chiefpriests and the elders, saying, “I have sinned in betraying innocent blood.” (27: 3-4)

But thereare several problems with this argument. The first is that it simply is not plausible on its face to suppose thatChrist’s words were meant merely as a warning rather than a prediction aboutJudas’s actual fate. That it would bebetter for the damned not to have been born is true of everyone who might fail to repent – you, me, Judas, and for thatmatter, Peter, who also went on to betray Jesus (and who, we know, did indeedrepent). And yet Christ does not make thisremark about Peter or about anyone else, but only about Judas. Theobvious implication is that the words apply to Judas in a way they do not applyto anyone else, and that can only be the case if he was in fact damned.

A secondproblem is that Akin ignores the other relevant biblical passages. In John’s Gospel, Christ says that Judas is“lost” and a “son of perdition.” Thoseare peremptory remarks about what isthe case, not about what would be thecase if Judas did not repent. Moreover, he says these things to the Father, not to Judas or to anyother disciple. Hence they can hardly besaid to be warnings to anyone. Thenthere are Peter’s remarks in Acts, which imply an unhappy fate for Judas andwere made after Judas’s death, sothat they too cannot be mere warnings about what would happen if he did notrepent.

A thirdproblem is that the passage cited by Akin has traditionally been understood tobe attributing to Judas a merely natural regret for what he had done, not thesupernatural sorrow or perfect contrition that would be necessary forsalvation. This is evidenced by whathappens immediately after the passage cited by Akin: “They said [to Judas], ‘Whatis that to us? See to it yourself.’ And throwing down the pieces of silver in thetemple, he departed; and he went and hanged himself” (27: 4-5). As Haydock’s commentary notes, Pope St. Leoremarks, accordingly, that Judas showed only “a fruitless repentance,accompanied with a new sin of despair” (p. 1311). Haydock notes that St. John Chrysostom also interpretsthe passage from Matthew as attributing only an imperfect repentance to Judas.

To be sure, Akinremarks that “suicide does not always result in hell because a person may notbe fully responsible for his action due to lack of knowledge, or psychologicalfactors, and because ‘in ways known to him alone,’ God may help the person torepent.” That is true, but it does notfollow that we have any serious grounds for doubting that Judas’s suicide, specifically, resulted in damnation. For one thing, there is no actual evidence from scripture that Judasfound sincere repentance just before the moment of death. The very idea is sheer ungrounded speculationat best. But for another thing, and as we’vealready seen, there are scripturalpassages that afford positive evidence that Judas was in fact damned. And again, that is how they havetraditionally been interpreted.

Evidence from the tradition

Laterauthorities reiterate this clear indication of scripture that Judas isdamned. We’ve already noted that PopeSt. Leo the Great and St. John Chrysostom do so. Leo elaborates on the themeas follows:

To this forgiveness the traitor Judascould not attain: for he, the son of perdition, at whose right the devil stood,gave himself up to despair before Christ accomplished the mystery of universalredemption. For in that the Lord diedfor sinners, perchance even he might have found salvation if he had nothastened to hang himself. But that evilheart, which was now given up to thievish frauds, and now busied withtreacherous designs, had never entertained anything of the proofs of theSaviour's mercy… The wicked traitor refused to understand this, and tookmeasures against himself, not in the self-condemnation of repentance, but inthe madness of perdition, and thus he who had sold the Author of life to Hismurderers, even in dying increased the amount of sin which condemned him.

Similarly,in The City of God, St. Augustine writes:

Do we justly execrate the deed ofJudas, and does truth itself pronounce that by hanging himself he ratheraggravated than expiated the guilt of that most iniquitous betrayal, since, bydespairing of God's mercy in his sorrow that wrought death, he left to himselfno place for a healing penitence? … For Judas, when he killed himself, killed awicked man; but he passed from this life chargeable not only with the death ofChrist, but with his own: for though he killed himself on account of his crime,his killing himself was another crime. (Book I, Chapter 17)

It is truethat Origen and St. Gregory of Nyssa held out hope that Judas repented. But these Fathers also famously flirted withuniversalism, which the Church has since condemned, and this renders suspect theirunderstanding of the scriptural passages relevant to this particular topic.

In DeVeritate, St. Thomas Aquinas writes:

In the case of Judas, the abuse ofgrace was the reason for his reprobation, since he was made reprobate becausehe died without grace. Moreover, thefact that he did not have grace when he died was not due to God’s unwillingnessto give it but to his unwillingness to accept it – as both Anselm and Dionysiuspoint out. (Question Six, Article 2. The context is Aquinas’s consideration of anobjection to a thesis on predestination that he defends in the article. But the lines quoted reflect assumptions heshares in common with his critic.)

The Catechismof the Council of Trent promulgated by Pope St. Pius V, in itstreatment of penance, says: “[Some] give themselves to such melancholy andgrief, as utterly to abandon all hope of salvation… Such certainly was thecondition of Judas, who, repenting,hanged himself, and thus lost soul and body” (p. 264). And in its treatment of the priesthood, theCatechism says:

Some are attracted to the priesthoodby ambition and love of honors; while there are others who desire to beordained simply in order that they may abound in riches… They derive no otherfruit from their priesthood than was derived by Judas from the Apostleship,which only brought him everlasting destruction. (p. 319)

The Churchhas also never prayed for Judas’s soul in her formal worship. On the contrary, the traditional liturgy forHoly Thursday containsthe following prayer:

O God, from whom Judas received thepunishment of his guilt, and the thief the reward of his confession, grant us theeffect of Thy clemency: that as our Lord Jesus Christ in His passion gave toeach a different recompense according to his merits, so may He deliver us fromour old sins and grant us the grace of His resurrection. Who liveth and reigneth.

Furtherauthorities could be cited, but this suffices to make the point that it hasbeen the common view in the history of the Church that Judas is in hell. Indeed, so confident has the Church beenabout this that the supposition that Judas is damned has traditionally beenreflected even in her catechesis and herworship.

Now, thiswould be extremely odd if there really were any serious grounds for hope thatJudas is saved. As the Code of Canon Lawfamously reminds us, “the salvation of souls… must always be the supreme law inthe Church” (1752). And Christ famouslycommanded us to pray for our enemies (Matthew 5:44). How then, consistent with Christ’s teachingand with her supreme law, could the Church for two millennia fail to pray forJudas’s soul if there really were any hope for his salvation? The Church also assures sinners that there isno sin, no matter how grievous, that cannot be forgiven if only one is trulyrepentant. What better illustration ofthis could there possibly be than the repentance of Christ’s own betrayer – if indeed he really had repented? And yet the Church has not only never heldJudas up as a sign of hope, but on the contrary has pointed to him as anillustration of what awaits those who refuse Christ’s mercy.

The only evidencefrom the tradition Akin cites in defense of his own position are some remarksfrom Pope St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI. In particular, he notes that John Paul oncestated that it is not “certain” from Matthew 26:24 that Judas is damned. And Benedict, Akin notes, once remarked thatit is “not up to us” to make a judgement about Judas’s suicide.

But this ishardly a powerful response to the case from scripture and tradition that I’vesummarized. For one thing, John PaulII’s remark was not made in the context of a magisterial document, but ratherin the interview book Crossing theThreshold of Hope. It is merely theexpression of his opinion as a private theologian. Moreover, it is merely an assertion about Matthew 26:24 and failsto address the considerations that indicate that the passage does indeed show that Judas isdamned. Nor does John Paul address theother relevant scriptural passages, or the evidence from the later tradition.

BenedictXVI’s comment was made in the course of a generalaudience, which has a low degree of authority compared to therelevant passages from scripture, the Fathers, and the rest of the traditioncited above. Moreover, Benedict alsoacknowledges that “Jesus pronounces a very severe judgement on [Judas],” andgoes on to contrast Judas’s fate with Peter’s:

After his fall Peter repented andfound pardon and grace. Judas alsorepented, but his repentance degenerated into desperation and thus becameself-destructive. For us it is aninvitation to always remember what St Benedict says at the end of the fundamentalChapter Five of his “Rule”: “Never despair of God's mercy”.

Needless tosay, these remarks from Benedict tend to supportrather than undermine the traditional view that Judas’s suicide shows that hehad succumbed to the sin of despair.

“So you’re telling me there’s achance?”

It may seemfrivolous, when dealing with so serious a subject, to allude to a crude comedyfilm like Dumb and Dumber. But it contains a line that is so apt that Iwill take the risk. In a famous scene, JimCarrey’s character asks a girl he has a crush on how likely it is that shemight someday reciprocate his feelings. Shesays the odds are “one out of a million.” To which he replies: “So you’re telling methere’s a chance! YEAH!!”

What she actuallymeans, of course, is that the odds are so extremely low that, practically speaking,there is no chance at all. But thelesson he draws is that, because she didn’tquite say that there is zero chance,he has reasonable grounds for hope.

Jimmy Akinis a smart guy for whom I have nothing but respect, so I am certainly notlikening him to the Jim Carrey character! But on this particular issue, it seems to me that he, like others whohave resisted the traditional view that Judas is damned, are committing anerror similar to the one that character commits. Because, they suppose, the evidence fromscripture and tradition doesn’t strictlyentail that Judas is damned, they judge that it is reasonable to hope thathe is not. In effect, they look at whatthe evidence is saying and respond: “So you’re telling me there’s a chance!” And like Carrey’s character, they thereby entirelymiss the point.

Jesuit Britain?

Did SpanishScholastic thinkers influence British liberalism? Youcan now access my Religion andLiberty review of

Projectionsof Spanish Jesuit Scholasticism on British Thought: New Horizons in Politics,Law, and Rights

, edited by Leopoldo J. Prieto López and José LuisCendejas Bueno.

Did SpanishScholastic thinkers influence British liberalism? Youcan now access my Religion andLiberty review of

Projectionsof Spanish Jesuit Scholasticism on British Thought: New Horizons in Politics,Law, and Rights

, edited by Leopoldo J. Prieto López and José LuisCendejas Bueno.

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 335 followers