The metaphysics of individualism

Modern moraldiscourse often refers to “persons” and to “individuals” as if the notions weremore or less interchangeable. But thatis not the case. In his book Three Reformers: Luther, Descartes, Rousseau(especially in chapter 1, section 3), Jacques Maritain notes several importantdifferences between the concepts, and draws out their moral and socialimplications.

Modern moraldiscourse often refers to “persons” and to “individuals” as if the notions weremore or less interchangeable. But thatis not the case. In his book Three Reformers: Luther, Descartes, Rousseau(especially in chapter 1, section 3), Jacques Maritain notes several importantdifferences between the concepts, and draws out their moral and socialimplications.Traditionally,in Catholic philosophy, a person is understood to be a substance possessing intellectand will. Intellect and will, in turn,are understood to be immaterial. Hence,to be a person is ipso facto to beincorporeal – wholly so in the case of an angel, partially so in the case of ahuman being. And qua partiallyincorporeal, human beings are partially independent of the forces that governthe rest of the material world.

Individuality,meanwhile, is in the case of physical substances a consequence precisely oftheir corporeality rather than theirincorporeality. For matter, as Aquinasholds, is the principle of individuation with respect to the members of speciesof corporeal things. Hence it isprecisely insofar as human beings are corporeal that they are subject to theforces that govern the rest of the material world.

With a wholly corporeal living thing like aplant or a non-human animal, its good is subordinate to that of the species towhich it belongs, as any part is subordinate to the whole of which it is a part. Such a living thing is fulfilled insofar asit contributes to the good and continuance of that whole, the species kind ofwhich it is an instance. By contrast, aperson, qua incorporeal, is a complete whole in itself. And itshighest good, in which alone it can find its fulfilment, is God, the ultimateobject of the intellect’s knowledge and the will’s desire.

Insofar aswe think of human beings as persons,then, we will tend to conceive of what is good for them in terms of whatfulfills their intellects and wills, and thus (when the implications of thatare properly understood) in theological terms. But insofar as we think of them as individuals,we will tend to conceive of what is good for them in terms of what isessentially bodily – material goods, pleasure and the avoidance of pain,emotional wellbeing, and the like. However, we will also be more prone to see their good as something thatmight be sacrificed for the whole of which they are parts.

Maritainputs special emphasis on the implications of all this for politicalphilosophy. The common good is more thanmerely the aggregate of the goods enjoyed by individuals. But because human beings are persons, and notmerely individuals, the common good is also not to be conceived of merely asthe good of society as a whole and not of its parts. Rather, “it is, so to speak, a good common to the whole and the parts”(p. 23).

On the onehand, the political order is in one respect more perfect than the individualhuman being, for it is complete in a way the individual is not. On the other hand, in another respect theindividual human being is more perfect than the political order, because qua person he is a complete order in hisown right, and one that has a destiny beyond the temporal political realm. Hence, a just political order must reflectboth of these facts. In particular, itmust recognize that the common good to which the individual is ordered includesfacilitating, for each member of the community, the realization of hisultimate, eternal end in the hereafter. Thus,concludes Maritain, “the human city fails in justice and sins against itselfand its members if, when the truth is sufficiently proposed to it, it refusesto recognize Him Who is the Way of beatitude” (p. 24).

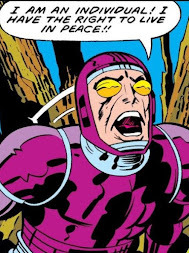

This refusalis, needless to say, characteristic of modern societies, both liberal andcollectivist. And unsurprisingly, they haveat the same time put greater emphasis on human individuality than on human personhood. Both do so insofar as they conceive of thegood primarily in economic and other material terms rather than in spiritualterms. Liberal societies, in addition,do so insofar as they conceive of these bodily goods along the lines of thesatisfaction of idiosyncratic individual preferences and emotional wellbeing. Collectivist societies, meanwhile, do soinsofar as they regard human beings, qua individuals, as apt to be sacrificedto the good of the species of which they are mere instances. (It should be no surprise, then, that Burkewould famously condemn “the dust and powder of individuality” even as hecondemned at the same time the totalitarianism of the French Revolution. For individualism and collectivism are rootedin precisely the same metaphysical error.)

Maritaincites a passage from Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange that summarizes the moral andspiritual implications of the distinction between individuality and personhood:

To develop one’s individuality is to live the egoistical life of the passions, to make oneself thecentre of everything, and end finally by being the slave of a thousand passinggoods which bring us a wretched momentary joy. Personality, on the contrary,increases as the soul rises above the sensible world and by intelligence andwill binds itself more closely to what makes the life of the spirit. The philosophers have caught sight of it, butthe saints especially have understood, that the full development of our poorpersonality consists in losing it in some way in that of God. (pp. 24-25,quoted from Garrigou-Lagrange’s Le SensCommun)

Among the paganphilosophers, perhaps none is as clear on this theme as Plotinus, who in the FifthEnnead contrasts individuality with orientation toward God: “How is it, then,that souls forget the divinity that begot them?... This evil that has befallenthem has its source in self-will… in becoming different, in desiring to beindependent… They use their freedom to go in a direction that leads away fromtheir origin.” And among the saints,none states this contrast more eloquently than Augustine, who distinguishes “twocities [that] have been formed by two loves: the earthly by the love of self,even to the contempt of God; the heavenly by the love of God, even to thecontempt of self” (City of God, BookXIV, Chapter 28). This earthly city, inits modern guise, has been built above all by individualism.

Related posts:

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 329 followers