Edward Feser's Blog, page 20

November 10, 2022

Adventures in the Old Atheism, Part VII: The influence of Kant

Immanuel Kant was, of course, not an atheist. So why devote an entry to him in this series, thereby lumping him in with the likes of Nietzsche, Sartre, Freud, Marx, Woody Allen, and Schopenhauer? In part because Kant’s philosophy, I would suggest, inadvertently did more to bolster atheism than any other modern system, Hume’s included. He was, as Nietzsche put it, a “catastrophic spider” (albeit not for the reasons Nietzsche supposed). But also in part because, like the other thinkers in this series, Kant had a more subtle and interesting attitude about religion than contemporary critics of traditional theology like the New Atheists do.

Why do I propose that Kant’s influence did even more to bolster modern atheism than Hume’s? Because Kant offered a positive alternative to the traditional metaphysics that upheld theism, whereas Hume’s critique is essentially negative. To be sure, contemporary commentators are correct to hold that it is too simple to read Hume as a mere skeptic, full stop. True, he does try to undermine traditional metaphysical views about substance, causation, the self, moral value, etc. But he also emphasizes that the hold such notions have over common sense cannot be shaken by philosophical skepticism, since they are too deeply rooted in human psychology. And for purposes of “common life,” they are indispensable. Hume’s aim is merely to clip the wings of highfalutin rationalist metaphysical speculation, not to undermine the convictions of the ordinary person.

All the same, precisely for that reason, Hume’s account of philosophy, if not of common sense, is essentially destructive. Moreover, a consistent Humean will have to take a much more modest view of natural science than contemporary atheists are wont to do – in part because of Hume’s attack on attempts to justify induction, and in part because the deliverances of modern physics are hardly less abstruse and remote from common life than the rationalist speculations he was so keen to shoot down. A Humean must also give up a rationalistic ethics, given that, as he famously holds, there is nothing contrary to reason (but only to the sentiments of the average person) to prefer that the entire world be destroyed than that one should suffer a scratch to his finger. Humean arguments entail a pessimism about the powers of human reason that doesn’t sit well with scientism or with dogmatic and triumphalist versions of atheism (even if many atheists and adherents of scientism naively suppose otherwise).

Kant, by contrast, tied his critique of traditional metaphysics to an essentially positive and optimistic view of what reason could accomplish. True, he did not think reason could penetrate into the natures of things as they are in themselves. Since that’s what traditional metaphysics claimed to do, and natural theology is grounded in such metaphysics, his position entails a critique of traditional metaphysics and natural theology. However, in Kant’s view this entailed no doubts about the rational foundations of morality or of science (which concerns the world as it appears to us rather than as it is in itself). A consistent Humean has to put natural theology, natural science, and ethics in the same boat. A consistent Kantian can leave natural theology in the boat by itself.

Ultimate explanation

All the same, Kant’s critique of natural theology did not stem from the view that it is an irrational enterprise. Quite the contrary. The New Atheist supposes that all theology reflects an insufficient respect for reason. Kant argues, by contrast, that in fact natural theology reflects an excessive confidence in the power of reason. In particular, it reflects the conviction that ultimate explanation is possible, that the world can be made intelligible through and through. Nor did Kant suppose that natural theology looked for such explanation in the crudely anthropomorphic “sky daddy” of New Atheist caricature. Here is how he describes the basic impulse behind philosophical theism in the Critique of Pure Reason:

Reason… is impelled… to seek a resting-place in the regress from the conditioned, which is given, to the unconditioned… This is the course which our human reason, by its very nature, leads all of us, even the least reflective, to adopt…

If we admit something as existing, no matter what this something may be, we must also admit that there exists something which exists necessarily. For the contingent exists only under the condition of some other contingent existence as its cause, and from this again we must infer yet another cause, until we are brought to a cause which is not contingent, and which is therefore unconditionally necessary…

Now… that which is in no respect defective, that which is in every way sufficient as a condition, seems to be precisely the being to which absolute necessity can fittingly be described. For while it contains the conditions of all that is possible, it itself does not require and indeed does not allow of any condition, and therefore satisfies… the concept of unconditioned necessity…

The concept of an ens realissimum is therefore, of all concepts of possible things, that which best squares with the concept of an unconditionally necessary being; and… we have no choice in the matter, but find ourselves constrained to hold to it…

Such, then, is the natural procedure of human reason. It… looks around for the concept of that which is independent of any condition, and finds it in that which is itself the sufficient condition of all else, that is, in that which contains all reality. But that which is all-containing and without limits is absolute unity, and involves the concept of a single being that is likewise the supreme being. (pp. 495-97, Norman Kemp Smith translation)

Reason, Kant says, cannot be satisfied as long as the explanations it posits make reference only to what is conditioned, to contingent things. Ultimateexplanation must posit the existence of something which is absolutely unconditioned or necessary. This something would be a single, unified “ens realissimum” or most real being, would be devoid of any defect, and would be the source of all other reality – it would possess “the highest causality… which contains primordially in itself the sufficient ground of every possible effect” (p. 499). Naturally, it is not the likes of Zeus or Odin that Kant has in mind, but rather the Unmoved Mover of Aristotle and Aquinas, the One of Plotinus, the Necessary Being of Leibniz, and so on.

The trouble with this sort of reasoning, Kant thinks, is not that its conclusion is false – again, he was no atheist – but rather that, given his epistemology, reason lacks the resources to transcend the empirical world and prove the existence of a necessary or unconditioned being outside it. The notion of causality, he argues, applies only within the phenomenal world, the world of things as they appear to us, whereas reasoning to a necessary being would require applying it beyond that world, to the noumenal world or things as they are in themselves. And we cannot, in his view, know the latter.

By no means does this make reasoning to such a divine first cause superstitious or otherwise foolish. After all, Kant also thinks that the notions of space and time apply only within the phenomenal world and not to things as they are in themselves. You might think it mistaken to suppose that the notions of space and time apply to things as they are in themselves, but few would regard it as superstitious, or irrational, or otherwise contemptible to do so. By the same token, there is nothing superstitious, irrational, or otherwise contemptible in the idea of a first uncaused cause, even if one supposes, with Kant, that reason is incapable of validly drawing the inference to it.

Again, in Kant’s view, it is not the abandonment of reason, but rather the attempt to fulfill reason’s ultimate ambitions, that yields natural theology. And reason will remain frustrated even in the face of Kantian attempts to show that this ambition cannot be fulfilled. It is “quite beyond our utmost efforts to satisfy our understanding in this matter” but “equally unavailing are all attempts to induce it to acquiesce in its incapacity” (p. 513).

The metaphysics of morals

“As follows from these considerations,” Kant says, “the ideal of the supreme being is nothing but a regulative principle of reason, which directs us to look upon all connection in the world as if it originated from an all-sufficient necessary cause” (p. 517). Note that Kant is not saying that this ideal is an unavoidable useful fiction, but rather that it is unavoidable and useful even if (in his view) unprovable.

Even so, he does not regard the affirmation of God’s existence as groundless. On the contrary, he famously argues that a rationale for affirming it is to be found in practical rather than pure reason, in ethics rather than in metaphysics. Just as reason seeks an ultimate explanation, so too, Kant argues in the Critique of Practical Reason, it seeks the highest good. And the highest good, he argues, would be the conjunction of moral virtue, which makes us worthy of happiness, with happiness itself.

Now, we are obligated by the moral law to try to realize this highest good. And since ought implies can, it must be possible to realize it. Yet it is obviously not realized in this life, since virtuous people often suffer and evil people often live lives of comfort and pleasure. Moreover, Kant thinks, its realization cannot be guaranteed in this life, since there is, he thinks, no inherent necessary correlation between the demands of the moral law and the causal order that governs the natural world. We can make sense of such a correlation only if we postulate a supreme being who brings the two orders into correlation (in the afterlife).

Kant does not take this to be a strict proof of God’s existence, but rather an argument to the effect that it is reasonable to affirm God’s existence. And once again, the idea is not that theism involves believing something contrary to reason, but quite the opposite. Affirming God’s existence is, in Kant’s view, precisely what is called for in order to make sense of what reason dictates in the realm of action.

The afterlife of Hume and Kant

It is widely supposed that Hume and Kant put paid to the arguments of natural theology. But their critiques largely presuppose their background views in epistemology and metaphysics. If you don’t buy those views (and I don’t) you needn’t accept their critiques. Yet Hume’s and Kant’s general epistemological and metaphysical views are hardly uncontroversial, and many who suppose their critiques of natural theology to be compelling would not accept them (if, indeed, they even know much about them).

Moreover, as I have argued, if you do accept these background views, then to be consistent you’d have to draw other conclusions that most New Atheist types would not want to draw. Again, if you accept a Humean critique of natural theology, then to be consistent you should also be skeptical about the claims of natural science and ethics to tell us anything about objective reality. And if you accept a Kantian critique of natural theology, then while you can consistently take natural science and ethics to have a rational basis, you cannot consistently treat theology with the contempt that Dawkins and Co. typically do. Hence the lessons so many have drawn from Hume’s and Kant’s critiques is not the one either of those critiques actually supports.

Related posts:

Sexual cant from the asexual Kant

Theology and the analytic a posteriori

The problem of Hume’s problem of induction

Hume, cosmological arguments, and the fallacy of composition

November 4, 2022

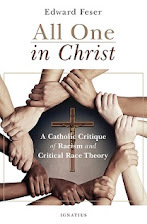

All One in Christ at Beliefnet

Recently I was interviewed at length by John W. Kennedy at Beliefnet about my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

.

Recently I was interviewed at length by John W. Kennedy at Beliefnet about my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

. Earlier reviews of and interviews about the book can be found hereand here.

November 3, 2022

The teleological foundations of human rights

My essay “The Teleological Foundations of Human Rights” appears in

The Cambridge Handbook of Natural Law and Human Rights

, edited by Tom Angier, Iain Benson, and Mark Retter and out this month. Here’s the abstract:

My essay “The Teleological Foundations of Human Rights” appears in

The Cambridge Handbook of Natural Law and Human Rights

, edited by Tom Angier, Iain Benson, and Mark Retter and out this month. Here’s the abstract: Natural law theory in the Aristotelian-Thomistic (A-T) tradition is grounded in a metaphysics of essentialism and teleology, and in turn grounds a theory of natural rights. This chapter offers a brief exposition of the metaphysical ideas in question, explains how the A-T tradition takes a natural law moral system to follow from them, and also explains how in turn the existence of certain basic natural rights follows from natural law. It then explains how the teleological foundations of natural law entail not only that natural rights exist, but also that they are limited or qualified in certain crucial ways. The right to free speech is used as a case study to illustrate these points. Finally, the chapter explains the sense in which the natural rights doctrine generated by A-T natural law theory amounts to a theory of human rights, specifically.

Follow the link to check out the table of contents and excellent roster of contributors to the volume.

October 28, 2022

Divine freedom and necessity

In a recent article, I commented on Fr. James Dominic Rooney’s critiqueof David Bentley Hart. My focus was, specifically, on Fr. Rooney’s objections to Hart’s view that God’s creation of the world follows inevitably from his nature. That position, as Rooney points out, is heretical. In the comments section at Fr. Aidan Kimel’s blog, Hart defends himself, objecting both to Rooney’s characterization of his position and to the claim that it is heretical. Let’s take a look.

In a recent article, I commented on Fr. James Dominic Rooney’s critiqueof David Bentley Hart. My focus was, specifically, on Fr. Rooney’s objections to Hart’s view that God’s creation of the world follows inevitably from his nature. That position, as Rooney points out, is heretical. In the comments section at Fr. Aidan Kimel’s blog, Hart defends himself, objecting both to Rooney’s characterization of his position and to the claim that it is heretical. Let’s take a look. First, recall the passage from Hart’s book You Are Gods that provided the basis for Fr. Rooney’s charge:

For God, deliberative liberty – any “could have been otherwise,” any arbitrary decision among opposed possibilities – would be an impossible defect of his freedom. God does not require the indeterminacy of the possible in order to be free… And in the calculus of the infinite, any tension between freedom and necessity simply disappears; there is no problem to be resolved because, in regard to the transcendent and infinite fullness of all Being, the distinction is meaningless… And it is only insofar as God is not a being defined by possibility, and is hence infinitely free, that creation inevitably follows from who he is. This in no way alters the truth that creation, in itself, “might not have been,” so long as this claim is understood as a modal definition, a statement of ontological contingency, a recognition that creation receives its being from beyond itself and so has no necessity intrinsic to itself.

End quote. Hart here says that “creation inevitably follows from who [God] is.” He denies that there is “any ‘could have been otherwise,’” any “indeterminacy of the possible,” where divine action is concerned. He says that this is consistent with the thesis that the world might not have been just “so long as” this is understood to mean that the world receives its being from something beyond it. The implication, given the preceding remarks, is that it has nothing to do with any possibility of God’s refraining from creating it.

Now, given standard philosophical and theological usage of “necessary” and cognate terms, it is clear that Hart is asserting that God creates the world of necessity. For example, in The Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s article on “Contingent and Necessary Statements,” necessity is characterized as “what must occur,” whereas contingency involves “what may or may not occur.” The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy defines “necessity” as “a modal property attributable to a whole proposition… just when it is not possible that the proposition be false.” Wuellner’s Dictionary of Scholastic Philosophydefines “necessary” as “that which cannot not-be,” “that which must be and be as it is,” and “that which must act as it does and which cannot act otherwise.” Obviously, Hart thinks God’s creation of the world must occur, given his nature. He thinks that it is not possible that the proposition that God creates the world be false. He thinks that God must act to create the world, that his act of creation cannot not-be. Hence, again, given standard usage, Hart clearly thinks that God creates the world of necessity.

I emphasize this because, in at least some of the remarks Hart makes in reply to Rooney, he seems to deny that he thinks that God creates of necessity. He asks: “[W]here did I ever suggest God was prompted by a necessity beyond himself – or even within himself?” And he says that “I’ve always maintained that ‘necessity’ is not a meaningful concept in relation to God,” and indeed that “creation is not necessary for God.” On the other hand, he also says that “creation follows necessarily from who God freely is”; that “it is impossible that God – the Good as such – would not create”; and that “God as the good cannot fail to be… diffusive” by creating. And these statements entail that God does create of necessity as the term “necessity” is standardly used. And again, the remarks in You Are Godsentail it too.

All told, then, it is clear that Hart does not deny, or at least cannot reasonably deny, that he holds that God creates the world of necessity. Rather, the most that he can try to argue (albeit, I think, unpersuasively) is that the specific sense in which he thinks that God creates of necessity is compatible with divine freedom and with Christian orthodoxy.

To be sure, there is one clear sense in which Hart thinks that God does not create of necessity, insofar as he holds that God is free of “necessitation under extrinsiccoercion,” of “a necessity beyondhimself.” Like Fr. Rooney, me, and the Christian tradition in general, Hart agrees that nothing outside of God in any way compels him to create. For that matter, there is also a sense in which Fr. Rooney, I, and the Christian tradition in general agree with Hart that God acts of necessity in somerespects. In particular, there is no disagreement with Hart when he writes: “Can God lie? Can God will evil? No and no, manifestly, because he is the infinite unhindered Good.”

There is also agreement on all sides that there is no arbitrariness in God’s willing to create the world. Hart characterizes Rooney’s position as “voluntarist,” apparently meaning that by rejecting Hart’s view that God’s nature makes it inevitable that he will create, Rooney must be committed to viewing creation as the product of a random choice with no rhyme or reason about it. But Rooney takes no such position, nor does anything he says imply it. Rooney, like the Christian tradition in general, would agree with Hart that God creates the world not arbitrarily but out of love. What is at issue is whether this makes creation inevitable.

In short, all sides agree that God is not compelled to create by anything outside him, that he cannot will evil, and that his will is not arbitrary or unintelligible. What is at issue is rather this: Is there anything internalto the divine nature that entails that God could not possibly have refrained from creating the world? Hart says there is, and Fr. Rooney and I (and, we claim, the mainstream Christian tradition in general) say that there is not.

Why does Hart think so, and why does he think his view is compatible with the tradition? In his comments at Fr. Kimel’s blog, there seem to be at least five considerations that he thinks support these claims:

1. Hart says that “‘necessity’ is not a meaningful concept in relation to God” and that “necessity cannot attach to him who is perfect infinite act.” The argument seems to be that since he is explicitly committed to these claims, he cannot fairly be accused of holding that God creates of necessity. But there are several problems with this line of defense.

First, the argument seems to boil down to mere semantic sleight of hand. Again, Hart holds that “creation inevitably follows from who [God] is,” denies that there is “any ‘could have been otherwise’” where creation is concerned, and so forth. This counts as holding that God creates of necessity given the standard philosophical and theological use of “necessity.” Hence, if Hart really is denying that he takes God to create of necessity, the denial rings true only if he is using the word in some idiosyncratic way.

Second, the claim that “‘necessity’ is not a meaningful concept in relation to God” is simply not true in the classical theist tradition within which Hart, Rooney, and I are all operating. That tradition holds, for example, that God existsof necessity insofar as he is subsistent being itself, pure actuality, and so on. Hart might respond that he is not denying that there is necessity in God in thatsense. But then, it will not do to dismiss Fr. Rooney’s criticisms on the basis of the completely general assertion that “‘necessity’ is not a meaningful concept in relation to God.”

Third, Hart is in any case not himself consistent on this point. For in his comments at Fr. Kimel’s blog, he asserts that “creation follows necessarilyfrom who God freely is,” and he compares God’s creation of the world to “a mother’s love for her child… [which] flows necessarilyfrom her nature, unimpeded by exterior conditions.” Even Hart, then, allows that there is a sense in which he is committed to the claim that God creates of necessity.

2. That last remark from Hart is part of a second line of defense. He writes:

[I]t is impossible that God – the Good as such – would not create, not because he must, but because nothing could prevent him from acting as what he is. Is a mother’s love for her child unfree because it flows necessarily from her nature, unimpeded by exterior conditions?

End quote. The argument here seems to be this. There is a sense in which a mother’s love for her child flows of necessity from her nature, but we would not for that reason judge the acts that express this love to be unfree. Similarly, if, as Hart claims, the act of creation flows of necessity from God’s nature, we shouldn’t judge that it is unfree.

But that this is too quick should be obvious from the fact that, say, a dog’s nurturing of her puppies is also necessitated by her nature – and it is unfree. Hence, there must be some additional factor in the cases of a human mother and of God that evidences that they are free in a way the dog is not. What might that be?

Well, in the case of the human mother, she could have decided not to have a child at all. True, given that she does have the child, her nature, if unimpeded (by sin or by mental illness, say), will lead her inevitably to love the child. But that’s a conditional necessity, and the antecedent could have failed to be true. Unlike the dog (which has no choice in the matter) a human being can freely decide not to have children. But analogously, even if God cannot fail to love the world if he creates it, his freedom is still manifest in the fact that he nevertheless could have refrained from creating it in the first place.

Note that this is compatible with saying that God creates the world out of love, just as it is compatible with saying that a woman might decide to have a child out of love. That she wills to express her love by having a child to whom she might show that love does not entail that it was inevitable that she would have the child. And by the same token, that God wills to express his love by creating and showing his love to his creatures does not entail that it was inevitable that he would create.

3. But in response to this, it seems that Hart would deploy a further argument. At Fr. Kimel’s blog, a reader says: “Creation is unnecessary in that it adds nothing to God. However, creation is inevitable given the boundless love of God.” And to this, Hart replies: “Precisely.” So, it seems that Hart would argue that, unlike a human mother’s love, God’s love is boundless, and that this is what makes his creative act inevitable. For God to fail to create would entail some bound or limitation on God’s love.

The problem with this is that it contradicts the reader’s first statement, to the effect that creation adds nothing to God. For if God cannot be boundless in love without creating the world, then creation does add something to God – it completes or perfects his love. This entails that God needs creation in order to be complete, perfect, unlimited, unbounded. And this is no less heretical than is the claim that God creates of necessity. Thus does the First Vatican Council teach that “there is one true and living God, creator and lord of heaven and earth, almighty, eternal, immeasurable, incomprehensible, infinite in will, understanding and every perfection” (emphasis added). Of course, Hart would not be moved by the pronouncements of a Catholic council, but the doctrine is grounded in scripture and tradition. For example, Matthew 5:48 says: “You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” It is also a consequence of God’s pure actuality, for only what has some unactualized potential could fail to be perfect.

In my review of Hart’s You Are Gods, commenting on Hart’s view that creation follows inevitably from God’s nature, I noted that “it is hard to see how this is different from the Trinitarian claim that the Son is of necessity begotten by the Father; and if it isn’t different, then creation is no less divine than the Son is.” Hart’s necessitarian view of creation is thus one of several respects in which, as I noted in the review, his position collapses into a kind of pantheism. And as Pohle and Preuss note in their manual God: His Knowability, Essence, and Attributes, against the traditional doctrine of divine perfection, it is precisely “Pantheists [who] object that ‘God plus the universe’ must obviously be more perfect than ‘God minus the universe’” (p. 188).

Now, some of Hart’s readers have objected to my characterization of him as a pantheist. But “pantheism” covers a variety of related positions, and even if Hart is not committed to everything that has been associated historically with pantheism, it does not follow that there is no reasonable construal of the term on which his position amounts to pantheism. And as I noted in a recent exchange with Hart, he has himself admitted this, saying: “The accusation of pantheism troubles me not in the least… [T]here are many ways in which I would proudly wear the title… I am quite happy to be accused of pantheism.”

But whether or not Hart thinks pantheism can be reconciled with orthodoxy, his critics do not. Hence, it will hardly do for him to try to defend the orthodoxy of his necessitarianism via lines of argument that seem to imply pantheism, since this will simply beg the question against his critics, who don’t accept pantheism any more than they accept necessitarianism.

4. But Hart has another argument that might at first glance seem to be precisely the kind that should trouble his critics:

A God who merely chooses to create – as one equally possible exercise of deliberative will among others – is either actualizing a potential beyond his nature (in which case he is not God, but a god only) or he is actualizing some otherwise unrealized potential within himself (in which case, again, he is not God, but a god only).

End quote. Given that God is pure actuality, doesn’t it follow that he cannot have potentials of either of the kinds here referred to by Hart?

But as every Thomist knows, we need to draw a distinction between active potency and passive potency. Passive potency is the capacity to be changed or altered in some way. It is passive potency or potentiality, specifically, that God utterly lacks by virtue of being pure actuality. Active potency, by contrast, is the capacity to effect a change in something else. And as Aquinas writes, active potency or potentiality is something that “we must assign to [God] in the highest degree.”

Now, I assume that Hart accepts this distinction. If he does, though, then he should realize that his argument does not succeed, because the position he rejects does not entail attributing any passive potential in God (which would indeed be problematic) but rather only active potency. And if he does not accept the distinction, then his argument simply begs the question against his critics, who do accept it.

5. Finally, Hart makes a point in defense of the orthodoxy of his position, claiming:

Not that I give a toss about Roman dogma, but the fact remains that there is no doctrinal rule regarding the metaphysical content of the claim that God creates freely… [W]hat I have written on the matter is one very venerable way of affirming divine freedom in creation.

End quote. But I already explained what is wrong with this in my previous article. For one thing, Hart is simply mistaken about Catholic doctrine. The First Vatican Council teaches:

If anyone does not confess that the world and all things which are contained in it, both spiritual and material, were produced, according to their whole substance, out of nothing by God; or holds that God did not create by his will free from all necessity, but as necessarily as he necessarily loves himself; or denies that the world was created for the glory of God: let him be anathema.

End quote. Fr. Rooney, in his own article, cited other Catholic magisterial texts. Contrary to what Hart says, then, it isin fact a matter of Catholic orthodoxy that divine freedom is not compatible with the view that creation was not “free from all necessity” so that God created the world “as necessarily as he necessarily loves himself.”

Furthermore, I also noted in my previous article that the Catholic position has deep roots in scripture and the Fathers of the Church, citing texts from Clement of Alexandria, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, Athanasius, Augustine, and Theodoret. Further evidence could be given. For example, as Aquinas notes, Ambrose teaches in De Fide II, 3: “The Holy Spirit divideth unto each one as He will, namely, according to the free choice of the will, not in obedience to necessity.” And as Fr. Rooney has noted in the course of his recent exchanges on this topic at Twitter, Maximus the Confessor also denies that necessitation is compatible with divine freedom, writing: “If you say that the will is natural, and if that what is natural is determined, and if you say that wills in Christ are natural, then you actually eliminate in him every voluntary movement” (quoted in Filip Ivanovic, “Maximus the Confessor on Freedom”).

In responding to Fr. Rooney, Hart has been dismissive of any attempt to enlist the Fathers against him. But he has not explained exactly how Rooney or I have misinterpreted them, or exactly howhis position can be reconciled with the passages we have quoted. His argument boils down to a sheer appeal to his own personal authority as a patristics scholar (never mind the fact that not all patristics scholars would agree with his interpretations). Suppose Hart had cited some text from Aquinas in an argument against me or Fr. Rooney. And suppose that Rooney or I responded by claiming that Hart had gotten Aquinas wrong, but did not explain exactly how, merely saying: “We’re Thomists, trust us.” Hart and his fans would regard this as an unserious response, and rightly so. But this sort of thing is no less unserious when Hart does it.

All told, then, it is clear that Hart has failed successfully to rebut the criticisms Fr. Rooney and I raised in our earlier articles.

October 25, 2022

It’s an overdue open thread

We’re long overdue for an open thread, so here it is. Now you can post that otherwise off-topic comment that I deleted three days, three weeks, or three months ago. Feel free to talk about whatever you like, from light cones to Indiana Jones, Duns Scotus to the current POTUS, Urdu to Wall of Voodoo. Just keep it civil and classy.

Previous open threads can be viewed here.

October 20, 2022

Divine freedom and heresy

I commend to you Fr. James Dominic Rooney’s excellent recent Church Life Journal article “The Incoherencies of Hard Universalism.” It is directed primarily at David Bentley Hart’s defense of universalism in his book That All Shall Be Saved, of which I have also been critical. Fr. Rooney sums up his basic argument as follows:

I commend to you Fr. James Dominic Rooney’s excellent recent Church Life Journal article “The Incoherencies of Hard Universalism.” It is directed primarily at David Bentley Hart’s defense of universalism in his book That All Shall Be Saved, of which I have also been critical. Fr. Rooney sums up his basic argument as follows: If it is a necessary truth that all will be saved, something makes it so. The only way it would be impossible for anyone to go to hell is,

1. that God could not do otherwise than cause human beings to love him or

2. that human beings could not do otherwise than love God.

3. There is no third option.

Both of these options, however, entail heresy. This is why universalism has been seen as heretical by mainstream Christianity for millennia, for good reason.

End quote. The article goes on to criticize both options at length. Here I want to focus just on the first one. It is related not only to Hart’s universalism, but also to his pantheism, which, as I noted in a review of his more recent book You Are Gods, Hart has now made explicit. I there observed that:

Hart takes creation to follow of necessity from the divine nature. For in God, he says, the distinction between freedom and necessity collapses, and “creation inevitably follows from who [God] is.” This is consistent with the thesis that “creation might not have been,” he says, as long as what this means is simply that creation derives from God, albeit of necessity. Yet it is hard to see how this is different from the Trinitarian claim that the Son is of necessity begotten by the Father; and if it isn’t different, then creation is no less divine than the Son is.

End quote. Fr. Rooney cites the same passage from You Are Gods, which includes other remarks such as:

For God, deliberative liberty – any “could have been otherwise,” any arbitrary decision among opposed possibilities – would be an impossible defect of his freedom. God does not require the indeterminacy of the possible in order to be free… And in the calculus of the infinite, any tension between freedom and necessity simply disappears; there is no problem to be resolved because, in regard to the transcendent and infinite fullness of all Being, the distinction is meaningless.

End quote. Note that Hart takes what amounts to a compatibilist view of divine freedom. That is to say, he claims that God’s being free is compatible with his being unable not to create the world. Now, as Rooney says, this contradicts Christian orthodoxy. To be sure, the tradition affirms that God is unable positively to will evil, specifically, and that the ability to do so would indeed be a defect in his freedom. But it also insists that he was nevertheless able not to create this particular world, or indeed any world at all. For Christian orthodoxy, the claim is not (contra Hart) merely that the world could have failed to exist. It is that God could have refrained from bringing it into being. It is a claim not merely about the nature of the creation, but also about the nature of the creator.

Though Hart couldn’t care less about Catholic doctrine on this subject, it is worth noting that the Church has formally defined this teaching. The First Vatican Council declares: “If anyone… holds that God did not create by his will free from all necessity, but as necessarily as he necessarily loves himself… let him be anathema.” Fr. Rooney calls attention to this and other relevant magisterial statements.

But as Rooney also notes, this is by no means just a matter of current Catholic teaching. It is the teaching of the tradition, going back to scripture and the Fathers of the Church. Now, there are numerous passages from scripture and the Fathers that affirm God’s freedom. Many of these, however, would no doubt be interpreted by Hart in a compatibilist way. But there are also passages that rule out such an interpretation.

For example, many divine actions are described in scripture in a manner that implies that God would not have taken them had certain contingent conditions been different, such as his punishment of sinners at the time of Noah and at Sodom and Gomorrah. Of course, that does not entail that God really went through some reasoning process, as we do, before acting. The point is that the clear implication of these texts is that people could have acted other than the way they did, and that had they done so, Godwould have done something other than what he actually did.

II Maccabees 8:18 says that “almighty God… can by a mere nod destroy not only those who attack us but even the whole world.” That implies that it is possible for God to refrain from conserving the world in being, and for traditional Christian doctrine his conservation of the world is the fundamental way in which he is its creator. Matthew 19:26 says that “with God all things are possible,” which would not be true if God were by nature necessitated to create only the things he actually creates.

The Fathers also understand divine freedom in a way that rules out God’s being necessitated to do what he does. As David Bradshaw notes, Clement of Alexandria says that “God does not do good by necessity, but by choice.” (Does this conflict with the Christian doctrine that God cannot positively will evil? No, because we can understand Clement as meaning, not that God could do evil instead of good, but rather that he could refrain from acting at all rather than doing some good action.) Bradshaw also notes that Basil the Great rejects the idea that God creates “without choice, as the body is the cause of shadow and light the cause of brightness” (where he obviously takes these effects of the body and of light to be necessitated by them); and that Gregory of Nyssa holds that God created “not by any necessity… but because it was fitting.”

Then there is this passage from Athanasius’s Four Discourses against the Arians, III.61, which contrasts God the Son with the things He creates:

Therefore if He be other than all things, as has been above shown, and through Him the works rather came to be, let not ‘by will’ be applied to Him, or He has similarly come to be as the things consist which through Him come to be. For Paul, whereas he was not before, became afterwards an Apostle ‘by the will of God;’ and our own calling, as itself once not being, but now taking place afterwards, is preceded by will, and, as Paul himself says again, has been made ‘according to the good pleasure of His will’ (Ephesians 1:5). And what Moses relates, ‘Let there be light,’ and ‘Let the earth appear,’ and ‘Let Us make man,’ is, I think, according to what has gone before, significant of the will of the Agent. For things which once were not but happened afterwards from external causes, these the Framer counsels to make; but His own Word begotten from Him by nature, concerning Him He did not counsel beforehand.

End quote. Athanasius here distinguishes what comes from God “by nature” from what comes from Him “by will.” The Son proceeds from the Father by nature, whereas created things are made according to the divine will. Since what proceeds from Him by nature is what proceeds of necessity, the implication is that what comes from God by will does not come from Him of necessity. Athanasius also says that what comes about by God’s will involves “counsel” (or “deliberation,” as it has also been translated) and to say that something comes about this way implies that there could have been some alternative outcome.

Similarly, in The City of God, Book XI, Chapter 24, Augustine says that “God made what was made not from any necessity, nor for the sake of supplying any want, but solely from His own goodness, i.e., because it was good.” And Theodoret writes:

The Lord created all things whatsoever He pleased, as Holy Scripture testifies. He did not, however, will all that it lay in His power to do, but only what seemed to Him to be sufficient. For it would have been easy for Him to create ten or twenty thousand worlds. (De curand. graec. affect. 4, quoted in Pohle and Preuss, God: The Author of Nature and the Supernatural, at p. 44)

This implies that there are things that God coulddo but does not in fact do, which entails that the products of divine power do not follow with necessity.

Bradshaw argues that even Dionysius the Areopagite can, contrary to what is often thought, be interpreted as holding that God could have refrained from creating (though the exegetical issues are complicated and I leave it to the interested reader to look at Bradshaw’s paper for himself). Bradshaw thus judges there to be an “apparent unanimity of [patristic] tradition regarding divine choice.”

What became Catholic dogma is, then, well-grounded in Christian tradition, so that Fr. Rooney is, even by Hart’s lights, on solid ground in judging the view that creation follows of necessity from the divine nature to be heretical. Yet in his brief comment on Fr. Rooney’s essay at Twitter, Hart remarks that “simply screaming ‘heretic’ isn't an argument.”

But Rooney does not “scream,” and he does not merely make an accusation of heresy and leave it at that. Rather, calmly and at length, he explains why Hart’s position is heretical in the sense of being incompatible with other non-negotiable claims of the Christian faith. And this is indeed an argument if one’s interlocutor is himself a fellow adherent of that faith.

The reason there is such a category as “heresy” in Christianity, whereas there is no such category in purely philosophical systems, is that Christianity claims to be grounded in special divine revelation. Anything that purports to be a Christian position must be consistent with that revelation, and the notion of heresy is the notion of that which is not consistent with it. Now, a Christian theologian who is accused of heresy might, of course, reasonably question whether the charge is just. He can try to show that his position is, when correctly understood, compatible with Christian revelation. But what he cannot reasonably do is dismiss considerations of orthodoxy and heresy tout court. Again, by virtue of calling himself a Christian, he is committed to staying within the bounds of the revelation, and thus avoiding heresy. And thus he is committed to acknowledging that to accuse a fellow Christian of heresy is indeed an argument. It may or may not at the end of the day be a good argument, but it is an argument.

As I have complained in a recent exchange with Hart, one of the problems with his recent work is that he is not consistent on this point. When it suits his interests, he will appeal to orthodox Christian tradition, and claim that his own views are more consistent with it than those of his opponents. But in other cases, he will dismiss the standard criteria of Christian orthodoxy and appeal instead to merits that his views purportedly exhibit independently of questions of orthodoxy. As I there argued, Hart’s approach isn’t, at the end of the day, that of a Christian theologian. Rather, it is that of a theologian who happens to have been influenced by Christian tradition, but whose ultimate criteria are to be found elsewhere. The considerations raised by Fr. Rooney, and Hart’s failure to take them seriously, reinforce that conclusion.

Related reading:

Scripture and the Fathers contra universalism

Popes, creeds, councils, and catechisms contra universalism

David Bentley Hart’s post-Christian pantheism

Whose pantheism? Which dualism? A Reply to David Bentley Hart

October 14, 2022

The latest on All One in Christ

Here are the latest reviews of my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

. Casey Chalk kindly reviews the book at The Spectator World. From the review:

Here are the latest reviews of my book

All One in Christ: A Catholic Critique of Racism and Critical Race Theory

. Casey Chalk kindly reviews the book at The Spectator World. From the review: Feser’s short book contains several excellent chapters that define, dissect, and ultimately demolish CRT. Not for nothing does writer Ryan T. Anderson call it “the best book I’ve read on the topic.”…

I presume none of Feser’s CRT sparring partners will actually read this book – they have proved themselves so impervious to even the most charitable and tempered criticism that they seem a lost cause…

Perhaps, then, the best target audience for Feser’s pocket-size refutation of CRT are those who thought embracing it would place them in the “good guys” camp, but have begun to realize they were suckered them into a spiral of endless self-abasement. There is no forgiveness or reconciliation in the anti-racist paradigm. That would mean equity had been realized – an end-state anti-racists will never allow, because it would eliminate their (very lucrative) raison d’être.

End quote. The Interim describes the book as “a brief but timely critique of Critical Race Theory that has taken hold of academia and is at the heart of the woke worldview.” At The University Bookman, William Rooney says that “Feser shows that the Church has stood against racism from her inception to date,” and:

That understanding of the human person informed the Church’s condemnation of chattel slavery that arose with the discovery of the New World. Feser cites an array of papal writings… that rejected slavery.

Moreover, writes Rooney, “Feser identifies a number of logical fallacies in the work of CRT authors” and:

In Feser’s analysis, Marxism, postmodernism, liberation theology, and CRT pivot on conflict, power, and domination among classes or racial groups. The individual is marginalized, reconciliation is not possible, and division is necessary for victory. The Catholic paradigm, in contrast, sees each human person as created in the image and likeness of God, as equally, individually, and uniquely sacred, and as called to love God and others with full mind and body through spiritual and corporal works of mercy.

End quote. Recently I was interviewed about the book by Fr. Rob Jack on the radio program Driving Home the Faith. Earlier interviews about the book can be found here.

October 6, 2022

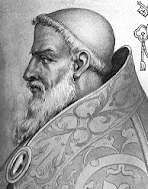

Can Pope Honorius be defended?

My recent article on the error and condemnation of Pope Honorius has gotten a lot of feedback both here and at Twitter (much of the latter surprisingly civil and constructive for that venue). Because of the historical and theological complexities of the topic, several issues have arisen, but the main one I want to address here is the question of whether Honorius can plausibly be defended from the charge of heresy that the Sixth Ecumenical Council leveled against him. Keep in mind that what is at issue here is not whether Honorius taught heresy while issuing a purported ex cathedra definition. He was certainly not doing that, which is why the case of Honorius is irrelevant to whether popes are infallible when they do teach ex cathedra (which is all that the First Vatican Council taught in its decree on papal infallibility). What is at issue is whether Honorius taught heresy when not speaking ex cathedra– and, more generally, whether any pope could in principle do so.

My recent article on the error and condemnation of Pope Honorius has gotten a lot of feedback both here and at Twitter (much of the latter surprisingly civil and constructive for that venue). Because of the historical and theological complexities of the topic, several issues have arisen, but the main one I want to address here is the question of whether Honorius can plausibly be defended from the charge of heresy that the Sixth Ecumenical Council leveled against him. Keep in mind that what is at issue here is not whether Honorius taught heresy while issuing a purported ex cathedra definition. He was certainly not doing that, which is why the case of Honorius is irrelevant to whether popes are infallible when they do teach ex cathedra (which is all that the First Vatican Council taught in its decree on papal infallibility). What is at issue is whether Honorius taught heresy when not speaking ex cathedra– and, more generally, whether any pope could in principle do so. Let’s note also at the outset that the issue here is notwhether Catholics are ordinarily obligated to assent to papal teaching even when it is not put forward infallibly. The answer is that they are ordinarily obligated. More precisely, they owe even non-definitive papal teaching what is called “religious assent,” which is not the unqualified assent owed to teaching put forward infallibly, but is nevertheless firm. To be even more precise, there is a very strong presumptionin favor of such assent, though the Church, in documents like Donum Veritatis, has acknowledged that there can be rare cases in which this presumption is overridden and a faithful Catholic at liberty respectfully to raise questions about some magisterial statement. The clearest sort of case would be one where a magisterial statement appears to conflict with past definitive teaching. I’ve discussed this issue in detail elsewhere.

Now, one point that some readers have made is that the word “heresy” was used in a more expansive way earlier in Church history than it is today. That is correct and important, and it is something I have elsewhere emphasized myself. In modern canon law, heresy is “the obstinate denial or obstinate doubt after the reception of baptism of some truth which is to be believed by divine and Catholic faith.” Pope Honorius was definitely not a heretic in that sense, both because there is no evidence of obstinacy on his part, and because a charitable reading of his problematic statements supports the judgment that he did not intend to undermine traditional teaching (even if his words inadvertently had that effect). There are also the related points that one could be a heretic in the material sense of affirming something doctrinally erroneous, while not being a formal heretic in the sense of persisting in the error even after being warned by ecclesiastical authority; and that whether some doctrine has actually been defined by the Church is relevant to whether it is “to be believed by divine and Catholic faith.”

For these reasons, I prefer to use the more general and less potentially misleading term “error” when discussing the case of Honorius, as I did in the title of my previous post. All the same, the Sixth Ecumenical Council does apply the term “heretic” to Honorius, and “heresy” in those days implied at the very least positive doctrinal error (as opposed, say, to mere negligence or a failure to counter doctrinal error). In other words, by labeling Honorius a heretic, the council was accusing him of teaching false doctrine. The question on the table is whether he can be defended against this charge.

The conciliar condemnations

Needless to say, what Honorius actually said in his letters to Sergius is relevant to this question. But it is not the only thing that is relevant. The chief obstacle to acquitting Honorius of the charge of positively teaching doctrinal error (however inadvertently) is that, as I showed in my previous article, two papally-approved councils of the Church explicitly said that he did. In particular, the Sixth Ecumenical Council explicitly labeled him a “heretic.” And the Seventh Ecumenical Council explicitly condemns “the doctrine of one will held by Sergius, Honorius, Cyrus, and Pyrrhus.”

Defenders of Honorius often argue that Pope St. Leo II, in his statements confirming the council, merely accuses Honorius of negligence in failing to uphold orthodoxy, and of thereby polluting the purity of the Roman See. They think this shows that the council’s own description of Honorius as a heretic has no force. But there are three problems with this argument.

First, what matters is that Leo confirmed the council, thereby making its decrees authoritative. He didn’t say “I confirm it, except for this part.” It’s true that in his own accompanying condemnation, he limits his accusation against Honorius to negligence in suppressing heresy and thereby polluting the purity of the Roman See, and does not apply the label “heretic” to him. But Leo doesn’t deny the truth of the council’s statement that Honorius was a heretic. He just doesn’t mention it (just as he doesn’t mention other things the council said).

Second, as noted by John Chapman (whose book on Honorius I discussed in my previous post), the Church has long held that “an error which is not resisted is approved; a truth which is not defended is suppressed” (in the words of Honorius’s predecessor Pope Felix III). It is possible to be guilty of teaching doctrinal error by implication, when the context demands that a certain truth needs to be explicitly affirmed and instead one not only fails to do so but speaks in an ambiguous way that gives the appearance of approving the error. And that is exactly what Honorius did. The Monothelite error was being put forward, and he not only did not clearly condemn it but seemed to be saying that it could be accepted. The suggestion that his words can be given a more charitable reading (as I agree they can) is relevant to his personal culpability, but it is not relevant to the question of the doctrinal soundness of the words themselves, and as Chapman emphasizes, in a context like this it is the words that matter.

Third, whatever one says about Leo and the Sixth Ecumenical Council, the papally-approved Seventh Ecumenical Council, which occurred a century later (and thus long after Leo was gone), explicitly characterized Honorius as having taught doctrinal error. Hence even if it were conceded that Leo rejected the Sixth Council’s description of Honorius as a heretic, the point would be moot. The Seventh Council would remain as an obstacle to the defense of Honorius.

At this point, defenders of Honorius might argue (as they sometimes do) that while papally-approved councils cannot err on matters of doctrine, they can err on matters of history. And whether Honorius really was guilty of heresy is, the argument continues, a historical question rather than a doctrinal one. But there are two problems with this argument.

First, the reason a council condemns someone as a heretic is because of his teaching. Hence it is, first and foremost, Honorius’s teaching that was condemned. That means that the teaching was judged heretical. But whether a teaching is heretical is a doctrinal matter, and not a mere historical matter. Now, given that a papally-approved council cannot err on doctrinal matters, it follows that the councils in question infallibly judged that Honorius’s teaching was heretical (whatever his intentions). But since anyone who teaches heresy is a heretic, it follows (at least given that Honorius really did write the letters that got him into trouble, as most of his defenders concede) that these councils did after all infallibly judge that Honorius was a heretic.

Second, the reason most of Honorius’s defenders try to defend him is to avoid having to acknowledge that a pope can teach heresy when not speaking ex cathedra. Now, suppose that the councils did indeed get it wrong when judging that Honorius, specifically, was a heretic. Since that is a historical rather than doctrinal matter, such an error is possible. Still, by making this judgment, the councils also taught by implication that it is possible for a pope to teach heresy (when not speaking ex cathedra). And that is a doctrinal matter. That is enough to refute the larger claim that Honorius’s defenders are trying to uphold by defending him.

This is why Chapman drew the bold conclusion that “unquestionably no Catholic has the right to deny that Honorius was a heretic… a heretic in words if not in intention” (p. 116). Quibbles over how to interpret his letters are largely a red herring. What matters more is the authority of papally-approved councils of the Church.

The opinions of the theologians

In response to my previous article, S. D. Wright calls attention to an article of his own from last year at the website The WM Review, defending Pope Honorius. Wright makes much of what various theological authorities have said about the controversy, and suggests that if we are just going by the numbers, those who would defend Honorius outnumber those who would not.

Even if this is true, it is hardly a decisive argument, given that (as Aquinas famously pointed out) the argument from authority, while not without value, is still the weakest of arguments when the authorities in question are merely human rather than divine. And they are merely human, given that this is at best a matter about which the Church has not decided, and leaves open to the free debate of theologians. Indeed, as I have argued, it is actually worse than that for Honorius’s defenders, given that two papally-approved councils (which teach infallibly and thus do have divine authority behind them) taught that Honorius was guilty of teaching error.

Wright is also selective in the way he cites the relevant authorities. For example, while he acknowledges that Chapman is on the side of those who judge Honorius to be guilty of teaching error, he makes Chapman’s position sound more tentative than it really is. Wright claims, for example: “Chapman is the most hostile critic, and yet all that he can bring himself to say is that certain passages are ‘difficult to account for.’” As we’ve just seen, though, that is far from the truth. Again, in his book Chapman goes so far as to say that “unquestionably no Catholic has the right to deny that Honorius was a heretic”; and in his Catholic Encyclopedia article on Honorius, he says that “it is clear that no Catholic has the right to defend Pope Honorius. He was a heretic, not in intention, but in fact.” Oddly, Wright does not quote these (rather important) remarks when reporting on Chapman’s views.

Wright also gives the impression that the Doctors of the Church who have addressed the matter all line up on the side of defending Honorius from the charge of heresy. That is not the case. Wright neglects to mention the opinion of St. Francis de Sales, who, when addressing papal authority in The Catholic Controversy, says that “we do not say that the Pope cannot err in his private opinions, as did John XXII, or be altogether a heretic, as perhaps Honorius was” (p. 225).

Wright appeals to the opinion of St. Alphonsus Liguori, who addressed the case of Honorius in The History of Heresies, and Their Refutation. That is not unreasonable, given St. Alphonsus’s stature, just as it is not unreasonable to consider the similar opinion of St. Robert Bellarmine (which I discussed in my previous article). But it is important to note that St. Alphonsus and St. Robert do not entirely agree on this matter. Bellarmine takes seriously the theory that the documents of the Sixth Ecumenical Council have been corrupted, whereas St. Alphonsus rejects this idea, noting that “this conjecture is not borne out by the learned men of our age… [who] clearly prove the authenticity of the Acts” (p. 186). St. Alphonsus also rejects Bellarmine’s suggestion that the Fathers of the council were mistaken in their judgment about Honorius, and endorses the view of another author that:

[I]t is very hard to believe that all the Fathers, not alone of this Council, but also of the Seventh and Eighth General Councils, who also condemned Honorius, were in error, in condemning his doctrine. (p. 186)

St. Alphonsus is harder on Honorius than Bellarmine is, writing:

We do not, by any means, deny that Honorius was in error, when he imposed silence on those who discussed the question of one or two wills in Christ, because when the matter in dispute is erroneous, it is only favoring error to impose silence…

[H]e was very properly condemned, for the favourers of heresy and the authors of it are both equally culpable. (pp. 181 and 182)

St. Alphonsus concludes that the only plausible defense of Honorius is to argue that he was not himself a Monothelite heretic, while nevertheless conceding that he was justly condemned “as a favourer of heretics, and for his negligence in repressing error” and for “using ambiguous words to please and keep on terms with heretics” (p. 187). That is very close to Chapman’s view that Honorius can justly be accused of heresy given Felix III’s dictum that “an error which is not resisted is approved; a truth which is not defended is suppressed” – even if St. Alphonsus himself stops short of that conclusion.

(As a side note, and while we’re on the subject of arguments from authority, let me cite one further authority mentioned by Chapman, St. Maximus the Confessor. Now, Maximus, to be sure, defended Honorius. However, as Chapman reports, when Monothelite heretics asked Maximus what he would do if Rome were to affirm their position, his answer was: “The Holy Ghost anathematizes even angels, should they command aught beside the faith” (pp. 62-63). Maximus does not answer that Rome could not possibly do that, or that if Rome did so, then Monothelitism would have to be accepted. That implies that St. Maximus allowed that it is possible for the pope to err, at least when not speaking in a definitive way.)

Now, the opinion of the Doctors of the Church is indeed very weighty when they are all in agreement. But here, as we have seen, they are not in agreement. Hence Wright’s argument is not strong. Meanwhile, the argument from the authority of papally-approved councils is very strong. I conclude that a case in defense of Honorius remains, at best, difficult to make.

October 4, 2022

The error and condemnation of Pope Honorius

A pope is said to speak ex cathedra or “from the chair” when he solemnly puts forward some teaching in a manner intended to be definitive and absolutely binding. This is also known as an exercise of the pope’s extraordinary magisterium, and its point is to settle once and for all disputed matters concerning faith or morals. The First Vatican Council taught that such ex cathedra doctrinal definitions are infallible and thus irreformable. The ordinary magisterium of the Church too (whether in the person of the pope or some other bishop or body of bishops) can sometimes teach infallibly, when it simply reiterates some doctrine that has always and everywhere been taught.

A pope is said to speak ex cathedra or “from the chair” when he solemnly puts forward some teaching in a manner intended to be definitive and absolutely binding. This is also known as an exercise of the pope’s extraordinary magisterium, and its point is to settle once and for all disputed matters concerning faith or morals. The First Vatican Council taught that such ex cathedra doctrinal definitions are infallible and thus irreformable. The ordinary magisterium of the Church too (whether in the person of the pope or some other bishop or body of bishops) can sometimes teach infallibly, when it simply reiterates some doctrine that has always and everywhere been taught. The Church does not hold, however, that popes alwaysteach infallibly when not speaking ex cathedra. The First Vatican Council deliberately stopped short of making that claim. One reason for this is that there have been a few popes (though only a few) who erred when not exercising their extraordinary magisterium. The most spectacular case is that of Pope Honorius I (pope from 625-638 A.D.), who taught a Christological error that facilitated the spread of the Monothelite heresy, and was formally condemned for it by several Church councils and later popes.

The case is briefly discussed in many Church histories and reference works, but an especially detailed account is to be found in Fr. John Chapman’s short book The Condemnation of Pope Honorius, which was published in 1907 by the Catholic Truth Society. You can read it online via the Internet Archive. Chapman is also the author of the article about Pope Honorius in the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia, which presents a shorter but still substantive account. His results are briefly but approvingly discussed by Fr. Cuthbert Butler in his 1930 book The Vatican Council 1869-1870, the main scholarly work in English about the council and the debate between the council Fathers over papal infallibility.

Many contemporary readers with only a superficial knowledge of the history and theology of the papacy are bound to find shocking the details of the case of Honorius as recounted by writers like Chapman and Butler. They might expect to hear such things only from either theological liberals keen to subvert the authority of the papacy, or radical traditionalists looking for precedents for accusing recent popes of heresy. But Chapman and Butler were perfectly mainstream orthodox Catholic academics of the day, whose work was in no way considered scandalous. They were writing long before the debates over liberalism and traditionalism that arose after Vatican II, so that they cannot be accused of having any ax to grind in those debates.

Indeed, Chapman was writing during the pontificate of Pope St. Pius X, the great foe of modernism and upholder of the authority of the papacy. In fact, part of the point of Chapman’s book itself was precisely to uphold that authority, and in particular to defend the Council’s teaching on papal infallibility. And yet for all that, Chapman does not shrink from the judgment that the historical facts show that “no Catholic has the right to deny that Honorius was a heretic” (p. 116). The reason he could say this is that the error Honorius was guilty of did not occur in the context of an ex cathedra definition. And thus Chapman’s judgement is perfectly within the bounds of what everyone acknowledged to be the orthodox understanding of the papacy even in Pius X’s day.

Honorius’s error

The Monothelite heresy arose as a sequel to the Monophysite heresy. Orthodox Christology holds that Christ is one Person with two natures, divine and human. Monophysitism holds that Christ has only one nature, the divine one. Monothelitism can be understood as an attempt to find a middle ground position between Monophysitism and orthodoxy. It holds that while there are two natures in Christ, there is only one will. From the point of view of orthodoxy, this is unacceptable, for one’s will is an integral part of one’s nature. Hence to deny the reality of two wills in Christ is implicitly to deny that he has two natures. (I’m aware that the dispute over these heresies is more complicated than this quick summary lets on. But the nuances are irrelevant to the particular purposes of this article.)

The trouble for Pope Honorius began when Sergius, patriarch of Constantinople, wrote to him on the topic of Christ’s will and proposed a compromise that might appeal to disaffected Monophysites. In his reply, Honorius affirmed that it is better to avoid speaking of either “one or two operations” in Christ, and even affirmed a sense in which there is “one will” in Christ. The problem is that the first claim seems to leave wiggle room for Monothelitism, and the second seems positively to affirm it.

To be sure, as defenders of Honorius have argued and as Chapman allows, Honorius’s intent was not heretical. But Honorius’s statements gave ammunition to the Monothelites, who treated his words as a doctrinal definition and appealed to them in support of their position. And as Chapman notes, whatever Honorius’s intentions, “in a definition it is the words that matter” rather than the intention behind them, and considered as a definition Honorius’s words “are obviously and beyond doubt heretical” (p. 16).

Now, Honorius was not in fact proposing an ex cathedra definitive formulation, which is why his error is not incompatible with the teaching of Vatican I about the conditions on papal infallibility. But it is not true to say (as some have in Honorius’s defense) that he was merely speaking as a private theologian. He was doing no such thing. Sergius wrote to him seeking the authoritative advice of the bishop of Rome, and Honorius responded in that capacity. And the error was extremely grave, for as Chapman notes, the Monothelite heresy really only gained momentum after Honorius’s response to Sergius, and partly as a result of it.

The popes following Honorius began to correct the situation by affirming orthodox teaching, and initially tried either to give Honorius’s words an orthodox sense or simply to ignore them. But as the controversy grew (and involved a complex series of events and cast of characters including St. Sophronius, the Emperor Heraclius, Patriarch Pyrrhus of Constantinople, St. Maximus, and popes John IV, Theodore I, and St. Martin I, among others) it became harder to defend Honorius, whose words had done so much to instigate it. Pope St. Martin and St. Maximus were among those who suffered severe persecution from the Monothelites, underlining the gravity of the consequences of Honorius’s error.

Honorius’s condemnation

The Third Council of Constantinople (680-681 A.D., also known as the Sixth Ecumenical Council recognized as authoritative by the Catholic Church) was called to deal with the crisis. It condemned the exchange between Sergius and Honorius very harshly, stating:

The holy council said: After we had reconsidered… the doctrinal letters of Sergius… to Honorius some time Pope of Old Rome, as well as the letter of the latter to the same Sergius, we find that these documents are quite foreign to the apostolic dogmas, to the declarations of the holy Councils, and to all the accepted Fathers, and that they follow the false teachings of the heretics; therefore we entirely reject them, and execrate them as hurtful to the soul.

But Honorius himself, and not merely his words, was also condemned, in terms no less harsh:

We define that there shall be expelled from the holy Church of God and anathematized Honorius who was some time Pope of Old Rome, because of what we found written by him to Sergius, that in all respects he followed his view and confirmed his impious doctrines.

The late pope is included by the council in a long list of anathematized heretics:

To Theodore of Pharan, the heretic, anathema!

To Sergius, the heretic, anathema!

To Cyrus, the heretic, anathema!

To Honorius, the heretic, anathema!

To Pyrrhus, the heretic, anathema!

Etc.

And again:

We cast out of the Church and rightly subject to anathema all superfluous novelties as well as their inventors: to wit, Theodore of Pharan, Sergius and Paul, Pyrrhus, and Peter (who were archbishops of Constantinople), moreover Cyrus, who bore the priesthood of Alexandria, and with them Honorius, who was the ruler of Rome, as he followed them in these things.

By no means did this reflect any animus against Rome, nor a rejection of papal authority. On the contrary, as Chapman emphasizes, the decrees of the council were signed by the representatives of the then current pope, Pope St. Agatho. The council also warmly praises “our most blessed and exalted pope, Agatho,” and affirms that St. Peter “spoke through” him. Agatho’s successor, Pope St. Leo II, confirmed the council, and added his own personal condemnation of his predecessor, stating:

We anathematize the inventors of the new error, that is, Theodore, Sergius… and also Honorius, who did not attempt to sanctify this Apostolic Church with the teaching of Apostolic tradition, but by profane treachery permitted its purity to be polluted.

Even that was not the end of it. The Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787 A.D. (also known as the Second Council of Nicaea) reiterated the previous council’s condemnation:

We affirm that in Christ there be two wills and two operations according to the reality of each nature, as also the Sixth Synod, held at Constantinople, taught, casting out Sergius, Honorius, Cyrus, Pyrrhus, Macarius, and those who agree with them.

And again:

We have also anathematized… the doctrine of one will held by Sergius, Honorius, Cyrus, and Pyrrhus, or rather, we have anathematised their own evil will.

The Eighth Ecumenical Council of 869-870 A.D. (also known as the Fourth Council of Constantinople) reiterated the condemnation yet again:

We anathematize Theodore who was bishop of Pharan, Sergius, Pyrrhus, Paul and Peter, the unholy prelates of the church of Constantinople, and with these, Honorius of Rome.

As Chapman notes, in addition to these repeated anathemas:

It is still more important that the formula for the oath taken by every new Pope from the 8th century till the 11th adds these words to the list of Monothelites condemned: “Together with Honorius, who added fuel to their wicked assertions.” (pp. 115-16)

On top of that, Chapman adds: “Honorius was mentioned as a heretic in the lessons of the Roman Breviary for June 28th, the feast of St. Leo II, until the 18thcentury” (p. 116).

Over forty years passed between Honorius’s death and his condemnation by the first of the councils referred to. But once he was condemned, the condemnation was repeatedly reaffirmed at the highest levels of the Church for centuries.

Can Honorius be defended?

This is why Chapman draws the conclusion: “Unquestionably no Catholic has the right to deny that Honorius was a heretic… a heretic in words if not in intention” (p. 116), and why Butler cites this conclusion sympathetically. Some have tried to show how Honorius’s words can be read in an orthodox way, but as Chapman and Butler emphasize, this misses the point that the question of whether Honorius was a heretic cannot be settled by reference to his letters alone. The fact that councils and laterpopes themselves have denounced him as a heretic is also crucial, for to deny that he was a heretic is thereby to challenge the judgment of these councils and popes. To show that Honorius did not err, but at the cost of showing that these later popes and (papally approved) councils did err, would be a Pyrrhic victory.

Some have emphasized that Pope St. Leo II, in his own statement, seems to accuse Honorius only of aiding and abetting heresy rather than condemning him for being a heretic himself, as the Third Council of Constantinople had. They seem to think this absolves Honorius of the charge of heresy. But there are several problems with this move. First, as Chapman notes, in one respect Leo’s statement is harsher than the council’s, not less harsh. For Leo goes so far as to accuse his predecessor of polluting the purity of the Roman See itself, which the council had not done. Second, Leo did confirm the council, and thereby lent authority to its decrees. And those decrees explicitly condemn Honorius as a heretic. Third, the later councils, as well as the later papal oath, reaffirmed Honorius’s anathematization.

To be sure, there have over the centuries nevertheless been those who have tried to defend Honorius, the most eminent being St. Robert Bellarmine (in Book 4, Chapter XI of On the Sovereign Pontiff). But his arguments are weak, and were rejected by later orthodox Catholic theologians. For example, Bellarmine proposes that “perhaps” Honorius’s letter to Sergius was faked by the heretics, though he also argues that if this theory is rejected, the letter can be given an orthodox reading. But these strategies obviously conflict with one another. If the problematic parts of the letter were faked by heretics precisely for the purpose of spreading their heresy, then how can they plausibly be given an orthodox reading? Or if these parts of the letter are in fact orthodox, how can it plausibly be maintained that they were faked? Wouldn’t heretics forging a letter have put into it statements that clearly supported their position?

Then there is the fact that the Third Council of Constantinople condemned Honorius. Here too Bellarmine suggests that one strategy to defend Honorius would be to propose that the relevant passages from the council proceedings were faked, and inserted by enemies of Rome. But the council proceedings elsewhere praise Rome and other popes, so what sense would this have made? Alternatively, Bellarmine suggests, perhaps the council really did condemn Honorius, but did so under the mistaken assumption that he was a heretic. This is not a problem, Bellarmine says, because a council can be mistaken about a historical (as opposed to doctrinal) matter. But even if the council had been mistaken about Honorius, in condemning him it was teaching that popes can (when not speaking ex cathedra) be guilty of heresy, and that is a doctrinal matter. The larger lesson of the case of Honorius (namely that popes can err when not teaching ex cathedra) would remain, whatever one thinks of Honorius himself.

Bellarmine even suggests that maybe Leo’s letter, too, was faked! The positing of so much fakery illustrates just how desperate the arguments of even as fine a mind as Bellarmine’s have to be in order to try to get Honorius off the hook. And that is why such arguments were largely abandoned. As another Catholic historian of the era of Chapman and Butler, Fr. H. K. Mann, stated in his book The Lives of the Popes in the Early Middle Ages, Second edition, Volume I, Part I:

Contrary to the opinion of some Catholic writers, [Honorius’s] letters are here allowed to be genuine and incorrupt; as are also the Acts of the Sixth General Council. This is in accordance with nearly all the best Catholic modern authors. (p. 337)